| Revision as of 22:23, 23 September 2014 view sourceMinato ku (talk | contribs)473 edits Undid revision 626811416 by NeilN (talk) Landmarks, residential and offices buildings are more representative of the reality of Paris than just monuments !← Previous edit | Revision as of 22:38, 23 September 2014 view source ThePromenader (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Page movers, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers14,811 edits Undid revision 626823646 by Minato ku (talk) - There is a discussion going on about this on the talk page. Thank you.Next edit → | ||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

| {{Infobox French commune | {{Infobox French commune | ||

| |name = Paris | |name = Paris | ||

| |image = ] | |image = ] | ||

| |caption = From top left: ], ], looking towards ], skyline of Paris on the ] river with the ] bridge, and the ] | |||

| |caption = Paris, with the ] in the foreground and the skyscrapers of ] in the background. | |||

| |image flag = Flag of Paris.svg | |image flag = Flag of Paris.svg | ||

| |image flag size = 100px | |image flag size = 100px | ||

Revision as of 22:38, 23 September 2014

This article is about the capital of France. For other uses, see Paris (disambiguation).Place in Île-de-France, France

| Paris | |

|---|---|

From top left: Louvre Pyramid, Arc de Triomphe, looking towards La Défense, skyline of Paris on the Seine river with the Pont des Arts bridge, and the Eiffel Tower From top left: Louvre Pyramid, Arc de Triomphe, looking towards La Défense, skyline of Paris on the Seine river with the Pont des Arts bridge, and the Eiffel Tower | |

Flag Flag Coat of arms Coat of arms | |

| Motto(s): "Fluctuat nec mergitur" (Latin: "She is tossed by the waves but does not sink") | |

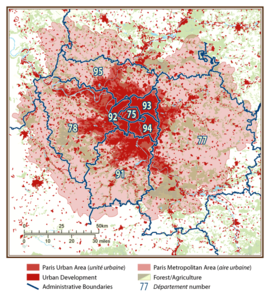

| Location of Paris | |

| Country | France |

| Region | Île-de-France |

| Department | Paris |

| Subdivisions | 20 arrondissements |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (since 5 April 2014) | Anne Hidalgo (PS) |

| Area | 105.4 km (40.7 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 2,844.8 km (1,098.4 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 17,174.4 km (6,631.1 sq mi) |

| Population | 2,249,975 |

| • Rank | 1st in France |

| • Urban | 10,516,110 |

| • Metro | 12,292,895 |

| Demonym | Parisian |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| INSEE/Postal code | 75056 /75001-75020, 75116 |

| Website | www.paris.fr |

| French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. | |

Paris (UK: /ˈpærɪs/; US: /ˈpɛərɪs/ ; French: Template:IPA-fr) is the capital and most populous city of France. Situated on the Seine River, in the north of the country, it is at the heart of the Île-de-France region, also known as the région parisienne ("Paris Region" in English). Within its administrative limits largely unchanged since 1860 (the 20 arrondissements), the city of Paris has a population of 2,249,975 inhabitants (January 2011), but its metropolitan area is one of the largest population centres in Europe, with 12,292,895 inhabitants at the January 2011 census.

Archeological evidence shows that the site of Paris has been occupied by man since between 9800 and 7500 BC. In the 3rd century BC, it became the site of a town of a Celtic people called the Parisii, for whom the modern city is named. In the 1st century BC, it was conquered by the Romans and became a Gallo-Roman garrison town called Lutetia. It was Christianised in the 3rd century and became the capital of Clovis the Frank in the 5th century. In 987, under King Hugh Capet, it became the capital of France.

In the 12th century, Paris was the largest city in the western world, a prosperous trading center, the home of the University of Paris, one of the most influential centers of learning in Europe; and the birthplace of the style that later became known as Gothic architecture. In the eighteenth century, it was the center stage for many important events in French history, including the Enlightenment and the French Revolution, and an important center of commerce, fashion, science, and the arts, a position it still holds today.

Paris has one of the largest GDPs in the world, €607 billion (US$845 billion) in 2011, and is one of the world's leading tourist destinations. In 2013-2014, it received an estimated 15.57 million international overnight visitors, making it the third most popular destination for international travelers, after London and Bangkok. The Paris Region hosts the world headquarters of 30 of the Fortune Global 500 companies in several business districts, notably La Défense, the largest dedicated business district in Europe.

Paris is the home of the Louvre, the most visited art museum in the world, with outstanding collections of European and ancient art; the Musée d'Orsay, devoted to 19th century French art, including the works of the French impressionists; the Centre Georges Pompidou, a museum of international modern art, and the Musée du quai Branly, a new museum devoted to the arts and cultures of the Americas, Africa, Asia and Oceania; and many other notable art museums and galleries. It also is the home of several masterpieces of Gothic architecture, most notably the Cathedral of Notre-Dame-de-Paris (12th century) and Sainte-Chapelle (13th century). Other notable and much-visited landmarks include the Eiffel Tower, built in 1889 to celebrate the centennial of the French Revolution; the Sacré-Cœur Basilica on Montmartre, a Neo-Byzantine style church built between 1875 and 1919; and Les Invalides, a 17th-century hospital and chapel built for disabled soldiers, where the tomb of Napoleon is located.

Paris is a global hub of fashion, noted for its haute couture tailoring, its high-end boutiques, and the twice-yearly Paris Fashion Week. It is world renowned for its haute cuisine, attracting many of the world's leading chefs. Many of France's most prestigious universities and Grandes Écoles are in Paris or its suburbs, and France's major newspapers Le Monde, Le Figaro, Libération are based in the city, and Le Parisien in Saint-Ouen near Paris.

Paris is home to the association football club Paris Saint-Germain FC and the rugby union club Stade Français. The 80,000-seat Stade de France, built for the 1998 FIFA World Cup, is located in Saint-Denis. Paris hosts the annual French Open Grand Slam tennis tournament on the red clay of Roland Garros. Paris played host to the 1900 and 1924 Summer Olympics, the 1938 and 1998 FIFA World Cup, and the 2007 Rugby World Cup. The city is a major rail, highway, and air-transport hub, served by the two international airports Paris-Charles de Gaulle and Paris-Orly. Opened in 1900, the city's subway system, the Paris Métro, serves 5.23 million passengers daily. Paris is the hub of the national road network, and is surrounded by three orbital roads: the Boulevard Périphérique, the A86 motorway, and the Francilienne motorway in the outer suburbs.

Toponyms

- See Wiktionary for the name of Paris in various languages other than English and French.

The name "Paris" is derived from its early inhabitants, the Celtic tribe known as the Parisii. The city was called Lutetia (more fully, Lutetia Parisiorum, "Lutetia of the Parisii"), during the Roman era of the 1st to the 4th century AD, but during the reign of Julian the Apostate (360–3), the city was renamed Paris. It is believed that the name of the Parisii tribe comes from the Celtic Gallic word parisio, meaning "the working people" or "the craftsmen".

Paris is often referred to as "La Ville-Lumière" ("The City of Light"). The name is sometimes said to come from its reputation as a centre of education and ideas during the Age of Enlightenment. The name took on a more literal sense when Paris became one of the first European cities to adopt gas street lighting: the Passage des Panoramas was Paris' first gas-lit indoor passageway from 1817. The first gas street light was installed in 1822; Place Vendôme was lit in 1825, and rue de la Paix in 1829. During the reign of King Louis-Philippe, the Champs-Elysées became known as the Avenue Lumière and Paris as the Ville Lumière. Beginning in the 1860s, Napoleon III had the boulevards and streets of Paris illuminated by fifty-six thousand gas lamps, and the Arc de Triomphe, the Hôtel de Ville and Champs-Élysées were decorated with garlands of lights.

Since the mid-19th century, Paris is also known as Paname ("panam") in the Parisian slang called argot (![]() Moi j'suis d'Paname, i.e. "I'm from Paname"). The singer Renaud repopularised the term among the younger generation with his 1976 album Amoureux de Paname ("In love with Paname").

Moi j'suis d'Paname, i.e. "I'm from Paname"). The singer Renaud repopularised the term among the younger generation with his 1976 album Amoureux de Paname ("In love with Paname").

Inhabitants are known in English as "Parisians" and in French as Parisiens (Template:IPA-fr) and Parisiennes. Parisians are also pejoratively called Parigots (Template:IPA-fr) and Parigotes, a term first used in 1900 by those living outside the Paris region.

History

Main articles: History of Paris and Timeline of ParisOrigins

The oldest known site of human habitation in Paris, a settlement of hunter-gatherers dating to between 9000 and 7500 BC, was found in 2006 near the Seine on rue Henri-Farman in the 15th arrondissement. The Parisii, a sub-tribe of the Celtic Senones, inhabited the area near the river Seine from around 250 BC, building a trading settlement on the island, later the Île de la Cité, the easiest place to cross. They minted their own coins and traded by river with towns on the Rhine and the Danube, and also with Spain.

The Romans conquered the Paris basin in 52 BC, building a new town on the left bank around the present site of the Pantheon, and on the Île de la Cité. The Gallo-Roman town was originally called Lutetia, or Lutetia Parisorum but later Gallicised to Lutèce. It became a prosperous city with a forum, baths, temples, theatres, and an amphitheatre.

In 305 AD, the city began to be called Civitas Parisiorum, ("The City of the Parisii"), and that name was inscribed on the milestones. By the end of the Roman Empire, it was known simply as Parisius in Latin and Paris in French. Christianity was introduced into Paris in the middle of the 3rd century AD. According to tradition, it was brought by Saint Denis, the Bishop of the Parisii. When he refused to renounce his faith, he was beheaded on Mount Mercury. The hill where he was executed later became the "Mountain of Martyrs" (Mons Martyrum), eventually "Montmartre".

The collapse of the Roman empire, along with the Germanic invasions of the 5th-century, sent the city into a period of decline. The Paris region was under full control of the Salian Franks by the late 5th century. The Frankish king Clovis the Frank, the first king of the Merovingian dynasty, made the city his capital from 508, but in the late 8th century the Carolingian dynasty moved the capital of the Franks to Aachen, and the counts of Paris controlled little more than immediate area around the city. In the early 9th century, Paris suffered a series of devastating raids by the Vikings. In 987 AD Hugh Capet, count of Paris, was elected king of France. Under the rule of the Capetian kings, Paris became the capital once more, and gradually became the largest and most prosperous city in France.

Middle Ages and the Renaissance

By the end of the 12th century, Paris had become the political, economic, religious and cultural capital of France. The Île de la Cité was the site of the new royal palace, and king Philippe-Auguste had begun building the new cathedral of Notre-Dame 1163. The Left Bank (south of the Seine) was the site of the University of Paris, a guild of students and teachers formed in the mid-12th century to train scholars in theology. The Right Bank (north of the Seine) became the centre of commerce and finance. A league of merchants, the Hanse parisienne, was established and quickly became a powerful force in the city's affairs. Between 1190 and 1202, Philippe-Auguste built the massive château du Louvre (a fortress) on the right bank, where the museum is today. He paved the first streets with stone, replaced the two wooden bridges over the Seine with stone bridges, and began the first wall around the city.

Between 1241 and 1248, Louis IX, (1226–1270), known to history as "Saint Louis", built next to his palace (the Palais de la Cité) the Sainte Chapelle, the masterpiece of Rayonnant Gothic art, to house relics from the crucifixion of Christ. At the same period that the Saint-Chapelle was built, the great eighteen meter high stained glass rose windows were added to the transept of Notre Dame Cathedral.

The Black Plague struck Paris for the first time in 1348, killing as many as 800 people a day, and the English and Burgundians occupied Paris in 1356 during the Hundred Years' War, not leaving Paris until 1436.

In 1534, François I transformed the Louvre from a fortress into a palace, and became the first king to reside there. Between 1564 and 1572, Catherine de Medici built a new royal residence, the Tuileries Palace, and the Jardin des Tuileries.

During the French Wars of Religion, Paris was a stronghold of the Catholic league. On 24 August 1572, the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre began in Paris, when thousands of French Protestants were killed. The war did not end until 1594, when Henri IV converted to Catholicism and the city welcomed him as king.

Henry IV completed the Pont Neuf the first Paris bridge not lined with buildings, constructed a new wing of the Louvre, the grande galerie or galerie au bord de l'eau, connecting it with the Tuileries Palace on the south side, along the Seine, and built the first Paris residential square, the Place des Vosges.

17th century

After the assassination of Henry IV in 1610, his widow, Marie de Medicis, built her own residence, the Luxembourg Palace (1615-1634), on the left bank.

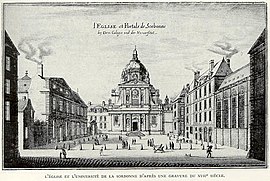

Cardinal de Richelieu, chief minister of Louis XIII, was determined to make Paris the most beautiful city in Europe. He built five new bridges, a new chapel for the College of Sorbonne, and a palace for himself, the Palais Cardinal, which he bequeathed to the young Louis XIV and became, after his death in 1642, the Palais-Royal.

Louis XIV distrusted the Parisians; as a child he had been forced to flee the city during an uprising known as the Fronde and, in 1682, he moved his court permanently to Versailles; but he also wanted to add to the architecture of Paris. He built the Collège des Quatre-Nations, Place Vendôme, Place des Victoires, and began Les Invalides. More important, he wanted to show that Paris was safe from any invasion, and had the city walls demolished. The place of the walls was later taken by the Grands Boulevards.

The 18th century and the French Revolution

Main article: French Revolution

Between 1640 and 1789, Paris grew in population from 400,000 to 600,000. Under Louis XV, the city expanded westward. A large new square, Place Louis XV, the future Place de la Concorde, was created between 1766 and 1775, and new boulevard, the Champs-Élysées, was built as far as the Étoile. The Faubourg Saint-Germain on the left bank became the most fashionable aristocratic neighborhood. The working-class Faubourg Saint-Antoine on the eastern site of the city grew more and more crowded.

Paris became the center of an explosion of philosophic and scientific activity known as the Age of Enlightenment. Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert published their Encyclopédie in 1751-52. By the 1720s, there were around 400 cafés in the city, and they became the centers for the exchanging of ideas and information.

In the summer of 1789, Paris became the center stage of the French Revolution. On 11 July 1789, soldiers attacked a peaceful demonstration on Place Louis XV, where a large crowd of Parisians were protesting the dismissal by the King of his reformist finance minister, Jacques Necker. The reform movement turned quickly into a revolution. On 13 July, a crowd of Parisians occupied the Hôtel de Ville. On 14 July, a mob seized the arsenal at the Invalides, acquiring thousands of guns, and stormed the Bastille, a symbol of royal authority, a prison which at the time held only seven prisoners, four counterfeiters, one libertine aristocrat imprisoned at the demand of his family, and two lunatics. The first independent Paris Commune, or city council, met in the Hôtel de Ville and on 15 July, and a new Mayor, the astronomer Jean Sylvain Bailly.

.

On 6 October 1789, Louis XVI and his family were brought to Paris and made virtual prisoners within the Tuileries Palace. On 21 June 1791, the royal family fled Paris, was arrested in Varennes and brought back to Paris on the 25th. On 10 August 1792, mobs of the most militant revolutionaries, the sans-culottes attacked the Tuileries Palace. On 13 August, Louis XVI and his family were imprisoned in the Temple fortress. Between 2 and 7 September, massacres took place in the prisons, which was the beginning of the Reign of Terror (la Terreur) imposed upon France by the new government. On 21 January 1793, Louis XVI was guillotined on the Place de la Révolution, the former Place Louis XV. Marie Antoinette was executed on the same square on 16 October 1793. Bailly, the first Mayor of Paris, was sent to the guillotine. During the reign of terror, 16,594 persons were tried by the revolutionary tribunal and executed. The property of the aristocracy and the church was nationalised, and the churches closed, sold or demolished.

A succession of revolutionary factions ruled Paris: on 1 June 1793, the Montagnards seized power from the Girondins, then were replaced by Georges Danton and his followers; in 1794, they were overthrown and guillotined by a new government led by Maximillien Robespierre. On 27 July 1794, Robespierre himself was executed by a coalition of Montagnards and moderates. This signaled the end of the Terreur. The executions ceased and the prisons gradually emptied. The new government, the Directory (November 1795-November 1799), made its headquarters at the Luxembourg Palace. It was replaced in turn, on 9 November 1799 by the Consulate with Napoleon Bonaparte as First Consul.

During the Revolution, under the direction of Alexandre Lenoir, who had been mandated by the National Constituent Assembly in 1791, a group of scholars and historians collected statues and paintings from the demolished churches, and stored them at the Couvent des Petits-Augustins. After the Revolution, the objects went back to their previous owners or, in case those could not be found, to the Louvre.

19th century

Further information: Paris during the Second EmpireBetween 1789 and 1799, the population of Paris dropped by one hundred thousand. Between 1799 and 1815, it gained 160,000 new residents, reaching a population of 660,000. Napoleon Bonaparte placed the city government under the Prefect of the Seine, named by him. He turned the Louvre into the Musée Napoléon, displaying paintings from the countries he conquered. He began building the Rue de Rivoli, erected a column made of the bronze of captured cannon in the Place Vendôme, built the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel, a triumphal arch, on the Place du Carrousel, began a much larger one at Place de l'Étoile, and built a Temple to the Glory of his Great Army, which was consecrated as La Madeleine church during Louis-Philippe's reign, in 1842. He created Père Lachaise Cemetery and began building the Canal de l'Ourcq to bring fresh water to the city's fountains. He also built the city's first iron bridge, the Pont des Arts.

After the fall of Napoleon, Paris was occupied by thirty thousand Russian and Allied soldiers, who camped in the Bois de Boulogne and along the Champs-Élysées. The Restoration period ended with the July Revolution of 1830, which brought a constitutional monarch, Louis Philippe I, to power. Louis Philippe erected the Luxor Obelisk on Place de la Concorde (1836) and the July Column in the Place de la Bastille (1840), finished the Arc de Triomphe (1836) and placed Napoleon's ashes in his tomb at Les Invalides (1840). Victor Hugo published The Hunchback of Notre-Dame in 1831, causing a revival of interest in Paris history, and the restoration of the Notre Dame cathedral. The first railroad line from Paris to Saint-Germain-en-Laye opened in 1837, beginning a period of massive migration from the countryside to the city.

Louis-Philippe was overthrown by a popular uprising in 1848. Napoleon III became the first elected president of France in 1848, then declared himself Emperor in 1853. His prefect of the Seine, Georges-Eugène Haussmann, employed thousands of workers to build two hundred kilometers of wide new boulevards and streets, new acquducts and sewers, and 1,835 hectares of new public parks, including the Bois de Boulogne, Bois de Vincennes, Parc des Buttes-Chaumont, Parc Montsouris and many smaller parks and squares. Haussmann imposed strict building standards on the new boulevards, setting the height, façade style, building material and color, which gave central Paris its distinctive look. In 1860, Napoleon III annexed the surrounding towns to the city of Paris and created eight new arrondissements, expanding Paris to its current limits.

Napoleon III was captured and overthrown during Franco-Prussian War (1870–71), and Paris was besieged by the Prussian Army. After months of blockade, hunger, and then bombardment by the Prussians, the city was forced to surrender on 28 January 1871.

On 28 March 1871, a revolutionary government called the Paris Commune seized power in Paris. The Commune held power for two months, until it was suppressed by the French army at the end of May 1871. Seven to ten thousand Communards were killed in the fighting or shot afterwards by summary firing squads during the Bloody Week (21 to 28 May 1871), eight thousand more were imprisoned, deported to New Caledonia, or fled abroad. Several Paris landmarks, including the Tuileries Palace and Hôtel de Ville, were burned by the Communards in the last days of fighting.

Late in the 19th century, Paris hosted two major international expositions: the 1889 Universal Exposition, was held to mark the centennial of the French Revolution, and featured the Eiffel Tower; and the 1900 Universal Exposition, which gave Paris the Pont Alexandre III, the Grand Palais, the Petit Palais and the first Paris Métro line.

20th century

By 1901, the population of Paris had grown to 2,715,000. The city became the birthplace of modern art; Pablo Picasso, living in Montmartre, painted his famous La famille de saltimbanques and Les Demoiselles d'Avignon between 1904 and 1909.

In September 1914, at the beginning of the First World War, Paris found itself on the front line; it was spared by the French and British victory at the First Battle of the Marne, achieved with the assistance of some 600 to 1000 Paris taxis which carried six thousand soldiers to the front. (The taxis dutifully ran their meters, as required by law, and were reimbursed 70,002 francs by the French treasury). In the years after the war, known as Les Années Folles, Paris attracted artists, writers and musicians from around the world, including Ernest Hemingway, Igor Stravinsky and Josephine Baker. Paris gave birth to the art movements known as dadaism and surrealism.

On 14 June 1940, the German army entered Paris without resistance. On 16–17 July 1942, following German orders, the French police and gendarmes arrested 12,884 Jews, in the great majority Jews who had fled eastern and central Europe and found refuge in France before World War II, among which 4115 were children, and confined them during five days at the Vel d'Hiv (Vélodrome d'Hiver), from which they were taken by bus to French internment and transit camps at Drancy, Beaune-la-Rolande and Pithiviers, before being transported by train to the extermination camp at Auschwitz. None of the children came back. Shortly after a resistance and police uprising, the city was liberated on 25 August 1944 by the French 2nd Armored Division and the US 4th Infantry Division.

The population of Paris dropped from 2,850,000 in 1954 to 2,152,000 in 1990, as middle-class families departed for the suburbs. A suburban railroad network, called the RER, was built to complement the Métro, and the Périphérique expressway encircling the city, was completed in 1973.

In May 1968, protesting students occupied the Sorbonne and put up barricades in the Latin Quarter. Thousands of Paris workers joined the students, and the student movement grew into a two-week general strike. Supporters of the government won the June elections by a large majority, but the May 1968 events in France resulted in the breakup of the University of Paris into thirteen independent campuses.

The tallest building in the city, the Tour Montparnasse, 57 stories and 210 meters high, was built between 1969 and 1973. Frequently criticized by Parisians, it remains the city's only skyscraper.

Each President of the postwar Fifth French Republic added his own monuments to Paris. President Georges Pompidou started the Centre Georges Pompidou (1977), a museum of 20th century art; Valéry Giscard d'Estaing began the Musée d'Orsay (1986), devoted to 19th century French art. President François Mitterrand, in power for fourteen years, built the Opéra Bastille (1985-1989), the Bibliothèque nationale de France (1996), the Arche de la Défense (1985-1989), and the Louvre Pyramid and underground courtyard (1983-1989).

21st century

In the early 21st century, the population of Paris began to increase slowly again, as more young people moved into the city. It reached 2.25 million in 2011.

The Musée du quai Branly opened in 2006, designed to showcase the indigenous art of Africa, Oceania, Asia and the Americas.

In 2007, President Nicolas Sarkozy launched the Grand Paris project, to integrate Paris more closely with the surrounding regions. It called for the construction of a €26.5 billion new automatic metro, connecting the Grand Paris regions to one another and to the centre of Paris.

In March 2001, Bertrand Delanoë became the first Socialist mayor of Paris, and also the first openly gay mayor of the city. In 2007, in an effort to reduce car traffic in the city, he introduced the Vélib', a system which rents bicycles for the use of local residents and visitors. The new Mayor also transformed a section of the highway along the left bank of the Seine into an urban promenade and park, the Promenade des Berges de la Seine.

On April 5, 2014, Anne Hidalgo, a socialist, was elected the first woman mayor of Paris.

Geography

Main article: Topography of Paris

Paris is located in northern central France. By road it is 450 kilometres (280 mi) south-east of London, 287 kilometres (178 mi) south of Calais, 305 kilometres (190 mi) south-west of Brussels, 774 kilometres (481 mi) north of Marseille, 385 kilometres (239 mi) north-east of Nantes, and 135 kilometres (84 mi) south-east of Rouen. Paris is located in the north-bending arc of the river Seine, spread widely on both banks of the river, and includes two inhabited islands, the Île Saint-Louis and the larger Île de la Cité, which forms the oldest part of the city. The river’s mouth on the English Channel (Manche) is about 233 mi (375 km) downstream of the city. Overall, the city is relatively flat, and the lowest point is 35 m (115 ft) above sea level. Paris has several prominent hills, of which the highest is Montmartre at 130 m (427 ft) . Montmartre gained its name from the martyrdom of Saint Denis, first bishop of Paris atop the "Mons Martyrum" (Martyr's mound) in 250.

Excluding the outlying parks of Bois de Boulogne and Bois de Vincennes, Paris occupies an oval measuring about 87 km (34 sq mi) in area, enclosed by the 35 km (22 mi) ring road, the Boulevard Périphérique. The city's last major annexation of outlying territories in 1860 not only gave it its modern form but also created the twenty clockwise-spiralling arrondissements (municipal boroughs). From the 1860 area of 78 km (30 sq mi), the city limits were expanded marginally to 86.9 km (33.6 sq mi) in the 1920s. In 1929, the Bois de Boulogne and Bois de Vincennes forest parks were officially annexed to the city, bringing its area to about 105 km (41 sq mi). The metropolitan area of the city is 2,300 km (890 sq mi).

Climate

Paris has a typical Western European oceanic climate (Köppen climate classification: Cfb ) which is affected by the North Atlantic Current. The overall climate throughout the year is mild and moderately wet. Summer days are usually moderately warm and pleasant with average temperatures hovering between 15 and 25 °C (59 and 77 °F), and a fair amount of sunshine. Each year, however, there are a few days where the temperature rises above 30 °C (86 °F). Some years have even witnessed long periods of harsh summer weather, such as the heat wave of 2003 where temperatures exceeded 30 °C (86 °F) for weeks, surged up to 39 °C (102 °F) on some days and seldom cooled down at night. More recently, the average temperature for July 2011 was 17.6 °C (63.7 °F), with an average minimum temperature of 12.9 °C (55.2 °F) and an average maximum temperature of 23.7 °C (74.7 °F).

Spring and autumn have, on average, mild days and fresh nights, but are changing and unstable. Surprisingly warm or cool weather occurs frequently in both seasons. In winter, sunshine is scarce; days are cold but generally above freezing with temperatures around 7 °C (45 °F). Light night frosts are however quite common, but the temperature will dip below −5 °C (23 °F) for only a few days a year. Snowfall is uncommon, but the city sometimes sees light snow or flurries with or without accumulation.

Rain falls throughout the year. Average annual precipitation is 652 mm (25.7 in) with light rainfall fairly distributed throughout the year. The highest recorded temperature is 40.4 °C (104.7 °F) on 28 July 1948, and the lowest is a −23.9 °C (−11.0 °F) on 10 December 1879.

| Climate data for Paris (1981–2010 averages) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.1 (61.0) |

21.4 (70.5) |

25.7 (78.3) |

30.2 (86.4) |

34.8 (94.6) |

37.6 (99.7) |

40.4 (104.7) |

39.5 (103.1) |

36.2 (97.2) |

28.4 (83.1) |

21.0 (69.8) |

17.1 (62.8) |

40.4 (104.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.2 (45.0) |

8.3 (46.9) |

12.2 (54.0) |

15.6 (60.1) |

19.6 (67.3) |

22.7 (72.9) |

25.2 (77.4) |

25.0 (77.0) |

21.1 (70.0) |

16.3 (61.3) |

10.8 (51.4) |

7.5 (45.5) |

16.0 (60.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.0 (41.0) |

5.6 (42.1) |

8.8 (47.8) |

11.5 (52.7) |

15.3 (59.5) |

18.3 (64.9) |

20.5 (68.9) |

20.4 (68.7) |

16.9 (62.4) |

13.0 (55.4) |

8.3 (46.9) |

5.5 (41.9) |

12.4 (54.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.7 (36.9) |

2.8 (37.0) |

5.3 (41.5) |

7.3 (45.1) |

10.9 (51.6) |

13.8 (56.8) |

15.8 (60.4) |

15.7 (60.3) |

12.7 (54.9) |

9.6 (49.3) |

5.8 (42.4) |

3.4 (38.1) |

8.9 (48.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −14.6 (5.7) |

−14.7 (5.5) |

−9.1 (15.6) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

3.1 (37.6) |

6.0 (42.8) |

6.3 (43.3) |

1.8 (35.2) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

−14.0 (6.8) |

−23.9 (−11.0) |

−23.9 (−11.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 51.0 (2.01) |

41.2 (1.62) |

47.6 (1.87) |

51.8 (2.04) |

63.2 (2.49) |

49.6 (1.95) |

62.3 (2.45) |

52.7 (2.07) |

47.6 (1.87) |

61.5 (2.42) |

51.1 (2.01) |

57.8 (2.28) |

637.4 (25.09) |

| Average precipitation days | 9.9 | 9.0 | 10.6 | 9.3 | 9.8 | 8.4 | 8.1 | 7.7 | 7.8 | 9.6 | 10.0 | 10.9 | 111.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 62.5 | 79.2 | 128.9 | 166.0 | 193.8 | 202.1 | 212.2 | 212.1 | 167.9 | 117.8 | 67.7 | 51.4 | 1,661.6 |

| Source: Météo-France | |||||||||||||

Administration

Main articles: Administration of Paris and Arrondissements of Paris

As the capital of France, Paris is the seat of France's national government. For the executive, the two chief officers each have their own official residences, which also serve as their offices. The President of France resides at the Élysée Palace (Palais de l'Élysée) in the 8th arrondissement, while the Prime Minister's seat is at the Hôtel Matignon in the 7th arrondissement. Government ministries are located in various parts of the city; many are located in the 7th arrondissement, near the Matignon.

The two houses of the French Parliament are located on the left bank. The upper house, the Senate, meets in the Palais du Luxembourg in the 6th arrondissement, while the more important lower house, the Assemblée Nationale, meets in the Palais Bourbon in the 7th arrondissement. The President of the Senate, the third-highest public official in France, resides in the Petit Luxembourg, a smaller palace annex to the Palais du Luxembourg.

France's highest courts are located in Paris. The Court of Cassation, the highest court in the judicial order, which reviews criminal and civil cases, is located in the Palais de Justice on the Île de la Cité, while the Conseil d'État, which provides legal advice to the executive and acts as the highest court in the administrative order, judging litigation against public bodies, is located in the Palais Royal in the 1st arrondissement. The Constitutional Council, an advisory body with ultimate authority on the constitutionality of laws enacted by Parliament, also meets in the Montpensier wing of the Palais Royal. Each of Paris' twenty arrondissements has its own town hall and a directly elected council (conseil d'arrondissement), which, in turn, elects an arrondissement mayor. A selection of members from each arrondissement council form the Council of Paris (conseil de Paris), which, in turn, elects the mayor of Paris.

Paris and its region host the headquarters of many international organisations including UNESCO, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the International Chamber of Commerce, the Paris Club, the European Space Agency, the International Energy Agency, the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie, the European Union Institute for Security Studies, the International Bureau of Weights and Measures, the International Exhibition Bureau and the International Federation for Human Rights. Paris is today one of the world's leading business and cultural centres and its influences in politics, education, entertainment, media, science, and the arts all contribute to its status as one of the world's major global cities. Paris has numerous partner cities, but according to the motto "Only Paris is worthy of Rome; only Rome is worthy of Paris"; the only sister city of Paris is Rome and vice-versa.

City government

Main articles: Paris mayors and Arrondissements of Paris

Paris has been a commune (municipality) since 1834 (and also briefly between 1790 and 1795). At the 1790 division (during the French Revolution) of France into communes, and again in 1834, Paris was a city only half its modern size, composed of 12 arrondissements, but, in 1860, it annexed bordering communes, totally enclosing the surrounding towns (bourgs) either fully or partly, to create the new administrative map of 20 arrondissements (municipal districts) the city still has today. Every arrondissement has its own mayor, town hall, and special characteristics.

Demographics

| 2019 Census Paris Region | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Île-de-France) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

As of the January 2011 census, the population of the city of Paris proper stood at 2,249,975, while that of the Paris Metropolitan Area (the city, its suburbs, and the surrounding commuter belt) stood at 12,292,895. Though substantially lower than at its peak in the early 1920s, the density of the city proper is one of the highest in the developed world. Compared to the rest of France, the main features of the Parisian population are a high average income, relatively young median age, high proportion of international migrants and high economic inequalities. Similar characteristics are found in other large cities throughout the world.

Population evolution

The population of the city proper reached a maximum shortly after World War I, with nearly 3 million inhabitants, and then decreased for the rest of the 20th century to the benefit of the suburbs. Most of the decline occurred in the 1960s and 1970s, when it fell from 2.8 to 2.2 million. This trend toward de-densification of the centre was also observed in other large cities like London and New York City.

Since the beginning of 21st century, the population of the city of Paris proper has started once again to rise, gaining 125,000 inhabitants between 1999 and 2011, despite persistent negative net migration and a fertility rate well below 2. The population growth is explained by the high proportion of people in the 18-40 age range who are most likely to have children. The Paris Metropolitan Area, whose population has grown uninterruptedly since the end of World War II, gained 937,000 inhabitants between 1999 and 2011. Contrary to the city of Paris proper, the fertility rate of the overall metropolitan area is above 2 children per woman.

Paris is one of the most densely populated cities in the world. Its population density, excluding the outlying woodland parks of Bois de Boulogne and Bois de Vincennes, was 25,864 inhabitants per square kilometre (66,986 /sq mi) at the 2011 census, which could be compared only with some Asian megapolises and the New York City borough of Manhattan. Even including the two woodland areas, its population density was 21,347 /km2 (55,288 /sq mi), the fifth-most-densely populated commune in France after Levallois-Perret, Le Pré-Saint-Gervais, Vincennes, Saint-Mandé, and Montrouge—all of which border the city proper. The most sparsely populated quarters are the western and central office and administration-focused arrondissements. The city's population is densest in the northern and eastern arrondissements; the 11th arrondissement had a density of 42,138 inhabitants per square kilometre (109,137 /sq mi) in 2011, and some of its eastern quarters had densities close to 100,000 /km2 (260,000 /sq mi) in the same year.

Income

The GDP per capita in the Île-de-France region was around 49,800 euros in 2010. The average net household income (after social, pension and health insurance contributions) was 36,085 euros in Paris for 2011. It ranges from €22,095 in the 19th arrondissement to €82,449 in the 7th arrondissement. The median taxable income for 2011 was around 25,000 euros in Paris and 22,200 for Île-de-France. Generally speaking, incomes are higher in the Western part of the city and in the Western suburbs than in the Northern and Eastern parts of the urban area.

Migration

In 1954, there were 135,000 foreign immigrants living in Paris, mostly from from Algeria, Morocco, Italy and Spain. Today Paris and its metropolitan area is one of the most multi-cultural in Europe: at the 2010 census, 23.0% of the total population in the Paris Region was born outside of Metropolitan France, up from 19.7% at the 1999 census.

About one third of persons who have recently moved to Metropolitan France from foreign countries settle in the Paris Region, about a third of whom in the city of Paris proper. 20% of the Paris population are first-generation international immigrants, and 40% of children have at least one immigrant parent. Recent immigrants tend to be more diverse in terms of qualification: more of them have no qualification at all and more of them have tertiary education.

Though international migration rate is positive, population flows from the rest of France are more intense, and negative. They are heavily age dependent: while many retired people leave Paris for the southern and western parts of France, migration flows are positive in the 18-30 age range. About one half of Île-de-France population was not born in the region.

Economy

Main article: Economy of Paris La Défense, the largest dedicated business district in Europe.

La Défense, the largest dedicated business district in Europe.

The Paris Region is France's premier centre of economic activity, and with a 2011 GDP of €607 billion (US$845 billion), it is not only the wealthiest area of France, but has one of the highest GDPs in the world, after Tokyo and New York, making it an engine of the global economy. Were it a country, it would rank as the seventeenth-largest economy in the world. While its population accounted for 18.8 percent of the total population of metropolitan France in 2011, its GDP accounted for 31.0 per cent of metropolitan France's GDP. Wealth is heavily concentrated in the western suburbs of Paris, notably Neuilly-sur-Seine, one of the wealthiest areas of France. This mirrors a sharp political divide, with political conservatism being much more common towards the western edge, whilst the political spectrum lies more to the left in the east.

The Parisian economy has been gradually shifting towards high-value-added service industries (finance, IT services, etc.) and high-tech manufacturing (electronics, optics, aerospace, etc.). However, in the 2009 European Green City Index, Paris was still listed as the second most "green" large city in Europe, after Berlin. The Paris region's most intense economic activity through the central Hauts-de-Seine département and suburban La Défense business district places Paris' economic centre to the west of the city, in a triangle between the Opéra Garnier, La Défense and the Val de Seine. While the Paris economy is largely dominated by services, it remains an important manufacturing powerhouse of Europe, especially in industrial sectors such as automobiles, aeronautics, and electronics. The Paris Region hosts the headquarters of 30 of the Fortune Global 500 companies.

The 1999 census indicated that, of the 5,089,170 persons employed in the Paris urban area, 16.5 per cent worked in business services; 13% in commerce (retail and wholesale trade); 12% in manufacturing; 10.0 per cent in public administrations and defence; 8.7 per cent in health services; 8% in transport and communications; 6.6 per cent in education, and the remaining 25% in many other economic sectors. In the manufacturing sector, the largest employers were the electronic and electrical industry (17.9 per cent of the total manufacturing workforce in 1999) and the publishing and printing industry (14.0 per cent of the total manufacturing workforce), with the remaining 68% of the manufacturing workforce distributed among many other industries. Tourism and tourist related services employ 6% of Paris' workforce, and 3.6 per cent of all workers within the Paris Region. Sources place unemployment in the Paris "immigrant ghettos" at 20 to 40 per cent.

Paris receives around 28 million tourists per year, of which 17 million are foreign visitors,. In 2013-2014, Paris received 15.57 million international overnight visitors, which made Paris the third most popular tourist destination city, after London and Bangkok. Paris has four UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Its museums and monuments are among its highest-esteemed attractions; tourism has motivated both the city and national governments to create new ones. The city's top tourist attraction was the Cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris, which welcomed 14 million visitors in 2013. The Louvre museum had more than 9.2 million visitors in 2013, making it the most visited museum in the world. The other top cultural attractions in Paris in 2013 were the Basilique du Sacré-Cœur (10,500,000 visitors); the Eiffel Tower (6,740,000 visitors); the Centre Pompidou (3.745.000 visitors) and Musée d'Orsay (3,467.000 visitors). Disneyland Paris, in Marne-la-Vallée, 32 km (20 miles) east of centre of Paris, is a major tourist attraction for visitors to not only Paris but also the rest of Europe, with 14.5 million visitors in 2007.

Cityscape

Panorama of Paris as seen from the Eiffel Tower as a 270-degree view. The river flows from right to left, from the north-east to the south-west.

Panorama of Paris as seen from the Eiffel Tower as a 270-degree view. The river flows from right to left, from the north-east to the south-west.

Architecture

See also: Haussmann's renovation of Paris and List of tallest buildings and structures in the Paris region

The architecture in Paris has been constrained by laws related to the height and shape of buildings at least since the 17th century, to the point that alignement and (often uniformity of height) of buildings is a characteristic and recognizable trait of Paris streets in spite of the evolution of architectural styles. However, a large part of contemporary Paris has been affected by the vast mid-19th century urban remodelling.

By the middle of the 19th century, the centre of the city was a labyrinth of narrow, winding streets, without sidewalks, between crumbling four and five story buildings; many neighbourhoods were dark, unhealthy, and dangerous. Beginning in 1853, Napoleon III and his préfet de Seine Georges-Eugène Haussmann, demolished two thousand buildings and eliminated forty streets, and built two hundred kilometres of wide new boulevards, squares and parks, along with sidewalks, sewers, and street lighting. Haussmann established standards for the height, general design and the materials used for the buildings along the new boulevards, giving the centre of Paris the distinct unity and look that it has today.

The building code has been slightly relaxed since the 1850s, but the Second Empire plans are in many cases more or less followed. An "alignement" law is still in place, which regulates a building's height according to the width of the streets it borders, and under the regulation, it is almost impossible to get an approval to build a taller building. However, specific authorizations allowed for the construction of many high-rise buildings in the 1960s and early 1970s, most of them limited to a height of 100 m, in peripheral arrondissements.

Churches are the oldest intact buildings in the city, and show high Gothic architecture at its best—Notre Dame cathedral and the Sainte-Chapelle are two of the most striking buildings in the city. The latter half of the 19th-century was an era of architectural inspiration, with buildings such as the Basilique du Sacré-Cœur, built between 1875 and 1919 in a neo-Byzantine design. Paris' most famous architectural piece, the Eiffel Tower, was built as a temporary exhibit for the 1889 World Fair and remains an enduring symbol of the capital with its iconic structure and position, towering over much of the city. Many of Paris' important institutions are located outside the city limits; the financial business district is in La Défense, and many of the educational institutions lie in the southern suburbs.

Landmarks by district

Main articles: Landmarks in the City of Paris, Paris districts, and List of visitor attractions in ParisThe 1st arrondissement, on the right bank of the Seine and partly on Île de la Cité (which it shares with the 4th arrondissement), forms much of the historic centre of Paris. The Louvre, Palais de Justice, Sainte-Chapelle, Conciergerie are among Paris' oldest buildings. The 1st arrondissement is also home to Palais-Royal, Comédie-Française, Musée de l'Orangerie, Théâtre du Châtelet. Les Halles were formerly Paris' central meat and produce market and, since the late 1970s, have been a major shopping centre. Place Vendôme is famous for its elegant hôtels particuliers, such as the Hôtel de Gramont (18th century), now the luxurious palace-hotel Ritz, the Hôtel Duché des Tournelles (18th century), which now belongs to Chanel. The Hôtel de Toulouse (17th century), near Place des Victoires, the Parisian residence of the Comte de Toulouse, is since 1811 the seat of the Banque de France. Luxury hotels such as The Westin Paris – Vendôme, the Hôtel Meurice, and the Hôtel Regina are also located in the 1st arrondissement, all close to the Tuileries Gardens. The Axe historique (historical axis), is an unobstructed line of monuments that begins in the 1st arrondissement at the equestrian statue of Louis XIV in the Cour Napoléon of the Louvre, runs east to west through the center of the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel, the Tuileries Garden, the Luxor Obelisk at the center of Place de la Concorde, Champs-Élysées, Arc de Triomphe de l'Étoile, Avenue de la Grande Armée, Pont de Neuilly and ends at La Grande Arche de la Défense in Puteaux. With its start in the 1st arrondissement, the Axe historique crosses the 8th, then the border between the 16th and 17th arrondissements before continuing its straight course outside of Paris.

The 2nd arrondissement, on the right bank, lies to the north of the 1st and is overlapping into the 3rd. It is the theatre district of Paris, with the Théâtre des Capucines, Théâtre-Musée des Capucines, Opéra-Comique, Théâtre des Variétés, Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens, Théâtre du Vaudeville and Théâtre Feydeau. Also of note are the Académie Julian, Bibliothèque nationale de France (former Palais Mazarin, 17th century), Café Anglais and Galerie Vivienne. Boulevard des Capucines, Boulevard Montmartre, Boulevard des Italiens, Rue de Richelieu and Rue Saint-Denis are major thoroughfares running through the district.

The 3rd arrondissement is located to the north-east of the 1st, on the right bank of the Seine. It is a culturally open place with Chinese, Jewish and gay communities, and architecturally very well preserved. At 51 rue de Montmorency, stands the oldest house of Paris, the Maison de Nicolas Flamel, built in 1407. Museums are in former hôtels particuliers: the Musée des Archives nationales (Hôtel de Soubise, 16th and 17th centuries), the Musée Carnavalet (Hôtel Le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau, 17th century). The Musée des Arts et Métiers (Saint-Martin-des-Champs Priory, 12th/20th centuries). The Musée d'art et d'histoire du Judaïsme (Hôtel de Saint-Aignan, 17th century) and the Musée Picasso (Hôtel Salé, 17th century) are in Le Marais, a trendy district spanning the 3rd and 4th arrondissements. Two well-known theatres are Théâtre Déjazet and Théâtre du Marais. Place des Vosges, the oldest planned square in Paris, built by Henry IV at the turn of the 17th century, lies at the border of the 3rd and 4th arrondissements. The 3rd arrondissement extends to Place de la République (former Place du Château d'eau), which it shares with the 10th and 11th arrondissements.

The 4th arrondissement, on the right bank of the Seine and also the eastern part of Île de la Cité and Île Saint-Louis, is located to the east of the 1st. The 12th-century cathedral Notre Dame de Paris on the Île de la Cité is the best-known landmark of the 4th arrondissement. Among other notable monuments are the Hôtel de Ville, Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal, Centre Georges Pompidou, also known as Beaubourg, . In Le Marais, the Bibliothèque historique de la ville de Paris, Centre des monuments nationaux (Hôtel de Sully, 17th century), La Force Prison (demolished in 1845), Lycée Charlemagne, Maison de Victor Hugo (Place des Vosges), the Mémorial de la Shoah, and others. Place de la Bastille (4th, 11th and 12th arrondissements, right bank) is a district of great historical significance, for not just Paris, but for all of France. Because of its symbolic value, the square is often the site of political demonstrations. In its center, stands the Colonne de Juillet commemorating the July 1830 revolution.

The 5th arrondissement, on the left bank, contains the Quartier Latin (also spanning the 6th), a 12th-century scholastic centre, formerly stretching between the left bank's Place Maubert and the Sorbonne campus of the University of Paris, its oldest and most famous college. It also houses other higher-education establishments, such as the Collège de France, Collège Sainte-Barbe, Collège international de philosophie, École Normale Supérieure, Lycée Henri-IV, Lycée Louis-le-Grand. Of high interest are also the Arènes de Lutèce, Musée national du Moyen Âge, Institut Curie, the Val-de-Grâce, Jardin des Plantes, the church Saint-Nicolas-du-Chardonnet, the Mosquée de Paris, the Institut du Monde Arabe. The Panthéon is a mausoleum where many of France's illustrious personalities are buried: 70 men and two women: Marie Curie and Sophie Berthelot. In addition to places of learning and monuments, the 5th arrondissement, known for its lively atmosphere, is filled with bookstores, restaurants, cafés, places of entertainment such as the Théâtre de la Huchette, Le Caveau de la Huchette (a jazz club), and others.

The 6th arrondissement, to the south of the centre and on the left bank of the Seine, has numerous hotels, cafés, restaurants, cinémas and also educational institutions. One of the most expensive residential districts of Paris per square meter, it includes the Luxembourg Palace (Palais du Luxembourg) and the Saint-Germain-des-Prés quarter. Adjoining the Palais du Luxembourg is the renowned Jardin du Luxembourg (with a replica of the Statue of Liberty offered by its creator Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi in 1900). Although not as many as its neighbouring 5th arrondissement, the 6th holds several prestigious institutions, such as the Institut de France, the Théâtre de l'Odéon, the Académie Nationale de Médecine, Lycée Fénelon, Lycée Montaigne, Lycée Saint-Louis, the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts. The Saint-Germain-des-Prés quarter was named after the medieval Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Some of its main points of interest are cafés such as Les Deux Magots, Café de Flore, Café Procope and also Brasserie Lipp. The Hôtel de Chimay and Hôtel de Vendôme (which houses the École nationale supérieure des mines de Paris), are former hôtels particuliers.

The 7th arrondissement lies to the southwest of the centre, on the left bank of the Seine. Like the sixth, it is one of the most expensive residential districts of Paris. Its main tourist attraction, the Eiffel Tower (Tour Eiffel), was built as a "temporary" construction for the 1889 Exposition universelle. Among other monuments and historical landmarks of the 7th arrondissement are, the Champ de Mars, École militaire, Les Invalides, where are buried Napoleon I, his son, Napoleon II, known as the Roi de Rome, as well as France's great field marshals, generals and war heroes. Also in the 7th arrondissement are the Palais Bourbon, which houses the Assemblée nationale, the Hôtel Matignon, official residence of the Prime Minister, most of the important ministries (agriculture, defence, education, foreign affairs, health, transports), several embassies, the Musée d'Orsay and the Hôtel Biron, an 18th-century hôtel particulier, which houses the Musée Rodin.

The 8th arrondissement, on the right bank, is bordered by the 1st and 9th arrondissements (east), the 16th (west), the 17th (north), and the 7th across the Seine (south). It is a highly touristic and business area of Paris with shopping and elegant streets, such as Rue Royale, Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, Avenue George V, Avenue Montaigne, Avenue des Champs-Élysées, streets and avenues that host world-renowned labels: Dior, Christian Lacroix, Sephora, Lancel, Louis Vuitton, Guerlain, as well as Mercedes-Benz, Renault, Toyota. Several former hôtels particuliers or princely residences have now become government buildings: in the rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, the Élysée Palace, residence of the President of the Republic, the Embassy of Canada and the Hôtel de Pontalba, residence of the United States Ambassador to France; in the Avenue Marigny, the Hôtel de Marigny, residence of visiting high foreign dignitaries; on Place de la Concorde, the Hôtel de la Marine, which houses the headquarters of the French Navy, with its twin building to the west, the Hôtel de Crillon, a luxury hotel owned by the king of Saudi Arabia and which faces the Embassy of the United States. Among its historical landmarks are the Arc de Triomphe de l'Étoile, La Madeleine church, Gare Saint-Lazare, the museums Grand Palais and Petit Palais, Palais de la Découverte, the Pont Alexandre III, the Théâtre des Champs Élysées, the concert halls Salle Gaveau and Salle Pleyel, cabarets Le Lido and Crazy Horse, luxury hotels, such as Le Bristol, and several renowned restaurants, among which Les Ambassadeurs, Fouquet's, Ledoyen, Maxim's and Taillevent.

The 9th arrondissement, north of the heart of Paris, on the right bank, is a district where stands the renowned Opéra Garnier built in the later Second Empire period, on the Place de l'Opéra. It houses the Paris Opera and the Paris Opera Ballet. Among the theatres, cinemas, music halls, concert halls, cafés and museums of the 9th arrondissement are Théâtre de l'Athénée-Louis-Jouvet, Théâtre de Paris, the cinema Gaumont-Opéra, since 1927 on the site of the former Théâtre du Vaudeville, Casino de Paris, Folies Bergère, Olympia, Café de la Paix, Grand Café Capucines, Musée Grévin, Musée de la Vie Romantique, Musée du Parfum de Fragonard, and Musée national Gustave Moreau. The 9th arrondissement is also the location of the Grand Synagogue of Paris, and the capital's densest concentration of department stores and office buildings including the Printemps and Galeries Lafayette department stores, and the Paris headquarters of BNP Paribas and American Express.

The 10th arrondissement, on the right bank, lies north-east of the centre and is a continuation of the theatre district with several theatres including Théâtre Antoine-Simone Berriau, Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord and Théâtre de la Renaissance. Also of note are Musée de l'Éventail, Hôpital Saint-Louis, The Kurdish Digital Library, Lariboisière Hospital, Lycée Edgar-Poe, Prison Saint-Lazare and the Saint-Laurent and Saint-Vincent-de-Paul churches. The Alhambra music hall opened in 2008. The train stations Gare de Paris-Nord and Gare de Paris-Est are both located in the 10th arrondissement. At 39, rue du Château-d'Eau is Paris smallest house with a width of 1,10 m and a height of 5 metres.

The 11th arrondissement, on the right bank, is located west of the 20th arrondissement in the eastern part of Paris. It contains the squares Place de la Nation, Place de la République, Place du 8 Février 1962, the theatres Bataclan, Théâtre des Folies-Dramatiques, Théâtre de l'Ambigu-Comique, Théâtre des Délassements-Comiques, Théâtre de la Bastille and Théâtre des Funambules, the museums Musée du Fumeur and Musée Édith Piaf, and the La Roquette Prisons (closed in 1974).

The 12th arrondissement, on the right bank in the south-eastern suburbs of Paris, is separated from the 13th by the Seine with several bridges. The district contains Place de la Bastille and Place de la Nation (bordering the 11th), with Boulevard de la Bastille one of its main thoroughfares, the train station Paris-Gare de Lyon, Palais Omnisports de Paris-Bercy, Hôpital Saint-Antoine, the former 12th century Saint-Antoine-des-Champs abbey converted into a hospital in 1791 during the Convention period of the French Revolution, Picpus Cemetery, Parc de Bercy, Bois de Vincennes, the Buddhist temples Kagyu-Dzong and Pagode de Vincennes, Opéra Bastille, the main facility of the Paris National Opera, whose architect was the Uruguayan Carlos Ott, was inaugurated in 1989 as part of President François Mitterrand’s “Grands Travaux”.

The 13th arrondissement, on the left bank, lies on the southeast of Paris, south of the 5th, east of the 14th and west of the 12th, with the Seine separating these two arrondissements. It contains the Quartier Asiatique (Asian Quarter), Floral City, Butte-aux-Cailles, the Italie 2 shopping centre with some 130 stores, the train station Gare d'Austerlitz, the tapestry making Gobelins Manufactory and institutions such as the Bibliothèque nationale de France and École Estienne.

The 14th arrondissement, on the left bank and in the southern part of Paris, between the 13th (on its east) and the 15th (on its west), bordered on its north by the 5th and 6th arrondissements, contains the historic Quartier Montparnasse famous for its artists' studios, music halls, theatres (Théâtre Montparnasse), cinemas, restaurants (La Coupole) and café life. The Montparnasse Cemetery, the large Montparnasse – Bienvenüe metro station adjacent to Gare Montparnasse train station (sharing its location with the 15th), and the lone 59-story skyscraper Tour Maine-Montparnasse are located there. Among other sites of interest are the Catacombs of Paris, with entrance at Place Denfert-Rochereau, the Paris Observatory, the Cité Internationale Universitaire de Paris, La Santé Prison and Parc Montsouris.

The 15th arrondissement, on the left bank and in the south-western part of the city, is the most heavily populated arrondissement. It is has six bridges, among which Pont du Garigliano, Pont Mirabeau, and Pont aval (reserved for automobile traffic only). A number of institutions are based in the 15th arrondissement including the hospitals Hôpital Européen Georges-Pompidou and Necker-Enfants Malades Hospital, and the French automobile company Citroën had several factories which were replaced by the Parc André Citroën. There are above forty espaces verts, i.e. public gardens, squares and open spaces, in the 15th, among which, the Allée des Cygnes on the Île aux Cygnes, the Jardin Atlantique, created on the roof covering the platform above the rails at the Gare Montparnasse train station, the Parc Georges-Brassens, with the reputation of being one of the most beautiful of the arrondissement. The Palais des Sports was built in 1960 to replace the old Vel’ d’Hiv and has hosted many notable spectacles over the years, such as musical events, boxing matches, the Moscow Circus, and more. The business district Val de Seine, straddling the 15th arrondissement and the communes of Issy-les-Moulineaux and Boulogne-Billancourt to the south-west of central Paris, is the new media hub of Paris and France, hosting the headquarters of most of France's TV networks such as TF1, France 2 and Canal+.

The 16th arrondissement, on the right bank and marking the western side of the city, is the largest district of Paris. It lies between the 15th and 7th arrondissements (on its east and separated by the Seine), the 8th and 17th (north) up to Place Charles de Gaulle, the Bois de Boulogne (west), and the suburb of Boulogne-Billancourt (south). It is a wealthy residential district, where are located many embassies and consulates, several museums and theatres, Radio France and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Sport installations, such as the Parc de Princes, home of the football club Paris Saint-Germain F.C., the Stade Roland Garros, which hosts the annual French Open tennis tournament, the Tennis Club de Paris, the Stade de Paris rugby club, Longchamp Racecourse, and the Auteuil Hippodrome, a horse racing venue established in 1873 and which hosted the equestrian events of the 1924 Summer Olympics, are in the 16th arrondissement. Among the many points of interest are the Jardins du Trocadéro between the Eiffel Tower (in the 7th, on the other side of the Seine) and the Palais de Chaillot, which also houses the Musée national de la Marine, the Musée d'art moderne de la ville de Paris, Palais de Tokyo, Musée Marmottan Monet, the Jardin d'acclimatation, Passy Cemetery, the Parc de Bagatelle, in the Bois de Boulogne, with its beautiful rose garden, the Roseraie de Bagatelle created in 1905, and which is the site every June of the Concours international de roses nouvelles de Bagatelle, an international competition of newly created roses. The 16th arrondissement has also been the site of the shooting of many films.

The 17th arrondissement, on the right bank, is on the north-west side of Paris, bordering the suburbs of Neuilly-sur-Seine and Levallois-Perret (west), Clichy-la-Garenne and Saint-Ouen (north), 18th arrondissement (east), and 16th (south), from which it is separated by the avenue de la Grande-Armée which leads beyond Neuilly-sur-Seine to the Arche de la Défense, the western end of the Axe historique, in La Défense business district. Like the arrondissements surrounding it (except the 18th), the 17th is a wealthy residential district home to several embassies. It has several squares, including Place Charles de Gaulle (meeting point of the 8th, 16th and 17th arrondissements), Place de Wagram, Place des Ternes, and green spaces, such as Square des Batignolles, not far from the Parc Clichy-Batignolles - Martin Luther King, in the Batignolles quarter, and the Batignolles Cemetery (which has some 900 trees), in the Épinettes quarter.

The 18th arrondissement, on the right bank and on the northern edge of the city, is also the capital's highest point, with an altitude of 130,53 metres. It borders the 17th arrondissement (west), the 9th and 10th (south), the 19th (east) and the Seine-Saint-Denis department (north). It includes the former village of Montmartre, a historic area on the hill Butte Montmartre, associated with artists, studios and cafés. After the 15th, it is the most populated arrondissements of Paris. Some of its interesting landmarks are the Basilique du Sacré-Cœur (most visited monument in France after Notre Dame cathedral), the windmill Moulin de la galette, the cabarets Moulin Rouge and Lapin Agile, the bar-restaurant theatre Les Trois Baudets, Quartier Pigalle, the market Marché de La Chapelle and the Montmartre Cemetery, one of the three largest cemeteries in Paris.

The 19th arrondissement, on the right bank and on the northeastern edge of the city, is bordered on the north by the suburb of Aubervilliers, on the east by those of Pantin, Les Lilas and Le Pré-Saint-Gervais, on the south by the 20th arrondissement, and on the west by the 18th and 10th. Several canals run through the 19th arrondissement: Canal Saint-Martin becomes Canal de l'Ourcq below the Place de la Bataille-de-Stalingrad, which commemorates the WWII Battle of Stalingrad. The Conservatoire national supérieur de musique et de danse de Paris, a prestigious music and dance school, established in 1795, is located in the 19th arrondissement, as are the cultural centre Cent Quatre, and several theatres: Théâtre Paris-Villette, Théâtre des Artisans, and Théâtre Darius Milhaud. The Zénith de Paris, one of the largest concert halls in Paris with a capacity of 6,293 spectators, is located in Parc de la Villette, one of several parks and green spaces in the 19th arrondissement with Parc des Buttes Chaumont and Square de la Butte-du-Chapeau-Rouge.

The 20th arrondissement, on the right bank and on the eastern edge of the city, is bordered to the north by the 19th arrondissement, to the east by the suburbs of Les Lilas, Bagnolet, Montreuil and Saint-Mandé, to the south by the 12th arrondissement and to the west by the 11th. It contains the neighbourhood of Belleville, a working-class neighbourhood, which includes the quartier Ménilmontant, close to the Paris of artists, writers and singers such as Maurice Chevalier, Charles Trenet, Édith Piaf, Simone Signoret, Yves Montand, to name a few. Among films shot in that part of Paris is Le Ballon rouge. During the first half of the 20th century, right after the end of the First World War, many immigrants settled in this area: Armenians, Poles, Jews from central Europe, German Jews fleeing the Third Reich in 1933, and Spaniards fleeing the Franco regime during the 1936-1939 Spanish Civil War. Algerians and Tunisian Jews arrived in the early 1960s. Belleville is home to one of the largest congregations of the Reformed Church of France, and contains the Église Réformée de Belleville. Place of interests of the 20th arrondissement are the cimetière du Père-Lachaise, one of Paris most famous cemeteries, and the nearby Parc de Belleville.

Parks and gardens

Main articles: List of parks and gardens in Paris and History of Parks and Gardens of Paris

Paris today has more than 421 municipal parks and gardens, covering more than three thousand hectares and containing more than 250,000 trees. Two of Paris' oldest and most famous gardens are the Tuileries Garden, created in 1564 for the Tuileries Palace, and redone by André Le Nôtre between 1664 and 1672, and the Luxembourg Garden, for the Luxembourg Palace, built for Marie de' Medici in 1612, which today houses the French Senate. The Jardin des Plantes was the first botanical garden in Paris, created in 1626 by Louis XIII's doctor Guy de La Brosse for the cultivation of medicinal plants. Between 1853 and 1870, the Emperor Napoleon III and the city's first director of parks and gardens, Jean-Charles Alphand, created the Bois de Boulogne, the Bois de Vincennes, Parc Montsouris and the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont, located at the four points of the compass around the city, as well as many smaller parks, squares and gardens in the Paris' quarters. One hundred sixty-six new parks have been created since 1977, most notably the Parc de la Villette (1987-1991) and Parc André Citroën (1992). The newest park in Paris, the Promenade des Berges de la Seine, built on a former highway on the left bank of the Seine between the Pont de l'Alma and the Musée d'Orsay, offers floating gardens and an exceptional view of the city's landmarks.

Water and sanitation

Paris in its early history had only the Seine and Bièvre rivers for water. From 1809, the canal de l'Ourcq provided Paris with water from less-polluted rivers to the north-east of the capital. From 1857, the civil engineer Eugène Belgrand, under Napoleon III, oversaw the construction of a series of new aqueducts that brought water from locations all around the city to several reservoirs built atop the Capital's highest points of elevation. From then on, the new reservoir system became Paris' principal source of drinking water, and the remains of the old system, pumped into lower levels of the same reservoirs, were from then on used for the cleaning of Paris' streets. This system is still a major part of Paris' modern water-supply network. Today Paris has over 2,400 km (1,491 mi) of underground passageways dedicated to the evacuation of Paris' liquid wastes.

In 1982, the then mayor, Jacques Chirac, introduced the motorcycle-mounted Motocrotte to remove dog faeces from Paris streets. The project was abandoned in 2002 for a new and better enforced local law, under the terms of which dog owners can be fined up to 500 euros for not removing their dog faeces. The air pollution in Paris, from the point of view of particulate matter (pm10), is the highest in France, with 38 µg/m³.

Cemeteries

In Paris' Roman era, its main cemetery was located to the outskirts of the left bank settlement, but this changed with the rise of Catholicism, where most every inner-city church had adjoining burial grounds for use by their parishes. With Paris' growth many of these, particularly the city's largest cemetery, les Innocents, were filled to overflowing, creating quite unsanitary conditions for the capital. When inner-city burials were condemned from 1786, the contents of all Paris' parish cemeteries were transferred to a renovated section of Paris' stone mines outside the "Porte d'Enfer" city gate, today place Denfert-Rochereau in the 14th arrondissement. The process of moving bones from Cimetière des Innocents to the catacombs took place between 1786 and 1814; part of the network of tunnels and remains can be visited today on the official tour of the catacombs. After a tentative creation of several smaller suburban cemeteries, the Prefect Nicholas Frochot under Napoleon Bonaparte provided a more definitive solution in the creation of three massive Parisian cemeteries outside the city limits. Open from 1804, these were the cemeteries of Père Lachaise, Montmartre, Montparnasse, and later Passy; these cemeteries became inner-city once again when Paris annexed all neighboring communes to the inside of its much larger ring of suburban fortifications in 1860. New suburban cemeteries were created in the early 20th century: The largest of these are the Cimetière parisien de Saint-Ouen, the Cimetière parisien de Pantin (also known as Cimetière parisien de Pantin-Bobigny, the Cimetière parisien d'Ivry, and the Cimetière parisien de Bagneux.

Culture

Main article: Culture of ParisArt

Main article: Art in ParisPainting and sculpture

For centuries, Paris has attracted foreign artists arriving in the city to share their creativity, educate themselves, or seek inspiration from its vast pool of artistic resources and galleries. As a result, Paris has acquired a reputation as the "City of Art". Italian artists were a profound influence on the development of art in Paris in the 16th and 17th centuries, particular in sculpture and reliefs. In 1648, the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture) was established to accommodate for the dramatic interest in art in the capital. This served as France's top art school until 1793. Painting and sculpture became the pride of the French monarchy, and the French royals and wealthy aristocrats commissioned French (and foreign) artists to adorn their palaces during the French Baroque and Classicism era. Sculptors such as François Girardon, Antoine Coysevox, Nicolas Coustou, Edmé Bouchardon, were among the finest at the royal court in 17th and 18th centuries France. Nicolas Poussin, Charles Le Brun and Pierre Mignard succeeded one another as Premier peintre du Roi ("First Painter to the King") to Louis XIV. At the end of the 18th century, the French Revolution, which brought political and social changes in France, had a profound influence on art in the capital. Paris was in its artistic prime in the 19th century and central to the development of Romanticism in art, with painters such as Géricault, Ingres, Jean-Baptiste Isabey and Eugène Isabey, father and son, Fantin-Latour. In the late 19th and early 20th century, Paris had a colony of artists established in the city, with art schools associated with some of the finest painters of the times - Manet, Monet, Berthe Morisot, Gauguin, Albert Gleizes, Renoir and so many more - when Impressionism, Expressionism, Fauvism and Cubism movements evolved. In the late 19th century, artists from the French provinces and worldwide flocked to Paris to exhibit their works in the numerous salons and expositions, and to make a name for themselves. Painters such as Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, Jean Metzinger, María Blanchard, Henri Rousseau, Marc Chagall, Amedeo Modigliani (painter and sculptor), Bernard Buffet and many others became associated with Paris. Montparnasse and Montmartre became centers for artistic production. The most prestigious names of French and foreign sculptors, who made their reputation in Paris in the modern era, are Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi (Statue of Liberty), Auguste Rodin, Camille Claudel, Paul Landowski (statue of Christ the Redeemer in Rio de Janeiro), Aristide Maillol. The Golden Age of the Paris School ended with World War II, but Paris remains extremely important to the art world and art schooling, with institutions ranging from the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, the former Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, to the American Paris College of Art.

Museums

Main article: List of museums in ParisThe Louvre is the world's most visited art museum, housing many works of art, including the Mona Lisa (La Joconde) and the Venus de Milo statue. There are hundreds of museums in Paris. Works by Pablo Picasso and Auguste Rodin are found in the Musée Picasso and the Musée Rodin, respectively, while the artistic community of Montparnasse is chronicled at the Musée du Montparnasse. Starkly apparent with its service-pipe exterior, the Centre Georges Pompidou, also known as Beaubourg, houses the Musée National d'Art Moderne.

Art and artefacts from the Middle Ages and Impressionist eras are kept in the Musée de Cluny and the Musée d'Orsay, respectively, the former with the prized tapestry cycle The Lady and the Unicorn. Paris' newest (and third-largest) museum, the Musée du quai Branly, opened its doors in June 2006 and houses art from Africa, Asia, Oceania, and the Americas, including many from Mesoamerican cultures.

Photography

Paris has attracted communities of photographers, and was an important centre for the development of photography. Numerous photographers achieved renown for their photography of Paris, including Eugène Atget, noted for his depictions of early-19th-century street scenes; the early 20th-century surrealist movement's Man Ray; Robert Doisneau, noted for his playful pictures of 1950s Parisian life; Marcel Bovis, noted for his night scenes, and others such as Jacques-Henri Lartigue and Cartier-Bresson. Paris also become the hotbed for an emerging art form in the late 19th century, poster art, advocated by the likes of Gavarni.

Literature

Countless books and novels have been set in Paris. Victor Hugo's The Hunchback of Notre Dame, is one of the best known. The book was received so rapturously that it inspired a series of renovations of its setting, the Notre-Dame de Paris. Another of Victor Hugo's works, Les Misérables is set in Paris, against the backdrop of slums and penury. Another immortalised French author, Honoré de Balzac, completed a good number of his works in Paris, including his masterpiece La Comédie humaine. Other Parisian authors (by birth or residency) include Alexandre Dumas (The Three Musketeers, The Count of Monte Cristo, The Vicomte of Bragelonne: Ten Years Later),