| Revision as of 21:47, 20 August 2021 editErick Soares3 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users4,105 edits →References← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 17:11, 2 September 2024 edit undoKjersti Lie (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users724 edits →Childhood and slavery: internal linkTag: Visual edit | ||

| (106 intermediate revisions by 34 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|19th century Brazilian lawyer and abolitionist}} | |||

| {{Expand Portuguese|date=February 2017|Luís Gama}} | |||

| {{Infobox |

{{Infobox person | ||

| | name = Luís Gama | | name = Luís Gama | ||

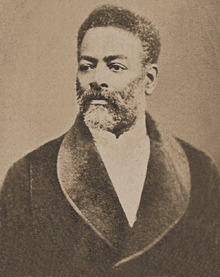

| | image = Luiz Gama c 1880.png | | image = Luiz Gama c 1880.png | ||

| | caption = Gama, {{circa|1880}} | |||

| | imagesize = 200px | |||

| | native_name = | |||

| | alt = | |||

| | native_name_lang = | |||

| | caption = A photograph of Luís Gama | |||

| | birth_date = {{Birth date|1830|06|21|df=yes}} | |||

| | pseudonym = Getulino | |||

| | birth_place = ], ] | |||

| | birth_name = Luís Gonzaga Pinto da Gama | |||

| | |

| death_date = {{Death date and age|1882|08|24|1830|06|21|df=yes}} | ||

| | |

| death_place = ], ], ] | ||

| | resting_place = | |||

| | death_date = {{death date and age|1882|8|24|1830|6|21|df=y}} | |||

| | resting_place_coordinates = <!-- {{coord|LAT|LONG|type:landmark|display=inline}} --> | |||

| | death_place = ], ], ] | |||

| | burial_place = <!-- may be used instead of resting_place and resting_place_coordinates (displays "Burial place" as label) --> | |||

| | occupation = ], ], journalist, republican and abolitionist | |||

| | burial_coordinates = <!-- {{coord|LAT|LONG|type:landmark|display=inline}} --> | |||

| | nationality = {{flagicon|Brazil}} Brazilian | |||

| | monuments = {{ill|Luiz Gama (Yolando Mallozzi)|pt|lt=Luiz Gama}} | |||

| | citizenship = | |||

| | nationality = Brazilian | |||

| | education = | |||

| | other_names = Afro, Getúlio, Barrabaz,<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.letras.ufmg.br/literafro/autores/655-luiz-gama|title=Luiz Gama|date=2021-05-11|access-date=2021-08-21|language=pt-br}}</ref> Spartacus and John Brown<ref name=FSPiV/> | |||

| | alma_mater = ] | |||

| | education = ]<ref name=Palmares>{{Cite web|url=http://www.palmares.gov.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Luiz-Gama-1830-1882-um-her%C3%B3i-nacional.pdf|title=Luiz Gama (1830–1882), um herói nacional|author=Ebnézer Maurílio Nogueira da Silva|access-date=2021-08-24|language=pt-br}}</ref> | |||

| | period = | |||

| | occupation = Lawyer, writer, abolitionist | |||

| | genre = | |||

| | |

| years_active = | ||

| | party = ]{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|p=37}}<br />] (1873–1873)<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.geledes.org.br/luiz-gama/|title=Luíz Gama|date=2010-06-29|access-date=2021-08-26|language=pt-br}}</ref>{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|p=76}} | |||

| | movement = | |||

| | known_for = He was able to have had freed more than 500 people from the condition of slavery.{{Sfn|Ferreira|}} | |||

| | notableworks = ''Primeiras Trovas Burlescas de Getulino'' | |||

| | notable_works = Primeiras Trovas Burlescas do Getulino | |||

| | spouse = | |||

| | spouse = Claudina Fortunata Sampaio{{Sfn|dos Santos|2014|p=6}} | |||

| | partner = | |||

| | children = Benedito Graco Pinto da Gama{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|p=22}} | |||

| | children = | |||

| | mother = ]{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|p=15}} | |||

| | relatives = | |||

| | father = A fidalgo from a Portuguese family{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|p=15}} | |||

| | influences = | |||

| | awards = {{ill|Franz de Castro Holzwarth|pt|Franz de Castro Holzwarth|lt=XXXII Prêmio Franz de Castro Holzwarth de Direitos Humanos}}<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.oabsp.org.br/noticias/2015/12/luiz-gama-vence-xxxii-premio-franz-de-castro-holzwarth-de-direitos-humanos.10557 |title=Luiz Gama vence XXXII Prêmio Franz de Castro Holzwarth de Direitos Humanos |date=2015-12-10 |access-date=2020-09-15 |website=OAB SP |language=pt-br}}</ref> | |||

| | influenced = | |||

| | awards = | |||

| | signature = | |||

| | website = | |||

| | portaldisp = | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Luís Gonzaga Pinto da Gama'''{{efn|In the 19th orthography, his name was ''Luiz Gama''.}} (21 June 1830 – 24 August 1882) was a Brazilian ],<ref>{{Cite web |date=2021-11-08 |title=Documentos inéditos confirmam que Luiz Gama era advogado |url=https://www.brasildefato.com.br/2021/11/08/documentos-ineditos-confirmam-que-luiz-gama-era-advogado |access-date=2024-06-03 |website=Brasil de Fato |language=pt-BR}}</ref> ], ], journalist and writer,<ref name=Palmares/> and the Patron of the ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2015-2018/2018/Lei/L13629.htm|title=Lei 13.629 de 16/01/18|date=2018-01-16|access-date=2018-01-17|work=www.planalto.gov.br|language=pt-br}}</ref> | |||

| Born to a free black mother and a white father, he was nevertheless made a slave at the age of 10, and remained illiterate until the age of 17. He judicially won his own freedom and began to work as a lawyer on behalf of the captives, and by the age of 29 he was already an established author and considered "the greatest abolitionist in Brazil".<ref name=als>{{cite book|author=Antônio Loureiro de Souza |title=Bahianos Ilustres: 1564 – 1925 |place=Salvador |year=1959 |page=102 |language=pt-br}}</ref> | |||

| '''Luís Gonzaga Pinto da Gama''' (June 21, 1830 – August 24, 1882) was a Brazilian ] poet, journalist, lawyer, Republican and a prominent ].<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|title=Encyclopedia of Latin American history and culture|date=2008|publisher=Gale|others=Kinsbruner, Jay., Langer, Erick Detlef.|isbn=9780684312705|edition= 2nd|location=Detroit|oclc=191318189}}</ref><ref name=":1">{{Cite book|title=Encyclopedia of African-American culture and history : the Black experience in the Americas|date=2006|publisher=Macmillan Reference USA|others=Palmer, Colin A., 1944-|isbn=0028658213|edition= 2nd|location=Detroit|oclc=60323165}}</ref> | |||

| Although considered one of the exponents of {{ill|Romantism in Brazil|pt|Romantismo no Brasil|lt=romanticism}},{{Sfn|Ferreira|}} works such as ]'s "''Apresentação da Poesia Brasileira''" do not even mention his name.<ref>{{cite book|author=Manuel Bandeira |title=Apresentação da Poesia Brasileira (seguida de uma antologia de versos) |publisher=Ediouro |year=1964 |pages=451|language=pt-br }}</ref> He had such a unique life that it is difficult to find, among his biographers, any who do not become passionate when portraying him – being himself also charged with passion, emotional and yet captivating.<ref name=":0">{{cite web |last=Santana |first=Andreia |url=https://mardehistorias.wordpress.com/2010/09/11/resenha-as-novas-biografias-de-luiz-gama/ |title=Resenha: As novas biografias de Luiz Gama |date=2010-09-11 |access-date=2021-07-16|website=Mar de Histórias|language=pt-br}}</ref> | |||

| ==Personal life== | |||

| Gama was born free in 1830 in ], to a ] '']'' who lost all his fortune with ], and Luísa Mahin (also spelled Maheu), a free African woman of "Mina" nation who sold foodstuff in the city market.<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":2">{{Cite book|title=Encyclopedia of emancipation and abolition in the Transatlantic world|others=Rodriguez, Junius P.,, Ackerson, Wayne|isbn=978-1317471790|location=London |oclc=908062295|date = 2015-03-26}}</ref> According to Gama, she was involved in a rebellion that may have been the ], which is why she had to eventually flee Bahia in 1837.<ref>Elciene Azevedo, Orfeu de carapinha: a trajetória de Luiz Gama na imperial cidade de São Paulo (Campinas: Editora da Universidade de Campinas, 1999), 68.</ref><ref name=":1" /><ref name=":2" /> | |||

| He was a black intellectual in 19th century ], the only self-taught and the only one to have gone through the experience of captivity. He spent his life fighting for the ] and for the end of the ], but died six years before these causes were accomplished.{{Sfn|Ferreira|2007}} In 2018 his name was inscribed in the Steel Book of national heroes deposited in the ].<ref name="Panteão">. ''UOL'', 04/07/2018</ref> | |||

| In 1840, when Gama was 10 years old, his papa sold him illegally, allegedly because of gambling debts.<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":1" /><ref name=":2" /> Gama never revealed the identity of his father to preserve his father's name after committing this injustice.<ref name=":1" /> Gama was first shipped to a port in ] and from there was taken to a province in ].<ref name=":1" /> Gama was bought by an '']'' named Antônio Pereira Cardoso.<ref name=":2" /> Cardoso would try to sell him, but no one would buy Gama, since he was originally from ], and Bahian slaves had the fame of being runaways.<ref name=":2" /> Cardoso then decided to use Gama as a housekeeper in his farm in the city of ]. | |||

| ==Panorama from the time== | |||

| In 1847, a law student named Antônio Rodrigues de Araújo stayed in Cardoso's house.<ref name=":1" /> He and Gama developed a strong friendship, and Araújo taught Gama how to read and write.<ref name=":2" /> Thus, Gama was able to understand the illegality of his condition, ran away from Cardoso, and regained his freedom in 1848.<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":2" /> | |||

| São Paulo, where Gama lived for forty-two years, was in the middle of the 19th century a still small provincial capital that, with the demand for coffee production from the 1870s on, saw the price of slaves reach a level that made their urban possession almost prohibitive. Until this period, however, it was quite common the property of "rent slaves", on whose work their owners drew their source of sustenance, alongside the so-called "domestic slaves".<ref name=clima/>{{efn|A good example of this were the seven spinster sisters of Marshal José Arouche de Toledo Rendon – Caetana, Gertrudes, Joaquina, Pulquéria, Leocádia, Ana Teresa and Reduzinda – who lived off the income obtained from the labor of 39 slaves.<ref name=clima/>}} | |||

| It had a population ten times smaller than that of the Court (]), and a very strong presence of legal culture because, since 1828, one of the only two law schools in the country had been established there, the ],{{efn|Mouzar Benedito work says that his attempt to study in university occurred in 1850, the year he got married.{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|p=23}}}} which received students from all over the country, coming from all social strata – besides the children of the rural ], members of the intellectual elite that was being formed at the time (Gama defined it, then, as "''Noah's Ark in a small way''").{{Sfn|Ferreira|2007}} | |||

| In 1858 Gama met Claudina Fortunata de Sampio and had a child with her a year after by the name of Benedito Graco Pinto de Gama.<ref name=":3">{{Cite journal|last=Kennedy|first=James H.|date=1974|title=Luiz Gama: Pioneer of Abolition in Brazil|jstor=2716766|journal=The Journal of Negro History|volume=59|issue=3|pages=255–267|doi=10.2307/2716766|s2cid=149563641}}</ref><ref name=":2" /> The godfather of his only son was Francisco Maria de Sousa Furtado de Mendonca. Mendonca, who was a big mentor for Gama and his law career.<ref name=":3" /> Since Gama and Sampio were freed slaves, they had to wait to register their marriage until 1869.<ref name=":3" /><ref name=":2" /> | |||

| ==Childhood and slavery== | |||

| Gama died in 1882 because of diabetes, with thousands of people mourning his death in São Paulo due to his role in the abolitionist movement and freeing more than one thousand slaves in ] through law.<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":3" /> | |||

| Luís Gama was born on June 21, 1830, at ''Bângala'' street Nº2,<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://istoe.com.br/86467_O+ADVOGADO+DOS+ESCRAVOS/|title=O advogado dos escravos|author=Eliane Lobato|date=2010-07-09|access-date=2021-08-24|language=pt-br}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://revistapesquisa.fapesp.br/escravo-e-abolicionista/|title=Escravo e abolicionista|author=Eduardo Nunomura|date=May 2014|access-date=2021-08-24}}</ref> in the centre from the city of Salvador, ]. Even with little information about his childhood, it is known that he was the son of ], a ] African ex-slave, and the son of a Portuguese ]{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|p=15}} who lived in Bahia. At the age of seven, his mother traveled to Rio de Janeiro to participate in the ] revolt, never to meet him again. In 1840, his father ended up in debt with ], so he resorted to selling Luís Gama as a ] to pay his debts.{{sfnm|1a1=Santos|1y=2014|1p=|2a1=Benedito|2y=2011|2p=16}} There is no evidence that his father sought him out after that.{{Sfn|dos Santos|2014|p=9}} As an adult, Gama understood that when he was sold he was a victim of the crime of "''Enslaving a free person, who is in possession of his freedom.''", provided in ] from ], sanctioned shortly after his birth.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.geledes.org.br/apos-ser-ilegalmente-escravizado-luiz-gama-fez-dos-jornais-seu-espaco-estrategico/|title=Após ser ilegalmente escravizado, Luiz Gama fez dos jornais seu espaço estratégico|date=2020-08-03|access-date=2021-08-26|language=pt-br}}</ref> Furthermore, due to the fact that the revolts that took place in Bahia led to the prohibition of the sale of slaves from this province to other regions of Brazil, the sale and transport of Luís Gama to São Paulo was constituted as contraband.{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|p=64}} | |||

| ], a type of sailing vessel in which Luís Gama traveled as a slave.|left]] | |||

| In an autobiographical letter he sent in 1880 to {{ill|Lúcio de Mendonça|pt|Lúcio de Mendonça}}, he describes his birth and early childhood thus: | |||

| {{Blockquote|I was born in the city of S. Salvador, capital of the Bahia province, in a two-story house at Bângala Street, forming an internal angle, in the "Quebrada", on the right side from the Palma churchyard, in the Sant'Ana parish, on June 21, 1830, at 7 in the morning, and I was baptized, eight years later, in the main church of Sacramento, in the city of ].{{Sfn|Ferreira|}}}} | |||

| Lígia Ferreira, one of the researchers who has most studied Gama's life, points out that this information could not be verified, although she stresses that the sobrado where he was born still exists; the register of his baptism could not be found, and adds to this the fact that the omission of his father's name from his account casts doubt on his real identity.{{Sfn|Ferreira|}}{{efn|There is, in the historical memory of Salvador, an enormous gap derived from the {{ill|Bombing of Salvador in 1912|pt|Bombardeio de Salvador em 1912|lt=bombing of the city}} in 1912 that, among other destruction's, burned the centuries-old documentation of what had been the first capital of Brazil.}} | |||

| Put up for sale, he was rejected "for being Bahian". After the ], a stigma was created that Bahian captives were rebellious and more likely to run away.<ref name=":0" /> He was taken to ] where he was sold to Antonio Pereira Cardoso, a ] who took him to be resold in ]. From the ], Gama and the other slaves were taken on foot to be sold in ] and ].{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|p=16}} With all the buyers resisting buying him because he was from Bahia, Gama began working as a domestic slave on the ]'s property, washing and ironing clothes, and then became a {{ill|Slave for hire|pt|Escravos de ganho|lt=slave for hire}}, working as a seamstress and shoemaker in the town of ].{{Sfn|Santos|2014}} | |||

| == Careers == | |||

| After regaining his freedom, Gama joined a military police force in 1848.<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":2" /><ref name=":3" /> After six years, Gama was discharged from the militia for insubordination as he admitted to threatening another officer who insulted him.<ref name=":3" /><ref name=":2" /> In addition to being discharged, Gama was also imprisoned for thirty-nine days for insubordination.<ref name=":3" /><ref name=":4">{{Cite journal|last1=Santos|first1=Eduardo Antonio Estevam|date=December 2015|title=Luiz Gama and the racial satire as the transgression poetry: diasporic poetry as counter-narrative to the idea of race|url=http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S2236-46332015000300707&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en|journal=Almanack|issue=11|pages=707–727|doi=10.1590/2236-463320151108|issn=2236-4633|doi-access=free}}</ref> After being discharged, Gama worked at the police station in São Paulo as a copyist and was eventually promoted to the police secretariat from 1856 to 1868.<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":3" /><ref name=":2" /><ref name=":4" /> However, when the Brazilian Conservative Party came into power Gama was dismissed.<ref name=":3" /> After his dismissal, Gama became an editor for ''O Piranga'', which was one of the most influential newspapers in Brazil at the time, where Gama published anti-slavery articles under a pseudonym.<ref name=":3" /> | |||

| ==Freedom and adulthood== | |||

| Gama worked a second job as a clerk in the private office of a high-ranking police officer by the name of Francisco Maria de Sousa Furtado de Mendonca, who eventually became a professor and dean at ].<ref name=":3" /><ref name=":2" /> This allowed Gama to study ] at the ], but did not finish the course.<ref name=":3" /><ref name=":1" /> In later life, he would work as a '']'', that is, a non-graduated lawyer with permission of the government to follow that career. | |||

| In 1847, Luís Gama had contact with a law student, Antônio Rodrigues do Prado Júnior, who stayed at his master's house and taught him the alphabet. The following year Gama was already literate and had taught the ensign's children to read, which he used as an argument in favor of his alforria, which was not successful.{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|p=19}} With this, Luís Gama was able to prove his freedom and joined the army in 1848. It remains unclear, however, the artifices used by Luis Gama to obtain his freedom,{{efn|Author Mouzar Benedito says that this is due to the fact that ] had decreed the destruction of all documentation relating to slavery.{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|p=20}}}} and it is suggested that he may have used the testimony of his father – whose identity he was careful to keep obscure.{{Sfn|Ferreira|}} There is also the theory that Gama would have run away from the estate and argued that he was free because he could read and write, which were skills that most slaves did not possess.{{Sfn|Santos|2014}} He was part of the City Guard from 1848{{Sfn|Kinsbruner|Langer|2008}} until 1854, when he was imprisoned for 39 days due to "insoburdination" after "threatening an insolent officer" who had insulted him. Before that, in 1850, he had married Claudina Fortunata Sampaio.{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|p=21}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Even while serving in the army, he was chosen to work as a copyist for official authorities in his spare time, since he had good calligraphy. In 1856, he was hired as a clerk at the São Paulo Police Department, in the office of Francisco Maria de Souza Furtado de Mendonça, a counselor and law professor. With the knowledge of Francisco Mendonça and having his library at his disposal, Luís Gama further studied the subject of law until he made the decision to graduate from the Largo de São Francisco Law School. However, the students of the Faculty were against it, making it impossible for Luís Gama to enroll, so he began to study on his own, as attending classes as a listener{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|p=23}} and became a "rábula", the name given to the individual who had enough legal knowledge to be a lawyer, even without a law degree.{{Sfn|Cruz|2014|pp=188–189}} After acting in slave cases, Gama was dismissed from his position at the Secretariat of Police, in 1868, due to pressure from {{ill|Conservative Decade (Brazil)|pt|Década Conservadora|lt=conservatives}} who were dissatisfied with the freedoms won by the rábula. Gama defined his dismissal "for the good of the public service" as a consequence of the work he had been doing to free slaves who were in an illegal situation, in addition to denouncing the system's abuses, or, in his words | |||

| {{Blockquote|the turmoil consisted in my being part of the Liberal Party; and, through the press and the ballot box, fighting for the victory of my and his ideas; and promoting lawsuits of free people criminally enslaved, and lawfully assisting, to the extent of my efforts, slave freedoms, because I detest captivity and all masters, especially kings.{{sfnm|1a1=Ferreira|1y=|1p=|2a1=Benedito|2y=2011|2p=24}}}} | |||

| ==Literature== | |||

| === Political career === | |||

| ].]] | |||

| Gama was an active opponent of Brazilian Monarchy and helped create the ] in 1873.<ref name=":3" /> Gama not only wanted to abolish slavery but also wanted Afro-Brazilians to actively participate in the abolitionist movement as well as the democratization of Brazil.<ref name=":3" /> However, Gama eventually denounced the group as some elite plantain owners who were members of the party wrote a manifesto asking for gradual emancipation and no punishment for slave owners.<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":3" /><ref name=":5">{{Cite journal|last=Braga-Pinto|first=César|date=2014-12-01|title=The Honor of the Abolitionist and the Shamefulness of Slavery Raul Pompeia, Luiz Gama, and Joaquim Nabuco|journal=Luso-Brazilian Review|language=en|volume=51|issue=2|pages=170–199|doi=10.1353/lbr.2014.0022|s2cid=143291913|issn=0024-7413}}</ref> | |||

| Gama was a reader of the ''Vida de Jesus'' (]), by the French philosopher ], originally published in 1863 and soon translated in Brazil, being one of the first to refer to it in the country.{{Sfn|Ferreira|2007}} His only work, originally published in two editions (1859 and 1861), ''Primeiras Trovas Burlescas'', placed him in the literary pantheon of Brazil only twelve years after he learned to read.{{Sfn|Ferreira|2007}} This book, dedicated to Salvador Furtado de Mendonça, a magistrate who taught at the Largo de S. Francisco and who also managed his library there (which allows us to infer that he facilitated Gama's access to his collection), also has poems by his friend ], attached.{{Sfn|Ferreira|2007}} The ] of the work only came out posthumously, in 1904.{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|p=24}} | |||

| ===Poetry: the "Orpheus with a curly top"=== | |||

| ==== Abolitionist ==== | |||

| Recalling the figure of the Greek poet Orpheus, and alluding to his curly hair, Gama was called "Orpheus with a curly top", and mastered both lyric and satirical poetry.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| As a lawyer, Gama defended blacks in court who were illegally enslaved, especially those who were enslaved after slave trade was abolished in 1831, and fought for their rights.<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":1" /><ref name=":3" /> Gama freed more than 500 slaves through the courts and also purchased the freedom of individual slaves.<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":1" /><ref name=":3" /> Not only did Gama use his knowledge of law to help slaves, but also promoted the abolitionist movement through lectures, journals, and by fundraising.<ref name=":1" /> As Gama established a positive reputation of being an attorney, he received funding from women's organizations and private sources for his anti-slavery stance.<ref name=":3" /> In 1881, the Luís Gama Emancipation Fund was created to help freedom for slaves.<ref name=":3" /> Additionally, Gama established the Abolitionist Center of São Paulo in 1882 and was the leader of the abolitionist movement in São Paulo.<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":1" /> | |||

| His poetics is written in the first person, without hiding his own origin and without failing to proclaim his blackness; at the same time, he does not fail to use the traditional images of his time, such as mythological evocations (like ], ], etc.) or the poets of the past (like ], ], for example).{{Sfn|Brandão|}} | |||

| === Literary career === | |||

| However, Gama reverts these images to his condition: the ] is from ], ] has "curly top". In portraying white society, he uses strongly ] images:{{Sfn|Brandão|}} | |||

| ==== Poetry ==== | |||

| {{Verse translation | |||

| Throughout Gama's careers, he would write in his free time for journals, newspapers, and eventually wrote his own books.<ref name=":3" /> In 1859, Gama published his first book ''Primeiras Trovas Burlescas de Getulino'' (''Getulino's First Burlesque Ballads''), under the pen name "Getulino."<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":3" /><ref name=":4" /> Most of the poems are satires about the customs of the 19th-century Brazilian Monarchist ] and also criticized ] society for their emphasis on pseudo-whiteness. Due to the success of his first book, Gama published a second edition of ''Primeiras Trovas Burlescas de Getulino'' in 1861. Through poetry Gama not only mocked racism in Brazil but also celebrated black beauty and the ] culture.<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":4" /> | |||

| | lang = pt | |||

| ] | |||

| | italicsoff = | |||

| | rtl1 = | |||

| | Com sabença profunda irei cantando | |||

| Altos feitos da gente luminosa, | |||

| (...) | |||

| Espertos manganões de mão ligeira, | |||

| Emproados juízes de trapaça, | |||

| E outros que de honrados têm fumaça, | |||

| Mas que são refinados agiotas. | |||

| | With deep wisdom I will sing | |||

| High deeds of the luminous people, | |||

| (...) | |||

| Clever manganese with a light hand, | |||

| And others who are honored with smoke, | |||

| And others who are honorable as smoke, | |||

| But who are refined loan sharks. | |||

| | attr1 = | |||

| | attr2 = | |||

| }} | |||

| ] | |||

| He builds, from the elements of white culture, the antithesis to the culture and civilization of the blacks, filling them with elements of traditional poetry; thus, he contrasts the "Guinea muse" to the Greco-Roman muses; the dark granite to the white marble; the marimba and the cabaço to the lyre and the flute:{{Sfn|Brandão|}} | |||

| {{Verse translation | |||

| | lang = pt | |||

| | italicsoff = | |||

| | rtl1 = | |||

| | Ó Musa da Guiné, cor de azeviche, | |||

| Estátua de granito denegrido, | |||

| (...) | |||

| Empresta-me o cabaço d'urucungo, | |||

| Ensina-me a brandir tua marimba (...) | |||

| | O Muse of Guinea, color of holly, | |||

| Statue of blackened granite, | |||

| (...) | |||

| Lend me your urucungo cabaço, | |||

| Teach me to wield your marimba (...) | |||

| | attr1 = | |||

| | attr2 = | |||

| }} | |||

| In his verses, he traces an image of himself that is far from the figure of the "poor wretch" or sufferer that figures in the blacks painted by contemporary white poets like ]. Gama hits himself with the same fierce criticism with which he attacks the system, belittling his own value before the prevailing cultural standards, which he implicitly accepts:{{Sfn|Brandão|}} | |||

| ==== Journalism ==== | |||

| {{Verse translation | |||

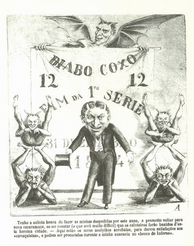

| During the 1860s Gama also became a journalist, collaborating with ] in ''Ipiranga'', ''Coroaci'' and ''O Polichileno''.<ref name=":4" /> Gama worked specifically as a typographer for ''Ipiranga'' and ''Coroaci.''<ref name=":4" /> He founded the journal ''Radical Paulistano'' in 1869 with other prominent abolitionists such as ], ], and ].<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":3" /> Gama also was the founder of a satirical journal by the name of Diablo Coxo, where he published political and social ] as well as anti-slavery ].<ref name=":3" /> Gama's political journalism heavily influenced the work and beliefs of ].<ref name=":5" />{{portal|Poetry}} | |||

| | lang = pt | |||

| | italicsoff = | |||

| | rtl1 = | |||

| | Se queres, meu amigo, | |||

| No teu álbum pensamento | |||

| Ornado de frases finas, | |||

| Ditadas pelo talento; | |||

| Não contes comigo, | |||

| Que sou pobretão: | |||

| Em coisas mimosas | |||

| Sou mesmo um ratão. | |||

| | If you will, my friend, | |||

| In your thought record | |||

| Ornamented with fine phrases, | |||

| Dictated by talent; | |||

| Don't count on me | |||

| That I am a penniless man: | |||

| In pampering things | |||

| I'm a real rat. | |||

| | attr1 = | |||

| | attr2 = | |||

| }} | |||

| Gama even ironizes the situation of the black man, cut off from wealth, the sciences, and the arts:{{Sfn|Brandão|}} | |||

| {{Verse translation | |||

| | lang = pt | |||

| | italicsoff = | |||

| | rtl1 = | |||

| | Ciências e letras | |||

| Não são para ti: | |||

| Pretinha da Costa | |||

| Não é gente aqui. | |||

| | Science and letters | |||

| Are not for you: | |||

| Little black girl da Costa | |||

| Isn't a person in this place. | |||

| | attr1 = | |||

| | attr2 = | |||

| }} | |||

| ===Goat=== | |||

| "Goat" (Bode) was a term used in Gama's time to make pejorative references to ] and ] people, more specifically, "gathering of mixed-race people",{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|p=25}} and the poet himself was the target of these offenses. Thus, in 1861, in the poem '']'' also known as ''Bodarrada'', Gama used the term ironically to satirize Brazilian society, while affirming human equality regardless of color:{{sfnm|1a1=Martins|1y=1996|1p=96|2a1=Oliveira|2y=2005|2pp=436–437}} | |||

| {{Verse translation | |||

| | lang = pt | |||

| | italicsoff = | |||

| | rtl1 = | |||

| | Se negro sou, ou sou bode, | |||

| Pouca importa. O que isto pode? | |||

| Bodes há de toda a casta. | |||

| Pois que a espécie é muita vasta... | |||

| Há cinzentos, há rajados, | |||

| Baios, pampas e malhados, | |||

| Bodes negros, bodes brancos, | |||

| Bodes ricos, bodes pobres, | |||

| Bodes sábios, importantes, | |||

| E também alguns tratantes… | |||

| Haja paz, haja alegria, | |||

| folgue e brinque a bodaria; | |||

| cesse, pois, a matinada, | |||

| porque tudo é bodarrada! | |||

| | Whether I am black, or a goat, | |||

| It matters little. What can it? | |||

| There are all kinds of goats. | |||

| For the species is very wide... | |||

| There are gray ones, and there are striped ones, | |||

| There's bays, pampas and spotted, | |||

| Black goats, white goats, | |||

| Rich goats, poor goats, | |||

| Wise goats, important goats, | |||

| And also some rascals... | |||

| Let there be peace, let there be joy, | |||

| Let there be peace, let there be joy, let there be fun and frolic; | |||

| So let the revelry cease, | |||

| because everything is bodarrada! | |||

| | attr1 = | |||

| | attr2 = | |||

| }} | |||

| ==Abolitionist activism== | |||

| ].|246x246px]] | |||

| ===Journalism and Freemasonry=== | |||

| Part of Luís Gama's abolitionist activism resided in his activity in the press. He began his journalistic career in São Paulo, together with cartoonist ]; both founded, in 1864, the first illustrated humorous newspaper in that city, called {{ill|Diabo Coxo|pt|Diabo Coxo}} (Lame Devil),<ref name=ltreso/> which lasted from October 1864 until November 1865.{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|p=30}} Before this, however, he had been an apprentice printer at ''O Ipiranga'' and had worked in the editorial staff of ''Radical Paulistano''.{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|p=29}} His actions as a journalist and lawyer, as early as 1869, had made him one of the most influential and popular figures in the city of São Paulo.{{Sfn|dos Santos|2014|p=4}} Despite this, Gama did not become a rich man and kept what little money he had to donate to the needy who came to him.{{Sfn|dos Santos|2014|p=6}} Luís Gama was the only black abolitionist in Brazil to have experienced slavery.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://pretapretopretinhos.blogfolha.uol.com.br/2020/07/21/ineditos-de-luiz-gama-saem-a-luz-e-ensinam-resistencia-na-imprensa-paulista-e-carioca/|title=Inéditos de Luiz Gama saem à luz e ensinam 'resistência' na imprensa paulista e fluminense|date=2020-06-21|access-date=2021-08-30|language=pt-br}}</ref> | |||

| But Gama also wrote articles for other newspapers, in which he discoursed on socio-racial issues of Imperial Brazil. In an article entitled ''Foro de Belém de Jundiaí'', published in {{ill|Radical Paulistano|pt|Radical Paulistano}}, Gama denounces the decision of a judge who, after the death of a slave master, allowed the auction of a former slave who had been freed by his heir son.{{Sfn|Santos|2014}} His journalistic and legal actions brought him many enemies, and the author Julio Emílio Braz even claims that ] was hired to assassinate him when Gama was nearing the end of his life,{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|p=33}} but a ] written to his son on September 23, 1870 makes it clear that he had been suffering threats against his life for some time.{{sfnm|1a1=Benedito|1y=2011|1pp=34–35|2a1=dos Santos|2y=2014|2pp=1–12}} | |||

| In 1866, still with Agostini, now joined by {{ill|Américo Brasílio de Campos|pt|Américo Brasílio de Campos}}, they founded the hebdomadário {{ill|Cabrião|pt|Cabrião}}; all three belonged to the same ], and shared the same ] and abolitionist ideals.<ref name="ltreso" /> The America Masonic Lodge was very active in the abolitionist cause; it was founded by Luís Gama and ] and ] (who omits his Masonic background) may also have been a member.{{Sfn|Ferreira|2007}} At the time of his death, Gama was the institution's Venerable Master.{{Sfn|Santos|2014}} | |||

| One of his projects within the freemasonry was, in June 1869, through the America Lodge and together with Olímpio da Paixão, the creation of a free school for children and an evening primary school for adults in the ''25 de Março'' Street.{{Sfn|dos Santos|2014|p=7}} Historian Bruno Rodrigues de Lima also found a manuscript that presents the idea that Gama had been responsible for the creation of a community library with 5 thousand titles, something that was attributed to the ''Loja América'', and his manifestos published in the newspaper "''Democracia''" demonstrate his commitment to a project of a public and secular school at least 30 years before the first debates on this subject.<ref name=Ined/> | |||

| ===The "Gama style" of judicial practice=== | |||

| ] | |||

| In 1831, a law was passed that prohibited the ], making any trafficked individual free as soon as he or she arrived in the country. Called the {{ill|Feijó Law|pt|Lei Feijó}}, it became better known as a {{ill|Law for the English to see|pt|Lei para inglês ver}}, because it was a law passed to appease British pressure for the abolition of slavery in Brazil, without actually putting an end to the importation of slaves. Although it was not a law enforced by slave traders, it was the legal instrument by which Gama used to achieve the liberation of slaves. The so-called "Gama style" consisted of proving through legal proceedings that the enslaved blacks defended by Gama were brought illegally to Brazil, that is, after the promulgation of the Feijó Law in 1831, and should therefore be freed.{{sfnm|1a1=Alonso|1y=2015|1p=58|2a1=Benedito|2y=2011|2pp=41–43}} | |||

| With the promulgation of the ] (Free Womb Law) in 1871, Gama was able to get more freed slaves. In one of the items of the law, it was established the requirement of registration of each slave that a master owned. If the slave did not have a registration, it could be used as an argument for his ], as Gama did. Also, article 4 of the law formalized the purchase of the slave's manumission charter by the slave himself or by others, which allowed abolitionists to pass themselves off as slave valuers and lower the purchase price, allowing Gama and other abolitionists to buy more freedoms at lower prices.{{Sfn|Alonso|2015|p=59}} | |||

| Although he acted mainly in the defense of blacks accused of crimes, of those who fled or to seek their legal freedoms, he did not refuse to attend gracefully to the poor of any ethnicity, and there were cases in which he defended European immigrants injured by Brazilians.<ref name=":0" /> Gama also helped newly freed slaves find a job.{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|p=49}} | |||

| In his autobiographical letter to Lúcio de Mendonça, Gama estimates that he had already freed more than 500 slaves from captivity{{Sfn|Ferreira|}} and in an 1869 court case known as the "]", Gama secured the freedom of 217 slaves, in an act regarded as the "largest known collective action to free slaves in the Americas," according to the BBC.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/brasil-57014874|title=Luiz Gama: A desconhecida ação judicial com que advogado negro libertou 217 escravizados no século 19|author=Leandro Machado|newspaper=BBC News Brasil|date=2021-05-08|access-date=2021-08-22|language=pt-br}}</ref> | |||

| During a jury, Gama uttered a phrase that became famous: ''The slave who kills the master, in whatever circumstance, always kills in self-defense'' – this provoked such a reaction from those present that, with the confusion, the judge was forced to suspend the session.<ref name="globo" /> Historian Ligia Fonseca Ferreira says that this phrase actually appeared in the biography of Luís Gama written by Lúcio de Mendonça and published in the Almanaque Literário de São Paulo, explaining that "This phrase is not by Luiz Gama, it is by this white friend who wrote about him".<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.brasildefato.com.br/2018/05/17/obra-de-luiz-gama-revela-a-luta-do-abolicionista-por-uma-terra-sem-rei-e-sem-escravo/|title=Obra de Luiz Gama revela a luta por um Brasil sem reis ou escravos|author=Juliana Gonçalves|date=2018-05-17|access-date=2021-08-21|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210820210020/https://www.brasildefato.com.br/2018/05/17/obra-de-luiz-gama-revela-a-luta-do-abolicionista-por-uma-terra-sem-rei-e-sem-escravo/|archive-date=2021-08-20|url-status=live|language=pt-br|quote=É neste texto sobre o abolicionista que Mendonça inclui a frase que mais tarde foi creditada a Gama: "o escravo que mata seu senhor, em qualquer circunstância, o faz sempre em legítima defesa". Para Lígia, a falta de conhecimento sobre o autor ajudou a espalhar essa frase como sendo de Gama. "Esta frase não é do Luiz Gama, ela é desse amigo branco que escreveu sobre ele", explica.<br />A pesquisadora conta que seria muito complicado pelo trânsito de Gama entre abolicionistas e republicanos sustentar essa frase desse modo, embora sua literatura seja revolucionária ao propor a ruptura do Império e a liberdade dos negros.}}</ref> An article in the Estado de São Paulo also says that Gama never wrote these words in exact, and historian Bruno Rodrigues de Lima says that this concept reappears several times in his work.<ref name=FSPiV>{{Cite web|url=https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/ilustrada/2021/08/luiz-gama-textos-ineditos-mostram-como-abolicionista-denunciava-violencia-policial-no-seculo-19.shtml|title=Luiz Gama: textos inéditos mostram como abolicionista denunciava violência policial no século 19 |author=Leandro Machado|date=2021-08-04|access-date=2021-08-22|language=pt-br}}</ref> In one example, in the Letter to Ferreira de Menezes dated December 18, 1880, when defending 4 slaves considered "four ]" by Gama, who had murdered the son of their master Valeriano José do Vale, and had been executed by 300 people while inside the prison by "...the knife, the stick, the hoe, the axe...", Gama said:{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|pp=51–52}} | |||

| {{Blockquote|...the slave who kills the master, who fulfills an inevitable prescription of natural right, and the unworthy people who murder heroes, will never be mixed.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.terra.com.br/noticias/brasil/cidades/leia-artigo-de-luiz-gama-publicado-ha-mais-de-140-anos-nas-paginas-do-estadao,485cd1140aa76f47eaa96f54c94838c1cbvphvkl.html|title=Leia artigo de Luiz Gama publicado há mais de 140 anos nas páginas do Estadão|language=pt-br|date=2021-06-11|access-date=2021-08-29|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210829134919/https://www.terra.com.br/noticias/brasil/cidades/leia-artigo-de-luiz-gama-publicado-ha-mais-de-140-anos-nas-paginas-do-estadao,485cd1140aa76f47eaa96f54c94838c1cbvphvkl.html|archive-date=2021-08-29|url-status=live}}</ref>{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|pp=51–52}}}} | |||

| An equivalent sentence was published on August 19, 1882 as the subtitle of the article "To the slavocrats", written by Raul Pompeia, in the Abolitionist Center's newspaper "''ÇA IRA''": "Before the Law, the crime of homicide perpetrated by the slave in the person of the master is justifiable".{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|p=59}} | |||

| ====Ethnic views==== | |||

| Luís Gama was against African descendants who acted like whites or even became cruel slavers, and he thought it was funny to see slavers of ] trying to pass themselves off as whites. About his father, he said, "My father, I dare not claim that he was white, because such claims, in this country, constitute grave danger before the truth".{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|p=55}} Colonel Teodoro Xavier hated Luís Gama for having already lost a slave to him, so he called him "]", trying to insult him, to which one day, the lawyer replied: "I am not a goat, I am black. My color does not deny it. A goat is your honor who intends to disguise, with this light color, the ] underneath".{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|p=56}} | |||

| ===Political activity=== | |||

| In his political activities Gama was affiliated to ] and before the {{ill|Republican Manifesto|pt|Manifesto Republicano}} he had already exposed his ideas in the article "''The ] and the lands of ] without king or slaves''" published on December 2, 1869. Later, Gama was part of the group that for the first time tried to found a republican party{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|p=37}} and on July 2, 1873, he came to participate in the First Republican Congress, already part of the ], where he found that the party and its members, many slave owners, did not care or interest themselves in the abolitionist agenda.{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|p=38}} Because he believed that abolition should be immediate and without compensation to the slaveholders, he left the party and started criticizing it in the media, and these criticisms also extended to newspapers that claimed to be in favor of the abolitionist cause, but published advertisements about the capture of slaves.{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|p=39}} | |||

| ==Death and burial== | |||

| The writer ] had already noticed that Gama's health was not good; three days before his death he had observed that Gama no longer climbed down the stairs of his office without support, resorting to the support of his friends Pedro, Brasil Silvado, or himself, Raul.{{Sfn|Santos|2014}} | |||

| Gama had ]. On the morning of August 24, 1882 he had lost his speech and despite the intervention of more than 20 doctors, this was the '']'' that victimized him that afternoon,{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|p=57}} certified by physician Jaime Perna.<ref name=loja/> | |||

| When the great abolitionist and slave liberator had died, Raul Pompeia expressed his incredulity and, registering every moment of the funeral, he immediately went to his friend's house, where he verified that many people were already there, keeping vigil: in front of the house, men cried "like cowards", and ladies sobbed. His body had been placed in a coffin in the front room; a sculptor molded his face in plaster. The coffin left the next day at three o'clock in the afternoon. Just before the coffin was closed, the widow gave a painful cry. The cemetery was at the other end of town, and a funeral coach had been prepared to take him, but the crowd of people who had flocked there would not let him go: "Everyone's friend" – as he was known – would have to be "carried by everyone".{{Sfn|Santos|2014}} Commerce had closed its doors and flowers were thrown to Gama.{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|p=58}} | |||

| The coffin appears, brought by friends of the deceased: journalist and member of the Centro Abolicionista Gaspar da Silva, Dr. Antônio Carlos, Dr. Pinto Ferraz, {{ill|Manuel Antônio Duarte de Azevedo|pt|Manuel Antônio Duarte de Azevedo|lt=Conselheiro Duarte de Azevedo}}, among others; ahead of the coffin followed a huge crowd, like the one squeezed in beside, disputing the honor of carrying the coffin; behind, a large number of carriages and, among them, the empty funeral coach. At four hours and five minutes, the procession arrived at ], where a band was waiting to accompany it, playing sad chords; at {{ill|Convento do Carmo de São Paulo|pt|Convento do Carmo de São Paulo|lt=Ladeira do Carmo}}, the Brotherhood of Nossa Senhora dos Remédios joined the burial; arriving at the "city", stores closed their doors and flags were flying at half-mast, while people crowded the streets where the burial was to take place; in the windows, families squeezed themselves to watch: all along the way, many mourned the loss.{{Sfn|Santos|2014}} | |||

| Professor Otávio Torres recorded that Luís Gama died "glorified by São Paulo"; Antônio Loureiro de Sousa, in 1949, recorded: "His funeral was an unprecedented spectacle: it was the largest ever reported in those days. The crowd that followed the funeral cortege, with all silence and admiration, was forced to stop by the numerous speeches that interrupted the funeral procession".<ref name="als" /> More recently, in 2013, article writer Zeca Borges declared that "his burial was the most emotional event in the history of the city of São Paulo".<ref name="globo">{{cite web|url=http://oglobo.globo.com/rio/ancelmo/zeca/posts/2012/11/16/luiz-gama-filho-de-luiza-mahin-474959.asp |title=Luis Gama – O filho de Luisa Mahin |author=Zeca Borges |date=2013-11-20 |work=Globo.com |access-date=2013-11-29|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181211055612/https://blogs.oglobo.globo.com/ancelmo/zeca/posts/2012/11/16/luiz-gama-filho-de-luiza-mahin-474959.asp|archive-date=2018-12-11|url-status=dead|language=pt-br}}</ref> | |||

| People of all classes were there, and all vying for the chance to carry the skiff. At one point, the slave driver {{ill|Martinho Prado Júnior|pt|Martinho Prado Júnior}} carried on one side, and on the other, a haughty, "poor, ragged, barefooted black man", in Pompey's register. It was already evening when the procession finally arrived at the Consolação holy ground, and the crowd held its ground. After a brief stop for a sermon by a priest in the chapel, where the hundreds of wreaths of flowers were laid, the coffin was finally taken to the grave, where the crowd was waiting. Before lowering it, however, someone – the doctor {{ill|Clímaco Barbosa|pt|Clímaco Barbosa}} or {{ill|Antônio Bento|pt|Antônio Bento (abolicionista)}}, shouted for everyone to wait; after a brief speech in which he remembered the importance of Luís Gama, bringing everyone to tears, he summoned everyone to swear an oath not to let "die the idea for which that giant had fought": this was answered by a general roar from the crowd, which, hands extended to the coffin, swore.{{sfnm|1a1=Santos|1y=2014|1p=|2a1=Benedito|2y=2011|2p=58}} | |||

| His grave was purchased on the same day as the burial in the name of his wife Claudina, as recorded in Book 2, fols. 28, of the Municipal Archives; it is located on 2nd Street, grave 17.<ref name=loja/> | |||

| ===Effects from the speeches=== | |||

| Gama's death and the engaged speech at his grave marked the end of this first phase of the abolitionist movement, markedly "legalistic" (constitution of funds for the acquisition of captives and their freedom, legal actions for liberation) and the beginning of the phase of effective actions to combat the slavers: led by Clímaco Barbosa, the campaign moved on to "de facto ways", where people took in runaway slaves, hiding them in their homes until they were sent to the Quilombo do Jabaquara, in Santos, and stimulating mass escape from the farms.<ref name=clima>{{cite web|url=http://historia.fflch.usp.br/sites/historia.fflch.usp.br/files/SPEscrav.pdf |title=Sendo Cativo nas Ruas: a Escravidão Urbana na Cidade de São Paulo |author=Maria Helena P. T. Machado |year=2004 |work=História da Cidade de São Paulo, (Paula Porta, org.), São Paulo: Paz e Terra, p. 59–99 |access-date=2013-11-25|language=pt-br}}</ref> | |||

| A milestone of this action was the invasion of Chácara Pari by members of the Brás Abolitionist Club, with cries of "Long live the abolitionists, let the slavocrats die!"; people such as Barbosa, Antônio Bento, Feliciano Bicudo, among other notables and anonymous, became part of the police's list of suspects.<ref name=clima/> | |||

| In 1879, recognizing that his illness was worsening, Luís Gama began to consider radical methods and Antônio Bento, who had left his position as a judge to dedicate himself to the anti-slavery struggle was of paramount importance in this area and was later considered "the ghost of abolition".{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|pp=58–59}} Antônio Bento inherited the position of lawyer for the Abolitionist Club upon Gama's death. Later came the Abolitionist Party and the Caifazes movement,{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|p=59}} led by Antônio Bento, who radicalized the abolitionist campaign in actions as described in the first paragraph of the topic, which made Antônio Bento the immediate continuator of Luís Gama's work.{{Sfn|Benedito|2011|p=60}} | |||

| ==Homages and influences== | |||

| ] | |||

| Among his contemporaries Gama was the recipient of several tributes. ], in the {{ill|Gazeta de Notícias|pt|Gazeta de Notícias}} of September 10, 1882, wrote an article about him entitled ''Última página da vida de um grande homem'' (Last page in the life of a great man); the same author wrote a caricature of him, which was published that same year on the front page of the Rio de Janeiro newspaper O Mequetrefe in August (No. 284), and also the unfinished novella ''A Mão de Luís Gama'' (The Hand of Luís Gama), originally published on the pages of the Jornal do Commercio, of São Paulo (1883), and the text ''A Morte de Luíz Gama'' (The death of Luíz Gama).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://objdigital.bn.br/acervo_digital/div_iconografia/icon1285832.pdf |title=Exposição comemorativa do centenário de nascimento de Raul Pompeia |author=Biblioteca Nacional do Rio de Janeiro |year=1963 |work=Ministério da Educação e Cultura |access-date=2013-11-25|language=pt-br}}</ref>{{efn|The last two full texts can be read in: Schmidt, Afonso. O Canudo. S. Paulo, Clube do Livro, 1963 – p. 83-136.}} | |||

| Some years after his death, and following the Abolition, the ''Luís Gama Lodge'' was founded by the São Paulo Freemason Góes and the collaboration of brothers from the ''Trabalho and Ordem e Progresso'' lodges, with the initiation of 25 blacks.<ref name=loja>{{cite web |url=http://lojaluizgama.com.br/pagina.php?IdPagina=4&Site=Site |title=Loja Luís Gama |author=Institucional |work=Sítio oficial da entidade |access-date=2013-11-25 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140202130300/http://lojaluizgama.com.br/pagina.php?IdPagina=4&Site=Site |archive-date=2014-02-02 |url-status=dead|language=pt-br}}</ref> | |||

| In his honor, in 1919, the {{ill|Sorocabana Railroad|pt|Estrada de Ferro Sorocabana}} (currently ] named one of its stations, today practically in ruins.{{Need citation|date=August 2021}} | |||

| Between 1923 and 1926, in what may be considered the "second period of the black press" in the state of São Paulo, the newspaper Getulino appeared in the city of Campinas; in this city racism was stronger than in the state capital itself, and the publication was part of the movement for greater participation of blacks in society; its title was a "tribute to Luís Gama who had as one of his pseudonyms Getulino" and its influence would culminate in the creation of ''O Clarim da Alvorada'', a newspaper in the São Paulo capital.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Ferrara |first=Mirian Nicolau |year=1985 |title=A imprensa negra paulista (1915/1963) |url=http://www.anpuh.org/arquivo/download?ID_ARQUIVO=3609 |journal=Rev. Bras. De Hist. |volume=5 |number=10 |pages=197–207 |access-date=2013-11-23|language=pt-br }}</ref> | |||

| In ], in São Paulo, there is a {{ill|Luiz Gama (Yolando Mallozzi)|pt|Luiz Gama (Yolando Mallozzi)|lt=bust}} erected to his memory,{{Sfn|Ferreira|}} erected on commission by the black community on the occasion of his centennial.<ref name="ltreso">{{cite web |url=http://escoladegoverno.org.br/attachments/2097_Aula%202%20-%2007-08%20-%20Luis%20Gama%20e%20a%20Escravid%C3%A3o%20no%20Brasil%20-%20Ligia%20Fonseca%20Ferreira.doc |title=2012, 130º Aniversário de falecimento Luís Gama (1830–1882): de escravo a "cidadão" |author=Lígia Fonseca Ferreira |year=2012 |access-date=2013-11-25|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131202231442/http://escoladegoverno.org.br/attachments/2097_Aula%202%20-%2007-08%20-%20Luis%20Gama%20e%20a%20Escravid%C3%A3o%20no%20Brasil%20-%20Ligia%20Fonseca%20Ferreira.doc |archive-date=2013-12-02 |url-status=dead|language=pt-br }}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Over time it influenced several black Brazilian movements, such as the literary group ''Projeto Rhumor Negro'' of São Paulo, created in 1988, for whom Gama's letter to Mendonça is "one of the most important historical documents of the Brazilian people. (...) Given the magnitude of the life of this great man, this letter, crossing time, is also addressed to all of us".{{Sfn|Ferreira|}} | |||

| In 2014, in the wake of the success of the movie ], writer ], author of the novelized work about Gama's life ''Um Defeito de Cor'' (A Color Defect), prepared a script for a movie and also drawing the attention of Brazilian television – pointing out that very little is said about slavery compared to other historical facts, such as the holocaust during ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/ilustrada/2014/03/1422176-series-e-filme-vao-contar-a-historia-do-abolicionista-baiano-luiz-gama.shtml |title=Séries e filme vão contar a história do abolicionista baiano Luís Gama |date=2014-03-08 |access-date=2014-03-08 |work=Ilustrada – Folha de S. Paulo |author=Sylvia Colombo|language=pt-br}}</ref> In 2015 the play "''Luiz Gama — Uma voz pela liberdade"'' ("Luiz Gama – A Voice for Freedom") was started, with actor and scriptwriter Deo Garcez as the protagonist and actress Nivia Helen as narrator and various characters.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://oglobo.globo.com/rioshow/lider-abolicionista-luiz-gama-tema-de-peca-de-sucesso-24089259|title=Líder abolicionista Luiz Gama é tema de peça de sucesso|author=Gustavo Cunha|date=2019-11-20|access-date=2021-08-25|language=pt-br}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://redeglobo.globo.com/globoteatro/noticia/deo-garcez-protagoniza-espetaculo-luiz-gama-uma-voz-pela-liberdade.ghtml|title=Déo Garcez protagoniza espetáculo 'Luiz Gama – Uma Voz Pela Liberdade'|date=2018-05-01|access-date=2021-08-25|language=pt-br}}</ref> | |||

| In 2015, the ] conceded the title of attorney of law to Luis Gama in a ceremony in the Law School of ]. This homage was proposed by Professor ], President of Luiz Gama Institute, and nowadays ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.conjur.com.br/2015-nov-04/133-anos-morte-luiz-gama-recebe-titulo-advogado|access-date=2023-10-02 | website=Conjur |language=pt-br |title=Após 133 anos de sua morte, Luiz Gama recebe título de advogado |date=4 November 2015 }}</ref> | |||

| In 2017, the ], in ], named one of its rooms after him.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.oabsp.org.br/noticias/2017/12/luiz-gama-ganha-nome-em-sala-na-usp-por-sua-luta-pela-libertacao-de-escravos.12127 |title=Luiz Gama ganha nome em sala na USP por sua luta pela libertação de escravos |access-date=2020-09-18 |website=OAB SP |language=pt-br}}</ref> In 2018 his name was inscribed in the Steel Book of national heroes deposited in the ]<ref name="Panteão"/> and was recognized as a journalist by the {{ill|São Paulo Journalists Union|pt|Sindicato dos Jornalistas de São Paulo}}.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.istoedinheiro.com.br/luiz-gama-e-redescoberto-pelas-novas-geracoes/|title=Luiz Gama é redescoberto pelas novas gerações|date=2021-07-11|access-date=2021-08-24|language=pt-br}}</ref> | |||

| In 2019, it was announced that filmmaker {{ill|Jefferson De|pt|Jeferson De}} would make a film on the life of Gama, with {{ill|Fabrício Boliveira|pt|Fabrício Boliveira}} as the character in adulthood. The film, then in production, was temporarily titled ''Prisioneiro da Liberdade'' (Prisoner of Liberty), also would feature actors Caio Blat and Zezé Motta.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://cineweb.com.br/noticias/noticia.php?id_noticia=4660 |title=Fabricio Boliveira interpretará Luiz Gama em novo filme de Jefferson De |date=2018-11-22 |access-date=2018-11-22|work=Cineweb|language=pt-br}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.adorocinema.com/filmes/filme-269750/ |title=Prisioneiro da Liberdade |date=2019 |work=Adoro Cinema |access-date=2020-04-27}}</ref> The name of the film came to be ], with {{ill|César Mello|pt|César Mello}} as the main character, and was released in 2021.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.omelete.com.br/filmes/criticas/doutor-gama-critica|title=Crítica – Doutor Gama acerta a narrativa sem espetacularizar sofrimento negro|date=2021-08-05|access-date=2021-08-20|author=Pedro Henrique Ribeiro|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210815120502/https://www.omelete.com.br/filmes/criticas/doutor-gama-critica|archive-date=2021-08-15|url-status=live|language=pt-br}}</ref> | |||

| Also in 2019, the comic book ''Província Negra'' was published after winning the city of São Paulo's ''Fomento Cultural'' edict, portraying a fictional adventure based on the life of Gama, who takes on the role of the protagonist in the adventure. The script is by Kaled Kanbour and the art by Kris Zullo.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://mundonegro.inf.br/em-provincia-negra-luiz-gama-vira-personagem-de-historia-em-quadrinhos/ |title=Em Província Negra, Luiz Gama vira personagem de história em quadrinhos |date=2019-05-14|work=Mundo Negro |access-date=2020-04-27|language=pt-br}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://midia4p.cartacapital.com.br/hq-sobre-advogado-baiano-e-abolicionista-luiz-gama-e-lancada-em-sao-paulo/ |title=HQ sobre personagem baiano e abolicionista Luiz Gama é lançada em São Paulo |date=2020-02-12 |work=Carta Capital |access-date=2020-04-27 |language=pt-br |archive-date=2021-06-02 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210602214311/https://midia4p.cartacapital.com.br/hq-sobre-advogado-baiano-e-abolicionista-luiz-gama-e-lancada-em-sao-paulo/ |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| In 2021, the University of São Paulo posthumously awarded him an ] doctorate,<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.brasildefato.com.br/2021/07/01/usp-concede-titulo-de-doutor-honoris-causa-postumo-a-luiz-gama|title=USP concede título de doutor "honoris causa" póstumo a Luiz Gama|date=2021-06-01|access-date=2021-08-24|language=pt-br}}</ref> the first black Brazilian to receive this title from the university.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://g1.globo.com/sp/sao-paulo/noticia/2021/06/29/usp-concede-pela-1a-vez-titulo-de-doutor-honoris-causa-a-um-brasileiro-negro-homenageado-e-o-abolicionista-luiz-gama.ghtml|title=USP concede, pela 1ª vez, título de Doutor Honoris Causa a um brasileiro negro; homenageado é o abolicionista Luiz Gama |date=2021-06-29|access-date=2021-08-24|language=pt-br}}</ref> | |||

| ===Title of "lawyer"=== | |||

| 133 years after his death, on November 3, 2015, the ], São Paulo Section, granted him the title of "lawyer", since he was not trained and acted as a "provisioned" or abolitionist. The tribute ceremony, entitled "Luiz Gama: Ideas and Legacy of the Abolitionist Leader", included two days of events at ], through debates and lectures. The tribute is unprecedented in the history of the Order of Attorneys of Brazil; according to its national president, {{ill|Marcus Vinicius Furtado Coêlho|pt|Marcus Vinicius Furtado Coêlho}}, "It is a very fitting tribute to someone who fought so hard for freedom, equality, and respect".<ref name="nov">{{cite web |url=http://sao-paulo.estadao.com.br/blogs/edison-veiga/luiz-gama-1830-1882-enfim-advogado/ |title=Luiz Gama (1830–1882): enfim, advogado |date=2015-10-30 |access-date=2015-11-03 |work=O Estado de São Paulo |author=Edison Veiga|language=pt-br}}</ref> | |||

| ===Image Abroad=== | |||

| The Black Past website, focused on global African and African American history, has a page with the poet's biography.<ref>{{cite web |last=Foster |first=Hannah |url=https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/gama-luis-1830-1882/ |title=Luis Gama (1830–1882) |date=2014-04-02 |access-date=2021-06-02 |work=Black Past |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| In March 2020, the workshop "Slavery, Freedom and Civil Law in the Brazilian Courts (1860–1888): How the Black Lawyer Luiz Gama Developed a Legal Doctrine that Freed Five Hundred Slaves" took place at ].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://history.princeton.edu/news-events/events/latin-america-caribbean-workshop-slavery-freedom-and-civil-law-brazilian-courts |title=Latin America & Caribbean Workshop |work=Princeton University |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ==Complete work== | |||

| Historian Bruno Rodrigues de Lima, from the ],<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://veja.abril.com.br/cultura/o-resgate-da-obra-de-luiz-gama-de-ex-escravo-a-advogado-abolicionista/|title=O resgate da obra de Luiz Gama, de ex-escravo a advogado abolicionista|date=2021-06-14|access-date=2021-08-21|language=pt-br}}</ref> spent nine years going through archives and registry offices looking for the complete works of Luís Gama, in a project for the publication of ten volumes and approximately 5,000 pages in Portuguese entitled ''Obras Completas'' , alongside the publisher Hedra.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://domtotal.com/noticia/1534558/2021/08/obras-completas-do-advogado-poeta-e-jornalista-luiz-gama-enfim-e-editada/|title=Obras completas do advogado, poeta e jornalista Luiz Gama, enfim, é editada|date=2021-08-19|access-date=2021-08-21|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210821171301/https://domtotal.com/noticia/1534558/2021/08/obras-completas-do-advogado-poeta-e-jornalista-luiz-gama-enfim-e-editada/|archive-date=2021-08-21|url-status=live|language=pt-br}}</ref> The project, published out of order, will be fully released by 2022.<ref name=Ined>{{Cite web|url=https://oglobo.globo.com/cultura/luiz-gama-ganha-cinebiografia-edicao-de-suas-obras-completas-recheadas-de-ineditos-25140375|title= Luiz Gama ganha cinebiografia e edição de suas obras completas recheadas de inéditos |date=2021-08-05|access-date=2021-08-30|language=pt-br}}</ref> | |||

| Bruno Rodrigues has researched to create Luís Gama's timeline starting when he published his first text at the age of 19, and among his research findings is the fact that he was already recognized as a lawyer in his time, not a rábula- and that this denomination may have been created to diminish him.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.dw.com/pt-br/documentos-in%C3%A9ditos-confirmam-que-luiz-gama-era-advogado/a-59756876|title=Documentos inéditos confirmam que Luiz Gama era advogado|website=] |date=2021-11-08|access-date=2021-11-12|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211108151136/https://www.dw.com/pt-br/documentos-in%C3%A9ditos-confirmam-que-luiz-gama-era-advogado/a-59756876|archive-date=2021-11-08|url-status=live|language=pt-br}}</ref> | |||

| *{{Cite book|url=|title=Democracia (1866–1869)|author=Luiz Gama|editor=Bruno Rodrigues de Lima|publisher=Hedra|year=2021|isbn=9786589705123|pages=500|volume=4|edition=1|series=Obras Completas|language=pt-br}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|url=|title=Direito (1870–1875)|author=Luiz Gama|editor=Bruno Rodrigues de Lima|publisher=Hedra|year=2023|isbn= 978-8577157341|pages=486|edition=1|volume=5|series=Obras Completas|lang=pt-br}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|url=|title=Crime (1877–1879)|author=Luiz Gama|editor=Bruno Rodrigues de Lima|publisher=Hedra|year=2023|isbn=978-8577157334|pages=380|edition=1|volume=7|series=Obras Completas|lang=pt-br}} | |||

| *{{Cite book|url=|title=Liberdade (1880–1882)|author=Luiz Gama|editor=Bruno Rodrigues de Lima|publisher=Hedra|year=2021|isbn=9786589705161|pages=446|volume=8|edition=1|series=Obras Completas|language=pt-br}} | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| {{Notes}} | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{Reflist}} | {{Reflist|30em}} | ||

| ==See also== | |||

| *] - 2021 Brazilian biographical movie. | |||

| ==Bibliography== | ==Bibliography== | ||

| === Scientific papers === | |||

| * Azevedo, Elcinene. ''Orfeu de carapinha: a trajetória de Luiz Gama na imperial cidade de São Paulo.''Campinas: Editora da Universidade de Campinas, 1999. | |||

| * Azevedo, Elciene. ''O direito dos escravos: lutas jurídicas e abolicionismo na província de São Paulo''. Campinas, SP, Brasil: Editora Unicamp, 2010. | |||

| * {{cite journal |last=Brandão |first=Roberto de Oliveira |date= |title=A Poesia Satírica de Luís Gama |url=http://www.letras.ufmg.br/literafro/data1/autores/96/luizgamacritica01.1.pdf |journal=Boletim bibliográfico – Biblioteca Mario de Andrade |volume=49 |number=1/4 |pages=8 |doi= |access-date=2013-11-27|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140204012853/http://www.letras.ufmg.br/literafro/data1/autores/96/luizgamacritica01.1.pdf |archive-date=2014-02-04 |url-status=dead|language=pt-br }} | |||

| *Braga-Pinto, César,"The Honor of the Abolitionist and the Shamefulness of Slavery: Raul Pompeia, Luís Gama and Joaquim Nabuco." Luso-Brazilian Review. 51(2), Dec. 2014. 170-199. | |||

| * {{Cite journal|url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/43905328 |title=The Honor of the Abolitionist and the Shamefulness of Slavery: Raul Pompeia, Luís Gama and Joaquim Nabuco |journal=Luso-Brazilian Review <!--|work=University of Wisconsin Press--> |number=2 |last=Braga-Pinto |first=César |year=2014 |language=en |volume=51|pages=170–199 |doi=10.1353/lbr.2014.0022 |jstor=43905328 |s2cid=143291913 }} | |||

| * GAMA, Luís. ''Primeiras Trovas Burlescas de Getulino e Outros Poemas'' (edited by Lígia Ferreira). São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2000. | |||

| * {{Cite journal |url=http://e-revista.unioeste.br/index.php/travessias/article/view/9737 |title=A trajetória social e educacional do abolicionista Luís Gama: notas e anotações para a História da Educação brasileira. |date=2014 |journal=Travessias Revista <!--|work=Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Paraná--> |number=2 |last=Cruz |first=Ricardo Alexandre |volume=8|language=pt-br}} | |||

| * SILVA, J. Romão. ''Luís Gama e Suas Poesias Satíricas''. Rio de Janeiro: Casa do Estudante. | |||

| * {{Cite journal |url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/2716766 |title=Luiz Gama: Pioneer of Abolition in Brazil |date=1974 |journal=The Journal of Negro History <!--|work=Association for the Study of African American Life and History--> |number=3 |last=Kennedy |first=James H |language=en |volume=59|pages=255–267 |doi=10.2307/2716766 |jstor=2716766 |s2cid=149563641 }} | |||

| * {{Cite journal |title=Luiz Gama autor, leitor, editor: revisitando as Primeiras Trovas Burlescas de 1859 e 1861 |date=2019 |journal=Estudos Avançados |number=96 |last=Ferreira |first=Lígia Fonseca |volume=33|pages=109–136 |doi=10.1590/s0103-4014.2019.3396.0008 |language=pt-br|doi-access=free }} | |||

| * {{cite journal|last=Ferreira |first=Ligia Fonseca |date=2007 |title=Luiz Gama: um abolicionista leitor de Renan |journal=Estud. Av. |volume=21 |number=60 |pages= 271–288|doi=10.1590/S0103-40142007000200021 |language=pt-br|doi-access=free }} | |||

| * {{cite journal |last=Ferreira |first=Ligia Fonseca |date= |title=Luiz Gama por Luiz Gama: carta a Lúcio de Mendonça |url=http://www.letras.ufmg.br/literafro/data1/autores/96/luizgamacritica03.pdf |journal=Teresa. Revista de Literatura Brasileira da USP |volume= |number=8/9 |pages=300–321 |doi= |access-date=2013-11-24|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140204012849/http://www.letras.ufmg.br/literafro/data1/autores/96/luizgamacritica03.pdf|archive-date=2014-02-04|url-status=dead|language=pt-br}} | |||

| * {{Cite journal |url=https://periodicos.ufba.br/index.php/afroasia/article/view/20858 |title=Luis Gama e a consciência negra na literatura brasileira |date=1996 |access-date=2021-06-01 |journal= Afro-Ásia| publisher=Universidade Federal da Bahia |number=17 |last=Martins |first=Heitor|doi=10.9771/aa.v0i17.20858 |language=pt-br |doi-access=free }} | |||

| * {{Cite journal |url=https://revistas.iel.unicamp.br/index.php/sinteses/article/view/6351 |title=Luiz Gama, o poeta invísivel |date=2005 |access-date=2021-06-01|journal=Sínteses <!--|work=Universidade Estadual de Campinas--> |last=Oliveira |first=Sílvio Roberto dos Santos |volume=10|language=pt-br}} | |||

| *{{Cite journal|url=https://www.editorarealize.com.br/editora/anais/enlije/2014/Modalidade_1datahora_09_06_2014_09_39_27_idinscrito_964_540390d58acb5b23fa8c79aedd241335.pdf|title=Um olhar sobre a pedagogia de Luiz Gama: representações do negro no universo pré-adolescente|last=dos Santos|first=Jair Cardoso|year=2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210830123854/https://www.editorarealize.com.br/editora/anais/enlije/2014/Modalidade_1datahora_09_06_2014_09_39_27_idinscrito_964_540390d58acb5b23fa8c79aedd241335.pdf|archive-date=2021-08-30|url-status=live|language=pt-br|pages=12}} | |||

| === Books === | |||

| *{{Cite book|title=Flores, votos e balas: O movimento abolicionista brasileiro (1868–88)|last=Alonso|first=Angela|publisher=Companhia das Letras|year=2015|place=Rio de Janeiro|language=pt-br}} | |||

| *{{Cite book|title=Orfeu de Carapinha: A trajetória de Luiz Gama na imperial cidade de São Paulo|last=Azevedo|first=Elciene|publisher=Editora da Unicamp|year=1999|place=São Paulo|language=pt-br}} | |||

| *{{Cite book|url=https://www.expressaopopular.com.br/loja/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/luiz-gama.pdf|title=Luiz Gama – o libertador de escravos e sua mãe libertária, Luíza Mahin|last=Benedito|first=Mouzar|publisher=Expressão Popular|edition=2|year=2011|place=São Paulo|isbn=978-85-7743-004-8|pages=80|language=pt-br|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210827181104/https://www.expressaopopular.com.br/loja/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/luiz-gama.pdf|archive-date=2021-08-27|url-status=dead}} | |||

| *{{Cite book|title=Advogado Dos Escravos|last=Câmara|first=Nelson|publisher=Lettera doc|year=2010|place=São Paulo|language=pt-br}} | |||

| *{{Cite book|title=Primeiras trovas burlescas e outros poemas|last1=Gama|first1=Luís|last2=Ferreira|first2=Lígia|publisher=Martins Fontes|year=2000|place=São Paulo|language=pt-br}} | |||

| *{{Cite book|title=Encyclopedia of Latin American history and culture|date=2008|publisher=Gale|last1=Kinsbruner|first1=Jay.|last2=Langer|first2=Erick Detlef.|isbn=9780684312705|edition= 2|location=Detroit|oclc=191318189}} | |||

| *{{Cite book|url=https://bdor.sibi.ufrj.br/bitstream/doc/201/1/119%20PDF%20-%20OCR%20-%20RED.pdf|title=O Precursor do Abolicionismo no Brasil: Luís Gama|last=Menucci|first=Sud|publisher=Companhia Editora Nacional|year=1938|place=São Paulo|language=pt-br}} | |||

| *{{Cite book|title=Luiz Gama|last=Santos|first=Luiz Carlos|publisher=Selo Negro Edições|year=2014|language=pt-br}} | |||

| *{{Cite book|title=Luís da Gama e suas Poesias Satíricas|last=Silva|first=J. Romão|publisher=Casa do Estudante do Brasil|year=1954|place=Rio de Janeiro|language=pt-br}} | |||

| ==Additional reading== | |||

| *{{Cite book|title=Encyclopedia of African-American culture and history : the Black experience in the Americas|date=2006|publisher=Macmillan Reference USA|others=Palmer, Colin A., 1944–|isbn=0028658213|edition= 2nd|location=Detroit|oclc=60323165}} - Used in the article body on | |||

| *{{Cite book|title=Encyclopedia of emancipation and abolition in the Transatlantic world|others=Rodriguez, Junius P.,, Ackerson, Wayne|isbn=978-1317471790|location=London |oclc=908062295|date = 2015-03-26}} - Used in the article body on | |||

| *{{Cite journal|last1=Santos|first1=Eduardo Antonio Estevam|date=December 2015|title=Luiz Gama and the racial satire as the transgression poetry: diasporic poetry as counter-narrative to the idea of race|url=http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S2236-46332015000300707&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en|journal=Almanack|issue=11|pages=707–727|doi=10.1590/2236-463320151108|issn=2236-4633|doi-access=free}} - Used in the article body on | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| Line 83: | Line 331: | ||

| * (in English) | * (in English) | ||

| * {{in lang|pt}} | * {{in lang|pt}} | ||

| * (in Portuguese) | * {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200611115028/http://institutoluizgama.org.br/portal/ |date=2020-06-11 }} (in Portuguese) | ||

| * {{Cite news|url=https://www.economist.com/books-and-arts/2021/10/27/brazil-reckons-with-the-life-and-legacy-of-an-abolitionist|title=Brazil reckons with the life and legacy of an abolitionist|date=2021-10-27|newspaper=The Economist}} | |||

| * {{Cite web|url=https://projetoluizgama.hedra.com.br/OBRAS-en|title=OBRAS – Projeto Luiz Gama|language=en}} | |||

| {{Portalbar|Biography|Literature|Journalism}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | {{Authority control}} | ||

| Line 89: | Line 340: | ||

| {{Empire of Brazil}} | {{Empire of Brazil}} | ||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Gama, |

{{DEFAULTSORT:Gama, Luís}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 17:11, 2 September 2024

19th century Brazilian lawyer and abolitionist| Luís Gama | |

|---|---|

Gama, c. 1880 Gama, c. 1880 | |

| Born | (1830-06-21)21 June 1830 Salvador, Bahia, Brazil |

| Died | 24 August 1882(1882-08-24) (aged 52) São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil |

| Monuments | Luiz Gama [pt] |

| Nationality | Brazilian |

| Other names | Afro, Getúlio, Barrabaz, Spartacus and John Brown |

| Education | Autodidact |

| Occupation(s) | Lawyer, writer, abolitionist |

| Known for | He was able to have had freed more than 500 people from the condition of slavery. |

| Notable work | Primeiras Trovas Burlescas do Getulino |

| Political party | Liberal PRP (1873–1873) |

| Spouse | Claudina Fortunata Sampaio |

| Children | Benedito Graco Pinto da Gama |

| Parents |

|

| Awards | XXXII Prêmio Franz de Castro Holzwarth de Direitos Humanos [pt] |

Luís Gonzaga Pinto da Gama (21 June 1830 – 24 August 1882) was a Brazilian lawyer, abolitionist, orator, journalist and writer, and the Patron of the abolition of slavery in Brazil.

Born to a free black mother and a white father, he was nevertheless made a slave at the age of 10, and remained illiterate until the age of 17. He judicially won his own freedom and began to work as a lawyer on behalf of the captives, and by the age of 29 he was already an established author and considered "the greatest abolitionist in Brazil".

Although considered one of the exponents of romanticism [pt], works such as Manuel Bandeira's "Apresentação da Poesia Brasileira" do not even mention his name. He had such a unique life that it is difficult to find, among his biographers, any who do not become passionate when portraying him – being himself also charged with passion, emotional and yet captivating.

He was a black intellectual in 19th century slave-owning Brazil, the only self-taught and the only one to have gone through the experience of captivity. He spent his life fighting for the abolition of slavery and for the end of the monarchy in Brazil, but died six years before these causes were accomplished. In 2018 his name was inscribed in the Steel Book of national heroes deposited in the Tancredo Neves Pantheon of the Fatherland and Freedom.

Panorama from the time

São Paulo, where Gama lived for forty-two years, was in the middle of the 19th century a still small provincial capital that, with the demand for coffee production from the 1870s on, saw the price of slaves reach a level that made their urban possession almost prohibitive. Until this period, however, it was quite common the property of "rent slaves", on whose work their owners drew their source of sustenance, alongside the so-called "domestic slaves".

It had a population ten times smaller than that of the Court (Rio de Janeiro), and a very strong presence of legal culture because, since 1828, one of the only two law schools in the country had been established there, the Largo de São Francisco Law School, which received students from all over the country, coming from all social strata – besides the children of the rural oligarchy, members of the intellectual elite that was being formed at the time (Gama defined it, then, as "Noah's Ark in a small way").

Childhood and slavery

Luís Gama was born on June 21, 1830, at Bângala street Nº2, in the centre from the city of Salvador, Bahia. Even with little information about his childhood, it is known that he was the son of Luísa Mahin, a freed African ex-slave, and the son of a Portuguese fidalgo who lived in Bahia. At the age of seven, his mother traveled to Rio de Janeiro to participate in the Sabinada revolt, never to meet him again. In 1840, his father ended up in debt with gambling, so he resorted to selling Luís Gama as a slave to pay his debts. There is no evidence that his father sought him out after that. As an adult, Gama understood that when he was sold he was a victim of the crime of "Enslaving a free person, who is in possession of his freedom.", provided in Article 179 from Criminal Code of the Empire of Brazil, sanctioned shortly after his birth. Furthermore, due to the fact that the revolts that took place in Bahia led to the prohibition of the sale of slaves from this province to other regions of Brazil, the sale and transport of Luís Gama to São Paulo was constituted as contraband.

In an autobiographical letter he sent in 1880 to Lúcio de Mendonça [pt], he describes his birth and early childhood thus:

I was born in the city of S. Salvador, capital of the Bahia province, in a two-story house at Bângala Street, forming an internal angle, in the "Quebrada", on the right side from the Palma churchyard, in the Sant'Ana parish, on June 21, 1830, at 7 in the morning, and I was baptized, eight years later, in the main church of Sacramento, in the city of Itaparica.