| Revision as of 02:33, 22 February 2007 view sourcePernambuco (talk | contribs)1,533 edits Life and Letters of Dr Samuel Hahnemann, Philadelphia: Boericke & Tafel, 1895← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 01:03, 20 November 2024 view source Engineerchange (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users28,666 edits →See also: add Samuel Hahnemann Monument to see also | ||

| (745 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|German physician who created homeopathy (1755–1843)}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{pp-protected|small=yes}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=April 2018}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Infobox person | |||

| {{see also|Homeopathy|Classical homeopathy}} | |||

| |name = Samuel Hahnemann | |||

| '''Christian Friedrich Samuel Hahnemann''' (] ] in ], ] - ] ] in ], ]) was a German physician who founded ]. Hahnemann is also credited with introducing the practice of ] during his employment with the Duke of ]. | |||

| |image = Samuel_Hahnemann_Daguerreotype_1840s.png | |||

| |image_size = 250px | |||

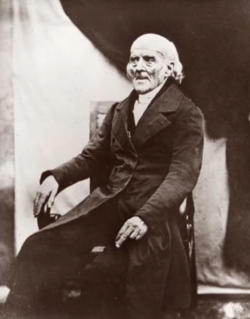

| |caption = Hahnemann in 1841 | |||

| |birth_date = {{birth date|1755|4|10|df=yes}} | |||

| |birth_place = ], ] | |||

| |birth_name = Christian Friedrich Samuel Hahnemann | |||

| |death_date = {{death date and age|1843|7|2|1755|4|10|df=yes}} | |||

| |death_place = ], France | |||

| |citizenship = | |||

| |nationality = German | |||

| |alma_mater = | |||

| |known_for = ] | |||

| | awards = | |||

| |footnotes = | |||

| |signature = Signatur Samuel Hahnemann.PNG | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Christian Friedrich Samuel Hahnemann''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|h|ɑː|n|ə|m|ə|n}} {{respell|HAH|nə|mən}}, {{IPA|de|ˈzaːmueːl ˈhaːnəman|lang}}; 10 April 1755<ref>Though some sources do state that he was born in the early hours of 11 April 1755, {{cite book|first=Richard |last=Haehl |title=Samuel Hahnemann his Life and Works |volume=1 |year=1922 |page=9 |quote=Hahnemann, was born on 10 April at approximately twelve o'clock midnight.}}</ref> – 2 July 1843) was a German ], best known for creating the ] system of ] called ].<ref name=Ladyman>{{cite book |author=Ladyman J |veditors=Pigliucci M, Boudry M |year=2013 |pages=48–49 |publisher=University of Chicago Press |chapter=Chapter 3: Towards a Demarcation of Science from Pseudoscience |title=Philosophy of Pseudoscience: Reconsidering the Demarcation Problem |quote=Yet homeopathy is a paradigmatic example of pseudoscience. It is neither simply bad science nor science fraud, but rather profoundly departs from scientific method and theories while being described as scientific by some of its adherents (often sincerely). |isbn=978-0-226-05196-3}}</ref> | |||

| == Early life == | |||

| An impressive in ] commemorates Hahnemann's life and works. | |||

| Christian Friedrich Samuel Hahnemann was born in ], ], near ]. His father Christian Gottfried Hahnemann<ref>. Homoeoscan.com. 10 April 2014</ref> was a painter and designer of porcelain, for which the town of Meissen is famous.<ref> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| | author = Coulter, Harris Livermore | |||

| | title = Divided Legacy, a History of the Schism in Medical Thought | |||

| | volume = II | |||

| | location = Washington | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | year = 1977 | |||

| | page = 306 | |||

| | isbn = 0-916386-02-3 | |||

| | oclc = 67493911 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| As a young man, Hahnemann became proficient in a number of languages, including English, French, Italian, Greek and Latin. He eventually made a living as a translator and teacher of languages, gaining further proficiency in "], ], ] and ]".<ref name="skylarkbio"> | |||

| Hahnemann's notable works include: | |||

| {{cite web | |||

| *''Versuch über ein neues Prinzip zur Auffindung der Heilkräfte der Arzneisubstanzen, nebst einigen Blicken auf die bisherigen'', (''Hufelands Journal der practischen Arzneykunde'', ]) | |||

| | url = http://www.skylarkbooks.co.uk/Hahnemann_Biography.htm | |||

| *'']'' (]) explains the theory of homeopathic medicine. Hahnemann published the 5th edition in ]; an unfinished 6th edition was discovered after Hahnemann's death but not published until ]. | |||

| | title = Hahnemann Biography | |||

| *'']'' is a compilation of ] reports, published in six volumes during the ] (vol. VI in ].) Revised editions of volumes I and II were published in ] and ], respectively. | |||

| | access-date = 13 January 2009 | |||

| *''Chronic Diseases'' (1828) is an elucidation of the root and cure of ] together with a compilation of ] reports, published in five volumes during the ]. | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| Hahnemann studied medicine for two years at ]. Citing Leipzig's lack of clinical facilities, he moved to ], where he studied for ten months.<ref> | |||

| ==Life== | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| Born Christian Friedrich Samuel Hahnemann in ], ] on ], ], Hahnemann showed early proficiency at languages; ''"by twenty he had mastered ], ], ], ] and ],"'' <ref>http://www.skylarkbooks.co.uk/Hahnemann_Biography.htm</ref> and was making a living as a translator and teacher of languages. He later gained proficiency in ''"], ], Chaldaic and ]."'' <ref>http://www.skylarkbooks.co.uk/Hahnemann_Biography.htm</ref> | |||

| |author = Martin Kaufman | |||

| |title = Homeopathy in America, the Rise and Fall of a Medical Heresy | |||

| |location = Baltimore | |||

| |publisher = Johns Hopkins University Press | |||

| |year = 1972 | |||

| |page = 24 | |||

| |isbn = 0-8018-1238-0 | |||

| |oclc = 264319 | |||

| }}</ref> His medical professors in Leipzig and Vienna included the physician ],<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6CGjDgAAQBAJ&q=%22Joseph%20von%20Quarin%22 |title=The Birth of Homeopathy out of the Spirit of Romanticism|first=Alice A.|last=Kuzniar|year=2017|publisher=University of Toronto Press|isbn= 978-1487521264}}</ref> later credited for turning ] into a model European medical institution.<ref> (biography)</ref> | |||

| After one term of further study, Hahnemann graduated with a medical degree with honors from the ] on 10 August 1779. His poverty may have forced him to choose Erlangen, as the school's fees were lower than in Vienna.<ref>Haehl, vol. 1, p. 24.</ref> Hahnemann's thesis was titled ''Conspectus adfectuum spasmodicorum aetiologicus et therapeuticus'' .<ref>Cook, p. 36.</ref><ref> | |||

| Hahnemann studied medicine at ] and ]. He received his doctor of medicine degree at the ] on 10 August ], qualifying with honors with a thesis on the treatment of cramps. He began practicing as a doctor in ]. ''"Shortly thereafter he married Johanna Henriette Kuchler"''<ref>http://www.skylarkbooks.co.uk/Hahnemann_Biography.htm</ref>; they had eleven children. | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| | author = Richard Haehl | |||

| | title = Samuel Hahnemann His Life and Work | |||

| | year = 1922 | |||

| | volume = 2 | |||

| | page = 11 | |||

| | location = London | |||

| | publisher = Homoeopathic Publishing | |||

| | oclc = 14558215 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| == Medical practice == | |||

| Through his practice, Hahnemann quickly discovered that the medicine of his day did as much harm as good: | |||

| In 1781, Hahnemann took a village doctor's position in the copper-mining area of ], ].<ref>Haehl, vol. 1, p. 26.</ref> He soon married Johanna Henriette Kuchler and would eventually have eleven children.<ref name="skylarkbio"/> After abandoning medical practice, and while working as a translator of scientific and medical textbooks, he translated fifteen books from English, six from French and one each from Latin and Italian from 1777 to 1806.<ref>Bradford, pp. 515–16.</ref> Hahnemann travelled around Saxony for many years, staying in many different towns and villages for varying lengths of time, never living far from the ] and settling at different times in ], ], ] and ]<ref>Cook, pp. 83–4,</ref> before finally moving to Paris in June 1835.<ref>Cook, p. 168.</ref> | |||

| :''"My sense of duty would not easily allow me to treat the unknown pathological state of my suffering brethren with these unknown medicines. The thought of becoming in this way a murderer or malefactor towards the life of my fellow human beings was most terrible to me, so terrible and disturbing that I wholly gave up my practice in the first years of my married life and occupied myself solely with ] and writing."'' <ref>http://www.skylarkbooks.co.uk/Hahnemann_Biography.htm</ref> | |||

| ===Creation of homeopathy=== | |||

| After giving up his practice he made his living chiefly as a writer and translator. While translating ]'s ''A Treatise on the Materia Medica'', Hahnemann encountered the claim that ], the bark of a Peruvian tree, was effective in treating ] because of its astringency. Hahnemann realised that other astringent substances are not effective against ] and began to research ]'s effect on the human organism very directly: by self-application. He discovered that the drug evoked malaria-like symptoms in himself, and concluded that it would do so in any healthy individual. This led him to postulate a healing principle: ''"that which can produce a set of symptoms in a healthy individual, can treat a sick individual who is manifesting a similar set of symptoms."'' <ref>http://www.skylarkbooks.co.uk/Hahnemann_Biography.htm</ref> This principle, ''like cures like'', became the first of a new medicinal approach to which he gave the name ]. | |||

| {{Main article|Homeopathy}} | |||

| Hahnemann was dissatisfied with the state of medicine in his time, and particularly objected to practices such as ]. He claimed that the medicine he had been taught to practice sometimes did the patient more harm than good: | |||

| <blockquote>My sense of duty would not easily allow me to treat the unknown pathological state of my suffering brethren with these unknown medicines. The thought of becoming in this way a murderer or malefactor towards the life of my fellow human beings was most terrible to me, so terrible and disturbing that I wholly gave up my practice in the first years of my married life and occupied myself solely with ] and writing.<ref name="skylarkbio"/></blockquote> | |||

| After giving up his practice around 1784, Hahnemann made his living chiefly as a writer and translator, while resolving also to investigate the causes of medicine's alleged errors. While translating ]'s ''A Treatise on the Materia Medica'', Hahnemann encountered the claim that ], the bark of a Peruvian tree, was effective in treating ] because of its astringency. Hahnemann believed that other astringent substances are not effective against malaria and began to research cinchona's effect on the human body by self-application. Noting that the drug induced malaria-like symptoms in himself,<ref>Haehl, vol. 1, p.38; Dudgeon, p.48</ref> he concluded that it would do so in any healthy individual. This led him to postulate a healing principle: "that which can produce a set of symptoms in a healthy individual, can treat a sick individual who is manifesting a similar set of symptoms."<ref name="skylarkbio"/> This principle, ''like cures like'', became the basis for an approach to medicine which he gave the name ]. He first used the term homeopathy in his essay ''Indications of the Homeopathic Employment of Medicines in Ordinary Practice'', published in ]'s ''Journal'' in 1807.<ref>Gumpert, Martin (1945) ''Hahnemann: The Adventurous Career of a Medical Rebel'', New York: Fischer, p. 130.</ref> | |||

| Hahnemann began systematically testing substances for the effect they produced on a healthy individual and trying to deduce from this the ills they would heal. He quickly discovered that ingesting substances to produce noticeable changes in the organism resulted in toxic effects. His next task was to solve this problem, which he did through exploring dilutions of the compounds he was testing. He claimed that these dilutions, when done according to his technique of ] (systematic mixing through vigorous shaking) and ], were still effective in producing symptoms. However, these effects have never been duplicated in ], and his approach has been universally abandoned by modern medicine. | |||

| === Development of homeopathy === | |||

| Hahnemann began practicing medicine again using his new technique, which soon attracted other doctors. He first published an article about the homeopathic approach to medicine in a ] medical journal in ]; in ], he wrote his ''Organon of the Medical Art'', the first systematic treatise on the subject. | |||

| Following up the work of the Viennese physician ], Hahnemann tested substances for the effects they produced on a healthy individual, presupposing (as von Störck had claimed) that they may heal the same ills that they caused. His researches led him to agree with von Störck that the toxic effects of ingested substances are often broadly parallel to certain disease states,<ref>Dudgeon, pp.xxi–xxii; Cook, p.95</ref> and his exploration of historical cases of poisoning in the medical literature further implied a more generalised medicinal "law of similars".<ref>Dudgeon, p.49 & p.176; Haehl, vol. 1, p.40</ref> He later devised methods of diluting the drugs he was testing in order to mitigate their toxic effects. He claimed that these dilutions, when prepared according to his technique of "potentization" using dilution and succussion (vigorous shaking), were still effective in alleviating the same symptoms in the sick. His more systematic experiments with dose reduction really commenced around 1800–01 when, on the basis of his "law of similars," he had begun using '']'' for the treatment of coughs and ] for scarlet fever.<ref>Cook, pp.96–7; Dudgeon, pp.338–340 & pp.394–408</ref> | |||

| He first published an article about the homeopathic approach in a ] medical journal in 1796. Following a series of further essays, he published in 1810 "Organon of the Rational Art of Healing", followed over the years by four further editions entitled '']'', the first systematic treatise and containing all his detailed instructions on the subject. A 6th ''Organon'' edition, unpublished during his lifetime, and dating from February 1842, was only published many years after his death. It consisted of a 5th ''Organon'' containing extensive handwritten annotations.<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101021000237/http://www.minimum.com/reviews/organon-sixth.htm |date=21 October 2010 }}. Minimum.com. Retrieved on 16 May 2012.</ref> The ''Organon'' is widely regarded as a remodelled form of an essay he published in 1806 called "The Medicine of Experience", which had been published in Hufeland's Journal. Of the ''Organon'', ] states it "was an amplification and extension of his "Medicine of Experience", worked up with greater care, and put into a more methodical and ] form, after the model of the Hippocratic writings."<ref>] (1853) ''Lectures on the Theory and Practice of Homeopathy'', London: Henry Turner, p. xxxi.</ref> | |||

| Hahnemann continued practicing medicine, researching new medicines, writing and lecturing to the end of a long life. He died in ] in ], 88 years of age, and is entombed in a mausoleum at ]'s ] cemetery. | |||

| === Coffee theory of disease === | |||

| == Other Achievements == | |||

| ] (1837)]] | |||

| Around the start of the nineteenth century Hahnemann developed a theory, propounded in his 1803 essay ''On the Effects of Coffee from Original Observations'', that many diseases are caused by ].<ref>Hahnemann S (1803): '''', in Hahnemann S., Dudgeon R. E. (ed) (1852): ''The Lesser Writings of Samuel Hahnemann''. New York: ], p. 391.</ref> Hahnemann later abandoned the coffee theory in favour of the theory that disease is caused by '']'', but it has been noted that the list of conditions Hahnemann attributed to coffee was similar to his list of conditions caused by ''Psora''.<ref>Morrell, P. (1996): , www.homeoint.org</ref> | |||

| == Later life == | |||

| Although most famous today as the founder of ], this was not the sole focus of his research. Some of his other discoveries are still in use today, such as the potent ] (for the presence of arsenic in solids). It involved combining a sample fluid with hydrogen sulfide in the presence of hydrochloric acid. A yellow precipitate, arsenic trisulfide, would be formed if arsenic were present. | |||

| ] at ], Washington, D.C.]] | |||

| In early 1811<ref>Bradford, p. 76.</ref> Hahnemann moved his family back to ] with the intention of teaching his new medical system at the ]. As required by the university statutes, to become a faculty member he was required to submit and defend a thesis on a medical topic of his choice. On 26 June 1812, Hahnemann presented a ] thesis, entitled ''"A Medical Historical Dissertation on the Helleborism of the Ancients."''<ref>Bradford, p. 93.</ref> His thesis very thoroughly examined the historical literature and sought to differentiate between the ancient use of '']'', or black hellebore, and the medicinal uses of the "white hellebore", botanically '']'', both of which are poisonous plants.<ref>Haehl, Vol. 2, p. 96.</ref> | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| * Online etext of Hahnemann's ''Organon der Heilkunst'': | |||

| ** () | |||

| ** | |||

| * | |||

| Hahnemann continued practicing and researching homeopathy, as well as writing and lecturing for the rest of his life. He died in 1843 in Paris, at 88 years of age, and is entombed in a mausoleum at Paris's ].{{citation needed|date=April 2018}} | |||

| == Descendants == | |||

| * | |||

| Hahnemann's daughter, Amelie (1789–1881), had a son: Leopold Suss-Hahnemann. Leopold emigrated to England, and he practised homeopathy in London. He retired to the ] and died there at the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Dr Leopold Suss-Hahnemann's youngest daughter, Amalia, had two children, Winifred (born in 1898) and Herbert. William Herbert Tankard-Hahnemann (1922–2009) was Winifred's son. He served as a Major in the British Army during World War II, and then had a career in the city of London. He was at one point appointed as a Freeman of the City of London. Mr William Herbert Tankard-Hahnemann, the great-great-great-grandson of Samuel Hahnemann died on 12 January 2009 (his 87th birthday) after 22 years of active patronage of the British Institute of Homeopathy.{{citation needed|date=August 2019}} The William Tankard-Hahnemann line continues with his son, Charles. | |||

| * A historical overview | |||

| * | |||

| == |

== Writings == | ||

| Hahnemann wrote a number of books, essays, and letters on the homeopathic method, chemistry, and general medicine: | |||

| <references/> | |||

| * ''Heilkunde der Erfahrung.'' Norderstedt 2010, {{ISBN|3-8423-1326-8}} | |||

| * {{cite book | |||

| | url = http://www.mickler.de/journal/versuch-prinzip-1.htm | |||

| | title = Versuch über ein neues Prinzip zur Auffindung der Heilkräfte der Arzneisubstanzen, nebst einigen Blicken auf die bisherigen | |||

| | language = de | |||

| | year = 1796 | |||

| }} reprinted in {{cite book | title = Versuch über ein neues Prinzip zur Auffindung der Heilkräfte der Arzneisubstanzen, nebst einigen Blicken auf die bisherigen | year = 1988 | publisher = Haug | isbn = 3-7760-1060-6 }} | |||

| *'']'', a collection of 27 drug "provings" published in ] in 1805.<ref> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| | title = Fragmenta de viribus medicamentorum positivis, sive in sano corpore humano observatis | |||

| | language = la | |||

| | oclc = 14852975 | |||

| | url = https://archive.org/details/fragmentadeviri00hahngoog | |||

| | year = 1824 | |||

| | publisher = Typis observatoris medici | |||

| }}</ref><ref> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| |url = http://www.hahnemann.de/frontend1/media/pdf/fragmenta_leseprobe.pdf | |||

| |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20080413203202/http://www.hahnemann.de/frontend1/media/pdf/fragmenta_leseprobe.pdf | |||

| |url-status = dead | |||

| |archive-date = 13 April 2008 | |||

| |title = Übersetzung der 'Fragmenta de viribus medicamentorum' von Marion Wettemann | |||

| |language = de | |||

| }}{{Dubious|date=January 2009}}</ref>{{Dubious|date=January 2009}}<ref>. Homeoint.org. Retrieved on 16 May 2012.</ref> | |||

| *'']'' (1810), a detailed delineation of what he saw as the rationale underpinning homeopathic medicine, and guidelines for practice. Hahnemann published the 5th edition in 1833; a revised draft of this (1842) was discovered after Hahnemann's death and finally published as the 6th edition in 1921.<ref>Online etext of Hahnemann's ''Organon der Heilkunst''.</ref><ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070429001118/http://www.vithoulkas.com/homeopathy/organon/index.html |date=29 April 2007 }} English version, full text online; (); {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140713184926/http://www.homeopathyhome.com/reference/organon/organon.html |date=13 July 2014 }}. Homeopathyhome.com. Retrieved on 16 May 2012.</ref> | |||

| *'']'', a compilation of "]" reports, published in six volumes between vol. I in 1811 and vol. VI in 1821; second edition of vol. I to Vol. VI from 1822 to 1827 and third revised editions of volumes I and II were published in 1830 and 1833, respectively.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.homeoint.org/books4/bradford/bibliography.htm |title=The Life and Letters of Dr Samuel Hahnemann |last=Bradford |first=TL |date= |website=HOMÉOPATHE INTERNATIONAL |access-date=14 April 2021}}</ref> | |||

| *''Chronic Diseases'' (1828), an explanation of the root and cure of ] according to the theory of ]s, together with a compilation of "]" reports, published in five volumes during the 1830s. | |||

| * ''The Friend of Health'', in which Hahnemann "recommended the use of fresh air, bed rest, proper diet, sunshine, public hygiene and numerous other beneficial measures at a time when many other physicians considered them of no value."<ref>{{cite book | last1 = Rothstein | first1 = William G. | title = American physicians in the nineteenth century: from sects to science | location = Baltimore | publisher = Johns Hopkins University Press | year = 1992|isbn=978-0-8018-4427-0 | page = 158 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book | title = The Friend of Health | author = Hahnemann, Samuel | year = 1792}}</ref> | |||

| * ''Appeal to Thinking Philanthropist Respecting the Mode of Propagation of the Asiatic Choler'', in which Hahnemann describes cholera physicians and nurses as the "certain and frequent propagators" of ] and that whilst deriding nurses' "fumigations with chlorine", promoted the use of "drops of camphorated spirit" as a cure for the disease.<ref> | |||

| {{cite book | url = https://archive.org/details/lesserwritingss00hahngoog | |||

| | chapter = Appeal to thinking philanthropist respecting the mode of propagation of the Asiatic choler | author = Hahnemann, Samuel | year = 1831 | title = The lesser writings of Samuel Hahnemann | pages = –763 | oclc = 3440881| publisher = William Radde }}</ref> | |||

| * Hahnemann also campaigned for the humane treatment of the ] in 1792.<ref>{{cite book | url = https://archive.org/details/lesserwritingss00hahngoog | chapter = Description of Klockenbring During his Insanity | title = The lesser writings of Samuel Hahnemann | author = Hahnemann, Samuel | year=1796 | pages= | oclc = 3440881| publisher = William Radde}}</ref> | |||

| * ] wrote that "In 1787, Hahnemann discovered the best test for arsenic and other poisons in wine, having pointed out the unreliable nature of the '],' which had been in use up to that date."<ref>{{cite book | author = John Henry Clarke | title = Homoeopathy: all about it; or, The principle of cure | url = https://archive.org/details/b20392576 | year = 1894 | place = London | publisher = Homoeopathic Publishing | oclc = 29160937 | author-link = John Henry Clarke }}</ref><ref>Haehl, Vol. 1, p. 34.</ref> | |||

| * ''Samuel Hahnemanns Apothekerlexikon''. Vol.2. Crusius, Leipzig 1798–1799 by the ] | |||

| * ''Reine Arzneimittellehre''. Arnold, Dresden (several editions) 1822–1827 by the ] | |||

| * ''Systematische Darstellung der reinen Arzneiwirkungen aller bisher geprüften Mittel''. Vieweg, Braunschweig 1831 – by the ] | |||

| == See also == | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| {{reflist|colwidth=30em}} | |||

| ==References== | |||

| *{{cite book | |||

| | author = Bradford, Thomas Lindsley | |||

| | title = The Life and Letters of Samuel Hahnemann | |||

| | orig-year = 1895 | |||

| | date = 1999 | |||

| | location = Philadelphia | |||

| | publisher = Boericke & Tafel | |||

| | oclc = 1489955 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book | |||

| | author = Cook, Trevor | |||

| | title = Samuel Hahnemann Founder of Homeopathy | |||

| | location = Wellingborough, Northamptonshire | |||

| | publisher = Thorsons | |||

| | year = 1981 | |||

| | isbn = 0-7225-0689-9 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book | url = https://archive.org/details/samuelhahnemannh01haehuoft | author = Haehl, Richard; Wheeler, Marie L. (tr.) and Grundy, W.H.R. (tr.) | editor = John Henry Clarke, Francis James Wheeler | title = Samuel Hahnemann his Life and Work | volume = 1 | year = 1922 | publisher = Homoeopathic Publishing | place = London | oclc = 222833661 }}, reprinted as {{ISBN|81-7021-693-1}} | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| {{refbegin}} | |||

| *{{Cite journal | |||

| | pmid = 18354994 | |||

| | last = Brockmeyer | |||

| | first = Bettina | |||

| | year = 2007 | |||

| | title = Representations of illness in letters addressed to Samuel Hahnemann: gender and historical perspectives | |||

| | language = de | |||

| | volume = 29 | |||

| |journal= Medizin, Gesellschaft, und Geschichte: Jahrbuch des Instituts für Geschichte der Medizin der Robert Bosch Stiftung | |||

| | pages = 211–221, 259 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{Cite journal | |||

| | pmid = 17153748 | |||

| | last = Kayne | |||

| | first = Steven | |||

| | year = 2006 | |||

| | title = Samuel Hahnemann (1755–1843): the founder of modern homeopathy. | |||

| | volume = 36 | |||

| | issue = 2 Suppl | |||

| | journal= Pharmaceutical Historian | |||

| | pages = S23–6 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{Cite journal | |||

| | pmid = 17153289 | |||

| | last = Brockmeyer | |||

| | first = Bettina | |||

| | year = 2005 | |||

| | title = Writing about oneself and others: men and women in letters to doctor Samuel Hahnemann 1831–1835 | |||

| | language = de | |||

| | volume = 24 | |||

| | journal = Würzburger medizinhistorische Mitteilungen / Im Auftrage der Würzburger medizinhistorischen Gesellschaft und in Verbindung mit dem Institut für Geschichte der Medizin der Universität Würzburg | |||

| | pages = 18–28 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{Cite journal | |||

| | pmid = 15871338 | |||

| | year = 2005 | |||

| | title = Biographic synopsis on Samuel Hahnemann | |||

| | language = es | |||

| | volume = 28 | |||

| | issue = 3 | |||

| | journal= Revista de enfermería (Barcelona, Spain) | |||

| | pages = 10–16 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{Cite journal | |||

| | pmid = 15822443 | |||

| | last = Eschenbruch | |||

| | first = Nicholas | |||

| | year = 2005 | |||

| | title = Rationalist, magician, scharlatan? Samuel Hahnemann and homeopathy from the viewpoint of homeopathy | |||

| | language = de | |||

| | volume = 94 | |||

| | issue = 11 | |||

| |journal= Schweiz. Rundsch. Med. Prax. | |||

| | pages = 443–446 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{Cite journal | |||

| | pmid = 11624613 | |||

| | last = Jutte | |||

| | first = R. | |||

| | year = 1999 | |||

| | title = "Thus it passes from the patient's purse into that of the doctor without causing displeasure" – Samuel Hahnemann and medical fees | |||

| | language = de | |||

| | volume = 18 | |||

| | journal= Medizin, Gesellschaft, und Geschichte: Jahrbuch des Instituts für Geschichte der Medizin der Robert Bosch Stiftung | |||

| | pages = 149–167 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{Cite journal | |||

| | pmid = 8121514 | |||

| | last = de Goeij | |||

| | first = C. M. | |||

| | year = 1994 | |||

| | title = Samuel Hahnemann: an indignant systems builder | |||

| | language = nl | |||

| | volume = 138 | |||

| | issue = 6 | |||

| |journal = Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde | |||

| | pages = 310–314 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{Cite journal | |||

| | pmid = 11620590 | |||

| | last = Rizza | |||

| | first = E. | |||

| | year = 1994 | |||

| | title = Samuel Hahnemann: a mystical empiricist. A study of the origin and development of the homeopathic medical system | |||

| | language = it | |||

| | volume = 6 | |||

| | issue = 3 | |||

| |journal = Medicina Nei Secoli | |||

| | pages = 515–524 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite journal | |||

| | pmid = 1405462 | |||

| | last = Meissner | |||

| | first = M. | |||

| | year = 1992 | |||

| | title = Samuel Hahnemann—the originator of homeopathic medicine | |||

| | volume = 30 | |||

| | issue = 7–8 | |||

| |journal = Krankenpflege Journal | |||

| | pages = 364–366 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite journal | |||

| | pmid = 2970128 | |||

| | last = Schmidt | |||

| | first = J. M. | |||

| | year = 1988 | |||

| | title = The publications of Samuel Hahnemann | |||

| | volume = 72 | |||

| | issue = 1 | |||

| |journal = Sudhoffs Archiv | |||

| | pages = 14–36 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite journal | |||

| | pmid = 6750668 | |||

| | last = Lozowski | |||

| | first = J. | |||

| | year = 1982 | |||

| | title = Homeopathy (Samuel Hahnemann) | |||

| | language = pl | |||

| | issue = 4–5 | |||

| |journal = Pielȩgniarka I Połozna | |||

| | pages = 16–17 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite journal | |||

| | pmid = 11610925 | |||

| | last = Habacher | |||

| | first = M. | |||

| | year = 1980 | |||

| | title = Homöopathische Fernbehandlung durch Samuel Hahnemann | |||

| | language = de | |||

| | volume = 15 | |||

| | issue = 4 | |||

| |journal = Medizinhistorisches Journal | |||

| | pages = 385–391 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite journal | |||

| | pmid = 4581537 | |||

| | last1 = Antall | |||

| | first1 = J. | |||

| | last2 = Kapronczay | |||

| | first2 = K. | |||

| | year = 1973 | |||

| | title = Samuel Hahnemann | |||

| | volume = 114 | |||

| | issue = 32 | |||

| |journal = Orvosi Hetilap | |||

| | pages = 1945–1947 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite journal | |||

| | pmid = 14143315 | |||

| | last = Hodges | |||

| | first = P. C. | |||

| | year = 1964 | |||

| | title = Homeopathy and Christian Friedrich Samuel Hahnemann | |||

| | volume = 35 | |||

| | journal = Postgraduate Medicine | |||

| | pages = 666–668 | |||

| | doi = 10.1080/00325481.1964.11695164 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite journal | |||

| | pmid = 13562700 | |||

| | last = Dietrich | |||

| | first = H. J. | |||

| | year = 1958 | |||

| | title = Hahnemann's capacity for greatness; Samuel Hahnemann; and Hahnemann Medical College | |||

| | volume = 93 | |||

| | issue = 2 | |||

| |journal=The Hahnemannian | |||

| | pages = 35–39 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite journal | |||

| | pmid = 14379841 | |||

| | last = Koch | |||

| | first = E. | |||

| | year = 1955 | |||

| | title = On the 200th anniversary of Dr. Samuel Hahnemann; several ideas concerning homeopathy | |||

| | language = de | |||

| | volume = 10 | |||

| | issue = 16 | |||

| | periodical=Das Deutsche Gesundheitswesen | |||

| | pages=585–590 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite journal | |||

| | pmid = 14384489 | |||

| | last = Auster | |||

| | first = F. | |||

| | year = 1955 | |||

| | title = 200th Anniversary of the birth of Dr. Samuel Hahnemann, born April 10, 1755 | |||

| | language = de | |||

| | volume = 94 | |||

| | issue = 4 | |||

| |journal = Pharmazeutische Zentralhalle für Deutschland | |||

| | pages = 124–128 | |||

| }} | |||

| {{refend}} | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| {{Commons}} | |||

| {{Wikiquote}} | |||

| {{EB1911 poster|Hahnemann, Samuel Christian Friedrich}} | |||

| * {{OL author}} | |||

| * A historical overview | |||

| * former site of the Hahnemann Hospital, Liverpool | |||

| * {{Cite AmCyc|wstitle=Hahnemann, Samuel Christian Friedrich |short=x}} | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| {{Homeopathy}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Hahnemann, Samuel}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| Centro Di Medicina Omeopatica Napoletano | |||

| ] | |||

| {{homoeopathy}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 01:03, 20 November 2024

German physician who created homeopathy (1755–1843)

| Samuel Hahnemann | |

|---|---|

Hahnemann in 1841 Hahnemann in 1841 | |

| Born | Christian Friedrich Samuel Hahnemann (1755-04-10)10 April 1755 Meissen, Electorate of Saxony |

| Died | 2 July 1843(1843-07-02) (aged 88) Paris, France |

| Nationality | German |

| Known for | Homeopathy |

| Signature | |

Christian Friedrich Samuel Hahnemann (/ˈhɑːnəmən/ HAH-nə-mən, German: [ˈzaːmueːl ˈhaːnəman]; 10 April 1755 – 2 July 1843) was a German physician, best known for creating the pseudoscientific system of alternative medicine called homeopathy.

Early life

Christian Friedrich Samuel Hahnemann was born in Meissen, Saxony, near Dresden. His father Christian Gottfried Hahnemann was a painter and designer of porcelain, for which the town of Meissen is famous.

As a young man, Hahnemann became proficient in a number of languages, including English, French, Italian, Greek and Latin. He eventually made a living as a translator and teacher of languages, gaining further proficiency in "Arabic, Syriac, Chaldaic and Hebrew".

Hahnemann studied medicine for two years at Leipzig. Citing Leipzig's lack of clinical facilities, he moved to Vienna, where he studied for ten months. His medical professors in Leipzig and Vienna included the physician Joseph von Quarin, later credited for turning Vienna General Hospital into a model European medical institution.

After one term of further study, Hahnemann graduated with a medical degree with honors from the University of Erlangen on 10 August 1779. His poverty may have forced him to choose Erlangen, as the school's fees were lower than in Vienna. Hahnemann's thesis was titled Conspectus adfectuum spasmodicorum aetiologicus et therapeuticus .

Medical practice

In 1781, Hahnemann took a village doctor's position in the copper-mining area of Mansfeld, Saxony. He soon married Johanna Henriette Kuchler and would eventually have eleven children. After abandoning medical practice, and while working as a translator of scientific and medical textbooks, he translated fifteen books from English, six from French and one each from Latin and Italian from 1777 to 1806. Hahnemann travelled around Saxony for many years, staying in many different towns and villages for varying lengths of time, never living far from the River Elbe and settling at different times in Dresden, Torgau, Leipzig and Köthen (Anhalt) before finally moving to Paris in June 1835.

Creation of homeopathy

Main article: HomeopathyHahnemann was dissatisfied with the state of medicine in his time, and particularly objected to practices such as bloodletting. He claimed that the medicine he had been taught to practice sometimes did the patient more harm than good:

My sense of duty would not easily allow me to treat the unknown pathological state of my suffering brethren with these unknown medicines. The thought of becoming in this way a murderer or malefactor towards the life of my fellow human beings was most terrible to me, so terrible and disturbing that I wholly gave up my practice in the first years of my married life and occupied myself solely with chemistry and writing.

After giving up his practice around 1784, Hahnemann made his living chiefly as a writer and translator, while resolving also to investigate the causes of medicine's alleged errors. While translating William Cullen's A Treatise on the Materia Medica, Hahnemann encountered the claim that cinchona, the bark of a Peruvian tree, was effective in treating malaria because of its astringency. Hahnemann believed that other astringent substances are not effective against malaria and began to research cinchona's effect on the human body by self-application. Noting that the drug induced malaria-like symptoms in himself, he concluded that it would do so in any healthy individual. This led him to postulate a healing principle: "that which can produce a set of symptoms in a healthy individual, can treat a sick individual who is manifesting a similar set of symptoms." This principle, like cures like, became the basis for an approach to medicine which he gave the name homeopathy. He first used the term homeopathy in his essay Indications of the Homeopathic Employment of Medicines in Ordinary Practice, published in Hufeland's Journal in 1807.

Development of homeopathy

Following up the work of the Viennese physician Anton von Störck, Hahnemann tested substances for the effects they produced on a healthy individual, presupposing (as von Störck had claimed) that they may heal the same ills that they caused. His researches led him to agree with von Störck that the toxic effects of ingested substances are often broadly parallel to certain disease states, and his exploration of historical cases of poisoning in the medical literature further implied a more generalised medicinal "law of similars". He later devised methods of diluting the drugs he was testing in order to mitigate their toxic effects. He claimed that these dilutions, when prepared according to his technique of "potentization" using dilution and succussion (vigorous shaking), were still effective in alleviating the same symptoms in the sick. His more systematic experiments with dose reduction really commenced around 1800–01 when, on the basis of his "law of similars," he had begun using Ipecacuanha for the treatment of coughs and Belladonna for scarlet fever.

He first published an article about the homeopathic approach in a German-language medical journal in 1796. Following a series of further essays, he published in 1810 "Organon of the Rational Art of Healing", followed over the years by four further editions entitled The Organon of the Healing Art, the first systematic treatise and containing all his detailed instructions on the subject. A 6th Organon edition, unpublished during his lifetime, and dating from February 1842, was only published many years after his death. It consisted of a 5th Organon containing extensive handwritten annotations. The Organon is widely regarded as a remodelled form of an essay he published in 1806 called "The Medicine of Experience", which had been published in Hufeland's Journal. Of the Organon, Robert Ellis Dudgeon states it "was an amplification and extension of his "Medicine of Experience", worked up with greater care, and put into a more methodical and aphoristic form, after the model of the Hippocratic writings."

Coffee theory of disease

Around the start of the nineteenth century Hahnemann developed a theory, propounded in his 1803 essay On the Effects of Coffee from Original Observations, that many diseases are caused by coffee. Hahnemann later abandoned the coffee theory in favour of the theory that disease is caused by Psora, but it has been noted that the list of conditions Hahnemann attributed to coffee was similar to his list of conditions caused by Psora.

Later life

In early 1811 Hahnemann moved his family back to Leipzig with the intention of teaching his new medical system at the University of Leipzig. As required by the university statutes, to become a faculty member he was required to submit and defend a thesis on a medical topic of his choice. On 26 June 1812, Hahnemann presented a Latin thesis, entitled "A Medical Historical Dissertation on the Helleborism of the Ancients." His thesis very thoroughly examined the historical literature and sought to differentiate between the ancient use of Helleborus niger, or black hellebore, and the medicinal uses of the "white hellebore", botanically Veratrum album, both of which are poisonous plants.

Hahnemann continued practicing and researching homeopathy, as well as writing and lecturing for the rest of his life. He died in 1843 in Paris, at 88 years of age, and is entombed in a mausoleum at Paris's Père Lachaise Cemetery.

Descendants

Hahnemann's daughter, Amelie (1789–1881), had a son: Leopold Suss-Hahnemann. Leopold emigrated to England, and he practised homeopathy in London. He retired to the Isle of Wight and died there at the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Dr Leopold Suss-Hahnemann's youngest daughter, Amalia, had two children, Winifred (born in 1898) and Herbert. William Herbert Tankard-Hahnemann (1922–2009) was Winifred's son. He served as a Major in the British Army during World War II, and then had a career in the city of London. He was at one point appointed as a Freeman of the City of London. Mr William Herbert Tankard-Hahnemann, the great-great-great-grandson of Samuel Hahnemann died on 12 January 2009 (his 87th birthday) after 22 years of active patronage of the British Institute of Homeopathy. The William Tankard-Hahnemann line continues with his son, Charles.

Writings

Hahnemann wrote a number of books, essays, and letters on the homeopathic method, chemistry, and general medicine:

- Heilkunde der Erfahrung. Norderstedt 2010, ISBN 3-8423-1326-8

- Versuch über ein neues Prinzip zur Auffindung der Heilkräfte der Arzneisubstanzen, nebst einigen Blicken auf die bisherigen [Essay on a New Principle for Ascertaining the Curative Powers of Drugs] (in German). 1796. reprinted in Versuch über ein neues Prinzip zur Auffindung der Heilkräfte der Arzneisubstanzen, nebst einigen Blicken auf die bisherigen. Haug. 1988. ISBN 3-7760-1060-6.

- Fragmenta de viribus medicamentorum positivis sive in sano corpore humano obeservitis, a collection of 27 drug "provings" published in Latin in 1805.

- The Organon of the Healing Art (1810), a detailed delineation of what he saw as the rationale underpinning homeopathic medicine, and guidelines for practice. Hahnemann published the 5th edition in 1833; a revised draft of this (1842) was discovered after Hahnemann's death and finally published as the 6th edition in 1921.

- Materia Medica Pura, a compilation of "homoeopathic proving" reports, published in six volumes between vol. I in 1811 and vol. VI in 1821; second edition of vol. I to Vol. VI from 1822 to 1827 and third revised editions of volumes I and II were published in 1830 and 1833, respectively.

- Chronic Diseases (1828), an explanation of the root and cure of chronic disease according to the theory of miasms, together with a compilation of "homoeopathic proving" reports, published in five volumes during the 1830s.

- The Friend of Health, in which Hahnemann "recommended the use of fresh air, bed rest, proper diet, sunshine, public hygiene and numerous other beneficial measures at a time when many other physicians considered them of no value."

- Appeal to Thinking Philanthropist Respecting the Mode of Propagation of the Asiatic Choler, in which Hahnemann describes cholera physicians and nurses as the "certain and frequent propagators" of cholera and that whilst deriding nurses' "fumigations with chlorine", promoted the use of "drops of camphorated spirit" as a cure for the disease.

- Hahnemann also campaigned for the humane treatment of the insane in 1792.

- John Henry Clarke wrote that "In 1787, Hahnemann discovered the best test for arsenic and other poisons in wine, having pointed out the unreliable nature of the 'Wurtemberg test,' which had been in use up to that date."

- Samuel Hahnemanns Apothekerlexikon. Vol.2. Crusius, Leipzig 1798–1799 Digital edition by the University and State Library Düsseldorf

- Reine Arzneimittellehre. Arnold, Dresden (several editions) 1822–1827 Digital edition by the University and State Library Düsseldorf

- Systematische Darstellung der reinen Arzneiwirkungen aller bisher geprüften Mittel. Vieweg, Braunschweig 1831 – Digital edition by the University and State Library Düsseldorf

See also

Notes

- Though some sources do state that he was born in the early hours of 11 April 1755, Haehl, Richard (1922). Samuel Hahnemann his Life and Works. Vol. 1. p. 9.

Hahnemann, was born on 10 April at approximately twelve o'clock midnight.

- Ladyman J (2013). "Chapter 3: Towards a Demarcation of Science from Pseudoscience". In Pigliucci M, Boudry M (eds.). Philosophy of Pseudoscience: Reconsidering the Demarcation Problem. University of Chicago Press. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-0-226-05196-3.

Yet homeopathy is a paradigmatic example of pseudoscience. It is neither simply bad science nor science fraud, but rather profoundly departs from scientific method and theories while being described as scientific by some of its adherents (often sincerely).

- Brief History of Life of Samuel Hahnemann, The Father of Homoeopathy. Homoeoscan.com. 10 April 2014

- Coulter, Harris Livermore (1977). Divided Legacy, a History of the Schism in Medical Thought. Vol. II. Washington: Wehawken Books. p. 306. ISBN 0-916386-02-3. OCLC 67493911.

- ^ "Hahnemann Biography". Retrieved 13 January 2009.

- Martin Kaufman (1972). Homeopathy in America, the Rise and Fall of a Medical Heresy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 24. ISBN 0-8018-1238-0. OCLC 264319.

- Kuzniar, Alice A. (2017). The Birth of Homeopathy out of the Spirit of Romanticism. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1487521264.

- Austria-Forum (biography)

- Haehl, vol. 1, p. 24.

- Cook, p. 36.

- Richard Haehl (1922). Samuel Hahnemann His Life and Work. Vol. 2. London: Homoeopathic Publishing. p. 11. OCLC 14558215.

- Haehl, vol. 1, p. 26.

- Bradford, pp. 515–16.

- Cook, pp. 83–4,

- Cook, p. 168.

- Haehl, vol. 1, p.38; Dudgeon, p.48

- Gumpert, Martin (1945) Hahnemann: The Adventurous Career of a Medical Rebel, New York: Fischer, p. 130.

- Dudgeon, pp.xxi–xxii; Cook, p.95

- Dudgeon, p.49 & p.176; Haehl, vol. 1, p.40

- Cook, pp.96–7; Dudgeon, pp.338–340 & pp.394–408

- Sixth Organon book review Archived 21 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Minimum.com. Retrieved on 16 May 2012.

- Dudgeon, R. E. (1853) Lectures on the Theory and Practice of Homeopathy, London: Henry Turner, p. xxxi.

- Hahnemann S (1803): On the Effects of Coffee from Original Observations, in Hahnemann S., Dudgeon R. E. (ed) (1852): The Lesser Writings of Samuel Hahnemann. New York: William Radde, p. 391.

- Morrell, P. (1996): On Hahnemann's coffee theory, www.homeoint.org

- Bradford, p. 76.

- Bradford, p. 93.

- Haehl, Vol. 2, p. 96.

- Fragmenta de viribus medicamentorum positivis, sive in sano corpore humano observatis (in Latin). Typis observatoris medici. 1824. OCLC 14852975.

- Übersetzung der 'Fragmenta de viribus medicamentorum' von Marion Wettemann (PDF) (in German). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 April 2008.

- "Fragmenta de viribus" and "Materia Medica Pura" full-text in French. Homeoint.org. Retrieved on 16 May 2012.

- Online etext of Hahnemann's Organon der Heilkunst.

- Organon of Homeopathy, 6th version Archived 29 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine English version, full text online; German original (other format); English translation Archived 13 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Homeopathyhome.com. Retrieved on 16 May 2012.

- Bradford, TL. "The Life and Letters of Dr Samuel Hahnemann". HOMÉOPATHE INTERNATIONAL. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- Rothstein, William G. (1992). American physicians in the nineteenth century: from sects to science. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-8018-4427-0.

- Hahnemann, Samuel (1792). The Friend of Health.

- Hahnemann, Samuel (1831). "Appeal to thinking philanthropist respecting the mode of propagation of the Asiatic choler". The lesser writings of Samuel Hahnemann. William Radde. pp. 753–763. OCLC 3440881.

- Hahnemann, Samuel (1796). "Description of Klockenbring During his Insanity". The lesser writings of Samuel Hahnemann. William Radde. OCLC 3440881.

- John Henry Clarke (1894). Homoeopathy: all about it; or, The principle of cure. London: Homoeopathic Publishing. OCLC 29160937.

- Haehl, Vol. 1, p. 34.

References

- Bradford, Thomas Lindsley (1999) . The Life and Letters of Samuel Hahnemann. Philadelphia: Boericke & Tafel. OCLC 1489955.

- Cook, Trevor (1981). Samuel Hahnemann Founder of Homeopathy. Wellingborough, Northamptonshire: Thorsons. ISBN 0-7225-0689-9.

- Haehl, Richard; Wheeler, Marie L. (tr.) and Grundy, W.H.R. (tr.) (1922). John Henry Clarke, Francis James Wheeler (ed.). Samuel Hahnemann his Life and Work. Vol. 1. London: Homoeopathic Publishing. OCLC 222833661.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link), reprinted as ISBN 81-7021-693-1

Further reading

- Brockmeyer, Bettina (2007). "Representations of illness in letters addressed to Samuel Hahnemann: gender and historical perspectives". Medizin, Gesellschaft, und Geschichte: Jahrbuch des Instituts für Geschichte der Medizin der Robert Bosch Stiftung (in German). 29: 211–221, 259. PMID 18354994.

- Kayne, Steven (2006). "Samuel Hahnemann (1755–1843): the founder of modern homeopathy". Pharmaceutical Historian. 36 (2 Suppl): S23–6. PMID 17153748.

- Brockmeyer, Bettina (2005). "Writing about oneself and others: men and women in letters to doctor Samuel Hahnemann 1831–1835". Würzburger medizinhistorische Mitteilungen / Im Auftrage der Würzburger medizinhistorischen Gesellschaft und in Verbindung mit dem Institut für Geschichte der Medizin der Universität Würzburg (in German). 24: 18–28. PMID 17153289.

- "Biographic synopsis on Samuel Hahnemann". Revista de enfermería (Barcelona, Spain) (in Spanish). 28 (3): 10–16. 2005. PMID 15871338.

- Eschenbruch, Nicholas (2005). "Rationalist, magician, scharlatan? Samuel Hahnemann and homeopathy from the viewpoint of homeopathy". Schweiz. Rundsch. Med. Prax. (in German). 94 (11): 443–446. PMID 15822443.

- Jutte, R. (1999). ""Thus it passes from the patient's purse into that of the doctor without causing displeasure" – Samuel Hahnemann and medical fees". Medizin, Gesellschaft, und Geschichte: Jahrbuch des Instituts für Geschichte der Medizin der Robert Bosch Stiftung (in German). 18: 149–167. PMID 11624613.

- de Goeij, C. M. (1994). "Samuel Hahnemann: an indignant systems builder". Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde (in Dutch). 138 (6): 310–314. PMID 8121514.

- Rizza, E. (1994). "Samuel Hahnemann: a mystical empiricist. A study of the origin and development of the homeopathic medical system". Medicina Nei Secoli (in Italian). 6 (3): 515–524. PMID 11620590.

- Meissner, M. (1992). "Samuel Hahnemann—the originator of homeopathic medicine". Krankenpflege Journal. 30 (7–8): 364–366. PMID 1405462.

- Schmidt, J. M. (1988). "The publications of Samuel Hahnemann". Sudhoffs Archiv. 72 (1): 14–36. PMID 2970128.

- Lozowski, J. (1982). "Homeopathy (Samuel Hahnemann)". Pielȩgniarka I Połozna (in Polish) (4–5): 16–17. PMID 6750668.

- Habacher, M. (1980). "Homöopathische Fernbehandlung durch Samuel Hahnemann". Medizinhistorisches Journal (in German). 15 (4): 385–391. PMID 11610925.

- Antall, J.; Kapronczay, K. (1973). "Samuel Hahnemann". Orvosi Hetilap. 114 (32): 1945–1947. PMID 4581537.

- Hodges, P. C. (1964). "Homeopathy and Christian Friedrich Samuel Hahnemann". Postgraduate Medicine. 35: 666–668. doi:10.1080/00325481.1964.11695164. PMID 14143315.

- Dietrich, H. J. (1958). "Hahnemann's capacity for greatness; Samuel Hahnemann; and Hahnemann Medical College". The Hahnemannian. 93 (2): 35–39. PMID 13562700.

- Koch, E. (1955). "On the 200th anniversary of Dr. Samuel Hahnemann; several ideas concerning homeopathy". Das Deutsche Gesundheitswesen (in German). 10 (16): 585–590. PMID 14379841.

- Auster, F. (1955). "200th Anniversary of the birth of Dr. Samuel Hahnemann, born April 10, 1755". Pharmazeutische Zentralhalle für Deutschland (in German). 94 (4): 124–128. PMID 14384489.

External links

- Works by Samuel Hahnemann at Open Library

- Christian Friedrich Samuel Hahnemann A historical overview

- Hahnemann Building, Hope Street, Liverpool former site of the Hahnemann Hospital, Liverpool

- "Hahnemann, Samuel Christian Friedrich" . The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- A digitized copy of Hahnemann's personal 5th edition with handwritten notes for the 6th edition

- Brief History of life of Samuel Hahnemann

| Topics in homeopathy | |

|---|---|

| Workbooks | |

| Historical documents | |

| Homeopaths |

|

| Organizations | |

| Related | |

| Criticism | |

| See also | |

- 1755 births

- 1843 deaths

- People from Meissen

- People from the Electorate of Saxony

- 18th-century German physicians

- German homeopaths

- 18th-century writers in Latin

- 18th-century German male writers

- 19th-century writers in Latin

- University of Erlangen-Nuremberg alumni

- Academic staff of Leipzig University

- Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery