| Revision as of 06:22, 18 January 2015 edit7157.118.25a (talk | contribs)705 edits →External links: categories← Previous edit | Revision as of 06:35, 18 January 2015 edit undoBinksternet (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, File movers, Pending changes reviewers495,241 edits trim categories which are not foundationalNext edit → | ||

| Line 335: | Line 335: | ||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Sex-Selective Abortion}} | {{DEFAULTSORT:Sex-Selective Abortion}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

Revision as of 06:35, 18 January 2015

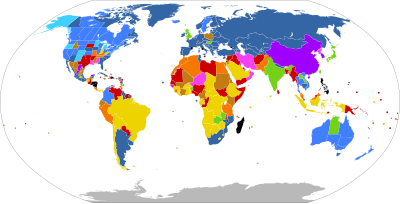

Sex-selective abortion is the practice of terminating a pregnancy based upon the predicted sex of the baby. The selective abortion of female fetuses is most common in areas where cultural norms value male children over female children, especially in parts of People's Republic of China, India, Pakistan, the Caucasus, and Southeast Europe.

Sex-selective abortion affects the human sex ratio — the relative number of males to females in a given age group. Studies and reports focusing on sex-selective abortion are predominantly statistical; they assume that birth sex ratio — the overall ratio of boys and girls at birth for a regional population, is an indicator of sex-selective abortion. This assumption has been questioned by some scholars.

Scholars who support the assumption suggest that the expected birth sex ratio range is 103 to 107 males to females at birth. Countries considered to have significant practices of sex-selective abortion are those with birth sex ratios of 108 and above (selective abortion of females), and 102 and below (selective abortion of males). See list of countries by sex ratio.

The overall impact of ultrasound screening and sex-selective abortion on female population is a topic of active debate. Ultrasound sex-screening technologies became widely available in Asian countries during the 1980s and 1990s, and estimates of its impact on missing women vary. Ross Douthat claims over 160 million females are "missing" because of ultrasound screening followed by sex-selective abortion. Guilmoto claims about 40 million females are missing from Asia, Caucasus and Europe.

Human sex ratio at birth

Main article: Human sex ratio

Sex-selective abortion affects the human sex ratio — the relative number of males to females in a given age group. Studies and reports that discuss sex-selective abortion are based on the assumption that birth sex ratio — the overall ratio of boys and girls at birth for a regional population, is an indicator of sex-selective abortion.

The natural human sex ratio at birth was estimated, in a 2002 study, to be close to 106 boys to 100 girls. Human sex ratio at birth that is significantly different from 106 is often assumed to be correlated to the prevalence and scale of sex-selective abortion. This assumption is controversial, and a subject of continuing scientific studies.

High or low human sex ratio implies sex-selective abortion

One school of scholars suggest that any birth sex ratio of boys to girls that is outside of the normal 105-107 range, necessarily implies sex-selective abortion. These scholars claim that both the sex ratio at birth and the population sex ratio are remarkably constant in human populations. Significant deviations in birth sex ratios from the normal range can only be explained by manipulation, that is sex-selective abortion.

In a widely cited article, Amartya Sen compared the birth sex ratio in Europe (106) and United States (105) with those in Asia (107+) and argued that the high sex ratios in East Asia, West Asia and South Asia may be due to excessive female mortality. Sen pointed to research that had shown that if men and women receive similar nutritional and medical attention and good health care then females have better survival rates, and it is the male which is the genetically fragile sex.

Sen estimated 'missing women' from extra women who would have survived in Asia if it had the same ratio of women to men as Europe and United States. According to Sen, the high birth sex ratio over decades, implies a female shortfall of 11% in Asia, or over 100 million women as missing from the 3 billion combined population of South Asia, West Asia, North Africa and China.

High or low human sex ratio may be natural

Other scholars question whether birth sex ratio outside 103-107 can be due to natural reasons. William James and others suggest that conventional assumptions have been:

- there are equal numbers of X and Y chromosomes in mammalian sperms

- X and Y stand equal chance of achieving conception

- therefore equal number of male and female zygotes are formed, and that

- therefore any variation of sex ratio at birth is due to sex selection between conception and birth.

James cautions that available scientific evidence stands against the above assumptions and conclusions. He reports that there is an excess of males at birth in almost all human populations, and the natural sex ratio at birth is usually between 102 to 108. However the ratio may deviate significantly from this range for natural reasons such as early marriage and fertility, teenage mothers, average maternal age at birth, paternal age, age gap between father and mother, late births, ethnicity, social and economic stress, warfare, environmental and harmonal effects. This school of scholars support their alternate hypothesis with historical data when modern sex-selection technologies were unavailable, as well as birth sex ratio in sub-regions, and various ethnic groups of developed economies. They suggest that direct abortion data should be collected and studied, instead of drawing conclusions indirectly from human sex ratio at birth.

James hypothesis is supported by historical birth sex ratio data before technologies for ultrasonographic sex-screening were discovered and commercialized in the 1960s and 1970s, as well by reverse abnormal sex ratios currently observed in Africa. Michel Garenne reports that many African nations have, over decades, witnessed birth sex ratios below 100, that is more girls are born than boys. Angola, Botswana and Namibia have reported birth sex ratios between 94 to 99, which is quite different than the presumed 104 to 106 as natural human birth sex ratio.

John Graunt noted that in London over a 35-year period in the 17th century (1628–1662), the birth sex ratio was 1.07; while Korea's historical records suggest a birth sex ratio of 1.13, based on 5 million births, in 1920s over a 10-year period. Other historical records from Asia too support James hypothesis. For example, Jiang et al. claim that the birth sex ratio in China was 116–121 over a 100-year period in the late 18th and early 19th centuries; in the 120–123 range in the early 20th century; falling to 112 in the 1930s.

Data on human sex ratio at birth

Main article: List of countries by sex ratioIn the United States, the sex ratios at birth over the period 1970–2002 were 105 for the white non-Hispanic population, 104 for Mexican Americans, 103 for African Americans and Native Indians, and 107 for mothers of Chinese or Filipino ethnicity. Among Western European countries c. 2001, the ratios ranged from 104 to 107. In the aggregated results of 56 Demographic and Health Surveys in African countries, the birth sex ratio was found to be 103, though there is also considerable country-to-country, and year-to-year variation.

In a 2005 study, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services reported sex ratio at birth in the United States from 1940 over 62 years. This statistical evidence suggested the following: For mothers having their first baby, the total sex ratio at birth was 106 overall, with some years at 107. For mothers having babies after the first, this ratio consistently decreased with each additional baby from 106 towards 103. The age of the mother affected the ratio: the overall ratio was 105 for mothers aged 25 to 35 at the time of birth; while mothers who were below the age of 15 or above 40 had babies with a sex ratio ranging between 94 to 111, and a total sex ratio of 104. This United States study also noted that American mothers of Hawaiian, Filipino, Chinese, Cuban and Japanese ethnicity had the highest sex ratio, with years as high as 114 and average sex ratio of 107 over the 62-year study period. Outside of United States, European nations with extensive birth records, such as Finland, report similar variations in birth sex ratios over a 250-year period, that is from 1751 to 1997 AD.

In 2013, according to CIA estimates, some countries with high birth sex ratio were Liechtenstein (126), Curacao (115), Azerbaijan (113), Armenia (112), China (112), India (112), Vietnam (112), Georgia (111), Albania (111), Grenada (110), San Marino (109), Taiwan (109), Jersey (108), Kosovo (108), Macedonia (108) and Singapore (108). Low boys to girls birth sex ratios in 2013 were estimated by CIA for Haiti (101), Barbados (101), Bermuda (101), Cayman Islands (102), Qatar (102), Kenya (102), Malawi (102), Mozambique (102), South Africa (102) and Aruba (102).

Data reliability

The estimates for birth sex ratios, and thus derived sex-selective abortion, are a subject of dispute as well. For example, United States' CIA projects the birth sex ratio for Switzerland to be 106, while the Switzerland's Federal Statistical Office that tracks actual live births of boys and girls every year, reports the latest birth sex ratio for Switzerland as 107. Other variations are more significant; for example, CIA projects the birth sex ratio for Pakistan to be 105, United Nations FPA office claims the birth sex ratio for Pakistan to be 110, while the government of Pakistan claims its average birth sex ratio is 111.

The two most studied nations with high sex ratio and sex-selective abortion are China and India. The CIA estimates a birth sex ratio of 112 for both in recent years. However, The World Bank claims the birth sex ratio for China in 2009 was 120 boys for every 100 girls; while United Nations FPA estimates China's 2011 birth sex ratio to be 118.

For India, the United Nations FPA claims a birth sex ratio of 111 over 2008–2010 period, while The World Bank and India's official 2011 Census reports a birth sex ratio of 108. These variations and data reliability is important as a rise from 108 to 109 for India, or 117 to 118 for China, each with large populations, represent a possible sex-selective abortion of about 100,000 girls.

Prenatal sex discernment

Main article: Prenatal sex discernment

The earliest post-implantation test, cell free fetal DNA testing, involves taking a blood sample from the mother and isolating the small amount of fetal DNA that can be found within it. When performed after week seven of pregnancy, this method is about 98% accurate.

Obstetric ultrasonography, either transvaginally or transabdominally, checks for various markers of fetal sex. It can be performed at or after week 12 of pregnancy. At this point, 3⁄4 of fetal sexes can be correctly determined, according to a 2001 study. Accuracy for males is approximately 50% and for females almost 100%. When performed after week 13 of pregnancy, ultrasonography gives an accurate result in almost 100% of cases.

The most invasive measures are chorionic villus sampling (CVS) and amniocentesis, which involve testing of the chorionic villus (found in the placenta) and amniotic fluid, respectively. Both techniques typically test for chromosomal disorders but can also reveal the sex of the child and are performed early in the pregnancy. However, they are often more expensive and more dangerous than blood sampling or ultrasonography, so they are seen less frequently than other sex determination techniques.

- Availability

China launched its first ultrasonography machine in 1979. Chinese health care clinics began introducing ultrasound technologies that could be used to determine prenatal sex in 1982. By 1991, Chinese companies were producing 5,000 ultrasonography machines per year. Almost every rural and urban hospital and family planning clinics in China had a good quality sex discernment equipment by 2001.

The launch of ultrasonography technology in India too occurred in 1979, but its expansion was slower than China. Ultrasound sex discernment technologies were first introduced in major cities of India in the 1980s, its use expanded in India's urban regions in the 1990s, and became widespread in the 2000s.

Prevalence of sex-selective abortion

Caucasus

Before the collapse of Soviet Union in the early 1990s, the birth sex ratio in Caucasus countries such as Azerbaijan, Armenia and Georgia was in the 105 to 108 range. After the collapse, the birth sex ratios sharply climbed and have remained high for the last 20 years. In Christian Armenia and Islamic Azerbaijan currently more than 115 boys are born for every 100 girls, while in Christian Georgia the birth sex ratio is about 120, a trend claims The Economist that suggest sex-selective abortion practice in Caucasus has been similar to those in East Asia and South Asia in recent decades.

For 2005–2010 birth data, the sex ratio in Armenia is seen to be a function of birth order. Among couples having their first child, Armenia averages 138 boys for every 100 girls every year. If the first child is a son, the sex ratio of the second child of Armenian couple averages to be 85. If the first child is a daughter, the sex ratio of the second Armenian child averages to be 156 boys for 100 girls. Overall, the birth sex ratio for in Armenia exceeds 115, far higher than India's 108, claim scholars. While these high birth sex ratios suggest sex-selective abortion, there is no direct evidence of observed large-scale sex-selective abortions in Caucasus.

China

Further information: Missing women of China, Female infanticide in China, and List of Chinese administrative divisions by gender ratio

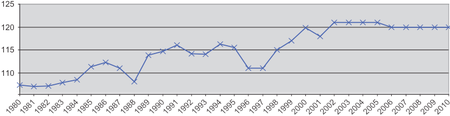

When sex ratio began being studied in China in 1960, it was still within the normal range. However, it climbed to 111.9 by 1990 and to 118 by 2010 per its official census. Researchers believe that the causes of this sex ratio imbalance are increased female infant mortality, underreporting of female births and sex-selective abortion. According to Zeng et al. (1993), the most prominent cause is probably sex-selective abortion, but this is difficult to prove that in a country with little reliable birth data because of the hiding of “illegal” (under the One-Child Policy) births.

These illegal births have led to underreporting of female infants. Zeng et al., using a reverse survival method, estimate that underreporting keeps about 2.26% male births and 5.94% female births off the books. Adjusting for unreported illegal births, they conclude that the corrected Chinese sex ratio at birth for 1989 was 111 rather than 115. These national averages over time, mask the regional sex ratio data. For example, in some provinces such as Anhui, Jiangxi, Shaanxi, Hunan and Guangdong, sex ratio at birth is more than 130.

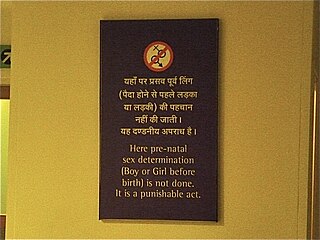

Traditional Chinese techniques have been used to determine sex for hundreds of years, primarily with unknown accuracy. It was not until ultrasonography became widely available in urban and rural China that sex was able to be determined scientifically. In 1986, the Ministry of Health posted the Notice on Forbidding Prenatal Sex Determination, but it was not widely followed. Three years later, the Ministry of Health outlawed the use of sex determination techniques, except for in diagnosing hereditary diseases.

However, many people have personal connections to medical practitioners and strong son preference still dominates culture, leading to the widespread use of sex determination techniques. According to Hardy, Gu, and Xie (2000), ultrasound has spread to all areas of China, as evidenced by the spread of the high sex ratio throughout the country.

Hardy, Gu, and Xie suggest sex-selective abortion is more prevalent in rural China because son preference is much stronger there. Urban areas of China, on average, are moving toward greater equality for both sexes, while rural China tends to follow more traditional views of gender. This is partially due to the belief that, while sons are always part of the family, daughters are only temporary, going to a new family when they marry. Additionally, if a woman’s firstborn child is a son, her position in society moves up, while the same is not true of a firstborn daughter.

In the past, desire for a son was manifested by large birth rates—many couples would continue to have children until they had a son. However, the combination of financial concerns and, more importantly, the One-child policy (discussed further below) have led to an increase in gender planning and selection. Even in rural areas, most women know that ultrasonography can be used for gender discernment. For each subsequent birth, Junhong found that women are over 10% more likely to have an ultrasound (39% for firstborn, 55% for second born, 67% for third born). Additionally, he found that the sex of the firstborn child impacts whether a woman will have an ultrasound in her subsequent pregnancies: 40% of women with a firstborn son have an ultrasound for their second born child, versus 70% of women with firstborn daughters. This points to a strong desire to select for a son if one has not been born yet.

Because of the lack of data about childbirth, a number of researchers have worked to learn about abortion statistics in China. One of the earliest studies by Qui (1987) found that according to cultural belief, fetuses are not thought of as human beings until they are born, leading to a cultural preference for abortion over infanticide. In fact, infanticide and infant abandonment are rather rare in China today. Instead, Junhong found that roughly 27% of women have an abortion. Additionally, he found that if a family’s firstborn was a girl, 92% of known female would-be second born fetuses were aborted.

In a 2005 study, Zhu, Lu, and Hesketh found that the highest sex ratio was for those ages 1–4, and two provinces, Tibet and Xinjiang, had sex ratios within normal limits. Two other provinces had a ratio over 140, four had ratios between 130-139, and seven had ratios between 120-129, each of which is significantly higher than the natural sex ratio.

Variance in the one child policy has led to three types of provinces. Zhu et al. call Type 1, the most restrictive, policy where 40% of couples are permitted to have a second child but generally only if the first is a girl. In Type 2 provinces, any couple is permitted to have a second child if the first born is a girl or if the parents petition “hardship” and the petition is accepted by local officials. Type 3 provinces, typically sparsely populated, allow couples a second child and sometimes a third, irrespective of sex. Zhu et al. find that Type 2 provinces have the highest birth sex ratios, as seen in Henan, Anhui, Jiangxi, Hunan, Guangdong, and Hainan.

High sex ratio trends in China is projected, by 2020, to create a pool of 55 million excess young adult men than women. According to Junhong, many males between the ages of 28 and 49 are unable to find a partner and thus remain unmarried. Families in China are aware of the critical lack of female children and it’s implication on marriage prospects in the future; many parents are beginning to work extra when their sons are young so that they will be able to pay for a bride for them.

The birth sex ratio in China, according to a 2012 news report, has decreased to 117 males born for every 100 females.

India

Further information: Female foeticide in India

India’s 2001 census revealed a national 0–6 age child sex ratio of 108, which increased to 109 according to 2011 census (927 girls per 1000 boys and 919 girls per 1000 boys respectively, compared to expected normal ratio of 943 girls per 1000 boys). The national average masks the variations in regional numbers according to 2011 census — Haryana’s ratio was 120, Punjab’s ratio was 118, Jammu & Kashmir was 116, and Gujarat’s ratio was 111. The 2011 Census found eastern states of India had birth sex ratios between 103 and 104, lower than normal. In contrast to decadal nationwide census data, small non-random sample surveys report higher child sex ratios in India.

The child sex ratio in India shows a regional pattern. India’s 2011 census found that all eastern and southern states of India had a child sex ratio between 103 to 107, typically considered as the “natural ratio.” The highest sex ratios were observed in India's northern and northwestern states - Haryana (120), Punjab (118) and Jammu & Kashmir (116). The western states of Maharashtra and Rajasthan 2011 census found a child sex ratio of 113, Gujarat at 112 and Uttar Pradesh at 111.

The Indian census data suggests there is a positive correlation between abnormal sex ratio and better socio-economic status and literacy. Urban India has higher child sex ratio than rural India according to 1991, 2001 and 2011 Census data, implying higher prevalence of sex selective abortion in urban India. Similarly, child sex ratio greater than 115 boys per 100 girls is found in regions where the predominant majority is Hindu, Muslim, Sikh or Christian; furthermore "normal" child sex ratio of 104 to 106 boys per 100 girls are also found in regions where the predominant majority is Hindu, Muslim, Sikh or Christian. These data contradict any hypotheses that may suggest that sex selection is an archaic practice which takes place among uneducated, poor sections or particular religion of the Indian society.

Rutherford and Roy, in their 2003 paper, suggest that techniques for determining sex prenatally that were pioneered in the 1970s, gained popularity in India. These techniques, claim Rutherford and Roy, became broadly available in 17 of 29 Indian states by the early 2000s. Such prenatal sex determination techniques, claim Sudha and Rajan in a 1999 report, where available, favored male births.

Arnold, Kishor, and Roy, in their 2002 paper, too hypothesize that modern fetal sex screening techniques have skewed child sex ratios in India. Ganatra et al., in their 2000 paper, use a small survey sample to estimate that 1⁄6 of reported abortions followed a sex determination test.

Mevlude Akbulut-Yuksel and Daniel Rosenblum, in their 2012 paper, find that despite numerous publications and studies, there is limited formal evidence on the effects of the continued spread of ultrasound technology on missing women in India. They conclude, contrary to common belief, that the recent rapid spread of ultrasound in India, from the 1990s through 2000s, did not cause a concomitant rise in sex-selection and prenatal female abortion.

The Indian government and various advocacy groups have continued the debate and discussion about ways to prevent sex selection. The immorality of prenatal sex selection has been questioned, with some arguments in favor of prenatal discrimination as more humane than postnatal discrimination by a family that does not want a female child. Others question whether the morality of sex selective abortion is any different over morality of abortion when there is no risk to the mother nor to the fetus, and abortion is used as a means to end an unwanted pregnancy?

India passed its first abortion-related law, the so-called Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act of 1971, making abortion legal in most states, but specified legally acceptable reasons for abortion such as medical risk to mother and rape. The law also established physicians who can legally provide the procedure and the facilities where abortions can be performed, but did not anticipate sex selective abortion based on technology advances.

With increasing availability of sex screening technologies in India through the 1980s in urban India, and claims of its misuse, the Government of India passed the Pre-natal Diagnostic Techniques Act (PNDT) in 1994. This law was further amended into the Pre-Conception and Pre-natal Diagnostic Techniques (Regulation and Prevention of Misuse) (PCPNDT) Act in 2004 to deter and punish prenatal sex screening and sex selective abortion. The impact of the law and its enforcement is unclear. United Nations Population Fund and India's National Human Rights Commission, in 2009, asked the Government of India to assess the impact of the law. The Public Health Foundation of India, an activist NGO in its 2010 report, claimed a lack of awareness about the Act in parts of India, inactive role of the Appropriate Authorities, ambiguity among some clinics that offer prenatal care services, and the role of a few medical practitioners in disregarding the law.

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare of India has targeted education and media advertisements to reach clinics and medical professionals to increase awareness. The Indian Medical Association has undertaken efforts to prevent prenatal sex selection by giving its members Beti Bachao (save the daughter) badges during its meetings and conferences.

MacPherson estimates that 100,000 abortions every year continue to be performed in India solely because the fetus is female.

Southeast Europe

According to Eurostat and birth record data over 2008–2011, the birth sex ratios of Albania and Montenegro are currently 112 and 110 respectively. In recent years, the birth registration data for Macedonia and Kosovo indicate birth sex ratios above 108; for example, in 2011 the birth sex ratio was 108 in Macedonia, while in 2010 the birth sex ratio for Kosovo was 112. Scholars claim this suggests that sex-selective abortions are becoming common in southeast Europe.

United States

Like in other countries, sex-selective abortion is difficult to track in the United States because of lack of data. However, based on the sex ratios in the United States, it is certainly rare for the population overall. Abrevaya (2009) found that among firstborn children in the U.S., the sex ratio is the normal 102-106 males per 100 females. However, he also found that among some Korean, Chinese, and Indian parents with one daughter, the sex ratio is 117 and when they have two daughters, the ratio is 151.

While the majority of parents in United States do not practice sex-selective abortion, there is certainly a trend toward male preference. According to a 2011 Gallup poll, if they were only allowed to have one child, 40% of respondents said they would prefer a boy, while only 28% preferred a girl. When told about prenatal sex selection techniques such as sperm sorting and in vitro fertilization embryo selection, 40% of Americans surveyed thought that picking embryos by sex was an acceptable manifestation of reproductive rights. These selecting techniques are available at about half of American fertility clinics, as of 2006.

However, it is notable that minority groups that immigrate into the United States bring their cultural views and mindsets into the country with them. A study carried out at a Massachusetts infertility clinic shows that the majority of couples using these techniques, such as Preimplantation genetic diagnosis came from a Chinese or Asian background. This is thought to branch from the social importance of giving birth to male children in China and other Asian countries.

Because of this movement toward sex preference and selection, many bans on sex-selective abortion have been proposed at the state and federal level. In 2010 and 2011, sex-selective abortions were banned in Oklahoma and Arizona, respectively. Legislators in Georgia, West Virginia, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, and New York have also tried to pass acts banning the procedure.

Other countries

A 2013 study by John Bongaarts based on surveys in 61 major countries calculates the sex ratios that would result if parents had the number of sons and daughters they want. In 35 countries, claims Bongaarts, the desired birth sex ratio in respective countries would be more than 110 boys for every 100 girls if parents in these countries actually get a gender what they hope for (higher than India’s, which The Economist claims is 108).

Other countries with large populations but high sex ratios include Pakistan and Vietnam. United Nations Population Fund, in its 2012 report, claims the birth sex ratio of Vietnam at 111 with its densely populated Red River Delta region at 116; for Pakistan, the UN estimates the birth sex ratio to be 110. The urban regions of Pakistan, particularly its densely populated region of Punjab, report a sex ratio above 112 (less than 900 females per 1000 males). Hudson and Den Boer estimate the resulting deficit to be about 6 million missing girls in Pakistan than what would normally be expected. Three different research studies, according to Klausen and Wink, note that Pakistan had the world's highest % of missing girls, relative to its total pre-adult female population. Singapore has reported a birth sex ratio of 108. Taiwan has reported a sex ratio at birth between 1.07 to 1.11 every year, across 4 million births, over the 20-year period from 1991 to 2011, with the highest birth sex ratios in the 2000s.

Abnormal sex ratios at birth, possibly explained by growing incidence of sex-selective abortion, have also been noted in some other countries outside South and East Asia. According to the 2011 CIA estimates, countries with more than 110 males per 100 females at birth also include Albania and former Soviet republics of Armenia and Azerbaijan.

- Immigrants

A study of the 2000 United States Census suggests possible male bias in families of Chinese, Korean and Indian immigrants, which was getting increasingly stronger in families where first one or two children were female. In those families where the first two children were girls, the birth sex ratio of the third child was 151.

Estimates of missing women

Estimates of implied missing girls, considering the "normal" birth sex ratio to be the 103–107 range, vary considerably between researchers and underlying assumptions for expected post-birth mortality rates for men and women. For example, a 2005 study estimated that over 90 million females were "missing" from the expected population in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, China, India, Pakistan, South Korea and Taiwan alone, and suggested that sex-selective abortion plays a role in this deficit. For early 1990s, Sen estimated 107 million missing women, Coale estimated 60 million as missing, while Klasen estimated 89 million missing women in China, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, West Asia and Egypt. Guilmoto, in his 2010 report, uses recent data (except for Pakistan), and estimates a much lower number of missing girls, but notes that the higher sex ratios in numerous countries have created a gender gap - shortage of girls - in the 0–19 age group.

| Country | Gender gap 0-19 age group (2010) |

% of minor females |

Region | Majority Religion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 265,000 | 3.0 | South Asia | Islam |

| Albania | 21,000 | 4.2 | Southeast Europe | Islam |

| Armenia | 35,000 | 8.4 | Caucasus | Christianity |

| Azerbaijan | 111,000 | 8.3 | Caucasus | Islam |

| Bangladesh | 416,000 | 1.4 | South Asia | Islam |

| China | 25,112,000 | 15.0 | East Asia | |

| Georgia | 24,000 | 4.6 | Caucasus | Christianity |

| India | 12,618,000 | 5.3 | South Asia | Hindu |

| Montenegro | 3,000 | 3.6 | Southeast Europe | Christianity |

| Nepal | 125,000 | 1.8 | South Asia | Hindu |

| Pakistan | 206,000 | 0.5 | South Asia | Islam |

| South Korea | 336,000 | 6.2 | East Asia | |

| Singapore | 21,000 | 3.5 | Southeast Asia | Buddhist |

| Viet Nam | 139,000 | 1.0 | Southeast Asia | Buddhist |

Reasons for sex-selective abortion

Various theories have been proposed as possible reasons for sex-selective abortion. Culture rather than economic conditions is favored by some researchers because such deviations in sex ratios do not exist in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean. Other hypotheses include disparate gender-biased access to resources, and attempts to control population growth such as using one child policy.

Some demographers question whether sex-selective abortion or infanticide claims are accurate, because underreporting of female births may also explain high sex ratios. Natural reasons may also explain some of the abnormal sex ratios. In contrast to these possible causes of abnormal sex ratio, Klasen and Wink suggest India and China’s high sex ratios are primarily the result of sex-selective abortion.

Cultural preference

The reason for intensifying sex-selection abortion in China and India can be seen through history and cultural background. Generally, before the information era, male babies were preferred because they provided manual labor and success the family lineage. Labor is still important in developing nations as China and India, but when it comes to family lineage, it is of great importance.

The selective abortion of female fetuses is most common in areas where cultural norms value male children over female children for a variety of social and economic reasons. A son is often preferred as an "asset" since he can earn and support the family; a daughter is a "liability" since she will be married off to another family, and so will not contribute financially to her parents. Sex selective female abortion is a continuation, in a different form, of a practice of female infanticide or withholding of postnatal health care for girls in certain households. Furthermore, in some cultures sons are expected to take care of their parents in their old age. These factors are complicated by the effect of diseases on child sex ratio, where communicable and noncommunicable diseases affect males and females differently.

In modern East Asia, a large part of the pattern of preferences leading to this practice can be condensed simply as a desire to have a male heir. Monica Das Gupta (2005) observes, from 1989 birth data for China, there was no evidence of selective abortion of female fetuses among firstborn children. However, there was a strong preference for a boy if the first born was a girl.

Disparate gendered access to resources

Although there is significant evidence of the prevalence of sex-selective abortions in many nations (especially India and China), there is also evidence to suggest that some of the variation in global sex ratios is due to disparate access to resources. As MacPherson (2007) notes, there can be significant differences in gender violence and access to food, healthcare, immunizations between male and female children. This leads to high infant and childhood mortality among girls, which causes changes in sex ratio.

Disparate, gendered access to resources appears to be strongly linked to socioeconomic status. Specifically, poorer families are sometimes forced to ration food, with daughters typically receiving less priority than sons (Klasen and Wink 2003). However, Klasen’s 2001 study revealed that this practice is less common in the poorest families, but rises dramatically in the slightly less poor families. Klasen and Wink’s 2003 study suggests that this is “related to greater female economic independence and fewer cultural strictures among the poorest sections of the population.” In other words, the poorest families are typically less bound by cultural expectations and norms, and women tend to have more freedom to become family breadwinners out of necessity.

Increased sex ratios can be caused by disparities in aspects of life other than vital resources. According to Sen (1990), differences in wages and job advancement also have a dramatic effect on sex ratios. This is why high sex ratios are sometimes seen in nations with little sex-selective abortion. Additionally, high female education rates are correlated with lower sex ratios (World Bank 2011).

Lopez and Ruzikah (1983) found that, when given the same resources, women tend to outlive men at all stages of life after infancy. However, globally, resources are not always allocated equitably. Thus, some scholars argue that disparities in access to resources such as healthcare, education, and nutrition play at least a small role in the high sex ratios seen in some parts of the world (Klasen and Wink 2003). For example, Alderman and Gerter (1997) found that unequal access to healthcare is a primary cause of female death in developing nations, especially in Southeast Asia. Moreover, in India, lack of equal access to healthcare has led to increased disease and higher rates of female mortality in every age group until the late thirties (Sen 1990). This is particularly noteworthy because, in regions of the world where women receive equal resources, women tend to outlive men (Sen 1990).

Economic disadvantage alone may not always lead to increased sex ratio, claimed Sen in 1990. For example, in sub-Saharan Africa, one of the most economically disadvantaged regions of the world, there is an excess of women. So, if economic disadvantage is uncorrelated with sex ratio in Africa, some other factor(s) may be at play. More detailed analysis of African demographics, in 2002, suggests that Africa too has wide variation in birth sex ratios (from 1.01 in Bantu populations of East Africa to 1.08 in Nigeria and Ethiopia). Thus economic disadvantage remains a possible unresolved hypothesis for Africa as well.

One-child policy

Following the 1949 creation of the People's Republic of China, the issue of population control came into the national spotlight. In the early years of the Republic, leaders believed that telling citizens to reduce their fertility was enough, repealing laws banning contraception and instead promoting its use. However, the contraceptives were not widely available, both because of lack of supply and because of cultural taboo against discussing sex. Efforts were slowed following the famine of 1959–1961 but were resumed shortly thereafter with virtually the same results. Then, in 1964, the Family Planning Office was established to enforce stricter guidelines regarding fertility and it was moderately successful.

In 1979, the government adopted the One-Child Policy, which limited many families to one child, unless specified by provincial regulations. It was instituted as an attempt to boost the Chinese economy. Under it, families who break rules regarding the number of children they are allowed are given various punishments (primarily monetary), dependent upon the province in which they live.

As stated above, the sex ratios of a province are largely determined by the type of restriction placed upon the family, pointing to the conclusion that much of the imbalance in sex ratio in China can be attributed to the policy. Research by Junhong (2001) found that many parents are willing to pay to ensure that their child is male (especially if their first child is female), but will not do the same to ensure their child is female. Likely, fear of the harsh monetary punishments of the One-Child Policy make ensuring a son’s birth a smart investment. Therefore, son’s cultural and economic importance to families and the large expenses associated with multiple children are primary factors leading to China’s disparate sex ratio.

In 2013, China announced plans to formally change the One-Child policy, making it less stringent. The National People’s Congress has changed the policy to allow couples to have two children, so long as one of the partners is an only child. This change was not sparked by sex ratios, but rather by an aging population that is causing the workforce to grow increasingly smaller. It is estimated that this new law will lead to two million more births per year and could cause a baby boom in China. Unfortunately, many of China’s social problems are based on overpopulation. So, it is unclear if this new law will actually lead to women being more valued in Chinese society as the number of citizens increases.

Trivers–Willard hypothesis

The Trivers–Willard hypothesis argues that available resources affect male reproductive success more than female and that consequently parents should prefer males when resources are plentiful and females when resources are scarce. This has been applied to resource differences between individuals in a society and also to resource differences between societies. Empirical evidence is mixed with higher support in better studies according to Cronk in a 2007 review. One example, in a 1997 study, of a group with a preference for females was Romani in Hungary, a low status group. They "had a female-biased sex ratio at birth, were more likely to abort a fetus after having had one or more daughters, nursed their daughters longer, and sent their daughters to school for longer."

Societal effects

Missing women

The idea of “missing women” was first suggested by Amartya Sen, one of the first scholars to study high sex ratios and their causes globally, in 1990. In order to illustrate the gravity of the situation, he calculated the number of women that were not alive because of sex-selective abortion or discriminatory practices. He found that there were 11 percent fewer women than there “should” have been, if China had the natural sex ratio. This figure, when combined with statistics from around the world, led to a finding of over 100 million missing women. In other words, by the early 1990s, the number of missing women was “larger than the combined casualties of all famines in the twentieth century” (Sen 1990).

This has led to particular concern due to a critical shortage of wives. In some rural areas, there is already a shortage of women, which is tied to migration into urban areas (Park and Cho 1995). In South Korea and Taiwan, high male sex ratios and declining birth rates over several decades have led to cross-cultural marriage between local men and foreign women from countries such as mainland China, Vietnam and the Philippines. However, sex-selective abortion is not the only cause of this phenomenon; it is also related to migration and declining fertility.

Trafficking and sex work

Some scholars argue that as the proportion of women to men decreases globally, there will be an increase in trafficking and sex work (both forced and self-elected), as many people will be willing to do more to obtain a sexual partner (Junhong 2001). Already, there are reports of women from Vietnam, Myanmar, and North Korea systematically trafficked to mainland China and Taiwan and sold into forced marriages. Moreover, Ullman and Fidell (1989) suggested that pornography and sex-related crimes of violence (i.e., rape and molestation) would also increase with an increasing sex ratio.

Widening of the gender social gap

As Park and Cho (1995) note, families in areas with high sex ratios that have mostly sons tend to be smaller than those with mostly daughters (because the families with mostly sons appear to have used sex-selective techniques to achieve their “ideal” composition). Particularly in poor areas, large families tend to have more problems with resource allocation, with daughters often receiving fewer resources than sons. Blake (1989) is credited for noting the relationship between family size and childhood “quality.” Therefore, if families with daughters continue to be predominantly large, it is likely that the social gap between genders will widen due to traditional cultural discrimination and lack of resource availability.

Guttentag and Secord (1983) hypothesized that when the proportion of males throughout the world is greater, there is likely to be more violence and war.

Potential positive effects

Some scholars believe that when sex ratios are high, women actually become valued more because of their relative shortage. Park and Cho (1995) suggest that as women become more scarce, they may have “increased value for conjugal and reproductive functions” (75). Eventually, this could lead to better social conditions, followed by the birth of more women and sex ratios moving back to natural levels. This claim is supported by the work of demographer Nathan Keifitz. Keifitz (1983) wrote that as women become fewer, their relative position in society will increase. However, to date, no data has supported this claim.

It has been suggested by Belanger (2002) that sex-selective abortion may have positive effects on the mother choosing to abort the female fetus. This is related to the historical duty of mothers to produce a son in order to carry on the family name. As previously mentioned, women gain status in society when they have a male child, but not when they have a female child. Oftentimes, bearing of a son leads to greater legitimacy and agency for the mother. In some regions of the world where son preference is especially strong, sonless women are treated as outcasts. In this way, sex-selective abortion is a way for women to select for male fetuses, helping secure greater family status.

Goodkind (1999) argues that sex-selective abortion should not be banned purely because of its discriminatory nature. Instead, he argues, we must consider the overall lifetime possibilities of discrimination. In fact, it is possible that sex-selective abortion takes away much of the discrimination women would face later in life. Since families have the option of selecting for the fetal sex they desire, if they choose not to abort a female fetus, she is more likely to be valued later in life. In this way, sex-selective abortion may be a more humane alternative to infanticide, abandonment, or neglect. Goodkind (1999) poses an essential philosophical question, “if a ban were enacted against prenatal sex testing (or the use of abortion for sex-selective purposes), how many excess postnatal deaths would a society be willing to tolerate in lieu of whatever sex-selective abortions were avoided?”

Sex-selective abortion in the context of abortion

MacPherson estimates that 100,000 sex-selective abortions every year continue to be performed in India. For a contrasting perspective, in the United States with a population 1⁄4th of India, over 1.2 million abortions every year were performed between 1990 and 2007. In England and Wales with a population 1⁄20th of India, over 189,000 abortions were performed in 2011, or a yearly rate of 17.5 abortions per 1,000 women aged 15–44. The average for the European Union was 30 abortions per year per 1,000 women.

Many scholars have noted the difficulty in reconciling the discriminatory nature of sex-selective abortion with the right of women to have control over their own bodies. This conflict manifests itself primarily when discussing laws about sex-selective abortion. Weiss (1995:205) writes: "The most obvious challenge sex-selective abortion represents for pro-choice feminists is the difficulty of reconciling a pro-choice position with moral objections one might have to sex selective abortion (especially since it has been used primarily on female fetuses), much less the advocacy of a law banning sex-selective abortion." As a result, arguments both for and against sex-selective abortion are typically highly reflective of one’s own personal beliefs about abortion in general. Warren (1985:104) argues that there is a difference between acting within one’s rights and acting upon the most morally sound choice, implying that sex-selective abortion might be within rights but not morally sound. Warren also notes that, if we are to ever reverse the trend of sex-selective abortion and high sex ratios, we must work to change the patriarchy-based society which breeds the strong son preference.

Laws and initiatives against sex-selective abortion

Laws

In 1994 over 180 states signed the Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development, agreeing to "eliminate all forms of discrimination against the girl child". In 2011 the resolution of PACE's Committee on Equal Opportunities for Women and Men condemned the practice of prenatal sex selection.

Media and policy initiatives

Many nations have attempted to address sex-selective abortion rates through a combination of media campaigns and policy initiatives.

- Canada

In Canada, a group of MPs led by Mark Warawa are working on having the Parliament pass a resolution condemning sex-selective pregnancy termination.

- USA

The United States Congress has debated legislation that would outlaw the practice. The legislation ultimately failed to pass in the House of Representatives.

On the state level, laws against sex-selective abortions have been passed in a number of US states; the law passed in Arizona in 2011 prohibits both sex-selective and race-selective abortion.

- United Kingdom

The law on sex-selective abortion is unresolved in the United Kingdom. In order for an abortion to be legal, doctors need to show that continuing the pregnancy could threaten the physical or mental health of the mother. In a recent case, two doctors were caught on camera offering a sex-selective abortion but the Director of Public Prosecution deemed it not in the public interest to proceed with the prosecution. Following this incidence, MPs voted 181 to 1 for a Bill put forward by Tessa Munt and 11 other MPs aiming to end confusion about the legality of this practice. Organisations such as BPAS and Abortion Rights have been lobbying for the decriminalisation of sex-selective abortions.

- China

China’s government has increasingly recognized its role in a reduction of the national sex ratio. As a result, since 2005, it has sponsored a “boys and girls are equal campaign.” For example, in 2000, the Chinese government began the “Care for Girls” Initiative. Furthermore, several levels of government have been modified to protect the “political, economic, cultural, and social” rights of women. Finally, the Chinese government has enacted policies and interventions to help reduce the sex ratio at birth. In 2005, sex-selective abortion was made illegal in China. This came in response to the ever-increasing sex ratio and a desire to try to detract from it and reach a more normal ratio. The sex ratio among firstborn children in urban areas from 2000 to 2005 didn’t rise at all, so there is hope that this movement is taking hold across the nation.

UNICEF and UNFPA have partnered with the Chinese government and grassroots-level women’s groups such as All China Women’s Federation to promote gender equality in policy and practice, as well engage various social campaigns to help lower birth sex ratio and to reduce excess female child mortality rates.

- India

In India, according to a 2007 study by MacPherson, Prenatal Diagnostic Techniques Act (PCPNDT Act) was highly publicized by NGOs and the government. Many of the ads used depicted abortion as violent, creating fear of abortion itself within the population. The ads focused on the religious and moral shame associated with abortion. MacPherson claims this media campaign was not effective because some perceived this as an attack on their character, leading to many becoming closed off, rather than opening a dialogue about the issue. This emphasis on morality, claims MacPherson, increased fear and shame associated with all abortions, leading to an increase in unsafe abortions in India.

The government of India, in a 2011 report, has begun better educating all stakeholders about its MTP and PCPNDT laws. In its communication campaigns, it is clearing up public misconceptions by emphasizing that sex determination is illegal, but abortion is legal for certain medical conditions in India. The government is also supporting implementation of programs and initiatives that seek to reduce gender discrimination, including media campaign to address the underlying social causes of sex selection.

Other recent policy initiatives adopted by numerous states of India, claims Guilmoto, attempt to address the assumed economic disadvantage of girls by offering support to girls and their parents. These policies provide conditional cash transfer and scholarships only available to girls, where payments to a girl and her parents are linked to each stage of her life, such as when she is born, completion of her childhood immunization, her joining school at grade 1, her completing school grades 6, 9 and 12, her marriage past age 21. Some states are offering higher pension benefits to parents who raise one or two girls. Different states of India have been experimenting with various innovations in their girl-driven welfare policies. For example, the state of Delhi adopted a pro-girl policy initiative (locally called Laadli scheme), which initial data suggests may be lowering the birth sex ratio in the state.

In popular culture

- The Manish Jha film, Matrubhoomi-A Nation Without Women (2003), depicts a future dystopia in a village in India, populated exclusively by males due to female infanticide, and which is reduced to barbarianism.

See also

References

- ^ Goodkind, Daniel (1999). "Should Prenatal Sex Selection be Restricted?: Ethical Questions and Their Implications for Research and Policy". Population Studies. 53 (1): 49–61. doi:10.1080/00324720308069. JSTOR 2584811.

- ^ A. Gettis, J. Getis, and J. D. Fellmann (2004). Introduction to Geography, Ninth Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 200. ISBN 0-07-252183-X

- ^ HIGH SEX RATIO AT BIRTH IN SOUTHEAST EUROPE Christophe Z Guilmoto, CEPED, Université Paris-Descartes, France (2012)

- ^ Kumm, J.; Laland, K. N.; Feldman, M. W. (December 1994). "Gene-culture coevolution and sex ratios: the effects of infanticide, sex-selective abortion, sex selection, and sex-biased parental investment on the evolution of sex ratios". Theoretical Population Biology. 43 (3, number 3): 249–278. doi:10.1006/tpbi.1994.1027. PMID 7846643.

- Gammage, Jeff (June 21, 2011). "Gender imbalance tilting the world toward men". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- ^ James W.H. (July 2008). "Hypothesis:Evidence that Mammalian Sex Ratios at birth are partially controlled by parental hormonal levels around the time of conception". Journal of Endocrinology. 198 (1): 3–15. doi:10.1677/JOE-07-0446. PMID 18577567.

- ^ Report of the International Workshop on Skewed Sex Ratios at Birth United Nations FPA (2012)

- ^ Kraemer, Sebastian. "The Fragile Male." British Medical Journal (2000): n. pag. British Medical Journal. Web. 20 Oct. 2013.

- ^ Mevlude Akbulut-Yuksel and Daniel Rosenblum (January 2012), The Indian Ultrasound Paradox, IZA DP No. 6273, Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit, Bonn, Germany

- Avraham Ebenstein, Hongbin Li, and Lingsheng Meng (June 2013), The Impact of Ultrasound Technology on the Status of Women in China Department of Economics, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel

- Douthat, Ross (June 26, 2011). "160 Million and Counting". The New York Times.

- ^ Christophe Z Guilmoto, Sex imbalances at birth Trends, consequences and policy implications United Nations Population Fund, Hanoi (October 2011)

- ^ Junhong, Chu. "Prenatal Sex Determination and Sex-Selective Abortion in Rural Central China." Population and Development Review 27.2 (2001): 259-81. JSTOR. Web. 2 Nov. 2013.

- Grech, V; Savona-Ventura, C; Vassallo-Agius, P (2002). "Unexplained differences in sex ratios at birth in Europe and North America". BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 324 (7344). BMJ, NCBI/National Institutes of Health: 1010–1. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7344.1010. PMC 102777. PMID 11976243.

- Therese Hesketh and Zhu Wei Xing, Abnormal sex ratios in human populations: Causes and consequences, PNAS, September 5, 2006, vol. 103, no. 36, pp 13271-13275

- ^ Klausen, Stephan and Claudia Wink. "Missing Women: Revisiting the Debate" Feminist Economics 9 (2003): 263-299.

- ^ Sen, Amartya (1990), More than 100 million women are missing, New York Review of Books, 20 December, pp. 61–66

- see:

- James WH (1987). "The human sex ratio. Part 1: A review of the literature". Human Biology. 59 (5): 721–752. PMID 3319883. Retrieved August 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - James WH (1987). "The human sex ratio. Part 2: A hypothesis and a program of research". Human Biology. 59 (6): 873–900. PMID 3327803. Retrieved August 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - MARIANNE E. BERNSTEIN (1958). "Studies in The Human Sex Ratio 5. A Genetic Explanation of the Wartime Secondary Sex Ratio" (PDF). American Journal of Human Genetics. 10 (1): 68–70. PMC 1931860. PMID 13520702.

- France MESLÉ, Jacques VALLIN, Irina BADURASHVILI (2007). A Sharp Increase in Sex Ratio at Birth in the Caucasus. Why? How? (PDF). Committee for International Cooperation in National Research in Demography. pp. 73–89. ISBN 2-910053-29-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- James WH (1987). "The human sex ratio. Part 1: A review of the literature". Human Biology. 59 (5): 721–752. PMID 3319883. Retrieved August 2011.

- JAN GRAFFELMAN and ROLF F. HOEKSTRA, A Statistical Analysis of the Effect of Warfare on the Human Secondary Sex Ratio, Human Biology, Vol. 72, No. 3 (June 2000), pp. 433-445

- ^ R. Jacobsen, H. Møller and A. Mouritsen, Natural variation in the human sex ratio, Hum. Reprod. (1999) 14 (12), pp 3120-3125

- ^ T Vartiainen, L Kartovaara, and J Tuomisto (1999). "Environmental chemicals and changes in sex ratio: analysis over 250 years in finland". Environmental Health Perspectives. 107 (10): 813–815. doi:10.1289/ehp.99107813. PMC 1566625. PMID 10504147.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Michel Garenne, Southern African Journal of Demography, Vol. 9, No. 1 (June 2004), pp. 91-96

- Michel Garenne, Southern African Journal of Demography, Vol. 9, No. 1 (June 2004), page 95

- RB Campbell, John Graunt, John Arbuthnott, and the human sex ratio, Hum Biol. 2001 Aug;73(4):605-610

- Ciocco, A. (1938), Variations in the ratio at birth in USA, Human Biology, 10:36–64

- Jing-Bao Nei (2011), Non-medical sex-selective abortion in China: ethical and public policy issues in the context of 40 million missing females, British Med Bull 98 (1): 7-20

- Jiang B, Li S. Nüxing Queshi yu Shehui Anquan (2009), The Female Deficit and the Security of Society, Beijing: Social Sciences Academic, pp 22-26

- Matthews TJ; et al. (June 2005). "Trend Analysis of the Sex Ratio at Birth in the United States". National Vital Statistics Reports. 53 (20).

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - "Sex ratio in Switzerland". Switzerland Federal Statistics Office.

- "UN Sex Ratio Statistics". United Nations Population Division.

- "Sex ratio at birth (per 100 female newborn)". United Nations Data Division.

- Demographic and Health Survey

- Garenne M (December 2002). "Sex ratios at birth in African populations: a review of survey data". Hum. Biol. 74 (6): 889–900. doi:10.1353/hub.2003.0003. PMID 12617497.

- "Trend Analysis of the Sex Ratio at Birth in the United States" (PDF). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics.

- ^ "Sex Ratio, The World Factbook, CIA, US Government (2013); Note: Sex ratio of 1.26 is same as 126 boys per 100 girls".

- Births and deliveries Switzerland (2013)

- Sex Ratios, Christophe Z Guilmoto, UNFPA (2011), Page 13

- Sex ratio at birth - National and Regional Census Data Pakistan Census (2013)

- see:

- Gender Imbalance: Pakistan's Missing Women Dawn, Pakistan (2013);

- Abandoned, Aborted, or Left for Dead: These Are the Vanishing Girls of Pakistan, HABIBA NOSHEEN & HILKE SCHELLMANN, June 19, 2012, The Atlantic

- The Consequences of the "Missing Girls" of China, Avraham Y. Ebenstein and Ethan Jennings Sharygin (2009), THE WORLD BANK ECONOMIC REVIEW, VOL. 23, NO. 3, page 401, Oxford University Press

- ^ Sex Imbalances at Birth: Current trends, consequences and policy implications United Nations FPA (August 2012)

- ^ Gendercide in the Caucasus The Economist (September 13, 2013)

- India Census 2011 Provisional Report Government of India (2013)

- Devaney SA, Palomaki GE, Scott JA, Bianchi DW (2011). "Noninvasive Fetal Sex Determination Using Cell-Free Fetal DNA". JAMA. 306 (6): 627–636. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.1114. PMID 21828326.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Roberts, Michelle (August 10, 2011). "Baby gender blood tests 'accurate'". BBC News Online.

- ^ Mazza V, Falcinelli C, Paganelli S; et al. (June 2001). "Sonographic early fetal gender assignment: a longitudinal study in pregnancies after in vitro fertilization". Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 17 (6): 513–6. doi:10.1046/j.1469-0705.2001.00421.x. PMID 11422974.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Alfirevic Z, von Dadelszen P (2003). "Instruments for chorionic villus sampling for prenatal diagnosis". In Alfirevic, Zarko. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD000114.doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000114

- Chu Junhong, Prenatal Sex Determination and Sex-Selective Abortion in Rural Central China, Population and Development Review, Vol. 27, No. 2 (Jun., 2001), page 260

- ^ France MESLÉ, Jacques VALLIN, Irina BADURASHVILI (2007). A Sharp Increase in Sex Ratio at Birth in the Caucasus. Why? How?. Committee for International Cooperation in National Research in Demography. pp. 73–89. ISBN 2-910053-29-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Michael, M; King, L; Guo, L; McKee, M; Richardson, E; Stuckler, D (2013), The mystery of missing female children in the Caucasus: an analysis of sex ratios by birth order, International perspectives on sexual and reproductive health, 39 (2), pp. 97-102, ISSN 1944-0391

- ^ John Bongaarts (2013), The Implementation of Preferences for Male Offspring, Population and Development Review, Volume 39, Issue 2, pages 185–208, June 2013

- China's sex ratio declines for two straight years Xinhua, China

- Kang C, Wang Y. Sex ratio at birth. In: Theses Collection of 2001 National Family Planning and Reproductive Health Survey. Beijing: China Population Publishing House, 2003:88-98.

- ^ Zeng Yi et al. 1993."Causes and implications of the recent increase in the reported sex ratio at birthin China," Population and DevelopmentReview19(2): 283-302.

- Tania Branigan, China's Great Gender Crisis The Guardian, UK, 2 November 2011

- ^ Zhu, W., L. Lu, and T Hesketh. "China’s Excess Males, Sex Selective Abortion, and One Child Policy: Analysis of Data from 2005 National Intercensus Survey." British Medical Journal (2009): n. pag. JSTOR. Web. 2 Nov. 2013.

- Ministry of Health and State Family Planning Commission.1986. "Notice on strictly forbidding prenatal sex determination," reprinted in Peng Peiyun(ed.), 1997, Family Planning Encyclopedia of China. Beijing: China Population Press, p. 939.

- Ministry of Health. 1989. "Urgent notice on strictly forbidding the use of medical technology to perform prenatal sex determination," reprinted in Peng Peiyun (ed.), 1997, Family Planning Encyclopedia of China. Beijing: China Population Press, pp. 959-960.

- ^ Hardee, Karen, Gu Baochang, and Xie Zhenming. 2000. "Holding up more than half the sky:Fertility control and women's empowerment in China,"paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America, 23–25 March, Los Angeles.

- Qiu Renzong. 1987. Life Ethics Shanghai:ShanghaiPeople'sPress

- Junhong, Chu. 2000. "Study on the quality of the family planning program in China,"paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America,23–25 March, Los Angeles.

- Winckler, Edwin A. "Chinese Reproductive Policy at the Turn of the Millennium: Dynamic Stability." Population and Development Review 28.3 (2002): 379-418.

- Dudley L. Poston Jr., Eugenia Conde, and Bethany DeSalvo, "China's Unbalanced Sex Ratio at Birth, Millions of Excess Bachelors and Societal Implications," Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies 6, no. 4 (2011): 314-320

- "China sees decrease in male to female birth ratio gap." China.org.cn, March 21, 2012. Retrieved on Nov.19 2013 from http://www.china.org.cn/video/2012-03/31/content_25036729.htm

- India at Glance - Population Census 2011 - Final Census of India, Government of India (2013)

- ^ Child Sex Ratio in India C Chandramouli, Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India (2011)

- Census of India 2011: Child sex ratio drops to lowest since Independence The Economic Times, India

- Trends in Sex Ratio at Birth and Estimates of Girls Missing at Birth in India UNFPA (July 2010)

- ^ Child Sex Ratio 2001 versus 2011 Census of India, Government of India (2013)

- ^ IMPLEMENTATION OF THE PCPNDT ACT IN INDIA - Perspectives and Challenges Public Health Foundation of India, Supported by United Nations FPA (2010)

- Rutherford, R., and T. K. Roy. "Factors Affecting Sex-selective Abortion in Indian and 17 Major States." International Institute for Population Sciences and Honolulu: East-West Center (2003)

- Sudha, S. and S. Irudaya Rajan. 1999. "Female demographic disadvantage in India 1981- 1991: Sex selective abortions and female infanticide," Development and Change 30: 585- 618.

- Arnold, Fred, Kishor, Sunita, & Roy, T. K. (2002). "Sex-Selective Abortions in India". Population and Development Review 28 (4): 759–785. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2002.00759.x

- Ganatra, Bela, R. 2000. "Abortion research in India: What we know, and what we need to know," in Radhika Ramasubban and Shireen J. Jejeebhoy (eds.), Women's Reproductive Health in India. New Delhi: Rawat Publications.

- Kumar, Dharma. 1983. "Male utopias or nightmares?" Economic and Political Weekly 13(3):61-64.

- Gangoli, Geetanjali (1998), "Reproduction, abortion and women's health," Social Scientist 26(11-12): 83-105.

- Goodkind, Daniel (1996), "On substituting sex preference strategies in East Asia: Does pre-natal sex selection reduce post natal discrimination?", Population and Development Review 22(1): 111-125.

- "Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act 1971 - Introduction." Health News RSS. Med India, n.d. Web. 20 Oct. 2013.

- ^ MacPherson, Yvonne (November 2007). "Images and Icons: Harnessing the Power of Media to Reduce Sex-Selective Abortion in India". Gender and Development. 15 (2): 413–23. doi:10.1080/13552070701630574.

- Sex Imbalances at Birth: Current trends, consequences and policy implications United Nations FPA (August 2012), see page 23

- Stump, Doris (2011), Prenatal Sex Selection, Committee on Equal Opportunities for Women and Men, Council of Europe

- Verropoulou and Tsimbos (2010), Journal of Biosocial Science, vol. 42, No. 3, pp. 425-430.

- Abrevaya, Jason. "Are There Missing Girls in the United States? Evidence from Birth Data." American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 1.2 (2009): 1-34.

- Newport, Frank. "Americans Prefer Boys to Girls, Just as They Did in 1941." Gallup, 23 June 2011. Web. 2 Nov. 2013.

- ^ Jesudason, Sujatha, and Anat Shenker-Osorio. "The Atlantic." The Atlantic. N.p., 31 May 2012. Web. 03 Nov. 2013.

- "Half Fertility Clinics Allow Parents to Pick Gender." Msnbc.com. Associated Press, 20 Sept. 2006. Web. 03 Nov. 2013.

- Savior Siblings: Is PGD Being Regulated?. (2009, June 29). Savior Siblings. Retrieved September 23, 2013, from http://ourethicaljourney09.blogspot.ca/2009/06/is-big-brother-watching-pgd-regulations.html

- Sex Imbalances at Birth: Current trends, consequences and policy implications UNFPA, ISBN 978-974680-3380, page 20

- N Purewal (2010), "Son Preference, Sex Selection, Gender and Culture in South Asia", Oxford International Publishers / Berg, ISBN 978-1-84520-468-6, page 38

- ^ VALERIE M. HUDSON and ANDREA M. DEN BOER Missing Women and Bare Branches: Gender Balance and Conflict ECSP Report, Issue 11

- Klausen, Stephan and Claudia Wink, "Missing Women: Revisiting the Debate" Feminist Economics 9 (2003), page 270

- IW Lee et al. (December 2012), Human sex ratio at amniocentesis and at birth in Taiwan, Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol., 51(4):572-575

- Roberts, Sam (June 15, 2009). "U.S. Births Hint at Bias for Boys in Some Asians". The New York Times. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- Johansson, Sten; Nygren, Olga (1991). "The missing girls of China: a new demographic account". Population and Development Review. 17 (1): 35–51. doi:10.2307/1972351. JSTOR 1972351.

- Merli, M. Giovanna; Raftery, Adrian E. (2000). "Are births underreported in rural China?". Demography. 37 (1): 109–126. doi:10.2307/2648100. JSTOR 2648100. PMID 10748993.

- ^ Das Gupta, Monica, "Explaining Asia's Missing Women": A New Look at the Data", 2005

- Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2007.01.004, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2007.01.004instead. - World Bank, Engendering Development, The World Bank, (2001)

- Garenne M, Sex ratios at birth in African populations: a review of survey data Human Biology, 2002 Dec, 74(6):889-900

- Henneberger, S. "China's One-Child Policy." : History. N.p., 2007. Web. 24 Nov. 2013.

- "History of the One-Child Policy." All Girls Allowed, 2013. Web. 25 Nov. 2013.

- “China’s one-child policy to change in the new year.” The Independent, December 29, 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2014. <http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/health-news/chinas-onechild-policy-to-change-in-the-new-year-9028601.html>.

- Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60546-9, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60546-9instead. - ^ Park,Chai Bin and Nam-Hoon Cho. 1995. "Consequences of son preference in a low- fertility society:Imbalance of the sex ratio at birth in Korea,"Population and Development Review21(1): 59-84.

- Onishi, Norimitsu (February 22, 2007). "Korean Men Use Brokers to Find Brides in Vietnam". The New York Times.

- Last, Jonathan V. (June 24, 2011). "The War Against Girls". The Wall Street Journal.

- Ullman, Jodie and Linda Fidell. 1989. "Gender selection and society," " in Joan Offerman- Zuckerberg (ed.), Gender in Transition: A New Frontier. New York: Plenum Medical Book Company, pp. 179-187.

- Blake, Judith. 1989. Family Size and Achievement. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Guttentag, M and P Secord. “Too Many Women? The Sex Ratio Question.” Sage Publications. 1983.

- Keifitz, Nathan. Foreword. In: Bennett NG, editor. Sex selection of children. New York: Academic Press; 1983. p. xi-xiii.

- Belanger, Daniele. “Sex-selective abortions: short-term and long-term perspectives” Reproductive Health Matters 10.19(2002): 194-197. JSTOR. Web. 30 March 2014

- Goodkind, Daniel (1999), "Should prenatal sex selection be restricted? Ethical questions and their implications for research and policy," Population Studies, 53(1): 49-61

- Abortions—Number and Rate by Race: 1990 to 2007 US Census Bureau, Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2012

- Abortion Statistics, England and Wales: 2011 Department of Health, UK Government (May 2012), page 3

- Facts and figures about abortion in the European Region World Health Organization (2012), Summary Note 4

- Weiss, Gail. “Sex-Selective Abortion: A Relational Approach.” Hypatia 10.1(1995):202-217. JSTOR. Web. 30 March 2014. <http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.rice.edu/stable/pdfplus/3810465.pdf?acceptTC=true&jpdConfirm=true>.

- Warren, Mary Ann. “Gendercide: The Implications of Sex-Selection.” Rowman and Allenheld. 1985.

- "Preventing gender-biased sex selection" (PDF). UNFPA. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- "Prenatal sex selection" (PDF). PACE. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- Jones, Natasha. "MP takes aim at sex selection". The Langley Times. Retrieved October 6, 2012.

- Mark Kennedy, MP continues push for sex-selection abortions vote after motion rejected, Postmedia News, 2013-03-26

- "House debates abortion ban for sex of fetus". CNN Online. May 31, 2012. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- Steinhauer, Jennifer (May 31, 2012). "House Rejects Bill to Ban Sex-Selective Abortions". New York Times. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- ^ Christie, Bob (May 29, 2013). "Arizona Race And Sex-Selective Abortion Ban Draws ACLU Lawsuit".

- "HB 2443: An Act amending Title 13, Chapter 36, Arizona Revised Statutes, by adding section 13-3603.02; ..." (PDF).

- "Arizona Revised Statutes, 13-3603.02. Abortion; sex and race selection; injunctive and civil relief; failure to report; definition".

- http://www.telegraph.co.uk/health/healthnews/11208011/MPs-vote-to-make-sex-selection-abortion-illegal.html

- "Burnham's MP Tessa Munt backs sex-selection abortion bill". thewestcountry.co.uk. December 5, 2014. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- "UK: Sex-Selective Abortions Voted Illegal By Parliament Members". gender-selection.com.au. December 1, 2014. ISSN 2204-3888. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- "Statement on sex-selective abortion". Abortion Rights. September 18, 2014. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- "Statement on sex-selective abortion". Spiked.com. May 23, 2014. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

- ^ Song, Jian. 2009. "Rising sex ratio at birth in China: responses and effects of social policies." <http://iussp2009.princeton.edu/papers/91145>

- "'Care For Girls' Gaining Momentum." 'Care For Girls' Gaining Momentum. China Daily, 07 Aug. 2004. Web. 03 Nov. 2013.

- ”China Makes Sex-Selective Abortions a Crime.” Reproductive Health Matters 13.25 (2005): 203. JSTOR. Web. 30 March 2014. <http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.rice.edu/stable/pdfplus/3776292.pdf?acceptTC=true&jpdConfirm=true>.

- Gender Equality UNICEF (2012)

- UNFPA First Agency to Campaign against Sex Selection in China United Nations Population Fund (2012)

- MTP and PCPNDT Initiatives Report Government of India (2011)

- Delhi Laadli scheme 2008 Government of Delhi, India

- "Matrubhoomi (2003)". New York Times.

External links

- A conference held in Singapore in December 2005 on female deficit in Asia

- Sex Selection at Birth; Statistics Singapore Newsletter, Vol 17 No.3 January 1995

- MSNBC - No Girls Please - In parts of Asia, sexism is ingrained and gender selection often means murder

- Surplus Males and US/China Relations

- A Dangerous Surplus of Sons? - An analysis of various studies of the lopsided sex ratios in Asian countries

- Case study: Female Infanticide in India and China

- Working paper by Emily Oster linking sex ratio imbalances to hepatitis B infection

- S2 China Report - China: The Effects of the One Child Policy

- Notification on Addressing in a Comprehensive Way the Issue of Rising Sex Ratio at Birth a UNESCAP document

- A collection of essays on sex selection in various Asian countries by Attané and Guilmoto

- Five case studies and a video on sex selection in Asia by UNFPA

- NPR, All Things Considered, India Confronts Gender-Selective Abortion, March 21, 2006

- Book Review: Unnatural Selection - The War Against Girls / WSJ.com

| Social issues in India | |

|---|---|

| Economy | |

| Education | |

| Environment | |

| Family | |

| Children | |

| Women | |

| Caste system | |

| Communalism | |

| Crime | |

| Health | |

| Media | |

| Other issues | |