| Revision as of 22:37, 25 November 2007 editWhisperToMe (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users661,896 editsm →People who didn't travel← Previous edit | Revision as of 22:38, 25 November 2007 edit undoWhisperToMe (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users661,896 editsm UnsourcedNext edit → | ||

| Line 133: | Line 133: | ||

| *Chris Revell, the son of Oliver "Buck" Revell, then executive assistant director of the ]; and, | *Chris Revell, the son of Oliver "Buck" Revell, then executive assistant director of the ]; and, | ||

| *Steven Greene, assistant administrator in the Office of Intelligence of the U.S. ]. | *Steven Greene, assistant administrator in the Office of Intelligence of the U.S. ]. | ||

| The alleged cancellation of tickets by high-profile passengers later fuelled rumours that intelligence agencies had advance warning of the bombing. | |||

| == Claims of responsibility == | == Claims of responsibility == | ||

Revision as of 22:38, 25 November 2007

PA 103 redirects here. For the state highway, see Pennsylvania Route 103 | |

| Occurrence | |

|---|---|

| Date | 21 December, 1988 |

| Summary | Terrorist bombing |

| Site | Lockerbie, Scotland |

| Aircraft type | Boeing 747-121 |

| Operator | Pan American World Airways |

| Registration | N739PAdisaster |

| Flight origin | London Heathrow International Airport |

| Destination | John F. Kennedy International Airport |

| Passengers | 243 |

| Crew | 16 |

| Fatalities | 270 (including 11 on ground) |

| Survivors | 0 |

Pan Am Flight 103 was Pan American World Airways' third daily scheduled transatlantic flight from London's Heathrow International Airport to New York's John F. Kennedy International Airport. On December 21, 1988, the aircraft flying this route, a Boeing 747-121 registered N739PAdisaster and named Clipper Maid of the Seas, was destroyed by a bomb, and the remains landed in and around the town of Lockerbie, Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland (55°5.7′N 3°20.3′W / 55.0950°N 3.3383°W / 55.0950; -3.3383).

An editorial in The Guardian of December 23, 1988 reported:

- "Two days before Christmas, two tides flow strongly. One—the greater tide—is the tide of peace. More nagging, bloody conflicts have been settled in 1988 than in any year since the end of the Second World War. There are forces for good abroad in the world as seldom before. There is also a tide of evil, a force of destruction. By just one of those ironies which afflict the human condition, peace came to Namibia yesterday. Meanwhile, on a Scottish hillside, the body of the Swedish UN Commissioner for Namibia was one amongst hundreds strewn across square miles of debris: a victim—supposition, but strongly based—of a random terrorist bomb which had blown a 747 to bits at 31,000 feet."

In the subsequent investigation of the crash, forensic experts determined that about 1 lb (450 g) of plastic explosive had been detonated in the airplane's forward cargo hold, triggering a sequence of events that led to the rapid destruction of the aircraft. Winds of 100 knots (190 km/h) scattered victims and debris along an 81 mile (130 km) corridor over an area of 845 square miles (2189 km²).

The death toll was 270 people from 21 countries, including 11 people in Lockerbie.

Criminal inquiry

Known as the Lockerbie bombing and the Lockerbie air disaster in the UK, it became the subject of Britain's largest criminal inquiry, led by its smallest police force, Dumfries and Galloway Constabulary. The bombing was widely regarded as an assault on a symbol of the United States, and with 189 of the victims being Americans, it stood as the deadliest terrorist attack against the United States until the September 11, 2001 attacks.

After a three-year joint investigation by the Dumfries and Galloway Constabulary and the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation, during which 15,000 witness statements were taken, indictments for murder were issued on November 13, 1991, against Abdel Basset Ali al-Megrahi, a Libyan intelligence officer and the head of security for Libyan Arab Airlines (LAA), and Lamin Khalifah Fhimah, the LAA station manager in Luqa Airport, Malta. United Nations sanctions against Libya and protracted negotiations with the Libyan leader Colonel Muammar al-Gaddafi secured the handover of the accused on April 5, 1999 to Scottish police at Camp Zeist, Netherlands, chosen as a neutral venue.

On January 31, 2001, Megrahi was convicted of murder by a panel of three Scottish judges, and sentenced to 27 years in prison. Fhimah was acquitted. Megrahi's appeal against his conviction was refused on March 14, 2002, and his application to the European Court of Human Rights was declared inadmissible in July 2003. On September 23, 2003, Megrahi applied to the Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission (SCCRC) for his conviction to be reviewed, and for his case to be referred back to the High Court for a fresh appeal. On June 28, 2007, the SCCRC announced its decision to refer the case to the Court of Criminal Appeal after it found he "may have suffered a miscarriage of justice".

Megrahi is serving his sentence in Greenock Prison, where he continues to profess his innocence.

Flight plan

Pan Am Flight 103 was a Boeing 747-100 named Clipper Maid of the Seas. The fifteenth jumbo jet ever built, it was delivered in February 1970, one month after the very first 747 had entered service with Pan Am.

On December 21, 1988, Clipper Maid of the Seas touched down at London's Heathrow International Airport at noon from San Francisco. The aircraft was parked at stand K-14, Terminal 3, was guarded for two hours by Pan Am's security company, Alert Security, but otherwise was not watched.

The first leg of Pan Am Flight 103's journey began as the Boeing 727 feeder flight, PA103A, from Frankfurt International Airport, West Germany to London Heathrow. Forty-seven of the 89 passengers on PA103A transferred at Heathrow to the Boeing 747 flight PA103 which was scheduled to fly to JFK. A Boeing 727 would have been used for the final leg of the journey from JFK to Detroit.

There were 243 passengers and 16 crew members on board, led by the pilot Captain James MacQuarrie, First Officer Raymond Wagner, and Flight Engineer Jerry Avritt. The flight was scheduled to depart at 18:00, and pushed back from the gate at 18:04, but because of a rush-hour delay, it took off from runway 27L at 18:25, flying northwest out of Heathrow, a so-called Daventry departure. Once clear of Heathrow, the crew steered due north toward Scotland. At 18:56, as the aircraft approached the border, it reached its cruising altitude of 31,000 ft (9400 m), and MacQuarrie throttled the engines back to cruising power.

At 19:00, PA103 was picked up by the Scottish Area Control Centre at Prestwick, Scotland, where it needed clearance to begin its flight across the Atlantic Ocean. Alan Topp, an air traffic controller, made contact with the clipper as it entered Scottish airspace.

Captain MacQuarrie replied: "Good evening Scottish, Clipper one zero three. We are at level three one zero." Then First Officer Wagner spoke: "Clipper 103 requesting oceanic clearance." Those were the last words heard from the aircraft.

Explosion

At 19:01, Topp watched Flight 103 approach the corner of the Solway Firth, and at 19:02, it crossed its northern coast. The aircraft appeared as a small green square with a cross at its centre showing its transponder code or "squawk"—0357 and flight level—310. The code gave Topp information about the time and height of the airliner: the last code he saw for the Clipper told him it was flying at 31,000 ft (9400 m) on a heading of 316 degrees magnetic, and at a speed of 313 knots (580 km/h) calibrated airspeed, at 19:02:46.9. Subsequent analysis of the radar returns by RSRE concluded that the aircraft was tracking 321° (grid) and travelling at a ground speed of 434 knots (804 km/h).

At that moment, the airliner's code and the cross in the middle of the square disappeared. Topp tried to make contact with Captain MacQuarrie, and asked a nearby KLM flight to do the same, but there was no reply. At first, Topp believed he was watching the flight enter a so-called zone of silence, dead space where objects are invisible to radar. Where there should have been one green square on his screen, there were four, and as the seconds passed, the squares began to fan out (Cox and Foster 1992). Comparison of the cockpit voice recorder with the radar returns showed that 8 seconds after the explosion, wreckage had a 1-nautical-mile (2 km) spread.

A minute later, the wing section containing 200,000 lb (91,000 kg) of fuel hit the ground at Sherwood Crescent, Lockerbie. The British Geological Survey at nearby Eskdalemuir, registered a seismic event measuring 1.6 on the Richter scale as all trace of two families, several houses, and the 196 ft (60 m) wing of the aircraft disappeared. A British Airways pilot, Captain Robin Chamberlain, flying the Glasgow–London shuttle near Carlisle called Scottish to report that he could see a huge fire on the ground. The destruction of PA103 continued on Topp's screen, by now full of bright squares moving eastwards with the wind.

Aircraft break up

The explosion punched a 20-inch-wide (0.5 m) hole, almost directly under the P in Pan Am, on the left side of the fuselage. The disintegration of the aircraft was rapid. Investigators from the Air Accidents Investigation Branch (AAIB) of the British Department of Transport concluded that the nose of the aircraft separated from the main section within three seconds of the explosion.

The cockpit voice recorder, a recording device in the tail section of the aircraft, was found in a field by police searchers within 24 hours of the bombing. There was no evidence of a distress call: a 180-millisecond hissing noise could be heard as the explosion destroyed the aircraft's communications centre.

After being lowered into the cockpit in Lockerbie before it was moved, and while the bodies of the flight crew were still inside it, investigators from the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) concluded that no emergency procedures had been started. The pressure control and fuel switches were both set for cruise, and the crew had not used their oxygen masks, which would have descended within five seconds of a rapid depressurisation of the aircraft (Cox and Foster 1992).

The nerve centre of a 747, from which all the navigation and communication systems are controlled, is below the cockpit, separated from the forward cargo hold by a bulkhead wall. Investigators concluded that the force of the explosion broke through this wall and shook the flight-control cables, causing the front section of the fuselage to begin to roll, pitch, and yaw.

These violent movements snapped the reinforcing belt that secured the front section to the row of windows on the left side and it began to break away. At the same time, shock waves from the blast ricocheted back from the fuselage skin in the direction of the bomb, meeting pulses still coming from the initial explosion. This produced Mach stem shock waves, calculated to be 25% faster than, and double the power of, the waves from the explosion itself (Cox and Foster, 1992). These shock waves rebounded from one side of the aircraft to the other, running down the length of the fuselage through the air-conditioning ducts and splitting the fuselage open. A section of the 747's roof several feet above the point of detonation peeled away. The Mach stem waves pulsing through the ductwork bounced off overhead luggage racks and other hard surfaces, jolting the passengers.

The power of the explosion was increased by the difference in air pressure between the inside of the aircraft, where it was kept at breathable levels, and outside, where it was about a quarter of that at sea level. The nose of the aircraft, containing the flight crew and the first class section, broke away, striking the No. 3 Pratt & Whitney engine as it snapped off.

Investigators believe that within three seconds of the explosion, the cockpit, fuselage, and No. 3 engine were falling separately. The fuselage continued moving forward and down until it reached 19,000 ft (6000 m), at which point its dive became almost vertical.

As it descended, the fuselage broke into smaller pieces, with the section attached to the wings landing first in Sherwood Crescent, where the aviation fuel inside the wings ignited, causing a fireball that destroyed several houses, and which was so intense that nothing remained of the left wing of the aircraft. Investigators were able to determine that both wings had landed in the crater only after counting the number of large steel flap drive jackscrews that were found there (Cox and Foster 1992).

Victims

Passengers and crew

All 243 passengers and 16 crew members were killed. A Scottish Fatal Accident Inquiry, which opened on October 1 1990, heard that, when the cockpit broke off, tornado-force winds tore through the fuselage, tearing clothes off passengers and turning objects like drink carts into lethal pieces of shrapnel. Because of the sudden change in air pressure, the gases inside the passengers' bodies would have expanded to four times their normal volume, causing their lungs to swell and then collapse. People and objects not fixed down would have been blown out of the aircraft at an air temperature of −46 °C (−50 °F), their 6-mile (9 km) fall lasting about two minutes (Cox and Foster 1992). Some passengers remained attached to the fuselage by their seat belts, landing in Lockerbie strapped to their seats.

Although the passengers would have lost consciousness through lack of oxygen, forensic examiners believe some of them might have regained consciousness as they fell toward oxygen-rich lower altitudes. Forensic pathologist Dr. William G. Eckert, director of the Milton Helpern International Center of Forensic Sciences at Wichita State University, who examined the autopsy evidence, told Scottish police he believed the flight crew, some of the flight attendants, and 147 other passengers survived the bomb blast and depressurization of the aircraft, and may have been alive on impact. None of these passengers showed signs of injury from the explosion itself, or from the decompression and disintegration of the aircraft. The inquest heard that a mother was found holding her baby, two friends were holding hands, and a number of passengers were found clutching crucifixes.

Dr Eckert told Scottish police that distinctive marks on Captain MacQuarrie's thumb suggested he had been hanging onto the yoke of the plane as it descended, and may have been alive when the plane crashed. The captain, first officer, flight engineer, a flight attendant, and a number of first-class passengers were found still strapped to their seats inside the nose section when it crashed in a field by a tiny church in the village of Tundergarth. The inquest heard that the flight attendant was alive when found by a farmer's wife, but died before her rescuer could summon help. A male passenger was also found alive, and medical authorities believe he might have survived had he been found earlier (Cox and Foster 1992).

See also: Free-fall § Surviving fallsStudents and families

Thirty-five students from Syracuse University and two from the State University of New York at Oswego were on board, flying home from overseas study in London. Ten of the victims were residents of Long Island—including father and son, John and Sean Mulroy—and were returning home for seasonal celebrations with families and friends, as reported by Newsday of December 27, 1988. Five members of the Dixit-Rattan family, including 3-year-old Suruchi Rattan, were flying to Detroit from New Delhi. They were supposed to be on PA67, which had left Frankfurt earlier in the day, but one of the children had fallen ill with breathing difficulties, and the pilot had taken the plane back to the gate to allow the family to disembark. The boy soon recovered, and the family was transferred to PA103 instead. Suruchi was wearing a bright red kurta and salwar—a knee-length tunic and matching trousers—for her journey. She became associated with a note left with flowers outside Lockerbie town hall:

"To the little girl in the red dress who lies here who made my flight from Frankfurt such fun. You didn't deserve this. God Bless, Chas."

Paul Avron Jeffreys, former bass player with the UK group Cockney Rebel, was on the flight with his new wife Rachel, en route to their honeymoon celebration. Jonathan White aged 33 the son of actor David White (Larry Tate on Bewitched) was also killed on Pan Am Flight 103.

American intelligence officers

There were at least four U.S. intelligence officers on the passenger list, with rumours, never confirmed, of a fifth. The presence of these men on the flight later gave rise to a number of conspiracy theories, in which one or more of them were said to have been the bombers' targets. Matthew Gannon, the CIA's deputy station chief in Beirut, Lebanon, was sitting in Clipper Class seat 14J. Major Chuck "Tiny" McKee, a senior army officer on secondment to the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) in Beirut, sat behind Gannon in the center aisle in seat 15F. Two CIA officers, believed to be acting as bodyguards to Gannon and McKee, were sitting in economy: Ronald Lariviere, a security officer from the U.S. Embassy in Beirut, was in 20H, and Daniel O'Connor, a security officer from the U.S. Embassy in Nicosia, Cyprus, sat five rows behind Lariviere in 25H, both men seated over the right wing.

The four men had flown together out of Cyprus that morning. Major McKee is believed to have been in Beirut trying to locate the American hostages held at that time by Hezbollah. After the bombing, sources close to the investigation told journalists that a map had been found in Lockerbie showing the suspected locations of the hostages, as marked by McKee, though this discovery was not confirmed in court.

Also on board, in seat 53K at the back of the plane, was 21-year-old Khalid Nazir Jaafar, who had moved from Lebanon to Detroit with his family, where his father ran a successful auto-repair business. Because of his Lebanese background, and because he was returning from having visited relatives there, Jaafar's name later figured prominently in the investigation into the bombing, as well as in a number of conspiracy theories that developed.

Lockerbie residents

On the ground, 11 Lockerbie residents were killed when the wing section hit 13 Sherwood Crescent at more than 500 mph and exploded, creating a crater 47 metres (155 ft) long and with a volume of 560 m³ (730 yd³), vaporising several houses and their foundations, and damaging 21 others so badly they had to be demolished. Four members of one family, Jack and Rosalind Somerville and their children Paul and Lynsey, died when their house at 15 Sherwood Crescent exploded. A fireball rose above the houses and moved toward the nearby Glasgow–Carlisle A74 main road, scorching cars in the southbound lanes, leading motorists and local residents to believe that there had been a meltdown at the nearby Chapelcross nuclear power station. The only house left standing intact in the area belonged to Father Patrick Keegans, Lockerbie's Roman Catholic priest.

For many days, Lockerbie residents lived with the sight of bodies in their gardens and in the streets, as forensic workers photographed and tagged the location of each body to help determine the exact position and force of the on-board explosion, by coordinating information about each passenger's assigned seat, type of injury, and where they had landed. Local resident, Bunty Galloway, told authors Geraldine Sheridan and Thomas Kenning (1993):

"A boy was lying at the bottom of the steps on to the road. A young laddie with brown socks and blue trousers on. Later that evening my son-in-law asked for a blanket to cover him. I didn't know he was dead. I gave him a lamb's wool travelling rug thinking I'd keep him warm. Two more girls were lying dead across the road, one of them bent over garden railings. It was just as though they were sleeping. The boy lay at the bottom of my stairs for days. Every time I came back to my house for clothes he was still there. 'My boy is still there,' I used to tell the waiting policeman. Eventually on Saturday I couldn't take it no more. 'You got to get my boy lifted,' I told the policeman. That night he was moved."

Despite being advised by their governments not to travel to Lockerbie, many of the passengers' relatives, most of them from the U.S., arrived there within days to identify their loved ones. Volunteers from Lockerbie set up and manned canteens, which stayed open 24 hours a day, where relatives, soldiers, police officers and social workers could find free sandwiches, hot meals, coffee, and someone to talk to. The people of the town washed, dried, and ironed every piece of clothing that was found, once the police had determined they were of no forensic value, so that as many items as possible could be returned to the relatives. The BBC's Scottish correspondent, Andrew Cassel, reported on the tenth anniversary of the bombing that the townspeople had "opened their homes and hearts" to the relatives, bearing their own losses "stoically and with enormous dignity", and that the bonds forged then continue to this day.

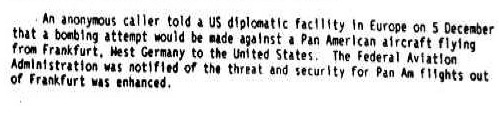

Helsinki warning

On December 5, 1988 the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) issued a security bulletin saying that on that day a man with an Arabic accent had telephoned the U.S. Embassy in Helsinki, Finland, and had told them that a Pan Am flight from Frankfurt to the United States would be blown up within the next two weeks by someone associated with the Abu Nidal Organization. He said a Finnish woman would carry the bomb on board as an unwitting courier.

The anonymous warning was taken seriously by the U.S. government. The State Department cabled the bulletin to dozens of embassies. The FAA sent it to all U.S. carriers, including Pan Am, which had charged each of the passengers a five-dollar security surcharge, promising a "program that will screen passengers, employees, airport facilities, baggage and aircraft with unrelenting thoroughness" (The Independent, March 29, 1990); the security team in Frankfurt found the warning hidden under a pile of papers on a desk the day after the bombing (Cox and Foster 1992). One of the Frankfurt security screeners, whose job it was to spot explosive devices under X-ray, told ABC News that she had first learned what Semtex was during ABC's interview with her 11 months after the bombing (Prime Time Live, November 1989).

On December 13, the warning was posted on bulletin boards in the U.S. Embassy in Moscow, and eventually distributed to the entire American community there, including journalists and businessmen. As a result, a number of people allegedly booked on carriers other than Pan Am, leaving empty seats on PA103 that were later sold cheaply in "bucket shops". PA103 investigators subsequently said the telephone warning had been a hoax and a chilling coincidence.

People who did not travel on Pan Am Flight 103

After the bombing, a number of stories emerged of people with reservations on PA103 who missed the flight:

- American musical quartet The Four Tops were returning to the States for Christmas, but were late getting out of a recording session. Angry at being too late to catch the flight, they were arguing about it when they heard it had exploded (ABC News Prime Time Live, November 30, 1989);

- Sex Pistols band member John Lydon and his wife, Nora, also had a narrow escape. "Nora and I should have been dead," he told the Scottish Sunday Mirror. "We only missed the flight because Nora hadn't packed in time. The minute we realized what happened, we just looked at each other and almost collapsed."

- Anne Applebaum was booked on the flight. However, a week before take-off, she postponed her journey by a day in order to visit Oxford; and,

- Jaswant Basuta, an American of Indian descent, got drunk in the passenger lounge after checking in, and sprinted to the gate to find the aircraft's doors had just been closed. He pleaded for the doors to be re-opened, but Pan Am duty manager Christopher Price refused. Just over an hour later, two police officers arrived in the passenger lounge to tell Basuta the flight was down and that he was a suspect, because his suitcase had been on the plane but he had not — a breach by the airline of Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) rules, which insist that the checked baggage of any passenger who failed to board be removed from the aircraft's hold. While he was being questioned, his wife, Surinder, who believed he was on the flight, made a promise to the image of a Sikh Guru on the clock in the kitchen at home that she would hire priests to perform a special 48-hour prayer session if her husband survived. On a Friday morning two months later, she and her husband Jaswant went to a Sikh temple in New York, and with the priests she had invited prayed from 10:00 a.m. on Friday until 10:00 a.m. on Sunday. "On one side of the door was death," Surinder told authors Matthew Cox and Tom Foster, "on the other, life. It's like someone pulled him back" (Cox and Foster 1992).

Others known or rumoured to have cancelled reservations on PA103 include:

- Pik Botha (former South African foreign minister), who was travelling to UN headquarters to sign the New York Accords which granted independence to Namibia; (Bernt Carlsson, the UN Commissioner for Namibia, who was travelling to the same ceremony, died on board the flight);

- John McCarthy, then U.S. Ambassador to Lebanon;

- Chris Revell, the son of Oliver "Buck" Revell, then executive assistant director of the FBI; and,

- Steven Greene, assistant administrator in the Office of Intelligence of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.

Claims of responsibility

According to a CIA analysis dated December 22, 1988, several groups were quick to claim responsibility in telephone calls in the United States and Europe:

- A male caller claimed that a group called the Guardians of the Islamic Revolution had destroyed the plane in retaliation for the U.S. shootdown of an Iranian passenger airliner the previous July.

- A caller claiming to represent the Islamic Jihad organization told ABC News in New York that the group had planted the bomb to commemorate Christmas.

- The Ulster Defense League allegedly issued a telephonic claim.

- Another anonymous caller claimed the plane had been downed by Mossad, the Israeli Intelligence service.

After finishing this list, the author stated, "We consider the claims from the Guardians of the Islamic Revolution as the most credible one received so far". The analysis concluded, "We cannot assign responsibility for this tragedy to any terrorist group at this time. We anticipate that, as often happens, many groups will seek to claim credit".

Investigation

Further information: Investigation into the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103The initial investigation into the crash site by Dumfries and Galloway police involved military and civilian helicopter surveys, satellite imaging, and a fingertip search of the area by police and soldiers. More than 10,000 pieces of debris were retrieved, tagged and entered into a computer tracking system.

The fuselage of the aircraft was reconstructed by air accident investigators, revealing a 20-inch hole consistent with an explosion in the forward cargo hold. Examination of the baggage containers revealed that the container nearest the hole had blackening, pitting, and severe damage indicating a "high-energy event" had taken place inside it. A series of test explosions were carried out to confirm the precise location and quantity of explosive used.

Fragments of a Samsonite suitcase believed to have contained the bomb were recovered, together with parts and pieces of circuit board identified as part of a Toshiba Bombeat radio cassette player, similar to that used to conceal a Semtex bomb seized by West German police from the Palestinian militant group Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine - General Command two months earlier. Items of baby clothing, which were subsequently proven to have been made in Malta, were also thought to have come from the same suitcase.

The clothes were traced to a Maltese merchant, Tony Gauci, who became a key prosecution witness, testifying that he sold the clothes to a man of Libyan appearance, whom he later identified as Abdelbaset Ali Mohmed Al Megrahi. Tony Gauci's testimony was discredited, however, in 2007, by an official report providing information not available during the original trial, that Gauci had seen a picture of al-Megrahi in a magazine which connected al-Megrahi to the bombing, a fact which could have distorted his judgement.

A circuit board fragment, found embedded in a piece of charred material, was identified as part of an electronic timer similar to that found on a Libyan intelligence agent who had been arrested 10 months previously, carrying materials for a Semtex bomb. The timer was traced through its Swiss manufacturer, Mebo, to the Libyan military and Mebo employee Ulrich Lumpert identified the fragment at al-Megrahi's trial. (On July 18, 2007 Lumpert admitted he had lied at the trial. In a sworn affidavit before a Zurich notary, Lumpert stated that he had stolen a prototype MST-13 timer PC-board from Mebo and gave it without permission on June 22, 1989, to "an official person investigating the Lockerbie case". Dr Hans Köchler, UN observer at the Lockerbie trial, who was sent a copy of Lumpert's affidavit, said: "The Scottish authorities are now obliged to investigate this situation. Not only has Mr Lumpert admitted to stealing a sample of the timer, but to the fact he gave it to an official and then lied in court".)

Investigators also discovered that an unaccompanied bag had been routed onto PA 103, via the interline baggage system, from Luqa airport on Air Malta flight KM180 to Frankfurt, and then by feeder flight PA 103A to Heathrow. This unaccompanied bag was shown at the trial to have been the bomb suitcase.

Trial and appeals

Further information: Pan Am Flight 103 bombing trialOn May 3, 2000, the trial of the two Libyans, Abdelbaset Ali Mohmed Al Megrahi and Lamin Khalifah Fhimah, accused of the 1988 PA103 bombing, began. Megrahi was convicted of murder on January 31, 2001, and was sentenced to life imprisonment. His co-accused, Fhimah, was acquitted. Megrahi's appeal against conviction was rejected on March 14, 2002.

On September 23, 2003 Megrahi's lawyers applied to the Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission (SCCRC) to have his case referred back to the Court of Criminal Appeal for a fresh appeal against conviction. The application to the SCCRC followed the publication of two reports in February 2001 and March 2002 by Professor Hans Köchler, an international observer at Camp Zeist, Netherlands appointed by the Secretary-General of the United Nations. Köchler described the decisions of the trial and appeal courts as a "spectacular miscarriage of justice." Köchler also issued a series of statements in 2003, 2005, and 2007 calling for an independent international inquiry into the case and accusing the West of "double standards in criminal justice" in relation to the Lockerbie trial on the one hand and the HIV trial in Libya on the other.

On June 28, 2007 the SCCRC announced its decision to refer Megrahi's case to the High Court for a second appeal against conviction. The SCCRC's decision was based on facts set out in an 800-page report that determined that "a miscarriage of justice may have occurred." Dr Köchler criticised the SCCRC for exonerating police, prosecutors and forensic staff from blame in respect of Megrahi's alleged wrongful conviction. He told the Glasgow Herald of June 29, 2007:

- "No officials to be blamed, simply a Maltese shopkeeper."

The second appeal will be heard by five judges in 2008 at the Court of Criminal Appeal. A procedural hearing at the Appeal Court in Edinburgh took place on October 11, 2007 when prosecution and defence lawyers discussed a number of legal issues with a panel of three judges. One of the issues concerned a number of CIA documents that were shown before the trial to the prosecution, but were not disclosed to the defence. The documents are understood to relate to the Mebo MST-13 timer that allegedly detonated the PA103 bomb. Megrahi's lawyers are also asking for documents relating to an alleged payment of $2 million made to Maltese merchant, Tony Gauci, for his testimony at the trial, which led to the conviction of Megrahi.

United Nations inquiry

In October 2007, former British diplomat Patrick Haseldine submitted this e-petition to prime minister Gordon Brown:

- "We the undersigned petition the Prime Minister to support calls for a United Nations Inquiry into the death of UN Commissioner for Namibia, Bernt Carlsson, in the 1988 Lockerbie bombing.

- "Dr Hans Köchler, UN observer at the Pan Am Flight 103 bombing trial, has described Mr al-Megrahi's conviction as a 'spectacular miscarriage of justice'. If, as now seems inevitable, the Libyan's conviction is overturned on appeal, Libya will be exonerated and a new investigation is going to be required.

- "Apartheid South Africa is the prime alternative suspect for the Lockerbie bombing - see South Africa luggage swap theory.

- "We understand that, when Libya takes its seat at the UN Security Council in January 2008, there will be calls for an immediate United Nations Inquiry into the death of UN Commissioner for Namibia, Bernt Carlsson, in the 1988 Lockerbie bombing. The other 14 UNSC members — including Britain — should support such an Inquiry and nominate Dr Köchler to conduct it."

Professor Robert Black and Iain McKie (father of Shirley McKie) were the first to sign the petition. It is open for signature until December 29, 2007.

Alleged motive

Libya has never formally admitted carrying out the 1988 Lockerbie bombing. In a letter to the United Nations it merely "accepted responsibility for the actions of its officials".

The motive that is generally attributed to Libya can be traced back to a series of military confrontations with the US Navy that took place in the 1980s in the Gulf of Sidra, the whole of which Libya claimed as its territorial waters. First, there was the Gulf of Sidra incident (1981) when two Libyan fighter aircraft were shot down. Then, two Libyan radio ships were sunk in the Gulf of Sidra. Later, on March 23, 1986 a Libyan Navy patrol boat was sunk in the Gulf of Sidra, followed by the sinking of another Libyan vessel on March 25, 1986. The Libyan leader, Muammar al-Gaddafi, was accused of retaliating to these sinkings by ordering the bombing of West Berlin nightclub, La Belle, that was frequented by U.S. soldiers and which killed three and injured 230.

The CIA's alleged interception of an incriminatory message from Libya to its embassy in East Berlin provided U.S. president Ronald Reagan with the justification for USAF warplanes to launch Operation El Dorado Canyon on April 15, 1986 from British bases—the first U.S. military strikes from Britain since World War II—against Tripoli and Benghazi, Libya. Among dozens of Libyan military and civilian casualties, the air strikes killed Hanna Gaddafi, a baby girl Gaddafi claimed to have adopted. To avenge his daughter's death, Gaddafi is said to have sponsored the September 1986 hijacking of Pan Am Flight 73 in Karachi, Pakistan.

Compensation from Libya

On May 29, 2002, Libya offered up to US$2.7 billion to settle claims by the families of the 270 killed in the Lockerbie bombing, representing US$10 million per family. The Libyan offer was that:

- 40% of the money would be released when United Nations sanctions, suspended in 1999, were cancelled;

- another 40% when U.S. trade sanctions were lifted; and

- the final 20% when the U.S. State Department removed Libya from its list of states sponsoring terrorism.

Jim Kreindler of New York law firm, Kreindler & Kreindler, which orchestrated the settlement, said:

"These are uncharted waters. It is the first time that any of the states designated as sponsors of terrorism have offered compensation to families of terror victims."

The U.S. State Department maintained that it was not directly involved. "Some families want cash, others say it is blood money," said a State Department official.

Compensation for the families of the PA103 victims was among the steps set by the UN for lifting its sanctions against Libya. Other requirements included a formal denunciation of terrorism—which Libya said it had already made—and "accepting responsibility for the actions of its officials".

Over 18 months later, on December 5, 2003, Jim Kreindler revealed that his Park Avenue law firm would receive an initial contingency fee of around US$1 million from each of the 128 American families Kreindler represents. The firm's fees could exceed US$300 million eventually. But Kreindler argued:

"Over the past seven years we have had a dedicated team working tirelessly on this and we deserve the contingency fee we have worked so hard for, and I think we have provided the relatives with value for money."

Another top legal firm in the U.S., Speiser Krause, which represented 60 relatives, of whom half were UK families, was understood to have concluded contingency deals securing them fees of between 28 and 35% of individual settlements. Frank Granito of Speiser Krause commented:

"Sure the rewards in the U.S. are more substantial than anywhere else in the world but nobody has questioned the fee whilst the work has been going on, it is only now as we approach a resolution when the criticism comes your way."

On August 15, 2003, Libya's UN ambassador, Ahmed Own, submitted a letter to the UN Security Council formally accepting "responsibility for the actions of its officials" in relation to the Lockerbie bombing. The Libyan government then proceeded to pay compensation to each family of US$8 million (from which legal fees of about US$2.5 million were deducted) and, as a result, the UN cancelled the sanctions that had been suspended four years earlier, and U.S. trade sanctions were lifted. A further US$2 million would have gone to each family had the U.S. State Department removed Libya from its list of states regarded as supporting international terrorism, but as this did not happen by the deadline set by Libya, the Libyan Central Bank withdrew the remaining US$540 million in April 2005 from the escrow account in Switzerland through which the earlier US$2.16 billion compensation for the victims' families had been paid. The United States announced resumption of full diplomatic relations with Libya after deciding to remove it from its list of countries that support terrorism on May 15, 2006.

Libya's acceptance of responsibility may have amounted to a business deal aimed at having the sanctions overturned, rather than an admission of guilt. On February 24, 2004, Libyan Prime Minister Shukri Ghanem stated in a BBC Radio 4 interview that his country had paid the compensation as the "price for peace" and to secure the lifting of sanctions. Asked if Libya did not accept guilt, he said, "I agree with that." He also said there was no evidence to link Libya with the April 1984 shooting of police officer Yvonne Fletcher outside the Libyan Embassy in London. Gaddafi later retracted Ghanem's comments, under pressure from Washington and London.

A civil action against Libya continues on behalf of Pan Am, which went bankrupt partly as a result of the attack. The airline is seeking $4.5 billion for the loss of the aircraft and the effect on the airline's business.

In the wake of the SCCRC's June 2007 decision, there have been suggestions that, if Megrahi's second appeal is successful and his conviction is overturned, Libya could seek to recover the $2.16 billion compensation paid to the relatives.

Alternative theories

Main article: Alternative theories into the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103Two controversial PA103 topics appear in the alternative theories article:

Seven alternative theories', which dispute the guilt of Megrahi and/or the responsibility of Libya for the PA103 bombing, are examined in some detail:

- CIA in Lockerbie

- Iran, the PFLP-GC, and operation Autumn Leaves

- Iran and the London angle

- Libya and Abu Nidal

- CIA-protected suitcase theory

- Radio detonation

- South Africa luggage swap theory

Epilogue from the president's commission

On September 29, 1989, President Bush appointed Ann McLaughlin Korologos, former Secretary of Labor, as chair of the President's Commission on Aviation Security and Terrorism (PCAST) to review and report on aviation security policy in the light of the sabotage of flight PA103. Mrs Korologos and the PCAST team (Senator Alfonse D'Amato, Senator Frank Lautenberg, Representative John Paul Hammerschmidt, Representative James Oberstar, General Thomas Richards, deputy commander of U.S. forces in West Germany, and Edward Hidalgo, former Secretary of the U.S. Navy) submitted their report, with its 64 recommendations, on May 15, 1990. The PCAST chairman also handed a sealed envelope to the President which was widely believed to apportion blame for the PA103 bombing. Extensively covered in The Guardian the next day, the PCAST report concluded:

- "National will and the moral courage to exercise it are the ultimate means of defeating terrorism. The Commission recommends a more vigorous policy that not only pursues and punishes terrorists, but also makes state sponsors of terrorism pay a price for their actions."

Before submitting their report, the PCAST members met a group of British PA103 relatives at the U.S. embassy in London on February 12, 1990. Twelve years later, on July 11, 2002, Scottish M.P. Tam Dalyell reminded the House of Commons of a controversial statement made at that 1990 embassy meeting by a PCAST member to one of the British relatives, Martin Cadman:

"Your government and ours know exactly what happened. But they're never going to tell."

The statement first came to public attention in the 1994 documentary film The Maltese Double Cross – Lockerbie and was published in both The Guardian of July 29, 1995, and a special report from Private Eye magazine entitled Lockerbie, the flight from justice May/June 2001. Dalyell asserted in Parliament that the statement had never been refuted.

Memorials

There are a number of private and public memorials to the PA103 victims. Dark Elegy is the work of sculptor Susan Lowenstein of Long Island, whose son Alexander, then 21, was a passenger on the flight. The work consists of 43 nude statues of the wives and mothers who lost a husband or a child. Inside each sculpture there is a personal memento of the victim.

U.S. President Bill Clinton dedicated a Memorial Cairn to the victims at Arlington National Cemetery on November 3, 1995, and there are similar memorials at Syracuse University; Dryfesdale Cemetery, near Lockerbie; and in Sherwood Crescent, Lockerbie.

Syracuse University holds a memorial week every year called "Remembrance Week" to commemorate its 35 lost students. Every December 21, a service is held in the university's chapel at 2:03 p.m. (19:03 UTC), marking the moment the aircraft exploded. The university also awards university tuition fees to two students from Lockerbie Academy each year, in the form of its Lockerbie scholarship. In addition, the university annually awards 35 scholarships to seniors to honor each of the 35 students killed. The Remembrance Scholarships are among the highest honors a Syracuse undergraduate can receive.

The main UK memorial is at Dryfesdale Cemetery about a mile west of Lockerbie. There is a semicircular stone wall in the garden of remembrance with the names and nationalities of all the victims along with individual funeral stones and memorials. Inside the chapel at Dryfesdale there is a book of remembrance. There are memorials in Lockerbie and Moffat Roman Catholic churches, where plaques list the names of all 270 victims. In Lockerbie Town Hall Council Chambers, there is a stained-glass window depicting flags of the 21 different countries whose citizens lost their lives in the disaster. There is also a book of remembrance at Lockerbie public library and another at Tundergarth Church.

Depictions in media

A 1990 HBO made-for-TV movie, The Tragedy of Flight 103: The Inside Story, depicts the events leading to the bombing.

Aftermath depicted in the stage play The Women of Lockerbie by Deborah Brevoort was awarded the silver medal in the Onassis International Playwriting Competition in 2001.

It was announced in March 2007 that a movie based on the novel The Boy Who Fell Out of the Sky by Ken Dornstein based on the events of the bombing will be produced.

References

- "FAA Registry (N739PA)". Federal Aviation Administration.

- "FAA Registry (N739PA)". Federal Aviation Administration.

- "One view from a desolate hillside".

- "referral of Megrahi case".

- "The Washington Post".

- "Air Accidents Investigation Branch website" (PDF).

- "The Guardian".

- "AAIB website" (PDF).

- "Aviation Safety website".

- "VPAF103 (American families') website".

- "AAIB website" (PDF).

- "Lockerbie: BBC news report".

- "BBC news".

- "The Guardian".

- "www.anneapplebaum.com/other/1998/12_20_tel_lockerbie.html".

- The night death rained down from the skies

- "VPAF103 article on Bernt Carlsson".

- "CIA document".

- "CIA document".

- Official report discredits Tony Gauci's testimony

- Vital Lockerbie evidence 'was tampered with'

- Probe into Lockerbie timer claims

- "BBC news".

- "Dr Hans Köchler's statement, August 2003".

- "Dr Hans Köchler's statement, October 2005".

- "Double standards in criminal justice: Pan Am Flight 103 v. HIV trial in Libya" (PDF).

- "SCCRC refers Megrahi's case for second appeal".

- "SCCRC decides "a miscarriage of justice may have occurred"".

- "Statement by Dr Hans Köchler on SCCRC decision, 29 June 2007".

- Lockerbie bomber in fresh appeal

- "'Secret' Lockerbie report claim".

- Fresh doubts on Lockerbie conviction The Guardian October 3, 2007

- Call for United Nations Inquiry into death of UN Commissioner for Namibia, Bernt Carlsson, in 1988 Lockerbie bombing

- "Security Council lifts sanctions imposed on Libya after terrorist bombings of Pan Am 103 and UTA 772".

- "Press statement by Larry Speakes, 24 March 1986".

- "Libyan craft fired upon, 25 March 1986".

- "BBC report of La Belle bombing".

- "USAF bombing of Libya, 1986".

- "BBC news".

- Revealed: Gaddafi's air massacre plot

- "Security Council lifts sanctions imposed on Libya after terrorist bombings of Pan Am Flight 103 and UTA Flight 772".

- "CNN archives".

- "Libyan government website".

- "The Scotsman".

- "BBC news".

- "BBC Radio 4, [[February 24]], [[2004]]".

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - "Case Studies of Domestic Terrorism".

- "Libyans want their £1.4bn payout back".

- "VPAF103 website".

- "Arlington national cemetery".

- "made-for-TV movie".

- "proposed Warner Bros movie".

See also

- Aerolinee Itavia Flight 870

- Air India Flight 182

- Alternative theories of the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103

- Investigation into the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103

- List of accidents and incidents on commercial airliners

- List of terrorist incidents

- Pan Am Flight 103 bombing trial

- Hans Köchler's Lockerbie trial observer mission

- Pan Am Flight 73

- UTA Flight 772

Sources

- Emerson, Steven, and Duffy, Brian. (1990) The Fall of Pan Am 103: Inside the Lockerbie Investigation, ISBN 0-399-13521-9

- Cox, Matthew, and Foster, Tom. (1992) Their Darkest Day: The Tragedy of Pan Am 103, ISBN 0-8021-1382-6

- Johnstone, David. (1989) Lockerbie: The True Story

- Sheridan, Geraldine, and Kenning, Thomas. (1993) Survivors: Lockerbie, Pan Books, ISBN 0-330-32853-0

- Goddard, Donald, and Coleman, Lester. (1993) Trail of the Octopus, ISBN 0-451-18184-0

- Ashton, John, and Ferguson, Ian. (2001) Cover-up of Convenience: The Hidden Scandal of Lockerbie, ISBN 1-84018-389-6

- Brown, David A., "Investigators Expand Search for Debris From Bombed 747", Aviation Week and Space Technology, vol. 130, no. 25, pp 26–27, January 9 1989

- Shifrin, Carole A., "British Issue Report on Flight 103, Urge Study on Reducing Effects of Explosions", Aviation Week and Space Technology, vol. 133, no. 12, pp 128–129, September 7 1990

- Scottish Panel Challenges Lockerbie Conviction New York Times, 29 November 2007

- The Scottish indictment against Megrahi and Fhimah, November 13, 1991, retrieved February 27 2005

- The U.S. indictment against Megrahi and Fhimah, November 13 1991, retrieved February 26 2005

- The Scottish judges, retrieved February 26 2005

- The verdict against Megrahi and Fhimah, issued January 31 2001, retrieved February 26 2005

- "No:2/9—Boeing 747-121, N739PA, at Lockerbie, Dumfriesshire, Scotland", Air Accident Investigation Branch (AAIB) report, retrieved February 27 2005

- The position of the bomb, AAIB report, Appendix F (pdf), retrieved February 27 2005

- "Mach stem shock wave effects", AAIB report, Appendix G (pdf), retrieved February 27 2005

- Aviation Safety Network summary report, retrieved February 27 2005

- Graphic of how the aircraft was destroyed, Aviation Safety Network, retrieved February 27 2005

- The cost of the trial, retrieved February 26 2005

- The judgment in Megrahi's appeal, March 14 2002, retrieved February 26 2005

- United Nations Security Council Resolution 731 (1992), January 21 1992, retrieved February 26 2005

- United Nations Security Council Resolution 748 (1992), January 21 1992, retrieved February 26 2005

- United Nations Security Council Resolution 883 (1993), November 11 1993, retrieved February 26 2005

- In-depth pages on the trial, BBC News, retrieved February 26 2005

- "Lessons from Lockerbie, ten years later", BBC News, retrieved February 26 2005

- The Lockerbie Trial, retrieved February 26 2005

- "Pan Am 103: Why Did They Die?", by Roy Rowan, Time Magazine, April 27 1992, retrieved February 25 2005

- "Time Trail: Lockerbie", a collection of stories about the bombing from Time Magazine, retrieved February 25 2005

- Information about the MST-13 timers, written by MEBO, the Swiss manufacturers, August 19 1999, retrieved February 25 2005

- "Lockerbie appeal hears key witness", BBC News, February 13 2002, retrieved February 26 2005

- "Lockerbie bomber loses appeal", BBC News, March 14 2002, retrieved February 26 2005

- "Lockerbie bomber to fight jail move", by Lucy Adams, The Herald, February 25 2005, retrieved February 26 2005

- Website set up by supporters of Megrahi, not recently updated, retrieved February 27 2005

- Abu Nidal behind Lockerbie, says aide, CNN, August 23 2002, retrieved February 27 2005

- "Court told how jet's radar blip broke up at 7.02pm" by Ian Black and Gerard Seenan, May 4 2000, The Guardian, retrieved February 28 2005

- "Families see radar track of Flight 103's last moments", by Edith M. Lederer, Associated Press, October 2 1990, retrieved February 28 2005

- "Lockerbie, 10 years on: Reporter's reflections" by Andrew Cassel, BBC News, December 21 1998

- Libya offers $2.7 billion Lockerbie settlement by Patrick Rizzo, The Namibian, May 29 2002

- "Libya takes back its £500 m fund for Lockerbie bereaved" by James Kirkup, The Scotsman, April 11 2005

- "Censored!!", an extract from Trail of the Octopus by Lester Coleman

- "Taking the blame" by Paul Foot, a review of Lester Coleman's book

- "On the trail of terror," by Brian Duffy, U.S. News & World Report, November 18, 1989

- "Flight 103," ABC News Prime Time Live, November 30, 1989

- "Lockerbie bomb bore 'Libyan signature'," by Leonard Doyle, The Independent, December 19, 1990

- "Unwitting Accomplices?", Barron's, December 17, 1989

- "Timer admission in Lockerbie trial" by Gerard Seenan, June 21, 2000

- Mr. Waldegrave, "House of Commons Hansard Debates" in The United Kingdom Parliament, 19 April 1990, retrieved 16 June 2005

- Thatcher, M. The Downing Street Years, 1993.

- Koechler, H., and Jason Subler (eds.), The Lockerbie Trial. Documents Related to the I.P.O. Observer Mission. Studies in International Relations, Vol. XXVII. Vienna: International Progress Organization, 2002, ISBN 3-900704-21-X.

- "Scottish Court in the Netherlands 2000-2002", Web site documenting the observer mission of Dr. Hans Koechler, appointed by UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan as international observer at the Lockerbie trial, regularly updated, International Progress Organization, retrieved 2005

- Lockerbie & Moffat RC Church Website, Lockerbie Disaster Plaque

- Lockerbie & Moffat RC Church Website, Stained Glass at Council Chambers

Further reading

- Cohen, Dan and Susan. (2000) Pan Am 103: the Bombing, the Betrayals, and a Bereaved Family's Search for Justice, ISBN 0-451-20270-8

- Dornstein, Ken. (2006) The Boy Who Fell Out of the Sky, ISBN 0-375-50359-5

- Leppard, David. (1992) On the Trail of Terror

- Marquise, Richard A. (2006) Scotbom: Evidence and the Lockerbie Investigation, ISBN 978-0-87586-449-5

- Köchler, Hans, and Jason Subler (eds.). (2002) The Lockerbie Trial. Documents related to the I.P.O. Observer Mission. Studies in International Relations, XXVII, ISBN 390070421X

- Report of the President's Commission on Aviation Security and Terrorism, May 15, 1990, U.S. Government Printing Office, 0-266-884

External links

- Archive.org cache of The Pan Am 103 Crash Website Collected information on Pan Am 103 1995–2002

- Syracuse University Pan Am Flight 103 archive

- Syracuse College of Law Lockerbie trial website

- A PA103 timeline, The Washington Post

- A PA103 timeline, Syracuse University

- Article about victim Gretchen Dater and 9/11 victim Jeremy Glick, who both attended the same New Jersey school

- A private investigator's view that terrorism did not destroy PA103

- "Report on and evaluation of the Lockerbie trial conducted by the special Scottish Court in the Netherlands at Kamp van Zeist" by Dr. Hans Köchler, February 3 2001

- "Report on the appeal proceedings at the Scottish Court in the Netherlands (Lockerbie Court)" by Dr. Hans Köchler, International Progress Organization, March 26 2002

- Police chief—Lockerbie evidence was faked, The Scotsman August 28 2005

- Defense Intelligence Agency Redacted Pan Am Report (response to a FOIA, 11 MB PDF)

- From Lockerbie to Camp Zeist: The Pan Am 103 Trial

- Pan Am Flight 103, CBS News

- "The New York Times on the Libya-Pan Am 103 Case: A Study in Propaganda Service" Center for Research on Globalization, Québec, Canada

- Inconvenient Truths, Hugh Miles, London Review of Books

- The Lockerbie disaster

- Pre-disaster photos of N739PA, Airliners.net

- Seat map of Pan Am 103

- Lockerbie bombing suspects arraigned in Netherlands, CNN