| Revision as of 23:12, 14 April 2015 view sourceBfpage (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers19,587 edits added Category:Infectious causes of cancer using HotCat← Previous edit | Revision as of 01:20, 15 April 2015 view source MrX (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers97,648 edits Reverted to revision 652093231 by Stamptrader: Inappropriate cat. See WP:NPOV, WP:CAT and the the actual category definition for Category:Infectious causes of cancer. (TW)Next edit → | ||

| Line 226: | Line 226: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

Revision as of 01:20, 15 April 2015

This article is about the human sexual act. For anal sex among non-human animals, see Animal sexual behaviour.

Anal sex or anal intercourse is generally the insertion and thrusting of the erect penis into a person's anus, or anus and rectum, for sexual pleasure. Other forms of anal sex include fingering, the use of sex toys for anal penetration, oral sex performed on the anus (anilingus), and pegging. Though the term anal sex most commonly means penile-anal penetration, sources sometimes use the term anal intercourse to refer exclusively to penile-anal penetration, and anal sex to refer to any form of anal sexual activity, especially between pairings as opposed to anal masturbation.

While anal sex is commonly associated with male homosexuality, research shows that not all gay males engage in anal sex and that it is not uncommon in heterosexual relationships. Types of anal sex can also be a part of lesbian sexual practices. People may experience pleasure from anal sex by stimulation of the anal nerve endings, and orgasm may be achieved through anal penetration – by indirect stimulation of the prostate in men, indirect stimulation of the clitoris or an area of the vagina associated with the G-spot in women, and other sensory nerves (especially the pudendal nerve). However, people may also find anal sex painful, sometimes extremely so, which may be primarily due to psychological factors in some cases.

As with most forms of sexual activity, anal sex participants risk contracting sexually transmitted infections (STIs/STDs). Anal sex is considered a high-risk sexual practice because of the vulnerability of the anus and rectum. The anal and rectal tissues are delicate and do not provide natural lubrication, so they can easily tear and permit disease transmission, especially if lubricant is not used. Anal sex without protection of a condom is considered the riskiest form of sexual activity, and therefore health authorities such as the World Health Organization (WHO) recommend safe sex practices for anal sex.

Often, strong views are expressed with regard to anal sex; it is controversial in various cultures, especially concerning religion, commonly due to prohibitions against anal sex among gay men or teachings about the procreative purpose of sexual activity. It may be regarded as taboo or unnatural, and is a criminal offense in some countries, punishable by corporal or capital punishment; by contrast, people also regard anal sex as a natural and valid form of sexual activity that may be as fulfilling as other desired sexual expressions. They may regard it as an enhancing element of their sex lives or as their primary form of sexual activity.

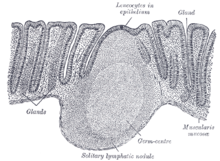

Anatomy and stimulation

See also: Prostate massageThe abundance of nerve endings in the anal region and rectum can make anal sex pleasurable for men or women. The internal and external sphincter muscles control the opening and closing of the anus; these muscles, which are sensitive membranes made up of many nerve endings, facilitate pleasure or pain during anal sex. "The inner third of the anal canal is less sensitive to touch than the outer two-thirds, but is more sensitive to pressure" and "he rectum is a curved tube about eight or nine inches long and has the capacity, like the anus, to expand".

Research indicates that anal sex occurs significantly less frequently than other sexual behaviors, but its association with dominance and submission, as well as taboo, makes it an appealing stimulus to people of all sexual orientations. In addition to sexual penetration by the penis, people may use sex toys such as butt plugs or anal beads, engage in fingering, anilingus, pegging, anal masturbation or fisting for anal sexual activity, and different sex positions may also be included. Fisting is the least practiced of the activities, with "ew people" being "capable of relaxing enough to accommodate something as big as a fist in their anus".

In a male receptive partner, being anally penetrated can produce a pleasurable sensation due to the inserted penis rubbing or brushing against the prostate (also known as the "male G-spot", "P-spot" or "A-spot") through the anal wall. This can result in pleasurable sensations and can lead to an orgasm in some cases. Prostate stimulation can produce a "deeper" orgasm, sometimes described by men as more widespread and intense, longer-lasting, and allowing for greater feelings of ecstasy than orgasm elicited by penile stimulation only. The prostate is located next to the rectum and is the larger, more developed male homologue (variation) to the female Skene's glands (which are believed to be connected to the female G-spot). However, though the experiences are different, male orgasms by penile stimulation are also centered in the prostate gland. It is also common, and may be typical, for men not to reach orgasm as receptive partners solely from anal sex.

General statistics indicate that 70–80% of women require direct clitoral stimulation to achieve orgasm. The clitoris is composed of more than the externally visible glans (head). With its glans or body as a whole estimated to have around 8,000 sensory nerve endings, the clitoris surrounds the vagina and urethra, and may have a similar connection with the anus. The vagina is flanked on each side by the clitoral crura, the internal "legs" of the clitoris, which are highly sensitive and become engorged with blood when sexually aroused. In addition to nerve endings present within the anus and rectum, women may find anal stimulation pleasurable due to indirect stimulation of these "legs". Indirect stimulation of the clitoris through anal penetration may also be caused by the shared sensory nerves; especially the pudendal nerve, which gives off the inferior anal nerves and divides into two terminal branches: the perineal nerve and the dorsal nerve of the clitoris.

The Gräfenberg spot, or G-spot, is a debated area of female anatomy, particularly among doctors and researchers, but it is typically described as being located behind the female pubic bone surrounding the urethra and accessible through the anterior wall of the vagina; it is considered to have tissue and nerves that are related to the clitoris. Besides the shared anatomy of the aforementioned sensory nerves, orgasm by stimulation of the clitoris or G-spot through anal penetration is made possible because of the close proximity between the vaginal cavity and the rectal cavity, allowing for general indirect stimulation. Achieving orgasm solely by anal stimulation is rare among women. Direct stimulation of the clitoris, G-spot, or both, during anal sex can help some women enjoy the activity and reach orgasm from it.

Stimulation from anal sex can additionally be affected by popular perception or portrayals of the activity, such as erotica or pornography. In pornography, anal sex is commonly portrayed as desirable, routine, without use of a personal lubricant or a condom, and painless; this can result in couples performing anal sex without care, and men and women believing that it is unusual for women, as receptive partners, to find no pleasure from the activity and instead discomfort or pain from it. By contrast, each person's sphincter muscles react to penetration differently, the anal sphincters have tissues that are more prone to tearing, and the anus and rectum, unlike the vagina, do not provide natural lubrication for sexual penetration. Researchers say adequate application of a personal lubricant, relaxation, and communication between sexual partners are crucial to avoid pain or damage to the anus or rectum. Ensuring that the anal area is clean and the bowel is empty, for both aesthetics and practicality, may also be desired.

Male to female

Behaviors and views

The anal sphincters are usually tighter than the pelvic muscles of the vagina, which can enhance the sexual pleasure for the inserting male during male-to-female anal intercourse because of the pressure applied to the penis. Men may also enjoy the penetrative role during anal sex because of its association with dominance, because it is made more alluring by a female or general society insisting that it is forbidden, or because it presents an additional option for penetration.

While some women find being a receptive partner during anal intercourse painful or uncomfortable, or only engage in the act to please a male sexual partner, other women find the activity pleasurable or prefer it to vaginal intercourse. The vaginal walls contain significantly fewer nerve endings than the clitoris and anus, and therefore intense sexual pleasure, including orgasm, from vaginal sexual stimulation is less likely to occur than from direct clitoral stimulation in the majority of women. However, anal sexual stimulation is not necessarily more likely to result in orgasm than vaginal sexual stimulation; the types of nerves and how they interact with each other are factors, as "total separation between the vagina and clitoris is mostly artificial, and often based on a misunderstanding of what, where, and how big the clitoris really is".

In a 2010 clinical review article of heterosexual anal sex, the term anal intercourse is used to refer specifically to penile-anal penetration, and anal sex is used to refer to any form of anal sexual activity. The review suggests that anal sex is exotic among the sexual practices of some heterosexuals and that "for a certain number of heterosexuals, anal intercourse is pleasurable, exciting, and perhaps considered more intimate than vaginal sex".

Anal intercourse is sometimes used as a substitute for vaginal intercourse during menstruation. The likelihood of pregnancy occurring during anal sex is greatly reduced, as anal sex alone cannot lead to pregnancy unless sperm is somehow transported to the vaginal opening. Because of this, some couples practice anal intercourse as a form of contraception, often in the absence of a condom.

Male-to-female anal sex is commonly viewed as a way of preserving female virginity because it is non-procreative and does not tear the hymen; a person, especially a female, who engages in anal sex or other sexual activity with no history of having engaged in vaginal intercourse is often regarded among heterosexuals and researchers as not having yet experienced virginity loss. This is sometimes termed technical virginity. Heterosexuals may view anal sex as "fooling around" or as foreplay, a view that "dates to the late 1600s, with explicit 'rules' appearing around the turn of the twentieth century, as in marriage manuals defining petting as 'literally every caress known to married couples but does not include complete sexual intercourse'".

Prevalence

In 1992, a study conducted by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that 26% of men 18 to 59 and 20% of women 18 to 59 had engaged in heterosexual anal sex; a similar 2005 survey (also conducted by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) found a rising incidence of anal sex relations in the American heterosexual population. The survey showed that 40% of men and 35% of women between 25 and 44 had engaged in heterosexual anal sex. In terms of overall numbers of survey respondents, seven times as many women as gay men said that they engaged in anal intercourse, with this figure reflecting the larger heterosexual population size.

In a 2007 report regarding the prevalence and correlates of heterosexual anal and oral sex among adolescents and adults in the United States, a National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) found that 34% men and 30% women reported ever participating in heterosexual anal sex. The percentage of participants reporting heterosexual anal sex was significantly higher among 20- to 24-year-olds and peaked among 30- to 34-year-olds. A 2008 survey focused on a younger demographic of teenagers and young adults, aged 15–21. It found that 16% of 1350 surveyed had had this type of sex in the previous 3 months, with condoms being used 29% of the time. However, given the subject matter, the survey hypothesized the prevalence was probably underestimated.

In Kimberly R. McBride's 2010 clinical review on heterosexual anal intercourse and other forms of anal sexual activity, it is suggested that changing norms may affect the frequency of heterosexual anal sex. McBride and her colleagues investigated the prevalence of non-intercourse anal sex behaviors among a sample of men (n=1,299) and women (n=1,919) compared to anal intercourse experience and found that 51% of men and 43% of women had participated in at least one act of oral–anal sex, manual–anal sex, or anal sex toy use. The report states the majority of men (n=631) and women (n=856) who reported heterosexual anal intercourse in the past 12 months were in exclusive, monogamous relationships: 69% and 73%, respectively. The review added that "most research on anal intercourse addresses men who have sex with men (MSM), with relatively little attention given to anal intercourse and other anal sexual behaviors between heterosexual partners" and "esearch is quite rare that specifically differentiates the anus as a sexual organ or addresses anal sexual function or dysfunction as legitimate topics. As a result, we do not know the extent to which anal intercourse differs qualitatively from coitus."

According to a 2010 study from the National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior (NSSHB) that was authored by Debby Herbenick and other researchers, although anal intercourse is reported by fewer women than other partnered sex behaviors, partnered women in the age groups between 18–49 are significantly more likely to report having anal sex in the past 90 days. As of 2011, this survey provides the most up to date data about anal sex at the population level.

Figures for prevalence can vary among different demographics, regions and nationalities. A 1999 South Korean survey of 586 women documented that 3.5% of the respondents reported having had anal sex. By contrast, a 2001 French survey of five hundred female respondents concluded that a total of 29% had engaged in this practice, with one third of these confirming to have enjoyed the experience.

Figures for the prevalence of sexual behavior can also fluctuate over time. Edward O. Laumann's 1992 survey, reported in The Social Organization of Sexuality: Sexual Practices in the United States, found that about 20% of heterosexuals had engaged in male-to-female anal sex. Sex researcher Alfred Kinsey, working in the 1940s, had found that number to be closer to 40% at the time. A researcher from the University of British Columbia in 2005 put the number of heterosexuals who have engaged in this practice at between 30% and 50%. According to Columbia University's health website Go Ask Alice!: "Studies indicate that about 25 percent of heterosexual couples have had anal sex at least once, and 10 percent regularly have anal penetration." The increase of anal sexual activity among heterosexuals has also been linked to the increase in anal pornography, especially if a person views it more regularly than a person who does not.

Male to male

Behaviors and views

Historically, anal sex has been commonly associated with male homosexuality. However, many gay men and men who have sex with men in general (those who identify as gay, bisexual, heterosexual or have not identified their sexual identity) do not engage in anal sex. Among men who have anal sex with other men, the insertive partner may be referred to as the top and the one being penetrated may be referred to as the bottom. Those who enjoy either role may be referred to as versatile.

Gay men who prefer anal sex may view it as their version of intercourse and a natural expression of intimacy capable of providing great pleasure. The notion that it might resonate with gay men with the same emotional significance that vaginal sex resonates with heterosexuals has also been considered. Some men who have sex with men, however, believe that being a receptive partner during anal sex questions their masculinity.

Men who have sex with men may also prefer to engage in frot or other forms of mutual masturbation because they find it more pleasurable or more affectionate, to preserve technical virginity, or as safe sex alternatives to anal sex, while other frot advocates denounce anal sex as degrading to the receptive partner and unnecessarily risky.

Prevalence

Reports with regard to the prevalence of anal sex among gay men in the West have varied over time. Magnus Hirschfeld, in his 1914 work, The Homosexuality of Men and Women, reported the rate of anal sex among gay men surveyed to be 8%, the least favored of all the practices documented. By the 1950s in the United Kingdom, it was thought that about 15% of gay males had anal sex.

Similar to the Hirschfeld study, scholars state that oral sex and mutual masturbation are more common than anal stimulation among gay men in long-term relationships. They say that anal intercourse is generally more popular among gay male couples than among heterosexual couples, but that "it ranks behind oral sex and mutual masturbation" among both sexual orientations in prevalence. Wellings et al. reported that "he equation of 'homosexual' with 'anal' sex among men is common among lay and health professionals alike" and that "et an Internet survey of 18,000 MSM across Europe (EMIS, 2011) showed that oral sex was most commonly practised, followed by mutual masturbation, with anal intercourse in third place". A 2011 survey by The Journal of Sexual Medicine found similar results for U.S. gay and bisexual men.

Various older studies on male-to-male anal sex differ significantly. The 1994 Laumann study suggests that 80% of gay men practice anal sex and 20% never engage in it at all. A survey in The Advocate in 1994 indicated that 46% of gay men preferred to penetrate their partners, while 43% preferred to be the receptive partner. A survey conducted from 1994 to 1997 in San Francisco by the Stop AIDS Project indicated that over the course of the study, among men who have sex with men instead of solely gay men, the proportion engaging in anal sex increased from 57.6% to 61.2%. The National Institutes of Health (NIH), with their report published in the BMJ in 1999, stated that two thirds of gay men have anal sex. Other sources suggest that roughly three-fourths of gay men have had anal sex at one time or another in their lives, with an equal percentage participating as tops and bottoms. WebMD reports that "n estimated 90% of men who have sex with men" practice receptive anal intercourse.

Female to male

Women may sexually stimulate a man's anus by fingering the exterior or interior areas of the anus; they may also stimulate the perineum (which, for males, is between the base of the scrotum and the anus), massage the prostate or engage in anilingus. Sex toys, such as a dildo, may also be used. The practice of a woman penetrating a man's anus with a strap-on dildo for sexual activity is called pegging.

Commonly, heterosexual men reject the idea of being receptive partners during anal sex because they believe it is a feminine act, can make them vulnerable, or contradicts their sexual orientation (for example, that it is indicative that they are gay). National Institutes of Health (NIH) information published in the BMJ in 1999, however, states:

There are little published data on how many heterosexual men would like their anus to be sexually stimulated in a heterosexual relationship. Anecdotally, it is a substantial number. What data we do have almost all relate to penetrative sexual acts, and the superficial contact of the anal ring with fingers or the tongue is even less well documented but may be assumed to be a common sexual activity for men of all sexual orientations.

Reece et al. reported in 2010 that receptive anal intercourse is infrequent among men overall, stating that "an estimated 7% of men 14 to 94 years old reported being a receptive partner during anal intercourse".

Female to female

With regard to lesbian sexual practices, anal sex includes fingering, use of a dildo or other sex toys, or anilingus. Some lesbians do not like anal sex, and anilingus is less often practiced among female same-sex couples.

There is less research on anal sexual activity among women who have sex with women compared to couples of other sexual orientations. In 1987, a non-scientific study (Munson) was conducted of more than 100 members of a lesbian social organization in Colorado. When asked what techniques they used in their last ten sexual encounters, lesbians in their 30s were twice as likely as other age groups to engage in anal stimulation (with a finger or dildo). While author Tom Boellstorff, when particularly examining anal sex among gay and lesbian individuals in Indonesia, stated that he had not heard of oral-anal contact or anal penetration as recognized forms of lesbian sexuality but assume they take place, author Felice Newman, in The Whole Lesbian Sex Book, cites anal sex as a part of lesbian sexual practices.

Health risks

General risks

Anal sex can expose its participants to two principal dangers: infections due to the high number of infectious microorganisms not found elsewhere on the body, and physical damage to the anus and rectum due to their fragility. Increased experimentation with anal sex by people without sound knowledge about risks and what safety measures do and do not work may be linked to an increase in sexually transmitted infections (STIs/STDs); for example, teenagers may consider vaginal intercourse riskier than anal intercourse and believe that a STI can only result from the former activity.

Unprotected penile-anal penetration, colloquially known as barebacking, carries a higher risk of passing on STIs because the anal sphincter is a delicate, easily torn tissue that can provide an entry for pathogens. The high concentration of white blood cells around the rectum, together with the risk of tearing and the colon's function to absorb fluid, are what place those who engage in anal sex at high risk of STIs. Use of condoms, ample lubrication to reduce the risk of tearing, and safer sex practices in general, reduce the risk of STI transmission. However, a condom can (and is more likely to than other sex acts because of the tightness of the anal sphincters) break or otherwise come off during anal sex.

Unprotected receptive anal sex is the sex act most likely to result in HIV transmission. Other infections that can be transmitted by unprotected anal sex are human papillomavirus (HPV) (which can increase risk of anal cancer); typhoid fever; amoebiasis; chlamydia; cryptosporidiosis; E. coli infections; giardiasis; gonorrhea; hepatitis A; hepatitis B; hepatitis C; herpes simplex; Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (HHV-8); lymphogranuloma venereum; Mycoplasma hominis; Mycoplasma genitalium; pubic lice; salmonellosis; shigella; syphilis; tuberculosis; and Ureaplasma urealyticum.

There are a variety of factors that make male-to-female anal intercourse riskier for a female than for a male. For example, besides the risk of HIV transmission being higher for anal intercourse than for vaginal intercourse, the risk of injury to the woman during anal intercourse is significantly higher than the risk of injury to her during vaginal intercourse because of the durability of the vaginal tissues compared to the anal tissues. Additionally, if a man moves from anal intercourse immediately to vaginal intercourse without a condom or without changing it, infections (including urinary tract infections) can arise in the vagina due to bacteria present within the anus; these infections can also result from switching between vaginal sex and anal sex by the use of fingers or sex toys.

Though anal sex alone does not lead to pregnancy, pregnancy can still occur with anal sex or other forms of sexual activity if the penis is near the vagina (such as during intercrural sex or other genital-genital rubbing) and its sperm is deposited near the vagina's entrance and travels along the vagina's lubricating fluids; the risk of pregnancy can also occur without the penis being near the vagina because sperm may be transported to the vaginal opening by the vagina coming in contact with fingers or other non-genital body parts that have come in contact with semen.

Pain during receptive anal sex among gay men (or men who have sex with men) is formally known as anodyspareunia. One study found that about 12% of gay men find it too painful to pursue receptive anal sex, and concluded that the perception of anal sex as painful is as likely to be psychologically or emotionally based as it is to be physically based. Another study that examined pain during insertive and receptive anal sex in gay men found that 3% of tops (insertive partners) and 16% of bottoms (receptive partners) reported significant pain. Factors predictive of pain during anal sex include inadequate lubrication, feeling tense or anxious, lack of stimulation, as well as lack of social ease with being gay and being closeted. Research has found that psychological factors can in fact be the primary contributors to the experience of pain during anal intercourse and that adequate communication between sexual partners can prevent it, countering the notion that pain is always inevitable during anal sex.

Physical damage and cancer

It is uncommon for serious physical injury to occur as a result of anal sex, but anal sex can exacerbate hemorrhoids and therefore result in bleeding; if bleeding occurs, it may also be a result of a tear in the anal or rectal tissues or perforation (a hole) in the colon, the latter of which being a serious medical issue that should be remedied by immediate medical attention. Because of the rectum's lack of elasticity, the anal mucous membrane being thin, and small blood vessels being present directly beneath the mucous membrane, tiny tears and bleeding in the rectum usually result from penetrative anal sex, though the bleeding is usually minor and therefore usually not visible. By contrast to other anal sexual behaviors, anal fisting poses a more serious danger of damage due to the deliberate stretching of the anal and rectal tissues; anal fisting injuries include anal sphincter lacerations and rectal and sigmoid colon (rectosigmoid) perforation, which might result in death.

Repetitive penetrative anal sex may result in the anal sphincters becoming weakened, which may affect the ability to hold in feces (a condition known as fecal incontinence); Kegel exercises have been used to strengthen the anal sphincters and overall pelvic floor, and may help prevent or remedy fecal incontinence. A 1993 study indicated that fourteen out of a sample of forty men receiving anal intercourse experienced episodes of frequent fecal incontinence. However, a 1997 study found no difference in levels of fecal incontinence between gay men who engaged in anal sex and heterosexual men who did not, and criticized the earlier study for its inclusion of flatulence in its definition of fecal incontinence.

Most cases of anal cancer are related to infection with the human papilloma virus (HPV). Anal sex alone does not cause anal cancer; the risk of anal cancer through anal sex is attributed to HPV infection, which is often contracted through unprotected anal sex. Anal cancer is relatively rare, and significantly less common than cancer of the colon or rectum (colorectal cancer); the American Cancer Society states that it affects approximately 7,060 people (4,430 in women and 2,630 in men) and results in approximately 880 deaths (550 in women and 330 in men) in the United States, and that, though anal cancer has been on the rise for many years, it is mainly diagnosed in adults, "with an average age being in the early 60s" and it "affects women somewhat more often than men." Though anal cancer is serious, treatment for it is "often very effective" and most anal cancer patients can be cured of the disease; the American Cancer Society adds that "receptive anal intercourse also increases the risk of anal cancer in both men and women, particularly in those younger than the age of 30. Because of this, men who have sex with men have a high risk of this cancer."

Other cultural views

General

Different cultures have had different views on anal sex throughout human history, with some cultures more positive about the activity than others. Historically, it has been restricted or condemned, especially with regard to religious beliefs, and has also commonly been used as a form of domination, usually with the active partner (the one who is penetrating) representing masculinity and the passive partner (the one who is being penetrated) representing femininity. A number of cultures have especially recorded the practice of anal sex between men, and anal sex between men has been especially stigmatized or punished. In some societies, if discovered to have engaged in the practice, the individuals involved were put to death, such as by decapitation, burning, or mutilation.

Though anal sex has been more accepted in modern times, and is often considered a natural and pleasurable form of sexual expression, with some people, men in particular, only interested in anal sex for sexual satisfaction, engaging in the act is still punished in some societies. For example, regarding LGBT rights in Iran, Iran's Penal Code states in Article 109 that "both men involved in same-sex penetrative (anal) or non-penetrative sex will be punished" and "Article 110 states that those convicted of engaging in anal sex will be executed and that the manner of execution is at the discretion of the judge".

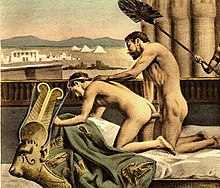

Ancient and non-Western cultures

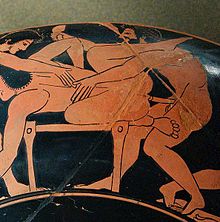

See also: Sexuality in ancient Rome § Anal sexThe term Greek love has long been used to refer to anal intercourse, and in modern times, "doing it the Greek way" is sometimes used as slang for anal sex. Ancient Greeks accepted romantic or sexual relationships between males as a balanced sex life (having males and women as lovers), and they considered this "normal (as long as one partner was an adult and the other was aged between twelve and fifteen)".

Homosexual anal sex was not a universally accepted practice in Ancient Greece; it was the target of jokes in comedies. Aristophanes, for instance, mockingly alludes to the practice, claiming, "Most citizens are europroktoi (wide-arsed) now." The terms kinaidos, europroktoi, and katapygon were used by Greek residents to categorize men who practiced passive anal intercourse. While pedagogic pederasty was an essential element in the education of male youths, these relationships, at least in Athens and Sparta, were expected to steer clear of penetrative sex of any kind. There are very few works of pottery or other art that display anal sex between men and boys, let alone between adult men. Greek artwork of sexual interaction between men and boys usually depicted fondling or intercrural sex, which was not condemned for violating or feminizing boys. Intercrural sex was not considered penetrative and two males engaging in it was considered a "clean" act. Other sources explicitly state that anal sex between men and boys was criticized as shameful and seen as a form of hubris.

In later Roman-era Greek poetry, anal sex became a common literary convention, represented as taking place with "eligible" youths: those who had attained the proper age but had not yet become adults. Seducing those not of proper age (for example, non-adolescent children) into the practice was considered very shameful for the adult, and having such relations with a male who was no longer adolescent was considered more shameful for the young male than for the one mounting him; Greek courtesans, or hetaerae, are said to have frequently practiced heterosexual anal intercourse as a means of preventing pregnancy.

A male citizen taking the passive (or receptive) role in anal intercourse was condemned in Rome as an act of impudicitia (immodesty or unchastity); free men, however, frequently took the active role with a young male slave, known as a catamite or puer delicatus. The latter was allowed because anal intercourse was considered equivalent to vaginal intercourse in this way; men were said to "take it like a woman" (muliebria pati, "to undergo womanly things") when they were anally penetrated, but when a man performed anal sex on a woman, she was thought of as playing the boy's role. Likewise, women were believed to only be capable of anal sex or other sex acts with women if they possessed an exceptionally large clitoris or a dildo. The passive partner in any of these cases was always considered a woman or a boy because being the one who penetrates was characterized as the only appropriate way for an adult male citizen to engage in sexual activity, and he was therefore considered unmanly if he was the one who was penetrated; slaves could be considered "non-citizen". Although Roman men often availed themselves of their own slaves or others for anal intercourse, Roman comedies and plays presented Greek settings and characters for explicit acts of anal intercourse, and this may be indicative that the Romans thought of anal sex as something specifically "Greek".

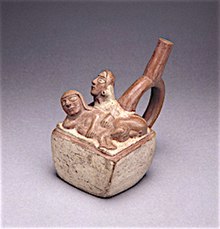

In Japan, records (including detailed shunga) show that some men engaged in penetrative anal intercourse with other men, and evidence suggestive of widespread heterosexual anal intercourse in a pre-modern culture can be found in the erotic vases, or stirrup-spout pots, made by the Moche people of Peru; in a survey, of a collection of these pots, it was found that 31 percent of them depicted heterosexual anal intercourse significantly more than any other sex act. Moche pottery of this type belonged to the world of the dead, which was believed to be a reversal of life. Therefore, the reverse of common practices was often portrayed. The Larco Museum houses an erotic gallery in which this pottery is showcased.

19th century anthropologist Richard Francis Burton theorized that there is a geographical Sotadic zone wherein penetrative intercourse between men is particularly prevalent and accepted; moreover he was one of the first writers to advance the premise that such an orientation is biologically determined.

Western cultures

In many Western countries, anal sex has generally been taboo since the Middle Ages, when heretical movements were sometimes attacked by accusations that their members practiced anal sex among themselves. At that time, celibate members of the Christian clergy were accused of engaging in "sins against nature," including anal sex.

The term buggery originated in medieval Europe as an insult used to describe the rumored same-sex sexual practices of the heretics from a sect originating in Bulgaria, where its followers were called bogomils; when they spread out of the country, they were called buggres (from the ethnonym Bulgars). Another term for the practice, more archaic, is pedicate from the Latin pedicare, with the same meaning.

The Renaissance poet Pietro Aretino advocated anal sex in his Sonetti Lussuriosi (Lust Sonnets). While men who engaged in homosexual relationships were generally suspected of engaging in anal sex, many such individuals did not. Among these, in recent times, have been André Gide, who found it repulsive; and Noël Coward, who had a horror of disease, and asserted when young that "I'd never do anything – well the disgusting thing they do – because I know I could get something wrong with me".

Religion

Judaism

The Mishneh Torah, a text considered authoritative by Orthodox Jewish sects, states "since a man’s wife is permitted to him, he may act with her in any manner whatsoever. He may have intercourse with her whenever he so desires and kiss any organ of her body he wishes, and he may have intercourse with her naturally or unnaturally , provided that he does not expend semen to no purpose. Nevertheless, it is an attribute of piety that a man should not act in this matter with levity and that he should sanctify himself at the time of intercourse."

Christianity

See also: Sodomy § ChristianityChristian texts may sometimes euphemistically refer to anal sex as the peccatum contra naturam (the sin against nature, after Thomas Aquinas) or Sodomitica luxuria (sodomitical lusts, in one of Charlemagne's ordinances), or peccatum illud horribile, inter christianos non-nominandum (that horrible sin that among Christians is not to be named).

Islam

Main article: Islamic views on anal sexLiwat, or the sin of Lot's people, which refers to same-sex sexual activity, is commonly officially prohibited by Islamic sects; there are parts of the Quran which talk about smiting on Sodom and Gomorrah, and this is thought to be a reference to unnatural sex, and so there are hadith and Islamic laws which prohibit it. While, concerning Islamic belief, it is objectionable to use the words al-Liwat and luti to refer to homosexuality because it is blasphemy toward the prophet of Allah, and therefore the terms sodomy and homosexuality are preferred, same-sex male practitioners of anal sex are called luti or lutiyin in plural and are seen as criminals in the same way that a thief is a criminal, meaning that they are giving in to a universal temptation.

Buddhism

Further information: Buddhism and sexuality and Buddhism and sexual orientationThe most common formulation of Buddhist ethics is the Five Precepts. These precepts take the form of voluntary, personal undertakings, not divine mandate or instruction. The third of the Precepts is "To refrain from committing sexual misconduct". However, "sexual misconduct" (Sanskrit: Kāmesu micchācāra, literally "sense gratifications arising from the 5 senses") is subject to interpretation relative to the social norms of the followers. Buddhism, in its fundamental form, does not define what is right and what is wrong in absolute terms for lay followers. Therefore the interpretation of what kinds of sexual activity are acceptable for a layman is not a religious matter as far as Buddhism is concerned.

Hinduism

See also: History of sex in India and LGBT topics and HinduismAlthough Hindu society does not formally acknowledge sexuality between men, it formally acknowledges and gives space to sexuality between men and third genders as a variation of male-female sex (meaning a part of heterosexuality, rather than homosexuality, if analyzed in Western terms). Hijras, Alis, Kotis, etc.— the various forms of third gender that exist in India today— are all characterized by the gender role of having receptive anal and oral sex with men. However, sexuality between men (as distinct from third genders) has thrived, mostly unspoken and informally, without being seen as different in the way it is seen in the West; young men involved in "such relationships do not consider themselves to be 'homosexual' but conceive their behavior in terms of sexual desire, opportunity and pleasure".

See also

References

Notes

- ^ "Anal Sex Safety and Health Concerns". WebMD. Retrieved August 19, 2013.

- ^ The Orgasm Answer Guide. JHU Press. 2009. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-0-8018-9396-4. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ See pages 270–271 for anal sex information, and page 118 for information about the clitoris. Janell L. Carroll (2009). Sexuality Now: Embracing Diversity. Cengage Learning. pp. 629 pages. ISBN 978-0-495-60274-3. Retrieved December 19, 2010.

- ^ Dr. John Dean and Dr. David Delvin. "Anal sex". Netdoctor.co.uk. Archived from the original on May 7, 2010. Retrieved April 29, 2010.

- ^ Human Sexuality: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. 1994. pp. 27–28. ISBN 0824079728. Retrieved July 5, 2013.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ "Heterosexual anal sexuality and anal sex behaviors: a review". Journal of Sex Research. 47 (2–3): 123–136. March 2010. doi:10.1080/00224490903402538. PMID 20358456.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ "Anal Sex, defined". Discovery.com. Archived from the original on June 13, 2002. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- ^ "Not all gay men have anal sex". Go Ask Alice!. June 13, 2008. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ Bell, Robin (February 1999). "ABC of sexual health: Homosexual men and women". BMJ. 318 (7181). National Institutes of Health/BMJ: 452–5. doi:10.1136/bmj.318.7181.452. PMC 1114912. PMID 9974466.

{{cite journal}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Sexual Health: A Public Health Perspective. McGraw-Hill International. 2012. p. 91. ISBN 0335244815. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Felice Newman (2004). The Whole Lesbian Sex Book: A Passionate Guide For All Of Us. Cleis Press. pp. 205–224. ISBN 978-1-57344-199-5. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- ^ "The male hot spot — Massaging the prostate". Go Ask Alice!. March 28, 2008. Retrieved April 21, 2010.

- ^ See page 3 for women preferring anal sex to vaginal sex, and page 15 for reaching orgasm through indirect stimulation of the G-spot. Tristan Taormino (1997). The Ultimate Guide to Anal Sex for Women. Cleis Press. pp. 282 pages. ISBN 978-1-57344-221-3. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- "Pain from anal sex, and how to prevent it". Go Ask Alice!. June 26, 2009. Retrieved April 7, 2011.

- ^ Joel J. Heidelbaugh (2007). Clinical men's health: evidence in practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 273. ISBN 978-1-4160-3000-3. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ^ Damon, W; B.R. Rosser (March–April 2005). "Anodyspareunia in Men Who Have Sex With Men: Prevalence, Predictors, Consequences, and the Development of DSM Diagnostic Criteria". Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 31 (2): 129–141. doi:10.1080/00926230590477989. PMID 15859372.

- ^ World Health Organization, Department of Reproductive Health and Research Global strategy for the prevention and control of sexually transmitted infections: 2006–2015. Breaking the chain of transmission, 2007, ISBN 978-92-4-156347-5

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance, 2008. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; November 2009.Fact Sheet

- ^ Robert I Krasner (2010). The Microbial Challenge: Science, Disease and Public Health. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 416–417. ISBN 0763797359. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- ^ Dianne Hales (2008). An Invitation to Health Brief 2010-2011. Cengage Learning. pp. 269–271. ISBN 0495391921. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- ^ Lifetime Fitness and Wellness: A Personalized Program. Cengage Learning. 2010. p. 455. ISBN 1133008585. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Psychology Applied to Modern Life: Adjustment in the 21st century. Cengage Learning. 2008. p. 422. ISBN 978-0-495-55339-7. Retrieved February 26, 2011.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Understanding Sexual Interaction. Houghton Mifflin (Original from the University of Virginia). 2008 . p. 123. ISBN 978-0-395-29724-7. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Hunko, Celia (February 6, 2009). "Anal sex: Let's get to the bottom of this". The Daily of the University of Washington. Archived from the original on April 28, 2010. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hawley, John C (2008). LGBTQ America Today: An Encyclopedia, Volume 1. Greenwood Press. p. 977. ISBN 0313339902. Retrieved July 5, 2013.

- ^ Zdrok, Victoria (2004). The Anatomy of Pleasure. Infinity Publishing. pp. 100–102. ISBN 0741422484. Retrieved July 5, 2013.

- ^ Rosenthal, Martha (2012). Human Sexuality: From Cells to Society. Cengage Learning. pp. 133–135. ISBN 978-0-618-75571-4. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- The A-Spot, Talk Sex with Sue Johanson, 2005. Retrieved April 29, 2007.

- The G spot and other recent discoveries about human sexuality. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. 1982. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-03-061831-4. Retrieved April 26, 2011.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - Jones, Nicola (July 2002). "Bigger is better when it comes to the G spot". New Scientist. Archived from the original on April 13, 2010. Retrieved April 21, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Out in Theory: The Emergence of Lesbian and Gay Anthropology. University of Illinois Press. 2002. pp. 215–216. ISBN 0252070763. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - Michael W. Ross (1988). Psychopathology and Psychotherapy in Homosexuality. Psychology Press. pp. 49–50. ISBN 0866564993. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- "'I Want a Better Orgasm!'". WebMD. Archived from the original on January 13, 2009. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- Psychiatry: Diagnosis & therapy. A Lange clinical manual. Appleton & Lange (Original from Northwestern University). 1993. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-8385-1267-8.

The amount of time of sexual arousal needed to reach orgasm is variable — and usually much longer — in women than in men; thus, only 20–30% of women attain a coital climax. b. Many women (70–80%) require manual clitoral stimulation...

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - Mah, Kenneth; Binik, Yitzchak M (January 7, 2001). "The nature of human orgasm: a critical review of major trends". Clinical Psychology Review. 21 (6): 823–856. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(00)00069-6. PMID 11497209.

Women rated clitoral stimulation as at least somewhat more important than vaginal stimulation in achieving orgasm; only about 20% indicated that they did not require additional clitoral stimulation during intercourse.

- Kammerer-Doak, Dorothy; Rogers, Rebecca G. (June 2008). "Female Sexual Function and Dysfunction". Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 35 (2): 169–183. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2008.03.006. PMID 18486835.

Most women report the inability to achieve orgasm with vaginal intercourse and require direct clitoral stimulation ... About 20% have coital climaxes...

- Di Marino, Vincent (2014). Anatomic Study of the Clitoris and the Bulbo-Clitoral Organ. Springer. p. 81. ISBN 3319048945. Retrieved September 4, 2014.

- ^ O'Connell HE, Sanjeevan KV, Hutson JM (October 2005). "Anatomy of the clitoris". The Journal of Urology. 174 (4 Pt 1): 1189–95. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000173639.38898.cd. PMID 16145367.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Difference between clitoral and vaginal orgasm". Go Ask Alice!. March 28, 2008. Retrieved November 21, 2012.

- Yang, Claire J.; Cold, Christopher; et al. (April 2006). "Sexually responsive vascular tissue of the vulva". BJUI. 97 (4): 766–772. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05961.x. PMID 16536770.

- Mulhall, John P.; Incrocci, Luca; Goldstein, Irwin; Rosen, Ray (2011). Cancer and Sexual Health. Springer. p. 783. ISBN 978-1-60761-915-4. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- "Doin' the butt – objects in anus?". Go Ask Alice!. March 26, 2010. Retrieved April 22, 2010.

- ^ "Is the Female G-Spot Truly a Distinct Anatomic Entity?". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2011 (3): 719–26. January 2012. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02623.x. PMID 22240236.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help) - ^ Sex and Society, Volume 2. Marshall Cavendish Corporation. 2009. p. 590. ISBN 978-0-7614-7907-9. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - 20 Common Problems in Women's Health Care. McGraw-Hill Health Professions Division. 2000–2008. pp. 138–139. ISBN 0070697671. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - Natasha Janina Valdez (2011). Vitamin O: Why Orgasms Are Vital to a Woman's Health and Happiness, and How to Have Them Every Time!. Skyhorse Publishing Inc. pp. 282 pages. ISBN 978-1-61608-311-3. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- ^ See page 560 for effects of viewing pornography with regard to anal sex, and pages 286–289 for anal sex as a birth control method. Robert Crooks, Karla Baur (2010–2011). Our Sexuality. Cengage Learning. pp. 570 pages. ISBN 0495812943. Retrieved May 7, 2013.

- ^ Karen Boyle (2010). Everyday Pornography. Routledge. pp. 170–171. ISBN 0203847555. Retrieved May 7, 2013.

- ^ Thomas Johansson (2007). The Transformation of Sexuality: Gender And Identity In Contemporary Youth Culture. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 56–58. ISBN 1409490785. Retrieved May 7, 2013.

- ^ Carballo-Diéguez, Alex; Stein, Z.; Saez, H.; Dolezal, C.; Nieves-Rosa, L.; Diaz, F. (2000). "Frequent use of lubricants for anal sex among men who have sex with men" (PDF). American Journal of Public Health. 90 (7): 1117–1121. doi:10.2105/AJPH.90.7.1117. PMC 1446289. PMID 10897191.

- Adrian Howe (2008). Sex, Violence and Crime: Foucault and the 'Man' Question. Routledge. p. 35. ISBN 0203891279. Retrieved July 16, 2013.

- Essential Concepts for Healthy Living. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. 2012. p. 144. ISBN 1449630626. Retrieved July 16, 2013.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - "I'm a woman who cannot feel pleasurable sensations during intercourse". Go Ask Alice!. October 17, 2008. Archived from the original on January 7, 2011. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- SIECUS Prevalence of Unprotected Anal Sex among Teens Requires New Education Strategies" Accessed January 26, 2010

- ^ See here and pages 48–49 for the majority of researchers and heterosexuals defining virginity loss/"technical virginity" by whether or not a person has engaged in vaginal sex. Laura M. Carpenter (2005). Virginity lost: an intimate portrait of first sexual experiences. NYU Press. pp. 295 pages. ISBN 978-0-8147-1652-6. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- Bryan Strong, Christine DeVault, Theodore F. Cohen (2010). The Marriage and Family Experience: Intimate Relationship in a Changing Society. Cengage Learning. p. 186. ISBN 0-534-62425-1. Retrieved October 8, 2011.

Most people agree that we maintain virginity as long as we refrain from sexual (vaginal) intercourse. ...But occasionally we hear people speak of 'technical virginity' ... Other research, especially research looking into virginity loss, reports that 35% of virgins, defined as people who have never engaged in vaginal intercourse, have nonetheless engaged in one or more other forms of heterosexual activity (e.g. oral sex, anal sex, or mutual masturbation). ... Data indicate that 'a very significant proportion of teens ha had experience with oral sex, even if they haven't had sexual intercourse, and may think of themselves as virgins'.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Jayson, Sharon (October 19, 2005). "'Technical virginity' becomes part of teens' equation". USA Today. Retrieved August 7, 2009.

- Ken Plummer (2002). Modern Homosexualities: Fragments of Lesbian and Gay Experiences. Routledge. pp. 187–191. ISBN 1134922426. Retrieved August 24, 2013.

The social construction of 'sex' as vaginal intercourse affects how other forms of sexual activity are evaluated as sexually satisfying or arousing; in some cases whether an activity is seen as a sexual act at all. For example, unless a woman has been penetrated by a man's penis she is still technically a virgin even if she has had lots of sexual experience.

- William D. Mosher, PhD; Anjani Chandra, PhD; and Jo Jones, PhD, Sexual Behavior and Selected Health Measures: Men and Women 15–44 Years of Age, U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES, Division of Vital Statistics, September 15, 2005

- Anne-Christine d'Adesky, Expanding Microbicide Research in amfAR Global Link – Treatment Insider; May 2004

- Leichliter JS, Chandra A, Liddon N, Fenton KA, Aral SO (December 2007). "Prevalence and correlates of heterosexual anal and oral sex in adolescents and adults in the United States". J. Infect. Dis. 196 (12): 1852–9. doi:10.1086/522867. PMID 18190267.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Bradley Hasbro Children's Research Center".

- National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior (NSSHB). Findings from the National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior, Center for Sexual Health Promotion, Indiana University. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, Vol. 7, Supplement 5. 2010.

- Yi, Ung-hoe; Sin, Jong-seong; Choe, Hyeong-gi (1999). "한국여성의 성형태에 대한 연구 (Sexual Behavior of Korean Women)". Daehan Namseong Gwahak Hoeji. 17 (3): 177–185.

- "Les pratiques sexuelles des Françaises" (in French). TNS/Sofres. Archived from the original on April 29, 2007. Retrieved April 30, 2007. Survey carried out by TNS/Sofres in a representative sample of 500 women from 18 to 65 years of age, in April and May 2002.

- "Healthy sex is all in the talk". The Georgia Straight. May 5, 2005. Archived from the original on June 29, 2007. Retrieved June 14, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Introducing the New Sexuality Studies: 2nd Edition. Routledge. 2011. pp. 108–112. ISBN 1136818103. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Edwin Clark Johnson, Toby Johnson (2008). Gay Perspective: Things Our Homosexuality Tells Us about the Nature of God & the Universe. Lethe Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-59021-015-4. Retrieved February 12, 2011.

- Goldstone, Stephen E.; Welton, Mark L. (2004). "Sexually Transmitted Diseases of the Colon, Rectum, and Anus". Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 17 (4): 235–239. PMC 2780055. PMID 20011265.

- ^ Steven Gregory Underwood (2003). Gay Men and Anal Eroticism: Tops, Bottoms, and Versatiles. Harrington Park Press. pp. 225 pages. ISBN 978-1-56023-375-6. Retrieved February 12, 2011.

- Role versatility among men who have sex with men in urban Peru. In: The Journal of Sex Research, August 2007

- ^ Raymond A. Smith (1998). Encyclopedia of AIDS: A Social, Political, Cultural and Scientific Record of the HIV Epidemic. Taylor & Francis. pp. 73–76. ISBN 0203305493. Retrieved December 23, 2013.

- ^ "The New Sex Police". The Advocate. April 12, 2005. pp. 39–40, 42. Retrieved February 12, 2011.

- John H. Harvey, Amy Wenzel, Susan Sprecher (2004). The handbook of sexuality in close relationships. Routledge. pp. 355–356. ISBN 0805845488. Retrieved March 12, 2011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Odets, Walt (1995). In the Shadow of the Epidemic: Being Hiv-negative in the Age of AIDS. Duke University Press. pp. 191–192. ISBN 0822316382. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- ^ Joe Perez (2006). Rising Up. Lulu.com. pp. 190–192. ISBN 1-4116-9173-3. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

- Joseph Gross, Michael (2003). Like a Virgin. pp. 44–45. 0001-8996. Retrieved March 12, 2011.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Dolby, Tom (February 2004). "Why Some Gay Men Don't Go All The Way". Out. pp. 76–77. Retrieved February 12, 2011.

- William A. Percy and John Lauritsen, Review in The Gay & Lesbian Review, November–December 2002

- Harford Montgomery Hyde (1970). The Love that Dared Not Speak Its Name: A Candid History of Homosexuality in Britain. Little, Brown. pp. 6–7. Retrieved August 19, 2013.

- Sexual Behaviors and Situational Characteristics of Most Recent Male-Partnered Sexual Event among Gay and Bisexually Identified Men in the United States onlinelibrary.wiley.com Retrieved 2-13-2014

- Laumann, E., Gagnon, J.H., Michael, R.T., and Michaels, S. The Social Organization of Sexuality: Sexual Practices in the United States. 1994. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (Also reported in the companion volume, Michael et al., Sex in America: A Definitive Survey, 1994).

- Center for Disease Control, Increases in Unsafe Sex and Rectal Gonorrhea Among Men Who Have Sex With Men – San Francisco, California, 1994–1997. Retrieved April 29, 2007.

- Keesling, Barbara (2005). Sexual Pleasure: Reaching New Heights of Sexual Arousal and Intimacy. Hunter House. p. 221. ISBN 9780897934350. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- Savage, Dan (June 21, 2001). "We Have a Winner!". The Stranger. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Janell L. Carroll (2012). Discovery Series: Human Sexuality, 1st ed. Cengage Learning. p. 285. ISBN 1111841896. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- JoAnn Loulan (1984). Lesbian Sex. The University of California. p. 53. ISBN 0-933216-13-0. Retrieved February 3, 2011.

- Kat Harding (2006). The Lesbian Kama Sutra. Macmillan. p. 31. ISBN 0-312-33585-7. Retrieved February 3, 2011.

- Jonathan Zenilman, Mohsen Shahmanesh (2011). Sexually Transmitted Infections: Diagnosis, Management, and Treatment. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 329–330. ISBN 0495812943. Retrieved November 4, 2012.

- Diamant AL, Lever J, Schuster M (June 2000). "Lesbians' Sexual Activities and Efforts to Reduce Risks for Sexually Transmitted Diseases". J Gay Lesbian Med Assoc. 4 (2): 41–8. doi:10.1023/A:1009513623365.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Tom Boellstorff (2005). The Gay Archipelago: Sexuality and Nation in Indonesia. Princeton University Press. pp. 101–102. ISBN 978-0-691-12334-9. Retrieved March 12, 2011.

- Donaldson James, Susan (December 10, 2008). ".Study Reports Anal Sex on Rise Among Teens". ABC News. Archived from the original on January 26, 2011. Retrieved January 6, 2011.

But experts say that as social mores ease, more young heterosexuals are engaging in anal sex, a behavior once rarely mentioned in polite circles. And the experimentation, they worry, may be linked to the current increase in sexually transmitted diseases. "It really is shocking how many myths young people have about anal sex," said Judy Kuriansky, a Columbia University professor and author of Sexuality Education: Past Present and Future. "They don't think you can get a disease from it because you're not having intercourse," she told ABCNews.com.

- Partridge, Eric; Dalzell, Tom; Victor, Terry (2006). The New Partridge Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English: A-I (reprint ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-415-25937-8.

Bareback – to engage in sex without a condom.

- "Sexual Risk Factors". AIDS.gov. Retrieved March 4, 2011.

- High-Risk Sexual Behavior by HIV-Positive Men Who Have Sex with Men --- 16 Sites, United States, 2000—2002, MMWR Weekly, October 1, 2004 / 53(38);891–894. Retrieved April 29, 2007.

- ^

- "Detailed Guide: Anal Cancer What Are the Key Statistics About Anal Cancer?". American Cancer Society. May 2, 2014. Retrieved September 14, 2014.

- "What are the risk factors for anal cancer?". American Cancer Society. May 2, 2014. Retrieved September 14, 2014.

- Sexual Transmission of Typhoid Fever: A Multistate Outbreak among Men Who Have Sex with Men, Reller, Megan E. et al., Clinical Infectious Diseases, volume 37 (2003), pages 141–144. Retrieved April 29, 2007.

- Pauk J, Huang ML, Brodie SJ; et al. (November 2000). "Mucosal shedding of human herpesvirus 8 in men". N. Engl. J. Med. 343 (19): 1369–77. doi:10.1056/NEJM200011093431904. PMID 11070101.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Weiss, Margaret D.; Wasdell, Michael B.; Bomben, Melissa M.; Rea, Kathleen J.; Freeman, Roger D.; Xue, H; Yang, H; Zhang, G; Shao, C (February 2006). "High Prevalence of Sexually Transmitted Diseases Among Men Who Have Sex With Men in Jiangsu Province, China". 33 (2): 118–123. doi:10.1097/01.olq.0000199763.14766.2b. PMID 16432484.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Robert J. Pratt (2003). HIV & AIDS: A Foundation for Nursing and Healthcare Practice. CRC Press. p. 306. ISBN 0340706392. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- Leichliter, Jami S (2008). "Heterosexual Anal Sex: Part of an Expanding Sexual Repertoire?". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 35 (11): 910–911. doi:10.1097/olq.0b013e31818af12f.

- M. Sara Rosenthal (2003). The Gynecological Sourcebook. McGraw Hill Professional. p. 153. ISBN 0071402799. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- The AIDS Crisis: What We Can Do. InterVarsity Press. 2006. p. 97. ISBN 0830833722. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - Thomas, R. Murray (2009). Sex and the American Teenager: Seeing through the Myths and Confronting the Issues. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield Education. p. 81. ISBN 9781607090182. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- Edlin, Gordon (2012). Health & Wellness. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 213. ISBN 9781449636470. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- ^ Handbook of affirmative psychotherapy with lesbians and gay men By Kathleen Ritter, Anthony I. Terndrup; p350

- ^ Rosser, B.R.; Metz, M.E.; Bockting, W.O.; Buroker, T. (Spring 1997). "Sexual difficulties, concerns, and satisfaction in homosexual men: an empirical study with implications for HIV prevention" (PDF). Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 23 (1): 61–73. doi:10.1080/00926239708404418. PMID 9094037. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- An Introduction to the Work of a Medical Examiner: From Death Scene to Autopsy Suite. ABC-CLIO. 2010. p. 29. ISBN 0275995089. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - Hagen S, Stark D (2011). "Conservative prevention and management of pelvic organ prolapse in women". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 12 (12): CD003882. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003882.pub4. PMID 22161382.

- Effect of anoreceptive intercourse on anorectal function AJ Miles, TG Allen-Mersh and C Wastell, Department of Surgery, Westminster Hospital, London; in Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine Vol 86, Issue 3 144–147; 1993. Retrieved April 29, 2007.

- Chun AB, Rose S, Mitrani C, Silvestre AJ, Wald A: Anal sphincter structure and function in homosexual males engaging in anal receptive intercourse. Amer J of Gastroenterology 92:465–468, 1997

- ^ Jeffrey S. Nevid (2008). Psychology: Concepts and Applications. Cengage Learning. p. 417. ISBN 0547148143. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

Some cultures are more permissive with respect to such sexual practices as oral sex, anal sex, and masturbation, whereas others are more restrictive.

- George Haggerty (2000–2013). Encyclopedia of Gay Histories and Cultures. Routledge. pp. 788–790. ISBN 1135585067. Retrieved December 23, 2013.

- ^ "PUBLIC AI Index: MDE 13/010/2008. UA 17/08 Fear of imminent execution/ flogging". Amnesty International. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- Christie Davies (2011). Jokes and Target. Indiana University Press. pp. 155–156. ISBN 0253223024. Retrieved December 23, 2013.

- Paul Baker (2005). Public Discourses of Gay Men. Routledge. p. 2. ISBN 0203643534. Retrieved December 23, 2013.

- ^ Joan Roughgarden (2004). Evolution's Rainbow: Diversity, Gender, and Sexuality in Nature and People. University of California Press. pp. 367–376. ISBN 0520240731. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- Andreia: Studies in Manliness and Courage in Classical Antiquity. Brill. 2003. p. 115. ISBN 9004119957. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - Encyclopedia of Sex and Gender: Men and Women in the World's Cultures Topics and Cultures A-K - Volume 1; Cultures L-Z -. Springer Science+Business Media. 2004. p. 207. ISBN 030647770X. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Anna Clark (2012). Desire: A History of European Sexuality. Routledge. p. 23. ISBN 1135762910. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- David Cohen, "Sexuality, Violence, and the Athenian Law of Hubris" Greece and Rome; V.38.2, pp 171-188

- Miller, James E. (1995). "The Practices of Romans 1:26: Homosexual or Heterosexual?". Novum Testamentum. 37 (1): 9. doi:10.1163/1568536952613631.

Heterosexual anal intercourse is best illustrated in Classical vase paintings of hetaerae with their clients, and some scholars interpret this as a form of contraception

- ^ Marilyn B. Skinner (1997). Invading the Roman Body: Manliness and Impenetrability in Roman Thought. Roman Sexualities. Princeton University Press. pp. 14–31. ISBN 0-691-01178-8. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- Thomas K. Hubbard (2003). Homosexuality in Greece and Rome: A Sourcebook of Basic Documents. University of California Press. p. 309. ISBN 0520234308. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- Gary P. Leupp (1997). Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan. University of California Press. p. 122. ISBN 052091919X. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- Reay Tannahill (1989). Sex In History. Abacus Books. pp. 297–298. ISBN 0349104867. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- "Larco Museum - Lima Peru - Experience Ancient Peru - Permanent Exhibition ::". Museolarco.org. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- Burton, Sir Richard Francis (1885). "Section D: Pederasty". "Terminal Essay", from his translation of The Arabian Nights. Fordham University.

- Herbenick, Debby. Good in Bed Guide to Anal Pleasuring. Good in Bed Guides. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0-9843221-6-9.

- Who's Who in Gay and Lesbian History Vol.1: From Antiquity to the Mid-Twentieth Century. Routledge. 2002. p. 116. ISBN 020398675X. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Erin McKean, ed. (2005). New Oxford American Dictionary, 2nd edition. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-517077-6.

- Pollini, John (March 1999). "The Warren Cup: Homoerotic Love and Symposial Rhetoric in Silver". BJUI. 81 (1): 21–52. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05961.x. PMID 16536770.

"I have derived the word pedicate from the Latin paedicare or pedicare, meaning "to penetrate anally." Note 6.

- Daileader, Celia R. (Summer 2002). "Back Door Sex: Renaissance Gynosodomy, Aretino, and the Exotic" (PDF). English Literary History. 69 (2). The Johns Hopkins University Press: 303–334. doi:10.1353/elh.2002.0012. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 16, 2007. Retrieved April 30, 2007.

- Kevin Kopelson (1994). Love's Litany: The Writing of Modern Homoerotics. Stanford University Press. p. 62. ISBN 0804723451. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- Philip Hoare (1998). Noël Coward: A Biography. University of Chicago Press. p. 18. ISBN 0226345122. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- Isidore Twersky, Introduction to the Code of Maimonides (Mishneh Torah), Yale Judaica Series, vol. XII (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1980). passim, and especially Chapter VII, "Epilogue", pp. 515–538.

- Maimonides, Moshe. Mishneh Torah. p. Laws Concerning Forbidden Relations 21:9.

- Albrecht Classen (2010). Sexuality in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Times: New Approaches to a Fundamental Cultural-historical and Literary-anthropological Theme. Walter de Gruyter. p. 13. ISBN 3110205742. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- Byrne Fone (2001). Homophobia: A History. Macmillan. p. 133. ISBN 1466817070. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- Louis Crompton (2009). Homosexuality and Civilization. Harvard University Press. p. 529. ISBN 0674030060. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- Mark M Leach (2014). Cultural Diversity and Suicide: Ethnic, Religious, Gender, and Sexual Orientation Perspectives. Routledge. p. 121. ISBN 1317786599. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- ^ Yahaya Yunusa Bambale (2008) . Crimes and Punishments Under Islamic Law. Malthouse Press Limited. p. 40. ISBN 9780231595. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- Cassell's Encyclopedia of Queer Myth, Symbol, and Spirit: Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Lore. Cassell. 2006 . pp. 20, 216. ISBN 0304337609. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

Indeed, homoeroticism in general and anal intercourse in particular are referred to as liwat, while those (primarily men) engaging in these behaviors are referred to as qaum Lut or Luti, 'the people of Lot.'

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - Higgins, Winton. "Buddhist Sexual Ethics". BuddhaNet Magazine. Archived from the original on January 21, 2007. Retrieved January 15, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Po, Jeffrey. "Sexual Misconduct – The third Precept". 4ui.com. Retrieved March 22, 2010Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - GLBT in World Religions, Sermon by Rev. Gabriele Parks, along with Phil Manos and Bill Weber.

- The social construction of male 'homosexuality' in India, by S Asthana and R. Oostvogels, published in 'Social Science & Medicine', vol 52(2001), Quote: "Indian culture is highly homosocial and displays of affection, body contact and the sharing of beds between men is socially acceptable (Kahn, 1994) This creates opportunities for sexual contact, though sexual behavior in this context is rarely seen as real sex, but as play. Much of this same-sex sexual activity begins in adolescence between school friends and within family environments and is non-penetrative... Young men who cultivate such relationships do not consider themselves to be 'homosexual' but conceive their behavior in terms of sexual desire, opportunity and pleasure."

Further reading

- Bentley, Toni The Surrender: An Erotic Memoir, Regan Books, 2004.

- Brent, Bill Ultimate Guide to Anal Sex for Men, Cleis Press, 2002.

- DeCitore, David Arouse Her Anal Ecstasy (2008) ISBN 978-0-615-39914-0

- Hite, Shere The Hite Report on Male Sexuality

- Houser, Ward Anal Sex, Encyclopedia of Homosexuality Dynes, Wayne R. (ed.), Garland Publishing, 1990. pp. 48–50.

- Manning, Lee The Illustrated Book Of Anal Sex, Erotic Print Society, 2003. ISBN 978-1-898998-59-4

- Morin, Jack Anal Pleasure & Health: A Guide for Men and Women, Down There Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0-940208-20-9

- Sanderson, Terry The Gay Man's Kama Sutra, Thomas Dunne Books, 2004.

- Strong, Bill with Lori E. Gammon Anal Sex for Couples: A Guaranteed Guide for Painless Pleasure Triad Press, Inc.; First edition, 2006. ISBN 978-0-9650716-2-8

- Tristan Taormino The Ultimate Guide to Anal Sex for Women, Cleis Press, 1997, 2006. ISBN 978-1-57344-028-8

- Underwood, Steven G. Gay Men and Anal Eroticism: Tops, Bottoms, and Versatiles, Harrington Park Press, 2003

- Webb, Charlotte Masterclass: Anal Sex, Erotic Print Society, 2007.

External links

- Anal Intercourse and Analingus – from alt.sex FAQ

- William Saletan: The Riddle of the Sphincter: Why do women who have anal sex get more orgasms? Slate, October 11, 2010.

- Anna Breslaw: The 10 Biggest Misconceptions About Anal Sex Cosmopolitan, December 31, 2013.

| Sex positions | |

|---|---|