| Revision as of 00:47, 25 September 2007 edit71.227.163.98 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 04:45, 25 September 2007 edit undoSilver Edge (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users24,819 edits Undid revision 160146926 by 71.227.163.98 (talk), all the other discontinued console articles uses "was".Next edit → | ||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

| {{redirect|Famicom|"Famikon" in the generic sense as used in the Japanese language|Video game console}} | {{redirect|Famicom|"Famikon" in the generic sense as used in the Japanese language|Video game console}} | ||

| The '''Nintendo Entertainment System''' (often referred to as the '''NES''' or simply '''Nintendo'''), |

The '''Nintendo Entertainment System''' (often referred to as the '''NES''' or simply '''Nintendo'''), was an ] ] released by ] in ], ], ], and ] in 1985. In most of ], including ] (where it was first launched in 1983), the ], ], ], and ], it was released as the {{nihongo|'''Family Computer'''|ファミリーコンピュータ|Famirī Konpyūta}} or simply, the {{nihongo|'''Famicom'''|ファミコン|Famikon}} ''{{Audio|Famicom.ogg|listen}}''. In ], the hardware was licensed to ], which marketed it as the '''Comboy''' (컴보이).<ref name="korea">{{cite web | title=Breaking the Ice: South Korea Lifts Ban on Japanese Culture | url=http://web-japan.org/trends98/honbun/ntj981207.html | format=html | accessdate=May 19 | accessyear=2007 | date=December 7 | year=1998 | work=}}</ref> | ||

| The most successful gaming console of its time in Asia and North America{{Fact|date=September 2007}} (Nintendo claims to have sold over 60 million NES units worldwide<ref name="classicsystems">{{cite web | title=Classic Systems—Nintendo Entertainment System | work=Nintendo | url=http://www.nintendo.com/systemsclassic?type=nes | format=html | accessdate=February 11 | accessyear=2006}}</ref>), it helped revitalize the US video game industry following the ]. It set the standard for subsequent consoles in everything from ] (the breakthrough ], '']'', was the system’s first major success) to controller layout. The NES was the first console for which the manufacturer openly courted ]s. | The most successful gaming console of its time in Asia and North America{{Fact|date=September 2007}} (Nintendo claims to have sold over 60 million NES units worldwide<ref name="classicsystems">{{cite web | title=Classic Systems—Nintendo Entertainment System | work=Nintendo | url=http://www.nintendo.com/systemsclassic?type=nes | format=html | accessdate=February 11 | accessyear=2006}}</ref>), it helped revitalize the US video game industry following the ]. It set the standard for subsequent consoles in everything from ] (the breakthrough ], '']'', was the system’s first major success) to controller layout. The NES was the first console for which the manufacturer openly courted ]s. | ||

Revision as of 04:45, 25 September 2007

| Official Nintendo Entertainment System logoFamicom Family logo | |

| |

| Manufacturer | Nintendo |

|---|---|

| Type | Video game console |

| Generation | Third generation (8-bit era) |

| Lifespan | July 15, 1983 October 18, 1985 February 1986 1 September 1986 1987 |

| Units sold | 60 million |

| Media | Cartridge (“Game Pak”) |

| CPU | Ricoh 2A03 8-bit processor (MOS Technology 6502 core) |

| Controller input | 2 controller ports 1 expansion slot |

| Best-selling game | Super Mario Bros. (pack-in / separately) Super Mario Bros. 3 |

| Predecessor | Color TV Game |

| Successor | Super Nintendo Entertainment System |

"NES" redirects here. For other uses, see NES (disambiguation). "Famicom" redirects here. For "Famikon" in the generic sense as used in the Japanese language, see Video game console.

The Nintendo Entertainment System (often referred to as the NES or simply Nintendo), was an 8-bit video game console released by Nintendo in North America, Brazil, Europe, and Australia in 1985. In most of Asia, including Japan (where it was first launched in 1983), the Philippines, Taiwan, Vietnam, and Singapore, it was released as the Family Computer (ファミリーコンピュータ, Famirī Konpyūta) or simply, the Famicom (ファミコン, Famikon) listen. In South Korea, the hardware was licensed to Hyundai Electronics, which marketed it as the Comboy (컴보이).

The most successful gaming console of its time in Asia and North America (Nintendo claims to have sold over 60 million NES units worldwide), it helped revitalize the US video game industry following the video game crash of 1983. It set the standard for subsequent consoles in everything from game design (the breakthrough platform game, Super Mario Bros., was the system’s first major success) to controller layout. The NES was the first console for which the manufacturer openly courted third-party developers.

The slogan for the NES in North America is "Now You're Playing With Power!"

History

Main article: History of the Nintendo Entertainment SystemFollowing a series of arcade game successes in the early 1980s, Nintendo made plans to produce a cartridge-based console. Masayuki Uemura designed the system, which was released in Japan on July 15, 1983 for ¥14,800 alongside three ports of Nintendo’s successful arcade games Donkey Kong, Donkey Kong Jr., and Popeye. The Nintendo Family Computer (Famicom) was slow to gather momentum; during its first year, many criticized the system as unreliable, prone to programming errors and rampant freezing. Following a product recall and a reissue with a new motherboard, the Famicom’s popularity soared, becoming the best-selling game console in Japan by the end of 1984.

Encouraged by its successes, Nintendo soon turned its attention to the North American market. Nintendo entered into negotiations with Atari to release the Famicom under Atari’s name as the name Nintendo Enhanced Video System; however, this deal eventually fell through. Subsequent plans to market a Famicom console in North America featuring a keyboard, cassette data recorder, wireless joystick controller, and a special BASIC cartridge under the name "Nintendo Advanced Video System" likewise never materialized.

Finally, in June 1985, Nintendo unveiled its American version of the Famicom at the Consumer Electronics Show (CES). Nintendo rolled out its first systems to limited American markets on October 18, 1985, following up with a full-fledged North American release of the console in February of the following year. Nintendo simultaneously released eighteen launch titles: 10-Yard Fight, Baseball, Clu Clu Land, Donkey Kong Jr. Math, Duck Hunt, Excitebike, Golf, Gyromite, Hogan’s Alley, Ice Climber, Kung Fu, Mach Rider, Pinball, Stack-Up, Tennis, Wild Gunman, Wrecking Crew, and, Super Mario Bros..

In Europe and Australia, the system was released to two separate marketing regions (A and B). Distribution in region B, consisting of most of mainland Europe (excluding Italy), was handled by a number of different companies, with Nintendo responsible for most cartridge releases; most of region B saw a 1986 release. Mattel handled distribution for region A, consisting of the United Kingdom, Ireland, Italy, Australia and New Zealand, starting the following year. Not until 1990 did Nintendo’s newly created European branch take over distribution throughout Europe. Despite the system’s lackluster performance outside of Japan and North America, by 1990 the NES had outsold all previously released consoles.

As the 1990s dawned, however, renewed competition from technologically superior systems such as the 16-bit Sega Mega Drive (known as the Sega Genesis in North America) marked the end of the NES’s dominance. Eclipsed by Nintendo’s own Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES), the NES’s user base gradually waned. Nintendo continued to support the system in America through the first half of the decade, even releasing a new version of the console, the NES 2, to address many of the design flaws in the original NES hardware. The final games released for the system were as follows: in Japan, Adventure Island 4 in 1994, and, in America, among unlicensed titles, Sunday Funday was the last, whereas Wario's Woods was the last licensed game (also the only one with an ESRB rating). In the wake of ever decreasing sales and the lack of new software titles, Nintendo of America officially discontinued the NES by 1995. Despite this, Nintendo of Japan kept producing new Nintendo Famicoms for a niche market up until October 2003, when Nintendo of Japan officially discontinued the line. Even as developers ceased production for the NES, a number of high-profile video game franchises and series for the NES were transitioned to newer consoles and remain popular to this day. Nintendo’s own Super Mario Bros., The Legend of Zelda, and Metroid franchises debuted on the NES, as did Capcom’s Mega Man franchise, Konami’s Castlevania franchise, and Square Enix’s Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest franchises.

In the years following the official "death" of the NES in the West, a collector’s market based around video rental shops, garage sales, and flea markets led some gamers to rediscover the NES. Coupled with the growth of console emulation, the late 1990s saw something of a second golden age for the NES. The secondhand market began to dry up after 2000, and finding ROMs (digital copies of games for use on emulators) no longer represented the challenge it had in the past. Parallel to the rise of interest in emulation was the emergence of a dedicated NES hardware "modding" scene. Such hobbyists perform tasks such as moving the NES to a completely new case, or just dissecting it for parts or fun. The controllers are particular targets for modding, often being adapted to connect with personal computers by way of a parallel or USB port. Some NES modders have transformed the console into a portable system by adding AA batteries and an LED or LCD screen.

Bundle packages

For its North American release, the NES was released in two different configurations, or "bundles". The console deck itself was identical, but each bundle was packaged with different Game Paks and accessories. The first of these sets, the Control Deck, retailed from US$199.99, and included the console itself, two game controllers, and a Super Mario Bros. game cartridge. The second bundle, the Deluxe Set, retailed for US$249.99, and consisted of the console, a R.O.B., a NES Zapper (electronic gun), and two game paks: Duck Hunt and Gyromite.

For the remainder of the NES’s commercial lifespan in North America, Nintendo frequently repackaged the console in new configurations to capitalize on newer accessories or popular game titles. Subsequent bundle packages included the NES Action Set, released in November 1988 for US$199.99, which replaced both of the earlier two sets, and included the console, the NES Zapper, two game controllers, and a multicart version of Super Mario Bros. and Duck Hunt. The Action Set became the most successful of the packages released by Nintendo. One month later, in December 1988, to coincide with the release of the Power Pad floor mat controller, Nintendo released a new Power Set bundle, consisting of the console, the Power Pad, the NES Zapper, two controllers, and a multicart containing Super Mario Bros., Duck Hunt, and World Class Track Meet. In 1990, a Sports Set bundle was released, including the console, a NES Satellite infrared wireless multitap adaptor, four game controllers, and a multicart featuring Super Spike V'Ball and Nintendo World Cup.

It is difficult to count the total number of games released on the NES. One can look at the number of games licensed by Nintendo of America or Japan, or combine them, or even add the numerous unlicensed titles. All told, well over 1,000 games are available on the NES platform.

Two more bundle packages were released using the original model NES console. The Challenge Set included the console, two controllers, and a Super Mario Bros. 3 game pak. The Basic Set, first released in 1987, included only the console and two controllers with no pack-in cartridge. Instead, it contained a book called the The Official Nintendo Player's Guide, which contained detailed information for every NES game made up to that point. Finally, the redesigned NES 2 was released as part of the final Nintendo-released bundle package, once again under the name Control Deck, including the new style NES 2 console, and one redesigned "dogbone" game controller. Released in October 1993, this final bundle retailed for $49.99, and remained in production until the discontinuation of the NES in 1995.

Regional differences

Although the Japanese Famicom and the international NES included essentially the same hardware, there were certain key differences between the two systems:

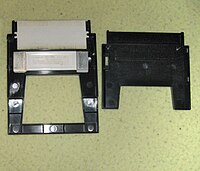

- Different case design. The Famicom featured a top-loading cartridge slot, a 15-pin expansion port located on the unit’s front panel for accessories (as the controllers were hard-wired to the back of the console), and a red and white color scheme. The NES featured a front-loading cartridge slot (often jokingly compared to a toaster), and a more subdued gray, black and red color scheme. An expansion port was found on the bottom of the unit, and the cartridge connector pinout was changed.

- 60-pin vs. 72-pin cartridges. The original Famicom and the re-released AV Family Computer both utilized a 60-pin cartridge design, which resulted in smaller cartridges than the NES (and the NES 2), which utilized a 72-pin design. Four pins were used for the 10NES lockout chip. Ten pins were added that connected a cartridge directly to the expansion port on the bottom of the unit. Finally, two pins that allowed cartridges to provide their own sound expansion chips were removed, a regrettable decision. Many early games (such as Stack-Up) released in North America were simply Famicom cartridges attached to an adapter (such as the T89 Cartridge Converter) to allow them to fit inside the NES hardware. Nintendo did this to reduce costs and inventory by using the same cartridge boards in America and Japan.

- A number of peripheral devices and software packages were released for the Famicom. Few of these devices were ever released outside of Japan.

- Famicom Disk System (FDS). Although not included with the original system, a popular floppy disk drive peripheral was released for the Famicom in Japan only. Nintendo never released the Famicom Disk System outside of Japan, citing concerns about software bootlegging. Notable games released for the FDS include The Legend of Zelda, Yume Kōjō: Doki Doki Panic, Metroid, and the original Super Mario Bros. 2.

- Famicom BASIC was an implementation of BASIC for the Famicom. It allowed the user to program his or her own games. Many programmers got their first experience on programming for the console this way.

- Famicom MODEM was a modem that allowed connection to a Nintendo server which provided content such as jokes, news (mainly about Nintendo), game tips, and weather reports for Japan; it also allowed a small number of programs to be downloaded.

- External sound chips. The Famicom had two cartridge pins that allowed cartridges to provide external sound enhancements. They were originally intended to facilitate the Famicom Disk System’s external sound chip. These pins were removed from the cartridge port of the NES, and relocated to the bottom expansion port. As a result, individual cartridges could not make use of this functionality, and many NES localizations suffered from inferior sound compared to their equivalent Famicom versions. Castlevania III: Dracula’s Curse is a notable example of this problem.

- Hardwired controllers. The Famicom’s original design includes hardwired, non-removable controllers. In addition, the second controller featured an internal microphone for use with certain games and lacked SELECT and START buttons. Both the controllers and the microphone were subsequently dropped from the redesigned AV Famicom in favor of the two seven-pin controller ports on the front panel used in the NES from its inception.

- Lockout circuitry. The Famicom contained no lockout hardware, and, as a result, unlicensed cartridges (both legitimate and bootleg) were extremely common throughout Japan and the Far East. The original NES (but not the top-loading NES 2) contained the 10NES lockout chip, which significantly increased the challenges faced by unlicensed developers. Tinkerers at home in later years discovered that disassembling the NES and cutting the fourth pin of the lockout chip would change the chip’s mode of operation from "lock" to "key", removing all effects and greatly improving the console’s ability to play legal games, as well as bootlegs and converted imports. The European release of the console used a regional lockout system that prevented cartridges released in region A from being played on region B consoles, and vice versa.

- Audio/video output. The original Famicom featured an RF modulator plug for audio/video output, while the original NES featured both an RF modulator and RCA composite output cables. The AV Famicom featured only RCA composite output, and the top-loading NES 2 featured only RF modulator output. The original North American NES was the first game console to feature direct composite video output so people could hook it up to a stand-alone composite monitor.

- Third-party cartridge manufacturing. In Japan, six companies, namely Nintendo, Konami, Capcom, Namco, Bandai, and Jaleco, manufactured the cartridges for the Famicom. This allowed these companies to develop their own customized chips designed for specific purposes, such as Konami's VRC 6 and VRC 7 sound chips that increased the quality of sound in their games.

Game controllers

See also: List of Nintendo Entertainment System accessoriesThe game controller used for both the NES and the Famicom featured a brick-like design with a simple four button layout: two round buttons labelled "B" and "A", a "START" button, and a "SELECT" button. Additionally, the controllers utilized the cross-shaped D-pad, designed by Nintendo employee Gunpei Yokoi for Nintendo Game & Watch systems, to replace the bulkier joysticks on earlier gaming consoles’ controllers.

The original model Famicom featured two game controllers, both of which were hardwired to the back of the console. The second controller lacked the START and SELECT buttons, but featured a small microphone. Relatively few games made use of this feature. The earliest produced Famicom units initially had square A and B buttons. This was changed to the circular designs because of the square buttons being caught in the controller casing when pressed down, and glitches within the hardware causing the system to freeze occasionally while playing a game.

The NES dropped the hardwired controllers, instead featuring two custom 7-pin ports on the front of the console. Also in contrast to the Famicom, the controllers included with the NES were identical to each other—the second controller lacked the microphone that was present on the Famicom model, and possessed the same START and SELECT buttons as the primary controller.

A number of special controllers designed for use with specific games were released for the system, though very few such devices proved particularly popular. Such devices included, but were not limited to, the NES Zapper (a light gun), the Power Pad, and the ill-fated R.O.B. and Power Glove. The original Famicom featured a deepened DA-15 expansion port on the front of the unit, which was used to connect most auxiliary devices. On the NES, these special controllers were generally connected to one of the two control ports on the front of the unit.

Near the end of the NES's lifespan, upon the release of the AV Famicom and the top-loading NES 2, the design of the game controllers was modified slightly. Though the original button layout was retained, the redesigned device abandoned the "brick" shell in favor of a "dog bone" shape reminiscent of the controllers of the Super Nintendo Entertainment System. In addition, the AV Famicom joined its international counterpart and dropped the hardwired controllers in favor of detachable controller ports. However, the controllers included with the Famicom AV, despite being the "dog bone" type, had cables which were a short three feet long, as opposed to the standard six feet of NES controllers.

In recent years the original NES controller has become one of the most recognizable symbols of the system. Nintendo has mimicked the look of the controller in several recent products, from promotional merchandise to limited edition versions of the Game Boy Advance SP and Game Boy Micro handheld game consoles.

Hardware design flaws

When Nintendo released the NES in the United States, the design styling was deliberately different from that of other game consoles. Nintendo wanted to distinguish its product from those of competitors, and to avoid the generally poor reputation that game consoles had acquired following the video game crash of 1983. One result of this philosophy was a front-loading zero insertion force (ZIF) cartridge socket designed to resemble the front-loading mechanism of a VCR. The ZIF connector worked quite well when both the connector and the cartridges were clean and the pins on the connector were new. Unfortunately, the ZIF connector was not truly zero insertion force. When a user inserted the cartridge into the NES, the force of pressing the cartridge down and into place bent the contact pins slightly, as well as pressing the cartridge’s ROM board back into the cartridge itself. Repeated insertion and removal of cartridges caused the pins to wear out relatively quickly, and the ZIF design proved far more prone to interference by dirt and dust than an industry-standard card edge connector. Exacerbating the problem was Nintendo’s choice of materials; the slot connector that the cartridge was actually inserted into was highly prone to corrosion. Add-on peripherals like the popular Game Genie cheat cartridge tended to further exacerbate this problem by bending the front-loading mechanism during gameplay. Recently, third-party manufacturers have been producing gold clones of the NES connector piece to replace the existing one and prevent corrosion.

Problems with the 10NES lockout chip frequently resulted in the system’s most infamous problem: the blinking red power light, in which the system appears to turn itself on and off repeatedly. The lockout chip was quite finicky, requiring precise timing in order to permit the system to boot. Dirty, aging, and bent connectors would often disrupt the timing, resulting in the blink effect. Alternatively, the console would turn on but only show a gray screen. Users attempted to solve this problem by blowing air onto the cartridge connectors, licking the edge connector, slapping the side of the system after inserting a cartridge, and/or cleaning the connectors with alcohol which, observing the back of the cartridge, was not endorsed by Nintendo. Many of the most frequent attempts to fix this problem ran the risk of damaging the cartridge and/or system. Blowing on the cartridge connectors was, in most cases, no better than removing and reinserting the cartridge, and tended to increase the rate of oxidation resulting in browning of the printed circuit board, while slapping the side of the system after inserting the cartridge could potentially damage the console. In 1989, Nintendo released an official NES Cleaning Kit to help users clean malfunctioning cartridges and consoles.

With the release of the top-loading NES 2 toward the end of the NES's lifespan, Nintendo resolved the problems by switching to a standard card edge connector, and eliminating the lockout chip. All of the Famicom systems used standard card edge connectors, as did Nintendo’s subsequent game consoles, the Super Nintendo Entertainment System and the Nintendo 64.

In response to these hardware flaws, "Nintendo Authorized Repair Centers" sprang up across the United States. According to Nintendo, the authorization program was designed to ensure that the machines were properly repaired. Nintendo would ship the necessary replacement parts only to shops that had enrolled in the authorization program. In practice, the authorization process consisted of nothing more than paying a fee to Nintendo for the privilege. In a recent trend, sites like Nintendo Repair Shop Inc. have sprung up to offer Nintendo repair parts, guides and services, that replace those formerly offered by the authorized repair centers.

Third-party licensing

Nintendo’s near monopoly on the home video game market left it with a degree of influence over the industry exceeding even that of Atari during Atari's heyday in the early 1980s. Unlike Atari, which never actively courted third-party developers (and even went to court in an attempt to force Activision to cease production of Atari 2600 games), Nintendo had anticipated and encouraged the involvement of third-party software developers—but strictly on Nintendo’s terms. To this end, a 10NES authentication chip was placed in every console, and another was placed in every officially licensed cartridge. If the console’s chip could not detect a counterpart chip inside the cartridge, the game would not load.

Nintendo combined this with a marketing campaign introducing the Nintendo Seal of Quality. Commercials featured a purple-robed wizard instructing consumers that the Nintendo Seal of Quality was the only assurance that a game was any good—and, by implication, that any game without the Seal of Quality was bad. In reality, the seal meant that the developer had paid the license fee.

The business side of this was that game developers were now forced to pay a license fee to Nintendo, to submit to Nintendo’s quality assurance process, to buy developer kits from Nintendo, and to utilize Nintendo as the manufacturer for all cartridges and packaging. Nintendo tested and manufactured all games at its own facilities (either for part of the fee or for an additional cost), reserved the right to dictate pricing, censored material it believed to be unacceptable, decided how many cartridges of each game it would manufacture, and placed limits on how many titles it would permit a publisher to produce over a given time span (five per year). This last restriction led several publishers to establish or utilize subsidiaries to circumvent Nintendo’s policies (examples including Konami’s subsidiary Ultra, and Acclaim Entertainment’s subsidiary LJN).

These practices were intended not only to keep developers on a short leash, but also to manipulate the market itself: in 1988, Nintendo started orchestrating intentional game shortages in order to increase consumer demand. Referred as "inventory management" by Nintendo of America public relations executive Peter Main, Nintendo would refuse to fill all retailer orders. Retailers, many of whom derived a large percentage of their profit from sales of Nintendo-based hardware and software (at one point, Toys "R" Us reported 17% of its sales and 22% of its profits were from Nintendo merchandise), could do little to stop these practices. In 1988, over 33 million NES cartridges were sold in the United States, but estimates suggest that the realistic demand was closer to 45 million. Because Nintendo controlled the production of all cartridges, it was able to enforce these rules on its third-party developers. These extremely restricted production runs would end up damaging several smaller software developers: even if demand for their games was high, they could only produce as much profit as Nintendo allowed.

Unlicensed games

Several companies, refusing to pay the licensing fee or having been rejected by Nintendo, found ways to circumvent the console's authentication system. Most of these companies created circuits that used a voltage spike to disable the 10NES chip in the NES. A few unlicensed games released in Europe and Australia came in the form of a dongle that would be connected to a licensed game, in order to use the licensed game’s 10NES chip for authentication.

Atari Games created a line of NES products under the name Tengen, and took a different approach. Afraid of damaging NES units and being liable for it by using the voltage spike technique, the company obtained a description of the lockout chip from the United States Patent and Trademark Office by falsely claiming that it was required to defend against present infringement claims in a legal case. Tengen then used these documents to design its Rabbit chip, which duplicated the function of the 10NES. Nintendo sued Tengen for these actions, and Tengen lost because of the fraudulent use of the published patent. Tengen’s antitrust claims against Nintendo were never finally decided.

Although successful in its suit against Tengen, Nintendo’s overall track record at suing unlicensed developers was mixed: the case of Lewis Galoob Toys, Inc. v. Nintendo of America, Inc. was found in favor of Galoob and its Game Genie device, for instance. Most unlicensed developers were eventually forced out of business or out of production by legal fees and court costs for extended lawsuits brought by Nintendo against the companies. One notable exception was Color Dreams, who produced Christian video games under the subsidiary name Wisdom Tree. This operation was never sued by Nintendo.

Following the introduction of the Sega Mega Drive, Nintendo began to face real competition in the industry, and in the early 1990s was forced to reevaluate its stance towards its developers, many of whom had begun to defect to other systems. When the console was reissued as the NES 2, the 10NES chip was omitted from the console, marking the end of Nintendo’s most notorious hold over its third-party developers.

Companies that produced unlicensed games or accessories for the Western market include Active Enterprises, American Game Cartridges, American Video Entertainment, Camerica, Codemasters, Color Dreams, Galoob, Home Entertainment Suppliers, Panesian, S.E.I., Tengen, and Wisdom Tree.

Hardware clones

Main article: Nintendo Entertainment System hardware cloneA thriving market of unlicensed NES hardware clones emerged during the heyday of the console’s popularity. Initially, such clones were popular in markets where Nintendo never issued a legitimate version of the system. In particular, the Dendy (Template:Lang-ru), an unlicensed hardware clone produced in Russia and other nations of the former Soviet Union, emerged as the most popular video game console of its time in that setting, and it enjoyed a degree of fame roughly equivalent to that experienced by the NES/Famicom in North America and Japan. The Micro Genius (Simplified Chinese: 小天才) was marketed in Southeast Asia as an alternative to the Famicom, and Samurai was the popular PAL alternative to the NES.

The unlicensed clone market has persisted, and even flourished, following Nintendo’s discontinuation of the NES. As the NES fades into memory, many such systems have adopted case designs which mimic more recent game consoles. NES clones resembling the Sega Genesis, the Super Nintendo Entertainment System, and even more recent systems like the Nintendo GameCube, the Sony PlayStation 2 and the Microsoft Xbox have been produced. Some of the more exotic of these systems have gone beyond the functionality of the original hardware, and have included variations such as a portable system with a color LCD (e.g. Pocket Famicom). Others have been produced with certain specialized markets in mind, including various "educational computer packages" which include copies of some of the NES’s educational titles and come complete with a clone of the Famicom BASIC keyboard, transforming the system into a rather primitive personal computer. These unauthorized clones have been helped by the invention of the so called NES-on-a-chip or NoaC.

As was the case with unlicensed software titles, Nintendo has typically gone to the courts to prohibit the manufacture and sale of unlicensed cloned hardware. Many of the clone vendors have included built-in copies of licensed Nintendo software, which constitutes copyright infringement in most countries. As recently as 2004, Nintendo of America has filed suits against manufacturers of the Power Player Super Joy III, an NES clone system that had been sold in North America, Europe, and Australia.

Although most hardware clones were not produced under license by Nintendo, certain companies were granted licenses to produce NES-compatible devices. The Sharp Corporation produced at least two such clones: the Twin Famicom and the SHARP 19SC111 television. The Twin Famicom was compatible with both Famicom cartridges and Famicom Disk System disks. It was available in two colors (red and black) and used hardwired controllers (as did the original Famicom), but it featured a different case design. The SHARP 19SC111 television was a television which included a built-in Famicom. A similar licensing deal was reached with Hyundai Electronics, who manufactured the system under the name Comboy in the South Korean market. This deal with Hyundai was made necessary because of the South Korean government's wide ban on all Japanese "cultural products," which remained in effect until 1998 and ensured that the only way Japanese products could legally enter the South Korean market was through licensing to a third-party (non-Japanese) distributor (see also Korean-Japanese disputes).

Technical specifications

Chassis/casing

The original Japanese Famicom was predominantly white plastic, with dark red trim. It featured a top-loading cartridge slot, and grooves on both sides of the deck in which the hardwired game controllers could be placed when not in use.

The original version of the North American NES utilized a radically different design. The NES's color scheme was two different shades of gray, with black trim. The top-loading cartridge slot was replaced with a front-loading mechanism. The slot is covered by a small, hinged door that can be opened to insert or remove a cartridge, and closed at other times. The dimensions of this model are 10" width by 8" length by 3.5" height. When opened, the cartridge slot door adds an additional 1" height to the unit.

The remodelled NES 2 uses the same basic color scheme, although the power switch is colored a bright red. Like the original Famicom, it utilizes a top-loading cartridge slot. The NES 2 is considerably more compact than the original model, measuring 6" by 7" by 1.5".

All officially licensed North American and European cartridges are 5.5" long by 4.1" wide. Japanese cartridges are shaped slightly differently, measuring only 3" in length, but 5.3" in width.

Central processing unit

For its central processing unit (CPU), the NES uses an 8-bit microprocessor produced by Ricoh based on a MOS Technology 6502 core. It incorporates custom sound hardware and a restricted DMA controller on-die. NTSC (North America and Japan) versions of the console use the Ricoh 2A03 (or RP2A03), which runs at 1.79 MHz. PAL (Europe and Australia) versions of console utilize the Ricoh 2A07 (or RP2A07), which is identical to the 2A03 save for the fact that it runs at a slower 1.66 MHz clock rate.

Memory

The NES contains 2 KiB of onboard random access memory (RAM). A game cartridge may contain expanded RAM to increase this amount. The system supports up to 49,128 bytes (just shy of 48 KiB) for read-only memory (ROM), expanded RAM, and cartridge input/output. The process of bank switching can increase this amount by orders of magnitude.

Video

The NES utilizes a custom-made picture processing unit (PPU) developed by Ricoh. The version of the processor used in NTSC models of the console, named the RP2C02, operates at 5.37 MHz, while the version used in PAL models, named the RP2C07, operates at 5.32 MHz. Both the RP2C02 and RP2C07 output composite video. Special versions of the NES's hardware designed for use in video arcades use other variations of the PPU. The PlayChoice-10 uses the RP2C03, which runs at 5.37 MHz and outputs RGB video at NTSC frequencies. Two different variations were used for Nintendo Vs. Series hardware: the RP2C04 and the RP2C05. Both of these operate at 5.37 MHz and output RGB video at NTSC frequencies. Additionally, both utilize irregular palettes to prevent easy ROM swapping of games. All variations of this PPU feature 256 bytes of on-die sprite position / attributable RAM ("OAM") and 28 bytes of on-die palette RAM to allow selection of background and sprite colors. This memory is stored on separate buses internal to the PPU. The console's 2 KiB of onboard RAM may be used for tile maps and attributes on the NES board, and 8 KiB of tile pattern ROM or RAM may be included on a cartridge. Using bank switching, virtually any amount of additional cartridge memory can be used, limited only by manufacturing costs.

The system has an available color palette of 48 colors and 5 grays. Red, green, and blue can be individually darkened at specific screen regions using carefully timed code. Up to 25 colors may be used on one scanline: a background color, four sets of three tile colors, and four sets of three sprite colors. This total does not include color de-emphasis.

A total of 64 sprites may be displayed onscreen at a given time without reloading sprites mid-screen. Sprites may be either 8 pixels by 8 pixels, or 8 pixels by 16 pixels, although the choice must be made globally and it affects all sprites. Up to eight sprites may be present on one scanline, using a flag to indicate when additional sprites are to be dropped. This flag allows the software to rotate sprite priorities, increasing maximum amount of sprites, but typically causing flicker.

The PPU allows only one scrolling layer, though horizontal scrolling can be changed on a per-scanline basis. More advanced programming methods enable the same to be done for vertical scrolling.

The standard display resolution of the NES is 256 horizontal pixels by 240 vertical pixels. Typically, games designed for NTSC-based systems had an effective resolution of only 256 by 224 pixels, as the top and bottom 8 scanlines are not visible on most television sets. For additional video memory bandwidth, it was possible to turn off the screen before the raster reached the very bottom.

Video output connections varied from one model of the console to the next. The original Japanese Famicom featured only radio frequency (RF) modulator output. When the console was released in North America and Europe, support for composite video through RCA connectors was added in addition to the RF modulator. The AV Famicom dropped the RF modulator entirely and adopted composite video output via a proprietary 12-pin "multi-out" connector first introduced for the Super Famicom / Super Nintendo Entertainment System. Conversely, the North American rereleased NES 2 most closely resembled the original model Famicom, in that it featured RF modulator output only. Finally, the PlayChoice-10 utilized an inverted RGB video output.

Audio

The NES board supported a total of five sound channels. These included two pulse wave channels of variable duty cycle (12.5%, 25%, 50%, and 75%), with a volume control of sixteen levels, and hardware pitch bending supporting frequencies ranging from 54 Hz to 28 kHz. Additional channels included one fixed-volume triangle wave channel supporting frequencies from 27 Hz to 56 kHz, one sixteen-volume level white noise channel supporting two modes (by adjusting inputs on a linear feedback shift register) at sixteen preprogrammed frequencies, and one delta pulse-width modulation channel with six bits of range, using 1-bit delta encoding at sixteen preprogrammed sample rates from 4.2 kHz to 33.5 kHz, often resulting in poor sound quality. This final channel was also capable of playing standard pulse-code modulation (PCM) sound by writing individual 7-bit values at timed intervals.

See also

| Dedicated consoles | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home |

| ||||

| Handheld | |||||

| Arcade | |||||

- List of NES games

- List of Famicom games

- List of Famicom Disk System games

- List of NES emulators

- Nintendo World Championships

References

- ^ For distribution purposes, Europe and Australasia were divided into two regions by Nintendo. The first of these regions consisted of France, the Netherlands, West Germany, Norway, Denmark and Sweden, and saw the NES released during 1986. The console was released in the second region, consisting of the United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland, and Italy, as well as Australia, and New Zealand, the following year.

- The Famicom Disk System peripheral utilized floppy diskette-based games. See here for more information.

- The original Japanese model of the Famicom included no controller ports. See here for more information.

- With 40.24 million copies sold, Super Mario Bros. is the best-selling video game of all time. It should be noted, however, that the “NES Action Set” (also known as the “NES Power Pack”), a retail set consisting of the NES deck, two game controllers, an NES Zapper, and a Super Mario Bros./Duck Hunt multicart, accounted for the majority of these sales. Super Mario Bros. 3, with 17.28 million copies sold, is the best-selling NES game that was never packaged with the NES. .

- ^ "Breaking the Ice: South Korea Lifts Ban on Japanese Culture" (html). Trends in Japan. December 7. Retrieved May 19.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=,|date=, and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); External link in|work=|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Classic Systems—Nintendo Entertainment System" (html). Nintendo. Retrieved February 11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - Atari broke off negotiations with Nintendo in response to Coleco’s unveiling of a unlicensed port of Donkey Kong for its Coleco Adam computer system. Although the game had been produced without Nintendo’s permission or support, Atari took its release as a sign that Nintendo was dealing with one of its major competitors in the market.

- "The History of the Nintendo Entertainment System or Famicom" (html). Nintendo Land. Retrieved February 12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - Burnham, Van (2001). Supercade: A Visual History of the Videogame Age, 1971–1984. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. pp. p. 375. ISBN 0-262-52420-1.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ "European information" (html). Nintendo Database. Retrieved May 4.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|work=|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - Nielsen, Martin (1997). "The Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) FAQ v3.0A" (html). ClassicGaming.com’s Museum. Retrieved January 5.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ The Collector. "The Toploader NES: Why did it fail?" (html). The NES Player. Retrieved August 23.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|work=|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ""Did you know..." Top 25 Things You May Not Have Known About the NES" (html). [http://www.nesplayer.com/ Nintendo Player. Retrieved May 19.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|work=|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - TigheKLory. "NESp" (html). Retrieved December 20.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Game Grrl" (html). Ladyada. Retrieved December 20.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); External link in|work=|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - Liedholm, Marcus and Mattias. "History of the Nintendo Entertainment System or Famicom" (html). Nintendo Land. Retrieved February 12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Nintendo Entertainment System > United States Software List" (html). Nintendo Database. Retrieved August 23.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|work=|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - Hernandez, Christopher. "Nintendo NES / Famicom" (html). Dark Watcher’s Console History. Retrieved January 5.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - Many titles produced for the Famicom Disk System were subsequently ported to cartridge format for international release. Such games include Yume Kōjō: Doki Doki Panic (rebranded as Super Mario Bros. 2) and Konami’s Castlevania series. The original version of Super Mario Bros. 2 was released for the FDS in Japan, and didn’t see an international release until Super Mario All-Stars for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System (where it was retitled Super Mario Bros.: The Lost Levels).

- Horton, Kevin. "The Infamous Lockout Chip" (html). BlueTech. Retrieved January 5.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Nutt, Christian; Turner, Benjamin (2003). "Metal Storm: All About the Hardware" (html). Nintendo Famicom--20 years of fun. Retrieved May 21.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Edwards, Benj (2005-11-07). "No More Blinkies: Replacing the NES's 72-Pin Cartridge Connector" (HTML). Vintage Computing and Gaming. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - Nelson, Rob (2003-02-12). "Nintendo Redivivus: how to resuscitate an old friend" (HTML). Ars Technica. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - Knibbs, Mark (1997-09-22). "NES Repairs" (Text). Nintendope.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - "Repairing Your NES" (HTML). Snackbar-Games.com. 2003-05-21. Retrieved 2007-06-04.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work=|name=ignored (help) - "Blinking Screen" (html). NES Player. Retrieved 6 June.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|work=|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "What is The Nintendo Repair Shop Inc?" (HTML). Nintendo Repair Shop Inc. Retrieved 2007-06-04.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - GaZZwa. "History of Videogames (part 2)" (html). Gaming World. Retrieved January 7.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - U.S. Court of Appeals, Federal Circuit (1992). "Atari Games Corp. v. Nintendo of America Inc" (html). Digital Law Online. Retrieved March 30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - Davidson, Michael. "Famicom Clones / Pirate Multicarts and Other Weirdness" (html). Obscure Pixels. Retrieved January 5.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ASSEMbler. "Sharp Nintendo Television" (html). ASSEMbler. Retrieved January 17.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|work=|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "NES Specifications" (html). Retrieved 6 June.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "NES specificaties" (html). Rgame.nl. Retrieved 6 June.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); External link in|work=|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Unisystem VS schematic" (pdf). Retrieved 6 June.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)

External links

- Template:Dmoz

- Video of Famicom features at Powet.TV

- NESWorld--An enormous archive of NES information

- NES hardware focus - Virtual Console Archive

- NES HQ--A Comprehensive Archive for NES Information

- ClassicGaming.com’s Museum – Nintendo Entertainment System (NES)--1985-1995

- Famicom World: An information site about the Japanese version of the Nintendo Entertainment System

- Nintendo Hard Number: A list of all of the model numbers for the NES and Famicom

| Nintendo video game hardware | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consoles |

| ||||||||||||

| Peripherals |

| ||||||||||||

| Arcade | |||||||||||||

| Integrated circuits | |||||||||||||

| Media | |||||||||||||