| Revision as of 21:19, 24 July 2021 editWikiman2021language (talk | contribs)105 editsNo edit summaryTag: Reverted← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 19:01, 22 December 2024 edit undoDaryanazad (talk | contribs)1 editm داریانTags: Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit | ||

| (242 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description| |

{{Short description|Predominant calligraphic hand of the Perso-Arabic script}} | ||

| {{Hatnote|The Nastaliq text on this page will show in a different style if you do not have a Nastaliq font installed.{{ |

{{Hatnote|The Nastaliq text on this page will show in a different style if you do not have a Nastaliq font installed.}} | ||

| {{Italic title}} | |||

| {{Infobox writing system | {{Infobox writing system | ||

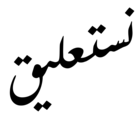

| | name = Nastaliq | | name = Nastaliq | ||

| | type = ] | | type = ] | ||

| | languages = ]<br />]<br />]<br />]<br />] | |||

| | languages = ], ] (including ] and ]), ], ], ] (in Iran and Iraq), many ] (including ] and ]), ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ]{{dn|date=July 2021}}, ], ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| | |

| time = 14th century AD – present | ||

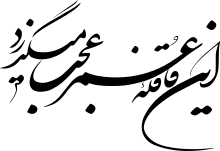

| | native_name = {{nq|نَسْتَعْلِیق}} | |||

| | caption = "Welcome to Misplaced Pages" in Persian<br/>from ] | |||

| | sample = Welcome to Misplaced Pages - fa.svg | |||

| | imagesize = 200px | |||

| | caption = "Welcome to Misplaced Pages" in Persian<br/>from ]<br/><span style="line-height:2.5;">(In print: {{Nastaliq|به ویکیپدیا خوش آمدید}})</span> | |||

| | iso15924 = Aran | |||

| | |

| imagesize = 200px | ||

| | iso15924 = Aran | |||

| | direction = ]<ref>{{Cite conference|last1=Akram|first1=Qurat ul Ain|last2=Hussain|first2=Sarmad|last3=Niazi|first3=Aneeta|last4=Anjum|first4=Umair|last5=Irfan|first5=Faheem|date=April 2014|title=Adapting Tesseract for Complex Scripts: An Example for Urdu Nastalique|url=https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6830996|conference=11th IAPR International Workshop on Document Analysis Systems|location=Tours, France|publisher=IEEE|volume=|pages=191–195|doi=10.1109/DAS.2014.45|isbn=978-1-4799-3243-6|via=}}</ref> | |||

| | note = none | |||

| | direction = ]<ref>{{Cite conference|last1=Akram|first1=Qurat ul Ain|last2=Hussain|first2=Sarmad|last3=Niazi|first3=Aneeta|last4=Anjum|first4=Umair|last5=Irfan|first5=Faheem|title=2014 11th IAPR International Workshop on Document Analysis Systems|date=April 2014|chapter=Adapting Tesseract for Complex Scripts: An Example for Urdu Nastalique|chapter-url=https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6830996|conference=11th IAPR International Workshop on Document Analysis Systems|location=Tours, France|publisher=IEEE|volume=|pages=191–195|doi=10.1109/DAS.2014.45|isbn=978-1-4799-3243-6}}</ref> | |||

| | region = Commonly used in ], ], ] and ]<br>Historically used in ], ], ], ] and ] | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{Calligraphy}} | {{Calligraphy}} | ||

| [[File:Khatt-e Nastaliq.jpg|thumb|right| | |||

| Example reading {{lang|fa|{{nq|"خط نڛتعليق"}}}} ("Nastaliq script") in Nastaliq. | |||

| <br/>The dotted form <big>{{Script/Arabic|ڛ}}</big> is used in place of <big>{{Script/Arabic|س}}</big>.]] | |||

| '''''Nastaliq''''' ({{IPAc-en|ˌ|n|æ|s|t|ə|ˈ|l|iː|k|,_|ˈ|n|æ|s|t|ə|l|iː|k}};<ref>{{Cite web|title=Nastaliq|url=https://www.lexico.com/definition/nastaliq|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220328182321/https://www.lexico.com/definition/nastaliq|url-status=dead|archive-date=March 28, 2022|access-date=2020-07-05|website=Lexico Dictionaries|publisher=]|language=en}}</ref> , {{IPA|fa|næstʰæʔliːq|lang}}; {{IPA-ur|nəst̪ɑːliːq|lang}}), also ] as '''''Nastaʿlīq''''' or '''''Nastaleeq''''', is one of the main ] used to write the ] and it is used for some ], predominantly ], ], ] and ]. It is often used also for ] poetry, but rarely for ]. ''Nastaliq'' developed in ] from '']'' beginning in the 13th century{{sfn|Blair|p=xxii, 286}}<ref name="Iranica">{{Cite web |author=Gholam-Hosayn Yusofi |date=December 15, 1990 |title=Calligraphy |url=https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/calligraphy |website=] |language=en}}</ref> and remains widely used in ], ], Afghanistan, ], and other countries for written poetry and as a form of art.<ref>{{Cite journal|author1=Atif Gulzar|author2=Shafiq ur Rahman|date=2007|title=Nastaleeq: A challenge accepted by Omega|url=https://www.tug.org/TUGboat/tb29-1/tb91gulzar.pdf|journal=TUGboat|volume=29|pages=1–6}}</ref> | |||

| [[File:Hafez Ghazal.jpg|thumb|right| | |||

| A ] versified by the Persian poet ] in Nastaliq, in print: <sup>]]</sup> | |||

| {{rtl-para|1=fa|2={{nq| | |||

| حافظ شیرازی<br/> | |||

| مرا عهدیست با جانان که تا جان در بدن دارم<br/> | |||

| هواداران کویش را چو جان خویشتن دارم | |||

| |size=1.25em}}}} | |||

| in a ] styled typeface: | |||

| {{rtl-para|1=fa|2={{naskh| | |||

| حافظ شیرازی<br/> | |||

| مرا عهدیست با جانان که تا جان در بدن دارم<br/> | |||

| هواداران کویش را چو جان خویشتن دارم | |||

| }}}}]] | |||

| '''Nastaʼlīq''' ({{IPAc-en|ˌ|n|æ|s|t|ə|ˈ|l|iː|k|,_|ˈ|n|æ|s|t|ə|l|iː|k}};<ref>{{Cite web|title=Nastaliq {{!}} Definition of Nastaliq by Oxford Dictionary on Lexico.com also meaning of Nastaliq|url=https://www.lexico.com/definition/nastaliq|access-date=2020-07-05|website=Lexico Dictionaries|publisher=]|language=en|via=Lexico.com}}</ref> {{lang-fa|{{nq|نستعلیق}}}}, {{IPA-fa|næsˈtæʔliːq|IPA}}) is one of the main ]s used to write the ] in the ] and ] languages,<ref>{{Cite web|last=eteraz|first=ali|date=8 October 2013|title=The Death of the Urdu Script|url=https://medium.com/@eteraz/the-death-of-the-urdu-script-9ce935435d90|access-date=4 June 2020|website=Medium|language=en|quote=Urdu is traditionally written in a Perso-Arabic script called nastaliq…}}</ref> and traditionally the predominant style in ].<ref>''The Cambridge History of Islam''. By P. M. Holt, et al., Cambridge University Press, 1977, {{ISBN|0-521-29138-0}}, p. 723.</ref> It was developed in the land of Persia (modern-day ]) in the 14th and 15th centuries.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.persiancalligraphy.org/Famous-Calligraphers.html|title=Famous Calligraphers - Persian Calligraphy- All about Persian Calligraphy|first=Payman|last=Hamed|website=www.persiancalligraphy.org}}</ref> It is sometimes used to write ] language text (where it is mainly used for titles and headings), but its use has always been more popular in the ], ] and ] sphere of influence.{{Citation needed|date=January 2020|reason=which Turkic languages?}} Nastaliq remains very widely used in ], ] and ] and other countries for written poetry and as a form of art.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Gulzar, Rahman|first=Atif, Shafiq|date=2007|title=Nastaleeq: A challenge accepted by Omega|url=https://www.tug.org/TUGboat/tb29-1/tb91gulzar.pdf|journal=TUGboat|volume=29|pages=1–6}}</ref> | |||

| A less elaborate version of Nastaliq serves as the preferred style for writing in ] and ] and it is often used alongside ] for ].{{Citation needed|date=January 2020|reason=elsewhere some contributors have questioned whether it's used for Pashto at all}} In ], it is used for poetry only. {{transl|fa|Nastaliq}} was historically used for writing ], where it was known as {{lang|ota-Latn|tâlik}}<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.zakariya.net/history/scripts.html |title=The Scripts |access-date=2013-12-10 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131214094318/http://www.zakariya.net/history/scripts.html |archive-date=2013-12-14 |url-status=dead }}</ref> (not to be confused with a totally different Persian style, also called '']''; to distinguish the two, Ottomans referred to the latter as {{transl|ota|taʿlīq-i qadim}}, "old {{transl|ota|taʿlīq}}"). | |||

| Nastaliq is the core script of the post-] Persian writing tradition and is equally important in the areas under its cultural influence. The ] (Western Persian, Azeri, Balochi, Kurdi, Luri, etc.), ] (Dari Persian, Pashto, Turkmen, Uzbek, etc.), ] (Urdu, Kashmiri, etc.), ] (Urdu, Punjabi, Saraiki, Pashto, Balochi, etc.) and the Turkic ] of the Chinese province of ], rely on {{transl|fa|Nastaliq}}. Under the name {{transl|ota|]}} (lit. "suspending script"), it was also beloved by Ottoman calligraphers who developed the ] ({{transl|ota|divanî}}) and ] ({{transl|ota|rık{{okina}}a}}) styles from it.{{Citation needed|reason=there is no reference / citation given for these statements |date=June 2017}} | |||

| {{transl|fa|Nastaliq}} is amongst the most fluid calligraphy styles for the ]. It has short verticals with no serifs, and long horizontal strokes.{{Citation needed|date=January 2020|reason=I don't see any "long horizontal strokes"}} It is written using a piece of trimmed reed with a tip of {{convert|5|–|10|mm|in|1|abbr=on}}, called {{transl|ar|]}} ('pen', ] and ] {{lang|ar|قلم}}) and carbon ink, named ''siyahi''. The nib of a {{transl|ar|qalam}} can be split in the middle to facilitate ] absorption.<ref>{{Citation|title=Qalam|date=2020-02-15|url=https://en.wikipedia.org/search/?title=Qalam&oldid=940890427|work=Misplaced Pages|language=en|access-date=2020-03-29}}</ref> | |||

| Two important forms of {{transl|fa|Nastaliq}} panels are {{transl|fa|]}} and {{transl|fa|]}}. A {{transl|fa|Chalipa}} ("cross", in Persian) panel usually consists of four diagonal hemistiches (half-lines) of poetry, clearly signifying a moral, ethical or poetic concept. {{transl|fa|Siyah Mashq}} ("black drill") panels, however, communicate via composition and form, rather than content. In {{transl|fa|Siyah Mashq}}, repeating a few letters or words (sometimes even one) virtually inks the whole panel.{{Citation needed|reason=should that say "links" instead of "inks"?|date=January 2020}} The content is thus of less significance and not clearly accessible.{{Citation needed|reason=there is no reference / citation given for these statements.|date=June 2017}} | |||

| == History == | == History == | ||

| The name ''Nastaliq'' "is a contraction of the Persian {{transliteration|fa|naskh-i ta'liq}} ({{langx|fa|{{nq|نَسْخِ تَعلیق}}}}), meaning a hanging or suspended '']''"{{sfn|Blair|p=274}} Virtually all ] authors (like ] or ]) attributed the invention of {{transliteration|fa|nastaliq}} to ], who lived at the end of the 14th and the beginning of the 15th century. That tradition was questioned by Elaine Wright, who traced the evolution of ''Nastaliq'' in 14th-century Iran and showed how it developed gradually among scribes in ]. According to her studies, ''nastaliq'' has its origin from ''naskh'' alone, and not by combining ''naskh'' and '']'', as was commonly thought. In addition to study of the practice of calligraphy, Elaine Wright also found a document written by ] {{Circa|1430}}, according to whom: | |||

| [[File:Khatt-e Nastaliq.jpg|thumb|right| | |||

| Example saying, "''Nastaliq script''", written in {{transl|fa|Nasta'līq}}. | |||

| {{rtl-para|1=fa|2={{nq|خط نستعلیق|size=1.5em}}}} | |||

| (]: {{lang|fa|خط نستعلیق}}) | |||

| <br/>The dotted form <big>{{lang|fa|]}}</big> is used in place of <big>{{lang|fa|]}}</big> in the word <big>{{lang|fa|نڛتعلیق}}</big> Nastaliq.]] | |||

| {{blockquote|It must be known that ''nastaʿliq'' is derived from ''naskh''. Some Shirazi modified it by taking out the flattened ''kaf'' and straight bottom part of ''sin'', ''lam'' and ''nun''. From other scripts they then brought in a curved ''sin'' and stretched forms and introduced variations in the thickness of the line. So a new script was created, to be named ''nastaʿliq''. After a while ]i modified what Shirazi had created by gradually rendering it thinner and defining its canons, until the time when Khwaja Mir ʿAli Tabrizi brought this script to perfection.{{sfn|Blair|p=275}}}} | |||

| After the ], the Iranian Persian people adopted the ] and the art of ] flourished in Iran as territories of the former Persian empire. Apparently, ] (14th century) developed {{transl|fa|Nastaliq}} by combining two existing scripts of {{transl|fa|]}} and {{transl|fa|]}}.<ref>{{cite web |title=Famous Calligraphers |url=http://www.persiancalligraphy.org/Famous-Calligraphers.html |work=Persian Calligraphy |access-date=12 January 2012 }}</ref> Hence, it was originally called {{transl|fa|Nasḫ-Taʿlīq}}. Another theory holds that the name {{transl|fa|Nastaliq}} means "that which abrogated (''naskh'') ''Taʿlīq''".<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.irangazette.com/en/12/494-iran-nasta%CA%BFl%C4%ABq-script.html|title=Iran Nastaʿlīq script - IRAN TRAVEL, TRIP TO IRAN|website=www.irangazette.com|access-date=2020-03-29}}</ref> | |||

| Thus, "our earliest written source also credits Shirazi scribes with the development of ''nastaʿliq'' and Mir ʿAli Tabrizi with its canonization."{{sfn|Blair|p=275}} The picture of origin of ''nastaliq'' presented by Elaine Wright was further complicated by studies of Francis Richard, who on the basis of some manuscripts from Tabriz argued that its early evolution was not confined to Shiraz.{{sfn|Blair|p=275}} Finally, many authors point out that development of ''nastaʿliq'' was a process which takes a few centuries. For example, Gholam-Hosayn Yusofi, Ali Alparslan and ] recognize gradual shift towards ''nastaʿliq'' in some 13th-century manuscripts.<ref name="Iranica"/><ref>{{Cite journal|url = http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0502|title = K̲h̲aṭṭ ii. In Persia|author = ]|website = ]|doi = 10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0502|language = en}}</ref>{{sfn|Blair|p=xxii}} Hamid Reza Afsari traces first elements of the style in 11th-century copies of Persian translations of the Qur'an.<ref name="Hamid Reza Afsari">{{Cite web|url = https://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopaedia-islamica/calligraphy-COM_05000067?s.num=3|title = Calligraphy|author = Hamid Reza Afsari|website = ]|date = 17 June 2021|language = en}}</ref> | |||

| {{transl|fa|Nastaliq}} thrived and many prominent calligraphers contributed to its splendor and beauty. It is believed{{By whom|date=July 2010}} that {{transl|fa|Nastaliq}} reached its highest elegance in ]'s works. The current practice of {{transl|fa|Nastaliq}} is, however, heavily based on ]'s technique. Kalhor modified and adapted {{transl|fa|Nastaliq}} to be easily used with printing machines, which in turn helped wide dissemination of his transcripts. He also devised methods for teaching {{transl|fa|Nastaliq}} and specified clear proportional rules for it, which many could follow.{{Citation needed|reason=there is no reference / citation given for these statements |date=June 2017}} | |||

| Persian differs from Arabic in its proportion of straight and curved letters. It also lacks the definite article ''al-'', whose upright ''alif'' and ''lam'' are responsible for distinct verticality and rhythm of the text written in Arabic. Hanging scripts like ''taliq'' and ''nastaliq'' were suitable for writing Persian – when ''taliq'' was used for court documents, ''nastaliq'' was developed for Persian poetry, "whose ]es encourage the pile-up of letters against the intercolumnar ruling. Only later was it adopted for prose."{{sfn|Blair|p=276}} | |||

| The ] used ] as the court ] during their rule over ]. During this time, {{transl|fa|Nastaliq}} came into widespread use in ]. The influence continues to this day. In India and Pakistan, almost everything in Urdu is written in the script, constituting the greatest part of {{transl|fa|Nastaliq}} usage in the world. The situation of {{transl|fa|Nastaliq}} in ] used to be the same as in Pakistan until 1971, when Urdu ceased to remain an official language. Today, only a few people use this form of writing in ].{{Citation needed|reason=there is no reference / citation given for these statements |date=June 2017}} | |||

| The first master of ''nastaliq'' was aforementioned ], who passed his style to his son ʿUbaydallah. The student of Ubaydallah, ] (d. 1431) (see quote above), moved to ], when he became the head of the ] (''kitabkhana'') of prince ] (therefore his epithet Baysunghuri). Jafar trained several students in ''nastaliq'', of whom the most famous was ] (d. 1475). Its classical form ''nastaliq'' achieved under ] (d. 1520), a student of Azhar (or perhaps one of Azhar's students) who worked for ] (1469–1506) and his vizier ].{{sfn|Blair|p=277-280}} At the same time a different style of ''nastaliq'' developed in western and southern Iran. It was associated with ʿAbd al-Rahman Khwarazmi, the calligrapher of the ] ] (1456–1466) and after him was followed by his children, ʿAbd al-Karim Khwarazmi and ] (both active at the court of ] ]; 1478–1490). This more angular western Iranian style was largely dominant at the beginning of the ], but then lost to the style canonized by Sultan Ali Mashhadi – although it continued to be used in the Indian subcontinent.<ref name="Hamid Reza Afsari"/>{{sfn|Blair|p=284, 430}} | |||

| Nastaliq is a descendant of {{transl|fa|]}} and {{transl|fa|Taʿlīq}}. {{transl|fa|Shekasteh Nastaliq}} - literally: "broken Nastaliq" - style ] is a development of {{transl|fa|Nastaliq}}.{{Citation needed|reason=there is no reference / citation given for these statements |date=June 2017}} | |||

| The most famous calligrapher of the next generation in eastern lands was ] (d. 1544), who was master of ''nastaliq'', especially renowned for his calligraphic specimens (''qitʿa''). The eastern style of ''nastaliq'' became the predominant style in western Iran, as artists gravitated to work in Safavid royal scriptorium. The most famous of these calligraphers working for the court in Tabriz was Shah Mahmud Nishapuri (d. 1564/1565), known especially for the unusual choice of ''nastaliq'' as a script used for the copy of the Qur'an.{{sfn|Blair|p=430-436}} Its apogeum ''nastaliq'' achieved in writings of ] (d. 1615), "whose style was the model in the following centuries."<ref name="Hamid Reza Afsari"/> Mir Emad's successors in the 17th and 18th centuries had developed a more elongated style of ''nastaliq'', with wider spaces between words. ] (d. 1892), the most important calligrapher of the 19th century, reintroduced the more compact style, writing words on a smaller scale in a single motion. In the 19th century ''nastaliq'' was also adopted in Iran for lithographed books.{{sfn|Blair|p=446-447}} In the 20th century, "the use of ''nastaliq'' declined. After World War II, however, interest in calligraphy and above all in ''nastaliq'' revived, and some outstandingly able masters of the art have since then emerged."<ref name="Iranica"/> | |||

| {{Clear}} | |||

| The use of ''nastaliq'' very early expanded beyond Iran. ] brought it to the ] and ''nastaliq'' became favorite script at the Persian court of the ]. For ] (1556–1605) and ] (1605–1627) worked such famous masters of ''nastaliq'' as ] (d. 1611/1612) and ]. Another important practitioner of the script was ] (d. 1671), nephew and student of Mir Emad, who after his arrival in India became court calligrapher of ] (1628–1658). During this era ''Nastaliq'' became the common script for writing the ], especially ].<ref name="Iranica2">{{Cite web|url = https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/calligraphy-2|title = CALLIGRAPHY (continued)|author = ]|website = ]|language = en}}</ref>{{sfn|Blair|p=536-539, 552-554}} | |||

| == Notable Nastaliq calligraphers == | |||

| ] <br/> | |||

| In print: <sup>]]</sup> | |||

| {{rtl-para|fa|{{Nastaliq|بودم به تو عمری و ترا سیر ندیدم<br/>از وصل تو هرگز به مرادی نرسیدم<br/>از بهر تو بیگانه شدم از همه خویشان<br/>وحشی صفت از خلق به یکبار بریدم|size=1.25em}}}} | |||

| In ] styled typeface: | |||

| {{rtl-para|fa|{{naskh|بودم به تو عمری و ترا سیر ندیدم<br/>از وصل تو هرگز به مرادی نرسیدم<br/>از بهر تو بیگانه شدم از همه خویشان<br/>وحشی صفت از خلق به یکبار بریدم}}}} ]] | |||

| ''Nastaliq'' was also adopted in ], which has always had strong cultural ties to Iran. Here it was known as ''taliq'' (Turkish ''talik''), which should not be confused with Persian '']''. First Iranian calligraphers who brought ''nastaliq'' to Ottoman lands, like ] (d. 1488), belonged to the western tradition. But relatively early Ottoman calligraphers adopted eastern style of ''nastaliq''. In 17th century, student of Mir Emad, ] (d. 1647), transplanted his style to Istanbul. The greatest master of ''nastaliq'' in 18th century was ] (d. 1798), who closely followed Mir Emad. This tradition was further developed by son of Yasari, ] (d. 1849), who was a real founder of distinct Ottoman school of ''nastaliq''. He introduced new and precise proportions of the script, different than in Iranian tradition. The most important member of this school in the second half of the 19th century was ] (d. 1912), who taught many famous practitioners of ''nastaliq'', like ] (d. 1913), ] (d. 1940) and ] (d. 1976). The specialty of Ottoman school was ''celî nastaliq'' used in inscriptions and mosque plates.{{sfn|Blair|p=513-518}}<ref name="Iranica2"/><ref name="NESTA‘LİK">{{Cite web|url = https://islamansiklopedisi.org.tr/nestalik|title = NESTA'LİK|author = ]|website = ]|language = en}}</ref> | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| {{gallery | |||

| And others, including Mirza Jafar Tabrizi, Abdul Rashid Deilami, Sultan Ali Mashadi, Mir Ali Heravi, Emad Ul-Kottab, Mirza Gholam Reza Esfehani, Emadol Kotab, Yaghoot Mostasami and Darvish Abdol Majid Taleghani.{{Citation needed|reason=there is no reference / citation given for these statements |date=June 2017}} | |||

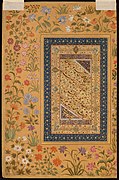

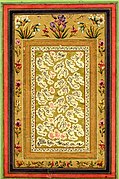

| |Folio from a Khusraw u Shirin by Nizami (d.1209); verso - text and illuminated heading (sarlawh) (F1931.37).jpg|Opening page to a copy of ] '']'' with calligraphy by ]. ], {{Circa|1410}}. ] | |||

| |First Page of the Baysunghur's Gulistan (CBL Per119.10f.1.v).jpg|Opening page from a manuscript of ] '']'' copied by ]. ], 1426/27. ] | |||

| |"Allusion to Sura 27-16", Folio from a Mantiq al-tair (Language of the Birds) MET DP159398.jpg|Page from a manuscript of ] '']'' copied by ]. ], dated 25 April 1487. ] | |||

| |Colophon to Nizami's "Khamsa" written by 'Abd al-Rahim al- Khwarazmi Anisi (TKS H762, f. 316a).jpg|Colophon to Nizami's ''Khamsa'' copied by ]. Tabriz, 1481. ] Museum | |||

| |"Portrait of Ibrahim 'Adil Shah II of Bijapur", Folio from the Shah Jahan Album MET DT2792.jpg|] copied by ] and later mounted in the so-called "Kevorkian Album". ], {{Circa|1534}}. Metropolitan Museum of Art | |||

| |Opening double page from the Qur'an in nasta'liq script (TKS H.S. 25, ff. 1b-2a).jpg|Opening double page from the Qur'an manuscript copied by ], dated 12 June 1538. Topkapı Palace Museum | |||

| |Nasta'liq calligraphy style - Mir Emad Hassani 09.png|Sura ] copied by ]. ] | |||

| |Colophon from the Khamsa of Nizami - BL Or. MS 12208 f. 325v.jpg|Colophon from a ] of Nizami's ''Khamsa'' copied by ], dated 14 December 1595. ] | |||

| |Amir Khusraw Dihlavi - Incipit Page with Illuminated Headpiece - Walters W6241B - Full Page.jpg|Page from a manuscript of ]'s ''Khamsa'' copied by ] and finished in the forty-second year of ]'s reign (March 1597 – March 1598). ] | |||

| |Calligrapher’s license with a quatrain copied by Muhammad Asʿad Yasari (TKS GY 324.27-3).jpg|Calligrapher's license with a rubaʿi copied by ] from an exemplar by Mir Emad. ], 1754. Topkapı Palace Museum | |||

| |Signed Sami - Levha (calligraphic inscription) - Google Art Project.jpg|''Levha'' (calligraphic inscription) by ]. Istanbul, 1906. ] | |||

| |Containing calligraphies ascribed to Nazif Bey - Murakka (calligraphic album) - Google Art Project.jpg|Page from the '']'' with ]'s ode on the Prophet copied by ] from an original by ]. 20th century (before 1913). Sakıp Sabancı Museum | |||

| }} | |||

| == {{transliteration|fa|Shekasteh}} ''Nastaliq'' == | |||

| And among contemporary artists: Hassan Mirkhani, Hossein Mirkhani, ], Abbas Akhavein and Qolam-Hossein Amirkhani, Ali Akbar Kaveh, | |||

| ] of Omar Khayyam in Shekasteh Nastaliq.<br/>In print:{{rtl-para|fa|{{Nastaliq|1={{raise|0.4em|گویند کسان بهشت با حور خوش است<br/>من میگویم که آب انگور خوش است<br/>این نقد بگیر و دست از آن نسیه بدار<br/>کاواز دهل شنیدن از دور خوش است|size=1.25em}}}}}} In modern ]: {{rtl-para|fa|{{naskh|1={{lower|0.2em|گویند کسان بهشت با حور خوش است<br/>من میگویم که آب انگور خوش است<br/>این نقد بگیر و دست از آن نسیه بدار<br/>کاواز دهل شنیدن از دور خوش است}}}}}}]] | |||

| Kaboli.<ref> {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100928182912/http://www.wegoiran.com/iran-information/iran-culture/nastaliq-script-persian-calligraphy.htm |date=September 28, 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| ] in Shekasteh Nastaliq.<br/>In print: {{rtl-para|fa|{{nastaliq|1={{raise|0.4em|این قافلهٔ عُمر عجب میگذرد|size=1.25em}}}}}} In modern ]: {{rtl-para|fa|{{naskh|1={{lower|0.2em|2=<span style="line-height: 1.5;">این قافلهٔ عُمر عجب میگذرد</span>}}}}}}]] | |||

| ''{{transliteration|fa|Shekasteh}}'' or ''{{transliteration|fa|Shekasteh Nastaliq}}'' ({{langx|fa|{{Nastaliq|شکسته نستعلیق}}}}, {{lang|fa|{{uninaskh|شکسته نستعلیق}}}}, "cursive {{transliteration|fa|Nastaliq}}" or literally "broken {{transliteration|fa|Nastaliq}}") style is a "streamlined" form of {{transliteration|fa|Nastaliq}}.<ref name="readnast3">{{Cite book |last1=Spooner |first1=Brian |title=Reading Nasta'liq: Persian and Urdu Hands from 1500 to the Present |last2=Hanaway |first2=William L. |year=1995 |isbn=978-1568592138 |pages=3}}</ref> Its development is connected with the fact that "the increasing use of nastaʿlīq and consequent need to write it quickly exposed it to a process of gradual attrition."<ref name="Iranica"/> The ''shekasteh nastaliq'' emerged in the early 17th century and differed from proper ''nastaliq'' only in so far as some of the letters were shrunk (shekasteh, lit. "broken") and detached letters and words were sometimes joined.<ref name="Iranica"/> These unauthorized connections "mean that calligraphers can write ''shekasteh'' faster than any other script."{{sfn|Blair|p=441}} Manuscripts from this early period show signs of the influence of ''shekasteh taliq''; while having the appearance of a shrunken form of nastaliq, they also contain features of '']'' "due to their being written by scribes who had been trained in taʿlīq."<ref name="Iranica"/> ''Shekasteh nastaliq'' (usually shortened to simply ''skehasteh''), being more easily legible than ''taliq'' gradually replaced the latter as the script of decrees and documents. Later, it also came into use for writing prose and poetry.<ref name="Iranica"/>{{sfn|Blair|p=441}} | |||

| The first important calligraphers of ''shekasteh'' were ] (d. 1670–71) (he was known as Shafiʿa and hence ''shekasteh'' was sometimes called ''shafiʿa'' or ''shifiʿa'') and ] (d. 1688–89). Both of them produced works of real artistic quality, which does not change the fact that in this early phase ''shekasteh'' still lacked consistency (it is especially visible in writing of Mortazaqoli Khan Shamlu). Most modern scholars consider that ''shekasteh'' reached its peak of artistic perfection under ] (d. 1771), "who gave the script its distinctive and definite form."<ref name="Iranica"/> The tradition of Taleqani was later followed by ] (d. 1813),{{sfn|Blair|p=444-445}}<ref>{{Cite web|url = https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/abd-al-majid-talaqani-revered-calligrapher-d-1771-72|title = ʿABD-AL-MAJĪD ṬĀLAQĀNĪ|author = ]|website = ]|language = en}}</ref> ] (d. 1886–87)<ref>{{Cite web|url = https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/golam-reza-kosnevis|title = ḠOLĀM-REŻĀ ḴOŠNEVIS|author = Maryam Ekhtiar|website = ]|language = en}}</ref> and ] (d. 1901).<ref>{{Cite web|url = https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/golestana-ali-akba|title = GOLESTĀNA, ʿALI-AKBAR|author = Maryam Ekhtiar|website = ]|language = en}}</ref> | |||

| <gallery widths="200" heights="200"> | |||

| The added frills made ''shekasteh'' increasingly difficult to read and it remained the script of documents and decrees, "while ''nastaʿliq'' retained its pre-eminence as the main calligraphic style." The need for simplification of ''shekasteh'' resulted in development of secretarial style (''shekasteh-ye tahriri'') by writers like ] (d. 1917) and ] (d. 1900). The secretarial style is a simplified form of ''shekasteh'' which is faster to write and read, but less artistic. Long used in governmental and other institutions in Iran, ''shekasteh'' degenerated in the first half of the 20th century, but later again engaged the attention of calligraphers.<ref name="Iranica"/>{{sfn|Blair|p=445, 471}} ''Shekasteh'' was used only in Iran and to a small extent in Afghanistan and Ottoman Empire. Its use in Afghanistan was different from the Persian norm and sometimes only as experimental devices (''tafannon'')<ref name="Iranica"/><ref name="NESTA‘LİK"/> | |||

| File:Mir emad 1012 hijri.jpg|], Safavid era | |||

| {{gallery | |||

| File:Soltan ali mashhadi 895 1489.jpg|Soltan-ali Mashhadi - 1489 AD | |||

| |Shakastah Nasta‘liq calligraphy, National Library of Iran, No. 2313.jpg|Calligraphy by ]. ] | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| |File:Double page from "Majmu‘a-i munsh‘at" by Abu‘l-Qasim Ivughli Haydar (S2014.7).jpg|Double page from the "Majmu‘a-i munsh‘at" – collection of correspondence sent by Persian rulers compiled by Abu‘l-Qasim Ivughli Haydar. ], 1682. ] | |||

| |Calligraphy in Shakastah Nasta‘liq (Library of the Golestan Palace, No. 1515).jpg|Calligraphy by ]. ] Library | |||

| |Plea for Tax Relief, folio from an album (HUAM 1958.212).jpg|Plea for tax relief copied by ]. Iran, 1795–1796. ] | |||

| |Fath Ali Shah Qajar Firman in Shikasta Nastaliq script January 1831.jpg|] issued in the Name of ]. Iran, January 1831. ] | |||

| |Shakastah Nasta‘liq calligraphy, 1896 CE, Library of the Islamic Parliament of Iran, No. 13.jpg|Calligraphy by ]. Iran, 1896. Library of the ] | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Clear}} | {{Clear}} | ||

| == ''Nastaliq'' typesetting == | |||

| == Etiquette == | |||

| Modern {{transliteration|fa|Nastaliq}} typography began with the invention of ''Noori Nastaleeq'' which was first created as a digital font in 1981 through the collaboration of ] (as calligrapher) and ] (formerly Monotype Corp & Monotype Typography).<ref name="Interview with Mirza Ahmad Jamil">{{cite web|last=Khurshiq|first=Iqbal|title=زندگی آگے بڑھنے کا نام اور جمود موت ہے: نوری نستعلیق کی ایجاد سے خط نستعلیق کی دائمی حفاظت ہوگئی|date=17 November 2013|url=http://www.express.pk/story/197175/|publisher=Express|access-date=24 November 2013}}</ref> Although this employed over 20,000 ligatures (individually designed character combinations),<ref>, 9 Feb 2021</ref> it provided accurate results and allowed newspapers such as Pakistan's '']'' to use digital typesetting instead of a group of calligraphers. It suffered from two problems in the 1990s: its non-availability on standard platforms such as ] or ], and the non-] nature of text entry, whereby the document had to be created by commands in Monotype's proprietary ]. | |||

| ] was originally used to adorn Islamic religious texts, specifically the ], as pictorial ornaments were prohibited in sacred publications and spaces of ]. Therefore, a sense of sacredness was always implicit in calligraphy.{{Citation needed|reason=there is no reference / citation given for these statements |date=June 2017}} | |||

| A {{transl|fa|Nastaliq}} disciple was supposed to qualify himself spiritually for being a calligrapher, besides learning how to prepare ''{{transl|ar|qalam}}'', ink, paper and, more importantly, master {{transl|fa|Nastaliq}}. For instance see ''Adab al-Mashq'', a manual of penmanship attributed to ].<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Ernst|first=Carl W.|date=April–June 1992|title=The Spirit of Islamic Calligraphy: Bābā Shāh Iṣfahānī's Ādāb al-mashq|journal=Journal of the American Oriental Society|volume=112|issue=2|pages=279–286|doi=10.2307/603706|jstor=603706}}</ref> | |||

| <gallery> | |||

| File:Sultan 'Ali Mashhadi (Persian, 1442-1519). Folio of Poetry From the Divan of Sultan Husayn Mirza, ca. 1490.jpg|''Folio of Poetry From the Divan of Sultan Husayn Mirza'', ca. 1490. ]. | |||

| File:Quatrain on the Virtue of Patience WDL6844.png|Quatrain on the Virtue of Patience by Muhammad Muhsin Lahuri of the ] | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| {{Gallery | |||

| | title = Examples of Nastaliq typesetting | |||

| | align = center | |||

| | footer = | |||

| | style = | |||

| | state = | |||

| | height = 170 | |||

| | width = 250 | |||

| | captionstyle = | |||

| | File:Miremad-1.jpg | |||

| | Persian Chalipa panel, ]<br/> | |||

| In print:<sup>]]</sup> | |||

| {{rtl-para|fa|{{Nastaliq|1={{raise|1em|بودم به تو عمری و ترا سیر ندیدم<br/>از وصل تو هرگز به مرادی نرسیدم<br/>از بهر تو بیگانه شدم از همه خویشان<br/>وحشی صفت از خلق به یکبار بریدم|size=1.25em}}}}}} | |||

| In ] styled typeface: | |||

| {{rtl-para|fa|{{naskh|1={{lower|0.2em|2=<span style="line-height: 1.3;">بودم به تو عمری و ترا سیر ندیدم<br/>از وصل تو هرگز به مرادی نرسیدم<br/>از بهر تو بیگانه شدم از همه خویشان<br/>وحشی صفت از خلق به یکبار بریدم</span>}}}}}} | |||

| | alt1= | |||

| | File:Urdu couplet.svg | |||

| | An example of the {{transl|fa|Nastaliq}} script used for writing ].<br/>Nastaliq:<br/>{{rtl-para|{{lang|ur|{{nastaliq|size=1.25em|؎ کیا تنگ ہم ستم زدگان کا جہاں ہے<br/>جس میں ایک بیضۂ مور آسماں ہے}}}}}}<br/>Naskh:<br/>{{rtl-para|{{lang|fa|{{naskh|size=1.25em|1={{lower|0.2em|2=<span style="line-height: 1.3;">؎ کیا تنگ ہم ستم زدگان کا جہاں ہے<br/>جس میں ایک بیضۂ مور آسماں ہے</span>}}}}}}}} | |||

| | alt2= | |||

| | File:Hafez Ghazal.jpg | |||

| | A ] versified by the Persian poet ] in Nastaliq font (by Software), in print:<sup>]]</sup> | |||

| {{rtl-para|1=fa|2={{nq|1={{raise|0.5em| | |||

| حافظ شیرازی<br/> | |||

| مرا عهدیست با جانان که تا جان در بدن دارم<br/> | |||

| هواداران کویش را چو جان خویشتن دارم | |||

| |size=1.25em}}}}}} | |||

| in a ] styled typeface: | |||

| {{rtl-para|1=fa|2={{naskh|1={{lower|0.1em|2=<span style="line-height: 1.2;"> | |||

| حافظ شیرازی<br/> | |||

| مرا عهدیست با جانان که تا جان در بدن دارم<br/> | |||

| هواداران کویش را چو جان خویشتن دارم | |||

| </span>}}}}}} | |||

| | alt3= | |||

| | File: | |||

| | Write a caption here | |||

| | alt4= | |||

| | File: | |||

| | Write a caption here | |||

| | alt5= | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Clear}} | {{Clear}} | ||

| == {{transl|fa|Shekasteh}} Nastaliq == | |||

| ''{{transl|fa|Shekasteh}}'' or ''{{transl|fa|Shekasteh Nastaliq}}'' ({{lang-fa|{{Nastaliq|شکسته نستعلیق}}}}, {{lang|fa|{{uninaskh|شکسته نستعلیق}}}}, "cursive {{transl|fa|Nastaliq}}" or literally "broken {{transl|fa|Nastaliq}}") style is a "streamlined" script of {{transl|fa|Nastaliq}}. It was developed in the 14th century to ease communication for non-calligraphic purposes, such as commerce and administration. ''Shekasta'' is characterized by " greatly reduced in size... thinner strokes... letters that in the formal versions of the Arabic script do not connect to the left were made to connect."<ref name="readnast3">{{Cite book |last1=Spooner |first1=Brian |title=Reading Nasta'liq: Persian and Urdu Hands from 1500 to the Present |last2=Hanaway |first2=William L. |year=1995 |isbn=978-1568592138 |pages=3}}</ref> | |||

| <gallery widths="200" heights="200"> | |||

| File:Chayyam guyand kasan behescht ba hur chosch ast small.png|A ] of Omar Khayyam in Shekasteh Nastaliq.<br/>In print:{{rtl-para|fa|{{Nastaliq|گویند کسان بهشت با حور خوش است<br/>من میگویم که آب انگور خوش است<br/>این نقد بگیر و دست از آن نسیه بدار<br/>کاواز دهل شنیدن از دور خوش است|size=1.25em}}}} In modern ]: {{rtl-para|fa|{{naskh|گویند کسان بهشت با حور خوش است<br/>من میگویم که آب انگور خوش است<br/>این نقد بگیر و دست از آن نسیه بدار<br/>کاواز دهل شنیدن از دور خوش است}}}} | |||

| File:Ghafeleye Omr.svg|A line of poetry by the Iranian poet ] in Shekasteh Nastaliq.<br/>In print: {{rtl-para|fa|{{Nastaliq|این قافلهٔ عُمر عجب میگذرد|size=1.25em}}}} In modern ]: {{rtl-para|fa|{{naskh|این قافلهٔ عُمر عجب میگذرد}}}} | |||

| File:Shikastah Nasta'liq Script.gif|An excerpt from Shaykh Sa'di's (d. 691/1292) "Gulistan" (The Rose Garden), in {{transl|fa|Shekasteh Nastaliq}} script. | |||

| File:Fath Ali Shah Qajar Firman in Shikasta Nastaliq script January 1831.jpg|]'s order in {{transl|fa|Shekasteh Nastaliq}} script, January 1831 | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| {{Clear}} | |||

| == Nastaliq typesetting == | |||

| [[File:Urdu couplet.svg|thumb| | |||

| An example of the {{transl|fa|Nastaliq}} script used for writing ].<br />Nastaliq:<br />{{rtl-para|{{lang|ur|{{nastaliq|size=1.25em|؎ کیا تنگ ہم ستم زدگان کا جہاں ہے<br/>جس میں ایک بیضۂ مور آسماں ہے}}}}}}<br />]:<br />{{rtl-para|{{Lang|ur|{{Lang|ar|size=1.25em|؎ کیا تنگ ہم ستم زدگان کا جہاں ہے<br/>جس میں ایک بیضۂ مور آسماں ہے}}}}}}]] | |||

| {{transl|fa|Nastaliq}} Typography first started with attempts to develop a metallic type for the script, but all such efforts failed. ] developed a {{transl|fa|Nastaliq}} Type, which was not close enough to {{transl|fa|Nastaliq}} and hence was never used other than by the college library to publish its own books. The State of Hyderabad Dakan (now in India) also attempted to develop a {{transl|fa|Nastaliq}} Typewriter but this attempt failed miserably and the file was closed with the phrase “Preparation of {{transl|fa|Nastaliq}} on commercial basis is impossible”. Basically, in order to develop such a metal type, thousands of pieces would be required.{{Citation needed|reason=there is no reference / citation given for these statements |date=June 2017}} | |||

| Modern {{transl|fa|Nastaliq}} typography began with the invention of ''Noori Nastaleeq'' which was first created as a digital font in 1981 through the collaboration of ] TI (as Calligrapher) and ] (formerly Monotype Corp & Monotype Typography).<ref name="Interview with Mirza Ahmad Jamil">{{cite web |last=Khurshiq |first=Iqbal |title=زندگی آگے بڑھنے کا نام اور جمود موت ہے: نوری نستعلیق کی ایجاد سے خط نستعلیق کی دائمی حفاظت ہوگئی |date=17 November 2013 |url=http://www.express.pk/story/197175/|publisher=Express|access-date=24 November 2013}}</ref> | |||

| Although this was a ground-breaking solution employing over 20,000 ligatures (individually designed character combinations)<ref>, 9 Feb 2021</ref> which provided the most beautiful results and allowed newspapers such as Pakistan's '']'' to use digital typesetting instead of an army of calligraphers, it suffered from two problems in the 1990s: (a) its non-availability on standard platforms such as ] or ], and (b) the non-] nature of text entry, whereby the document had to be created by commands in Monotype's proprietary ]. | |||

| === InPage === | === InPage === | ||

| In 1994, ] Urdu, which is a functional page layout software for Windows akin to ], was developed for Pakistan's newspaper industry by an Indian software company Concept Software Pvt Ltd. It offered the ''Noori Nastaliq'' font licensed from Monotype Imaging. This font is still used in current versions of the software for Windows. As of 2009, ] has become Unicode based, supporting more languages and the ''Faiz Lahori Nastaliq'' font with Kasheeda has been added to it along with compatibility with OpenType Unicode fonts. | |||

| In 1994, ] Urdu, which is a fully functional page layout software for Windows akin to ], was developed for Pakistan's newspaper industry by an Indian software company Concept Software Pvt Ltd. It offered the ''Noori Nastaliq'' font licensed from ]. This font, with its vast ligature base of over 20,000, is still used in current versions of the software for Windows. As of 2009 ] has become Unicode based, supporting more languages, and the ''Faiz Lahori Nastaliq'' font with Kasheeda has been added to it along with compatibility with OpenType Unicode fonts. Nastaliq Kashish{{clarify|date=November 2013}} has been made for the first time{{clarify|date=November 2013}} in the history of {{transl|fa|Nastaliq}} Typography.{{Citation needed|reason=there is no reference / citation given for these statements |date=June 2017}} | |||

| === Cross platform Nastaliq fonts === | === Cross platform Nastaliq fonts === | ||

| ] | |||

| * Windows 8 was the first version of Microsoft Windows to have native Nastaliq support, through Microsoft's "Urdu Typesetting" font.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.siao2.com/2011/11/16/10237715.aspx|title=The evolving Story of Locale Support, part 9: Nastaleeq vs. Nastaliq? Either way, Windows 8 has got it!|publisher=MSDN Blogs|access-date=2013-03-24}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| * Windows 8 was the first version of Microsoft Windows to have native Nastaliq support, through Microsoft's "Urdu Typesetting" font.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.siao2.com/2011/11/16/10237715.aspx |title=The evolving Story of Locale Support, part 9: Nastaleeq vs. Nastaliq? Either way, Windows 8 has got it! |publisher=MSDN Blogs |access-date=2013-03-24}}</ref> | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| * Google has an open-source Nastaliq font called ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.google.com/get/noto/#nastaliq-aran|title = Google Noto Fonts}}</ref> Apple provides this font on all Mac installations since macOS High Sierra. Likewise, Apple has carried this font on iOS devices since iOS 11.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://tribune.com.pk/story/1514433/apple-finally-enables-nastaleeq-typeface-urdu-keyboard-ios-11/|title=Apple finally enables Nastaleeq typeface for Urdu keyboard in iOS 11|date=23 September 2017}}</ref> | * Google has an open-source Nastaliq font called ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.google.com/get/noto/#nastaliq-aran|title = Google Noto Fonts}}</ref> Apple provides this font on all Mac installations since macOS High Sierra. Likewise, Apple has carried this font on iOS devices since iOS 11.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://tribune.com.pk/story/1514433/apple-finally-enables-nastaleeq-typeface-urdu-keyboard-ios-11/|title=Apple finally enables Nastaleeq typeface for Urdu keyboard in iOS 11|date=23 September 2017}}</ref> | ||

| * ] features a more extensive character set than most Nastaliq typefaces, supporting: |

* ] features a more extensive character set than most Nastaliq typefaces, supporting:<!--Ref does not explicitly list all of these but Nastaliq is a style for Urdu and if it can do Urdu, it also covers full Persian alphabet, specified Iranian because obviously it can't do Tajiki--> ], ], ], Khowar, Palula, Saraiki, Shina.<ref>{{cite web|title=What is Special About Awami Nastaliq? - Awami Nastaliq|url=http://software.sil.org/awami/what-is-special/|website=software.sil.org|date=17 July 2017}}</ref> | ||

| * ] was created for ] on ] |

* ] was created for ] on ] websites in 2013. The font was announced by Urdu poet ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://twitter.com/fahmidariaz/status/403607540698578944|title=Amar Nastaleeq Font for Urdu Web Publishing|first=fahmida|last=Riaz|website=Twitter.com|date=21 November 2013}}</ref> | ||

| {{Clear}} | {{Clear}} | ||

| == Letter forms == | == Letter forms == | ||

| The ''Nastaliq'' style uses more than three general forms for many letters,<ref>{{cite web|last1=FWP|title=Urdu: some thoughts about the script and grammar, and other general notes for students assembled from years of classroom notes by FWP|url=http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00urdu/urduscript/index.html|website=www.columbia.edu|access-date=28 February 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230406004235/http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00urdu/urduscript/index.html|archive-date=2023-04-06}}</ref><ref name="Scanned table">{{cite web|title=The chart below gives the different positional variants of some of the significantly different letters. (scanned document)|url=http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00urdu/urduscript/graphics/naimchart.gif|website=Linked by www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00urdu/urduscript/section00.html#00_01|access-date=28 February 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230407145904if_/http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00urdu/urduscript/graphics/naimchart.gif|archive-date=2023-04-07|url-status=dead}}</ref> even in non-decorative documents. For example, most documents written in ].{{Clarify|date=April 2022}} | |||

| ==In Unicode== | |||

| For the ], and many others derived from it, letters are regarded as having two or three general forms each, based on their position in the word (though obviously ] can add a great deal of complexity). But the Nastaliq style uses more than three general forms for many letters,<ref>{{cite web |last1=FWP |title=Urdu: some thoughts about the script and grammar, and other general notes for students assembled from years of classroom notes by FWP |url=http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00urdu/urduscript/index.html |website=www.columbia.edu |access-date=28 February 2020}}</ref><ref name="Scanned table">{{cite web |title=The chart below gives the different positional variants of some of the significantly different letters. (scanned document) |url=http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00urdu/urduscript/graphics/naimchart.gif |website=Linked by www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00urdu/urduscript/section00.html#00_01 |access-date=28 February 2020}}</ref> even in non-decorative documents. For example, most documents written in ], which uses the Nastaliq style. | |||

| {{see also|Arabic (Unicode block)}} | |||

| Nastaliq is not separately encoded in ] as it is a particular style of Arabic script and not a writing system in its own right. Nastaliq letterforms are produced by choosing a Nastaliq ] to display the text. | |||

| {{Clear}} | |||

| == See also == | == See also == | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| Line 147: | Line 151: | ||

| {{Reflist}} | {{Reflist}} | ||

| == |

== Bibliography == | ||

| * Sheila Blair |

* {{Cite book|last=Blair|year=2008|first=Sheila|author-link=Sheila Blair|title=Islamic Calligraphy|publisher=Edinburgh University Press|isbn=978-0748612123|ref={{SfnRef|Blair}}}} | ||

| == External links == | == External links == | ||

| {{Commons category|Nastaliq}} | {{Commons category|Nastaliq}} | ||

| * : Online Service For {{ |

* : Online Service For {{transliteration|fa|Nastaliq}} Calligraphy | ||

| * : Online Service For {{ |

* : Online Service For {{transliteration|fa|Nastaliq}} Calligraphy | ||

| * | * | ||

| * for Macintosh by ] | * for Macintosh by ] | ||

| * : Official InPage Urdu DTP software site | * : Official InPage Urdu DTP software site | ||

| * : Official Faiz {{ |

* : Official Faiz {{transliteration|fa|Nastaliq}} site | ||

| * {{in lang|fr}} | * {{in lang|fr}} | ||

| * | * | ||

| * : A Nastaliq font by SIL International | * : A Nastaliq font by SIL International | ||

| {{Islamic calligraphy}} | {{Islamic calligraphy}} | ||

| Line 171: | Line 175: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 19:01, 22 December 2024

Predominant calligraphic hand of the Perso-Arabic script The Nastaliq text on this page will show in a different style if you do not have a Nastaliq font installed.

| Nastaliq نَسْتَعْلِیق | |

|---|---|

"Welcome to Misplaced Pages" in Persian "Welcome to Misplaced Pages" in Persianfrom Persian Misplaced Pages (In print: به ویکیپدیا خوش آمدید) | |

| Script type | Abjad |

| Time period | 14th century AD – present |

| Direction | Right-to-left |

| Region | Commonly used in Iran, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Xinjiang Historically used in Iraq, Turkey, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan |

| Languages | Classical Persian Kashmiri Punjabi Urdu Turkic languages |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Aran (161), Arabic (Nastaliq variant) |

| Part of a series on |

| Calligraphy |

|---|

|

| By script |

The dotted form ڛ is used in place of س.

Nastaliq (/ˌnæstəˈliːk, ˈnæstəliːk/; , Persian: [næstʰæʔliːq]; Urdu: [nəst̪ɑːliːq]), also romanized as Nastaʿlīq or Nastaleeq, is one of the main calligraphic hands used to write the Perso-Arabic script and it is used for some Indo-Iranian languages, predominantly Classical Persian, Kashmiri, Punjabi and Urdu. It is often used also for Ottoman Turkish poetry, but rarely for Arabic. Nastaliq developed in Iran from naskh beginning in the 13th century and remains widely used in Iran, India, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and other countries for written poetry and as a form of art.

History

The name Nastaliq "is a contraction of the Persian naskh-i ta'liq (Persian: نَسْخِ تَعلیق), meaning a hanging or suspended naskh." Virtually all Safavid authors (like Dust Muhammad or Qadi Ahmad) attributed the invention of nastaliq to Mir Ali Tabrizi, who lived at the end of the 14th and the beginning of the 15th century. That tradition was questioned by Elaine Wright, who traced the evolution of Nastaliq in 14th-century Iran and showed how it developed gradually among scribes in Shiraz. According to her studies, nastaliq has its origin from naskh alone, and not by combining naskh and taliq, as was commonly thought. In addition to study of the practice of calligraphy, Elaine Wright also found a document written by Jafar Tabrizi c. 1430, according to whom:

It must be known that nastaʿliq is derived from naskh. Some Shirazi modified it by taking out the flattened kaf and straight bottom part of sin, lam and nun. From other scripts they then brought in a curved sin and stretched forms and introduced variations in the thickness of the line. So a new script was created, to be named nastaʿliq. After a while Tabrizi modified what Shirazi had created by gradually rendering it thinner and defining its canons, until the time when Khwaja Mir ʿAli Tabrizi brought this script to perfection.

Thus, "our earliest written source also credits Shirazi scribes with the development of nastaʿliq and Mir ʿAli Tabrizi with its canonization." The picture of origin of nastaliq presented by Elaine Wright was further complicated by studies of Francis Richard, who on the basis of some manuscripts from Tabriz argued that its early evolution was not confined to Shiraz. Finally, many authors point out that development of nastaʿliq was a process which takes a few centuries. For example, Gholam-Hosayn Yusofi, Ali Alparslan and Sheila Blair recognize gradual shift towards nastaʿliq in some 13th-century manuscripts. Hamid Reza Afsari traces first elements of the style in 11th-century copies of Persian translations of the Qur'an.

Persian differs from Arabic in its proportion of straight and curved letters. It also lacks the definite article al-, whose upright alif and lam are responsible for distinct verticality and rhythm of the text written in Arabic. Hanging scripts like taliq and nastaliq were suitable for writing Persian – when taliq was used for court documents, nastaliq was developed for Persian poetry, "whose hemistiches encourage the pile-up of letters against the intercolumnar ruling. Only later was it adopted for prose."

The first master of nastaliq was aforementioned Mir Ali Tabrizi, who passed his style to his son ʿUbaydallah. The student of Ubaydallah, Jafar Tabrizi (d. 1431) (see quote above), moved to Herat, when he became the head of the scriptorium (kitabkhana) of prince Baysunghur (therefore his epithet Baysunghuri). Jafar trained several students in nastaliq, of whom the most famous was Azhar Tabrizi (d. 1475). Its classical form nastaliq achieved under Sultan Ali Mashhadi (d. 1520), a student of Azhar (or perhaps one of Azhar's students) who worked for Sultan Husayn Bayqara (1469–1506) and his vizier Ali-Shir Nava'i. At the same time a different style of nastaliq developed in western and southern Iran. It was associated with ʿAbd al-Rahman Khwarazmi, the calligrapher of the Pir Budaq Qara Qoyunlu (1456–1466) and after him was followed by his children, ʿAbd al-Karim Khwarazmi and ʿAbd al-Rahim Anisi (both active at the court of Ya'qub Beg Aq Qoyunlu; 1478–1490). This more angular western Iranian style was largely dominant at the beginning of the Safavid era, but then lost to the style canonized by Sultan Ali Mashhadi – although it continued to be used in the Indian subcontinent.

The most famous calligrapher of the next generation in eastern lands was Mir Ali Heravi (d. 1544), who was master of nastaliq, especially renowned for his calligraphic specimens (qitʿa). The eastern style of nastaliq became the predominant style in western Iran, as artists gravitated to work in Safavid royal scriptorium. The most famous of these calligraphers working for the court in Tabriz was Shah Mahmud Nishapuri (d. 1564/1565), known especially for the unusual choice of nastaliq as a script used for the copy of the Qur'an. Its apogeum nastaliq achieved in writings of Mir Emad Hassani (d. 1615), "whose style was the model in the following centuries." Mir Emad's successors in the 17th and 18th centuries had developed a more elongated style of nastaliq, with wider spaces between words. Mirza Mohammad Reza Kalhor (d. 1892), the most important calligrapher of the 19th century, reintroduced the more compact style, writing words on a smaller scale in a single motion. In the 19th century nastaliq was also adopted in Iran for lithographed books. In the 20th century, "the use of nastaliq declined. After World War II, however, interest in calligraphy and above all in nastaliq revived, and some outstandingly able masters of the art have since then emerged."

The use of nastaliq very early expanded beyond Iran. Timurids brought it to the India subcontinent and nastaliq became favorite script at the Persian court of the Mughals. For Akbar (1556–1605) and Jahangir (1605–1627) worked such famous masters of nastaliq as Muhammad Husayn Kashmiri (d. 1611/1612) and Abd al-Rahim Anbarin-Qalam. Another important practitioner of the script was Abd al-Rashid Daylami (d. 1671), nephew and student of Mir Emad, who after his arrival in India became court calligrapher of Shah Jahan (1628–1658). During this era Nastaliq became the common script for writing the Hindustani language, especially Standard Urdu.

Nastaliq was also adopted in Ottoman Empire, which has always had strong cultural ties to Iran. Here it was known as taliq (Turkish talik), which should not be confused with Persian taliq script. First Iranian calligraphers who brought nastaliq to Ottoman lands, like Asadullah Kirmani (d. 1488), belonged to the western tradition. But relatively early Ottoman calligraphers adopted eastern style of nastaliq. In 17th century, student of Mir Emad, Darvish Abdi Bokharai (d. 1647), transplanted his style to Istanbul. The greatest master of nastaliq in 18th century was Mehmed Yasari (d. 1798), who closely followed Mir Emad. This tradition was further developed by son of Yasari, Mustafa Izzet (d. 1849), who was a real founder of distinct Ottoman school of nastaliq. He introduced new and precise proportions of the script, different than in Iranian tradition. The most important member of this school in the second half of the 19th century was Sami Efendi (d. 1912), who taught many famous practitioners of nastaliq, like Mehmed Nazif Bey (d. 1913), Mehmed Hulusi Yazgan (d. 1940) and Necmeddin Okyay (d. 1976). The specialty of Ottoman school was celî nastaliq used in inscriptions and mosque plates.

-

Opening page to a copy of Nizami's Khosrow and Shirin with calligraphy by Mir Ali Tabrizi. Tabriz, c. 1410. Freer Gallery of Art

Opening page to a copy of Nizami's Khosrow and Shirin with calligraphy by Mir Ali Tabrizi. Tabriz, c. 1410. Freer Gallery of Art

-

Opening page from a manuscript of Saʿdi's Gulistan copied by Jafar Tabrizi. Herat, 1426/27. Chester Beatty Library

Opening page from a manuscript of Saʿdi's Gulistan copied by Jafar Tabrizi. Herat, 1426/27. Chester Beatty Library

-

Page from a manuscript of Attar's Mantiq al-Tayr copied by Sultan Ali Mashhadi. Herat, dated 25 April 1487. Metropolitan Museum of Art

Page from a manuscript of Attar's Mantiq al-Tayr copied by Sultan Ali Mashhadi. Herat, dated 25 April 1487. Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Colophon to Nizami's Khamsa copied by ʿAbd al-Rahim Khwarazmi Anisi. Tabriz, 1481. Topkapı Palace Museum

Colophon to Nizami's Khamsa copied by ʿAbd al-Rahim Khwarazmi Anisi. Tabriz, 1481. Topkapı Palace Museum

-

Rubaʿi copied by Mir Ali Heravi and later mounted in the so-called "Kevorkian Album". Bukhara, c. 1534. Metropolitan Museum of Art

Rubaʿi copied by Mir Ali Heravi and later mounted in the so-called "Kevorkian Album". Bukhara, c. 1534. Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Opening double page from the Qur'an manuscript copied by Shah Mahmud Nishapuri, dated 12 June 1538. Topkapı Palace Museum

Opening double page from the Qur'an manuscript copied by Shah Mahmud Nishapuri, dated 12 June 1538. Topkapı Palace Museum

-

Sura Al-Fatiha copied by Mir Emad Hassani. Museum of the Islamic Era

Sura Al-Fatiha copied by Mir Emad Hassani. Museum of the Islamic Era

-

Colophon from a manuscript of Nizami's Khamsa copied by Abd al-Rahim Anbarin-Qalam, dated 14 December 1595. British Library

Colophon from a manuscript of Nizami's Khamsa copied by Abd al-Rahim Anbarin-Qalam, dated 14 December 1595. British Library

-

Page from a manuscript of Amir Khusrau's Khamsa copied by Muhammad Husayn Kashmiri and finished in the forty-second year of Akbar's reign (March 1597 – March 1598). Walters Art Museum

Page from a manuscript of Amir Khusrau's Khamsa copied by Muhammad Husayn Kashmiri and finished in the forty-second year of Akbar's reign (March 1597 – March 1598). Walters Art Museum

-

Calligrapher's license with a rubaʿi copied by Mehmed Yasari from an exemplar by Mir Emad. Istanbul, 1754. Topkapı Palace Museum

Calligrapher's license with a rubaʿi copied by Mehmed Yasari from an exemplar by Mir Emad. Istanbul, 1754. Topkapı Palace Museum

-

Levha (calligraphic inscription) by Sami Efendi. Istanbul, 1906. Sakıp Sabancı Museum

Levha (calligraphic inscription) by Sami Efendi. Istanbul, 1906. Sakıp Sabancı Museum

-

Page from the muraqqa with Khaqani's ode on the Prophet copied by Mehmed Nazif Bey from an original by Mustafa Izzet. 20th century (before 1913). Sakıp Sabancı Museum

Page from the muraqqa with Khaqani's ode on the Prophet copied by Mehmed Nazif Bey from an original by Mustafa Izzet. 20th century (before 1913). Sakıp Sabancı Museum

Shekasteh Nastaliq

In print:گویند کسان بهشت با حور خوش است

من میگویم که آب انگور خوش است

این نقد بگیر و دست از آن نسیه بدار

کاواز دهل شنیدن از دور خوش است In modern Naskh: گویند کسان بهشت با حور خوش است

من میگویم که آب انگور خوش است

این نقد بگیر و دست از آن نسیه بدار

کاواز دهل شنیدن از دور خوش است

In print: این قافلهٔ عُمر عجب میگذرد In modern Naskh: این قافلهٔ عُمر عجب میگذرد

Shekasteh or Shekasteh Nastaliq (Persian: شکسته نستعلیق, شکسته نستعلیق, "cursive Nastaliq" or literally "broken Nastaliq") style is a "streamlined" form of Nastaliq. Its development is connected with the fact that "the increasing use of nastaʿlīq and consequent need to write it quickly exposed it to a process of gradual attrition." The shekasteh nastaliq emerged in the early 17th century and differed from proper nastaliq only in so far as some of the letters were shrunk (shekasteh, lit. "broken") and detached letters and words were sometimes joined. These unauthorized connections "mean that calligraphers can write shekasteh faster than any other script." Manuscripts from this early period show signs of the influence of shekasteh taliq; while having the appearance of a shrunken form of nastaliq, they also contain features of taliq "due to their being written by scribes who had been trained in taʿlīq." Shekasteh nastaliq (usually shortened to simply skehasteh), being more easily legible than taliq gradually replaced the latter as the script of decrees and documents. Later, it also came into use for writing prose and poetry.

The first important calligraphers of shekasteh were Mohammad Shafiʿ Heravi (d. 1670–71) (he was known as Shafiʿa and hence shekasteh was sometimes called shafiʿa or shifiʿa) and Mortazaqoli Khan Shamlu (d. 1688–89). Both of them produced works of real artistic quality, which does not change the fact that in this early phase shekasteh still lacked consistency (it is especially visible in writing of Mortazaqoli Khan Shamlu). Most modern scholars consider that shekasteh reached its peak of artistic perfection under Abdol Majid Taleqani (d. 1771), "who gave the script its distinctive and definite form." The tradition of Taleqani was later followed by Mirza Kuchek Esfahani (d. 1813), Gholam Reza Esfahani (d. 1886–87) and Ali Akbar Golestaneh (d. 1901).

The added frills made shekasteh increasingly difficult to read and it remained the script of documents and decrees, "while nastaʿliq retained its pre-eminence as the main calligraphic style." The need for simplification of shekasteh resulted in development of secretarial style (shekasteh-ye tahriri) by writers like Adib-al-Mamalek Farahani (d. 1917) and Nezam Garrusi (d. 1900). The secretarial style is a simplified form of shekasteh which is faster to write and read, but less artistic. Long used in governmental and other institutions in Iran, shekasteh degenerated in the first half of the 20th century, but later again engaged the attention of calligraphers. Shekasteh was used only in Iran and to a small extent in Afghanistan and Ottoman Empire. Its use in Afghanistan was different from the Persian norm and sometimes only as experimental devices (tafannon)

-

Calligraphy by Mohammad Shafiʿ Heravi. National Library of Iran

Calligraphy by Mohammad Shafiʿ Heravi. National Library of Iran

-

Double page from the "Majmu‘a-i munsh‘at" – collection of correspondence sent by Persian rulers compiled by Abu‘l-Qasim Ivughli Haydar. Isfahan, 1682. Arthur M. Sackler Gallery

Double page from the "Majmu‘a-i munsh‘at" – collection of correspondence sent by Persian rulers compiled by Abu‘l-Qasim Ivughli Haydar. Isfahan, 1682. Arthur M. Sackler Gallery

-

Calligraphy by Abdol Majid Taleqani. Golestan Palace Library

Calligraphy by Abdol Majid Taleqani. Golestan Palace Library

-

Plea for tax relief copied by Mirza Kuchak Esfahani. Iran, 1795–1796. Harvard Art Museums

Plea for tax relief copied by Mirza Kuchak Esfahani. Iran, 1795–1796. Harvard Art Museums

-

Firman issued in the Name of Fath-Ali Shah Qajar. Iran, January 1831. Metropolitan Museum of Art

Firman issued in the Name of Fath-Ali Shah Qajar. Iran, January 1831. Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Calligraphy by Ali Akbar Golestaneh. Iran, 1896. Library of the Islamic Parliament of Iran

Calligraphy by Ali Akbar Golestaneh. Iran, 1896. Library of the Islamic Parliament of Iran

Nastaliq typesetting

Modern Nastaliq typography began with the invention of Noori Nastaleeq which was first created as a digital font in 1981 through the collaboration of Ahmed Mirza Jamil (as calligrapher) and Monotype Imaging (formerly Monotype Corp & Monotype Typography). Although this employed over 20,000 ligatures (individually designed character combinations), it provided accurate results and allowed newspapers such as Pakistan's Daily Jang to use digital typesetting instead of a group of calligraphers. It suffered from two problems in the 1990s: its non-availability on standard platforms such as Microsoft Windows or Mac OS, and the non-WYSIWYG nature of text entry, whereby the document had to be created by commands in Monotype's proprietary page description language.

Examples of Nastaliq typesetting-

Persian Chalipa panel, Mir Emad

Persian Chalipa panel, Mir Emad

In print: بودم به تو عمری و ترا سیر ندیدم

از وصل تو هرگز به مرادی نرسیدم

از بهر تو بیگانه شدم از همه خویشان

وحشی صفت از خلق به یکبار بریدم In Naskh styled typeface: بودم به تو عمری و ترا سیر ندیدم

از وصل تو هرگز به مرادی نرسیدم

از بهر تو بیگانه شدم از همه خویشان

وحشی صفت از خلق به یکبار بریدم -

An example of the Nastaliq script used for writing Urdu.

An example of the Nastaliq script used for writing Urdu.

Nastaliq:

؎ کیا تنگ ہم ستم زدگان کا جہاں ہے

جس میں ایک بیضۂ مور آسماں ہے

Naskh:

؎ کیا تنگ ہم ستم زدگان کا جہاں ہے

جس میں ایک بیضۂ مور آسماں ہے -

A couplet versified by the Persian poet Hafez in Nastaliq font (by Software), in print: حافظ شیرازی

A couplet versified by the Persian poet Hafez in Nastaliq font (by Software), in print: حافظ شیرازی

مرا عهدیست با جانان که تا جان در بدن دارم

هواداران کویش را چو جان خویشتن دارم in a Naskh styled typeface: حافظ شیرازی

مرا عهدیست با جانان که تا جان در بدن دارم

هواداران کویش را چو جان خویشتن دارم

InPage

In 1994, InPage Urdu, which is a functional page layout software for Windows akin to QuarkXPress, was developed for Pakistan's newspaper industry by an Indian software company Concept Software Pvt Ltd. It offered the Noori Nastaliq font licensed from Monotype Imaging. This font is still used in current versions of the software for Windows. As of 2009, InPage has become Unicode based, supporting more languages and the Faiz Lahori Nastaliq font with Kasheeda has been added to it along with compatibility with OpenType Unicode fonts.

Cross platform Nastaliq fonts

- Windows 8 was the first version of Microsoft Windows to have native Nastaliq support, through Microsoft's "Urdu Typesetting" font.

- Google has an open-source Nastaliq font called Noto Nastaliq Urdu. Apple provides this font on all Mac installations since macOS High Sierra. Likewise, Apple has carried this font on iOS devices since iOS 11.

- Awami Nastaliq features a more extensive character set than most Nastaliq typefaces, supporting: Urdu, Balochi, Persian, Khowar, Palula, Saraiki, Shina.

- Amar Nastaleeq was created for web embedding on Urdu websites in 2013. The font was announced by Urdu poet Fahmida Riaz.

Letter forms

The Nastaliq style uses more than three general forms for many letters, even in non-decorative documents. For example, most documents written in Urdu.

In Unicode

See also: Arabic (Unicode block)Nastaliq is not separately encoded in Unicode as it is a particular style of Arabic script and not a writing system in its own right. Nastaliq letterforms are produced by choosing a Nastaliq font to display the text.

See also

References

- Akram, Qurat ul Ain; Hussain, Sarmad; Niazi, Aneeta; Anjum, Umair; Irfan, Faheem (April 2014). "Adapting Tesseract for Complex Scripts: An Example for Urdu Nastalique". 2014 11th IAPR International Workshop on Document Analysis Systems. 11th IAPR International Workshop on Document Analysis Systems. Tours, France: IEEE. pp. 191–195. doi:10.1109/DAS.2014.45. ISBN 978-1-4799-3243-6.

- "Nastaliq". Lexico Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on March 28, 2022. Retrieved 2020-07-05.

- Blair, p. xxii, 286.

- ^ Gholam-Hosayn Yusofi (December 15, 1990). "Calligraphy". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Atif Gulzar; Shafiq ur Rahman (2007). "Nastaleeq: A challenge accepted by Omega" (PDF). TUGboat. 29: 1–6.

- Blair, p. 274.

- ^ Blair, p. 275.

- Ali Alparslan. "K̲h̲aṭṭ ii. In Persia". Encyclopaedia of Islam. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0502.

- Blair, p. xxii.

- ^ Hamid Reza Afsari (17 June 2021). "Calligraphy". Encyclopaedia Islamica.

- Blair, p. 276.

- Blair, p. 277-280.

- Blair, p. 284, 430.

- Blair, p. 430-436.

- Blair, p. 446-447.

- ^ Gholam-Hosayn Yusofi. "CALLIGRAPHY (continued)". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Blair, p. 536-539, 552-554.

- Blair, p. 513-518.

- ^ Ali Alparslan. "NESTA'LİK". İslâm Ansiklopedisi.

- Spooner, Brian; Hanaway, William L. (1995). Reading Nasta'liq: Persian and Urdu Hands from 1500 to the Present. p. 3. ISBN 978-1568592138.

- ^ Blair, p. 441.

- Blair, p. 444-445.

- Priscilla Soucek. "ʿABD-AL-MAJĪD ṬĀLAQĀNĪ". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Maryam Ekhtiar. "ḠOLĀM-REŻĀ ḴOŠNEVIS". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Maryam Ekhtiar. "GOLESTĀNA, ʿALI-AKBAR". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Blair, p. 445, 471.

- Khurshiq, Iqbal (17 November 2013). "زندگی آگے بڑھنے کا نام اور جمود موت ہے: نوری نستعلیق کی ایجاد سے خط نستعلیق کی دائمی حفاظت ہوگئی". Express. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- How to bring a language to the future, 9 Feb 2021

- "The evolving Story of Locale Support, part 9: Nastaleeq vs. Nastaliq? Either way, Windows 8 has got it!". MSDN Blogs. Retrieved 2013-03-24.

- "Google Noto Fonts".

- "Apple finally enables Nastaleeq typeface for Urdu keyboard in iOS 11". 23 September 2017.

- "What is Special About Awami Nastaliq? - Awami Nastaliq". software.sil.org. 17 July 2017.

- Riaz, fahmida (21 November 2013). "Amar Nastaleeq Font for Urdu Web Publishing". Twitter.com.

- FWP. "Urdu: some thoughts about the script and grammar, and other general notes for students assembled from years of classroom notes by FWP". www.columbia.edu. Archived from the original on 2023-04-06. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- "The chart below gives the different positional variants of some of the significantly different letters. (scanned document)". Linked by www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00urdu/urduscript/section00.html#00_01. Archived from the original on 2023-04-07. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

Bibliography

- Blair, Sheila (2008). Islamic Calligraphy. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0748612123.

External links

- Rumicode: Online Service For Nastaliq Calligraphy

- Nastaliq Online: Online Service For Nastaliq Calligraphy

- Iranian Calligraphers Association

- Nastaliq Writer for Macintosh by SIL

- InPage Urdu: Official InPage Urdu DTP software site

- Faiz Nastaliq: Official Faiz Nastaliq site

- Profiles and works of World Islamic calligraphy (in French)

- Nastaliq Script | Persian Calligraphy

- Awami Nastaliq: A Nastaliq font by SIL International

| Islamic calligraphy | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Styles |

|  | ||||||||

| Objects | ||||||||||

| Calligraphers | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Organizations | ||||||||||

| Influences | ||||||||||

| Part of Islamic arts | ||||||||||

| Arabic language | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overviews | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Scripts | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Letters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Varieties |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Academic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Linguistics | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Calligraphy · Script | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||