| Revision as of 20:03, 1 July 2009 view sourceMinisterForBadTimes (talk | contribs)5,591 edits Extended 'peace' section, added 'aftermath' and merged with 'later conflicts'← Previous edit | Revision as of 20:19, 1 July 2009 view source MinisterForBadTimes (talk | contribs)5,591 edits Changes to infobox - I know it won't be popular, but if Persia lost territory then it wasn't a stalemate; but it wasn't much of a Greek victory eitherNext edit → | ||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

| |conflict=The Greco-Persian Wars | |conflict=The Greco-Persian Wars | ||

| |image=] | |image=] | ||

| |caption=Map of the |

|caption=Map of the first phases of the Greco-Persian Wars | ||

| |date=]–] |

|date=]–] | ||

| |result= |

|result=Marginal Greek victory <br/> | ||

| |territory= Thrace and Ionia gain independence from Persia | |||

| The ] successfully punishes by destruction the ] ] and ].<ref> Herodotus book VII,89-95</ref> | |||

| ⚫ | |place=Mainland ], ], ], ], ], and ] | ||

| Persian incursions in the Greek mainland are defeated at land and at sea, while Greek incursion in Egypt and Cyprus don't succeed. | |||

| |territory=] and ] regain independence. Persia loses control over the western coast of ]. | |||

| ⚫ | |place=Mainland ], ], ], and ] | ||

| |casus=Support of the ] | |casus=Support of the ] | ||

| |combatant1=Greek city states |

|combatant1=Greek city states including ] and ] | ||

| |combatant2=] |

|combatant2=] | ||

| |commander1=],<br>],<br>],<br>] †,<br>],<br>] †,<br>] | |commander1=],<br>],<br>] †,<br>],<br>] †,<br>] | ||

| |commander2=],<br>] †,<br>] †,<br>],<br>],<br>],<br>], <br>] | |commander2=],<br>] †,<br>] †,<br>],<br>],<br>],<br>] | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{FixBunching|mid}} | {{FixBunching|mid}} | ||

Revision as of 20:19, 1 July 2009

For other Persian wars, see Roman-Persian Wars, Arab-Persian Wars, Persian Gulf Wars, and Military history of Iran. Template:FixBunching

| The Greco-Persian Wars | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Map of the first phases of the Greco-Persian Wars | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

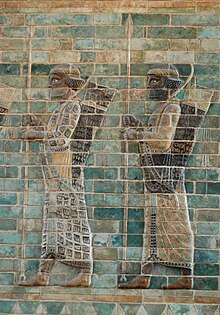

| Greek city states including Athens and Sparta | Achaemenid Empire | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Miltiades, Themistocles, Leonidas I †, Pausanias, Cimon †, Pericles |

Darius I, Mardonius †, Datis †, Artaphernes, Xerxes I, Artabazus, Megabyzus | ||||||||

| Greco-Persian Wars | |

|---|---|

The Greco-Persian Wars were a series of conflicts between several Greek city-states and the Persian Empire that started in 499 BC and lasted until 448 BC. The expression "Persian Wars" usually refers to both Persian invasions of the Greek mainland in 490 BC and in 480-479 BC; in both cases, the allied Greeks successfully repelled the invasions. Not all Greek city-states fought against the Persians; some were neutral and others allied with Persia, especially as its massive armies approached.

Sources

Main article: Herodotus

Almost all the primary sources for the Greco-Persian Wars are Greek; the Persians do not appear to have written anything identifiable as a history of their own. By some distance, the main source for the Greco-Persian Wars is the Greek historian Herodotus. Herodotus, who has been called the 'Father of History', was born in 484 BC in Halicarnassus, Asia Minor (then under Persian overlordship). He wrote his 'Enquiries' (Greek – Historia; English – (The) Histories) around 440-430 BC, trying to trace the origins of the Greco-Persian Wars, which would still have been relatively recent history (the wars finally ending in 449 BC). Herodotus's approach was entirely novel, and at least in Western society, he does seem to have invented 'history' as we know it. As Holland has it: "For the first time, a chronicler set himself to trace the origins of a conflict not to a past so remote so as to be utterly fabulous, nor to the whims and wishes of some god, nor to a people's claim to manifest destiny, but rather explanations he could verify personally."

Many subsequent ancient historians, despite following in his footsteps, derided Herodotus, starting with Thucydides. Nevertheless, Thucydides chose to begin his history where Herodotus left off (at the Siege of Sestos), and must therefore have felt that Herodotus had done a reasonable job of summarising the preceding history. Plutarch criticised Herodotus in his essay "On The Malignity of Herodotus", describing Herodotus as "Philobarbaros" (barbarian-lover), for not being pro-Greek enough, which suggests that Herodotus might have done a reasonable job of being even-handed. A negative view of Herodotus was passed on to Renaissance Europe, though he remained well read. However, since the 19th century his reputation has been dramatically rehabilitated by archaeological finds which have repeatedly confirmed his version of events. The prevailing modern view is that Herodotus generally did a remarkable job in his Historia, but that some of his specific details (particularly troop numbers and dates) should be viewed with skepticism. Nevertheless, there are still some historians who believe Herodotus made up much of his story.

Thucydides wrote principally about the Peloponnesian War, but does provide a brief overview of events between the end of Herodotus's narrative and the beginning of the Peloponnesian war. Thucydides's work is the main source for the Greco-Persian Wars after 479 BC. Among later writers Ephorus wrote in the 4th century BC a universal history which includes the events of these wars. Diodorus Siculus wrote in the 1st century AD a book of history since the beginning of time that also includes the history of this war. The closest thing to a Persian source in Greek literature is Ctesias of Cnedus who was Artaxerxes Mnemon's personal physician wrote a history of Persia according to Persian sources in the 4th century BC. In his work he also mocks Herodotus and claims that his information is accurate since he heard from the Persians. Unfortunately the works of these last writers have not survived complete. Since fragments of them are given in the Myriobiblon which was compiled by Photius that later became Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople in the 9th century AD, in the book Eklogai by the emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitos (913-919 AD) and the Suda dictionary 10th century AD it is believed that they were lost with the destruction of the imperial library of the Holy Palace of Constantinople by the crusaders of the Fourth Crusade in 1204.

Thus historians are forced to supplement Herodotus' and Thucydides' information with works of later writers intended for other uses like 2nd century AD Plutarch's biographies and the tour guide of southern Greece compiled at the same time by the geographer and traveller Pausanias, who is not to be confused with the Spartan general of the same name mentioned later. Some Roman historians in their works give account of this conflict. Justinus who information, as are in Cornelius Nepos's Biographies.

Origins of the conflict

In the dark age that followed the collapse of the Mycenaean civilization, significant numbers of Greeks had emigrated to Asia Minor and settled there. These settlers were from three tribal groups: the Aeolians, Dorians and Ionians. The Ionians had settled about the coasts of Lydia and Caria, founding the twelve cities which made up Ionia. These cities were Miletus, Myus and Priene in Caria; Ephesus, Colophon, Lebedos, Teos, Clazomenae, Phocaea and Erythrae in Lydia; and the islands of Samos and Chios. Although the Ionian cities were independent from each other, they acknowledged their shared heritage, and had a common temple and meeting place, the Panionion. They thus formed a 'cultural league', to which they would admit no other cities, or even other tribal Ionians.

The cities of Ionia had remained independent until they were conquered by the Lydians of Western Asia Minor. The Lydian king Alyattes II attacked Miletus, ending with a treaty of alliance between Miletus and Lydia, which meant that Miletus would have internal autonomy but follow Lydia in foreign affairs. At this time, the Lydians were also in conflict with the Median Empire, and the Milesians sent an army to aid the Lydians in this conflict. Eventually a peaceable settlement was established between the Medes and the Lydians, with the river Halys set up as the frontier between the kingdoms. The famous Lydian king Croesus succeeded his father Alyattes in around 560 BC and then set about conquering the other Greek city states of Asia Minor.

The Persian prince Cyrus led a rebellion against the last Median king Astyages in 553 BC. Although the Persians had been, until this point, a rather backward and irrelevant part of the Median empire, Cyrus was a grandson of Astyages and was moreover supported by part of the Median aristocracy. By 550 BC, the rebellion was over, and Cyrus had emerged victorious, founding the Persian Empire in place of the Median realm in the process. Croesus saw the disruption in the Median/Persian lands as an opportunity to extend his realm and asked the oracle of Delphi whether he should make war. The Oracle is supposed to have replied with one of its famously ambiguous answers, saying that "if Croesus was to cross the river Halys he would destroy a great empire". Blind to the ambiguity of this prophecy, Croesus attacked the Persians, but was eventually defeated and Lydia fell to Cyrus.

While fighting the Lydians, Cyrus had sent messages to the Ionians asking them to revolt against Lydian rule, which the Ionians had refused to do. After Cyrus finished the conquest of Lydia, the Ionian cities now offered to be his subjects under the same terms as they had been subjects of Croesus. Cyrus refused, citing the Ionians' unwillingness to help him previously. The Ionians thus prepared to defend themselves, and Cyrus sent the Median general Harpagus to conquer Ionia. He first attacked Phocaea; the Phocaeans decided to entirely abandon their city and sail into exile in Sicily, rather than become Persian subjects (although many subsequently returned). Some Teians also chose to emigrate when Harpagus attacked Teos, but the rest of the Ionians remained, and were in turn conquered.

In the years following their conquest, the Persians found the Ionians difficult to rule. Elsewhere in the empire, Cyrus was able to identify elite native groups to help him rule his new subjects – such as the priesthood of Judea. No such group existed in Greek cities at this time; while there was usually an aristocracy, this was inevitably divided into feuding factions. The Persians thus settled for sponsoring a tyrant in each Ionian city, even though this drew them into the Ionians' internal conflicts. Furthermore, a tyrant might develop an independent streak, and have to be replaced. The tyrants themselves faced a difficult task; they had to deflect the worst of their fellow citizens' hatred, while staying in the favour of the Persians. While Greek states had in the past often been ruled by tyrants, this was a form of government generally on the decline. Moreover, past tyrants had at least tended (and needed) to be strong and able leaders, whereas the rulers appointed by the Persians were simply place-men. Backed by the Persian military might, these tyrants did not need the support of the population, and could thus rule absolutely. On the eve of the Greco-Persian wars, Ionia (and Greek Asia minor in general) was thus a bubbling cauldron of discontent.

Ionian Revolt (499–493 BC)

Main article: Ionian RevoltThe Ionian Revolt, and associated revolts in Aeolis, Doris, Cyprus and Caria, were military rebellions by several regions of Asia Minor against Persian rule, lasting from 499 to 493 BC. At the heart of the rebellion was the dissatisfaction of the Greek cities of Asia Minor with the tyrants appointed by Persia to rule them, along with the individual actions of two Milesian tyrants, Histiaeus and Aristagoras. In 499 BC the then tyrant of Miletus, Aristagoras, launched a joint expedition with the Persian satrap Artaphernes to conquer Naxos, in an attempt to bolster his position in Miletus (both financially and in terms of prestige). The mission was a debacle, and sensing his imminent removal as tyrant, Aristagoras chose to incite the whole of Ionia into rebellion against the Persian king Darius the Great.

In 498 BC, supported by troops from Athens and Eretria, the Ionians marched on, captured, and burnt Sardis. However, on their return journey to Ionia, they were followed by Persian troops, and decisively beaten at the Battle of Ephesus. This campaign was the only offensive action by the Ionians, who subsequently went on the defensive. The Persians responded in 497 BC with a three pronged attack aimed at recapturing the outlying areas of the rebellion, but the spread of the revolt to Caria meant that the largest army, under Daurises, relocated there. While initially campaigning successfully in Caria, this army was annihilated in an ambush at the Battle of Pedasus. This resulted in a stalemate for the rest of 496 and 495 BC.

By 494 BC the Persian army and navy had regrouped, and they made straight for the epicentre of the rebellion at Miletus. The Ionian fleet sought to defend Miletus by sea, but were decisively beaten at the Battle of Lade, after the defection of the Samians. Miletus was then besieged, captured, and its population was enslaved. This double defeat effectively ended the revolt, and the Carians surrendered to the Persians as a result. The Persians spent 493 BC reducing the cities along the west coast that still held out against them, before finally imposing a peace settlement on Ionia which was generally considered to be both just and fair.

The Ionian Revolt constituted the first major conflict between Greece and the Persian Empire, and as such represents the first phase of the Greco-Persian Wars. Although Asia Minor had been brought back into the Persian fold, Darius vowed to punish Athens and Eretria for their support for the revolt. Moreover, seeing that the myriad city states of Greece posed a continued threat to the stability of his Empire, he decided to conquer the whole of Greece. In 492 BC, the first Persian invasion of Greece, the next phase of the Greco-Persian Wars, would begin as a direct consequence of the Ionian Revolt.

First invasion of Greece (492–490 BC)

Main article: First Persian invasion of Greece

The completion of the pacification of Ionia allowed the Persians to begin planning their next moves; to extinguish the threat to the empire from Greece, and to punish Athens and Eretria. This first Persian invasion of Greece consisted of two main campaigns.

492 BC: Mardonius's Campaign

The first campaign in 492 BC, led by Darius's son-in-law Mardonius, re-subjugated Thrace, which had nominally been part of the Persian empire since 513 BC. Mardonius was also able to force Macedon to become a client kingdom of Persia, whereas it had previously been an independent ally. However, further progress in this campaign was prevented when Mardonius's fleet was wrecked in a storm off the coast of Mount Athos. Mardonius himself was then injured in a raid on his camp by a Thracian tribe, and after this he returned with the expedition to Asia.

The following year, having demonstrated his intentions, Darius sent ambassadors to all parts of Greece, demanding their submission. He received it from almost all of them, excepting Athens and Sparta, both of whom executed the ambassadors. With Athens still defiant, and Sparta now effectively at war with him, Darius ordered a further military campaign for the following year.

490 BC: Datis and Artaphernes' Campaign

In 490 BC Datis and Artaphernes (son of the satrap Artaphernes) were given command of an amphibious invasion force, and set sail from Cilicia. The Persian force sailed from Cilicia firstly to the island of Rhodes, where a Lindian Temple Chronicle records that Datis besieged the city of Lindos, but was unsuccessful. The fleet sailed next to Naxos, in order to punish the Naxians for their resistance to the failed expedition that the Persians had mounted there a decade earlier. Many of the inhabitants fled to the mountains; those that the Persians caught were enslaved. The Persians then burnt the city and temples of the Naxians. The fleet then proceeded to island-hop across the rest of the Aegean on its way to Eretria, taking hostages and troops from each island.

The task force sailed on to Euboea, and to the first major target, Eretria. The Eretrians made no attempt to stop the Persians landing, or advancing, and thus allowed themselves to be besieged, leading to the siege of Eretria. For six days the Persians attacked the walls, with losses on both sides; however, on the seventh day two reputable Eretrians opened the gates and betrayed the city to the Persians. The city was razed, and temples and shrines were looted and burned. Furthermore, according to Darius's commands, the Persians enslaved all the remaining townspeople.

Battle of Marathon

Main article: Battle of Marathon

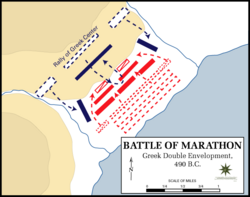

The Persian fleet next headed south down the coast of Attica, landing at the bay of Marathon, roughly 25 miles (40 km) from Athens Under the guidance of Miltiades, the general with the greatest experience of fighting the Persians, the Athenian army marched to block the two exits from the plain of Marathon. Stalemate ensued for five days, until part of the Persian force, including the cavalry, was sent by sea to attack Athens directly (under Artaphernes). With the cavalry threat to their hoplite phalanx removed, and needing to act quickly to prevent the conquest of Athens, the Athenians attacked the remaining Persian army at dawn on the sixth day. Despite the numerical advantage of the Persians, the hoplites proved devastatingly effective, routing the Persians wings and achieving a double envelopment of the centre; the remnants of the Persian army fled to their ships and left the battle. Herodotus records that 6,400 Persian bodies were counted on the battlefield, and it is unknown how many perished in the swamps. The Athenians lost 192 men and the Plataeans 11.

As soon as the Persian survivors had put to sea the Athenians marched as quickly as possible to Athens. They arrived in time to prevent Artaphernes from securing a landing in Athens. Seeing his opportunity lost, Artaphernes brought the year's campaign to an end and returned to Asia.

The Battle of Marathon was a watershed in the Greco-Persian wars, showing the Greeks that the Persians could be beaten. It also highlighted the superiority of the more heavily armoured Greek hoplites, and showed their potential when used wisely. The Battle of Marathon is perhaps now more famous as the inspiration for the Marathon race. Although historically inaccurate, the legend of a Greek messenger running to Athens with news of the victory, and then promptly expiring, became the inspiration for this athletics event, introduced at the 1896 Athens Olympics, and originally run between Marathon and Athens.

Interbellum (490–480 BC)

Persian Empire

After the defeat at Marathon, Darius ordered all the cities of his vast empire to provide warriors, ships, horses, and provisions to raise a great army for a second invasion but before he was ready to attack (in 486 BC) an insurrection broke out in Egypt, forcing a delay. In the next year Darius died after a reign of thirty-six years. His only failures in life were that he could not defeat Scythia or capture Greece, although the tyrant of Athens had sent earth and water to Persia in 507 BC when faced with Spartan aggression. His son and successor Xerxes I was at first preoccupied with suppressing the revolt in Egypt and a later one in Babylon before he could turn his attention westward to the European side of the Aegean. It wasn't until 480 BC that the expedition was ready to proceed. Like his father's, his only failure was that he could not capture Greece, having chosen not to fight Scythia.

The Persians had the sympathy of a number of Greek city-states, including Argos, which had pledged to defect when the Persians reached their borders. The Aleuades family that ruled Larissa in Thessaly saw the invasion as an opportunity to extend their power. Thebes was willing to pass to the Persian side when Xerxes' army reached their borders, and did so immediately following Thermopylae, though Herodotus hints that at Thermopylae it was already well known that Thebes had capitulated.

Greek City States

Meanwhile Alexander I of Macedon, who had supported the Greeks during the Ionian revolt, had been forced to submit to Persia after the Mardonius' campaign. He was sympathetic to the Hellenic side, however, and sent valuable information to the Greeks regarding Xerxes' plans and movements.

Leonidas I assumed the throne of Sparta about 488 BC, succeeding his brother.

In Athens the hero of Marathon, Miltiades, convinced the Athenians to campaign in the Cyclades Islands in order to secure their frontier. His expedition failed and he was sorely wounded. His failure prompted an outcry on his return to Athens, enabling his political rivals to exploit his fall from grace. Charged with treason, he was sentenced to death, but the sentence was commuted to a fine. He died of his wound before his sentence was carried out and was buried with honor.

A new political leadership formed in Athens with Themistocles leading the democratic party and Aristides the aristocratic party. Ostracism was first exercised in 488 BC leading to the exile of politicians who advocated submission to Persia.

During this time Athens was at war with Aegina.The ability of the Aeginian fleet to land unopposed at will in Attica and conduct raids led to public discontent. Themistocles convinced his fellow citizens to use the profits from the Laurion silver mines to construct a fleet. Alarm came to Greece after the Persian preparations had advanced to the construction of the Hellespont bridges and the channel at Athos.

In autumn of 481 BC Sparta, in cooperation with Athens, called a congress in the temple of Poseidon on the isthmus of Corinth. Every Greek city-state that had not then fallen to the Persians was called except Massalia and her colonies and Cyrene. General reconciliation was preached. Athens and Aegina were publicly reconciled. Messengers were sent to the cities that had not sent emissaries. The colonies of Sicily and Southern Italy were called, but reportedly refused unless the Syracusan king, Gelon, was given command, a right the Spartans refused to part with. Additionally, Diodorus reports that the Persians and Carthaginians had signed a treaty to co-ordinate invasions, keeping the sizeable Sicilian and Italian reinforcements in check. The only help received was one ship from Crotone, which fought in the battle of Salamis. Argos and Crete refused to send emissaries, and the oracle of Delphi did not take part. It continued, as it had since the beginning of the century, to issue oracles that the flood of the Persian Army would drown Greece. Corcyra promised assistance, but then rescinded the offer. They sent a fleet off the Peloponnese that simply monitored the situation. For the most part, the alliance was made up of the Peloponnesian city-states, Euboea island and Attica.

Second Invasion of Greece (480–479 BC)

Main article: Second Persian invasion of GreecePersian preparations

Since this was to be a full scale invasion it required long-term planning, stock-piling and conscription. Xerxes decided that the Hellespont would be bridged to allow his army to cross to Europe, and that a canal should be dug across the isthmus of Mount Athos (rounding which headland, a Persian fleet had been destroyed in 492 BC). These were both feats of exceptional ambition, which would have been beyond any contemporary state. By early 480 BC, the preparations were complete,

In 481 BC, after roughly four years of preparation, Xerxes began mustering the troops for the invasion of Europe in Asia minor. The next spring, the army marched towards Europe, crossing the Hellespont on two pontoon bridges.

Size of the Persian Forces

- For more information see Size of the Persian Forces

The numbers of troops which Xerxes mustered for the second invasion of Greece have been the subject of endless dispute. Modern scholars tend to reject as unrealistic the figures of 2.5 million given by Herodotus and other ancient sources as a result of miscalculations or exaggerations on the part of the victors. The topic has been hotly debated but the consensus revolves around the figure of 200,000.

The size of the Persian fleet is also disputed, although perhaps less so. Herodotus gives a number of 1,207, which is concurred with (approximately) by other ancient authors. The numbers are (by ancient standards) consistent, and this could be interpreted that a number around 1,200 is correct. Among modern scholars some have accepted this number, although suggesting that the number must have been lower by the Battle of Salamis. Other recent works on the Persian Wars reject this number, 1,207 being seen as more of a reference to the combined Greek fleet in the Iliad generally claim that the Persians could have launched no more than around 600 warships into the Aegean.

Greek preparations

The Athenians had also been preparing for war with the Persians since the mid-480s BC, and in 482 BC the decision was taken to build a massive fleet of triremes that would be necessary for them to fight the Persians. In 481 BC Xerxes sent ambassadors around Greece asking for earth and water, but making the very deliberate omission of Athens and Sparta. Support thus began to coalesce around these two leading states and a confederate alliance of Greek city-states was formed. This was remarkable for the disjointed Greek world, especially since many of the city-states in attendance were still technically at war with each other.

Size of Greek forces

- For more information, see Size of Greek forces

The allies had no 'standing army', nor was there any requirement to form one; since they were fighting on home territory, they could muster armies as and when required. Different sized Allied forces thus appeared throughout the campaign.

Early 480 BC: Thrace, Macedonia and Thessaly

Having crossed into Europe in April 480 BC, the Persian army began its march to Greece, taking 3 1/2 months to travel unopposed from the Hellespont to Therme. It paused at Doriskos where it was joined by the fleet. Xerxes reorganized the troops into tactical units replacing the national formations used earlier for the march.

The Allied 'congress' met again in the spring of 480 BC and agreed to defend the narrow Vale of Tempe, on the borders of Thessaly, and thereby block Xerxes's advance. However, once there, they were warned by Alexander I of Macedon that the vale could be bypassed and that the army of Xerxes was overwhelming, and the Greeks retreated. Shortly afterwards, they received the news that Xerxes had crossed the Hellespont. A second strategy was therefore suggested by Themistocles to the allies. The route to southern Greece (Boeotia, Attica and the Peloponnesus) would require the army of Xerxes to travel through the very narrow pass of Thermopylae. This could easily be blocked by the Greek hoplites, despite the overwhelming numbers of Persians. Furthermore, to prevent the Persians bypassing Thermopylae by sea, the Athenian and allied navies could block the straits of Artemisium. This dual strategy was adopted by the congress. However, the Peloponnesian cities made fall-back plans to defend the Isthmus of Corinth should it come to it, whilst the women and children of Athens had been evacuated en masse to the Peloponnesian city of Troezen.

August 480 BC: Battles of Thermopylae & Artemisium

Main articles: Battle of Thermopylae and Battle of ArtemisiumThe estimated time of arrival of Xerxes at Thermopylae coincided uncomfortably with both the truce for the Olympic games, and the Spartan festival of Carneia, during both of which warfare was considered sacrilegious. Nevertheless, the Spartans considered the threat so grave that they despatched their king Leonidas I with his personal bodyguard (the Hippeis) of 300 men (in this case, the customary elite young men in the Hippeis were replaced by veterans who already had children). Leonidas was supported by contingents from the Allied Peloponnesian cities, and other forces which the Allies picked up en route to Thermopylae. The Greeks proceeded to occupy the pass, rebuilt the wall the Phocians had built at the narrowest point of the pass, and waited for Xerxes's arrival.

When the Persians arrived at Thermopylae in mid-August, they initially waited for three days for the Greeks to pass. When Xerxes was eventually persuaded that the Greeks intended to contest the pass, he sent his troops to attack. However, the Greek position was ideally suited to hoplite warfare, the Persian contingents being forced to attack the Phalanx head on. The Greeks thus withstood two full days of battle and everything Xerxes could throw at them. However, on the second day, they were betrayed by a local resident named Ephialtes who revealed a mountain path that led behind the Greek lines to Xerxes. Aware that they were being outflanked, Leonidas dismissed the bulk of the Greek army, remaining to guard the rear with perhaps 2,000 men. On the final day of the battle, the remaining Greeks sallied forth from the wall to meet the Persians in the wider part of the pass in an attempt to slaughter as many Persians as they could, but eventually they were all killed or captured.

Simultaneous with the battle at Thermopylae, a Greek naval force of 271 triremes defended the Straits of Artemisium against the Persians, thus protecting the flank of the forces at Thermopylae. Here the Allied fleet held off the Persians for three days; however, on the third evening the Greeks received news of the fate of Leonidas and the Allied troops and Thermopylae. Since the Greek fleet was badly damaged, and since it no longer needed to defend the flank of Thermopylae, the Greeks retreated from Artemisium to the island of Salamis.

September 480 BC: Battle of Salamis

Main article: Battle of SalamisVictory at Thermopylae meant that all Boeotia fell to Xerxes; and left Attica open to invasion. The remaining population of Athens was evacuated, with the aid of the Allied fleet, to Salamis. The Peloponnesian Allies began to prepare a defensive line across the Isthmus of Corinth, building a wall, and demolishing the road from Megara, thus abandoning Athens to the Persians. Athens thus fell to the Persians; the small number of Athenians who had barricaded themselves on the Acropolis were eventually defeated, and Xerxes then ordered Athens to be torched.

The Persians had now captured most of Greece, but Xerxes had perhaps not expected such defiance; his priority was now to complete the war as quickly as possible If Xerxes could destroy the Allied navy, he would be in a strong position to force a Greek surrender; conversely by avoiding destruction, or as Themistocles hoped, by destroying the Persian fleet, the Greeks could prevent the completion of the conquest. The Allied fleet thus remained off the coast of Salamis into September, despite the imminent arrival of the Persians. Even after Athens fell, the Allied fleet still remained off the coast of Salamis, trying to lure the Persian fleet to battle. Partly as a result of subterfuge on the part of Themistocles, the navies met in the cramped Straits of Salamis. There, the Persian numbers were an active hindrance, as ships struggled to maneuver and became disorganised. Seizing the opportunity, the Greek fleet attacked, and scored a decisive victory, sinking or capturing at least 200 Persian ships, and thus securing the Peloponnessus.

According to Herodotus, Xerxes attempted to build a causeway across the channel to attack the Athenian evacuees on Salamis, after the loss of the battle but this project was soon abandoned. With the Persians' naval superiority removed, Xerxes feared that the Greeks might sail to the Hellespont and destroy the pontoon bridges. His general Mardonius volunteered to remain in Greece and complete the conquest with a hand-picked group of troops, whilst Xerxes retreated to Asia with the bulk of the army. Mardonius over-wintered in Boeotia and Thessaly; the Athenians were thus able to return to their burnt city for the winter.

June 479 BC: Battles of Plataea and Mycale

Main articles: Battle of Plataea and Battle of MycaleOver the winter, there seems to have been some tension between the Allies. In particular, the Athenians, who were not protected by the Isthmus, but whose fleet were the key to the security of the Peloponnesus, felt hard done by, and refused to join the Allied navy in Spring. Mardonius remained in Thessaly, knowing an attack on the Isthmus was pointless, whilst the Allies refused to send an army outside the Peloponessus. Mardonius moved to break the stalemate, by offering peace to the Athenians using Alexander I of Macedon as intermediate. The Athenians made sure that a Spartan delegation was on hand to hear the offer, but rejected it. Athens was thus evacuated again, and the Persians marched south and re-took possession of it. Mardonius now repeated his offer of peace to the Athenian refugees on Salamis. Athens, along with Megara and Plataea sent emissaries to Sparta demanding assistance, and threatening to accept the Persian terms if not. The Spartans thus assembled a huge Allied army and marched to meet the Persians.

When Mardonius heard the Greek army was on the march, he retreated into Boeotia, near Plataea, trying to draw the Greeks into open terrain where he could use his cavalry. The Greek army however, under the command of the regent Pausanias, stayed on high ground above Plataea to protect themselves against such tactics. After several days of maneuver and stalemate, Pausanias ordered a night-time retreat towards their original positions. This, however, went awry, leaving the Athenians, and Spartans and Tegeans isolated on separate hills, with the other contingents scattered further away near Plataea. Seeing that the Persians might never have a better opportunity to attack, Mardonius ordered his whole army forward. However, the Persian infantry proved no match for the heavily armoured Greek hoplites, and the Spartans broke through to Mardonius's bodyguard and killed him. The Persian force thus dissolved in rout; 40,000 troops managed to escape via the road to Thessaly, but the rest fled to the Persian camp where they were trapped and slaughtered by the Greeks, thus finalising the Greek victory.

On the afternoon of the Battle of Plataea, Herodotus tells us that rumour of the Greek victory reached the Allied navy, at that time off the coast of Mount Mycale in Ionia. Their morale boosted, the Allied marines fought and won a decisive victory at the Battle of Mycale the same day, destroying the remnants of the Persian fleet, crippling Xerxes' sea power, and marking the ascendancy of the Greek fleet.

Greek counterattack (479–478 BC)

Mycale and Ionia

Mycale was, in many ways, the beginning of a new phase in the conflict, in which the Greeks would go on the offensive against the Persians. The most immediate result of the victory at Mycale was to trigger a second revolt amongst the Greek cities of Asia Minor. The Samians and Milesians had actively fought against the Persians at Mycale, thus openly declaring their rebellion, and the other cities followed in their example.

Sestos

Shortly after Mycale, the Allied fleet sailed to the Hellespont to break down the pontoon bridges, but found that this was already done. The Peloponnesians sailed home, but the Athenians remained to attack the Chersonesos, still held by the Persians. The Persians in the region, and their allies made for Sestos, the strongest town in the region, and the Athenians laid siege to them there. After a protracted siege, Sestos fell to the Athenians, marking the beginning of a new phase in the Greco-Persian Wars, the Greek reconquest. This is where Herodotus ends his Historia.

Unification of Macedonia

Alexander of Macedon, encouraged by the Greek success at Plataea and his victory over the Persians in the Strymon river, expanded his realm to include the other Greek tribes living east of Mount Pindus. He conquered the land east until the banks of the Strymon river, conquering several non-Greek tribes living there. He founded three cities to expand Greek influence into his newly conquered land, and managed to expand his realm east of the Strymon river, gaining part of Mount Pangaion and its famous gold mines. Thus he created the largest individual Greek state in terms of area, population, and income. However, despite its potential, the kingdom of Macedon retained a splintered and feudal style of government, with the king holding little central authority and subservient to the combined force of the aristocracy. Only in the 4th century BC, when the city-states in its south were in general decline, would Phillip II of Macedon, a king with great political genius, firmly unite the Macedonian aristocracy into a strong, centralized monarchy and expand the kingdom beyond these borders and raise it to prominence.

Cyprus

In 478 BC, a fleet composed of 20 Peloponnesian ships, 30 Athenian ships under Aristides, and other allied forces, with the general command given to Pausanias, sailed to Cyprus. There they succeeded in liberating the Greek cities, but did not succeed in their sieges against the Phoenician cities. Thus Cyprus remained a base of the Persian fleet.

Byzantium

The Greek fleet then sailed to Byzantium. Control of the Hellespont and Bosporus was of vital importance to Athens, since throughout the classical age Athens produced only 40% of the food required to feed her population, the rest being imported from the Greek colonies of the Black Sea.

The city of Byzantium fell after a siege. Many Persians including nobility fell prisoner to the Greek forces. Pausanias, who was of the royal house of Agis, was greatly impressed by the new way of life he witnessed and adopted it. He started wearing Persian dress and offering Persian-style banquets. He also mistreated the Ionian delegates. His Persian-style behaviour scandalised both the Ionians and the Peloponnesians and Pausanias was recalled to Sparta. There he faced charges that he was plotting with the Persian king to become tyrant of Greece, that he was in secret communication with him and that he had asked his daughter as his wife. He was acquitted of those charges, found guilty only of mistreating individuals in their private affairs and sentenced not to lead another campaign outside Sparta. Being impatient he took a warship from Hermion and travelled back to Byzantium. No longer welcome there, he crossed the Propontis to the Troas region where he stayed for some time. What he did there is completely unknown. He was recalled to Sparta by special envoy where he was to be brought against charges that he was again plotting with the King of Kings and that he was planning a helot revolution. On his way back, while he was inside the Spartan state limits, he saw the ephoroi, the elected council of five that ruled Sparta, approaching and one of them signalled to him that he was doomed. He took refuge in a nearby temple, where he died of starvation several days later. Some modern historians, based on that he was never condemned and that had he been in league with the Persians he would have sought refuge there and not return, claim this was all a fabrication by his political enemies in Sparta.

In the meantime, in 477 BC the Spartans had sent Dorkis as general in Byzantium with a small force. The Ionians, with the memories of Pausanias's mistreatment of them fresh, asked them to leave. Relieved, the Spartans withdrew, no longer wishing to continue fighting the Persians.

Wars of the Delian League (477–450 BC)

Delian League

Main article: Delian LeagueAfter Byzantium, Sparta was eager to end her involvement in the war. The Spartans were of the view that, with the liberation of mainland Greece, and the Greek cities of Asia Minor, the war's purpose had already been reached. There was also perhaps a feeling that securing long-term security for the Asian Greeks would prove impossible. In the aftermath of Mycale, the Spartan king Leotychides had proposed transplanting all the Greeks from Asia Minor to Europe as the only method of permanently freeing them from Persian dominion. Xanthippus, the Athenian commander at Mycale, had furiously rejected this; the Ionian cities were originally Athenian colonies, and the Athenians, if no-one else, would protect the Ionians. This marked the point at which the leadership of the Greek Alliance effectively passed to the Athenians. With the Spartan withdrawal after Byzantium, the leadership of the Athenians became explicit.

The loose alliance of city states which had fought against Xerxes's invasion had been dominated by Sparta and the Peloponnesian league. With the withdrawal of these states, a congress was called on the holy island of Delos to institute a new alliance to continue the fight against the Persians. This alliance, now including many of the Aegean islands, was formally constituted as the 'First Athenian Alliance', commonly known as the Delian League. According to Thucydides, the official aim of the League was to "avenge the wrongs they suffered by ravaging the territory of the king." In reality, this goal was divided into three main efforts - to prepare for future invasion, to seek revenge against Persia, and to organize a means of dividing spoils of war. The members were given a choice of either offering armed forces or paying a tax to the joint treasury; most states chose the tax. League members swore to have the same friends and enemies, and dropped ingots of iron into the sea to symbolize the permanence of their alliance. The Athenian politician Aristides would spend the rest of his life occupied in the affairs of the alliance, dying (according to Plutarch) a few years later in Pontus, whilst determining what the tax of new members was to be.

Campaigns against Persia

Main article: Wars of the Delian LeagueThroughout the 470s BC, the Delian League campaigned in Thrace and the Aegean to remove the remaining Persian garrisons from the region, primarily under the command of the Athenian politician Cimon. In the early part of the next decade, Cimon began campaigning in Asia Minor, seeking to strengthen the Greek position there. At the Battle of the Eurymedon in Pamphylia, the Athenians and allied fleet achieved a stunning double victory, destroying a Persian fleet and then landing the ships' marines to attack and rout the Persian army. After this battle, the Persians took an essentially passive role in the conflict, anxious not to risk battle, where possible.

Towards the end of the 460s BC, the Athenians took the ambitious decision to support a revolt in the Egyptian satrapy of the Persian empire. Although the Greek task force achieved initial success, they were unable to capture the Persian garrison in Memphis, despite a 3 year long siege. The Persians then counterattacked, and the Athenian force was itself besieged for 18 months, before being wiped out. This disaster, coupled with ongoing warfare in Greece, dissuaded the Athenians from resuming conflict with Persia. In 451 BC, a truce was agreed in Greece, and Cimon was able to lead an expedition to Cyprus. However, whilst besieging Kition Cimon died, and the Athenian force decided to withdraw, winning another double victory at the Battle of Salamis-in-Cyprus in order to extricate themselves. This campaign marked the end of hostilities between the Delian League and Persia, and therefore the end of the Greco-Persian Wars.

Peace with Persia

After the Battle of Salamis-in-Cyprus, Thucydides makes no further mention of conflict with the Persians, simply saying that the Greeks returned home. Diodorus, on the other hand, claims that in the aftermath of Salamis, a full-blown peace treaty (the "Peace of Callias") was agreed with the Persians. Diodorus was probably following the history of Ephorus at this point, who in turn was presumably influenced by his teacher Isocrates — from whom we have the earliest reference to the supposed peace, in 380 BC. Even during the 4th century BC the idea of the treaty was controversial, and two authors from that period, Callisthenes and Theopompus appear to reject its existence.

It is possible that the Athenians had attempted to negotiate with the Persians previously. Plutarch suggests that in the aftermath of the victory at the Eurymedon, Artaxerxes had agreed a peace treaty with the Greeks, even naming Callias as the Athenian ambassador involved. However, as Plutarch admits, Callisthenes denied that such a peace was made at this point (ca. 466 BC). Herodotus also mentions, in passing, an Athenian embassy headed by Callias, which was sent to Susa to negotiate with Artaxerxes. This embassy included some Argive representatives and can probably be therefore dated to ca. 461 BC (after forging of the alliance between Athens and Argos). This embassy may have been an attempt to reach some kind of peace agreement, and it has even been suggested that the failure of these hypothetical negotiations led to the Athenian decision to support the Egyptian revolt. The ancient sources therefore disagree as to whether there was an official peace or not, and if there was, when it was agreed.

Opinion amongst modern historians is also split; for instance, Fine accepts the concept of the Peace of Callias, whereas Sealey effectively rejects it. Holland accepts that some kind of accommodation was made between Athens and Persia, but no actual treaty. Fine argues that Callisthenes's denial that a treaty was made after the Eurymedon does not preclude a peace being made at another point. Further, he suggests that Theopompus was actually referring to a treaty that had allegedly been negotiated with Persia in 423 BC. If these views are correct, it would remove one major obstacle to the acceptance of the treaty's existence. A further argument for the existence of the treaty is the sudden withdrawal of the Athenians from Cyprus in 450 BC, which makes most sense in the light of some kind of peace agreement. On the other hand, if there was indeed some kind of accommodation, Thucydides's failure to mention it is odd. In his digression on the pentekontaetia his aim is to explain the growth of Athenian power, and such a treaty, and the fact that the Delian allies were not released from their obligations after it, would have marked a major step in the Athenian ascendancy. Conversely, it has been suggested that certain passages elsewhere in Thucydides's history are best interpreted as referring to a peace agreement. There is thus no clear consensus amongst modern historians as to the treaty's existence.

If the treaty did indeed exist, its terms were humiliating for Persia. The ancient sources which give details of the treaty are reasonably consistent in their description of the terms:

- All Greek cities of Asia were to 'live by their own laws' or 'be autonomous' (depending on translation).

- Persian satraps (and presumably their armies) were not to travel west of the Halys (Isocrates) or closer than a day's journey on horseback to the Aegean Sea (Callisthenes) or closer than three days' journey on foot to the Aegean Sea (Ephorus and Diodorus).

- No Persian warship was to sail west of Phaselis (on the southern coast of Asia Minor), nor west of the Cyanaean rocks (probably at the eastern end of the Bosporus, on the north coast).

- If the terms were observed by the king and his generals, then the Athenians were not to send troops to lands ruled by Persia.

Aftermath & later conflicts

Towards the end of the conflict with Persia, the process by which the Delian League became the Athenian Empire reached its conclusion. The allies of Athens were not released from their obligations to provide either money or ships, despite the cessation of hostilities. In Greece, the First Peloponnesian War between the power-blocs of Athens and Sparta, which had continued on-off since 460 BC, finally ended in 445 BC, with the agreement of a thirty year truce. However, the growing enmity between Sparta and Athens would lead, just 14 years later, into the outbreak of the Second Peloponnesian War. This disastrous conflict, which dragged on for 27 years, would eventually result in the utter destruction of Athenian power, the dismemberment of the Athenian empire, and the establishment of a Spartan hegemony over Greece. However, not just Athens suffered — the conflict would significantly weaken the whole of Greece.

Repeatedly defeated in battle by the Greeks, and plagued by internal rebellions which hindered their ability to fight the Greeks, after 450 BC Artaxerxes I and his successors instead adopted a policy of divide-and-rule. Avoiding fighting the Greeks themselves, the Persians instead attempted to set Athens against Sparta, regularly bribing politicians to achieve their aims. In this way, they ensured that the Greeks remained distracted by internal conflicts, and were unable to turn their attentions to Persia. There was no open conflict between the Greeks and Persia until 396 BC, when the Spartan king Agesilaus briefly invaded Asia Minor; as Plutarch points out, the Greeks were far too busy overseeing the destruction of their own power to fight against the "barbarians".

If the wars of the Delian League shifted the balance of power between Greece and Persia in favour of the Greeks, then the subsequent half-century of internecine conflict in Greece did much to restore the balance of power to Persia. The Persians entered the Peloponnesian War in 411 BC forming a mutual-defence pact with Sparta and combining their naval resources against Athens in exchange for sole Persian control of Ionia. In 404 BC when Cyrus the Younger attempted to seize the Persian throne, he recruited 13,000 Greek mercenaries from all over the Greek world of which Sparta sent 700-800, believing they were following the terms of the treaty and unaware of the army's true purpose. After the failure of Cyrus, Persia tried to regain control of the Ionian city-states. The Ionians refused to capitulate and called upon Sparta for assistance, which she provided, in 396–395 BC. Athens, however, sided with the Persians, which led in turn to another large scale conflict in Greece, the Corinthian War. In 387 BC, Sparta, confronted by an alliance of Corinth, Thebes and Athens during the Corinthian War, sought the aid of Persia to shore up her position. Under the so-called "King's Peace" which brought the war to an end, Artaxerxes II demanded and received the return of the cities of Asia Minor from the Spartans, in return for which the Persians threatened to make war on any Greek state which did not make peace. This humiliating treaty, which undid all the Greek gains of the previous century, sacrificied the Greeks of Asia Minor so that the Spartans could maintain their hegemony over Greece. It is in the aftermath of this treaty that Greek orators began to refer to the Peace of Callias (whether fictional or not), as a counterpoint to the shame of the King's Peace, and a glorious example of the "good old days" when the Greeks of the Aegean had been freed from Persian rule by the Delian League.

No other Greek force challenged Persia for nearly 60 years until Phillip II of Macedon, who, in 338 BC formed an alliance called οι Ελληνες (the Greeks), modelled after the alliance of 481 BC, and set in motion an invasion of the western part of Asia Minor. He was murdered before he could carry out his plan. His son, Alexander III of Macedon, known as Alexander the Great, set out in 334 BC with 38,000 soldiers. Within three years his army had conquered the Persian Empire and brought the Achaemenid dynasty to an end, bringing Greek culture up to the banks of the Indus river.

See also

References

- The Timetables of History by Bernard Grun. New Third Revised Edition. ISBN 067174271X

- Holland, ppxxiii–xxv

- Cicero, On the Laws I, 5

- ^ Holland, ppxvi–xvii

- Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, e.g. I, 22

- Holland, p xxiv

- David Pipes. "Herodotus: Father of History, Father of Lies". Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ Holland, p377

- Fehling, pp1–277.

- ^ Herodotus I, 142–151

- Herodotus I, 142

- Herodotus I, 143

- Herodotus I, 148

- Herodotus I, 22

- Herodotus I, 74–75

- Herodotus I, 26

- ^ Holland, pp9–12

- Herodotus I, 53

- Holland, pp13–14

- ^ Herodotus I, 141

- Herodotus I, 163

- Herodotus I, 164

- Herodotus I, 169

- ^ Holland, 147–151

- ^ Fine, pp269–277

- Holland, pp155–157

- ^ Holland, p177–178

- Herodotus VI, 43

- Holland, p153

- ^ Herodotus VI, 44

- Herodotus VI, 45

- ^ Herodotus VI 48

- ^ Holland, pp181–183

- Lind. Chron. D 1-59 in C. Higbie (2003)

- ^ Holland, pp183-186

- ^ Herodotus VI, 96

- Herodotus VI, 100

- ^ Herodotus VI, 101

- Herodotus VI, 102

- Holland, pp191-193

- ^ Holland, pp195-197

- ^ Herodotus VI, 117

- Siegel, Janice (August 2, 2005). "Dr. J's Illustrated Persian Wars". Retrieved 2007-10-17.

- Herodotus VI, 115

- Herodotus VI, 116

- Holland, pp198

- Herodotus VII,138

- Herodotus VII,149-152

- Herodotus VII,6

- Herodotus VI,132

- Cornelius Nepos, Miltiades VII

- Aristotle, Athenian Constitution 22.4

- Plutarch, Themistocles 4

- Cornelius Nepos, Themistocles II

- Herodotus VII,145

- Herodotus VII,158

- Diodorus 11.1.4

- Herodotus VII,149

- Herodotus VII,169

- Herodotus VII,168

- Holland, pp213-214

- Herodotus VII, 35

- de Souza, Philip (2003). The Greek and Persian Wars, 499-386 BC. Osprey Publishing. p. 41. ISBN 1-84176-358-6.

- Köster, A.J. Studien zur Geschichte des Antikes Seewesens. Klio Belheft 32 (1934)

- Οι δυνάμεις των Ελλήνων και των Περσών (The forces of the Greeks and the Persians), E Istorika no.164 19/10/2002

- Holland, p320

- Green, Peter, The Greco-Persian Wars. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press. 1996

- Burn, A.R., "Persia and the Greeks" in The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 2: The Median and Achaemenid Periods, Ilya Gershevitch, ed. New York: Cambridge University Press. 1985.

- Briant, Pierre, From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire, Peter Daniels, trans. Indiana: Eisenbrauns. 2002

- ^ Persian Fire. Holland, T. Abacus, ISBN 978-0-349-11717-1

- Herodotus VII, 32

- Herodotus VII, 145

- Herodotus VII, 100

- Holland, 248-249

- ^ Herodotus VII, 173

- Holland pp255-257

- Herodotus VIII, 40

- ^ Holland, pp257-259

- Holland, pp262-264

- Herodotus VII, 210

- Holland, p274

- Herodotus VII, 223

- Herodotus VIII, 2

- Herodotus VIII, 21

- Herodotus VIII, 41

- Holland, p300

- Holland, pp305-306

- ^ Holland, pp327-329

- Holland, pp308-309

- Holland, p303

- Herodotus VIII, 63

- Holland, pp310-315

- Herodotus VIII, 89

- Holland, pp320-326

- Herodotus VIII, 97

- Herodotus VIII, 100

- ^ Holland, pp333-335

- ^ Holland, pp336-338

- Herodotus IX, 7

- Herodotus IX, 10

- Holland, p339

- ^ Holland, pp342-349

- Herodotus IX, 59

- Herodotus IX, 62

- Herodotus IX, 63

- Herodotus IX, 66

- Herodotus IX, 65

- Holland, pp350-355

- Herodotus IX, 100

- Holland, pp357-358

- Lazenby, p247

- Thucydides I, 89

- ^ Herodotus IX, 114

- Thucydides 2,99

- Thucydides 1.94

- Thucydides 1.95

- Thucydides I,128

- Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους = History of the Greek nation volume Γ1, Athens 1972

- Thucydides 1.95

- ^ Holland, p362

- ^ Thucydides I, 96

- Plutarch, Aristides, 26

- Sealey, p250

- Plutarch, Cimon, 12

- ^ Plutarch, Cimon, 13

- Thucydides I, 104

- Thucydides I, 109

- Sealey, pp271–273

- ^ Thucydides I, 112

- ^ Plutarch, Cimon, 19

- ^ Diodorus XII, 4

- ^ Fine, p360

- ^ Sealey, p280

- Herodotus VII, 151

- Kagan, p84

- Sealey, p281

- ^ Holland, p366 Cite error: The named reference "h366" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Fine, p363

- ^ Sealey, p282

- Kagan, p128

- Holland, p371

- Xenophon, Hellenica II, 2

- ^ Dandamaev, p256

- Xenophon, Hellenica V, I

- Dandamaev, p294

Bibliography

Ancient Sources

- Herodotus, The Histories)

- Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War)

- Xenophon, Anabasis, Hellenica

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives; Themistocles, Aristides, Pericles, Cimon

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica

- Cornelius Nepos, Biographies, Miltiades, Themistocles

Modern Sources

- Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους (History of the Greek Nation) volumes Β (1971) and Γ1 (1972),Ekdotiki Athinon, Athens

- Bengston, Hermann, ed., The Greeks and the Persians: From the Sixth to the Fourth Centuries. New York: Delacorte Press. 1965

- Briant, Pierre, From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire, Peter Daniels, trans. Indiana: Eisenbrauns. 2002

- Burn, A.R., "Persia and the Greeks" in The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 2: The Median and Achaemenid Periods, Ilya Gershevitch, ed. New York: Cambridge University Press. 1985.

- Cook, J.M., The Persian Empire. New York: Shocken Books. 1983.

- Green, Peter, The Greco-Persian Wars. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press. 1996

- Holland, Tom (2006). Persian Fire: The First World Empire and the Battle for the West. ISBN 0385513119.

- Hignett, C., Xerxes' Invasion of Greece. Oxford: The Calrendon Press. 1963.

- Olmstead, A.T., History of the Persian Empire. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1948.

- Pomeroy, Sarah B., Stanley Burstein, Walter Donlan, and Jennifer Tolbert Roberts, Ancient Greece: A Political, Social, and Cultural History'. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1999.

- Brown Reference ltd, Atlas of World History Sandcastle books Ltd. 2006.

External links

- The Persian Wars at History of Iran on Iran Chamber Society

- Article in Greek about Salamis, includes Marathon and Xerxes' campaign

- EDSITEment Lesson 300 Spartans at the Battle of Thermopylae: Herodotus’ Real History

Template:Ancient Greek and Roman Wars

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

Categories: