| Revision as of 22:39, 1 June 2013 edit202.29.241.180 (talk) →East to Kasif and el Buqqar on the Tel el Fara to Beersheba track: headings wrong← Previous edit | Revision as of 22:45, 1 June 2013 edit undo202.29.241.180 (talk) writing still needs to be improved and even the old woman that runs this page admits that, don't remove until it has been copyeditedNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{grammar}} | |||

| {{too long|date=May 2013}} | {{too long|date=May 2013}} | ||

| {{infobox military conflict | {{infobox military conflict | ||

Revision as of 22:45, 1 June 2013

| This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. You can assist by editing it. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. Consider splitting content into sub-articles, condensing it, or adding subheadings. Please discuss this issue on the article's talk page. (May 2013) |

| Stalemate in Southern Palestine | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Middle Eastern theatre of World War I | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

Fourth Army's 3rd, 16th and 53rd Divisions and reinforcements part of

Yildirim Army Group formed in June (included the German 701st, 702nd, and 703rd Pasa Infantry Battalions) along with the | ||||||

| Sinai and Palestine Campaign | |

|---|---|

|

The Stalemate in Southern Palestine began after the defeat of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) by the Ottoman Army at the Second Battle of Gaza in April 1917, and ended six months later with the Battle of Beersheba fought on the last day of October, during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign of World War I.

Units of the Ottoman Fourth Army were forced out of the Sinai Peninsula by a series of EEF victories beginning with the Battle of Romani in August 1916, followed by the Battle of Magdhaba in December and the Battle of Rafa in January 1917. The EEF then made two unsuccessful attempts to capture Gaza, beginning in March with the First Battle of Gaza, and followed in April by the Second Battle of Gaza. These two Ottoman victories halted the attempted EEF invasion of the Ottoman Empire's southern Palestine.

During the six month-long stalemate which followed these operations, the EEF held positions on the edge of the Negev Desert, while both sides engaged in continuous trench warfare and contested mounted patrolling of the open eastern flank. Both sides took the opportunity to reorganise their forces and change commanders, conduct training and put in place preparations for future major battles.

Background

See also: First Battle of Gaza and Second Battle of Gaza

After the first defeat at Gaza in March, the commander of Eastern Force, Lieutenant General Charles Dobell, had sacked Major General Dallas commanding 53rd (Welsh) Division and the division was transferred from the Desert Column into Eastern Force. After a second defeat on 21 April, General Archibald Murray sacked Dobell, promoting in his place the commander of Desert Column, Lieutenant General Philip Chetwode. Lieutenant General Henry Chauvel was promoted from command of the Anzac Mounted Division to command the Desert Column, while Major General Edward Chaytor was promoted from commanding the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade to replaced Chauvel. Murray would also be relieved of command of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) in June and sent back to England.

With its back to the Negev Desert, the EEF was fortunate that the Ottoman forces which had just defeated them during the Second Battle of Gaza, were not ordered to launch a large scale counterattack, which could have seen the EEF pushed back a long way. However, they were faced with the urgent problems of securing the positions held at the end of the battle, and reorganising and reinforcing the severely depleted infantry divisions. The EEF had suffered nearly 4,000 casualties during the first battle, and more than 6,000 casualties during the second battle for Gaza. The battle casualties had to be managed, the dead buried and their personal effects stored or sent home, and the wounded cared for. The EEF railway, which had reached Deir el Belah before the Second Battle of Gaza, was extended by a branch line to Shellal.

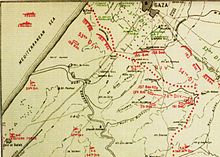

When the EEF moved back from the Second Battle of Gaza the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade took up a position at Tel el Fara on the Wadi Ghazzeh, where they dug trenches in case of a counter-attack. Both sides constructed extensive entrenchments, which were particularly strong where the trenches almost converged, to defend the Gaza to Beersheba lines. These trenches resembled those on the Western Front, except they were not so extensive and they had an open flank. These defensive lines were between 400–2,500 yards (370–2,290 m) apart, and stretched 30 miles (48 km) from Sheikh Ailin on the Mediterranean Sea to Sheikh Abbas and on to Tel el Jemmi and Beersheba. However from slightly beyond Sheikh Abbas, the continuous trench lines became a series of fortified strong points as the Ottoman line continued south east along the Gaza to Beersheba road, while the EEF line following the Wadi Ghazzeh, turned south to be as much as 9 miles (14 km) south of the Ottoman line.

Prelude

Ottoman forces

The strength of the Ottoman Fourth Army after the Second Battle of Gaza consisted of 174,908 men, 36,225 animals, 5,351 camels, armed with 145,840 rifles, 187 machine guns, and 282 artillery pieces. At this time the Fourth Army's five corps were responsible for garrisoning Palestine, the northern coast of Syria, and the Hejaz railway.

The strategic priorities of Enver Pasa and the Ottoman General Staff, were to use this force to push the EEF back to the Suez Canal, retake Baghdad and Mesopotamia along with Persia while, according to Erickson relying on "nonexistent interior lines of communication" and "chronic shortfalls in strategic transportation." In 1917 when the 54th and 59th Infantry Divisions became inoperative in Palestine and Syria, the loss of these two divisions has been blamed on problems of supply created by the single–track railway line, which was not completed across the Taurus and Amanus mountains until 1918. Despite these problems of supply, following the two victories at Gaza, the Ottoman Army was "greatly strengthened in both force and morale."

Within a few weeks of the April battle, Kress von Kressenstein commander of the victorious 3rd, 16th and 53rd Divisions of the Fourth Army, received the 7th and 54th Divisions as reinforcements. This force was reorganised into two corps to hold the Gaza to Beersheba line. They were the XX Corps (16th and 54th Infantry Divisions), with the 178th Infantry Regiment and the 3rd Cavalry Division attached, and the XXII Corps (3rd, 7th, and 53rd Infantry Divisions).

The formidable 30-mile (48 km) long Ottoman front line stretching eastwards from Gaza, dominated the country to the south, where the EEF was spread out in open low-lying country, interspersed by many deep wadis. From Gaza to Beersheba, it "stretch continuously for almost fifty kilometres." The defences at Atawineh, at Sausage Ridge, at Hareira, and at Teiaha supported each other as they overlooked an almost flat plain making a frontal attack against them virtually impossible.

Between Gaza and Hareira the Ottoman defences were strengthened and extended along the Gaza to Beersheba road, to the east of the Palestine railway line from Beersheba. Although these trenches did not extend to Beersheba, strong fortifications were built to the east and south of that town, some of which were blasted from solid rock, making the isolated town into a fortress. An EEF reconnaissance, which established an observation post in an old church near the junction of the Wadi Hannafish with the Wadi Sufi, reported on 26 June that all roads which could be seen behind the Ottoman front line, were "beaten tracks," with the main Gaza to Saba road "four camels" wide. They also noted the railway line ran almost parallel to the Wadi Ghazzeh from Abu Irgeig, to a small Wadi crossed by a viaduct, before continuing on to the Wadi Imleih.

The 3rd Division of Kress von Kressenstein's Fourth Army, was deployed to defend Gaza and the mutually supporting defences stretching from Samson's Ridge 2 miles (3.2 km) south of Gaza to Outpost Hill, on to the south eastern end of Ali Muntar Ridge to Khashm el Bir, Khashm Sihan and Tank Redoubt near the road to Beersheba. From that point the fortified Ottoman defences continuing along the Gaza to Beersheba road, were held by the 53rd Division while the 79th Regiment defended fortified works which linked with two battalions of the 16th Division holding Tel el Sheria, 15 miles (24 km) from Gaza and half way along the defensive line, while the Ottoman cavalry division was deployed near Huj, 10 miles (16 km) east of Gaza.

EEF

The EEF's strength, which could have supported an advance into Palestine before the two battles for Gaza, had been decimated. The 52nd (Lowland), the 53rd (Welsh) and the 54th (East Anglian) Divisions, which had been reported before the first battle, to be about 1,500 below establishment, lost a further 10,000 casualties during the two battles. Three months later, they would still be 5,150 infantry and 400 Yeomanry below strength.

Permanent defences were constructed from the sea at Gaza to Shellal on the Wadi Ghazzeh. From Shellal the lightly entrenched line extended to El Gamli, before continuing south 7 miles (11 km) to Tel el Fara. The western sector stretching almost to Tel el Jemmi, were strongly entrenched and wired, and defended by infantry. Desert Column was responsible for outposts and patrols in the open plain stretching east and south on the eastern flank. During outposts and patrols they harassed Ottoman forces at every opportunity, while wells and cisterns were mapped.

The open eastern flank was dominated by the Wadi Ghazzeh, which could only be crossed at four places, apart from along the beach on the Mediterranean coast. These were the main Deir el Belah to Gaza road crossing, the Tel el Jemmi crossing which had been used during the first battle of Gaza, the Shellal crossing on the Khan Yunis to Beersheba road, and the Tel el Fara crossing on the Rafa to Beersheba road. Difficulties of crossing elsewhere along the wadi, was due to the 50–60 feet (15–18 m) perpendicular banks cut into the Gaza–Beersheba plain, by flooding water two or three times a year. During the stalemate numerous additional crossings were constructed.

Views across the open eastern flank were possible from the top of the "curiously shaped heaps of broken earth" near Shellal. And two tels, indicating possible sites of ancient cities, stood high above the plain also provided excellent views. The flat topped, spectacular Tel el Jemmi with its perpendicular sides, one side dropping into the Wadi Ghazzeh, could be seen for miles. It had been used as a lookout during the first battle of Gaza. Tel el Fara on the Rafa to Beersheba road, was also a flat topped prominence with conical sides 7 miles (11 km) further south, was about 16 miles (26 km) inland from the coast in about the centre of the Gaza to Beersheba front line. This large mound also near the Wadi Ghazzeh and Shellal, thought to have been built by the crusaders in the 13th century as an observation post, gave "uninterrupted view for several miles northward and eastward." At the base of Tel el Fara huge stone buttresses and several courses of cut stone could be seen at water level.

To the west of the Wadi Ghazzeh a reserve line along the old battle line was held by one infantry brigade. To the east of the Wadi Ghazzeh, the front line consisting of 25 redoubts was manned by one platoon in each redoubt, except redoubts 2, 11 and 12 which had two platoons each. These redoubts covered by wire entanglements with wire between them, formed the firing line between Gamli and Hiseia (not to be confused with Hareira behind the Ottoman lines south of Sheria) 12,000 yards (11,000 m) to the north. In addition, the front line was strengthened by a support line of trenches, located 300 yards (270 m) behind the firing line along the east bank of the Wadi Ghazzeh. The section of trenches from Hiseia to Tel el Fara was dug by the Anzac Mounted Division while the section from Tel el Fara to Gamli was dug by the Imperial Mounted Division. Continuous wire entanglements with gaps for main roads etc. stretched for 11,000 yards (10,000 m) south. This battle line was held by one infantry division, which deployed in the front line one brigade and one artillery brigade, located along the west bank of the Wadi Ghazzeh in position from which the artillery could "sweep the ground in front of the battle line."

Attacks were to be resisted strongly, each garrison of front line infantry were to be reinforced from the support line in sufficient numbers to replace casualties. If a redoubt was lost, it was to be retaken "at once," either by a bombing attack or an assault across the open. Chetwode criticised Chauvel for ordering the mounted units to dig trenches, considering trenches "a needless waste of mounted troops mobility."

Chauvel's Desert Column became responsible for the open eastern flank which extended the front line across No-Man's-Land to the south–west of Beersheba. "The Column Commander wishes to emphasise the necessity for the most vigorous aggressive action and to remind all commanders that their horses enable them to get quickly to the flank of the enemy - which should be the sole object in any operation." When ordered the Imperial Mounted Division in reserve, was to saddle up at once and move to the road junction 1 mile (1.6 km) south of el Melek where orders would be received from Desert Column headquarters. Desert Column headquarters was to also move forward. It is very important that mounted units be engaged as far as possible to the east or to the south. Every effort should be made to make the Um Siri to El Buqqar line untenable for the attackers and at every encounter, the Ottoman cavalry was to be "severely dealt with."

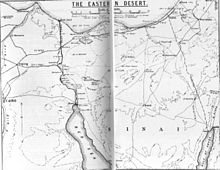

Reconnaissance aircraft worked from April to provide aerial photographs to update and correct existing maps, the best of which had been produced in 1881 by Lieutenant H.H. Kitchener, R.E., and Lieutenant Conder for the Palestine Exploration Fund. The Royal Flying Corps surveyed hundreds of square miles, taking accurate comprehensive aerial photographs of the Gaza to Beersheba line which were used by the Royal Engineers, Army Headquarters' survey companies to produce constantly revised maps showing changes to the Ottoman defences revealed during daily reconnaissances. Changes were also immediately reported to the commander of the area concerned.

Conditions

The conditions suffered by the EEF, as they held their front line across the northern edge of the desert, were similar to those suffered by the Ottoman Army. These two forces were both camped in the open during the summer, when serious food shortages, and the prevalence of sand-fly fever a debilitating illness, were made almost intolerable, by the regular hot desert winds known as khamsin which swept off the Negev Desert.

... the summer following the Gaza battles took its toll . The inescapable heat, frequent khamsins, the ever–present dust, the struggle against the flies and lice, the boredom, from which danger itself was a relief, the monotony of the diet – all combined to wear down the condition of the army. In the Light Horse there were few who did not suffer from septic sores; sandfly fever was rife; one RMO, after examining the men of his regiment, concluded that one in three was suffering from dilation of the heart.

— Experiences of an EEF Regimental Medical Officer

The EEF's rations were noted for their lack of variety and poor quality. When in camp, rice, peas, dates, porridge, jam, bread, meat, and bread pudding were available, while sardines, pears, chocolate, sausages, milk, café au lait, cocoa, and biscuits could be bought from army canteens. However during operations, soldiers survived for long periods on iron rations, a diet of Bully beef and army biscuits, which was only occasionally varied by cooking a stew made from tins of pressed beef and onions. Tinned stew consisting of meat and mainly turnips and carrots was available at times. Tea was drunk at every opportunity from early morning, during a break on the march, and in camp.

"Morale on the Palestine front was a problem for the Ottoman Army command," in particular the Arab units were "depressed" making them "vulnerable to enemy propaganda." Low Ottoman morale was blamed on logistical problems, which created shortages of food and water during the "terribly hot" summer of 1917, when "ostal, recreational and health services were particularly deficient and desertion plagued units sent to the desert."

Dust

The fine dust found around Gaza, was considered worse than the soft heavy sand and sand storms which filled eyes, ears, noses and mouths, with sand and hit the skin like red-hot needles. It was stirred by a sea breeze which began at about 10:00 from the west or north–west, which continued blowing until dark. During this time the soldiers breathed dust, ate dust and wrapped themselves in dust to sleep in their bivouacs.

The area behind the front line was subject to constant traffic, which broke up the surface, so all roads and tracks in the region became 12 inches (30 cm) or more deep with very fine dust. This dust lifted, even in light wind, to cover everything moving in a white dust cloud. As this cloud on the alluvial plain was an accurate indicator of troop movements, no offensive marches were made during daylight. "The dust raised by the horses is awful and meals are a tribulation."

With 30,000 troops in a limited area of light clay soil for the dry summer, steps were taken to manage the dust problem. In the vicinity of camps, all traffic was restricted to certain roads main roads and tracks, were swept bare and wire netting pegged down by Egyptian Labour Corps personnel. The heaps of dust at the edges of the roads, were formed into a "curb" and along these roads, boards were placed to indicate the way ahead. On a march, a London infantryman "tramped, perspiring freely, the dust that rose about us clinging to our moist faces and bare knees until we presented a most humourous spectacle."

Septic sores

Septic sores, which had been widespread during the Gallipoli Campaign, became common again during the summer of 1917. In July, 22 per cent of the Anzac Mounted Division was suffering from these sores, which increased in August. They were blamed mainly on a poor diet, which lacked variety, and vegetables. The lack of fresh vegetables, unclean water, and mosquito bites also contributed to the prevalence of septic sores, but flies were the main reason minor cuts and scratches became septic. These sores, which took the form of superficial ulcerations on the surface of the skin, often occurred following a slight injury on the hands. They were painful and hard to treat except by antiseptics, which was "hardly practicable in the field." The majority of the men suffering the sores on hands or faces had to wear bandaged, which "had a lowering and irritating effect upon the men." After the advance in November 1917 to the Jaffa and Ramleh region, where oranges were grown and easily obtained, the septic sores cleared up.

Medical support

The daily "Sick Parade" of the 4th Light Horse Field Ambulance, was carried out in the Tent Division by the duty medical officer (MO) with a staff sergeant assisting, when immediate treatment in the form of pills, dressings etc. was prescribed. The pills, handed out at once and normally taken on the spot, were identified by number, so the MO might say, "Two number 3 and one number 9." The Number Nine, pills became famous in many jokes: "The pill that will" and "Never known to fail!" Septic sores, boils, cuts, bruises, abrasions, sore eyes, sprained ankles, damaged hands and feet and etc. were dressed by the hospital staff. The MO would then decide to return the patient to his unit, admit him for a day or two to the Field Hospital, or evacuate him to hospital.

The Tent Division also provided immediate treatment for the wounded, redressing all wounds, and performing emergency surgery. The division ran the Field Hospital consisting of between one and four hospital tents, each accommodating up to 14 patients, where men lay on mattresses either on the ground or on light, wicker supports or on stretchers.

Delousing

The daylight hours were filled with fleas, lice, flies, mice and delousing. "Every morning and whenever there is a spare minute, everyone takes off their shirts and opens their trousers to hunt for lice ... This louse hunting is quite a part of life." One triumph was recorded, "Bill I've had a regular Melbourne Cup Day. I've turned my bally breeches inside out and outside in 45 blithering times and I have broken the blighters little hearts." On the King's birthday, 3 June the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade marched to Khan Yunis, where a steam disinfecting plant on the railway had been set up to clean their clothes.

Washing

The soldiers were also given opportunities to wash themselves with between three pints and two gallons of water. On 8 May ablutions parades were conducted by the 3rd Light Horse Brigade near the horse troughs, where 500 men were each issued with two gallons of water, to wash themselves and their clothes. A further 500 men attended ablution parade the following day. On 28 August the 4th Light Horse Brigade conducted an "ablution" parade while at Abasan. The men were given the whole day to wash their clothes, and bath themselves, a special area being set aside where tarpaulins covered a depression in the ground. Each regiment took its turn to wash in two gallons of water per man, drawn by camels, "which is ample ... It is found to be a good scheme."

A hole is scooped in the sand & the ground sheet spread over it & pressed down into the hollow, into this is poured about 3 pints of water, then stripping to the buff we do the best we can for ourselves, clad only in a sun helmet.

— J. O Evans 2/16th London Regiment (Queen's Westminster Rifles), 179th Brigade, 60th (London) Division

Water

The open low-lying country occupied by the EEF, was cut by deep wadis which were usually dry. These wide water courses with high banks on both sides contained many pools of good water. In the Wadi Ghazzeh 3,000 feet (910 m) of watering troughs were constructed for horses and camels. Water was also available on the eastern bank of the Wadi Ghazzeh at Shellal, where a gushing spring of salty but clear water, gave the troops who regularly drank it "stomach troubles." The remains of large Roman stone cisterns were located nearby.

Khan Yunas wells produced 100,000 gallons of water a day for the EEF. The springs at Esani and Shellal were developed to give about 14,000 gallons an hour, and 500,000 gallons were stored in a natural rock basin. The wells at Deir el Belah were connected up with the trenches south of Gaza. Pumping stations were erected and deep bore wells sunk at intervals.

The pumping plant at Qantara supplied 600,000 gallons each day to Romani where 100,000 gallons were required by the town and the railway. The pumping plant at Romani supplied 480,000 to El Abd where 75,000 gallons were required by the town and the troops stationed there. The pumping plant at El Abd pumped 405,000 gallons to Mazar where 75,000 gallons were required by the railway and troops. The pumping plant at Mazar pumped 330,000 gallons to El Arish where 100,000 gallons were required by the railway and troops. El Arish distributed 230,000 gallons to the area east of the town while 100,000 gallons were shipped by railway to Deir el Belah. The pumping plant at El Arish pumped 130,000 gallons on to Rafa where 93,500 gallons were required for the railway, leaving 36,500 gallons which reached pipehead. On 1 May 1917 the water pipe-line reached Abasan el Kebir making it possible to establish a training and staging area nearby.

A pipeline was laid from Shellal to Imara and pumps installed, while the pipeline from Qantara was connected up with Shellal where an area was established, where 200 fantasses could be filled and loaded onto camels. Extra water piping, canvas water tanks, and watering troughs were stockpiled ready for the advance.

Postal services

The AIF Army Postal Service provided mail and telegraphic services, to link the forces in the field, with the civil postal and telegraphic services. Arrangements were made with the Postmaster General’s Department in Australia to sort mails into unit lots, and a base post office was established in Cairo, with another in Alexandria. Field post offices in Egypt normally delivered mail, transacted money orders, parcel post and registered mail. However, during the summer of 1917 when unrestricted German submarine warfare was attacking shipping particularly in the Mediterranean Sea, British supplies were threatened and the mails were dislocated. After a khamsin, Duguid noted on 20 May, "It is in orders that another mail has been lost at sea. Letters written about the end of April. That is the second mail gone in the one month."

Rest camp

During leave on the "Palestine Riviera," Private John Bateman Beer, 2/22nd London Regiment, 181st Brigade, 60th Division, wrote home describing the luxury of having several days to "lounge about at one's leisure & it was quite a treat to go to bed in pyjamas in a Bell Tent near the sea ... a tent nowadays being quite a high form of living, especially after living out in the open, in the desert with a shortage of water." He enjoyed having "a band to play to us during the day & evening, and also concert parties to entertain us. A library is at our disposal & bathing ad–lib." While at rest camp, competition sports included tug–of-war, boxing, wrestling on horses and camels, rugby, and soccer. Football was also very popular being played from France to Mesopotamia to Palestine, while horse and camel racing including betting, took place on racecourses during leave. On 6 September 67 troopers marched out from the 4th Light Horse Brigade on their way to the Rest Camp at Port Said.

EEF operations, April to June

Small scale ground and air attacks were made on the opposing trenches, while regular mounted patrols were carried out on the open eastern flank.

Trench warfare

"umerous raids on the pattern of those familiar on the Western Front" were carried out. However it was necessary to conduct almost all activities at night because of the intense daytime temperatures. Between 10:00 and 16:00 "the heat produced what the men called a 'mirage,' and rifle fire under such conditions was apt to be erratic ... By a sort of natural agreement, both sides shut down the war until the hours of dusk and darkness." Then trenches were raided and fighting under exploding star shells and flares in no man's land occurred, while repairs and improvements to trenches were made, barbed wire strung, communication trenches widened, cables buried, and gun emplacements constructed.

On 18 May EEF "offensive patrolling" began, with the bombing of Ottoman trenches on Umbrella Hill, to the west of the Rafa to Gaza road. An Ottoman attack, on a EEF post on 5 June, killed or captured an entire section of the 5th Royal Scots Fusiliers (155th Brigade, 52nd Division). This loss was "avenged" during the evening of 11 June, by the 5th Kings Own Scottish Borderers (155th Brigade), which attacked an Ottoman post on the Mediterranean shore. Here they took 12 wounded prisoner, leaving at least 50 killed, without loss to the attackers.

After a feint attack with dummy figures, which diverted Ottoman fire opposite Umbrella Hill, a "long series of raids" by the 52nd (Lowland), the 53rd (Welsh) and the 54th (East Anglian) Divisions were carried out. Although they were not all completely successful, they resulted in "the establishment of a definite British superiority in No Man's Land."

Mounted patrols

During the stalemate mounted patrols, outpost work and reconnaissances were conducted, mainly towards Hareira and Beersheba. These patrols and reconnaissances by forces up to the size of a brigade, took place day and night, when skirmishes and surprise attacks were launched, traps set for hostile patrols, and raids were made on the lines of communication. Mounted patrols were frequently attacked by Ottoman cavalry. From the height of Tel el Fara, these attacks could be seen and the shots heard, across the open country. The area was renamed "the racecourse."

With only two divisions in Desert Column at this time, the Anzac and Imperial Mounted Divisions took turns, to hold the front line. On 20 May while the Imperial Mounted Division was in reserve near Abasan el Kebir, the Anzac Mounted Division was responsible for patrolling the region from the direction of Sausage Ridge to Goz el Basal and then to the west of Goz Mabruk. The Anzac Mounted Division provided night standing patrols at important parts of the line, while one brigade held Nos. 1 to 6 defences at El Sha'uth defences, as well the El Ghabi to El Gamli entrenchments.

Immediately a hostile advance in any strength was reported, the GOC Anzac Mounted Division was to send one brigade through Goz el Basal towards Im Siri and El Buqqar and another brigade southwards towards Esani, to establish the strength of the attack and degree of seriousness. The remainder of Anzac Mounted Division, less one regiment holding the line of works El Ghabi to Gamli, was to advance at once to Jezariye to take action on the basis of the report.

Towards the end of May an attack was made on an Ottoman force protecting harvesters working in barley fields. A quick galloping skirmish, with the Ottoman cavalry and an exchange of rifle fire, drove off the harvesters and the cavalry.

Day patrols

Day patrols usually started with ‘stand-to’ at about 03:00, subsequently riding out over arid, dusty country, to patrol a designated area, before returning after dark. Outpost duty might follow the next night. During these patrols, in addition to attacks from cavalry, aerial bombing was a constant dangers.

On 24 April, a squadron of the 7th Light Horse Regiment (3rd light Horse Brigade), surrounded and captured a troop of Ottoman cavalry 5 miles (8.0 km) from Shellal. On 2 May, a patrol of the New Zealand Mounted Rifle Brigade reported gaining touch with about a squadron of hostile cavalry, while a patrol towards Sausage Ridge by the 2nd Light Horse Brigade, reported gaining touch with a hostile patrol at Munkeileh.

On 9 June the 4th Light Horse Brigade rode out to occupy a line south, southeast, east and north east of Esani, when their advanced guard forced 12 Ottoman mounted troopers out of Karm, and another 20 troopers out of Rashid Bek. A further 70 Ottoman cavalry and 10 camel men were seen 2 miles (3.2 km) south east of Rashid Bek.

Officers night patrols

Night patrols were left out in no man's land, after day patrols and longer reconnaissances, to keep watch in case of surprise attacks. They rode out guided only by a compass to establish night time listening posts, when a few men dismounted to move close up to Ottoman patrols, to listen for and note all movements. They also tested or examined parts of the Ottoman trenches and tracks in the area, identified any water sources, and verify aerial reports. These night patrols consisted of one officer and 12 other ranks. On 9 May, the 74th Division reported 300 Ottoman soldiers digging in on the west bank of the Wadi Imleih. An officers patrol from 2nd Light Horse Brigade ordered to "clear up situation" found the area "all clear" the next morning. Other officers night patrols occurred, when the all clear was reported on 12 May and 26 June.

Fortnightly mounted reconnaissances

Fortnightly reconnaissances towards Beersheba, carried out by Desert Column (subsequently Desert Mounted Corps), were conducted in force. They were seen to be valuable opportunities to become familiar with the "somewhat intricate ground towards Beersheba," on the basis of which strategies could be developed for a future attack. It was also thought that these regular, repetitious reconnaissances in force, could make the Ottoman defenders slow to recognise the real thing, when it came. Indeed these reconnaissances were regularly reported in the German press as "The enemy made a determined attack on Beersheba with about seventy squadrons supported by artillery. After heavy fighting, the hostile forces were defeated and driven right back to their original positions, having suffered important losses."

These long major operations of 36 hours duration, began on the first night, continued next day, and were completed during the following night. A division would ride out in the afternoon to arrive at dawn the next morning, when a line of outposts on high ground west of Beersheba, would be occupied. Behind this screen or outpost line, corps and divisional commanders in motor cars or on horseback, familiarised themselves with the ground. Major Hampton, commanding a squadron of Worcestershire Yeomanry, (5th Mounted Brigade, Imperial/Australian Mounted Division), noted: "It fell to the lot of my Squadron, among others, to provide protection and to act generally in the capacity of Messrs. Cook & Son."

During the day hostile shells and aerial bombing were often fired at this screen, often causing casualties from carefully registered light guns. These Ottoman guns targeted the narrow wadi crossings, where it was necessary for the troopers to move in single file, before establishing the screen on the high ground, which was also carefully registered and targeted. The majority of the local population was also hostile, and took every opportunity to fire on the EEF, with arms supplied by the Ottoman Empire. Lieutenant C.H. Perkins, Royal Buckinghamshire Hussars (6th Mounted Brigade, Imperial, Australian Mounted Division) commented, "The lack of anti–aircraft guns was also unpleasant when the dust of the cavalry moved into 'no man's land' prompted the appearance of Fritz in his German Taube planes."

Once the commanders had completed their work and withdrawn, the division rode back during the night to water the horses at Esani, on the way to Shellal. The mounted regiments often covered 70 miles (110 km) or more, during 36 sleepless hours when daytime temperatures of 110 °F (43 °C) (in the shade) were experienced, while riding through dusty, rough and rocky, desert country infested with flies.

During these long reconnaissances sappers attached to the mounted division, surveyed the whole area of No-Man's-Land, marking and improving many of the wadi Ghazzeh crossings, and developing the water supply at Esani in the Wadi Ghazzeh. They also reconnoitred the water sources at Khalasa and Asluj, subsequently repairing the damaged wells just before the offensive began.

- Problems associated with long reconnaissances in strength

While the men started with full water bottles and got one refill from regimental water-carts, during these dangerous, tedious and exhausting operations, there was no water available for the horses, from "the afternoon of the day on which the division moved out till the evening of the following day." As a result the horses lost condition and needed a week to ten days to recover, although the practice had been adopted during the stalemate, of watering the horses once a day. This was mainly because of the long distance to go for water, the heat, the dust and the flies. The horses' recovery would have also been compromised, by lack of opportunities for grazing, during the reconnaissance across barren country.

On 4 May, the GOC Imperial Mounted Division inspected the horses of the 5th Mounted Brigade, which were found to be in a "very poor and weak condition due, it is thought, to too much feeding on ripe barley and shortage of good forage." Although the Australian horses were generally "better looking horses" they "did not stand up to hardship as did the New Zealand–bread stock." The Australian light horsemen "became very good horsemasters," the New Zealand mounted riflemen were "excellent horsemen and horsemasters" and their horses were "exceptionally well–selected," while the mounted Yeomanry were mostly inexperienced. The veterinary staff of the Anzac Mounted Division, collected together knowledge gained during their advance across the Sinai Peninsula, in a small brochure on horse management published in Egypt.

After a long reconnaissance on 14 June, a conference of brigade commanders at Imperial Mounted Divisional headquarters the next day, decided to carry out minor operations with smaller formations in the future because of the heat and visibility of the large formations.

Raid to Kossaima and El Auja

A raid was conducted between 7 and 14 May, by Nos. 2 and 16 Companies of the Imperial Camel Brigade with a detachment of engineer field troop, and two motor ambulances from the Lines of Communication Defences. They rode from the Lines of Communications Defences to Kossaima and El Auja, destroying wells in the area, before capturing five Ottoman railway men.

Raid to Hafir el Auja railway

Main article: Raid on Asluj to Hafir el Auja railwayAfter the raid by the Imperial Camel Brigade, orders were issued for a raid to be conducted between 22 and 23 May, on the Ottoman railway between Asluj and Hafir el Auja. This large scale raid by Desert Column on the Ottoman railway to the south of Beersheba, was made by specially formed demolition squadrons from the Field Squadrons of the Anzac and the Imperial Mounted Divisions, with the 1st light Horse Brigade providing cover, and the remainder of the Anzac Mounted Division deployed to watch for the approach of Ottoman forces from Beersheba. The Imperial Mounted Division and the Imperial Camel Brigade were also deployed to cover the raid, which was completely successful. The demolition squadrons blew up 15 miles (24 km) of railway line as well as severely damaging a number of stone railway bridges and viaducts.

El Buqqar strategic marches on 5–7, 10 May, and 2, 6–7, 14, 24–25 June

On 5 May patrols by the New Zealand Mounted Rifle Brigade reported, having reached a line west of El Girheir to Im Siri to Kh. Khasif, when hostile posts were seen on the line near Kh. Imleih and el Buqqar. Two days later the area was reported clear of the enemy.

Patrols reported Ottoman units occupying El Buqqar, Kh. Khasif and Im Siri at night and withdrawing before EEF patrols arrived in the morning. In an attempt to capture these Ottoman units, the 3rd Light Horse Brigade (Imperial Mounted Division) and one brigade from the Anzac Mounted Division, rode out on the evening of 6 May to occupy the El Buqqar and Khasif posts, with reserve units at El Gamli. Attacks were to be made at 04:00 on 7 May, but a heavy fog before dawn obstructed the attack. "That place was well named."

On 10 May a 2,500 strong hostile column was reported on the Fara to Saba, also known as Beersheba, road 2.5 miles (4.0 km) from Saba by the RAF. A reconnaissance was carried out the next day to Goz el Basal on the Bir Saba road also known as Beersheba, and to El Buqqar. When they were 1 mile (1.6 km) east of El Buqqar, they were stopped by hostile fire. As the light horsemen withdrew they left out the usual night patrols to keep watch.

On 2 June a loud explosion was heard, and the 12th Light Horse Regiment (less one squadron but with one squadron 4th Light Horse Regiment) with two sections of Machine Gun Squadron, was sent to locate the cause. They found a large water cistern at Kh Khasif had been blown up and destroyed. On their way back they encountered Ottoman cavalry near Karm which they pushed back, until they came within range of a strongly defended Ottoman line, held by two squadrons of cavalry and 200 infantry.

A strategic march was made to El Buqqar on 6 June, when a line north of Im Siri, Beit Abu Taha and El Buqqar was established at 04:00 on 7 June. With the intention of surprising and capturing Ottoman patrols, one officer and 40 other ranks from the 9th Light Horse Regiment (3rd Light Horse Brigade) supported by a squadron of 3rd Light Horse Regiment (1st Light Horse Brigade) remained in the vicinity of Karm (also known as Qamle) overnight. This attempted ambush was unsuccessful.

After standing to at 03:30 on 14 June, the 4th Light Horse Brigade rode out at 10:00 to hold a line from Hill 680 to el Buqqar to Hill 720. As the brigade took up their positions a screen of between 150 and 200 Ottoman soldiers was established 1.5 miles (2.4 km) east of the light horse line. During the day two prisoners were captured before the brigade withdrew, arriving back at the Wadi Ghazzeh at 20:00.

On 24 June the 5th Mounted Brigade rode out, to conduct operations west of the line Hill 720 to El Buqqar to Rasid Bek, with one squadron of the 4th Light Horse Brigade covering their left flank. The next day they encountered some opposition when the Yeomanry post on Hill 300, was threatened by 100 Ottoman cavalry, and one prisoner was captured, while one man was killed and another seriously wounded by shell fire. The 4th Light Horse Regiment forced the Ottoman cavalry to withdraw back to the Wadi Imleh. At 20:00 two officers patrols from the 11th Light Horse Regiment (4th Light Horse Brigade) consisting of one officer and 12 other ranks each, rode to Point 550 north of Kasif and to .75 miles (1.21 km) south of Kasif to locate and destroy hostile posts or patrols in the area. They remained out all night, returning only when the day patrols got into position, when they reported all clear with no sign of any patrols or posts.

Aerial bombing raids

As the artillery battle diminished after the Second Battle of Gaza, aerial bombing raids increased. Many of these were carried out in moonlight, which was "almost as bright as day," when the visibility of objects from the air at night was the subject of a report issued to all Imperial Mounted Division brigades. The report, written by the Officer Commanding 5th Wing, Royal Flying Corps, noted how the "the broad outline of country" was visible and contrasting areas of light water and dark land, made the coast "unmistakable." The contrast between dark trees and white tents made them easily visible, as were sandy roads and the sandy bed of wadis even in sandy country. Lights were "isible under all conditions" and fires could "be seen from a great distance." At night movements of large forces raised very little dust and it was very difficult to recognise movement from the air, "except in the case of a close formation marching along a road and interrupting the white line of road." Every precaution was to be taken against aerial attacks. Mounted formations should adopt open formations and move off tracks or roads. Camoflaging tents with khaki and dark green paint, was suggested. "Hospitals should have a cross with red lamps, the lights now used not being sufficiently distinctive. Hospitals should not be within .25 miles (0.40 km) of justifiable targets as the red lights form a good landmark and bomb dropping from a height is apt to be inaccurate."

German air raids

After the Second Battle of Gaza, the immobile sections of the 52nd (Lowland), 53rd (Welsh), 54th (East Anglian, Anzac Mounted and Imperial Mounted Divisions' five field ambulances, returned to camp at Deir el Belah near their casualty clearing stations. During the night of 3/4 May, a hostile night-time air raid in full moonlight, bombed the Immobile Section of the 4th Light Horse Field Ambulance Hospital. "The moonlight here is almost as bright as day. A low flying plane can see the tents quite easily, even with lights out." Three patients and two field ambulance personnel were killed, two dental staff sergeants, a lieutenant and a field ambulance member were wounded.

A second air raid at 22:00 the next night, again in brilliant moonlight, flew low to drop bombs and machine gun the casualty clearing stations at Deir el Belah, which were caring for about 100 casualties. Although these medical units were clearly marked with Red Cross ground sheets, the attack killed six and wounded nine in the 3rd Light Horse Field Ambulance, while one patient was killed and four orderlies wounded in the 2nd Light Horse Field Ambulance. The next night another air raid caused 13 casualties. "The Turks are out bombing every night, while this bright moonlight lasts ... Two enemy planes came over and dropped twelve bombs. We cleared out into our funk holes, but no damage done."

An air raid on Kantara on 25 May also attempted to blow up a section of the EEF lines of communication. Hostile soldiers in an Aviatik aircraft which they landed near Salmana, were stopped from blowing up the railway line, by guards from the British West Indies Regiment.

EEF air raids

EFF aircraft retaliated by dropping four times the bombs, soon after the bombing of Kantara, and the attempt to blow up a section of the EEF lines of communication on 30 May, was answered with the bombing camps and aerodromes near Abu Hareira.

Eight EEF aircraft conducted an air raid on Jerusalem on 26 June when the Ottoman Fourth Army headquarters on the Mount of Olives was bombed. Six anti-aircraft guns were later redeployed on the Mount. As the aircraft were flying home, first the engine of a B. E. aircraft seized, followed by another near and south east of Beersheba. After successfully picking up the airmen from the first aircraft which was destroyed, the second attempted rescue led to two aircraft being wrecked and the three survivors walking across No Man's Land to the safety of a light horse outpost line. Two aircraft overflying the survivors on their walk ran out of petrol and oil near Khalasa. The pilots left their intact aircraft, hoping to return to salvage them. Three Australian Flying Corps officers walked in to Goz Mabruk post from south west of Esani at 15:00 on 26 June after their forced landings, and the 3rd Light Horse Brigade was ordered to retrieve two aircraft. The aircraft were located near Naga el Aseisi south west of Bir el Asani, and a regiment of the 5th Mounted Brigade was sent to guard the aircraft, during the night of 26/27 June. Under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Maygar, the 8th and 9th Light Horse Regiments (3rd Light Horse Brigade) with three troops from the Machine Gun Squadron, one Section Field Ambulance and detachment from the RFC, moved out from Tel el Fara at 03:30 to retrieve the aircraft on 27 June. They traveled across sand hills with areas of hard ground to take over from the regiment of the 5th Mounted Brigade at 08:00. A bag of tools and a sketch showing the places where the two machine guns, camera and ammunition had been buried near the Martinsyde, were dropped at 07:30 from an aircraft which flew out from Deir el Belah airfield. The guns, camera and ammunition had been dug up by Bedouin during the night, and both aircraft were badly damaged, except for the engines which were salvaged.

A long-distance air raid from El Arish to Ma'an, was ordered by Brigadier General W. G. H. Salmond commander of the Middle East RFC at the time of the Second Battle of Gaza, during which the three aircraft flew over 150 miles (240 km) of arid desert. The aircraft succeeded in bombing the railway station buildings and destroying material and supplies in the area before safely flying back to El Arish. A forced landing could have been fatal, if the rations and water they carried, ran out before rescue. On arrival over Ma'an, the low flying aircraft dropped 32 bombs in and around the railway station, eight bombs hit the railway engine shed damaging plant and stock, while another four bombs were dropped over the aerodrome, and two bombs damaged the barracks, killing 35 and wounding 50 Ottoman soldiers. Although they returned safely to Kuntilla north of Akaba, the aircraft had been damaged by hostile fire. The next day all three aircraft flew to Aba el Lissan, where they dropped more bombs over a large Ottoman camp, damaging tents and the horse-lines, and causing a stampede. They returned to Kuntilla before noon, having sustained more damage from hostile fire. They dropped a further 30 bombs in the afternoon, on an anti-aircraft battery which was silenced, and on Ottoman soldiers and animals, before the aircraft began their return journey back to El Arish.

Seven aircraft bombed Ramleh and a Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) squadron attacked Tulkarm in the Judean Hills on 23 June.

Aerial dog fights begin

During 1916, aerial reconnaissance patrols had most often been unaccompanied, as there had been little if any aerial disputes between the belligerents. However, just as the ground war on the Gaza to Beersheba line came to resemble trench warfare on the western front, so to did the air war over southern Palestine come to resemble that being fought over France. By April 1917 the growing concentration of forces holding established front lines, the development of associated supply dumps and lines of communications, and the need to know about these developments, fueled "intense rivalry in the air."

After the Second Battle of Gaza the German aircraft were technically superior, resulting during May in a number of EEF aircraft being shot down. Aerial reconnaissance patrols were regularly attacked, so it was necessary for all photography and artillery observation patrols to be accompanied by escort aircraft. Special patrols which eventually grew into squadrons, accompanied and protected EEF reconnaissance aircraft, attacking hostile aircraft wherever they were found, either in the air, or on the ground.

During a ground operation by two regiments of the 6th Mounted Brigade and two regiment of the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade on 16 May sent to check on 500 Ottoman cavalry seen near Kh Khasif, a Bristol Scout was shot down by an Aviatik and the pilot wounded. The pilot was brought in, and the aircraft salvaged and sent to Rafa aerodrome. On 25 June during an EEF reconnaissance patrol near Tel el Sheria, a newly arrived B. E. 12.a aircraft was shot down, behind Ottoman lines.

EEF reinforcements in May and June

After the first and second battles for Gaza, large reinforcements would be needed "to set General Murray's army, in motion again." Murray made it clear to the War Cabinet and the Imperial General Staff, early in May, that he could not invade Palestine without reinforcements. He was informed by the War Office in the same month, that he should prepare for reinforcements which would increase the EEF, to six infantry and three mounted divisions.

On 25 May a French detachment, consisting of the 5/115th Territorial Regiment, 7/1st and 9/2nd Algerian Tirailleurs with cavalry and artillery, engineers and medical units, arrived and on 13 June an Italian detachment of 500 Bersaglieri arrived at Rafa. These French and Italian contingents were attached to the EEF for "mainly political," reasons. The French had "claimed special rights in Palestine and Syria," which were acknowledge in the Sykes-Picot Agreement when Britain's claim on Palestine and France's claim on Syria were agreed. The Italian Agreement of Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne asserting Italy's claim to "hereditary ecclesiastical prerogatives ... at Jerusalem and Bethlehem," was also agreed.

The 60th (London) Division along with the 7th and 8th Mounted Brigades were transferred from Salonika and the 75th Division was formed in Egypt from battalions from India and units already in Egypt. The 60th (London) Division began to arrive on 14 June, with the 7th and 8th Mounted Brigades arriving in June and early July.

If we had been asked yesterday, 'Is it possible to discover a worse situated, a more inconvenient, or a more unholy spot in the world than your late rest camp in Macedonia?' We would have unanimously replied 'No, it cannot be possible.' Today, however, we have not only changed our minds, but we have actually found this spot, and more than that, we are encamped upon it.

— Captain R. C. Case Royal Engineers, 313th Field Company, 60th (London) Division to "my dear people," 31 July 1917.

However by July, 5,150 infantry and 400 Yeomanry reinforcements were still needed, to bring the infantry and mounted divisions back up to strength, after the casualties they had suffered during the two battles for Gaza. Anzac Mounted Division wounded who had come to the end of their treatment, were returned to the front via the Australian and New Zealand Training Depot at Moascar, after convalescence or were invalided home. The decision was made by a standing board, made up of the senior physician and senior surgeon, at No. 14 Australian General Hospital. The board had been given a short tour of the Anzac Mounted Division, so they understood the conditions at the front the men would be returned to, which improved the "efficient use of man power."

Recall of Murray

On 11 June, Murray received a telegram from the Secretary of State for War, informing him that General Edmund Allenby had been given command of the EEF, and was to replace him. There had been a lack of confidence in Murray since Romani, and the two failed Gaza battles increased his unpopularity among both the infantry, and the mounted troops.

After the war Allenby acknowledged Murray's achievements in a June 1919 despatch in which he summed up his campaigns:

I desire to express my indebtedness to my predecessor, Lieutenant–General Sir A.J. Murray, who, by his bridging of the desert between Egypt and Palestine, laid the foundations for the subsequent advances of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force. I reaped the fruits of his foresight and strategical imagination, which brought the waters of the Nile to the borders of Palestine, planned the skilful military operations by which the Turks were driven from strong positions in the desert over the frontier of Egypt, and carried a standard gauge railway to the gates of Gaza. The organisation he created, both in Sinai and in Egypt, stood all tests and formed the corner–stone of my successes.

— General Allenby on 28 June 1919

Desert Column reorganisation

Between Murray's recall in early June, and the arrival of Allenby late in June, Chetwode as commander of Eastern Force gave Chauvel as commander of Desert Column, oversight for the establishment of a new Yeomanry Mounted Division, made possible by the arrival of the 7th and 8th Mounted Brigades from Salonika.

The decision to transfer the 7th and 8th Mounted Brigades from Macedonia in May and June 1917, recognised the "value of mounted troops on this front." However in May 1917 a lieutenant in the 5th Mounted Brigade opined:

Cavalry warfare is about over I think ... They can't say we haven't done our share – we have taken every inch of ground this side of Kantara ... and I should think I have ridden on an average the whole distance at least three times – the infantry have simply followed us up.

— Lieutenant R.H. Wilson, Royal Gloucestershire Hussars Yeomanry (5th Mounted Brigade), 21 May 1917

Before Chauvel's reorganisation of Desert Column, it had consisted of the Anzac Mounted Division commanded by Chetwode, comprising the 1st and 2nd Light Horse, New Zealand Mounted Rifles and the 22nd Mounted Brigades, and the Imperial Mounted Division commanded by Hodgson, made up of the 3rd and 4th Light Horse, 5th and 6th Mounted Brigades. The two new brigades brought the total number of brigades in the EEF up to 10. There was one mounted rifle, four light horse and five mounted brigades. Chauvel reorganised them into three mounted divisions.

On 21 June, the Imperial Mounted Division became the Australian Mounted Division still commanded by Hodgson. On 26 June the 6th Mounted Brigade was transferred from the Australian Mounted Division, and the 22nd Mounted Brigade was transferred from the Anzac Mounted Division, to form, along with the recently arrived 8th Mounted Brigade, the Yeomanry Mounted Division. This new mounted division was commanded by Major General G. de S. Barrow, who had also just arrived from France. The 7th Mounted Brigade's two regiments were attached to Desert Column troops.

Desert Column was reorganised from two mounted divisions of four brigades, to three mounted divisions of three brigades:

- Anzac Mounted Division commanded by Chaytor

- 1st and 2nd Light Horse, New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigades, XXVIII Brigade RHA (18-pdrs)

- Australian (late Imperial) Mounted Division commanded by Major General H.W. Hodgson

- 3rd and 4th Light Horse, 5th Mounted Brigades, XIX Brigade RHA (18-pdrs)

- Yeomanry Mounted Division commanded by Major General Barrow.

- 6th, 8th and 22nd Mounted Brigades, XX Brigade RHA (13-pdrs). The batteries in Desert Column consisted of four guns each.

On 22 June Chetwode, commanding Eastern Force complained to the Chief of the EEF's General Staff, saying the regular troopers 'movements are "heavy" and they have no snap about them.' Further, while recognising previous successes, Anzac Mounted Division headquarters wrote to subordinate brigades on 30 July, advising that commanders needed to travel well forward, so they could be in a position to make informed decisions quickly. Commanders were discouraged from dismounting the men some distance from hostile forces, when long–range firefights could prove ineffective, and a waste of ammunition. They were also discouraged from attempts to maintain contact across an extended frontage, when gaps in the line during offensive operations by mounted formations, were not important, provided "all know the general plan and work to it under one command."

Chauvel regularly inspected all Desert Column's fighting units, rest camps, hospitals, schools and troops in training often travelling in a Ford car.

Deployment of three mounted divisions

While static trench warfare continued to be fought by infantry in the central and western sections of the entrenched lines south of Gaza, the three divisions in Desert Column were rotated each month in succession in three different areas, of the open eastern flank. While one division was deployed to aggressively defend the disputed the wide No Man's Land area by patrolling towards Hureira and Beersheba, a second division was in reserve, in training in the rear near Abasan el Kebir. These two divisions lived in bivouacs both ready to move out to battle in 30 minutes, while the third division rested on the Mediterranean coasts, at Tel el Marrakeb. The divisions were rotated every four weeks, when the front line division would march to the coast, having been relieved by the division which had been training. The rotations were necessary, to maintain the health and morale of the troops during the summer in this occupied territory, the inhabitants of which were either "indifferent or openly hostile." These rotations differed from the linear positions employed in France, which reduced the number of troops on the front line, so commanders could train and rest sections of their formations.

The strongly wired and entrenched line built from the Mediterranean Sea to Shellal and Tel el Fara on the Wadi Ghazzeh, was extended eastwards to Gamli by a lightly entrenched defensive line behind which, most of the mounted troops were concentrated to the south and south–east of Gaza. Gamli was held for a month by a mounted division, which manned the daily outposts, carried out extended patrols and conducted fortnightly long reconnaissances into No Man's Land at the end of the line. While one division was in no man's land on reconnaissance, the two other divisions covered this deployment by moving up towards Shellal and Abasan el Kebir respectively.

Rotations

On 25 May orders were received by the Anzac Mounted Division, for the 2nd Light Horse Brigade to be relieved by the 53rd (Welsh) Division, at Shauth defences on 27 May. The Anzac Mounted Division was relieved on 28 May by the Imperial Mounted Division.

move out at once ... We rode fast to Gamli crossing and straight on for 6 miles (9.7 km). Then came back to the wadi, watered and rested till 3 am next morning. Moved forward again and stood to till midday, then straight back to camp by 4 pm. Took 20 horses to Khan Yunas to pick up some reinforcements. A lot of riding and coming and going. I was pleased to get eight new men for the bearer lines. Next morning we struck camp, cleaned up and moved over to a new site on the beach, and put down horse lines. Our Immobile section has joined us, so are all together again as a complete unit.

— Hamilton, 4th Light Horse Field Ambulance

The Australian Mounted Division was relieved as supporting mounted division in the Abasan el Kebir area, by the Yeomanry Mounted Division on 21 and 22 July 1917, before marching to Tel el Marakeb.

On 6 August Desert Column issued orders for the Yeomanry Mounted Division to relieve the Anzac Mounted Division as forward division, the Australian Mounted Division to relieve the Yeomanry Mounted Division in support, while the Anzac Mounted Division rode to Tel el Marakeb. These reliefs were to be carried out on 18 August. While the Anzac Mounted Division had been in the front line from 4 July to 18 August, the division had carried out 62 minor operations including reconnaissance patrols, ambushes and raids on the railway line. During this time the New Zealand Mounted Rifle Brigade, lost two men killed and 10 wounded from shelling and bombing.

One of the many rotations of the three divisions took place on 18 September, when the Australian Mounted Division relieved the Yeomanry Mounted Division, on the outpost line. The 7th Mounted Brigade took over from the 22nd Mounted Brigade at Gamli, the 4th Light Horse took over from the 6th Mounted Brigade at Tel el Fara, and the 3rd Light Horse took over from the 8th Mounted Brigade at Shellal. The 3rd Light Horse Brigade's night standing patrols, were in position by 18:00. While the Anzac Mounted Division moved back to Abasan el Kebir from Tel el Marakeb, to take over as the reserve division on 18 September, and ten days later Allenby inspected the division.

Tel el Fara

The Imperial Mounted Division had been at Beni Sela from 1 to 26 May, with a forward headquarters at El Gamli from 7 May, before relieving the Anzac Mounted Division on 28 May. The 3rd Light Horse Brigade moved to Shellal with the rest of the Imperial Mounted Division to arrive 2 miles (3.2 km) west of Tel el Fara.

On 28 May, the 4th Light Horse Field Ambulance moved from Abasan el Kebir. As they arrived at Tel el Fara a German Air Force Taube aircraft flew over very low to drop bombs, while the anti-aircraft guns shot at it. These single propeller, fighter-bombers flown by German pilots, were effective and did a lot of damage in the Palestine region. "Taube is the German word for pigeon, but to us they are more like hawks then pigeons!"

Everyone digging funk holes all day, as ordered. Each man and his mate dig a two–man hole in the ground about four feet deep, in which to sleep or run to if the bombing is too close.

— Hamilton with 4th Light Horse Field Ambulance at Tel el Fara

The 10th Light Horse Regiment (3rd Light Horse Brigade) carried out Hotchkiss Rifle training at Shellal the following day, when the dust and flies were "very bad."

The routine at Tel el Fara was to sleep fully dressed so as to be ready to "stand to" in the dark at 03:30 until after dawn at 05:00 every morning, in case of a surprise attack and while the advanced patrol was out. Then back to sleep until 06:30.

Every officer & man including transport, cooks, batmen etc. will immediately saddle–up, nosebags will be filled and tied on saddle, men will put on equipment and be ready to move at a moments notice, ... vehicle drivers will harness horses but not inspan ... In event of attack in force ... proceed to Bir el Esani.

— Orders for Standing To, 3 June 1917

Although short handed on the horse lines, the horses were taken to water in the Wadi Ghazzeh every morning while at Tel el Fara. "Stables" occurs three times a day when the horses were groomed and fed, the manure removed and buried "to keep down flies," and sick horses were cared for.

Abasan el Kebir

When they returned from a strategic march to el Buqqar on 7 May, the 3rd Light Horse Brigade moved to bivouac at Abasan el Kebir, where the horses were watered at troughs set up at the pipe head. The mounted divisions lived here in semi-permanent bivouacs constructed from light, wooden hurdles, covered with grass mats, erected over rectangular pits dug (funk holes) in the ground which gave some protection from aerial bombing. During May, the 1st Light Horse and the New Zealand Mounted Rifle Brigades (Anzac Mounted Division), along with the Imperial Mounted Division's headquarters bivouacked near Abasan el Kebir, while the 2nd Light Horse and 22nd Mounted Brigades, with two batteries RHA and the Divisional Ammunition Column, bivouacked on the beach at Tel el Marakeb, to the west of Khan Yunis.

On 17 June the "original" horses still with the Anzac Mounted Division, which had been shipped from Australia and New Zealand, and had crossed the Suez Canal with the division in April 1916 were:

- 671 horses in the 1st Light Horse Brigade

- 742 horses in the 2nd Light Horse Brigade

- 1056 horses in the New Zealand Mounted Rifle Brigade

The brigadiers agreed the ideal horse "should be from 15 to 15.3 and as near 15 hands as possible and should be stout and cobby and if possible with plenty of blood."

During the second half of September, while the Anzac Mounted Division was at Abasan el Kebir, 600 donkeys were attached to the division. The donkeys arrived at the railway station, and after unloading the "bored-looking quadrupeds with their comical expressions and long floppy ears," they were tied together in fives for the journey. Led by one man with four led horses, three dismounted men followed shepherding the donkeys, which "travelled mostly in circles." Instead of moving along the road, the donkeys toured the countryside to eventually arrive at divisional headquarters, where they were assigned to a number of units. Seven donkeys were attached to each squadron to be ridden or led by 'spare parts.' A form of polo was played by the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade riding donkeys, and swinging walking sticks at a football. In December when the advance had reached the Judean Hills, the donkeys carried supplies over rough tracks up and down precipitous hills, to the front line troops.

Other activities carried on while at Abasan el Kebir, included on 31 August boxing and cricket. On 16 October Allenby presented medals to officers and men of the Anzac Mounted Division at Abasan el Kebir. Training was also conducted while the divisions were in reserve at Abasan el Kebir, when musketry, tactical schemes, staff rides, practice concentrations, anti–gas methods, the handling and sending of messages by carrier pigeons, and getting quickly ready to move out on operations were covered.

Tel el Marakeb

At Tel el Marakeb, about 20 miles (32 km) south of Gaza on the Mediterranean coast, the men could swim in the Mediterranean Sea and be entertained by concert parties. At the end of July the whole Australian Mounted Division surfed, played sports, sunbaked and swam the horses every day while at Tel el Marakeb. There were short foot races on the beach, obstacle races, mounted rescue races, and a mounted tug-of-war competition. "With twelve mounted men on each side, everything depends on the steadiness of the horses." Extensive trials and practices took place before the three days of heats and finals.

Chauvel inspected the 4th Light Horse Field Ambulance while they were at Tel el Marakeb in August. "The bearers, all smartly dressed stood in line, with their saddle cloths spread out on the sand in front of them. On each saddle cloth, in exactly similar position, lay each man’s full equipment of about 25 separate items all cleaned and polished up to the nines – saddles, stirrups and irons, bridles and bits, water bottles, feed bags, greatcoats, saddle bags, dixies, etc. etc." On Friday 17 August the Division moved back to El Fukhan. "Six men on leave to Port Said." The New Zealand Mounted Rifle Brigade arrived at Tel el Marakeb the next day for a fortnight on the beach before they also returned to El Fukhari near Tel el Fara.

While at Tel el Marakeb, Captain Herrick, New Zealand Mounted Rifle Brigade who was in charge of Hotchkiss gun training, redesigned the pack saddle for these guns so that it could be carried on the centre of the saddle instead of to one side. The brigade farriers reworked the pack saddles in the field to Captain Herrick's design. The brigade was still in reserve at Tel el Marakeb, when on 13 September the brigade held a rifle competition.

Ottoman Yildirim Army Group activated

Enver Pasa activated the Yildirim Army Group (also known as Thunderbolt Army Group) commanded by the German General Erich von Falkenhayn in June 1917, and reinforced it with surplus Ottoman units transferred from Galicia, Romania, and Thrace.

By July, the Ottoman force defending the Gaza to Beersheba line had increased to 151,742 rifles, 354 machine guns, and 330 artillery guns. The Germans referred to the Yildirim Army Group as Army Group F, after its commander von Falkenhayn who took command at the end of July 1917 with 65 German and nine Ottoman staff officers, which effectively cut the Ottoman officers out of the decision-making process. Germany sent the 701st, 702nd, and 703rd Pasa Infantry Battalions in the late summer and early autumn of 1917, to reinforce Yildirim Army Group, and were later consolidated into "Asia Corps."

Heavy Ottoman casualties were caused by British artillery bombardments.

Arrival of Allenby

Having decided to change the command of the EEF, Allenby was not the first choice. Jan Smuts, the South African general was in London, having recently returning from the partly successful East African Campaign, fought against the German Empire. He was Lloyd George's choice to succeed Murray, but Smuts declined because he thought the War Office would not fully support the Palestine campaign. Certainly there was some ambivalence regarding the Palestine campaign. The General Staff refused to transfer divisions from France because of the threat of more German attacks in that theater, but neither the Prime Minister Lloyd George nor the War Cabinet wanted to abandon Palestine. They saw the theater as the most likely place where the Ottoman Empire might be eliminated from the war. This would isolate the German Empire, and make British Empire forces, then serving in Mesopotamia and Palestine, available for transfer to France. Further the German submarine campaign, at its height at the time, was causing severe shortages to the British population, and the continuing flood of British Expeditionary Force casualties from the western front, threatened to undermine British public morale. A victory in Palestine, would give the Allies a successful "crusade" in the Holy Land, which would lift morale.

The War Cabinet chose General Sir Edmund Allenby, the commander of the Third Army in France, who had just "won a striking victory at Arras." He had been commissioned into the Inniskilling Dragoons in 1882, and served in colonial Africa, in the Bechuanaland (1884–5) and Zululand (1888) expeditions. By the time the South African war (1899–1902) began he was adjutant in the Third Cavalry Brigade, and at its end held the rank of major. He first met Australians during the Second Boer War when Major Allenby took command of a squadron of New South Wales Lancers outside Bloemfontein. Between 1910 and 1914 he was promoted to major general and appointed Inspector General of Cavalry. At the beginning of the First World War, Major General Allenby commanded the First Cavalry Division from August to October 1914, when his division played a crucial role in the retreat from the Battle of Mons By the First Battle of Ypres in October and November 1914 he had been promoted General in command of the Cavalry Corps. He commanded the V Corps of the [[Second Army (United Kingdom) |Second Army]] at the Second Battle of Ypres in 1915, and the Third Army at the Battle of Arras in April, 1917. Before he left London for Cairo, Lloyd George asked Allenby to capture Jerusalem, "as a Christmas present for the British nation."

Allenby arrived in Egypt on 27 June and took command of the EEF at midnight on 28 June. Known as 'The Bull,' he was a "highly competent professional soldier," noted for inspiring confidence. During his frequent visits and regular inspections of units in the EEF he demonstrated a close personal interest in the men he commanded. As a result morale quickly changed from a feeling of being forgotten and neglected, to certainty that victory was possible. While Allenby made detailed and carefully preparations for future operations, he became an "overconfident risk–taker once the battle was joined." He was also known to have a violent temper. Men who had met Allenby were asked, “What's this new bloke like?” The reply was often, “He's the sort of bloke that when he tells you to do a thing you know you'd better get up and do it. He's the boss, this cove.”

Before Allenby arrived, the EEF's GHQ in Cairo had been "at a standstill" with 90 or more Generals "out of a job ... accumulated in Shepheard's Hotel where they either just existed beautifully or they made themselves busy about such jobs as reporting upon the waste of jam tins. Others became town commandants, or examiners of an army diet." During expeditions and raids, these generals were tested by Allenby to find men he could rely on. He moved the General Headquarters from Cairo to Kelab, to the north of Rafa, near Khan Yunis, where the camp was situated between two railway lines, one going to Deir el Belah and the other to Shellal.

He wrote to his wife a month after he arrived, when Allenby's son Michael was killed, on the western front:

I don't think that Michael could have been more happily placed, than in "T" Battery; and I like your idea of applying his money for the Battery's benefit. You and I will always feel a connection with it. What a wonderful and beautiful thought yours is; that Father Knapp is with our boy, and helping him to enter bravely on his new life. Oh, my brave Darling, you are the mother of a hero. Your son could have been no other. The letter he wrote to you, on the 28th of July, is a mirror in which his whole character is shown. Devotion to his work, Humour, dry but never cynical. Joy in all aspects of life. Wide interest in literature, sport, politics. All unaffected and honest. And, through all, beams his love for you. So, too, my own, your wide sympathy and thoughts for others cheers us all. God Bless you my Mabel.

— Allenby to Lady Allenby 26 August 1917

Chetwode's appreciation

Chetwode's appreciation, describing the EEF and Ottoman positions, was handed to Allenby on his arrival in Egypt. Chetwode described the strong nature of the Ottoman defences, augmented by the lack of water which prevented the EEF getting within striking distance, without "elaborate preparations." The strength of the defences, indicated the Ottoman determination to hold the line. Chetwode indicated that an attack by about the same strength as the Ottoman defenders with only slightly more artillery, would not succeed. It was also possible the Ottoman forces may attempt to push the EEF back to Rafa.

In order to make a substantial attack in force, Chetwode advised seven infantry divisions, "at full strength" and three mounted divisions, would be required. But the "poor rifle strength ... of the 52nd, 53rd and 54th, and with no drafts to keep them up, will disappear in three weeks' fighting."

Chetwode described the defensive lines from Gaza extending roughly along the Gaza to Beersheba road for 30 miles (48 km) held by about 50 Ottoman battalions, widely dispersed but with good lateral communications. Gaza was "a strong modern fortress, well entrenched and wired, with good observation and a glacis on its southern and south–eastern face across which attacking infantry could not move by day with any fair prospect of success." Then a series of "field works" mutually supported by artillery, machine guns and rifles between 1,500 to 2,000 yards (1,400 to 1,800 m) apart extended to 4 miles (6.4 km) from Beersheba. Then he detailed the defences extending from the sea to Sheikh Abbas, which were between 400 and 2,500 yards (370 and 2,290 m) from the Ottoman trenches, which continued to the south to Tel el Jemmi, "in a series of strong points," following the Wadi Ghazzeh to Karm. He described the divergence of the two front lines to the east due to the absence of water, which left a triangle of desert to the south which was absolutely flat plain, with its apex at Bir Ifteis on the Wadi Imleih 15 miles (24 km) south east of Gaza. The main Ottoman position between Khirbet Sihan and Hureira, in the center of their line extending north of the Wadi esh Sheria was located behind their front line which extended along the Gaza to Beersheba road. This front line dominated the gradually rising land to the south, so that any approach by the EEF would be "in full view, ... seriously exposed and could not be adequately supported by artillery." To the east of the triangular plain, although the ground was stony in places and cut by wadis, it rose gradually towards Beersheba, and was suitable for an attack by "all arms." However the only water in the area not covered by Ottoman defences, was at Esani on the Wadi Ghazzeh 7 miles (11 km) south east of Karm.

He described improvements to the Ottoman lines of communication, which could in the future, support 60 to 70 battalions along the front line. Chetwode also noted that the capture of the Gaza to Beersheba line would in itself, be of little value. A slight withdrawal would shorten their lines of communication, water would be less of a problem, and the Ottoman forces had selected and partially prepared strong fall back positions.

Chetwode pointed out that the EEF, had no way of easily transporting supplies forward, to advancing troops. There was no river system as in Mesopotamia to support a quick advance, although the Mediterranean Sea could easily transport ships, there were difficulties of landing supplies on open beaches, particularly in winter when such operations could be "precarious and unreliable." Further there were no roads from the coast suitable for the use of mechanical transport. The railway offered the best method of quick reliable transportation of supplies.