| Revision as of 00:24, 10 August 2005 view sourceVizcarra (talk | contribs)10,395 edits Rv, again. See discussion← Previous edit | Revision as of 16:35, 10 August 2005 view source Vizcarra (talk | contribs)10,395 edits Rv, again. See discussionNext edit → |

| (One intermediate revision by one other user not shown) | |

| (No difference) | |

Revision as of 16:35, 10 August 2005

This article describes the development and history of traditional anti-Semitism. A separate article exists on the more controversial concept of the New anti-Semitism.Anti-Semitism (alternatively spelled antisemitism) is hostility towards or prejudice against Jews, which can range from individual hatred to institutionalized violent persecution, of which the highly explicit ideology of Adolf Hitler's National Socialism was the most extreme form.

Anti-Semitism has historically taken two different forms:

- Religious anti-Semitism. Before the 19th century, most anti-Semitism was primarily religious in nature, based on Christian or Islamic interactions with and interpretations of Judaism. Since Judaism was the generally the largest minority religion in Christian Europe and much of the Islamic world, Jews were often the primary targets of religiously-motivated violence and persecution from Christian and Islamic rulers. Unlike anti-Semitism in general, this form of prejudice is directed at the religion itself, and so generally does not affect those of Jewish ancestry who have converted to another religion, although the case of Conversos in Spain was a notable exception. Laws banning Jewish religious practices may be rooted in religious anti-Semitism, as were the expulsions of the Jews that happened throughout the Middle Ages.

- Racial anti-Semitism, a kind of xenophobia. With its origins in the anthropological ideas of race that started during the Enlightenment, racial anti-Semitism became the dominant form of anti-Semitism from the late 19th century through today. Racial anti-Semitism replaced the belief that the religion of Judaism was to be hated with the idea that the Jews themselves were a racially distinct group, regardless of their religious practice, and that they were inferior or worthy of animosity. With the rise of racial anti-Semitism, conspiracy theories about Jewish plots in which Jews were somehow acting in concert to dominate the world became a popular form of anti-Semitic expression.

Some analysts and Jewish groups believe that there is a distinctly new form of late 20th century anti-Semitism that borrows language and concepts from anti-Zionism, but that attacks Jews as a group, rather than Israel as a country. This belief remains controversal, and is covered in the article on New anti-Semitism.

Etymology and usage

The word antisemitic or antisemitisch was probably first used in 1860 by the Jewish scholar Moritz Steinschneider in the phrase "antisemitic prejudices" ("antisemitischen Vorurtheile"). Steinschneider used this phrase to characterize Ernest Renan's ideas about Semitic racial traits. These ideas about "Semitic races" , and how they were inferior to "Aryan races", became quite widespread in Europe in the second half of the 19th century. Especially the Prussian nationalistic historian Heinrich von Treitschke did much to promote this form of racism. In Treitschke's writings Semitic was practically synonomous with Jewish. When the political writer Wilhelm Marr coined the German word Antisemitismus in 1879, its meaning was identical to Jew-hatred or Judenhass. The new word antisemitism was used merely to make Jew-hatred seem rational and sanctioned by scientific knowledge. However, it was never intended to eliminate the concept of hatred towards Jews based on the Christian conspiracies and legends so popular with the general population. In his book, "The Way to Victory of Germanicism over Judaism" (1879), Marr took up secular racist ideas of Arthur de Gobineau's "An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races" (1853, though direct influence is debatable). Marr's book became very popular, and in the same year he founded the "League of Anti-Semites" ("Antisemiten-Liga"), the first German organization committed specifically to combatting the alleged threat to Germany posed by the Jews, and advocating their forced removal from the country.

So far as can be ascertained, the word was first printed in 1881. In that year Marr published "Zwanglose Antisemitische Hefte," and Wilhelm Scherer used the term "Antisemiten" in the "Neue Freie Presse" of January. The related word semitism was coined around 1885. See also the coinage of the term "Palestinian" by Germans to refer to the nation or people known as Jews, as distinct from the religion of Judaism.

Despite the use of the prefix "anti," the terms Semitic and Anti-Semitic are not antonyms. To avoid the confusion of the misnomer, many scholars on the subject (such as Emil Fackenheim of the Hebrew University) now favor the unhyphenated term antisemitism. Yehuda Bauer articulated this view in his writings and lectures: (the term) "Antisemitism, especially in its hyphenated spelling, is inane nonsense, because there is no Semitism that you can be anti to." , also in his A History of the Holocaust, p.52)

The term anti-Semitism has historically referred to prejudice towards Jews alone, and this was the only use of this word for more than a century. It does not traditionally refer to prejudice toward other people who speak Semitic languages (e.g. Arabs or Assyrians). Bernard Lewis, Professor of Near Eastern Studies Emeritus at Princeton University, says that "Anti-Semitism has never anywhere been concerned with anyone but Jews."

In recent decades certain pro-Arabists have argued that the term should be extended to include prejudice against Arabs, Anti-Arabism, in the context of accusations of Arab anti-Semitism. The argument for such extension comes out of the claim that since the Semitic linguistic family includes Arabic, Hebrew and Aramaic languages, and the historical term "Semite" refers to all those who consider themselves decendents of the Biblical Shem, anti-Semitism should be likewise inclusive. This usage is not generally accepted.

Definitions of the term

Though the general definition of anti-Semitism is hostility or prejudice towards Jews, a number of authorities have developed more formal definitions. Holocaust scholar and CUNY professor Helen Fein's definition has been particularly influential. She defines anti-Semitism as "a persisting latent structure of hostile beliefs towards Jews as a collective manifested in individuals as attitudes, and in culture as myth, ideology, folklore and imagery, and in actions – social or legal discrimination, political mobilisation against the Jews, and collective or state violence – which results in and/or is designed to distance, displace, or destroy Jews as Jews."

Professor Dietz Bering of the University of Cologne further expanded on Professor Fein's definition by describing the structure of anti-Semitic beliefs. To anti-Semites: "Jews are not only partially but totally bad by nature, that is, their bad traits are incorrigible. Because of this bad nature: (1) Jews have to be seen not as individuals but as a collective. (2) Jews remain essentially alien in the surrounding societies. (3) Jews bring disaster on their 'host societies' or on the whole world, they are doing it secretly, therefore the anti-Semites feel obliged to unmask the conspiratorial, bad Jewish character."

In 2005, the European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia (EUMC), part of the Council of Europe, developed a working definition: "Antisemitism is a certain perception of Jews, which may be expressed as hatred toward Jews. Rhetorical and physical manifestations of antisemitism are directed toward Jewish or non-Jewish individuals and/or their property, toward Jewish community institutions and religious facilities. In addition, such manifestations could also target the state of Israel, conceived as a Jewish collectivity. Antisemitism frequently charges Jews with conspiring to harm humanity, and it is often used to blame Jews for 'why things go wrong'."

The EUMC then listed "contemporary examples of anti-Semitism in public life, the media, schools, the workplace, and in the religious sphere." These included: Making mendacious, dehumanizing, demonizing, or stereotypical allegations about Jews; accusing Jews as a people of being responsible for real or imagines wrongdoing committed by a single Jewish person or group; denying the Holocaust; and accusing Jewish citizens of being more loyal to Israel, or to the alleged priorities of Jews worldwide, than to the interests of their own nations. The EUMC also discussed was in which attacking Israel could be anti-Semitic, depending on the context, see anti-Zionism below.

Roman and Greek anti-Judaism

Prejudice against Jews can be traced back to the Graeco-Roman period and the rise of Hellenistic culture. Most Jews rejected efforts to assimilate them into the dominant Greek (and later Roman) culture, and their religious practices, which conflicted with established norms, were perceived as being backward and primitive. Gaius Cornelius Tacitus, for example, writes disparagingly of many real and imagined practices of the Jews, while there are numerous accounts of circumcision being described as barbarous.

Throughout their diaspora, Jews tended to live in separate communities, in which they could practice their religion. This led to charges of elitism, as appear in the writings of Cicero. As a minority, Jews were also dependent on the goodwill of the authorities, though this was considered irksome to the indigenous population, which regarded any vestiges of autonomy among the local Jewish communities as reminders of their subject status to a foreign empire. Nevertheless, this did not always mean that opposition to Jewish involvement in local affairs was anti-Semitic. In 411 BCE, an Egyptian mob destroyed the Jewish temple at Elephantine in Egypt, but many historians argue that this was provoked by anti-Persian sentiment, rather than by anti-Semitism per se — the Jews, who were protected by the imperial power, were perceived as being its representatives.

The enormous and influential Jewish community in the ancient Egyptian port city of Alexandria saw manifestations of an unusual brand of anti-Semitism in which the local pagan populace rejected the biblical narrative of the Exodus as being anti-Egyptian. Accordingly, a number of works were produced to provide an "Egyptian version" of what "really happened": the Jews were a group of sickly lepers that was expelled from Egypt (see Manetho, Apion). This was also used to account for Jewish practices — they were so sickly that they could not even wander in the desert for more than six days at a time, requiring a seventh day to rest, hence the origin of the Sabbath. It was these charges that led to Philo's apologetic account of Judaism and Jewish history, which was so influential in the development of early church doctrine. Ancient anti-semitic tales were also picked apart in Josephus Flavius' pamphlet Against Apion.

Religious Antisemitism

Main article: Christianity and anti-SemitismAnti-Judaism in the New Testament

Christian theological anti-Semitism was stimulated by the New Testament's replacement theology (or supersessionism), which taught that with the coming of Jesus a new covenant has rendered obsolete and has superseded the religion of Judaism. It was believed that "the perfidious Jews", as a people, were responsible for the death of Jesus. A number of Christian preachers, particularly in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, additionally taught that religious Jews "choose to follow a faith that they actually know is false" out of a desire to offend God.

Examples of passages in the New Testament that are seen as anti-Semitic, or have been used for anti-Semitic purposes:

- Jesus said to them , "You are of your father the devil, and your will is to do your father's desires. He was a murderer from the beginning, and has nothing to do with the truth, because there is no truth in him. . . . He who is of God hears the words of God; the reason why you do not hear them is you are not of God." (John 8:44-47)

- You stiff-necked people, uncircumcised in heart and ears, you always resist the Holy Spirit. As your fathers did, so do you. Which of the prophets did not your fathers persecute? And they killed those who announced beforehand the coming of the Righteous One, whom you have now betrayed and murdered, you who received the law as delivered by angels and did not keep it. (Acts 7:51-53)

- Behold, I will make those of the synagogue of Satan who say that they are Jews and are not, but lie -- behold, I will make them come and bow down before your feet, and learn that I have loved you. (Revelation 2:9).

Most biblical scholars hold that verses like these reflect the Jewish / Christian tensions that were emerging in the late first or early second century, and do not originate with Jesus (for whom such a distinction would have been incomprehensible). Today, the major Christian denominations de-emphasize verses such as these, and reject their use by anti-Semites.

Early Christianity

Prejudice against Jews in the Roman Empire was formalized in 438, when the Code of Theodosius II established Christianity as the only legal religion in the Roman Empire, although already as early as 305, in Elvira, a Spanish town in Andalusia, the first known laws of any church council against Jews appeared. Christian women were forbidden to marry Jews unless the Jew first converted to Christianity. Jews were forbidden to extend hospitality to Christians. Jews could not keep Christian concubines and were forbidden to bless the fields of Christians. In 589, in Christian Spain, the Third Council of Toledo ordered that children born of marriage between Jews and Christians be baptized by force. A policy of forced conversion of all Jews was initiated. Thousands fled, and thousands of others converted.

Anti-Semitism in the Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages a main justification of prejudice against Jews in Europe was religious. The Catholic Church taught that the Jewish people were collectively and permanently responsible for killing Jesus (see Deicide). The power of Christianity was very strong in the Middle Ages, and Jews were considered a direct affront to Christian beliefs.

Among socio-economic factors were restrictions by the authorities, local rulers and frequently church officials who closed many professions to the Jews, pushing them into marginal occupations considered socially inferior, such as local tax and rent collecting or moneylending, a necessary evil due to the increasing population and urbanization during the High Middle Ages. This provided support for claims that Jews are insolent, greedy, engaged in usury, and in itself contributed to a negative image. Natural tensions between creditors (typically Jews) and debtors (typically Christians) were added to social, political, religious and economic strains. Peasants who were forced to pay their taxes to Jews could personify them as the people taking their earnings while remaining loyal to the lords on whose behalf the Jews worked.

The demonizing of the Jews

From around the 12th century through the 19th there were Christians who believed that some (or all) Jews possessed magical powers; some believed that they had gained these magical powers from making a deal with the devil. See also Judensau, Judeophobia.

Blood libels

Main articles: blood libel, list of blood libels against Jews

On many occasions, Jews were accused of a blood libel, the supposed drinking of blood of Christian children in mockery of the Christian Eucharist. According to the authors of these blood libels, the 'procedure' for the alleged sacrifice was something like this: a child who had not yet reached puberty was kidnapped and taken to a hidden place. The child would be tortured by Jews, and a crowd would gather at the place of execution (in some accounts the synagogue itself) and engage in a mock tribunal to try the child. The child would be presented to the tribunal naked and tied and eventually be condemned to death. In the end, the child would be crowned with thorns and tied or nailed to a wooden cross. The cross would be raised, and the blood dripping from the child's wounds would be caught in bowls or glasses. Finally, the child would be killed with a thrust through the heart from a spear, sword, or dagger. Its dead body would be removed from the cross and concealed or disposed of, but in some instances rituals of black magic would be performed on it. This method, with some variations, can be found in all the alleged Christian descriptions of ritual murder by Jews. There is a tale by the Spanish writer Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer in which gruesome rituals are described in an attempt to make an defense of Catholicism.

The story of William of Norwich (d. 1144) is the first known case of ritual murder being alleged by a Christian monk while the story of Little Saint Hugh of Lincoln (d. 1255) said that after the boy was dead, his body was removed from the cross and laid on a table. His belly was cut open and his entrails removed for some occult purpose, such as a divination ritual. The story of Simon of Trent (d. 1475) emphasized how the boy was held over a large bowl so all his blood could be collected. Simon was regarded as a saint, and was canonized by Pope Sixtus V in 1588. The cult of Simon was disbanded in 1965 by Pope Paul VI, and the shrine erected to him was dismantled. He was removed from the calendar, and his future veneration was forbidden, though a handful of extremists still promote the narrative as a fact. In the 20th century, the Beilis Trial in Russia and the Kielce pogrom represented incidents of blood libel in Euriope, while more recently blood libel stories have appeared a number of times in the state-sponsored media of a number of Arab nations, in Arab television shows, and on websites.

Host desecration

Jews were falsely accused of torturing consecrated host wafers in a reenactment of the Crucifixion; this accusation was known as host desecration.

Disabilities and Restrictions

Jews were subject to a wide range of legal restrictions throughout the Middle Ages, some of which lasted until the end of the 19th century. Jews were excluded from many trades, the list of excluded occupations varying in different communities, and being determined largely by the political influence of various non-Jewish competing interests. Frequently all occupations were barred against Jews, except money-lending and pedling—even these at times being prohibited. The number of Jews or Jewish families permitted to reside in different places was limited; they were concentrated in ghettos, and were not allowed to own land; and they were subjected to discriminatory taxes on entering cities or districts other than their own, forced to swear special Jewish Oaths, and a variety of other measures, including restrictions on dress.

Clothing

Main article: yellow badge, Judenhut The Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 was the first to proclaim the requirement for Jews to wear something that distinguished them as Jews. It could be a colored piece of cloth in the shape of a star or circle or square, a hat (Judenhut), or a robe. This practice has its origins in the Islamic world where it was common for various religions to wear badges of faith. In many localities, members of the medieval society wore badges to distinguish their social status. Some badges (such as guild members) were prestigious, while others ostracized outcasts such as lepers, reformed heretics and prostitutes. Jews sought to evade the badges by paying what amounted to bribes in the form of temporary "exemptions" to kings, which were revoked and re-paid for whenever the king needed to raise funds.

The Crusades

The Crusades were a series of several military campaigns sanctioned by the Papacy that took place during the 11th through 13th centuries. They began as Catholic endeavours to capture Jerusalem from the Muslims but developed into territorial wars.

The mobs accompanying the first three Crusades attacked the Jewish communities in Germany, France, and England, and put many Jews to death. Entire communities, like those of Treves, Speyer, Worms, Mayence, and Cologne, were slain during the first Crusade. About 12,000 Jews are said to have perished in the Rhenish cities alone between May and July, 1096. Before the Crusades the Jews had practically a monopoly of trade in Eastern products, but the closer connection between Europe and the East brought about by the Crusades raised up a class of merchant traders among the Christians, and from this time onward restrictions on the sale of goods by Jews became frequent. Additionally, the religious zeal fomented by the Crusades burned as fiercely against the Jews as enemies of Christ as against the Muslims. Thus both economically and socially the Crusades were disastrous for European Jews. They prepared the way for the anti-Jewish legislation of Pope Innocent III, and formed the turning-point in the medieval history of the Jews.

The expulsions from England, France, Germany, and Spain

Only a few expulsions of the Jews are described in this section, for a more extended list see History of anti-Semitism, and also the History of the Jews in England, Germany, Spain, and France.

The practice of expelling the Jews accompanied by confiscation of their property, followed by temporary readmissions for ransom, was utilized to enrich the French crown during 12th-14th centuries. The most notable such expulsions were: from Paris by Philip Augustus in 1182, from entire France by Louis IX in 1254, by Charles IV in 1322, by Charles V in 1359, by Charles VI in 1394.

To finance his war to conquer Wales, Edward I of England taxed the Jewish moneylenders. When the Jews could no longer pay, they were accused of disloyalty. Already restricted to a limited number of occupations, the Jews saw Edward abolish their "privilege" to lend money, choke their movements and activities and were forced to wear a yellow patch. The heads of Jewish households were then arrested, over 300 of them taken to the Tower of London and executed, while others killed in their homes. The complete banishment of all Jews from the country in 1290 led to thousands killed and drowned while fleeing and the absence of Jews from England for three and a half centuries, until 1655, when Oliver Cromwell reversed the policy.

In 1492, Ferdinand_II_of_Aragon and Isabella_of_Castile issued General Edict on the Expulsion of the Jews from Spain (see also Spanish Inquisition) and many Sephardi Jews fled to the Ottoman Empire, some to the Land of Israel.

In 1744, Frederick II of Prussia limited Breslau to only ten so-called "protected" Jewish families and encouraged similar practice in other Prussian cities. In 1750 he issued Revidiertes General Privilegium und Reglement vor die Judenschaft: the "protected" Jews had an alternative to "either abstain from marriage or leave Berlin" (quoting Simon Dubnow). In the same year, Archduchess of Austria Maria Theresa ordered Jews out of Bohemia but soon reversed her position, on condition that Jews pay for readmission every ten years. This extortion was known as malke-geld (queen's money). In 1752 she introduced the law limiting each Jewish family to one son. In 1782, Joseph II abolished most of persecution practices in his Toleranzpatent, on the condition that Yiddish and Hebrew are eliminated from public records and judicial autonomy is annulled. Moses Mendelssohn wrote that "Such a tolerance... is even more dangerous play in tolerance than open persecution".

Anti-Judaism and the Reformation

Main article: Christianity and anti-Semitism

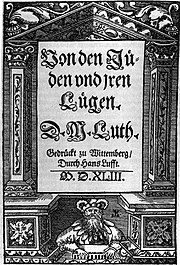

Martin Luther initially preached tolerance towards the Jewish people, convinced that the reason they had never converted to Christianity was that they were discriminated against, or had never heard the Gospel of Christ. However, after his overtures to Jews failed to convince Jewish people to adopt Christianity, he began preaching that the Jews were set in evil, anti-Christian ways, and needed to be expelled from the German body politic. Luther's harsh comments about the Jews are seen by many as a continuation of medieval Christian anti-Semitism, and a reflection of earlier anti-Semitic expulsions in the 14th century, when Jews from other countries like France and Spain were invited into Germany.

Anti-semitism in 19th and 20th century Catholicism

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Roman Catholic Church adhered to a distinction between "good anti-Semitism" and "bad anti-Semitism". The "bad" kind promoted hatred of Jews because of their descent. This was considered un-Christian because the Christian message was intended for all of humanity regardless of ethnicity; anyone could become a Christian. The "good" kind criticized alleged Jewish conspiracies to control newspapers, banks, and other institutions, to care only about accumulation of wealth, etc. Many Catholic bishops wrote articles criticizing Jews on such grounds, and, when accused of promoting hatred of Jews, would remind people that they condemned the "bad" kind of anti-Semitism. A detailed account is found in historian David Kertzer's book The Popes Against the Jews.

Modern passion plays

Passion plays, dramatic stagings representing the trial and death of Jesus, have historically been used in remembrance of Jesus' death during Lent in Christian communities which caused in the past hatred of local Jews in some of these communities. The plays depict a crowd of Jewish people condemning Jesus to crucifixion and a Jewish leader assuming collective guilt for the crowd for the murder of Jesus.

In 2003 and 2004 some have compared Mel Gibson's recent film The Passion of the Christ to these kinds of passion plays, but this characterization is hotly disputed; an analysis of that topic is in the article on The Passion of the Christ.

Racial anti-Semitism

Racial anti-Semitism replaced the hatred of Judaism with the hatred of Jews as a group. In the context of the Industrial Revolution, following the emancipation of the Jews, Jews rapidly urbanized and experienced a period of greater social mobility. With the decreasing role of religion in public life tempering religious anti-Semitism, a combination of growing nationalism, the rise of eugenics, and resentment at the socio-economic success of the Jews led to the newer, and more virulent, racist anti-Semitism.

The rise of racial anti-Semitism

Modern European anti-Semitism has its origin in 19th century pseudo-scientific theories that the Jewish people are a sub-group of Semitic peoples; Semitic people were thought by many Europeans to be entirely different from the Aryan, or Indo-European, populations, and that they can never be amalgamated with them. In this view, Jews are not opposed on account of their religion, but on account of their supposed hereditary or genetic racial characteristics: greed, a special aptitude for money-making, aversion to hard work, clannishness and obtrusiveness, lack of social tact, low cunning, and especially lack of patriotism.

Ironically, while enlightened European intellectual society of that period viewed prejudice against people on account of their religion to be declasse and a sign of ignorance, because of this supposed 'scientific' connection to genetics they felt fully justified in prejudice based on nationality or 'race'. In order to differentiate between the two practices, the term anti-Semitism was developed to refer to this 'acceptable' bias against Jews as a nationality, as distinct from the 'undesirable' prejudice against Judaism as a religion. Concurrently with this usage, some authors in Germany began to use the term 'Palestinians' when referring to Jews as a people, rather than as a religious group.

Equally ironic, and further proof of its pseudo-scientific nature, it is questionable whether Jews in general looked significantly different from the populations conducting "racial" anti-Semitism. This was especially true in places like Germany, France and Austria where the Jewish population tended to be more secular (or at least less Orthodox) than that of Eastern Europe, and did not wear clothing (such as a yarmulke) that would particularly distinguish their appearance from the non-Jewish population. Many anthropologists of the time such as Franz Boas tried to use complex physical measurements like the cephalic index and visual surveys of hair/eye color and skin tone of Jewish vs. non-Jewish European populations to prove that the notion of a separate "Jewish race" was a myth. The 19th and early 20th century view of race should be distinguished from the efforts of modern population genetics to trace the ancestry of various Jewish groups, see Y-chromosomal Aaron.

The advent of racial anti-Semitism was also linked to the growing sense of nationalism in many countries. The nationalist context viewed Jews as a seperate and often "alien" nation within the countires in which Jews resided, a prejudice exploited by the elites of many governments.

Elites and the use of Anti-semitism

Many analysts of modern anti-Semitism have pointed out that its essence is scapegoating: features of modernity felt by some group to be undesirable (e.g. materialism, the power of money, economic fluctuations, war, secularism, socialism, Communism, movements for racial equality, social welfare policies, etc., etc.) are believed to be caused by the machinations of a conspiratorial people whose full loyalties are not to the national group. Traditionalists anguished at the supposedly decadent or defective nature of the modern world have sometimes been inclined to embrace such views. Indeed, it is a matter of historical record that many of the conservative members of the WASP establishment of the United States as well as other comparable Western elites (e.g. the British Foreign Office) have harbored such attitudes, and in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution, some xenophobic anti-Semites have imagined world Communism to be a Jewish conspiracy (Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups , p. 590).

The modern form of anti-Semitism is identified in the 1911 edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica as a conspiracy theory serving the self-understanding of the European aristocracy, whose social power waned with the rise of bourgeois society. The Jews of Europe, then recently emancipated, were relatively literate, entrepreneurial and unentangled in aristocratic patronage systems, and were therefore disproportionately represented in the ascendant bourgeois class. As the aristocracy (and its hangers-on) lost out to this new center of power in society, they found their scapegoat - exemplified in the work of Arthur de Gobineau. That the Jews were singled out to embody the 'problem' was, by this theory, no more than a symptom of the nobility's own prejudices concerning the importance of breeding (on which its own legitimacy was founded).

Dreyfus Affair

The Dreyfus affair was a political scandal which divided France for many years during the late 19th century. It centered on the 1894 treason conviction of Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish officer in the French army. Dreyfus was, in fact, innocent: the conviction rested on false documents, and when high-ranking officers realised this they attempted to cover up the mistakes. The writer Émile Zola exposed the affair to the general public in the literary newspaper L'Aurore (The Dawn) in a famous open letter to the Président de la République Félix Faure, titled J'accuse ! (I Accuse!) on January 13, 1898.

The Dreyfus Affair split France between the Dreyfusards (those supporting Alfred Dreyfus) and the Antidreyfusards (those against him). The quarrel was especially violent since it involved many issues then highly controversial in a heated political climate.

Dreyfus was pardoned in 1899, readmitted into the army, and made a knight in the Legion of Honour. An Austrian Jewish journalist named Theodor Herzl was assigned to report on the trial and its aftermath. The injustice of the trial and the anti-Semitic passions it aroused in France and elsewhere turned him into a determined Zionist; ultimately turning the movement into an international one. Also see Alfred Dreyfus and Dreyfus affair.

Eastern European pogroms

Pogroms were a form of race riots in Russia and Eastern Europe, aimed specifically at Jews and often government sponsored. Pogroms became endemic during a large-scale wave of anti-Jewish riots that swept southern Russia in 1881, after Jews were wrongly blamed for the assassination of Tsar Alexander II. In the 1881 outbreak, thousands of Jewish homes were destroyed, many families reduced to extremes of poverty; women sexually assaulted, and large numbers of men, women, and children killed or injured in 166 Russian towns. The new czar, Alexander III, blamed the Jews for the riots and issued a series of harsh restrictions on Jews. Large numbers of pogroms continued until 1884, with at least tacit inactivity by the authorities.

An even bloodier wave of pogroms broke out in 1903-1906, leaving an estimated 2,000 Jews dead, and many more wounded. Pogroms also occured in Poland, Argentina, and throughout the Arab world throughout the mid-1900s.

Anti-Jewish Legislation

Official anti-semitic legislation was enacted in various countries, especially in Imperial Russia in the 19th century and in Nazi Germany and its Central European allies in the 1930s. These laws were passed against Jews as a group, regardless of their religious affiliation - in some cases, such as Nazi Germany, having a Jewish grandparent was enough to qualify someone as Jewish.

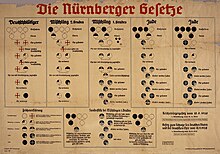

In Germany, for example, the Nuremberg Laws of 1935 prevented marriage between any Jew and non-Jew, and made it that all Jews, even quarter- and half-Jews, were no longer citizens of their own country (their official title became "subject of the state"). This meant that they had no basic citizens' rights, e.g., to vote. In 1936, Jews were banned from all professional jobs, effectively preventing them having any influence in education, politics, higher education and industry. On 15 November of 1938, Jewish children were banned from going to normal schools. By April 1939, nearly all Jewish companies had either collapsed under financial pressure and declining profits, or had been persuaded to sell out to the Nazi-German government. This further reduced their rights as human beings; they were in many ways officially separated from the German populace. Similar laws existed in Hungary, Romania, and Austria.

Even when anti-Semitism was not official state policy, governments in the early to middle parts of the 20th century often adopted more subtle measures aimed at Jews. For example, the Immigration Act of 1924 in the United States used quotas to reduce Jewish (as well as Italian) immigration, and the Evian Conference of 1938 delegates from thirty-two countries neither condemned Hitler's treatment of the Jews nor allowed more Jewish refugees to flee to the West.

The Holocaust and Holocaust Revisionism

Racial anti-Semitism reached its most horrific manifestation in the Holocaust during World War II, in which about 6 million European Jews, 1.5 million of them children, were systematically murdered.

Holocaust deniers and revisionists often claim that "the Jews" or "Zionist conspiracy" are responsible for the exaggeration or wholesale fabrication of the events of the Holocaust. Critics of such revisionism point to an overwhelming amount of physical and historical evidence that supports the mainstream historical view of the Holocaust. Almost all academics agree that there is no evidence for any such conspiracy.

Anti-Semitic conspiracy theories

With the rise of views of the Jews as a malevolent "race" generated anti-Semitic conspiracy theories that the Jews, as a group, were plotting to control or otherwise influence the world. From the early infamous Russian literary hoax, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, published by the Tzar's secret police, a key element of anti-Semitic thought has been that Jews influence or control the world.

In a recent incarnation, extremist groups, such as Neo-Nazi parties and Islamist groups, claim that the aim of Zionism is global domination; they call this the Zionist conspiracy and use it to support anti-Semitism. This position is associated with fascism and Nazism, though increasingly, it is becoming a tendency within parts of the left as well.

Anti-Semitism and Islam

Anti-Semitism within Islam is discussed in the article on Islam and anti-Semitism. Anti-Semitism in the Arab World is discussed in the article on Arabs and anti-Semitism.

The Qur'an, Islam's holy book, criticizes the Jews for corrupting the Hebrew Bible. Muslims refer to Jews and Christians as a "People of the book"; Islamic law demands that when under Muslim rule they should be tolerated as dhimmis - from the Arab term ahl adh-dhimma. The writer Bat Ye'or introduced the modern word Dhimmitude as a generic indication of this Islamic attitude. Dhimmis were granted protection of life (even against other muslim states), wealth and honor, the right to residence, worship, and work or trade, and were exempted from military service, the zakah tax, and Muslim religious duties and personal law. They were obligated to pay other taxes (jizyah and land tax), and subject to various other restrictions regarding blaspheming Islam, the Qur'an or Muhammed, proselytizing, and at times a number of other restrictions on dress, riding horses or camels, carrying arms, holding public office, building places of worship higher than mosques, mourning loudly, wearing shoes outside the mellah, etc.

Anti-Semitism in the Muslim world increased in the twentieth century, as anti-Semitic motives and blood libels were imported from Europe. While anti-Semitism has certainly been heightened by the Arab-Israeli conflict, there were an increasing number of pogroms against Jews even before the foundation of Israel, including massive attacks on the Jews in Iraq and Libya in the 1940s (see Farhud), and Nazi-inspired pogroms in Algeria in the 1930s.

Anti-semitism and specific countries

United States

Jews were often condemned by populist politicians alternately for their left-wing politics, or their perceived wealth, at the turn of the century. Anti-semitism grew in the years leading up to America's entry into World War II, Father Charles Coughlin, an anti-Semitic radio preacher, as well as many other prominent public figures, condemned "the Jews," and Henry Ford reprinted The Protocols of the Elders of Zion in his newspaper.

Unofficial antisemitism was also widespread in the first half of the century. For example, to limit the growing number of Jewish students between 1919-1950s a number of private liberal arts universities and medical and dental schools employed Numerus clausus. These included Harvard University, Columbia University, Cornell University, and Boston University. In 1925 Yale University, which already had such admissions preferences as "character", "solidity", and "physical characteristics" added a program of legacy preference admission spots for children of Yale alumni, in an explicit attempt to put the brakes on the rising percentage of Jews in the student body. This was soon copied by other Ivy League and other schools, and admissions of Jews were kept down to 10% through the 1950s. Such policies were eventually discarded during the early 1960s.

American anti-Semitism underwent a modest revival in the late 20th century; some Black Muslims claimed that Jews were responsible for the exploitation of black labor, bringing alcohol and drugs into their communities, and unfair domination of the economy. These claims are generally considered spurious by impartial observers.

Europe

According to 2005 survey results by ADL, anti-Semitic attitudes remain common in Europe. Over 30% of those surveyed indicated that Jews have too much power in business, with responses ranging from lows of 11% in Denmark and 14% in England to highs of 66% in Hungary, and over 40% in Poland and Spain. The results of religious anti-Semitism also linger, with over 20% of European respondents agreeing that Jews were responsible for the death of Jesus, with Poland having the highest number of those agreeing, at 39%.

The Vienna-based European Union Monitoring Center (EUMC), for 2002 and 2003, identified France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Belgium, and The Netherlands as EU member countries with notable increases in incidents. As these nations keep reliable and comprehensive statistics on anti-Semitic acts, and are engaged in combating anti-Semitism, their data was readily available to the EUMC. Governments and leading public figures condemned the violence, passed new legislation, and mounted positive law enforcement and educational efforts.

In Western Europe, traditional far-right groups still account for a significant proportion of the attacks against Jews and Jewish properties; disadvantaged and disaffected Muslim youths increasingly were responsible for most of the other incidents. In Eastern Europe, with a much smaller Muslim population, skinheads and others members of the radical political fringe were responsible for most anti-Semitic incidents. Anti-Semitism remained a serious problem in Russia and Belarus, and elsewhere in the former Soviet Union, with most incidents carried out by ultra-nationalist and other far-right elements. The stereotype of Jews as manipulators of the global economy continues to provide fertile ground for anti-Semitic aggression.

France

Anti-semitism was particularly virulant in Vichy France during WWII (1939 - 1945). The French populace openly collaborated with the Nazi occupiers to identify Jews for deportation and transportation to the death camps. Anti-semitism remains strong in France with frequent vandalism and desecration of Jewish cemeteries and synagogues. According to the National Advisory Committee on human rights, anti-semitic acts account for a majority (72% of all in 2003) of racist acts in France.

Poland

see History of the Jews in Poland

In 1264, King Boleslaus V of Poland legislated a charter for Jewish residence and protection, hoping that Jewish settlement would contribute to the development of the Polish economy. This charter, which encouraged money-lending, was a slight variation of the 1244 charter granted by the King of Austria to the Jews. By the sixteenth century, Poland had become the center of European Jewry and the most tolerant of all European countries regarding the matters of faith, althought there were still occasionally violent anti-semitic incidents.

At the onset of the seventeenth century, however, the tolerance began to give way to increased anti-Semitism. Elected to the Polish throne King Sigismund III of the Swedish House of Vasa, a strong supporter of the counter-reformation, began to undermine the principles of the Warsaw Confederation and the religious tolerance in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, revoking and limiting priviliges of all non-Catholic faiths. In 1628 he banned publication of Hebrew books, including the Talmud . Acclaimed twentieth century historian Simon Dubnow, in his magnum-opus History of the Jews in Poland and Russia, detailed:

- "At the end of the 16th century and thereafter, not one year passed without a blood libel trial against Jews in Poland, trials which always ended with the execution of Jewish victims in a heinous manner..." (ibid., volume 6, chapter 4).

In the 1650s the Swedish invasion of the Commonwealth (The Deluge) and the Chmielnicki Uprising of the Cossacks resulted in vast depopulation of the Commonwealth, as over 30% of the ~10 million population has perished or emigrated. In the related 1648-55 pogroms led by the Ukrainian Haidamaks uprising against Polish nobility (szlachta), during which approximately 100,000 Jews were slaughtered, Polish and Ruthenian peasants often participated in killing Jews (The Jews in Poland, Ken Spiro, 2001). The besieged szlachta, who were also decimated in the territories where the uprising happened, typically abandoned the loyal peasantry, townsfolk, and the Jews renting their land, in violation of "rental" contracts.

In the aftermath of the Deluge and Chmielnicki Uprising, many Jews fled to the less turbulent Netherlands, which had granted the Jews a protective charter in 1619. From then until the Nazi deportations in 1942, the Netherlands remained a remarkably tolerant haven for Jews in Europe, excedeeing the tolerance extant in all other European countries at the time, and becoming one of the few Jewish havens until nineteenth century social and political reforms throughout much of Europe. Many Jews also fled to England, open to Jews since the mid-seventeenth century, in which Jews were fundamentally ignored and not typically persecuted. Historian Berel Wein notes:

- "In a reversal of roles that is common in Jewish history, the victorious Poles now vented their wrath upon the hapless Jews of the area, accusing them of collaborating with the Cossack invader!... The Jews, reeling from almost five years of constant hell, abandoned their Polish communities and institutions..." (Triumph of Survival, 1990).

Throughout the sixteenth to eighteenth century, many of the szlachta mistreated peasantry, townsfolk and Jews. Threat of mob violence was a specter over the Jewish communities in Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth at the time. On one occasion in 1696, a mob threatened to massacre the Jewish community of Posin, Vitebsk. The mob accused the Jews of murdering a Pole. At the last moment, a peasant woman emerged with the victim's clothes and confessed to the murder. One notable example of actualized riots against Polish Jews is the rioting of 1716, during which many Jews lost their lives. Later, in 1723, the Bishop of Gdańsk instigated the massacre of hundreds of Jews.

The legendary Walentyn Potocki, a Polish nobleman who converted to Judaism, is said to have been burned by auto da fe on May 24, 1749. In 1757, at the instigation of Jacob Frank and his followers, the Bishop of Kamianets-Podilskyi forced the Jewish rabbis to participate in religious dispute with the quasi-Christian Frankists. Among the other charges, the Frankists claimed that the Talmud was full of heresy against Catholicism. The Catholic judges determined that the Frankists had won the debate, whereupon the Bishop levied heavy fines against the Jewish community and confiscated and burned all Jewish Talmuds. Polish anti-Semitism during the seventeenth and eighteenth century was summed up by Issac de Pinto as follows: "Polish Jews... who are deprived of all the privilages of society... who are despised and reviled on all sides, who are often persecuted, always insulted.... That contempt which is heaped on them chokes up all the seeds of virtue and honour...." (Issac de Pinto, philosopher and economist, in a 1762 letter to Voltaire).

On the other hand, it should be noted that despite the mentioned incidents, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was a relative haven for Jews when compared to the period of the partitions of Poland and the PLC's destruction in 1795 (see Imperial Russia and the Soviet Union, below).

Anti-Jewish sentiments continued to be present in Poland, even after the country regained its independence. One notable manifestation of these attitudes includes numerus clausus rules imposed, with government support, by almost all Polish universities in the 1930's. William W. Hagen in his Before the "Final Solution": Toward a Comparative Analysis of Political Anti-Semitism in Interwar Germany and Poland article in Journal of Modern History (July, 1996): 1-31, details:

- "In Poland, the semidictatorial government of Pilsudski and his successors, pressured by an increasingly vocal opposition on the radical and fascist right, implemented many anti-Semitic policies tending in a similar direction, while still others were on the official and semiofficial agenda when war descended in 1939.... In the 1930s the realm of official and semiofficial discrimination expanded to encompass limits on Jewish export firms... and, increasingly, on university admission itself. In 1921-22 some 25 percent of Polish university students were Jewish, but in 1938-39 their proportion had fallen to 8 percent."

While there are many examples of Polish support and help for the Jews during World War II and the Holocaust, there are also numerous examples of anti-semitic incidents. The Polish Institute for National Memory identified twenty-four pogroms against Jews during World War II, the largest occuring at the village of Jedwabne in 1941.

After the end of World War II the remaining anti-Jewish sentiments were skillfully used at certain moments by communist party or individual politicians in order to achieve their assumed political goals, which pinnacled in March 1968 events. These sentiments started to diminish only with the collapse of the communist rule in Poland in 1989, which has resulted in a re-examination of events between Jewish and Christian Poles, with a number of incidents, like the masscre at Jedwabne, being discussed openly for the first time. Violent anti-semitism in Poland in 21st century is marginal compared to elsewhere, but there are very few Jews remaining in Poland. Still, according to recent (June 7, 2005) results of research by B'nai Briths Anti-Defamation League, Poland remains among the European countries (with others being Italy, Spain and Germany) with the largest percentages of people holding anti-Semitic views.

Poland is actively trying to address concerns about anti-semitism. In 2004, the Polish government approved a National Action Program against racism, including anti-semitism. Additionally the Polish Catholic Church has widely distributed materials promoting the need for respect and cooperation with Judaism.

Germany

See main articles: History of the Jews in Germany, Holocaust

The Jews in Germany were subject to a many persecutions, as well as brief times of tolerance. By the early 20th century, the Jews of Germany were the most integrated in Europe, but the situation changed quickly with the rise of the Nazis and their explicity anti-Semitic program, hate speech referring to Jewish citizens as "dirty Jews" became common in anti-semitic pamplets and newspapers, such as Völkischer Beobachter and Der Stürmer.

Nazi cartoons depicting "dirty Jews" frequently portrayed a dirty, physically unattractive and badly dressed "talmudic" Jew in traditional religious garments similar to those worn by Hassidic Jews. Articles attacking Jewish Germans, while concentrating on commercial and political activities of prominent Jewish individuals, also frequently attacked them based on religious dogmas. Accusations of responsibility of "killing our savior Jesus Christ" and refusal by Jews to "accept the savior" and convert to Christianity that fueled the hatred in the Middle Ages were also repeated by Nazi propagandists.

Hatred against Jews manifested itself in such measures as the Nuremberg Laws which banned "race-mixing" and in the Kristallnacht riots which targeted Jewish homes, businesses and places of worship.

Russia and the Soviet Union

Main articles: History of the Jews in Russia and Soviet Union, Pogrom

The Pale of Settlement was the Western region of Imperial Russia to which Jews were restricted by the Tsarist Ukase of 1792. It consisted of the territories of former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, annexed with the existing numerous Jewish population, and the Crimea (which was later cut out from the Pale).

During 1881-1884, 1903-1906 and 1914-1921, waves of anti-Semitic pogroms swept Russian Jewish communities. At least some pogroms are believed to have been organized or supported by the Russian okhranka; although there is no hard evidence for this, the Russian police and army generally displayed indifference to the pogroms (e.g. during the three-day First Kishinev pogrom of 1903), as well as to anti-Jewish articles in newspapers which often instigated the pogroms.

During this period the May Laws policy was also put into effect, banning Jews from rural areas and towns, and placing strict quotas on the number of Jews allowed into higher education and many professions. The combination of the repressive legislature and pogroms propelled mass Jewish emigration, and by 1920 more than two million Russian Jews had emigrated, most to the United States while some made aliya to the Land of Israel.

One of the most infamous anti-Semitic tractates was the Russian okhranka literary hoax, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, created in order to blame the Jews for Russia's problems during the period of revolutionary activity.

Even though many Old Bolsheviks were ethnically Jewish, they sought to uproot Judaism and Zionism and established the Yevsektsiya to achieve this goal. By the end of the 1940s the Communist leadership of the former USSR had liquidated almost all Jewish organizations, including Yevsektsiya.

The anti-Semitic campaign of 1948-1953 against so-called "rootless cosmopolitans," destruction of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, the fabrication of the "Doctors' plot," the rise of "Zionology" and subsequent activities of official organizations such as the Anti-Zionist committee of the Soviet public were officially carried out under the banner of "anti-Zionism," but the use of this term could not obscure the anti-Semitic content of these campaigns, and by the mid-1950s the state persecution of Soviet Jews emerged as a major human rights issue in the West and domestically. See also: Jackson-Vanik amendment, Refusenik, Pamyat.

Today, anti-Semitic pronouncements, speeches and articles are common in Russia, and there are a large number of anti-Semitic neo-Nazi groups in the republics of the former Soviet Union, leading Pravda to declare in 2002 that "Anti-semitism is booming in Russia". Over the past few years there have also been bombs attached to anti-semitic signs, apparently aimed at Jews, and other violent incidents, including stabbings, have been recorded.

Though the government of Vladimir Putin takes an official stand against anti-semitism, some political parties and groups are explicitly anti-semitic, in spite of a Russian law (Art. 282) against fomenting racial, ethnic or religious hatred. In 2005, a group of 15 Duma members demanded that Judaism and Jewish organizations be banned from Russia. In June, 500 prominent Russians, including some 20 members of the nationalist Rodina party, demanded that the state prosecutor investigate ancient Jewish texts as "anti-Russian" and ban Judaism — the investigation was actually launched, but halted among international outcry.

Anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism

Anti-Zionism is a term that has been used to describe several very different political and religious points of view (both historically and in current debates) all expressing some form of opposition to Zionism. A large variety of commentators - politicians, journalists, academics and others - believe that criticisms of Israel and Zionism are often disproportionate in degree and unique in kind, and attribute this to anti-Semitism. In turn, critics of this view believe that associating anti-Zionism with anti-Semitism is intended to stifle debate, deflect attention from valid criticism, and taint anyone opposed to Israeli actions and policies. This subject is discussed in the main article on Anti-Zionism.

New anti-Semitism

Main article: New anti-SemitismIn recent years some scholars of history, psychology, religion and representatives of Jewish groups, have noted what they describe as the new anti-Semitism, which uses the language of anti-Zionism and criticism against Israel to attack the Jews more broadly.

The European Commission on Racism and Intolerance formally defined some of the ways in which anti-Zionism may cross the line to anti-Semitism: "Examples of the ways in which anti-Semitism manifests itself with regard to the State of Israel taking into account the overall context could include: Denying the Jewish people right to self-determination, e.g. by claiming that the existence of a state of Israel is a racist endeavor; applying double standards by requiring of it a behavior not expected or demanded of any other democratic nation; using the symbols and images associated with classic anti-Semitism (e.g. claims of Jews killing Jesus or blood libel) to characterize Israel or Israelis; drawing comparisons of contemporary Israeli policy to that of the Nazis; and holding Jews collectively responsible for actions of the State of Israel."

Anti-Semitism in the 21st century

According to the 2005 US State Deparment Report on Global Anti-Semitism, anti-Semitism in Europe increased significantly in recent years. Beginning in 2000, verbal attacks directed against Jews increased while incidents of vandalism (e.g. graffiti, fire bombings of Jewish schools, desecration of synagogues and cemeteries) surged. Physical assaults including beatings, stabbings and other violence against Jews in Europe increased markedly, in a number of cases resulting in serious injury and even death.

Similarly, in the Middle East, anti-Zionist propaganda frequently adopts the terminology and symbols of the Holocaust to demonize Israel and its leaders. This rhetoric often crosses the line separating the legitimate criticism of Israel and its policies to become anti-Semitic vilification posing as legitimate political commentary. At the same time, Holocaust denial and Holocaust minimization efforts find increasingly overt acceptance as sanctioned historical discourse in a number of Middle Eastern countries.

The problem of anti-Semitism is not only significant in Europe and in the Middle East, but there are also worrying expressions of it elsewhere. For example, in Pakistan, a country without a Jewish community, anti-Semitic sentiment fanned by anti-Semitic articles in the press is widespread. This reflects the more recent phenomenon of anti-Semitism appearing in countries where historically or currently there are few or even no Jews.

In the Americas, in addition to manifestations of anti-Semitism in the United States, Canada experienced a significant increase in attacks against Jews and Jewish property. There were notable anti-Semitic incidents in Argentina and isolated incidents in a number of other Latin American countries.

See also

- Jews and Judaism

- Other articles on anti-Semitism:

- Related topics:

- Topics related to religious anti-Semitism:

- Anti-semitic laws, policies, and government actions

- Pogroms in Russia

- May Laws in Russia

- March 1968 events in Poland

- Dreyfus affair in France

- Farhud in Iraq

- Nazi Germany and the Holocaust

- Anti-semitic websites

- Organizations working against anti-Semitism

References

- The Destruction of the European Jews Raul Hilberg. Holmes & Meier, 1985. 3 volumes

- Hollywood and anti-semitism : a cultural history up to World War II, Steven Alan Carr, Cambridge University Press 2001

- Michael Selzer (ed), "Kike!" : A documentary history of anti-semitism in America, New York 1972

- Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory Deborah Lipstadt, 1994, Penguin.

- Antisemitism in the New Testament, Lillian C. Freudmann, University Press of America, 1994.

- Islamic Anti-Semitism as a Political Instrument, Yossef Bodansky, Freeman Center For Strategic Studies, 1999

- Warrant for Genocide Norman Cohn, 1967 (Eyre & Spottiswoode), 1996 (Serif)

- US State Department Report on Global Anti-Semitism, 2005.

External links

- Why the Jews? A study of the causes of anti-Semitism

- Coordination Forum for Countering Antisemitism (with up to date calendar of anti-semitism today)

- Annotated bibliography of anti-Semitism hosted by the Hebrew University of Jerusalem's Center for the Study of Antisemitism (SICSA)

- Anti-Semitism and responses

- The Stephen Roth Institute for the Study of Contemporary anti-Semitism and Racism hosted by the Tel Aviv University - (includes an annual report)

- Jews, the End of the Vertical Alliance, and Contemporary Antisemitism

- An Israeli point of view on antisemitism, by Steve Plaut

- The Anti-Semitic Disease - an analysis of Anti-Semitism by Paul Johnson in Commentary Magazine

- Council of Europe, ECRI Country-by-Country Reports

- State University of New York at Buffalo, The Jedwabne Tragedy

- Jews in Poland today

- Report on Global Anti-Semitism of United States Department of State

- Anti-Defamation League's report on International Anti-Semitism

- Example of anti-Semitism

- church of the sons of yhvh

- Monsignor Jouin, "The Holy See and the Jews" in Révue International des Societés, (Ligue Franc-Catholique), Paris, 1918]: an anti-Semitic pamphlet commended in a letter of June 20, 1919, signed by Cardinal Gasparri, Papal Secretary of State, and also printed in the Révue; the pamphlet contains a useful collection of Papal bulls concerning the Jews, with incipits and dates.