| Revision as of 01:24, 24 February 2013 edit84.153.41.120 (talk) →Etymology← Previous edit | Revision as of 22:17, 24 February 2013 edit undoNeo Poz (talk | contribs)507 edits explain potentially biased "redistributionist" term which could mean in either directionNext edit → | ||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

| A '''welfare state''' is a "concept of government in which the state plays a key role in the protection and promotion of the economic and social well-being of its citizens. It is based on the principles of ], equitable ], and public responsibility for those unable to avail themselves of the minimal provisions for a good life. The general term may cover a variety of forms of economic and social organization."<ref>, Britannica Online Encyclopedia</ref> | A '''welfare state''' is a "concept of government in which the state plays a key role in the protection and promotion of the economic and social well-being of its citizens. It is based on the principles of ], equitable ], and public responsibility for those unable to avail themselves of the minimal provisions for a good life. The general term may cover a variety of forms of economic and social organization."<ref>, Britannica Online Encyclopedia</ref> | ||

| Modern welfare states include the ], such as ], ], ], ], and ]<ref>Paul K. Edwards and Tony Elger, ''The global economy, national states and the regulation of labour'' (1999) p, 111</ref> which employ a system known as the ]. The welfare state involves a transfer of funds from the state, to the services provided (i.e. healthcare, education) as well as directly to individuals ("benefits"). |

Modern welfare states include the ], such as ], ], ], ], and ]<ref>Paul K. Edwards and Tony Elger, ''The global economy, national states and the regulation of labour'' (1999) p, 111</ref> which employ a system known as the ]. The welfare state involves a transfer of funds from the state, to the services provided (i.e. healthcare, education) as well as directly to individuals ("benefits"). | ||

| The welfare state is funded through ]ist ]ation and is often referred to as a type of "]".<ref>"Welfare state." Encyclopedia of Political Economy. Ed. Phillip Anthony O'Hara. Routledge, 1999. p. 1245</ref> Such taxation usually includes a larger ] for people with higher incomes, called a ]. This helps to reduce the income gap between the rich and poor.<ref>Pickett and Wilkinson, '']'', 2011</ref> When ] is low, ] will be relatively high, because more people who want ordinary ]s and services will be able to afford them, while the ] will not be as relatively ] by the wealthy.<ref name=pigou>''''| ]</ref><ref name=OstryBerg>Andrew Berg and Jonathan D. Ostry, 2011, "?" IMF Staff Discussion Note SDN/11/08, ]</ref> | |||

| ==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

Revision as of 22:17, 24 February 2013

This article is about the welfare state as a general concept. For the system known as "the Welfare State" in the United Kingdom, see Welfare State.

A welfare state is a "concept of government in which the state plays a key role in the protection and promotion of the economic and social well-being of its citizens. It is based on the principles of equality of opportunity, equitable distribution of wealth, and public responsibility for those unable to avail themselves of the minimal provisions for a good life. The general term may cover a variety of forms of economic and social organization."

Modern welfare states include the Nordic countries, such as Iceland, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Finland which employ a system known as the Nordic model. The welfare state involves a transfer of funds from the state, to the services provided (i.e. healthcare, education) as well as directly to individuals ("benefits").

The welfare state is funded through redistributionist taxation and is often referred to as a type of "mixed economy". Such taxation usually includes a larger income tax for people with higher incomes, called a progressive tax. This helps to reduce the income gap between the rich and poor. When income inequality is low, aggregate demand will be relatively high, because more people who want ordinary consumer goods and services will be able to afford them, while the labor force will not be as relatively monopolized by the wealthy.

Etymology

The German term Sozialstaat ("social state") has been used since 1870 to describe state support programs devised by German Sozialpolitiker ("social politicians") and implemented as part of Bismarck's conservative reforms. The literal English equivalent "social state" never caught on in Anglophone countries, until the Second World War, when Anglican Archbishop William Temple, author of the book Christianity and the Social Order (1942), popularized the concept using the phrase "welfare state", contrasting wartime Britain's welfare state with the "warfare state" of Nazi Germany. Bishop Temple's use "welfare state" has been connected to Benjamin Disraeli's 1845 novel Sybil: or the Two Nations (i.e., the rich and the poor), which speaks of "the only duty of power, the social welfare of the PEOPLE.'" At the time he wrote Sybil, Disraeli, later Prime Minister, belonged to Young England, a conservative group of youthful Tories who were appalled by what they saw as the Whig indifference to the horrendous conditions of the industrial poor and attempted to kindle among the privileged classes a sense of responsibility toward the less fortunate and a recognition of the dignity of labor that they imagined had characterized England during the Feudal Middle Ages.

The Italian term stato sociale ("social state") reproduces the German term. The Swedish welfare state is called Folkhemmet — literally, "folk home", and goes back to the 1936 compromise between Swedish trade unions and large corporations. Sweden's mixed economy is based on strong unions, a robustly funded system of social security, and universal health care. In Germany, the term Wohlfahrtsstaat, a direct translation of the English "welfare state", is used to describe Sweden's social insurance arrangements. Spanish and many other languages employ an analogous term: estado del bienestar— literally, "state of well-being". In Portuguese, two similar phrases exist: estado do bem-estar social, which means "state of social well-being", and estado de providência— "providing state", denoting the state's mission to ensure the basic well-being of the citizenry. In Brazil, the concept is referred to as previdência social, or "social providence".

History of welfare states

Germany

Otto von Bismarck, the first Chancellor of Germany, created the modern welfare state by building on a tradition of welfare programs in Prussia and Saxony that began as early as in the 1840s, and by winning the support of business. After the founding of German Social Democratic Party in 1875 by which Marxian socialists and the reformist followers of Ferdinand Lassalle were fused, Bismark became even more worried about this essentially moderate socialism. He also feared that recent Paris Commune would happen within his country. He viewed socialism as anarchical, republican and potentially revolutionary for a monarchist empire. Using two attempts to assassinate the emperor (in neither case by Social Democrats) as excuse, Bismarck implemented Antisocialist Laws from 1878 to 1890 to prohibit socialist meetings and socialist newspapers. In compromise, Bismarck introduced old age pensions, accident insurance and medical care that formed the basis of the modern European welfare state. His paternalistic programs won the support of German industry because its goals were to win the support of the working class for the German Empire and reduce the outflow of immigrants to the United States, where wages were higher but welfare did not exist. Bismarck further won the support of both industry and skilled workers by his high tariff policies, which protected profits and wages from American competition, although they alienated the liberal intellectuals who wanted free trade.

United Kingdom

Main article: Welfare state in the United KingdomThe United Kingdom, as a modern welfare state, started to emerge with the Liberal welfare reforms of 1906–1914 under Liberal Prime Minister Herbert Asquith. These included the passing of the Old-Age Pensions Act in 1908, the introduction of free school meals in 1909, the 1909 Labour Exchanges Act, the Development Act 1909, which heralded greater Government intervention in economic development, and the enacting of the National Insurance Act 1911 setting up a national insurance contribution for unemployment and health benefits from work.

In December 1942, the Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee on Social Insurance and Allied Services was published, known commonly as the Beveridge Report after its chairman, Sir William Beveridge, proposing a series of measures to aid those who were in need of help, or in poverty. Beveridge recommended to the government that they should find ways of tackling the five giants, being Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness. He argued to cure these problems, the government should provide adequate income to people, adequate health care, adequate education, adequate housing and adequate employment. It proposed that 'All people of working age should pay a weekly National Insurance contribution. In return, benefits would be paid to people who were sick, unemployed, retired or widowed.'

The basic assumptions of the report were that the National Health Service would provide free health care to all citizens. The Universal Child Benefit was a scheme to give benefits to parents, encouraging people to have children by enabling them to feed and support a family. One theme of the report was the relative cheapness of universal benefits. Beveridge quoted miners' pension schemes as some of the most efficient available, and argued that a state scheme would be cheaper to run than individual friendly societies and private insurance schemes, as well as being cheaper than means-tested government-run schemes for the poor.

The report's recommendations were adopted by the Liberal Party, Conservative Party and then by the Labour Party. Following the Labour election victory in the 1945 general election many of Beveridge's reforms were implemented through a series of Acts of Parliament. On 5 July 1948, the National Insurance Act, National Assistance Act and National Health Service Act came into force, forming the key planks of the modern UK welfare state. The cheapness of what was to be called National Insurance was an argument alongside fairness, and justified a scheme in which the rich paid in and the state paid out to the rich, just as for the poor. In the original scheme, only some benefits called National Assistance were to be paid regardless of contribution. Universal benefits paid to rich and poor such as child benefit were particularly beneficial after the Second World War when the birth rate was low. Universal Child Benefit may have helped drive the baby boom.

Before 1939, most health care had to be paid for through non government organisations – through a vast network of friendly societies, trade unions and other insurance companies which counted the vast majority of the UK working population as members. These friendly societies provided insurance for sickness, unemployment and invalidity, therefore providing people with an income when they were unable to work. Following the implementation of Beveridge's recommendations, institutions run by local councils to provide health services for the uninsured poor, part of the poor law tradition of workhouses, were merged into the new national system. As part of the reforms, the Church of England also closed down its voluntary relief networks and passed the ownership of thousands of church schools, hospitals and other bodies to the state.

Welfare systems continued to develop over the following decades. By the end of the 20th century parts of the welfare system had been restructured, with some provision channelled through non-governmental organizations which became important providers of social services.

The United States

Although the United States was to lag far behind European countries in instituting concrete social welfare policies, the earliest and most comprehensive philosophical justification for the welfare state was produced by an American, the sociologist Lester Frank Ward (1841–1913), whom the historian Henry Steele Commager called "the father of the modern welfare state". Paternalistic reforms, such as those associated with Bismark, had been strongly opposed by Herbert Spencer and his American disciples, whose laissez-faire theories were quickly adopted by American businessmen. Spencer argued that coddling the poor and unfit would only encourage them to reproduce, obstructing the scientific progress of the human race. Ward challenged Spencer’s contention that social phenomena are not amenable to human control. “It is only through the artificial control of natural phenomena that science is made to minister to human needs.“ he wrote, “and if social laws are really analogous to physical laws, there is no reason why social science should not receive practical application such as have been given to physical science.” "The charge of paternalism" wrote Ward:

is chiefly made by the class that enjoys the largest share of government protection. Those who denounce it are those who most frequently and successfully invoke it. Nothing is more obvious today than the signal inability of capital and private enterprise to take care of themselves unaided by the state; and while they are incessantly denouncing "paternalism," by which they mean the claim of the defenseless laborer and artisan to a share in this lavish state protection, they are all the while besieging legislatures for relief from their own incompetency, and "pleading the baby act" through a trained body of lawyers and lobbyists. The dispensing of national pap to this class should rather be called "maternalism," to which a square, open, and dignified paternalism would be infinitely preferable.

Central to Ward's theories was his belief that a universal and comprehensive system of education was necessary if a democratic government was to function successfully. His writings profoundly influenced younger generations of progressive thinkers such as Theodore Roosevelt, Thomas Dewey, and Frances Perkins, among others. By 1918 all the states in the U.S. had passed laws requiring compulsory elementary education. Such laws, however, did not apply equally to whites and blacks. In Southern states such as Mississippi, for example, individual counties were allowed to "opt out" of compulsory education requirements.

The United States would be the only industrialized country that went into the Great Depression with no social insurance policies in place. It was not until 1935 that significant, if conservative by European standards, social insurance policies were finally instituted under Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal. In 1938, the Fair Labor Standards Act, limiting the work week to 40 hours and banning child labor for children under 16, was passed over stiff congressional opposition. The price of passgage of the New Deal's Social Security and Fair Labor acts was the exclusion of domestic, agricultural, and restaurant workers, who were largely African-American, from social security benefits and labor protections.

In 1996, Massachusetts began a state-funded children's health insurance program that became the model for State Children's Health Insurance Program, sponsored by Senator Edward Kennedy and signed into law in 1997. Now known as CHIP, it provides matching federal funds to states for children's medical care.

Oil countries

Saudi Arabia, Brunei, Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates have become welfare states exclusively for their citizens. All foreign nationals, including legal residents and legal long term employees are prohibited from partaking in the benefits of the welfare state.

Modern model

Modern welfare programs differed from previous schemes of poverty relief due to their relatively universal coverage. The development of social insurance in Germany under Bismarck was particularly influential. Some schemes were based largely in the development of autonomous, mutualist provision of benefits. Others were founded on state provision. The term was not, however, applied to all states offering social protection. The sociologist T.H. Marshall identified the welfare state as a distinctive combination of democracy, welfare and capitalism. Examples of early welfare states in the modern world are Germany, all of the Nordic countries, the Netherlands, Uruguay and New Zealand and the United Kingdom in the 1930s.

Changed attitudes in reaction to the Great Depression were instrumental in the move to the welfare state in many countries, a harbinger of new times where "cradle-to-grave" services became a reality after the poverty of the Depression. During the Great Depression, it was seen as an alternative "middle way" between communism and capitalism. In the period following the World War II, many countries in Europe moved from partial or selective provision of social services to relatively comprehensive coverage of the population.

The activities of present-day welfare states extend to the provision of both cash welfare benefits (such as old-age pensions or unemployment benefits) and in-kind welfare services (such as health or childcare services). Through these provisions, welfare states can affect the distribution of wellbeing and personal autonomy among their citizens, as well as influencing how their citizens consume and how they spend their time.

Three worlds of the welfare state

According to Esping-Andersen (1990), there are three ways of organizing a welfare state instead of only two.

Esping-Andersen categorised three different types of welfare states in the 1990 book 'The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism'. Though increasingly criticised (for a review of the debate on the Three worlds of Welfare Capitalism see Art and Gelissen and Ferragina and Seeleib-Kaiser), these classifications remain the most commonly used in distinguishing types of modern welfare states, and offer a solid starting point in such analysis. It has been argued that these typologies remain a fundamental heuristic tool for welfare state scholars, even for those who claim that in-depth analysis of a single case is more suited to capture the complexity of different social policy arrangements. Welfare typologies have the function to provide a comparative lens and place even the single case into a comparative perspective (Ferragina and Seeleib-Kaiser 2011).

Esping-Andersen (1990) constructed the welfare regime typology acknowledging the ideational importance and power of the three dominant political movements of the long 20th century in Western Europe and North America, that is Social Democracy, Christian Democracy (conservatism) and Liberalism (Stephens 1979; Korpi 1983; Van Kersbergen 1995; Ferragina and Seeleib-Kaiser 2011).

- The ideal Social-Democratic welfare state is based on the principle of universalism granting access to benefits and services based on citizenship. Such a welfare state is said to provide a relatively high degree of autonomy, limiting the reliance of family and market (Ferragina and Seeleib-Kaiser 2011). In this context, social policies are perceived as 'politics against the market' (Esping-Andersen 1985).

- Christian-democratic welfare states are based on the principle of subsidiarity and the dominance of social insurance schemes, offering a medium level of decommodification and a high degree of social stratification.

- The liberal regime is based on the notion of market dominance and private provision; ideally, the state only interferes to ameliorate poverty and provide for basic needs, largely on a means-tested basis. Hence, the decommodification potential of state benefits is assumed to be low and social stratification high (Ferragina and Seeleib-Kaiser 2011).

Based on the decommodification index Esping-Andersen divided into the following regimes 18 OECD countries (Esping-Andersen 1990: 71):

- Social Democratic: Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden

- Christian Democratic: Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Spain and Italy;

- Liberal: Australia, Canada, Japan, Switzerland and the US;

- Not clearly classified: Ireland, New Zealand and the United Kingdom.

These 18 countries can be placed on a continuum from the most purely social-democratic, Sweden, to the most liberal country, the United States (Ferragina and Seeleib-Kaiser 2011).

Rothstein argues that in the first model, the state is primarily concerned with directing the resources to “the people most in need”. This requires a tight bureaucratic control over the people concerned. Under the second model, the state distributes welfare with as little bureaucratic interference as possible, to all people who fulfill easily established criteria (e.g. having children, receiving medical treatment, etc.). This requires high taxation. This model was constructed by the Scandinavian ministers Karl Kristian Steincke and Gustav Möller in the 30s and is dominant in Scandinavia. The third model is similar to the one found in Britain (Beveridge model) and is based more on citizenship and a certain level of welfare ‘as a right’, which may then be modified according to needs.

Effects on poverty

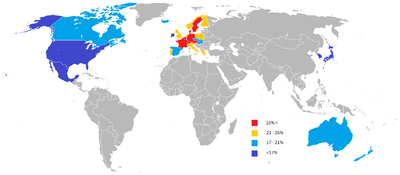

Main article: Welfare's effect on povertyEmpirical evidence suggests that taxes and transfers considerably reduce poverty in most countries, whose welfare states commonly constitute at least a fifth of GDP. Most "welfare states" have considerably lower poverty rates than they had before the implementation of welfare programs.

| Country | Absolute poverty rate (1960–1991) (threshold set at 40% of U.S. median household income) |

Relative poverty rate

(1970–1997) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-welfare | Post-welfare | Pre-welfare | Post-welfare | |

| 23.7 | 5.8 | 14.8 | 4.8 | |

| 9.2 | 1.7 | 12.4 | 4.0 | |

| 22.1 | 7.3 | 18.5 | 11.5 | |

| 11.9 | 3.7 | 12.4 | 3.1 | |

| 26.4 | 5.9 | 17.4 | 4.8 | |

| 15.2 | 4.3 | 9.7 | 5.1 | |

| 12.5 | 3.8 | 10.9 | 9.1 | |

| 22.5 | 6.5 | 17.1 | 11.9 | |

| 36.1 | 9.8 | 21.8 | 6.1 | |

| 26.8 | 6.0 | 19.5 | 4.1 | |

| 23.3 | 11.9 | 16.2 | 9.2 | |

| 16.8 | 8.7 | 16.4 | 8.2 | |

| 21.0 | 11.7 | 17.2 | 15.1 | |

| 30.7 | 14.3 | 19.7 | 9.1 | |

Welfare expenditure

There is very little correlation between economic performance and welfare expenditure.

The table does not show the effect of expenditure on income inequalities, and does not encompass some other forms of welfare provision (such as occupational welfare).

The table below shows, first, welfare expenditure as a percentage of GDP for some (selected) OECD member states, with and without public education, and second, GDP per capita (PPP US$) in 2001:

| Nation | Welfare expenditure (% of GDP) omitting education |

Welfare expenditure (% of GDP) including education |

GDP per capita (PPP US$) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 29.2 | 37.9 | $29,000 | |

| 28.9 | 38.2 | $24,180 | |

| 28.5 | 34.9 | $23,990 | |

| 27.4 | 33.2 | $25,350 | |

| 27.2 | 32.7 | $25,520 | |

| 26.4 | 31.6 | $28,100 | |

| 26.0 | 32.4 | $26,730 | |

| 24.8 | 32.3 | $24,430 | |

| 24.3 | 27.3 | $27,190 | |

| 24.4 | 28.6 | $24,670 | |

| 24.3 | 28.4 | $17,440 | |

| 23.9 | 33.2 | $29,620 | |

| 23.0 | N/A | $9,450 | |

| 21.8 | 25.9 | $24,160 | |

| 21.1 | 25.5 | $18,150 | |

| 20.8 | N/A | $53,780 | |

| 20.1 | N/A | $14,720 | |

| 20.1 | N/A | $12,340 | |

| 19.8 | 23.2 | $29,990 | |

| 19.6 | 25.3 | $20,150 | |

| 18.5 | 25.8 | $19,160 | |

| 18.0 | 22.5 | $25,370 | |

| 17.9 | N/A | $11,960 | |

| 17.8 | 23.1 | $27,130 | |

| 16.9 | 18.6 | $25,130 | |

| 14.8 | 19.4 | $36,000 | |

| 13.8 | 18.5 | $32,410 | |

| 11.8 | N/A | $8,430 | |

| 6.1 | 11.0 | $15,090 |

Figures from the OECD and the UNDP.

Criticisms

Main article: Criticisms of welfareThe notion, and the extent of, the modern welfare state has been criticized on economic, social, and ideological grounds from both the Left and the Right of the political spectrum. Critics disparage welfare as cynical vote-buying by politicians showering electorates with tax monies.

Another criticism is that some opponents suggest that welfare weakens private charity such as family, friends and non-governmental welfare organisations.

Karl Marx famously critiqued the basic institutions of the welfare state in his Address of the Central Committee to the Communist League by warning against the programs advanced by liberal democrats. Specifically, he argued that measures designed to increase wages, improve working conditions and provide welfare payments would be used to dissuade the working class away from socialism and the revolutionary consciousness he believed was necessary to achieve a socialist economy.

See also

3Notes

- Welfare state, Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- Paul K. Edwards and Tony Elger, The global economy, national states and the regulation of labour (1999) p, 111

- "Welfare state." Encyclopedia of Political Economy. Ed. Phillip Anthony O'Hara. Routledge, 1999. p. 1245

- Pickett and Wilkinson, The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better, 2011

- The Economics of Welfare| Arthur Cecil Pigou

- Andrew Berg and Jonathan D. Ostry, 2011, "Inequality and Unsustainable Growth: Two Sides of the Same Coin?" IMF Staff Discussion Note SDN/11/08, International Monetary Fund

- S. B. Fay, 'Bismarck's Welfare State', Current History, Vol. XVIII (January 1950), pp. 1-7.

- Munroe Smith's text "Four German Jurists"Smith, Munroe (1901). "Four German Jurists. IV". Political Science Quarterly. 16 (4). The Academy of Political Science: 669. doi:10.2307/2140421. ISSN 0032-3195. JSTOR 2140421.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Megginson, William L. (2001). "From State to Market: A Survey of Empirical Studies on Privatization" (PDF). Journal of Economic Literature. 39 (2): 321–389. doi:10.1257/jel.39.2.321.. ISSN 0022-0515.

{{cite journal}}: Check|doi=value (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help). - Sybil, p. 273, quoted in Michael Alexander, Medievalism: The Middle Ages in Modern England (New Haven: Yale University Press), , p. 93.

- Alexander, Medievalism, pp. xxiv–xxv, 62, 93, and passim.

- R.R. Palmer. A History of the Modern World. p. 596.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - E. P. Hennock, The Origin of the Welfare State in England and Germany, 1850–1914: Social Policies Compared (2007)

- Hermann Beck, Origins of the Authoritarian Welfare State in Prussia, 1815-1870 (1995)

- Elaine Glovka Spencer, "Rules of the Ruhr: Leadership and Authority in German Big Business Before 1914," Business History Review, Spring 1979, Vol. 53 Issue 1, pp 40-64

- Ivo N. Lambi, "The Protectionist Interests of the German Iron and Steel Industry, 1873-1879," Journal of Economic History, March 1962, Vol. 22 Issue 1, pp 59-70

- http://www.ifs.org.uk/bns/bn13.pdf

- ^ Nineteenth-Century Britain: A Very Short Introduction, Christopher Harvie and Colin Matthew, Oxford Paperbacks, published Aug 10, 2000, ISBN 978-0-19-285398-1)

- Politics and Modern Democracies, Volume 2, Charles W. Pipkin, The Macmillan Company, New York, 1931

- Bentley Gilbert, "David Lloyd George: Land, the Budget, and Social Reform," American Historical Review, Dec 1976, Vol. 81 Issue 5, pp 1058-66 in JSTOR

- Beveridge, Power and Influence

- Bagehot: God in austerity Britain The Economist, published 2011-12-10

- Pawel Zaleski Global Non-governmental Administrative System: Geosociology of the Third Sector, Gawin, Dariusz & Glinski, Piotr : "Civil Society in the Making", IFiS Publishers, Warszawa 2006

- Quoted in Thomas F. Gosset, Race: The History of an Idea in America (Oxford University Press, 1997 ), p. 161.

- Lester Frank Ward, Forum XX, 1895, quoted in Henry Steel Commager's The American Mind: An Interpretation of American Thought and Character Since the 1880s (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1950), p. 210.

- Henry Steele Commager, Editor, Lester Ward and the Welfare State (New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1967).

-

The last state to adopt a compulsory education act, Mississippi became the first to repeal it following the Supreme Court desegregation ruling of 1954. The attendance law of 1918 was amended in 1929; the 1920 statute excluded many blacks, for counties could elect not to abide by it and families living more that two-and-a-half miles were exempt.... In 1936-37, when the average school term for blacks in Mississippi was still only 100 days, average rural black terms elsewhere in the South ranged from 120 days in Alabama and Louisiana to 165 days in Florida. —Neil R. McMillen, Dark Journey (University of Illinois Press, 1990) p. 348.

- Social Services (2) - Saudi Arabia Information

- Royal Embassy of Saudi Arabia London

- "welfare state." O'Hara, Phillip Anthony (editor). Encyclopedia of political economy. Routledge 1999. p. 1245

- Esping-Andersen, Gøsta (1999). Social Foundations of Postindustrial Economies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-874200-2.

- Rice, James Mahmud (2006). "The Temporal Welfare State: A Crossnational Comparison" (PDF). Journal of Public Policy. 26 (3): 195–228. doi:10.1017/S0143814X06000523. ISSN 0143-814X.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Gosta Esping-Andersen. 1990. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Bo Rothstein: Just Institutions Matter: The Moral and Political Logic of the Universal Welfare State (Theories of Institutional Design), Cambridge 1998

- Emanuele Ferragina and Martin Seeleib-Kaiser (2011). Welfare regime debate: past, present, futures. Policy & Politics vol. 39 (4). p. 598.

- ^ Emanuele Ferragina and Martin Seeleib-Kaiser (2011). Welfare regime debate: past, present, futures. Policy & Politics, vol. 39 (4). p. 584.

- Emanuele Ferragina and Martin Seeleib-Kaiser (2011). Welfare regime debate: past, present, futures. Policy & Politics, vol. 39 (4). p. 597.

- ^ Kenworthy, L. (1999). Do social-welfare policies reduce poverty? A cross-national assessment. Social Forces, 77(3), 1119-1139.

- ^ Bradley, D., Huber, E., Moller, S., Nielson, F. & Stephens, J. D. (2003). Determinants of relative poverty in advanced capitalist democracies. American Sociological Review, 68(3), 22-51.

- Atkinson, A. B. (1995). Incomes and the Welfare State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-55796-8.

- Barr, N. (2004). Economics of the welfare state. New York: Oxford University Press (USA).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2001). "Welfare Expenditure Report" (Microsoft Excel Workbook). OECD.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (2003). "Human Development Indicators". Human Development Report 2003. New York: Oxford University Press for the UNDP.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - “Every election is a sort of advance auction sale of stolen goods.” - H. L. Mencken

- Brusco, Valeria (2004). "Vote Buying in Argentina". Latin American Research Review. 39 (2): 66–68. ISSN 0023-8791.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|E-ISSN=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - http://mises.org/journals/jls/21_2/21_2_1.pdf

- Karl Marx - Address of the Central Committee to the Communist League. 1850 retrieved January 5, 2013 from Marxists.org: "However, the democratic petty bourgeois want better wages and security for the workers, and hope to achieve this by an extension of state employment and by welfare measures; in short, they hope to bribe the workers with a more or less disguised form of alms and to break their revolutionary strength by temporarily rendering their situation tolerable."

References

- Arts, Wil and Gelissen John; "Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism or More? A State-of-the-art report" Journal of European Social Policy vol. 12 (2), pp. 137–158 (2002).

- Esping-Andersen, Gosta; Politics against markets, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press (1985).

- Esping-Andersen, Gosta; "The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism", Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press (1990).

- Ferragina, Emanuele and Seeleib-Kaiser, Martin; Welfare Regime Debate: Past, Present, Futures?; Policy & Politics, Vol. 39 (4), pp. 583–611 (2011).http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/tpp/pap/2011/00000039/00000004/art00010.

- Korpi, Walter; "The Demcoratic Class Struggle"; London: Routledge (1983).

- Kuhnle, Stein. "The Scandinavian Welfare State in the 1990s: Challenged but Viable." West European Politics (2000) 23#2 pp. 209–228

- Kuhnle, Stein. Survival of the European Welfare State 2000 Routledge ISBN 0-415-21291-X

- Stephens, John D. "The Transition from Capitalism to Socialism"; Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press (1979).

- Van Kesbergen "Social Capitalism"; London: Routledge (1995).

External links

- Center for Public Policy

- Social Policy Virtual Library Nov 23, 2012

- Social Sciences Information Gateway Nov 23, 2012

- Race and Welfare in the United States

- The Welfare State: A Critique Nov 23, 2012

- Shavell's criticism of social justice programmes

- Kaplow's criticism of social justice programmes.

- García Calvo's Analysis of Welfare Society

- World report on Welfare State

- Journal containing free daily information on welfare policies at local, national and EU level

Data and statistics

- OECD - Health Policy and Data: Health Division Website

- OECD - National Accounts: Statistics Portal November 23, 2012

- OECD - Social Expenditure database (SOCX) Website

- Contains figures on wages and benefit systems in various OECD member states

- Contains information on beenfit uprating policies in various countries