| Revision as of 05:18, 13 January 2005 editWojciechSwiderski~enwiki (talk | contribs)175 editsm link to pl← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 09:09, 19 August 2024 edit undoWuerzele (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users39,771 edits create subsection modern account | ||

| (154 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Battle of the Second Samnite War (321 BC)}} | |||

| {{Infobox_Battles| | |||

| {{more citations needed|date=June 2021}} | |||

| colour_scheme=background:#cccccc| | |||

| {{Infobox military conflict| | |||

| battle_before=]| | |||

| image= Battle of the Caudine Forks.jpg | | |||

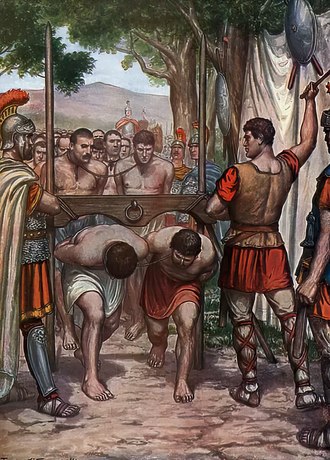

| caption= A Lucanian painting (fresco) of the Battle of the Caudine Forks. | | |||

| image=|caption=| | |||

| conflict= Battle of Caudine Forks| | |||

| partof= the ]| | |||

| date= |

date= 321 BC| | ||

| place=]| | place= ] (near ])| | ||

| result= |

result= Samnite victory| | ||

| combatant1=]| | combatant1= ]| | ||

| combatant2=]| | combatant2= ]| | ||

| commander1= ] <br>]| | |||

| commander1=]| | |||

| commander2= |

commander2= ]| | ||

| strength1=Unknown| | strength1= Unknown| | ||

| map_type=Italy| | |||

| ⚫ | strength2=Unknown| | ||

| map_relief=1| | |||

| ⚫ | casualties1= |

||

| coordinates={{Coord|41.1500|N|14.5333|E|source:wikidata|display=ti}}| | |||

| ⚫ | casualties2= |

||

| ⚫ | strength2= Unknown| | ||

| ⚫ | casualties1= None| | ||

| ⚫ | casualties2= None| | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{Campaignbox Samnite Wars}} | |||

| The '''Battle of Caudine Forks''', ], was a decisive ] of the ]. | |||

| The '''Battle of Caudine Forks''', 321 BC, was a decisive event of the ]. Its designation as a ] is a mere historical formality: there was no fighting and there were no casualties. The Romans were trapped in an enclosed valley by the ] before they knew what was happening and nothing remained but to negotiate an unfavorable surrender. The action was entirely political, with the magistrates on both sides trying to obtain the best terms for their side without disrespecting common beliefs concerning the rules of war and the conduct of peace. In the end the Samnites decided it would be better for future relations to let the Romans go, while the Romans were impeded in the prosecution of their campaign against the Samnites by considerations of religion and honor. | |||

| == |

== Description == | ||

| According to ]'s account, the Samnite commander, ], hearing that the Roman army was located near ], sent ten soldiers disguised as herdsmen with orders to give the same story, which was that the Samnites were besieging ] in ]. The Roman commanders, completely taken in by this ruse, decided to set off to give aid to Lucera. Worse, they chose the quicker route, along a road later to become the ], through the Caudine Forks (''Furculae Caudinae''), a narrow mountain pass near ], ]. The area round the Caudine Forks was surrounded by mountains and could be entered only by two ]s. The Romans entered by one; but when they reached the second defile they found it barricaded. They returned at once to the first defile only to find it now securely held by the Samnites. At this point the Romans, according to ], fell into total despair, knowing the situation was quite hopeless.<ref name="livy"> 2-6</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ⚫ | The Samnites had no idea what to do to take advantage of their success. Hence Pontius was persuaded to send a letter to his father, Herennius. The reply came back that the Romans should be sent on their way, unharmed, as quickly as possible. This advice was rejected, and a further letter was sent to Herennius. This time the advice was to kill the Romans down to the last man. | ||

| ⚫ | Not knowing what to make of such contradictory advice, the Samnites then asked Herennius to come in person to explain. When Herennius arrived he explained that were they to set the Romans free without harm, they would gain the Romans' friendship. If they killed the entire Roman army, then Rome would be so weakened that they would not pose a threat for many generations. At this his son asked was there not a middle way. Herennius insisted that any middle way would be utter folly and would leave the Romans smarting for revenge without weakening them. | ||

| ==The Samnite's Dilema== | |||

| ==Modern account== | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| Modern historians have cast doubt on the details of Livy's account.<ref name =hors>Horsfall, Nicholas (1982) . ''Papers of the British School at Rome'', Vol. 50 (1982), pp. 45-52.</ref> Neither defile leading to the central plain is as narrow and steep as Livy's dramatic description would suggest. The western defile (near the town of ]) is over a kilometre wide, and it is unlikely that the Samnites would have had time to block it effectively in the brief time the Romans would have taken to cross the plain to the eastern defile (near ]) and return. (The distance is 4.5 km, or just under 3 miles.) Even the eastern end, which is narrower, is wide enough to make it possible to march through while keeping out of range of missiles thrown from the hills on either side. Horsfall suggests that Livy's geography may have been influenced by accounts of the campaigns of ] which were contemporary with this event.<ref name =hors/> | |||

| ⚫ | == Aftermath == | ||

| ⚫ | Not knowing what to make of such contradictory advice the Samnites then asked Herennius to come in person to explain. When Herennius arrived he explained that were they to set the Romans free without harm, they would gain the |

||

| ] by the Samnites (Pseudo-Melioli, c. 1500)]] | |||

| ⚫ | According to Livy, Pontius was unwilling to take the advice of his father and insisted that the Romans surrender and pass under a yoke. This was agreed to by the two commanding consuls, as the army was facing starvation. Livy describes in detail the humiliation of the Romans, which serves to underline the wisdom of Herennius's advice. | ||

| Livy contradicts himself as to whether Rome honored or quickly repudiated the Caudine Peace. Livy claims the Roman Senate rejected the terms but, elsewhere, claims Rome honored the Caudine Peace until hostilities broke out afresh in 316.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Salmon |first=Edward Togo |title=Samnium and the Samnites |date=1967 |publisher=Cambridge Univ. Press |isbn=978-0-521-06185-8 |edition=Digitally printed version |location=Cambridge}}</ref>{{rp|228}} | |||

| ⚫ | == |

||

| ⚫ | According to Livy, Pontius |

||

| ⚫ | == References == | ||

| However, Livy's account remains, even if only as a parable, a powerful illustration that the middle course is not always the best. For example Erich Eyck in "A history of the Weimar Republic" uses this example to emphasize the folly of the Entente powers who having defeated Germany in the ] humiliated Germany so opening the way to the rise to power of Hitler without significantly weakening her. | |||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| == |

==Further reading== | ||

| * Rosenstein, Nathan S. ''Imperatores Victi: Military Defeat and Aristocratic Competition in the Middle and Late Republic.'' Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft967nb61p/ | |||

| * | |||

| * Hammond, N.G.L. & Scullard, H.H. (Eds.) (1970).'' The Oxford Classical Dictionary'' (p. 217). Oxford: Oxford University Press. {{ISBN|0-19-869117-3}}. | |||

| ⚫ | ==References== | ||

| * ] | |||

| == External links == | |||

| ] | |||

| {{EB1911 poster|Caudine Forks}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Caudine Forks, Battle of the}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 09:09, 19 August 2024

Battle of the Second Samnite War (321 BC)| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Battle of the Caudine Forks" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (June 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Battle of Caudine Forks | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Samnite War | |||||||

A Lucanian painting (fresco) of the Battle of the Caudine Forks. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Roman Republic | Samnium | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Titus Veturius Calvinus Spurius Postumius Albinus | Gaius Pontius | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| None | None | ||||||

| |||||||

| Samnite Wars | |

|---|---|

| First Samnite War

Second Samnite War Third Samnite War |

The Battle of Caudine Forks, 321 BC, was a decisive event of the Second Samnite War. Its designation as a battle is a mere historical formality: there was no fighting and there were no casualties. The Romans were trapped in an enclosed valley by the Samnites before they knew what was happening and nothing remained but to negotiate an unfavorable surrender. The action was entirely political, with the magistrates on both sides trying to obtain the best terms for their side without disrespecting common beliefs concerning the rules of war and the conduct of peace. In the end the Samnites decided it would be better for future relations to let the Romans go, while the Romans were impeded in the prosecution of their campaign against the Samnites by considerations of religion and honor.

Description

According to Livy's account, the Samnite commander, Gaius Pontius, hearing that the Roman army was located near Calatia, sent ten soldiers disguised as herdsmen with orders to give the same story, which was that the Samnites were besieging Lucera in Apulia. The Roman commanders, completely taken in by this ruse, decided to set off to give aid to Lucera. Worse, they chose the quicker route, along a road later to become the Appian Way, through the Caudine Forks (Furculae Caudinae), a narrow mountain pass near Benevento, Campania. The area round the Caudine Forks was surrounded by mountains and could be entered only by two defiles. The Romans entered by one; but when they reached the second defile they found it barricaded. They returned at once to the first defile only to find it now securely held by the Samnites. At this point the Romans, according to Livy, fell into total despair, knowing the situation was quite hopeless.

The Samnites had no idea what to do to take advantage of their success. Hence Pontius was persuaded to send a letter to his father, Herennius. The reply came back that the Romans should be sent on their way, unharmed, as quickly as possible. This advice was rejected, and a further letter was sent to Herennius. This time the advice was to kill the Romans down to the last man.

Not knowing what to make of such contradictory advice, the Samnites then asked Herennius to come in person to explain. When Herennius arrived he explained that were they to set the Romans free without harm, they would gain the Romans' friendship. If they killed the entire Roman army, then Rome would be so weakened that they would not pose a threat for many generations. At this his son asked was there not a middle way. Herennius insisted that any middle way would be utter folly and would leave the Romans smarting for revenge without weakening them.

Modern account

Modern historians have cast doubt on the details of Livy's account. Neither defile leading to the central plain is as narrow and steep as Livy's dramatic description would suggest. The western defile (near the town of Arienzo) is over a kilometre wide, and it is unlikely that the Samnites would have had time to block it effectively in the brief time the Romans would have taken to cross the plain to the eastern defile (near Arpaia) and return. (The distance is 4.5 km, or just under 3 miles.) Even the eastern end, which is narrower, is wide enough to make it possible to march through while keeping out of range of missiles thrown from the hills on either side. Horsfall suggests that Livy's geography may have been influenced by accounts of the campaigns of Alexander the Great which were contemporary with this event.

Aftermath

According to Livy, Pontius was unwilling to take the advice of his father and insisted that the Romans surrender and pass under a yoke. This was agreed to by the two commanding consuls, as the army was facing starvation. Livy describes in detail the humiliation of the Romans, which serves to underline the wisdom of Herennius's advice.

Livy contradicts himself as to whether Rome honored or quickly repudiated the Caudine Peace. Livy claims the Roman Senate rejected the terms but, elsewhere, claims Rome honored the Caudine Peace until hostilities broke out afresh in 316.

References

- Livy's Book 9, which includes his account of the battle 2-6

- ^ Horsfall, Nicholas (1982) "The Caudine Forks: Topography and Illusion". Papers of the British School at Rome, Vol. 50 (1982), pp. 45-52.

- Salmon, Edward Togo (1967). Samnium and the Samnites (Digitally printed version ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-521-06185-8.

Further reading

- Rosenstein, Nathan S. Imperatores Victi: Military Defeat and Aristocratic Competition in the Middle and Late Republic. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft967nb61p/

- Hammond, N.G.L. & Scullard, H.H. (Eds.) (1970). The Oxford Classical Dictionary (p. 217). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-869117-3.

External links