| Revision as of 16:58, 10 March 2006 editReddi (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users58,350 edits →Techniques: minimize such a factor, with← Previous edit | Revision as of 19:37, 10 March 2006 edit undoWilliam M. Connolley (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers66,008 editsm I prefer the version before Reddi's fiddling (*please* learn to use preview...). Revert way back to IsaccsurNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| :{{otheruses}} | :{{otheruses}} | ||

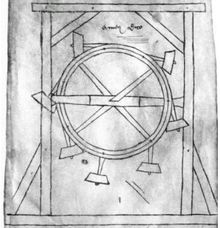

| ] (about 1230)]] | ] (about 1230)]] | ||

| '''Perpetual motion''' refers to a condition in which |

'''Perpetual motion''' refers to a condition in which an object moves forever without the expenditure of any limited internal or external source of ]. | ||

| As well as being poetically descriptive of motions beyond the scale of human lifetimes, for example in the phrase "the stars in perpetual motion wheeled overhead", the term is commonly used to refer to actual attempts to build machines which display this phenomenon. | |||

| ⚫ | '''Perpetual motion machines''' (the ] term '''''perpetuum mobile''''' is not uncommon) are a class of ] machines which would produce useful energy in a way which would violate the established ]. It is generally accepted that perpetual motion machines cannot work. Specifically, perpetual motion machines would violate either the first or second ]. Perpetual motion machines are |

||

| In the real world, friction is ''always'' larger than zero, so an object in perpetual motion implies work being continuously done to overcome this natural retarding process. | |||

| ⚫ | '''Perpetual motion machines''' (the ] term '''''perpetuum mobile''''' is not uncommon) are a class of ] machines which would produce useful energy in a way which would violate the established ]. It is generally accepted that perpetual motion machines cannot work. Specifically, perpetual motion machines would violate either the first or second ]. Perpetual motion machines are divided into two subcategories defined by which law of thermodynamics would have to be broken in order for the device to be a ''true'' perpetual motion machine. | ||

| == Basic principles == | == Basic principles == | ||

| Line 17: | Line 21: | ||

| By minimizing friction and other causes of dissipation, it is possible to produce a good ''approximation'' to a perpetual motion machine of the second kind. Planetary systems (such as the earth and moon) could be considered an example. Planets, moons, and stars spin without any fuel, batteries, muscle, cost, or other limited power. Planets don't rotate forever however; energy in such system is dissipated via ], by friction with the dust and gas in space, and presumably also very slowly via ]. | By minimizing friction and other causes of dissipation, it is possible to produce a good ''approximation'' to a perpetual motion machine of the second kind. Planetary systems (such as the earth and moon) could be considered an example. Planets, moons, and stars spin without any fuel, batteries, muscle, cost, or other limited power. Planets don't rotate forever however; energy in such system is dissipated via ], by friction with the dust and gas in space, and presumably also very slowly via ]. | ||

| In an otherwise completely empty Newtonian universe, a single particle could travel |

In an otherwise completely empty Newtonian universe, a single particle could travel for ever at constant velocity with no violation of the laws of physics -- though of course no energy could be extracted from it without slowing it down. For example, an electron can spin around a nucleus in an atom of matter indefinitely unless it or the atom is disrupted in some way. | ||

| == Just how impossible is impossible? == | == Just how impossible is impossible? == | ||

| Scientists and engineers accept the possibility that the current understanding of the laws of physics may be incomplete or incorrect; a perpetual motion device may not be ''impossible'', but overwhelming ] would be required to justify rewriting the laws of physics. Any proposed perpetual motion design offers a potentially instructive challenge to physicists: we know it can't work (because of the laws of thermodynamics), so explain ''how'' it fails to work. The difficulty (and the value) of such an exercise depends on the subtlety of the proposal; the best ones tend to arise from physicists' own ]s. Because the principles of thermodynamics are so well established, serious proposals for perpetual motion machines are met with disbelief on the part of physicists, which makes a discussion of the merits (if any) of the proposal difficult if not impossible. | Scientists and engineers accept the possibility that the current understanding of the laws of physics may be incomplete or incorrect; a perpetual motion device may not be ''impossible'', but overwhelming ] would be required to justify rewriting the laws of physics. Any proposed perpetual motion design offers a potentially instructive challenge to physicists: we know it can't work (because of the laws of thermodynamics), so explain ''how'' it fails to work. The difficulty (and the value) of such an exercise depends on the subtlety of the proposal; the best ones tend to arise from physicists' own ]s. Because the principles of thermodynamics are so well established, serious proposals for perpetual motion machines are met with disbelief on the part of physicists, which makes a discussion of the merits (if any) of the proposal difficult if not impossible. | ||

| Though perpetual motion may be impossible, near-perpetual motion |

Though perpetual motion may be impossible, near-perpetual motion - motion lasting thousands to billions of years - may be possible in a machine. Near-perpetual motion is a reality in nature: in the rotation of planets, stars and electrons, for example. If such a thing could be duplicated in a lab, man-made near-perpetual motion could become a reality. Planets and electrons have no significant drag/friction because the ] of the object is thousands of times stronger than the slowing effect caused by the friction in the system. | ||

| == Thought experiments == | == Thought experiments == | ||

| Line 31: | Line 35: | ||

| == Techniques == | == Techniques == | ||

| Some ideas recur repeatedly in perpetual motion machine designs. For instance: | |||

| Some ideas recur repeatedly in perpetual motion machine designs, such as ], ]s, ], ], ], ], ], ]s of "space-time", and ]. In the real world, friction is ''always'' larger than zero, so an object in perpetual motion implies work being continuously done to overcome this natural retarding process. Furthermore, the ''always'' present element of friction wears and degrades a device's moving components (shortening it's lifespan). Several designs have attempted to minimize such a factor, with varying levels of success. | |||

| The seemingly mysterious ability of ''magnets'' to influence motion at a distance without any apparent energy source has long appealed to inventors |

The seemingly mysterious ability of '''magnets''' to influence motion at a distance without any apparent energy source has long appealed to inventors. Unfortunately, a constant magnetic field does no ] because the force it exerts on any particle is always at right angles to its motion; a changing field can do work, but requires energy to sustain. A "fixed" magnet can do work, but energy is dissipated in the process, typically weakening the magnet's strength over time. Thus, when a magnet does work by lifting an iron weight, some of the work that was put into magnetizing the magnet is being used to lift the weight, and the strength of the magnet is reduced correspondingly. When the weight is removed from the magnet, the work required to do this restores the strength of the magnet, minus losses due to friction. | ||

| ''Gravity'' also acts at a distance, without an apparent energy source. But to get energy out of a gravitational field (for instance, by dropping a heavy object, producing kinetic energy as it falls) you have to put energy in (for instance, by lifting the object up), and some energy is always dissipated in the process. A typical application of gravity in a perpetual motion machine is ], whose key idea is itself a recurring theme, often called the ''overbalanced wheel'': Moving weights are attached to a wheel in such a way that they fall to a position further from the wheel's center for one half of the wheel's rotation, and closer to the center for the other half. Since weights further from the center apply a greater ], the result is (or would be, if such a device worked) that the wheel rotates forever. The moving weights may be hammers on pivoted arms, or rolling balls, or mercury in tubes; the principle is the same. | '''Gravity''' also acts at a distance, without an apparent energy source. But to get energy out of a gravitational field (for instance, by dropping a heavy object, producing kinetic energy as it falls) you have to put energy in (for instance, by lifting the object up), and some energy is always dissipated in the process. A typical application of gravity in a perpetual motion machine is ], whose key idea is itself a recurring theme, often called the '''overbalanced wheel''': Moving weights are attached to a wheel in such a way that they fall to a position further from the wheel's center for one half of the wheel's rotation, and closer to the center for the other half. Since weights further from the center apply a greater ], the result is (or would be, if such a device worked) that the wheel rotates forever. The moving weights may be hammers on pivoted arms, or rolling balls, or mercury in tubes; the principle is the same. | ||

| Gravity and magnetism are an attractive combination indeed, and a frequently rediscovered design has a ball pulled up by a magnetic field and then rolling down under the influence of gravity, in a cycle. (At the highest point, the ball is supposed to have acquired enough speed to escape the magnet's influence.) | Gravity and magnetism are an attractive combination indeed, and a frequently rediscovered design has a ball pulled up by a magnetic field and then rolling down under the influence of gravity, in a cycle. (At the highest point, the ball is supposed to have acquired enough speed to escape the magnet's influence.) | ||

| To extract work from heat, thus producing a perpetual motion machine of the second kind, the most common approach (dating back at least to ]) is ''unidirectionality''. Only molecules moving fast enough and in the right direction are allowed through the demon's trap door. In a ], forces tending to turn the ratchet one way are able to do so while forces in the other direction aren't. A diode in a heat bath allows through currents in one direction and not the other. These schemes typically fail in two ways: either maintaining the unidirectionality costs energy (Maxwell's demon needs light to look at all those particles and see what they're doing), or the unidirectionality is an illusion and occasional big violations make up for the frequent small non-violations (the Brownian ratchet will be subject to internal Brownian forces and therefore will sometimes turn the wrong way). | To extract work from heat, thus producing a perpetual motion machine of the second kind, the most common approach (dating back at least to ]) is '''unidirectionality'''. Only molecules moving fast enough and in the right direction are allowed through the demon's trap door. In a ], forces tending to turn the ratchet one way are able to do so while forces in the other direction aren't. A diode in a heat bath allows through currents in one direction and not the other. These schemes typically fail in two ways: either maintaining the unidirectionality costs energy (Maxwell's demon needs light to look at all those particles and see what they're doing), or the unidirectionality is an illusion and occasional big violations make up for the frequent small non-violations (the Brownian ratchet will be subject to internal Brownian forces and therefore will sometimes turn the wrong way). | ||

| ''Atmospheric pressure'' varies widely on the Earth and shows a diurnal (daily) rhythm. ]s have been used to wind gearings during these changes. Various natural forms of ''radiant energy'' have been contemplated. ''Telluric currents'' are extremely low frequency electrical current that occurs naturally over large underground areas at or near the surface of the Earth. ''Atmospheric electricity'' is the regular diurnal variations of the Earth's atmospheric electromagnetic network (or, more broadly, any planet's electrical system in its layer of gases). Some have investigated the production of energy and power via earth's electricity and have used ]s to charge a circuit's ]s. These ''would not'' be a source of true perpetual motion, since they rely on an external and "limited" (though long-lived and vast) energy source. These would be more near-perpetual motion machines, theoretically possessing a very long lifespan. In addition, proposed devices that would utilize zero-point energy, vacuum energy, or the quantum fluxuation of "space-time" to run could not be ''true'' perpetual motion, since they rely on an external energy source. | |||

| == Inventions and patents == | == Inventions and patents == | ||

| Line 50: | Line 52: | ||

| * An early description of a perpetual motion machine was by ] in ]. He described a wheel that he claimed would run forever. | * An early description of a perpetual motion machine was by ] in ]. He described a wheel that he claimed would run forever. | ||

| * ] in ] described, in a thirty-three page manuscript, a perpetual motion machine of the second kind. | * ] in ] described, in a thirty-three page manuscript, a perpetual motion machine of the second kind. | ||

| * In the ], ] (with the help of ]) developed a working perpetual motion machine of sorts: a clock (known as ]) powered by changes in atmospheric pressure. Cox was quite open about the workings of his machine, unlike many perpetual motion inventors. The clock still exists today (but was deactivated by the clock's relocation). {{ref|Hume}} | * In the ], ] (with the help of ]) developed a working perpetual motion machine of sorts: a clock (known as ]) powered by changes in ]. Cox was quite open about the workings of his machine, unlike many perpetual motion inventors. The clock still exists today (but was deactivated by the clock's relocation). {{ref|Hume}} | ||

| * ] (also known as Orffyreus) created a series of claimed perpetual motion machines in the 18th Century. | * ] (also known as Orffyreus) created a series of claimed perpetual motion machines in the 18th Century. | ||

| Line 58: | Line 60: | ||

| * Gamgee developed the ], a perpetual motion machine of the second kind. Varley, though, did discover in 1867 that an ] did not need to be started with a conventional prime mover. He used the ] to induce enough field strength in the stator windings to get a generator running. {{ref|bunch}} | * Gamgee developed the ], a perpetual motion machine of the second kind. Varley, though, did discover in 1867 that an ] did not need to be started with a conventional prime mover. He used the ] to induce enough field strength in the stator windings to get a generator running. {{ref|bunch}} | ||

| * Other 19th century inventors such as ], an admirer of ], claimed to be able to tap into radiant energy sources utilizing ] ] currents interacting with the ]. The energy would be derived from the "running river" of the aether. Several demonstrations by Moray were done where 50 ] of power were generated for several days from an antenna connected to a series of transformers, capacitors, and other components. However, all plans and knowledge were kept secret by Moray, demonstration was not verified, and patents were never granted. | * Other 19th century inventors such as ], an admirer of ], claimed to be able to tap into ] sources utilizing ] ] currents interacting with the ]. The energy would be derived from the "running river" of the aether. Several demonstrations by Moray were done where 50 ] of power were generated for several days from an antenna connected to a series of transformers, capacitors, and other components. However, all plans and knowledge were kept secret by Moray, demonstration was not verified, and patents were never granted. | ||

| Devising these machines is a favourite pastime of many ]s, who often come up with elaborate machines in the style of ] or ]. These designs may appear to work on paper at first glance, but have various flaws or obfuscated external power sources that render them useless in practice. This sort of "invention" has become common enough that the ] (USPTO) has made an official policy of refusing to grant ]s for perpetual motion machines without a working model. One reason for this concern is that a few "inventors" have used official patents to convince gullible potential investors that their machine is "approved" by the Patent Office. The USPTO has granted a few patents for motors that are claimed to run without net energy input. These patents were issued because it was not obvious from the patent that a perpetual motion machine was being claimed. Some of these are: | Devising these machines is a favourite pastime of many ]s, who often come up with elaborate machines in the style of ] or ]. These designs may appear to work on paper at first glance, but have various flaws or obfuscated external power sources that render them useless in practice. This sort of "invention" has become common enough that the ] (USPTO) has made an official policy of refusing to grant ]s for perpetual motion machines without a working model. One reason for this concern is that a few "inventors" have used official patents to convince gullible potential investors that their machine is "approved" by the Patent Office. The USPTO has granted a few patents for motors that are claimed to run without net energy input. These patents were issued because it was not obvious from the patent that a perpetual motion machine was being claimed. Some of these are: | ||

| Line 79: | Line 81: | ||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| * ''Main'': ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | * ''Main'': ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | ||

| * ''Science'': ], ], ], ], ] | * ''Science'': ], ], ], ], ] | ||

| * ''People'': ], ], ], ] | * ''People'': ], ], ], ] | ||

Revision as of 19:37, 10 March 2006

- For other uses, see Perpetual motion (disambiguation).

Perpetual motion refers to a condition in which an object moves forever without the expenditure of any limited internal or external source of energy.

As well as being poetically descriptive of motions beyond the scale of human lifetimes, for example in the phrase "the stars in perpetual motion wheeled overhead", the term is commonly used to refer to actual attempts to build machines which display this phenomenon.

In the real world, friction is always larger than zero, so an object in perpetual motion implies work being continuously done to overcome this natural retarding process.

Perpetual motion machines (the Latin term perpetuum mobile is not uncommon) are a class of hypothetical machines which would produce useful energy in a way which would violate the established laws of physics. It is generally accepted that perpetual motion machines cannot work. Specifically, perpetual motion machines would violate either the first or second laws of thermodynamics. Perpetual motion machines are divided into two subcategories defined by which law of thermodynamics would have to be broken in order for the device to be a true perpetual motion machine.

Basic principles

Perpetual motion machines violate one or both of the following two laws of physics: the first law of thermodynamics and the second law of thermodynamics. The first law of thermodynamics is essentially a statement of conservation of energy. The second law has several statements, the most intuitive of which is that heat flows spontaneously from hotter to colder places; the most well known is that entropy always increases, or at the least stays the same; another statement is that no heat engine (an engine which produces work while moving heat between two places) can be more efficient than a Carnot heat engine. As a special case of this, any machine operating in a closed cycle cannot only transform thermal energy to work in a region of constant temperature. See the respective articles, and thermodynamics, for more information.

Machines which claim not to violate either of the two laws of thermodynamics but rather claim to generate energy from unconventional sources are sometimes referred to as perpetual motion machines, although they do not meet the standard criteria for the name. By way of example, it is quite possible to design a clock or other low-power machine to run on the differences in barometric pressure or temperature between night and day. Such a machine has a source of energy, albeit one from which it is quite impractical to produce power in quantity.

Classification

It is customary to classify perpetual motion machines as follows:

- A perpetual motion machine of the first kind produces strictly more energy than it uses, thus violating the law of conservation of energy.

- A machine that produces (in still-usable form) exactly as much energy as it uses is a perpetual motion machine of the second kind, which continues running forever (not necessarily doing any usable work) by converting its waste heat back into mechanical work. This need not violate the law of conservation of energy, but does violate the less fundamental second law of thermodynamics (see also entropy). More generally, any device that converts heat into work without loss can be considered a perpetual motion of the second kind, since it could be used to make something that moves perpetually.

By minimizing friction and other causes of dissipation, it is possible to produce a good approximation to a perpetual motion machine of the second kind. Planetary systems (such as the earth and moon) could be considered an example. Planets, moons, and stars spin without any fuel, batteries, muscle, cost, or other limited power. Planets don't rotate forever however; energy in such system is dissipated via tidal forces, by friction with the dust and gas in space, and presumably also very slowly via gravitational waves.

In an otherwise completely empty Newtonian universe, a single particle could travel for ever at constant velocity with no violation of the laws of physics -- though of course no energy could be extracted from it without slowing it down. For example, an electron can spin around a nucleus in an atom of matter indefinitely unless it or the atom is disrupted in some way.

Just how impossible is impossible?

Scientists and engineers accept the possibility that the current understanding of the laws of physics may be incomplete or incorrect; a perpetual motion device may not be impossible, but overwhelming evidence would be required to justify rewriting the laws of physics. Any proposed perpetual motion design offers a potentially instructive challenge to physicists: we know it can't work (because of the laws of thermodynamics), so explain how it fails to work. The difficulty (and the value) of such an exercise depends on the subtlety of the proposal; the best ones tend to arise from physicists' own thought experiments. Because the principles of thermodynamics are so well established, serious proposals for perpetual motion machines are met with disbelief on the part of physicists, which makes a discussion of the merits (if any) of the proposal difficult if not impossible.

Though perpetual motion may be impossible, near-perpetual motion - motion lasting thousands to billions of years - may be possible in a machine. Near-perpetual motion is a reality in nature: in the rotation of planets, stars and electrons, for example. If such a thing could be duplicated in a lab, man-made near-perpetual motion could become a reality. Planets and electrons have no significant drag/friction because the momentum of the object is thousands of times stronger than the slowing effect caused by the friction in the system.

Thought experiments

Serious work in theoretical physics often involves thought experiments that test the boundaries of understanding of physical laws. Some such thought experiments involve apparent perpetual motion machines, and insight may be had from understanding why they either don't work or don't violate the laws of physics. For example:

- Maxwell's demon: a thought experiment which led to physicists considering the interaction between entropy and information

- Feynman's "Brownian ratchet": a "perpetual motion" machine which extracts work from thermal fluctuations and appears to run forever but only runs as long as the environment is warmer than the ratchet

- "Cosmic background space drive": where redshift/blueshift of the background radiation is used to drive a rocket's engine

Techniques

Some ideas recur repeatedly in perpetual motion machine designs. For instance:

The seemingly mysterious ability of magnets to influence motion at a distance without any apparent energy source has long appealed to inventors. Unfortunately, a constant magnetic field does no work because the force it exerts on any particle is always at right angles to its motion; a changing field can do work, but requires energy to sustain. A "fixed" magnet can do work, but energy is dissipated in the process, typically weakening the magnet's strength over time. Thus, when a magnet does work by lifting an iron weight, some of the work that was put into magnetizing the magnet is being used to lift the weight, and the strength of the magnet is reduced correspondingly. When the weight is removed from the magnet, the work required to do this restores the strength of the magnet, minus losses due to friction.

Gravity also acts at a distance, without an apparent energy source. But to get energy out of a gravitational field (for instance, by dropping a heavy object, producing kinetic energy as it falls) you have to put energy in (for instance, by lifting the object up), and some energy is always dissipated in the process. A typical application of gravity in a perpetual motion machine is Bhaskara's wheel, whose key idea is itself a recurring theme, often called the overbalanced wheel: Moving weights are attached to a wheel in such a way that they fall to a position further from the wheel's center for one half of the wheel's rotation, and closer to the center for the other half. Since weights further from the center apply a greater torque, the result is (or would be, if such a device worked) that the wheel rotates forever. The moving weights may be hammers on pivoted arms, or rolling balls, or mercury in tubes; the principle is the same.

Gravity and magnetism are an attractive combination indeed, and a frequently rediscovered design has a ball pulled up by a magnetic field and then rolling down under the influence of gravity, in a cycle. (At the highest point, the ball is supposed to have acquired enough speed to escape the magnet's influence.)

To extract work from heat, thus producing a perpetual motion machine of the second kind, the most common approach (dating back at least to Maxwell's demon) is unidirectionality. Only molecules moving fast enough and in the right direction are allowed through the demon's trap door. In a Brownian ratchet, forces tending to turn the ratchet one way are able to do so while forces in the other direction aren't. A diode in a heat bath allows through currents in one direction and not the other. These schemes typically fail in two ways: either maintaining the unidirectionality costs energy (Maxwell's demon needs light to look at all those particles and see what they're doing), or the unidirectionality is an illusion and occasional big violations make up for the frequent small non-violations (the Brownian ratchet will be subject to internal Brownian forces and therefore will sometimes turn the wrong way).

Inventions and patents

Main article: History of perpetual motion machines

The recorded history of perpetual motion machines dates at least as far back as the 8th century.

- An early description of a perpetual motion machine was by Bhaskara in 1150. He described a wheel that he claimed would run forever.

- Villard de Honnecourt in 1235 described, in a thirty-three page manuscript, a perpetual motion machine of the second kind.

- In the 1760s, James Cox (with the help of John Joseph Merlin) developed a working perpetual motion machine of sorts: a clock (known as Cox's timepiece) powered by changes in atmospheric pressure. Cox was quite open about the workings of his machine, unlike many perpetual motion inventors. The clock still exists today (but was deactivated by the clock's relocation).

- Johann Bessler (also known as Orffyreus) created a series of claimed perpetual motion machines in the 18th Century.

In the 19th century, the invention of perpetual motion machines became an obsession for many scientists. Many machines were designed based on electricity, but none of them lived up to their promises. Other early prospectors in this field included John Gamgee and Cromwell Varley.

- Gamgee developed the Zerometer, a perpetual motion machine of the second kind. Varley, though, did discover in 1867 that an electric generator did not need to be started with a conventional prime mover. He used the Earth's magnetic field to induce enough field strength in the stator windings to get a generator running.

- Other 19th century inventors such as Thomas Henry Moray, an admirer of Nikola Tesla, claimed to be able to tap into radiant energy sources utilizing high frequency high voltage currents interacting with the aether. The energy would be derived from the "running river" of the aether. Several demonstrations by Moray were done where 50 kW of power were generated for several days from an antenna connected to a series of transformers, capacitors, and other components. However, all plans and knowledge were kept secret by Moray, demonstration was not verified, and patents were never granted.

Devising these machines is a favourite pastime of many eccentrics, who often come up with elaborate machines in the style of Rube Goldberg or Heath Robinson. These designs may appear to work on paper at first glance, but have various flaws or obfuscated external power sources that render them useless in practice. This sort of "invention" has become common enough that the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has made an official policy of refusing to grant patents for perpetual motion machines without a working model. One reason for this concern is that a few "inventors" have used official patents to convince gullible potential investors that their machine is "approved" by the Patent Office. The USPTO has granted a few patents for motors that are claimed to run without net energy input. These patents were issued because it was not obvious from the patent that a perpetual motion machine was being claimed. Some of these are:

- Johnson, Howard R., US4151431 "Permanent Magnet Motor", April 24, 1979

- Baker, Daniel, US4074153 "Magnetic propulsion device", February 14, 1978

- Hartman; Emil T., US4215330 "Permanent magnet propulsion system", December 20, 1977 (this device is related to the Simple Magnetic Overunity Toy (SMOT)),

- Flynn; Charles J., US6246561 "Methods for controlling the path of magnetic flux from a permanent magnet and devices incorporating the same", July 31, 1998

- Patrick, et al., US6362718 "Motionless electromagnetic generator" , March 26, 2002

Proponents of perpetual motion machines use a number of other terms to describe their inventions, including "free energy" and "over unity" machines.

Perpetual motion in pop culture

In "The PTA Disbands" episode of The Simpsons, Lisa builds a perpetual motion machine when there was no school due to a teachers' strike; after seeing the machine, her father, Homer observes that, "it just keeps going faster and faster," before yelling at her, "...in this house we obey the laws of thermodynamics!".

In the Playstation 2 video games Xenosaga I & II, and in the Playstation 1 video game Xenogears, the device, called the Zohar, is a form of a perpetual motion machine. It is briefly described as a Pseudo-Perpetual Infinite Energy Engine.

In the computer game The Sims, a complicated (and very expensive) perpetual motion machine can be bought as a household decoration.

See also

- Main: History of perpetual motion machines, Open system, Vacuum energy, Radiant energy, Free energy, Negative resistance, Brownian ratchet, Axletree Dynamo

- Science: Conservation of energy, Thought experiment, Thermodynamic entropy, Second law of thermodynamics, Kirchhoff's law of thermal radiation

- People: George Westinghouse, Josef Hoëné-Wronski, Joseph Newman, John E.W. Keely

- Other: Perpetuum mobile, List of disputed theories

- Science: The N-Machine

References

- Ord-Hume, Arthur W. J. G., "Perpetual Motion: The History of an Obsession". New York, St. Martin's Press. 1977. ISBN 0-312-60131-X

- Bunch, Bryan, and Alexander Hellemans, "The History of Science and Technology: A Browser's Guide to the Great Discoveries, Inventions, and the People Who Made Them from the Dawn of Time to Today". ISBN 0618221239

External links

Manufacturers of purported perpetual motion machines

- French language - Perpetual Motion Machines - Free Energy.

- Lutec Australia - Claims to be manufacturing over unity devices, which are perennially projected to be ready for sale "by the end of the year."

Historic

- Hans-Peter's Mathematick Technick Algorithmick Linguistick Omnium Gatherum

- Eric's History of Perpetual Motion and Free Energy Machines

- The Museum of Unworkable Devices

- Richard Clegg, "Perpetual Motion Page", richardclegg.org.

- A selection of Bhaskara-like devices

- The Bessler Wheel

Research

- "Does Perpetual Motion Exist?". 2003.

- Kevin Kilty's perpetual motion page

- Yahoo Group for discussion of "free energy" machines

- Vlatko Vedral's Lengthy discussion of Maxwell's Demon (PDF)

- Casimir Cones : PPM fueled by entropy.

- Xin Yong Fu and Zi Tao Fu, "Realization of Maxwell's Hypothesis : An Experiment Against the Second Law of Thermodynamics". Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, P.R. China (arXiv.org)

- Cosmic Background Space Drive by John Walker.

Patents

- GB Patent server

- USPTO patent search page