| Revision as of 17:47, 13 January 2013 view sourceWehwalt (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators152,661 edits →Final two terms: say where Clay was from← Previous edit | Revision as of 17:53, 13 January 2013 view source Khazar2 (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers191,299 edits →Secession crisis: ce for concisionNext edit → | ||

| Line 162: | Line 162: | ||

| Johnson hoped that he would be a compromise candidate for the 1860 presidential nomination as the Democratic Party tore itself apart over the slavery question. Busy with the Homestead Bill during the ] in ], he sent two of his sons and his chief political adviser to represent his interest in the backroom dealmaking. The convention deadlocked, with no candidate able to gain the required two-thirds vote, but the sides were too far apart to consider Johnson as a compromise. The party split, with northerners backing Illinois Senator ] while southerners, including Johnson, supported Vice President Breckinridge for president. With former Tennessee senator ] running a fourth-party candidacy and further dividing the vote, the Republican Party elected its first president, former Illinois representative ]. ], known to be against slavery, was unacceptable to many in the South. Although secession from the Union had not been an issue in the election, talk of it began in the southern states.{{sfn|Trefousse|pp=123–127}}{{sfn|Gordon-Reed|pp=60–63}} | Johnson hoped that he would be a compromise candidate for the 1860 presidential nomination as the Democratic Party tore itself apart over the slavery question. Busy with the Homestead Bill during the ] in ], he sent two of his sons and his chief political adviser to represent his interest in the backroom dealmaking. The convention deadlocked, with no candidate able to gain the required two-thirds vote, but the sides were too far apart to consider Johnson as a compromise. The party split, with northerners backing Illinois Senator ] while southerners, including Johnson, supported Vice President Breckinridge for president. With former Tennessee senator ] running a fourth-party candidacy and further dividing the vote, the Republican Party elected its first president, former Illinois representative ]. ], known to be against slavery, was unacceptable to many in the South. Although secession from the Union had not been an issue in the election, talk of it began in the southern states.{{sfn|Trefousse|pp=123–127}}{{sfn|Gordon-Reed|pp=60–63}} | ||

| Johnson took to the Senate floor after the election |

Johnson took to the Senate floor after the election, giving a speech well received in the North, "I will not give up this government ... No;<!-- punct as in original --> I intend to stand by it ... and I invite every man who is a patriot to ... rally around the altar of our common country ... and swear by our God, and all that is sacred and holy, that the Constitution shall be saved, and the Union preserved."{{sfn|Trefousse|p=131}}{{sfn|Johnson|pp=172–173}} As southern senators announced they would resign if their states seceded, Johnson reminded Mississippi Senator ] that if southerners would only hold to their seats, the Democrats would control the Senate, and could defend the South's interests against any infringement by Lincoln.{{sfn|Trefousse|p=134}} Gordon-Reed points out that while Johnson's belief in a Union which could not be dissolved was undoubtedly sincere, Johnson had alienated southern leaders, including Davis, who would soon be ] of the ], formed by the seceding states. If Johnson backed the Confederacy and became one of its legislators, he would have small influence in its halls of power.{{sfn|Gordon-Reed|p=64}} With few Republicans in the state, Lincoln looked to Johnson for help in deciding who would receive federal appointments in Tennessee.{{sfn|Trefousse|p=138}} | ||

| Johnson returned home when his state took up the issue of secession. Johnson's successor as governor, ], and the legislature, decided to have a referendum on whether to have a constitutional convention to authorize secession, and when that failed, put the question of leaving the Union to a popular vote. Despite threats on Johnson's life, and actual assaults, Johnson campaigned against both questions, sometimes speaking with a gun on the lectern before him. Although Johnson's ] was against secession, the second referendum passed with support from parts further west, and in June 1861, Tennessee joined the Confederacy. Finally convinced he would be killed if he remained, the senator fled the state through ], where his party was fired upon; he left his wife and family in Greeneville.{{sfn|Castel|p=8}}{{sfn|Trefousse|pp=138–143}} | Johnson returned home when his state took up the issue of secession. Johnson's successor as governor, ], and the legislature, decided to have a referendum on whether to have a constitutional convention to authorize secession, and when that failed, put the question of leaving the Union to a popular vote. Despite threats on Johnson's life, and actual assaults, Johnson campaigned against both questions, sometimes speaking with a gun on the lectern before him. Although Johnson's ] was against secession, the second referendum passed with support from parts further west, and in June 1861, Tennessee joined the Confederacy. Finally convinced he would be killed if he remained, the senator fled the state through ], where his party was fired upon; he left his wife and family in Greeneville.{{sfn|Castel|p=8}}{{sfn|Trefousse|pp=138–143}} | ||

Revision as of 17:53, 13 January 2013

This article is about the President of the United States. For other uses, see Andrew Johnson (disambiguation).

| Andrew Johnson | |

|---|---|

| |

| 17th President of the United States | |

| In office April 15, 1865 – March 4, 1869 | |

| Vice President | Vacant |

| Preceded by | Abraham Lincoln |

| Succeeded by | Ulysses S. Grant |

| 16th Vice President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1865 – April 15, 1865 | |

| President | Abraham Lincoln |

| Preceded by | Hannibal Hamlin |

| Succeeded by | Schuyler Colfax |

| United States Senator from Tennessee | |

| In office March 4, 1875 – July 31, 1875 | |

| Preceded by | William Brownlow |

| Succeeded by | David Key |

| In office October 8, 1857 – March 4, 1862 | |

| Preceded by | James C. Jones |

| Succeeded by | David Patterson |

| Military Governor of Tennessee | |

| In office March 12, 1862 – March 4, 1865 | |

| Appointed by | Abraham Lincoln |

| Preceded by | Isham G. Harris (As Governor of Tennessee) |

| Succeeded by | William Gannaway Brownlow (As Governor of Tennessee) |

| 15th Governor of Tennessee | |

| In office October 17, 1853 – November 3, 1857 | |

| Preceded by | William B. Campbell |

| Succeeded by | Isham G. Harris |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Tennessee's 1st district | |

| In office March 4, 1843 – March 3, 1853 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas Arnold |

| Succeeded by | Brookins Campbell |

| Personal details | |

| Born | (1808-12-29)December 29, 1808 Raleigh, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Died | July 31, 1875(1875-07-31) (aged 66) Elizabethton, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Resting place | Andrew Johnson National Cemetery Greeneville, Tennessee |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Other political affiliations | National Union (1864–1868) |

| Spouse(s) | Eliza McCardle (1827-1875; survived as widow) |

| Children | Martha Charles Mary Robert Andrew |

| Profession | Tailor |

| Signature | |

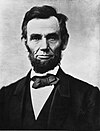

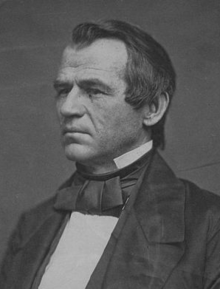

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808 – July 31, 1875) was the 17th President of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. As Abraham Lincoln's vice president, Johnson became president when Lincoln was assassinated. A Democrat who ran with Lincoln on the National Union ticket, Johnson came to office as the Civil War concluded. The new president favored quick restoration of the seceded states to the Union. His plans did not give protection to the former slaves, and he came into conflict with the Republican-dominated Congress, culminating in his impeachment by the House of Representatives. The first American president to be impeached, he was acquitted by the Senate by one vote.

Johnson, born in poverty, became a master tailor. He served as alderman and mayor of Greeneville, Tennessee before being elected to the Tennessee House of Representatives in 1835. After brief service in the Tennessee Senate, Johnson was elected to the House of Representatives in 1843, where he served five two-year terms. He became Governor of Tennessee for four years, and was elected by the legislature to the Senate in 1857. In his congressional service, he sought passage of the Homestead Bill, which was enacted soon after he left his Senate seat in 1862.

As southern states, including Tennessee, seceded to form the Confederate States of America, Johnson remained firmly with the Union. In 1862, Lincoln appointed him as military governor of Tennessee, much of which had been retaken. In 1864, Johnson, as a War Democrat and Southern Unionist, was a logical choice as running mate for Lincoln, and was selected; their ticket easily won. Johnson was sworn in as vice president in March 1865, giving a rambling and possibly drunken speech, and he secluded himself to avoid public ridicule. Six weeks later, the assassination of Lincoln made him president.

Johnson implemented his own form of Presidential Reconstruction – a series of proclamations directing the seceded states to hold conventions and elections to re-form their civil governments. When southern states returned many of their old leaders, and passed Black Codes to deprive the freedmen of many civil liberties, Congress refused to seat legislators from those states and advanced legislation to overrule the southern actions. Johnson vetoed the bills, and Congress overrode him, setting a pattern for the remainder of his presidency. As the conflict between the branches of government grew, Congress passed the Tenure of Office Act, restricting Johnson in firing Cabinet officials. When he persisted in trying to dismiss Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, he was impeached by the House of Representatives, and narrowly avoided conviction and removal from office in the Senate. Returning to Tennessee after his presidency, Johnson sought political vindication, and gained it in his eyes when he was elected to the Senate again in 1875 (the only past president to serve there), only months before his death. Although Johnson's ranking has fluctuated over time, he is presently considered among the worst American presidents for his opposition to federally guaranteed rights for African-Americans.

Early life and career

Boyhood

Andrew Johnson was born in Raleigh, North Carolina on December 29, 1808, to Jacob Johnson (1778–1812) and Mary ("Polly") McDonough (1783–1856), a laundress. He had a brother William four years his elder and an older sister Elizabeth, who died in childhood. The future president was born in a log cabin—a natal characteristic which in the 19th century was a potent symbol of political virtue and simplicity. Jacob Johnson was a poor man, as was his father William. Jacob Johnson became town constable of Raleigh, married and started a family. He died of an apparent heart attack while ringing the town bell, shortly after rescuing three drowning men, leaving his family in poverty when Andrew was three. Polly Johnson had worked as a washerwoman; she continued in that trade as the sole support of her children. At the time, her occupation, which often took her into others' homes unaccompanied, was considered less than respectable: the Johnsons were considered white trash, and there were rumors that Andrew, who did not resemble his siblings, was fathered by another man. Eventually, Polly Johnson married Turner Doughtry, who was also poor.

Living in poverty, Andrew Johnson, like his childhood friends, was an object of ridicule from members of higher social circles. He and his peers were acutely aware that they were one step above the lowest on the socio-economic ladder, that is, the black slaves. As a consequence, Johnson assumed an attitude of white supremacy, which he kept throughout his life.

Polly Doughtry apprenticed her elder son, William, first to Thomas Henderson (one of the men whom Jacob Johnson had saved) and then to a tailor, James Selby. Andrew followed his brother as an apprentice in Selby's shop at the age of ten; he was legally bound to serve until his 21st birthday. Selby does not appear to have had any great influence on the future president. One of his employees was detailed to teach the boy rudimentary literacy skills, and he was boarded with his mother for part of his service. Andrew Johnson, however, gained a lifelong love of learning at Selby's shop, as citizens came to read to the tailors from books, and the boy frequented the shop to listen even before he was apprenticed there. His biographer, Annette Gordon-Reed, suggests that Johnson, who would be acclaimed as a public speaker, learned the basics of that art as he threaded needles and cut cloth.

Andrew Johnson was not happy at James Selby's, and at about age 15, ran away with his brother. Selby responded by placing an advertisement in the paper, as customary for masters seeking missing apprentices, "Ten Dollars Reward. Ran away from the subscriber, two apprentice boys, legally bound, named William and Andrew Johnson ... to any person who will deliver said apprentices to me in Raleigh, or I will give the above reward for Andrew Johnson alone." The future president was described as having "a dark complexion, black hair, eyes, and habits". The boys went to Carthage, North Carolina, where Andrew worked as a tailor for several months. Fearing he would be taken and returned to Raleigh, Andrew Johnson moved on to Laurens, South Carolina for two years, where Andrew found work in his craft. There he met his first love, Mary Wood, for whom he made a quilt. After his marriage proposal to her was rejected, he returned to Raleigh, hoping to buy out his apprenticeship. However, he could not come to terms with Selby, and, like many others in the late 1820s, journeyed west.

Move to Tennessee

Johnson left North Carolina for Tennessee, traveling mostly on foot. After a brief period in Knoxville, he moved to Mooresville, Alabama, where Joseph Sloss taught him how to make frock coats. He then worked as a tailor in Columbia, Tennessee, where he might have remained, but was called back to Raleigh by his mother and stepfather, who saw limited opportunities there and who wished to emigrate west. Some of Polly Doughtry's relatives were living in eastern Tennessee, as was William Johnson. Andrew Johnson and the Doughtrys traveled through the Blue Ridge Mountains to Greeneville, Tennessee, a town with which Andrew Johnson fell in love at first sight. Later, when he became prosperous, he purchased the land there where he had first camped and planted a tree in commemoration.

In Greenville, Johnson established a successful tailoring business in the front of his home; he was joined by a partner, Hentle W. Adkinson. In 1827, at the age of 18, Johnson married 16-year-old Eliza McCardle, the daughter of a local shoemaker. The couple were married for almost 50 years and had five children: Martha (1828), Charles (1830), Mary (1832), Robert (1834), and Andrew Jr. (1852). Though she suffered from consumption, Eliza supported Johnson's endeavors. She taught her husband arithmetic up to basic algebra and tutored him to improve his literacy, reading, and writing skills. Shy and retiring by nature, Eliza Johnson did not accompany her husband on his later political tours, leading to rumors, which he always denied, that he was unfaithful to her. She was often not seen during her husband's presidency; their daughter Martha usually served as official hostess.

The Johnson tailor shop prospered during the early years of the marriage, enabling Andrew Johnson to hire help and giving him the funds to invest profitably in real estate. He later boasted of his talents as tailor, "my work never ripped or gave way." He was a voracious reader. Books about famous orators aroused Johnson's interest in political dialogue, and he had private debates with customers with opposing views on issues of the day. Johnson initiated public debates by organizing a debating society with Blackston McDannel, the local plasterer and a customer. He also took part in debates at Greeneville College.

Political rise

Tennessee politician

Johnson helped organize a mechanics' (working men's) ticket in the 1829 Greeneville municipal election. He was elected town alderman, along with his friends McDannel and Mordecai Lincoln—the first cousin to Thomas Lincoln, father of the future president, had, as justice of the peace, married the Johnsons. In 1831, Andrew Johnson became a member of the 90th Regiment of the Tennessee militia. Following the 1831 Nat Turner slave rebellion, a state convention was called to pass a new constitution, including provisions to disfranchise free people of color. The convention also wanted to reform real estate tax rates, and provide ways of funding improvements to Tennessee's infrastructure. The constitution was submitted for a public vote and Johnson spoke widely for its adoption; the successful campaign provided him with additional positive statewide exposure. On January 4, 1834, his fellow alderman elected him mayor of Greeneville.

In 1835, Johnson made a bid for election to the "floater" seat which Greene County shared with neighboring Washington County, in the Tennessee House of Representatives. According to his biographer, Hans Trefousse, Johnson "demolished" the opposition in debate and won the election with almost a two to one margin. Neither the Democratic nor the newly formed Whig party was then well organized in that part of Tennessee. Soon after taking his seat, Johnson purchased his first slave, Dolly, aged 14. He soon bought Dolly's half-brother, Sam; Dolly had three children over the years. Johnson had the reputation of treating his slaves kindly, but the fact that Dolly was dark-skinned, and her offspring much lighter, has led to speculation both during and after his lifetime that Johnson was the father.

In his first term in the state house, Johnson did not consistently ally himself with either party, though he revered President Andrew Jackson, a Democrat and Tennessean. The party system was then in a state of flux, and the major parties were still determining their core values and policy proposals. Johnson often voted with the Whig Party, which had arisen in opposition to Jackson, fearing the concentration of power in the Executive Branch of the government. He broke with the Whigs on the question of government spending and support for the railroads, while his constituents looked forward to improvements in transportation infrastructure. As a result, after serving a single term, he was defeated for re-election in 1837. Defeated by Brookins Campbell in the legislative election, Johnson would not lose another race for thirty years. In 1839, Johnson sought to regain his seat, initially as a Whig, but when another candidate sought the Whig nomination, Johnson ran as a Democrat and was elected to his second, non-consecutive, term in the Tennessee House. From that time he supported the Democratic party and built a powerful political machine in Greene County. Johnson supported President Martin Van Buren, also a Democrat, who had succeeded Jackson. Johnson became a powerful advocate of the Democratic Party, noted for his oratory, and in an era when public speaking both informed the public and entertained it, people flocked to hear him.

In 1840, Johnson was selected as a presidential elector for Tennessee, giving him more statewide exposure. Despite Van Buren's defeat by former Ohio senator William Henry Harrison, Johnson was instrumental in keeping Tennessee and Greene County in the Democratic column. He was elected to the Tennessee Senate in 1841, where he served one two-year term.

After a promotion in the militia in 1841, Johnson was often locally referred to as "Colonel". He had achieved financial success in his tailoring business, which he sold in order to concentrate on politics. He had also acquired additional real estate, including a larger home and a farm where his mother and stepfather took residence, as well as securing ownership of as many as eight or nine slaves.

Congressman (1843–1853)

First three terms

In 1843, Johnson was the first Democrat to gain election as a U.S. representative from Tennessee's 1st congressional district, and joined a new Democratic majority in the House of Representatives. In his first term in the House, he articulated his own brand of Jeffersonian–Jacksonian principles which he would steadfastly promote throughout most of his political career. Johnson advocated for the interests of the poor, maintained an anti-abolitionist stance, insisted on limited spending by the government and opposed protective tariffs. While these positions were well suited for most of his local constituency, they were less so on a national level. When not on the House floor, Johnson, in Washington without his wife Eliza, shunned social functions in favor of study and reading in the Library of Congress. Although a fellow Tennessee Democrat, James K. Polk, was elected president in 1844, and Johnson had campaigned for him, the two men had difficult relations, and as Johnson steered an independent course in Congress, President Polk came to refuse some of Johnson's patronage suggestions.

Johnson believed, as did many southern Democrats, that as the Constitution protected private property, of which slaves were a form, neither federal nor state governments could abolish it. In one of his first speeches on the floor, he stated,

The black race of Africa are inferior to the white man in point of intellect—better calculated in physical structure to undergo drudgery and hardship—standing, as they do, many degrees lower in the scale of gradation that expresses the relative relation between God and all that he has created than the white man.

Johnson won a second Congressional term in 1845 against his perennial opponent, Wiliam G. Brownlow; in this second campaign, Johnson particularly took up the mantle as defender of the poor against the aristocracy. He also expressed his outrage at accusations made against his father. Once re-elected, Johnson supported the Polk administration's decisions to fight the Mexican War, which was seen by some northerners as an attempt to gain territory to expand slavery westward. Johnson supported the war, and opposed the Wilmot Proviso, a proposal which would have banned slavery in any territory gained from Mexico. Beginning in his second term, promoted a measure requiring the turnover of all government jobs every eight years. In his second term, he introduced for the first time his Homestead Bill, which sought to provide 160 acres for every poor family head "without money and without price". This issue was especially important to Johnson because of his own humble beginnings.

Johnson's third term in Congress found him stiffening in his opposition to non-essential government spending, from expenses of the new Smithsonian Institute to the purchase of portraits for the Executive Mansion (later the White House). In the presidential election in 1848, the Democrats split over the slavery issue, with abolitionists leaving the party and forming the Free Soil Party, and making former president Van Buren their nominee. Johnson supported the Democratic candidate, former Michigan senator Lewis Cass, who thought it up to the people in each state to decide on the issue. With the party split, Whig nominee General Zachary Taylor was easily victorious, and carried Tennessee as well. Johnson's relations with Polk remained poor; the President recorded of his final New Year's reception in 1849 that

Among the visitors I observed in the crowd today was Hon. Andrew Johnson of the Ho. Repts. Though he represents a Democratic District in Tennessee (my own State) this is the first time I have seen him during the present session of Congress. Professing to be a Democrat, he has been politically, if not personally hostile to me during my whole term. He is very vindictive and perverse in his temper and conduct. If he had the manliness and independence to declare his opposition openly, he knows he could not be elected by his constituents. I am not aware that I have ever given him cause for offense.

Johnson, in the face of the national interest in new railroad construction, and in response to the need in his own district for additional means of transportation, changed his position. Thereafter, he supported funding to the state to assist the expansion of the East Tennessee and Virginia Railroad. During this term Johnson also made a concerted effort to increase his sphere of interactions; his higher profile was exemplified by a biographical sketch published in The New York Times in May 1849, describing him as an excellent committee worker and investigator. Johnson also purchased a newspaper named the Greeneville Spy.

Final two terms

In the campaign for election to his fourth term in August 1849, Johnson concentrated on three issues: slavery, homesteads and judicial elections. He defeated his opponent, Nathaniel G. Taylor, with a greater margin of victory than in previous campaigns. When the House convened in December 1849, the party division caused by the Free Soil Party precluded the formation of the majority needed to elect a Speaker. Johnson proposed adoption of a rule allowing election of a Speaker by a plurality; some weeks later others took up a similar proposal, and Democrat Howell Cobb was elected.

The difficulty in electing a Speaker commenced a contentious session of Congress, as the issue of slavery took front stage. The proposed admission to the union of California, which banned slavery in its constitution, set off a debate as to whether a prohibition of slavery should be made a condition of admission. Kentucky's Henry Clay introduced in the Senate a series of resolutions, the Compromise of 1850, which admitted California, a deal sweetened by enacting legislation sought by each side. Johnson voted for each of the provisions with the exception of its abolition of slavery in the nation's capital. He pressed resolutions for constitutional amendments to provide for popular election of senators (then elected by state legislatures) and of the president (chosen by the Electoral College), and limiting the tenure of federal judges to 12 years. These were all defeated.

A group of Democrats who opposed him nominated Landon Carter Haynes as Johnson's rival for a fifth term. The campaign included fierce debates; Johnson's main issue was the passage of the Homestead Bill, which Haynes contended would facilitate abolition. Johnson won the election by over 1600 votes. Though he was not enamored of the party's presidential nominee, former New Hampshire senator Franklin Pierce, Johnson campaigned for him. Pierce was elected, but he failed to carry Tennessee. In 1852 Johnson managed to get the House to pass his Homestead Bill, but it failed in the Senate. The Whigs had gained control of the Tennessee legislature, and redrew Johnson's First District under the leadership of Gustavus Adolphus Henry, Sr. to make it a safe seat for their party; the Nashville Union termed this "Henry-mandering". Lamented Johnson, "I have no political future."

Governor of Tennessee (1853–1857)

If Johnson considered retiring from politics upon deciding not to seek re-election, he soon changed his mind. When it became apparent that Johnson would not be able to be re-elected, an effort began by his ally, George W. Jones, to put forward Johnson's name for governor. The Democratic convention unanimously nominated him, though some Democrats were not happy at Johnson's selection. The Whigs had won the past two gubernatorial elections, and still controlled the legislature. The Whigs nominated their "Eagle Orator", Gustavus Henry, making the "Henry-mandering" of the First District an immediate issue. Henry attacked Johnson for his voting record in denying pay increases to federal troops. The two men debated in county seats the length of Tennessee before the meetings were called off two weeks before the August election due to the illness of Henry's family members. Johnson won the election by 2,250 votes, some of which were cast in return for his promise to support Whig Nathaniel Taylor for his old seat in Congress.

Tennessee's governor had little power—Johnson could propose legislation but not veto it, and most appointments were made by the Whig-controlled legislature. Nevertheless, it was a bully pulpit which allowed him to publicize himself and his political views. Johnson succeeded in getting the bank appointments he wanted, in return for his endorsement of John Bell, a Whig, for one of the state's U.S. Senate seats. In his first biennial speech, he urged simplification of the state judicial system, abolishment of the Bank of Tennessee and establishment of an agency to provide uniformity in weights and measures, the last of which was passed. Johnson was critical of the Tennessee common school system and suggested funding be increased via taxes, either statewide or county by county—a mixture of the two was passed.

Although the Whig Party was on its final decline nationally, it remained strong in Tennessee, and the outlook for Democrats there in 1855 was poor. Johnson agreed to run for re-election for governor that year anyway. Re-election as governor was necessary to give him a chance at the higher office he was ambitious for. Meredith P. Gentry received the Whig nomination. A series of more than a dozen debates ensued, where the exchanges grew increasingly vitriolic. The issues in the campaign were slavery, the prohibition of alcohol, and the Know Nothing Party. Johnson favored the first, but opposed the other two. Gentry was more equivocal on the alcohol question, and had gained the support of the Know Nothings, a group Johnson deemed a secret society. Johnson was surprisingly victorious, albeit with a narrower margin.

When the presidential election of 1856 approached, Johnson and supporters harbored a vague hope for the presidency, and he gave a speech to the Tennessee Democratic delegates reiterating his views; some county conventions designated him a favorite son, and the Nashville Union and American proposed his nomination. Johnson's position that the best interests of the Union were served by slavery in some areas made him a practical compromise candidate for president. The Tennessee delegation was split, and Johnson was never a major contender; the nomination fell to former Pennsylvania senator James Buchanan. Though he was not impressed by either, Johnson campaigned for the ticket of Buchanan and former Kentucky representative John C. Breckenridge, which was elected.

Johnson decided not to seek a third term as governor, with an eye towards election to the United States Senate. In 1857, while returning from Washington, Johnson's train derailed, causing serious damage to his right arm which would plague him in the future.

United States Senator

Homestead Bill advocate

The victors in the 1857 state legislative campaign would, once they convened in October, elect a United States Senator. Former Whig governor William B. Campbell wrote to his uncle, "The great anxiety of the Whigs is to elect a majority in the legislature so as to defeat Andrew Johnson for senator. Should the Democrats have the majority, he will certainly be their choice, and there is no man living to whom the Americans and Whigs have as much antipathy as Johnson." Johnson, still governor, spoke widely in the campaign. Though his party won the governor's race and control of the legislature, Johnson still had to overcome considerable opposition from the conservatives in both parties. His final biennial speech as governor was pivotal, and he made proposals which would be popular among Democrats. Two days later the legislature elected the outgoing governor to the Senate. The opposition was appalled, with the Richmond Whig referring to him as "the vilest radical and most unscrupulous demagogue in the Union."

Johnson gained high office due to his proven record as a man popular among the small farmers and self-employed tradesmen who made up much of Tennessee's electorate. Johnson called them the "plebians"; he was less popular among the planters and lawyers who led the Democratic Party in Tennessee, but none could match him as a vote-getter. Always seen in impeccably-tailored clothing, Johnson cut an impressive figure, and had the stamina to endure lengthy campaigns with daily travel over bad roads leading to another speech or debate. Mostly denied the party's machinery, he relied on a network of friends, advisers, and contacts. One friend, Hugh Douglas, wrote to him, "you have been in the way of our would be great men for a long time. At heart many of us never wanted you to be Governor only none of the rest of us Could have been elected at the time and we only wanted to use you. Then we did not want you to to go to the Senate but the people would send you." After his death, one Tennessee voter wrote of him, "Johnson was always the same to everyone ... the honors heaped upon him did not make him forget to be kind to the humblest citizen."

The new senator took his seat when Congress convened in December 1857 (the term of his predecessor, James C. Jones, had expired in March). He came to Washington as usual without his wife and family; Eliza would visit Washington only once during Johnson's first time as senator, in 1860. Johnson immediately set about introducing the Homestead Bill in the Senate, but as most senators who supported it were northern (many associated with the newly-founded Republican Party), the matter became caught up in suspicions over the slavery issue. Southern senators felt that those who took advantage of the provisions of the Homestead Bill were more likely to be northern non-slaveholders. This would place slaveholders at a disadvantage in popular votes to approve a territorial constitution, although the issue of slavery had been complicated by the Supreme Court's ruling earlier in the year in Dred Scott v. Sandford that slavery could not be prohibited in the territories. Johnson, a slaveholding senator from a southern state, made a major speech in the Senate the following May in an attempt to convince his colleagues that the Homestead Bill and slavery were not incompatible. Nevertheless, southern opposition was key to defeating the Homestead Bill, 30–22. In 1859, the bill failed on a tied procedural vote, broken against the bill by Vice President Breckinridge, and in 1860, a watered-down version passed both houses, only to be vetoed by Buchanan at the urging of southerners. Johnson joked during the protracted battle over the Homestead Bill, "if the Ten Commandments were to come up for consideration, somebody would find a Negro in there somewhere, and the slavery question would be raised".

As chairman of the Committee to Audit and Control the Contingent Expense, Johnson continued his relentless opposition to spending, especially when the capital city was the beneficiary; he argued it was unfair to expect taxpayers in the states to fund the infrastructure of another locality, even if it was the seat of government. He opposed spending money for troops to put down the revolt by the Mormons in Utah Territory, arguing for temporary volunteers as the United States should not have a standing army.

Secession crisis

In October 1859, abolitionist John Brown and sympathizers raided the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (today West Virginia). Tensions in Washington between pro- and anti-slavery forces increased greatly. Both to boost his own presidential chances and in an attempt to gain support for the Homestead Bill, Johnson gave a major speech on the question of slavery. He addressed the Senate in December, decrying northerners who would endanger the Union by seeking to outlaw slavery. The Tennessee senator stated that the phrase in the Declaration of Independence, "all men are created equal", did not apply to African-Americans, since the Constitution of Illinois contained that phrase—and that document barred voting by African-Americans.

Johnson hoped that he would be a compromise candidate for the 1860 presidential nomination as the Democratic Party tore itself apart over the slavery question. Busy with the Homestead Bill during the 1860 Democratic National Convention in Charleston, South Carolina, he sent two of his sons and his chief political adviser to represent his interest in the backroom dealmaking. The convention deadlocked, with no candidate able to gain the required two-thirds vote, but the sides were too far apart to consider Johnson as a compromise. The party split, with northerners backing Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas while southerners, including Johnson, supported Vice President Breckinridge for president. With former Tennessee senator John Bell running a fourth-party candidacy and further dividing the vote, the Republican Party elected its first president, former Illinois representative Abraham Lincoln. The election of Lincoln, known to be against slavery, was unacceptable to many in the South. Although secession from the Union had not been an issue in the election, talk of it began in the southern states.

Johnson took to the Senate floor after the election, giving a speech well received in the North, "I will not give up this government ... No; I intend to stand by it ... and I invite every man who is a patriot to ... rally around the altar of our common country ... and swear by our God, and all that is sacred and holy, that the Constitution shall be saved, and the Union preserved." As southern senators announced they would resign if their states seceded, Johnson reminded Mississippi Senator Jefferson Davis that if southerners would only hold to their seats, the Democrats would control the Senate, and could defend the South's interests against any infringement by Lincoln. Gordon-Reed points out that while Johnson's belief in a Union which could not be dissolved was undoubtedly sincere, Johnson had alienated southern leaders, including Davis, who would soon be the president of the Confederate States of America, formed by the seceding states. If Johnson backed the Confederacy and became one of its legislators, he would have small influence in its halls of power. With few Republicans in the state, Lincoln looked to Johnson for help in deciding who would receive federal appointments in Tennessee.

Johnson returned home when his state took up the issue of secession. Johnson's successor as governor, Isham G. Harris, and the legislature, decided to have a referendum on whether to have a constitutional convention to authorize secession, and when that failed, put the question of leaving the Union to a popular vote. Despite threats on Johnson's life, and actual assaults, Johnson campaigned against both questions, sometimes speaking with a gun on the lectern before him. Although Johnson's eastern region of Tennessee was against secession, the second referendum passed with support from parts further west, and in June 1861, Tennessee joined the Confederacy. Finally convinced he would be killed if he remained, the senator fled the state through Cumberland Gap, where his party was fired upon; he left his wife and family in Greeneville.

The only member from a seceded state to remain in the Senate, as the most prominent southern Unionist, he had Lincoln's ear in the early months of the war. With most of Tennessee in Confederate hands, Johnson spent congressional recesses in Kentucky and Ohio, trying in vain to convince any Union commander who would listen to conduct an operation into East Tennessee. Johnson was named to the Joint Committee on Conduct of the War; its purpose was to goad on laggard Union generals. Johnson, to no avail, used this platform to voice the urgency of military intervention in East Tennessee.

Military Governor of Tennessee

Johnson's first tenure in the Senate came to a conclusion in March 1862 when Lincoln appointed him military governor of Tennessee. Much of the central and western portions of that seceded state had been recovered. Although some argued that civil government should simply resume once the Confederates were put down in an area, Lincoln chose to use his power as commander in chief to appoint military governors in areas which had been in revolt. With the Confederates having confiscated his land, his slaves taken away, and his home made into a military hospital, Johnson made the final comments of his first time in the Senate: "I am a Democrat now, I have been one all my life; I expect to live and die one, and the corner-stone of my Democracy rests upon the enduring basis of the Union." The Senate quickly confirmed his nomination along with the rank of brigadier general. Later in 1862, after Johnson's departure from the Senate and in the absence of most southern legislators, the Homestead Act was finally enacted; it, along with legislation for land grant colleges and for the transcontinental railroad, has been credited with opening the American West to settlement.

As military governor, he sought to eliminate Confederate influences in the state, demanding loyalty oaths from public officials, and shutting down newspapers run by sympathizers. At that time, much of eastern Tennessee remained in Confederate hands, and the ebb and tide of war through 1862 sometimes brought rebel control close to Nashville. The Confederates did allow Eliza Johnson and their family to pass through the lines to him. The city was continually harassed with cavalry raids conducted by Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest, while Johnson undertook as best he could the defense of the city. Relief from Union regulars did not come until Gen. William S. Rosecrans replaced Buell and stopped the Confederates at Murfreesboro at the start of 1863. Much of eastern Tennessee was retaken later that year.

When Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863, freeing the slaves in rebel-controlled areas, he exempted Tennessee at Johnson's request. Nevertheless, Lincoln's action increased the debate over what should happen to the slaves after the war—not all Unionists supported abolition. Johnson decided that slavery had to end, stating, "If the institution of slavery ... seeks to overthrow it , then the Government has a clear right to destroy it". He reluctantly supported efforts to recruit former slaves for the Union Army, feeling it more appropriate that African-Americans should perform menial tasks and free up whites to fight. Nevertheless, Johnson succeeded in enlisting 20,000 black troops for the Union.

Vice President

In 1860, Lincoln's running mate had been Maine Senator Hannibal Hamlin. Nevertheless, Johnson took that position for Lincoln's re-election bid in 1864. How this came to pass was disputed, with the point at issue whether or not Lincoln caused the convention to select Johnson. Lincoln's secretaries and biographers, John Hay and John Nicolay, believed that Lincoln did not choose his running mate, based on a telegram Hay sent to Nicolay in 1864, stating that the President was not involving himself in the decision. The opposite school of thought, that Lincoln caused the selection of Johnson, was championed by Alexander McClure, who had helped get Lincoln the nomination in 1860, and who stated shortly after Hamlin's death in 1891 that Lincoln had caused Johnson's selection. Several of Lincoln's friends stated that the President had expressed a preference for Johnson as his running mate. According to historian Albert Castel in his account of Johnson's presidency, Lincoln was impressed by Johnson's administration of Tennessee.

It is known that Lincoln gave some consideration to putting a War Democrat on the ticket in 1864, and sent an agent to sound out General Benjamin Butler as a possible running mate. In May 1864, the President sent General Daniel Sickles to Nashville on a fact-finding mission. Although Sickles denied he was there either to investigate or interview the governor, Johnson biographer Hans L. Trefousse believes Sickles's trip was connected to Johnson's subsequent nomination as vice president. Gordon-Reed points out that while the Lincoln-Hamlin ticket might have been considered geographically balanced in 1860, "having Johnson, the southern War Democrat, on the ticket sent the right message about the folly of secession and the continuing capacity for union within the country." Another factor was the desire of Secretary of State William Seward to frustrate the vice-presidential candidacy of his fellow New Yorker, former senator and War Democrat Daniel S. Dickinson, as Seward would probably have had to yield his place with another New Yorker as vice president. Johnson, once he was told by reporters the likely purpose of Sickles' visit, was active on his own behalf, giving speeches and having his political friends work behind the scenes to boost his candidacy. To add to the theme of unity, Lincoln in 1864 ran under the banner of the National Union Party, rather than the Republicans.

At the party's convention in Baltimore in June, Lincoln was easily nominated, although there had been some talk of replacing him with a Cabinet officer or one of the more successful generals. After the convention backed Lincoln, former Secretary of War Simon Cameron offered a resolution to nominate Hamlin, but it was defeated. Johnson was nominated for vice president by C.M. Allen of Indiana with an Iowa delegate as seconder. On the first ballot, Johnson led with 200 votes to 150 for Hamlin and 108 for Dickinson. On the second ballot, Kentucky switched to vote for Johnson, beginning a stampede. Johnson was named on the second ballot with 491 votes to Hamlin's 17 and eight for Dickinson; the nomination was made unanimous. Lincoln expressed pleasure at the result, "Andy Johnson, I think, is a good man." When word reached Nashville, a crowd assembled and Johnson obliged with a speech contending his selection as a southerner meant that the rebel states had not in fact left the Union, which was indivisible.

Although it was unusual at the time for a national candidate to actively campaign, Johnson gave a number of speeches in Tennessee, Kentucky, Ohio, and Indiana. He also sought to boost his chances in Tennessee while advancing the establishment of civil government by making the loyalty oath even more restrictive, in that voters would now have to swear they opposed making a settlement with the Confederacy. The Democratic candidate for president, George McClellan, hoped to avoid additional bloodshed by negotiation, and so this effectively disenfranchised Democrats who were not minded to vote for the Lincoln/Johnson ticket. Lincoln refused to override Johnson, and their ticket took the state by 25,000 votes. Congress refused to count Tennessee's electoral votes because of the irregularities, but Lincoln and Johnson did not need them, having won in most states which voted, and easily secured the election.

Now Vice President-elect, Johnson was anxious to complete the work of re-establishing civilian government, although the election for a new governor could not take place until after Inauguration Day, March 4. Johnson hoped to remain in Nashville to complete his task, but was told by Lincoln's advisers that he could not stay, but would be sworn in with Lincoln. In these months, Union troops finished the retaking of eastern Tennessee, including Greeneville. Just before his departure, the voters of Tennessee ratified a new constitution, abolishing slavery, on February 22, 1865. One of Johnson's final acts as military governor was to certify the results.

Johnson duly traveled to Washington to be sworn in, although according to Gordon-Reed, "in light of what happened on March 4, 1865, it might have been better if Johnson had stayed in Nashville." He may have been ill; Castel cited typhoid fever, though Gordon-Reed notes that there is no independent evidence for that diagnosis. On the evening of March 3, Johnson attended a party in his honor, at which he drank heavily. Hung over the following morning at the Capitol, he asked Vice President Hamlin for some whiskey. Hamlin produced a bottle, from which Johnson took two stiff drinks, stating "I need all the strength for the occasion I can have." In the Senate Chamber, Johnson delivered a rambling address as Lincoln, the Congress, and dignitaries looked on. Almost incoherent at times, Johnson finally meandered to a halt, whereupon Hamlin hastily swore him in as vice president. Lincoln, who had watched sadly during the debacle, was sworn in, and delivered his acclaimed Second Inaugural Address.

In the weeks after the inauguration, Johnson only presided over the Senate briefly, instead hiding from public ridicule at the Maryland home of a friend, Francis Preston Blair. When he did return to Washington, it was with the intent of leaving for Tennessee to re-establish his family in Greeneville. Instead, he remained after word came that General Ulysses S. Grant had captured the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, presaging the end of the war. Lincoln stated, in response to criticism of Johnson's behavior, that "I have known Andy Johnson for many years; he made a bad slip the other day, but you need not be scared; Andy ain't a drunkard."

Presidency 1865–1869

Accession

Main article: Assassination of Abraham LincolnOn the afternoon of April 14, 1865, Lincoln and Johnson met for the first time since the inauguration. What they discussed is unclear—Trefousse states that Johnson wanted to "induce Lincoln not to be too lenient with traitors", with which Gordon-Reed agrees. Castel, on the other hand, stated that the topic of discussion is not known.

On April 14, 1865, President Lincoln was shot and mortally wounded by John Wilkes Booth, a Confederate sympathizer, who conspired to cause the assassinations of others, including Johnson, Ulysses S. Grant and Secretary of State William H. Seward that same night. Seward narrowly survived his wounds, while Johnson escaped attack as his would-be assassin, George Atzerodt, failed to go through with the plan. Leonard J. Farwell, a fellow boarder at the Kirkwood House, awoke Johnson with news of Lincoln's having been shot at Ford's Theater. Johnson rushed to the President's deathbed, where he remained a short time, on his return commenting, "They shall suffer for this. They shall suffer for this." Lincoln died at 7:22 am the next morning; Johnson's swearing in occurred between 10 and 11 am with Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase presiding in the presence of most of the Cabinet. Johnson's demeanor was described by the newspapers as "solemn and dignified" and "his bearing produced a most gratifying impression upon those who participated." Some Cabinet members had last seen Johnson, apparently drunk, at the inauguration. At noon, Johnson conducted his first cabinet meeting in the Treasury Secretary's office, asked all members to remain in their positions, and directed the appropriate members to initiate Lincoln's funeral arrangements. William Hunter was appointed acting Secretary of State for the wounded Seward.

The events of the assassination resulted, then and subsequently, in speculation concerning Johnson and what the conspirators may have intended for him. Johnson's would-be assassin, Atzerodt, got drunk instead of killing the vice president. In the vain hope of having his life spared, after his capture, Atzerodt spoke much about the conspiracy, but did not say anything to indicate that the that the plotted assassination of Johnson was merely a ruse. One fact pointed to by conspiracy theorists is that on the day of the shooting of Lincoln, Booth came to the Kirkwood House and left one of his cards, which was received by Johnson's private secretary, William A. Browning, with a note reading, "Are you at home? Don't wish to disturb you. J. Wilkes Booth." After Johnson's conflict as president with Congress became embittered, stories were told that Johnson had been awakened while disheveled and apparently drunk, to be told the news that Lincoln had been shot, and was in such a condition that he could not be seen publicly until late the next day. According to Trefousse, "the falsity of these assertions is evident."

Johnson's initial statements and actions in the government transition stressed his proven record and sought to reassure his audience that he could carry on the government as before. He presided with dignity over Lincoln's funeral ceremonies in Washington, before the leader's body was sent home to Springfield, Illinois for burial. Shortly after Lincoln's death, Union General William T. Sherman reported he had, without consulting Washington, reached an armistice agreement with Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston, which surrendered Confederate forces in North Carolina in exchange for the existing state government remaining in power, with private property rights to be respected. This did not even acknowledge the freedom of those in slavery, and was not acceptable to Johnson or the Cabinet. Johnson sent word for Sherman to secure the surrender without making political deals, which occurred. This action, together his placing a $100,000 bounty on the head of Confederate President Davis, then a fugitive, gave him the reputation of a man who would be tough on the South, as northern political opinion demanded. More controversially, he permitted the execution of Mary Surratt, the only woman convicted as a member of the conspiracy to assassinate Lincoln. Johnson refused to consider clemency, and Surratt was executed with three others, including Atzerodt, on July 7, 1865.

Reconstruction

Main article: Reconstruction era of the United StatesBackground

Upon taking office, Johnson faced the question of what to do with the retaken southern states. Lincoln had authorized loyalist governments in Virginia, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Tennessee as the Union came to control large parts of those states. President Lincoln had advocated a ten percent plan whereby when that percentage of the voters in a state took an oath of future loyalty, elections could be held and he would recognize the results. Congress was reluctant to allow these governments; its own plan requiring a majority of voters to take the loyalty oath for a state to be admitted passed both houses in 1864, but Lincoln pocket vetoed it.

Johnson's goals in accomplishing the reconstruction of the southern states to the Union were three. He sought a speedy restoration of the states, on the ground that they had never truly left the Union, and thus should again be recognized once loyal citizens formed a government. African-American suffrage was a delay and a distraction; it had always been a state responsibility to decide who should vote. Second, political power in the southern states should pass from the planter class to Johnson's beloved "plebians", small farmers and self-employed tradesmen. Since many African-Americans were still economically bound to their former masters, and might vote at their direction, their suffrage again was an impediment to Johnson's goals. Johnson's third priority was election in his own right in 1868, a feat no man who had succeeded a deceased president had yet managed to accomplish. He was as yet uncertain as to what party banner to run under: it was widely expected that the Republican Party, which began as a disparate coalition united by the slavery issue, might dissolve into its component elements. The Democrats, on the other hand, were weak in the North, and their southern base was not then voting.

The Republicans had not broken apart, but had formed a number of factions. The Radical Republicans sought voting and other civil rights for African-Americans. They believed that the freedmen could be induced to vote Republican in gratitude for emancipation, and that black votes could keep the Republicans in power and southern Democrats, including former rebels, out of influence. They believed that top Confederates should be punished. The Moderate Republicans sought to keep the Democrats out of power at a national level, and prevent former rebels from holding positions of power in the South. They were not as enthusiastic about the idea of African-American suffrage as their Radical colleagues, due either to their own local political concerns, or feeling that the freedman would be likely to cast his vote badly. Northern Democrats favored the unconditional restoration of the southern states. They did not support African-American suffrage, as that race's votes might threaten Democratic control in the South.

Presidential Reconstruction

Johnson was initially left to devise a Reconstruction policy without legislative intervention, as Congress was not scheduled to meet again until December 1865. Radical Republicans told the President that the Southern states were economically in a state of chaos and urged him to use his leverage to insist on rights for freedmen as a condition of restoration to the Union. But Johnson, with the support of other officials including Seward, insisted that the franchise was a state, not a federal matter. The Cabinet was divided on the issue.

Johnson's first Reconstruction actions were two proclamations, with the unanimous backing of his Cabinet, on May 29. One recognized the Virginia government led by Governor Francis Pierpont. The second provided amnesty for all insurgents except those holding property valued at $20,000 or more; it also appointed a provisional governor for North Carolina and authorized elections. Neither of these proclamations included provisions regarding black suffrage or freedmen's rights. The President gave permission for constitutional conventions in other Southern states.

As southern states began the process of forming again their governments, Johnson received considerable public support for his policies, and took it as unconditional backing for quick reinstatement of the South. While he received such support from the South, he underestimated the determination of northerners to ensure that the war had not been fought for nothing. It was important, in northern public opinion, that the South acknowledge its defeat, that slavery be ended, and that the lot of African-Americans be improved. Voting rights were less important—after all, only a handful of northern states (mostly in New England) gave African-American men the right to vote on the same basis as whites, and in late 1865, Connecticut, Wisconsin, and Minnesota voted down African-American suffrage proposals by large margins. Public opinion tolerated Johnson's leniency as an experiment, to be allowed if it brought southern acceptance of defeat. Instead, southerners were emboldened. A number of southern states passed Black Codes, which bound African-American laborers to farms on annual contracts they could not quit, and allowed law enforcement at whim to arrest them for vagrancy and rent out their labor. Most southerners elected to Congress were former Confederates, with the delegations headed by Georgia Senator-designate and former Confederate vice president Alexander Stephens. Congress assembled in early December 1865; Johnson's conciliatory annual message to them was well received. Nevertheless, Congress refused to seat the southern legislators and established a committee to recommend appropriate Reconstruction legislation.

Northerners were outraged at the idea of unrepentant members of the Confederate government, such as Stephens, lawmaking at a time when emotional wounds from the war were raw. They saw the Black Codes placing African-Americans in a position barely above slavery. Restoration of the southern states would likely bring the Democrats close to control of Congress: increased representation for the South as slaves were liberated by the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment in December 1865 and thus were no longer counted as three-fifths of a human being for representation purposes, and a successful 1866 election might bring them to full control of Congress. If that happened, and if Johnson favored the Democrats, the Republicans would be effectively out of government. In addition, according to David O. Stewart in his book on Johnson's impeachment, "the violence and poverty that oppressed the South would galvanize the opposition to Johnson".

Break with the Republicans: 1866

Congess was reluctant to confront the President, and initially only sought to fine-tune Johnson's policies towards the South. According to Trefousse, "If there was a time when Johnson could have come to an agreement with the moderates of the Republican Party, it was the period following the return of Congress ..." Johnson was unhappy about the provocative actions of the southern states, and of the continued control by the antebellum elite there, but made no statement publicly, believing that southerners had a right to act as they did, even if it was unwise to do so. By late January 1866, he was convinced that winning a showdown with the Radical Republicans was necessary to his political plans, both short term for Reconstruction and for re-election in 1868. He would have preferred that the conflict be over the legislative efforts to enfranchise African-Americans in the District of Columbia, which had been defeated overwhelmingly in an all-white referendum. A bill to accomplish this passed the House of Representatives, but to Johnson's disappointment, stalled in the Senate before he could veto it.

Illinois Senator Lyman Trumbull, leader of the Moderate Republicans and Chairman of the Judiciary Committee, was anxious to reach a compromise with the President. He ushered through the Congress a bill extending the Freedman's Bureau beyond its scheduled abolition in 1867, and the first Civil Rights Bill, which sought to grant citizenship to the freedmen. Trumbull met several times with Johnson, and was convinced the President would sign the measures. Johnson rarely contradicted visitors, which often fooled those who met with him into thinking he was in accord. The President opposed both bills as infringements on state sovereignty. Additionally, both of Trumbull's bills were unpopular among white southerners, whom Johnson hoped to include in his new party. The President vetoed the Freedman's Bureau bill on February 18, 1866, to the delight of white southerners, and to the puzzled anger of Republican legislators. Johnson considered himself vindicated when the a move to override his veto failed in the Senate the following day. Johnson believed that the Radicals would now be isolated and defeated, and that the Moderate Republicans would form behind him. However, he did not understand that Moderates too wanted to see African-Americans treated fairly.

On February 22, Washington's Birthday, Johnson gave an impromptu speech to supporters who had marched to the Executive Mansion (as the White House was still formally known) and called for an address in honor of the first president. In his hour-long speech, he instead referred to himself over 200 times. More damagingly, he also spoke of "men ... still opposed to the Union" to whom he could not extend the hand of friendship he gave to the South. When called upon by the crowd to say who they were, Johnson named Pennsylvania Congressman Thaddeus Stevens, Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, and abolitionist Wendell Phillips, and accused them of plotting his assassination. Republicans viewed the address as a declaration of war, while one Democratic ally estimated Johnson's speech cost the party 200,000 votes in the 1866 congressional midterm elections.

Although strongly urged by Moderates in Congress to sign the civil rights bill, Johnson broke decisively with them by vetoing it on March 27. In his veto message, he objected to the measure because it conferred citizenship on the freedmen at a time when 11 out of 36 states were unrepresented in the Congress, and that it discriminated in favor of African-Americans and against whites. Johnson said it was an invasion by federal authority of the rights of the states, it had no warrant in the Constitution and was contrary to all precedents. It was a "stride toward centralization and the concentration of all legislative power in the national government." Within three weeks, Congress had overridden his veto, the first time that had been done in American history.

The veto of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 is often seen as a key mistake of Johnson's presidency, which convinced Moderates there was no hope of working with him. Historian Eric Foner in his volume on Reconstruction views it as "the most disastrous miscalculation of his political career". According to Stewart, the veto was "for many defining blunder, setting a tone of perpetual confrontation with Congress that prevailed for the rest of his presidency".

One means by which Congress bypassed Johnson was the Fourteenth Amendment, also written by Trumbull. It was proposed to the states by Congress in a constitutional process in which the president has no part, though Johnson opposed it. The amendment was designed to put the key provisions of the Civil Rights Act into the Constitution, but it went further. It extended citizenship to every person born in the United States (except Indians on reservations), penalized states that did not give the vote to freedmen, and most importantly, created new federal civil rights that could be protected by federal courts. It also guaranteed the federal war debt and voided all Confederate war debts. Further, it disqualified many former Confederates from office, although the disability could be removed—by Congress, not the president. Both houses passed the Freedmen's Bureau Act a second time, and again the president vetoed it; this time, the veto was overridden. By the summer of 1866, when Congress finally adjourned, Johnson's method of restoring states to the Union by executive fiat, without safeguards for the freedmen, was in deep trouble. His home state of Tennessee ratified the Fourteenth Amendment despite the President's opposition. When Tennessee did so, Congress immediately seated its proposed delegation, embarrassing Johnson.

Efforts to compromise failed, and a political war ensued between the united Republicans on one side, and on the other, Johnson and his allies in the Democratic Party, North and South. He called a convention of the National Union Party, which he nominally headed. Republicans had resumed their own banner; Johnson intended to use the name to unite his supporters and gain re-election. The battle was the election of 1866, in which the southern states were not allowed to vote. Johnson campaigned vigorously, undertaking a public speaking tour of the north, known as the "Swing Around the Circle". The trip, including speeches in Chicago, St. Louis, Indianapolis and Columbus, proved politically disastrous, with Johnson making controversial comparisons between himself and Christ, and engaging in arguments with hecklers which were criticized as undignified. The Republicans won by a landslide, increasing their two-thirds majority in Congress, and made plans to control Reconstruction. Johnson blamed the Democrats for giving only lukewarm support to the National Union movement.

Radical Reconstruction

Even with the Republican victory in November 1866, Johnson considered himself in a strong position. The Fourteenth Amendment had been ratified by none of the southern or border states except Tennessee, and had been rejected in Kentucky, Delaware, and Maryland. As the amendment required three quarters of the states to ratify it for it to become part of the Constitution, Johnson believed the deadlock would be broken in his favor, leading to his re-election in 1868. Once it reconvened in December 1866, an energized Congress began passing legislation, often over Johnson's veto; this included the District of Columbia voting bill and statehood for Nebraska. The Republicans gained two senators and a state which promptly ratified the amendment. Johnson's veto of a bill for statehood for Colorado Territory was sustained; enough senators agreed that a district with a population of 30,000 was not yet worthy of statehood to win the day.

In January 1867, Congressman Stevens introduced legislation to dissolve the southern state governments and reconstitute them into five military districts, under martial law. The states would begin again by holding constitutional conventions, at which African-Americans could vote and former Confederates could not. In the legislative process, Congress added to the bill that restoration to the Union would follow the state's ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment, and completion of the process of adding it to the Constitution. Johnson and the southerners attempted a compromise, whereby the South would agree to a modified version of the amendment without the disqualification of former Confederates, and for limited black suffrage. The Republicans insisted on the full language of the amendment, and the deal fell through. Although Johnson could have pocket vetoed the First Reconstruction Act as it was presented to him less than ten days before the end of the Thirty-Ninth Congress, he chose to veto it directly on March 2, 1867; Congress overruled him the same day. The same day, Congress passed the Tenure of Office Act over the President's veto, in response to Johnson statements during the Swing Around the Circle that he planned to fire his Cabinet officials who did not agree with him. This bill, which required Senate approval for the firing of Cabinet officers during the tenure of the president who appointed them and for one month afterwards, was immediately controversial, with some senators doubting its constitutionality, and that its terms applied to Johnson, whose key Cabinet officers were Lincoln holdovers.

Impeachment, trial and acquittal

Secretary of War Edwin Stanton was an able and hard-working man, but difficult to deal with. Lincoln related that he had been told that Stanton could be replaced by others, who had the secretary's abilities without being so prickly, and stated "All I can say is, I haven't met 'em; I don't know 'em." Johnson both admired and was exasperated by his War Secretary, who in combination with General of the Army Grant, worked to undermine the president's southern policy from within his own administration. Johnson considered firing Stanton, but respected him for his wartime service as secretary, and the self-educated president was intimidated by Stanton's brains and support in Congress. Stanton, for his part, feared who Johnson might appoint as his successor, and refused to resign although the fact that he disagreed with his president was public.

The new Congress met for a few weeks in March 1867, then adjourned, leaving the House Committee on the Judiciary behind, charged with reporting back to the full House whether there were grounds for Johnson to be impeached. This committee duly met, examining Johnson's bank accounts, and summoning members of the Cabinet to testify. When a federal court released former Confederate president Davis on bail on May 13 from the imprisonment he had endured since being captured after the war, the committee investigated whether Johnson had impeded the prosecution of Davis. It learned that Johnson was more eager to have Davis tried than any in his government. A bipartisan majority of the committee voted down impeachment charges; the committee adjourned on June 3.

Later in June Johnson and Stanton battled over the question of whether the military officers placed in command of the South could override the civil authorities. Johnson had Attorney General Henry Stanbery issue an opinion backing his position that they could not. Johnson sought to pin down Stanton either as for, and thus endorsing Johnson's position, or against, in which case he would be opposed to his President and the rest of the Cabinet. Stanton evaded the point in meetings and written communications. When Congress reconvened in July, it passed a Reconstruction Act against Johnson's position, waited for his veto, overruled it, and went home. In addition to clarifying the powers of the generals, the legislation also deprived Johnson of control over the Army in the South. With Congress in recess until November, Johnson decided to fire Stanton and relieve one of the military commanders, General Philip Sheridan, who had dismissed the governor of Texas and installed a replacement with little popular support. He was initially deterred by a strong objection from Grant. On August 5, the President demanded Stanton's resignation; he refused to do so with Congress out of session. Johnson then suspended him pending the next meeting of Congress as permitted under the Tenure of Office Act; Grant agreed to serve as temporary replacement while continuing to lead the Army.

Grant, under protest, followed Johnson's order transferring Sheridan, and another of the district commanders, Daniel Sickles, who had angered Johnson for firmly following Congress's plan. Johnson also issued a proclamation pardoning most Confederates, exempting those who held office under the Confederacy, or who had served in federal office before the war and had breached their oaths. Although Republicans expressed anger at Johnson's actions, the 1867 elections generally went Democratic. No congressional seats were directly elected, but Democrats took control of the Ohio General Assembly, allowing them to defeat for re-election one of Johnson's strongest opponents, Senator Benjamin Wade. Voters in Ohio, Connecticut, and Minnesota turned down propositions to grant African-Americans the vote. The adverse results momentarily put a stop to Republican calls to impeach Johnson, who was elated by the elections. Nevertheless, once Congress met in November, the Judiciary Committee reversed itself and passed a resolution of impeachment against Johnson. After much debate about whether anything he had done was a high crime or misdemeanor, the standard under the Constitution, the resolution was defeated by the House of Representatives on December 7, 1867, by a vote of 57 in favor to 108 opposed.

Johnson notified Congress of War Secretary Stanton's suspension and Grant's interim appointment. When it reconvened in January 1868, the Senate disapproved of his action, and reinstated Stanton, contending Johnson had violated the Tenure of Office Act. Grant stepped aside over Johnson's objection (causing a complete break between them). Johnson dismissed Stanton and appointed Lorenzo Thomas to replace him. Stanton refused to leave his office, and on February 24, 1868, the House impeached Johnson for intentionally violating the Tenure of Office Act, by a vote of 128 to 47. The House subsequently adopted eleven articles of impeachment, for the most part bearing on Johnson's violation of the Tenure of Office Act in his dismissal of Stanton and appointment of Thomas, and for questioning the legitimacy of Congress.

On March 5, 1868, the impeachment trial began in the Senate and lasted almost three months; Congressmen George S. Boutwell, Benjamin Butler and Thaddeus Stevens acted as managers for the House, or prosecutors, and William M. Evarts, Benjamin R. Curtis and former Attorney General Stanbery (who had resigned his office to serve) were Johnson's counsel; Chief Justice Chase served as presiding judge. Johnson's defense relied on the provision of the Tenure of Office Act that made it applicable only to appointees of the current administration. Since Lincoln had appointed Stanton, the defense maintained the president had not violated the act, and also argued that the President had the right to test the constitutionality of an act of Congress in the courts. Johnson's counsel were adamant that he make no appearance at the trial or public comments about the proceedings, and except for a pair of interviews in April, he complied.

Johnson maneuvered to gain an acquittal; for example, he pledged to Iowa Senator James W. Grimes that he would not interfere with Congress's Reconstruction efforts. Grimes reported to a group of Moderates, many of whom voted for acquittal, that he believed Johnson would keep his word. Johnson also promised to install the respected John Schofield as War Secretary Kansas Senator Edmund G. Ross received assurances that the new constitutions ratified in South Carolina and Arkansas would be transmitted to the Congress. However, Johnson refused to fire Treasury Secretary Hugh McCulloch, fearing to alienate wealthy supporters. One reason why senators were reluctant to remove Johnson was that his successor would have been Ohio Senator Wade, the president pro tempore of the Senate. Wade, a lame duck who left office in early 1869, was a Radical who supported such measures as women's suffrage, placing him beyond the pale politically in much of the nation. Additionally, a President Wade was seen as an obstacle to Grant's presidential ambitions.

With the dealmaking, Johnson was confident of the result in advance of the initial voting on May 16, and in the days leading up to the ballot, newspapers reported that Stevens and his radicals had given up. On May 16, the Senate voted on the 11th article of impeachment, which accused Johnson of firing Stanton in violation of the Tenure of Office of Act once the Senate had overturned his suspension. Thirty-five senators voted "guilty" and 19 "not guilty", thus falling short by a single vote of the two-thirds majority required for conviction in impeachment trials. Seven Republicans—Senators Grimes, Ross, Trumbull, William Pitt Fessenden, Joseph S. Fowler, John B. Henderson, and Peter G. Van Winkle voted to acquit the President. With Stevens bitterly disappointed at the result, the Senate then adjourned for the Republican National Convention, at which General Grant was nominated for president. It returned on May 26 and voted on the second and third articles, with identical 35–19 results, after which Johnson's opponents gave up and dismissed proceedings. Stanton "relinquished" his office on May 26, 1868, after which the Senate confirmed Schofield. Attorney General Stanbery had given up his office to serve as one of Johnson's managers in the Senate trial; when Johnson subsequently renominated him, the Senate refused to confirm him.