| Revision as of 15:19, 15 May 2006 editGhirlandajo (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers89,629 edits template talk is no official guideline← Previous edit | Revision as of 15:46, 15 May 2006 edit undoMitsuhirato (talk | contribs)2,006 editsNo edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

| In February ] the Russian army had almost reached Constantinople, but scared the city might fall, the ] sent a fleet of battleships to intimidate Russia from entering the city. Under pressure from the fleet to negotiate and having suffered enormous losses (by some estimates about 200,000 men) Russia agreed a settlement under the ] (''Ayastefanos Anlaşması'' in ]) on ], by which the Ottoman Empire would recognize the independence of ], ], ], and autonomy of ]. | In February ] the Russian army had almost reached Constantinople, but scared the city might fall, the ] sent a fleet of battleships to intimidate Russia from entering the city. Under pressure from the fleet to negotiate and having suffered enormous losses (by some estimates about 200,000 men) Russia agreed a settlement under the ] (''Ayastefanos Anlaşması'' in ]) on ], by which the Ottoman Empire would recognize the independence of ], ], ], and autonomy of ]. | ||

| After the San Stefano treaty, the Russians set up their own governmental system in the new Bulgaria. Russians as well as Bulgarian nationalists then conducted a massacre of Turks, especially Muslims, on the scale of the ]. <ref> Justin McCarthy, ''Death and Exile: The Ethnic Cleansing of Ottoman Muslims, 1821-1922'', (Princeton, N.J: Darwin Press, c1995), 64</ref> <ref>REPORT OF THE INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION To Inquire into the causes and Conduct OF THE BALKAN WARS, PUBLISHED BY THE ENDOWMENT WASHINGTON, D.C. 1914, http://vmro.150m.com/en/carnegie/</ref> Although many of the Bulgarian perpetrators were peasants, who had lived side by side with Muslims in mixed villages for hundreds of years, they were spurred on by Russian ]. By the conclusion of the war more than half the Muslims in Bulgaria had either died, or fled as refugees. The Jewish population suffered the same fate as the Muslims, being killed or forced to flee by the Russians.<ref> Justin McCarthy, ''Death and Exile: The Ethnic Cleansing of Ottoman Muslims, 1821-1922'', (Princeton, N.J: Darwin Press, c1995), 85</ref> Whether or not this event was an 'ethnic cleansing' is up for debate, however the demographic changes which occurred then can still be seen today in the modern state of Bulgaria. | |||

| Alarmed by the extension of Russian power into the Balkans, the ] later forced modifications of the treaty in the ]. The main change here was that Bulgaria would be split into three: the northern and eastern parts to become principalities as before, though with different governors; and the Macedonian region, originally part of Bulgaria under San Stefano, would return to direct Ottoman administration.<ref>L.S. Stavrianos, The Balkans Since 1453, (London: Hurst & Company, 2000)</ref> | Alarmed by the extension of Russian power into the Balkans, the ] later forced modifications of the treaty in the ]. The main change here was that Bulgaria would be split into three: the northern and eastern parts to become principalities as before, though with different governors; and the Macedonian region, originally part of Bulgaria under San Stefano, would return to direct Ottoman administration.<ref>L.S. Stavrianos, The Balkans Since 1453, (London: Hurst & Company, 2000)</ref> | ||

Revision as of 15:46, 15 May 2006

| Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Plevna Monument near the walls of Kitai-gorod | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Russia, Romania | Ottoman Empire | ||||||||

The Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 had its origins in the Russian goal of gaining access to the Mediterranean Sea and liberating the Orthodox Christian Slavic peoples of the Balkan Peninsula (Bulgarians, Serbians) from the Islamic-ruled Ottoman Empire. These nations delivered by the Russians from the centuries of Ottoman rule regard this war as the second beginning of their nationhood.

The war also provided an opportunity to gain full independence for the Kingdom of Romania. Although, unlike the rest of the Balkan counties, it had never been part of the Ottoman Empire, it was still officially under Ottoman suzerainty. Hence, in Romanian historic works, the war is known as the Romanian War of Independence.

The war begins: Balkan sources and Russian maneuvering

An anti-Ottoman uprising occurred in Bosnia and Herzegovina in the summer of 1875. The main reason for this revolt was the heavy tax burden imposed by financially defunct Ottoman (or Turkish) administration. Despite some relaxation of taxes, the uprising continued well over the end of 1875 and eventually triggered the Bulgarian April uprising of 1876. Tension in Bosnia and Russian support encouraged the principalities of Serbia and Montenegro's declaration of war against their nominal Ottoman overlord early in July. The war raised imperial appetite of the Great Powers Russia (Prince Gorchakov) and Austria-Hungary (Count Andrássy), who made the secret Reichstadt Agreement in July 8, on partitioning the Balkan peninsula depending on the outcome.

In August 1876, Serb forces, supported by Bulgarian and Russian volunteers, were defeated by the Ottoman army, which was the worst-case scenario for Russians and Austrians as they couldn't claim any Ottoman possessions. However the atrocities committed against the civilian Slav population during the war and during the Bulgarian April uprising had a wide-spread response throughout Europe. As a result the Constantinople Conference was held in December 1876 in Constantinople (now Istanbul). At this conference, at which Turkey was not represented, the Great Powers discussed the boundaries of one or more future autonomous Bulgarian provinces within the Ottoman Empire.

The Conference was interrupted by the Turkish foreign minister, who informed the delegates that Turkey had approved a new constitution, which guaranteed rights and freedoms of all ethnic minorities and Bulgarians would enjoy equal rights with all Ottoman citizens. Despite that, Russia remained hostile towards the Ottoman Empire, postulating that the constitution was only a partial solution. Through diplomatic negotiations Russians ensured the inaction of Austria-Hungary in future military operations. In Britain, the political signals were mixed. Despite strong civil support for the idea of Bulgarian liberation, fostered in Britain by the writings and speeches of former Prime Minister William Gladstone, the leader at the time, Benjamin Disraeli was much more pessimistic of Russian intentions. He positioned Britain as the defender of the Ottoman Empire, as they had done in the Crimean War twenty years earlier. This lack of a uniform policy is evident in the negotiations of the Conference. The British delegate, Lord Salisbury, got on well with his Russian counterpart, Count Nicholas Ignatiev, and was able to reach a compromise agreement. Bulgaria would be divided into an eastern and western province, Bosnia-Herzegovina united into one province, and each of these three provinces would have a considerable degree of autonomy, including a provincial assembly and a local police force. Also, Serbia was to lose no territory and Montenegro was to be allowed to keep the areas she had overrun in Herzegovina and northern Albania. However safe in the knowledge that they had the support of Disraeli, the Ottomans stood firm, leading to the collapse of the talks, and the outbreak of hostilities.

==Prosecution: the one-eyed and the blind ==

| Russo-Turkish Wars | |

|---|---|

| Turco-Mongol raids |

Russia declared war on Turkey on 24 April 1877. Some described this war as "a war between the one-eyed and the blind", so many errors of strategy and judgment were committed on both sides. This, however, was all too common a problem for contemporaneous warfare, from the Crimean War to the Boer Wars.

In the beginning of the war the outcome was far from obvious. The Russians could raise a larger army, an army of about 200,000 was within their reach. The Turks had about 160,000 troops on the Balkan peninsula. The Turks had the advantage of being fortified, and they also had a complete command of the Black Sea, and had patrol boats along the Danube river.

In reality, however, most of the time the Turks used only about 25% of their military capacity. In addition to that, the Turks had no idea of Russian plans and made little attempt to predict their actions and to counter them. They preferred to stay fortified and wait until the enemy knocked on their doors.

The Turkish military command in Istanbul made poor assumptions of Russian intentions. They decided that Russians would be too lazy to march along the Danube and cross it away from the delta, and would prefer the short way along the Black Sea coast, thus ignoring the fact that this area had the strongest, well supplied and garrisoned Turkish fortresses. So there was only one well manned fortress along the inner part of the river Danube. This was Vidin, and it was garrisoned simply because the troops, lead by Osman Pasha, had just crushed the Serbs in their recent war against Turkey.

Course of the War

At the start of the war, Russia destroyed all vessels along the Danube and mined the river, thus ensuring it could cross the Danube at any point it wanted. This didn't mean anything to the Turkish command. In June a small Russian unit passed the Danube close to the delta, at Galaţi and marched towards Ruse. This made the Turks even more confident that the big Russian force would come right through the middle of the Turkish stronghold.

Then in July the Russians, unobstructed, constructed a bridge across the Danube at Svishtov, and began crossing. There were no significant Turkish troops in the area. The command in Istanbul ordered Osman Pasha to march in that direction and fortify the nearby fortress of Nikopol. On his way to Nikopol, Osman Pasha learned that the Russians had already secured it, and so moved to Pleven.

Less than 24-hours after Osman Pasha fortified Pleven, numerous Russian forces under the charismatic "White General" Mikhail Skobelev attacked the city. Osman Pasha organized a brilliant defence and repelled two Russian attacks with huge casualties on the Russian side. At that point the sides were almost equal in numbers and the Russian Army was very discouraged. Most analysts agree that a counter-attack would have allowed the Turks to gain control and destroy the passing bridge. However, Osman Pasha had orders to stay fortified in Pleven, and so did not leave that fortress.

Russia had no more troops to throw against Pleven, so they besieged it, and subsequently asked the Romanians to provide extra troops. Soon afterwards, Romanian forces crossed the Danube and joined the siege. On August 16th, at Gorni-Studen, the armies around Pleven — renamed the West Armies — were placed under the command of the Romanian Prince Carol, aided by the Russian general Pavel Dmitrievich Zotov and the Romanian general Alexandru Cernat. The Romanians fought bravely to capture the Grivitza redoubts around Pleven, and kept them under their control until the very end of the siege. The siege of Pleven (July–December 1877) turned to victory only after Russian and Romanian forces cut off all supply routes to the fortified Turks, starving them and thus forcing their surrender. By the end of November, the Ottoman forces tried to cut through the encirclement in the direction of Opanets, in the sector defended by Romanian troops. The attempt failed and, on November 28th, the wounded commander Osman Pasha was captured and surrendered his sword to the Romanian colonel Mihail Christodulo Cerchez.

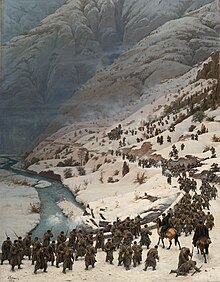

Russians under Field Marshal Joseph Vladimirovich Gourko succeeded in capturing the passes at the Stara Planina mountain which were crucial for manoeuvering. Next, both sides fought a series of battles for Shipka Pass. Gurko made several attacks on the Pass and eventually secured it. Turkish troops spent much effort to recapture this important route, to use it to reinforce Osman Pasha in Pleven, but failed. Eventually Gourko led a final offensive which crushed the Turks around Shipka Pass. The Turkish offensive against Shipka Pass is considered one of the major mistakes of the war, as other passes were virtually unguarded. At this time a huge number of Turkish troops stayed fortified along the Black Sea coast and engaged in very few operations.

Besides the Romanian Army, a strong Finnish contingent and more than 12,000 volunteer Bulgarian army (Opalchenie) from the local Bulgarian population as well as many hajduk detachments fought in the war on the side of the Russians. To express his gratitude to the Finnish batallion, the Tsar elevated the regiment on their return home to the name Old Guard Battalion, which they still hold.

== Conclusion: the Powers intervene ==

In February 1878 the Russian army had almost reached Constantinople, but scared the city might fall, the British sent a fleet of battleships to intimidate Russia from entering the city. Under pressure from the fleet to negotiate and having suffered enormous losses (by some estimates about 200,000 men) Russia agreed a settlement under the Treaty of San Stefano (Ayastefanos Anlaşması in Turkish) on March 3, by which the Ottoman Empire would recognize the independence of Romania, Serbia, Montenegro, and autonomy of Bulgaria.

After the San Stefano treaty, the Russians set up their own governmental system in the new Bulgaria. Russians as well as Bulgarian nationalists then conducted a massacre of Turks, especially Muslims, on the scale of the Ottoman massacre of Bulgarians in 1876. Although many of the Bulgarian perpetrators were peasants, who had lived side by side with Muslims in mixed villages for hundreds of years, they were spurred on by Russian Pan-slavism. By the conclusion of the war more than half the Muslims in Bulgaria had either died, or fled as refugees. The Jewish population suffered the same fate as the Muslims, being killed or forced to flee by the Russians. Whether or not this event was an 'ethnic cleansing' is up for debate, however the demographic changes which occurred then can still be seen today in the modern state of Bulgaria.

Alarmed by the extension of Russian power into the Balkans, the Great Powers later forced modifications of the treaty in the Congress of Berlin. The main change here was that Bulgaria would be split into three: the northern and eastern parts to become principalities as before, though with different governors; and the Macedonian region, originally part of Bulgaria under San Stefano, would return to direct Ottoman administration.

See also

- Alexander of Bulgaria

- History of the Balkans

- History of Europe

- Romanian War of Independence

- Battles of the Russo-Turkish War, 1877–78

- Congress of Berlin

References

- L.S. Stavrianos, The Balkans Since 1453, (London: Hurst & Company, 2000)

- L.S. Stavrianos, The Balkans Since 1453, (London: Hurst & Company, 2000)

- Justin McCarthy, Death and Exile: The Ethnic Cleansing of Ottoman Muslims, 1821-1922, (Princeton, N.J: Darwin Press, c1995), 64

- REPORT OF THE INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION To Inquire into the causes and Conduct OF THE BALKAN WARS, PUBLISHED BY THE ENDOWMENT WASHINGTON, D.C. 1914, http://vmro.150m.com/en/carnegie/

- Justin McCarthy, Death and Exile: The Ethnic Cleansing of Ottoman Muslims, 1821-1922, (Princeton, N.J: Darwin Press, c1995), 85

- L.S. Stavrianos, The Balkans Since 1453, (London: Hurst & Company, 2000)

External links

- Template:En icon Online Chapter on the War, from the book "The Balkans Since 1453" by Stavrianos

- Template:Ru icon Russian website on the war

- Template:En icon The Romanian Army of the Russo-Turkish War 1877-78

- Template:Ru icon Text of the book Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78 and the Exploits of Liberators

- Template:Bg icon Image Gallery