| Revision as of 06:53, 7 July 2024 editRahammz (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users29,444 editsNo edit summaryTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 09:45, 6 November 2024 edit undoJevansen (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers3,277,198 edits Moving from Category:19th-century male writers to Category:19th-century French male writers using Cat-a-lot | ||

| (8 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|French journalist and author}} | {{short description|French journalist and author (1832–1885)}} | ||

| {{Infobox writer | {{Infobox writer | ||

| | name = Jules Vallès | | name = Jules Vallès | ||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Jules Vallès''' ( |

'''Jules Vallès''' (1832–1885) was a French ], author, and ] political activist. | ||

| ==Early life== | |||

| Vallès was born in ], ] as '''Jules Vallez'''. His father was a supervisor of studies (''pion''), later a teacher, and unfaithful to Jules' mother. Jules was a brilliant student. The ] found him participating in protests in Nantes where his father had been assigned to teach. It was during this period that he began to align himself with the budding socialist movement. After being sent to Paris to prepare for his entrance into ] (1850) he neglected his studies altogether. He took part in the uprising against ] during the ], fighting together with his friend ] at one of the rare barricades on December 2. Vallès later fled to Nantes, where his father had him committed to a mental institution.(ref 1978, Bernard Noël e.a.) Thanks to help from his friend Antoine Arnould, he managed to escape a few months later. He returned to Paris, where he joined the staff of '']'', and became a regular contributor to the other leading journals. | |||

| ] | |||

| In 1853 he was arrested for conspiring against ], but was later freed due to a lack of evidence. He lived in poverty, writing ] for ] (the ] page of the Figaro even, until fired for his bias against ]). It was under these conditions that he wrote his first book ''L'Argent'' (1857). ''Les Amours de Paille'' (1859), a comedy written in collaboration with Poupart-Davyl, was a failure.(ref 1990 ]) At the insistence of his colleague ] he found an administrative job issuing birth certificates for the ] town hall.(1860) He became a steady friend of ] and began to live with his lover, Joséphine Lapointe. He decided to become a ''pion'' himself in Caen, but was quickly discharged. Back in Paris, his friend Hector Malot helped him reacquire his job at the town hall. In 1864–1865 he wrote literary criticism for ''Progrès de Lyon''. In 1865 he collected much of his newspaper work in a book ''Les Refractaires'' that sold well. A second collection in 1866 ''La Rue'' had less success. In 1867 he started the newspaper ''La Rue'', which was later suppressed by the government after a mere eight months of publication. | |||

| ==Republican opposition== | |||

| ].]] | |||

| By this time he was a recognized leader of the republican opposition against the ]. In 1865 he had lost his job at Vaugirard for a speech he gave against the capitalist society of the Second Empire, eluding the censorship by advertising a talk on ]. In 1868 he was twice convicted for press crimes: one month in prison for criticizing the police, two months for criticising the Empire. At the elections of 1869 he was the candidate to the left opposing the moderate ]. | |||

| He lost the election and went to work for '']'' the newspaper of ], meanwhile contributing to '']'' of ]. | |||

| In the summer of 1869 members of several "Chambres syndicales" of Paris workers rented a space at nr 6, Place de la Corderie to hold the meetings of the "Chambre fédérale des Sociétés ouvrières", the "Conseil fédéral des sections parisiennes de l'Internationale", and as the events unfolded the "Comité central républicain des Vingt Arrondissements" (1870) and the "Comité central de la Garde nationale". (March 1871) It was to be the very organisational center of the Paris Commune. Its activities are prominently described in ''Jacques Vingtras:L'Insurgé''. Jules Vallès had friends and connections among all the tendencies represented: ], ], ] and while he was himself independent of all of them he represented the active force of each. He was well known and well liked and when in 1870 the ] spread the rumour that the candidates of the extreme left including Vallès had been on the payroll of the Imperial police at the 1869 elections, the Corderie gave him a vote of confidence. | |||

| ==1870== | |||

| The year leading up to the Paris Commune began with the assassination of ] (January 10). Jules Vallès and ] found themselves at the head of the mass manifestation at Victor Noir's funeral (January 12); Rochefort interceding with the ] ] who wanted to begin the anti-imperial insurrection there and then. | |||

| In July ] embroiled France in the ]. Vallès was among the very few anti-war protesters, and was jailed as a consequence (August 6). On September 2 Napoleon III ] and was captured. On September 4 the ] was proclaimed and the ] installed.(]) Vallès was freed from prison and took part in the popular manifestations leading to the formation of the "Comité central républicain des Vingt arrondissements" of which he -like many other leaders of the Paris Commune- became a prominent member; heading even, for a while, a battalion of the "Garde nationale". On September 18 the Prussians laid siege on a Paris unwilling to accept defeat and calling for all out war by the provinces. On October 5, Flourens marched the five battalions "Garde nationale" of Belleville in disciplined military fashion to the Hôtel de Ville to show preparedness. On October 31, a first blanquist uprising erupted at Belleville with Vallès in command of his battalion occupying the town hall of la Vilette. The uprising failed and Vallés had to go in hiding. | |||

| ==1871 and the Paris Commune== | |||

| At the start of 1871 Jules Vallès at the initiative of the "Comité central républicain des Vingt arrondissements" edited the "Affiche Rouge" posted on January 7 : the first call for the proclamation of the ]. On March 11, Vallès was judged for his participation in the October plot. He escaped from the tribunal after hearing himself condemned to six months in prison, and his ''Le Cri du Peuple'' which he had started on February 22, banned from further appearance. On March 18, the Commune was officially proclaimed; March 21, ''Le Cri du Peuple'' reappeared to become one of the most successful newspapers of the Commune - together with '']''. On March 26 he was elected by the 15th district (Vaugirard: 4,403 votes of 6,467 voters) to the Conseil de la Commune; nominated to the commission of Public Education (March 29). | |||

| Although quick to the march when it came to demand individual liberties Jules Vallès was also a voice for opposite opinion: he claimed his reserve when the separation of Church and State was proclaimed (April 2), opposed the suppression of the "reactionary" newspapers (April 26), he voted against the institution of the Comité de Salut with its ] tendencies, and together with 22 other prominent members - among them his old friend Arnould, the painter ], ], Varlin...he signed the manifest of the minority which he published in his newspaper. (May 15) | |||

| On May 21 the ] troops entered Paris through the porte Saint-Cloud while Vallès, among minority members reintegrated in the Commune, presided over its last session - in judgement over ] and his failure to hold the fort of Issy (and with Vallès in sympathy with the defendant). During the ] (May 21 – May 28) he took part in the fighting, making a last stand in the rue de Paris (now rue de Belleville) on May 28 with his steadfast friend Gabriel Ranvier. Together they managed to escape the fusillades and went into exile. In 1872 both were given death sentences ''in absentia''. | |||

| ==''Le Cri du Peuple''== | |||

| Jules Vallès' newspaper ''Le Cri du Peuple -Journal politique quotidien, 10 centimes'' was among the most successful of the Paris Commune. Only ''Journal Officiel'', ''La Commune'', ''Le Mot d'Ordre'', ''le Père Duchêne'' and ''le Vengeur'' appear to have been contending rivals. Its style has been described as "simple firmity, sympathetic authority, reflected realism due to a conviction rendered spontaneously lyrical by its sincerity" by Bernard Noël, who read through the entire press produced in Paris 1871 for his ''Dictionnaire de la Commune'' (1978). | |||

| After the paper was banned by General ] (1871) on March 11 (nr18), it was reissued on March 21 (nr19) and was published without interruption until Tuesday May 23 (nr83). | |||

| Its collaborators were: Casimir Bouis, Jean-Baptiste Clément, Pierre Denis, and Charles Rochat, with occasional articles by Henry Bauer (1851–1915), Courbet, and ]. | |||

| Because of the communal tasks taken up by most other editors, the work of chief editor in practice fell to ], who set the tone with accent on the ]ian ideology. He represented his views in the ], of which he was a member: recognition of individual liberties, suppression of the permanent army and police, "]" and free education, entire benefit of work produced, autonomy of the commune -or ], ], ], and ]. | |||

| ==Jacques Vingtras and exile== | |||

| The foregoing events were all chronicled in the three parts of Jules Vallès major work: ''Jacques Vingtras'': ''L'Enfant'', ''Le Bachelier'', ''L'insurgé''. Vallès wrote ''Jacques Vingtras'' during his bitter exile following the ]. | |||

| Vallès went to live in exile in London. In 1875 Vallès, in the absence of his companion Joséphine Lapointe, had an affair with another woman. She bore his daughter, but when the girl died at 10 months, Vallès quickly separated from the mother. This period in 1876 marked his complete destitution. His friend ] negotiated the publication of his novel ''Jacques Vingtras - L'Enfant'' as a serial ('']'') in the newspaper ''Le Siècle'' (June–August 1878). The extreme realism combined with corrosive irony resulted in a negative public reaction and dropping of the project. In January–May 1879 ''Le Bachelier'' appeared in ''La Révolution française'' under the title ''Les Mémoires d'un révolté''. The first book ''Jacques Vingtras - L'Enfant, Le Bachelier'' was published by Charpentier and signed 'Jean La Rue' (Vallès had tried to start the paper ''La Rue'' in Brussels that same year - a failure). | |||

| In 1879–1880 he came to know ], whose friendship secured the final draft of ''L'Insurgé''. She persuaded Charpentier to publish the book in 1886, after Vallès's death. | |||

| Among the French authors most influenced by the racy, concise and ironic style of Jules Vallès is ], author of the child's portrait ''Poil de Carotte''. ] at least recognised the quality of the prose of her friend in his writings (see: Jules Renard ''Journal 1897-1910''). | |||

| ==Amnesty and last days== | |||

| After his liberation on 11 June 1879, ] had managed to get support from ] for the plight of the many thousand destitutes who had been implicated in the ]. On 11 July 1880 the government issued a general pardon, in the wake of which Vallès was able to return to Paris. There he renewed his journalism with vigour. In 1881 he was among the 100,000 mourners in procession for Blanqui's funeral. | |||

| ] | |||

| In 1883 he was entirely successful in restarting ''Le Cri du Peuple'' as a voice for ] and ] ideas. At the same time he became increasingly ill with ]. During a health crisis in November 1884, he was taken to the house of doctor Guebhard and his secretary ]. He assigned ] to be the executor of his will and died on 14 February 1885.{{sfn|Chisholm|1911}} | In 1883 he was entirely successful in restarting ''Le Cri du Peuple'' as a voice for ] and ] ideas. At the same time he became increasingly ill with ]. During a health crisis in November 1884, he was taken to the house of doctor Guebhard and his secretary ]. He assigned ] to be the executor of his will and died on 14 February 1885.{{sfn|Chisholm|1911}} | ||

| His funeral was also a major public event, attracting a procession of some 60,000 following the coffin to ].<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=cDGdDwAAQBAJ&q=Jules+Vall%C3%A8s+funeral&pg=PA57|title=Revolutionary Thought after the Paris Commune, 1871-1885|last=Nicholls|first=Julia|date=2019-07-18|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-1-108-49926-2|language=en}}</ref> | His funeral was also a major public event, attracting a procession of some 60,000 following the coffin to ].<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=cDGdDwAAQBAJ&q=Jules+Vall%C3%A8s+funeral&pg=PA57|title=Revolutionary Thought after the Paris Commune, 1871-1885|last=Nicholls|first=Julia|date=2019-07-18|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-1-108-49926-2|language=en}}</ref> | ||

| == |

==References== | ||

| {{reflist}} | {{reflist}} | ||

| == |

==Bibliography== | ||

| * Alain Viala: Préface et commentaires à Jules Vallès "''Jacques Vingtras - L'Enfant''" Paris: Presses Pocket, 1990 | * Alain Viala: Préface et commentaires à Jules Vallès "''Jacques Vingtras - L'Enfant''" Paris: Presses Pocket, 1990 | ||

| * Marie-Claire Bancqaert: Préface et notes à Vallès "''L'Insurgé''" Paris: Collection Folio/Gallimard, 1979 | * Marie-Claire Bancqaert: Préface et notes à Vallès "''L'Insurgé''" Paris: Collection Folio/Gallimard, 1979 | ||

| * Bernard Noël: "''Dictionnaire de la Commune''" Paris: Champs/Flammarion, 1978 | * Bernard Noël: "''Dictionnaire de la Commune''" Paris: Champs/Flammarion, 1978 | ||

| * {{cite EB1911|wstitle=Vallès, Jules|volume=27 |

* {{cite EB1911|wstitle=Vallès, Jules|volume=27|page=863}} | ||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{commons |

{{commons}} | ||

| * {{Gutenberg author |id=5641| name=Jules Vallès}} | * {{Gutenberg author |id=5641| name=Jules Vallès}} | ||

| * {{Internet Archive author |sname=Jules Vallès |sopt=w}} | * {{Internet Archive author |sname=Jules Vallès |sopt=w}} | ||

| Line 108: | Line 60: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| {{journalist-stub}} | |||

Latest revision as of 09:45, 6 November 2024

French journalist and author (1832–1885)| Jules Vallès | |

|---|---|

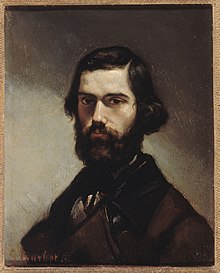

Jules Vallès by Gustave Courbet Jules Vallès by Gustave Courbet | |

| Born | Jules Vallez (1832-06-11)11 June 1832 Le Puy-en-Velay, Haute-Loire, France |

| Died | 14 February 1885(1885-02-14) (aged 52) Paris, France |

| Occupation | Journalist and author |

| Nationality | French |

| Signature | |

| |

Jules Vallès (1832–1885) was a French journalist, author, and left-wing political activist.

In 1883 he was entirely successful in restarting Le Cri du Peuple as a voice for libertarian and socialist ideas. At the same time he became increasingly ill with diabetes. During a health crisis in November 1884, he was taken to the house of doctor Guebhard and his secretary Séverine. He assigned Hector Malot to be the executor of his will and died on 14 February 1885.

His funeral was also a major public event, attracting a procession of some 60,000 following the coffin to Père Lachaise Cemetery.

References

- Chisholm 1911.

- Nicholls, Julia (2019-07-18). Revolutionary Thought after the Paris Commune, 1871-1885. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-49926-2.

Bibliography

- Alain Viala: Préface et commentaires à Jules Vallès "Jacques Vingtras - L'Enfant" Paris: Presses Pocket, 1990

- Marie-Claire Bancqaert: Préface et notes à Vallès "L'Insurgé" Paris: Collection Folio/Gallimard, 1979

- Bernard Noël: "Dictionnaire de la Commune" Paris: Champs/Flammarion, 1978

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Vallès, Jules" . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 863.

External links

- Works by Jules Vallès at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Jules Vallès at the Internet Archive

- Vallès in Le Cri du Peuple (English)

- 1867 Caricature of Jules Vallès by André Gill

- The Child by Jules Vallés new edition from New York Review Books

- (in French) Jacques Vingtras trilogy, audio version Archived 2021-06-12 at the Wayback Machine

This article about a journalist is a stub. You can help Misplaced Pages by expanding it. |

- 1832 births

- 1885 deaths

- People from Le Puy-en-Velay

- French anarchists

- French socialists

- French newspaper founders

- Communards

- Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery

- Members of the International Workingmen's Association

- 19th-century French journalists

- French male journalists

- 19th-century French novelists

- French male novelists

- 19th-century French businesspeople

- 19th-century French male writers

- Journalist stubs