| Revision as of 04:19, 20 March 2005 edit24.128.51.52 (talk) →Movie inspired by Nash's life← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 21:59, 26 November 2024 edit undoAbsolutiva (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users2,551 edits Changing short description from "American mathematician and Nobel laureate (1928–2015)" to "American mathematician (1928–2015)"Tag: Shortdesc helper | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|American mathematician (1928–2015)}} | |||

| {{npov}} | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=November 2022}} | |||

| {{Infobox scientist | |||

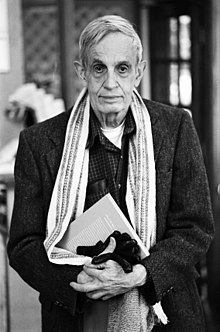

| | image = John Forbes Nash, Jr. by Peter Badge.jpg | |||

| | caption = Nash in the 2000s | |||

| | birth_date = {{birth date|1928|6|13}} | |||

| | birth_place = ], U.S. | |||

| | death_date = {{death date and age|2015|5|23|1928|6|13}} | |||

| | death_place = ], U.S. | |||

| | fields = {{plainlist| | |||

| * Mathematics | |||

| * ] | |||

| * Economics}} | |||

| | workplaces = {{plainlist| | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ]}} | |||

| | education = {{plainlist| | |||

| * ] (], ]) | |||

| * ] (PhD)}} | |||

| | thesis_title = Non-Cooperative Games | |||

| | thesis_url = https://www.princeton.edu/mudd/news/faq/topics/Non-Cooperative_Games_Nash.pdf | |||

| | thesis_year = 1950 | |||

| | doctoral_advisor = ] | |||

| | known_for = {{plainlist| | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * Ideal money}} | |||

| | awards = {{plainlist| | |||

| * ] (1978) | |||

| * ] (1994) | |||

| * ] (1996) | |||

| * ] (2015)}} | |||

| | spouse = {{ubl|{{marriage|]|1957|1963|end=div}}|{{marriage||2001|2015|end=their deaths}}}} | |||

| | children = 2 | |||

| }} | |||

| '''John Forbes Nash, Jr.''' (June 13, 1928 – May 23, 2015), known and published as '''John Nash''', was an American mathematician who made fundamental contributions to ], ], ], and ]s.<ref>{{cite news |author=Goode, Erica |title=John F. Nash Jr., Math Genius Defined by a 'Beautiful Mind,' Dies at 86 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/25/science/john-nash-a-beautiful-mind-subject-and-nobel-winner-dies-at-86.html |newspaper=] |date=May 24, 2015}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=John F. Nash Jr. and Louis Nirenberg share the Abel Prize |url=http://www.abelprize.no/nyheter/vis.html?tid=63589 |publisher=] |date=March 25, 2015 |access-date=May 27, 2015 |archive-date=June 16, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190616214625/https://www.abelprize.no/nyheter/vis.html?tid=63589 }}</ref> Nash and fellow game theorists ] and ] were awarded the 1994 ]. In 2015, he and ] were awarded the ] for their contributions to the field of partial differential equations. | |||

| As a graduate student in the ], Nash introduced a number of concepts (including ] and the ]) which are now considered central to game theory and its applications in various sciences. In the 1950s, Nash discovered and proved the ] by solving a system of nonlinear partial differential equations arising in ]. This work, also introducing a preliminary form of the ], was later recognized by the ] with the ]. ] and Nash found, with separate methods, a body of results paving the way for a systematic understanding of ] and ]s. Their De Giorgi–Nash theorem on the smoothness of solutions of such equations resolved ] on regularity in the ], which had been a well-known ] for almost sixty years. | |||

| ] | |||

| '''John Forbes Nash Jr.''' (born ], ]) is an ] ] who works in ] and ]. He shared the ] ] with two other game theorists, ] and ]. | |||

| In 1959, Nash began showing clear signs of mental illness, and spent several years at ]s being treated for ]. After 1970, his condition slowly improved, allowing him to return to academic work by the mid-1980s.<ref name="Nasar1994" /> | |||

| After a promising start to his mathematical career, Nash began to suffer from ] around the age of 29, an illness from which he recovered some thirty years later. | |||

| Nash's life was the subject of ]'s 1998 biographical book '']'', and his struggles with his illness and his recovery became the basis for a ] directed by ], in which Nash was portrayed by ].<ref name="Oscar race scrutinizes">{{cite news |title=Oscar race scrutinizes movies based on true stories |work=] |date=March 6, 2002 |url=http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/life/movies/oscar2002/2002-03-06-true-stories.htm |access-date=January 22, 2008}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/life/movies/oscar2002/2002-03-24-winners.htm |title=Academy Award Winners |work=] |access-date=August 30, 2008 |date=March 25, 2002}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |last=Yuhas |first=Daisy |title=Throughout History, Defining Schizophrenia Has Remained A Challenge (Timeline) |url=http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/throughout-history-defining-schizophrenia-has-remained-challenge/ |work=] |date=March 2013 |access-date=March 2, 2013}}</ref> | |||

| ==Education== | |||

| == Early life and education == | |||

| From June ]-June ] Nash studied at the ] in ] (now ]), intending to become an engineer like his father. Instead, he developed a deep love for ] and what became a lifelong interest in subjects such as ], ], ] and ]. | |||

| John Forbes Nash Jr. was born on June 13, 1928, in ]. His father and namesake, John Forbes Nash Sr., was an ] for the ]. His mother, Margaret Virginia (née Martin) Nash, had been a schoolteacher before she was married. He was baptized in the ].{{sfnm|1a1=Nasar|1y=1998|1loc=Chapter 1}} He had a younger sister, Martha (born November 16, 1930).<ref name="Nash1995">{{cite conference|last1=Nash|first1=John F. Jr.|year=1995|url=https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economic-sciences/laureates/1994/nash-bio.html|title=John F. Nash Jr. – Biographical|book-title=The Nobel Prizes 1994: Presentations, Biographies & Lectures|editor-first1=Tore|editor-last1=Frängsmyr|publisher=]|location=Stockholm|editor-link1=Tore Frängsmyr|isbn=978-91-85848-24-9|pages=275–279}}</ref> | |||

| Nash attended kindergarten and public school, and he learned from books provided by his parents and grandparents.<ref name="Nash1995" /> Nash's parents pursued opportunities to supplement their son's education, and arranged for him to take advanced mathematics courses at nearby Bluefield College (now ]) during his final year of high school. He attended ] (which later became Carnegie Mellon University) through a full benefit of the George Westinghouse Scholarship, initially majoring in ]. He switched to a ] major and eventually, at the advice of his teacher ], to mathematics. After graduating in 1948, with both a ] and ] in mathematics, Nash accepted a fellowship to ], where he pursued further ] in mathematics and sciences.<ref name="Nash1995" /> | |||

| He loved solving problems. At Carnegie he became interested in the 'negotiation problem', which ] had left unsolved in his book ''The Theory of Games and Economic Behavior'' (]), and participated in the ] group there. His theory, now called the ], is a corollary of the '']'' stated earlier by John Von Neumann in ]. | |||

| Nash's adviser and former Carnegie professor ] wrote a letter of recommendation for Nash's entrance to Princeton stating, "He is a mathematical genius."<ref>{{cite web |title=Nash recommendation letter |url=https://webspace.princeton.edu/users/mudd/Digitization/AC105/AC105_Nash_John_Forbes_1950.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170607041209/https://webspace.princeton.edu/users/mudd/Digitization/AC105/AC105_Nash_John_Forbes_1950.pdf |archive-date=June 7, 2017 |access-date=June 5, 2015 |page=23}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |editor1-first=Harold W. |editor1-last=Kuhn |editor2-first=Sylvia |editor2-last=Nasar |editor-link=Sylvia Nasar |url=http://press.princeton.edu/chapters/i7238.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070101170703/http://press.princeton.edu/chapters/i7238.pdf |archive-date=2007-01-01 |url-status=live |title=The Essential John Nash |publisher=] |pages=Introduction, xi |access-date=April 17, 2008}}</ref> Nash was also accepted at ]. However, the chairman of the mathematics department at Princeton, ], offered him the ]<!-- NOTE: not John F. Kennedy--> fellowship, convincing Nash that Princeton valued him more.{{sfnm|1a1=Nasar|1y=1998|1loc=Chapter 2}} Further, he considered Princeton more favorably because of its proximity to his family in Bluefield.<ref name="Nash1995" /> At Princeton, he began work on his equilibrium theory, later known as the ].<ref>Nasar (2002), pp. xvi–xix.</ref> | |||

| From Pittsburgh he went to ] where he worked on his equilibrium theory. He received a ] in ] with a dissertation on non-cooperative games. The thesis, which was written under the supervision of ], contained the definition and properties of what would later be called the ]. His studies on this subject led to three articles: | |||

| * 'Equilibrium Points in N-person Games', published in the '']'' (USA) (]); | |||

| * ''The Bargaining Problem'' (April ]) in ''Econometrica'', and | |||

| * ''Two-person Cooperative Games'' (January ]), also in ''Econometrica''. | |||

| == Research contributions == | |||

| ==Personal life== | |||

| ] conference in ], Germany]] | |||

| Nash did not publish extensively, although many of his papers are considered landmarks in their fields.<ref>{{cite journal | first = John | last = Milnor | author-link = John Milnor |year = 1998 | title = John Nash and 'A Beautiful Mind' | url = https://www.ams.org/notices/199810/milnor.pdf| journal = ] | volume = 25 | issue = 10|pages = 1329–1332 }}</ref> As a graduate student at Princeton, he made foundational contributions to ] and ]. As a postdoctoral fellow at ], Nash turned to ]. Although the results of Nash's work on differential geometry are phrased in a geometrical language, the work is almost entirely to do with the ] of ].<ref name="steele">{{cite journal|title=1999 Steele Prizes|journal=]|date=April 1999|pages=457–462|volume=46|issue=4|url=https://www.ams.org/notices/199904/comm-steele-prz.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20000829221437/http://www.ams.org/notices/199904/comm-steele-prz.pdf |archive-date=2000-08-29 |url-status=live}}</ref> After proving his two ]s, Nash turned to research dealing directly with partial differential equations, where he discovered and proved the De Giorgi–Nash theorem, thereby resolving one form of ]. | |||

| John Nash was born in the small ]n town of ], the son of John Nash Sr., an electrical engineer, and Virginia Martin, a teacher. By the time he was about twelve years old he was showing great interest in carrying out scientific experiments in his room at home. | |||

| In 2011, the ] declassified letters written by Nash in the 1950s, in which he had proposed a new ]–decryption machine.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.nsa.gov/Press-Room/Press-Releases-Statements/Press-Release-View/Article/1630570/national-cryptologic-museum-opens-new-exhibit-on-dr-john-nash/ |publisher=] |title=2012 Press Release – National Cryptologic Museum Opens New Exhibit on Dr. John Nash |access-date=July 30, 2022}}</ref> The letters show that Nash had anticipated many concepts of modern ], which are based on ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://agtb.wordpress.com/2012/02/17/john-nashs-letter-to-the-nsa/ |title=John Nash's Letter to the NSA; Turing's Invisible Hand |access-date=February 25, 2012|date=February 17, 2012 }}</ref> | |||

| Martha, his sister, seems to have been a remarkably normal child while Johnny seemed different from other children. She wrote later in life, "Johnny was always different. knew he was different. And they knew he was bright. He always wanted to do things his way. Mother insisted I do things for him, that I include him in my friendships. ... but I wasn't too keen on showing off my somewhat odd brother". | |||

| === Game theory === | |||

| At MIT, he met ], a math student from ], whom he married in February ]. Their son, ] (b. 1959), remained nameless for a year because Alicia, having just committed Nash to a mental hospital, felt that he should have a say in what to name the baby. John became a mathematician, but, like his father, he was diagnosed a paranoid schizophrenic. Nash had another son, John David (b. ], ]), by Eleanor Stier, but refused to have anything to do with them. Sylvia Nasar, Nash's biographer, cites evidence that Nash was bisexual. However, John and Alicia denied such on ] in ]. | |||

| Nash earned a PhD in 1950 with a 28-page dissertation on ].<ref name="JohnNash_PhD">{{cite web |last1=Nash |first1=John F. |author-link=John Forbes Nash Jr. |title=Non-Cooperative Games |work=PhD thesis |publisher=Princeton University |date=May 1950 |url=https://www.princeton.edu/mudd/news/faq/topics/Non-Cooperative_Games_Nash.pdf |access-date=May 24, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150420144847/http://www.princeton.edu/mudd/news/faq/topics/Non-Cooperative_Games_Nash.pdf |archive-date=April 20, 2015 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |first=Martin J. |last=Osborne |date=2004 |title=An Introduction to Game Theory |url=https://archive.org/details/introductiontoga00osbo |url-access=limited |publisher=] |location=Oxford, England |page= |isbn=0-19-512895-8}}</ref> The thesis, written under the supervision of doctoral advisor ], contained the definition and properties of the ], a crucial concept in non-cooperative games. A version of his thesis was published a year later in the ].{{sfnm|1a1=Nash|1y=1951}} In the early 1950s, Nash carried out research on a number of related concepts in game theory, including the theory of ].{{sfnm|1a1=Nash|1y=1950a|2a1=Nash|2y=1950b|3a1=Nash|3y=1953}} For his work, Nash was one of the recipients of the ] in 1994. | |||

| === Real algebraic geometry === | |||

| Although she divorced him in ], Alicia took him back in ]. According to Sylvia Nasar's biography of Nash, Alicia referred to him as her "boarder," and they lived "like two distantly related individuals under one roof" until he won the ] in ], when they renewed their relationship. They remarried on ], ]. | |||

| In 1949, while still a graduate student, Nash found a new result in the mathematical field of ].{{sfnm|1a1=Nasar|1y=1998|1loc=Chapter 15}} He announced his theorem in a contributed paper at the ] in 1950, although he had not yet worked out the details of its proof.{{sfnm|1a1=Nash|1y=1952a}} Nash's theorem was finalized by October 1951, when Nash submitted his work to the ].{{sfnm|1a1=Nash|1y=1952b}} It had been well-known since the 1930s that every ] ] is ] to the ] of some collection of ]s on ]. In his work, Nash proved that those smooth functions can be taken to be ]s.<ref name="bochnak">{{cite book|mr=1659509|last1=Bochnak|first1=Jacek|last2=Coste|first2=Michel|last3=Roy|first3=Marie-Françoise|title=Real algebraic geometry|edition=Translated and revised from 1987 French original|series=]|volume=36|publisher=]|location=Berlin|year=1998|isbn=3-540-64663-9|zbl=0912.14023|doi=10.1007/978-3-662-03718-8|s2cid=118839789 |author-link3=Marie-Françoise Roy}}</ref> This was widely regarded as a surprising result,{{sfnm|1a1=Nasar|1y=1998|1loc=Chapter 15}} since the class of smooth functions and smooth manifolds is usually far more flexible than the class of polynomials. Nash's proof introduced the concepts now known as ] and ], which have since been widely studied in real algebraic geometry.<ref name="bochnak" /><ref>{{cite book|mr=0904479|last1=Shiota|first1=Masahiro|title=Nash Manifolds |series=]|volume=1269|publisher=]|location=Berlin|year=1987|isbn=3-540-18102-4|doi=10.1007/BFb0078571|zbl=0629.58002}}</ref> Nash's theorem itself was famously applied by ] and ] to the study of ]s, by combining Nash's polynomial approximation together with ].<ref>{{cite journal|mr=0176482|last1=Artin|first1=M.|last2=Mazur|first2=B.|title=On periodic points|journal=]|series=Second Series|volume=81|year=1965|pages=82–99|issue=1|doi=10.2307/1970384|jstor=1970384 |zbl=0127.13401|author-link1=Michael Artin|author-link2=Barry Mazur}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|first1=Mikhaïl|last1=Gromov|url=https://www.ihes.fr/~gromov/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/1024.pdf|title=On the entropy of holomorphic maps|journal=]|series=2e Série|volume=49|year=2003|issue=3–4|pages=217–235|mr=2026895|zbl=1080.37051|author-link1=Mikhael Gromov (mathematician)}}</ref> | |||

| === |

===Differential geometry=== | ||

| During his postdoctoral position at ], Nash was eager to find high-profile mathematical problems to study.{{sfnm|1a1=Nasar|1y=1998|1loc=Chapter 20}} From ], a ], he learned about the conjecture that any ] is ] to a ] of ]. Nash's results proving the conjecture are now known as the ]s, the second of which ] has called "one of the main achievements of mathematics of the twentieth century".<ref name="Nash2015">{{cite conference|mr=3470099|book-title=Open problems in mathematics|editor-first1=John Forbes Jr.|editor-last1=Nash|editor-first2=Michael Th.|editor-last2=Rassias|publisher=]|year=2016|isbn=978-3-319-32160-8|doi=10.1007/978-3-319-32162-2|first1=Misha|last1=Gromov|author-link1=Mikhael Gromov (mathematician)|title=Introduction John Nash: theorems and ideas|arxiv=1506.05408}}</ref> | |||

| Nash's first embedding theorem was found in 1953.{{sfnm|1a1=Nasar|1y=1998|1loc=Chapter 20}} He found that any Riemannian manifold can be isometrically embedded in a Euclidean space by a ] mapping.{{sfnm|1a1=Nash|1y=1954}} Nash's construction allows the ] of the embedding to be very small, with the effect that in many cases it is logically impossible that a highly-differentiable isometric embedding exists. (Based on Nash's techniques, ] soon found even smaller codimensions, with the improved result often known as the ''Nash–Kuiper theorem''.) As such, Nash's embeddings are limited to the setting of low differentiability. For this reason, Nash's result is somewhat outside the mainstream in the field of ], where high differentiability is significant in much of the usual analysis.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Eliashberg|first1=Y.|last2=Mishachev|first2=N.|title=Introduction to the h-principle|series=]|volume=48|publisher=]|location=Providence, RI|year=2002|isbn=0-8218-3227-1|mr=1909245|author-link1=Yakov Eliashberg|doi=10.1090/gsm/048}}</ref><ref name="pdr">{{cite book|last1=Gromov|first1=Mikhael|title=Partial differential relations|series=Ergebnisse der Mathematik und ihrer Grenzgebiete (3)|volume=9|publisher=]|location=Berlin|year=1986|isbn=3-540-12177-3|mr=0864505|author-link1=Mikhael Gromov (mathematician)|doi=10.1007/978-3-662-02267-2}}</ref> | |||

| In ], Nash began to show the first signs of his mental illness. He became paranoid and was admitted into the ], April-May ], where he was diagnosed with '] ]'. After a problematic stay in ] and ], Nash returned to Princeton in ]. He remained in and out of mental hospitals until ], undergoing various treatments including ] (a.k.a. ]) ] ]. | |||

| However, the logic of Nash's work has been found to be useful in many other contexts in ]. Starting with work of ] and László Székelyhidi, the ideas of Nash's proof were applied for various constructions of turbulent solutions of the ] in ].<ref>{{cite journal|last1=De Lellis|first1=Camillo|last2=Székelyhidi|first2=László Jr.|title=Dissipative continuous Euler flows|journal=]|volume=193|year=2013|issue=2|pages=377–407|mr=3090182|author-link1=Camillo De Lellis|doi=10.1007/s00222-012-0429-9| arxiv=1202.1751 | bibcode=2013InMat.193..377D | s2cid=2693636 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Isett|first1=Philip|title=A proof of Onsager's conjecture|journal=]|series=Second Series|year=2018|volume=188|issue=3|pages=871–963|mr=3866888|doi=10.4007/annals.2018.188.3.4|s2cid=119267892|url=https://authors.library.caltech.edu/87369/|arxiv=1608.08301|access-date=October 11, 2022|archive-date=October 11, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221011050610/https://authors.library.caltech.edu/87369/|url-status=dead}}</ref> In the 1970s, ] developed Nash's ideas into the general framework of ''convex integration'',<ref name="pdr" /> which has been (among other uses) applied by ] and ] to construct counterexamples to generalized forms of ] in the ].<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Müller|first1=S.|last2=Šverák|first2=V.|title=Convex integration for Lipschitz mappings and counterexamples to regularity|journal=]|series=Second Series|volume=157|year=2003|issue=3|pages=715–742|mr=1983780|author-link1=Stefan Müller (mathematician)|author-link2=Vladimir Šverák|doi=10.4007/annals.2003.157.715| s2cid=55855605 |doi-access=free|arxiv=math/0402287}}</ref> | |||

| Some of his treatments may have worsened his condition because his doctors did not realize the centrality of work and community to curing mental illness, and the most successful "treatment" seems to have been administrative decisions at Princeton's mathematics department and computer center to allow Nash to use university facilities for his researches during this period, although the researches were initially delusional. | |||

| Nash found the construction of smoothly differentiable isometric embeddings to be unexpectedly difficult.{{sfnm|1a1=Nasar|1y=1998|1loc=Chapter 20}} However, after around a year and a half of intensive work, his efforts succeeded, thereby proving the second Nash embedding theorem.{{sfnm|1a1=Nash|1y=1956}} The ideas involved in proving this second theorem are largely separate from those used in proving the first. The fundamental aspect of the proof is an ] for isometric embeddings. The usual formulations of the implicit function theorem are inapplicable, for technical reasons related to the ''loss of regularity'' phenomena. Nash's resolution of this issue, given by deforming an isometric embedding by an ] along which extra regularity is continually injected, is regarded as a fundamentally novel technique in ].<ref name="hamilton82">{{cite journal|first=Richard S.|last=Hamilton|mr=0656198|title=The inverse function theorem of Nash and Moser|journal=] |series=New Series |volume=7|year=1982|issue=1|pages=65–222|doi-access=free|doi=10.1090/s0273-0979-1982-15004-2|zbl=0499.58003|author-link1=Richard S. Hamilton}}</ref> Nash's paper was awarded the ] in 1999, where his "most original idea" in the resolution of the ''loss of regularity'' issue was cited as "one of the great achievements in mathematical analysis in this century".<ref name="steele" /> According to Gromov:<ref name="Nash2015" /> | |||

| In student and on-campus legend, Nash became "The Phantom of Fine Hall" (Fine Hall is Princeton's mathematics center), a shadowy figure who would scribble arcane equations on blackboards in the middle of the night. The legend appears in a work of fiction based on Princeton life, "The Mind-Body Problem", by Rebecca Goldstein. | |||

| {{blockquote|You must be a novice in analysis or a genius like Nash to believe anything like that can be ever true and/or to have a single nontrivial application.}} | |||

| Due to ]'s extension of Nash's ideas for application to other problems (notably in ]), the resulting implicit function theorem is known as the ]. It has been extended and generalized by a number of other authors, among them Gromov, ], ], ], and ].<ref name="pdr" /><ref name="hamilton82" /> Nash himself analyzed the problem in the context of ]s.{{sfnm|1a1=Nash|1y=1966}} Schwartz later commented that Nash's ideas were "not just novel, but very mysterious," and that it was very hard to "get to the bottom of it."{{sfnm|1a1=Nasar|1y=1998|1loc=Chapter 20}} According to Gromov:<ref name="Nash2015" /> | |||

| However, encouraged by his wife Alicia, Nash persisted in working in a communitarian setting where his eccentricities were unremarked and developed, among other interests, an interest in the calculation of exact values of large numbers, researches which drove him to Princeton's Information Centers, where he developed computer programs (of high quality) for his work. Here he had more contact with Princetonians and also, in the late 1980s, began to use electronic mail to gradually link with working mathematicians who realized that he was "John Nash" and his new work had value. | |||

| {{blockquote|Nash was solving classical mathematical problems, difficult problems, something that nobody else was able to do, not even to imagine how to do it. ... what Nash discovered in the course of his constructions of isometric embeddings is far from 'classical' – it is something that brings about a dramatic alteration of our understanding of the basic logic of analysis and differential geometry. Judging from the classical perspective, what Nash has achieved in his papers is as impossible as the story of his life ... is work on isometric immersions ... opened a new world of mathematics that stretches in front of our eyes in yet unknown directions and still waits to be explored.}} | |||

| ===Partial differential equations=== | |||

| They formed part of the nucleus of a group that contacted the Nobel committee and was able to vouch for Nash's ability to receive the award in recognition of his early work. | |||

| While spending time at the ] in New York City, ] informed Nash of a well-known conjecture in the field of ]s.{{sfnm|1a1=Nasar|1y=1998|1loc=Chapter 30}} In 1938, ] had proved a fundamental ] result for functions of two independent variables, but analogous results for functions of more than two variables had proved elusive. After extensive discussions with Nirenberg and ], Nash was able to extend Morrey's results, not only to functions of more than two variables, but also to the context of ]s.{{sfnm|1a1=Nash|1y=1957|2a1=Nash|2y=1958}} In his work, as in Morrey's, uniform control over the continuity of the solutions to such equations is achieved, without assuming any level of differentiability on the coefficients of the equation. The ] was a particular result found in the course of his work (the proof of which Nash attributed to ]), which has been found useful in other contexts.<ref name="davies">{{cite book|mr=0990239|last1=Davies|first1=E. B.|title=Heat kernels and spectral theory|series=Cambridge Tracts in Mathematics|volume=92|publisher=]|location=Cambridge|year=1989|isbn=0-521-36136-2|doi=10.1017/CBO9780511566158|author-link1=E. Brian Davies}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|mr=2569498|last1=Grigor'yan|first1=Alexander|title=Heat kernel and analysis on manifolds|series=AMS/IP Studies in Advanced Mathematics|volume=47|publisher=]|location=Providence, RI|year=2009|isbn=978-0-8218-4935-4|doi=10.1090/amsip/047}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|mr=1840042|last1=Kigami|first1=Jun|title=Analysis on fractals|series=Cambridge Tracts in Mathematics|volume=143|publisher=]|location=Cambridge|year=2001|isbn=0-521-79321-1}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|mr=1817225 |last1=Lieb|first1=Elliott H.|last2=Loss|first2=Michael|title=Analysis|edition=Second edition of 1997 original|series=]|volume=14|publisher=]|location=Providence, RI|year=2001|isbn=0-8218-2783-9|author-link1=Elliott Lieb|author-link2=Michael Loss}}</ref> | |||

| Soon after, Nash learned from ], recently returned from Italy, that the then-unknown ] had found nearly identical results for elliptic partial differential equations.{{sfnm|1a1=Nasar|1y=1998|1loc=Chapter 30}} De Giorgi and Nash's methods had little to do with one another, although Nash's were somewhat more powerful in applying to both elliptic and parabolic equations. A few years later, inspired by De Giorgi's method, ] found a different approach to the same results, and the resulting body of work is now known as the De Giorgi–Nash theorem or the De Giorgi–Nash–Moser theory (which is distinct from the ]). De Giorgi and Moser's methods became particularly influential over the next several years, through their developments in the works of ], ], and ], among others.<ref>{{cite book|mr=1814364|last1=Gilbarg|first1=David|last2=Trudinger|first2=Neil S.|title=Elliptic partial differential equations of second order|edition=Reprint of the second|series=Classics in Mathematics|publisher=]|location=Berlin|year=2001|isbn=3-540-41160-7|doi=10.1007/978-3-642-61798-0|author-link1=David Gilbarg|author-link2=Neil Trudinger}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|mr=1465184|last1=Lieberman|first1=Gary M.|title=Second order parabolic differential equations|publisher=]|location=River Edge, NJ|year=1996|isbn=981-02-2883-X|doi=10.1142/3302}}</ref> Their work, based primarily on the judicious choice of ]s in the ] of partial differential equations, is in strong contrast to Nash's work, which is based on analysis of the ]. Nash's approach to the De Giorgi–Nash theory was later revisited by ] and ], initiating the re-derivation and extension of the results originally obtained from De Giorgi and Moser's techniques.<ref name="davies" /><ref>{{cite journal|mr=0855753|last1=Fabes|first1=E. B.|last2=Stroock|first2=D. W.|title=A new proof of Moser's parabolic Harnack inequality using the old ideas of Nash|journal=]|volume=96|year=1986|issue=4|pages=327–338|doi=10.1007/BF00251802 |bibcode=1986ArRMA..96..327F |s2cid=189774501 |author-link2=Daniel Stroock}}</ref> | |||

| The 1990s brought a return of his ], and Nash has taken care to manage the symptoms of his mental illness. He is still hoping to score substantial scientific results. His recent work involves some very interesting ventures in advanced game theory including partial agency which show that as in early career, he prefers to select his own path and problems. | |||

| From the fact that minimizers to many functionals in the ] solve elliptic partial differential equations, ] (on the smoothness of these minimizers), conjectured almost sixty years prior, was directly amenable to the De Giorgi–Nash theory. Nash received instant recognition for his work, with ] describing it as a "stroke of genius".{{sfnm|1a1=Nasar|1y=1998|1loc=Chapter 30}} Nash would later speculate that had it not been for De Giorgi's simultaneous discovery, he would have been a recipient of the prestigious ] in 1958.<ref name="Nash1995" /> Although the medal committee's reasoning is not fully known, and was not purely based on questions of mathematical merit,{{sfnm|1a1=Nasar|1y=1998|1loc=Chapter 31}} archival research has shown that Nash placed third in the committee's vote for the medal, after the two mathematicians (] and ]) who were awarded the medal that year.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Barany|first1=Michael|title=The Fields Medal should return to its roots|journal=]|volume=553|date=January 18, 2018|issue=7688 |pages=271–273|doi=10.1038/d41586-018-00513-8|bibcode=2018Natur.553..271B |doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| ==Career== | |||

| == Mental illness == | |||

| In the summer of ] he worked at the ] in ], where he returned for shorter periods in ] and ]. From ]-] he taught calculus courses at Princeton, studied and managed to stay out of military service. During this time, he proved the ], an important result in ] about ]s. | |||

| Although Nash's ] first began to manifest in the form of ], his wife later described his behavior as erratic. Nash thought that all men who wore red ties were part of a ] conspiracy against him. He mailed letters to embassies in Washington, D.C., declaring that they were establishing a government.<ref name="Nasar1994" /><ref>], p. 251.</ref> Nash's psychological issues crossed into his professional life when he gave an ] lecture at ] in early 1959. Originally intended to present proof of the ], the lecture was incomprehensible. Colleagues in the audience immediately realized that something was wrong.<ref>{{cite book |first=Karl |last=Sabbagh |title=Dr. Riemann's Zeros |publisher=] |location=London, England |date=2003 |isbn=1-84354-100-9 |pages= |url=https://archive.org/details/drriemannszeros0000sabb/page/87 }}</ref> | |||

| In April 1959, Nash was admitted to ] for one month. Based on his paranoid, persecutory ], ], and increasing ], he was diagnosed with ].<ref>{{cite web| url=http://www.brown.edu/Courses/BI_278/Other/Clerkship/Didactics/Readings/Schizophrenia.pdf | title=Brown University Didactic Readings: DSM-IV Schizophrenia (DSM-IV-TR #295.1–295.3, 295.90) | publisher=] | location=Providence, Rhode Island|access-date=June 1, 2015 | pages=1–11}}</ref><ref name="Nasar ABM">], p. 32.</ref> In 1961, Nash was admitted to the ].<ref>{{MacTutor|id=Nash}}</ref> Over the next nine years, he spent intervals of time in ]s, where he received both ] ] and ].<ref name="Nasar ABM" /><ref name="Roger Ebert's Movie">{{cite book |first=Roger |last=Ebert|author-link=Roger Ebert|title=Roger Ebert's Movie Yearbook 2003 |publisher=] |date=2002 |url=https://archive.org/details/rogerebertsmovie00roge_6 |url-access=registration |access-date=July 10, 2008 |isbn=978-0-7407-2691-0}}</ref> | |||

| He was at MIT from 1951 until the spring of 1959, which included a ] year at the ] in Princeton. | |||

| Although he sometimes took prescribed medication, Nash later wrote that he did so only under pressure. According to Nash, the film ''A Beautiful Mind'' inaccurately implied he was taking ]s. He attributed the depiction to the screenwriter who was worried about the film encouraging people with mental illness to stop taking their medication.<ref>{{cite web|first=Marika|last=Greihsel|url=https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economic-sciences/laureates/1994/nash-interview.html|title=John F. Nash Jr. – Interview|website=Nobel Foundation|date=September 1, 2004|access-date=November 3, 2018}}</ref> | |||

| He held a research position at ] from ]-], but there was a 30-year gap between then and ] which was void of any scientific publications. | |||

| Nash did not take any medication after 1970, nor was he committed to a hospital ever again.<ref>{{cite web|first=John Forbes|last=Nash|url=https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/nash/sfeature/sf_nash_11.html|title=PBS Interview: Medication|publisher=]|year=2002|access-date=September 1, 2017|archive-date=June 4, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160604221411/http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/nash/sfeature/sf_nash_11.html}}</ref> Nash recovered gradually.<ref>Nash, John {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160606080035/http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/nash/sfeature/sf_nash_14.html |date=June 6, 2016 }} 2002.</ref> Encouraged by his then former wife, Lardé, Nash lived at home and spent his time in the Princeton mathematics department where his eccentricities were accepted even when his mental condition was poor. Lardé credits his ] to maintaining "a quiet life" with ].<ref name="Nasar1994" /> | |||

| He currently holds an appointment in mathematics at Princeton. While cautious with people he does not know, insiders cite a dry sense of humor. | |||

| Nash dated the start of what he termed "mental disturbances" to the early months of 1959, when his wife was pregnant. He described a process of change "from scientific rationality of thinking into the delusional thinking characteristic of persons who are psychiatrically diagnosed as 'schizophrenic' or 'paranoid schizophrenic{{'"}}.<ref name="Nash1995" /> For Nash, this included seeing himself as a messenger or having a special function of some kind, of having supporters and opponents and hidden schemers, along with a feeling of being persecuted and searching for signs representing divine revelation.<ref>Nash, John {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161001215421/http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/nash/sfeature/sf_nash_12.html |date=October 1, 2016 }}. 2002.</ref> During his psychotic phase, Nash also ] as "Johann von Nassau".{{sfnm|1a1=Nasar|1y=1998|1loc=Chapter 39}} Nash suggested his delusional thinking was related to his unhappiness, his desire to be recognized, and his characteristic way of thinking, saying, "I wouldn't have had good scientific ideas if I had thought more normally." He also said, "If I felt completely pressureless I don't think I would have gone in this pattern".<ref>Nash, John {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170310042743/http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/nash/sfeature/sf_nash_05.html |date=March 10, 2017 }} 2002.</ref> | |||

| The contribution of his wife Alicia was quite significant. She supported him during his delusional phase and saw how membership, no matter how humble, in the Princeton community helped Nash get better. Alicia also worked, rather courageously, as a computer programmer in male-dominated companies to support herself, John, and their son. | |||

| Nash reported that he started hearing voices in 1964, then later engaged in a process of consciously rejecting them.<ref>Nash, John {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120309213637/http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/nash/sfeature/sf_nash_06.html |date=March 9, 2012 }}. 2002.</ref> He only renounced his "dream-like delusional hypotheses" after a prolonged period of involuntary commitment in mental hospitals—"enforced rationality". Upon doing so, he was temporarily able to return to productive work as a mathematician. By the late 1960s, he relapsed.<ref>Nash, John {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160605170425/http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/nash/sfeature/sf_nash_13.html |date=June 5, 2016 }}. 2002.</ref> Eventually, he "intellectually rejected" his "{{not a typo|delusionally}} influenced" and "politically oriented" thinking as a waste of effort.<ref name="Nash1995" /> In 1995, he said that he did not realize his full potential due to nearly 30 years of mental illness.<ref name=Experiences>Nash, John {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161207174723/http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/nash/sfeature/sf_nash_08.html |date=December 7, 2016 }}. PBS Interview, 2002.</ref> | |||

| ===Recognition=== | |||

| In ] he was awarded the ] for his invention of non-cooperative equilibriums, now called ]. | |||

| Nash wrote in 1994: | |||

| In 1994 he received the ] as a result of his game theory work at Princeton as a graduate student. | |||

| {{blockquote|I spent times of the order of five to eight months in hospitals in New Jersey, always on an involuntary basis and always attempting a legal argument for release. And it did happen that when I had been long enough hospitalized that I would finally renounce my delusional hypotheses and revert to thinking of myself as a human of more conventional circumstances and return to mathematical research. In these interludes of, as it were, enforced rationality, I did succeed in doing some respectable mathematical research. Thus there came about the research for "Le problème de Cauchy pour les équations différentielles d'un fluide général"; the idea that Prof. ] called "the Nash blowing-up transformation"; and those of "Arc Structure of Singularities" and "Analyticity of Solutions of Implicit Function Problems with Analytic Data". | |||

| But after my return to the dream-like delusional hypotheses in the later 60s I became a person of {{not a typo|delusionally}} influenced thinking but of relatively moderate behavior and thus tended to avoid hospitalization and the direct attention of psychiatrists. | |||

| Between ] and ] John Nash published a total of 23 scientific studies. | |||

| Thus further time passed. Then gradually I began to intellectually reject some of the {{not a typo|delusionally}} influenced lines of thinking which had been characteristic of my orientation. This began, most recognizably, with the rejection of politically oriented thinking as essentially a hopeless waste of intellectual effort. So at the present time I seem to be thinking rationally again in the style that is characteristic of scientists.<ref name="Nash1995" />}} | |||

| {{npov}} | |||

| == Recognition and later career == | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| '''John Forbes Nash Jr.''' (born ], ]) is an ] ] who works in ] and ]. He shared the ] ] with two other game theorists, ] and ]. | |||

| In 1978, Nash was awarded the ] for his discovery of non-cooperative equilibria, now called Nash Equilibria. He won the ] in 1999. | |||

| In 1994, he received the ] (along with ] and ]) for his ] work as a Princeton graduate student.<ref>Nasar (2002), p. xiii.</ref> In the late 1980s, Nash had begun to use email to gradually link with working mathematicians who realized that he was {{em|the}} John Nash and that his new work had value. They formed part of the nucleus of a group that contacted the ]'s Nobel award committee and were able to vouch for Nash's mental health and ability to receive the award.<ref>{{cite journal|title=The Work of John Nash in Game Theory|journal=Nobel Seminar|date=December 8, 1994|url=https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economic-sciences/laureates/1994/nash-lecture.pdf|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130810134711/https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economic-sciences/laureates/1994/nash-lecture.pdf|archive-date=August 10, 2013|access-date=May 29, 2015}}</ref> | |||

| After a promising start to his mathematical career, Nash began to suffer from ] around the age of 29, an illness from which he recovered some thirty years later. | |||

| Nash's later work involved ventures in advanced game theory, including partial agency, which show that, as in his early career, he preferred to select his own path and problems. Between 1945 and 1996, he published 23 scientific papers. | |||

| ==Education== | |||

| Nash has suggested hypotheses on mental illness. He has compared not thinking in an acceptable manner, or being "insane" and not fitting into a usual social function, to being "on ]" from an economic point of view. He advanced views in ] about the potential benefits of apparently nonstandard behaviors or roles.<ref>{{cite web |last=Neubauer |first=David |date=June 1, 2007 |url=http://health.yahoo.com/experts/depression/8207/john-nash-and-a-beautiful-mind-on-strike/ |title=John Nash and a Beautiful Mind on Strike |website=Yahoo! Health |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080421192944/http://health.yahoo.com/experts/depression/8207/john-nash-and-a-beautiful-mind-on-strike/ |archive-date=April 21, 2008}}</ref> | |||

| From June ]-June ] Nash studied at the ] in ] (now ]), intending to become an engineer like his father. Instead, he developed a deep love for ] and what became a lifelong interest in subjects such as ], ], ] and ]. | |||

| Nash criticized ] of ] which allowed for a ] to implement ].<ref name=":0" /> He proposed a standard of "Ideal Money" pegged to an "industrial consumption ]" which was more stable than "bad money." He noted that his thinking on money and the function of ] paralleled that of economist ].{{sfnm|1a1=Nash|1y=2002a}}<ref name=":0">Zuckerman, Julia (April 27, 2005) . ''The Brown Daily Herald''. By JULIA ZUCKERMAN Wednesday, April 27, 2005</ref> | |||

| He loved solving problems. At Carnegie he became interested in the 'negotiation problem', which ] had left unsolved in his book ''The Theory of Games and Economic Behavior'' (]), and participated in the ] group there. His theory, now called the ], is a corollary of the '']'' stated earlier by John Von Neumann in ]. | |||

| Nash received an honorary degree, Doctor of Science and Technology, from ] in 1999, an honorary degree in economics from the ] in 2003,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://ricerca.repubblica.it/repubblica/archivio/repubblica/2003/03/19/napoli-laurea-nash-il-genio-dei-numeri.html |title=Napoli, laurea a Nash il 'genio dei numeri' |date=March 19, 2003 |publisher=la Repubblica.it |first=Patrizia |last=Capua |language=it}}</ref> an honorary doctorate in economics from the ] in 2007, an honorary doctorate of science from the ] in 2011,<ref name = cs-slate-2001-12>{{Cite news |first=Chris |last=Suellentrop |title=A Real Number |url=http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/culturebox/2001/12/a_real_number.single.html |magazine=] |date=December 21, 2001| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20140104104531/http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/culturebox/2001/12/a_real_number.single.html| archive-date = January 4, 2014| url-status = live| access-date = May 28, 2015 |quote=''A Beautiful Mind's'' John Nash is nowhere near as complicated as the real one.}}</ref> and was keynote speaker at a conference on game theory.<ref>{{cite web|title=Nobel Laureate John Nash to Visit HK|url=http://www.china.org.cn/english/scitech/55597.htm|website=china.org.cn|access-date=January 7, 2017}}</ref> Nash also received honorary doctorates from two West Virginia colleges: the University of Charleston in 2003 and West Virginia University Tech in 2006. He was a prolific guest speaker at a number of events, such as the Warwick Economics Summit in 2005, at the ]. | |||

| From Pittsburgh he went to ] where he worked on his equilibrium theory. He received a ] in ] with a dissertation on non-cooperative games. The thesis, which was written under the supervision of ], contained the definition and properties of what would later be called the ]. His studies on this subject led to three articles: | |||

| * 'Equilibrium Points in N-person Games', published in the '']'' (USA) (]); | |||

| * ''The Bargaining Problem'' (April ]) in ''Econometrica'', and | |||

| * ''Two-person Cooperative Games'' (January ]), also in ''Econometrica''. | |||

| Nash was elected to the ] in 2006<ref>{{Cite web|title=APS Member History |url=https://search.amphilsoc.org/memhist/search?creator=John+F.+Nash&title=&subject=&subdiv=&mem=&year=&year-max=&dead=&keyword=&smode=advanced |access-date=May 25, 2021|website=search.amphilsoc.org}}</ref> and became a fellow of the American Mathematical Society in 2012.<ref>. Retrieved February 24, 2013.</ref> | |||

| ==Personal life== | |||

| On May 19, 2015, a few days before his death, Nash, along with ], was awarded the 2015 ] by King ] at a ceremony in Oslo.<ref>{{cite web |title=2015: Nash and Nirenberg |url=https://abelprize.no/abel-prize-laureates/2015 |access-date=August 2, 2022 |website=abelprize.no }}</ref> | |||

| John Nash was born in the small ]n town of ], the son of John Nash Sr., an electrical engineer, and Virginia Martin, a teacher. By the time he was about twelve years old he was showing great interest in carrying out scientific experiments in his room at home. | |||

| == Personal life == | |||

| Martha, his sister, seems to have been a remarkably normal child while Johnny seemed different from other children. She wrote later in life, "Johnny was always different. knew he was different. And they knew he was bright. He always wanted to do things his way. Mother insisted I do things for him, that I include him in my friendships. ... but I wasn't too keen on showing off my somewhat odd brother". | |||

| In 1951, the ] (MIT) hired Nash as a ] in the mathematics faculty. About a year later, Nash began a relationship with Eleanor Stier, a nurse he met while admitted as a patient. They had a son, John David Stier,<ref name = cs-slate-2001-12 /> but Nash left Stier when she told him of her pregnancy.<ref>Goldstein, Scott (April 10, 2005) , Boston.com News.</ref> The film based on Nash's life, ''A Beautiful Mind'', was criticized during the run-up to the 2002 Oscars for omitting this aspect of his life. He was said to have abandoned her based on her social status, which he thought to have been beneath his.<ref>Sutherland, John (March 18, 2002) , ''The Guardian'', March 18, 2002.</ref> | |||

| In ], in 1954, while in his twenties, Nash was arrested for ] in a sting operation targeting gay men.<ref>{{ cite news |title=John Nash, mathematician – obituary |url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/11627306/John-Nash-mathematician-obituary.html |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20220111/https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/11627306/John-Nash-mathematician-obituary.html |archive-date=January 11, 2022 |url-access=subscription |url-status=live |newspaper=The Telegraph |date=May 24, 2015 |access-date=August 29, 2016}}{{cbignore}}</ref> Although the charges were dropped, he was stripped of his top-secret ] and fired from ], where he had worked as a consultant.<ref>{{cite news |first=Sylvia |last=Nasar |author-link=Sylvia Nasar |title=The sum of a man |url=https://www.theguardian.com/books/2002/mar/26/biography.highereducation |quote=Contrary to widespread references to Nash's "numerous homosexual liaisons", he was not gay. While he had several emotionally intense relationships with other men when he was in his early 20s, I never interviewed anyone who claimed, much less provided evidence, that Nash ever had sex with another man. Nash was arrested in a police trap in a public lavatory in Santa Monica in 1954, at the height of the McCarthy hysteria. The military think-tank where he was a consultant, stripped him of his top-secret security clearance and fired him ... The charge – indecent exposure – was dropped. |newspaper=] |date=March 25, 2002 |access-date=July 9, 2012}}</ref> | |||

| At MIT, he met ], a math student from ], whom he married in February ]. Their son, ] (b. 1959), remained nameless for a year because Alicia, having just committed Nash to a mental hospital, felt that he should have a say in what to name the baby. John became a mathematician, but, like his father, he was diagnosed a paranoid schizophrenic. Nash had another son, John David (b. ], ]), by Eleanor Stier, but refused to have anything to do with them. Sylvia Nasar, Nash's biographer, cites evidence that Nash was bisexual. However, John and Alicia denied such on ] in ]. | |||

| Not long after breaking up with Stier, Nash met ], a ] from ]. Lardé was graduated from ], having majored in physics.<ref name="Nash1995" /> They married in February 1957. Although Nash was an ],<ref name="Sylvia Nasar 2011 143">], Chapter 17: Bad Boys, p. 143: "In this circle, Nash learned to make a virtue of necessity, styling himself self-consciously as a "free thinker." He announced that he was an atheist."</ref> the ceremony was performed in an ].<ref name="charlesmartin">{{Cite web|last=Livio|first=Susan K. |date=June 11, 2017|title=Son of 'A Beautiful Mind' John Nash has one regret |url=https://www.nj.com/healthfit/2017/06/two_years_after_parents_death_son_of_a_beautiful_m.html |access-date=June 17, 2020 |website=NJ Advance Media|language=en}}</ref> In 1958, Nash was appointed to a tenured position at MIT, and his first signs of mental illness soon became evident. He resigned his position at MIT in the spring of 1959.<ref name="Nash1995" /> His son, John Charles Martin Nash, was born a few months later. The child was not named for a year<ref name = cs-slate-2001-12 /> because Alicia felt that Nash should have a say in choosing the name. Due to the stress of dealing with his illness, Nash and Lardé divorced in 1963. After his final hospital discharge in 1970, Nash lived in Lardé's house as a ]. This stability seemed to help him, and he learned how to consciously discard his paranoid ]s.<ref name='david'>, ''The New York Times'', June 11, 1998</ref> Princeton allowed him to audit classes. He continued to work on mathematics and was eventually allowed to teach again. In the 1990s, Lardé and Nash resumed their relationship, remarrying in 2001. John Charles Martin Nash earned a PhD in mathematics from ] and was diagnosed with ] as an adult.<ref name="charlesmartin" /> | |||

| Although she divorced him in ], Alicia took him back in ]. According to Sylvia Nasar's biography of Nash, Alicia referred to him as her "boarder," and they lived "like two distantly related individuals under one roof" until he won the ] in ], when they renewed their relationship. They remarried on ], ]. | |||

| == |

== Death == | ||

| On May 23, 2015, Nash and his wife died in a car accident on the ] in ] while returning home from receiving the ] in Norway. The driver of the taxicab they were riding in from Newark Airport lost control of the cab and struck a guardrail. Both passengers were ejected and killed.<ref></ref> At the time of his death, Nash was a longtime resident of New Jersey. He was survived by two sons, John Charles Martin Nash, who lived with his parents at the time of their death, and elder child John Stier.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://business.highbeam.com/62734/article-1P1-51401334/john-forbes-nash-may-lose-nj-home |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130518131511/http://business.highbeam.com/62734/article-1P1-51401334/john-forbes-nash-may-lose-nj-home |archive-date=May 18, 2013 |title=John Forbes Nash May Lose N.J. Home |agency=] |date=March 14, 2002 |quote=West Windsor, N.J.: John Forbes Nash Jr., whose life is chronicled in the Oscar-nominated movie ''A Beautiful Mind,'' could lose his home if the township picks one of its proposals to replace a nearby bridge. |access-date=February 22, 2011 |via=]}}</ref> | |||

| Following his death, obituaries appeared in scientific and popular media throughout the world. In addition to their obituary for Nash,<ref name="NYT death">{{cite news |first=Erica |last=Goode |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/25/science/john-nash-a-beautiful-mind-subject-and-nobel-winner-dies-at-86.html |title=John F. Nash Jr., Math Genius Defined by a 'Beautiful Mind,' Dies at 86 |work=] |date=May 24, 2015 |access-date=May 24, 2015}}</ref> '']'' published an article containing quotes from Nash that had been assembled from media and other published sources. The quotes consisted of Nash's reflections on his life and achievements.<ref name="NYT quotes">{{cite news |title=The Wisdom of a Beautiful Mind |url=https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/05/25/science/john-nash-quotes.html |website=] |access-date=May 25, 2015 |date=May 24, 2015}}</ref> | |||

| In ], Nash began to show the first signs of his mental illness. He became paranoid and was admitted into the ], April-May ], where he was diagnosed with '] ]'. After a problematic stay in ] and ], Nash returned to Princeton in ]. He remained in and out of mental hospitals until ], undergoing various treatments including ] (a.k.a. ]) ] ]. | |||

| == Legacy == | |||

| Some of his treatments may have worsened his condition because his doctors did not realize the centrality of work and community to curing mental illness, and the most successful "treatment" seems to have been administrative decisions at Princeton's mathematics department and computer center to allow Nash to use university facilities for his researches during this period, although the researches were initially delusional. | |||

| At Princeton in the 1970s, Nash became known as "The Phantom of Fine Hall"<ref>{{cite news |last=Kwon |first=Ha Kyung |title=Nash GS '50: 'The Phantom of Fine Hall' |url=http://dailyprincetonian.com/news/2010/12/nash-gs-50-the-phantom-of-fine-hall/ |access-date=May 6, 2014 |newspaper=] |date=December 10, 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140506091547/http://dailyprincetonian.com/news/2010/12/nash-gs-50-the-phantom-of-fine-hall/ |archive-date=May 6, 2014 }}</ref> (Princeton's mathematics center), a shadowy figure who would scribble arcane equations on blackboards in the middle of the night. | |||

| He is referred to in a novel set at Princeton, ''The Mind-Body Problem'', 1983, by ].<ref name="Nasar1994">{{cite news |last1=Nasar |first1=Sylvia |author-link1=Sylvia Nasar |title=The Lost Years of a Nobel Laureate |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1994/11/13/business/the-lost-years-of-a-nobel-laureate.html |website=] |access-date=May 6, 2014 |location=Princeton, New Jersey |date=November 13, 1994}}</ref> | |||

| In student and on-campus legend, Nash became "The Phantom of Fine Hall" (Fine Hall is Princeton's mathematics center), a shadowy figure who would scribble arcane equations on blackboards in the middle of the night. The legend appears in a work of fiction based on Princeton life, "The Mind-Body Problem", by Rebecca Goldstein. | |||

| ]'s biography of Nash, '']'', was published in 1998. A ] was released in 2001, directed by ] with ] playing Nash; it won four ], including ]. For his performance as Nash, Crowe won the ] at the ] and the ] at the ]. Crowe was nominated for the ] at the ]; ] won for his performance in '']''. | |||

| However, encouraged by his wife Alicia, Nash persisted in working in a communitarian setting where his eccentricities were unremarked and developed, among other interests, an interest in the calculation of exact values of large numbers, researches which drove him to Princeton's Information Centers, where he developed computer programs (of high quality) for his work. Here he had more contact with Princetonians and also, in the late 1980s, began to use electronic mail to gradually link with working mathematicians who realized that he was "John Nash" and his new work had value. | |||

| == Awards == | |||

| They formed part of the nucleus of a group that contacted the Nobel committee and was able to vouch for Nash's ability to receive the award in recognition of his early work. | |||

| * 1978 – ] (with ])<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.informs.org/Recognizing-Excellence/Award-Recipients/John-F.-Nash|title=John F. Nash|access-date=October 10, 2022|website=]}}</ref> "for their outstanding contributions to the theory of games" | |||

| * 1994 – ] (with ] and ])<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/lists/all-prizes-in-economic-sciences/|access-date=October 10, 2022|title=All prizes in economic sciences|website=The Nobel Prize}}</ref> "for their pioneering analysis of equilibria in the theory of non-cooperative games" | |||

| * 1999 – ]<ref name="steele" /> for his 1956 paper "The imbedding problem for Riemannian manifolds" | |||

| * 2002 class of ]s of the ]<ref>{{citation|url=https://www.informs.org/Recognizing-Excellence/Fellows/Fellows-Alphabetical-List|title=Fellows: Alphabetical List|publisher=]|access-date=October 9, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190510220119/https://www.informs.org/Recognizing-Excellence/Fellows/Fellows-Alphabetical-List|archive-date=May 10, 2019}}</ref> | |||

| * 2010 – ]<ref>{{cite web |website=]|title=John F. Nash Jr.: 2010 Honoree |url=http://www.cshl.edu/DHMD/2010-Honoree-John-F-Nash-Jr.html |access-date=July 16, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141017125106/http://www.cshl.edu/DHMD/2010-Honoree-John-F-Nash-Jr.html |archive-date=October 17, 2014 }}</ref> | |||

| * 2015 – ] (with ])<ref>{{cite web |title=A 'long awaited recognition': Nash receives Abel Prize for revered work in mathematics|url=https://www.princeton.edu/main/news/archive/S42/72/29C63/|website=Princeton University|date=March 26, 2015 |access-date=October 10, 2022|last=Kelly|first=Morgan|department=Office of Communications}}</ref> "for striking and seminal contributions to the theory of nonlinear partial differential equations and its applications to geometric analysis" | |||

| == Documentaries and interviews == | |||

| The 1990s brought a return of his ], and Nash has taken care to manage the symptoms of his mental illness. He is still hoping to score substantial scientific results. His recent work involves some very interesting ventures in advanced game theory including partial agency which show that as in early career, he prefers to select his own path and problems. | |||

| * {{cite episode|last=Wallace|first=Mike (host)|author-link1=Mike Wallace|date=March 17, 2002|network=]|series=60 Minutes|series-link=60 Minutes|season=34|number=26|title=John Nash's Beautiful Mind}} | |||

| * {{cite episode|title=A Brilliant Madness|url=https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/films/nash|access-date=October 11, 2022|series=American Experience|series-link=American Experience|network=]|date=April 28, 2002|transcript=Transcript|transcript-url=https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/films/nash/#transcript|last=Samels|first=Mark (director)}} | |||

| * {{cite interview|interviewer=Marika Griehsel|last=Nash|first=John|date=September 1–4, 2004|title=John F. Nash Jr.|publisher=Nobel Prize Outreach|url=https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/1994/nash/interview/}} | |||

| * {{cite interview|interviewer=]|last=Nash|first=John|date=December 5, 2009|title=One on One|publisher=]}} ({{YouTube|UiWBWwCa1E0|Part 1}}, {{YouTube|ufKIgW9XrCE|Part 2}}) | |||

| * {{cite magazine|title=Interview with Abel Laureate John F. Nash Jr.|interviewer=Martin Raussen and Christian Skau|date=September 2015|magazine=Newsletter of the European Mathematical Society|volume=97|year=2015|pages=26–31|url=https://ems.press/content/serial-issue-files/13732|issn=1027-488X|mr=3409221}} | |||

| == Publication list == | |||

| ==Career== | |||

| {{refbegin|30em}} | |||

| * {{cite journal|last1=Nash|last2=Nash|first1=John F.|first2=John F. Jr.|title=Sag and tension calculations for cable and wire spans using catenary formulas|volume=64|issue=10|pages=685–692|doi=10.1109/T-AIEE.1945.5059021|year=1945|journal=]|s2cid=51640174 }} | |||

| *{{cite journal|mr=0035977|last1=Nash|first1=John F. Jr.|title=The bargaining problem|journal=]|volume=18|year=1950a|pages=155–162|issue=2|doi=10.2307/1907266|jstor=1907266 |zbl=1202.91122|s2cid=153422092}} | |||

| *{{cite journal|mr=0031701|last1=Nash|first1=John F. Jr.|title=Equilibrium points in {{mvar|n}}-person games|journal=]|volume=36|year=1950b|pages=48–49|doi=10.1073/pnas.36.1.48|issue=1|pmid=16588946 |pmc=1063129 |bibcode=1950PNAS...36...48N |doi-access=free|zbl=0036.01104}} | |||

| *{{cite conference|mr=0039223|last1=Nash|first1=J. F.|last2=Shapley|first2=L. S.|author-link2=Lloyd Shapley|title=A simple three-person poker game|zbl=0041.25602|book-title=Contributions to the Theory of Games, Volume I|pages=105–116|series=Annals of Mathematics Studies|volume=24|publisher=]|location=Princeton, NJ|year=1950|doi=10.1515/9781400881727-011|editor-last1=Kuhn|editor-last2=Tucker|editor-first1=H. W.|editor-first2=A. W.|editor-link2=Albert W. Tucker|editor-link1=Harold W. Kuhn}} | |||

| *{{cite journal|mr=0043432|last1=Nash|first1=John|title=Non-cooperative games|journal=]|series=Second Series|volume=54|year=1951|pages=286–295|doi=10.2307/1969529|issue=2|jstor=1969529 |zbl=0045.08202}} | |||

| * {{cite conference|title=Algebraic approximations of manifolds|last1=Nash|first1=John|pages=516–517|url=https://www.mathunion.org/icm/proceedings|book-title=Proceedings of the International Congress of Mathematicians: Cambridge, Massachusetts, U. S. A., 1950. Volume I|year=1952a|location=Providence, RI|publisher=]|editor-first1=Lawrence M.|editor-last1=Graves|editor-first3=Paul A.|editor-last3=Smith|editor-first2=Einar|editor-last2=Hille|editor-first4=Oscar|editor-last4=Zariski|editor-link4=Oscar Zariski|editor-link2=Einar Hille|editor-link3=Paul Althaus Smith}} | |||

| * {{cite journal|mr=0050928|last1=Nash|first1=John|title=Real algebraic manifolds|journal=]|series=Second Series|volume=56|year=1952b|pages=405–421|issue=3|doi=10.2307/1969649|jstor=1969649 |zbl=0048.38501}} | |||

| * {{cite journal|mr=0053471|last1=Nash|first1=John|title=Two-person cooperative games|journal=]|volume=21|year=1953|pages=128–140|doi=10.2307/1906951|issue=1|jstor=1906951 |zbl=0050.14102}} | |||

| * {{cite journal|mr=3363438|last1=Mayberry|first1=J. P.|last2=Nash|first2=J. F.|last3=Shubik|first3=M.|author-link3=Martin Shubik|title=A comparison of treatments of a duopoly situation|journal=]|volume=21|year=1953|issue=1|pages=141–154|doi=10.2307/1906952|jstor=1906952 |zbl=0050.15104|s2cid=154750660 }} | |||

| * {{cite journal|mr=0065993|last1=Nash|first1=John|title=C<sup>1</sup> isometric imbeddings|journal=]|series=Second Series|volume=60|year=1954|pages=383–396|issue=3|doi=10.2307/1969840|jstor=1969840 |zbl=0058.37703}} | |||

| * {{cite conference|mr=3363439|last1=Kalisch|first1=G. K.|last2=Milnor|first2=J. W.|author-link2=John Milnor|last3=Nash|first3=J. F.|last4=Nering|first4=E. D.|title=Some experimental {{mvar|n}}-person games|book-title=Decision Processes|pages=301–327|publisher=]|location=New York|year=1954|zbl=0058.13904|editor-last1=Thrall|editor-last2=Coombs|editor-last3=Davis|editor-first1=R. M.|editor-first2=C. H.|editor-first3=R. L.|editor-link1=Robert M. Thrall|editor-link2=Clyde Coombs}} | |||

| * {{cite journal|mr=0071081|last1=Nash|first1=John|title=A path space and the Stiefel–Whitney classes|journal=]|volume=41|year=1955|pages=320–321|issue=5|doi=10.1073/pnas.41.5.320|pmid=16589673 |pmc=528087 |bibcode=1955PNAS...41..320N |doi-access=free|zbl=0064.17503}} | |||

| * {{cite journal|mr=0075639|last1=Nash|first1=John|title=The imbedding problem for Riemannian manifolds|journal=]|series=Second Series|volume=63|year=1956|pages=20–63|issue=1|doi=10.2307/1969989|jstor=1969989 |zbl=0070.38603}} | |||

| * {{cite journal|mr=0089986|last1=Nash|first1=John|title=Parabolic equations|journal=]|volume=43|year=1957|pages=754–758|issue=8|doi=10.1073/pnas.43.8.754|pmid=16590082 |pmc=528534 |bibcode=1957PNAS...43..754N |doi-access=free|zbl=0078.08704}} | |||

| * {{cite journal|mr=0100158|last1=Nash|first1=J.|title=Continuity of solutions of parabolic and elliptic equations|journal=]|volume=80|year=1958|pages=931–954|issue=4|doi=10.2307/2372841|jstor=2372841 |bibcode=1958AmJM...80..931N |zbl=0096.06902}} | |||

| * {{cite journal|mr=0149094|last1=Nash|first1=John|title=Le problème de Cauchy pour les équations différentielles d'un fluide général|journal=]|volume=90|year=1962|pages=487–497|zbl=0113.19405|doi=10.24033/bsmf.1586|doi-access=free}} | |||

| * {{cite journal|mr=0205266|last1=Nash|first1=J.|title=Analyticity of the solutions of implicit function problems with analytic data|journal=]|series=Second Series|volume=84|year=1966|pages=345–355|issue=3|doi=10.2307/1970448|jstor=1970448 |zbl=0173.09202}} | |||

| * {{cite journal|mr=1381967|last1=Nash|first1=John F. Jr.|title=Arc structure of singularities|journal=]|volume=81|year=1995|issue=1|pages=31–38|doi=10.1215/S0012-7094-95-08103-4|zbl=0880.14010}} | |||

| * {{cite journal|last1=Nash|first1=John|year=2002a|title=Ideal money|journal=]|volume=69|issue=1|pages=4–11|doi=10.2307/1061553|jstor=1061553 }} | |||

| * {{cite journal|mr=2510706|last1=Nash|first1=John F. Jr.|title=The agencies method for modeling coalitions and cooperation in games|journal=]|volume=10|year=2008|issue=4|pages=539–564|doi=10.1142/S0219198908002084|zbl=1178.91019}} | |||

| * {{cite conference|mr=2605109|last1=Nash|first1=John F.|title=Ideal money and asymptotically ideal money|book-title=Contributions to Game Theory and Management. Volume II|pages=281–293|publisher=Graduate School of Management, ]|location=St. Petersburg|year=2009a|zbl=1184.91147|isbn=978-5-9924-0020-5|editor-first1=Leon A.|editor-last1=Petrosjan|editor-first2=Nikolay A.|editor-last2=Zenkevich|editor-link1=Leon Petrosyan}} | |||

| * {{cite journal|mr=2642155|last1=Nash|first1=John F.|title=Studying cooperative games using the method of agencies|journal=International Journal of Mathematics, Game Theory, and Algebra|volume=18|year=2009b|issue=4–5|pages=413–426|zbl=1293.91015}} | |||

| * {{cite journal|last1=Nash|first1=John F. Jr.|last2=Nagel|first2=Rosemarie|author2-link=Rosemarie Nagel|last3=Ockenfels|first3=Axel|last4=Selten|first4=Reinhard|title=The agencies method for coalition formation in experimental games|journal=]|volume=109|issue=50|year=2012|pages=20358–20363|doi=10.1073/pnas.1216361109|pmid=23175792 |pmc=3528550 |bibcode=2012PNAS..10920358N |doi-access=free|author-link4=Reinhard Selten|author-link3=Axel Ockenfels}} | |||

| * {{cite book |editor-last1=Nash | editor-first1=John Forbes Jr. | editor-last2=Rassias | editor-first2=Michael Th. | title=Open problems in mathematics|title-link=Open Problems in Mathematics | publisher=]|location=New York | year=2016|mr=3470099|isbn=978-3-319-32160-8|doi=10.1007/978-3-319-32162-2|zbl=1351.00027}} | |||

| {{refend}} | |||

| Four of Nash's game-theoretic papers {{harvs|last=Nash|year=1950a|year2=1950b|year3=1951|year4=1953}} and three of his ] papers {{harvs|last=Nash|year=1952b|year2=1956|year3=1958}} were collected in the following: | |||

| * {{cite encyclopedia|mr=1888522|title=The essential John Nash|editor-first1=Harold W.|editor-last1=Kuhn|editor-first2=Sylvia|editor-last2=Nasar|publisher=]|location=Princeton, NJ|year=2002|isbn=0-691-09527-2|doi=10.1515/9781400884087|editor-link1=Harold Kuhn|editor-link2=Sylvia Nasar|zbl=1033.01024}} | |||

| == References == | |||

| In the summer of ] he worked at the ] in ], where he returned for shorter periods in ] and ]. From ]-] he taught calculus courses at Princeton, studied and managed to stay out of military service. During this time, he proved the ], an important result in ] about ]s. | |||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| == Bibliography == | |||

| He was at MIT from 1951 until the spring of 1959, which included a ] year at the ] in Princeton. | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Nasar|first=Sylvia|author-link=Sylvia Nasar|title=A Beautiful Mind|url=https://archive.org/details/beautifulmind00sylv|url-access=registration|year=1998|publisher=]|isbn=978-1-4391-2649-3|location=New York}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Nasar|first=Sylvia|author-link=Sylvia Nasar|editor-last=Kuhn|editor-first=Harold W.|editor-link=Harold W. Kuhn|title=The Essential John Nash|chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/essentialjohnnas00john|chapter-url-access=registration|year=2002|publisher=]|isbn=978-0-691-09610-0|ref=SNasar|pages=xi–xxv|jstor=j.ctt1c3gwz0|chapter=Introduction|location=Princeton}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Siegfried|first=Tom|title=A Beautiful Math|year=2006|publisher=]|isbn=978-0-309-10192-9|location=Washington, D.C.}} | |||

| * {{MacTutor|id=Nash}} | |||

| == External links == | |||

| He held a research position at ] from ]-], but there was a 30-year gap between then and ] which was void of any scientific publications. | |||

| {{Sister project links|d=Q128736|commons=category:John Forbes Nash|m=no|mw=no|species=no|voy=no|s=no|wikt=no|n=no|b=no|v=no}} | |||

| * | |||

| * {{MathGenealogy|id=18590}} | |||

| * | |||

| * 2002 '']'' article by ], about Nash's work and world government | |||

| * {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120219190420/http://www.nsa.gov/public_info/press_room/2012/nash_exhibit.shtml |date=February 19, 2012 }} to ] for public viewing, 2012 | |||

| * {{cite encyclopedia |title=John F. Nash Jr. (1928–2015) |url=http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/bios/Nash.html |encyclopedia=] |edition=2nd |series=] |publisher=] |year=2016}} | |||

| * from Princeton's Mudd Library, including a copy of ] | |||

| * from the Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences | |||

| * {{Nobelprize|namn=John F. Nash Jr.}} | |||

| {{s-start}} | |||

| He currently holds an appointment in mathematics at Princeton. While cautious with people he does not know, insiders cite a dry sense of humor. | |||

| {{s-ach|aw}} | |||

| {{s-bef | before = ] | before2 = ] }} | |||

| {{s-ttl | title = ] | years = 1994 |alongside= ], ]}} | |||

| {{s-aft | after = ] }} | |||

| {{s-end}} | |||

| {{Nobel laureates in economics|state=autocollapse}} | |||

| The contribution of his wife Alicia was quite significant. She supported him during his delusional phase and saw how membership, no matter how humble, in the Princeton community helped Nash get better. Alicia also worked, rather courageously, as a computer programmer in male-dominated companies to support herself, John, and their son. | |||

| {{Abel Prize laureates|state=autocollapse}} | |||

| {{John von Neumann Theory Prize recipients}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ===Recognition=== | |||

| In ] he was awarded the ] for his invention of non-cooperative equilibriums, now called ]. | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Nash, John Forbes Jr.}} | |||

| In 1994 he received the ] as a result of his game theory work at Princeton as a graduate student. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Between ] and ] John Nash published a total of 23 scientific studies. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ==Movie inspired by Nash's life== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| The ] '']'', ] and directed by ], was inspired by Nash's life; it received four ]s, including ]. The film is loosely based on the ] of the same title, written by ] (]). | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| The film has been criticized for its inaccurate portrayal of John Nash's life and ] as well as for the incorrect representation of the famous ]. The ] documentary ''A Brilliant Madness'' attempts to portray his life more accurately. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Major departures from Nash's life and the accurate book include no mention of Nash's sexual adventures while at Rand and his second family in Boston... although his son from Boston plays a bit part in the movie as a nurse, manhandling Nash in the hospital. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Furthermore, his preservation at Princeton is shown by the movie as exclusively the work of professors in the Mathematics department while in fact administrators, especially at Firestone Library and the Information Centers in later years, also played a role. They are unfortunately portrayed in the movie only as one library clerk who didn't get interoffice mail. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Also, Nash's hallucinations weren't visual and auditory as shown in the film. They were auditory, exclusively. It is true that his handlers, both from faculty and administration, had to introduce him to assistants and strangers. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| A deleted scene from ''A Beautiful Mind'' reveals that Nash (re)invented the ] ]. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| ] | |||

| *] | |||

| ] | |||

| *] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| ] | |||

| {{wikiquote}} | |||

| ] | |||

| * | |||

| ] | |||

| * at the ] website | |||

| ] | |||

| * | |||

| ] | |||

| * | |||

| ] | |||

| * from Princeton's Mudd Library, including a copy of in ] | |||

| ] | |||

| *, a 2001 ''Daily Princetonian'' interview | |||

| ] | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| {{wikiquote}} | |||

| * | |||

| * at the ] website | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * from Princeton's Mudd Library, including a copy of in ] | |||

| *, a 2001 ''Daily Princetonian'' interview | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 21:59, 26 November 2024

American mathematician (1928–2015)

| John Forbes Nash Jr. | |

|---|---|

Nash in the 2000s Nash in the 2000s | |

| Born | (1928-06-13)June 13, 1928 Bluefield, West Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | May 23, 2015(2015-05-23) (aged 86) Monroe Township, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Education | |

| Known for | |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 2 |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | Non-Cooperative Games (1950) |

| Doctoral advisor | Albert W. Tucker |

John Forbes Nash, Jr. (June 13, 1928 – May 23, 2015), known and published as John Nash, was an American mathematician who made fundamental contributions to game theory, real algebraic geometry, differential geometry, and partial differential equations. Nash and fellow game theorists John Harsanyi and Reinhard Selten were awarded the 1994 Nobel Prize in Economics. In 2015, he and Louis Nirenberg were awarded the Abel Prize for their contributions to the field of partial differential equations.

As a graduate student in the Princeton University Department of Mathematics, Nash introduced a number of concepts (including Nash equilibrium and the Nash bargaining solution) which are now considered central to game theory and its applications in various sciences. In the 1950s, Nash discovered and proved the Nash embedding theorems by solving a system of nonlinear partial differential equations arising in Riemannian geometry. This work, also introducing a preliminary form of the Nash–Moser theorem, was later recognized by the American Mathematical Society with the Leroy P. Steele Prize for Seminal Contribution to Research. Ennio De Giorgi and Nash found, with separate methods, a body of results paving the way for a systematic understanding of elliptic and parabolic partial differential equations. Their De Giorgi–Nash theorem on the smoothness of solutions of such equations resolved Hilbert's nineteenth problem on regularity in the calculus of variations, which had been a well-known open problem for almost sixty years.

In 1959, Nash began showing clear signs of mental illness, and spent several years at psychiatric hospitals being treated for schizophrenia. After 1970, his condition slowly improved, allowing him to return to academic work by the mid-1980s.

Nash's life was the subject of Sylvia Nasar's 1998 biographical book A Beautiful Mind, and his struggles with his illness and his recovery became the basis for a film of the same name directed by Ron Howard, in which Nash was portrayed by Russell Crowe.

Early life and education

John Forbes Nash Jr. was born on June 13, 1928, in Bluefield, West Virginia. His father and namesake, John Forbes Nash Sr., was an electrical engineer for the Appalachian Electric Power Company. His mother, Margaret Virginia (née Martin) Nash, had been a schoolteacher before she was married. He was baptized in the Episcopal Church. He had a younger sister, Martha (born November 16, 1930).

Nash attended kindergarten and public school, and he learned from books provided by his parents and grandparents. Nash's parents pursued opportunities to supplement their son's education, and arranged for him to take advanced mathematics courses at nearby Bluefield College (now Bluefield University) during his final year of high school. He attended Carnegie Institute of Technology (which later became Carnegie Mellon University) through a full benefit of the George Westinghouse Scholarship, initially majoring in chemical engineering. He switched to a chemistry major and eventually, at the advice of his teacher John Lighton Synge, to mathematics. After graduating in 1948, with both a B.S. and M.S. in mathematics, Nash accepted a fellowship to Princeton University, where he pursued further graduate studies in mathematics and sciences.