| Revision as of 20:34, 26 June 2012 editMark Arsten (talk | contribs)131,188 edits →Arrest and proselytism: copyedit← Previous edit | Revision as of 20:51, 26 June 2012 edit undoBr'er Rabbit (talk | contribs)8,858 edits ya don't have to go quite this extreme with the encoding ;Next edit → | ||

| Line 109: | Line 109: | ||

| | colwidth = | | colwidth = | ||

| | notes = | | notes = | ||

| {{efn | {{efn | ||

| | name =name | | name = name | ||

| | Other names used by Applewhite include "Guinea", "Tiddly", and "Nincom". {{harv|Urban|2000|p=276}} | | Other names used by Applewhite include "Guinea", "Tiddly", and "Nincom". {{harv|Urban|2000|p=276}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{efn | {{efn | ||

| | name =meetcute | | name = meetcute | ||

| | The circumstances of Applewhite's introduction to Nettles are unclear: their meeting has been variously attributed to his seeking of treatment at a hostpital, {{harv|Lewis|2003|p=111}} visitation of a friend receiving treatment, {{harv|Zeller|2006|p=77}} or teaching of Nettles' son. {{harv|Bearak|1997}} | | The circumstances of Applewhite's introduction to Nettles are unclear: their meeting has been variously attributed to his seeking of treatment at a hostpital, {{harv|Lewis|2003|p=111}} visitation of a friend receiving treatment, {{harv|Zeller|2006|p=77}} or teaching of Nettles' son. {{harv|Bearak|1997}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{ |

{{refs|20em}} | ||

| ==Bibliography== | ==Bibliography== | ||

| '''Books''' | '''Books''' | ||

| *{{cite book | * {{cite book | ||

| |last1=Balch | |last1=Balch | ||

| |first1=Robert W. | |first1=Robert W. | ||

| Line 137: | Line 140: | ||

| |chapter=Making Sense of the Heaven's Gate Sucides | |chapter=Making Sense of the Heaven's Gate Sucides | ||

| |ref={{sfnRef|Balch|Taylor|2002}} | |ref={{sfnRef|Balch|Taylor|2002}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| *{{cite book | * {{cite book | ||

| |last=Chryssides | |last=Chryssides | ||

| |first=George D. | |first=George D. | ||

| Line 149: | Line 152: | ||

| |chapter='Come On Up and I Will Show Thee': Heaven's Gate as a Postmodern Group | |chapter='Come On Up and I Will Show Thee': Heaven's Gate as a Postmodern Group | ||

| |ref={{sfnRef|Chryssides|2005}} | |ref={{sfnRef|Chryssides|2005}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| *{{cite book | * {{cite book | ||

| |last=Goerman | |last=Goerman | ||

| |first=Patricia | |first=Patricia | ||

| Line 160: | Line 163: | ||

| |chapter=Heaven's Gate: The Dawning of a New Religious Movement | |chapter=Heaven's Gate: The Dawning of a New Religious Movement | ||

| |ref={{sfnRef|Goerman|2011}} | |ref={{sfnRef|Goerman|2011}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| *{{cite book | * {{cite book | ||

| |last=Hall | |last=Hall | ||

| |first=John R. | |first=John R. | ||

| Line 170: | Line 173: | ||

| |chapter=Finding Heaven's Gate | |chapter=Finding Heaven's Gate | ||

| |ref={{sfnRef|Hall|2000}} | |ref={{sfnRef|Hall|2000}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| *{{cite book | * {{cite book | ||

| |last=Lalich | |last=Lalich | ||

| |first=Janja | |first=Janja | ||

| Line 179: | Line 182: | ||

| |publisher=] | |publisher=] | ||

| |isbn=978-0-520-24018-6 | |isbn=978-0-520-24018-6 | ||

| |ref={{sfnRef|Lalich |

|ref={{sfnRef|Lalich, .27.27Bounded Choice.27.27|2004}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| *{{cite book | * {{cite book | ||

| |last=Lewis | |last=Lewis | ||

| |first=James R. | |first=James R. | ||

| Line 192: | Line 195: | ||

| |chapter=Legitimating Suicide: Heaven's Gate and New Age Ideology | |chapter=Legitimating Suicide: Heaven's Gate and New Age Ideology | ||

| |ref={{sfnRef|Lewis|2003}} | |ref={{sfnRef|Lewis|2003}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| *{{cite book | * {{cite book | ||

| |last=McCutcheon | |last=McCutcheon | ||

| |first=Russell T. | |first=Russell T. | ||

| Line 202: | Line 205: | ||

| |isbn=978-0-415-27490-6 | |isbn=978-0-415-27490-6 | ||

| |ref={{sfnRef|McCutcheon|2003}} | |ref={{sfnRef|McCutcheon|2003}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| *{{cite book | * {{cite book | ||

| |last=Lifton | |last=Lifton | ||

| |first=Robert Jay | |first=Robert Jay | ||

| Line 212: | Line 215: | ||

| |isbn=978-0-8050-6511-4 | |isbn=978-0-8050-6511-4 | ||

| |ref={{sfnRef|Lifton|2000}} | |ref={{sfnRef|Lifton|2000}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| *{{cite book | * {{cite book | ||

| |last=Partridge | |last=Partridge | ||

| |first=Christopher | |first=Christopher | ||

| Line 224: | Line 227: | ||

| |isbn=978-1-932792-38-6 | |isbn=978-1-932792-38-6 | ||

| |ref={{sfnRef|Partridge|2006}} | |ref={{sfnRef|Partridge|2006}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| *{{cite book | * {{cite book | ||

| |last=Wessinger | |last=Wessinger | ||

| |first=Catherine Lowman | |first=Catherine Lowman | ||

| Line 234: | Line 237: | ||

| |isbn=978-1-889119-24-3 | |isbn=978-1-889119-24-3 | ||

| |ref={{sfnRef|Wessinger|2000}} | |ref={{sfnRef|Wessinger|2000}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| *{{cite book | * {{cite book | ||

| |last=Zeller | |last=Zeller | ||

| |first=Benjamin E. | |first=Benjamin E. | ||

| Line 242: | Line 245: | ||

| |publisher=] | |publisher=] | ||

| |isbn=978-0-8147-9720-4 | |isbn=978-0-8147-9720-4 | ||

| |ref={{sfnRef|Zeller |

|ref={{sfnRef|Zeller, .27.27Prophets and Protons.27.27|2010}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Journals''' | '''Journals''' | ||

| *{{cite journal | * {{cite journal | ||

| |last=Davis | |last=Davis | ||

| |first=Winston | |first=Winston | ||

| Line 257: | Line 260: | ||

| |publisher=] | |publisher=] | ||

| |ref={{sfnRef|Davis|2000}} | |ref={{sfnRef|Davis|2000}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| *{{cite journal | * {{cite journal | ||

| |last=Lalich | |last=Lalich | ||

| |first=Janja | |first=Janja | ||

| Line 269: | Line 272: | ||

| |doi= | |doi= | ||

| |publisher=] | |publisher=] | ||

| |ref={{sfnRef|Lalich |

|ref={{sfnRef|Lalich, "Using the Bounded Choice Model"|2004}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| *{{cite journal | * {{cite journal | ||

| |last=Raine | |last=Raine | ||

| |first=Susan | |first=Susan | ||

| Line 283: | Line 286: | ||

| |publisher=] | |publisher=] | ||

| |ref={{sfnRef|Raine|2005}} | |ref={{sfnRef|Raine|2005}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| *{{cite journal | * {{cite journal | ||

| |last=Urban | |last=Urban | ||

| |first=Hugh | |first=Hugh | ||

| Line 296: | Line 299: | ||

| |publisher=University of California Press | |publisher=University of California Press | ||

| |ref={{sfnRef|Urban|2000}} | |ref={{sfnRef|Urban|2000}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| *{{cite journal | * {{cite journal | ||

| |last=Zeller | |last=Zeller | ||

| |first=Benjamin E. | |first=Benjamin E. | ||

| Line 309: | Line 312: | ||

| |publisher=University of California Press | |publisher=University of California Press | ||

| |ref={{sfnRef|Zeller|2006}} | |ref={{sfnRef|Zeller|2006}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| *{{cite journal | * {{cite journal | ||

| |last=Zeller | |last=Zeller | ||

| |first=Benjamin E. | |first=Benjamin E. | ||

| Line 321: | Line 324: | ||

| |doi=10.1525/nr.2010.14.2.34 | |doi=10.1525/nr.2010.14.2.34 | ||

| |publisher=University of California Press | |publisher=University of California Press | ||

| |ref={{sfnRef|Zeller |

|ref={{sfnRef|Zeller, "Extraterrestrial Biblical Hermeneutics"|2010}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Magazines''' | '''Magazines''' | ||

| *{{cite journal | * {{cite journal | ||

| |last=Dahir | |last=Dahir | ||

| |first=Mubarak | |first=Mubarak | ||

| Line 334: | Line 337: | ||

| |accessdate=June 11, 2012 | |accessdate=June 11, 2012 | ||

| |ref={{sfnRef|Dahir|1997}} | |ref={{sfnRef|Dahir|1997}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| *{{cite journal | * {{cite journal | ||

| |last=Lippert | |last=Lippert | ||

| |first=Barbara | |first=Barbara | ||

| Line 345: | Line 348: | ||

| |accessdate=June 11, 2012 | |accessdate=June 11, 2012 | ||

| |ref={{sfnRef|Lippert|1997}} | |ref={{sfnRef|Lippert|1997}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| *{{cite journal | * {{cite journal | ||

| |last=Miller | |last=Miller | ||

| |first=Mark | |first=Mark | ||

| Line 355: | Line 358: | ||

| |accessdate=June 11, 2012 | |accessdate=June 11, 2012 | ||

| |ref={{sfnRef|Miller|1997}} | |ref={{sfnRef|Miller|1997}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Newspapers''' | '''Newspapers''' | ||

| *{{cite news | * {{cite news | ||

| |title=Heaven's Gate: A Timeline | |title=Heaven's Gate: A Timeline | ||

| |url=http://www.utsandiego.com/uniontrib/20070318/news_lz1n18timelin.html | |url=http://www.utsandiego.com/uniontrib/20070318/news_lz1n18timelin.html | ||

| Line 363: | Line 366: | ||

| |newspaper=] | |newspaper=] | ||

| |date=March 18, 2007 | |date=March 18, 2007 | ||

| |ref={{sfnRef|.27. |

|ref={{sfnRef|.27.27The San Diego Union-Tribune.27.27, "Heaven's Gate: A Timeline"|1997}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| *{{cite news | * {{cite news | ||

| |last=Bearak | |last=Bearak | ||

| |first=Barry | |first=Barry | ||

| Line 374: | Line 377: | ||

| |date=April 28, 1997 | |date=April 28, 1997 | ||

| |ref={{sfnRef|Bearak|1997}} | |ref={{sfnRef|Bearak|1997}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| *{{cite news | * {{cite news | ||

| |last=Jones | |last=Jones | ||

| |first=J. Harry | |first=J. Harry | ||

| Line 384: | Line 387: | ||

| |date=March 18, 2007 | |date=March 18, 2007 | ||

| |ref={{sfnRef|Jones|2007}} | |ref={{sfnRef|Jones|2007}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| *{{cite news | * {{cite news | ||

| |last=Monmaney | |last=Monmaney | ||

| |first=Terence | |first=Terence | ||

| Line 394: | Line 397: | ||

| |date=April 4, 1997 | |date=April 4, 1997 | ||

| |ref={{sfnRef|Monmaney|1997}} | |ref={{sfnRef|Monmaney|1997}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| *{{cite news | * {{cite news | ||

| |last=Steinberg | |last=Steinberg | ||

| |first=Jacques | |first=Jacques | ||

| Line 404: | Line 407: | ||

| |date=March 29, 1997 | |date=March 29, 1997 | ||

| |ref={{sfnRef|Steinberg|1997}} | |ref={{sfnRef|Steinberg|1997}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{Heaven's Gate}} | {{Heaven's Gate}} | ||

Revision as of 20:51, 26 June 2012

Marshall Herff Applewhite (1931 – March 1997; also known as Bo and Do among other names) was an American religious leader who founded what became the Heaven's Gate group and organized their mass suicide in 1997.

A native of Texas, Applewhite attended several universities and served in the military as a young man. He initially hoped to be a minister, but later chose to pursue music as a vocation. After finishing his education, he taught music at the University of Alabama. Several years later, he returned to Texas, where he experienced some career success, leading choruses and serving as the chair of the music department at University of St. Thomas in Houston. He married in the early 1950s, but was unfaithful to his wife in the 1960s; a romance with a young man hindered his teaching career and led to his divorce in 1968. He left the University of St. Thomas in 1970, citing emotional turmoil, and unsuccessfully attempted to start a business. The death of his father a year later brought on severe depression. In 1972, he became a close friend of a nurse, Bonnie Nettles. The two discussed mysticism at length, and concluded that they were called as divine messengers. They unsuccessfully attempted to form a bookstore and teaching center, and began to travel around the United States in 1973. They proclaimed that they were the two witnesses of the Book of Revelation, but only gained one convert. In 1975, Applewhite was arrested after failing to return a rental car, and was jailed for six months. In jail he pondered spiritual matters and further developed his theology.

After Applewhite was released from jail, he traveled to California and Oregon with Nettles. They gained some converts, but were met with critical media coverage and had difficulty retaining followers. In 1976, Applewhite and Nettles gathered their remaining disciples and began to live a strictly regimented nomadic lifestyle. The changes to the group helped ward off further defections. The two leaders taught their followers that they would be visited by extraterrestrials that would provide them with new bodies. Applewhite initially believed that he and his followers would physically ascend, and be transformed into alien bodies. Later, he came to believe that their bodies were mere containers of their souls, which would be placed into new bodies by extraterrestrials. These ideas were expressed with language drawn from Christian eschatology, the New Age movement, and American pop culture.

The group received a large donation in the late 1970s and began to live in rented houses. In 1985, Nettles died, leaving Applewhite distraught. The group kept a very low profile until 1993, when they placed an advertisement that warned of an imminent apocalypse in a national newspaper. Around the same time, they recorded a series of videos that discussed details of their theology. After a stint living in a deserted part of New Mexico in the 1995, the group rented a mansion in California. There they learned of the approach of the Comet Hale–Bopp and that there were rumors that it was accompanied by a spaceship. They believed that this spaceship was the vessel that they had been awaiting, and concluded that it would transport their souls aboard for a journey to another planet. They committed mass suicide in their mansion, believing that their souls would ascend to the spaceship. It was the largest mass suicide to occur inside the U.S., and led to a media circus. In the aftermath, commentators discussed how Applewhite convinced people to follow his commands, including suicide. Some commentators attribute the willingness of his followers to commit suicide to his skill as a manipulator, while others argue that their willingness was due to faith in the narrative that he had constructed.

Early life and education

Marshall Herff Applewhite was born in 1931 to Marshall Herff Applewhite, Sr. and Louise Applewhite; he had three siblings. His father was a minister at a Presbyterian Church, and he became very religious as a child.

Applewhite attended Corpus Christi High School and Austin College. At Austin College, he was active in several student organizations and was moderately religious. He earned a bachelor's degree in philosophy in 1952, and subsequently enrolled at Union Presbyterian Seminary to study theology, hoping to become a minister. He married around that time; he had two daughters. After beginning his seminary studies, he decided to focus on a career in music and left the school. He then became the music director of a Presbyterian Church in North Carolina. He was a baritone singer, and enjoyed spirituals and Handel's music. In 1954, he was drafted by the U.S. Army. He served in Austria and New Mexico as a member of the Army Signal Corps. He left the military in 1956, and enrolled at the University of Colorado, where he earned a master's degree in music.

Career

After finishing his education in Colorado, Applewhite taught at the University of Alabama. He lost his teaching position owing to a sexual relationship he pursued with a male student. His church did not support same-sex relationships, and he was very frustrated by his sexual desires. He separated from his wife in 1965; they divorced three years later.

After leaving the University of Alabama, he moved to Houston, Texas, to teach at the University of St. Thomas, a Catholic institution. He proved to be an engaging, popular teacher and was known for dressing well. He served as chair of the music department; he also became a locally popular singer, and served as the choral director of St. Mark's Episcopal Church in Houston. In Texas, he briefly lived an openly gay lifestyle, but also pursued a relationship with a young woman. The woman left him under pressure from her family, greatly upsetting him. He resigned from the University of St. Thomas in 1970 owing to depression and other emotional problems. The president of the university later recalled that Applewhite was often mentally jumbled and disorganized near the end of his employment there.

In 1971, Applewhite briefly moved to New Mexico, where he operated a deli. He was popular with customers, but decided to return to Texas later that year. His father died around that time; the loss took a significant emotional toll on him, causing severe depression. His debts mounted and he was forced to borrow money from friends.

Introduction to Nettles and first travels

Around that time, he met Bonnie Nettles, a nurse with an interest in Theosophy and biblical prophecy. They quickly became close friends; he later recalled that he felt like he had known her for a long time and concluded that he had met Nettles in a past life. Nettles told him that she had been visited by extraterrestrials that had predicted their meeting, and helped convince him that he had an assignment from God. After leaving the University of St. Thomas, Applewhite had had several visions; in one, he was told that he was chosen for a role like that of Christ. By that time, he had begun to investigate alternatives to traditional Christian doctrine, including astrology.

Applewhite soon began to live with Nettles; although they lived together, their relationship was non-sexual. Applewhite had previously wished he could have a deep and loving, yet non-sexual relationship, and saw Nettles as his soul mate. Nettles was married with two children; after she became close with Applewhite, her husband divorced her and she lost custody of her children. Applewhite permanently broke off contact with his family, as well. Some of his acquaintances later recalled that Nettles had a very strong influence on him. Raine writes that Nettles "was responsible for reinforcing his emerging delusional beliefs", but Lifton speculates that Nettles' influence helped him avoid further psychological breakdowns.

Applewhite and Nettles opened a bookstore known as the Christian Arts Center, which carried books from a variety of spiritual backgrounds. They then launched a venture known as Know Place to teach classes on mysticism and theosophy. Soon, the two friends closed these businesses.

In February 1973, they resolved to travel to teach others about their beliefs, and drove throughout the Southwest and Western U.S. Lifton describes their travels as a "restless, intense, often confused, peripatetic spiritual journey". While traveling, Applewhite and Nettles had little money; they occasionally sold their blood or worked odd jobs for much-needed funds. They sometimes ate only bread rolls, often camped out, and on occasion did not pay their lodging bills. One of their friends from Houston corresponded with them while they traveled, and agreed to accept their teachings. They returned to visit her in May 1974; she was their first convert.

While traveling, they pondered the life of St. Francis of Assisi, and read works by several authors, including Helena Blavatsky, R. D. Laing, and Richard Bach. Applewhite also read science fiction, including works by Robert A. Heinlein and Arthur C. Clarke. The two kept a King James Version of the Bible with them, and studied several passages from the New Testament, focusing on teachings about Christology, asceticism, and eschatology. As they traveled throughout the country, their beliefs began to solidify, and they settled on a basic outline by June 1974. They concluded that they had been chosen to fulfill Biblical prophecies, and that they had been given higher-level minds than other people. They wrote a pamphlet that described Jesus being reincarnated as a Texan, in a thinly veiled reference to Applewhite. Furthermore, they concluded that they were the two witnesses described in the Book of Revelation, and occasionally visited churches or other spiritual groups to speak of their identities, often referring to themselves as "The Two", or the "UFO Two". They believed that they would be killed, but would be restored to life and transported onto a spaceship in view of others. They believed that this would prove their claims, and referred to it as "the Demonstration". Their claims were not accepted by those they met; they were angered by the poor reception they received.

Arrest and proselytism

In August 1974, Applewhite was arrested in Harlingen, Texas, for renting a car in Missouri and failing to return it. He was extradited to St. Louis and jailed for six months. At the time, he maintained that he had been divinely authorized to keep the car. While in prison, he pondered theology and subsequently abandoned discussion of occult topics in favor of extraterrestrials and evolution.

After Applewhite's release, he and Nettles resolved to seek extraterrestrials, and sought like-minded followers. They published advertisements for meetings at which they recruited disciples, or "crew". At the events, they purported to represent beings from another planet, the Next Level, who sought participants for an experiment who would be brought to a higher evolutionary level. The pair then referred to themselves as "Guinea" and "Pig"; Applewhite viewed his role as a "lab instructor", and served as the speaker at their meetings. Their organization was first known as the Anonymous Sexaholics Celibate Church, but soon became known as the Human Individual Metamorphosis.

They sent advertisements to groups in California, and were invited to speak to New Age devotees in Southern California in April 1975. At this meeting, they convinced about half of the 50 attendees to follow them. They also focused on college campuses, speaking at Cañada College in August. They saw further recruitment success at a meeting in Oregon in September 1975. About 30 people left their homes to follow the pair after the event, prompting media coverage. The coverage was very negative: commentators and some former members mocked them and leveled accusations of brainwashing. However, Balch and Taylor state that Applewhite and Nettles eschewed pressure tactics because they sought devoted followers.

Zeller notes that Applewhite and Nettles' teachings had a focus on individual growth as the path to salvation, and sees this as similar to currents in the New Age movement of the early 1970s. Likewise, the importance of personal choice was also emphasized. The two leaders, however, denied connection with the New Age movement, viewing it as a human creation. Lalich attributes Applewhite and Nettle's success in gaining followers to their eclectic mix of beliefs and the way that they deviated from typical New Age teachings: discussing literal spaceships while retaining familiar language. Most of their disciples were young people who were interested in occultism or otherwise lived outside of mainstream society. They came from a variety of religious backgrounds, including Eastern religions and Scientology. Most were well versed in New Age teachings, allowing Applewhite and Nettles to persuade them easily. Applewhite taught that those who believed would reach a higher level of being, and change like a caterpillar becoming a butterfly. This metaphor was used in almost all of their early literature. He contended that this would be a biological change into a different species, casting his teachings as scientific truth in line with secular naturalism. He emphasized to his early followers that he was not talking about a "spiritual trip", and often used the words "biology" and "chemistry" in his statements. By the mid-70s, he attempted to avoid the use of the term "religion", seeing it as inferior to science. Although he dismissed religion as unscientific, he sometimes emphasized the need for faith in the aliens' abilities to transform them.

Nomadic lifestyle

By 1975, Applewhite and Nettles had changed their names to "Bo" and "Peep". After gaining followers, they saw themselves as shepherds tending a flock of sheep. They ceased having public meetings in April 1975, and spent little time teaching doctrine to their converts. Applewhite believed that complete separation from attachment to worldly things was a prerequisite of ascension to the Next Level, and emphasized passages in the New Testament in which Jesus spoke about forsaking worldly attachments. Members were consequently instructed to forsake friends and family, media, drugs, alcohol, jewelry, facial hair, and sexuality. Furthermore, they were required to change their names. Initially, they were instructed to take biblical names, but the two leaders soon told them to adopt two-syllable names that ended in "ody" and had three letters in the first syllable. Applewhite stated that these names were meant to emphasize that his followers were spiritual children. The two leaders and their followers lived what Lewis describes as a "quasi-nomadic lifestyle". They usually stayed at remote campgrounds, and did not speak about their religious views. The leaders had little contact with their dispersed followers, many of whom renounced their allegiance.

He and Nettles feared that they would be assassinated, and taught their followers that their deaths would be similar to those of the two witnesses of the Book of Revelation. Balch and Taylor believe that Applewhite's prison experience and early rejection by audiences contributed to this fear. Applewhite and Nettles later explained to their followers that their treatment by the press was a form of assassination, and stated that this had fulfilled their prophecy. Applewhite took a materialistic view of the bible, seeing it a record of extraterrestrial contact with humanity. Applewhite heavily drew from the Book of Revelation in his construction of doctrine, although he did not use traditional theological terminology. He took a moderately negative tone towards traditional Christianity in his early statements. He only taught about a small number of verses from the book, and never tried to develop a system of theology. Chryssides casts the group as a postmodern organization, citing their focus on finding a personal meaning to fragments of scripture than a comprehensive explanation.

In February 1976, Applewhite and Nettles had settled on the names "Do" and "Ti"; Applewhite stated that these were meaningless names. Applewhite believed in the Ancient astronaut theory, that extraterrestrials had visited humanity in the past and been revered as gods. He taught that extraterrestrials had placed humans on earth, and that they would return to collect a select few humans at a later date. This teaching bears similarities to the Reformed Christian concept of election, likely owing to Applewhite's Presbyterian upbringing. He often spoke about extraterrestrials using phrases from Star Wars and Star Trek, and believed that aliens communicated with him through the shows. In June 1976, they gathered their remaining followers at Medicine Bow National Forest in Southeastern Wyoming, promising a visit from a UFO. Nettles later announced that the visit had been cancelled, and the two leaders split their followers into small groups, which they referred to as "Star Clusters".

In 1975, Applewhite and Nettles had about 70 followers; Lalich states that the group evolved into a cult around that time. From 1976 to 1979 they spent a lot of time camping, usually in the Rocky Mountains or Texas. Their group had previously been loosely structured, but the leaders began to place greater demands on their followers, actions which improved their retention of members. Applewhite insisted that members practice what he referred to as "flexibility", strict obedience to his requests, which were often shifted. He limited the group's contacts with those outside the movement, even some who may have been interested in joining, ostensibly to prevent infiltration. In practice, this made his followers completely dependent upon him. He instructed followers to be like children or pets in their submission—members' sole responsibility was to obey their leaders. Members were encouraged to constantly seek his advice, and to ask themselves what their leaders would do when the leaders were absent. After the group experienced defections in the mid-70s, Applewhite and Nettles increasingly emphasized that they were the only source of truth. The idea that members could receive individual revelations was rejected in an attempt to prevent schisms. Applewhite also sought to prevent close friendships among his followers, fearing that this could lead to insubordination.

To Applewhite's followers, he did not appear to be a dictator; many of them found him laid back and fun to be around. They saw him as having a fatherly appearance. Davis states that Applewhite mastered the "fine art of religious entertainment", noting that many of his followers seemed to enjoy their service. He attempted to express his preferences and nominally offer his disciples a choice rather than issuing direct commands. He emphasized that students were free to disobey if they chose, in what Lalich deems the "illusion of choice".

Housing and control

In the late 1970s, the group received a large sum of money, possibly an inheritance received by a member or donations of members' income. This income was used to rent houses, initially in Denver and later in the Dallas area. They were secretive about their lifestyle, covering the windows of their houses to hide their activities. They had about 40 followers then, and lived in two or three houses: Nettles and Applewhite usually had their own house. The two leaders sought to institute a sort of boot camp to teach their followers how to become a crew that could operate at the Next Level. They referred to their house as a "craft", and regimented the lives of their followers to the minute. The strict lifestyle was intended to cause members to abandon normal aspects of human life, in preparation for life off of Earth. Students who were not committed to this lifestyle were encouraged to leave the group; the two leaders gave financial assistance departing members. Lifton states that Applewhite wanted "quality over quantity" in his followers, although he sometimes dwelt on the idea of gaining large amounts of followers.

Members became desperate for Applewhite's approval, which he used to control them. The two leaders sometimes made sudden, drastic changes to the group. On one occasion in Texas, they told their followers of a forthcoming visitation from extraterrestrials, and had their students wait outside all night before they were told it was merely a test. Lalich sees this as a way that they increased their students' devotion, in that their commitment became irrespective of events around them.

In 1980, the group had about 80 members. Many followers held jobs, working outside the home with computers or as car mechanics. In 1982, Applewhite and Nettles allowed their disciples to call their families. They further relaxed their control in 1983, giving permission to their followers to visit their families on Mother's day. They were only allowed short visits, and were instructed to tell their families that they were studying computers at a monastery. The visits were intended to demonstrate to families that they were there willingly, to prevent conflict. Unlike many cult leaders, Applewhite never clashed with the government.

Nettles' death

In 1983, Nettles had an eye surgically removed, as a result of cancer which she had been diagnosed with several years earlier. She survived for two years following the surgery. After her death in 1985, Applewhite told their followers that she had traveled to the Next Level, abandoning her body to make the journey. He stated that she had too much energy to remain on Earth. His attempt to explain her death was successful—only one member was disconcerted enough by the death to leave. Applewhite, however, became very depressed after her death. He stated that she still communicated with him, but had a crisis of faith. His students supported him during this time, and he was very encouraged by their actions. He also had a wedding ceremony in which he symbolically married his students, possibly as a way to ensure unity after Nettles' death. He told them that he had been left behind because he still had more to learn, and taught that Nettles occupied a higher spiritual role than he did. He began identifying her as "the Father" after her death, and often referred to her as "he".

Applewhite then emphasized a strict hierarchy, and said that the students needed him to guide them, as he was guided by members of the Next Level. Hence, there was no possibility of the group continuing if he were to die. Relationship with Applewhite was said to be the only way to salvation; he encouraged his followers to see him as Christ. Zeller writes that the previous focus on individual choice which had been found in the group was replaced with an emphasis on Applewhite's role as a mediator. They maintained some aspects of their scientific teachings, but in the 1980s, the group became more like a religion in their faith and authority aspects.

Applewhite altered his view of ascension after Nettles' death: he had taught that the group would physically ascend from the earth, but her death forced him to allow that the ascension could be spiritual. He had previously stated that death caused reincarnation. He then concluded that Nettles' spirit had traveled to a spaceship and received a new body, and that he and his followers would do the same. He believed that the biblical heaven was actually a planet on which highly evolved beings dwell, and that physical bodies were required to ascend there. They believed that once they left Earth and reached the Next Level they would facilitate evolution on other planets. Applewhite emphasized that Jesus, whom he believed to be an extraterrestrial, came to Earth, was killed, and then bodily rose from the dead before being transported onto a spaceship. Zeller writes that his beliefs were based upon the Christian bible, but interpreted through the lens of belief in human–extraterrestrial interaction. Applewhite believed that Jesus had found humanity unready to ascend when he first came to the earth; he taught that there was an opportunity for humans to ascend to the Next Level every two millennia. The early 1990s were said to be the first opportunity to reach the Kingdom of Heaven since the time of Jesus.

Applewhite taught that he and his followers were walk-ins, a concept that gained popularity in the New Age movement in the late 1970s. Walk-ins were said to be higher souls who took control of adult bodies to teach humanity. This concept informed Applewhite's concept of resurrection: he believed that once their souls reached a spaceship, they would enter other bodies. This dualism may have also been influenced by that of the Christology that Applewhite had been taught as a young man. Lewis writes that the group's teachings had "Christian elements were basically grafted on to a New Age matrix." He left the metaphor of a butterfly behind, in favor of describing the body as a mere container, a vehicle that souls could enter and exit.

Applewhite became increasingly paranoid after Nettles' death, fearing that his group was targeted by a conspiracy. One member who joined in the mid-80s recalled that Applewhite would avoid new converts, fearing that they were infiltrators. Although he had not initially discussed the Apocalypse at length, he began to speak about it after Nettle's death. He referred to the Apocalypse as the Earth being "spaded under". Although Applewhite utilized a number of New Age concepts, he differed from New Age thinkers by predicting that apocalyptic, rather than utopia-like, changes would soon occur on Earth. He believed that there was an increase in violence occurring, and that this was a signal that the end was near. Applewhite contended that most humans, and world religions, had been brainwashed by Lucifer, but that his followers could break free of this programming. He specifically cited sexual urges as the work of Lucifer. He taught that there were evil extraterrestrials, referred to as "Luciferians", who sought to thwart their plans. He argued that many prominent moral teachers and advocates of political correctness were actually Luciferian aliens. This concept was launched in 1988, possibly in response to the lurid abduction stories that were then proliferating.

Obscurity and evangelism

In the late 1980s, the group took a very low profile; few people knew it still existed. In 1988, the group mailed a document about their beliefs to a variety of New Age organizations. The mailing contained information about the group's history, and advised people to read several books, which primarily focused on Christian history and UFOs. With the exception the 1988 document, Applewhite's group remained inconspicuous until 1992. In 1991 and 1992, they recorded a 12-part video series detailing their beliefs which was broadcast via satellite. These videos echoed many of the teachings of the 1988 update.

Over the course of the group's existence, several hundred people had joined and left the group. In the early 1990s, their membership dwindled, numbering as low as 26. These defections gave Applewhite a sense of urgency. In May 1993, the group took the name "Total Overcomers Anonymous", and spent $30,000 to publish a full-page advertisement in USA Today that warned of catastrophic judgment to befall the Earth. After it was published, about 20 people who had left the group returned. The organization also held a series of public lectures in 1994; these actions caused the group to double in size from its low. By this time, followers' lives were not as strictly regimented as they had been, and he spent less time with them.

In the early 1990s, Applewhite posted some of his teachings on the internet, but was stung by the criticism it generated. Davis speculates that this rejection may have convinced him that it was nearly time for him to leave Earth. That year, he first spoke of the possibility of suicide as a way to reach the Next Level. Applewhite explained that to reach the Next Level everything "human" had to be forsaken, including the human body. As they believed that it would soon be time to ascend, they adopted the name "Heaven's Gate".

From June to October 1995, the group lived in a rural part of New Mexico. They purchased 40 acres (0.16 km) and constructed two structures, and Applewhite hoped to establish a monastery. There they built a compound using tires and lumber, deeming it the "Earth ship". This proved to be a difficult endeavor, particularly for the aging Applewhite. He was in poor health, and at one point, feared that he had cancer. Lifton notes that his highly active lifestyle probably led to severe fatigue late in his life. The winter was very cold, and they abandoned the plan. Afterwards, they lived in several houses in the San Diego area.

The group increasingly focused on the suppression of sexual desire; Applewhite and seven others opted for surgical castration. This may have been intended as a way to demonstrate total commitment to the group. They initially had difficulty finding a surgeon who was willing to perform the operation, but eventually found one in Mexico. Applewhite considered the suppression of sexuality as a key aspect of personal growth. In his view, sexuality was one of the most powerful forces binding individuals to the human body, and thus hindered evolution to the level above human. He taught that members of the Next Level have no reproductive organs. He also cited a part of the New Testament that said there would not be marriage in heaven. He required that members adopt similar dress and haircuts, possibly to reinforce that they were a family, and thus non-sexual.

Final exit

The group rented a mansion in Rancho Santa Fe, California, in October 1996. That year, they recorded two video messages in which they offered their viewers a "last chance to evacuate Earth". That year, they heard of the approach of the Comet Hale–Bopp. Applewhite believed that Nettles was aboard a spaceship trailing the comet and that she had come to rendezvous with the group. He told his followers that the spaceship would transport them to the Kingdom of Heaven. In addition, he stated that deceased followers would be taken up as well, a belief that resembled the Christian pretribulation rapture doctrine. It is not known how he learned of the comet or why he believed that it was accompanied by extraterrestrials. Possible sources include Courtney Brown and Art Bell.

In late March 1997, the group isolated themselves and recorded videos of themselves. Many members praised Applewhite in their final statements; Davis describes their remarks as "regurgitations of Do’s gospel". Applewhite recorded a final video shortly before their deaths in which he termed the suicides their "Final exit", and remarked "We do in all honesty hate this world". He likely decided to commit suicide within a few weeks of the event. Lewis speculates that Applewhite settled on the idea of a suicide because he had taught the group that they would ascend during his lifetime, and thus appointing a successor was unfeasible.

Wessinger posits that the suicides began on March 22. It was the largest group suicide that has taken place inside the United States. Most members took barbiturates and alcohol, and then placed bags over their heads. At the time, they each wore black uniforms with patches that read "Heaven's Gate Away Team" and Nike shoes. There was a bag that contained a few dollars and a form of identification beside each person. The deaths occurred over three days; Applewhite was one of the last four to die. Three assistants helped him commit suicide, before killing themselves. He had taken vicoden in addition to the other substances. His body was found alone, seated on the bed in the master bedroom. An anonymous tip led the sheriff's department to search the mansion. Medical examiners found that Applewhite's fears of cancer were unfounded, but that he suffered from coronary atherosclerosis.

Most of the followers who committed suicide had been members for about 20 years, although there were a few recent converts. Lalich speculates that they were willing to follow Appplewhite in suicide because they had become totally dependent upon him, and hence were poorly suited for life without him.

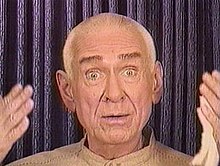

The deaths provoked a media circus; Applewhite's face was featured on the cover of TIME and Newsweek on April 7. His final message was widely broadcast after his death; Urban describes his appearance in this broadcast as "wild-eyed rather alarming".

Analysis

Lalich states that Applewhite "fit the traditional view of a charismatic leader", and Evan Thomas deemed him a "master manipulator". Davis attributes Applewhite's success in convincing his followers to commit suicide to his social isolation of them and cultivation of an attitude of complete religious obedience. Balch and Taylor note that Applewhite's students had committed to his form of thinking in the long term, and state that this explains why his interpretations of events appeared coherent to them. Although many popular commentators, including Margaret Singer, speculated that Applewhite had "brainwashed" his followers, this idea is rejected by most academics.

Lewis argues the Applewhite effectively controlled his followers because he was capable of packaging his teachings in a way that was familiar to his target audience. Richard Hecht of the University of California, Santa Barbara, echoes this sentiment, arguing that his followers committed suicide because they believed in the narrative that he had constructed, rather than being psychologically controlled. Hall posits that the followers were motivated to commit suicide because they saw it as a way to demonstrate that they had conquered the fear of death, and truly believed Applewhite. Chryssides notes that their unique personal interpretations provided them a sense of truth, while appearing strange to outsiders.

Urban writes that Applewhite's life displays "the intense ambivalence and alienation shared by many individuals lost in late twentieth-century capitalist society". He notes that Applewhite's condemnation of contemporary culture bears similarities to those of Jean Baudrillard at times, particularly in regards to their shared nihilist view of society. Urban posits that Applewhite found no way other than suicide to escape the surrounding culture, since he viewed it as completely corrupt. Death offered him a way to escape the "endless circle of seduction and consumption" of society.

After the suicides, several media outlets focused on Applewhite's sexuality; the New York Post deemed Applewhite "the Gay Guru". Troy Perry argued that Applewhite's repression, and society's rejection, of same-sex relationships ultimately led to his suicide. This idea has failed to gain traction among academics. Indeed, Zeller argues that Applewhite's sexuality was not the primary driving force behind his asceticism, which he believes resulted from a variety of factors, though he admits sexuality played a role.

Lifton compares Applewhite to Shoko Asahara, the founder of Aum Shinrikyo, describing him as "equally controlling, his paranoia and megalomania gentler yet ever present". Partridge states that Applewhite and Nettles were similar to John Reeve and Lodowicke Muggleton, who founded Muggletonianism, a millennialist movement in medieval England.

Notes

- Other names used by Applewhite include "Guinea", "Tiddly", and "Nincom". (Urban 2000, p. 276)

- The circumstances of Applewhite's introduction to Nettles are unclear: their meeting has been variously attributed to his seeking of treatment at a hostpital, (Lewis 2003, p. 111) visitation of a friend receiving treatment, (Zeller 2006, p. 77) or teaching of Nettles' son. (Bearak 1997)

References

- ^ Chryssides 2005, p. 355.

- ^ Steinberg 1997.

- Raine 2005, pp. 102–3.

- ^ Davis 2000, p. 244.

- ^ Raine 2005, p. 103.

- ^ Urban 2000, p. 275.

- Hall 2000, p. 150.

- ^ Balch & Taylor 2002, p. 210.

- ^ Raine 2005, p. 107.

- ^ Lewis 2003, p. 111.

- ^ Zeller, "Extraterrestrial Biblical Hermeneutics" 2010, p. 39.

- ^ Zeller 2006, p. 77.

- ^ Bearak 1997.

- ^ Davis 2000, p. 245.

- ^ Urban 2000, p. 276.

- Hall 2000, pp. 150–1.

- Hall 2000, p. 151.

- Lalich, Bounded Choice 2004, pp. 44 & 48. sfn error: no target: CITEREFLalich,_Bounded_Choice2004 (help)

- ^ Lalich, Bounded Choice 2004, p. 43. sfn error: no target: CITEREFLalich,_Bounded_Choice2004 (help)

- ^ Partridge 2006, p. 50.

- ^ Balch & Taylor 2002, p. 211.

- ^ Lifton 2000, p. 306.

- ^ Zeller, "Extraterrestrial Biblical Hermeneutics" 2010, p. 40.

- ^ Hall 2000, p. 152.

- Lalich, Bounded Choice 2004, p. 45. sfn error: no target: CITEREFLalich,_Bounded_Choice2004 (help)

- ^ The San Diego Union-Tribune, "Heaven's Gate: A Timeline" 1997. sfn error: no target: CITEREFThe_San_Diego_Union-Tribune,_"Heaven's_Gate:_A_Timeline"1997 (help)

- Chryssides 2005, pp. 355–6.

- ^ Lalich, "Using the Bounded Choice Model" 2004, pp. 228–9.

- Lifton 2000, p. 308.

- Hall 2000, p. 153.

- Zeller 2006, p. 78.

- ^ Zeller, Prophets and Protons 2010, p. 123. sfn error: no target: CITEREFZeller,_Prophets_and_Protons2010 (help)

- Zeller, "Extraterrestrial Biblical Hermeneutics" 2010, pp. 42–3.

- ^ Chryssides 2005, p. 356.

- Goerman 2011, p. 60.

- ^ Chryssides 2005, p. 357.

- Davis 2000, p. 252.

- Lifton 2000, p. 307.

- Chryssides 2005, pp. 356–7.

- ^ Partridge 2006, p. 51.

- ^ Zeller, Prophets and Protons 2010, p. 129. sfn error: no target: CITEREFZeller,_Prophets_and_Protons2010 (help)

- ^ Lewis 2003, p. 104.

- ^ Balch & Taylor 2002, p. 214.

- ^ Balch & Taylor 2002, p. 213.

- Zeller 2006, p. 82.

- Zeller 2006, p. 83.

- Lalich, Bounded Choice 2004, p. 31. sfn error: no target: CITEREFLalich,_Bounded_Choice2004 (help)

- Lalich, "Using the Bounded Choice Model" 2004, pp. 229–31.

- Lalich, Bounded Choice 2004, p. 64. sfn error: no target: CITEREFLalich,_Bounded_Choice2004 (help)

- ^ Lewis 2003, p. 118.

- ^ Raine 2005, p. 106.

- Zeller, Prophets and Protons 2010, p. 125. sfn error: no target: CITEREFZeller,_Prophets_and_Protons2010 (help)

- ^ Zeller, "Extraterrestrial Biblical Hermeneutics" 2010, p. 41.

- Zeller, Prophets and Protons 2010, p. 117. sfn error: no target: CITEREFZeller,_Prophets_and_Protons2010 (help)

- ^ Zeller, Prophets and Protons 2010, p. 122. sfn error: no target: CITEREFZeller,_Prophets_and_Protons2010 (help)

- Zeller, Prophets and Protons 2010, p. 130. sfn error: no target: CITEREFZeller,_Prophets_and_Protons2010 (help)

- Zeller, Prophets and Protons 2010, p. 127. sfn error: no target: CITEREFZeller,_Prophets_and_Protons2010 (help)

- Zeller, Prophets and Protons 2010, p. 131. sfn error: no target: CITEREFZeller,_Prophets_and_Protons2010 (help)

- Zeller, Prophets and Protons 2010, pp. 133–4 & 136. sfn error: no target: CITEREFZeller,_Prophets_and_Protons2010 (help)

- Wessinger 2000, p. 234.

- Zeller, "Extraterrestrial Biblical Hermeneutics" 2010, p. 45.

- ^ Lalich, "Using the Bounded Choice Model" 2004, pp. 232–5.

- Lewis 2003, p. 114.

- Balch & Taylor 2002, p. 212.

- Balch & Taylor 2002, p. 215.

- Zeller, "Extraterrestrial Biblical Hermeneutics" 2010, pp. 38 & 43.

- ^ Chryssides 2005, pp. 359–62.

- Zeller, Prophets and Protons 2010, p. 124. sfn error: no target: CITEREFZeller,_Prophets_and_Protons2010 (help)

- Zeller, Prophets and Protons 2010, p. 133. sfn error: no target: CITEREFZeller,_Prophets_and_Protons2010 (help)

- ^ Chryssides 2005, p. 365.

- ^ Chryssides 2005, p. 368.

- Lewis 2003, p. 117.

- Partridge 2006, p. 53.

- Lifton 2000, p. 321.

- Lalich, Bounded Choice 2004, p. 63. sfn error: no target: CITEREFLalich,_Bounded_Choice2004 (help)

- Davis 2000, p. 246.

- Davis 2000, p. 255.

- Davis 2000, p. 248.

- ^ Davis 2000, p. 257.

- Davis 2000, p. 251.

- ^ Balch & Taylor 2002, p. 216.

- Zeller 2006, p. 84.

- ^ Balch & Taylor 2002, p. 226.

- Zeller, Prophets and Protons 2010, p. 137. sfn error: no target: CITEREFZeller,_Prophets_and_Protons2010 (help)

- ^ Davis 2000, p. 259.

- Lifton 2000, pp. 309–10.

- Lalich, "Using the Bounded Choice Model" 2004, pp. 233–5.

- Lalich, Bounded Choice 2004, p. 83. sfn error: no target: CITEREFLalich,_Bounded_Choice2004 (help)

- ^ Lewis 2003, p. 112.

- Raine 2005, p. 112.

- Lifton 2000, p. 309.

- Lifton 2000, p. 320.

- Lifton 2000, pp. 308–9.

- Balch & Taylor 2002, pp. 216–7.

- Lalich, Bounded Choice 2004, p. 90. sfn error: no target: CITEREFLalich,_Bounded_Choice2004 (help)

- Zeller 2006, p. 91.

- ^ Chryssides 2005, p. 358.

- ^ Balch & Taylor 2002, p. 217.

- Hall 2000, p. 180.

- ^ Balch & Taylor 2002, p. 218.

- ^ Lalich, Bounded Choice 2004, p. 92. sfn error: no target: CITEREFLalich,_Bounded_Choice2004 (help)

- ^ Partridge 2006, p. 62.

- Lalich, Bounded Choice 2004, p. 78. sfn error: no target: CITEREFLalich,_Bounded_Choice2004 (help)

- ^ Zeller 2006, p. 88.

- Partridge 2006, p. 56.

- Zeller, Prophets and Protons 2010, p. 138. sfn error: no target: CITEREFZeller,_Prophets_and_Protons2010 (help)

- ^ Lewis 2003, p. 113.

- ^ Balch & Taylor 2002, p. 209.

- Zeller, "Extraterrestrial Biblical Hermeneutics" 2010, p. 44.

- Wessinger 2000, p. 233.

- ^ Lewis 2003, p. 106.

- Zeller, Prophets and Protons 2010, p. 126. sfn error: no target: CITEREFZeller,_Prophets_and_Protons2010 (help)

- Zeller, "Extraterrestrial Biblical Hermeneutics" 2010, p. 35.

- Chryssides 2005, p. 363.

- Lewis 2003, pp. 114–6.

- Partridge 2006, p. 59.

- Zeller, Prophets and Protons 2010, p. 141. sfn error: no target: CITEREFZeller,_Prophets_and_Protons2010 (help)

- ^ Miller 1997.

- Zeller 2006, pp. 85–6.

- Goerman 2011, p. 61.

- ^ Partridge 2006, p. 55.

- Raine 2005, p. 114.

- Raine 2005, p. 108.

- Davis 2000, p. 250.

- ^ Balch & Taylor 2002, p. 219.

- Zeller, Prophets and Protons 2010, p. 143. sfn error: no target: CITEREFZeller,_Prophets_and_Protons2010 (help)

- Lalich, Bounded Choice 2004, p. 102. sfn error: no target: CITEREFLalich,_Bounded_Choice2004 (help)

- Zeller 2006, p. 89.

- Zeller, Prophets and Protons 2010, p. 149. sfn error: no target: CITEREFZeller,_Prophets_and_Protons2010 (help)

- Zeller, Prophets and Protons 2010, p. 150. sfn error: no target: CITEREFZeller,_Prophets_and_Protons2010 (help)

- ^ Lalich, Bounded Choice 2004, p. 42. sfn error: no target: CITEREFLalich,_Bounded_Choice2004 (help)

- ^ Balch & Taylor 2002, p. 220.

- Lalich, Bounded Choice 2004, p. 95. sfn error: no target: CITEREFLalich,_Bounded_Choice2004 (help)

- Davis 2000, p. 260.

- Wessinger 2000, p. 238.

- Zeller 2006, p. 87.

- ^ Raine 2005, p. 113.

- Balch & Taylor 2002, p. 221.

- ^ Lifton 2000, p. 311.

- Raine 2005, p. 111.

- Lifton 2000, p. 305.

- ^ Jones 2007.

- Lewis 2003, p. 110.

- Urban 2000, p. 286.

- Zeller, Prophets and Protons 2010, p. 145. sfn error: no target: CITEREFZeller,_Prophets_and_Protons2010 (help)

- Wessinger 2000, p. 239.

- Raine 2005, pp. 109–110.

- Zeller 2006, p. 86.

- Partridge 2006, p. 60.

- Partridge 2006, p. 61.

- Balch & Taylor 2002, p. 223.

- Lalich, Bounded Choice 2004, p. 98. sfn error: no target: CITEREFLalich,_Bounded_Choice2004 (help)

- Davis 2000, p. 243.

- Urban 2000, p. 279.

- Lewis 2003, pp. 112–3.

- Wessinger 2000, p. 230.

- Wessinger 2000, p. 229.

- ^ Lalich, Bounded Choice 2004, p. 27. sfn error: no target: CITEREFLalich,_Bounded_Choice2004 (help)

- Balch & Taylor 2002, p. 224.

- Hall 2000, p. 175.

- ^ Lalich, Bounded Choice 2004, p. 28. sfn error: no target: CITEREFLalich,_Bounded_Choice2004 (help)

- Lalich, "Using the Bounded Choice Model" 2004, pp. 237–9.

- Lalich, Bounded Choice 2004, p. 30. sfn error: no target: CITEREFLalich,_Bounded_Choice2004 (help)

- McCutcheon 2003, pp. 104–5.

- Goerman 2011, p. 58.

- Davis 2000, p. 242.

- Balch & Taylor 2002, p. 227.

- ^ Monmaney 1997.

- Davis 2000, p. 241.

- Lewis 2003, p. 126.

- Hall 2000, p. 181.

- Urban 2000, p. 270.

- Urban 2000, pp. 291–2.

- Urban 2000, p. 271.

- ^ Dahir 1997, pp. 35–7.

- Lippert 1997, p. 31.

Bibliography

Books

- Balch, Robert W.; Taylor, David (2002). "Making Sense of the Heaven's Gate Sucides". In David G. Bromley and J. Gordon Melton (ed.). Cults, Religion, and Violence. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66898-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Chryssides, George D. (2005). "'Come On Up and I Will Show Thee': Heaven's Gate as a Postmodern Group". In James R. Lewis and Jesper Aagaard Petersen (ed.). Controversial New Religions. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-515682-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Goerman, Patricia (2011). "Heaven's Gate: The Dawning of a New Religious Movement". In George D. Chryssides (ed.). Heaven's Gate: Postmodernity and Popular Culture in a Suicide Group. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-6374-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Hall, John R. (2000). "Finding Heaven's Gate". Apocalypse Observed: Religious Movements, and Violence in North America, Europe, and Japan. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-19276-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Lalich, Janja (2004). Bounded Choice: True Believers and Charismatic Cults. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24018-6.

- Lewis, James R. (2003). "Legitimating Suicide: Heaven's Gate and New Age Ideology". In Christopher Partridge (ed.). UFO Religions. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-26324-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - McCutcheon, Russell T. (2003). The Discipline of Religion: Structure, Meaning, Rhetoric. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-27490-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Lifton, Robert Jay (2000). Destroying the World to Save it: Aum Shinrikyō, Apocalyptic Violence, and the New Global Terrorism. Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8050-6511-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Partridge, Christopher (2006). "The Eschatology of Heaven's Gate". Expecting the End: Millennialism in Social And Historical Context. Baylor University Press. ISBN 978-1-932792-38-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Wessinger, Catherine Lowman (2000). How the millennium comes violently: from Jonestown to Heaven's Gate. Seven Bridges Press. ISBN 978-1-889119-24-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Zeller, Benjamin E. (2010). Prophets and Protons: New Religious Movements and Science in Late Twentieth-Century America. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-9720-4.

Journals

- Davis, Winston (2000). "Heaven's Gate: A Study of Religious Obedience". Nova Religio. 3 (2). University of California Press: 241–267. doi:10.1525/nr.2000.3.2.241.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Lalich, Janja (2004). "Using the Bounded Choice Model as an Analytical Tool: A Case Study of Heaven's Gate". Cultic Studies Review. 3 (3). International Cultic Studies Association: 226–247.

- Raine, Susan (2005). "Reconceptualising the Human Body: Heaven's Gate and the Quest for Divine Transformation". Religion. 35 (2). Elsevier: 98–117. doi:10.1016/j.religion.2005.06.003.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Urban, Hugh (2000). "The Devil at Heaven's Gate: Rethinking the Study of Religion in the Age of Cyber-Space". Nova Religio. 3 (2). University of California Press: 268–302. doi:10.1525/nr.2000.3.2.268.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Zeller, Benjamin E. (2006). "Scaling Heaven's Gate: Individualism and Salvation in a New Religious Movement". Nova Religio. 10 (2). University of California Press: 75–102. doi:10.1525/nr.2006.10.2.75.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Zeller, Benjamin E. (2010). "Extraterrestrial Biblical Hermeneutics and the Making of Heaven's Gate". Nova Religio. 14 (2). University of California Press: 34–60. doi:10.1525/nr.2010.14.2.34.

Magazines

- Dahir, Mubarak (May 13, 1997). "Heaven's Scapegoat". The Advocate: 35–7. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Lippert, Barbara (April 14, 1997). "Cult Fiction". New York: 30–3. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Miller, Mark (April 13, 1997). "Secrets Of The Cult". Newsweek. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

Newspapers

- "Heaven's Gate: A Timeline". The San Diego Union-Tribune. March 18, 2007. Retrieved June 10, 2012.

- Bearak, Barry (April 28, 1997). "Eyes on Glory: Pied Pipers of Heaven's Gate". The New York Times. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Jones, J. Harry (March 18, 2007). "Heaven's Gate Revisited". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved June 10, 2012.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Monmaney, Terence (April 4, 1997). "Free Will, or Thought Control?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 15, 2012.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Steinberg, Jacques (March 29, 1997). "From Religious Childhood To Reins of a U.F.O. Cult". The New York Times. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

| Heaven's Gate | |

|---|---|

| Leadership | |

| Background | |

| Researchers | |

| Media | |

- Apocalypticists

- Heaven's Gate

- People from Houston, Texas

- Self-declared messiahs

- Founders of religions

- Castrated people

- Suicides in California

- Suicides by poison

- 1931 births

- 1997 deaths

- Thieves

- American stage actors

- United States Army soldiers

- Austin College alumni

- American music educators

- University of Colorado alumni

- University of Alabama faculty