| Revision as of 02:02, 15 March 2023 edit177.180.101.137 (talk) →HistoryTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 05:48, 26 November 2024 edit undoDicklyon (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Rollbackers476,679 edits case fix | ||

| (32 intermediate revisions by 28 users not shown) | |||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

| | country = ] | | country = ] | ||

| | country_admin_divisions_title = ] | | country_admin_divisions_title = ] | ||

| | country_admin_divisions = ] | | country_admin_divisions = ] | ||

| | country_admin_divisions_title_1 = ] | | country_admin_divisions_title_1 = ] | ||

| | country_admin_divisions_1 = ] | | country_admin_divisions_1 = ] | ||

| | country_admin_divisions_title_2 = ] | | country_admin_divisions_title_2 = ] | ||

| | country_admin_divisions_2 = ] | | country_admin_divisions_2 = ] | ||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

| | island_type = Shield Volcanoes (last eruption in 1835) | | island_type = Shield Volcanoes (last eruption in 1835) | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Robinson Crusoe Island''' ({{ |

'''Robinson Crusoe Island''' ({{langx|es|Isla Róbinson Crusoe}}, {{IPA|es|ˈisla ˈroβinsoŋ kɾuˈso|pron}}) is the second largest of the ], situated 670 km (362 nmi; 416 mi) west of ], ], in the ]. It is the more populous of the inhabited islands in the ] (the other being ]), with most of that in the town of ] at Cumberland Bay on the island's north coast.<ref name="INE">. Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas (2012). Retrieved 2 January 2013.</ref> The island was formerly known as '''Más a Tierra''' ({{gloss|Closer to Land}}).<ref name=severin2002>{{cite book |last=Severin |first=Tim |author-link=Tim Severin |year=2002 |title=In Search of Robinson Crusoe |publisher=Basic Books |location=New York |pages= |isbn=978-046-50-7698-7 |url=https://archive.org/details/insearchofrobins00seve_0/page/23 }}</ref> | ||

| From 1704 to 1709, the island was home to the ] sailor ], who at least partially inspired novelist ]'s fictional ] in his 1719 novel, although the novel is explicitly set in the ].<ref>{{cite book |last=Severin |first=Tim |year=2002 |title=In Search of Robinson Crusoe |publisher=Basic Books |location=New York |pages= |isbn=978-046-50-7698-7 |url=https://archive.org/details/insearchofrobins00seve_0/page/17 }}</ref> This was just one of several survival stories from the period of which Defoe would have been aware.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/09/robinson-crusoe-alexander-selkirk-history/|title=Debunking the Myth of the 'Real' Robinson Crusoe|work=National Geographic|author=Little, Becky|date=28 September 2016|access-date=30 September 2016}}</ref> To reflect the literary lore associated with the island and attract tourists, the Chilean government renamed |

From 1704 to 1709, the island was home to the ] Scottish sailor ], who at least partially inspired novelist ]'s fictional ] in his 1719 novel, although the novel is explicitly set in the ].<ref>{{cite book |last=Severin |first=Tim |year=2002 |title=In Search of Robinson Crusoe |publisher=Basic Books |location=New York |pages= |isbn=978-046-50-7698-7 |url=https://archive.org/details/insearchofrobins00seve_0/page/17 }}</ref> This was just one of several survival stories from the period of which Defoe would have been aware.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/09/robinson-crusoe-alexander-selkirk-history/|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160928201018/http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/09/robinson-crusoe-alexander-selkirk-history/|url-status=dead|archive-date=28 September 2016|title=Debunking the Myth of the 'Real' Robinson Crusoe|work=National Geographic|author=Little, Becky|date=28 September 2016|access-date=30 September 2016}}</ref> To reflect the literary lore associated with the island and attract tourists, the Chilean government renamed it Robinson Crusoe Island in 1966.<ref name=severin2002/> | ||

| ==Geography== | ==Geography== | ||

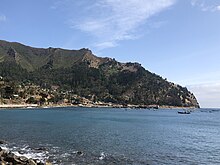

| ], on the north coast at Cumberland Bay]] | ], on the north coast at Cumberland Bay]] | ||

| Robinson Crusoe Island has a mountainous and undulating terrain, formed by ancient ] flows which have built up from numerous ] episodes. The highest point on the island is {{convert|915|m|ft|0|abbr=on}} above sea level at El Yunque. Intense ] has resulted in the formation of steep valleys and ridges. A narrow peninsula is formed in the southwestern part of the island called Cordón Escarpado. The island of Santa Clara is located just off the southwest coast.<ref name="santibanez2004parques"/> | Robinson Crusoe Island has a mountainous and undulating terrain, formed by ancient ] flows, which have built up from numerous ] episodes. The highest point on the island is {{convert|915|m|ft|0|abbr=on}} above sea level at El Yunque. Intense ] has resulted in the formation of steep valleys and ridges. A narrow peninsula is formed in the southwestern part of the island, called Cordón Escarpado. The island of Santa Clara is located just off the southwest coast.<ref name="santibanez2004parques"/> | ||

| Robinson Crusoe Island lies to the west of the boundary between the ] and the ] |

Robinson Crusoe Island lies to the west of the boundary between the ] and the ]; it rose from the ocean 3.8 – 4.2 million years ago. A volcanic eruption on the island was reported in 1743 from El Yunque, but this event is uncertain. On 20 February 1835, a day-long eruption began from a submarine vent {{convert|1.6|km|mi|1}} north of Punta Bacalao. The event was quite minor—only a ] 1 eruption—but it produced explosions and flames that lit up the island, along with ]s.<ref name="santibanez2004parques"/>{{failed verification|date=April 2014}} | ||

| ==Climate== | ==Climate== | ||

| Robinson Crusoe has a ] climate, moderated by the cold ], which flows to the east of the island, and the southeast ]. Temperatures range from {{convert|3|C|F|0}} to {{convert| |

Robinson Crusoe has a ] climate, moderated by the cold ], which flows to the east of the island, and the southeast ]. Temperatures range from {{convert|3|C|F|0}} to {{convert|28.8|C|F}}, with an annual mean of {{convert|15.7|C|F}}. Higher elevations are generally cooler, with occasional frosts. Rainfall is greater in the winter months, and varies with elevation and exposure; elevations above {{convert|500|m|ft|0|abbr=on}} experience almost daily rainfall, while the western, ] side of the island is lower and drier.<ref> Corporacion Nacional Forestal de Chile (2010). Retrieved 27 May 2010. {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120823132640/http://www.conaf.cl/parques/ficha-parque_nacional_archipielago_de_juan_fernandez-35.html |date=23 August 2012 }}</ref> | ||

| {{Weather box | |||

| <div style="width:85%;"> | |||

| |width = auto | |||

| {{Weather box|location = San Juan Bautista, Chile | |||

| |location = Juan Fernández Islands (1991-2020, extremes 1958-present) | |||

| |metric first = yes | |metric first = yes | ||

| |single line = yes | |single line = yes | ||

| |Jan high C = |

|Jan record high C = 28.8 | ||

| |Feb high C = |

|Feb record high C = 27.8 | ||

| |Mar high C = |

|Mar record high C = 27.0 | ||

| |Apr high C = |

|Apr record high C = 26.0 | ||

| |May high C = |

|May record high C = 24.9 | ||

| |Jun high C = |

|Jun record high C = 22.2 | ||

| |Jul high C = |

|Jul record high C = 22.6 | ||

| |Aug high C = |

|Aug record high C = 24.4 | ||

| |Sep high C = |

|Sep record high C = 21.8 | ||

| |Oct high C = |

|Oct record high C = 23.5 | ||

| |Nov high C = |

|Nov record high C = 25.2 | ||

| |Dec high C = |

|Dec record high C = 26.9 | ||

| |year high C = |

|year record high C = 28.8 | ||

| |Jan |

|Jan high C = 21.4 | ||

| |Feb |

|Feb high C = 21.5 | ||

| |Mar |

|Mar high C = 21.2 | ||

| |Apr |

|Apr high C = 19.3 | ||

| |May |

|May high C = 17.8 | ||

| |Jun |

|Jun high C = 16.2 | ||

| |Jul |

|Jul high C = 15.0 | ||

| |Aug |

|Aug high C = 14.8 | ||

| |Sep |

|Sep high C = 15.1 | ||

| |Oct |

|Oct high C = 16.1 | ||

| |Nov |

|Nov high C = 17.8 | ||

| |Dec |

|Dec high C = 19.8 | ||

| |year |

|year high C = 18.0 | ||

| |Jan mean C = 18.8 | |||

| |Feb mean C = 19.0 | |||

| |Mar mean C = 18.6 | |||

| |Apr mean C = 16.9 | |||

| |May mean C = 15.4 | |||

| |Jun mean C = 13.9 | |||

| |Jul mean C = 12.8 | |||

| |Aug mean C = 12.5 | |||

| |Sep mean C = 12.7 | |||

| |Oct mean C = 13.6 | |||

| |Nov mean C = 15.2 | |||

| |Dec mean C = 17.1 | |||

| |year mean C = 15.5 | |||

| |Jan low C = 16.2 | |||

| |Feb low C = 16.5 | |||

| |Mar low C = 16.0 | |||

| |Apr low C = 14.4 | |||

| |May low C = 13.1 | |||

| |Jun low C = 11.7 | |||

| |Jul low C = 10.6 | |||

| |Aug low C = 10.2 | |||

| |Sep low C = 10.3 | |||

| |Oct low C = 11.1 | |||

| |Nov low C = 12.6 | |||

| |Dec low C = 14.5 | |||

| |year low C = 13.1 | |||

| |Jan record low C = 11.4 | |||

| |Feb record low C = 4.2 | |||

| |Mar record low C = 9.0 | |||

| |Apr record low C = 8.2 | |||

| |May record low C = 6.3 | |||

| |Jun record low C = 4.8 | |||

| |Jul record low C = 5.0 | |||

| |Aug record low C = 3.0 | |||

| |Sep record low C = 5.0 | |||

| |Oct record low C = 6.2 | |||

| |Nov record low C = 7.3 | |||

| |Dec record low C = 9.2 | |||

| |year record low C = 3.0 | |||

| |rain colour = green | |rain colour = green | ||

| |Jan rain mm = |

|Jan rain mm = 29.0 | ||

| |Feb rain mm = 33 | |Feb rain mm = 33.4 | ||

| |Mar rain mm = |

|Mar rain mm = 55.1 | ||

| |Apr rain mm = |

|Apr rain mm = 83.5 | ||

| |May rain mm = |

|May rain mm = 150.5 | ||

| |Jun rain mm = |

|Jun rain mm = 184.4 | ||

| |Jul rain mm = |

|Jul rain mm = 130.5 | ||

| |Aug rain mm = 114 | |Aug rain mm = 114.3 | ||

| |Sep rain mm = |

|Sep rain mm = 80.2 | ||

| |Oct rain mm = |

|Oct rain mm = 49.9 | ||

| |Nov rain mm = |

|Nov rain mm = 35.7 | ||

| |Dec rain mm = |

|Dec rain mm = 24.8 | ||

| | |

|year rain mm = 971.3 | ||

| |Feb rain days = 10 | |||

| |Mar rain days = 13 | |||

| |Apr rain days = 15 | |||

| |May rain days = 21 | |||

| |Jun rain days = 23 | |||

| |Jul rain days = 21 | |||

| |Aug rain days = 19 | |||

| |Sep rain days = 16 | |||

| |Oct rain days = 14 | |||

| |Nov rain days = 10 | |||

| |Dec rain days = 10 | |||

| |unit rain days = 0.1 mm | |||

| |Jan humidity = 73 | |Jan humidity = 73 | ||

| |Feb humidity = 73 | |Feb humidity = 73 | ||

| Line 129: | Line 157: | ||

| |Nov humidity = 74 | |Nov humidity = 74 | ||

| |Dec humidity = 73 | |Dec humidity = 73 | ||

| | |

|year humidity = 76 | ||

| | |

|unit rain days = 1.0 mm | ||

| | |

|Jan rain days = 5.6 | ||

| | |

|Feb rain days = 6.1 | ||

| | |

|Mar rain days = 8.8 | ||

| | |

|Apr rain days = 11.2 | ||

| | |

|May rain days = 14.6 | ||

| | |

|Jun rain days = 16.4 | ||

| | |

|Jul rain days = 15.9 | ||

| | |

|Aug rain days = 13.5 | ||

| | |

|Sep rain days = 11.1 | ||

| | |

|Oct rain days = 8.3 | ||

| |Nov rain days = 6.0 | |||

| |source 1 = Climate & Temperature<ref>{{cite web | |||

| |Dec rain days = 5.4 | |||

| | url = http://www.climatetemp.info/juan-fernandez-islands/ | |||

| |year rain days = 123.0 | |||

| | title = San Juan Bautista Climate Guide to the Average Weather & Temperatures with Graphs Elucidating Sunshine and Rainfall Data & Information about Wind Speeds & Humidity | |||

| |Jan sun = 206.7 | |||

| | access-date = 6 March 2010 | publisher = Climate & Temperature | |||

| |Feb sun = 178.9 | |||

| |Mar sun = 170.4 | |||

| |Apr sun = 126.9 | |||

| |May sun = 103.0 | |||

| |Jun sun = 85.1 | |||

| |Jul sun = 98.5 | |||

| |Aug sun = 123.4 | |||

| |Sep sun = 139.0 | |||

| |Oct sun = 171.6 | |||

| |Nov sun = 178.4 | |||

| |Dec sun = 195.7 | |||

| |year sun = 1777.6 | |||

| |source 1 = Dirección Meteorológica de Chile (humidity 1931–1960)<ref name=climatenormals>{{cite web | |||

| | url = https://climatologia.meteochile.gob.cl/application/historico/datosNormales/330031 | |||

| | title = Datos Normales y Promedios Históricos Promedios de 30 años o menos | |||

| | publisher = Dirección Meteorológica de Chile | |||

| | language = es | |||

| | access-date = 23 May 2023 | |||

| | archive-date = 23 May 2023 | |||

| | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20230523163759/https://climatologia.meteochile.gob.cl/application/historico/datosNormales/330031 | |||

| | url-status = dead | |||

| }}</ref><ref name=records>{{cite web | |||

| | url = https://climatologia.meteochile.gob.cl/application/historico/temperaturaHistoricaAnual/330031 | |||

| | title = Temperatura Histórica de la Estación Juan Fernández, Estación Meteorológica. (330031) | |||

| | access-date = 23 May 2023 | |||

| | publisher = Dirección Meteorológica de Chile | |||

| | language = es | |||

| | archive-date = 23 May 2023 | |||

| | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20230523164119/https://climatologia.meteochile.gob.cl/application/historico/temperaturaHistoricaAnual/330031 | |||

| | url-status = live | |||

| }}</ref> | }}</ref> | ||

| |source 2 = ] (precipitation days 1981–2010)<ref name=WMOCLINO>{{cite web | |||

| |date=August 2010 | |||

| | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20211009200311/https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/pub/data/normals/WMO/1981-2010/RA-III/Chile/WMO_Normals_Chile%20%285%29.xlsx | |||

| | archive-date = 9 October 2021 | |||

| | url = https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/pub/data/normals/WMO/1981-2010/RA-III/Chile/WMO_Normals_Chile%20(5).xlsx | |||

| | title = World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1981–2010 | |||

| | publisher = World Meteorological Organization | |||

| | access-date = 9 October 2021}}</ref> | |||

| |date = March 2013 | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| </div> | |||

| ==Flora and fauna== | ==Flora and fauna== | ||

| The ] is a ] which includes the ] ]. It is in the ], but often also included within the ]. As ] since 1977, these islands have been considered of maximum scientific importance because of the ] ], ], and ] of flora and fauna. Out of 211 native plant species, 132 (63%) are endemic, as well as more than 230 species of insects.<ref name="wondermondo">. Wondermondo (2012). Retrieved 18 October 2012.</ref> | The ] is a ] which includes the ] ]. It is in the ], but often also included within the ]. As ] since 1977, these islands have been considered of maximum scientific importance because of the ] ], ], and ] of flora and fauna. Out of 211 native plant species, 132 (63%) are endemic, as well as more than 230 species of insects.<ref name="wondermondo">. Wondermondo (2012). Retrieved 18 October 2012.</ref> | ||

| Robinson Crusoe Island has one endemic plant family, ]. The ] is also found there.<ref>Hogan, C. Michael (2008). {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120607230613/http://globaltwitcher.auderis.se/artspec_information.asp?thingid=232 |date=7 June 2012 }}. GlobalTwitcher. Retrieved 18 October 2012.</ref> The ] is an endemic and critically endangered red ], which is best known for its needle-fine black beak and silken feather coverage. The ] is named after the island's former name.<ref name="wondermondo"/> The island (along with neighbouring ]) has been recognised as an ] (IBA) by ] because it supports populations of Masatierra petrels, ]s, Juan Fernandez firecrowns and ]s.<ref name=bli> {{cite web |url=http://datazone.birdlife.org/site/factsheet/parque-nacional-archipiélago-de-juan-fernández:-islas-robinson-crusoe-and-santa-clara-iba-chile|title= Islas Robinson Crusoe and Santa Clara|author=<!--Not stated--> |date=2021|website= BirdLife Data Zone|publisher= BirdLife International|access-date= 22 January 2021}}</ref> | Robinson Crusoe Island has one endemic plant family, ]. The ] is also found there.<ref>Hogan, C. Michael (2008). {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120607230613/http://globaltwitcher.auderis.se/artspec_information.asp?thingid=232 |date=7 June 2012 }}. GlobalTwitcher. Retrieved 18 October 2012.</ref> The ] is an endemic and critically endangered red ], which is best known for its needle-fine black beak and silken feather coverage. The ] is named after the island's former name.<ref name="wondermondo"/> The island (along with neighbouring ]) has been recognised as an ] (IBA) by ] because it supports populations of Masatierra petrels, ]s, Juan Fernandez firecrowns and ]s.<ref name=bli> {{cite web |url=http://datazone.birdlife.org/site/factsheet/parque-nacional-archipiélago-de-juan-fernández:-islas-robinson-crusoe-and-santa-clara-iba-chile|title= Islas Robinson Crusoe and Santa Clara|author=<!--Not stated--> |date=2021|website= BirdLife Data Zone|publisher= BirdLife International|access-date= 22 January 2021}}</ref> | ||

| {{wide image|Panorama view of Robinson Crusoe Island - Chile.jpg|1000px|Robinson Crusoe Island, seen from CS ''Responder'' during work on a ] hydroacoustic monitoring station in 2014<ref>, Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (2014). Retrieved 5 April 2014.</ref>}} | {{wide image|Panorama view of Robinson Crusoe Island - Chile.jpg|1000px|Robinson Crusoe Island, seen from CS ''Responder'' during work on a ] hydroacoustic monitoring station in 2014<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210509105459/https://www.ctbto.org/press-centre/highlights/2014/welcome-back-ha03-robinson-crusoe-island/ |date=9 May 2021 }}, Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (2014). Retrieved 5 April 2014.</ref>}} | ||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| Line 162: | Line 226: | ||

| From 1681 to 1684, a ] man known as ] was ] on the island. Twenty years later, in 1704, the sailor ] was also marooned there, ] for four years and four months. Selkirk had been gravely concerned about the seaworthiness of his ship, ] (which ended up sinking very shortly after), and declared his wish to be left on the island during a mid-voyage restocking stop. His captain, Thomas Stradling, a colleague on the voyage of privateer and explorer ], was tired of his dissent and obliged. All Selkirk had left with him was a musket, gunpowder, carpenter's tools, a knife, a Bible, and some clothing.<ref name="Rogers1712">{{cite book |last=Rogers |first=Woodes |author-link=Woodes Rogers |title=A Cruising Voyage Round the World: First to the South-seas, Thence to the East-Indies, and Homewards by the Cape of Good Hope |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=e1GmdIw7fpgC&pg=PA125 |year=1712 |publisher=A. Bell and B. Lintot |location=London |pages=125–126}}</ref> The story of Selkirk's rescue is included in the 1712 book '']'' by Edward Cooke. | From 1681 to 1684, a ] man known as ] was ] on the island. Twenty years later, in 1704, the sailor ] was also marooned there, ] for four years and four months. Selkirk had been gravely concerned about the seaworthiness of his ship, ] (which ended up sinking very shortly after), and declared his wish to be left on the island during a mid-voyage restocking stop. His captain, Thomas Stradling, a colleague on the voyage of privateer and explorer ], was tired of his dissent and obliged. All Selkirk had left with him was a musket, gunpowder, carpenter's tools, a knife, a Bible, and some clothing.<ref name="Rogers1712">{{cite book |last=Rogers |first=Woodes |author-link=Woodes Rogers |title=A Cruising Voyage Round the World: First to the South-seas, Thence to the East-Indies, and Homewards by the Cape of Good Hope |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=e1GmdIw7fpgC&pg=PA125 |year=1712 |publisher=A. Bell and B. Lintot |location=London |pages=125–126}}</ref> The story of Selkirk's rescue is included in the 1712 book '']'' by Edward Cooke. | ||

| In an 1840 narrative, '']'', ] described the port of Juan Fernandez as a young prison colony.<ref name="Dana1840">{{cite book|last=Dana|first=Richard Henry|author-link=Richard Henry Dana |

In an 1840 narrative, '']'', ] described the port of Juan Fernandez as a young prison colony.<ref name="Dana1840">{{cite book|last=Dana|first=Richard Henry|author-link=Richard Henry Dana Jr.|title=Two Years Before the Mast: A Personal Narrative of Life at Sea|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dS6jsZLYWNAC&pg=PA28|year=1840|publisher=Harper & Brothers|location=New York|pages=28–32}}</ref> The penal institution was soon abandoned and the island again uninhabited<ref name="coulter1845">{{cite book|last=Coulter|first=John|title=Adventures in the Pacific: With Observations on the Natural Productions, Manners and Customs of the Natives of the Various Islands|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=A-E-AAAAYAAJ&pg=PA32|year=1845|publisher=Longmans, Brown & Co|location=London|pages=32–33}}</ref> before a permanent colony was eventually established in the latter part of the 19th century. ] visited the island between 26 April and 5 May 1896, during his solo global circumnavigation on the sloop ''Spray''. The island and its 45 inhabitants are referred to in detail in Slocum's memoir, '']''.<ref>{{cite book|last=Slocum |first=Joshua |title=Sailing Alone Around the World |year=2012 |publisher=Beaufoy Publishing |location=Oxford |isbn=978-190-67-8034-0 |pages=77–82}}</ref> | ||

| ===World War I=== | ===World War I=== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| During ], Vice Admiral ]'s ] stopped and re-coaled at the island 26–28 October 1914, four days before the ]. While at the island, the admiral was unexpectedly rejoined by the armed merchant cruiser '']'', which he had earlier detached to attack Allied shipping in Australian waters. On 9 March 1915 {{SMS|Dresden|1907|6}}, the last surviving cruiser of von Spee's squadron after his death at the ], returned to the island's Cumberland Bay, hoping to be interned by the Chilean authorities. Caught and fired upon by a British squadron at the ] on 14 March, the ship was scuttled by its crew.<ref name="delgado2004">{{cite book|last=Delgado|first=James P.|title=Adventures of a Sea Hunter: In Search of Famous Shipwrecks|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4rVtqI4-_vQC&pg=PA168|year=2004|publisher=Douglas & McIntyre|location=Vancouver|isbn=978-1-926685-60-1|pages=168–174}}</ref> | During ], German Vice Admiral ]'s ] stopped and re-coaled at the island 26–28 October 1914, four days before the ]. While at the island, the admiral was unexpectedly rejoined by the armed merchant cruiser '']'', which he had earlier detached to attack Allied shipping in Australian waters. On 9 March 1915 {{SMS|Dresden|1907|6}}, the last surviving cruiser of von Spee's squadron after his death at the ], returned to the island's Cumberland Bay, hoping to be interned by the Chilean authorities. Caught and fired upon by a British squadron at the ] on 14 March, the ship was scuttled by its crew.<ref name="delgado2004">{{cite book|last=Delgado|first=James P.|title=Adventures of a Sea Hunter: In Search of Famous Shipwrecks|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4rVtqI4-_vQC&pg=PA168|year=2004|publisher=Douglas & McIntyre|location=Vancouver|isbn=978-1-926685-60-1|pages=168–174}}</ref> | ||

| ===2010 tsunami=== | ===2010 tsunami=== | ||

| On 27 February 2010 Robinson Crusoe Island was hit by a tsunami following a ]. The tsunami was about {{convert|3|m|ft|0|abbr=on}} high when it reached the island.<ref>Ricketts, Colin (17 August 2011). . ''Earth Times''. Retrieved 18 October 2012.</ref> Sixteen people |

On 27 February 2010 Robinson Crusoe Island was hit by a tsunami following a ]. The tsunami was about {{convert|3|m|ft|0|abbr=on}} high when it reached the island.<ref>Ricketts, Colin (17 August 2011). . ''Earth Times''. Retrieved 18 October 2012.</ref> Sixteen people were killed and most of the coastal village of San Juan Bautista was washed away.<ref name=bodenham2010>Bodenham, Patrick (9 December 2010). . ''The Independent''. Retrieved 7 April 2014.</ref> The only warning the islanders had came from 12-year-old girl Martina Maturana,<ref>Harrell, Eben (2 March 2010). . ''Time Magazine''. Retrieved 4 March 2010.</ref> who noticed the sudden ] of the sea that forewarns of the arrival of a tsunami wave and saved many of her neighbours from harm.<ref name=bodenham2010/> | ||

| ==Society== | ==Society== | ||

| Line 186: | Line 250: | ||

| ]]] | ]]] | ||

| ] – Juan Fernández cabbage tree]] | ]'' – Juan Fernández cabbage tree]] | ||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| == References == | == References == | ||

| Line 219: | Line 283: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

Latest revision as of 05:48, 26 November 2024

Island of Chile This article is about the Chilean island. For the island in Fiji, see Robinson Crusoe Island (Fiji). For the Arkady Fiedler novel, see Robinson Crusoe Island (novel).

| Native name: Isla Robinson Crusoe | |

|---|---|

Satellite image of Robinson Crusoe Island Satellite image of Robinson Crusoe Island | |

| |

| Geography | |

| Coordinates | 33°38′29″S 78°50′28″W / 33.64139°S 78.84111°W / -33.64139; -78.84111 |

| Type | Shield Volcanoes (last eruption in 1835) |

| Archipelago | Juan Fernández Islands |

| Adjacent to | Pacific Ocean |

| Area | 47.94 km (18.51 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 915 m (3002 ft) |

| Highest point | El Yunque |

| Administration | |

| Chile | |

| Region | Valparaíso |

| Province | Valparaíso province |

| Commune | Juan Fernández Islands |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 843 (2012) |

Robinson Crusoe Island (Spanish: Isla Róbinson Crusoe, pronounced [ˈisla ˈroβinsoŋ kɾuˈso]) is the second largest of the Juan Fernández Islands, situated 670 km (362 nmi; 416 mi) west of San Antonio, Chile, in the South Pacific Ocean. It is the more populous of the inhabited islands in the archipelago (the other being Alejandro Selkirk Island), with most of that in the town of San Juan Bautista at Cumberland Bay on the island's north coast. The island was formerly known as Más a Tierra ('Closer to Land').

From 1704 to 1709, the island was home to the marooned Scottish sailor Alexander Selkirk, who at least partially inspired novelist Daniel Defoe's fictional Robinson Crusoe in his 1719 novel, although the novel is explicitly set in the Caribbean. This was just one of several survival stories from the period of which Defoe would have been aware. To reflect the literary lore associated with the island and attract tourists, the Chilean government renamed it Robinson Crusoe Island in 1966.

Geography

Robinson Crusoe Island has a mountainous and undulating terrain, formed by ancient lava flows, which have built up from numerous volcanic episodes. The highest point on the island is 915 m (3,002 ft) above sea level at El Yunque. Intense erosion has resulted in the formation of steep valleys and ridges. A narrow peninsula is formed in the southwestern part of the island, called Cordón Escarpado. The island of Santa Clara is located just off the southwest coast.

Robinson Crusoe Island lies to the west of the boundary between the Nazca Plate and the South American Plate; it rose from the ocean 3.8 – 4.2 million years ago. A volcanic eruption on the island was reported in 1743 from El Yunque, but this event is uncertain. On 20 February 1835, a day-long eruption began from a submarine vent 1.6 kilometres (1.0 mi) north of Punta Bacalao. The event was quite minor—only a Volcanic Explosivity Index 1 eruption—but it produced explosions and flames that lit up the island, along with tsunamis.

Climate

Robinson Crusoe has a subtropical climate, moderated by the cold Humboldt Current, which flows to the east of the island, and the southeast trade winds. Temperatures range from 3 °C (37 °F) to 28.8 °C (83.8 °F), with an annual mean of 15.7 °C (60.3 °F). Higher elevations are generally cooler, with occasional frosts. Rainfall is greater in the winter months, and varies with elevation and exposure; elevations above 500 m (1,640 ft) experience almost daily rainfall, while the western, leeward side of the island is lower and drier.

| Climate data for Juan Fernández Islands (1991-2020, extremes 1958-present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 28.8 (83.8) |

27.8 (82.0) |

27.0 (80.6) |

26.0 (78.8) |

24.9 (76.8) |

22.2 (72.0) |

22.6 (72.7) |

24.4 (75.9) |

21.8 (71.2) |

23.5 (74.3) |

25.2 (77.4) |

26.9 (80.4) |

28.8 (83.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 21.4 (70.5) |

21.5 (70.7) |

21.2 (70.2) |

19.3 (66.7) |

17.8 (64.0) |

16.2 (61.2) |

15.0 (59.0) |

14.8 (58.6) |

15.1 (59.2) |

16.1 (61.0) |

17.8 (64.0) |

19.8 (67.6) |

18.0 (64.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 18.8 (65.8) |

19.0 (66.2) |

18.6 (65.5) |

16.9 (62.4) |

15.4 (59.7) |

13.9 (57.0) |

12.8 (55.0) |

12.5 (54.5) |

12.7 (54.9) |

13.6 (56.5) |

15.2 (59.4) |

17.1 (62.8) |

15.5 (59.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 16.2 (61.2) |

16.5 (61.7) |

16.0 (60.8) |

14.4 (57.9) |

13.1 (55.6) |

11.7 (53.1) |

10.6 (51.1) |

10.2 (50.4) |

10.3 (50.5) |

11.1 (52.0) |

12.6 (54.7) |

14.5 (58.1) |

13.1 (55.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 11.4 (52.5) |

4.2 (39.6) |

9.0 (48.2) |

8.2 (46.8) |

6.3 (43.3) |

4.8 (40.6) |

5.0 (41.0) |

3.0 (37.4) |

5.0 (41.0) |

6.2 (43.2) |

7.3 (45.1) |

9.2 (48.6) |

3.0 (37.4) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 29.0 (1.14) |

33.4 (1.31) |

55.1 (2.17) |

83.5 (3.29) |

150.5 (5.93) |

184.4 (7.26) |

130.5 (5.14) |

114.3 (4.50) |

80.2 (3.16) |

49.9 (1.96) |

35.7 (1.41) |

24.8 (0.98) |

971.3 (38.24) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 5.6 | 6.1 | 8.8 | 11.2 | 14.6 | 16.4 | 15.9 | 13.5 | 11.1 | 8.3 | 6.0 | 5.4 | 123.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 73 | 73 | 73 | 77 | 78 | 78 | 79 | 77 | 77 | 76 | 74 | 73 | 76 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 206.7 | 178.9 | 170.4 | 126.9 | 103.0 | 85.1 | 98.5 | 123.4 | 139.0 | 171.6 | 178.4 | 195.7 | 1,777.6 |

| Source 1: Dirección Meteorológica de Chile (humidity 1931–1960) | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: World Meteorological Organization (precipitation days 1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

Flora and fauna

The Fernandezian region is a floristic region which includes the Juan Fernández Islands archipelago. It is in the Antarctic floristic kingdom, but often also included within the Neotropical kingdom. As World Biosphere Reserves since 1977, these islands have been considered of maximum scientific importance because of the endemic plant families, genera, and species of flora and fauna. Out of 211 native plant species, 132 (63%) are endemic, as well as more than 230 species of insects.

Robinson Crusoe Island has one endemic plant family, Lactoridaceae. The Magellanic penguin is also found there. The Juan Fernández firecrown is an endemic and critically endangered red hummingbird, which is best known for its needle-fine black beak and silken feather coverage. The Masatierra petrel is named after the island's former name. The island (along with neighbouring Santa Clara) has been recognised as an Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International because it supports populations of Masatierra petrels, pink-footed shearwaters, Juan Fernandez firecrowns and Juan Fernandez tit-tyrants.

Robinson Crusoe Island, seen from CS Responder during work on a nuclear test ban hydroacoustic monitoring station in 2014

Robinson Crusoe Island, seen from CS Responder during work on a nuclear test ban hydroacoustic monitoring station in 2014

History

The island was first named Juan Fernandez Island after Juan Fernández, a Spanish sea captain and explorer who was the first to land there in 1574. It was also known as Más a Tierra. There is no evidence of an earlier discovery either by Polynesians, despite the proximity to Easter Island, or by Native Americans.

From 1681 to 1684, a Miskito man known as Will was marooned on the island. Twenty years later, in 1704, the sailor Alexander Selkirk was also marooned there, living in solitude for four years and four months. Selkirk had been gravely concerned about the seaworthiness of his ship, Cinque Ports (which ended up sinking very shortly after), and declared his wish to be left on the island during a mid-voyage restocking stop. His captain, Thomas Stradling, a colleague on the voyage of privateer and explorer William Dampier, was tired of his dissent and obliged. All Selkirk had left with him was a musket, gunpowder, carpenter's tools, a knife, a Bible, and some clothing. The story of Selkirk's rescue is included in the 1712 book A Voyage to the South Sea, and Round the World by Edward Cooke.

In an 1840 narrative, Two Years Before the Mast, Richard Henry Dana Jr. described the port of Juan Fernandez as a young prison colony. The penal institution was soon abandoned and the island again uninhabited before a permanent colony was eventually established in the latter part of the 19th century. Joshua Slocum visited the island between 26 April and 5 May 1896, during his solo global circumnavigation on the sloop Spray. The island and its 45 inhabitants are referred to in detail in Slocum's memoir, Sailing Alone Around the World.

World War I

During World War I, German Vice Admiral Maximilian von Spee's East Asia Squadron stopped and re-coaled at the island 26–28 October 1914, four days before the Battle of Coronel. While at the island, the admiral was unexpectedly rejoined by the armed merchant cruiser Prinz Eitel Friedrich, which he had earlier detached to attack Allied shipping in Australian waters. On 9 March 1915 SMS Dresden, the last surviving cruiser of von Spee's squadron after his death at the Battle of the Falklands, returned to the island's Cumberland Bay, hoping to be interned by the Chilean authorities. Caught and fired upon by a British squadron at the Battle of Más a Tierra on 14 March, the ship was scuttled by its crew.

2010 tsunami

On 27 February 2010 Robinson Crusoe Island was hit by a tsunami following a magnitude 8.8 earthquake. The tsunami was about 3 m (10 ft) high when it reached the island. Sixteen people were killed and most of the coastal village of San Juan Bautista was washed away. The only warning the islanders had came from 12-year-old girl Martina Maturana, who noticed the sudden drawback of the sea that forewarns of the arrival of a tsunami wave and saved many of her neighbours from harm.

Society

Robinson Crusoe had an estimated population of 843 in 2012. Most of the island's inhabitants live in the village of San Juan Bautista on the north coast at Cumberland Bay. Although the community maintains a rustic serenity dependent on the spiny lobster trade, residents employ a few vehicles, a satellite Internet connection and televisions. The main airstrip, Robinson Crusoe Airfield, is located near the tip of the island's southwestern peninsula. The flight from Santiago de Chile is just under three hours. A ferry runs from the airstrip to San Juan Bautista.

Tourists number in the hundreds per year. One activity gaining popularity is scuba diving, particularly on the wreck of the German light cruiser Dresden, which was scuttled in Cumberland Bay during World War I.

Maya statue hypothesis

A History Channel documentary was filmed on Robinson Crusoe Island. It aired on 3 January 2010 and showed two rock formations that Canadian explorer Jim Turner claimed were badly degraded Mayan statues. With no other sign of any pre-Columbian human presence on the island, however, the program has been criticized as lacking in scientific credibility.

See also

References

- ^ Torres Santibáñez, Hernán; Torres Cerda, Marcela (2004). Los parques nacionales de Chile: una guía para el visitante (in Spanish). Editorial Universitaria. p. 49. ISBN 978-956-11-1701-3.

- ^ "Censos de poblacion y vivienda". Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas (2012). Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ^ Severin, Tim (2002). In Search of Robinson Crusoe. New York: Basic Books. pp. 23–24. ISBN 978-046-50-7698-7.

- Severin, Tim (2002). In Search of Robinson Crusoe. New York: Basic Books. pp. 17–19. ISBN 978-046-50-7698-7.

- Little, Becky (28 September 2016). "Debunking the Myth of the 'Real' Robinson Crusoe". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 28 September 2016. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- "Parque Nacional Archipiélago de Juan Fernández" Corporacion Nacional Forestal de Chile (2010). Retrieved 27 May 2010. Archived 23 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "Datos Normales y Promedios Históricos Promedios de 30 años o menos" (in Spanish). Dirección Meteorológica de Chile. Archived from the original on 23 May 2023. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- "Temperatura Histórica de la Estación Juan Fernández, Estación Meteorológica. (330031)" (in Spanish). Dirección Meteorológica de Chile. Archived from the original on 23 May 2023. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1981–2010". World Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ "Forest on Robinson Crusoe Island". Wondermondo (2012). Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- Hogan, C. Michael (2008). Magellanic Penguin Archived 7 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine. GlobalTwitcher. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- "Islas Robinson Crusoe and Santa Clara". BirdLife Data Zone. BirdLife International. 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- "Welcome Back HA03—Robinson Crusoe Island" Archived 9 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (2014). Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ^ Anderson, Atholl; Haberle, Simon; Rojas, Gloria; Seelenfreund, Andrea; Smith, Ian & Worthy, Trevor (2002). An Archeological Exploration of Robinson Crusoe Island, Juan Fernandez Archipelago, Chile Archived 12 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine. New Zealand Archaeological Association.

- Rogers, Woodes (1712). A Cruising Voyage Round the World: First to the South-seas, Thence to the East-Indies, and Homewards by the Cape of Good Hope. London: A. Bell and B. Lintot. pp. 125–126.

- Dana, Richard Henry (1840). Two Years Before the Mast: A Personal Narrative of Life at Sea. New York: Harper & Brothers. pp. 28–32.

- Coulter, John (1845). Adventures in the Pacific: With Observations on the Natural Productions, Manners and Customs of the Natives of the Various Islands. London: Longmans, Brown & Co. pp. 32–33.

- Slocum, Joshua (2012). Sailing Alone Around the World. Oxford: Beaufoy Publishing. pp. 77–82. ISBN 978-190-67-8034-0.

- ^ Delgado, James P. (2004). Adventures of a Sea Hunter: In Search of Famous Shipwrecks. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre. pp. 168–174. ISBN 978-1-926685-60-1.

- Ricketts, Colin (17 August 2011). "Tsunami warning came too late for Robinson Crusoe Island". Earth Times. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ Bodenham, Patrick (9 December 2010). "Adrift on Robinson Crusoe Island, the forgotten few". The Independent. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- Harrell, Eben (2 March 2010). "Chile's president: Why did tsunami warnings fail?". Time Magazine. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- ^ Gordon, Nick (14 December 2004). "Chile: The real Crusoe had it easy". The Telegraph. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- "Armageddon: Apocalypse Island". A&E Television Networks (2009). Retrieved 18 October 2012. Archived 13 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Lowry, Brian (26 June 2010). "Wackadoodle Demo Widens". Variety. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

Further reading

- Perez Ibarra, Martin (2014). Señales del Dresden (in Spanish). Chile: Uqbar Editores. ISBN 978-956-9171-36-9. The story of German light cruiser Dresden which was scuttled in this island during World War I.

External links

- Routes around the island with descriptions and photos of sights

- Robinson Crusoe Island satellite map with anchorages and other ocean-related information

- A detailed map of the island showing footpaths and walkers' refuges

- Juan Fernandez photo gallery with images of landscapes, flora and fauna on the island

- "Robinson Crusoe, Moai Statues and the Rapa Nui: the Stories of Chile’s Far-Off Islands" Archived 30 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine from Sounds and Colours

- A digital field trip to Robinson Crusoe Island by Goat Island Images

- "Chasing Crusoe", a multimedia documentary about the island

| Eastern Pacific islands | |

|---|---|

| Oceanic islands located between Polynesia and the Americas, sorted by country, from north to south (excluding continental islands) | |

| Mexico | |

| France | |

| Costa Rica | |

| Colombia | |

| Ecuador | |

| Chile | |

| Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe | |

|---|---|

| Characters | |

| Sequel novels | |

| Films |

|

| Film variations |

|

| Television |

|

| Literature | |

| Other | |