| Revision as of 20:13, 18 October 2006 editHomestarmy (talk | contribs)9,996 edits but look closer, the source doesn't say that anyone halfway notable even makes the accusation.← Previous edit | Revision as of 20:19, 18 October 2006 edit undoThe Crying Orc (talk | contribs)545 edits →Problems with scholarship in this fieldNext edit → | ||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

| ===Problems with scholarship in this field=== | ===Problems with scholarship in this field=== | ||

| There is contention over the conclusions raised by the mainstream scholars, however, as most scholars who study in this field are committed Christians. As their personal religion means that they already |

There is contention over the conclusions raised by the mainstream scholars, however, as most scholars who study in this field are committed Christians. As their personal religion means that they already believe in 'Jesus Christ', critics of Christianity often assert they may not be able to maintain the proper degree of detachment and neutrality. This accusation has been challenged to an extent by ] and other Apologists. <ref>http://www.tektonics.org/jesusexist/jesusexisthub.html</ref> | ||

| ==Earliest known sources== | ==Earliest known sources== | ||

Revision as of 20:19, 18 October 2006

| Part of a series on |

|

| Jesus in Christianity |

| Jesus in Islam |

| Background |

| Jesus in history |

| Perspectives on Jesus |

| Jesus in culture |

- This article is part of the Jesus and history series of articles.

The historicity of Jesus concerns the historical authenticity of Jesus. This topic impacts various world religions, but especially Christianity and Islam, in which the historical details of Jesus’ life are essential.

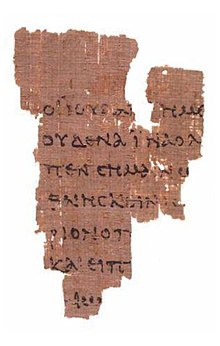

Among the earliest known sources concerning Jesus's life, the canonical Gospels and the writings of Paul are contained within the New Testament. Other possible early sources include the Gospel of Thomas, and certain hypothetical documents like an Aramaic Matthew and Q document. Lastly, a few later texts have relevance as well.

Scholarly views on the historicity of the New Testament accounts are diverse, from the view that they are historically accurate descriptions of the life of Jesus to the view that they are of virtually no historical value in reconstructing his life. The majority of scholars in the fields of biblical studies and history agree that Jesus was a Jewish teacher from Galilee (then part of Iudaea) who was regarded as a healer, was baptized by John the Baptist, was accused of sedition against the Roman Empire, and on the orders of Roman Governor Pontius Pilate was sentenced to death by crucifixion. A small minority argue that Jesus is merely a mythological figure. Questions relevant to the matter include: to what extent did the authors' motivations shape the texts, what sources were available to them, how soon after the events described did they write, and whether or not these factors lead to inaccuracies such as exaggerations or even inventions.

Problems with scholarship in this field

There is contention over the conclusions raised by the mainstream scholars, however, as most scholars who study in this field are committed Christians. As their personal religion means that they already believe in 'Jesus Christ', critics of Christianity often assert they may not be able to maintain the proper degree of detachment and neutrality. This accusation has been challenged to an extent by J.P._Moreland and other Apologists.

Earliest known sources

Christian writings

Jesus is featured throughout the New Testament and other early Christian writings, as can be seen in such works as the Gospels, the Pauline Epistles, the book of Acts, the early church father writings, and the New Testament apocrypha.

Gospels

Main articles: Gospels, Synoptic problem, and Authorship of the Johannine works

The most detailed sources of historical information about Jesus in the Bible are contained within the four canonical Gospels: Gospel of Matthew, Gospel of Mark, Gospel of Luke, and Gospel of John. The Gospels are narrative accounts of the life of Jesus, especially from the beginning of his ministry, and concluding with the Death and Resurrection of Jesus. The extent to which these sources are interrelated, or used related source material, is known as the synoptic problem; the date, authorship, access to eyewitnesses, and other essential questions of historicity depend on the various solutions to the synoptic problem.

The four canonical Gospels are anonymous. The introduction to Luke mentions other accounts by eyewitnesses, and claims to have "diligently investigated all things from the beginning." The epilogue to John identifies the source of the book as "the beloved disciple" whose "testimony we know to be true". The authors in antiquity who discussed the authorship of the Gospels generally asserted the following: Matthew was written by Matthew, an apostle of Jesus; Mark was written by Mark a disciple of Simon Peter, who was an apostle; Luke was written by Luke a disciple of Paul, and both Luke and Paul had access to eyewitnesses. Luke's second book, Acts of the Apostles, has several sections where the author relates himself doing things with Paul, such as chapters 16, 20–21, and 27–28. However, some scholars do not accept this as proof of Luke knowing Paul based on what seems to them as differences between Acts and Paul's letters. John was written by John, who was an apostle.

The first three Gospels, known as the synoptic gospels, share much material. As a result of various scholarly hypotheses attempting to explain this interdependence (see above), the traditional association of the texts with their authors has become the subject of criticism. Though some solutions retain the traditional authorship, other solutions reject some or all of these claims. The solution most commonly held in academia today, the two-source hypothesis, has Mark being written in the 60's or slightly after the year 70, with Luke and Matthew following 10-20 years later. Other solutions, such as the Augustinian hypothesis and Griesbach hypothesis, would give Matthew priority and a possible date of 40. John is most often dated to 90-100 , though a date as early as the 60s, and as late as the second century have been argued by a few.

Even in the traditional analysis, it must be asserted that the authors wrote with certain motivations and a view to a particular community and its needs. Furthermore, it is also certain the authors relied on sources, at the least their own memories and the testimony of eyewitnesses; and even the traditional analysis asserted that the later authors did not write in ignorance of some texts that preceded them, as claimed explicitly by the author of Luke. Other possible source documents have been proposed: an Aramaic Matthew, a proto-Matthew, Q document, and others, although none of these texts, if they were real, have been found.

The extent to which the Gospels were subject to additions, redactions, or interpolations is the subject of Higher criticism, which examines the extent to which a manuscript changed from its autograph, or the work as written by the original author, through manuscript transmission. Possible alterations in the Gospels include Mark 16:8-20 and John 7:53-8:11.

Other issues with the historicity of the Gospels include possible conflicts with each other, or with other historical sources. However, possible examples of this are few, the most frequent suggestions of conflict relate to the Census of Quirinius as recounted in Luke, and the two genealogies contained in Luke and Matthew.

Pauline Epistles

Main articles: Pauline epistles and Authorship of the Pauline epistlesJesus is also the subject of the writings of Paul of Tarsus, who wrote letters to various churches and individuals from c. 48-68. Paul was not an eyewitness of Jesus' life, though he knew some of Jesus' disciples including Simon Peter, and claimed knowledge of Jesus through visions.

There are traditionally fourteen letters attributed to Paul, thirteen of which claim to be written by Paul, with one anonymous letter. Current scholarship is in a general consensus in considering at least seven of the letters to be written by Paul, with views varying concerning the remaining works. In his letters, Paul quoted Jesus several times, and also offered details on the life of Jesus.

In his Epistle to the Galatians, Paul claims he went to Jerusalem three years after his encounter with Jesus on the road to Damascus. He had traveled in Arabia and back to Damascus before going to see Peter, who Paul calls an apostle of Jesus, and James, "the Lord's brother", believed by many to be James the Just. (1:18–20) Paul then says that fourteen years later he traveled back to Jerusalem, at which time he held a meeting with the Jerusalem Christians. Believed by most scholars to be the Council of Jerusalem, this was a debate with Paul arguing against the need for circumcision to be a member of the group. Paul says he won the argument and that Peter, James, and John agreed that he should be the preacher to the Gentiles. Peter later visited Paul at Antioch and associated with the Gentiles, but when certain friends of James showed up, they seem to have discouraged Peter from associating with the Gentiles, and Paul rebuked Peter for this. (2) Galatians is one of the undisputed letters of Paul and, if accepted, is early textual evidence for the existence of Jesus. Having a "brother" and "apostles" who are arguing with Paul over what Jesus' real intentions were during his life is impossible if he never existed. Acts of the Apostles, written at least twenty but probably thirty or forty years after Galatians, gives a more detailed account of the Council.

New Testament apocrypha

Jesus is a large factor in New Testament apocrypha, works excluded from the canon as it developed because they were judged not to be inspired. These texts are almost entirely dated to the mid second century or later, though a few texts, such as the Didache, may be first century in origin. Some of these works are discussed below:

Gospel of Thomas

Main article: Gospel of ThomasThe Gospel of Thomas is a collection of logia, or "sayings", and has been described as a "sayings gospel". It consists entirely of phrases that according to the book Jesus said, rather than the narrative structure of the canonical Gospels which contain events and sayings. In this way it is similar to the hypothetical Q document. Dating the text is difficult, and scholars generally give a late date of the first half of the second century, or an early date of perhaps 50 . Thus, whether this text precedes the canonical Gospels or not is a matter of debate. The text shows possible gnostic influences, is not quoted in any contemporary writings, and suffers from a paucity of manuscripts.

Gnostic texts

Gnostic texts date to the mid second century at the earliest, and show a lack of attention to history, generally avoiding the standard historical narrative in favour of sayings framed in the structure of a private, and often secret revelation, and therefore emphasize allegory. The Gnostics' opinion of Jesus varied from viewing him as docetic to complete myth, in all cases treating him as someone to allegorically attribute gnostic teachings to, his resurrection being regarded an allegory for enlightenment, in which all can take part. Nonetheless, some scholars consider these texts valuable as they were generally not subject to the influences of Christian orthodoxy.

Early Church fathers

The early church fathers, such as Papias, Polycarp, Justin Martyr, Tertullian, Eusebius and Jerome, wrote of Jesus. Papias preferred to rely on surviving witnesses who had known one of the twelve disciples, rather than what had been written in books. (Eusebius, Hist. Eccl. 3.39.3-4)

Non-Christian writings

See also: Yeshu and Yuz AsafOf the non-Christian writings from that have been preserved, very few mention Jesus or Christianity, and for that matter few of their authors showed much interest in Judea or the Near East in general. Nonetheless, the works of four major non-Christian historians contain passages relevant to Jesus: Pliny the Younger, Josephus, Suetonius, and Tacitus. However, these are generally references to early Christians rather than a historical Jesus. Pliny condemned Christians as easily led fools. There is an obscure reference to a Jewish leader called "Chrestus" in Suetonius. Tacitus, in his Annals written c. 115, mentions popular opinion about Christus, without historical details (see: Tacitus on Jesus). Of the four, Josephus' writings, which document John the Baptist, James the Just, and possibly also Jesus, are of the most interest to scholars dealing with the historicity of Jesus (see below).

Josephus

Main article: Josephus on JesusFlavius Josephus (c. 37–c. 100), a Jew and Roman citizen who worked under the patronage of the Flavians, wrote the Antiquities of the Jews in 93. In it Jesus is mentioned twice, notably in the Testimonium Flavianum, found in Antiquities 18:3.3:

About this time came Jesus, a wise man, if indeed it is appropriate to call him a man. For he was a performer of paradoxical feats, a teacher of people who accept the unusual with pleasure, and he won over many of the Jews and also many Greeks. He was the Christ. When Pilate, upon the accusation of the first men amongst us, condemned him to be crucified, those who had formerly loved him did not cease , for he appeared to them on the third day, living again, as the divine prophets foretold, along with a myriad of other marvellous things concerning him. And the tribe of the Christians, so named after him, has not disappeared to this day.

However, John Dominic Crossan and K. H. Rengstorff have noted that the passage has many internal indicators that seem to be inconsistent with the rest of Josephus' writing and with what is known about Josephus, leading them to think that part or all of the passage may have been an interpolation. Michael L. White argued: "The parallel sections of Josephus's Jewish War make no mention of Jesus, and Christian writers as late as the third century CE who made extensive use of Josephus's Antiquities show no awareness of it. Had it been there, they would have gladly used it for proof of Christian claims. Instead, these same writers, notably Origen, admit that Josephus did not believe Jesus was the messiah (Origin Commentary on Matthew 10.17;Against Celsus 1.47)." Other scholars accept only part of the passage as genuine.

Josephus later, in chapter 20:9.1, refers to the trial and execution of James, "the brother of Jesus, who was called Christ." This is considered by the majority of scholars to be authentic. However, there is debate as to whether the words who was called Christ were in the original passage.

Pliny the Younger

Pliny the Younger, the provincial governor of Pontus and Bithynia, wrote to Emperor Trajan c. 112 concerning how to deal with Christians, who refused to worship the emperor, and instead worshiped "Christus". The name Jesus is not mentioned.

Soon accusations spread, as usually happens, because of the proceedings going on, and several incidents occurred. An anonymous document was published containing the names of many persons. Those who denied that they were or had been Christians, when they invoked the gods in words dictated by me, offered prayer with incense and wine to your image, which I had ordered to be brought for this purpose together with statues of the gods, and moreover cursed Christ—none of which those who are really Christians, it is said, can be forced to do—these I thought should be discharged. Others named by the informer declared that they were Christians, but then denied it, asserting that they had been but had ceased to be, some three years before, others many years, some as much as twenty-five years. They all worshipped your image and the statues of the gods, and cursed Christ.

They asserted, however, that the sum and substance of their fault or error had been that they were accustomed to meet on a fixed day before dawn and sing responsively a hymn to Christ as to a god, and to bind themselves by oath, not to some crime, but not to commit fraud, theft, or adultery, not falsify their trust, nor to refuse to return a trust when called upon to do so. When this was over, it was their custom to depart and to assemble again to partake of food—but ordinary and innocent food. Even this, they affirmed, they had ceased to do after my edict by which, in accordance with your instructions, I had forbidden political associations. Accordingly, I judged it all the more necessary to find out what the truth was by torturing two female slaves who were called deaconesses. But I discovered nothing else but depraved, excessive superstition."

Suetonius

Gaius Suetonius (c. 69–140) wrote the following in 112 as part of his biography of Emperor Claudius in his Lives of the Twelve Caesars: Iudaeos, impulsore Chresto, assidue tumultuantes Roma expulit ("As the Jews were making constant disturbances at the instigation of Chrestus, he expelled them from Rome").

The passage refers to riots among the Jews around the year 50. The term Chrestus also appears in some later texts applied to Jesus, indicating that such a spelling error is not unthinkable. Because these events took place around 20 years after Jesus' death, the passage most likely is not refering to the person Jesus, although it could be referencing Christians. As such, this passage offer no historical information about Jesus.

Some scholars suggest Chrestus is itself a common name in Rome, meaning good or useful. It was a particularly common name for slaves, and the passage deals with a slave revolt. Therefore, these scholars conclude the passage has nothing to do with Jesus or Christians.

Tacitus

Main article: Tacitus on JesusTacitus (c. 56–c. 117) wrote two paragraphs on the subject of Christ and Christianity in 116. They state that Christians existed in Rome in an "immense multitude" at the time of the Great Fire of Rome (64). The second paragraph states that "Christ" was put to death in Judea by "the procurator Pontius Pilate" in Judea in the reign of Tiberius (14–37), after which the "superstition, repressed for a time broke out again, not only through Judea, where the mischief originated, but through the city of Rome". Tacitus' description of Christianity is decidedly negative, as he calls it a "pernicious superstition" and "something raw and shameful", which makes it improbable that the text was interpolated by later Christians.

Tacitus simply refers to "Christ"—the Greek translation of the Hebrew word "Messiah", rather than the name "Jesus", and he refers to Pontius Pilate as a "procurator", a specific post that differs from the one that the Gospels imply that he held—prefect or governor. In this instance the Gospel account is supported by archaeology, since a surviving inscription states that Pilate was prefect. It is also possible that Pilate held both offices, which was common.

Some scholars suggest that the second paragraph is merely describing Christian beliefs that were uncontroversial (i.e., that a cult leader was put to death), and that Tacitus thus had no reason not to assume as fact, even without any evidence beyond that spiritual belief. Others, including Karl Adam, argue that, as an enemy of the Christians and as a historian, Tacitus would have investigated the claim about Jesus' execution before writing it.

Biblical scholar Bart D. Ehrman summarizes the historical importance of this passage:

"Tacitus's report confirms what we know from other sources, that Jesus was executed by order of the Roman governor of Judea, Pontius Pilate, sometime during Tiberius's reign. We learn nothing, however, about the reason for this execution, or about Jesus' life and teachings."

Jewish records

- Main article: Yeshu

The Mishnah is a law code and not a record of legal proceedings nor a general history. This and other legal texts of the Roman Period were later compiled into the 30 volume collection called the Talmud. It mentions a person called Yeshu, who lived during the reign of the Hasmonean King Yannai (Jannaeus) in the early 1st century BCE and who was executed by stoning for enticing other Jews to idolatry. Despite the disimiliarity of this individual with Jesus, they are sometimes equated. The name Yeshu (ישו) uses the same letters as the abbreviation "Y.Sh.V." (יש״ו), which scribes use to stand for the longer phrase, "his name will be erased and its memory" (ימח שמו וזכרו Yemakh Shmo V-zikhro), which signifies a Jew convicted of enticing to idolatry, whose name has been blotted out. Thus, several individuals whose names the scribes refuse to preserve are also sometimes equated with Jesus.

Others

Although Celsus, a late second-century critic of Christianity, accused Jesus of being a bastard child and a sorcerer, he never questions Jesus' historicity even though he hated Christianity and Jesus. He is quoted as saying that Jesus was a "mere man". Furthermore, there is a passage of debatable significance by Lucian of Samosata, which credits Jesus as the founder of Christianity.

Jesus as a historical person

Main article: Historical JesusThe Historical Jesus is a reconstruction of Jesus using modern historical methods. Most historians consider the accounts of Jesus' life to be historically useful. Few consider the accounts of Jesus to be either entirely mythological and legendary, or entirely history per se.

Paul Barnett pointed out that "scholars of ancient history have always recognized the 'subjectivity' factor in their available sources" and "have so few sources available compared to their modern counterparts that they will gladly seize whatever scraps of information that are at hand." He noted that modern history and ancient history are two separate disciplines, with differing methods of analysis and interpretation.

In The Historical Figure of Jesus, E.P. Sanders used Alexander the Great as a paradigm—the available sources tell us much about Alexander’s deeds, but nothing about his thoughts. "The sources for Jesus are better, however, than those that deal with Alexander" and "the superiority of evidence for Jesus is seen when we ask what he thought." Thus, Sanders considers the quest for the Historical Jesus to be much closer to a search for historical details on Alexander than to those historical figures with adequate documentation.

Consequently, scholars like Sanders, Geza Vermes, John P. Meier, David Flusser, James H. Charlesworth, Raymond E. Brown, Paula Fredriksen and John Dominic Crossan argue that, although many readers are accustomed to thinking of Jesus solely as a theological figure whose existence is a matter only of religious debate, the four canonical Gospel accounts are based on source documents written within living memory of Jesus' lifetime, and therefore provide a basis for the study of the "historical" Jesus. These historians also draw on other historical sources and archaeological evidence to reconstruct the life of Jesus in his historical and cultural context.

Jesus as Myth

Main article: Jesus as mythMany scholars, such as Michael Grant, do not see significant similarity between the pagan myths and Christianity. Grant states in Jesus: An Historian's Review of the Gospels that "Judaism was a milieu to which doctrines of the deaths and rebirths of mythical gods seemed so entirely foreign that the emergence of such a fabrication from its midst is very hard to credit." However, some scholars have ventured to question the existence of Jesus as an actual historical figure. Timothy Freke and Peter Gandy suggested they could locate such doubts in early Christianity based on an interpretation of the Second Epistle of John: "many deceivers are entered into the world, who confess not that Jesus Christ is come in the flesh." Established critical scholarship maintains that the passage refers to docetism, which critical scholarship considers unrelated to the question of Jesus' existence.

The views of scholars who entirely reject Jesus' historicity are summarized in the chapter on Jesus in Will Durant's Caesar and Christ. The argument, in summary, is based on: a suggested lack of eyewitness, a lack of direct archaeological evidence, the failure of certain ancient works to mention Jesus, and alleged similarities between early Christianity and contemporary mythology.

Perhaps the most prolific of these Biblical scholars disputing the historical existence of Jesus is George Albert Wells. In more recent times, it has been advocated by Earl Doherty and Robert M. Price. Dennis R. MacDonald argued that the Gospel of Mark and parts of Acts may have been written by an ancient author practicing the common Greek form of mimesis upon the works of Homer, as he argued there are parallels to Jesus and Odysseus.

Jesus and syncretism

Certain similarities between Gnosticism, various mystery religions, and Christianity has led the mythological school to suggest that Christianity was strongly influenced by these, essentially building a mystery religion on the foundation of a Judaic tradition via the fulfilment of Old Testament prophesies. More generally, it would have included mythologizing a Jewish leader into a Son of God.

Some of the most well-known early adherents of the mythological school include Voltaire, Friedrich Engels, Karl Kautsky, David Strauss (1808–74), and Paul-Louis Couchoud (1879–1959). Many of these authors did not absolutely deny Jesus' existence, but they believed the miraculous aspects of the Gospel accounts to be mythical and that Jesus' life story had been heavily manipulated to fit Messianic prophecy. Both Strauss and Kautsky argued that the surviving documents are of little value concerning the historical Jesus. According to the Slovenian scholar Anton Strle, Nietzsche lost his faith in Christianity as a result of reading Strauss' book Leben Jesu.

More recently, writer Timothy Freke and scholar of mystery religions Peter Gandy, who wrote The Jesus Mysteries, think that Jesus did not exist as a historical figure but was in fact one of the forms of Osiris-Dionysus. The book's use as cover art of an image of Orpheus crucified, which was known to be a forgery, has caused critics to accuse them of deceptive methods.

A recent book, The Pagan Christ: Recovering the Lost Light (2004), by journalist-priest Tom Harpur, discusses another possible origin, based partly on the writings of Alvin Boyd Kuhn and Egyptologist Gerald Massey. Massey's The Historical Jesus and Mythical Christ: A Lecture, published in 1880, explored the similarity between what has been written about Jesus and what has been written about Jehoshua Ben-Pandira, who "may have been born about the year 120 BC". From page two of the lecture: "According to the Babylonian Gemara to the Mishna of Tract 'Shabbath', this Jehoshua, the son of Pandira and Stada, was stoned to death as a wizard, in the city of Lud, or Lydda, and afterwards crucified by being hanged on a tree, on the eve of the Passover." (See Yeshu.)

Notes

- , The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocrypha, ISBN 0-19-528356-2, New Testament page 47 (Introduction to the Gospel of Mark)

- Paul Barnett, "Is the New Testament History?", p.1.

- Raymond E. Brown, The Death of the Messiah: From Gethsemane to the Grave (New York: Doubleday, Anchor Bible Reference Library 1994), p. 964; D. A. Carson, et al., p. 50-56; Shaye J.D. Cohen, From the Maccabees to the Mishnah, Westminster Press, 1987, p. 78, 93, 105, 108; John Dominic Crossan, The Historical Jesus: The Life of a Mediterranean Jewish Peasant, HarperCollins, 1991, p. xi-xiii; Michael Grant, p. 34-35, 78, 166, 200; Paula Fredriksen, Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews, Alfred A. Knopf, 1999, p. 6-7, 105-110, 232-234, 266; John P. Meier, vol. 1:68, 146, 199, 278, 386, 2:726; E.P. Sanders, pp. 12-13; Geza Vermes, Jesus the Jew (Philadelphia: Fortress Press 1973), p. 37.; Paul L. Maier, In the Fullness of Time, Kregel, 1991, pp. 1, 99, 121, 171; N. T. Wright, The Meaning of Jesus: Two Visions, HarperCollins, 1998, pp. 32, 83, 100-102, 222; Ben Witherington III, pp. 12-20.

- Bruno Bauer; Timothy Freke & Peter Gandy. The Jesus Mysteries: Was the 'Original Jesus' a Pagan God? London: HarperCollins Publishers, 1999, pp. 133, 158; Michael Martin; John Mackinnon Robertson; G.A. Wells. The Jesus Legend, Chicago: Open Court, 1996, p xii.

- http://www.tektonics.org/jesusexist/jesusexisthub.html

- See the commentary by St. Augustine on hypotyposeis.org; also see the fragments in Eusebius Hist. Eccl. 3.39.1, 3.39.15, 6.14.1, 6.25.

- Brown 323

- see Brown 7

- Brown 7

- Society of Biblical Studies, The Harper Collins NRSV Study Bible, San Francisco: Harper Collins Publishers, 1989, 2141, see Rom 14:14; 1 Cor 7:10; 9:14

- Miller 6

- Michael L. White, From Jesus to Christianity. HarperCollinsPublishers, 2004. P. 97–98

- Louis H. Feldman, "Josephus" Anchor Bible Dictionary, Vol. 3, pp. 990–91

- "Testimonium Flavianum". EarlyChristanWritings.com. Retrieved 2006-10-07.

- Pliny to Trajan, Letters 10.96–97

- Ehrman, p. 212

- Ehrman, p. 212

- Morton Smith, Jesus the Magician: Charlatan or Son of God? (1978) pp. 78–79.

- http://www.anthropoetics.ucla.edu/Ap0301/CELSUS.htm

- Ibid. For scholarly discussion, refer to source.

- Sanders 1993:3

- Grant p.199

- Durant 1944:553-7

- Kautsky's 1908 work Foundations of Christianity remains one of the important works in this respect)

- "In his review of this book in Gnomon, 1935, 476, Kern recants and expressed himself convinced by the expert opinion of J. Keil and R. Zahn (AGGELOS, Arch. f. neutest. Zeitgesch. und Kulturkunde, 1926, 62 ff.) that the Orpheoc Bakkikos gem is a forgery." W. C. K. Guthrie, Orpheus and Greek Religion: A Study of the Orphic Movement, 2nd ed. (London: Methuen, 1952), p. 278, n. to p. 265. This problem was identified by James Hannam; see his comments on his Blog

References

- Adam, Karl (1933). Jesus Christus. Augsburg: Haas.

- Adam, Karl (1934). The Son of God (English ed.). London: Sheed and Ward.

- Brown, Raymond E. (1997) An Introduction to the New Testament. Doubleday ISBN 0-385-24767-2

- Daniel Boyarin (2004). Border Lines. The Partition of Judaeo-Christianity. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Doherty, Earl (1999). The Jesus Puzzle. Did Christianity Begin with a Mythical Christ? : Challenging the Existence of an Historical Jesus. ISBN 0-9686014-0-5

- Drews, Arthur & Burns, C. Deslisle (1998). The Christ Myth (Westminster College-Oxford Classics in the Study of Religion). ISBN 1-57392-190-4

- Durant, Will (1944). Caesar and Christ, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0-671-11500-6

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2004). The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings. New York: Oxford. ISBN 0-19-515462-2.

- Ellegård, Alvar Jesus – One Hundred Years Before Christ: A Study In Creative Mythology, (London 1999).

- France, R.T. (2001). The Evidence for Jesus. Hodder & Stoughton.

- Freke, Timothy & Gandy, Peter. The Jesus Mysteries - was the original Jesus a pagan god? ISBN 0-7225-3677-1

- George, Augustin & Grelot, Pierre (Eds.) (1992). Introducción Crítica al Nuevo Testamento. Herder. ISBN 84-254-1277-3

- Grant, Michael, Jesus: An Historian's Review of the Gospels, Scribner, 1995. ISBN 0-684-81867-1

- Habermas, Gary R. (1996). The Historical Jesus: Ancient Evidence for the Life of Christ ISBN 0-89900-732-5

- Leidner, Harold (2000). The Fabrication of the Christ Myth. ISBN 0-9677901-0-7

- Meier, John P., A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Anchor Bible Reference Library, Doubleday

- (1991), v. 1, The Roots of the Problem and the Person, ISBN 0-385-26425-9

- (1994), v. 2, Mentor, Message, and Miracles, ISBN 0-385-46992-6

- (2001), v. 3, Companions and Competitors, ISBN 0-385-46993-4

- Mendenhall, George E. (2001). Ancient Israel's Faith and History: An Introduction to the Bible in Context. ISBN 0-664-22313-3

- Messori, Vittorio (1977). Jesus hypotheses. St Paul Publications. ISBN 0-85439-154-1

- Miller, Robert J. Editor (1994) The Complete Gospels. Polebridge Press. ISBN 0-06-065587-9

- New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocrypha, New Revised Standard Version. (1991) New York, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-528356-2

- Price, Robert M. (2000). Deconstructing Jesus. Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-57392-758-9

- Strobel, Lee. (1998) The Case for Christ. Zondervan. ISBN 0-310-20930-7

- Voorst, Robert Van (2000). Jesus Outside of the New Testament. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

- Wells, George A. (1988). The Historical Evidence for Jesus. Prometheus Books. ISBN 0-87975-429-X

- Wells, George A. (1998). The Jesus Myth. ISBN 0-8126-9392-2

- Wells, George A. (2004). Can We Trust the New Testament?: Thoughts on the Reliability of Early Christian Testimony. ISBN 0-8126-9567-4

- Wilson, Ian (2000). Jesus: The Evidence (1st ed.). Regnery Publishing.

See also

|

|

External links

- Extrabiblical, Non-Christian Witnesses to Jesus before 200 a.d., an argument from a Christian point of view.

- From Jesus to Christ, a PBS site.

- Why I Believe The New Testament Is Historically Reliable by Gary Habermas

- Historical Evidence for the Resurrection of Christ, a Christian discussion on the reliability of textual evidence.

- The Historical Jesus and Mythical Christ by Gerald Massey

- Historicity Of Jesus FAQ (1994), a critical look at textual evidence.

- Jesus: A Historical Reconstruction

- The New Testament Documents: Are They Reliable?, by F.F. Bruce.

- The Origins of Christianity, a discussion of potential syncretisms with other religions.

- The Quest of the Historical Jesus: A Critical Study of its Progress from Reimarus to Wrede, by Albert Schweitzer

- Scholarly opinions on the Jesus Myth, by Christopher Price

- Quest for the Historical Jesus

- The Jesus Puzzle by Earl Doherty

- The Homeric Epics and the Gospel of Mark A review of Dennis R. MacDonald's book by Richard Carrier

- Arguments that a historical Jesus never existed