| Revision as of 17:46, 27 May 2009 editLapsed Pacifist (talk | contribs)18,229 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 17:59, 27 May 2009 edit undoCollect (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers47,160 edits 'non-labor media"??? no meaning to that one at all I fearNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| The '''Business Plot''' (also the '''Plot Against FDR''' and the '''White House Putsch''') was an alleged ] in 1933 which involved wealthy businessmen plotting a ] to overthrow ] ]. In 1934 retired ] ] ] testified to the McCormack-Dickstein ] that a group of men had approached him as part of a plot to overthrow Roosevelt in a ].<ref>Schlesinger, p. 85 <font size="1">"In March 1934, the ] authorized investigations into "un-American" activities by a special committee headed by ] of ] and ] of ]. The McCormack-Dickstein Committee investigated ] operations in the US, ] and the ], Smedley Butler's allegations, and ] leaders. McCormack used investigators and employed as committee counsel a former ] ] with a good record on ]. Most of the examination of witnesses was carried on in executive sessions. In public sessions, witnesses were free to consult counsel. McCormack was eager to avoid hit-and-run accusation and unsubstantiated testimony. The result was a scrupulous investigation in a highly sensitive area."</font></ref> One of the purported plotters, ], vehemently denied any such plot. In their report, the Congressional committee stated that it was able to confirm Butler's statements other than the proposal from MacGuire. <ref>Schlesinger, p. 85 <font size="1">"As for McCormack's House committee, it declared itself "able to verify all the pertinent statements made by General Butler" except for MacGuire's direct proposal to him, and it considered this more or less confirmed by MacGuire's European reports." </font></ref> However, no prosecutions or further investigations followed. Some historians have questioned whether or not a plot was actually close to execution.<ref name=burk/><ref name=schmidt226/><ref name=schlesinger83/><ref name=sargent/> Contemporary |

The '''Business Plot''' (also the '''Plot Against FDR''' and the '''White House Putsch''') was an alleged ] in 1933 which involved wealthy businessmen plotting a ] to overthrow ] ]. In 1934 retired ] ] ] testified to the McCormack-Dickstein ] that a group of men had approached him as part of a plot to overthrow Roosevelt in a ].<ref>Schlesinger, p. 85 <font size="1">"In March 1934, the ] authorized investigations into "un-American" activities by a special committee headed by ] of ] and ] of ]. The McCormack-Dickstein Committee investigated ] operations in the US, ] and the ], Smedley Butler's allegations, and ] leaders. McCormack used investigators and employed as committee counsel a former ] ] with a good record on ]. Most of the examination of witnesses was carried on in executive sessions. In public sessions, witnesses were free to consult counsel. McCormack was eager to avoid hit-and-run accusation and unsubstantiated testimony. The result was a scrupulous investigation in a highly sensitive area."</font></ref> One of the purported plotters, ], vehemently denied any such plot. In their report, the Congressional committee stated that it was able to confirm Butler's statements other than the proposal from MacGuire. <ref>Schlesinger, p. 85 <font size="1">"As for McCormack's House committee, it declared itself "able to verify all the pertinent statements made by General Butler" except for MacGuire's direct proposal to him, and it considered this more or less confirmed by MacGuire's European reports." </font></ref> However, no prosecutions or further investigations followed. Some historians have questioned whether or not a plot was actually close to execution.<ref name=burk/><ref name=schmidt226/><ref name=schlesinger83/><ref name=sargent/> Contemporary reporting dismissed the plot, with the '']'' characterizing it as a "gigantic hoax."<ref name="nyt112234"/> | ||

| ==Background== | ==Background== | ||

Revision as of 17:59, 27 May 2009

The Business Plot (also the Plot Against FDR and the White House Putsch) was an alleged political conspiracy in 1933 which involved wealthy businessmen plotting a coup d’état to overthrow United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt. In 1934 retired Marine Corps Major General Smedley Butler testified to the McCormack-Dickstein Congressional Committee that a group of men had approached him as part of a plot to overthrow Roosevelt in a coup. One of the purported plotters, Gerald MacGuire, vehemently denied any such plot. In their report, the Congressional committee stated that it was able to confirm Butler's statements other than the proposal from MacGuire. However, no prosecutions or further investigations followed. Some historians have questioned whether or not a plot was actually close to execution. Contemporary reporting dismissed the plot, with the New York Times characterizing it as a "gigantic hoax."

Background

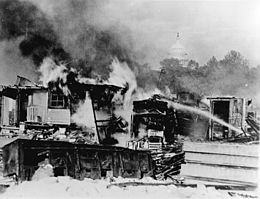

On July 17, 1932, thousands of World War I veterans converged on Washington, D.C., set up tent camps, and demanded immediate payment of bonuses due them according to the Adjusted Service Certificate Law of 1924. This "Bonus Army" was led by Walter W. Waters, a former Army sergeant. The Army was encouraged by an appearance from retired Marine Corps Major General Smedley Butler, who had considerable influence over the veterans, being one of the most popular military figures of the time. A few days after Butler's arrival, President Herbert Hoover ordered the marchers removed, and their camps were destroyed by US Army cavalry troops under the command of General Douglas MacArthur.

Butler, although a self-described Republican, responded by supporting Roosevelt in that year's election.

In a 1995 History Today article Clayton Cramer argued that the devastation of the Great Depression had caused many Americans to question the foundations of liberal democracy. "Many traditionalists, here and in Europe, toyed with the ideas of Fascism and National Socialism; many liberals dallied with Socialism and Communism." Cramer argues that this explains why some American business leaders viewed fascism as a viable system to both preserve their interests and end the economic woes of the Depression.

Events

| This section possibly contains synthesis of material that does not verifiably mention or relate to the main topic. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. (March 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| This section may require cleanup to meet Misplaced Pages's quality standards. No cleanup reason has been specified. Please help improve this section if you can. (March 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

On July 1, 1933, Butler met with MacGuire and Doyle for the first time. Gerald C. MacGuire was a $100 a week bond salesman for Murphy & Company, and member of the Connecticut American Legion who had been an activist for the gold currency efforts that Robert Sterling Clark sponsored. Bill Doyle was commander of the Massachusetts American Legion.

Butler stated he was asked to run for National Commander of the American Legion. On July 3 or 4, Butler held a second meeting with MacGuire and Doyle. He stated they offered to get hundreds of supporters at the American Legion convention to ask for a speech. Around August 1 MacGuire visited Butler alone. Butler stated that MacGuire told him Col.Murphy underwrote the formation of the American Legion in New York, and Butler told MacGuire that the American Legion was "nothing but a strike breaking outfit." Butler never saw Doyle again.

On September 24, MacGuire visited Butler's hotel room in Newark. In late-September Butler met with Robert Clark. Robert Sterling Clark was an art collector and an heir to the Singer Sewing Machine fortune. MacGuire had known Robert S. Clark when he was a Second Lieutenant in China during the Boxer Rebellion. Clark had been nicknamed "the millionaire lieutenant.

During the first half of 1934 MacGuire traveled to Europe, and mailed post cards to Butler. March 6 MacGuire wrote Clark and Clark's attorney a letter describing the Croix de Feu On August 22 Butler met MacGuire at a Hotel, the last time Butler met MacGuire.

On September 13, Paul Comly French a reporter who had once been Butler's personal secretary met MacGuire in his office. In Late September Butler told Van Zandt that co-conspirators would be meeting him at an upcoming Veterans of Foreign Wars convention. On November 20, the Committee began examining evidence. JournalistPaul Comly French broke the story in the Philadelphia Record and New York Post. November 21 – On November 22, The New York Times wrote its first article on the story and criticized it as a "gigantic hoax."

McCormack-Dickstein Committee

The Committee began examining evidence a year later, on November 20, 1934. On November 24 the committee released a statement detailing the testimony it had heard about the plot and its preliminary findings. On February 15, 1935, the committee submitted to the House of Representatives its final report.

During the McCormack-Dickstein Committee hearings, Butler testified that MacGuire attempted to recruit him to lead a coup, promising him an army of 500,000 men for a march on Washington, D.C., and financial backing. Butler testified that the pretext for the coup would be that the president's health was failing.

Despite Butler's support for Roosevelt in the election, and his reputation as a strong critic of capitalism, Butler said the plotters felt his good reputation and popularity were vital in attracting support amongst the general public, and saw him as easier to manipulate than others.

Though Butler had never spoken to them, Butler said that Al Smith, Roosevelt's political foe and former governor of New York, and Irénée du Pont, a chemical industrialist, were the financial and organizational backbone of the plot. The committee chose not to publish these allegations because they were hearsay.

Given a successful coup, Butler said that the plan was for him to have held near-absolute power in the newly created position of "Secretary of General Affairs," while Roosevelt would have assumed a figurehead role.

Those implicated in the plot by Butler all denied any involvement. MacGuire was the only figure identified by Butler who testified before the committee. Others Butler accused were not called to appear to testify because the "committee has had no evidence before it that would in the slightest degree warrant calling before it such men... The committee will not take cognizance of names brought into testimony which constitute mere hearsay."

In response, Butler said that the committee had deliberately edited out of its published findings the leading business people whom he had named in connection with the plot. He said on February 17, 1935 on Radio WCAU, "Like most committees it has slaughtered the little and allowed the big to escape. The big shots weren't even called to testify. They were all mentioned in the testimony. Why was all mention of these names suppressed from the testimony?"

On the final day of the committee. January 29, 1935 John L. Spivak published the first of two articles in Communist magazine New Masses, revealing portion of congressional committee testimony that had been redacted as hearsay. Spivak argued that the plot is part of a Fascist conspiracy of financiers and Jews to take over the USA.

Final resolution

The Congressional committee report said:

- This committee has had no evidence before it that would in the slightest degree warrant calling before it such men as John W. Davis, Gen. Hugh Johnson, General Harbord, Thomas W. Lamont, Admiral Sims, or Hanford MacNider.

- The committee will not take cognizance of names brought into the testimony which constitute mere hearsay.

- This committee is not concerned with premature newspaper accounts especially when given and published prior to the taking of the testimony.

- As the result of information which has been in possession of this committee for some time, it was decided to hear the story of Maj. Gen. Smedley D. Butler and such others as might have knowledge germane to the issue. ...

- In the last few weeks of the committee's official life it received evidence showing that certain persons had made an attempt to establish a fascist government in this country...There is no question that these attempts were discussed, were planned, and might have been placed in execution when and if the financial backers deemed it expedient.

- This committee received evidence from Maj. Gen Smedley D. Butler (retired), twice decorated by the Congress of the United States. He testified before the committee as to conversations with one Gerald C. MacGuire in which the latter is alleged to have suggested the formation of a fascist army under the leadership of General Butler.

- MacGuire denied these allegations under oath, but your committee was able to verify all the pertinent statements made by General Butler, with the exception of the direct statement suggesting the creation of the organization. This, however, was corroborated in the correspondence of MacGuire with his principal, Robert Sterling Clark, of New York City, while MacGuire was abroad studying the various forms of veterans organizations of Fascist character.

Other testimony

Some parts of Gen. Butler's story were supported by the statements of others. Reporter Paul Comly French, reporter for the Philadelphia Record and the New York Evening Post, testified to the same effect. Separately, Veterans of Foreign Wars commander James E. Van Zandt stated that, "Less than two months" after General Butler warned him, "he had been approached by ‘agents of Wall Street’ to lead a Fascist dictatorship in the United States under the guise of a ‘Veterans Organization’ ".

Contemporary reaction

A New York Times editorial dismissed Butler's story as "a gigantic hoax" and a "bald and unconvincing narrative." Thomas W. Lamont of J.P. Morgan called it "perfect moonshine." General Douglas MacArthur, alleged to be the back-up leader of the putsch if Butler declined, referred to it as "the best laugh story of the year." Time Magazine and other publications also scoffed at the allegations.

Later reactions

Historians

Robert F. Burk said, "At their core, the accusations probably consisted of a mixture of actual attempts at influence peddling by a small core of financiers with ties to veterans organizations and the self-serving accusations of Butler against the enemies of his pacifist and populist causes."

Hans Schmidt said, "Even if Butler was telling the truth, as there seems little reason to doubt, there remains the unfathomable problem of MacGuire's motives and veracity. He may have been working both ends against the middle, as Butler at one point suspected. In any case, MacGuire emerged from the HUAC hearings as an inconsequential trickster whose base dealings could not possibly be taken alone as verifying such a momentous undertaking. If he was acting as an intermediary in a genuine probe, or as agent provocateur sent to fool Butler, his employers were at least clever enough to keep their distance and see to it that he self-destructed on the witness stand."

Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. said, "Most people agreed with Mayor La Guardia of New York in dismissing it as a ‘cocktail putsch’ . . . As for the House committee, headed by John McCormack of Massachusetts, it declared itself "able to verify all the pertinent statements made by General Butler", except for MacGuire's direct proposal to him, and it considered this more or less confirmed by MacGuire's European reports. No doubt, MacGuire did have some wild scheme in mind, though the gap between contemplation and execution was considerable, and it can hardly be supposed that the Republic was in much danger".

Jules Archer spoke to McCormack, whom he characterised as a "veteran politician", an adviser to Roosevelt as well as other presidents. He said McCormack told him, "General Smedley Butler was one of the outstanding Americans in our history. I cannot emphasise too strongly the very important part he played in exposing the Fascist plot in the early 1930s backed by and planned by persons possessing tremendous wealth."

James E. Sargent reviewing The Plot to Seize the White House, by Jules Archer, said, "Thus, Butler (and Archer) assumed that the existence of a financially-backed plot meant that fascism was imminent, and that the planners represented a widespread and coherent group, having both the intent and the capacity to execute their ideas. So, when his testimony was criticized, and even ridiculed, in the media, and ignored in Washington, Butler saw (and Archer sees) conspiracy everywhere. Instead, it is plausible to conclude that the honest and straightforward, but intellectually and politically unsophisticated, Butler perceived in simplistic terms what were, in fact, complex trends and events. Thus, he leaped to the simplistic conclusion that the President and the Republic were in mortal danger. In essence, Archer swallowed his hero whole".

Other commentators

The BBC online précis for their documentary program The Whitehouse Coup, says "The coup was aimed at toppling President Franklin D Roosevelt with the help of half-a-million war veterans. The plotters, who were alleged to involve some of the most famous families in America, (owners of Heinz, Birds Eye, Goodtea, Maxwell Hse & George Bush’s Grandfather, Prescott) believed that their country should adopt the policies of Hitler and Mussolini to beat the great depression." In that documentary, author and conspiracy theorist John Buchanan said, "The investigations mysteriously turned to vapor when it comes time to call them to testify. FDR's main interest was getting the New Deal passed, and so he struck a deal in which it was agreed that the plotters would walk free if Wall Street would back off of their opposition to the New Deal and let FDR do what he wanted". The actual progam connected major companies to the American Liberty League, formed by Al Smith, which the program asserted was to be the fascist ruler, and that Prescott Bush was one of the directors of the Hamburg America Line which gave free passage to journalists visiting Germany, and was accused of transporting Nazi spies to the United States.

Bibliography

- Archer, Jules (1973, pub.2007). The Plot to Seize the White House. Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 1-60239-036-3.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Schlesinger Jr., Arthur M. (2003). The Politics of Upheaval: 1935-1936, The Age of Roosevelt, Volume III (The Age of Roosevelt). Mariner Books. ISBN 0-618-34087-4.

- Schmidt, Hans (1998). Maverick Marine: General Smedley D. Butler and the Contradictions of American Military History. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-0957-4. Excerpts of Schmidt's book dealing with the plot are available online.

References

- Schlesinger, p. 85 "In March 1934, the House of Representatives authorized investigations into "un-American" activities by a special committee headed by John W. McCormack of Massachusetts and Samuel Dickstein of New York. The McCormack-Dickstein Committee investigated Nazi operations in the US, William Dudley Pelley and the Silver Shirts, Smedley Butler's allegations, and communist leaders. McCormack used investigators and employed as committee counsel a former Georgia senator with a good record on civil liberties. Most of the examination of witnesses was carried on in executive sessions. In public sessions, witnesses were free to consult counsel. McCormack was eager to avoid hit-and-run accusation and unsubstantiated testimony. The result was a scrupulous investigation in a highly sensitive area."

- Schlesinger, p. 85 "As for McCormack's House committee, it declared itself "able to verify all the pertinent statements made by General Butler" except for MacGuire's direct proposal to him, and it considered this more or less confirmed by MacGuire's European reports."

- ^ Burk, Robert F. (1990). The Corporate State and the Broker State: The Du Ponts and American National Politics, 1925-1940. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-17272-8.

- ^ Schmidt p. 226, 228, 229, 230

- ^ Schlesinger, p. 83

- ^ Sargent, James E. (1974). "Review of: The Plot to Seize the White House, by Jules Archer". The History Teacher. 8 (1): 151–152. doi:10.2307/491493.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Credulity Unlimited". The New York Times. November 22, 1934.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Schmidt, p. 219 "Declaring himself a "Hoover-for-Ex-President Republican," Smedley used the bonus issue and the army's use of gas in routing the (Bonus Expeditionary Force) B.E.F -recalling infamous gas warfare during the Great War- to disparage Hoover during the 1932 general elections. He came out for the Democrats "despite the fact that my family for generations has been Republican," and shared the platform when Republican Senator George W. Norris opened a coast-to-coast stump for FDR in Philadelphia....Butler was pleased with the election results that saw Hoover defeated; although he admitted that he had exerted himself in the campaign more "to get rid of Hoover than to put in Roosevelt," and to "square a debt." FDR, his old Haiti ally, was a "nice fellow" and might make a good president, but Smedley did not expect much influence in the new administration."

- Clayton E. Cramer, "An American Coup d'État?" in History Today, November 1995

- Schmidt, p. 224

- s:McCormack-Dickstein Committee#Testimony of Gerald C. Macguire

- Archer, p. 6.

- This contradicts MacGuire's testimony: "You are a past department commander in the American Legion?" "No, sir; never held an office in the American Legion I have just boon a Legionnaire—oh, I beg your pardon. I did hold one office. I was on the distinguished guest committee of the Legion in 1933, I believe." Wikisource: McCormack-Dickstein Committee report, testimony of Gerald C. MacGuire

- Archer, p. 6

- Wikisource: McCormack-Dickstein Committee report, pg. 1

- Wikisource: McCormack-Dickstein Committee report

- Wikisource: McCormack-Dickstein Committee report

- Archer, p. 178

- Wikisource: McCormack-Dickstein Committee report, pg. 20

- Wikisource: McCormack-Dickstein Committee report

- Wikisource: McCormack-Dickstein Committee report

- Schmidt, p. 239, 241

- ^ Archer, p. 14

- Wikisource: McCormack-Dickstein Committee report, pg. 3

- Wikisource: McCormack-Dickstein Committee report, pg. 10

- Archer, p. 153

- Wiksource: McCormack-Dickstein Committee report, pg. 3 and pg. 20

- Mennonite Church Historical Archives Paul French Biographical Information

- Wikisource: McCormack-Dickstein Committee report, pg. 5

- Archer, p. 139

- ^ Archer, p. x (Foreword)

- Wikisource: McCormack-Dickstein Committee report, Testimony of Maj. Gen. S. D. Butler (ret)

- Wikisource: McCormack-Dickstein Committee report, pg. 2

- Archer, p. 155.

- Schmidt, p. 231

- ^ Public Statment on Preliminary findings of HUAC, November 24, 1934, page 1

- Beam, Alex (May 25 2004). "A Blemish Behind Beauty at The Clark". The Boston Globe: E1.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help): "In his congressional testimony, Butler described Clark as being "known as the "millionaire lieutenant" and was sort of batty, sort of queer, did all sorts of extravagant things. He used to go exploring around China and wrote a book on it, on explorations. He was never taken seriously by anybody. But he had a lot of money." "Clark was certainly eccentric. One of the reasons he sited his fantastic art collection away from New York or Boston was that he feared it might be destroyed by a Soviet bomber attack during the Cold War..."(Clark) was pointed out to me during a trip to Paris," says one on his grandnieces. "He was known to be pro-fascist and on the enemy side. Nobody ever spoke to him.""

Wikisource: McCormack-Dickstein Committee - ^ BBC Radio 4 Document "The White House Coup - Greenham's Hidden Secret"

- Archer, p. 189

- National Archives: The Special Committee on Un-American Activities Authorized To Investigate Nazi Propaganda and Certain Other Propaganda Activities (73A-F30.1) "The (McCormack-Dickstein Committee) conducted public and executive hearings intermittently between April 26 and December 29, 1934, in Washington, DC; New York; Chicago; Los Angeles; Newark; and Asheville, NC, examining hundreds of witnesses and accumulating more than 4,300 pages of testimony."

- Investigation of Nazi Propaganda Activities and Investigation of Certain Other Propaganda Activities: Public Hearings Before the Special Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, Seventy-third Congress, Second Session, at Washington, D.C. p.8-114 D.C. 6 II

Schmidt, p. 245 "HUAC's final report to Congress: "There is no question that these attempts were discussed, were planned, and might have been placed in execution when and if the financial backers deemed it expedient." The committee had verified "all the pertinent statements made by General Butler, with the exception of the direct statement suggesting the creation of the organization."" - Investigation of Nazi Propaganda Activities and Investigation of Certain Other Propaganda Activities: Public Hearings Before the Special Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, Seventy-third Congress, Second Session, at Washington, D.C. p. 111 D.C. 6 II.

- Wikisource: McCormack-Dickstein Committee, testimony of Paul Comly French

- Schlesinger, p 85; Wolfe, Part IV: "But James E. Van Zandt, national commander of the Veterans of Foreign Wars and subsequently a Republican congressman, corroborated Butler's story and said that he, too, had been approached by "agents of Wall Street." "Zandt had been called immediately after the August 22 meeting with MacGuire by Butler and warned that...he was going to be approached by the coup plotters for his support at an upcoming VFW convention. He said that, just as Butler had warned, he had been approached "by agents of Wall Street" who tried to enlist him in their plot.""Says Butler Described. Offer". New York Times: 3. 1934.

{{cite journal}}:|first=has generic name (help);|first=missing|last=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) Quoted material from the NYT

Schmidt, p. 224 But James E. Van Zandt, national commander of the Veterans of Foreign Wars and subsequently a Republican congressman, corroborated Butler's story and said that he, too, had been approached by "agents of Wall Street."

Archer, p.3, 5, 29, 32, 129, 176. For more on Van Zandt, and the Archer quotes, see Unknown author. "James Edward Van Zandt". Coalition to Oppose the Arms Trade (COAT). Retrieved 2006-03-28.{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Schmidt, Hans (1998). Maverick Marine (reprint, illustrated ed.). University Press of Kentucky. p. 224. ISBN 0813109574.

- Author unknown (December 3 1934). "Plot Without Plotters". Time Magazine.

{{cite journal}}:|author=has generic name (help); Check date values in:|date=(help)

Author unknown (November 21 1934). "Gen. Butler Bares 'Fascist Plot' To Seize Government by Force; Says Bond Salesman, as Representative of Wall St. Group, Asked Him to Lead Army of 500,000 in March on Capital -- Those Named Make Angry Denials -- Dickstein Gets Charge". New York Times: 1.{{cite journal}}:|author=has generic name (help); Check date values in:|date=(help);

Philadelphia Record, November 21 and 22, 1934;Time Magazine, 25 February 1935: "Also last week the House Committee on Un-American Activities purported to report that a two-month investigation had convinced it that General Butler's story of a Fascist march on Washington was alarmingly true."

New York Times February 16 1935. p. 1, "Asks Laws To Curb Foreign Agitators; Committee In Report To House Attacks Nazis As The Chief Propagandists In Nation. State Department Acts Checks Activities Of An Italian Consul -- Plan For March On Capital Is Held Proved. Asks Laws To Curb Foreign Agitators, "Plan for “March” Recalled. It also alleged that definite proof had been found that the much publicized Fascist march on Washington, which was to have been led by Major. Gen. Smedley D. Butler, retired, according to testimony at a hearing, was actually contemplated. The committee recalled testimony by General Butler, saying he had testified that Gerald C. MacGuire had tried to persuade him to accept the leadership of a Fascist army." - Archer, p. 173

Philadelphia Post, November 22, 1934 - Wolfe, Part IV: "New York's Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, who was known as the "Little Flower" . . . a (supporter) of the fascist program of Mussolini, coined the term cocktail putsch to describe the Butler story: It's a joke of some kind, he told the wire services, "someone at a party had suggested the idea to the ex-marine as a joke".

- "Controversial editor fired". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. January 14, 2006. Retrieved 2009-03-02.

- http://www.archive.org/details/TheWhitehouseCoup

- Maverick Marine: Excerpt at coat.ncf.ca

Further reading

- Archer, Jules (1973, pub.2007). The Plot to Seize the White House. Skyhorse Publishing.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link)ISBN 1-60239-036-3, Book Information and Chapter Summaries, Executive summary and/or extensive quotes of Jules Archer's book on the subject, mostly on Butler's testimony concerning attempts to bribe him into speaking on behalf of the gold standard. - The History Channel Video: In Search of History: The Plot to Overthrow FDR "While The Plot To Overthrow FDR will astonish those who never learned about this story in school, in the end many viewers may feel as if they are trying to handcuff a shadow."Feran, Tim (February 12 1999). "History Channel Looks At Plot to Oust FDR". Columbus Dispatch (Ohio): 1H.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

- Books with Business Plot chapters

- Seldes, George (1947). 1000 Americans: The Real Rulers of the U.S.A. Boni & Gaer. ASIN: B000ANE968. p. 292-298 Excerpts of the book can be found here.

- Spivak, John L. (1967). A Man in His Time. Horizon Press. ASIN: B0007DMOCW. p. 294-298 Excerpts: Socioeconomic and Political Context of the Plot, General Smedley Butler.

- Colby, Gerard (1984). Du Pont Dynasty: Behind the Nylon Curtain. L. Stuart. ISBN 0-8184-0352-7. p. 324-330 Excerpts of the book about the plot found here.

External links

- U.S. House of Representatives, Special Committee on Un-American Activities, Public Statement, 73rd Congress, 2nd session, (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1934)

- U.S. House of Representatives, Special Committee on Un-American Activities, Investigation of Nazi Propaganda Activities and Investigation of Certain Other Propaganda Activities, Hearings 73-D.C.-6, Part 1, 73rd Congress, 2nd session, (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1935).

- Adams, Cecil (November 18 2005). "Oh, Smedley: Was there really a fascist plot to overthrow the United States government?". The Straight Dope.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Cramer, Clayton (1995). "An American Coup d'État? Plot against Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1934". History Today. 45 (11): 42.

{{cite journal}}: Text "]" ignored (help) Examines Butler's testimony from both sides - LaMonica, Barbara (March–April 1999). "The Attempted Coup Against FDR" ( – ). Probe.

{{cite journal}}: External link in|format= - Sanders, Richard (editor) (2004). "Facing the Corporate Roots of American Fascism". Press for Conversion! (53).

{{cite journal}}:|author=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Spivak, John L. (January 29 1935; February 5 1935). "Wall Street's Fascist Conspiracy: Testimony that the Dickstein MacCormack Committee Suppressed; Wall Street's Fascist Conspiracy: Morgan Pulls the Strings" (PDF). New Masses.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "The Plot Against FDR" History Channel documentary. In public domain.

- Thomson, Mike (2007-07-23). "The Whitehouse Coup". BBC. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Nasser, Alan (2007-10-03). "FDR's Response to the Plot to Overthrow Him". counterpunch.org. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

- Articles needing cleanup from March 2009

- Cleanup tagged articles without a reason field from March 2009

- Misplaced Pages pages needing cleanup from March 2009

- Conflicts in 1933

- 1933 in the United States

- Great Depression in the United States

- Political history of the United States

- Presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt