| Revision as of 01:57, 6 March 2007 view sourceLaMenta3 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers4,548 edits Revert to revision 112961311 dated 2007-03-06 01:56:02 by 60.234.160.169 using popups← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 10:11, 28 November 2024 view source JBW (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators196,114 edits If it had been refuted it would no longer be disputed. | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Fretted string instrument}} | |||

| {{Merge|Parts of the guitar|date=February 2007}} | |||

| {{Other uses}} | |||

| {{Unreferenced|date=July 2006}} | |||

| {{ |

{{pp-semi-indef}} | ||

| {{Pp-move-indef}} | |||

| {{Infobox Instrument | |||

| {{Infobox instrument | |||

| |name=Guitar | |||

| | name = Guitar | |||

| |names= | |||

| | names = | |||

| |image=Bass-und-primgitarre.jpg | |||

| | image = GuitareClassique5.png | |||

| |classification=] (], nylon stringed guitars usually played with fingerpicking, and steel-, etc. usually with a ].) | |||

| | image_capt = A ] with nylon ] | |||

| |range= ]<div align=center>(a regularly tuned guitar)</div> | |||

| | background = string | |||

| |related=*] and ] string instruments | |||

| | classification = ] (] or ]med) | |||

| |articles= | |||

| | hornbostel_sachs = 321.322 | |||

| | hornbostel_sachs_desc = Composite ] | |||

| | developed = 13th century | |||

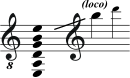

| | range = ]<div class="center">(a standard tuned guitar)</div> | |||

| | related = *] and ] string instruments | |||

| | articles = | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| The '''guitar''' is a ] that is usually fretted (with ]) and typically has six or ]. It is usually held flat against the player's body and played by ] or ] the strings with the dominant hand, while simultaneously pressing selected strings against ] with the fingers of the opposite hand. A ] may also be used to strike the strings. The sound of the guitar is projected either ], by means of a resonant hollow chamber on the guitar, or ] by an electronic ] and an ]. | |||

| The '''guitar''' is a ] with ancient roots, used in a wide variety of musical styles, and it is also a ]. It is most recognized as the primary instrument in ], ], ], ] and many forms of ]. The guitar usually has six ], but ], ], ], even ] and ] string guitars also exist. Guitars are made and repaired by ]s. Guitars may be played ] or they may rely on an ] that usually allows for electronic manipulation of tone. The ] was introduced in the 20th century, and had a profound influence on ]. | |||

| The guitar is classified as a ], meaning the sound is produced by a vibrating string stretched between two fixed points. Historically, a guitar was constructed from wood, with its strings made of ]. Steel guitar strings were introduced near the end of the nineteenth century in the United States,<ref name="smogyipremier">{{cite web |last1=Somogyi |first1=Ervin |title=Tracking The Steel-String Guitar's Evolution, Pt. 1 |url=https://www.premierguitar.com/articles/Tracking_The_Steel_String_Guitars_Evolution_Pt_1 |website=premierguitar.com |publisher=Premier Guitar Magazine |access-date=February 27, 2021 |date=January 7, 2011}}</ref> but nylon and steel strings became mainstream only following ].<ref name="smogyipremier"/> The guitar's ancestors include the ], the ], the four-] ], and the five-course ], all of which contributed to the development of the modern six-string instrument. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| ], ]. Dated 2000-1500 B.C. Kept at the ].]] | |||

| Instruments similar to the guitar have been popular for at least 5,000 years. The guitar appears to be derived from earlier instruments known in ] as the Sitara. Instruments very similar to the guitar appear in ancient carvings and statues recovered from the old ]ian capitol of ]. The modern word, guitar, was adopted into ] from ] ''guitarra'', derived from earlier ] word ''].'' Prospective sources for various names of musical instruments that ''guitar'' could be derived from appear to be a combination of two ] roots: ''guit-'', similar to Sanskrit ''sangeet'' meaning "''music''", and ''-tar'' a widely attested root meaning "''chord''" or "''string''". | |||

| There are three main types of modern guitar: the ] (Spanish guitar); the ] or ]; and the ] (played across the player's lap). Traditional acoustic guitars include the ] (typically with a large sound hole) or the ], which is sometimes called a "]". The tone of an acoustic guitar is produced by the strings' vibration, amplified by the hollow body of the guitar, which acts as a ]. The classical ] is often played as a ] instrument using a comprehensive ] technique where each string is plucked individually by the player's fingers, as opposed to being strummed. The term "finger-picking" can also refer to a specific tradition of folk, blues, bluegrass, and country guitar playing in the United States. | |||

| ] ] from the ], showing a Guitar-like plucked instrument.]] | |||

| The word ''guitar'' is a ] ] to ] ]. The word ''qitara'' is an ] name for various members of the ] family that preceded the Western guitar. The name ''guitarra'' was introduced into ] when such instruments were brought into ] by the ] after the ]. (). According to merriam-webster (www.m-w.com), the English word derives from French guitare, which in turn comes from Spanish guitarra. The Spanish word was borrowed directly from Arabic qītār which was in turn adapted from Greek kithara. The Greek word may have, according to etymonline.com, its roots in the Persian word ]. | |||

| ]s, first patented in 1937,<ref name="history-channel">{{cite web|title=First-ever electric guitar patent awarded to the Electro String Corporation|url=http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/first-ever-electric-guitar-patent-awarded-to-the-electro-string-corporation|website=history.com|publisher=A&E Television Networks|access-date=September 20, 2017}}</ref> use a ] and ] that made the instrument loud enough to be heard, but also enabled manufacturing guitars with a solid block of wood needing a resonant chamber.<ref name="beauchamp">{{cite web|title=The Earliest Days of the Electric Guitar |url=http://www.rickenbacker.com/history_early.asp |website=rickenbacker.com |publisher=Rickenbacker International |access-date=September 7, 2017}}</ref> A wide array of electronic ]s became possible including ] and ]. ] began to dominate the guitar market during the 1960s and 1970s; they are less prone to unwanted ]. As with acoustic guitars, there are a number of types of electric guitars, including ], ]s (used in ], ] and ]) and ]s, which are widely used in ]. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The Spanish '']'' "de mano" appears to be an aberration in the transition of the renaissance guitar to the modern guitar. It had ]-style ] and a guitar-like body. Its construction had as much in common with the modern guitar as with its contemporary four-course renaissance guitar. The vihuela enjoyed only a short period of popularity, the last surviving publication of music for the instrument appeared in 1576. It is not clear whether it represented a transitional form or was simply a design that combined features of the Arabic oud and the European lute. In favor of the latter view, the reshaping of the vihuela into a guitar-like form can be seen as a strategy of differentiating the European lute visually from the Moorish ]. (See the article on the ''']''' for further history.) The Ancient Iranian lute, called '']'' in ] also is found in the word guitar. The tar is thousands of years old, and could be found in 2, 3, 5, and 6 string variations. | |||

| The loud, amplified sound and sonic power of the electric guitar played through a guitar amp have played a key role in the development of ] and ], both as an ] instrument (playing ]s and ]s) and performing ]s, and in many rock subgenres, notably ] and ]. The electric guitar has had a major influence on ]. The guitar is used in a wide variety of musical genres worldwide. It is recognized as a primary instrument in genres such as ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ], occasionally used as a sample in ], ], or ]. | |||

| The Vinaccia family of luthiers is known for developing the ], and may have built the earliest extant six string guitar. Gaetano Vinaccia (] - after ]) <ref>''The Classical Mandolin'' by Paul Sparks (1995)</ref> has his signature on the label of a guitar built in ] for six strings with the date of ]<ref></ref> <ref>''The Guitar and Its Music: From the Renaissance to the Classical Era'' by James Tyler (2002)</ref>. This guitar has been examined and does not show tell-tale signs of modifications from a double-course guitar. However, fakes are common for guitars and their labels in this era, and caution should be taken. | |||

| {{TOC limit}} | |||

| ==History== | |||

| Modern dimensions of the classical instrument were established by ] (1817-1892), working in Seville in the 1850's. Torres and Louise Panormo of London (active 1820s-1840s) were both responsible for demonstrating the superiority of fan strutting over transverse table bracing.<ref name="Strutting">{{cite book|last=Evans|first=Tom and MaryAnne|year=1977|title=Guitars: Music, history, Construction and Players from the Renaissance to Rock|page=42|id=ISBN 0-448-22240-X}}</ref> | |||

| {{see also|Lute#History and evolution of the lute|History of lute-family instruments|Gittern|Citole#Origins|Classical guitar#History}} | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| | caption_align = center | |||

| | align = right | |||

| | image2 = Hittite lute from Alacahöyük 1399–1301 BC cropped.png | |||

| | width2 = 200 | |||

| | alt2 = Hittite lute | |||

| | caption2 = Turkey. ] lute from ] 1399–1301 BC. This image is sometimes used to indicate the antiquity of the guitar, because of the shape of its body.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.gitarrenzentrum.com/news-2/14112012-for-those-who-are.html|title=14.11.2012 for those who are interested in ancient guitars and archaeology |website=Gitarrenzentrum.com|access-date=18 April 2021|quote= ''Guitar rooted in northern Turkey, not Spain''...Today's Zaman. Stand: 13 November 2012 / TODAY'S ZAMAN, İSTANBUL... http://www.todayszaman.com/news-298052-guitar-rooted-in-northern-turkey-not-spain.html}}</ref> | |||

| | image1 = Guitar-like plucked instrument, Carolingian Psalter, 9th century manuscript, 108r part, Stuttgart Psalter.jpg | |||

| | width1 = 140 | |||

| | alt1 = Hittite lute colorized | |||

| | caption1 = Instrument labeled "]" in the ], a ] ] from 9th century ]. | |||

| | footer = Musical instrument historians write that it is an error to consider "oriental lutes" as direct ancestors of the guitar, simply because they have the same body shape, or because they have a perceived etymological relationship (kithara, guitarra). While examples with guitar-like incurved sides such as the instrument in the ] or the Hittite lute from ] are known, there are no intermediary instruments or traditions between those instruments and the guitar.<ref name=groveguitar>{{cite encyclopedia |author1= Harvey Turnbull |author2= ] |editor-last= Sadie |editor-first=Stanley |title= Guitar|encyclopedia= The New Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments |year=1984 |id= Volume 2 |pages= 87–88|quote= ...the application of the name 'guitar' with its overtones of European musical practice, to oriental lutes betrays a superficial acquaintance with the instruments concerned.}}</ref><br /><br /> | |||

| Similarly, musicologists have argued over whether instruments indigenous to Europe could have led to the guitar. This idea has not gotten beyond speculation and needs "a thorough study of ] and performing practice" by ethnomusicologists.<ref name=groveguitar/> | |||

| }} | |||

| The modern word ''guitar'' and its antecedents have been applied to a wide variety of chordophones since classical times, sometimes causing confusion. The English word ''guitar'', the German ''{{lang|de|Gitarre}}'', and the French ''{{lang|fr|guitare}}'' were all adopted from the Spanish ''{{lang|es|guitarra}}'', which comes from the ] {{lang|xaa|قيثارة}} (''{{transliteration|ar|ALA|qīthārah}}''){{sfn|Farmer 1930|p=137}} and the Latin ''{{lang|la|cithara}}'', which in turn came from the ] {{lang|grc|κιθάρα}} <ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/guitar | title=Definition of GUITAR }}</ref> which is of uncertain ultimate origin. '']'' appears in the Bible four times (1 Cor. 14:7, Rev. 5:8, 14:2, and 15:2), and is usually translated into English as ''harp''. | |||

| The ] was patented by ] in ]. Beauchamp co-founded ] which used the horseshoe-magnet pickup. However, it was ] that first produced electric guitars for the wider public. Danelectro also pioneered ] technology. {{Fact|date=February 2007}} | |||

| The origins of the modern guitar are not known.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/guit/hd_guit.htm|title=The Guitar {{!}} Essay {{!}} Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History {{!}} The Metropolitan Museum of Art|last1=Dobney |first1=Jayson Kerr |first2=Wendy |last2=Powers |website=The Met's Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History|access-date=2017-04-08}}</ref> Before the development of the ] and the use of synthetic materials, a guitar was defined as being an instrument having "a long, fretted neck, flat wooden ], ribs, and a flat back, most often with incurved sides."{{sfn|Kasha 1968|pp=3–12}} The term is used to refer to a number of ]s that were developed and used across Europe, beginning in the 12th century and, later, in the Americas.{{sfn|Wade 2001|p=10}} A 3,300-year-old stone carving of a ] bard playing a stringed instrument is the oldest iconographic representation of a chordophone, and clay plaques from ] show people playing a lute-like instrument which is similar to the guitar. | |||

| Several scholars cite varying influences as antecedents to the modern guitar. Although the development of the earliest "guitar" is lost to the history of medieval Spain, two instruments are commonly claimed as influential predecessors: the four-string ] and its precursor, the European ]; the former was brought to Iberia by the ] in the 8th century. It has often been assumed that the guitar is a development of the lute, or of the ancient Greek kithara. However, many scholars consider the lute an offshoot or separate line of development which did not influence the evolution of the guitar in any significant way.{{sfn|Kasha 1968|pp=3–12}}{{sfn|Summerfield 2003}}<ref></ref> | |||

| At least two instruments called "guitars" were in use in Spain by 1200: the ''{{lang|la|]}}'' (Latin guitar) and the so-called ''{{lang|la|]}}'' (Moorish guitar). The guitarra morisca had a rounded back, a wide fingerboard, and several sound holes. The guitarra Latina had a single sound hole and a narrower neck. By the 14th century the qualifiers "moresca" or "morisca" and "latina" had been dropped, and these two chordophones were simply referred to as guitars.<ref>Tom and Mary Anne Evans. ''Guitars: From the Renaissance to Rock''. Paddington Press Ltd 1977 p. 16</ref> | |||

| The Spanish ], called in Italian the {{lang|la|viola da mano}}, a guitar-like instrument of the 15th and 16th centuries, is widely considered to have been the single most important influence in the development of the baroque guitar. It had six ] (usually), lute-like ] in fourths and a guitar-like body, although early representations reveal an instrument with a sharply cut waist. It was also larger than the contemporary four-course guitars. By the 16th century, the vihuela's construction had more in common with the modern guitar, with its curved one-piece ribs, than with the viols, and more like a larger version of the contemporary four-course guitars. The vihuela enjoyed only a relatively short period of popularity in Spain and Italy during an era dominated elsewhere in Europe by the ]; the last surviving published music for the instrument appeared in 1576.{{sfn|Turnbull et al}} | |||

| Meanwhile, the five-course ], which was documented in Spain from the middle of the 16th century, enjoyed popularity, especially in Spain, Italy and France from the late 16th century to the mid-18th century.<ref group=upper-alpha>"The first incontrovertible evidence of five-course instruments can be found in Miguel Fuenllana's ''Orphenica Lyre'' of 1554, which contains music for a ''vihuela de cinco ordenes''. In the following year, Juan Bermudo wrote in his ''Declaracion de Instrumentos Musicales'': 'We have seen a guitar in Spain with five courses of strings.' Bermudo later mentions in the same book that 'Guitars usually have four strings,' which implies that the five-course guitar was of comparatively recent origin, and still something of an oddity." Tom and Mary Anne Evans, ''Guitars: From the Renaissance to Rock''. Paddington Press Ltd, 1977, p. 24.</ref><ref group=upper-alpha>"We know from literary sources that the five course guitar was immensely popular in Spain in the early seventeenth century and was also widely played in France and Italy...Yet almost all the surviving guitars were built in Italy...This apparent disparity between the documentary and instrumental evidence can be explained by the fact that, in general, only the more expensively made guitars have been kept as collectors' pieces. During the early seventeenth century the guitar was an instrument of the people of Spain, but was widely played by the Italian aristocracy." Tom and Mary Anne Evans. ''Guitars: From the Renaissance to Rock''. Paddington Press Ltd, 1977, p. 24.</ref> In Portugal, the word ''viola'' referred to the guitar, as ''guitarra'' meant the "]", a variety of ]. | |||

| There were many different plucked instruments<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.guyguitars.com/eng/handbook/BriefHistory.html|title=A Brief History of the Guitar|website=Paul Guy Guitars|access-date=2019-02-25}}</ref> that were being invented and used in Europe during the Middle Ages. By the 16th century, most of the forms of guitar had fallen off, to never be seen again. However, midway through the 16th century, the five-course guitar<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.britannica.com/art/guitar|title=guitar {{!}} History & Facts|website=Encyclopedia Britannica|language=en|access-date=2019-02-25}}</ref> was established. It was not a straightforward process. There were two types of five-course guitars, differing in the location of the major third and in the interval pattern. The fifth course can be inferred because the instrument was known to play more than the sixteen notes possible with four. The guitar's strings were tuned in unison, so, in other words, it was tuned by placing a finger on the second fret of the thinnest string and tuning the guitar<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://acousticmusic.org/research/history/timeline-of-musical-styles-guitar-history/|title=Timeline of Musical Styles & Guitar History {{!}} Acoustic Music|website=acousticmusic.org|access-date=2019-02-25}}</ref> bottom to top. The strings were a whole octave apart from one another, which is the reason for the different method of tuning. Because it was so different, there was major controversy as to who created the five course guitar. A literary source, Lope de Vega's Dorotea, gives the credit to the poet and musician ]. This claim was also repeated by Nicolas Doizi de Velasco in 1640, however this claim has been contested by others who state that Espinel's birth year (1550) make it impossible for him to be responsible for the tradition.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tp6LO9n1TrIC&q=origins+of+the+guitar&pg=PA1|title=The Guitar from the Renaissance to the Present Day|last=Turnbull|first=Harvey|date=2006|publisher=Bold Strummer|isbn=978-0-933224-57-5|language=en}}</ref> He believed that the tuning was the reason the instrument became known as the Spanish guitar in Italy. Even later, in the same century, ] wrote that other nations such as Italy or France added to the Spanish guitar. All of these nations even imitated the five-course guitar by "recreating" their own.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.guitarhistoryfacts.com/|title=History of the Guitar – Evolution of Guitars|website=Guitarhistoryfacts.com|access-date=2019-02-25}}</ref> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Finally, {{Circa|1850}}, the form and structure of the modern guitar were developed by different Spanish makers such as ] and, perhaps the most important of all guitar makers, ], who increased the size of the guitar body, altered its proportions, and invented the breakthrough fan-braced pattern. Bracing, the internal pattern of wood reinforcements used to secure the guitar's top and back and prevent the instrument from collapsing under tension, is an important factor in how the guitar sounds. Torres' design greatly improved the volume, tone, and projection of the instrument, and it has remained essentially unchanged since. | |||

| ==Types== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ]'' ({{Circa|1672}}), by ]]] | |||

| Guitars are often divided into two broad categories: ] and ]. Within each category, there are further sub-categories that are nearly endless in quantity and are always evolving. For example, an electric guitar can be purchased in a six-string model (the most common model) or in ] or ] formats. An instruments overall design, internal construction and components, wood type or species, hardware and electronic appointments all add to the abundant nature of sub-categories and its unique tonal & functional property. | |||

| ===Acoustic=== | |||

| {{Main|Acoustic guitar}} | |||

| {{See also|Extended-range classical guitar|Flamenco guitar|Chitarra battente|Guitarrón mexicano|Harp guitar|Russian guitar|Selmer guitar|Tenor guitar}} | |||

| {{Listen | |||

| | filename = romanza_española.ogg | |||

| | title = Classical Guitar Sample | |||

| | description = Spanish Romance | |||

| }} | |||

| Acoustic guitars form several notable subcategories within the acoustic guitar group: classical and ]s; steel-string guitars, which include the flat-topped, or "folk", guitar; ]s; and the arched-top guitar. The acoustic guitar group also includes unamplified guitars designed to play in different registers, such as the acoustic bass guitar, which has a similar tuning to that of the electric bass guitar. | |||

| ====Renaissance and Baroque==== | |||

| {{Main|Baroque guitar}} | |||

| Renaissance and Baroque guitars are the ancestors of the modern ] and ]. They are substantially smaller, more delicate in construction, and generate less volume. The strings are paired in courses as in a modern ], but they only have four or five courses of strings rather than six single strings normally used now. They were more often used as rhythm instruments in ensembles than as solo instruments, and can often be seen in that role in ] performances. (]'s ''Instrucción de Música sobre la Guitarra Española'' of 1674 contains his whole output for the solo guitar.)<ref>The Guitar (From The Renaissance To The Present Day) by Harvey Turnbull (Third Impression 1978) – Publisher: Batsford. p57 (Chapter 3 – The Baroque, Era Of The Five Course Guitar)</ref> ] and ] guitars are easily distinguished, because the Renaissance guitar is very plain and the Baroque guitar is very ornate, with ivory or wood inlays all over the neck and body, and a paper-cutout inverted "wedding cake" inside the hole. | |||

| ====Classical==== | |||

| hi my name is bobby | |||

| {{Main|Classical guitar}} | |||

| Classical guitars, also known as "Spanish" guitars,<ref name=CMUSE>{{cite web |url=https://www.cmuse.org/what-is-a-classical-guitar/ | |||

| |title=What Is A Classical Guitar? |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |date=April 18, 2017 |website=Cmuse.org |access-date=June 4, 2018 }}</ref> are typically strung with nylon strings, plucked with the fingers, played in a seated position and are used to play a diversity of musical styles including ]. The classical guitar's wide, flat neck allows the musician to play scales, arpeggios, and certain chord forms more easily and with less adjacent string interference than on other styles of guitar. ]s are very similar in construction, but they are associated with a more percussive tone. In Portugal, the same instrument is often used with steel strings particularly in its role within ] music. The guitar is called ], or ] in Brazil, where it is often used with an extra seventh string by ] musicians to provide extra bass support. | |||

| In Mexico, the popular ] band includes a range of guitars, from the small '']'' to the '']'', a guitar larger than a cello, which is tuned in the bass register. In Colombia, the traditional quartet includes a range of instruments too, from the small '']'' (sometimes known as the Deleuze-Guattari, for use when traveling or in confined rooms or spaces), to the slightly larger ], to the full-sized classical guitar. The requinto also appears in other Latin-American countries as a complementary member of the guitar family, with its smaller size and scale, permitting more projection for the playing of single-lined melodies. Modern dimensions of the classical instrument were established by the Spaniard ] (1817–1892).<ref>{{cite web | |||

| == Types of Guitar == | |||

| |last=Morrish | |||

| |first=John | |||

| |title=Antonio De Torres | |||

| |publisher=Guitar Salon International | |||

| |url=http://www.guitarsalon.com/articles.php?articleid=18 | |||

| |access-date=2011-05-08}}</ref> | |||

| ====Flat-top==== | |||

| Guitars can be divided into two broad categories, acoustic and electric: | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Main|Steel-string acoustic guitar}} | |||

| Flat-top guitars with steel strings are similar to the ], however, the flat-top body size is usually significantly larger than a classical guitar, and has a narrower, reinforced neck and stronger structural design. The robust X-bracing typical of flat-top guitars was developed in the 1840s by German-American luthiers, of whom ] is the best known. Originally used on gut-strung instruments, the strength of the system allowed the later guitars to withstand the additional tension of steel strings. Steel strings produce a brighter tone and a louder sound. The acoustic guitar is used in many kinds of music including folk, country, bluegrass, pop, jazz, and blues. Many variations are possible from the roughly classical-sized ] and ] to the large ] (the most commonly available type) and ]. ] makes a modern variation, with a rounded back/side assembly molded from artificial materials. | |||

| === |

====Archtop==== | ||

| {{ |

{{Main|Archtop guitar}} | ||

| Archtop guitars are steel-string instruments in which the top (and often the back) of the instrument are carved from a solid billet, into a curved, rather than flat, shape. This violin-like construction is usually credited to the American ]. ] of the ] introduced the violin-inspired F-shaped hole design now usually associated with archtop guitars, after designing a style of ] of the same type. The typical archtop guitar has a large, deep, hollow body whose form is much like that of a mandolin or a violin-family instrument. Nowadays, most archtops are equipped with magnetic pickups, and they are therefore both acoustic and electric. F-hole archtop guitars were immediately adopted, upon their release, by both ] and ] musicians, and have remained particularly popular in jazz music, usually with ]. | |||

| An acoustic guitar is not dependent on any external device for amplification. The shape and resonance of the guitar itself creates acoustic amplification. However, the unamplified guitar is not a loud instrument. It cannot compete with other instruments commonly found in bands and orchestras, in terms of sheer audible volume. Many acoustic guitars are available today with built-in electronics and power to enable amplification. | |||

| ====Resonator, resophonic or Dobros==== | |||

| There are several subcategories within the acoustic guitar group: steel string guitars, which includes the flat top, or "folk" guitar, the closely related twelve string guitar, and the arch top guitar. A recent arrival in the acoustic guitar group is the acoustic bass guitar, similar in tuning to the electric bass. | |||

| ] tricone ]]] | |||

| {{Main|Resonator guitar|Dobro}} | |||

| All three principal types of resonator guitars were invented by the Slovak-American ] (1893–1988) for the National and Dobro ('''Do'''pyera '''Bro'''thers) companies. Similar to the flat top guitar in appearance, but with a body that may be made of brass, nickel-silver, or steel as well as wood, the sound of the resonator guitar is produced by one or more aluminum resonator cones mounted in the middle of the top. The physical principle of the guitar is therefore similar to the ]. | |||

| The original purpose of the resonator was to produce a very loud sound; this purpose has been largely superseded by ], but the resonator guitar is still played because of its distinctive tone. Resonator guitars may have either one or three resonator cones. The method of transmitting sound resonance to the cone is either a "biscuit" bridge, made of a small piece of hardwood at the vertex of the cone (Nationals), or a "spider" bridge, made of metal and mounted around the rim of the (inverted) cone (Dobros). Three-cone resonators always use a specialized metal bridge. The type of resonator guitar with a neck with a square cross-section—called "square neck" or "Hawaiian"—is usually played face up, on the lap of the seated player, and often with a metal or glass ]. The round neck resonator guitars are normally played in the same fashion as other guitars, although slides are also often used, especially in blues. | |||

| *''] and ] ]'': These are the gracile ancestors of the modern ]. They are substantially smaller and more delicate than the classical guitar, and generate a much quieter sound. The strings are paired in courses as in a modern ], but they only have four or five courses of strings rather than six. They were more often used as rhythm instruments in ensembles than as solo instruments, and can often be seen in that role in ] performances. (]' ''Instrucción de Música sobre la Guitarra Española'' of 1674 constitutes the majority of the surviving solo corpus for the era.) Renaissance and Baroque guitars are easily distinguished because the Renaissance guitar is very plain and the Baroque guitar is very ornate, with inlays all over the neck and body, and a paper-cutout inverted "wedding cake" inside the hole. | |||

| ====Steel guitar==== | |||

| *'']s'': These are typically strung with nylon strings, played in a seated position and are used to play a diversity of musical styles including ]. The classical guitar is designed to allow for the execution of solo polyphonic arrangements of music in much the same manner as the pianoforte can. This is the major point of difference in design intent between the classical instrument and other designs of guitar. ]s are very similar in construction, have a sharper sound, and are used in ]. In Mexico, the popular ] band includes a range of guitars, from the tiny ] to the ], a guitar larger than a cello, which is tuned in the bass register. In Colombia, the traditional quartet includes a range of instruments too, from the small bandola (sometimes known as the Deleuze-Guattari, for use when travelling or in confined rooms or spaces), to the slightly larger tiple, to the full sized classical guitar. Modern dimensions of the classical instrument were established by ] (1817-1892). Classical guitars are sometimes referred to as classic guitars, which is a more proper translation from the Spanish. | |||

| {{Main|Lap steel guitar|Pedal steel guitar}} | |||

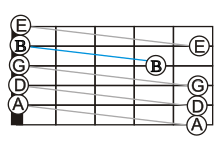

| A ] is any guitar played while moving a polished ] or similar hard object against plucked strings. The bar itself is called a "steel" and is the source of the name "steel guitar". The instrument differs from a conventional guitar in that it does not use frets; conceptually, it is somewhat akin to playing a guitar with one finger (the bar). Known for its ] capabilities, gliding smoothly over every pitch between notes, the instrument can produce a sinuous crying sound and deep ] emulating the human singing voice. Typically, the strings are plucked (not strummed) by the fingers of the dominant hand, while the steel tone bar is pressed lightly against the strings and moved by the opposite hand. The instrument is played while sitting, placed horizontally across the player's knees or otherwise supported. The horizontal playing style is called "Hawaiian style".<ref name="premier-ross">{{cite magazine |last1=Ross |first1=Michael |title=Pedal to the Metal: A Short History of the Pedal Steel Guitar |url=https://www.premierguitar.com/articles/22152-pedal-to-the-metal-a-short-history-of-the-pedal-steel-guitar |magazine=] |access-date=September 1, 2017 |date=February 17, 2015}}</ref> | |||

| *'']'': Is a 12 string guitar used in ] for the traditional ] song. Its true origins are somewhat uncertain but there is a general agreement that it goes back to the medieval period. It is often mistakenly thought of to be based on the so-called "English guitar" - a common error as there is no such thing. For some time the best instruments of this and other types were made in England, hence the confusion. "English guitar" refers to a quality standard, not really an instrument type. This particular instrument is most likely a merge of medieval "cistre" or "citar" and the Arabic lute. | |||

| ====Twelve-string ==== | |||

| *'']'': Similar to the ], however the body size is usually significantly larger than a classical guitar and it has a narrower, reinforced neck and stronger structural design, to sustain the extra tension of steel strings which produce a brighter tone, and according to some players, a louder sound. The acoustic guitar is a staple in ], ] and ]. | |||

| {{Main|Twelve-string guitar}} | |||

| The ] usually has steel strings, and it is widely used in ], ], and ]. Rather than having only six strings, the 12-string guitar has six ] made up of two strings each, like a ] or ]. The highest two courses are tuned in unison, while the others are tuned in octaves. The 12-string guitar is also made in electric forms. The chime-like sound of the 12-string electric guitar was the basis of ]. | |||

| ====Acoustic bass==== | |||

| *'']s'' are steel string instruments which feature a violin-inspired f-hole design in which the top (and often the back) of the instrument are carved in a curved rather than a flat shape. ] of the ] invented this variation of guitar after designing a style of ] of the same type. The typical Archtop is a hollow body guitar whose form is much like that of a mandolin or violin family instrument and may be acoustic or electric. Some solid body electric guitars are also considered archtop guitars although usually 'Archtop guitar' refers to the hollow body form. Archtop guitars were immediately adopted upon their release by both ] and ] musicians and have remained particularly popular in jazz music, usually using thicker strings (higher gauged round wound and flat wound) than acoustic guitars. Archtops are often louder than a typical dreadnought acoustic guitar. The electric hollow body archtop guitar has a distinct sound among electric guitars and is consequently appropriate for many styles of ]. Many electric archtop guitars intended for use in ] even have a ]. | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Main|Acoustic bass guitar}} | |||

| The acoustic bass guitar is a bass instrument with a hollow wooden body similar to, though usually somewhat larger than, that of a six-string acoustic guitar. Like the traditional ] and the ], the acoustic bass guitar commonly has four strings, which are normally tuned E-A-D-G, an ] below the lowest four strings of the six-string guitar, which is the same tuning pitch as an electric bass guitar. It can, more rarely, be found with five or six strings, which provides a wider range of notes to be played with less movement up and down the neck. | |||

| ===Electric=== | |||

| *'']'', ''resophonic'' or ''] guitars'': Similar to the flat top guitar in appearance, but with sound produced by a metal resonator mounted in the middle of the top rather than an open sound hole, so that the physical principle of the guitar is actually more similar to the ]. The purpose of the resonator is to amplify the sound of the guitar; this purpose has been largely superseded by electrical amplification, but the resonator is still played by those desiring its distinctive sound.<p>Resonator guitars may have either one resonator cone or three resonator cones. Three cone resonators have two cones on the left above one another and one cone immediately to the right. The method of transmitting sound resonance to the cone is either a BISCUIT bridge, made of a small piece of hardwood, or a SPIDER bridge, made of metal and larger in size. Three cone resonators always use a specialised metal spider bridge.</p><p>The type of resonator guitar with a neck with a square cross-section -- called "square neck" -- is usually played face up, on the lap of the seated player, and often with a metal or glass ]. The round neck resonator guitars are normally played in the same fashion as other guitars, although slides are also often used, especially in blues.</p> | |||

| {{Main|Electric guitar}} | |||

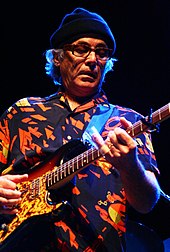

| ] playing his signature custom-made "]" | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Electric guitars can have solid, semi-hollow, or hollow bodies; solid bodies produce little sound without amplification. In contrast to a standard acoustic guitar, electric guitars instead rely on ] ], and sometimes ] pickups, that convert the vibration of the steel strings into ], which are fed to an ] through a ] or ] ]. The sound is frequently modified by other electronic devices (]) or the natural ] of valves (]s) or the pre-amp in the amplifier. There are two main types of magnetic pickups, ]- and double-coil (or ]), each of which can be ] or ]. The electric guitar is used extensively in ], ], ], and ]. The first successful magnetic pickup for a guitar was invented by ], and incorporated into the 1931 Ro-Pat-In (later ]) ] lap steel; other manufacturers, notably ], soon began to install pickups in archtop models. After World War II the completely solid-body electric was popularized by Gibson in collaboration with ], and independently by ] of ]. The lower fretboard ] (the height of the strings from the fingerboard), lighter (thinner) strings, and its electrical amplification lend the electric guitar to techniques less frequently used on acoustic guitars. These include ], extensive use of ] through ]s and ]s (also known as slurs), ]s, ], and use of a ] or ]. | |||

| Some electric guitar models feature ] pickups, which function as ]s to provide a sound closer to that of an acoustic guitar with the flip of a switch or knob, rather than switching guitars. Those that combine piezoelectric pickups and magnetic pickups are sometimes known as hybrid guitars.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.guitarnoize.com/blog/category/hybrid-guitars/ |title=Hybrid guitars |website=Guitarnoize.com |access-date=2010-06-15 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101225153202/http://www.guitarnoize.com/blog/category/hybrid-guitars |archive-date=2010-12-25 }}</ref> | |||

| *'']s'' usually have steel strings and are widely used in ], ] and ]. Rather than having only six strings, the 12-string guitar has pairs, like a ]. Each pair of strings is tuned either in unison (the two highest) or an octave apart (the others). They are made both in acoustic and electric forms. | |||

| Hybrids of acoustic and electric guitars are also common. There are also more exotic varieties, such as guitars with ], three,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://vai.com/Machines/guitarpages/guitar040.html |title=The Official Steve Vai Website: The Machines |website=Vai.com |date=1993-08-03 |access-date=2010-06-15 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100130043815/http://www.vai.com/Machines/guitarpages/guitar040.html |archive-date=2010-01-30 }}</ref> or rarely four necks, all manner of alternate string arrangements, ] (used almost exclusively on bass guitars, meant to emulate the sound of a ]), ], and such. | |||

| *'']s'' are seven string acoustic guitars which were the norm for Russian guitarists throughout the 19th and well into the 20th centuries. The guitar is traditionally tuned to an open G major tuning. | |||

| ====Seven-string and eight-string ==== | |||

| *'']s'' were developed in the early 1970s by Ernie Ball. They have steel strings and the same tuning as an electric ], . | |||

| {{Main|Seven-string guitar|eight-string guitar}} | |||

| Solid-body seven-string guitars were popularized in the 1980s and 1990s. Other artists go a step further, by using an eight-string guitar with two extra low strings. Although the most common seven-string has a low B string, ] (of ] and ]) uses an octave G string paired with the regular G string as on a 12-string guitar, allowing him to incorporate chiming 12-string elements in standard six-string playing. In 1982 ] developed the "Sky Guitar", with a vastly extended number of frets, which was the first guitar to venture into the upper registers of the violin. Roth's seven-string and "Mighty Wing" guitar features a wider octave range.{{Citation needed|date=April 2011}} | |||

| ====Electric bass ==== | |||

| *'']'' There's very sketchy background information about tenor guitars on the World Wide Web. A number of classical guitarists call the Niibori prime guitar a "Tenor Guitar" on the grounds that it sits in pitch between the alto and the bass. Elsewhere, the name is taken for a 4-string guitar, with a scale length of 23" (585mm) - about the same as a Terz Guitar. But the guitar is tuned in fifths - C G D A - like the tenor banjo or the cello. Indeed it is generally accepted that the tenor guitar was created to allow a tenor banjo player to follow the fashion as it evolved from from Dixieland Jazz towards the more progressive Jazz that featured guitar. It allows a tenor banjo player to provide a guitar-based rhythm section with nothing to learn. A small minority of players close tuned the instrument to D G B E to produce a deep instrument that could be played with the 4-note chord shapes found on the top 4 strings of the guitar or ukulele. In fact, though, the deep pitch warrants the wide-spaced chords that the banjo tuning permits, and the close tuned tenor does not have the same full, clear sound. | |||

| {{Main|Bass guitar}} | |||

| ] bass guitar that has been recognized by many music fans for decades as the bass used by ] for almost 60 years]] | |||

| The bass guitar (also called an "electric bass", or simply a "bass") is similar in appearance and construction to an electric guitar, but with a longer neck and ], and four to six strings. The four-string bass, by far the most common, is usually tuned the same as the ], which corresponds to pitches one octave lower than the four lowest pitched strings of a guitar (E, A, D, and G). The bass guitar is a ], as it is notated in ] an octave higher than it sounds (as is the double bass) to avoid excessive ]s being required below the ]. Like the electric guitar, the bass guitar has ] and it is plugged into an ] for live performances. | |||

| ==Construction== | |||

| *'']s''. Harp Guitars are difficult to classify as there are many variations within this type of guitar. They are typically rare and uncommon in the popular music scene. Most consist of a regular guitar, plus additional 'harp' strings strung above the six normal strings. The instrument is usually acoustic and the harp strings are usually tuned to lower notes than the guitar strings, for an added bass range. Normally there is neither fingerboard nor frets behind the harp strings. Some harp guitars also feature much higher pitch strings strung below the traditional guitar strings. The number of harp strings varies greatly, depending on the type of guitar and also the player's personal preference (as they have often been made to the player's specification). The Pikasso guitar; 4 necks, 2 sound holes, 42 strings] and also the Oracle Harp ]; 24 strings (with 12 sympathetic strings protruding through the neck) are modern examples. | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| | image1 = Acoustic guitar parts.png | |||

| | width1 = 216 | |||

| | image2 = Electric guitar parts.jpg | |||

| | width2 = 175 | |||

| | footer = {{div col|colwidth=30em}} | |||

| #] | |||

| #] | |||

| #]s (or pegheads, tuning keys, tuning machines, tuners) | |||

| #] | |||

| #] cover | |||

| #] | |||

| #] | |||

| #] Neckjoint (electric); ] | |||

| #] | |||

| #] | |||

| #] | |||

| #] | |||

| #] | |||

| #Back | |||

| #] (top) | |||

| #Body sides (ribs) | |||

| #], with ] inlay | |||

| #] | |||

| #] | |||

| #] (or Fingerboard) | |||

| {{div col end}} | |||

| }} | |||

| ===Handedness=== | |||

| *''Extended-range guitars''. For well over a century guitars featuring ], eight, nine, ten or more strings have been used by a minority of guitarists as a means of increasing the range of pitch available to the player. Usually this entails the addition of extra bass strings. | |||

| {{See also|List of musicians who play left-handed}} | |||

| Modern guitars can be constructed to suit both left- and right-handed players. Typically the dominant hand is used to pluck or strum the strings. This is similar to the ] family of instruments where the dominant hand controls the bow. Left-handed players usually play a mirror image instrument manufactured especially for left-handed players.<ref name="leftyfretz">{{cite web |title=What is the Difference Between a Left and Right Handed Guitar? |url=https://leftyfretz.com/right-left-handed-guitar-difference/ |website=leftyfretz.com |access-date=February 25, 2021 |date=January 20, 2020}}</ref> There are other options, some unorthodox, including learn to play a right-handed guitar as if the player is right-handed or playing an unmodified right-handed guitar reversed. Guitarist ] played a right-handed guitar strung in reverse (the treble strings and bass strings reversed).<ref name="shapirogleb">{{cite book |last1=Shapiro |first1=Harry |last2=Glebbeeck |first2=Caesar |title=Jimi Hendrix Electric Gypsy |date=1990 |publisher=St. Martin's Griffin |location=New York |isbn=0-312-13062-7 |page=38 |edition=1st |url=https://archive.org/details/jimihendrixelect00shap/page/38/mode/2up |access-date=February 25, 2021}}</ref> The problem with doing this is that it reverses the guitar's saddle angle.<ref name="leftyfretz"/> The saddle is the strip of material on top of the bridge where the strings rest. It is normally slanted slightly, making the bass strings longer than the treble strings.<ref name="leftyfretz"/> In part, the reason for this is the difference in the thickness of the strings.<ref name="stackexch">{{cite web |title=Why is my guitar's saddle at an angle? |url=https://music.stackexchange.com/questions/1567/why-is-my-guitars-saddle-at-an-angle |website=music.stackexchange.com |publisher=Stack Exchange Network |access-date=February 25, 2021}}</ref> Physical properties of the thicker bass strings require them to be slightly longer than the treble strings to correct ].<ref name="stackexch"/> Reversing the strings, therefore, reverses the orientation of the saddle, adversely affecting intonation. | |||

| ===Components=== | |||

| *'']''. The battente is smaller than a classical guitar, usually played with four or five metal strings. It is mainly used in ] (a region in southern Italy) to accompany the voice. | |||

| ====Head==== | |||

| {{Main|Headstock}} | |||

| {{See also|Nut (string instrument)}} | |||

| ] Steinberger bass guitar.]] | |||

| The headstock is located at the end of the guitar neck farthest from the body. It is fitted with machine heads that adjust the tension of the strings, which in turn affects the pitch. The traditional tuner layout is "3+3", in which each side of the headstock has three tuners (such as on ]s). In this layout, the headstocks are commonly symmetrical. Many guitars feature other layouts, including six-in-line tuners (featured on ]s) or even "4+2" (e.g. Ernie Ball Music Man). Some guitars (such as ]s) do not have headstocks at all, in which case the tuning machines are located elsewhere, either on the body or the bridge. | |||

| The nut is a small strip of ], ], ], ], ], ], or other medium-hard material, at the joint where the headstock meets the fretboard. Its grooves guide the strings onto the fretboard, giving consistent lateral string placement. It is one of the endpoints of the strings' vibrating length. It must be accurately cut, or it can contribute to tuning problems due to string slippage or string buzz. To reduce string friction in the nut, which can adversely affect tuning stability, some guitarists fit a roller nut. Some instruments use a zero fret just in front of the nut. In this case the nut is used only for lateral alignment of the strings, the string height and length being dictated by the zero fret. | |||

| ] has the features of most electric guitars: multiple pickups, a whammy bar, volume and tone knobs.]] | |||

| === |

====Neck==== | ||

| {{Unreferenced section|date=February 2020}} | |||

| {{main|Electric guitar}} | |||

| {{Main|Neck (music)}} | |||

| Electric guitars can have solid, semi-hollow, or hollow bodies, and produce little sound without amplification. ] ]s (single and double coil) convert the vibration of the steel strings into ]s which are fed to an ] through a ] or ] ]. The sound is frequently modified by other electronic devices or the natural ] of valves (]s) in the amplifier. The electric guitar is used extensively in ], ] and ], and was commercialized by ] together with ] and independently by ] of Fender Music. The lower fretboard action (the height of the strings from the fingerboard) and its electrical amplification lend the electric guitar to some techniques which are less frequently used on acoustic guitars. These techniques include ], extensive use of ] through ]s and ]s (also known as slurs in the traditional Classical genre), ]s, ] and use of a ] or ]. | |||

| {{See also|Fingerboard|Fret|Truss rod|Inlay (guitar)|Set-in neck|Bolt-on neck|Neck-through}} | |||

| '']s'' were developed in the 1980's. Throughout the late 80's and 90's the seven string was popularized by the creation of the Ibanez Jem. The Jem was developed by Ibanez with close specifications and a specific feel that Steve Vai helped develop and master. Vai popularized the seven string and the seven string is heard in much of the rock music these days (earlier in ]) to achieve a much darker sound through extending the lower end of the guitar's range. They are used today by players such as ], ], ], ], ], and ]. ], ], ] & ] go a step further, using an '']'' with ''two'' extra low strings. Although the most commonly found 7 string is the variety in which there is one low B string, Roger McGuinn (Of Byrds/Rickenbacker Fame) has popularized a variety in which an octave G string is paired with the regular G string as on a 12 string guitar, allowing him to incorporate chiming 12 string elements in standard 6 string playing. Ibanez makes many varieties of electric 7 strings.<br> | |||

| A guitar's ], ], ], ], and ], all attached to a long wooden extension, collectively constitute its ]. The wood used to make the fretboard usually differs from the wood in the rest of the neck. The bending stress on the neck is considerable, particularly when heavier gauge strings are used (see ]), and the ability of the neck to resist bending (see ]) is important to the guitar's ability to hold a constant pitch during tuning or when strings are fretted. The rigidity of the neck with respect to the body of the guitar is one determinant of a good instrument versus a poor-quality one. | |||

| <br> | |||

| However, the most common method of achieving a darker, deeper sound is to tune the 6th string (E) to a low D, known as a 'drop D tuning'. Many of today's 'Dark Metal' and 'Nu Metal' bands use this tuning to add extra heaviness to their sound. ] uses an 'open G' tuning to achieve his particular heavy sound. ] sometimes uses a device known as a 'Drop D Tuner' which is a small lever attached to the tuner of the 6th string which easily allows him to drop down to a D with ease. <br> | |||

| <br> | |||

| The ] is similar in tuning to the traditional ] viol. | |||

| Hybrids of acoustic and electric guitars are also common. There are also more exotic varieties, such as ], all manner of alternate string arrangements, ] (used almost exclusively on bass guitars, meant to emulate the sound of a ]), ], and such. | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| Some electric guitar and electric bass guitar models feature ] pickups, which function as small microphones to provide a sound closer to that of an acoustic guitar with the flip of a switch or knob, rather than switching guitars. | |||

| | align = left | |||

| | image1 = Chris Squire, 2003 (1).jpg | |||

| | width1 = 248 | |||

| | alt1 = | |||

| | caption1 = | |||

| | image2 = Gibson EDS1275.jpg | |||

| | width2 = 215 | |||

| | alt2 = | |||

| | caption2 = | |||

| | footer = ''Triple Neck'' (Left) and ''Double Neck'' (Right) Guitars. | |||

| }} | |||

| The cross-section of the neck can also vary, from a gentle "C" curve to a more pronounced "V" curve. There are many different types of neck profiles available, giving the guitarist many options. Some aspects to consider in a guitar neck may be the overall width of the fretboard, scale (distance between the frets), the neck wood, the type of neck construction (for example, the neck may be glued in or bolted on), and the shape (profile) of the back of the neck. Other types of material used to make guitar necks are graphite (] guitars), aluminum (], ] and ]), or carbon fiber (] and ]). ] electric guitars have two necks, allowing the musician to quickly switch between guitar sounds. | |||

| The neck joint or heel is the point at which the neck is either bolted or glued to the body of the guitar. Almost all acoustic steel-string guitars, with the primary exception of Taylors, have glued (otherwise known as set) necks, while electric guitars are constructed using both types. Most classical guitars have a neck and headblock carved from one piece of wood, known as a "Spanish heel". Commonly used set neck joints include ] joints (such as those used by C. F. Martin & Co.), dovetail joints (also used by C. F. Martin on the D-28 and similar models) and Spanish heel neck joints, which are named after the shoe they resemble and commonly found in classical guitars. All three types offer stability. | |||

| ==Guitar components== | |||

| {{main|Guitar components}} | |||

| {{Cleanup-restructure|February 2007}} | |||

| <div style="float:left;padding-right:10px;">'''Parts of typical classical and electric guitars''' | |||

| # ] | |||

| # ] | |||

| # ]s (or pegheads, tuning keys,<br> tuning machines, tuners) | |||

| # ]s | |||

| # ] | |||

| # ]s | |||

| # ] | |||

| # Heel (acoustic or Spanish) - Neckjoint (electric) | |||

| # Body | |||

| # ] | |||

| # Electronics | |||

| # ] | |||

| # ] | |||

| # Back | |||

| # ] (top) | |||

| # Body sides (ribs) | |||

| # ], with ] inlay | |||

| # ] | |||

| # Saddle | |||

| # ] | |||

| </div> | |||

| Bolt-on necks, though they are historically associated with cheaper instruments, do offer greater flexibility in the guitar's set-up, and allow easier access for neck joint maintenance and repairs. Another type of neck, only available for solid-body electric guitars, is the ] construction. These are designed so that everything from the machine heads down to the bridge is located on the same piece of wood. The sides (also known as wings) of the guitar are then glued to this central piece. Some luthiers prefer this method of construction as they claim it allows better sustain of each note. Some instruments may not have a neck joint at all, having the neck and sides built as one piece and the body built around it. | |||

| <div style="float:left">]]</div> | |||

| The ], also called the fretboard, is a piece of wood embedded with metal frets that comprises the top of the neck. It is flat on classical guitars and slightly curved crosswise on acoustic and electric guitars. The curvature of the fretboard is measured by the fretboard radius, which is the radius of a hypothetical circle of which the fretboard's surface constitutes a segment. The smaller the fretboard radius, the more noticeably curved the fretboard is. Most modern guitars feature a 12" neck radius, while older guitars from the 1960s and 1970s usually feature a 6-8" neck radius. Pinching a string against a fret on the fretboard effectively shortens the vibrating length of the string, producing a higher pitch. | |||

| <br style="clear:both;"> | |||

| Fretboards are most commonly made of ], ], ], and sometimes manufactured using composite materials such as HPL or resin. See the section "Neck" below for the importance of the length of the fretboard in connection to other dimensions of the guitar. The fingerboard plays an essential role in the treble tone for acoustic guitars. The quality of vibration of the fingerboard is the principal characteristic for generating the best treble tone. For that reason, ebony wood is better, but because of high use, ebony has become rare and extremely expensive. Most guitar manufacturers have adopted rosewood instead of ebony. | |||

| === Headstock === | |||

| {{main|Headstock}} | |||

| ] playing a Fender guitar with a ] ]] | |||

| The headstock is located at the end of the guitar neck furthest from the body. It is fitted with machine heads that adjust the tension of the strings, which in turn affects the pitch. Traditional tuner layout is "3+3" in which each side of the headstock has three tuners (such as on ]s). In this layout, the headstocks are commonly symmetrical. Many guitars feature other layouts as well, including six-in-line (featured on ]s) tuners or even "4+2" (Ernie Ball Music Man). However, some guitars (such as ]s) do not have headstocks at all, in which case the tuning machines are located elsewhere, either on the body or the bridge. | |||

| === |

=====Frets===== | ||

| Almost all guitars have frets, which are metal strips (usually nickel alloy or stainless steel) embedded along the fretboard and located at exact points that divide the scale length in accordance with a specific mathematical formula. The exceptions include ] guitars and very rare fretless guitars. Pressing a string against a fret determines the strings' vibrating length and therefore its resultant pitch. The pitch of each consecutive fret is defined at a half-step interval on the ]. Standard classical guitars have 19 frets and electric guitars between 21 and 24 frets, although guitars have been made with as many as 27 frets. Frets are laid out to accomplish an ] division of the octave. Each set of twelve frets represents an octave. The twelfth fret divides the ] exactly into two halves, and the 24th fret position divides one of those halves in half again. | |||

| {{main|Nut (instrumental)}} | |||

| The ] of the spacing of two consecutive frets is <math>\sqrt{2}</math> (]). In practice, ] determine fret positions using the constant 17.817—an approximation to 1/(1-1/<math>\sqrt{2}</math>). If the nth fret is a distance x from the bridge, then the distance from the (n+1)th fret to the bridge is x-(x/17.817).<ref name="Calculating Fret Positions">{{cite web |last=Mottola |first=R.M. |title=Lutherie Info—Calculating Fret Positions |url=http://www.liutaiomottola.com/formulae/fret.htm}}</ref> Frets are available in several different gauges and can be fitted according to player preference. Among these are "jumbo" frets, which have a much thicker gauge, allowing for use of a slight vibrato technique from pushing the string down harder and softer. "Scalloped" fretboards, where the wood of the fretboard itself is "scooped out" between the frets, allow a dramatic vibrato effect. Fine frets, much flatter, allow a very low ], but require that other conditions, such as curvature of the neck, be well-maintained to prevent buzz. | |||

| The nut is a small strip of ], ], ], ], ], ], or other medium-hard material, at the joint where the headstock meets the fretboard. Its grooves guide the strings onto the fretboard, giving consistent lateral string placement. It is one of the endpoints of the strings' vibrating length. It must be accurately cut, or it can contribute to tuning problems due to string slippage, and/or string buzz. | |||

| === |

=====Truss rod===== | ||

| {{main|Fingerboard}} | |||

| The truss rod is a thin, strong metal rod that runs along the inside of the neck. It is used to correct changes to the neck's curvature caused by aging of the neck timbers, changes in humidity, or to compensate for changes in the tension of strings. The tension of the rod and neck assembly is adjusted by a hex nut or an allen-key bolt on the rod, usually located either at the headstock, sometimes under a cover, or just inside the body of the guitar underneath the fretboard and accessible through the sound hole. Some truss rods can only be accessed by removing the neck. The truss rod counteracts the immense amount of tension the strings place on the neck, bringing the neck back to a straighter position. Turning the truss rod clockwise tightens it, counteracting the tension of the strings and straightening the neck or creating a backward bow. Turning the truss rod counter-clockwise loosens it, allowing string tension to act on the neck and creating a forward bow. | |||

| Also called the '''fingerboard''', the ] is a piece of wood embedded with metal frets that comprises the top of the neck. It is flat on ]s and slightly curved crosswise on acoustic and electric guitars. The curvature of the fretboard is measured by the fretboard radius, which is the radius of a hypothetical circle of which the fretboard's surface constitutes a segment. The smaller the fretboard radius, the more noticeably curved the fretboard is. Most modern guitars feature a 12" neck radius, while older guitars from the '60's and '70's usually feature a 6" - 8" neck radius. Pinching a string against the fretboard effectively shortens the vibrating length of the string, producing a higher pitch. Fretboards are most commonly made of ], ], ], and sometimes manufactured or composite materials such as HPL or resin. | |||

| Adjusting the truss rod affects the intonation of a guitar as well as the height of the strings from the fingerboard, called the ]. Some truss rod systems, called ''double action'' truss systems, tighten both ways, pushing the neck both forward and backward (standard truss rods can only release to a point beyond which the neck is no longer compressed and pulled backward). The artist and ] Irving Sloane pointed out, in his book ''Steel-String Guitar Construction'', that truss rods are intended primarily to remedy concave bowing of the neck, but cannot correct a neck with "back bow" or one that has become twisted.<ref> | |||

| ===Frets=== | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| {{main|Fret}} | |||

| |last= Sloane | |||

| |first= Irving | |||

| |date= 1975 | |||

| |title= Steel-string Guitar Construction: Acoustic Six-string, Twelve-string, and Arched-top Guitars | |||

| |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2sAXAQAAIAAJ&q=back+bow | |||

| |location= | |||

| |publisher=Dutton | |||

| |page= 45 | |||

| |isbn= 978-0-87-690172-4 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> Classical guitars do not require truss rods, as their nylon strings exert a lower tensile force with lesser potential to cause structural problems. However, their necks are often reinforced with a strip of harder wood, such as an ] strip that runs down the back of a ] neck. There is no tension adjustment on this form of reinforcement. | |||

| =====Inlays===== | |||

| Frets are metal strips (usually nickel alloy or stainless steel) embedded along the fretboard which are placed in points along the length of string that divide it mathematically. When strings are pressed down behind them, frets shorten the strings' vibrating lengths to produce different pitches- each one is spaced a half-step apart on the 12 tone scale. For more on fret spacing, see the '']'' section below. Frets are usually the first permanent part to wear out on a heavily played electric guitar. They can be re-shaped to a certain extent and can be replaced as needed. Frets also indicate fractions of the length of a string (the string midpoint is at the 12th fret; one-third the length of the string reaches from the nut to the 7th fret, the 7th fret to the 19th, and the 19th to the saddle; one-quarter reaches from nut to fifth to twelfth to twenty-fourth to saddle). This feature is important in playing ]. Frets are available in several different gauges, depending on the type of guitar and the player's style. | |||

| {{More sources needed section|date=September 2023}} | |||

| Inlays are visual elements set into the exterior surface of a guitar, both for decoration and artistic purposes and, in the case of the markings on the 3rd, 5th, 7th and 12th fret (and in higher octaves), to provide guidance to the performer about the location of frets on the instrument.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Reyes |first=Daniel |date=2023-07-03 |title=What Are The Dots On A Guitar Fretboard For? (2023) |url=https://www.guitarbased.com/what-are-the-dots-on-a-guitar-fretboard-for/ |access-date=2023-09-20 |website=Guitar Based |language=en-US}}</ref> The typical locations for inlay are on the fretboard, headstock, and on acoustic guitars around the soundhole, known as the ]. Inlays range from simple plastic dots on the fretboard to intricate works of art covering the entire exterior surface of a guitar (front and back). Some guitar players have used ]s in the fretboard to produce unique lighting effects onstage. Fretboard inlays are most commonly shaped like dots, diamond shapes, parallelograms, or large blocks in between the frets. | |||

| Dots are usually inlaid into the upper edge of the fretboard in the same positions, small enough to be visible only to the player. These usually appear on the odd-numbered frets, but also on the 12th fret (the one-] mark) instead of the 11th and 13th frets. Some older or high-end instruments have inlays made of mother of pearl, abalone, ivory, colored wood or other exotic materials and designs. Simpler inlays are often made of plastic or painted. High-end classical guitars seldom have fretboard inlays as a well-trained player is expected to know his or her way around the instrument. In addition to fretboard inlay, the headstock and soundhole surround are also frequently inlaid. The manufacturer's logo or a small design is often inlaid into the headstock. Rosette designs vary from simple concentric circles to delicate fretwork mimicking the historic rosette of lutes. Bindings that edge the finger and soundboards are sometimes inlaid. Some instruments have a filler strip running down the length and behind the neck, used for strength or to fill the cavity through which the truss rod was installed in the neck. | |||

| Most guitars have ]s on the ] to fix the positions of notes and ], which gives them ]. Consequently, the ] of the spacing of two consecutive frets is the ] <math>\sqrt{2}</math>, whose numeric value is about 1.059463. The twelfth fret divides the ] in two exact halves and the 24th fret (if present) divides the ] in half yet again. Every twelve frets represents one octave. In practice, ] determine fret positions using the constant 17.817152, which is derived from the ]. The ] divided by this value yields the distance from the nut to the first fret. That distance is subtracted from the ] and the result is divided in two sections by the constant to yield the distance from the first fret to the second fret. Positions for the remainder of the frets are calculated in like manner.<ref name="Calculating Fret Positions">{{cite web|last=Mottola|first=R.M.|title=Lutherie Info – Calculating Fret Positions|url=http://www.liutaiomottola.com/formulae/fret.htm}}</ref> | |||

| ====Body==== | |||

| There are several styles of fret, which allow different sounds and techniques to be exploited by the player. Among these are "jumbo" frets, which have much thicker wires, allowing for a lighter touch and a slight vibrato technique simply from pushing the string down harder and softer, "scalloped" fretboards, where the wood of the fretboard itself is "scooped out", becoming deeper away from the headstock, which allows a dramatic vibrato effect and other unusual techniques, and fine frets, much flatter, which allow a very low string-action for extremely fast playing, but require other conditions (such as curvature of the neck) to be kept in perfect order to prevent buzz. | |||

| {{Unreferenced section|date=February 2020}} | |||

| {{Main|Sound box|Solid body|Bridge (instrument)|Pickguard}} | |||

| {{See also|Vibrato systems for guitar}} | |||

| ] | |||

| In acoustic guitars, string vibration is transmitted through the bridge and saddle to the body via ]. The sound board is typically made of tonewoods such as spruce or cedar. Timbers for tonewoods are chosen for both strength and ability to transfer mechanical energy from the strings to the air within the guitar body. Sound is further shaped by the characteristics of the guitar body's resonant cavity. In expensive instruments, the entire body is made of wood. In inexpensive instruments, the back may be made of plastic. | |||

| In an acoustic instrument, the body of the guitar is a major determinant of the overall sound quality. The guitar top, or soundboard, is a finely crafted and engineered element made of ]s such as ] and ]. This thin piece of wood, often only 2 or 3 mm thick, is strengthened by differing types of ]. Many luthiers consider the top the dominant factor in determining the sound quality. The majority of the instrument's sound is heard through the vibration of the guitar top as the energy of the vibrating strings is transferred to it. The body of an acoustic guitar has a sound hole through which sound projects. The sound hole is usually a round hole in the top of the guitar under the strings. The air inside the body vibrates as the guitar top and body is vibrated by the strings, and the response of the air cavity at different frequencies is characterized, like the rest of the guitar body, by a number of resonance modes at which it responds more strongly. | |||

| ===Truss rod=== | |||

| {{main|Truss rod}} | |||

| The top, back and ribs of an acoustic guitar body are very thin (1–2 mm), so a flexible piece of wood called lining is glued into the corners where the rib meets the top and back. This interior reinforcement provides 5 to 20 mm of solid gluing area for these corner joints. Solid linings are often used in classical guitars, while kerfed lining is most often found in steel-string acoustics. Kerfed lining is also called kerfing because it is scored, or "kerfed"(incompletely sawn through), to allow it to bend with the shape of the rib). During final construction, a small section of the outside corners is carved or routed out and filled with binding material on the outside corners and decorative strips of material next to the binding, which is called ]. This binding serves to seal off the end grain of the top and back. Purfling can also appear on the back of an acoustic guitar, marking the edge joints of the two or three sections of the back. Binding and purfling materials are generally made of either wood or plastic. | |||

| The '''truss rod''' is a metal rod that runs along the inside of the neck. Its tension is adjusted by a hex nut or an allen-key bolt usually located either at the headstock (sometimes under a cover) or just inside the body of the guitar, underneath the fretboard (accessible through the sound hole). Some truss rods can only be accessed by removing the neck, forcing the luthier to replace it after every adjustment to check its accuracy. The truss rod counteracts the immense amount of tension the strings place on the neck, bringing the neck back to a straighter position. The truss rod can be adjusted to compensate for changes in the neck wood due to changes in humidity or to compensate for changes in the tension of strings. Tightening the rod will curve the neck back and loosening it will return it forward. Adjusting the truss rod affects the intonation of a guitar as well as affecting the action (the height of the strings from the fingerboard). Some truss rod systems, called "double action" truss systems, will tighten both ways, allowing the neck to be pushed both forward and backward (most truss rods can only be loosened so much, beyond which the bolt will just come loose and the neck will no longer be pulled backward). Most classical guitars do not have truss rods, as the nylon strings do not put enough tension on the neck for one to be needed. | |||

| Body size, shape and style have changed over time. 19th-century guitars, now known as salon guitars, were smaller than modern instruments. Differing patterns of internal bracing have been used over time by luthiers. Torres, Hauser, Ramirez, Fleta, and ] were among the most influential designers of their time. Bracing not only strengthens the top against potential collapse due to the stress exerted by the tensioned strings but also affects the resonance characteristics of the top. The back and sides are made out of a variety of timbers such as mahogany, Indian ] and highly regarded Brazilian rosewood (''Dalbergia nigra''). Each one is primarily chosen for their aesthetic effect and can be decorated with inlays and purfling. | |||

| ===Inlays=== | |||

| {{main|Inlay (guitar)}} | |||

| Instruments with larger areas for the guitar top were introduced by Martin in an attempt to create greater volume levels. The popularity of the larger "]" body size amongst acoustic performers is related to the greater sound volume produced. | |||

| Inlays are visual elements set into the exterior frame of a guitar. The typical locations for inlay are on the fretboard, headstock, and around the soundhole (called a rosette on acoustic guitars). Inlays range from simple plastic dots on the fretboard to fantastic works of art covering the entire exterior surface of a guitar (front and back). Some guitar players (notably ] and ], bassist of rock group Limp Bizkit) put ]s in the fretboard as inlays to produce a unique lighting effect onstage. | |||

| Most electric guitar bodies are made of wood and include a plastic pickguard. Boards wide enough to use as a solid body are very expensive due to the worldwide depletion of hardwood stock since the 1970s, so the wood is rarely one solid piece. Most bodies are made from two pieces of wood with some of them including a seam running down the center line of the body. The most common woods used for electric guitar body construction include ], ], ], ], ], and ]. Many bodies consist of good-sounding, but inexpensive woods, like ash, with a "top", or thin layer of another, more attractive wood (such as maple with a natural "flame" pattern) glued to the top of the basic wood. Guitars constructed like this are often called "flame tops". The body is usually carved or routed to accept the other elements, such as the bridge, pickup, neck, and other electronic components. Most electrics have a polyurethane or ] lacquer finish. Other alternative materials to wood are used in guitar body construction. Some of these include carbon composites, plastic material, such as polycarbonate, and aluminum alloys. | |||

| Fretboard inlays are most commonly shaped like dots, diamond shapes, parallelograms, or large blocks in between the frets. Dots are usually inlaid into the upper edge of the fretboard in the same positions, small enough to be visible only to the player. Some manufacturers go beyond these simple shapes and use more creative designs such as lightning bolts or letters and numbers. The simpler inlays are often done in plastic on guitars of recent vintage, but many older, and newer, high-end instruments have inlays made of ], ], ], ] or any number of exotic materials. On some low-end guitars, they are just painted. Most high-end classical guitars have no inlays at all since a well trained player is expected to know his or her way around the instrument, however players will sometimes make indicators with a ], ], or a small piece of tape. | |||

| =====Bridge===== | |||

| The most popular fretboard inlay scheme involves single inlays on the 3rd, 5th, 7th, 9th, 15th, 17th, 19th, and 21st frets, and double inlays on the 12th, sometimes 7th, and (if present) 24th fret. Advantages of such scheme include its symmetry about the 12th fret and symmetry of every half (0-12 and 12-24) about the 7th and 19th frets. However, playing these frets, for example, on E string would yield notes E, G, A, B, C# that barely makes a complete ] by themselves. | |||

| The main purpose of the bridge on an acoustic guitar is to transfer the vibration from the strings to the soundboard, which vibrates the air inside of the guitar, thereby amplifying the sound produced by the strings. On all electric, acoustic and original guitars, the bridge holds the strings in place on the body. There are many varied bridge designs. There may be some mechanism for raising or lowering the bridge saddles to adjust the distance between the strings and the fretboard (]), or fine-tuning the intonation of the instrument. Some are spring-loaded and feature a "]", a removable arm that lets the player modulate the pitch by changing the tension on the strings. The whammy bar is sometimes also called a "tremolo bar". (The effect of rapidly changing pitch is properly called "vibrato". See ] for further discussion of this term.) Some bridges also allow for alternate tunings at the touch of a button. | |||