| Revision as of 20:52, 23 October 2018 editGråbergs Gråa Sång (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers57,451 edits →Sex, marriage and family: tag← Previous edit | Revision as of 20:58, 23 October 2018 edit undoJenhawk777 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users54,913 edits →Sex, marriage and family: removed tag; reference was at the end of the next sentence indicating everything following the previous refence came from the same place, but I went ahead and added it so it is clearerNext edit → | ||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

| Philosopher Michael Berger says, the rural family was the backbone of biblical society. Women did tasks as important as those of men, managed their households, and were equals in daily life, but all public decisions were made by men. Men had specific obligations they were required to perform for their wives including the provision of clothing, food, and sexual relations.<ref>]. ''Biblical Literacy: The Most Important People, Events, and Ideas of the Hebrew Bible''. New York: William Morrow and Company, 1997. p. 403.</ref> Ancient Israel was a frontier and life was "tough." Everyone was a "small holder" and had to work hard to survive. A large percentage of children died early, and those that survived, learned to share the burdens and responsibilities of family life as they grew. The marginal environment required a strict authority structure: parents had to not just be honored but not be challenged. Ungovernable children, especially adult children, had to be kept in line or eliminated. Respect for the dead was obligatory, and sexual lines were rigidly drawn. Virginity was expected, adultery the worst of crimes, and even suspicion of adultery led to trial by ordeal.<ref name="Berger">{{cite book |last1=Berger |first1=Michael S. |editor1-last=Broyde |editor1-first=Michael J. |editor2-last=Ausubel |editor2-first=Michael |title=Marriage, Sex, and Family in Judaism |date=2005 |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc. |location=New York |isbn=0-7425-4516-4 |chapter=Marriage, Sex and Family in the Jewish Tradition: A Historical Overview}}</ref>{{rp|1,2}} Adultery was defined differently for men than for women: a woman was an adulteress if she had sexual relations outside her marriage, but if a man had sexual relations outside his marriage with an unmarried woman, a concubine or a prostitute, it was not considered adultery on his part.<ref name = "Davies1"/>{{rp|3}} A woman was considered "owned by a master."<ref name="Blumenthal">{{cite book |last1=Blumenthal |first1=David R. |editor1-last=Broyde |editor1-first=Michael J. |editor2-last=Ausubel |editor2-first=Michael |title=Marriage, Sex and Family in Judaism |date=2005 |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc. |location=New York |isbn=0-7425-4516-4 |chapter=The Images of Women in the Hebrew Bible}}</ref>{{rp|20,21}} A woman was always under the authority of a man: her father, her brothers, her husband, and since she did not inherit, eventually her eldest son.<ref name="Berger"/>{{rp|1,2}} She was subject to strict purity laws, both ritual and moral, and non-conforming sex—homosexuality, bestiality, cross dressing and masturbation—was punished. Stringent protection of the marital bond and loyalty to kin was very strong.<ref name="Berger"/>{{rp|20}} | Philosopher Michael Berger says, the rural family was the backbone of biblical society. Women did tasks as important as those of men, managed their households, and were equals in daily life, but all public decisions were made by men. Men had specific obligations they were required to perform for their wives including the provision of clothing, food, and sexual relations.<ref>]. ''Biblical Literacy: The Most Important People, Events, and Ideas of the Hebrew Bible''. New York: William Morrow and Company, 1997. p. 403.</ref> Ancient Israel was a frontier and life was "tough." Everyone was a "small holder" and had to work hard to survive. A large percentage of children died early, and those that survived, learned to share the burdens and responsibilities of family life as they grew. The marginal environment required a strict authority structure: parents had to not just be honored but not be challenged. Ungovernable children, especially adult children, had to be kept in line or eliminated. Respect for the dead was obligatory, and sexual lines were rigidly drawn. Virginity was expected, adultery the worst of crimes, and even suspicion of adultery led to trial by ordeal.<ref name="Berger">{{cite book |last1=Berger |first1=Michael S. |editor1-last=Broyde |editor1-first=Michael J. |editor2-last=Ausubel |editor2-first=Michael |title=Marriage, Sex, and Family in Judaism |date=2005 |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc. |location=New York |isbn=0-7425-4516-4 |chapter=Marriage, Sex and Family in the Jewish Tradition: A Historical Overview}}</ref>{{rp|1,2}} Adultery was defined differently for men than for women: a woman was an adulteress if she had sexual relations outside her marriage, but if a man had sexual relations outside his marriage with an unmarried woman, a concubine or a prostitute, it was not considered adultery on his part.<ref name = "Davies1"/>{{rp|3}} A woman was considered "owned by a master."<ref name="Blumenthal">{{cite book |last1=Blumenthal |first1=David R. |editor1-last=Broyde |editor1-first=Michael J. |editor2-last=Ausubel |editor2-first=Michael |title=Marriage, Sex and Family in Judaism |date=2005 |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc. |location=New York |isbn=0-7425-4516-4 |chapter=The Images of Women in the Hebrew Bible}}</ref>{{rp|20,21}} A woman was always under the authority of a man: her father, her brothers, her husband, and since she did not inherit, eventually her eldest son.<ref name="Berger"/>{{rp|1,2}} She was subject to strict purity laws, both ritual and moral, and non-conforming sex—homosexuality, bestiality, cross dressing and masturbation—was punished. Stringent protection of the marital bond and loyalty to kin was very strong.<ref name="Berger"/>{{rp|20}} | ||

| The '']'' of the Hebrew Bible is a woman free of patriarchal authority. She may be a paid prostitute, but not necessarily. She lives a life similar to a young man's, free from domestic encumbrances, with energy, a love of war, and lovers. "She is dangerous, fearsome and threatening by her freedom, and yet appealing and attractive at the same time."{{ |

The '']'' of the Hebrew Bible is a woman free of patriarchal authority. She may be a paid prostitute, but not necessarily. She lives a life similar to a young man's, free from domestic encumbrances, with energy, a love of war, and lovers. "She is dangerous, fearsome and threatening by her freedom, and yet appealing and attractive at the same time."<ref name="Blumenthal"/>{{rp|42}} Her freedom is recognized by biblical law and her sexual activity is not punishable.<ref name="Blumenthal"/>{{rp|42}} She is the source of extra-institutional sex. Therefore she is a threat to patriarchy and the family structure it supports.<ref name="Blumenthal"/>{{rp|43}} <blockquote>Dinah's brothers are outraged that their sister was treated like one; Judah goes in search of one; the people go to the Moabite women that way; Joshua's spies go to Rahab; Samson goes to one; Yiftah is the son of one, as is Jephthah; the women who have the dispute about the dead babies are called ''zonot''. The Law provides a general prohibition against turning one's daughter into one; a priest may not marry one; a bride found not to be a virgin is called one; and the professional fees of a ''zonah'' cannot be used as an offering in the sanctuary.<ref name="Blumenthal"/>{{rp|43}}</blockquote> This kind of unencumbered sexual activity became a metaphor in the Hebrew Bible for improper behavior. The people are said to act like ''zonah'' when they chased after other gods or other nations. Jerusalem and Zion are accused of playing the ''zonah.'' <ref name="Blumenthal"/>{{rp|43}} The term ''zonah'' appears 136 times in the Hebrew Bible, primarily in Ezekiel and Hosea, but the worst ''zonah'' is a married woman who acts like one. The lurid descriptions and the punishment accorded her in the Bible are both brutal and pornographic.<ref name="Blumenthal"/>{{rp|43}} | ||

| =====Hagar and Sarah===== | =====Hagar and Sarah===== | ||

Revision as of 20:58, 23 October 2018

See also: List of women in the Bible, Women in Christianity, and Women in Judaism

| Part of a series on the | |||

| Bible | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

|

|||

|

|||

Biblical studies

|

|||

| Interpretation | |||

| Perspectives | |||

|

Outline of Bible-related topics | |||

| Part of a series on | ||||||||

| Christianity and gender | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

Theology

|

||||||||

| Major positions | ||||||||

| Other positions | ||||||||

Ordination of women in Christianity

|

||||||||

| Church and society | ||||||||

Organizations

|

||||||||

Theologians and authors (by view)

|

||||||||

Theologians and authors (by branch)

|

||||||||

The women in the Bible are rarely mentioned by name, with named women representing only 5.5 to 8 percent of the total of all named characters, male and female. This suggests that women were not usually in the forefront of public life. Those women that are named, rose to prominence for reasons outside the ordinary. They are often an aspect of the over-turning of man-made power structures commonly found in a biblical literary device called a "reversal." Abigail and Esther, Jael who drove a tent peg into the enemy commander's temple while he slept, are a few examples of women who turned the tables on men with power. The founding matriarchs are mentioned by name, as are some prophetesses, judges, heroines, and Queens, while the common woman is largely, though not completely, unseen. The slave Hagar's story is told, and the prostitute Rahab's story is also told, along with a few others like them.

All Ancient Near Eastern societies were patriarchal, and the Bible is a patriarchal document, written by men from a patriarchal age. Many scholars see the primary emphasis of the Bible as reinforcing women's subordinate status. However, there are also scholars who claim there is a kind of gender blindness in the Bible as well as patriarchy. Marital laws in the Bible favored men, as did inheritance laws. There were strict laws of sexual behavior with adultery a crime punishable by stoning. A woman in ancient Bible days was always under the authority of a man and was subject to strict purity laws, both ritual and moral. However, women such as Deborah, the Shunnemite woman, and the prophetess Huldah, rise above societal limitations in their stories and help demonstrate that the Hebrew Bible does not attempt to justify cultural subordination with an ideology of superiority or "otherness." The Bible contains many noted narratives of women as both victors and victims, women who change the course of events, and women who are powerless and unable to affect their own destinies.

The New Testament refers to a number of women in Jesus’ inner circle, and he is generally seen by scholars as dealing with women with respect. The New Testament names many women in positions of leadership in the early church as well. There are controversies within the contemporary Christian church concerning women. For example, Paul the Apostle refers to Junia as "outstanding among the apostles" and there is disagreement over whether Junia was a woman and an apostle, and Mary Magdalene's role as a leader is also disputed. Sexuality has played a major role in these issues which have impacted, and continue to impact, how the modern Christian church sees the role of women. These changing views of women in the Bible are reflected in art and culture.

Legal situation of women in the Ancient Near East

Almost all Near Eastern societies of the Bronze (3000-1200 BCE) and Axial Ages (800 to 300 BCE) were patriarchal with patriarchy established in most by 3000 BCE. Eastern societies such as the Akkadians, Hittites, Assyrians and Persians relegated women to an inferior and subordinate position. There are very few exceptions. In the third millennium B.C. the Sumerians accorded women a position which was almost equal to that of men, but by the second millennium, the rights and status of women were reduced. In the West, the status of Egyptian women was high, and their legal rights approached equality with men throughout the last three millennia B.C. A few women even ruled as pharaohs. However, historian Sarah Pomeroy explains that even in those ancient patriarchal societies where a woman could occasionally become Queen, her position did not empower her female subjects.

Classics scholar Bonnie MacLachlan writes that Greece and Rome were patriarchal cultures. The roles women were expected to fill in all these ancient societies were predominantly domestic with a few exceptions such as Sparta, who fed women equally with men, and trained them to fight in the belief women would thereby produce stronger children. The predominant views of Ancient and Classical Greece were patriarchal; however, there is also a misogynistic strain present in Greek literature from its beginnings. A polarized view of women allowed some classics authors, such as Thales, Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Aristophanes and Philo, and others, to write about women as "twice as bad as men", a "pernicious race", "never to be trusted on any account", and as an inherently inferior race of beings separate from the race of men. There was a saying in ancient Greece, at various times attributed to Thales, Socrates and Plato, in which man thanked the gods that he was not uncivilized, a slave, or a woman. Life for women improved after Alexander, yet the ideology remained. Rome was heavily influenced by Greek thought. Sarah Pomeroy says "never did Roman society encourage women to engage in the same activities as men of the same social class." In The World of Odysseus, classical scholar Moses Finley says: "There is no mistaking the fact that Homer fully reveals what remained true for the whole of antiquity: that women were held to be naturally inferior..."

Laws in patriarchal societies regulated three sorts of sexual infractions involving women: rape, fornication (which includes adultery and prostitution), and incest. There is a homogeneity to these codes across time, and across borders, which implies the aspects of life that these laws enforced were established practices within the norms and values of the populations. The prominent use of corporal punishment, capital punishment, corporal mutilation, 'eye-for-an-eye' talion punishments, and vicarious punishments (children for their fathers) were standard across Mesopotamian Law. Ur-Nammu, who founded the Sumerian Third Dynasty of Ur in southern Mesopotamia, sponsored the oldest surviving codes of law dating from approximately 2200 BCE. Most other codes of law date from the second millennium BCE including the famous Babylonian Laws of Hammurabi which dates to about 1750 BCE. Ancient laws favored men, protecting the procreative rights of men as a common value in all the laws pertaining to women and sex.

In all these codes, rape is punished differently depending upon whether it occurs in the city or the country (as in Deuteronomy 22:23-27). The Hittite code also condemns a woman raped in her house presuming the man could not have entered without her permission. Fornication is a broad term for a variety of inappropriate sexual behaviors including adultery and prostitution. In the code of Hammurabi, and in the Assyrian code, both the adulterous woman and her lover are to be bound and drowned, but forgiveness could supply a reprieve. In the Biblical law,(Leviticus 20:10; Deuteronomy 22:22) forgiveness is not an option: the lovers must die (Deuteronomy 22:21,24). No mention is made of an adulterous man in any code. In Hammurabi, a woman can apply for a divorce but must prove her moral worthiness or be drowned for asking. It is enough in all codes for two unmarried individuals engaged in a sexual relationship to marry. However, if a husband later accuses his wife of not having been a virgin when they married, she will be stoned to death.

Until the codes introduced in the Hebrew Bible, most codes of law allowed prostitution. Classics scholars Allison Glazebrook and Madeleine M. Henry say attitudes concerning prostitution "cut to the core of societal attitude towards gender and to social constructions of sexuality." Many women in a variety of ancient cultures were forced into prostitution. Many were children and adolescents. According to the 5th century BC historian Herodotus, the sacred prostitution of the Babylonians was "a shameful custom" requiring every woman in the country to go to the precinct of Venus, and consort with a stranger. Some waited years for release while being used without say or pay. The initiation rituals of devdasi of pre-pubescent girls included a deflowering ceremony which gave Priests the right to have intercourse with every girl in the temple. In Greece slaves were required to work as prostitutes and had no right to decline. The Hebrew Bible code is the only of these codes that condemns prostitution.

In the code of Hammurabi, as in Leviticus, incest is condemned and punishable by death, however, punishment is dependent upon whether the honor of another man has been compromised. Genesis glosses over incest repeatedly, and in 2 Samuel and the time of King David, Tamar is still able to offer marriage to her half brother as an alternative to rape. Exodus, Leviticus and Numbers condemn all sexual relations between relatives.

Hebrew Bible (Old Testament)

According to traditional Jewish enumeration, the Hebrew canon is composed of 24 books written by various authors, using primarily Hebrew and some Aramaic, which came into being over a span of almost a millennium. The Hebrew Bible's earliest texts reflect a Late Bronze Age Near Eastern civilization, while its last text, thought by most scholars to be the Book of Daniel, comes from a second century BCE Hellenistic world.

Compared to the number of men, few women are mentioned in the Bible by name. The exact number of named and unnamed women in the Bible is somewhat uncertain because of a number of difficulties involved in calculating the total. For example, the Bible sometimes uses different names for the same woman, names in different languages can be translated differently, and some names can be used for either men or women. Professor Karla Bombach says one study produced a total of 3000-3100 names, 2900 of which are men with 170 of the total being women. However, the possibility of duplication produced the recalculation of a total of 1700 distinct personal names in the Bible with 137 of them being women. In yet another study of the Hebrew Bible only, there were a total of 1426 names with 1315 belonging to men and 111 to women. Seventy percent of the named and unnamed women in the Bible come from the Hebrew Bible. "Despite the disparities among these different calculations, ... women or women's names represent between 5.5 and 8 percent of the total , a stunning reflection of the androcentric character of the Bible." A study of women whose spoken words are recorded found 93, of which 49 women are named.

Historian Carol Meyers says the common, ordinary, everyday Hebrew woman is "largely unseen" in the pages of the Bible, and the women that are seen, are the unusual who rose to prominence. These prominent women include the Matriarchs Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, and Leah, Miriam the prophetess, Deborah the Judge, Huldah the prophetess, Abigail, who married David, Rahab, and Esther. A common phenomenon in the bible is the pivotal role that women take in subverting man-made power structures. The result is often a more just outcome than what would have taken place under ordinary circumstances. Law professor Geoffrey Miller explains that these women did not meet with opposition but were instead honored for the role they had.

Hebrew Bible views on gender

There is substantial agreement among a wide variety of scholars that the Hebrew Bible is a predominantly patriarchal document from a patriarchal age. New Testament scholar Ben Witherington III says it "limited women's roles and functions to the home, and severely restricted: (1) their rights of inheritance, (2) their choice of relationship, (3) their ability to pursue a religious education or fully participate in synagogue, and (4) limited their freedom of movement." Textual scholar Phyllis Trible says "considerable evidence depicts the Bible as a document of male supremacy." Theologian Eryl Davies writes: "From the opening chapters of the book of Genesis, where woman is created to serve as man's 'helper' (Gen.2:20-24) to the pronouncements of Paul concerning the submission of wives to their husbands and the silencing of women in communal worship (1 Cor. 14:34; Col.3:18), the primary emphasis of the Bible is on women's subordinate status." Davies says the patriarchal ethos is reflected in texts ranging from legal texts to narratives, and from the prophetic sayings to the wisdom literature.

Other scholars, such as Hebrew Bible scholar Tikva Frymer-Kensky, say there are evidences of "gender blindness" in the Hebrew Bible. Frymer-Kensky says the role of women is generally one that is subordinate to men, and the Hebrew Bible does not portray Israel as less patriarchal in practice than the cultures which surrounded it, however, unlike other ancient literature, the Hebrew Bible does not explain or justify cultural subordination by portraying women as deserving of less because of their "naturally evil" natures. The Biblical depiction of early Bronze Age culture up through the Axial Age, depicts the "essence" of women, (that is the Bible's metaphysical view of being and nature), of both male and female as "created in the image of God" with neither one inherently inferior in nature. Discussions of the nature of women are conspicuously absent from the Hebrew Bible. Biblical narratives do not show women as having different goals, desires, or strategies or as using methods that vary from those used by men not in authority. There are no personality traits described as being unique to women in the Hebrew Bible. Most theologians agree the Hebrew Bible does not depict the slave, the poor, or women, as different metaphysically in the manner other societies of the same eras, such as the Greeks, did.

Theologians Evelyn Stagg and Frank Stagg say the Ten Commandments of Exodus 20 contain aspects of both male priority and gender balance. In the tenth commandment against coveting, a wife is depicted in the examples not to be coveted: house, wife, male or female slave, ox or donkey, or 'anything that belongs to your neighbour.' On the other hand, the fifth commandment to honor parents does not make any distinction in the honor to be shown between one parent and another.

The Hebrew Bible often portrays women as victors, leaders and heroines with qualities Israel should emulate. Women such as Hagar, Tamar, Miriam, Rahab, Deborah, Esther, and Yael/Jael, are among many female "saviors" of Israel: "victor stories follow the paradigm of Israel's central sacred story: the lowly are raised, the marginal come to the center, the poor boy makes good." She goes on to say these women conquered the enemy "by their wits and daring, were symbolic representations of their people, and pointed to the salvation of Israel." The Hebrew Bible portrays women as victims as well as victors. For example, in Numbers 31, the Israelites slay the people of Midian, except for 32,000 virgin women who are kept as spoils of war. Frymer-Kensky says the Bible author uses vulnerable women symbolically "as images of an Israel that is also small and vulnerable..." She adds "This is not misogynist story-telling but something far more complex in which the treatment of women becomes the clue to the morality of the social order." Professor of Religion J. David Pleins says these tales are included by the Deuteronomic historian to demonstrate the evils of life without a centralized shrine and single political authority.

Women did have some role in ritual life as represented in the Bible, though they could not be priests. Neither could just any man, only Levites could be priests. Women (as well as men) were required to make a pilgrimage to the Temple in Jerusalem once a year (men each of the three main festivals if they could) and offer the Passover sacrifice. They would also do so on special occasions in their lives such as giving a todah ("thanksgiving") offering after childbirth. Hence, they participated in many of the major public religious roles that non-Levitical men could, albeit less often and on a somewhat smaller and generally more discreet scale. Old Testament scholar Christine Roy Yoder says that in the Book of Proverbs, the divine attribute of Holy Wisdom is presented as female. She points out that "on the one hand" such a reference elevates women, and "on the other hand" the "strange" woman also in Proverbs "perpetuates the stereotype of woman as either wholly good or wholly evil."

Sex, marriage and family

Marriage and family law in the Bible favored men over women. For example, a husband could divorce a wife if he chose to, but a wife could not divorce a husband without his consent. The law said a woman could not make a binding vow without consent of her male authority, so she could not legally marry without male approval. The practice of levirate marriage applied to widows of childless deceased husbands, not to widowers of childless deceased wives; though, if either he or she didn't consent to the marriage, a different ceremony called chalitza was done instead; this involves the widow removing her brother-in-law's shoe, spitting in front of him, and proclaiming, "This is what happens to someone who will not build his brother's house!". Laws concerning the loss of female virginity have no male equivalent. Women in biblical times depended on men economically. Women generally did not own property except in the rare case of inheriting land from a father who didn't bear sons. Even "in such cases, women would be required to remarry within the tribe so as not to reduce its land holdings". Property was transferred through the male line and women could not inherit unless there were no male heirs (Numbers 27:1-11; 36:1-12). These and other gender-based differences found in the Torah suggest that women were seen as subordinate to men; however, they also suggest that biblical society viewed continuity, property, and family unity as paramount.

Philosopher Michael Berger says, the rural family was the backbone of biblical society. Women did tasks as important as those of men, managed their households, and were equals in daily life, but all public decisions were made by men. Men had specific obligations they were required to perform for their wives including the provision of clothing, food, and sexual relations. Ancient Israel was a frontier and life was "tough." Everyone was a "small holder" and had to work hard to survive. A large percentage of children died early, and those that survived, learned to share the burdens and responsibilities of family life as they grew. The marginal environment required a strict authority structure: parents had to not just be honored but not be challenged. Ungovernable children, especially adult children, had to be kept in line or eliminated. Respect for the dead was obligatory, and sexual lines were rigidly drawn. Virginity was expected, adultery the worst of crimes, and even suspicion of adultery led to trial by ordeal. Adultery was defined differently for men than for women: a woman was an adulteress if she had sexual relations outside her marriage, but if a man had sexual relations outside his marriage with an unmarried woman, a concubine or a prostitute, it was not considered adultery on his part. A woman was considered "owned by a master." A woman was always under the authority of a man: her father, her brothers, her husband, and since she did not inherit, eventually her eldest son. She was subject to strict purity laws, both ritual and moral, and non-conforming sex—homosexuality, bestiality, cross dressing and masturbation—was punished. Stringent protection of the marital bond and loyalty to kin was very strong.

The zonah of the Hebrew Bible is a woman free of patriarchal authority. She may be a paid prostitute, but not necessarily. She lives a life similar to a young man's, free from domestic encumbrances, with energy, a love of war, and lovers. "She is dangerous, fearsome and threatening by her freedom, and yet appealing and attractive at the same time." Her freedom is recognized by biblical law and her sexual activity is not punishable. She is the source of extra-institutional sex. Therefore she is a threat to patriarchy and the family structure it supports.

Dinah's brothers are outraged that their sister was treated like one; Judah goes in search of one; the people go to the Moabite women that way; Joshua's spies go to Rahab; Samson goes to one; Yiftah is the son of one, as is Jephthah; the women who have the dispute about the dead babies are called zonot. The Law provides a general prohibition against turning one's daughter into one; a priest may not marry one; a bride found not to be a virgin is called one; and the professional fees of a zonah cannot be used as an offering in the sanctuary.

This kind of unencumbered sexual activity became a metaphor in the Hebrew Bible for improper behavior. The people are said to act like zonah when they chased after other gods or other nations. Jerusalem and Zion are accused of playing the zonah. The term zonah appears 136 times in the Hebrew Bible, primarily in Ezekiel and Hosea, but the worst zonah is a married woman who acts like one. The lurid descriptions and the punishment accorded her in the Bible are both brutal and pornographic.

Hagar and Sarah

Main articles: Hagar and Sarah

Phyllis Trible says Abraham is an important figure in the Bible, yet "his story pivots on two women." Sarah was Abraham's wife and Hagar was Sarah's personal slave who became Abraham's concubine. Sarah had borne no children though God had promised them a child. Later in the story when Sarah hears the promise of God she does not believe it. "Abraham and Sarah were already very old, and Sarah was past the age of childbearing. So Sarah laughed to herself as she thought, “After I am worn out and my lord is old, will I now have this pleasure?” (Genesis 18:10-15). Sarah gives her slave Hagar to Abraham and he has sexual relations with her and she becomes pregnant. Sarah hopes to build a family through Hagar, but Hagar "began to despise her mistress" (Genesis 16:4). Then Sarah mistreated Hagar, and she fled. God spoke to the slave Hagar in the desert, sent her home, and she bore Abraham a son, Ishmael, "a wild donkey of a man" (Genesis 16:12).

When Ishmael was 13, Abraham received the covenant practice of circumcision, and circumcised every male of his household. Later "Sarah became pregnant and bore a son to Abraham in his old age, at the very time God had promised him. Abraham gave the name Isaac to the son Sarah bore him. When his son Isaac was eight days old, Abraham circumcised him, as God had commanded him. Abraham was a hundred years old when his son Isaac was born to him" (Genesis 21:1-5). Hagar and Ishmael are sent away again and this time they do not return.

Frymer-Kensky says "This story starkly illuminates the relations between women in a patriarchy." She adds that it demonstrates the problems associated with gender intersecting with the disadvantages of class: Sarah has the power, her actions are legal not compassionate, but her motives are clear: "she is vulnerable, making her incapable of compassion toward her social inferior."

Lot's daughters

Main article: Lot's daughtersGenesis 19 narrates that Lot and his 2 daughters live in Sodom, and are visited by two angels. A mob gathers, and Lot offers them his daughters to protect the angels, but the angels intervene. Sodom is destroyed, and the family goes to live in a cave. Since there are no men around except Lot, the daughters decide to make him drink wine and have him unknowingly impregnate them. They each have a son, Moab and Ben-Ammi.

Rahab

Main article: RahabJoshua 2 begins the story of Rahab the prostitute (zonah), a resident of Jericho, who was known by both the king of Jericho and the spies, since they knew her well enough to go and stay with her. The king knew the spies were there and sent soldiers to Rahab's house to capture them, but Rahab hid them, sent the soldiers off in misdirection, and lied to the King on their behalf. She said to the spies, "I know that the Lord has given you this land and that a great fear of you has fallen on us, so that all who live in this country are melting in fear because of you. We have heard how the Lord dried up the water of the Red Sea for you when you came out of Egypt, and what you did to Sihon and Og, the two kings of the Amorites east of the Jordan, whom you completely destroyed. When we heard of it, our hearts melted in fear and everyone’s courage failed because of you, for the Lord your God is God in heaven above and on the earth below. Now then, please swear to me by the Lord that you will show kindness to my family, because I have shown kindness to you. Give me a sure sign that you will spare the lives of my father and mother, my brothers and sisters, and all who belong to them—and that you will save us from death.” (Joshua 2:9-13) She was told to tie a scarlet cord in the same window through which she helped the spies escape, and to have all her family in the house with her and not to go into the streets, and if she did not comply, their blood would be on their own heads. She did comply, and she and her whole family were saved before the city was captured and burned (Joshua 6).

Delilah

Main article: Delilah

Judges chapters 13 to 16 tell the story of Samson who meets Delilah and his end in chapter 16. Samson was meant to be a Nazarite, a specially dedicated individual, from birth, yet his story indicates he violated every requirement of the Nazarite vow. Long hair was one of the symbolic representations of his special relationship with God; no razor was supposed to touch his hair. Samson travels to Gaza and "fell in love with a woman in the Valley of Sorek whose name was Delilah. The rulers of the Philistines went to her and said, “See if you can lure him into showing you the secret of his great strength and how we can overpower him so we may tie him up and subdue him. Each one of us will give you eleven hundred shekels of silver.” Samson lies to her a couple of times then tells her the truth. "Then the Philistines seized him, gouged out his eyes and took him down to Gaza. Binding him with bronze shackles, they set him to grinding grain in the prison. But the hair on his head began to grow again after it had been shaved."

"Now the rulers of the Philistines assembled to offer a great sacrifice to Dagon their god and to celebrate, saying, “Our god has delivered Samson, our enemy, into our hands.” And they brought Samson out to entertain each other. But Samson prayed, "O Lord, remember me" and he pushed the columns holding up the Temple and killed everyone there.

The story does not call Delilah a Philistine. The valley of Sorek was Danite territory that had been overrun by Philistines, so the population there would have been mixed. Delilah was likely an Israelite or the story would have said otherwise. The Philistines offered Delilah an enormous sum of money to betray Samson. Art has generally portrayed Delilah as a type of femme fatale, but the biblical term used (pattî) means to persuade with words. Delilah uses emotional blackmail and Samson's genuine love for her to betray him. No other Hebrew biblical hero is ever defeated by an Israelite woman. Samson does not suspect, perhaps because he cannot think of a woman as dangerous, but Delilah is determined, bold and very dangerous indeed. The entire Philistine army could not bring him down. Yet Delilah did.

The Levite's concubine

Main article: Concubine of a Levite

The Levite's concubine in the book of Judges is "vulnerable as she is only a minor wife, a concubine". She is one of the biblical nameless. Frymer-Kensky says this story is also an example of class intersecting with gender and power: when she is unhappy she runs home, only to have her father give her to another, the Levite. The Levite and his concubine travel to a strange town where they are vulnerable because they travel alone without extended family to rescue them; strangers attack. To protect the Levite, his host offers his daughter to the mob and the Levite sends out his concubine. Trible says "The story makes us realize that in those days men had ultimate powers of disposal over their women." Frymer-Kensky says the scene is similar to one in the Sodom and Gomorrah story when Lot sent his daughters to the mob, but in Genesis the angels save them, and in the book of Judges God is no longer intervening. The concubine is raped to death.

The Levite butchers her body and uses it to rouse Israel against the tribe of Benjamin. Civil war follows nearly wiping out an entire tribe. To resuscitate it, hundreds of women are captured and forced into marriage. Fryman-Kensky says, "Horror follows horror." The narrator caps off the story with "in those days there was no king in Israel and every man did as he pleased." The decline of Israel is reflected in the violence against women that takes place when government fails and social upheaval occurs.

According to Old Testament scholar Jerome Creach, some feminist critiques of Judges say the Bible gives tacit approval to violence against women by not speaking out against these acts. Frymer-Kensky says leaving moral conclusions to the reader is a recognized method of writing called gapping used in many Bible stories. Biblical scholar Michael Patrick O'Connor attributed acts of violence against women described in the Book of Judges to a period of crisis in the society of ancient Israel before the institution of kingship. Yet others have alleged such problems are innate to patriarchy.

Tamar, daughter-in-Law of Judah

Main article: Tamar (Genesis)

Tamar is Judah's daughter–in–law. She was married to Judah's son Er, but Er died, leaving Tamar childless. Under levirate law, Judah's next son, Onan, was told to have sex with Tamar and give her a child, but when Onan slept with her, he "spilled his seed on the ground" rather than give her a child that would belong to his brother. Then Onan died too. "Judah then said to his daughter-in-law Tamar, 'Live as a widow in your father’s household until my son Shelah grows up.' For he thought, 'He may die too, just like his brothers'." (Genesis 38:11) But when Shelah grew up, she was not given to him as his wife. One day Judah travels to town (Timnah) to shear his sheep. Tamar "took off her widow’s clothes, covered herself with a veil to disguise herself, and then sat down at the entrance to Enaim, which is on the road to Timnah. When Judah saw her, he thought she was a prostitute, for she had covered her face. Not realizing that she was his daughter-in-law, he went over to her by the roadside and said, 'Come now, let me sleep with you'."(Genesis 38:14) He said he would give her something in return and she asked for a pledge, accepting his staff and his seal with its cord as earnest of later payment. So Judah slept with her and she became pregnant. Then she went home and put on her widow's weeds again. Months later when it was discovered she was pregnant, she was accused of prostitution (zonah), and was set to be burned. Instead, she sent Judah's pledge offerings to him saying "I am pregnant by the man who owns these." Judah recognized them and said, “She is more righteous than I, since I wouldn’t give her to my son Shelah.”

Jephthah's daughter

Main article: Jephthah's daughter

The story of Jephthah's daughter begins as an archetypal biblical hagiography of a hero. Jephthah is the son of a marginal woman, a prostitute (zonah), and as such he is vulnerable. He lives in his father's house, but when his father dies, his half-brothers reject him. According to Frymer-Kensky, "This is not right. In the ancient Near East prostitutes could be hired as surrogate wombs as well as sex objects. Laws and contracts regulated the relationship between the child of such a prostitute and children of the first wife... he could not be disinherited. Jephthah has been wronged, but he has no recourse. He must leave home." Frymer-Kensky says the author assumes the biblical audience is familiar with this, will know Jephthah has been wronged, and will be sympathetic to him.

Nevertheless, Jephthah goes out into the world and makes a name for himself as a mighty warrior—a hero of Israel. The threat of the Ammonites is grave. The brothers acknowledge their wrongdoing to gain his protection. Frymer-Kensky says Jephthah's response reveals negotiation skills and deep piety. Then he attempts to negotiate peace with Ammon but fails. War it is, with all of Israel vulnerable. Before the battle he makes a battle vow: "If you give the Ammonites into my hand...the one who comes out of the doors of my house...I will offer to YHWH." This turns out to be his daughter. Jephthah's reaction expresses his horror and sense of tragedy in three key expressions of mourning, utter defeat, and reproach. He reproaches her and himself, but foresees only his doom in either keeping or breaking his vow. Jephthah's daughter responds to his speech and she becomes a true heroine of this story. They are both good, yet tragedy happens. Frymer-Kensky summarizes: "The vulnerable heroine is sacrificed, the hero's name is gone." She adds, the author of the book of Judges knew people were sacrificing their children and the narrator of Judges is in opposition. "The horror is the very reason this story is in the book of Judges."

Some scholars have interpreted this story to mean that Jephthah's daughter was not actually sacrificed, but kept in seclusion.

Tamar, daughter of David

Main article: Tamar (daughter of David)

The story of Tamar is a literary unit consisting of seven parts. According to Frymer-Kensky, the story "has received a great deal of attention as a superb piece of literature, and several have concentrated on explicating the artistry involved." This story focuses on three of King David's children, Amnon the first born, Absalom the beloved son, and his beautiful sister Tamar.

Amnon desires Tamar deeply. Immediately after explaining Amnon's desire the narrator first uses the term sister to reveal Tamar is not only Absalom's sister but is also Amnon's sister by another mother. Phyllis Trible says the storyteller "stresses family ties for such intimacy exacerbates the coming tragedy." Full of lust, the prince is impotent to act; Tamar is a virgin and protected property. Then comes a plan from his cousin Jonadab, "a very crafty man."

Jonadab's scheme to aid Amnon pivots on David the king. Amnon pretends to be sick and David comes to see him. He asks that his sister Tamar make him food and feed him. The king orders it sending a message to Tamar. Amnon sends the servants away. Alone with her brother she is vulnerable, but Tamar claims her voice. Frymer-Kensky says Tamar speaks to Amnon with wisdom, but she speaks to a foolish man. She attempts to dissuade him, then offers the alternative of marriage, and tells him to appeal to the king. He does not listen, and rapes her.

Amnon is immediately full of shame and angrily throws Tamar out. “No!” she said to him. “Sending me away would be a greater wrong than what you have already done to me.” But he refuses to listen. Tamar is desolate: ruined and miserable. King David is furious but he does nothing to avenge his daughter or punish his son. Frymer Kensky says "The reader of the story who expects that the state will provide protection for the vulnerable now sees that the state cannot control itself." Absalom is filled with hatred, and kills Amnon two years later. Absalom then rebels against his father and is also killed.

Bathsheba

Main article: BathshebaIn the Book of Samuel, Bathsheba is a married woman who is noticed by king David. He has her brought to him, and she becomes pregnant. David successfully plots the death of her husband Uriah, and she becomes one of David's wives. Their child is killed as divine punishment, but Bathsheba later has another child, Solomon. In the Book of Kings, when David is old, she and the prophet Nathan convince David to let Solomon take the throne instead of an older brother.

Noted women in the Hebrew Bible

Eve

Main article: Eve

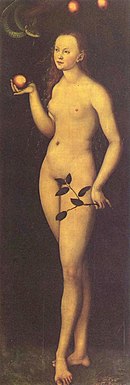

The story of Eve begins in Genesis 2:18 when "The Lord God said, 'It is not good for the man to be alone. I will make a helper suitable for him'... Then the Lord God made a woman from the rib he had taken out of the man, and he brought her to the man... That is why a man leaves his father and mother and is united to his wife, and they become one flesh. Adam and his wife were both naked, and they felt no shame.” (Genesis 2:18-25) Eve is deceived, tempted and indulges, then shares with her husband who apparently neither questions nor argues. Their eyes are opened and they realize they are naked, and they make coverings from fig leaves. When God comes to the garden, they hide, and God knows something is wrong. Everyone attempts to shift the blame, but they all end up bearing the responsibility, each receiving their own curses, and getting thrown out of the garden together. (Genesis 2)

According to Near Eastern scholar Carol Meyers, "Perhaps more than any other part of the Bible, has influenced western notions of gender and identity." Sociologist Linda L. Lindsey says "women have born a greater burden for 'original sin'... Eve's creation from Adam's rib, second in order, with God's "curse" at the expulsion is a stubbornly persistent frame used to justify male supremacy." Trible and Frymer-Kensky find the story of Eve in Genesis implies no inferiority of Eve to Adam; the word helpmate (ezer) connotes a mentor in the Bible rather than an assistant and is used frequently for the relation of God to Israel (not Israel to God). Trible points out that, in mythology, the last-created thing is traditionally the culmination of creation, which is implied in Genesis 1 where man is created after everything else—except Eve. However, New Testament scholar Craig Blomberg says ancient Jews might have seen the order of creation in terms of the laws of primogeniture (both in their scriptures and in surrounding cultures) and interpreted Adam being created first as a sign of privilege.

Deborah

Main article: Deborah Deborah Beneath the Palm Tree (c. 1896-1902) by James Tissot

Deborah Beneath the Palm Tree (c. 1896-1902) by James Tissot

The Book of Judges tells the story of Deborah, as a prophet (Judges 4:4 ), a judge of Israel (Judges 4:4-5), the wife of Lapidoth and a mother (Judges 5:7). She was based in the region between Ramah in Benjamin and Bethel in the land of Ephraim. Deborah could also be described as a warrior, leader of war, and a leader of faith. (Judges 4:6-22).

The narrative describes the people of Israel as having been oppressed by Jabin, the king of Canaan, for twenty years. Deborah sends a prophetic message to Barak to raise an army and fight them, but Barak refuses to do so without her. Deborah declares his refusal means the glory of the victory will belong to a woman. A battle is fought (led by Barak), and Sisera, the enemy commander, is defeated. Sisera escapes on foot, comes to the tent of the woman Jael, and lies down to rest. While he is asleep, Jael hammers a tent-pin through his temple.

Jael/Yael

Main article: JaelIn the days of Deborah the judge and Barak the leader of the army, they led a campaign against Sisera the commander of the army of Canaan. Sisera summoned all his men and 900 iron chariots, but Sisera was routed and fled on foot. "Barak pursued the chariots and army as far as Harosheth Haggoyim, and all Sisera’s troops fell by the sword; not a man was left. Sisera, meanwhile, fled on foot to the tent of Jael, the wife of Heber the Kenite, because there was an alliance between Jabin king of Hazor and the family of Heber the Kenite." Jael gave him drink, covered him with a blanket, and when, exhausted from battle, Sisera slept, Jael picked up a tent peg and a hammer and drove the peg into his temple all the way into the ground and he died.

The Shunammite woman

Main article: Woman of Shunem

2 Kings 4 tells of a woman in Shunem who treated the prophet Elijah with respect, feeding him and providing a place for him to stay whenever he traveled through town. One day Elisha asked his servant what could be done for her and the servant said, she has no son. So Elisha called her and said, this time next year she would have a son. She does, the boy grows, and then one day he dies. She placed the child's body on Elisha's bed and went to find him. "When she reached the man of God at the mountain, she took hold of his feet. Gehazi came over to push her away, but the man of God said, 'Leave her alone! She is in bitter distress, but the Lord has hidden it from me and has not told me why.' 'Did I ask you for a son, my lord?' she said. 'Didn’t I tell you, ‘Don’t raise my hopes’?” And she refuses to leave Elisha who goes and heals the boy.

Biblical scholar Burke Long says the "great woman" of Shunnem who appears in the Book of Kings acknowledges and respects the prophet Elisha's position yet is also a "determined mover and shaper of events." According to Frymer-Kensky, this narrative demonstrates how gender intersects with class in the Bible's portrayal of ancient Israel. The Shunammite's story takes place among the rural poor, and against this "backdrop of extreme poverty, the Shunammite is wealthy, giving her more boldness than poor women or sometimes even poor men." She is well enough off she is able to extend a kind of patronage to Elisha, and is independent enough she is willing to confront the prophet and King in pursuit of the well being of her household.

Huldah

Main article: Huldah2 Kings 22 shows it was not unusual for women to be prophetesses in ancient Israel even if they could not be priests. Josiah the King was having the Temple repaired when the High Priest Hilkiah found the Book of the Law which had been lost. He gave it to Shaphan the king's scribe, who read it, then Shaphan took it and gave it to King Josiah. The king tore his robes in distress and said "Go and inquire of the Lord for me ..." So they did, going to the prophet Huldah the wife of Shallum. The text does not comment on the fact this prophet was a woman, but says only that they took her answer back to the king (verse 20) thereby demonstrating there was nothing unusual in a female prophet.

Abigail

Main article: AbigailAbigail was the wife of Nabal, who refused to assist the future king David after having accepted his help. Abigail, realizing David's anger will be dangerous to the entire household, acts immediately. She intercepts David bearing gifts and, with what Frymer-Kensky describes as Abigail's "brilliant rhetoric", convinces David not to kill anyone. When Nabal later dies, David weds her. Frymer-Kensky says "Once again an intelligent determined woman is influential far beyond the confines of patriarchy" showing biblical women had what anthropology terms informal power.

Ruth

Ruth is the title character of the Book of Ruth. In the narrative, she is not an Israelite but rather is from Moab; she marries an Israelite. Both her husband and her father-in-law die, and she helps her mother-in-law, Naomi, find protection. The two of them travel to Bethlehem together, where Ruth wins the love of Boaz through her kindness.

She is one of five women mentioned in the genealogy of Jesus found in the Gospel of Matthew, alongside Tamar, Rahab, the "wife of Uriah" (Bathsheba), and Mary.

Esther

Esther is described in the Book of Esther as a Jewish queen of the Persian king Ahasuerus. In the narrative, Ahasuerus seeks a new wife after his queen, Vashti, refuses to obey him, and Esther is chosen for her beauty. The king's chief advisor, Haman, is offended by Esther's cousin and guardian, Mordecai, and gets permission from the king to have all the Jews in the kingdom killed. Esther foils the plan, and wins permission from the king for the Jews to kill their enemies, and they do so. Her story is the traditional basis for Purim, which is celebrated on the date given in the story for when Haman's order was to go into effect, which is the same day that Jews kill their enemies after the plan is reversed.

New Testament

See also: Women in ChristianityThe New Testament is the second part of the Christian Bible. It tells about the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christianity. It consists of four narratives called gospels about the life, teaching, death and resurrection of Jesus. It includes a record of the Apostolic ministries in the early church, called the Acts of the Apostles; twenty-one letters called "epistles" written by various authors to specific groups with specific needs concerning Christian doctrine, counsel, instruction, and conflict resolution; and one Apocalyptic book, the Book of Revelation, which is a book of prophecy, containing some instructions to seven local congregations of Asia Minor, but mostly containing prophetical symbology about the end times.

New Testament views on gender

The New Testament names many women among the followers of Jesus and in positions of leadership in the early church. New Testament scholar Linda Belleville says "virtually every leadership role that names a man also names a woman. In fact there are more women named as leaders in the New Testament than men. Phoebe is a 'deacon' and a 'benefactor' (Romans 16:11-2). Mary, Lydia and Nympha are overseers of house churches (Acts 12:12; 16:15; Colossians 4:15). Euodia and Syntyche are among 'the overseers and deacons' at Philippi (Philippians 1:1; cf, 4:2-3). The only role lacking specific female names is that of 'elder'--but there male names are lacking as well."

New Testament scholar Craig Blomberg and other complementarians assert there are three primary texts that are critical to the traditional view of women and women's roles: "1 Corinthians 14:34-35, where women are commanded to be silent in the church; 1 Timothy 2:11-15 where women (according to the TNIV) are not permitted to teach or have authority over a man; and 1 Corinthians 11:2-16 where the male and female relationship is defined in terms of kephalē commonly translated head."

Jesus' interactions with women

Main article: Jesus' interactions with women

The New Testament refers to a number of women in Jesus’ inner circle. Jesus often spoke directly to women in public. The disciples were astonished to see Jesus talking with the Samaritan woman at the well of Sychar (John 4:7-26). He spoke freely with the woman taken in adultery (John 8:10–11), with the widow of Nain (Luke 7:12–13), the woman with the bleeding disorder (Luke 8:48; cf. Matt. 9:22; Mark 5:34), and a woman who called to him from a crowd (Luke 11:27–28). Similarly, Jesus addressed a woman bent over for eighteen years (Luke 13:12) and a group of women on the route to the cross (Luke 23:27-31). Jesus spoke in a thoughtful, caring manner. Each synoptic writer records Jesus addressing the woman with the bleeding disorder tenderly as “daughter” and he refers to the bent woman as a “daughter of Abraham” (Luke 13:16). Theologian Donald G. Bloesch infers that “Jesus called the Jewish women ‘daughters of Abraham’ (Luke 13:16), thereby according them a spiritual status equal to that of men.”

Jesus held women personally responsible for their own behavior as seen in his dealings with the woman at the well (John 4:16–18), the woman taken in adultery (John 8:10–11), and the sinful woman who anointed his feet (Luke 7:44–50). Jesus dealt with each as having the personal freedom and enough self-determination to deal with their own repentance and forgiveness. There are several Gospel accounts of Jesus imparting important teachings to and about women: his public admiration for a poor widow who donated two copper coins to the Temple in Jerusalem, his friendship with Mary of Bethany and Martha, the sisters of Lazarus, and the presence of Mary Magdalene, his mother, and the other women as he was crucified. New Testament scholar Ben Witherington III says "Jesus broke with both biblical and rabbinic traditions that restricted women's roles in religious practices, and He rejected attempts to devalue the worth of a woman, or her word of witness."

Women in the early church

See also: Early ChristianitySociologist Linda L. Lindsey says "Belief in the spiritual equality of the genders (Galatians 3:28) and Jesus' inclusion of women in prominent roles, led the early New Testament church to recognize women's contributions to charity, evangelism and teaching." Pliny the Younger explains in his letters to Emperor Trajan that Christianity had people from every age and rank, and both sexes, with women in leadership roles. Professor of religion Margaret Y. MacDonald uses a "social scientific concept of power" which distinguishes between power and authority to show early Christian women, while lacking overt authority, still retained sufficient indirect power and influence to play a significant role in Christianity's beginnings. According to MacDonald, much of the vociferous pagan criticism of the early church is evidence of this "female initiative" which contributed to the reasons Roman society saw Christianity as a threat. Accusations that Christianity undermined the Roman family and male authority in the home were used to stir up opposition to Christianity and negatively influence public opinion.

Some New Testament texts (1 Peter 2:12;3:15-16; 1 Timothy 3:6-7;5:14) explicitly discuss early Christian communities being burdened by slanderous rumors because of Roman society perceiving Christianity as a threat. Christians were accused of incest because they spoke of each other as brother and sister and of loving one another, and they were accused of cannibalism because of the Lord's supper as well as being accused of undermining family and society. Such negative public opinion played a part in the persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire. MacDonald says some New Testament texts reasserting traditional roles concerning the behavior of women were written in response to these dangerous circumstances.

Noted women in the New Testament

Mary the mother of Jesus

Main article: Mary, mother of Jesus

Outside of the infancy narratives, Mary is mentioned infrequently after the beginning of Jesus' public ministry. The Gospels say Mary is the one "of whom Jesus was born" (Matthew 1:16) and that she is the "favored one" (Luke 1:28). But some scholars believe the infancy narratives were interpolations by the early church. Bart Ehrman explains that Jesus is never mentioned by name in the Talmud , but there is a subtle attack on the virgin birth that refers to the illegitimate son of a Roman soldier named "Panthera." (Ehrman says, "In Greek the word for virgin is parthenos").

Mary is not introduced in the Gospels in a way that would make her seem noteworthy or deserving of special honor. She is young, resides in an insignificant town, far from the centers of power, with no special social position or status, yet she is the one granted the highest of all statuses, demonstrating the supreme reversal. When she receives the announcement of Jesus' birth, she asks "How can this be?" Then, "...let it be" (1:38). Then, Mary makes the song of Hannah her own, threading 1 Samuel into the Gospel of Luke.

In the Gospel of Luke, Mary visits Elizabeth, her cousin, twice, and twice Elizabeth calls her blessed (Luke 1:42,45). Indeed, Mary herself states all future generations will call her blessed (1:48). Mary "ponders" Simeon's warning that "a sword would pierce her soul" in Luke 2:34,35. She is troubled by Jesus staying behind in the Temple at Jerusalem at 12 and his assumption his parents would know where he was (Luke 2:49). Mary "ponders all these things in her heart."

Mary plays a minor role In the Gospel of Mark speaking only a single line in one scene and remaining silent in the second scene where the evangelist redefines the boundaries of family. The Gospel of Matthew places Mary in the company of Tamar, Rahab, Ruth and "the wife of Uriah" (Bathsheba) who all share irregular patterns of family and marriage. The Lukan Mary identifies herself with the family of God rather than the patriarchal family structure. The Gospel of John never identifies her by name, referring instead to "the mother of Jesus." Mary appears twice in John, once at the beginning of the Gospel, and once near its end. The first is the wedding feast at Cana where the wine runs out. Mary tells Jesus, and his response is "My hour has not yet come." In spite of this, Mary tells the servants, "Do whatever he says." Jesus orders 6 stone water jars filled with water, and then directs that it be taken to the steward who describes it as the "best" wine.

Jesus' mother appears again in John (19:25-27) at the crucifixion, and it is there that Jesus makes provision for the care of His mother in her senior years (John 19:25-27). Mary speaks not a word and the narrator does not describe her.

Junia

Main article: Junia (New Testament person)Paul wrote in Romans 16:7 "Greet Andronicus and Junia, my fellow Jews who have been in prison with me. They are outstanding among the apostles, and they were in Christ before I was." Bible translator Hayk Hovhannisyan says Junia was a woman and there is consensus supporting this view. "Some scholars argue that Junia was really a man by the name of Junias... Whether this name is masculine or feminine depends on how the word was accented in Greek. ...scribes wrote Junia as feminine. Examination of ancient Greek and Latin literature confirms the masculine name Junias is nowhere attested, whereas the female name Junia...is found more than 250 times..." New Testament scholar Craig S. Keener says the early church understood Andronicus and Junia to be a husband and wife apostolic team. "Paul nowhere limits the apostolic company to twelve plus himself as some have assumed." Keener says "it is unnatural to read the text as merely claiming that they had a high reputation with the apostles."

Belleville says some traditionalists translate as esteemed by the apostles. "The justification for this change is the contention that all biblical and extra-biblical parallels to Romans 16:7 are exclusive (esteemed by apostles, well known to apostles) rather than inclusive (honored as one of the apostles, "among" the apostles)... proof is wholly lacking. ...The preposition en plus the dative plural with rare exception is inclusive "in/among" and not the exclusive "to". ...the parallels... plus the dative plural bear the inclusive meaning "a notable member of the larger group."

Minister and Professor Leland E. Wilshire says New Testament critic Eldon Jay Epp's work comparing the Junia passage to Lucian's second century Dialogues of the Dead "has resolved the Junia controversy" by convincingly proving the phrase should be rendered with Junia as a female and as one of the apostles.

Priscilla

Main article: Priscilla and AquilaIn Romans 16:3-5 Paul refers to the married couple Priscilla and Aquilla as his "fellow workers" saying they risked their lives for him. Paul worked and seemingly lived with them for a considerable time, and they followed him to Ephesus before he left on his next missionary journey. In Acts 18:25,26 Luke says Apollos, a "learned man," came to Ephesus and began speaking in the synagogue. When Priscilla and Aquilla heard him, they took him with them and "explained the way of God more accurately." Hayk Hovhannisyan says "either Priscilla was unaware of , which is virtually impossible; or she knew about it and decided to rebel--or the doctrine did not exist."

Mary of Bethany

Main article: Mary of BethanyTheologian and ethicist Stanley Grenz with Professor Denise Muir Kjesbo say it was the norm in first century Palestine for the education of women to end sometime around puberty, and that most Rabbis believed it was inappropriate to instruct women in the study of the Torah. In the story of Mary of Bethany, Jesus demonstrates His willingness to turn accepted cultural expectations upside down. In Luke 10:39, the author says Mary sat "at Jesus feet." The author "chooses terminology associated with rabbinic study (compare Acts 22:3), suggesting that Mary became Jesus' student."

Mary Magdalene

Main article: Mary Magdalene

New Testament scholar Mary Ann Getty-Sullivan says Mary Magdalene, or Mary from the town of Magdala, is sometimes "erroneously identified as the sinner who anointed Jesus according to Luke's description in Luke 7:36-50. She is at times also confused with Mary of Bethany, the sister of Martha and Lazarus (John 12:1-8)", and is sometimes assumed to be the woman caught in adultery (John 7:53-8:11), though there is nothing in the text to indicate that. Luke qualifies her as "one who was healed" but otherwise little is known about her. Mary Magdalene is named first in all lists of women except the one in John 19:25 which likely indicates a position of leadership among the women. The leadership of women prompted negative pagan response. There is nothing to directly indicate Mary Magdalene was a former prostitute, and some scholars believe she was a woman of means who helped support Jesus and his ministry.

In John 20:1–13, Mary Magdalene sees the risen Jesus alone and he tells her "Don't touch me, for I have not yet ascended to my father." New Testament scholar Ben Witherington III says John is the only evangelist with a "keen interest" in portraying women in Jesus' story, yet, the "only Easter event narrated by all four evangelists concerns the visit of the women to the tomb of Jesus." Mary Magdalene and the other women go to anoint Jesus' body at the tomb, but find the body gone. Mary Magdalene is inconsolable, but she turns and Jesus' speaks to her. He calls her by name and she recognizes him. Witherington adds, "There are certain parallels between the story of the appearance to Mary and John 20:24-31 (when Jesus appears to Thomas) Mary is given an apostolic task (to go tell the men) and Thomas is not... There is little doubt the Fourth evangelist wishes to portray Mary Magdalene as important, perhaps equally important for Jesus' fledgling community as Mother Mary herself."

The Roman writer Celsus' On The True Doctrine, circa 175, is the earliest known comprehensive criticism of Christianity and survives exclusively in quotations from it in Contra Celsum, a refutation written in 248 by Origen of Alexandria. Margaret MacDonald says Celsus' study of Christian scripture led him to focus on Mary Magdalene as the witness to the resurrection, as someone deluded by the "sorcery" by which Jesus did miracles, and as someone who then becomes one of Jesus' primary "instigators" and "perpetrators". MacDonald explains that, "In Celsus' work, Mary Magdalene's role in the resurrection story denigrates its credibility... From beginning to end, the story of Jesus' life has been shaped by the 'fanciful imaginings' of women" thus lending enemy attestation to the importance of women in the early church and of Mary Magdalene herself.

MacDonald sees this negative view of Mary as reflecting a challenge taking place within the church of the second century. This was a challenge to Mary's role as a woman disciple and to leadership roles for women in general. "The challenge to Mary's position has been evaluated as an indication of tensions between the existing fact of women's leadership in Christian communities and traditional Greco-Roman views about gender roles." MacDonald adds that "Several apocryphal and gnostic texts provide evidence of such a controversy."

Female sexuality in the early church

Main article: Christianity and sexualitySee also: Christian views on marriageClassics scholar Kyle Harper references the historian Peter Brown as showing sexuality (especially female sexuality) was at the heart of the early clash over Christianity's place in the world. Views on sexuality in the early church were diverse and fiercely debated within its various communities; these doctrinal debates took place within the boundaries of the ideas in Paul's letters and in the context of an often persecuted minority seeking to define itself from the world around it. In his letters, Paul often attempted to find a middle way among these disputes, which included people who saw the gospel as liberating them from all moral boundaries, and those who took very strict moral stances. Conflicts over sexuality with the culture surrounding Christianity, as well as within Christianity itself, were fierce. These conflicts are thought by many scholars to have impacted Bible content in the later Pauline Epistles. For example, in Roman culture, widows were required to remarry within a few years of their husband's death, but Christian widows were not required to remarry and could freely choose to remain single, and celibate, with the church's support. As Harper says, "The church developed the radical notion of individual freedom centered around a libertarian paradigm of complete sexual agency." Many widows and single women were choosing not to marry, were staying celibate, and were encouraging other women to follow, but pagan response to this female activity was negative and sometimes violent toward Christianity as a whole. Margaret MacDonald demonstrates these dangerous circumstances were likely the catalysts for the "shift in perspective concerning unmarried women from Paul's days to the time of the Pastoral epistles".

The sexual-ethical structures of Roman society were built on status, and sexual modesty and shame meant something different for men than it did for women, and for the well-born than it did for the poor, and for the free citizen than it did for the slave. In the Roman Empire, shame was a social concept that was always mediated by gender and status. Classics Professor Rebecca Langlands explains: "It was not enough that a wife merely regulate her sexual behavior in the accepted ways; it was required that her virtue in this area be conspicuous." Younger says men, on the other hand, were allowed live-in mistresses called pallake. Roman society did not believe slaves had an inner ethical life or any sense of shame, since they had no status, therefore concepts of sexual morality were not applicable to slaves. Langlands points out this value system permitted Roman society to find both a husband's control of a wife's sexual behavior a matter of intense importance, and at the same time, see the husband's sex with young slave boys as of little concern.

Harper says: "The model of normative sexual behavior that developed out of Paul's reactions to the erotic culture surrounding him...was a distinct alternative to the social order of the Roman empire." For Paul, according to Harper, "the body was a consecrated space, a point of mediation between the individual and the divine." The obligation for sexual self-control was placed equally on all people in the Christian communities, men or women, slave or free. In Paul's letters, porneia, (a single name for an array of sexual behaviors outside marital intercourse), became a central defining concept of sexual morality, and shunning it, a key sign of choosing to follow Jesus. Sexual morality could be shown by forgoing sex altogether and practicing chastity, remaining virgin, or having sex only within a marriage. Harper indicates this was a transformation in the deep logic of sexual morality as personal rather than social, spiritual rather than merely physical, and for everyone rather than solely for those with status.

Contemporary views on women in the New Testament

There is no contemporary consensus on the New Testament view of women. Psychologist James R. Beck points out that "Evangelical Christians have not yet settled the exegetical and theological issues." Liberal Christianity represented by the development of historical criticism was not united in its view of women either: Elizabeth Cady Stanton tells of the committee that formed The Woman's Bible in 1895. Twenty six women purchased two Bibles and went through them, cutting out every text that concerned women, pasted them into a book, and wrote commentaries underneath. Its purpose was to challenge Liberal theology of the time that supported the orthodox position that woman should be subservient to man. The book attracted a great deal of controversy and antagonism. Contemporary Christianity is still divided between those who support equality of all types for women in the church, those who support spiritual equality with the compartmentalization of roles, and those who support a more modern equivalent of patriarchy.

The Pauline epistles and women

Main article: Paul the Apostle and women See also: Authorship of the Pauline epistlesPaul the Apostle was the first writer to give ecclesiastical directives about the role of women in the church. Some of these are now heavily disputed. There are also arguments that some of the writings attributed to Paul are pseudepigraphal post-Pauline interpolations. Scholars agree certain texts attributed to Paul and the Pauline epistles have provided much support for the view of the role of women as subservient. Others have claimed culture has imposed a particular translation upon his texts that Paul did not actually support.

1 Corinthians 14:34-35

Traditional complementarians explain that Paul distinguishes between "public and private, authoritative and non-authoritative, formal and informal" types of instruction. Linda Belleville says those distinctions are not reflected in the Greek. She also asserts traditional English translations of these verses are colored by hierarchical bias. She uses 1 Corinthians 11:2-5 to demonstrate this by showing Paul approved women "praying and prophesying," which requires speaking in the church, adding that the context of 1 Corinthians 14 is about the order of worship and is corrective not directive.

1 Timothy 2:11-15

See also: Authorship of the Pauline epistles § Pastoral epistlesAccording to Belleville, there is no other New Testament letter in which women figure as prominently as they do in 1 Timothy. "All told, 20% of the letter focuses on women." Theologian Leland Wilshire says English translations of 1 Timothy 2:12b (which contains the clause authentein andros) have traditionally been translated "to have authority." Wilshire conducted a computer study and concluded "a whole theology excluding women has been built on this clause" which the computer indicates is a mis-translation in the English. Wilshire says there is a "strange and unusual verbal infinitive, (authentein), in the original language," which is used only this once in the New Testament. He adds "no other usages of this particular word in its infinitive form can be discovered in the whole of extant Greek literature outside of later repetitions" of this verse. This word "is not one of the common words used throughout the New Testament for "exercising or having authority" nor is it the same word used to describe the activity of "ruling" by any church office within the pastoral epistles." Wilshire says there has been little to no attempt within the traditional church to solve these linguistic difficulties using philological and historical methods.

1 Timothy 5:3-16 and 3:1-7

Writings such as 1 Timothy 5:3-16 and 3:1-7 concerning the behavior of widows "reflect a heightened concern for the honor of the community" and offer a clear indication of what those who wanted to slander the community were saying. Widows in Greco-Roman society could not inherit their husband's estate and could find themselves in desperate circumstances, but almost from the beginning the church offered widows support. Roman law required a widow to remarry; The author of 1 Timothy says a woman is better off if she remains unmarried. MacDonald explains that, "Through their deeds, the widows may have confirmed the suspicion of critics that early Christianity largely involved female initiative."

She concludes that concerns about the public visibility of women are evident in the return to Roman concepts of traditional household roles in 1 Timothy 2:11-15 and in 1 Corinthians 14:34-5. There is ongoing dispute over their correct translation.

1 Corinthians 11:2-16

Wilshire says the issue in 1 Corinthians 11:3-16 is whether the term kephalē translated head implies domination or subjection. "To say that the woman is the glory of man may have the concept of ennobling rather than a subservient or demeaning meaning."

1 Peter on women

See also: Saint Peter and Authorship of the Petrine epistlesIn 1 Peter 3 wives are exhorted to submit to their husbands "so they may be won over." Theologian Scot McKnight says: "This is entirely consistent with (the author's) agenda at 2:11-12, that Christians live such holy lives that nothing can be lodged against the gospel because of their behavior;" this reference may be a reflection of cultural circumstances of negative pagan opinion.

Professor James B. Hurley presents the complementarian view saying the author of 1 Peter's statements are not just a strategy for converting pagan husbands but are a reflection of the author's belief that marriage is modeled after Christ and the church, Jesus' suffering and self-sacrifice, the lives of holy women, doing right, with both husbands and wives as "fellow heirs". Hurley says 1 Peter presents the woman's role as "of great worth" to both God and the woman herself.

Women from the Bible in art and culture

See also: Category:Operas based on the Bible

There are hundreds of examples of women from the Bible as characters in painting, sculpture, opera and film. Historically, artistic renderings tend to reflect the changing views on women from within society more than the biblical account that mentions them.