| Revision as of 18:40, 20 April 2007 editAndrew c (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users31,890 edits Undid revision 124420911 by 207.212.143.230 (talk) no source, not europe← Previous edit |

Latest revision as of 10:13, 6 April 2024 edit undoLtbdl (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users4,456 edits Added {{More footnotes needed}} tagTag: Twinkle |

| (102 intermediate revisions by 77 users not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

|

|

{{Short description|none}} |

|

The '''history of elephants in Europe''' dates back to the ]s, when ]s (various species of prehistoric ]) roamed the northern parts of the Earth, from ] to ]. There was also the ] of Cyprus (''Palaeoloxodon cypriotes''), Sicily-Malta (''Palaeoloxodon falconeri'') and mainland (''Palaeoloxodon antiquus''). However, these became extinct several thousand years ago, and subsequently the presence of elephants in Europe is only due to importation of these animals. |

|

|

|

{{More footnotes needed|date=April 2024}} |

|

] ] (205-171 BC), wearing the scalp of an elephant, symbol of his conquest of India.]] |

|

|

|

], believed to be ]. Spain, 11th century.]] |

| ⚫ |

Europeans first came in contact with elephants in 327 BC, when ] descended into India from the ], but Alexander was quick to adopt them. Four elephants guarded his tent, and shortly after his death his associate Ptolemy issued coins showing Alexander in the elephant headdress that became a royal emblem also in the Hellenized East. Aristotle depended on first-hand information for his account of elephants, but like most Westerners he believed the animals live for two hundred years. Roman scouts in the royal Syrian parks shortly before the last of the ]s fell to Rome had orders to hamstring every elephant they could capture, and while elephants performed in the circuses of Rome, ]'s war elephants in the mid 4th century numbered in the hundreds (Fox 1973 p 338). |

|

|

|

], Part II, Parker Library, MS 16, fol. 151v]] |

|

|

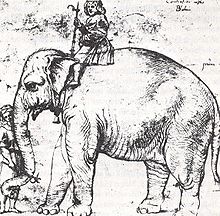

], after ], c. 1514.]] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The '''history of elephants in Europe''' dates back to the time of the ], but previously, during the ], relatives of elephants were spread across the globe, including ]. ]s roamed the northern parts of the Earth, from ] to ]. The ] of mainland Europe principally inhabited the ], but reached the rest of Europe during ]. While it went extinct during the last Ice Age, ] such as the '']'', the ], the ''Naxos dwarf elephant'' and the ''Rhodes dwarf elephant'' survived longer, and the last Mediterranean elephant species survived on ] until about 4000 years ago.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Elephas tiliensis n. sp. from Tilos island (Dodecanese, Greece) |url=http://www.hellenjgeosci.geol.uoa.gr/42/19-32.pdf}}</ref> Subsequently the presence of actual elephants in Europe was only due to importation of these animals. |

| ⚫ |

Elephants disappeared from Europe after the Roman Empire. As exotic and expensive animals, they were exchanged as presents between European rulers, who exhibited them as luxury pets, beginning with ]'s gift of an elephant to ]. |

|

| ⚫ |

<!-- An example of the lack of presences of elephants in Europe is that the ] representing an elephant (''pīl'' in Persian, ''al-fil'' in Arabic) became the meaningless ''alfil'' in Castilian and '']'' in English. --but it remained "elephant" in Russian, so what's the point? --> |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

== Overview == |

|

|

{{See also|Elephant#Etymology}} |

|

⚫ |

Europeans came in contact with live elephants in 327 BC, when ] descended into ] from the ], but Alexander was quick to adopt them. Four elephants guarded his tent, and shortly after his death his associate Ptolemy issued coins showing Alexander in the elephant headdress that became a royal emblem also in the Hellenized East. Aristotle depended on first-hand information for his account of elephants, but like most Westerners he believed the animals live for two hundred years. Roman scouts in the royal Syrian parks shortly before the last of the ]s fell to Rome had orders to ] every elephant they could capture, and while elephants performed in the ], ]'s war elephants in the mid-4th century numbered in the hundreds (Fox 1973 p 338). |

|

|

|

|

⚫ |

Elephants largely disappeared from Europe after the Roman Empire. As exotic and expensive animals, they were exchanged as presents between European rulers, who exhibited them as luxury pets, beginning with ]'s gift of an elephant to ]. |

|

⚫ |

<!-- An example of the lack of presences of elephants in Europe is that the ] representing an elephant (''pīl'' in Persian, ''al-fil'' in Arabic) became the meaningless ''alfil'' in Castilian and '']'' in English. --but it remained "elephant" in Russian, so what's the point? Nobody knows. --> |

|

|

|

|

|

== Examples == |

|

Historical accounts of elephants in Europe include: |

|

Historical accounts of elephants in Europe include: |

|

|

|

|

|

* The 20 elephants in the army of ], which landed at ] in 280 BC for the first ], recorded in ]'s ''Lives'', ], ] and ]. "The most notable elephant in Greek history, called Victor, had long served in Pyrrhus's army, but on seeing its ] dead before the city walls,it rushed to retrieve him: hoisting him defiantly on his tusks, its took wild and indiscriminate revenge for the man it loved, trampling more of its supporters than its enemies" (Fox 1973). Coins of Tarentum after this battle also featured elephants. |

|

* The 20{{efn|Contemporary accounts report a significantly higher number of elephants: ] records 142 "or, as some say", 140; in the ] and by ], the number is 120; ] says that they were "about a hundred".<ref>{{cite web|title=Pliny the Elder, ''The Natural History'', BOOK VIII. THE NATURE OF THE TERRESTRIAL ANIMALS., CHAP. 6. (6.) —WHEN ELEPHANTS WERE FIRST SEEN IN ITALY.|url=https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=urn:cts:latinLit:phi0978.phi001.perseus-eng1:8.6#note5|website=www.perseus.tufts.edu}}</ref>}} elephants in the army of ], which landed at ] in 280 BC for the first ], recorded by ]'s (in ]), ], ] and ]. "The most notable elephant in Greek history, called Victor, had long served in Pyrrhus's army, but on seeing its ] dead before the city walls, it rushed to retrieve him: hoisting him defiantly on his tusks, it took wild and indiscriminate revenge for the man it loved, trampling more of its supporters than its enemies".<ref> |

|

|

{{cite book |

|

|

|

|

|

| last = Lane Fox |

|

|

| first = Robin |

|

|

| authorlink = Robin Lane Fox |

|

|

| title = Alexander the Great |

|

|

| url = https://books.google.com/books?id=i1-b90sBNH4C |

|

|

| year = 1973 |

|

|

| publisher = Penguin |

|

|

| isbn = 9780140088786 |

|

|

| page = 339 |

|

|

| quote = The most notable elephant in Greek history, called Victor, had long served in Pyrrhus's army, but on seeing its mahout dead before the city walls, it rushed to retrieve him: hoisting him defiantly on his tusks, it took wild and indiscriminate revenge for the man it loved, trampling more of its supporters than its enemies in the process.}}</ref> Coins of Tarentum after this battle also featured elephants. |

|

* The 37 elephants in ]'s army that crossed the ] in October/November 218 BC during the ], recorded by ]. |

|

* The 37 elephants in ]'s army that crossed the ] in October/November 218 BC during the ], recorded by ]. |

|

|

* The first historically recorded elephant in northern Europe was brought by ] ] during the ] in AD 43 to the British capital of ]. At least one skeleton with flint weapons that has been found in England was initially misidentified as this elephant, but later dating proved it to be a ] skeleton from the ].<ref>{{cite book|title=Mammoths: Giants of the Ice Age|first1= Adrian |last1=Lister|first2= Paul G. |last2=Bahn|date= October 2007 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_6WBlUwYPa8C&pg=PA116|page= 116|publisher= Frances Lincoln |isbn= 9780711228016 }}</ref> |

|

|

|

|

⚫ |

* ], the ] which ] gave to ] in 797 or 802. The animal died in 810, of pneumonia. |

|

* The first historically recorded elephant in northern Europe was the animal brought by ] ], during the ] in AD 43, to the British capital of ]. |

|

|

|

* The '']'' record that King ] gave a large, exotic animal to ] in 1105, possibly an elephant but more probably a ]. (''Annals of Innisfallen'', s.a. 1105; ], ''Scotland: The Making of the Kingdom'' (1975), p. 128) |

|

|

|

|

|

*The ] presented to ] by ] in 1229. |

| ⚫ |

* ], the ] given to ] by Harun ar-Rashid in 797 or 802. The animal died in 810, of pneumonia. |

|

|

⚫ |

* The elephant given by ] to ], for his menagerie in the ] in 1255 (see: ]). Drawn from life by the historian ] for his '']'', it was the first elephant to be seen in England since Claudius' war elephant. Matthew Paris' original drawing appears in his ], on display in the ] of ]. The bestiary explains that while in residence at the Tower of London, the elephant enjoyed a diet of prime cuts of ] and expensive red wine, and is claimed to have died in 1257 from drinking too much wine. The accompanying text reveals that at the time, Europeans believed that elephants did not have ]s and so were unable to get up if they fell over (the bestiary contains a drawing depicting an elephant on its back being dragged along the ground by another elephant, with a caption stating that elephants lacked knees – compare ]). Europeans also interpreted descriptions of ]s to mean that Indian elephants were capable of carrying actual stone ]s on their backs, albeit only big enough to be garrisoned by three or four men; note that turreted ] did exist, though not ones made of stone. A carving of the elephant can be found on a contemporary miserichord in ]. This animal may be the inspiration for the heraldic device ']', the arms of the Cutlers' Company of London, a guild founded in the 13th century responsible for making scissors, knives and the like. Its heraldry survived in an 18th-century pub-sign that in turn gave its name to a largely modern ] in South ]. |

|

|

|

|

⚫ |

* In the 1470s King ] founded a chivalric order, the '']'', and had it confirmed by ]. The order takes its name from the battle elephants which symbolized the Christian Crusades. {{As of|2003|alt=Today}}, it continues to be awarded under statutes established by king ] in 1693, amended in 1958 to permit the admission of women to the order. |

|

* ]. Spain, 11th century.]] ] captured an elephant in the Holy Land and used it in the capture of ] in 1214. |

|

|

|

|

| ⚫ |

* The elephant given by ] to ], for his menagerie in the ] in 1255 (see: ]). Drawn from life by the historian ] for his ], it was the first elephant to be seen in England since Claudius' war elephant. Matthew Paris' original drawing can be found in his ], on display in the ] of ]. The bestiary explains that while in residence at the Tower of London, the elephant enjoyed a diet of prime cuts of ] and expensive red wine, and is claimed to have died in 1257 from drinking too much wine. The accompanying text reveals that at the time, Europeans believed that elephants did not have ]s and so were unable to get up if they fell over (the bestiary contains a drawing depicting an elephant on its back being dragged along the ground by another elephant, with a caption stating that elephants lacked knees). Europeans also interpreted descriptions of ]s to mean that Indian elephants were capable of carrying actual stone ]s on their backs, albeit only big enough to be garrisoned by three or four men. A carving of the elephant can be found on a contemporary miserichord in ]. This animal may be the inspiration for the heraldic device 'Elephant and Castle,' the arms of the Cutlers' Company of London, a guild founded in the 13th Century responsible for making scissors, knives and the like. Its heraldry survived in an 18th century pub sign that in turn gave its name to a largely modern ] in South ]. |

|

|

|

|

| ⚫ |

* In the 1470s, King ] founded a chivalric order, the '']'', and had it confirmed by ]. The order is named for the battle elephants which symbolized the Christian Crusades. ], it continues to be awarded under statutes established by king ] in 1693, amended in 1958 to permit the admission of women to the order. |

|

|

|

|

|

* The elephant given by ] to ] about 1477. |

|

* The elephant given by ] to ] about 1477. |

|

⚫ |

* The merchants of ] presented ] with an elephant in 1497. |

|

⚫ |

* ], a present from the ] king ] to ]. Travelling from Spain in 1551, it arrived in Vienna in 1552, but died in 1554. |

|

⚫ |

* ], or ''Annone'', was a ] presented by king ] to ] on the occasion of his coronation in 1514. He died in 1518, probably of an intestinal obstruction misdiagnosed as angina, with Pope Leo at his side. His story is told in ]'s ''The Pope's Elephant'' (Nashville: Sanders 1998). At the ], in the garden facing the loggia, the Elephant Fountain designed by ] depicts "Annone", whose tomb was designed by ] himself. |

|

⚫ |

*], a female elephant from ] that became famous in early 17th-century Europe, touring through many countries demonstrating circus tricks, and sketched by ] and ]. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

==References== |

| ⚫ |

* The merchants of ] presented ] with an elephant in 1497. |

|

|

|

;Footnotes |

|

|

|

|

|

{{notelist}} |

| ⚫ |

* ] was a present from the ] king ] to ]. Travelling from Spain in 1551, it arrived un Vienna in 1552, but died in 1554. |

|

|

|

;Sources |

|

|

|

|

|

{{reflist}} |

| ⚫ |

* ], or ''Annone'', was a ] presented by king ] to ] on the occasion of his coronation in 1514. He died, probably of an intestinal obstruction misdiagnosed as angina, with Pope Leo at his side in 1518. His story is told in ]'s ''The Pope's Elephant'' (Nashville: Sanders 1998). At the ], in the garden facing the loggia, the Elephant Fountain designed by ] depicts "Annone", whose tomb was designed by ] himself. |

|

|

⚫ |

* Saurer, Karl and Elena M.Hinshaw-Fischli. ''They Called him Suleyman: The Adventurous Journey of an Elephant from the Forests of ] to the Capital of Vienna in the middle of the sixteenth Century'', collected in ''Maritime Malabar and The Europeans'', edited by K. S. Mathew, Hope India Publications: Gurgaon, 2003 {{ISBN|81-7871-029-3}} |

|

|

|

|

⚫ |

*Robin Lane Fox, 1974. ''Alexander the Great''. Chapter 24 contains an excursus on Alexander and the elephant in Europe, |

| ⚫ |

*], a female elephant from ] that became famous in early 17th century Europe, touring through many countries demonstrating circus tricks, and sketched by ] and ]. |

|

|

|

*''The Story of Süleyman. Celebrity Elephants and other exotica in Renaissance Portugal'', Annemarie Jordan Gschwend, Zurich, Switzerland, 2010, {{ISBN|978-1-61658-821-2}} |

|

|

|

|

|

*{{cite book |first=Howard Hayes |last=Scullard |title=The Elephant in the Greek and Roman World |location=London |publisher=Thames and Hudson |year=1974 |isbn=0-500-40025-3 }} |

|

==See also== |

|

|

* ] |

|

|

* ] |

|

|

* ] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

==External links== |

|

==External links== |

|

* |

|

* |

|

* |

|

* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

{{Elephants}} |

|

==Reference== |

|

| ⚫ |

"They Called him Suleyman: The Adventurous Journey of an Elephant from the Forests of ] to the Capital of Vienna in the middle of the sixteenth Century", Karl Saurer & Elena M.Hinshaw-Fischli, collected in ''Maritime Malabar and The Europeans'', edited by K. S. Mathew, Hope India Publications: Gurgaon, 2003 ISBN 81-7871-029-3 |

|

| ⚫ |

*Robin Lane Fox, 1974. ''Alexander the Great''. Chapter 24 contains an excursus on Alexander and the elephant in Europe, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

] |

|

] |

Elephants largely disappeared from Europe after the Roman Empire. As exotic and expensive animals, they were exchanged as presents between European rulers, who exhibited them as luxury pets, beginning with Harun ar-Rashid's gift of an elephant to Charlemagne.