| Revision as of 22:49, 4 November 2007 view sourceGiovanni Giove (talk | contribs)3,770 edits infobox← Previous edit | Revision as of 01:43, 5 November 2007 view source Raguseo (talk | contribs)183 edits fix & partial revert, this is the second time I came upon your ridiculous editsNext edit → | ||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

| |dead=dead | |dead=dead | ||

| |birth_date={{birth date|1711|5|18}} | |birth_date={{birth date|1711|5|18}} | ||

| |birth_place = ], ] | |birth_place = ], ] | ||

| |death_date={{death date|1787|2|13}} | |death_date={{death date|1787|2|13}} | ||

| |death_place = ], ] | |death_place = ], ] | ||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

| |footnotes = | |footnotes = | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Roger Joseph Boscovich''' (see ]; ], ] – ], ]) was a ], ], ], ], ], ], and ] from ] (then an independent state, today ] in ]) who later lived in ], ] and ]. | '''Roger Joseph Boscovich''' (see ]; ], ] – ], ]) was a ], ], ], ], ], ], and ] from ] (then an independent state, today ] in ]) who later lived in ], ] and ]. | ||

| Line 82: | Line 80: | ||

| Serbs emphasize his family's origin from Montenegro<ref name=Scepanovic>Slobodan Šćepanović, О поријеклу породице и коријенима предака Руђера Бошковића, Историјски записи 3/1995, Podgorica 1995</ref> or his Orthodox religion which he abandonded, according to some primary sources, prior to his marriage. The ] based in the Serb capital ] bears his name. | Serbs emphasize his family's origin from Montenegro<ref name=Scepanovic>Slobodan Šćepanović, О поријеклу породице и коријенима предака Руђера Бошковића, Историјски записи 3/1995, Podgorica 1995</ref> or his Orthodox religion which he abandonded, according to some primary sources, prior to his marriage. The ] based in the Serb capital ] bears his name. | ||

| In Italy Boscovich is usually remembered as Italian alongside more famous contemporary scientists such as ], ], and others. He was born in a city of mixed cultural heritage ( |

In Italy Boscovich is usually remembered as Italian alongside more famous contemporary scientists such as ], ], and others. He was born in a city of mixed cultural heritage (Italic and Slavic) where upper class had an Italic/Latin (Romanic Dalmatian) identity.. His mother's family was from Italy, and he was also largely Italian both by culture and career; he moved to Italy at the age of 14, where he spent the greater part of his life. In several encyclopedias he is described as an ''Italian scientist''. | ||

| Voltaire always wrote to Boscovich in Italian as "a sign of respect"; furthermore Boscovich always said that Italy was "his real and sweet mother".<ref></ref> He used Italian for |

Voltaire always wrote to Boscovich in Italian as "a sign of respect"; furthermore Boscovich always said that Italy was "his real and sweet mother".<ref></ref> He also used Italian for his private matters. However Boscovich himself also denied being Italian: when it was suggested he was an Italian mathematician, he responded in a note to his ''Voyage astronomique et geographique'' that 'our author is a Dalmatian from Ragusa, and not an Italian'.<ref>Harris, Robin. ''Dubrovnik, A History''. London: Saqi Books, 2003. ISBN 0 86356 332 5. Dadić, Žarko. ''Ruđer Bošković'' Zagreb, 1990</ref> | ||

| ==Names in other languages== | ==Names in other languages== | ||

Revision as of 01:43, 5 November 2007

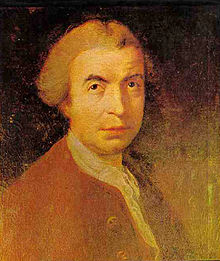

| Roger Boscovich | |

|---|---|

Portrait by R. Edge Pine, London, 1760. Portrait by R. Edge Pine, London, 1760. | |

| Born | (1711-05-18)May 18, 1711 Dubrovnik, Dalmatia |

| Died | (1787-02-13)February 13, 1787 Milan, Italy |

| Alma mater | Collegium Romanum |

| Known for | Atomic theory |

Roger Joseph Boscovich (see names in other languages; May 18, 1711 – February 13, 1787) was a physicist, astronomer, mathematician, philosopher, diplomat, poet, and Jesuit from Ragusa (then an independent state, today Dubrovnik in Croatia) who later lived in England, France and Italy.

He is famous for his atomic theory, given as a clear, precisely-formulated system utilizing principles of Newtonian mechanics. This work inspired Michael Faraday to develop field theory for electromagnetic interaction, and was even a basis for Albert Einstein's attempts for a unified field theory, according to Einstein's coworker Lancelot Law Whyte. Boscovich also gave many important contributions to astronomy, including the first geometric procedure for determining the equator of a rotating planet from three observations of a surface feature and for computing the orbit of a planet from three observations of its position. In 1753 he also discovered the absence of atmosphere on the Moon.

A crater on the Moon also bears his name: Boscovich crater.

Biography

Early years

Boscovich was born on May 18 1711 in the Republic of Ragusa, an independent republic at the time. He was the seventh child of Nikola Bošković, a merchant, who hailed from Orahov Do, near Ravno, in Herzegovina. His father died when Roger was ten, because of colic complications.

Roger's mother, Paola Bettera, was a member of a cultivated Italian merchant family. She had nine children: Roger was her eighth child and the youngest of six sons. At the age of 8 or 9, after acquiring the rudiments of reading and writing from the priest Nicola (Nikot) Nicchei of the Church of St Nicholas, Roger was sent for his schooling to the local Jesuit Collegium Regusinum. During his early studies Roger Boscovich had shown a distinct propensity for further intellectual development. He had gained a reputation at school for having an easy memory and a quick, deep mind. On September 16, 1725, Roger Boscovich left Ragusa to Rome. He was in the care of two Jesuit priests who took him to the Society of Jesus, famous for its education of youth and at that time having some 800 establishments and 200,000 pupils under its care throughout the world. We learn nothing from Boscovich himself from the time he entered the novitiate to 1731, but it was the usual practice for novices to spend the first two years not in the Collegium Romanum, but in S. Andrea delle Fratte on the Quirinal, the highest of the seven hills of Ancient Rome. There, he studied mathematics and physics; and so brilliant was his progress in these sciences that in 1740 he was appointed professor of mathematics in the college.

He was especially appropriate for this post due to his acquaintance with recent advances in science, and his skill in a classical severity of demonstration, acquired by a thorough study of the works of the Greek geometers. Several years before this appointment he had made a name for himself with an elegant solution of the problem of finding the Sun's equator and determining the period of its rotation by observation of the spots on its surface.

Middle years

Notwithstanding the arduous duties of his professorship, he found time for investigation in all the fields of physical science, and he published a very large number of dissertations, some of them of considerable length. Among the subjects were the transit of Mercury, the Aurora Borealis (corona), the figure of the Earth, the observation of the fixed stars, the inequalities in terrestrial gravitation, the application of mathematics to the theory of the telescope, the limits of certainty in astronomical observations, the solid of greatest attraction, the cycloid, the logistic curve, the theory of comets, the tides, the law of continuity, the double refraction micrometer, various problems of spherical trigonometry.

In 1742 he was consulted, with other men of science, by the Pope Benedict XIV, as to the best means of securing the stability of the dome of St. Peter's, Rome, in which a crack had been discovered. His suggestion of placing five concentric iron bands was adopted.

In 1745 Boscovich published De Viribus Vivis in which he tried to find a middle way between Isaac Newton's gravitational theory and Gottfried Leibniz's metaphysical theory of monad-points. Developing a concept of "impenetrability" as a property of hard bodies which explained their behaviour in terms of force rather than matter. Stripping atoms of their matter, impenetrability is disassociated from hardness and then put in an arbitrary relationship to elasticity. Impenetrability has a Cartesian sense that more than one point cannot occupy the same location at once.

Boscovich visited his hometown only once in 1747. After that, he never went to visit the place where he was born and grew up.

He agreed to take part in the Portuguese expedition for the survey Brazil and the measurement of a degree of the meridian, but was persuaded by the Pope to stay in Italy and to undertake a similar task there with Christopher Maire, an English Jesuit who measured an arc of two degrees between Rome and Rimini. The operation began at the end of 1750, and was completed in about two years. An account was published in 1755, under the name De Litteraria expeditione per pontificiam ditionem ad dimetiendos duos meridiani gradus a PP. Maire et Boscovicli. The value of this work was increased by a carefully prepared map of the States of the Church. A French translation appeared in 1770.

A dispute arose between Francis the Grand Duke of Tuscany and the republic of Lucca with respect to the drainage of a lake. As agent of Lucca, Boscovich was sent, in 1757, to Vienna and succeeded in bringing about a satisfactory arrangement in the matter.

In Vienna in 1758, he published his famous work, Theoria philosophiae naturalis redacta ad unicam legem virium in natura existentium (Theory of Natural philosophy derived to the single Law of forces, which exist in Nature), containing his atomic theory and his theory of forces. A second edition was published in 1763 in Venice, a third in 1922 in London, and a fourth in 1966 in the United States. A fifth edition was published in Zagreb in 1974.

Another occasion to exercise his diplomatic ability soon arose. The British government suspected that warships had been outfitted in the port of Dubrovnik for the service of France and that therefore the neutrality of Dubrovnik had been violated. Boscovich was selected to undertake an ambassadorship to London (1760), to vindicate the character of his native place and satisfy the government. This mission he discharged successfully — a credit to him and a delight to his countrymen. During his stay in England he was elected a fellow of the Royal Society.

In 1761 astronomers were preparing to observe the transit of Venus across the Sun. Under the influence of the Royal Society Boscovich decided to travel to Istanbul. He arrived late and then travelled to Poland via Bulgaria and Moldavia then proceeding to Saint Petersburg where he was elected as a member of Russian Academy of Sciences. Ill health compelled him soon to return to Italy.

Late years

In 1764 he was called to serve as the chair of mathematics at the university of Pavia, and he held this post with the directorship of the observatory of Brera in Milan, for six years.

He was invited by the Royal Society of London to undertake an expedition to California to observe the transit of Venus in 1769 again, but this was prevented by the recent decree of the Spanish government on the expulsion of the Jesuits from its dominions. Boscovich had many enemies and he was driven to frequent changes of residence. About 1777 he returned to Milan, where he kept teaching and directing the Brera observatory.

Deprived of his post by the intrigues of his associates, he was about to retire to Ragusa when in 1773 the news of the suppression of his order in Italy reached him. Uncertainty led him to accept an invitation from the King of France to come to Paris where he was appointed director of optics for the navy, with a pension of 8000 livres and a position was created for him.

He naturalized in France and stayed ten years, but his position became irksome, and at length intolerable. He, however, continued to work in the pursuit of science knowledge, and published many remarkable works. Among them was an elegant solution of the problem to determine the orbit of a comet from three observations and works on micrometer and achromatic telescopes.

In 1783 he returned to Italy, and spent two years at Bassano, occupying himself with the publication of his Opera pertinentia ad opticam et astronomiam, etc., published in 1785 in five volumes quarto.

After a visit of some months to the convent of Vallombrosa, he went to Brera in 1786 and resumed his literary labors. At that time his health was failing, his reputation was on the wane, his works did not sell, and he gradually fell prey to illness and disappointment. He died in Milan and was buried in the church of St. Maria Podone.

Further works

In addition to the works already mentioned Boscovich published Elementa universae matheseos (1754), the substance of the course of study prepared for his pupils, and a narrative of his travels entitled Giornale di un viaggio da Constantinopoli in Polonia (A diary of the journey from Constantinople to Poland) (1762), of which several editions and a French translation appeared.

Nationality controversy

The modern concept of nationality, based on ethnic concepts as language, religion, custom, etc., was developed only in the 19th century. For this reason the attribution of a definite nationality to personalities of the previous centuries, living in ethnically mixed regions, is often disputed. As a consequence Boscovich's legacy is claimed by several states, in the present case Croatia, Italy, and Serbia.

The largest Croatian institute of natural sciences and technology, based in the nation's capital bears his name. His picture was on Croatian dinar banknotes valid from 23 December 1991 till 30 May 1994, when replaced by Croatian kuna. Orahov Do, where Nikola Boscovich came from, has always been inhabited by Catholics, that for this reason are today identified as Croats. Some episodes are reported to affirm he referred to his Croatian identity.. In writings to his sister Anica, he told her he had not forgotten the Croatian language.. Also When he was in Vienna in 1757, whilst there he spotted Croatian soldiers going to the battlefields of the Seven Year's War, he immediately rode out to see them, wishing them 'Godspeed' in Croatian.. In one of his letters to his sister he wrote that in one of European cities he saw soldiers - "our Croats".

Serbs emphasize his family's origin from Montenegro or his Orthodox religion which he abandonded, according to some primary sources, prior to his marriage. The Astronomical Society Ruđer Bošković based in the Serb capital Belgrade bears his name.

In Italy Boscovich is usually remembered as Italian alongside more famous contemporary scientists such as Galileo, Alessandro Volta, and others. He was born in a city of mixed cultural heritage (Italic and Slavic) where upper class had an Italic/Latin (Romanic Dalmatian) identity.. His mother's family was from Italy, and he was also largely Italian both by culture and career; he moved to Italy at the age of 14, where he spent the greater part of his life. In several encyclopedias he is described as an Italian scientist.

Voltaire always wrote to Boscovich in Italian as "a sign of respect"; furthermore Boscovich always said that Italy was "his real and sweet mother". He also used Italian for his private matters. However Boscovich himself also denied being Italian: when it was suggested he was an Italian mathematician, he responded in a note to his Voyage astronomique et geographique that 'our author is a Dalmatian from Ragusa, and not an Italian'.

Names in other languages

- Template:Lang-it

- Template:Lang-la

- Template:Lang-hr

- Template:Lang-fr

- Template:Lang-es

- Serbian: Руђер Јосип Бошковић / Ruđer Josip Bošković

Bibliography

Boscovich published eight scientific dissertations prior to his 1744 ordination as a priest and appointment as a professor and another 14 afterwards. The following is a partial list of his publications:

- The Sunspots (1736)

- The Transit of Mercury (1737)

- The Aurora Borealis (1738)

- The Application of the Telescope in Astronomical Studies (1738)

- The Motion of the Heavenly Bodies in an Unresisting Medium (1740)

- The Different Effects of Gravity in Various Points of the Earth (1741)

- The Aberration of the Fixed Stars (1742)

- On the Ancient Villa Discovered on the Ridge of Tusculum (1745)

- De Viribus Vivis (1745)

- On the ancient Sundial and Other Certain treasures found among the Ruins (1745)

- The Theory of Natural Philosophy (1758)

See also

References

- '"Roger Joseph Boscovich'" SJ FRS, 1711 -1787 Studies of his life and work on the 250th anniversary of his birth, edited L L Whyte, George Allen and Unwin, London, 1961

- Энциклопедия для детей (астрономия). Москва: Аванта+. 1998. ISBN 5-89501-016-4.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - "Roger Joseph Boscovich". Studies in His Life and Work on the 250th Anniversary of His Birth

- "Roger Joseph Boscovich". Studies in His Life and Work on the 250th Anniversary of His Birth

- The Conflict between Atomism and Conservation Theory 1644 - 1860 by Wilson L. Scott, London and New York, 1970

- ROGER JOSEPH BOSCOVICH 1711-1787 Studies in His Life and Work on the 250th Anniversary of His Birth

- Dadić, Žarko. Ruđer Bošković (Parallel text in Croatian and English). Zagreb: Školska Knjiga, 1987

- Dadić, Žarko. Ruđer Bošković (Parallel text in Croatian and English). Zagreb: Školska Knjiga, 1987

- Harris, Robin. Dubrovnik, A History. London: Saqi Books, 2003. ISBN 0 86356 332 5

- Harris, Robin. Dubrovnik, A History. London: Saqi Books, 2003. ISBN 0 86356 332 5

- Dubrovnik

- Slobodan Šćepanović, О поријеклу породице и коријенима предака Руђера Бошковића, Историјски записи 3/1995, Podgorica 1995

- Biography of Boscovich (in Italian)

- Harris, Robin. Dubrovnik, A History. London: Saqi Books, 2003. ISBN 0 86356 332 5. Dadić, Žarko. Ruđer Bošković Zagreb, 1990

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

External links

- Roger Boscovich on Britannica 1911

- Information on Boscovich's scientific legacy and ethnic affiliation

- Ruggero Giuseppe Boscovich, by University of St. Andrews

- Roger Joseph Boscovich, by Joseph MacDonnell

- Rudjer Boscovich, by Norway's Physical Society (in PDF)

- Ruggero Giuseppe Boscovich, by Antonio Fares

- Giuseppe Boscovich, by Antonio Fares (From Arcipelago Adriatico, in Italian)

- Ruggiero Giuseppe Boscovich at "Jesuits and the Sciences"

- Ruggiero Giuseppe Boscovich in the Catholic Encyclopedia

- Bošković on Banknotes

- Latin as a literary language among the Croats by Branko Franolić - contains information on Ruđer Bošković

- Milano Astronomical Observatory

- Ruggiero Boscovich on various Croatian Dinar banknotes.

- "Roger Joseph Boscovich". Studies in His Life and Work on the 250th Anniversary of His Birth

Further reading

- Dadić, Žarko. Ruđer Bošković (Parallel text in Croatian and English). Zagreb: Školska Knjiga, 1987

- Franolić, Branko. Bošković in Britain, Journal of Croatian Studies Vol. 43, 2002 Croatian Academy of America, New York US ISSN 0075-4218

- Whyte, Lancelot Law, ed. Roger Joseph Boscovich, S.J., F.R.S., 1711-1787: Studies of His Life and Work on the 250th Anniversary of His Birth. London,: G. Allen & Unwin, 1961.

- Williams, L. Pearce. Michael Faraday, a Biography. New York,: Basic Books, 1965.

- Williams, L. Pearce. "Boscovich, Mako, Davy and Faraday." In R.J. Boscovich; Vita E Attivita Scientifica; His Life and Scientific Work, ed. Piers Bursill-Hall, 587-600. Roma: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 1993.

- Boscovich, Ruggero Giuseppe. A Theory of Natural Philosophy. Translated by J. M. Child. English ed. Cambridge, Mass.,: M. I. T. Press, 1966.

- Brush, Stephen G. The Kind of Motion We Call Heat : A History of the Kinetic Theory of Gases in the 19th Century. Vol. 6 Studies in Statistical Mechanics. New York: North-Holland Pub. Co., 1976.

- Brush, Stephen G. Statistical Physics and the Atomic Theory of Matter : From Boyle and Newton to Landau and Onsager Princeton Series in Physics. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1983.

- Bursill-Hall, Piers, ed. R.J. Boscovich; Vita E Attivita Scientifica; His Life and Scientific Work. Roma: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 1993.

- Feingold, Mordechai. "A Jesuit among Protestants: Boscovich in England C. 1745-1820." In R.J. Boscovich; Vita E Attivita Scientifica; His Life and Scientific Work, ed. Piers Bursill-Hall, 511-526. Roma: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 1993.

- Kargon, Robert. "William Rowan Hamilton, Michael Faraday, and the Revival of Boscovichean Atomism." American Journal of Physics 32, no. 10 (1964): 792-795.

- Kargon, Robert. "William Rowan Hamilton and Boscovichean Atomism." Journal of the History of Ideas 26, no. 1 (1965): 137-140.

- Katritsky, Linde. "Coleridge's Links with Leading Men of Science." Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 49, no. 2 (1995): 261-276.

- Priestley, Joseph, and Robert E. Schofield. A Scientific Autobiography of Joseph Priestley, 1733-1804; Selected Scientific Correspondence. Cambridge,: M.I.T. Press, 1966.

- Justin, Rodriguez. "Scientific Revolution Atomic Projects." Stevens Journal of Oral Traditions, no. 1 (200?): xlv-xc.

- Scott, Wilson L. "The Significance Of "Hard Bodies" In the History of Scientific Thought." Isis 50, no. 3 (1959): 199-210.

Warning: Default sort key "Boscovich, Roger" overrides earlier default sort key "{{{1}}}".

Categories: