| Revision as of 22:29, 23 February 2007 edit170.173.0.1 (talk) →Second visit to italy← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 06:42, 8 December 2024 edit undoCarsharing R300 (talk | contribs)339 editsmNo edit summary | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|German painter, printmaker and theorist (1471–1528)}} | |||

| {{Infobox Artist | |||

| {{use dmy dates|date=May 2020}} | |||

| | bgcolour = #EEDD82 | |||

| {{Infobox artist | |||

| | name = Albrecht Dürer | |||

| | name = Albrecht Dürer | |||

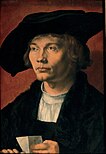

| | image = Durer self portarit 28.jpg | |||

| | image = Albrecht Dürer, Selbstbildnis mit 26 Jahren (Prado, Madrid).jpg | |||

| | imagesize = 250px | |||

| | caption |

| caption = Dürer's '']'' at ] | ||

| | birth_name = | |||

| | birthname = Albrecht Dürer | |||

| | other_names = {{hlist|Adalbert Ajtósi|Albrecht Durer|Albrecht Duerer}} | |||

| | birthdate = ], ] | |||

| | birth_date = {{Birth date|1471|05|21|df=yes}} | |||

| | location = ], ] | |||

| | birth_place = ], ], ] | |||

| | deathdate = ], ] | |||

| | death_date = {{Death date and age|1528|4|6|1471|5|21|df=y}} | |||

| | deathplace = ], ] | |||

| | death_place = Nuremberg, Free Imperial City of Nuremberg, Holy Roman Empire | |||

| | nationality = ] | |||

| | nationality = ] | |||

| | field = ], ] | |||

| | movement = {{hlist|]|]}} | |||

| | training = | |||

| | |

| buried_in = | ||

| | field = {{hlist |] |]}} | |||

| | famous works = '']'' (1513) | |||

| | works = {{hlist|]|]|]}} | |||

| '']'' (1514) | |||

| | spouse = {{marriage|]|1494}} | |||

| '']'' (1514) | |||

| | module = {{Infobox person|child=yes | |||

| '']'' | |||

| | signature = Signatur Albrecht Dürer.PNG}} | |||

| | patrons = | |||

| | awards = | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Albrecht Dürer''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|dj|ʊər|ər}} {{respell|DURE|ər}},<ref name="LPD">{{citation|last=Wells|first=John C.|year=2008|title=Longman Pronunciation Dictionary|edition=3rd|publisher=Longman|isbn=978-1405881180}}</ref> {{IPA|de|ˈalbʁɛçt ˈdyːʁɐ|lang}};<ref>{{cite web|url=https://de.langenscheidt.com/franzoesisch-deutsch/search?term=Albrecht|title=Albrecht – Deutsch – Langenscheidt Französisch-Deutsch Wörterbuch|publisher=]|access-date=22 October 2018|language=de, fr}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.duden.de/rechtschreibung/Duerer|title=Duden {{!}} Dürer {{!}} Rechtschreibung, Bedeutung, Definition|work=]|access-date=22 October 2018|language=de}}</ref><ref name="LPD"/> 21 May 1471 – 6 April 1528),<ref name=Mueller>Müller, Peter O. (1993) ''Substantiv-Derivation in Den Schriften Albrecht Dürers'', Walter de Gruyter. {{ISBN|3-11-012815-2}}.</ref> sometimes spelled in English as '''Durer''', was a German ], ], and ] of the ]. Born in ], Dürer established his reputation and influence across Europe in his twenties due to his high-quality ]. He was in contact with the major Italian artists of his time, including ], ] and ], and from 1512 was patronized by ] ]. | |||

| '''Albrecht Dürer''' (] /al.'brɛxt dyr.'ər/) (], ] – ], ]) <ref name=Mueller>Mueller, Peter O. (1993) ''Substantiv-Derivation in Den Schriften Albrecht Durers'', Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-012815-2.</ref> was a ] ], ], ], and, with ] and ], the greatest creator of ]s. He was born and died in ], ] and is best known for his ], often executed as in series, including the ''Apocalypse'' (1498) and his two series on the passion of Christ, the ''Great Passion'' (1498–1510) and the ''Little Passion'' (1510–1511). Dürer's best known individual ]s include '']'' (1513), '']'' (1514) and '']'' (1514), which has been the subject of the extensive analysis and speculation. His most iconic images are this, his woodcuts of the '']'' (1497–1498) from the ''Apocalypse'' series, his "]", and his numerous self-portraits. Durer probably did not cut his own woodblocks but employed a skilled carver who followed his drawings faithfully.<ref name="Bartrum">Giulia Bartrum, "Albrecht Dürer and his Legacy", British Museum Press, 2002, ISBN 0714126330</ref> | |||

| Dürer's vast body of work includes ]s, his preferred technique in his later prints, altarpieces, portraits and self-portraits, ]s and books. The woodcuts series are stylistically more ] than the rest of his work, but revolutionised the potential of that medium, while his extraordinary handling of the ] expanded especially the tonal range of his engravings; well-known engravings include the three '']'' (master prints) '']'' (1513), '']'' (1514), and '']'' (1514). His watercolours mark him as one of the first European ], and with his confident self-portraits he pioneered them as well as autonomous subjects of art. | |||

| == Early life == | |||

| ] ], ]]] | |||

| Dürer was born on ], ], the third child and second son of fourteen to eighteen children. His father was a successful ], originally named Ajtósi, who in 1455 had moved to Nuremberg from Ajtós, near ] in ]. The German name "Dürer" is derived from the , "Ajtósi". Initially, it was "Thürer," meaning doormaker, which is "ajtós" in Hungarian (from "ajtó" meaning door). A door featured in the ] the family acquired. Albrecht Dürer the Elder married Barbara Holper, from bird Nuremberg family, in 1467. | |||

| Dürer's introduction of ] and of the ] into Northern art, through his knowledge of ] and ], has secured his reputation as one of the most important figures of the ]. This is reinforced by his theoretical treatises, which involve principles of mathematics for ] and ]. | |||

| His godfather was ], who left ]ing to become a printer and publisher in the year of Dürer's birth. He quickly became the most successful publisher in Germany, eventually owning twenty-four ]es and having many offices in Germany and abroad. His most famous publication was the ], published in 1493 in German and Latin editions. It contained an unprecedented 1,809 ] illustrations (with many repeated uses of the same block) by the ] workshop. Albrecht Dürer may well have worked on some of these, as the work on the project began while he was with Wolgemut.<ref name="Bartrum"/> | |||

| ==Biography== | |||

| It is fortunate Dürer left autobiographical notes and that he became very famous by his mid-twenties. Because of this, his life is well documented from a number of sources. After a few years of school, Dürer started to learn the basics of ]ing and drawing from his father. Though his father wanted him to continue his training as a goldsmith, he showed such a precocious talent in drawing that he started as an apprentice to ] at the age of fifteen in ]. A superb self-portrait, a ] in ], is dated 1484 (]) “when I was a child”, as his later inscription says. Wolgemut was the leading artist in Nuremberg at the time, with a large workshop producing a variety of works of art, in particular woodcuts for books. Nuremberg was a prosperous city, a centre for publishing and many luxury trades. It had strong links with ], especially ], a relatively short distance across the ].<ref name="Bartrum"/> | |||

| ===Early life (1471–1490)=== | |||

| ] ] drawing by the thirteen-year-old Dürer, 1484. ], Vienna.]] | |||

| Dürer was born on 21 May 1471, the third child and second son of Albrecht Dürer the Elder and Barbara Holper, who married in 1467.<ref name="BPA11">Brand Philip & Anzelewsky (1978–79), 11.</ref><ref name=":0" /> Albrecht Dürer the Elder (originally Albrecht Ajtósi) was a successful ] who by 1455 had moved to Nuremberg from ], near ] in ].<ref name="heaton">{{Cite book|last=Heaton|first=Mrs. Charles|url=https://archive.org/details/lifeofalbrechtdu00heat|title=The Life of Albrecht Dürer of Nürnberg: With a Translation of His Letters and Journal and an Account of His Works|publisher=Seeley, Jackson and Halliday|year=1881|location=London|pages=, 31–32|author-link=Mary Margaret Heaton}}</ref> He married Barbara, his master's daughter, when he himself qualified as a master.<ref name=":0" /> Her mother, Kinga Öllinger had some roots in Hungary too,<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/essays/albrecht-durer-1471-1528-and-hungary/ | title=Albrecht Dürer (1471 -1528) and Hungary - Hungarian-Ottoman Wars | date=4 May 2020 }}</ref> as she was born in ]. The couple had eighteen children together, of which only three survived. ] (1490–1534), also became a painter, trained under the older Albrecht. The other surviving brother, Endres Dürer (1484–1555), took over their father's business and was a master goldsmith.<ref name="Br16">Brion (1960), 16.</ref> The German name "Dürer" is a translation from the Hungarian, "Ajtósi".<ref name="heaton"/> Initially, it was "Türer", meaning doormaker, which is "ajtós" in Hungarian (from "ajtó", meaning door). A door is featured in the ] the family acquired. Albrecht Dürer the Younger later changed "Türer", his father's diction of the family's surname, to "Dürer", to adapt to the local Nuremberg dialect.<ref name=":0">Bartrum, 93, n. 1.</ref> | |||

| == Gap year, or four == | |||

| After completing his term of apprenticeship in 1489, Dürer followed the common German custom of taking "wanderjahre" — in effect a ] — however Dürer was away nearly four years, travelling through Germany, ], and probably, the Netherlands. To his great regret, he missed meeting ], the leading engraver of Northern Europe, who had died shortly before Dürer's arrival. He was very hospitably treated by Schongauer's brother, and seems at this time to have acquired some works by Schongauer he is known to have owned. His first painted self-portrait (now in the ]) was painted in ], probably to be sent back to his fiancé in Nuremberg.<ref name="Bartrum"/> | |||

| Because Dürer left autobiographical writings and was widely known by his mid-twenties, his life is well documented in several sources. After a few years of school, Dürer learned the basics of goldsmithing and drawing from his father. Though his father wanted him to continue his training as a goldsmith, he showed such a precocious talent in drawing that he was allowed to start as an apprentice to ] at the age of fifteen in 1486.<ref name="BPA10">Brand Philip & Anzelewsky (1978–79), 10.</ref> A self-portrait, a drawing in ], is dated 1484 (]) "when I was a child", as his later inscription says. The drawing is one of the earliest surviving children's drawings of any kind, and, as Dürer's Opus One, has helped define his oeuvre as deriving from, and always linked to, himself.<ref name="Koerner">], ''The Moment of Self-Portraiture in Renaissance Art'', University of Chicago Press, 1993.</ref> Wolgemut was the leading artist in Nuremberg at the time, with a large workshop producing a variety of works of art, in particular woodcuts for books. Nuremberg was then an important and prosperous city, a centre for publishing and many luxury trades. It had strong links with ], especially ], a relatively short distance across the ].<ref name="Bartrum"/> | |||

| == Marriage and first visit to Italy == | |||

| ] Very soon after his return to Nuremberg, on ], ], at the age of 23, Dürer was married to Agnes Frey following an arrangement made during his absence. She was the daughter of a prominent brass worker (and amateur harpist) in the city. The nature of his relationship with his wife is unclear, but it would not seem to have been a love-match, and his portraits of her lack warmth. They had no children. Within three months Dürer left again for Italy, alone, perhaps stimulated by an outbreak of plague in Nuremberg. He made ] sketches as he traveled over the Alps. Some have survived and others may be deduced from accurate landscapes of real places in his later work, for example his engraving ''Nemesis''. These are the first pure landscape studies known in Western art.<ref name="Bartrum"/> | |||

| Dürer's godfather ] left goldsmithing to become a printer and publisher in the year of Dürer's birth. He became the most successful publisher in Germany, eventually owning twenty-four ]es and a number of offices in Germany and abroad. Koberger's most famous publication was the '']'', published in 1493 in German and Latin editions. It contained an unprecedented 1,809 ] illustrations (albeit with many repeated uses of the same block) by the Wolgemut workshop. Dürer may have worked on some of these, as the work on the project began while he was with Wolgemut.<ref name="Bartrum">], ''Albrecht Dürer and his Legacy'', British Museum Press, 2002, {{ISBN|0-7141-2633-0}}.</ref> | |||

| In Italy, he went to ] to study its more advanced artistic world.<ref name=Lee>Lee, Raymond L. & Alistair B. Fraser. (2001) ''The Rainbow Bridge'', Penn State Press. ISBN 0-271-01977-8.</ref> Through Wolgemut's tutelage, Dürer had learned how to make prints in ] and design ]s in the German style, based on the works of ] and the ].<ref name=Lee />. He also would have had access to some Italian works in Germany, but the two visits he made to Italy had an enormous influence on him. He wrote that ] was the oldest and still the best of the artists in Venice. His drawings and engravings show the influence of others, notably ] with his interest in the proportions of the body, ], ] and others. Dürer probably visited ] and ] on this trip also. | |||

| ===''Wanderjahre'' and marriage (1490–1494)=== | |||

| == Return to Nuremberg == | |||

| ]'' (1493) by Albrecht Dürer, oil, originally on ] (], ])]] | |||

| ] | |||

| On his return to Nuremberg in 1495, Dürer opened his own workshop (being married was a requirement for this). Over the next five years his style increasingly integrated Italian influences into underlying Northern forms. Dürer lost both of his parents during the next decade. His father died in 1502 and his mother died in 1513.<ref name=Allen>Allen, L. Jessie. (1903) ''Albrecht Dürer'', Methuen & co.</ref> His best works in the first years of the workshop were his ] prints, mostly religious, but including secular scenes such as, ''The Mens Bath-house'' (c1496). These were larger than the great majority of German woodcuts hitherto, and far more complex and balanced in composition. | |||

| After completing his apprenticeship, Dürer followed the common German custom of taking '']''—in effect ]s—in which the apprentice learned skills from other masters, their local tradition and individual styles; Dürer was to spend about four years away. He left in 1490, possibly to work under ], the leading engraver of Northern Europe, but who died shortly before Dürer's arrival at ] in 1492. It is unclear where Dürer travelled in the intervening period, though it is likely that he went to ] and the ]. In Colmar, Dürer was welcomed by Schongauer's brothers, the goldsmiths Caspar and Paul and the painter Ludwig. Later that year, Dürer travelled to ] to stay with another brother of Martin Schongauer, the goldsmith Georg.{{refn|Here he produced a woodcut of ] as a frontispiece for Nicholaus Kessler's ''Epistolare beati Hieronymi''. ] argues that this print combined the "]ian style" of Koberger's ''Lives of the Saints'' (1488) and that of Wolgemut's workshop. Panofsky (1945), 21|group=n}} In 1493 Dürer went to ], where he would have experienced the sculpture of ]. Dürer's first painted self-portrait (now in the ]) was painted at this time, probably to be sent back to his fiancée in Nuremberg.<ref name="Bartrum"/> | |||

| It is now thought unlikely that Dürer cut any of the woodblocks; this task would have been left for a specialist craftsman. His training in Wolgemut's studio, which made many carved and painted altarpieces, and both designed and cut woodblocks for ], however, evidently gave him great understanding of what the technique could be made to produce, and how to work with block cutters. Dürer either drew his design directly onto the woodblock itself, or glued a paper drawing to the block. Either way his drawing was destroyed during the cutting of the block. | |||

| ] | |||

| His famous series of sixteen great designs for the ''Apocalypse'' are dated 1498. He made the first seven scenes of the ''Great Passion'' in the same year, and a little later, a series of eleven on the Holy Family and saints. Around 1503–1505 he produced the first seventeen of a set illustrating the life of the Virgin, which he did not finish for some years. Neither these, nor the ''Great Passion,'' were published as sets until several years later, but prints were sold individually in considerable numbers.<ref name="Bartrum"/> | |||

| ] | |||

| During the same period Dürer trained himself in the difficult art of using the ] to make ]s. Perhaps he had begun learning this skill during his early training with his father. The first few were relatively unambitious, but by 1496 he was able to produce the masterpiece, the ''Prodigal Son,'' which ] singled out for praise some decades later, noting its Germanic quality. He was soon producing some spectacular and original images, notably, ''Nemesis'' (1502), ''The Sea Monster'' (1498), and ''Saint Eustace'' (1501), with a highly detailed landscape background and beautiful animals. He made a number of ]s, single religious figures, and small scenes with comic peasant figures. Prints are highly portable and these works made Dürer famous throughout the main artistic centres of Europe within a very few years.<ref name="Bartrum"/> | |||

| Very soon after his return to Nuremberg, on 7 July 1494, at the age of 23, Dürer was married to ] following an arrangement made during his absence. Agnes was the daughter of a prominent brass worker (and amateur harpist) in the city. However, no children resulted from the marriage, and with Albrecht the Dürer name died out. The marriage between Agnes and Albrecht was believed not to be a generally happy one, as indicated by a letter of Dürer in which he quipped to ] in a rough tone about his wife, calling her an "old crow" and made other vulgar remarks. Pirckheimer also made no secret of his antipathy towards Agnes, describing her as a miserly shrew with a bitter tongue, who helped cause Dürer's death at a young age.<ref name="Wilmot-BuxtonPoynter1881">{{cite book|author1=Harry John Wilmot-Buxton|author2=Edward John Poynter|title=German, Flemish and Dutch Painting|url=https://archive.org/details/germanflemishan00bargoog|year=1881|publisher=Scribner and Welford|page=}}</ref> It has been hypothesized by many scholars that Albrecht was bisexual or homosexual, due to the recurrence of allegedly homoerotic themes in some of his works (e.g. ''The Men's Bath''), and the nature of his correspondence with close friends.<ref name="Haggerty2013">{{cite book|author=George Haggerty|title=Encyclopedia of Gay Histories and Cultures|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Pez9AQAAQBAJ|date=2013|publisher=Taylor & Francis|isbn=978-1-135-58513-6|page=262}}</ref><ref>Brisman, Shira, ''Albrecht Dürer and the Epistolary Mode of Address'', University of Chicago Press, 2017, p. 179.</ref><ref>Mills, Robert, ''Seeing Sodomy in the Middle Ages'', University of Chicago Press, 2015, p. 332, n. 93.</ref><!--One might consider the Women's Bath as an immidiate counter argument, with a man as a voyeur. The joke with the water cock is childish, not especially homoerotic. And: what other works?--> | |||

| The Venetian artist ], whom Dürer had met in Venice, visited Nuremberg in 1500, and Dürer said that he learned much about the new developments in ], ], and ] from him. He was unwilling to explain everything he knew, so Dürer began his own studies, which would become a lifelong preoccupation. A series of extant drawings show Dürer's experiments in human proportion, leading to the famous engraving of, '']'' (1504); showing his subtlety while using the ] in the texturing of flesh surfaces.<ref name="Bartrum"/> This is the only existing engraving signed with his full name. | |||

| ===First journey to Italy (1494–1495)=== | |||

| Dürer made large numbers of preparatory drawings, especially for his paintings and engravings, and many survive, most famously the ''Praying Hands'' (1508 ]), a study for an apostle in the Heller altarpiece. He also continued to make images in ] and ] (usually combined), including a number of exquisite still lives of meadow sections or animals, including his "]" (1502, ]). | |||

| Within three months of his marriage, Dürer left for Italy, alone, perhaps stimulated by an outbreak of ] in Nuremberg. He made watercolour sketches as he traveled over the Alps. Some have survived and others may be deduced from accurate landscapes of real places in his later work, for example his engraving ''Nemesis''. | |||

| In Italy, he went to Venice to study its more advanced artistic world.<ref name=Lee>Lee, Raymond L. & Alistair B. Fraser. (2001) ''The Rainbow Bridge'', Penn State Press. {{ISBN|0-271-01977-8}}.</ref> Through Wolgemut's tutelage, Dürer had learned how to make prints in ] and design woodcuts in the German style, based on the works of Schongauer and the ].<ref name=Lee /> He also would have had access to some Italian works in Germany, but the two visits he made to Italy had an enormous influence on him. He wrote that ] was the oldest and still the best of the artists in Venice. His drawings and engravings show the influence of others, notably ], with his interest in the proportions of the body; ]; and ], whose work he produced copies of while training.<ref>Campbell, Angela and Raftery, Andrew. "Remaking Dürer: Investigating the Master Engravings by Masterful Engraving", (November–December 2012).</ref> Dürer probably also visited ] and ] on this trip.{{refn|The evidence for this trip is not conclusive; the suggestion it happened is supported by Panofsky (1945) and is accepted by a majority of scholars, including the several curators of the large 2020–22 exhibition "Dürer's Journeys", but it has been disputed by other scholars, including Katherine Crawford Luber (in her ''Albrecht Dürer and the Venetian Renaissance,'' 2005)|group=n}} | |||

| == Second visit to italy == | |||

| In Italy, he returned to painting, at first producing them on ]. These include portraits and altarpieces, notably, the ] ] and the '']''. In early 1506, he returned to Venice and stayed there until the spring of 1507.<ref name=Mueller /> By this time Dürer's engravings had attained great popularity and were being copied. In Venice he was given a valuable commission from the emigrant German community for the church of ]. The picture painted by Dürer was closer to the Italian style—the ''Adoration of the Virgin'', also known as the ''Feast of Rose Garlands''. It was subsequently acquired by the Emperor ] and taken to ]. Other paintings Dürer produced in Venice include, ''The Virgin and Child with the Goldfinch'', ''Christ disputing with the Doctors'' (supposedly produced in a mere five days), and a number of smaller works. | |||

| == Nuremberg |

===Return to Nuremberg (1495–1505)=== | ||

| On his return to ] in 1495, Dürer opened his own workshop (being married was a requirement for this). Over the next five years, his style increasingly integrated Italian influences into underlying Northern forms. Arguably his best works in the first years of the workshop were his woodcut prints, mostly religious, but including secular scenes such as ''The Men's Bath'' ({{Circa|1496}}). These were larger and more finely cut than the great majority of German woodcuts hitherto, and far more complex and balanced in composition. | |||

| ]'']] | |||

| Despite the regard in which he was held by the Venetians, Dürer was back in Nuremberg by mid-1507. He remained in Germany until 1520. His reputation had spread throughout ]. He was on friendly terms and in communication with most of the major artists of Europe, and exchanged drawings with ]. | |||

| It is now thought unlikely that Dürer cut any of the woodblocks himself; this task would have been performed by a specialist craftsman. However, his training in Wolgemut's studio, which made many carved and painted altarpieces and both designed and cut woodblocks for woodcut, evidently gave him great understanding of what the technique could be made to produce, and how to work with block cutters. Dürer either drew his design directly onto the woodblock itself, or glued a paper drawing to the block. Either way, his drawings were destroyed during the cutting of the block. | |||

| The years between his return from Venice and his journey to the ] are divided according to the type of work with which he was principally occupied. The first five years, 1507–1511, are pre-eminently the painting years of his life. He worked with a vast number of preliminary drawings and studies and produced what have been accounted his four best works in painting, ''Adam and Eve'' (1507), ''Virgin with the Iris'' (1508), the altarpiece the ''Assumption of the Virgin'' (1509), and the ''Adoration of the Trinity by all the Saints'' (1511). During this period he also completed the two woodcut series, the ''Great Passion'' and the ''Life of the Virgin'', both published in 1511 together with a second edition of the ''Apocalypse'' series. | |||

| ] (1500). ], Munich.]] | |||

| {{commonscat|Albrecht Dürer}} | |||

| He complained that painting did not make enough money to justify the time spent, when compared to his prints, and from 1511 to 1514 concentrated on ], in ], and especially, ]. The major works he produced in this period were the thirty-seven ] subjects of the ''Little Passion'', published first in 1511, and a set of fifteen small ]s on the same theme in 1512. In 1513 and 1514 he created his three most famous ]s, ''The Knight, Death, and the Devil'' (or simply, ''The Knight'', as he called it, 1513), the enigmatic and much analyzed '']'', and ''St. Jerome in his Study'' (both 1514).<ref name="Bartrum"/> | |||

| His series of sixteen designs for the ''Apocalypse''<ref>{{cite web| url = http://www.payer.de/christentum/apokalypse.htm| title = Johannesapokalypse in klassischen Comics}}</ref> is dated 1498, as is his engraving of '']''. He made the first seven scenes of the ''Great Passion'' in the same year, and a little later, a series of eleven on the ] and saints. The '']'', commissioned by ] in 1496, was executed by Dürer and his assistants c. 1500. In 1502, Dürer's father died. Around 1503–1505 Dürer produced the first 17 of a set illustrating the '']'', which he did not finish for some years. Neither these nor the ''Great Passion'' were published as sets until several years later, but prints were sold individually in considerable numbers.<ref name="Bartrum"/> | |||

| In ']' appears a fourth-order ] which is believed to be the first seen in European art. The two numbers in the middle of the bottom row give the date of the engraving, 1514. | |||

| During the same period Dürer perfected the difficult art of using the ] to make engravings. Most likely he had learned this skill during his early training with his father, as it was also an essential skill of the goldsmith. In 1496 he executed the ''Prodigal Son'', which the Italian Renaissance art historian ] singled out for praise some decades later, noting its Germanic quality. He was soon producing some spectacular and original images, notably ''Nemesis'' (1502), ''The Sea Monster'' (1498), and ''Saint Eustace'' ({{circa|1501}}), with a highly detailed landscape background and animals. His landscapes of this period, such as ''Pond in the Woods'' and ''Willow Mill'', are quite different from his earlier watercolours. There is a much greater emphasis on capturing atmosphere, rather than depicting topography. He made a number of ]s, single religious figures, and small scenes with comic peasant figures. Prints are highly portable and these works made Dürer famous throughout the main artistic centres of Europe within a very few years.<ref name="Bartrum"/> | |||

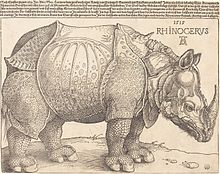

| ], ], 1515.]] | |||

| In 1515, he created a woodcut of a '']'' which had arrived in Lisbon, from a written description and brief sketch, without ever seeing the animal depicted. Despite being relatively inaccurate (the animal belonged to a now extinct Indian species), the image has such force that it remains one of his best-known, and was still being used in some German school science text-books early last century.<ref name="Bartrum"/> | |||

| The Venetian artist ], whom Dürer had met in Venice, visited Nuremberg in 1500, and Dürer said that he learned much about the new developments in ], ], and ] from him.<ref name="se" /> To Dürer it seemed that De' Barbari was unwilling to explain everything he knew, so he began his own studies, which would become a lifelong preoccupation. A series of extant drawings show Dürer's experiments in human proportion, leading to the famous engraving of '']'' (1504), which shows his subtlety while using the burin in the texturing of flesh surfaces.<ref name="Bartrum"/> This is the only existing engraving signed with his full name. | |||

| In the years leading to 1520 he produced a wide range of works, including portraits in ] on ] in 1516, engravings on many subjects, a few experiments in ] on plates of ], and parts of the ''Triumphal Arch'' and the ''Triumphs of Maximilian'' which were huge propaganda ] projects commissioned by ]. He drew marginal decorations for some pages of an edition of the Emperor's printed ]. These were quite unknown until facsimiles were published in 1808 as the first book published in ]. The decorations show a lighter, more fanciful, side to Dürer's art, as well as, his usual superb draftsmanship. He also drew a portrait of the Emperor Maximilian, shortly before his death, in 1519. | |||

| Dürer created large numbers of preparatory drawings, especially for his paintings and engravings, and many survive, most famously the '']'' (''Praying Hands'') from circa 1508, a study for an apostle in the Heller altarpiece. He continued to make images in watercolour and ] (usually combined), including a number of still lifes of meadow sections or animals, including his '']'' (1502) and the '']'' (1503). | |||

| == Journey to the Netherlands and beyond == | |||

| ], 1521, by Albrecht Dürer]] | |||

| In the summer of 1520 Dürer made his fourth, and last, journey. He sought to renew the Imperial pension Maximilian had given him (typically, instructing the city of Nuremberg to pay it), to secure new ] following the death of Maximilian, and to avoid an outbreak of sickness in Nuremberg. He, his wife, and her maid set out in July for the Netherlands in order to be present at the coronation of the new emperor, ]. He journeyed by the ] to ], and then to ], where he was well received and produced numerous drawings in ], ], and ]. Besides going to ] for the ], he made excursions to Cologne, ], ], ], ], ], and ]. In Brussels he saw "the things which have been sent to the king from the golden land" — the ] treasure that ] had sent home to ] following the fall of ]. Dürer wrote that this treasure trove "was much more beautiful to me than miracles. These things are so precious that they have been valued at 100,000 florins".<ref name="Bartrum"/> Dürer appears to have been collecting for his own ], and he sent back to Nuremberg various animal horns, a piece of ], some large fish fins, and a wooden weapon from the ]. | |||

| <gallery widths="116" heights="155"> | |||

| He took a large stock of prints with him, and wrote in his diary to whom he gave, exchanged, or sold them, and for how much. This gives rare information on the monetary value placed on ]s at this time. Unlike paintings, their sale was very rarely documented. He finally returned home in July 1521, having caught an undetermined illness which afflicted him for the rest of his life, and he greatly reduced his rate of work.<ref name="Bartrum"/> | |||

| Albrecht Dürer - The Men’s Bath - Google Art Project.jpg|The Men's Bath, {{Circa|1496}}, woodcut, 39.2 × 28.3 cm, (]) | |||

| 10 The Prodigal Son.jpg|''The Prodigal Son'' (1496), copper engraving, 24.7 × 19.1 cm (], Amsterdam) | |||

| Albrecht Dürer, Adam and Eve, 1504, Engraving.jpg|'']'' (1504), copper engraving, 29.8 × 21.1 cm (], New York) | |||

| File:Albrecht Dürer - Hare, 1502 - Google Art Project.jpg|'']'', 1502, watercolour and gouache, 25 × 22.5 cm, ] | |||

| Albrecht Dürer - The Large Piece of Turf, 1503 - Google Art Project.jpg|'']'' (1503), watercolour and gouache w/highlighting, 40,8 × 31,5 cm, Albertina | |||

| Albrecht Dürer - Praying Hands, 1508 - Google Art Project.jpg|'']'' ({{circa|1508}}), brush, ink and gray ] on blue paper, 29.1 × 19.7 cm, Albertina | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ===Second journey to Italy (1505–1507)=== | |||

| == Final years in Nuremberg == | |||

| ]'' (1506), oil on panel, 162 × 192 cm, ]]] | |||

| ] | |||

| Back in Nuremberg, Dürer began work on a series of religious pictures. Many preliminary sketches and studies survive, but no paintings on the grand scale ever were carried out. This was due in part to his declining health, but more because of the time he gave to the preparation of his theoretical works on ] and ], the proportions of men and horses, and ]. Although having little natural gift for writing, he worked diligently to produce his works. | |||

| In Italy, he returned to painting, at first producing a series of works executed in ] on ]. These include portraits and altarpieces, notably, the ] and the '']''. In early 1506, he returned to Venice and stayed there until the spring of 1507.<ref name=Mueller /> It was in Venice that he took up the material of ], which he used to execute preparatory drawing for paintings he completed there in 1505–1507.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Brahms |first=Iris |date=2023 |title=Ecologies of Blue Paper. Dürer and Beyond |url=https://doi.org/10.11588/xxi.2023.4 |journal=21: Inquiries into Art, History and the Visual |issue=4 |pages=603-638}}</ref> By this time Dürer's engravings had attained great popularity and were being copied. In Venice he was given a valuable commission from the emigrant German community for the church of ]. This was the altar-piece known as the '']'' (or the ''Feast of Rose Garlands''). It shows ] and ], peacefully kneeling in adoration before her throne, both with their crowns taken off. It also includes portraits of members of Venice's German community and of Dürer himself on the upper right holding a designation of his authorship. Besides the ] ] in the depiction of the greenery and the garments, and the use of his own hues, the altar-piece shows a strong Italian influence. It was later acquired by the Emperor ] and taken to Prague.<ref>Kotková, Olga. "'The Feast of the Rose Garlands': What Remains of Dürer?". ''The Burlington Magazine'', Volume 144, No. 1186, 2002. 4–13. {{JSTOR|889418}}</ref> | |||

| The consequence of this shift in emphasis was that during the last years of his life, Dürer produced comparatively little, as an artist. In painting there were only, a portrait of ], a ], a ], and two panels showing ] with ] in ] and ] with ] in the ]. In copper-engraving, Dürer produced only a few portraits, those of the cardinal-elector of Mainz (''The Great Cardinal''), ], elector of Saxony, and his friends the ] scholar ], ], and ]. | |||

| ===Nuremberg and the masterworks (1507–1520)=== | |||

| Despite complaining of his lack of formal education, especially in the classical languages, Dürer was greatly interested in intellectual matters, and learned much from his great friend ], whom he no doubt consulted on the content of many of his images. He also derived great satisfaction from his friendship and correspondence with ] and other scholars. Dürer succeeded in finishing and producing two books during his lifetime. One on geometry and perspective, ''The Painter's Manual'' (more literally, the ''Instructions on Measurement'') was published at Nuremberg in 1525 and it is the first book for adults to be published on ] in German.<ref name="Bartrum"/> His work on fortification was published in 1527, and his work on human proportion was brought out in four volumes shortly after his death at the age of fifty-six, in 1528.<ref name=Mueller /> | |||

| ]'' (1514), engraving]] | |||

| ]'' (1515), National Gallery of Art]] | |||

| Dürer returned to Nuremberg by mid-1507, remaining in Germany until 1520. His reputation had spread throughout Europe and he was on friendly terms and in communication with many of the major artists including ].{{refn|According to Vasari, Dürer sent Raphael a self-portrait in watercolour, and Raphael sent back multiple drawings. One is dated 1515 and has an inscription by Dürer (or one of his heirs) affirming that Raphael sent it to him. See {{cite book |last1=Salmi |first1=Mario |author1-link=Mario Salmi|last2=Becherucci |first2=Luisa |last3=Marabottini |first3=Alessandro |last4=Tempesti |first4=Anna Forlani |last5=Marchini |first5=Giuseppe |last6=Becatti |author6-link=Giovanni Becatti |first6=Giovanni |last7=Castagnoli |first7=Ferdinando |author7-link=Ferdinando Castagnoli |last8=Golzio |first8=Vincenzo |title=The Complete Work of Raphael |date=1969 |publisher=Reynal and Co., ] |location=New York |pages=278, 407}} Dürer describes ] as "very old, but still the best in painting".<ref>, The J. Paul Getty Museum.</ref>|group=n}} | |||

| It is clear from his writings that Dürer was highly sympathetic to ], and he may have been influential in the City Council declaring for Luther in 1525. However, he died before religious divisions had hardened into different churches, and may well have regarded himself as a reform-minded ] to the end. | |||

| Between 1507 and 1511 Dürer worked on some of his most celebrated paintings: '']'' (1507), '']'' (1508, for Frederick of Saxony), ''Virgin with the Iris'' (1508), the altarpiece ''Assumption of the Virgin'' (1509, for Jacob Heller of Frankfurt), and '']'' (1511, for Matthaeus Landauer). During this period he also completed two woodcut series, the ''Great Passion'' and the ''Life of the Virgin'', both published in 1511 together with a second edition of the ''Apocalypse'' series. The post-Venetian woodcuts show Dürer's development of ] modelling effects,<ref>Panofsky (1945), 135.</ref> creating a mid-tone throughout the print to which the highlights and shadows can be contrasted. Other works from this period include the thirty-seven ''Little Passion'' woodcuts, published in 1511, and a set of fifteen small engravings on the same theme in 1512. Complaining that painting did not make enough money to justify the time spent when compared to his prints,<ref>Panofsky (1945), p. 44.</ref> he produced no paintings from 1513 to 1516. In 1513 and 1514 Dürer created his three most famous ]s: '']'' (1513, probably based on ]'s '']''),<ref>"". ]. Retrieved 11 September 2020.</ref> '']'', and the much-debated '']'' (both 1514, the year Dürer's mother died).{{refn|In March of this year, two months before his mother died, he drew ].<ref>Tatlock, Lynne. ''Enduring Loss in Early Modern Germany''. Brill Academic Publishers, 2010. 116. {{ISBN|90-04-18454-6}}.</ref>|group=n}} Further outstanding pen and ink drawings of Dürer's period of art work of 1513 were drafts for his friend Pirckheimer. These drafts were later used to design ] chandeliers, combining an ] with a wooden sculpture. | |||

| He left an estate valued at 6,874 florins - a considerable sum. His large house (which he bought from the heirs of ] in 1509), where his workshop also was, and where his widow lived until her death in 1537, remains a prominent Nuremberg landmark, and is now a museum.<ref name="Bartrum"/> | |||

| In 1515, he created his '']'' which had arrived in ] from a written description and sketch by another artist, without ever seeing the animal himself. An image of the ], the image has such force that it remains one of his best-known and was still used in some German school science text-books as late as last century.<ref name="Bartrum"/> In the years leading to 1520 he produced a wide range of works, including the woodblocks for the first western printed star charts in 1515<ref>{{cite web| url = http://www.ianridpath.com/startales/durer.html| title = Dürer's hemispheres of 1515 – the first European printed star charts |work=Star Tales |first1=Ian |last1=Ridpath |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231030185707/http://ianridpath.com/startales/durer.html |archive-date= Oct 30, 2023 }}</ref> and portraits in tempera on linen in 1516. His only experiments with ] came in this period, producing five between 1515–1516 and a sixth in 1518; a technique he may have abandoned as unsuited to his aesthetic of methodical, classical form.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Cohen |first1=Brian D |url=http://artinprint.org/article/freedom-and-resistance-in-the-act-of-engraving-or-why-durer-gave-up-on-etching/ |title=Freedom and Resistance in the Act of Engraving (or, Why Dürer Gave up on Etching) |website=Art in Print |series=Vol. 7 No. 3 |date=September–October 2017 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221111185709/https://artinprint.org/article/freedom-and-resistance-in-the-act-of-engraving-or-why-durer-gave-up-on-etching/ |archive-date= Nov 11, 2022 }}</ref> | |||

| == Legacy == | |||

| ], 1518]] | |||

| Dürer exerted a huge influence on the artists of succeeding generations; especially on ], the medium through which his contemporaries mostly experienced his art, as his paintings were mostly in private collections located in only a few cities. His success in spreading his reputation across Europe through prints was undoubtedly an inspiration for major artists such as ], ], and ], who entered into collaborations with ]s to distribute their work beyond their local region. | |||

| ====Patronage of Maximilian I==== | |||

| His work in ] seems to have had an intimidating effect upon his German successors, the ''Little Masters'', who attempted a few large engravings, but continued Dürer's themes in tiny, rather cramped, compositions. The early ] was the only Northern European ] to successfully continue to produce large engravings in the first third of the century. The generation of Italian engravers who trained in the shadow of Dürer all either directly copied parts of his landscape backgrounds (] and Christofano Robetta), or whole prints (] and Agostino Veneziano). However, Dürer's influence became less dominant after 1515, when Marcantonio perfected his new engraving style, which in turn, traveled over the Alps to dominate Northern engraving also. | |||

| ], Vienna (Inv. GG 825)]] | |||

| ] | |||

| From 1512, ] became Dürer's major patron. He commissioned '']'', a vast work printed from 192 separate blocks, the symbolism of which is partly informed by Pirckheimer's translation of ]'s ''Hieroglyphica''. The design program and explanations were devised by ], the architectural design by the master builder and court-painter Jörg Kölderer and the woodcutting itself by ], with Dürer as designer-in-chief. ''The Arch'' was followed by '']'' completed c. 1512. | |||

| In painting, Dürer had relatively little influence in Italy, where probably, only his altarpiece in Venice was to be seen, and his German successors were less effective in blending German and Italian styles. | |||

| Dürer worked with pen on the marginal images for an edition of the Emperor's printed prayer book; these were quite unknown until facsimiles were published in 1808 as part of the first book published in ]. Dürer's work on the book was halted for an unknown reason, and the decoration was continued by artists including ] and ]. Dürer also made several portraits of the Emperor, including one shortly before Maximilian's death in 1519. | |||

| His intense and self-dramatising self-portraits have continued to have a strong influence up to the present, and may be blamed for some of the wilder excesses of artist's self-portraiture, especially in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. | |||

| He has never fallen from critical favour, and there have been revivals of interest in his works Germany in the ''Dürer Renaissance'' of c.1570–1630, in the early nineteenth century, and in ] from 1870–1945.<ref name="Bartrum"/> | |||

| Maximilian was a very cash-strapped prince who sometimes failed to pay, yet turned out to be Dürer's most important patron.<ref>{{cite book |last1=McCorquodale |first1=Charles |title=The Renaissance: European Painting, 1400–1600 |date=1994 |publisher=Studio Editions |isbn=978-1-85891-892-1 |page=261 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=h8JJAQAAIAAJ |access-date=3 December 2021 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Cust |first1=Lionel |title=The Engravings of Albrecht Dürer |date=1905 |publisher=Seeley and Company, limited |page=66 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RSg_AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA66 |access-date=3 December 2021 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Brion |first1=Marcel |title=Dürer: His Life and Work |date=1960 |publisher=Tudor Publishing Company |page=233 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nhANAQAAIAAJ |access-date=3 December 2021 |language=en}}</ref> In his court, artists and learned men were respected, which was not common at that time (later, Dürer commented that in Germany, as a non-noble, he was treated as a parasite).<ref>{{cite book |last1=Innes |first1=Mary |last2=Kay |first2=Charles De |title=Schools of Painting |date=1911 |publisher=G. P. Putnam's sons |page=214 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OqQaAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA214 |access-date=3 December 2021 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |last1=Schäfer |first1=Sandra |title=Erfolgreiche Medienarbeit für die Nachwelt |url=https://kulturfuechsin.com/at/albrecht-duerer-kaiser-maximilian-i-im-khm/ |website=Kulturfüchsin |access-date=3 December 2021 |language=de-DE |date=27 March 2019}}</ref> Pirckheimer (who he met in 1495, before entering the service of Maximilian) was also an important personage in the court and great cultural patron, who had a strong influence on Dürer as his tutor in classical knowledge and humanistic critical methodology, as well as collaborator.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Streissguth |first1=Tom |title=The Renaissance |year= 2007 |publisher=Greenhaven Publishing LLC |isbn=978-0-7377-3216-0 |page=254 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZIJmDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA254 |access-date=4 December 2021 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Smith |first1=Jeffrey Chipps |title=Nuremberg, a Renaissance City, 1500–1618 |year= 2014 |publisher=University of Texas Press |isbn=978-1-4773-0638-3 |page=120 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=AiYKBgAAQBAJ&pg=PT120 |access-date=4 December 2021}}</ref> In Maximilian's court, Dürer also collaborated with a great number of other brilliant artists and scholars of the time who became his friends, like ], ], ], and Hans Tscherte (an imperial architect).<ref>{{cite book |last1=Co |first1=E. P. Goldschmidt & |title=Rare and Valuable Books ... |date=1925 |publisher=E.P. Goldschmidt & Company, Limited |page=125 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xbQ9AAAAIAAJ |access-date=4 December 2021 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Merback |first1=Mitchell B. |title=Perfection's Therapy: An Essay on Albrecht Dürer's Melencolia I |date=2017 |publisher=MIT Press |isbn=978-1-942130-00-0 |pages=155, 258 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-e1LDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA258 |access-date=4 December 2021}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Conway |first1=Sir William Martin |last2=Conway |first2=William Martin Sir |last3=Dürer |first3=Albrecht |title=Literary Remains of Albrecht Dürer |date=1889 |publisher=University Press |pages=26–30 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=LotPAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA12 |access-date=4 December 2021}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Allen |first1=L. Jessie |title=Albrecht Dürer |date=1903 |publisher=Methuen |page=180 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Ll2H8mF0jrcC&pg=PA180 |access-date=4 December 2021}}</ref> | |||

| He is commemorated on the ] of the ] with other artists on April 6. | |||

| Dürer was proud of his ability.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Bongard |first1=Willi |last2=Mende |first2=Matthias |title=Dürer Today |date=1971 |publisher=Inter Nationes |page=25 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=V4pGAQAAIAAJ |access-date=3 December 2021}}</ref> When the emperor tried to sketch Dürer an idea on charcoa, Dürer took the material from Maximilian's hand, finished the drawing and told him: "This is my scepter."<ref>{{cite book |last1=Headlam |first1=Cecil |title=The Story of Nuremberg |date=1900 |publisher=J. M. Dent & Company |page=73 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dzNLAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA73 |access-date=4 December 2021}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Seton-Watson |first1=Robert William |title=Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor: Stanhope Historical Essay 1901 |date=1902 |publisher=Constable |page=96 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tNHDXFR6M-cC&pg=PA96 |access-date=4 December 2021}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Bledsoe |first1=Albert Taylor |last2=Herrick |first2=Sophia M'Ilvaine Bledsoe |title=The Southern Review |date=1965 |publisher=AMS Press |page=114 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8_5IAQAAMAAJ |access-date=4 December 2021}}</ref> On another occasion, Maximilian noticed that the ladder Dürer used was too short and unstable, thus told a noble to hold it for him. The noble refused, saying that it was beneath him to serve a non-noble. Maximilian then came to hold the ladder himself, and told the noble that he could make a noble out of a peasant any day, but he could not make an artist like Dürer out of a noble.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Nüchter |first1=Friedrich |title=Albrecht Dürer, His Life and a Selection of His Works: With Explanatory Comments by Dr. Friedrich Nüchter |date=1911 |publisher=Macmillan and Company, limited |page=22 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ROvVAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA22 |access-date=4 December 2021}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Carl |first1=Klaus |title=Dürer |year= 2013 |publisher=Parkstone International |isbn=978-1-78160-625-4 |page=36 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DSn3AAAAQBAJ&pg=PT36 |access-date=4 December 2021}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Landfester |first1=Manfred |last2=Cancik |first2=Hubert |last3=Schneider |first3=Helmuth |last4=Gentry |first4=Francis G. |title=Brill's New Pauly: Encyclopaedia of the Ancient World. Classical tradition |date=2006 |publisher=Brill |isbn=978-90-04-14221-3 |page=305 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DebXAAAAMAAJ |access-date=4 December 2021}}</ref> | |||

| ])]] | |||

| This story and a 1849 painting depicting it by {{ill|August Siegert|de}} have become relevant recently. This nineteenth-century painting shows Dürer painting a mural at ]. Apparently, this reflects a seventeenth-century "artists' legend" about the previously mentioned encounter (in which the emperor held the ladder) – that this encounter corresponds with the period Dürer was working on the Viennese murals. In 2020, during restoration work, art connoisseurs discovered a piece of handwriting now attributed to Dürer, suggesting that the Nuremberg master had actually participated in creating the murals at St. Stephen's Cathedral. In the recent 2022 Dürer exhibition in Nuremberg (in which the drawing technique is also traced and connected to Dürer's other works), the identity of the commissioner is discussed. Now the painting of Siegert (and the legend associated with it) is used as evidence to suggest that this was Maximilian. Dürer is historically recorded to have entered the emperor's service in 1511, and the mural's date is calculated to be around 1505, but it is possible they have known and worked with each other earlier than 1511.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Cascone |first1=Sarah |title=Astounded Scholars Just Found What Appears to Be a Previously Unknown Work by Albrecht Dürer in a Church's Gift Shop |url=https://news.artnet.com/art-world/durer-discovery-vienna-souvenir-shop-1750233 |access-date=17 July 2022 |work=Artnet News |date=10 January 2020}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=AlbrECHT DÜRER? (2022) |url=http://museen.de/albr-echt-duerer-nuernberg.html |website=museen.de |access-date=17 July 2022}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=Albrecht Dürer gibt weiter Rätsel auf |url=https://www.mittelbayerische.de/region/nuernberg-nachrichten/albrecht-duerer-gibt-weiter-raetsel-auf-21503-art2138796.html |access-date=17 July 2022 |work=Mittelbayerische Zeitung |language=de}}</ref> | |||

| ====Cartographic and astronomical works==== | |||

| Dürer's exploration of space led to a relationship and cooperation with the court astronomer ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Crane |first1=Nicholas |title=Mercator: The Man who Mapped the Planet |year= 2010 |publisher=Orion |isbn=978-0-297-86539-1 |page=74 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RDhQIP5syucC&pg=PT74 |access-date=7 November 2021}}</ref> Stabius also often acted as Dürer's and Maximilian's go-between for their financial problems.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Conway |first1=Sir William Martin |last2=Conway |first2=William Martin Sir |last3=Dürer |first3=Albrecht |title=Literary Remains of Albrecht Dürer |date=1889 |publisher=University Press |page=27 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=LotPAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA27 |access-date=7 November 2021}}</ref> | |||

| In 1515 Dürer and Stabius created the first world map projected on a solid geometric sphere.{{sfn|Crane|2010|p=74}} Also in 1515, Stabius, Dürer and the astronomer {{interlanguage link|Konrad Heinfogel|de}} produced the first planispheres of both southern and northerns hemispheres, as well as the first printed celestial maps, which prompted the revival of interest in the field of ] throughout Europe.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Noflatscher |first1=Heinz |title=Maximilian I. (1459–1519): Wahrnehmung – Übersetzungen – Gender |date=2011 |publisher=StudienVerlag |isbn=978-3-7065-4951-6 |page=245 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PqT5V2mq4SIC |access-date=7 November 2021 |language=de}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Lachièze-Rey |first1=Marc |last2=Luminet |first2=Jean-Pierre |last3=France |first3=Bibliothèque nationale de |title=Celestial Treasury: From the Music of the Spheres to the Conquest of Space |year=2001 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-80040-2 |page=86 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0ZFXiNn62ZEC&pg=PA86 |access-date=7 November 2021}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Nothaft |first1=C. Philipp E. |title=Scandalous Error: Calendar Reform and Calendrical Astronomy in Medieval Europe |year= 2018 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-252018-0 |page=278 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dz5MDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA278 |access-date=7 November 2021}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Sauter |first1=Michael J. |title=The Spatial Reformation: Euclid Between Man, Cosmos, and God |year= 2018 |publisher=University of Pennsylvania Press |isbn=978-0-8122-9555-9 |page=98 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1Qd7DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA98 |access-date=7 November 2021}}</ref> | |||

| ===Journey to the Netherlands (1520–1521)=== | |||

| ]'' (1521), oil on oakwood, 59. × 48.5 cm, ], Lisbon. Dürer's most important painting created during his fourth and last major journey.]] | |||

| Maximilian's death came at a time when Dürer was concerned he was losing "my sight and freedom of hand" (perhaps caused by arthritis) and increasingly affected by the writings of ].<ref>Bartrum, 204. Quotation from a letter to the secretary of the Elector of Saxony.</ref> In July 1520 Dürer made his fourth and last major journey, to renew the Imperial pension Maximilian had given him and to secure the patronage of the new emperor, ], who was to be crowned at ]. Dürer journeyed with his wife and her maid via the ] to ] and then to ], where he was well received and produced numerous drawings in silverpoint, chalk and charcoal. In addition to attending the coronation, he visited Cologne (where he admired the painting of ]), ], ], ] (where he saw ]'s '']''), ] (where he admired ]'s '']''),<ref>Borchert (2011), 101.</ref> and ]. | |||

| Dürer took a large stock of prints with him and wrote in his diary to whom he gave, exchanged or sold them, and for how much. This provides rare information of the monetary value placed on prints at this time. Unlike paintings, their sale was very rarely documented.<ref>Landau & Parshall: 350–354 and ''passim''.</ref> While providing valuable documentary evidence, Dürer's Netherlandish diary also reveals that the trip was not a profitable one. For example, Dürer offered his last portrait of Maximilian to his daughter, ], but eventually traded the picture for some white cloth after Margaret disliked the portrait and declined to accept it. During this trip he also met ], ], ], ], ] and ], though he did not, it seems, meet ].<ref>Panofsky (1945), 209.</ref> | |||

| Having secured his pension, Dürer returned home in July 1521, having caught an undetermined illness, which afflicted him for the rest of his life, and greatly reduced his rate of work.<ref name="Bartrum"/> | |||

| ===Final years, Nuremberg (1521–1528)=== | |||

| ], New York]] | |||

| On his return to Nuremberg, Dürer worked on a number of grand projects with religious themes, including a crucifixion scene and a {{Lang|it|]}}, though neither was completed.<ref>Panofsky (1945), 223.</ref> This may have been due in part to his declining health, but perhaps also because of the time he gave to the preparation of his theoretical works on geometry and perspective, the proportions of men and horses, and ]. | |||

| However, one consequence of this shift in emphasis was that during the last years of his life, Dürer produced comparatively little as an artist. In painting, there was only a portrait of ], a ], ], and two panels showing ] and ] beside him. This last great work, '']'', was given by Dürer to the City of Nuremberg—although he was given 100 guilders in return.<ref name="Panofsky"/> | |||

| As for engravings, Dürer's work was restricted to portraits and illustrations for his treatise. The portraits include his boyhood friend ], Cardinal-Elector ]; ], elector of Saxony; ], and ]. For those of ], Melanchthon, and Dürer's final major work, a drawn portrait of the Nuremberg patrician Ulrich Starck, Dürer depicted the sitters in profile. | |||

| Despite complaining of his lack of a formal classical education, Dürer was greatly interested in intellectual matters and learned much from Willibald Pirckheimer, whom he no doubt consulted on the content of many of his images.<ref>] (2010), "Albrecht Dürer between Agnes Frey and Willibald Pirckheimer", ''The Essential Dürer'', ed. Larry Silver and ], Philadelphia, 85–205.</ref> He also derived great satisfaction from his friendships and correspondence with Erasmus and other scholars. Dürer succeeded in producing two books during his lifetime. ''The Four Books on Measurement'' were published at Nuremberg in 1525 and was the first book for adults on ] in German,<ref name="Bartrum"/> as well as being cited later by ] and ]. The other, a work on city fortifications, was published in 1527. ''The Four Books on Human Proportion'' were published posthumously, shortly after his death in 1528.<ref name=Mueller /> | |||

| Dürer died in Nuremberg at the age of 56, leaving an estate valued at 6,874 florins – a considerable sum. He is buried in the Johannisfriedhof cemetery. ] (purchased in 1509 from the heirs of the astronomer ]), where his workshop was located and where his widow lived until her death in 1539, remains a prominent Nuremberg landmark.<ref name="Bartrum"/> | |||

| ] in ]]] | |||

| ====Dürer and the Reformation==== | |||

| Dürer's writings suggest that he may have been sympathetic to Luther's ideas, though it is unclear if he ever left the Catholic Church. Dürer wrote of his desire to draw Luther in his diary in 1520: "And God help me that I may go to Dr. Martin Luther; thus I intend to make a portrait of him with great care and engrave him on a copper plate to create a lasting memorial of the Christian man who helped me overcome so many difficulties."<ref>Price (2003), 225.</ref> In a letter to ] in 1524, Dürer wrote, "because of our Christian faith we have to stand in scorn and danger, for we are reviled and called heretics". Most tellingly, Pirckheimer wrote in a letter to Johann Tscherte in 1530: "I confess that in the beginning I believed in Luther, like our Albert of blessed memory ... but as anyone can see, the situation has become worse." Dürer may even have contributed to the Nuremberg City Council's mandating Lutheran sermons and services in March 1525. Notably, Dürer had contacts with various reformers, such as ], ], Melanchthon, Erasmus and ] from whom Dürer received Luther's '']'' in 1520.<ref>Price (2003), 225–248.</ref> Yet Erasmus and C. Grapheus are better said to be Catholic change agents. Also, from 1525, "the year that saw the peak and collapse of the ], the artist can be seen to distance himself somewhat from the movement..."<ref>Wolf (2010), 74.</ref> | |||

| Dürer's later works have also been claimed to show ] sympathies. His 1523 '']'' woodcut has often been understood to have an ] theme, focusing as it does on Christ espousing the ], as well as the inclusion of the ]ic cup, an expression of Protestant ],<ref>Strauss, 1981.</ref> although this interpretation has been questioned.<ref>Price (2003), 254.</ref> The delaying of the engraving of ], completed in 1523 but not distributed until 1526, may have been due to Dürer's uneasiness with images of saints; even if Dürer was not an ], in his last years he evaluated and questioned the role of art in religion.<ref>Harbison (1976).</ref> | |||

| ==Theoretical works== | |||

| In all his theoretical works, in order to communicate his theories in the ] rather than in ], Dürer used graphic expressions based on a ], craftsmen's language. For example, {{Lang|de|Schneckenlinie}} ("snail-line") was his term for a spiral form. Thus, Dürer contributed to the expansion in German prose which Luther had begun with his translation of the ].<ref name="Panofsky">Panofsky (1945).</ref> | |||

| ===''Four Books on Measurement''=== | |||

| {{more citations needed|section|date=May 2017}} | |||

| Dürer's work on ] is called the ''Four Books on Measurement'' (''Underweysung der Messung mit dem Zirckel und Richtscheyt'' or ''Instructions for Measuring with ] and Ruler'').<ref>A. Koyre, "The Exact Sciences", in ''The Beginnings of Modern Science'', edited by Rene Taton, translated by A. J. Pomerans.</ref> The first book focuses on linear geometry. Dürer's geometric constructions include ], ] and ]s. He also draws on ], and ]'s {{Lang|la|Libellus super viginti duobus elementis conicis}} of 1522. | |||

| The second book moves onto two-dimensional geometry, i.e. the construction of regular ]s.<ref>Panofsky (1945), 255.</ref> Here Dürer favours the methods of ] over ]. The third book applies these principles of geometry to architecture, engineering and ]. In architecture Dürer cites ] but elaborates his own classical designs and ]. In typography, Dürer depicts the geometric construction of the ], relying on ]. However, his construction of the ] is based upon an entirely different ] system. The fourth book completes the progression of the first and second by moving to three-dimensional forms and the construction of ]. Here Dürer discusses the five ]s, as well as seven ] semi-regular solids, as well as several of his own invention. | |||

| ===''Four Books on Human Proportion''=== | |||

| ] | |||

| Dürer's work on ] is called the ''Four Books on Human Proportion'' (''Vier Bücher von menschlicher Proportion'') of 1528.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://archive.org/details/hierinnsindbegri00dure|title=Hierinn sind begriffen vier Bucher von menschlicher Proportion durch Albrechten Durer von Nurerberg|last=Durer|first=Albrecht|date=1528|publisher=Hieronymus Andreae Formschneider|access-date=6 August 2018}}</ref> The first book was mainly composed by 1512/13 and completed by 1523, showing five differently constructed types of both male and female figures, all parts of the body expressed in fractions of the total height. Dürer based these constructions on both ] and empirical observations of "two to three hundred living persons",<ref name="Panofsky"/> in his own words. The second book includes eight further types, broken down not into fractions but an ] system, which Dürer probably learned from ]'s {{Lang|la|De harmonica mundi totius}} of 1525. In the third book, Dürer gives principles by which the proportions of the figures can be modified, including the mathematical simulation of ] and ]s; here Dürer also deals with human ]. The fourth book is devoted to the theory of movement.<ref name="se">Schaar, Eckhard. "A Newly Discovered Proportional Study by Dürer in Hamburg". ''Master Drawings'', vol. 36, no. 1, 1998. pp. 59–66. {{JSTOR|1554333}}</ref> | |||

| Appended to the last book, however, is a self-contained essay on aesthetics, which Dürer worked on between 1512 and 1528, and it is here that we learn of his theories concerning 'ideal beauty'. Dürer rejected Alberti's concept of an objective beauty, proposing a relativist notion of beauty based on variety. Nonetheless, Dürer still believed that truth was hidden within nature, and that there were rules which ordered beauty, even though he found it difficult to define the criteria for such a code. In 1512/13 his three criteria were function ("Nutz"), naïve approval ("Wohlgefallen") and the happy medium ("Mittelmass"). However, unlike Alberti and ], Dürer was most troubled by understanding not just the abstract notions of beauty but also as to how an artist can create beautiful images. Between 1512 and the final draft in 1528, Dürer's belief developed from an understanding of human creativity as spontaneous or ] to a concept of 'selective inward synthesis'.<ref name="Panofsky"/> In other words, that an artist builds on a wealth of visual experiences in order to imagine beautiful things. Dürer's belief in the abilities of a single artist over inspiration prompted him to assert that "one man may sketch something with his pen on half a sheet of paper in one day, or may cut it into a tiny piece of wood with his little iron, and it turns out to be better and more artistic than another's work at which its author labours with the utmost diligence for a whole year".<ref>Panofsky (1945), 283.</ref> | |||

| <gallery widths="140px" heights="140px"> | |||

| File:AlbrechtDürer01.jpg|Title page of ''Vier Bücher von menschlicher Proportion'' showing the ] signature of artist | |||

| File:Durer foot.jpg|Dürer often used ]s. | |||

| File:Durer face transforms.jpg|Dürer's study of human proportions | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ===''Book on Fortification''=== | |||

| In 1527, Dürer also published ''Various Lessons on the Fortification of Cities, Castles, and Localities'' (''Etliche Underricht zu Befestigung der Stett, Schloss und Flecken''). It was printed in ], probably by Hieronymus Andreae and reprinted in 1603 by Johan Janssenn in ]. In 1535 it was also translated into Latin as ''On Cities, Forts, and Castles, Designed and Strengthened by Several Manners: Presented for the Most Necessary Accommodation of War'' (''De vrbibus, arcibus, castellisque condendis, ac muniendis rationes aliquot : praesenti bellorum necessitati accommodatissimae''), published by Christian Wechel (Wecheli/Wechelus) in Paris.<ref>For a French translation, see , trans A. Rathau (Paris 1870).</ref> | |||

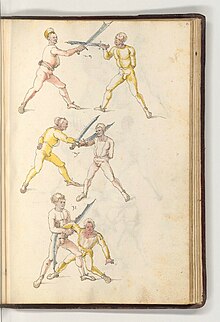

| ===Fencing=== | |||

| ] | |||

| Dürer created many sketches and woodcuts of soldiers and knights over the course of his life. His most significant martial works, however, were made in 1512 as part of his efforts to secure the patronage of Maximilian I. Using existing manuscripts from the ''Nuremberg Group'' as his reference, his workshop produced the extensive ''Οπλοδιδασκαλια sive Armorvm Tractandorvm Meditatio Alberti Dvreri'' ("Weapon Training, or Albrecht Dürer's Meditation on the Handling of Weapons", MS 26-232). Another manuscript based on the Nuremberg texts as well as one of Hans Talhoffer's works, the untitled ''Berlin Picture Book'' (Libr.Pict.A.83), is also thought to have originated in his workshop around this time. These sketches and watercolours show the same careful attention to detail and human proportion as Dürer's other work, and his illustrations of grappling, long sword, dagger, and ] are among the highest-quality in any fencing manual.<ref>{{cite book|last=Haegedorn |first=Dierk |date=2021 |title=Albrecht Dürer – Das Fechtbuch |publisher= VST Verlag |isbn=978-3-932077-50-0}}</ref> | |||

| ==Legacy and influence== | |||

| Dürer exerted a huge influence on the artists of succeeding generations, especially in printmaking, the medium through which his contemporaries mostly experienced his art, as his paintings were predominantly in private collections located in only a few cities. His success in spreading his reputation across Europe through prints was undoubtedly an inspiration for major artists such as Raphael, ], and ], all of whom collaborated with printmakers to promote and distribute their work. | |||

| His engravings seem to have had an intimidating effect upon his German successors; the "]" who attempted few large engravings but continued Dürer's themes in small, rather cramped compositions. ] was the only Northern European engraver to successfully continue to produce large engravings in the first third of the 16th century. The generation of Italian engravers who trained in the shadow of Dürer all either directly copied parts of his landscape backgrounds (], ], ] and ]), or whole prints (] and ]). However, Dürer's influence became less dominant after 1515, when Marcantonio perfected his new engraving style, which in turn travelled over the Alps to also dominate Northern engraving. | |||

| Dürer had relatively little influence in Italy, where probably only his altarpiece in Venice was seen, and his German successors were less effective in blending German and Italian styles. His intense and self-dramatizing self-portraits have continued to have a strong influence up to the present, especially on painters in the 19th and 20th century who desired a more dramatic portrait style. Dürer has never fallen from critical favour, and there have been significant revivals of interest in his works in Germany in the ''Dürer Renaissance'' of about 1570 to 1630, in the early nineteenth century, and in German ] from 1870 to 1945.<ref name="Bartrum"/> | |||

| The ] commemorates Dürer annually on 6 April,<ref>''Lutheranism 101'' edited by Scot A. Kinnaman, CPH, 2010.</ref> along with ],<ref>{{cite web| url = https://download.elca.org/ELCA%20Resource%20Repository/What_is_a_Commemoration_and_How_do_we_celebrate_them.pdf| title = 'What is a Commemoration...', ELCA}}</ref> ] and ]. | |||

| In 1993, two of Dürer's drawings – ''Women's Bathhouse'', valued at about $10 million, and ''Sitting Mary With Child'' – along with other works of art were ] from the ]. The drawings were later recovered.<ref>{{cite web | url =https://www.nytimes.com/2001/07/19/arts/twice-stolen-twice-found-a-case-of-art-on-the-lam.html|title=Twice Stolen, Twice Found: A Case of Art On the Lam|work=]|author=Ralph Blumenthal| date=19 July 2001| accessdate =5 November 2020}}</ref> | |||

| ==Gallery== | |||

| <gallery widths="116" heights="150" caption="Religious paintings"> | |||

| File:Albrecht Dürer 012.jpg|''St Jerome in the Wilderness'', {{circa|1496}}, oil on pearwood, 23.1 × 17.4 cm, ], London (NG6563) | |||

| File:Albrecht Dürer - Jesus among the Doctors - Google Art Project.jpg|'']'', 1506, oil on poplar, 64.3 × 80.3 cm, ], Madrid (134 (1934.38) | |||

| File:Dürer, Albrecht - Marter der zehntausend Christen - KHM.jpg|'']'', 1508, oil from wood transferred to canvas, 99 × 87 cm, ], Wien (GG 835) | |||

| Albrecht Dürer, , Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Gemäldegalerie - Allerheiligenbild ("Landauer Altar") - GG 838 - Kunsthistorisches Museum.jpg|''] (Landauer Altar)'', 1511, oil on poplar, 135 × 123.4 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum (GG 838). The framework is a reconstruction of his design. | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| <gallery widths="116" heights="155" caption="Portraits"> | |||

| File:1490 Duerer Bildnis von Barbara Duerer geb. Holper anagoria.JPG|], 1490, oil on fir wood, 47.2 × 35.7 cm, ] Nuremberg (Gm 1160) | |||

| File:Albrecht Dürer - Ritratto del padre - Google Art Project.jpg|'']'', 1490, oil on panel, 47.5 × 39.5 cm, ], Florence | |||

| File:Albrecht Dürer - Portrait of Oswolt Krel - WGA6934.jpg|''Portrait of Oswolt Krel'', 1499, oil on limewood, 49.6 × 39 cm, ], München. Krel was a merchant from ]. | |||

| File:Albrecht Dürer - Bildnis einer jungen Venezianerin - Google Art Project.jpg|''Portrait of a Young Venetian Woman,'' 1506, oil on poplar, 28.5 × 21.5 cm, ], Berlin (557G). The abstract background suggests the sea. | |||

| File:Albrecht Dürer - Portrait of Bernhard von Reesen - Google Art Project.jpg|''Portrait of ]'', 1521, 45.5 × 31.5 cm, ], Dresden (1871) | |||

| File:Dürer - Hieronymus Holzschuher (1469-1529) mit Deckel, 1526, 557E.jpg |'']'', 1526, oil and paint on limewood, 51 × 37 cm, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin (557E) | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| <gallery widths="116" heights="140" caption="Watercolours"> | |||

| File:Innsbruck castle courtyard.jpg|''Innsbruck Castle Courtyard'', {{circa|1495}}, watercolour and ], 36.8 × 26.9 cm, ] (3057) | |||

| File:Vue du val d'Arco dans le Tyrol méridional - Musée du Louvre Arts graphiques INV 18579, Recto.jpg|''View of the Arco Valley'' in ], 1495, watercolour with highlights, 22.3 × 22.2 cm, ], Paris | |||

| File:Albrecht Dürer - Der Weiher im Walde (ca. 1497).jpg|''Landscape with a Woodland Pool,'' {{circa|1497}}, watercolour and gouache, 26.2 × 35.6 cm, ], London | |||

| File:Albrecht Dürer - Der Flügel einer Blauracke (ca. 1500).jpg|''],'' {{circa|1500}} ("1512" by later hand), watercolour and gouache on parchment, 19.6 × 20 cm, Albertina (4840) | |||

| File:Albrecht Dürer - Mary among a Multitude of Animals, c. 1503 - Google Art Project.jpg|''Mary among a Multitude of Animals'', {{circa|1506}}, dark brown ink and watercolour, 31,9 × 24,1 cm, Albertina (3066) | |||

| File:Albrecht Dürer, Tuft of Cowslips, 1526, NGA 74162.jpg|''Tuft of Cowslips'', 1526, gouache on ], 19.3 × 16.8 cm, National Gallery of Art | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| <gallery widths="116" heights="155" caption="Drawings"> | |||

| File:Dürer - Académie de femme debout, de dos, la main sur une hampe d'où part un voile, INV 19058, Recto.jpg|''Study of a Female Nude from Behind'', 1495, brush and pen on paper, 31.6 × 21.2 cm, ], Paris (INV 19058 R) | |||

| File:Dürer - Liegender weiblicher Akt, 1501.png|''Reclining Nude'', 1501, brush and pen(?) w/ highlights and construction lines, 16.9 × 21.8 cm, Albertina (3072) | |||

| File:Dürer - Trois têtes d'enfants, btv1b100248711.jpeg|''Three Children's Heads'', 1506, pen and ink on blue paper with highlights in gouache, 21,8 × 37,9 cm, ], Paris | |||

| File:Albrecht Dürer - Selbstbildnis als Akt. (Weimar).jpg|''Self-Portrait in the Nude'', {{circa|1509}}, pen and brush, black ink with white lead on green prepared paper, 29 × 15 cm, ] (KK106) | |||

| File:Albrecht Dürer - Barbara Dürer, die Mutter des Künstlers (1514).jpg|''Portrait of the Artist's Mother at the Age of 63'', spring 1514, charcoal on paper, 42.2 × 30.6 cm, ] (KdZ 22) | |||

| File:Albrecht Dürer - Head of an Old Man, 1521 - Google Art Project.jpg|''Head of an 93-Year-Old Man'', 1521, brush, ink, heightened w/ gouache, on gray-violet prepared paper, 41.5 × 28.2 cm, Albertina (3167). Study for the St. Jerome | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| <gallery widths="116" heights="174" caption="Copper engravings and an etching"> | |||

| File:Albrecht Dürer Druckplatte Christus am Ölberg.jpg|''Christ on the Mount of Olives'', 1515, the only surviving printing plate, iron, 22.7 × 16.1 cm, ] | |||

| File:Albrecht Dürer, Nemesis (The Great Fortune), c. 1501-1502, NGA 6603.jpg|''Nemesis (The Great Fortune)'', {{circa|1501}}/02, 33.5 × 23.3 cm (National Gallery of Art) | |||

| File:Saint Christopher Facing Left MET DP815920.jpg|''St. Christopher'', 1521, 11.6 × 7.4 cm (Metropolitan Museum of Art) | |||

| File:Willibald Pirckheimer MET DP815931.jpg|''Portrait of Willibald Pirckheimer'', 1524, 19 × 12.4 cm (Metropolitan Museum of Art) | |||

| File:Landscape with a Large Cannon MET MM7867.jpg|''The Cannon'', 1518, etching, 21.7 × 32 cm (Metropolitan Museum of Art) | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| <gallery widths="116" heights="155" caption="Woodcut prints"> | |||

| File:The Martyrdom of Saint Catherine MET MM30203.jpg|''The Martyrdom of Saint Catherine'', {{circa|1498}}, carved pearwood block, 39.4 × 28.3 × 2.6 cm, ], New York | |||

| File:Albrecht Dürer, The Flagellation, c. 1497, NGA 6736.jpg|''The Flagellation'', from the '']'', {{circa|1497}}, 39 × 28 cm, (printed {{circa|1498–1500}}, ]) | |||

| File:Albrecht Dürer, The Four Horsemen, 1498, NGA 142352.jpg|''Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse'', 1498, 39.5 × 28.5 cm (NGA, 142352) | |||

| File:Albrecht Dürer - The Expulsion from Paradise (NGA 1943.3.3634).jpg|''The Expulsion from Paradise'' from the ''Small Passion'', 1510, 12.5 × 9.8 cm (NGA) | |||

| File:Coat of Arms of Albrecht Dürer MET DP816462.jpg|], which features a door as a pun on his name, and the winged bust of a ] (1523), 35.1 × 26.1 cm (MET) | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ==List of works== | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| <!-- ---------------------------------------------------------- | |||

| See http://en.wikipedia.org/Wikipedia:Footnotes for a | |||

| discussion of different citation methods and how to generate | |||

| footnotes using the <ref>, </ref> and <reference /> tags | |||

| ----------------------------------------------------------- --> | |||

| <div class="references-small"> | |||

| <references /> | |||

| </div> | |||

| == |

===Notes=== | ||

| {{Reflist|group=n}} | |||

| *Giulia Bartrum, Albrecht Dürer and his Legacy, British Museum Press, 2002, ISBN 0714126330 | |||

| *Walter L. Strauss (Editor), The Complete Engravings, Etchings and Drypoints of Albrecht Durer, | |||

| Dover Publications, 1973 ISBN 0486228517 — still in print in paperback | |||

| *Wilhelm Kurth (Editor), The Complete Woodcuts of Albrecht Durer, Dover Publications, 2000, ISBN 0486210979 — still in print in paperback | |||

| == |

===Citations=== | ||

| {{Reflist|colwidth=30em}} | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * http://www.ibiblio.org/wm/paint/auth/durer/ | |||

| * | |||

| * at Museumsportal Schleswig-Holstein | |||

| * . Selected pages scanned from the original work. Historical Anatomies on the Web. US National Library of Medicine. | |||

| * {{gutenberg author | id=Albrecht+Dürer | name=Albrecht Dürer}} | |||

| * {{MacTutor Biography | id=Durer}} | |||