| Revision as of 00:00, 5 May 2009 view sourceJaakobou (talk | contribs)15,880 edits Undid revision 287860550 by 79.183.104.112 (talk) - it's all in the articles with relevant citations.← Previous edit | Revision as of 00:10, 5 May 2009 view source Jaakobou (talk | contribs)15,880 edits several issues with the article, but currently, the main issue is the use of propaganda sources for so-called neutral historical accounts.Next edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{NPOV|Finkelstein}} | |||

| ], 1932.]] | ], 1932.]] | ||

| The '''Exodus from Lydda''', also known as the '''Lydda Death March''', took place during ] in the ]. After Israeli forces took control of the cities of ] and ], between 50,000 and 70,000 ] were expelled at gunpoint, beginning on 12 July 1948, following orders from ].<ref>Morris, 2003, pp. 176-177; also see Tolan, Sandy. , ''Al Jazeera'', 21 July 2008, accessed April 29, 2009; Holmes et al., 2001, p. 64; Prior, 1999, p. 205; Peretz Kidron: ''Truth Whereby Nations Live''. In Said and Hitchens, 1998, pp. 90-93.</ref> | The '''Exodus from Lydda''', also known as the '''Lydda Death March''', took place during ] in the ]. After Israeli forces took control of the cities of ] and ], between 50,000 and 70,000 ] were expelled at gunpoint, beginning on 12 July 1948, following orders from ].<ref>Morris, 2003, pp. 176-177; also see Tolan, Sandy. , ''Al Jazeera'', 21 July 2008, accessed April 29, 2009; Holmes et al., 2001, p. 64; Prior, 1999, p. 205; Peretz Kidron: ''Truth Whereby Nations Live''. In Said and Hitchens, 1998, pp. 90-93.</ref> | ||

Revision as of 00:10, 5 May 2009

| The neutrality of this article is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The Exodus from Lydda, also known as the Lydda Death March, took place during Operation Danny in the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. After Israeli forces took control of the cities of Lydda and Ramla, between 50,000 and 70,000 Palestinians were expelled at gunpoint, beginning on 12 July 1948, following orders from Yitzhak Rabin.

Ramla residents were bussed or trucked to Al-Qubab, then made their way on foot to the Arab Legion lines in Latrun. The people of Lydda had to walk around Template:Km to mi to Beit Nabala, then Template:Km to mi to Barfiliya, in temperatures of 30-35 °C (86-95 °F), carrying their young children and whatever possessions they were able to take with them. The final destination for most of them was a refugee camp in Ramallah some Template:Km to mi from the two cities. In addition to losing their homes, many were also stripped of their portable possessions by Israeli soldiers.

The number of refugees who died during what became known as the "death march" out of Lydda is unknown. Figures range from "a handful, and perhaps dozens" to 355, primarily from exhaustion and dehydration, though eyewitnesses also reported that refugees were killed for refusing to hand over their valuables.

According to a report written at the time by the Palmach, the expulsion of the residents was seen as averting a long-term Arab threat to Tel Aviv, with the additional military benefit to the Israelis of clogging the roads along which the Arab Legion might have advanced. The deportations accounted for one-tenth of the overall Arab exodus from Palestine, which has come to be known as al-Nakba.

Background

See also: 1947–1948 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine, 1948 Arab-Israeli War, and 1948 Palestinian exodusAfter World War I and until the outbreak of the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, Lydda and Al-Ramla were towns in the District of Ramla in British Mandate Palestine.

In the immediate aftermath of the 1947 United Nations' approval of the Partition plan, expression of discontent amongst the Arab community of the Mandate grew leading to violent breakouts. Murders, reprisals, and counter-reprisals came one after the other, killing dozens of victims on both sides in the process. The Jerusalem Grand Mufti, Mohammad Amin al-Husayni arranged a Palestinian blockade on the 100,000 Jewish residents of Jerusalem and hundreds of the Jewish Haganah members who tried to bring supplies to the city were killed. The Jewish population was under strict orders to hold their dominions at all costs, but the situation of insecurity across the country affected the Arab population more visibly where up to 100,000 Palestinians, chiefly those from the upper classes, left the country to seek refuge abroad or in Samaria.

The situation caused the U.S. to retract their support for the Partition plan, thus encouraging the Arab League to believe that the Palestinians, now reinforced by the Arab Liberation Army, could put an end to the partition plan which was widely rejected in the Arab World. On 14 May 1948, David Ben-Gurion declared the independence of the state of Israel, an event followed by several Arab states' armies attacking the Jewish state the following day.

Operation Danny, in which the Exodus from Lydda was ordered, was an Israeli operation carried out between the first and second truce of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. The objective was to relieve the Jewish population and forces in Jerusalem and to capture Arab territory around Tel Aviv from which attacks on the city were launched. The road between the two cities had come under control of Arab militia and Arab Legion forces after Operation Nachshon had opened it.

The 1947 Partition plan which proposed dividing the British Mandate of Palestine into two states (one Jewish and one Arab) would have both Lydda and Al-Ramla be part of the proposed Arab state.

Events

Further information: Operation DannyCapture of Lydda and Ramla

Benny Morris writes that Israeli military strikes began against Lydda and Ramla in May 1948 because they were regarded as potential bases for attacks against Tel Aviv, ten miles away, as well as against Israeli settlements along the road to Jerusalem.

From the start, the bombing and shelling of the cities as part of Operation Danny, which began on the night of July 9-10, was intended to induce civilian panic and flight among residents, including some 15,000 refugees who had arrived in Lydda and Ramla from elsewhere in Palestine, toward Arab lines. This measure was seen as a means to triggering military collapse. On July 11, the Israeli air force dropped leaflets onto the towns telling the residents to surrender or die, and the 89th (armored) Battalion, led by Moshe Dayan, carried out a raid on Lydda, and on the Lydda-Ramla road. After the raids, 300-400 soldiers from the Yiftah Brigade's Third Battalion entered Lydda on the evening of July 11. The residents of Ramla formally surrendered on July 12, and the Kiryati Brigade's 42nd Battalion mortared the city, then entered it, imposing a curfew on the residents.

Events and massacre of July 12, 1948

No formal surrender was announced in Lydda, though groups of old and young gathered in the streets waving white flags in sign of submission. One Arab Legion platoon and some irregulars continued to resist, based in the town's police station, and on July 12, two Arab Legion armoured cars from the Jordanian 1st Brigade entered the city, on reconaissance or seeking a missing officer, and retreated after a firefight. Shots exchanged during the brief skirmish with Israeli troops led some townspeople to believe the Legion had arrived to defend them, and sniper fire broke out against the Israelis. Israeli soldiers were unnerved by this: there were only 300-400 of them to quell a city of 40,000-50,000. In response, Moshe Kalman, the Third Battalion's commander, ordered troops to shoot at "any clear target," and at anyone "seen on the streets."

Hearing the gunfire, many residents ran out of their homes, fearing that a massacre was in progress, and were shot. Israeli soldiers threw grenades into houses that they suspected snipers were hiding in. Between 11:30 and 13:30 hours that day, around 250 residents were killed and an unknown number wounded, according to the Palmach. Palestinian historian Aref al-Aref places the Palestinian death toll at 400, while Nimr al-Khatib writes that the townspeople staged an uprising during which 1,700 were killed, though Benny Morris regards the latter as an exaggeration. The Israelis suffered 2-4 dead and 14 wounded.

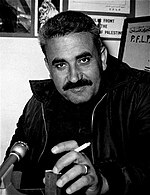

There appears to be no disagreement among historians and eyewitnesses that the killing appeared indiscriminate. George Habash, who later founded the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, was in Lydda during the seige. A second-year medical student, he went to its clinic to help the injured. On his way through the town, he said he saw: "terrible sights: Dozens of bodies lay in pools of blood, old and young had been shot. Among the dead, I recognized one elderly man, a neighbor who had a small falafel shop and who had never carried a gun." Habash was subsequently expelled with the rest of the refugees.

One of the Brigade commanders, Mula Cohen, later wrote of the attacks on the city and the expulsions that "the cruelty of the war here reached its zenith," and that the conquest of a city regarded as a key enemy base "gave rise to vengeful urges" among Israeli troops. Morris writes that the shootings and subsequent looting of the town by Israeli troops undermined the morale of the Third Battalion to the point where they had to be withdrawn during the night of July 13-14, and sent for a day to Ben Shemen for kinus heshbon nefesh, a conference to encourage soul-searching. They were replaced by a Kiryati unit.

Expulsion orders

Further information: Plan Dalet

Morris writes that the resistance of the snipers in Lydda sealed the townpeople's fate. A meeting was held at Operation Danny headquarters, attended by David Ben-Gurion, Israel's first prime minister; Generals Yigael Yadin and Zvi Ayalon of the IDF; Yisrael Galilee, formerly of the Haganah National Staff; and Yigal Allon and his deputy Yitzhak Rabin, who led Operation Danny. Rabin was commander at the time of the Harel Brigade, which had been assigned to eliminate Arab Legion bases along the road from Jerusalem to Tel Aviv.

At one point, Morris writes, Ben-Gurion, Allon, and Rabin left the room. Allon asked what was to be done with the Arab population. Ben-Gurion is reported by Michael Bar-Zohar, citing Yitzhak Rabin as his source, to have waved his hand and said, "garesh otam" — "expel them." Arieh Itzchaki, former director of the IDF General Staff/History Branch archive, writes that Ben-Gurion made only the hand gesture, but did not actually say "expel them." It was Allon and Rabin who made the decision to go ahead with the expulsions, according to Itzchaki.

In his memoirs, Rabin writes that Allon asked Ben-Gurion what was to be done with the population of Lydda, and that Ben-Gurion "waved his hand in gesture which said: Drive them out! Alon and I held a consultation. I agreed it was essential to drive the inhabitants out." Rabin's reference in his memoirs to the expulsions was removed by an Israeli censorship board composed of five Cabinet members, but Peretz Kidron, an Israeli journalist who translated Rabin's memoirs from Hebrew into English, passed the censored excerpt to The New York Times, which published it on October 23, 1979.

During the brief battle between the snipers in Lydda and the Israeli troops, Danny HQ issued the expulsion order to Yiftah Brigade HQ and 8th Brigade HQ, at 13:30 hours on 12 July, and to Kiryati Brigade at around the same time:

1. The inhabitants of Lydda must be expelled quickly without attention to age. They should be directed towards Beit Nabala. Yiftah must determined the method and inform Dani HQ and 8th Brigade HQ.

2. Implement immediately.

Michael Prior writes that a similar expulsion order was issued for the city of Ramla but that Israeli historians between the 1950s and 1970s tried to differentiate it from Lydda, insisting that the inhabitants of Al-Ramla had violated the terms of surrender, with Benny Morris writing that they "were happy at the possibility given them of evacuating." In a letter to the editor at Commentary, Efraim Karsh writes that there was no expulsion from Ramla.

In the Haganah archives, Morris found the cable from Kiryati Brigade HQ to its officer in charge of Ramle, Zwi Aurback:

- 1. In light of the deployment of 42nd Battalion out of Ramle - you must take for the defence of the town, the transfer of prisoners and the emptying of the town of its inhabitants.

- 2. You must continue the sorting out of the inhabitants, and send the army-age males to a prisoner of war camp. The old, women and children will be transported by vehicle to al Qubab and will be moved across the lines - from there continue on foot.."

Rabin writes of the residents of Lydda that, "We took them on foot to the Bet Horon road, assuming that the Legion would be obliged to look after them, thereby shouldering logistic difficulties which would burden its fighting capacity, making things easier for us." Of the population of Al-Ramla, Rabin writes:

"The inhabitants of Ramleh watched, and learned the lesson: their leaders agreed to be evacuated by the Legion. Great suffering was inflicted upon the men taking part in the eviction action. Soldiers of the Yiftach brigade included youth movement graduates, who had been inculcated with values such as international fraternity and humaneness. The eviction action went beyond the concepts they were used to. There were some fellows who refused to take part in the expulsion action. Prolonged propaganda activities were required after the action, to remove the bitterness of these youth movement groups, and explain why we were obliged to undertake such harsh and cruel action.

Reflecting on these actions, Rabin concluded:

"To day, in hindsight, I think the action was essential. The removal of those fifty thousand Arabs was an important contribution to Israel's security, in one of the most sensitive regions, linking the coastal plain with Jerusalem. After the War of Independence, some of the inhabitants were permitted to return to their home towns."

Sharett-Ben Gurion guidelines

Morris writes that most of the able-bodied young men in Lydda were held in detention centres in the cities, including the mosques and churches. The streets were littered with bodies, and a curfew was in place. Two companies from Kiryati's 42nd Battalion were sent during the night of 12-13 July to reinforce the shocked Third Battalion.

The Israeli cabinet reportedly knew nothing about the expulsion plan, until Bechor-Shalom Sheetrit, minister for minority affairs — who was responsible for the welfare of the Arab citizens — appeared unannounced in Lydda. He was allegedly shocked when he saw that troops were organizing expulsions. Kiryati brigade commander Ben-Gal told him that the IDF was about to take men of military age in Ramla prisoner, and that the rest of the men, as well as the women and children, were to be "taken beyond the border and left to their fate." The same was to happen in Lydda, Sheetrit said he was told.

Sheetrit returned to Tel Aviv for a meeting with Foreign Minister Moshe Sharett, who later met with Ben Gurion to agree on guidelines for how the residents of Lydda and Ramla were to be treated, though Morris writes that Ben Gurion apparently failed to tell Sharett that he himself was the source of the deportation orders. The men agreed that the townspeople should be told anyone who wants to leave may do so, and that anyone who stays is responsible for himself, and that the Israelis will not provide them with food. Women and children were not to be forced to leave, and the monasteries and churches must not be damaged. These guidelines were passed to Operation Danny HQ at 23:30 hours on 12 July:

1. All are free to leave, apart from those who will be detained.

2. To warn that we are not responsible for feeding those who remain.

3. Not to force women, the sick, children and the old to go/walk .

4. Not to touch monasteries and churches.

5. Searches without vandalism.

6. No robbery.

Regarding point 4, Morris notes that neither the original guidelines from Sharett and Ben Gurion, nor the summary from Operation Danny HQ, said that mosques should be left untouched along with monasteries and churches, but he adds that this may have been a simple oversight.

The guidelines convinced Sharett that he had managed to avert the expulsions. Morris writes that Sharett did not realize that, even as he was discussing the issue in Tel Aviv, the expulsions had already begun.

Forced versus voluntary departure

Morris writes that, by 13 July, the wishes of the IDF and those of the residents of Ramla and Lydda had dovetailed. Over the previous three days, the townspeople had undergone aerial bombardment, raids from troops on the ground, had been told to surrender or die, had seen grenades thrown into houses and hundreds of residents killed, had been living under a curfew, and the able-bodied men had been rounded up and were being held by the thousands in the church and mosque. The residents almost certainly concluded that living under Israeli rule was not sustainable.

Nevertheless, Rabin writes in his memoirs that residents "did not leave willingly." "There was no way of avoiding the use of force and warning shots," he writes, "in order to make the inhabitants march the 10-15 miles to the point where they met up with the Legion."

On 13 July, representatives of the Lydda residents asked the IDF for permission for the townspeople to leave, Morris writes, though a minority insisted they wanted to stay. A "deal" was reached with Shmarya Gutman of the IDF that the residents would agree to leave in exchange for the release of the detainees; according to Guttman's own account, he went to the mosque himself and told the detainees they were free to join their families. Notwithstanding that a "deal" may have been reached, Morris writes that most of the troops understood that what followed was an act of deportation, not a voluntary exodus. Operation Danny HQ told the IDF General Staff/Operations at noon on July 13 that " are busy expelling the inhabitants ," and told the HQs of Yiftah, Kiryati, and 8th Brigades at the same time that the "eviction/evacuation " of the residents was underway.

Eyewitness accounts

An officer with Kiryati's 42nd Battalion said that the expulsions from Ramla began at 17:30 hours on July 12. Ramla residents were carried in trucks along the Jerusalem Road until they were 700 metres from Al-Qubab; they then walked to Beit Shanna and Salbit.

Morris writes that Lydda residents were made to walk all the way, possibly because of the earlier sniper fire, or perhaps simply because there were no vehicles, or because the Third Battalion was unconcerned about their fate. Whatever the reason, Lydda residents had to walk 6-7 kilometers to Beit Nabala, then 10-12 kilometers to Barfiliya, along dusty roads in temperatures of 30-35C, carrying their young children and whatever possessions they were able to leave with, either in carts pulled by animals, or on their backs.

Survivor Father Oudeh Rantisi wrote about some the deaths he witnessed along the way, such as a baby falling from his mother's arms and accidentally being crushed by a cart as a result of the general crowding and anxiety of those trying to enter a farm to get food and water. He also recounts having witnessed the shooting and killing of a few people by Israeli soldiers:

When we entered this gate, we saw Jewish soldiers spreading sheets on the ground and each who passed there had to place whatever they had on the ground or be killed. I remember that there was a man I knew from the Hanhan family from Lod who had just been married barely six weeks and there was with him a basket which contained money. When they asked him to place the basket on the sheet he refused - so they shot him dead before my eyes. Others were killed in front of me too, but I remember this person well because I used to know him.

Rantisi also describes some the effects sustained by the lack of adequate provisions among the refugees:

the things I saw on the third day had a big effect on my life. Hundreds lost their lives due to fatigue and thirst. It was very hot during the day and there was no water. I remember that when we reached an abandoned house, they tied a rope around my cousin's child and sent him down into the water. They were so thirsty they started to suck the water from his clothes ... The road to Ramallah had become an open cemetery.

Another refugee, Raja e-Basailah, describes how, after making it to the Arab village of Ni'ilin, he pushed himself through the crowds to procure some water to take back to his mother and a close friend. He hid the water from others who were begging for it and describes being haunted for years afterward by his "hard-hearted" denial of their needs. Because he was blind, Basailah did not see those who perished on the way, but he recalls hearing the exclamations of others describing " that some of those who lay dead had their tongues sticking out covered with dust and down," and how someone recounted to him, " having seen a baby still alive on the bosom of a dead woman, apparently the mother ..."

Allegations of looting

Although the Sharett-Ben Gurion guidelines specified that there was to be no robbery, numerous sources spoke of widespread looting, both of the towns, and of the refugees.

The Economist published a report on August 21 that year, saying that residents were not allowed to take much with them: "The Arab refugees were systematically stripped of all their belongings before they were sent on their trek to the frontier. Household belongings, stores, clothing, all had to be left behind."

Spiro Munayyer, a paramedic and member of Lydda's resistance movement, writes that: "The occupying soldiers had set up roadblocks on all the road leading east and were searching the refugees, particularly the women, stealing their gold jewelry from their necks, wrist and fingers and whatever was hidden in their clothes, as well as money and everything else that was precious and light enough to carry."

George Habash, founder of the PFLP, had been studying medicine in Beirut, but when he heard that Jaffa had fallen to the Israelis, he returned to Lydda, his hometown, to be with his family, only to find himself expelled with them. He told A. Clare Brandabur:

The Israelis were rounding everyone up and searching us. People were driven from every quarter and subjected to complete and rough body searches. You can’t imagine the savagery with which people were treated. Everything was taken — watches, jewelry, wedding rings, wallets, gold. One young neighbor of ours, a man in his late twenties, not more, Amin Hanhan, had secreted some money in his shirt to care for his family on the journey. The soldier who searched him demanded that he surrender the money and he resisted. He was shot dead in front of us. One of his sisters, a young married woman, also a neighbor of our family, was present: she saw her brother shot dead before her eyes. She was so shocked that, as we made our way toward Birzeit, she died of shock, exposure, and lack of water on the way."

Benny Morris writes that Aharon Cohen, director of Mapam's Arab Department, complained to General Allon months after the deportations that troops had been ordered to remove from residents every watch and piece of jewellery, and all their money, so that they would arrive at the Arab Legion without resources, thereby increasing the burden of looking after them. Allon replied that he knew of no such order, but conceded it as a possibility.

A British teacher in Amman, who investigated the condition of the refugees in late July, said she had heard the same story of refugees initially being allowed to leave with some valuables, only to have them removed on the outskirts of the town. Some residents were so exhausted after walking three days in the heat that they had to throw away whatever possessions they were carrying just to survive, or so that they could carry their children instead.

Aftermath

United Nations official Count Folke Bernadotte who visited the refugee camp in Ramallah which housed the majority of the survivors in July 1948 said: "I have made the acquaintance of a great many refugee camps in my life but never have I seen a more ghastly site."

After the war's end Lod and Ramla became predominantly Jewish mixed towns. Residual Palestinian populations that had managed to remain in both towns were concentrated in bounded compounds and were vastly outnumbered by the influx of Jewish immigrants that followed. The residential property rights of the former Palestinian communities of Lydda and Al-Ramla were officially transferred to the Israel's Custodian of Absentee Properties in March 1950.

Artistic representations

The Palestinian artist Ismail Shammout was 19 years old when he left Lydda in the exodus. Shammout portrayed his experience and that of other Palestinian refugees in the piece Where to ..? (1953).

The oil painting on canvas is considered his best known work and enjoys iconic status among Palestinians. In the foreground, it depicts a life-size image of an elderly man dressed in rags carrying a walking stick in his left hand while his right hand grasps the wrist of a crying child. A sleeping toddler on his shoulder is resting his cheek upon the old man's head. Just behind them is a third child crying and walking alone. In the background there is a skyline of an Arab town with a minaret, while in the middle ground there is a withered tree.

A visual of the painting and a discussion of its symbolic dimensions and iconic status are included in In Israeli art historian Gannit Ankori's work Palestinian Art (2006).

See also

- 1948 Palestinian exodus

- Jewish exodus from Arab lands

- Killings and massacres during the 1948 Palestine War

- List of villages depopulated during the Arab-Israeli conflict

References

- Morris, 2003, pp. 176-177; also see Tolan, Sandy. Focus: 60 Years of Division: The Nakba in al-Ramla, Al Jazeera, 21 July 2008, accessed April 29, 2009; Holmes et al., 2001, p. 64; Prior, 1999, p. 205; Peretz Kidron: Truth Whereby Nations Live. In Said and Hitchens, 1998, pp. 90-93.

- ^ Morris, Benny. "Operation Dani and the Palestinian Exodus from Lydda and Ramle in 1948", Middle East Journal, Vol.40, No.1 (Winter, 1986), pp. 82-109.

- Gilbert, 2008, pp. 218-219, and Rantisi (1990), p.25.

- Ron, 2003, p. 145.

-

- In The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947-1949 (1989), Benny Morris writes that "all the Israelis who witnessed the events agreed that the exodus, under a hot July sun, was an extended episode of suffering for the refugees, especially from Lydda. Some were stripped by soldiers of their valuables as they left town or at checkpoints along the way... Quite a few refugees died - from exhaustion, dehydration and disease" (p. 204-211). In The Road to Jerusalem: Glubb Pasha, Palestine and the Jews (2003), he writes that "a handful, and perhaps dozens, died of dehydration and exhaustion" (p. 177). In his 2004 revised edition of The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947-1949, he writes that "Quite a few refugees died on the road east", attributing a figure of 335 dead to Nimr al Khatib, which he describes as "hearsay" (p. 433).

- Norman Finkelstein (2003, p. 55) writes that perhaps as many as 350 died.

- Martin Gilbert (2008, pp. 218-219) writes: "On the eastward march into the hills, and as far as Ramallah, in the intense heat of July, an estimated 355 refugees died from exhaustion and dehydration. 'Nobody will ever know how many children died,' Glubb Pasha commented.

- In the introduction to Spiro Munayyer's "The Fall of Lydda", Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 27, No. 4, pp. 80-98, 1998, Walid Khalidi gives a figure of 350 dead citing an estimate from Aref al-Aref. According to Henry Laurens, Arif al-'Arif's figures break down as follows: 'the number of Arab dead at Lydda at the time of the events of the 12th of July rises to 426, of who 176 (were killed) in the mosque. The total number of dead rises to 1,300: 800 during fighting in the city, the remainder in the exodus'. Henry Laurens, La Question de Palestine, Fayard, Paris, 2007 p.145.

- In The Politics of Denial: Israel and the Palestinian Refugee Problem (Pluto Press 2003, p. 47) Nur Masalha writes that 350 died.

- A number of eyewitnesses spoke of seeing refugees killed for refusing to hand over their belongings e.g.

- Rantisi, Audeh and Beebe, Ralph K. Blessed are the peacemakers: The story of a Palestinian Christian. Eagle 1990, p. 24. Rantisi's story can also be read in Rantisi, Audeh G. and Amash, Charles. Death March, The Link, Volume 33, Issue 3, July-August 2000.

- George Habash in an interview with A. Clare Brandabur. See Reply To Amos Kenan’s "The Legacy of Lydda" and An Interview With PFLP Leader Dr. George Habash, Peuples & Monde', first published January 1990.

- Gilbert, 2008, pp. 218-219.

- ^ Sa'di and Abu-Lughod, 2007, pp. 91-92.

- ^ Monterescu and Rabinowitz, 2007, pp. 16-17.

- Benny Morris, The Birth of the Palestinian Problem Revisited, Cambridge University Press, 2004 p.,425

- Benny Morris, 'The Birth of the Palestinian Problem Revisited, Cambridge Unbiversity Press, 2004 p.427

- Tal, David. War in Palestine, 1948: Strategy and Diplomacy. Routledge, 2004, p. 311.

- Benny Morris, The Birth of the Palestinian Problem Revisited, Cambridge University press, 2004 p.427

- Benny Morris, The Birth of the Palestinian Problem Revisited, Cambridge University Press, 2004 p.428

- Sefer Hapalmach II, p. 565 and PA, pp. 142-163, "Comprehensive Report of the Activities of the Third Battalion from 9 July until 18 July," Third Battalion/Intelligence, July 19, 1948, cited in Morris 1986, p. 88.

- Orren, p. 110 cited in Morris 1986, p. 89.

- Morris (1986) reports that Operation Mickey HQ reported four Israelis dead and 14 wounded; other sources reported two or three dead. See footnote 24, p. 89. Tal (2004) writes that two died.

- ^ A. Clare Brandabur. Reply To Amos Kenan’s "The Legacy of Lydda" and An Interview With PFLP Leader Dr. George Habash, Peuples & Monde', first published January 1990.

- ^ Shipler, David K. "Israel Bars Rabin from Relating '48 Eviction of Arabs," The New York Times, October 23, 1979.

- Bar-Zohar, Michael. Benn Gurion, Tel Aviv: Am Oved, 1977, Vol II, p. 775. Benny Morris writes that Bar-Zohar cites Yitzhak Rabin as his source. For the opposing view, see Itzchaki, Arieh. Latrun. Jerusalem: Cana 1982, Vol II, p. 394. Both Bar-Zohar and Itzchaki cited in Morris, Benny. "Operation Dani and the Palestinian Exodus from Lydda and Ramle in 1948," Middle East Journal, Vol. 40, No. 1 (Winter, 1986), p. 91.

- ^ Peretz Kidron: Truth Whereby Nations Live. In Said and Hitchens, 1998, pp. 90-93.

- Prior, 1999, p. 205.

- The IDF Archives holds two nearly identical copies of the expulsion order. According to Morris, 2004, p. 429, 454, Allon later denied that there had been such an order, saying that the order to evacuate the civilian population of Lydda and Ramle came from the Arab Legion (see also Al Hamishmar, 25 Oct. 1979).

- Prior, 1999, p. 206.

- Efraim Karsh. "Israel's Founding". Commentary.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|acessdate=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - Kiryati HQ to Aurbach, Tel Aviv District HQ (Mishmar) etc., 14:50 hours, 13 July 1948, HA (=Haganah Archive, Tel Aviv) 80\774\\12 (Zvi Aurbach Papers). See also Kiryati HQ to Hail Mishmar HQ Ramle -Shiloni, 19:15 hours, 13 July 1948, HA 80\774\\12. Cited in Morris (2004), p.429, 454

- ^ Sheetrit, Bechor. "A report of the minister's visit to Ramle on 12 July 1948," written on 13 July 1948, and sent to the Prime Minister and other senior ministers on 14 July, Israel State Archives (ISA), FM2564/10, cited in Morris, Benny. "Operation Dani and the Palestinian Exodus from Lydda and Ramle in 1948," Middle East Journal, Vol. 40, No. 1 (Winter, 1986), p. 92.

- Morris 1986, footnote 36, p. 93.

- Shmarya Guttmann cited in Morris, Benny. "Operation Dani and the Palestinian Exodus from Lydda and Ramle in 1948," Middle East Journal, Vol. 40, No. 1 (Winter, 1986), pp. 95-96. Morris finds Guttman's account subjective and impressionistic, but valuable in terms of understanding what went on in Lydda and Ramla during the crucial period.

- Benvenisti et al., 2007, p. 101.

- Rantisi (1990), p.24

- Rantisi (1990), p.25

- Benvenisti et al., 2007, p. 102.

- Pappé (2006), p. 168.

- Pappé (2006), p. 168

- Thomas, 1999, p. 288.

- Ankori, 2006, pp. 48-50.

Bibliography

- Ankori, Gannit (2006), Palestinian art (Illustrated ed.), Reaktion Books, ISBN 1861892594, 9781861892591

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Benvenisti, Eyal; Gans, Chaim; Ḥanafi, Sārī (2007), Israel and the Palestinian refugees (Illustrated ed.), Springer, ISBN 3540681604, 9783540681601

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Finkelstein, Norman G. (2003), Image and reality of the Israel-Palestine conflict (2nd, revised ed.), Verso, ISBN 1859844421, 9781859844427

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Gelber, Yoav (2001), Palestine, 1948: War, Escape and the Emergence of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, Sussex Academic Press, pp. 161–163, ISBN 1902210670, 9781902210674, retrieved 2009-05-04

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Gilbert, Martin (2008), Israel: A History, Key Porter Books, ISBN 1554700663, 9781554700660

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Holmes, Richard; Strachan, Hew; Bellamy, Chris; Bicheno, Hugh (2001), The Oxford companion to military history (Illustrated ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 0198662092, 9780198662099

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Karsh, Efraim (2002), The Arab-Israeli Conflict: The Palestine War 1948, Osprey Publishing, p. 64, ISBN 1841763721, 9781841763729, retrieved 2009-0504

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Monterescu, Daniel; Rabinowitz, Dan (2007), Mixed towns, trapped communities: historical narratives, spatial dynamics, gender relations and cultural encounters in Palestinian-Israeli towns (Illustrated ed.), Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN 0754647323, 9780754647324

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Munayyer, Spiro; Khalidi, Walid (introduction) (1998), "The Fall of Lydda" (pdf), Journal of Palestine Studies, 27 (4), Institute for Palestine Studies: pp. 80-98, retrieved 2009-05-04

{{citation}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - Morris, Benny (1986), "Operation Dani and the Palestinian Exodus from Lydda and Ramle in 1948" (pdf), Middle East Journal, 40 (1): pp. 82-109, retrieved 2009-05-04

{{citation}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - Morris, Benny (1988), The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947-1949, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521330289, 9780521330282

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Morris, Benny (2003), The Road to Jerusalem: Glubb Pasha, Palestine and the Jews, Tauris, ISBN 1860649890, 9781860649899

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Morris, Benny (2004), The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521009677

- Pappé, Ilan (2006), The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, Oxford: Oneworld, ISBN 1851684670

- Rantisi, Audeh G. (1990), Blessed are the peacemakers: the story of a Palestinian Christian, ISBN 0863470599, retrieved 2009-05-04

- Rantisi, Audeh G. (2000), "The Lydda Death March" (pdf), The Link, 33 (3), Americans for Middle East Understanding, retrieved 2009-05-4

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Prior, Michael P. (1999), Zionism and the state of Israel: a moral inquiry (Illustrated ed.), Routledge, ISBN 0415204623, 9780415204620

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Ron, James (2003), Frontiers and ghettos: state violence in Serbia and Israel (Illustrated ed.), University of California Press, ISBN 0520236572, 9780520236578

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Sa'di, Ahmad H.; Abu-Lughod, Lila (2007), Nakba: Palestine, 1948, and the claims of memory (Illustrated ed.), Columbia University Press, ISBN 0231135793, 9780231135795

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Said, Edward W.; Hitchens, Christopher (1988), Blaming the Victims, Verso, ISBN 0860911756

- Thomas, Baylis (1999), How Israel was won: a concise history of the Arab-Israeli conflict (Illustrated ed.), Lexington Books, ISBN 0739100645, 9780739100646

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help)

External links

- Abu-Sitta, Salman (2006): The Origins of Sharon’s Legacy

- Masalha, Nur: Towards the Palestinian Refugees

- Munayyer, Spiro (1998): The fall of Lydda. Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 27, No. 4, pp. 80–98.

- Rantisi, Father Audeh: Survivor´s testimonies, extracts from the memoir, Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center

- Rantisi, Audeh G. and Charles Amash: Death March

- Rantisi, Father Audeh: Would I ever see my home again?,

| Jewish villages depopulated during the 1948 Palestine war | |

|---|---|

| Behind 1949 armistice lines: | |

| Judea and Samaria: | |

| Gush Etzion: | |

| Gaza: | |