| Revision as of 16:56, 21 February 2019 view sourceJohn B123 (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, New page reviewers194,489 edits Added WL← Previous edit | Revision as of 19:42, 29 March 2019 view source Beland (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators237,170 edits {{mergeto|Commercial sexual exploitation of children}}Next edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{mergeto|Commercial sexual exploitation of children}} | |||

| {{good article}} | {{good article}} | ||

| {{infobox | {{infobox | ||

Revision as of 19:42, 29 March 2019

| It has been suggested that this article be merged into Commercial sexual exploitation of children. (Discuss) |

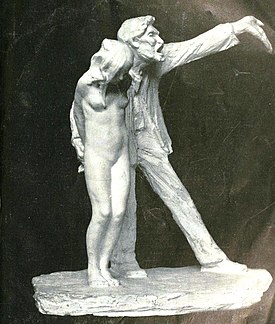

Statue of a young 19th-century prostituted child Statue of a young 19th-century prostituted childThe White Slave by Abastenia St. Leger Eberle (1878–1942) | |

| Areas practiced | Worldwide |

|---|---|

| Number affected | Up to 10 million |

| Legal status | Illegal under international law and national laws |

Child prostitution is prostitution involving a child, and it is a form of commercial sexual exploitation of children. The term normally refers to prostitution of a minor, or person under the legal age of consent. In most jurisdictions, child prostitution is illegal as part of general prohibition on prostitution.

Child prostitution usually manifests in the form of sex trafficking, in which a child is kidnapped or tricked into becoming involved in the sex trade, or survival sex, in which the child engages in sexual activities to procure basic essentials such as food and shelter. Prostitution of children is commonly associated with child pornography, and they often overlap. Some people travel to foreign countries to engage in child sex tourism. Research suggests that there may be as many as 10 million children involved in prostitution worldwide. The practice is most widespread in South America and Asia, but prostitution of children exists globally, in undeveloped countries as well as developed. Most of the children involved with prostitution are girls, despite an increase in the number of young boys in the trade.

The United Nations has declared the prostitution of children to be illegal under international law, and various campaigns and organizations have been created to protest its existence.

Definitions

Several definitions have been proposed for prostitution of children. The United Nations defines it as "the act of engaging or offering the services of a child to perform sexual acts for money or other consideration with that person or any other person". The Convention on the Rights of the Child's Optional Protocol on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution, and Child Pornography defines the practice as "the act of obtaining, procuring or offering the services of a child or inducing a child to perform sexual acts for any form of compensation or reward". Both emphasize that the child is a victim of exploitation, even if apparent consent is given. The Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, 1999, (Convention No 182) of the International Labour Organization (ILO) describes it as the "use, procuring or offering of a child for prostitution".

According to the International Labour Office in Geneva, prostitution of children and child pornography are two primary forms of child sexual exploitation, which often overlap. The former is sometimes used to describe the wider concept of commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC). It excludes other identifiable manifestations of CSEC, such as commercial sexual exploitation through child marriage, domestic child labor, and the trafficking of children for sexual purposes.

The terminology applied to the practice is a subject of dispute. The United States Department of Justice states, "The term itself implies the idea of choice, when in fact that is not the case." Groups that oppose the practice believe that the terms child prostitution and child prostitute carry problematic connotations because children are generally not expected to be able to make informed decisions about prostitution. As an alternative, they use the terms prostituted children and the commercial sexual exploitation of children. Other groups use the term child sex worker to imply that the children are not always "passive victims".

Causes and types

Children are often forced by social structures and individual agents into situations in which adults take advantage of their vulnerability and sexually exploit and abuse them by selling them or selling their bodies. Structure and agency commonly combine to force a child into commercial sex: for example, the prostitution of a child frequently follows from prior sexual abuse, often in the child's home. Many believe that the majority of prostituted children are from Southeast Asia and the majority of their clients are Western sex tourists, but sociologist Louise Brown argues that, while Westerners contribute to the growth of the industry, most of the children's customers are Asian locals.

Prostitution of children usually occurs in environments such as brothels, bars and clubs, homes, or particular streets and areas (usually in socially run down places). According to one study, only about 10% of prostituted children have a pimp and over 45% entered the business through friends. Maureen Jaffe and Sonia Rosen from the International Child Labor Study Office write that cases vary widely: "Some victims are runaways from home or State institutions, others are sold by their parents or forced or tricked into prostitution, and others are street children. Some are amateurs and others professionals. Although one tends to think first and foremost of young girls in the trade, there is an increase in the number of young boys involved in prostitution. The most disquieting cases are those children who are forced into the trade and then incarcerated. These children run the possible further risk of torture and subsequent death."

Deputy Attorney General James Cole, of the United States Department of Justice, stated, "Most of the victimized children who face prostitution are vulnerable children who are exploited. Many predators target runaways, sexual assault victims, and children who have been harshly neglected by their biological parents. Not only have they faced traumatic violence that affects their physical being, but become intertwined into the violent life of prostitution."

Human trafficking

Human trafficking is defined by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) as "the recruitment, transport, transfer, harbouring or receipt of a person by such means as threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud or deception for the purpose of exploitation". The UNODC approximates the number of victims worldwide to be around 2.5 million. UNICEF reports that since 1982 about 30 million children have been trafficked. Trafficking for sexual slavery accounts for 79% of cases, with the majority of victims being female, of which an estimated 20% are children. Women are also often perpetrators as well.

In 2007 the UN founded United Nations Global Initiative to Fight Human Trafficking (UN.GIFT). In cooperation with UNICEF, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), and the United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM) the United Nations took a grant from the United Arab Emirates to establish UN.GIFT. UN.GIFT aims to fight human trafficking through a mutual support from its stakeholders which includes governments, businesses, and other large global actors. Their first initiative is to spread the word that human trafficking is immoral and has become a growing problem that it will take a global cooperation to cease its continuation. UN.GIFT strives to lower the demand for this exploitation and create a safe environment for potential victims.

In some cases, victims of sex trafficking are kidnapped by strangers, either by force or by being tricked into becoming involved through lies and false promises. In other cases, the children's families allow or force them to enter the industry as a result of severe poverty. In cases where they are taken out of the country, traffickers prey on the fact that the children are often unable to understand the language of their new location and are unaware of their legal rights.

Research indicates that traffickers have a preference for females age 12 and under because young children are more easily molded into the role assigned to them and because they are assumed to be virgins, which is valuable to consumers. The girls are then made to appear older, and documents are forged as protection against law enforcement. Victims tend to share similar backgrounds, often coming from communities with high crime rates and lack of access to education. However, victimology is not limited to this, and males and females coming from various backgrounds have become involved in sex trafficking.

Psychotherapist Mary De Chesnay identifies five stages in the process of sex trafficking: vulnerability, recruitment, transportation, exploitation, and liberation. The final stage, De Chesnay writes, is rarely completed. Murder and accidental death rates are high, as are suicides, and very few trafficking victims are rescued or escape.

Survival sex

See also: Survival sexThe other primary form of prostitution of children is "survival sex". The US Department of Justice states:

"Survival sex" occurs when a child engages in sex acts in order to obtain money, food, shelter, clothing, or other items needed in order to survive. In these situations, the transaction typically only involves the child and the customer; children engaged in survival sex are usually not controlled or directed by pimps, madams, or other traffickers. Any individual who pays for sex with a child, whether the child is controlled by a pimp or is engaged in survival sex, can be prosecuted.

A study commissioned by UNICEF and Save the Children and headed by sociologist Annjanette Rosga conducted research on prostitution of children in post-war Bosnia and Herzegovina. Rosga reported that poverty was a strong contributing factor. She stated, "The global sex trade is as much a product of everyday people struggling to survive in dire economic straits as it is an organized crime problem. Attacking the crime and not the poverty is treating the symptom but not the disease...It's not uncommon for girls to know what they're entering into, and to enter voluntarily to some degree. Maybe they think they'll be different and able to escape, or maybe they'd rather take the risk than feel powerless staying at home in poverty." Jaffe and Rosen disagree and argue that poverty alone does not often force children into prostitution, as it does not exist in a large scale in several impoverished societies. Rather, a number of external influences, such as poor family situations and domestic violence, factor into the problem.

Prostitution of children in the form of survival sex occurs in both undeveloped and developed countries. In Asia, underage girls sometimes work in brothels to support their families. In Sri Lanka, parents will more often have their sons prostitute themselves rather than their daughters, as the society places more weight on sexual purity among females than males. Jaffe and Rosen write that prostitution of children in North America often results from "economic considerations, domestic violence and abuse, family disintegration and drug addiction". In Canada, a young man was convicted of charges relating to the prostitution of a 15-year-old girl online in 2012; he had encouraged her to prostitute herself as a means of making money, kept all of her earnings, and threatened her with violence if she did not continue.

Consequences

Treatment of prostituted children

Prostituted children are often forced to work in hazardous environments without proper hygiene. They face threats of violence and are sometimes raped and beaten. Researchers Robin E. Clark, Judith Freeman Clark, and Christine A. Adamec write that they "suffer a great deal of abuse, unhappiness, and poor health" in general. For example, Derrick Jensen reports that female sex trafficking victims from Nepal are "'broken in' through a process of rapes and beatings, and then rented out up to thirty-five times per night for one to two dollars per man". Another example involved mostly Nepalese boys who were lured to India and sold to brothels in Mumbai, Hyderabad, New Delhi, Lucknow, and Gorakhpur. One victim left Nepal at the age of 14 and was sold into slavery, locked up, beaten, starved, and forcibly circumcised. He reported that he was held in a brothel with 40 to 50 other boys, many of whom were castrated, before escaping and returning to Nepal.

Criminologist Ronald Flowers writes that prostitution of children and child pornography are closely linked; up to one in three prostituted children have been involved in pornography, often through films or literature. Runaway teenagers, he states, are frequently used for "porn flicks" and photographs. In addition to pornography, Flowers writes that, "Children caught up in this dual world of sexual exploitation are often victims of sexual assaults, sexual perversions, sexually transmitted diseases, and inescapable memories of sexual misuse and bodies that have been compromised, brutalized, and left forever tarnished."

Physical and psychological effects

According to Humanium, an NGO that opposes the prostitution of children, the practice causes injuries such as "vaginal tearing, physical after-effects of torture, pain, infection, or unwanted pregnancy". As clients seldom take precautions against the spread of HIV, prostituted children face a high risk of contracting the disease, and the majority of them in certain locations contract it. Other sexually transmitted diseases pose a threat as well, such as syphilis and herpes. High levels of tuberculosis have also been found among prostituted children. These illnesses are often fatal.

Former prostituted children often deal with psychological trauma, including depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Other psychological effects include anger, insomnia, sexual and personality confusion, inability to trust adults, and loss of confidence. Drug-related health problems included dental problems, hepatitis B and C, and serious liver and kidney problems. Other medical complications included reproductive problems and injuries from sexual assaults; physical and neurological problems from violent physical attacks; and other general health issues including respiratory problems and joint pains.

Prohibition

Prostitution of children is illegal under international law, and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, Article 34, states, "the State shall protect children from sexual exploitation and abuse, including prostitution and involvement in pornography." The convention was first held in 1989 and has been ratified by 193 countries. In 1990, the United Nations appointed a Special Rapporteur on the sale of children, child prostitution, and child pornography. Over at least the last decade, the international community has increasingly acknowledged the importance of addressing problems posed by the trafficking of children, child prostitution, and child pornography; activities that undermine the rights of children and are frequently linked to organized crime. While the legality of adult prostitution varies between different parts of the world, the prostitution of minors is illegal in most countries, and all countries have some form of restrictions against it.

There is a dispute surrounding what constitutes a prostituted child. International law defines a child as any individual below the age of 18, but a number of countries legally recognize lower ages of consent and adulthood, usually ranging from 13 to 17 years of age. Thus, law enforcement officers are sometimes hesitant to investigate cases because of the differences in age of consent. The laws of some countries do, however, distinguish between prostituted teenagers and prostituted children. For example, the Japanese government defines the category as referring to minors between 13 and 18.

Consequences for offenders vary from country to country. In the People's Republic of China, all forms of prostitution are illegal, but having sexual contact with anyone under the age of 14, regardless of consent, will result in a more serious punishment than raping an adult. In the United States, the legal penalty for participating in the prostitution of children includes five to twenty years in prison. The FBI established "Innocence Lost", a new department working to free children from prostitution, in response to the strong public reaction across the country to the news of Operation Stormy Nights, in which 23 minors were released from forced prostitution.

Prevalence

Prostitution of children exists in every country, though the problem is most severe in South America and Asia. The number of prostituted children is rising in other parts of the world, including North America, Africa, and Europe. Exact statistics are difficult to obtain, but it is estimated that there are around 10 million children involved in prostitution worldwide.

- Note: this is a list of examples; it does not cover every country where child prostitution exists.

| Country/location | Number of children involved in prostitution | Notes | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Worldwide | Up to 10,000,000 | ||

| Australia | 4,000 | ||

| Bangladesh | 10,000 – 29,000 | ||

| Brazil | 250,000 – 500,000 | Brazil is considered to have the worst levels of child sex trafficking after Thailand. | |

| Cambodia | 30,000 | ||

| Chile | 3,700 | The number of children involved in prostitution is believed to be on the decline. | |

| Colombia | 35,000 | Between 5,000 and 10,000 are on the streets of Bogotá. | |

| Dominican Republic | 30,000 | ||

| Ecuador | 5,200 | ||

| Estonia | 1,200 | ||

| Greece | 2,900 | Over 200 are believed to be below the age of 12. | |

| Hungary | 500 | ||

| India | 1,200,000 | In India, children account for 40% of people engaged in prostitution. | |

| Indonesia | 40,000 – 70,000 | UNICEF states that 30% of the females in prostitution are below 18. | |

| Malaysia | 43,000 – 142,000 | ||

| Mexico | 16,000 – 20,000 | Out of Mexico City’s 13,000 street children, 95% have already had at least one sexual encounter with an adult (many of them through prostitution). Main article: Child prostitution in Mexico | |

| Nepal | 200,000 | ||

| New Zealand | 210 | ||

| Peru | 500,000 | ||

| Philippines | 60,000 – 100,000 | ||

| Sri Lanka | 40,000 | UNICEF states that 30% of the females in prostitution are below 18. | |

| Taiwan | 100,000 | ||

| Thailand | 200,000 – 800,000 | Main article: Child prostitution in Thailand | |

| United States | 100,000 | ||

| Zambia | 70,000 |

By 1999, it was reported that in Argentina prostitution of children was increasing at an alarming rate and that the average age was decreasing. The Coalition Against Trafficking in Women (CATW) fact book says Argentina is one of the favored destinations of pedophile sex tourists from Europe and the United States. Argentina's Criminal Code criminalizes the prostitution of minors of eighteen years of age or younger, but it only sanctions those who "promote or facilitate" prostitution, not the client who exploits the minor.

Views

Public perception

Anthropologist Heather Montgomery writes that society has a largely negative perception of prostitution of children, in part because the children are often viewed as having been abandoned or sold by their parents and families. The International Labour Organization includes the prostitution of children in its list of the "worst forms of child labour". At the 1996 World Congress Against the Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children it was called "a crime against humanity", "torture", and "slavery". Virginia Kendall, a district judge and expert on child exploitation and human trafficking, and T. Markus Funk, an attorney and law professor, write that the subject is an emotional one and that there are various perspectives about its prevention:

The topic of proscribing and punishing child exploitation triggers intense emotions. While there is general consensus that child sexual exploitation, whether through the Internet, forced prostitution, the international or domestic trafficking of children for sex, or molestation, is on the rise, observers in the United States and elsewhere find little common ground on the questions of how serious such conduct is, or what, if anything, must be done to address it.

Investigative journalist Julian Sher states that widespread stereotypes about the prostitution of children continued into the 1990s, when the first organized opposition arose and police officers began working to dispel common misconceptions. Criminologist Roger Matthews writes that concerns over pedophilia and child sexual abuse, as well as shifting perceptions of youth, led the public to see a sharp difference between prostitution of children and adult prostitution. While the latter is generally frowned upon, the former is seen as intolerable. Additionally, he states, children are increasingly viewed as "innocent" and "pure" and their prostitution as paramount to slavery. Through the shift in attitude, the public began to see minors involved in the sex trade as victims rather than as perpetrators of a crime, needing rehabilitation rather than punishment.

Opposition

Though campaigns against prostitution of children originated in the 1800s, the first mass protests against the practice occurred in the 1990s in the United States, led largely by ECPAT (End Child Prostitution in Asian Tourism). The group, which historian Junius P. Rodriguez describes as "the most significant of the campaigning groups against child prostitution", originally focused on the issue of children being exploited in Southeast Asia by Western tourists. Women's rights groups and anti-tourism groups joined to protest the practice of sex tourism in Bangkok, Thailand. The opposition to sex tourism was spurred on by an image of a Thai youth in prostitution, published in Time and by the publication of a dictionary in the United Kingdom describing Bangkok as "a place where there are a lot of prostitutes". Cultural anthropologists Susan Dewey and Patty Kelly write that though they were unable to inhibit sex tourism and rates of prostitution of children continued to rise, the groups "galvanized public opinion nationally and internationally" and succeeded in getting the media to cover the topic extensively for the first time. ECPAT later expanded its focus to protest child prostitution globally.

The late 1990s and early 2000s also saw the creation of a number of shelters and rehabilitation programs for prostituted children, and the police began to actively investigate the issue. The National Human Trafficking Resource Center (NHTRC) was later established by the Polaris Project as a national, toll-free hotline, available to answer calls from anywhere in the United States, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, every day of the year. Operated by Polaris Project, the hotline was designed to allow callers to report tips and receive information on human trafficking.

The opposition to prostitution of children and sexual slavery spread to Europe and elsewhere, and organizations pushed for prostituted children to be recognized as victims rather than offenders. The issue remained prominent in the following years, and various campaigns and organizations continued into the 2000s and 2010s.

History

Prostitution of children dates to antiquity. Prepubescent boys were commonly prostituted in brothels in ancient Greece and Rome. According to Ronald Flowers, the "most beautiful and highest born Egyptian maidens were forced into prostitution...and they continued as prostitutes until their first menstruation." Chinese and Indian children were commonly sold by their parents into prostitution. Parents in India sometimes dedicated their female children to the Hindu temples, where they became "devadasis". Traditionally a high status in society, the devadasis were originally tasked with maintaining and cleaning the temples of the Hindu deity to which they were assigned (usually the goddess Renuka) and learning skills such as music and dancing. However, as the system evolved, their role became that of a temple prostitute, and the girls, who were "dedicated" before puberty, were required to prostitute themselves to upper class men. The practice has since been outlawed but still exists.

In Europe, child prostitution flourished until the late 1800s; minors accounted for 50% of individuals involved in prostitution in Paris. A scandal in 19th-century England caused the government there to raise the age of consent. In July 1885, William Thomas Stead, editor of The Pall Mall Gazette, published "The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon", four articles describing an extensive underground sex trafficking ring that reportedly sold children to adults. Stead's reports focused on a 13-year-old girl, Eliza Armstrong, who was sold for £5 (the equivalent of around £500 in 2012), then taken to a midwife to have her virginity verified. The age of consent was raised from 13 to 16 within a week of publication. During this period, the term white slavery came to be used throughout Europe and the United States to describe prostituted children.

See also

References

- ^ Willis, Brian M.; Levy, Barry S. (April 20, 2002). "Child prostitution: global health burden, research needs, and interventions". Lancet. 359 (9315): 1417–22. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08355-1. PMID 11978356.

- ^ Lim 1998, p. 171.

- ^ Jaffe & Rosen 1997, p. 10.

- Lim 1998, p. 170.

- Lim 1998, p. 170-171.

- "C182 – Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, 1999 (No. 182)". International Labour Organization. June 17, 1999. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- Narayan 2005, p. 138.

- "Child Exploitation and Obscenity". United States Department of Justice. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- ^ Rodriguez 2011, p. 187.

- Bagley & King 2004, p. 124.

- Brown 2001, p. 1-3.

- "The Prostitution of Children". U.S. Department of Justice. Retrieved February 17, 2016.

- ^ "Human Trafficking FAQs". United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- "Who are the Victims?". End Human Trafficking Now. 2012. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- "UNODC report on human trafficking exposes modern form of slavery". United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- "About UN.GIFT". Ungift.org. Retrieved 2015-08-18.

- ^ Kendall & Funk 2012, p. 31.

- ^ "Child sex-trafficking study in Bosnia reveals misperceptions". Medical News Today. March 1, 2005. Retrieved September 28, 2013.

- De Chesnay 2013, p. 3.

- De Chesnay 2013, p. 4.

- "Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for: Prostitution of Children". United States Department of Justice. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- ^ Jaffe & Rosen 1997, p. 11.

- Rodriguez 2011, p. 188-189.

- Jaffe & Rosen 1997, p. 26.

- Louise Dickson (May 30, 2012). "Pimp who sold girl, 15, for sex gets three years". Times Colonist. Archived from the original on October 2, 2013. Retrieved September 5, 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Madsen & Strong 2009, p. 293.

- ^ Clark, Freeman Clark & Adamec 2007, p. 68.

- ^ Jensen 2004, p. 41.

- "Former sex worker's tale spurs rescue mission". Gulf Times. Gulf-Times.com. 10 April 2005. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 5 October 2010.

"I spent seven years in hell," says Raju, now 21, trying hard not to cry. Thapa Magar took him to Rani Haveli, a brothel in Mumbai that specialised in male sex workers and sold him for Nepali Rs 85,000. A Muslim man ran the flesh trade there in young boys and girls, most of them lured from Nepal. For two years, Raju was kept locked up, taught to dress as a girl and circumcised. Many of the other boys there were castrated. Beatings and starvation became a part of his life. "There were 40 to 50 boys in the place," a gaunt, brooding Raju recalls. "Most of them were Nepalese."

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Flowers 1998, p. 123.

- Flowers 1998, p. 124.

- ^ "Child Prostitution". Humanium. Retrieved September 28, 2013.

- Du Mont & McGregor, 2004: Edinburgh, Saewye, Thao, & Levitt, 2006; Farley et al., 2003; Hoot et al., 2006; Izugbara, 2005; Nixon et al., 2002; Potter, Martin, & Romans,1999; Pyett & Warr, 1977

- "FBI — Operation Cross Country II". Fbi.gov. Retrieved 2013-07-30.

- Rodriguez 2011, p. 189.

- "Special Rapporteur on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography". United Nations Human Rights. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- Buck, Trevor (2008-05-01). "'International Criminalisation and Child Welfare Protection': the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child". Children & Society. 22 (3): 167–178. doi:10.1111/j.1099-0860.2008.00148.x. ISSN 1099-0860.

- Jaffe & Rosen 1997, p. 9.

- Chan 2004, p. 66.

- Note 19, Article 360, at 187.

- O'Connor et al. 2007, p. 264.

- C.G. Niebank (September 7, 2011). "Human network". Oklahoma Gazette. Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- Jaffe & Rosen 1997, p. 10-11.

- "Link to High Beam Research Site". Highbeam.com. Retrieved September 15, 2012.

- "2008 Human Rights Report: Bangladesh". United States Department of State. Retrieved September 27, 2013.

- "Highway of hell: Brazil's child prostitution scandal". news.com.au. November 26, 2013. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

- Bramham, Daphne (March 23, 2012). "In Cambodia, there's a price on childhood". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved November 30, 2013.

- "Child Prostitution". Children of Cambodia. Retrieved September 27, 2013.

- "Bureau of International Labor Affairs – Chile". Dol.gov. Archived from the original on October 2, 2013. Retrieved September 27, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Soaring child prostitution in Colombia". BBC Online. January 27, 2001. Retrieved September 27, 2013.

- "Worst Forms of Child Labour Data – Dominican Republic". International Labour Organization. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Report". State.gov. March 8, 2006. Retrieved September 15, 2012.

- "Worst Forms of Child Labour Data – Estonia". International Labour Organization. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Worst Forms of Child Labour Data – Greece". International Labour Organization. Archived from the original on October 15, 2013. Retrieved October 12, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Worst Forms of Child Labour Data – Hungary". International Labour Organization. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Official: More than 1M child prostitutes in India". CNN. May 11, 2009. Retrieved September 27, 2013.

- "Indonesia". United States Department of Labor. Archived from the original on October 2, 2013. Retrieved September 27, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Indonesia". HumanTrafficking.org. Archived from the original on September 16, 2013. Retrieved September 27, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Lim 1998, p. 7.

- "16,000 Victims of Child Sexual Exploitation". Ipsnews.net. Archived from the original on March 26, 2012. Retrieved September 15, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Press Release: ECPAT (April 21, 2005). "Under Age Prostitution". Scoop. Retrieved September 15, 2012.

- ^ "Child prostitution becomes global problem, with Russia no exception". Pravda. Pravda.Ru. November 10, 2006. Retrieved September 27, 2013.

- "Factsheet: Child Trafficking in the Philippines" (PDF). UNICEF. Retrieved November 30, 2013.

- "40,000 child prostitutes in Sri Lanka, says Child Rights Group". TamilNet. December 6, 2006. Retrieved September 27, 2013.

- Regehr, Roberts & Wolbert Burgess 2012, p. 230.

- 100,000 Children Are Forced Into Prostitution Each Year

- "Worst Forms of Child Labour Data – Zambia". International Labour Organization. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "ECPAT International, A Step Forward". Gvnet.com. 1999.

- 1 Codigo Penal y Leyes Complementarias, art. 125 bis (6th ed., Editorial Astrea, Buenos Aires, 2007).

- "Children\'s Rights: Argentina | Law Library of Congress". Loc.gov. April 2012. Retrieved 2012-09-15.

- Panter-Brick & Smith 2000, p. 182.

- "The worst forms of child labour". International Labour Organization. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- Cowan & Wilson 2001, p. 86.

- Kendall & Funk 2012, p. 9.

- ^ Sher 2011, p. 35.

- ^ Matthews 2008, p. 17.

- Sher 2011, p. 35-36.

- Matthews 2008, p. 15.

- ^ Rodriguez 2011, p. 190.

- ^ Dewey & Kelly 2011, p. 148.

- "Combating Human Trafficking and Modern-day Slavery". Polaris Project. Retrieved September 28, 2013.

- "National Human Trafficking Resource Center | Polaris Project | Combating Human Trafficking and Modern-day Slavery". Polaris Project. Retrieved September 28, 2013.

- Clark, Freeman Clark & Adamec 2007, p. 68-69.

- ^ Flowers 1994, p. 81.

- Institute of Social Sciences (New Delhi, India) & National Human Rights Commission 2005, p. 504.

- ^ Penn 2003, p. 49.

- Cossins 2000, p. 7.

- Clark, Freeman Clark & Adamec 2007, p. 69.

- Hogenboom, Melissa (November 1, 2013). "Child prostitutes: How the age of consent was raised to 16". BBC News. Retrieved November 30, 2013.

- Fine & Ellis 2011, pp. 83–85.

Bibliography

- Bagley, Christopher; King, Kathleen (2004). Child Sexual Abuse: The Search for Healing. Routledge. ISBN 978-0203392591.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brown, Louise (2001). Sex Slaves: The Trafficking of Women in Asia. Virago Press. ISBN 978-1860499036.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Chan, Jennifer (2004). Gender and Human Rights Politics in Japan: Global Norms and Domestic Networks. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0804750226.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Clark, Robin; Freeman Clark, Judith; Adamec, Christine A. (2007). The Encyclopedia of Child Abuse. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0788146060.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cossins, Anne (2000). Masculinities, Sexualities and Child Sexual Abuse. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 978-9041113559.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cowan, Jane K.; Wilson, Richard J. (2001). Culture and Rights: Anthropological Perspectives. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521797351.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - De Chesnay, Mary (2013). Sex Trafficking: A Clinical Guide for Nurses. Springer Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0826171160.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dewey, Susan; Kelly, Patty (2011). Policing Pleasure: Sex Work, Policy, and the State in Global Perspective. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521797351.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fine, Gary Alan; Ellis, Bill (2011). The Global Grapevine: Why Rumors of Terrorism, Immigration, and Trade Matter. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0814785119.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Flowers, Ronald (1998). The Prostitution of Women and Girls. McFarland. ISBN 978-0786404902.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Flowers, Ronald (1994). The Victimization and Exploitation of Women and Children: A Study of Physical, Mental and Sexual Maltreatment in the United States. McFarland. ISBN 978-0899509785.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Institute of Social Sciences (New Delhi, India); National Human Rights Commission (2005). Trafficking in Women and Children in India. Orient Blackswan. ISBN 978-8125028451.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jaffe, Maureen; Rosen, Sonia (1997). Forced Labor: The Prostitution of Children: Symposium Proceedings. Diane Publishing. ISBN 978-0788146060.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jensen, Derrick (2004). The Culture of Make Believe. Chelsea Green Publishing. ISBN 978-1603581837.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kendall, Virginia M.; Funk, Markus T. (2012). Child Exploitation and Trafficking: Examining the Global Challenges and U.S Responses. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1442209800.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lim, Lin Lean (1998). The Sex Sector: The Economic and Social Bases of Prostitution in Southeast Asia. International Labour Organization. ISBN 978-9221095224.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Madsen, Richard; Strong, Tracy B. (2009). The Many and the One: Religious and Secular Perspectives on Ethical Pluralism in the Modern World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1400825592.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Matthews, Roger (2008). Prostitution, Politics & Policy. Routledge. ISBN 978-0203930878.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Narayan, O.P. (2005). Harnessing Child Development: Children and the culture of human. Gyan Publishing House. ISBN 978-8182053007.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - O'Connor, Vivienne M.; Rausch, Colette; Klemenčič, Goran; Albrecht, Hans-Jörg (2007). Model Codes for Post-conflict Criminal Justice: Model criminal code. US Institute of Peace Press. ISBN 978-1601270122.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Panter-Brick, Catherine; Smith, Malcolm T. (2000). Abandoned Children. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521775557.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Penn, Michael L. (2003). Overcoming Violence Against Women and Girls: The International Campaign to Eradicate a Worldwide Problem. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0742525009.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Regehr, Cheryl; Roberts, Albert R.; Wolbert Burgess, Ann (2012). Victimology: Theories and Applications. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 978-1449665333.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rodriguez, Junius P. (2011). Slavery in the Modern World: A History of Political, Social, and Economic Oppression. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1851097883.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sher, Julian (2011). Somebody's Daughter: The Hidden Story of America's Prostituted Children and the Battle to Save Them. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1569768334.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Whetsell-Mitchell, Juliann (1995). Rape of the Innocent: Understanding and Preventing Child Sexual Abuse. Taylor and Francis. ISBN 978-1560323945.

External links

| Sexual ethics | |

|---|---|

| Human sexuality | |

| Child sexuality | |

| Sexual abuse | |

| Age of consent (reform) | |