| Revision as of 17:37, 23 November 2013 editTheAustinMan (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers9,104 editsm Reverted edits by 71.72.118.26 (talk) to last version by United States Man← Previous edit | Revision as of 17:49, 23 November 2013 edit undo71.72.118.26 (talk) →Tropical Storm MelissaNext edit → | ||

| Line 445: | Line 445: | ||

| {{Infobox Hurricane Small | {{Infobox Hurricane Small | ||

| |Basin=Atl | |Basin=Atl | ||

| |Image=Melissa Nov |

|Image=Melissa Nov 20 2013 1625Z.jpg | ||

| |Track=Melissa 2013 track.png | |Track=Melissa 2013 track.png | ||

| |Formed=November 18 | |Formed=November 18 | ||

Revision as of 17:49, 23 November 2013

| 2013 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | June 5, 2013 |

| Last system dissipated | Season currently active |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Humberto |

| • Maximum winds | 85 mph (140 km/h) |

| • Lowest pressure | 980 mbar (hPa; 28.94 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 14 |

| Total storms | 13 |

| Hurricanes | 2 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 0 |

| Total fatalities | 47 total |

| Total damage | At least $1.51 billion (2013 USD) |

| Related article | |

| Atlantic hurricane seasons 2011, 2012, 2013, Post-2013 | |

The 2013 Atlantic hurricane season is an ongoing annual cycle in tropical cyclogenesis. It is the first Atlantic hurricane season since 2002 to feature no hurricanes through the month of August. The season officially began on June 1 and will end on November 30. The first tropical cyclone of the year, Andrea, developed on June 5 in the Gulf of Mexico. This season continued a pattern of unusually early starting hurricane seasons – the first named storm of a season typically forms around July 9. Below average activity continued afterwards into October. The strongest tropical cyclone of the season thus far is Humberto, which peaked as a Category 1 hurricane.

All major pre-season forecasts predicted an above average season. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) predicted an above-average to potentially hyperactive season in May; this prediction was slightly scaled down with its second forecast in early August. Other forecasting agencies forecast similar seasonal activity for the season. Official forecasts for number of named storms ranged from as low as 12 storms from the Florida State University Center for Ocean-Atmospheric Prediction Studies (FSU COAPS) to as high as 20 from the NOAA.

Tropical cyclone impacts from the season so far have been widespread but relatively minimal. In early June, Andrea made landfall in the Florida Panhandle, killing three. Later in the month, Tropical Storm Barry moved across the Yucatán Peninsula and eventually into Mexico, also causing three deaths. In late August, Tropical Storm Fernand formed in the Bay of Campeche; the system brought heavy rainfall near Veracruz, killing fourteen. In mid September, Hurricane Ingrid also formed in the Bay of Campeche, bringing even more heavy rainfall to Mexico and killing 23 people. The majority of tropical cyclones during the season have remained weak and only two hurricanes formed, both in September.

Seasonal forecasts

| Source | Date | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes |

Ref |

| Average (1981–2010) | 12.1 | 6.4 | 2.7 | ||

| Record high activity | 28 | 15 | 8 | ||

| Record low activity | 4 | 2 | 0† | ||

| ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– | |||||

| TSR | December 5, 2012 | 15 | 8 | 3 | |

| TSR | April 5, 2013 | 15 | 8 | 3 | |

| WSI/TWC | April 8, 2013 | 16 | 9 | 5 | |

| CSU | April 10, 2013 | 18 | 9 | 4 | |

| NCSU | April 15, 2013 | 13–17 | 7–10 | 3–6 | |

| UKMO | May 15, 2013 | 14* | 9* | N/A | |

| NOAA | May 23, 2013 | 13–20 | 7–11 | 3–6 | |

| FSU COAPS | May 30, 2013 | 12–17 | 5–10 | N/A | |

| CSU | June 3, 2013 | 18 | 9 | 4 | |

| TSR | June 4, 2013 | 16 | 8 | 4 | |

| TSR | July 5, 2013 | 15 | 7 | 3 | |

| CSU | August 2, 2013 | 18 | 8 | 3 | |

| NOAA | August 8, 2013 | 13–19 | 6–9 | 3–5 | |

| ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– | |||||

| Actual activity |

13 | 2 | 0 | ||

| * June–November only † Most recent of several such occurrences. (See all) | |||||

In advance of, and during, each hurricane season, several forecasts of hurricane activity are issued by national meteorological services, scientific agencies, and noted hurricane experts. These include forecasters from the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)'s National Hurricane and Climate Prediction Center's, Philip J. Klotzbach, William M. Gray and their associates at Colorado State University (CSU), Tropical Storm Risk, and the United Kingdom's Met Office. The forecasts include weekly and monthly changes in significant factors that help determine the number of tropical storms, hurricanes, and major hurricanes within a particular year. As stated by NOAA and CSU, an average Atlantic hurricane season between 1981-2010 contains roughly 12 tropical storms, 6 hurricanes, 3 major hurricanes, and an Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) Index of 66-103 units. NOAA typically categorizes a season as either above-average, average, of below-average based on the cumulative ACE Index; however, the number of tropical storms, hurricanes, and major hurricanes within a hurricane season is considered occasionally as well.

Pre-season forecasts

On December 5, 2012, Tropical Storm Risk (TSR), a public consortium consisting of experts on insurance, risk management, and seasonal climate forecasting at University College London, issued an extended-range forecast predicting an above-average hurricane season. In its report, the organization called for 15.4 (±4.3) named storms, 7.7 (±2.9) hurricanes, 3.4 (±1.6) major hurricanes, and a cumulative Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) index of 134, citing the forecast for slower-than-average trade winds and warmer-than-normal sea surface temperatures. While no value was placed on the number of expected landfalls during the season, TSR stated that the landfalling ACE index was expected to be above average. Four months later, on April 5, Tropical Storm Risk issued its updated forecast, continuing to call for an above-average season with 15.2 (±4.1) named storms, 7.5 (±2.8) hurricanes, 3.4 (±1.6) major hurricanes, and an ACE index of 131; the landfalling ACE index was once again forecast to be higher than normal.

Meanwhile, on April 8, Weather Services International (WSI) issued its first forecast for the hurricane season. In its report, the organization forecasted 16 named storms, 9 hurricanes, and 5 major hurricanes, referencing above average sea surface temperatures in the Main Development Region of the Atlantic. The main forecasting uncertainty involved whether or not an El Niño develop prior to the peak of the season. On April 10, Colorado State University (CSU) issued its first forecast for the season, calling for a potentially hyperactive season with 18 named storms, 9 hurricanes, 4 major hurricanes, and an ACE index of 165. In its report, the agency stated that above-average sea surface temperatures in the MDR, below-average forecast wind shear, and the unlikeliness of an El Niño developing prior to the peak of the season would enhance tropical cyclone activity. The probabilities of a major hurricane hitting the Gulf Coast and East Coast were much above-average, while the probability of a major hurricane hitting anywhere along the USA coastline were well above-average as well.

On May 15, the United Kingdom Met Office (UKMO) issued a forecast of a slightly above-average season. It predicted 14 named storms with a 70% chance that the number would be between 10 and 18 and 9 hurricanes with a 70% chance that the number would be between 4 and 14. It also predicted an ACE index of 130 with a 70% chance that the index would be in the range 76 to 184. On May 23, 2013, NOAA issued its first seasonal outlook for the year, stating there was a 70% likelihood of 13 to 20 named storms, of which 7 to 11 could become hurricanes, including 3 to 6 major hurricanes; these ranges are greater than the seasonal average of 12 named storms, 6 hurricanes and 3 major hurricanes. The three main factors contributing to a well above-average to hyperactive hurricane season included above-average sea surface temperatures across much of the Atlantic, the absence of an El Niño in the Pacific, and the continuity of the active era since 1995. On May 30, the Florida State University Center for Ocean-Atmospheric Prediction Studies, FSU COAPS, issued its first and only prediction for the season. The organization called for 12 to 17 named storms, of which 5 to 10 would further intensify into hurricanes; no forecast was given for the number of major hurricanes. In addition, an ACE index of 135 units was forecast. The group attributed its high number of predicted storms to the recent uptick in tropical cyclone activity since 1995.

Mid-season outlooks

On June 3, Colorado State University issued its first mid-season prediction for the remainder of the year. In its report, the organization continued to predict well above-average activity, with 18 named storms, 9 hurricanes, 4 major hurricanes, and an ACE index of 165 units. The two main factors included in the report included the lack of an El Niño and warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures across much of the Atlantic. CSU stated that there was a 72% chance of at least one major hurricane impacting any stretch of the United States coastline; the chances of a major hurricane hitting the East Coast and Gulf Coast were 48% and 47%, respectively. The following day, Tropical Storm Risk issued its third forecast for the 2013 Atlantic hurricane season, calling for 16 named storms, 8 hurricanes, 4 major hurricanes, and an ACE of 134 units; this activity was predicted to be roughly 30% above the 1950-2012 long-term mean. TSR gave a 65% probability that the landfalling ACE index would be above-average. Above-average activity was forecast on the basis of slower-than-average trade winds and warm ocean temperatures. A month later, however, TSR lowered its numbers due to predicted cooler-than-average sea surface temperatures and above-average sea surface temperatures. On August 2, Colorado State University issued another update for the season. Despite lowering its numbers slightly as a result of anomalous cooling in the eastern subtropical tropical Atlantic, the organization stated that there was an above-average probability of a United States and Caribbean major hurricane landfall. Finally, on August 8, NOAA issued its second and final outlook for the season, predicting 13 to 19 named storms, 6 to 9 hurricanes, and 3 to 5 major hurricanes; these numbers were down ever so slightly from its May outlook. The agency stated a wetter-than-average western Africa and above-average sea surface temperatures in its report.

Seasonal summary

See also: Timeline of the 2013 Atlantic hurricane season

The Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) index for the season as of 05:42, 27 December 2024 (UTC) is 33.32 units.

Storms

Tropical Storm Andrea

Main article: Tropical Storm Andrea (2013)| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 5 – June 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 992 mbar (hPa) |

A broad low-pressure center formed over the southern Gulf of Mexico on June 3. The system subsequently organized at a steady pace, with increasing convection near the center. Following a reconnaissance aircraft mission into the system on June 5, it was upgraded to Tropical Storm Andrea at 1800 UTC. After formation, Andrea drifted northward and eventually accelerated northeastward in advance of an upper-level trough over the United States. Strong divergence on the right entrance region of the trough allowed the cyclone to become increasingly intense despite the poor environment, and Andrea is estimated to have attained a peak intensity of 65 mph (100 km/h) with a minimum barometric pressure of 992 mbar (29.30 inHg) while located just offshore Florida. Dry air entrainment caused the system to weaken slightly prior to landfall at 2200 UTC near Steinhatchee, Florida. Once inland, Andrea continued to accelerate northeast, tracking across Georgia and into South Carolina. At 1800 UTC on June 7, the system became extratropical as it began to interact and subsequently merged with a baroclinic zone over the state. The remnants tracked across a majority of the United States East Coast prior to being absorbed by a developing area of low pressure over Nova Scotia the following day.

Effects from the tropical cyclone were relatively minimal. The pre-cursor to Andrea produced a maximum rainfall total of 12.40 inches (315 mm) on La Capitana Mountain while totals above 8 inches (200 mm) were observed over western portions of Cuba. Widespread rainfall totals of 3 to 5 inches were observed from Florida through New England, while a maximum total of 13.94 inches (354 mm) was noted at the South Florida Water Management District station in North Miami Beach; this led to severe urban flooding in the city. A maximum storm surge of 4.55 feet (1.39 m) was observed at Cedar Key, Florida, while slightly lesser values were recorded in surrounding locations. Low-topped supercells that developed as Andrea made landfall resulted in eleven tornadoes, though all were EF0 and EF1 on the Enhanced Fujita scale. Prior to becoming a tropical cyclone, Andrea led to five tornadoes over western Cuba. A weather station in Tampa recorded a storm-maximum sustained wind of 47 mph (76 km/h) while the strongest gust observed reached 83 mph (134 km/h); this is hypothesized to have been a result of a waterspout moving onshore. Overall, the system led to one direct death and three indirect deaths.

Tropical Storm Barry

Main article: Tropical Storm Barry (2013)| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 17 – June 20 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); 1003 mbar (hPa) |

During the evening hours of June 15, the National Hurricane Center began monitoring a large area of disturbed weather in association with a tropical wave over the southwestern Caribbean Sea. Drifting west-northwest, environmental conditions were expected to be favorable for organization, but the system's proximity to land would hinder significant intensification. The system was given a Medium chance of tropical cyclone formation within 48 hours early on June 17; following data from the radar in Honduras and visible satellite animations, the disturbance was upgraded to Tropical Depression Two. Situated 60 miles (95 km) east of Monkey River Town, no further development was anticipated. Late that evening, the system moved onshore, producing heavy rainfall and gusty winds. Despite a waning structure, the NHC noted that if the system emerged into the Bay of Campeche, re-development and intensification was plausible. Midday on June 19, the storm was upgraded to a tropical storm and was named Barry, although only minimal intensification was likely due to the storm's proximity to land. Between 1200 and 1300 UTC on June 20, Barry made landfall just north of Veracruz, Mexico with winds of 45 mph (75 km/h).

Heavy rains in Honduras triggered flooding that damaged 60 homes and affected 300 people. In southern Belize, an estimated 10 in (250 mm) of rain fell in 24 hours, causing several rivers to over-top their banks. In localized regions, culverts were washed away. At least 54 people living along Hope Creek were relocated to shelters. In the Mexican state of Yucatán, wind gusts up to 48 mph (77 km/h) and heavy rains downed trees and power lines. More than 26,000 residents temporarily lost power after lightning struck a nearby power station, leading to a fire. In El Salvador, flooding left one person missing. Two people were also injured after being struck by lightning.

Tropical Storm Chantal

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 7 – July 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 1003 mbar (hPa) |

Cloudiness and thunderstorm activity in association with a tropical wave over the central Atlantic was monitored by the National Hurricane Center on July 5. Initially, further development of this feature was deemed unlikely due to poor environmental conditions. However, as it tracked westward towards a region of higher atmospheric moisture, convection began to increase over a developing low-level center. Following conventional and microwave satellite imagery the system was upgraded to Tropical Storm Chantal at 0300 UTC on July 8. Steered rapidly westward underneath the southern periphery of a well-established mid-level ridge, the system slowly organized, with a pronounced anticyclonic outflow pattern and banding features extending from the center. A reconnaissance aircraft investigating the system early on July 9 found strong flight-level winds in excess of 80–85 mph (130–135 km/h) but a surprisingly high barometric pressure of 1010 mbar (29.83 inHg). That afternoon, the system entered the eastern Caribbean Sea while continuing west-northwest. During a 24-hour period between July 9 and July 10, the forward motion of Chantal accelerated to 30 mph (55 km/h), setting a record for the fastest-moving tropical cyclone in the deep tropics on record.

Despite a large burst of convection, another reconnaissance aircraft investigating the system late on July 9 recorded very high atmospheric pressures and a weak wind field more resembling an open wave than a tropical cyclone; this is suspected to have been a result of mid-level wind shear. Surrounding buoy data revealed that a closed center no longer existed several hours later, though the NHC was able to find enough of a circulation to maintain advisories. At 2100 UTC on July 10, Chantal degenerated into an open tropical wave. Overall, the storm caused one death and less than $10 million USD in damage.

Tropical Storm Dorian

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 23 – August 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 1002 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave emerged off the African coast on July 22, and quickly showed signs of development with increasing convection. The low pressure area became better defined, with a well-defined circulation. On July 24, the NHC classified the system as Tropical Depression Four about 310 miles (500 km) west-southwest of the Cape Verde islands, by which the convection had become more concentrated. Later that day, the agency upgraded the depression to Tropical Storm Dorian, with very low wind shear and marginal water temperatures allowing for strengthening. The storm moved generally westward, steered by a strong ridge over the central Atlantic. On July 27, Dorian weakened into a tropical wave, as it was being battered by strong wind shear, and dry air was entering the center.

On August 3, the remnants of Dorian regenerated into a Tropical Depression east of Florida, only to once again degenerate into a remnant low just 12 hours later.

Tropical Storm Erin

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 15 – August 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); 1006 mbar (hPa) |

On August 13, a tropical wave, accompanied by an elongated area of low pressure and a large area of disorganized showers and thunderstorms, emerged off the west coast of Africa. The wave moved along a west-northwesterly course owing to a ridge to its north. The system quickly organized and its circulation became more defined, warranting its classification as a tropical depression early on August 15. Situated 70 mi (110 km) south of Praia, Cape Verde, tropical storm warnings were issued for the southernmost islands of the country. Deep convection continued to develop over the center and the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Erin just six hours later. Shortly thereafter, dry air became entrained in the circulation and convection waned. Operationally, Erin was briefly downgraded to a tropical depression on August 16; however, post-storm analysis indicated that it retained tropical storm intensity throughout the day.

Early on August 17, the ship British Cygnet measured 44 mph (71 km/h) winds in relation to the cyclone, and it was estimated that Erin attained its peak intensity around this time with sustained winds of 45 mph (75 km/h) and a barometric pressure of 1006 mbar (hPa; 29.71 inHg). A temporary northwesterly turn occurred around this time as the storm moved into a weakness in the ridge. Later on August 17, increasing wind shear took its toll on Erin and convection was displaced from the center. The following day, Erin degenerated into a remnant low about halfway between the Lesser Antilles and the west coast of Africa. The remnants proceeded westward in the low-level trade winds before opening up into a trough early on August 20, and ultimately dissipating several days later.

Tropical Storm Fernand

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 25 – August 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 1001 mbar (hPa) |

On August 23, a westward-moving tropical wave over the Yucatán peninsula was expected to encounter favorable conditions for development. A low pressure area soon developed over land. Early on August 25, convection formed over the center as it emerged into the Bay of Campeche. Based on satellite imagery, nearby radar observations, and surface data, the NHC designated the disturbance as Tropical Depression Six at 2100 UTC on August 25 about 50 mi (80 km) east-southeast of Veracruz. Late on August 25, the NHC upgraded the depression to Tropical Storm Fernand after a Hurricane Hunters flight observed winds of 45 mph (75 km/h). The storm intensified more, with gusts of 72 mph (117 km/h) reported at a coastal observation station. At 0445 UTC on August 26, Fernand made landfall about 25 mi (40 km) west-northwest of Veracruz with winds of 50 mph (85 km/h). The storm weakened inland while moving parallel to the coast, with a large area of thunderstorms. By late August 26, the circulation of Fernand dissipated over eastern Mexico.

Upon the storm developing on August 25, a tropical storm warning was posted along the Gulf Coast of Mexico from Veracruz northward to Tampico, which was canceled north of Barra de Nautla, Veracruz early on August 26, and discontinued after Fernand weakened to a tropical depression. Members of the Mexican Navy helped evacuate 4,000 people from their homes in the state of Veracruz. Classes in the state were closed during the storm's passage. Impact from the storm in Mexico was most severe in Veracruz, where 13 people were killed by landslides – nine in Yecuatla, three in Tuxpan, and one in Atzalán. In the city of Veracruz, heavy rainfall flooded roads, while downed trees caused power outages. In Boca del Río, flooding stranded people at a shopping plaza. Damage was reported in 19 municipalities, mostly in northern and central Veracruz. The storm damaged 457 homes and caused 4 rivers to overflow. In Oaxaca, another fatality took place after a man was swept away by a swollen river. After the storm, Veracruz governor Javier Duarte declared a state of emergency for 92 municipalities, which allowed farmers who sustained damage to receive aid.

Tropical Storm Gabrielle

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 4 – September 13 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 1003 mbar (hPa) |

During the afternoon hours of August 25, the National Hurricane Center began monitoring a tropical wave over western Africa. Tracking westward, the wave remained largely disorganized and broad in nature; nonetheless, it was assessed with a low chance of development within 48 hours on August 29. After briefly becoming less organized in the central Atlantic due to strong winds and dry air, favorable atmospheric conditions allowed for a large burst of shower and thunderstorm activity atop a broad low-level center as it neared the Lesser Antilles. Though this stormy condition waned and the NHC lowered development chances as a result, a period of development began once again as the disturbance entered the eastern Caribbean. Following data from an air force reconnaissance aircraft on September 4, the system was upgraded to Tropical Depression Seven, and operationally upgraded to Tropical Storm Gabrielle six hours later. The following morning, the system began to lose organization, perhaps a result of light wind shear; the low-level circulation became poorly defined and associated shower and thunderstorm activity largely dissipated, leading the NHC to downgrade Gabrielle to a tropical depression. Surface observations from late that afternoon revealed that the center of the storm moved ashore and dissipated over Hispaniola; advisories were ceased on the storm accordingly. In post-analysis, it was determined that Gabrielle was never a tropical storm in the Caribbean.

Despite dissipating, the remnants of Gabrielle were monitored for the potential for regeneration. Wind shear initially precluded any increase in organization, though by late on September 9, convection began to increase over a developing low-level circulation. Further development occurred over the following hours and Gabrielle was once again upgraded to a tropical storm. Characterized with a large central dense overcast-feature, data from a reconnaissance aircraft investigating the system found winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) near the center. In post-analysis, it was determined that Gabrielle peaked a bit earlier with winds of 65 mph (100 km/h). However, shear late on September 10 began to display all associated shower and thunderstorm activity east of the exposed circulation. Convection flared up again the next day but quickly waned, prompting the NHC to downgrade the system to a tropical depression. Tracking north, shower and thunderstorm activity flared up once again, and the system was upgraded to a tropical storm once again early on September 12. After maintaining this intensity for 24 hours, satellite intensity estimates prompted yet another downgrade to tropical depression intensity early the following morning. Data from a series of Advanced Scatterometer passes later this day indicated a lack of a closed low-level circulation, and Gabrielle was considered dissipated once again.

Tropical Depression Eight

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 6 – September 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min); 1009 mbar (hPa) |

On September 2, the NHC began monitoring a tropical wave over the western Caribbean Sea. Tracking west-northwestward, the wave axis entered the eastern Bay of Campeche on September 4 and shower and thunderstorm activity increased as it entered a favorable environment for development. Early on September 6, the NHC lowered the probability of development as it appeared the low-pressure system would make landfall in Mexico before further development could occur. However, an inspection of satellite imagery and surface observations revealed that the center had slowed its forward progression and was still offshore. With increased banding noted, the system was subsequently upgraded to Tropical Depression Eight. Shortly thereafter, the depression made landfall near Tampico, Mexico, where a central pressure of 1009 mbar (29.80 inHg) was recorded. The coverage and intensity of convection decreased over the coming hours and a combination of surface observations and satellite imagery indicated that the system no longer maintained a closed low; as a result, the NHC ceased advisories on the system at 0900 UTC on September 7.

Heavy rains across Tamaulipas and Veracruz triggered flooding in areas that were affected by Tropical Storm Fernand just two weeks prior. Many areas were under water once again. The most significant effects were in Veracruz where hundreds of homes were inundated. Record breaking rains in Mexico City, falling at rates of 3.3 in (84 mm) per hour, caused significant flooding. Many streets were inundated, paralyzing traffic and prompting water rescues. An estimated 20,000 people were affected by the floods and officials opened four shelters in the area.

Hurricane Humberto

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 8 – September 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min); 980 mbar (hPa) |

A vigorous tropical wave in the far eastern Atlantic emerged off Africa and quickly became a tropical depression on September 8 southeast of Cape Verde. It strengthened into a tropical storm the next morning, and became the first hurricane of the season on September 11. By 15:00 UTC on September 13, Humberto had diminished into a tropical storm. Lacking deep convection around its center for more than 24 hours, Humberto degenerated into a remnant low on September 14. Conditions became favorable for regenesis, however, and the post-tropical low regained convection near the center on September 16, becoming a tropical cyclone once again. During the next few days, Humberto turned to the north, before turning eastward on September 19. Late on September 19, the NHC issued its last advisory on Humberto, as the system degenerated into a remnant low.

As a tropical storm, Humberto brought periodic squalls to Cape Verde. The southwestern-most islands experienced wind gusts exceeding 35 mph (55 km/h) which downed several trees. Heavy rains in many areas triggered flooding that washed out roads and damaged homes, though overall impacts were considered minimal. Offshore, a freighter with a crew of six went missing amid 10 to 16 ft (3 to 5 m) swells.

Hurricane Ingrid

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 12 – September 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min); 983 mbar (hPa) |

During the pre-dawn hours of September 10, the National Hurricane Center began monitoring an area of disturbed weather over the northwestern Caribbean Sea. Tracking west-northwestward, the system entered the southern Bay of Campeche on September 12 and began to organize accordingly. Following satellite data, surface observations, and data from a reconnaissance aircraft, the disturbance was upgraded to Tropical Depression Ten at 2100 UTC that afternoon. For the 18 hours following classification, the depression did not inherently become better organized. However, a second reconnaissance mission into the system reported surface-estimated winds of 48 mph (77 km/h); the NHC upgraded the depression to Tropical Storm Ingrid as a result. Despite moderate westerly wind shear from a secondary tropical cyclone in the East Pacific, Ingrid gradually organized over warm sea surface temperatures. On September 14, an eye feature became intermittently visible on conventional satellite imagery, leading the NHC to upgrade the system to a Category 1 hurricane. Tracking generally north-northwestward, continued wind shear from nearby Manuel caused the system to appear ragged on satellite. Around 1200 UTC on September 16, Ingrid made landfall near La Pesca, Mexico, with winds of 65 mph (100 km/h). The system weakened quickly over land, becoming a tropical depression at 2100 UTC. The following morning, Ingrid dissipated over the high terrain of eastern Mexico.

Tropical Storm Jerry

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 29 – October 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1005 mbar (hPa) |

The National Hurricane Center began monitoring a large area of disturbed weather in association with a trough of low pressure over the central Atlantic on September 26. Development was expected to be slow to occur due to the disturbance's proximity to an upper-level trough. Late on September 27, satellite-derived wind data indicated the presence of a small area of low pressure. Slow development occurred over the subsequent 24 hours, with a large burst of deep convection over the center early on September 29; on this basis, the disturbance was upgraded to Tropical Depression Eleven. At the time, the system was moving northeastward due to a ridge to the east. Initially, wind shear displaced the thunderstorms from the center. On September 30, after a turn to the east and an increase in convection, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Jerry.

On October 1, the NHC anticipated Jerry would last for at least five days as a tropical cyclone, although they noted low confidence due to computer models predicting a range from hurricane to dissipation. That day, NHC upgraded the storm to winds of 50 mph (85 km/h), which would ultimately be the peak intensity. Strong wind shear and dry air affected the storm, which quickly exposed the convection from the circulation. Due to weakening steering currents, Jerry became nearly stationary. Convection increased slightly later on October 1, only to decrease the following day as it accelerated to the northeast. Early on October 3, Jerry weakened to tropical depression status after becoming devoid of convection. It degenerated into a post-tropical cyclone later that day while situated several hundred miles west-southwest of the Azores.

Tropical Storm Karen

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 3 – October 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 999 mbar (hPa) |

On September 28, an area of disturbed weather formed in the southwestern Caribbean Sea, associated with a trough. The system moved slowly to the northwest, initially remaining disorganized. On October 1, the convection became better organized around a broad low off northeast Central America. The Hurricane Hunters observed tropical storm-force winds late on October 2, but no well-defined circulation. The next day, however, the NHC initiated advisories on Tropical Storm Karen after another flight found a circulation off the north coast of the Yucatán peninsula. At that time, the agency expected the storm to intensify into a hurricane, although initially the convection was displaced by moderate wind shear. Karen quickly intensified to reach peak winds of 65 mph (100 km/h) while moving north-northwestward around the subtropical ridge. Strong shear and dry air weakened the convection, leaving the center exposed. Thunderstorms pulsed sporadically over the well-defined center, although Karen continued to weaken, deteriorating to tropical depression status early on October 6. After the circulation became less defined, the NHC discontinued advisories later that day.

While the storm was threatening the Gulf Coast, states of emergency were issued in portions of Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Florida. The mayor of the town of Grand Isle, Louisiana evacuated the island on October 4. Evacuations were also ordered in Lafourche Parish and Plaquemines Parish. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the United States Department of the Interior called back workers, furloughed because of the government shutdown, to assist state and local agencies. Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindal authorized the mobilization of the state's National Guard members to active duty.

Tropical Storm Lorenzo

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 21 – October 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1003 mbar (hPa) |

The National Hurricane Center began monitoring a weak area of low pressure about 625 mi (1005 km) southeast of Bermuda late on October 20. Development, however, was not anticipated due to unfavorable atmospheric conditions. Despite this prediction, the area of disturbed weather began to show signs of organization as shower and thunderstorm activity increased and became more organized. Following an improving convective appearance, advisories were initiated on Tropical Depression Thirteen at 1500 UTC on October 21. Tracking north-northeast around a mid-level ridge, the depression steadily intensified in a favorable upper-air environment, becoming Tropical Storm Lorenzo at 2100 UTC and peaking with winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) the following morning as a mid-level eye became visible on satellite. Following peak intensity, increased wind shear caused the low-level center to decouple from the deep convection; at 0300 UTC on October 23, Lorenzo weakened to a tropical depression and by 1500 UTC, the system lacked the organization needed to be considered a tropical cyclone. The remnants of the cyclone were mentioned in the NHC's Tropical Weather Outlook early on October 25, though redevelopment was not expected due to unfavorable conditions. However, the remnants of Lorenzo fueled the St Jude storm, which struck northern Europe with hurricane-force winds from October 27-28, 2013.

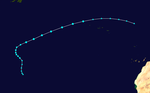

Tropical Storm Melissa

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

File:Melissa Nov 20 2013 1625Z.jpg  | |

| Duration | November 18 – November 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 980 mbar (hPa) |

Subtropical Storm Melissa formed from a tropical wave on November 18. Melissa was expected to become a tropical storm from the NHC, which it successfully did. Melissa dissipated on November 22, leaving the 2013 season very below average. Melissa stayed well out to sea, unlike Hurricane Vince.

Storm names

The following names will be used for named storms that form in the North Atlantic in 2013. Retired names, if any, will be announced by the World Meteorological Organization in the spring of 2014. The names not retired from this list will be used again in the 2019 season. This is the same list used in the 2007 season, except for Dorian, Fernand, and Nestor, which replaced Dean, Felix, and Noel respectively. The names Dorian and Fernand were used for the first time this year.

|

|

Season effects

The following table lists all of the storms that have formed in the 2013 Atlantic hurricane season. It includes their duration, names, landfall(s) (in parentheses), damages, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a wave, or a low, and all of the damage figures are in 2013 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Ref(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andrea | June 5 – June 7 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 992 | Yucatán Peninsula, Cuba, Eastern United States, Atlantic Canada | 0.04 | 4 | |||

| Barry | June 17 – June 20 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1003 | Central America (Belize), Mexico (Veracruz) | Minimal | 5 | |||

| Chantal | July 7 – July 10 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 1003 | Lesser Antilles, Puerto Rico, Hispaniola | 10 | 1 | |||

| Dorian | July 23 – August 3 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 1002 | The Bahamas, Florida | None | None | |||

| Erin | August 15 – August 18 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1006 | Cape Verde | None | None | |||

| Fernand | August 25 – August 26 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 1001 | Mexico (Veracruz) | Millions | 14 | |||

| Gabrielle | September 4 – September 13 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 1003 | Lesser Antilles, Puerto Rico, Hispaniola, Bermuda, Atlantic Canada | None | None | |||

| Eight | September 6 – September 7 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1009 | Mexico (Tamaulipas) | None | None | |||

| Humberto | September 8 – September 19 | Category 1 hurricane | 85 (140) | 980 | Cape Verde | Minimal | None | |||

| Ingrid | September 12 – September 17 | Category 1 hurricane | 85 (140) | 983 | Mexico (Tamaulipas) | 1500 | 23 | |||

| Jerry | September 29 – October 3 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1005 | None | None | None | |||

| Karen | October 3 – October 6 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 999 | Yucatán Peninsula, United States Gulf Coast | None | None | |||

| Lorenzo | October 21 – October 24 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1003 | None | None | None | |||

| Melissa | November 18 – November 22 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 980 | Azores | None | None | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 14 systems | June 5 – Currently active | 85 (140) | 980 | >1510 | 47 | |||||

See also

- List of Atlantic hurricanes

- List of Atlantic hurricane seasons

- 2013 Pacific hurricane season

- 2013 Pacific typhoon season

- 2013 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 2012–13, 2013–14

- Australian region cyclone seasons: 2012–13, 2013–14

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 2012–13, 2013–14

References

- "In 2013 Hurricane Season, a Remarkable Calm Before the Next Storm". www.businessweek.com. 2013-09-04. Retrieved 2013-09-05.

- ^ "Background Information: The North Atlantic Hurricane Season". Climate Prediction Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. August 9, 2012. Retrieved April 11, 2013.

- ^ "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved December 27, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Landsea, Chris (April 2022). "The revised Atlantic hurricane database (HURDAT2) - Chris Landsea – April 2022" (PDF). Hurricane Research Division – NOAA/AOML. Miami: Hurricane Research Division – via Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory.

- ^ Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (December 5, 2012). Extended Range Forecast for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2013 (PDF) (Report). Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- ^ Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (April 5, 2013). April Forecast Update for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2013 (PDF) (Report). Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved April 5, 2013.

- ^ Linda Maynard (April 8, 2013). WSI: Warm Tropical Atlantic Ocean Temperatures Suggest Another Active Hurricane Season (Report). Weather Services International. Retrieved April 8, 2013.

- ^ William Gray; Philip Klotzbach (April 10, 2013). Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and Landfall Strike Probability for 2013 (PDF) (Report). Colorado State University. Retrieved April 10, 2013.

- Lian Xie; et al. (April 15, 2013). 2013 Atlantic Tropical Cyclone Outlook (PDF) (Report). North Carolina State University. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

{{cite report}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ North Atlantic Tropical Storm Seasonal Forecast 2013 (Report). May 15, 2013. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ^ NOAA predicts active 2013 Atlantic hurricane season (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 23, 2013. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ^ FSU's 2013 North Atlantic hurricane forecast predicts above-average season (Report). Florida State University. May 30, 2013. Retrieved June 3, 2013.

- ^ William Gray; Phil Klotzbach (June 3, 2013). Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and Landfall Strike Probability for 2013 (PDF) (Report). Colorado State University. Retrieved June 3, 2013.

- ^ Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (June 4, 2013). July Forecast Update for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2013 (PDF) (Report). Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved July 5, 2013.

- ^ Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (July 5, 2013). July Forecast Update for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2013 (PDF) (Report). Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved July 5, 2013.

- ^ William Gray; Phil Klotzbach (August 2, 2013). Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and Landfall Strike Probability for 2013 (PDF) (Report). Colorado State University. Retrieved August 2, 2013.

- ^ NOAA: Atlantic hurricane season on track to be above-normal (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. August 8, 2013. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- Philip J. Klotzbach; William M. Gray (December 10, 2008). Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and U.S. Landfall Strike Probability for 2009 (Report). Colorado State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 12, 2009. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ John L. Beven II (August 22, 2013). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Andrea (PDF). National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- Eric S. Blake (June 15, 2013). Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 19, 2013.

- Richard J. Pasch (June 16, 2013). Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 19, 2013.

- Richard J. Pasch (June 17, 2013). Tropical Depression Two Public Advisory Number 1. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- Lixion A. Avila (June 17, 2013). Tropical Depression Two Discussion Number 5. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- Lixion A. Avila (June 19, 2013). Tropical Storm Barry Tropical Cyclone Update. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 19, 2013.

- Lixion A. Avila (June 20, 2013). Tropical Storm Barry Discussion Number 13. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- Template:Es icon "Mantienen alerta de precaución por lluvias de depresión tropical en Honduras". EFE. Tegucigalpa, Honduras: La Prensa. June 18, 2013. Retrieved June 19, 2013.

- "Hope Creek Gets Flooded Again, This Time Residents Ready". 7NewsBelize. June 18, 2013. Retrieved June 19, 2013.

- Template:Es icon "Depresión tropical tira árboles y postes en Yucatán". El Universal. Mérida, Yucatán: Vanguardia. June 18, 2013. Retrieved June 19, 2013.

- Template:Es icon "Depresión tropical en Yucatán: Inundaciones, accidentes y caìda de árboles y postes. En Progreso impacta rayo a la CFE". Merida, Yucatán: Artículo 7. June 19, 2013. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- Template:Es icon "Lluvias arrastran a seis niños en El Salvador". San Salvador, El Salvador: Sipse Noticias. June 19, 2013. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- Lixion A. Avila (July 5, 2013). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- Christopher W. Landsea (July 6, 2013). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- Stacy R. Stewart (July 6, 2013). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- Todd B. Kimberlain; Daniel P. Brown (July 8, 2013). Tropical Storm Chantal Discussion Number 1. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- Daniel P. Brown (July 8, 2013). Tropical Storm Chantal Discussion Number 5. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- Lixion A. Avila (July 9, 2013). Tropical Storm Chantal Discussion Number 7. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- Ken Kaye (July 11, 2013). "Chantal set speed record before falling apart". SunSentinel. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- Todd B. Kimberlain; Daniel P. Brown (July 10, 2013). Tropical Storm Chantal Discussion Number 9. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- Lixion A. Avila (July 10, 2013). Tropical Storm Chantal Discussion Number 11. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- Lixion A. Avila (July 10, 2013). Remnants of Chantal Discussion Number 12. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- http://thoughtleadership.aonbenfield.com/Documents/20130806_if_july_global_recap.pdf

- Stacy R. Stewart (July 22, 2013). Tropical Weather Outlook (TXT). National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 24, 2013.

- Stacy R. Stewart (July 22, 2013). Tropical Weather Outlook (TXT). National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 24, 2013.

- Stacy R. Stewart (July 23, 2013). Tropical Weather Outlook (TXT). National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 24, 2013.

- Stacy R. Stewart (July 23, 2013). Tropical Weather Outlook (TXT). National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 24, 2013.

- Daniel P. Brown (July 24, 2013). Tropical Depression Four Discussion Number 1. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 24, 2013.

- Stacy R. Stewart (July 24, 2013). Tropical Storm Dorian Discussion Number 2. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 24, 2013.

- Eric S. Blake; Richard J. Pasch (July 27, 2013). Tropical Storm Dorian Discussion Number 14. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 30, 2013.

- Stacy R. Stewart (August 3, 2013). Tropical Depression Dorian Discussion Number 16. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 3, 2013.

- Lixion A. Avila (August 3, 2013). Tropical Depression Dorian Discussion Number 18 (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 3, 2013.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|text=ignored (help) - ^ John Cangialosi (September 23, 2013). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Erin (PDF). National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- Robbie J. Berg (August 23, 2013). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 23, 2013.

- John L. Beven II (August 24, 2013). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 24, 2013.

- Robbie J. Berg (August 25, 2013). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- Richard J. Pasch (August 25, 2013). Tropical Depression Six Discussion Number 1 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- Stacy R. Stewart (August 25, 2013). Tropical Storm Fernand Special Discussion Number 2 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- Stacy R. Stewart (August 26, 2013). Tropical Storm Fernand Discussion Number 3 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- Richard Pasch (August 26, 2013). Tropical Storm Fernand Tropical Cyclone Update (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- Richard Pasch (August 26, 2013). Tropical Storm Fernand Discussion Number 4 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- Daniel Brown (August 26, 2013). Remnants of Fernand Discussion Number 6 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- Richard J. Pasch. Tropical Depression Six Advisory Number 1 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- Stacy R. Stewart and Todd B. Kimberlain (August 26, 2013). Tropical Storm Fernand Advisory Number 3 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- Daniel P. Brown (August 26, 2013). Tropical Storm Fernand Advisory Number 5 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ Template:Es icon "Fernand deja daños en 19 municipios de Veracruz". El Universal. August 26, 2013. Retrieved October 12, 2013.

- "Floods, landslides triggered by tropical depression Fernand kill 13 across Mexico". NBC News. August 26, 2013. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- "Tropical Storm Fernand targets Mexico coast". Fox News. Associated Press. August 26, 2013. Retrieved October 12, 2013.

- Template:Es icon "La tormenta tropical 'Fernand' causa al menos 14 muertos en Veracruz". CNN. August 27, 2013. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- Richard J. Pasch (August 25, 2013). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- Lixion A. Avila (August 29, 2013). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- Jack L. Beven II (August 30, 2013). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 30, 2013.

- Stacy R. Stewart (September 1, 2013). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 1, 2013.

- Eric S. Blake (September 4, 2013). Tropical Depression Seven Discussion Number 1. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 4, 2013.

- Michael J. Brennan (September 4, 2013). Tropical Storm Gabrielle Discussion Number 2. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- John L. Beven II (September 5, 2013). Tropical Depression Gabrielle Discussion Number 4. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- Michael J. Brennan (September 5, 2013). Remnants of Gabrielle Discussion Number 6. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ^ Lixion A. Avila (October 25, 2013). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Gabrielle (PDF). National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- Christopher W. Landsea; Daniel P. Brown (September 6, 2013). "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- Christopher W. Landsea; Daniel P. Brown (September 9, 2013). "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- Stacy R. Stewart (September 10, 2013). Tropical Storm Gabrielle Discussion Number 7. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- Michael J. Brennan (September 10, 2013). Tropical Storm Gabrielle Discussion Number 10. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- John L. Beven II (September 11, 2013). Tropical Storm Gabrielle Discussion Number 12. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- Daniel P. Brown (September 12, 2013). Tropical Depression Gabrielle Discussion Number 15. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- Lixion A. Avila (September 12, 2013). Tropical Storm Gabrielle Discussion Number 12. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- John P. Cangialosi (September 13, 2013). Tropical Depression Gabrielle Discussion Number 20. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- James L. Franklin; David Zelinsky (September 13, 2013). Remnants of Gabrielle Discussion Number 22. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- Stacy R. Stewart. "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- John Sullivan (September 3, 2013). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- Eric S. Blake (September 5, 2013). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- John L. Beven II (September 6, 2013). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- John L. Beven II (September 6, 2013). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- John L. Beven II (September 6, 2013). Tropical Depression Eight Discussion Number 1. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- John L. Beven II (September 6, 2013). Tropical Depression Eight Discussion Number 2. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- Lixion A. Avila (September 7, 2013). Post-Tropical Cyclone Eight Discussion Number 4. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- Template:Es icon Isabel Zamudio (September 6, 2013). "Inundaciones en Veracruz, saldo de depresión tropical 8". Milenio. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- Template:Es icon "DF: hasta con lanchas atienden inundaciones". Milenio. September 8, 2013. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- Eric S. Blake (September 13, 2013). Hurricane Humberto Discussion Number 11. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- Eric S. Blake (September 14, 2013). Tropical Storm Humberto Discussion Number 24. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- Kimberlain (September 16, 2013). Tropical Storm Humberto Discussion Number 25. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 16, 2013.

- "Humberto dissipates, last advisory issued". Retrieved September 19, 2013.

- Template:Pt icon Lusa (September 11, 2013). "Meteorologia Tempestade tropical afasta-se de Cabo Verde". Noticias ao Minuto. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- Stacy R. Stewart; John P. Cangialosi (September 10, 2013). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 18, 2013.

- Lixion A. Avila (September 10, 2013). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 18, 2013.

- Lixion A. Avila; Michael J. Brennan (September 12, 2013). Tropical Depression Ten Discussion Number 1. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 18, 2013.

- Lixion A. Avila (September 13, 2013). Tropical Storm Ingrid Discussion Number 4. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 18, 2013.

- John L. Beven II (September 14, 2013). Tropical Storm Ingrid Discussion Number 8. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 18, 2013.

- Lixion A. Avila (September 14, 2013). Hurricane Ingrid Discussion Number 10. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 18, 2013.

- James L. Franklin (September 15, 2013). Hurricane Ingrid Discussion Number 12. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 18, 2013.

- Daniel P. Brown (September 16, 2013). Tropical Storm Ingrid Discussion Number 17. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 18, 2013.

- Daniel P. Brown (September 16, 2013). Tropical Depression Ingrid Discussion Number 18. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 18, 2013.

- Robbie J. Berg (September 17, 2013). Remnants of Ingrid Discussion Number 20. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 18, 2013.

- John L. Beven II (September 26, 2013). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 28, 2013.

- Robbie J. Berg (September 26, 2013). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 28, 2013.

- Robbie J. Berg (September 27, 2013). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 28, 2013.

- John Cangialosi (September 28, 2013). Tropical Depression Eleven Discussion Number 1 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 28, 2013.

- Richard Pasch (September 30, 2013). Tropical Storm Jerry Discussion Number 7 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- John Cangialosi (October 1, 2013). Tropical Storm Jerry Discussion Number 9 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- Richard Pasch (October 1, 2013). Tropical Storm Jerry Discussion Number 11 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- Richard Pasch (October 1, 2013). Tropical Storm Jerry Discussion Number 12 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- Michael Brennan (October 2, 2013). Tropical Storm Jerry Discussion Number 16 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- Chris Landsea (October 3, 2013). Tropical Depression Jerry Discussion Number 17 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- Richard Pasch (October 3, 2013). Post-Tropical Cyclone Jerry Discussion Number 20 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- John L. Beven II (September 28, 2013). Tropical Weather Outlook (TXT) (Report). National Hurricane Center.

- John P. Cangialosi (September 28, 2013). Tropical Weather Outlook (TXT) (Report). National Hurricane Center.

- Richard J. Pasch (September 30, 2013). Tropical Weather Outlook (TXT) (Report). National Hurricane Center.

- Stacy R. Stewart (October 1, 2013). Tropical Weather Outlook (TXT) (Report). National Hurricane Center.

- Richard J.Pasch (October 2, 2013). Tropical Weather Outlook (TXT) (Report). National Hurricane Center.

- Michael J. Brennan (October 3, 2013). Tropical Storm Karen Special Discussion Number 1 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- Michael J. Brennan (October 3, 2013). Tropical Storm Karen Discussion Number 2 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- Michael J. Brennan (October 3, 2013). Tropical Storm Karen Discussion Number 3 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- Michael J. Brennan (October 4, 2013). Tropical Storm Karen Discussion Number 6 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- Stacy Stewart (October 6, 2013). Tropical Depression Karen Discussion Number 12 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- Michael Brennan (October 6, 2013). Remnants of Karen Discussion Number 14 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- "Latest track shows weaker Karen making hard right turn". WESH TV. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

- "Evacuations ordered as Tropical Storm Karen nears U.S. coast". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- "Karen threatens US during quiet hurricane season". Yahoo News. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- "Gulf Coast Storm Pulls Federal Workers Off Furlough". NY Times. Retrieved 5 October 2013.

- Daniel P. Brown (October 24, 2013). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

- Lixion A. Avila (October 24, 2013). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

- Todd B. Kimberlain (October 21, 2013). Tropical Depression Thirteen Discussion Number 1. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- Todd B. Kimberlain (October 21, 2013). Tropical Storm Lorenzo Discussion Number 2. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- Todd B. Kimberlain (October 22, 2013). Tropical Storm Lorenzo Discussion Number 5. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- Robbie J. Berg (October 23, 2013). Tropical Depression Lorenzo Discussion Number 11. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- Daniel P. Brown (October 24, 2013). Post-Tropical Cyclone Lorenzo Discussion Number 13. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- Michael J. Brennan (October 25, 2013). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- "UK windstorm heads to northern Europe". Insurance Times. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- Tropical Cyclone Names. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. April 11, 2013. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- "Dean, Felix, and Noel Retired From List of Storm Names". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 13, 2008. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- http://thoughtleadership.aonbenfield.com/Documents/20130806_if_july_global_recap.pdf

- http://thoughtleadership.aonbenfield.com/Documents/20130904_if_august_global_recap.pdf

- http://thoughtleadership.aonbenfield.com/Documents/20131007_if_september_global_recap.pdf

Notes

- The totals represent the sum of the squares for every tropical storm's intensity of over 33 knots (38 mph, 61 km/h), divided by 10,000. Calculations are provided at Talk:2013 Atlantic hurricane season/ACE calcs.

External links

- National Hurricane Center Website

- National Hurricane Center's Atlantic Tropical Weather Outlook

- Tropical Cyclone Formation Probability Guidance Product

| Tropical cyclones of the 2013 Atlantic hurricane season | ||

|---|---|---|

| TSAndrea TSBarry TSChantal TSDorian TSErin TSFernand TSGabrielle TDEight 1Humberto 1Ingrid TSJerry TSKaren TSLorenzo TSMelissa SSUnnamed | |

| 2010–2019 Atlantic hurricane seasons | |

|---|---|