| Revision as of 09:01, 2 June 2006 view sourceRuud Koot (talk | contribs)31,416 edits stop changing the quote to fit your purposes, both of you← Previous edit | Revision as of 12:41, 2 June 2006 view source CltFn (talk | contribs)5,944 edits →Biography: If any inferences from the preface is original research then we shall omit itNext edit → | ||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

| His name is often given as either '''{{Unicode|Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Ḵwārizmī}}''' “Father of Abdullah, Muhammad, son of Moses, native of ]” (Arabic: {{ar|أبو عبد الله محمد بن موسى الخوارزمي}}) or '''{{Unicode|Abū Ǧaʿfar Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Ḵwārizmī}}''' (Arabic: أبو جعفر محمد بن موسى الخوارزمي), possibly because it is mistaken with that of {{unicode|]}}.<ref>M. Dunlop. ''{{unicode|Muḥammad b. Mūsā al-Khwārizmī}}''. JRAS 1943 p. 248-250).</ref> | His name is often given as either '''{{Unicode|Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Ḵwārizmī}}''' “Father of Abdullah, Muhammad, son of Moses, native of ]” (Arabic: {{ar|أبو عبد الله محمد بن موسى الخوارزمي}}) or '''{{Unicode|Abū Ǧaʿfar Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Ḵwārizmī}}''' (Arabic: أبو جعفر محمد بن موسى الخوارزمي), possibly because it is mistaken with that of {{unicode|]}}.<ref>M. Dunlop. ''{{unicode|Muḥammad b. Mūsā al-Khwārizmī}}''. JRAS 1943 p. 248-250).</ref> | ||

| The ] ] gave his name as Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwārizmī al-Majousi al-Katarbali (Arabic: {{ar|محمد بن موسى الخوارزميّ المجوسيّ القطربّليّ}}). The ] ''al-Qutrubbulli'' indicates he might instead have came from ], a small town near ]. According to ] "The epithet ''al-Majusi'' suggesting that he was an adherent of the ] religion. However, |

The ] ] gave his name as Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwārizmī al-Majousi al-Katarbali (Arabic: {{ar|محمد بن موسى الخوارزميّ المجوسيّ القطربّليّ}}). The ] ''al-Qutrubbulli'' indicates he might instead have came from ], a small town near ]. According to ] "The epithet ''al-Majusi'' suggesting that he was an adherent of the ] religion. However, some sources have suggested that al-Khwārizmī was a ] but the fact that he practiced astrology which is forbidden in Islam puts this into question. .<ref>G. Toomer. ''Dictionary of Scientific Biography''. (New York 1970-1990).</ref> | ||

| In ]'s ''Kitāb al-Fihrist'' we find a short biography on al-Khwārizmī, together with a list the books he wrote. Al-Khwārizmī accomplished most of his work in the period between 813 and 833. After the ], Baghdad became the centre of scientific studies and trade, and many merchants and scientists, from as far as China and India traveled to this city--as such apparently so did Al-Khwārizmī. He worked in Baghdad as a scholar at the ] established by ] ], where he studied and translated Greek scientific manuscripts. | In ]'s ''Kitāb al-Fihrist'' we find a short biography on al-Khwārizmī, together with a list the books he wrote. Al-Khwārizmī accomplished most of his work in the period between 813 and 833. After the ], Baghdad became the centre of scientific studies and trade, and many merchants and scientists, from as far as China and India traveled to this city--as such apparently so did Al-Khwārizmī. He worked in Baghdad as a scholar at the ] established by ] ], where he studied and translated Greek scientific manuscripts. | ||

Revision as of 12:41, 2 June 2006

"Al-Khwarizmi" redirects here. For other uses, see Al-Khwarizmi (disambiguation).Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī (Arabic: Template:Ar) was a Persian mathematician, astronomer, astrologer and geographer. He was born around 780, in either Khwarizm or Baghdad, and died around 850.

He was the author of al-Kitāb al-muḵtaṣar fī ḥisāb al-ǧabr wa-al-muqābala, the first book on the systematic solution of linear and quadratic equations. Consequently he is considered to be the father of algebra, a title he shares with Diophantus. The word algebra is derived from al-ǧabr, one of the two operations used to solve quadratic equations, as described in his book. Algoritmi de numero Indorum, the Latin translation of his other major work on the Indian numerals, introduced the positional number system and the number zero to the Western world in the 12th century. The words algorism and algorithm stem from Algoritmi, the Latinization of his name. His name is also the origin of the Spanish word guarismo, meaning digit.

Biography

Few details about al-Khwārizmī's life are known, it is not even certain where he was born. His name indicates he might have came from Khwarizm (Khiva) in the Khorasan province of the Sassanid Persian Empire (now Xorazm Province of Uzbekistan).

His name is often given as either Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Ḵwārizmī “Father of Abdullah, Muhammad, son of Moses, native of Khwārizm” (Arabic: Template:Ar) or Abū Ǧaʿfar Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Ḵwārizmī (Arabic: أبو جعفر محمد بن موسى الخوارزمي), possibly because it is mistaken with that of Ǧaʿfar Muḥammad ibn Mūsā ibn Šākir.

The historian al-Tabari gave his name as Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwārizmī al-Majousi al-Katarbali (Arabic: Template:Ar). The epithet al-Qutrubbulli indicates he might instead have came from Qutrubbull, a small town near Baghdad. According to G. Toomer "The epithet al-Majusi suggesting that he was an adherent of the Zoroastrian religion. However, some sources have suggested that al-Khwārizmī was a Muslim but the fact that he practiced astrology which is forbidden in Islam puts this into question. .

In Muḥammad ibn Isḥāq ibn al-Nadīm's Kitāb al-Fihrist we find a short biography on al-Khwārizmī, together with a list the books he wrote. Al-Khwārizmī accomplished most of his work in the period between 813 and 833. After the Islamic conquest of Persia, Baghdad became the centre of scientific studies and trade, and many merchants and scientists, from as far as China and India traveled to this city--as such apparently so did Al-Khwārizmī. He worked in Baghdad as a scholar at the House of Wisdom established by Caliph al-Maʾmūn, where he studied and translated Greek scientific manuscripts.

Contributions

His major contributions to Islamic mathematics, astronomy, astrology, geography and cartography provided foundations for later and even more widespread innovation in algebra, trigonometry, and his other areas of interest. His systematic and logical approach to solving linear and quadratic equations gave shape to the discipline of algebra, a word that is derived from the name of his 830 book on the subject, al-Kitab al-mukhtasar fi hisab al-jabr wa'l-muqabala (الكتاب المختصر في حساب الجبر والمقابلة) or: "The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing". The book was first translated into Latin in the twelfth century.

His book On the Calculation with Hindu Numerals written about 825, was principally responsible for the diffusion of the Indian system of numeration in the Middle-East and then Europe. This book also translated into Latin in the twelfth century, as Algoritmi de numero Indorum. From the name of the author, rendered in Latin as algoritmi, originated the term algorithm.

Some of his contributions were based on earlier Persian and Babylonian Astronomy, Indian numbers, and Greek sources.

Al-Khwārizmī systematized and corrected Ptolemy's data in geography as regards to Africa and the Middle east. Another major book was his Kitab surat al-ard ("The Image of the Earth"; translated as Geography), which presented the coordinates of localities in the known world based, ultimately, on those in the Geography of Ptolemy but with improved values for the length of the Mediterranean Sea and the location of cities in Asia and Africa.

He also assisted in the construction of a world map for the caliph al-Ma'mun and participated in a project to determine the circumference of the Earth, supervising the work of 70 geographers to create the map of the then "known world".

When his work was copied and transferred to Europe through Latin translations, it had a profound impact on the advancement of basic mathematics in Europe. He also wrote on mechanical devices like the astrolabe and sundial.

Algebra

Main article: The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancingal-Kitāb al-muḵtaṣar fī ḥisāb al-ǧabr wa-al-muqābala (Arabic: الكتاب المختصر في حساب الجبر والمقابلة “The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing”) is a mathematical book written approximately 830 AD.

The book is considered to have defined algebra. The word algebra is derived from the name of one of the basic operations with equations (al-ǧabr) described in this book. The book was translated in Latin as Liber algebrae et almucabala by Robert of Chester in Segovia, 1145, hence "algebra", and also by Gerard of Cremona.

Al-Khwārizmī's method of solving linear and quadratic equations worked by first reducing the equation to one of six standard forms (where b and c are positive integers)

- squares equal roots (x = bx)

- squares equal number (x = c)

- roots equal number (bx = c)

- squares and roots equal number (x + bx = c)

- squares and number equal roots (x + c = bx)

- roots and number equal squares (bx + c = x)

by dividing out the cooeficient of the square and using the two operations al-ǧabr (Arabic: الجبر “restoring” or “completion”) and al-muqābala ("balancing"). Al-ǧabr is the process of removing negative units, roots and squares from the equation by adding the same quantity to each side. For example, x = 40x - 4x is reduced to 5x = 40x. Al-muqābala is the process of bringing quantities of the same type to the same side of the equation. For example, x+14 = x+5 is reduced to x+9 = x.

Several authors have published texts under the name of Kitāb al-ǧabr wa-l-muqābala, including Abū Ḥanīfa al-Dīnawarī, Abū Kāmil (Rasāla fi al-ǧabr wa-al-muqābala), Abū Muḥammad al-ʿAdlī, Abū Yūsuf al-Miṣṣīṣī, Ibn Turk, Sind ibn ʿAlī, Sahl ibn Bišr (author uncertain)), and Šarafaddīn al-Ṭūsī.

Arithmetic

Algoritmi de numero Indorum ("al-Khwārizmī on the Hindu Art of Reckoning") on Arithmetic, which survived in a Latin translation but was lost in the original Arabic. The translation was most likely done in the 12th century by Adelard of Bath, who had also translated the astronomical tables in 1126. The original Arabic title was possibly Kitāb al-Ǧamʿ wa-al-tafrīq bi-ḥisāb al-Hind.

| This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . |

Geography

Al-Khwārizmī's third major work is his Kitāb ṣūrat al-Arḍ (Arabic: كتاب صورة الأرض "Book on the appearance of the Earth" or "The image of the Earth" translated as Geography), which was finished in 833. It is a revised and completed version of Ptolemy's Geography, consisting of a list of 2402 coordinates of cities and other geographical features following a general introduction.

There is only one surviving copy of Kitāb ṣūrat al-Arḍ, which is kept at the Strasbourg University Library. A Latin translation is kept at the Biblioteca Nacional de España in Madrid. The complete title translates as Book of the appearance of the Earth, with its cities, mountains, seas, all the islands and rivers, written by Abu Ja'far Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwārizmī, according to the geographical treatise written by Ptolemy the Claudian.

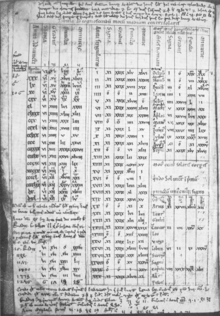

The book opens with the list of latitudes and longitudes, in order of "weather zones", that is to say in blocks of latitudes and, in each weather zone, by order of longitude. As Paul Gallez points out, this excellent system allows us to deduce many latitudes and longitudes where the only document in our possession is in such a bad condition as to make it practically illegible.

Neither the Arabic copy nor the Latin translation include the map of the world itself, however Hubert Daunicht was able to reconstruct the missing map from the list of coordinates. Daunicht read the latitudes and longitudes of the coastal points in the manuscript, or deduces them from the context where they were not legible. He transferred the points onto graph paper and connected them with straight lines, obtaining an approximation of the coastline as it was on the original map. He then does the same for the rivers and towns.

One of the corrections which al-Khwārizmī made in Ptolemy's work is the reduction of the latitude of the Mediterranean from 62° to 52° when, in actual fact, it should be only 42°. The Arab opts for the same zero meridian as Ptolemy, that of the Canaries. The amount of inhabited land extends over 180°.

The majority of the placenames used by al-Khwārizmī match those of Ptolemy, Martellus and Behaim. The general shape of the coastline is the same between Taprobane and Cattigara. The Atlantic coast of the Dragon's Tail, which does not exist in Ptolemy's map, is traced in very little detail on al-Khwārizmī's map, but is clear and precise on the Martellus map and on the later Behaim version.

Astronomy

Al-Khwārizmī's Zīǧ ("astronomical tables") is a work consisting of approximatly 37 chapters on calendrical and astronomical calculations and 116 tables with calendrical, astronomical and astrological data, as well as a table a sine values.

The original Arabic version (written around 820) is lost, but four manuscripts of a Latin translation have survived and are kept at the Bibliothèque publique (Chartres), the Bibliothèque Mazarine (Paris), the Bibliotheca Nacional (Madrid) and the Bodleian Library (Oxford). The Latin translation is assumed to have been done by Adelard of Bath and completed January 26, 1126. It is based on a version of al-Khwārizmī's Zīǧ by the Spanish astronomer Maslama al-Maǧrītī.

Other works

Al-Khwārizmī has written several other works including Risāla fi istiḵrāǧ ta’rīḵ al-Yahūd on the Jewish calendar, as well as books on using and constructing the astrolabe. Ibn al-Nadim in his Kitab al-Fihrist (an index of Arabic books) also mentions Kitāb ar-Ruḵāma(t) (the book on sundials) and Kitab al-Tarikh (the book of history) but the two have been lost.

See also

- Al-Khwarizmi (crater) — A crater on the far side of the moon named after al-Khwārizmī.

- Khwarizmi International Award

References

{{{2}}}

- Jeffrey A. Oaks. Was al-Khwarizmi an applied algebraist?; Jan P. Hogendijk. al-Khwarzimi. Pythagoras 38 (1998) no. 2, pp. 4-5.

- Khwarizmi's algebra is regarded as the foundation and cornerstone of the sciences. In a sense, Khwarizmi is more entitled to be called "the father of algebra" than Diophantus because Khwarizmi is the first to teach algebra in an elementary form and for its own sake, Diophantus is primarily concerned with the theory of numbers. —Gandz pp. 263–277.

- In the foremost rank of mathematicians of all time stands Khwarizmi. He composed the oldest works on arithmetic and algebra. They were the principal source of mathematical knowledge for centuries to come in the East and the West. The work on arithmetic first introduced the Hindu numbers to Europe, as the very name algorism signifies; and the work on algebra ... gave the name to this important branch of mathematics in the European world... —A A al'Daffa.

- M. Dunlop. Muḥammad b. Mūsā al-Khwārizmī. JRAS 1943 p. 248-250).

- G. Toomer. Dictionary of Scientific Biography. (New York 1970-1990).

- Encyclopedia Britannica. al-Khwarizmi.

- O'Connor, Abraham bar Hiyya Ha-Nasi

- Julius Ruska. Zur ältesten arabischen Algebra und Rechenkunst. ISBN 3533038173.

- http://www-gap.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/HistTopics/Cartography.html

- In al-Khwārizmī's opinion, "the Claudian" indicated that Ptolemy was a descendent of the emperor Claudius.

- Hubert Daunicht. Der Osten nach der Erdkarte al-Ḫuwārizmīs : Beiträge zur historischen Geographie und Geschichte Asiens. Bonn, Universität 1968.

- Ali Abdullah al-Daffa. The Muslim contribution to mathematics (London, 1978).

- Barnabas Hughes. Robert of Chester's Latin translation of al-Khwarizmi's al-Jabr: A new critical edition. In Latin. F. Steiner Verlag Wiesbaden (1989). ISBN 3515045899.

- Rosen, Fredrick (2004-09-01). The Algebra of Mohammed Ben Musa. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1417949147.

- Donald E. Knuth, Algorithms in Modern Mathematics and Computer Science. Springer-Verlag. 1979. ISBN 0387111573.

- Donald E. Knuth, The Art of Computer Programming: Fundamental Algorithms 3rd edition. Addison-Wesley. 1997. ISBN 0-201-89683-4.

- Fuat Sezgin. Geschichte des arabischen Schrifttums. 1974, E. J. Brill, Leiden, the Netherlands.

- Jan P. Hogendijk. al-Khwarzimi. Pythagoras 38 (1998) no. 2, pp. 4-5.

- Jeffrey A. Oaks. Was al-Khwarizmi an applied algebraist?. The University of Indianapolis.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Abu Ja'far Muhammad ibn Musa Al-Khwarizmi", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Abraham bar Hiyya Ha-Nasi", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- John J. O'Connor and Edmund F. Robertson. Arabic mathematics: forgotten brilliance? at the MacTutor archive.

- Nito Verdera. South America on ancient, medieval and Renaissance maps.

- Neugebauer, O. The Astronomical Tables of al-Khwarizmi. Historisk-filosofiske Skrifter. Bind 4, nr. 2.

- R. Rashed, The development of Arabic mathematics: between arithmetic and algebra, London, 1994.

- Salomon Gandz. The sources of al-Khwarizmi's algebra. Osiris, i (1936).