| Revision as of 18:07, 6 May 2007 view source69.22.249.79 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 19:31, 30 November 2024 view source Thebiguglyalien (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, New page reviewers19,557 edits →Secular–religious status quo: adding citation per Talk:Religion in Israel#Extended-confirmed-protected edit request on 7 November 2024Tag: 2017 wikitext editor | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|none}} <!-- "none" is a legitimate description when the title is already adequate; see ] --> | |||

| {{Israelis}} | |||

| {{pp-30-500|small=yes}} | |||

| ] is the only country in which ] is the ] of the majority of citizens. According to the country's ], in 2005 the population was 76.1% Jewish, 16.2% ], 2.1% ], and 1.6% ], with the remaining 3.9% (mainly immigrants from the former ]) not classified by religion.<ref name="CBS 2.1">{{cite book|title=Statistical Abstract of Israel 2006 (No. 57)|publisher=]|url=http://www1.cbs.gov.il/reader/shnatonenew_site.htm|year=2006|chapter=Table 2.1 — Population, by Religion and Population Group|chapterurl=http://www1.cbs.gov.il/shnaton57/st02_01.pdf}}</ref> | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=June 2019}} | |||

| {{Pie chart | |||

| |thumb = right | |||

| |caption = Religion in Israel (2016)<ref>{{Cite web |title=Israel's Religiously Divided Society |work=Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project |date=8 March 2016 |access-date=23 February 2020 |url= https://www.pewforum.org/2016/03/08/israels-religiously-divided-society/ }}</ref> | |||

| |label1 = ]–'']'' | |||

| |value1 = 33.1 | |||

| |color1 = Azure | |||

| |label2 = Judaism–'']'' | |||

| |value2 = 24.3 | |||

| |color2 = LightBlue | |||

| |label3 = Judaism–'']'' | |||

| |value3 = 8.8 | |||

| |color3 = Blue | |||

| |label4 = Judaism–'']'' | |||

| |value4 = 7.3 | |||

| |color4 = DarkBlue | |||

| |label5 = ] | |||

| |value5 = 18.1 | |||

| |color5 = Green | |||

| |label6 = ] | |||

| |value6 = 1.9 | |||

| |color6 = Red | |||

| |label7 = ] | |||

| |value7 = 1.6 | |||

| |color7 = LimeGreen | |||

| |label8 = Others and unclassified | |||

| |value8 = 4.8 | |||

| |color8 = Gray | |||

| }}'''Religion in Israel''' is manifested primarily in ], the ] of the ]. The ] declares itself as a "]" and is the only country in the world with a Jewish-majority population (see ]).{{sfn|Beit-Hallahmi|2011|p=385}} Other faiths in the country include ] (predominantly ]), ] (mostly ] and ]) and the religion of the ]. Religion plays a central role in national and civil life, and almost all ] are automatically registered as members of the state's ], which exercise control over several matters of personal status, especially ]. These recognized communities are ] (administered by the ]), Islam, the Druze faith, the ] (including the ], ], ], ], ], and ]), Greek Orthodox Church, ], ], ], and the ].<ref name="sheetrit">{{Cite web|url=http://www.mfa.gov.il/MFA/MFAArchive/2000_2009/2001/8/Freedom%20of%20Religion%20in%20Israel|title=Freedom of Religion in Israel|last=Sheetrit|first=Shimon|date=20 August 2001|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130206203625/http://www.mfa.gov.il/MFA/MFAArchive/2000_2009/2001/8/Freedom%20of%20Religion%20in%20Israel|archive-date=6 February 2013|url-status=dead|website=Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs|access-date=26 October 2008}}</ref> | |||

| The religious affiliation of the Israeli population as of 2022 was 73.6% Jewish, 18.1% ], 1.9% ], and 1.6% Druze. The remaining 4.8% included faiths such as ] and Baháʼí, as well as "religiously unclassified".<ref name="CBS 2.1">{{cite book|title=Statistical Abstract of Israel 2006 (No. 57)|publisher=]|url=http://www1.cbs.gov.il/reader/shnatonenew_site.htm|year=2006|chapter=Table 2.1 — Population, by Religion and Population. As of may 2011 estimate the population was 76.0 Jewish. Group|chapter-url=http://www1.cbs.gov.il/shnaton57/st02_01.pdf|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120914092802/http://www1.cbs.gov.il/reader/shnatonenew_site.htm|archive-date=14 September 2012}}</ref> | |||

| As of 1999, 5% of Israeli Jews defined themselves as ]m ("ultra-]"); an additional 12% as "religious"; 35% as "traditionalists" (not strictly adhering to Jewish law or ]); 43% as "secular"; and 5% as "anti-religious." Among all Israeli Jews, 65% believe in ] and 85% participate in a ] . However, other sources indicate that between 15% and 37% of Israelis identify themselves as either ] or ].<ref> on Adherents.com, ] ]. </ref> | |||

| While ] are all technically under the jurisdiction of the state Orthodox rabbinate,{{sfn|Karesh|Hurvitz|2005|p=237}} personal attitudes vary immensely, from extreme Orthodoxy to ]. Jews in Israel mainly classify themselves along a fourfold axis, from least to most observant, '']'' ({{Literal translation|]}}); '']'' ({{Literal translation|traditional}}); ''dati'' ({{Literal translation|religious}} or ']', including ]); and '']'' ({{Literal translation|ultra-religious}} or 'ultra-orthodox').{{sfn|Beit-Hallahmi|2011|p=386}}<ref name="Kedem95">{{cite book |surname=Kedem |given=Peri |chapter=Demensions of Jewish Religiosity |year=2017 |orig-year=1995 |editor-surname=Deshen |editor-given=Shlomo |editor-surname2=Liebman |editor-given2=Charles S. |editor-link2=Charles Liebman |editor-surname3=Shokeid |editor-given3=Moshe |editor-link3=Moshe Shokeid |title=Israeli Judaism: The Sociology of Religion in Israel |series=Studies of Israeli Society, 7 |place=London; New York |publisher=Routledge |pages=33–62 |edition=Reprint |chapter-url={{Google books|id=XCNHDwAAQBAJ|plainurl=y|page=33}} |url={{Google books|id=XCNHDwAAQBAJ|plainurl=y}} |isbn=978-1-56000-178-2}}</ref> | |||

| Of the ], as of 2005, 82.7% were Muslims, 8.4% were Druze, and 8.3% were Christians.<ref name="CBS 2.1" /> | |||

| ] guarantees considerable privileges and ] for the recognized communities,<ref>{{Cite web|title=People: Religious Freedom|url=https://mfa.gov.il/MFA/Facts+About+Israel/People/SOCIETY-+Religious+Freedom.htm#:~:text=The%20Declaration%20of%20the%20Establishment,to%20administer%20its%20internal%20affairs.|access-date=2021-04-27|website=mfa.gov.il}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.knesset.gov.il/laws/special/eng/basic3_eng.htm|title=Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty}}</ref> but, in tandem, does not necessarily do so for other faiths. The ] has identified Israel as one of the countries that place "high restrictions" on the free exercise of religion<ref name="prc-2">{{cite web|title=Global Restrictions on Religion (Full report)|publisher=The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life|date=December 2009|url=http://www.pewforum.org/files/2009/12/restrictions-fullreport.pdf|access-date=12 September 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160303223318/http://www.pewforum.org/files/2009/12/restrictions-fullreport.pdf|archive-date=3 March 2016|url-status=dead}}</ref> and there have been limits placed on non-Orthodox ], which are unrecognized.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://2009-2017.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2012/nea/208392.htm|title="U.S. Department of State: 2012 Report on International Religious Freedom: Israel and The Occupied Territories (May 20, 2013)"}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title=ISRAEL 2017 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT|url=https://www.justice.gov/eoir/page/file/1072241/download|access-date=27 April 2021|website=]}}</ref> Pew ranked Israel as fifth globally in terms of "inter-religious tension and violence".<ref>. Haaretz, JTA and Ben Sales. July 17, 2019</ref> | |||

| ==Religion and citizenship== | |||

| ==Religious self-definition== | |||

| Israel was founded to provide a national home, safe from persecution, to the Jewish people. Although Israeli law explicitly grants equal civil rights to all citizens regardless of religion, ethnicity, or other heritage, it gives preferential treatment in certain aspects to individuals who fall within the criteria mandated by the ]. Preferential treatment is given to Jews who seek to immigrate to Israel as part of a governmental policy to increase the Jewish population. | |||

| ] immigrants arriving in Israel under the ], 1954]] | |||

| A Gallup survey in 2015 determined that 65% of Israelis say they are either "not religious" or "convinced atheists", while 30% say they are "religious". Israel is in the middle of the international religiosity scale, between Thailand, the world's most religious country, and China, the least religious.<ref name="auto"> Haaretz, 14 April 2015</ref> | |||

| {{As of|1999}}, 65% of Israeli Jews believed in ],<ref>{{Cite web |year=2002 |title=A Portrait of Israeli Jewry: Beliefs, Observances, and Values among Israeli Jews 2000 |url=http://www.avi-chai.org/Static/Binaries/Publications/EnglishGuttman_0.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070630231145/http://www.avi-chai.org/Static/Binaries/Publications/EnglishGuttman_0.pdf |archive-date=30 June 2007 |access-date=28 January 2008 |publisher=The ] and The AVI CHAI Foundation |page=8}}</ref> and 85% participated in a ].<ref>Ib. p.11</ref> A survey conducted in 2009 showed that 80% of Israeli Jews believed in God, with 46% of them self-reporting as secular.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Hasson |first1=Nir |date=27 January 2012 |title=Survey: Record Number of Israeli Jews Believe in God |newspaper=] |url=http://www.haaretz.com/jewish-world/survey-record-number-of-israeli-jews-believe-in-god-1.409386}}</ref> Israelis' majority (2/3) tend not to align themselves with ] (such as ] or ]), but instead tend to define their religious affiliation by degree of their religious practice.<ref name="Ettinger" /> | |||

| The criteria set forth by the Law of Return are controversial. The Law of Return differs from Jewish religious law in that it disqualifies individuals who are ethnically Jewish but who converted to another religion, and also in that it grants immigrant status to individuals who are not ethnically Jewish but are related to Jews. | |||

| {{As of|2009}}, 42% of ] defined themselves as "]"; on the other opposite, 8% defined themselves as ] (ultra-orthodox); an additional 12% as "religious"; 13% as "traditional (religious)"; and 25% as "traditional (non-religious)".<ref>{{Cite web |last=Dror-Cohen |first=Shlomit |date=2010-09-12 |title=Media Releases |script-title=he:לקט נתונים מתוך הסקר החברתי :2009 שמירה על המסורת היהודית ושינויים במידת הדתיות לאורך החיים בקרב האוכלוסייה היהודית בישראל |trans-title=Social Survey 2009: Observance of Jewish Tradition and Changes in Religiosity of the Jewish Population in Israel |url=http://www.cbs.gov.il/reader/newhodaot/hodaa_template.html?hodaa=201019211 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181116100532/http://www.cbs.gov.il/reader/newhodaot/hodaa_template.html?hodaa=201019211 |archive-date=2018-11-16 |website=Central Bureau of Statistics |language=he}}</ref> | |||

| <!-- | |||

| While the Law of Return is directly concerned with non-citizens, certain Israeli laws have used the phrase "persons who would have benefited from the Law of Return had they been outside the borders of Israel" in order to define which citizens of Israel will benefit from different programs. | |||

| In 2022, 45% of Israel Jews self-identified as "secular"; 10% as ''haredi'' (ultra-orthodox); 33% as '']'' ({{Literal translation|traditional}}); and 12% as ''dati'' ({{Literal translation|religious}} or ']', including ]). | |||

| Oh come on, WRMEA is a saudi front. Go find some real sources on this. (I'm sure Al-Guardian or Al-BBC has some good dirt.) --> | |||

| Of the ], as of 2008, 82.7% were Muslims, 8.4% were Druze, and 8.3% were Christians.<ref name="CBS 2.1" /> Just over 80% of Christians are Arabs, and the majority of the remaining are immigrants from the former Soviet Union who immigrated with a Jewish relative. About 81% of Christian births are to Arab women.<ref>{{Cite web| | |||

| ==Judaism in Israel== | |||

| url=http://www.haaretz.com/hasen/spages/937993.html | |||

| |title= Central Bureau of Statistics: 2.1% of state's population is Christian | |||

| |author=Moti Bassok | |||

| |date=25 December 2007 | |||

| |publisher=HAARETZ.com | |||

| |access-date=29 January 2008}}</ref> | |||

| Among the Arab population, a 2010 research showed that 8% defined themselves as very religious, 47% as religious, 27% as not very religious, and 18% as not religious.<ref>{{cite news |date=18 May 2010 |title=Israel 2010: 42% of Jews are secular |newspaper=Ynetnews |url=http://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-3890330,00.html}}</ref> | |||

| Most citizens in the ] are ]ish, and most Israeli Jews practice ] in some form. | |||

| ==Religious groups== | |||

| While Judaism has always affirmed a collection of ], it has never developed a fully binding ]. While individual ]s, or sometimes entire groups, at times agreed upon a firm dogma, other rabbis and groups disagreed. With no central agreed-upon authority, no one formulation of Jewish principles of faith could take precedence over any other. Judaism's core belief, however, firmly remains a binding principle agreed upon by Jews of all backgrounds: the belief in one God, creator of the universe. | |||

| ===Judaism=== | |||

| In the last two centuries the largest Jewish community in the world, in the ], has divided into a number of ]. The largest and most influential of these denominations are ], ], and ]. | |||

| {{Main|Israeli Jews}} | |||

| Most citizens in the ] are Jewish.<ref name="CBS_month_pop">{{cite web|url=http://www1.cbs.gov.il/publications13/yarhon0413/pdf/b1.pdf |title=Population, by Population Group |date=31 December 2013 |website=Monthly Bulletin of Statistics |publisher=Israel Central Bureau of Statistics |access-date=17 February 2014 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140203172044/http://www1.cbs.gov.il/publications13/yarhon0413/pdf/b1.pdf |archive-date=3 February 2014 }}</ref> As of 2022, ] made up 73.6% percent of the population.<ref name="population_stat2019">{{cite report |url=https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/mediarelease/DocLib/2019/134/11_19_134b.pdf |title=Israel's Independence Day 2019 |date=6 May 2019 |publisher=Israel Central Bureau of Statistics |access-date=7 May 2019}}</ref> | |||

| ====Secular-traditional spectrum==== | |||

| All of the above denominations exist, to varying degrees, in the State of Israel. Nevertheless, Israelis tend to classify Jewish identity in ways that are strikingly different from American Jewry. | |||

| {{Main|Hiloni|Masortim|Shomer Masoret}} | |||

| ] in the city of ] on ].]] | |||

| In 2007, a ] by the ] found that 27% of Israeli Jews say that they keep the ], while 53% said they do not keep it at all. The poll also found that 50% of the respondents would give up shopping on the Sabbath as long as public transportation were kept running and leisure activities continued to be permitted; however, only 38% believed that such a compromise would reduce the tensions between the secular and religious communities.<ref>"Sabbath Poll", ''Dateline World Jewry'', ], September 2007</ref> | |||

| ] International reports that 25% of Israeli citizens regularly attend ], compared to 15% of Jewish French citizens, 10% of Jewish ], and 57% of Jewish ]. | |||

| Because the terms "]" ('']'') and "traditional" ('']'') are not strictly defined,<ref name="Liebman1990">{{cite book |year=1990 |editor-surname=Liebman |editor-given=Charles S. |editor-link=Charles Liebman |title=Religious and Secular: Conflict and Accommodation between Jews in Israel |place=New York |publisher=Keter Publ. House |isbn=0962372315}}</ref><ref name="CohenSusser">{{cite book |surname=Cohen |given=Asher |authorlink=Asher Cohen |surname2=Susser |given2=Bernard |year=2000 | |||

| ===The secular-traditional spectrum=== | |||

| |title=Israel and the Politics of Jewish Identity: The Secular-Religious Impasse |place=Baltimore, Md |publisher=Johns Hopkins University Press |isbn=9780801863455 |url-access=registration |url=https://archive.org/details/israelpoliticsof00ashe}}</ref> published estimates of the percentage of Israeli Jews who are considered "traditional" range from 32%<ref>{{Cite web |title=Freedom of Religion |url=http://www.bicom.org.uk/about_israel/freedom_of_religion/ |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20051221095430/http://www.bicom.org.uk/about_israel/freedom_of_religion |archive-date=21 December 2005 |access-date=14 October 2005 |website=BICOM}}</ref> to 55%.<ref name="dje-howrelisr">{{Cite journal |last=Daniel J. Elazar |title=How Religious are Israeli Jews? |url=http://www.jcpa.org/dje/articles2/howrelisr.htm |publisher=Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs |access-date=28 January 2008}}</ref> A Gallup survey in 2015 determined that 65% of Israelis say they are either "not religious" or "convinced atheists", while 30% say they are "religious". Israel is in the middle of the international religiosity scale, between Thailand, the world's most religious country, and China, the least religious.<ref name="auto"/> The Israeli Democracy Index commissioned in 2013 by the ] regarding religious affiliation with ] of Israeli Jews found that 3.9 percent of respondents felt attached to Reform (Progressive) Judaism, 3.2 percent to Conservative Judaism, and 26.5 percent to Orthodox Judaism. The other two thirds of respondents said they felt no connection to any denomination, or declined to respond.<ref name="Ettinger">{{cite news |author=Yair Ettinger |title=Poll: 7.1 Percent of Israeli Jews Define Themselves as Reform or Conservative |url=http://www.haaretz.com/jewish-world/jewish-world-news/.premium-1.528994 |newspaper=] |date=June 11, 2013 |access-date=2023-06-26}}</ref> However, it does not mean, that the secular/hiloni Israelis are without other forms of ].<ref>{{cite book |surname=Ezrachi |given=Elan |year=2004 |chapter=The Quest for Spirituality among Secular Israelis |title=Jews in Israel: Contemporary Social and Cultural Patterns |editor-surname=Rebhum |editor-given=Uzi |editor-surname2=Waxman |editor-given2=Chaim I. |editor-link2=Chaim I. Waxman |pages=315–330 |publisher=Brandeis University Press |chapter-url= |url={{Google books|id=I2PYTmFwQxcC|plainurl=y|page=}} |url-access=limited |isbn=<!-- 1-58465-327-2 -->}}</ref><ref>] (March 2008). "Religion for the Secular: The New Israeli Rabbinate," Journal of Modern Jewish Studies 7, 1: 67-90.</ref> | |||

| There is also a growing ] (Jewish returners) movement, involved with all Jewish denominations, of secular Israelis rejecting their previously secular lifestyles and choosing to become religiously observant, with many educational programs and ]s for them.{{Citation needed|date=April 2015}} An example is ], which received open encouragement from some sectors within the Israeli establishment. | |||

| Most Jewish Israelis classify themselves as "secular" (''hiloni'') or as "traditional" (''masorati''). The former term is more popular among Israeli families of European origin, and the latter term among Israeli families of Oriental origin (i.e. Middle East, Central Asia and North Africa). The latter term, as commonly used, has nothing to do with the official "Masorti" (Conservative Judaism) movement in the State of Israel. There is ambiguity in the ways these two terms are used. They often overlap, and they cover an extremely wide range of ideologies and levels of observance. | |||

| At the same time, there is also a significant movement in the opposite direction toward a secular lifestyle. There is some debate which trend is stronger at present. Recent polls show that ranks of secular Jewish minority in Israel continued to drop in 2009. Currently, the secular make up only 42%.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.haaretz.com/print-edition/news/poll-shows-ranks-of-secular-jewish-minority-in-israel-continued-to-drop-in-2009-1.290749|title=Poll Shows Ranks of Secular Jewish Minority in Israel Continued to Drop in 2009|newspaper=Haaretz|date=17 May 2010|last=Shtull-Trauring|first=Asaf}}</ref> | |||

| Many Jewish Israelis feel that being Israeli (living among Jews, speaking ], in the ]) is in itself a sufficient expression of Judaism without any religious observances. This conforms to some classical secular-] ideologies of Israeli-style civil religion. While many in the ] who otherwise consider themselves as secular will attend a ] or at least fast on ] (the holiest ]), this is not as common among secular Israelis. | |||

| ====Orthodox spectrum==== | |||

| Because the terms "secular" and "traditional" not are strictly defined, published estimates of the percentage of Israeli Jews who are considered "traditional" range from 32% to 55%. Estimates of the percentage of "secular" Jews vary even more widely: from 20% to 80% of the Israeli population. | |||

| {{Main|Religious Zionism|Hardal|Haredi}} | |||

| {{also|Yeshiva#Israel}} | |||

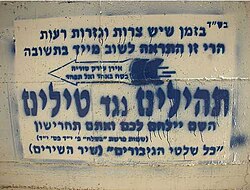

| ] against missiles'}}) ] slogan initially coined during the ] in response to ] in 1991, and turned into a popular slogan-sticker ever since, especially among the Israeli ] and ] communities.]] | |||

| The spectrum covered by "Orthodox" in the diaspora exists in Israel, again with some important variations. | |||

| ===The Orthodox spectrum=== | |||

| The spectrum covered by "Orthodox" in the diaspora exists in Israel, again with some important variations. The ] spectrum in Israel includes a far greater percentage of the Jewish population than in the diaspora, though ''how much'' greater is hotly debated. Various ways of measuring this percentage, each with its pros and cons, include the proportion of religiously observant ] members (about 25 out of 120), the proportion of Jewish children enrolled in religious schools, and statistical studies on "identity". | |||

| ], prays with tefillin.]] | |||

| What would be called "Orthodox" in the diaspora includes what is commonly called ''dati'' ("religious") or '']'' ("ultra-Orthodox") in Israel. The former term includes what is called ] or the "National Religious" community (and also ] in US terms), as well as what has become known over the past decade or so as '']'' (''haredi-leumi'', i.e. "ultra-Orthodox nationalist"), which combines a largely ''haredi'' lifestyle with a nationalist (i.e. pro-Zionist) ideology. | |||

| What would be called "Orthodox" in the diaspora includes what is commonly called ''dati'' ("religious") or '']'' ("ultra-Orthodox") in Israel.{{sfn|Beit-Hallahmi|2011|p=386}}<ref name=Lipka/> The former term includes what is called ]{{sfn|Aran|1991|p=}} or the "National Religious" community (and also ] in US terms), as well as what has become known over the past decade or so as '']'' (''Haredi-Leumi'', i. e., "ultra-Orthodox nationalist"), which combines a largely ''Haredi'' lifestyle with a nationalist (i. e., pro-Zionist) ideology. | |||

| Haredi applies to a populace that can be roughly divided into three separate groups along both ethnic and ideological lines: (1) "]" (i.e. non-hasidic) ''haredim'' of ]c (i.e "Germanic" - European) origin; (2) ] ''haredim'' of Ashkenazic (mostly of ]an) origin; and (3) ] (including ]) ''haredim''. The third group has the largest political representation in Israel's parliament (the ]), and has been the most politically active since the early ], represented by the ] party. | |||

| ] in Jerusalem, 2004]] | |||

| There is also a growing ] ("returnees") movement of secular Israelis rejecting their previously secular lifestyles and choosing to become religiously observant with many educational programs and ]s for them. An example is ], which received open encouragement from some sectors within the Israeli establishment. The Israeli government gave Aish HaTorah the real estate rights to its massive new campus opposite the ] because of its proven ability to attract all manner of secular Jews to learn more about Judaism. In many instances after visiting from foreign countries, students decide to make Israel their permanent home by making ]. Other notable organizations involved in these efforts are the ] and ] ] movements who manage to have an ever-growing appeal, the popularity of Rabbi ]'s organization and the ] organization that offer a variety of frequent free "introduction to Judaism" seminars to secular Jews, the ] organization that sends out senior yeshiva and ] students to recruit Israeli children for religious elementary schools and ] which runs ] programs. | |||

| Haredi applies to a populace that can be roughly divided into three separate groups, except mentioned ''Hardal'', along both ethnic and ideological lines: (1) "]" ''Haredim'' of ] (i. e., "Germanic" — European) origin, predominantly, adherents of non-Hasidic traditional Orthodoxy, a.k.a. ]; (2) ] ''Haredim'' of Ashkenazic (mostly of ]an) origin; and (3) '']'' (including ]). | |||

| Ultra-Orthodox sector is relatively young and numbered in 2020 more than 1,1 million (14 percent of total population).<ref name="AICE">{{cite web |url=https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/ultra-orthodox-jewish-community-in-israel-facts-and-figures |title=Ultra-Orthodox Jewish Community in Israel: Facts and Figures (2022) |work=Jewish Virtual Library. A Project of AICE |access-date=2023-06-27}}</ref> | |||

| At the same time, there is also a significant movement in the opposite direction towards a secular lifestyle. There is some debate which trend is stronger at present. | |||

| ====Non-Orthodox denominations of Judaism==== | |||

| ===The secular-religious ''Status Quo''=== | |||

| ] | |||

| The religious ], agreed upon by ] with the religious parties at the time of the declaration of independence in ] is an agreement on the religious Jewish role in government and the judicical system of Israel. Under this agreement, which is still mostly held today: | |||

| ] in ] with ] (right) looking on, 2012]] | |||

| *The Chief Rabbinate has authority over ], ], ] and ] issues (especially divorce), and ] of immigrants | |||

| ], ] (the ]), ], ] (the ]) and other new non-Orthodox ] are represented among Israeli Jews.<ref name="Tabory1990">{{cite book |year=2004 |orig-year=1990 |surname=Tabory |given=Ephraim |chapter=Reform and Conservative Judaism in Israel |title=Social Foundations of Judaism |editor-surname=Goldscheider |editor-given=Calvin |editor-surname2=Neusner |editor-given2=Jacob |editor-link2=Jacob Neusner |place=Eugene, Or |publisher=Wipf and Stock Publ. |edition=Reprint |pages=240–258 |chapter-url= |url={{Google books|id=2TxLAwAAQBAJ|plainurl=y|page=|keywords=|text=}} |url-access=limited |isbn=1-59244-943-3}}</ref><ref name="Tabory2004">{{cite book |surname=Tabory |given=Ephraim |chapter=The Israel Reform and Conservative Movements and the Marker for the Liberal Judaism |year=2004 |title=Jews in Israel: Contemporary Social and Cultural Patterns |editor-surname=Rebhum |editor-given=Uzi |editor-surname2=Waxman |editor-given2=Chaim I. |editor-link2=Chaim I. Waxman |pages=285–314 |publisher=Brandeis University Press |chapter-url= |url={{Google books|id=I2PYTmFwQxcC|plainurl=y|page=}} |url-access=limited |isbn=<!-- 1-58465-327-2 -->}}</ref><ref name="americans">{{cite book |author= |chapter=Americans in the Israeli Reform and Conservative Denominations |year=2017 |orig-year=1995 |editor-surname=Deshen |editor-given=Shlomo |editor-surname2=Liebman |editor-given2=Charles S. |editor-link2=Charles Liebman |editor-surname3=Shokeid |editor-given3=Moshe |editor-link3=Moshe Shokeid |title=Israeli Judaism: The Sociology of Religion in Israel |series=Studies of Israeli Society, 7 |place=London; New York |publisher=Routledge |edition=Reprint |chapter-url= |url-access=limited |url={{Google books|id=XCNHDwAAQBAJ|plainurl=y|page=}} |isbn=978-1-56000-178-2}}</ref>{{sfn|Karesh|Hurvitz|2005|p=237}}{{sfn|Beit-Hallahmi|2011|p=387}} According to The ], as of 2013, approximately 7 percent of Israel's Jewish population "identified" with Reform and Conservative Judaism,<ref name="Ettinger" /> a study by ] showed 5% did,<ref name=Lipka>{{cite web |url=http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/03/15/unlike-u-s-few-jews-in-israel-identify-as-reform-or-conservative/ |first=Michael |last=Lipka |title=Unlike U.S., few Jews in Israel identify as Reform or Conservative |date=15 March 2016 |publisher=]}}</ref> while a Midgam survey showed that one third "especially identified with Progressive Judaism", almost as many as those who especially identify with Orthodox Judaism. Only a few authors, like Elliot Nelson Dorff, consider the Israeli social group '']'' (traditionalists) to be one and the same with the Western Conservative (masorti) movement,<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |editor-surname=Berlin |editor-given=Adele |editor-link=Adele Berlin |title=The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion |edition=2nd |page=350 |year=2011 |publisher=Oxford University Press |place=Oxford; New York |url={{Google books|id=hKAaJXvUaUoC|plainurl=y|page=350|keywords=|text=}} |isbn=978-0-19-975927-9}}</ref> it produces understanding Conservative Judaism as a major denomination in Israel, associated with a large social sector. | |||

| *Streets of ] neighborhoods are closed to traffic on the ] | |||

| *There is no ] on that day, and most businesses are closed. However there is public transport in ], since Haifa had a large secular population at the time of the British Mandate. | |||

| *Restaurants who wish to advertise themselves as ] must be certified by the ] | |||

| *Importation of non-kosher foods is prohibited. Despite prohibition, there are a few local pork farms in ]im, catering for establishments selling "White Meat", due to its relatively popular demand among specific population sectors, particularly the ]n immigrants of the ]. Despite the Status Quo, the ] ruled in ] that local governments are not allowed to ban the sale of pork, although this had previously been a common by-law. | |||

| The Chief Rabbinate strongly opposes the Reform and Conservative movements,{{sfn|Beit-Hallahmi|2011|p=387}} saying they are "uprooting Judaism", that they cause assimilation and that they have “no connection” to authentic Judaism.<ref name="JPost - Chief Rabbinate opposes reform movements">{{cite news |author= Jeremy Sharon |author2=Sam Sokol |title=Chief Rabbinate in fierce attack on Reform, Conservative movements|url=http://www.jpost.com/Israel-News/Politics-And-Diplomacy/Chief-Rabbinate-in-fierce-attack-on-Reform-Conservative-movements-446143 |access-date=2016-04-27 |newspaper=] |date=25 February 2016}}</ref> The chief rabbinate's view does not reflect the majority viewpoint of Israeli Jews, however. A survey of Israeli Jews published in May 2016 showed that 72 percent of respondents said they disagreed with the Haredi assertions that Reform Jews are not really Jewish. The survey also showed that a third of Israeli Jews "identify" with progressive (Reform or Conservative) Judaism and almost two thirds agree that Reform Judaism should have equal rights in Israel with Orthodox Judaism.<ref name="jta2016">. ''JTA'', 27 May 2016.</ref> The report was organized by the ] ahead of its 52nd biennial conference. | |||

| Nevertheless, some breaches of the ''status quo'' have become prevalent, such as several suburban malls remaining open during the Sabbath. Though this is contrary to the law, the Government largely turns a blind eye. The relationship between Judaism and the state has always been a controversial and unstable one. | |||

| ==== Secular–religious status quo ==== | |||

| There have been many problems brought forth by secular Israelis regarding the Chief Rabbinate's strict control over Jewish weddings, Jewish divorce proceedings, conversions, and who counts as Jewish for the purposes of immigration. | |||

| {{Main|Status quo (Israel)}} | |||

| The religious ], agreed to by ] with the Orthodox parties at the time of Israel's formation in 1948, is an agreement on the role that Judaism would play in Israel's government and the judicial system. The agreement was based upon a letter sent by Ben-Gurion to ] dated 19 June 1947.<ref>''The Status Quo Letter'' ( {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110716140145/http://w3.kfar-olami.org.il/asaf/pedagogical/ezrahut/status.doc |date=16 July 2011 }}) {{in lang|he}} in ''Israel in the Middle East: Documents and Readings on Society, Politics, and Foreign Relations, Pre-1948 to the Present'', editors Itamar Rabinovich and Jehuda Reinharz. {{ISBN|978-0-87451-962-4}}</ref> Under this agreement, which still operates in most respects today:<ref name="Liebman1990" /> | |||

| * The Chief Rabbinate has authority over ], ], ] and personal status issues, such as ], divorce, and conversions. | |||

| * Streets in ] neighborhoods are closed to traffic on the Jewish Sabbath. | |||

| * There is no ] on the Jewish Sabbath, and most businesses are closed. However, there is public transport in ], since Haifa had a large Arab population at the time of the British Mandate. | |||

| * Restaurants who wish to advertise themselves as ] must be certified by the ]. | |||

| * Importation of non-kosher foods is prohibited. Despite this prohibition, a few pork farms supply establishments selling ], due to demand therefore among specific population sectors, particularly the Russian immigrants of the 1990s. Despite the status quo, the ] ruled in 2004 that local governments are not allowed to ban the sale of pork, although this had previously been a common by-law. | |||

| Nevertheless, some breaches of the ''status quo'' have become prevalent, such as several suburban malls remaining open during the Sabbath. Though this is ], the government largely turns a blind eye. | |||

| The state of Israel forbids and does not approve of any civil marriages or non-religious divorces performed by the secular Israeli Jews within the country. Because of this many Israelis choose to marry outside of Israel. | |||

| While the state of Israel enables freedom of religion for all of its citizens, it does not enable civil marriage. The state forbids and disapproves of any civil marriages or non-religious divorces performed amongst within the country. Because of this, some Israelis choose to marry outside of Israel. Many parts of the "status quo" have been challenged by secular Israelis regarding the Chief Rabbinate's strict control over Jewish weddings, Jewish divorce proceedings, conversions, and the question of ] for the purposes of immigration. | |||

| The ] manages the secular (largest) and religious streams of various faiths in parallel, with a limited degree independence and a common core Curriculum. | |||

| The ] manages the secular and Orthodox school networks of various faiths in parallel, with a limited degree of independence and a common core curriculum. | |||

| In recent years, perceived frustration among some members of the secular sector with the ''Status Quo'' has strengthened parties such as ], which advocate separation of religion from the state, without much success so far. | |||

| In recent years, perceived frustration with the ''status quo'' among the secular population has strengthened parties such as ], which advocate separation of religion and state, without much success so far. | |||

| Today the secular Israeli-Jews claim that they aren't religious and don't follow the Jewish rules and that Israel as a democratic modern country should not force the old outdated religious rules upon its citizens against their will. The religious Israeli-Jews claim that the separation between state and religion will contribute to the end of Israel's Jewish identity. | |||

| Today the secular Israeli Jews claim that they aren't religious and don't observe Jewish law, and that Israel as a democratic modern country should not force the observance thereof upon its citizens against their will. The Orthodox Israeli Jews claim that the separation between state and religion will contribute to the end of Israel's Jewish identity.<ref name="Liebman1990" /> | |||

| Signs of the first challenge to the status quo came in 1977, with the fall of the Labor government that had ruled Israel since independence and the formation of a rightwing coalition under ]. Right-wing Revisionist Zionism had always been more acceptable to the religious parties, since it did not share the same history of antireligious rhetoric that marked socialist Zionism. Furthermore, Begin needed the Haredi members of the Knesset (Israel's unicameral parliament) to form his coalition and offered more power and benefits to their community than what they were accustomed to receiving, including a lifting of the numerical limit on military exemptions. | |||

| Signs of the first challenge to the status quo came in 1977, with the fall of the Labor government that had been in power since independence, and the formation of a right-wing coalition under ]. Right-wing Revisionist Zionism had always been more acceptable to the Orthodox parties, since it did not share the same history of anti-religious rhetoric that marked socialist Zionism. Furthermore, Begin needed the Haredi members of the Knesset (Israel's unicameral parliament) to form his coalition, and offered more power and benefits to their community than what they had been accustomed to receiving, including a lifting of the numerical limit on military exemptions for those engaged in full-time Torah study.{{sfn|Aran|1991|p=}} | |||

| On the other hand, secular (nonreligious) Israelis (] and ] have always had a negligible presence in Israel), began questioning whether a "status quo" based on the conditions of the 1940s and 1950s was still relevant in the 1980s and 1990s, and perceived that they had cultural and institutional support to enable them to change it regardless of its relevance. They challenged Orthodox control of personal affairs such as marriage and divorce, resented the lack of entertainment and transportation options on the ] (then the country's only day of rest), and questioned whether the burden of military service was being shared equally, since the 400 scholars, who originally benefited from the exemption, had grown to 50,000. Finally, the Progressive (]) and ] communities, though still minuscule, began to exert themselves as an alternative to the Haredi control of religious issues. | |||

| On the other hand, secular Israelis began questioning whether a "status quo" based on the conditions of the 1940s and 1950s was still relevant in the 1980s and 1990s, and reckoned that they had cultural and institutional support to enable them to change it regardless of its relevance. They challenged Orthodox control of personal affairs such as marriage and divorce, resented the lack of entertainment and transportation options on the Jewish Sabbath (then the country's only day of rest), and questioned whether the burden of military service was being shared equitably,<ref name="Liebman1990" /> since the 400 scholars who originally benefited from the exemption, had grown to 50,000.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Stern |first=Yedidia Z. |last2=Zicherman |first2=Haim |date=2013 |title=The Haredi Draft: A Framework for Ultra-Orthodox Military Service in Israel |url=https://en.idi.org.il/publications/5193 |publisher=The Israel Democracy Institute |language=he}}</ref> Finally, the Progressive and Conservative communities, though still small, began to exert themselves as an alternative to the Haredi control of religious issues. No one was happy with the "status quo"; the Orthodox used their newfound political force to attempt to extend religious control, and the non-Orthodox sought to reduce or even eliminate it.{{sfn|Beit-Hallahmi|2011|p=387}}<ref name="jta2016" /> | |||

| No one was happy with the "status quo"; the Orthodox used their new-found political force to attempt to extend religious control, and the non-Orthodox sought to reduce or even eliminate it. | |||

| === |

====Chief Rabbinate==== | ||

| {{Main|Chief Rabbinate of Israel}} | |||

| ] first Chief Rabbi of the ].]] | |||

| ] in ], which serves as the seat of the ]]] | |||

| It was during the ] that the British administration established an official dual Ashkenazi-Sephardi "Chief Rabbinate" (''rabbanut harashit'') that was exclusively ], as part of an effort to consolidate and organize Jewish life based on its own model in Britain which encouraged strict loyalty to the British crown, and in order to attempt to influence the religious life of the Jews in Palestine in a similar fashion. In 1921, Rabbi ] (1864-1935) was chosen as the first ] ] and Rabbi ] as the first ] Chief Rabbi (''Rishon LeTzion''). Rabbi Kook was a leading light of the ] movement, and was acknowledged by all as a great rabbi of his generation. He believed that the work of secular Jews towards creating an eventual Jewish state in ] was part of a divine plan for the settlement of the ]. The return to Israel was in Kook's view not merely a political phenomenon to save Jews from persecution, but an event of extraordinary historical and theological significance. | |||

| It was during the ] that the British administration established an official dual Ashkenazi-Sephardi "Chief Rabbinate" (''rabbanut harashit'') that was exclusively Orthodox, as part of an effort to consolidate and organize Jewish life based on its own model in Britain, which encouraged strict loyalty to the British crown, and in order to attempt to influence the religious life of the Jews in Palestine in a similar fashion.{{Citation needed|date=April 2015}} In 1921, Rabbi ] (1864–1935) was chosen as the first ] ] and Rabbi ] as the first ] Chief Rabbi (''Rishon LeTzion''). Rabbi Kook was a leading light of the ] movement, and was acknowledged by all as a great rabbi of his generation. He believed that the work of secular Jews toward creating an eventual Jewish state in ] was part of a divine plan for the settlement of the ]. The return to Israel was in Kook's view not merely a political phenomenon to save Jews from persecution, but an event of extraordinary historical and theological significance.{{Citation needed|date=April 2015}} | |||

| Prior to the 1917 British conquest of Palestine, the ]s had recognized the leading ]ic rabbis of the old ''yishuv'' (" settlement") as the official leaders of the small Jewish community that for many centuries consisted mostly of the devoutly Orthodox Jews from ] as well as those from the ] who had made ] to the ], primarily for religious reasons. The European immigrants had unified themselves in an organization initially known as the ''Vaad Ha'ir'', which later changed its name to '']''. The Turks viewed the local rabbis of Palestine as extensions of their own Orthodox ]s (" Chief Rabbi/s") who were loyal to the Sultan. | |||

| ] is under the supervision of the ].]] | |||

| Prior to the 1917 British conquest of Palestine, the Ottomans had recognized the leading rabbis of the ] as the official leaders of the small Jewish community that for many centuries consisted mostly of the devoutly Orthodox Jews from ] as well as those from the ] who had made ] to the Holy Land, primarily for religious reasons. The European immigrants had unified themselves in an organization initially known as the ''Vaad Ha'ir'', which later changed its name to '']''. The Turks viewed the local rabbis of Palestine as extensions of their own Orthodox ]s (" Chief Rabbi/s") who were loyal to the Sultan.{{Citation needed|date=April 2015}} | |||

| Thus the centrality of an Orthodox dominated Chief Rabbinate became part of the new state of Israel as well when it was ]. Based in its central offices at ''Heichal Shlomo'' in ] the Israeli Chief rabbinate has continued to wield exclusive control over all the Jewish religious aspects of the secular state of Israel. Through a complex system of "advice and consent" from a variety of senior rabbis and influential politicians, each Israeli city and town also gets to elect its own local Orthodox Chief Rabbi who is looked up to by substantial regional and even national religious and even non-religious Israeli Jews. | Thus the centrality of an Orthodox dominated Chief Rabbinate became part of the new state of Israel as well when it was ]. {{Citation needed|date=April 2015}}Based in its central offices at ''Heichal Shlomo'' in ] the Israeli Chief rabbinate has continued to wield exclusive control over all the Jewish religious aspects of the secular state of Israel. Through a complex system of "advice and consent" from a variety of senior rabbis and influential politicians, each Israeli city and town also gets to elect its own local Orthodox Chief Rabbi who is looked up to by substantial regional and even national religious and even non-religious Israeli Jews.{{Citation needed|date=April 2015}} | ||

| Through a national network of ] ("religious courts"), each headed only by approved Orthodox ] judges, as well as a network of "Religious Councils" that are part of each municipality, the Israeli Chief Rabbinate retains exclusive control and has the final say in the state about virtually all matters pertaining to ], the ], the status of ], and monitoring and acting when called upon to supervise the observance of some laws relating to Shabbat observance, ] (particularly when issues concerning the sale or ownership of ] come up), the ] and the ] in the agricultural sphere.{{Citation needed|date=April 2015}} | |||

| ] former ] Chief Rabbi and spiritual leader the ] party.]] | |||

| The ] also relies on the Chief Rabbinate's approval for its own Jewish chaplains who are exclusively Orthodox. The IDF has a number of units that cater to the unique religious requirements of the Religious Zionist ] students through the ] program of combined alternating military service and yeshiva studies over several years.{{Citation needed|date=April 2015}} | |||

| Through a national network of ] ("religious courts"), each headed only by approved Orthodox ] judges, as well as a network of "Religious Councils" that are part of each municipality, the Israeli Chief Rabbinate retains exclusive control and has the final say in the state about virtually all matters pertaining to ], the ], the status of ], and monitoring and acting when called upon to supervise the observance of some laws relating to ] observance, ] (particularly when issues concerning the sale or ownership of ] come up), the ] and the ] in the agricultural sphere. | |||

| A poll conducted by the ] in April and May 2014 of which institutions were most and least trusted by Israeli citizens showed that Israelis have little trust in the religious establishment. When asked which public institutions they most trusted, the Chief Rabbinate at 29% was one of the least trusted.<ref>"Tamar Pileggi 'Jews and Arabs proud to be Israeli, distrust government: Poll conducted before war shows marked rise in support for state among Arabs; religious establishment scores low on trust' (4 Jan 2015) The Times of Israel" http://www.timesofisrael.com/jews-and-arabs-proud-to-be-israeli-distrust-government/</ref> | |||

| The ] (IDF) also relies on the Chief Rabbinate's approval for its own Jewish chaplains who are exclusively Orthodox. The IDF has a number of units that cater to the unique religious requirements of the Religious Zionist ] students through the ] program of combined alternating military service and yeshiva studies over several years. | |||

| ==== |

====Karaite Judaism==== | ||

| ]]] | |||

| The Chief Rabbinate is nevertheless under constant criticism and pressure from both the "left" and "right" wings of Judaism and Jewish groups. Many secular Israelis dislike the fact that their private lives are subject to the rulings of a religious court, albeit a Jewish one. The ] and ] movements based in the United States resent that they are locked out of Israel's religious establishment and remain unrecognized as official Jewish religious bodies in Israel. They have established offices and synagogues in Israel to propagate their views. Simultaneously, the ] population, including many ] groups, view the Chief Rabbinate as "too lenient", "too Zionistic", and of being the "lackeys" of the Israeli political establishment, since, for example, even members of the Knesset who are not religious, are allowed to be part of the electoral college that elects each new set of Chief Rabbis every ten years. | |||

| The ] are an ancient Jewish community that practices a form of Judaism distinct from ], dating ostensibly to between the 7th and 9th centuries based on textual evidence,<ref>Mourad El-Kodsi, The Karaite Jews of Egypt, 1987.</ref><ref>Ash-Shubban Al-Qarra’in 4, 2 June 1937, p. 8.</ref><ref>Oesterley, W. O. E. & Box, G. H. (1920) A Short Survey of the Literature of Rabbinical and Mediæval Judaism, Burt Franklin:New York.</ref> though they claim a tradition at least as old as other forms of Judaism with some tracing their origins to the Masoretes and the Sadducees. Once making up a significant proportion{{Clarify|reason=vague|date=August 2015}} of the Jewish population,<ref>A. J. Jacobs, The Year of Living Biblically, p. 69.</ref> they are now an extreme minority compared to Rabbinical Judaism. Nearly the entirety of their population, between 30,000 and 50,000, currently live in Israel,<ref name="Isabel Kershner 2013">Isabel Kershner, "New Generation of Jewish Sect Takes Up Struggle to Protect Place in Modern Israel", ''The New York Times'', 4 September 2013.</ref> and reside mainly in ], ] and ]. There are an estimated 10,000 additional Karaites living elsewhere around the world, mainly in the United States, Turkey,<ref name="Isabel Kershner 2013"/> Poland,<ref>"Charakterystyka mniejszości narodowych i etnicznych w Polsce" (in Polish). Warsaw: Ministerstwo Spraw Wewnętrznych (Polish Interior Ministry). Retrieved 7 April 2012.</ref> and elsewhere in Europe. | |||

| ====Conversion process==== | |||

| ] & ]es, Western Wall background]] | |||

| On 7 December 2016, the chief rabbis of Israel issued a new policy requiring that foreign Jewish converts be recognized in Israel, and vowed to release criteria required for recognizing rabbis who perform such conversions.<ref name="kpppafab">{{Cite news | url=http://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/1.757795 |title = Israel to Publish Criteria for Recognizing Rabbis Who Perform Conversions Abroad|newspaper = Haaretz|date = 8 December 2016|last1 = Maltz|first1 = Judy}}</ref> Previously, such conversions were not required to be recognized.<ref name="kpppafab"/> However, within one week the chief rabbis had retracted their earlier promise and instead appointed members to a joint committee of five rabbis who would formulate the conversion criteria.<ref>{{Cite news | url=http://www.timesofisrael.com/chief-rabbis-set-up-committee-to-rule-on-conversions-performed-abroad/ | title=Rabbinate forms conversion vetting panel, raising hackles anew}}</ref> | |||

| ===Samaritans=== | |||

| ===Jerusalem, Jews and Judaism=== | |||

| {{further|Samaritanism|Samaritans}} | |||

| Israel is home to the only significant populations of ] in the world. They are adherents of Samaritanism—an Abrahamic religion similar to Judaism.{{sfn|Pummer|1987}}{{sfn|Mor|Reiterer|Winkler|2010}} | |||

| As of 1 November 2007, there were 712 Samaritans.<ref name="SamNews20071101">"Developed Community", A.B. The Samaritan News Bi-Weekly Magazine, 1 November 2007.</ref> The community lives almost exclusively in Kiryat Luza on ] and in ]. Their traditional religious leader is the ], currently ]. Ancestrally, they claim descent from a group of ] inhabitants from the tribes of Joseph (divided between the two "half tribes" of ] and ]), and the priestly ].<ref>David Noel Freedman, ''The Anchor Bible Dictionary'', 5:941 (New York: Doubleday, 1996, c1992)</ref> Despite being counted separately in the census, for the purposes of citizenship, the Israeli Chief Rabbinate has classified them as Jews according to law.{{sfn|Sela|1994|pp=255–267}} | |||

| ===Christianity=== | |||

| :''Main article: ]'' | |||

| {{Main|Christianity in Israel}} | |||

| Most Christians living permanently in Israel are ], or have come from other countries to live and work mainly in ] or ], which have long and enduring histories in the land.{{Citation needed|date=April 2015}} Ten churches are officially recognized under Israel's ], which provides for the self-regulation of status issues, such as marriage and divorce. These are the ] (including the ], ], ], ], ], and ]), ] (particularly the ]), the ], and ].<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|url=http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/freedom-of-religion-in-israel|title=Freedom of Religion in Israel|website=www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org|language=en|access-date=16 May 2017}}</ref> | |||

| ] are one of the most educated groups in Israel. ] has described the Christian-Arab sector as "the most successful in the education system",<ref name="המגזר הערבי נוצרי הכי מצליח במערכת החינוך">{{cite web|url=http://www.nrg.co.il/online/1/ART2/319/566.html|title=חדשות - בארץ nrg - ...המגזר הערבי נוצרי הכי מצליח במערכת}}</ref> since Christian Arabs fared the best in terms of education in comparison to any other group receiving an education in Israel.<ref name="Christians in Israel: Strong in education">{{cite news|url=http://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-4323529,00.html|title=Christians in Israel: Strong in education|newspaper=Ynetnews|date=23 December 2012|last1=Druckman|first1=Yaron}}</ref> Arab Christians were also the vanguard in terms of eligibility for ],<ref name="Christians in Israel: Strong in education"/> and they have attained ] and ] at higher rates than Jews, Druze or Muslims in Israel.<ref name="Christians in Israel: Strong in education"/> | |||

| ] has long been embedded into the religious consciousness of the Jewish people. Jews have always studied and personalized the struggle by ] to capture Jerusalem and his desire to build the ] there, as described in the ] and the ]. Many of King David's yearnings about Jerusalem have been adapted into popular prayers and songs. For this reason, Jerusalem quickly became Israel's largest city; much through support of religious Israeli and diaspora Jews. In fact, Jews have maintained a majority in Jerusalem since at least 1864, according to British census records . | |||

| There is also a small community of ], or Hebrew-speaking converts from Judaism to Catholicism. In 2003, a ] was appointed for the first time by the Vatican to oversee the Hebrew Catholic community in Israel.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2012-09-27 |title=ZENIT - Israel's Hebrew-Speaking Catholics |url=http://www.zenit.org/article-22834?l=english |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120927020453/http://www.zenit.org/article-22834?l=english |url-status=dead |archive-date=2012-09-27 |access-date=2023-12-08 }}</ref> | |||

| Nonetheless, a large portion of secular Israelis have little connection with Jerusalem and rarely visit it, in stark contrast to the centrality it is given in Israeli religious and diaspora Jewish communities. | |||

| According to historical and traditional sources, ] lived in the ], and died and was buried on the site of the ] in Jerusalem, making the land a ] for Christianity. However, few ] now live in the area, compared to Muslims and Jews. This is because Islam displaced Christianity in almost all of the Middle East, and the rise of modern ] and the establishment of the State of Israel has seen millions of Jews migrate to Israel. Recently, the Christian population in Israel has increased with the immigration of foreign workers from a number of countries, and the immigration of accompanying non-Jewish spouses in ]s. Numerous churches have opened in ].<ref>Adriana Kemp & Rebeca Raijman, "Christian Zionists in the Holy Land: Evangelical Churches, Labor Migrants, and the Jewish State", ''Identities: Global Studies in Power and Culture'', 10:3, 295-318</ref> | |||

| ==Messianic Judaism in Israel== | |||

| ] is a branch of Christianity which fuses a Jewish identity with a belief in | |||

| ] as the ]. They emphasise that Jesus himself was a ], and so were his early followers. Messianic followers in ] vary from those who hold Trinitarian beliefs like the members of ] to those who outright reject traditional ] and its symbols, in favour of celebrating ]. Some members of ] congregations have some form of Jewish ethnic background. Others are Christians who choose to affiliate with ] congregations to capture a more authentic religious experience. While members of Christian, Muslim and other faiths are not recognized as Jews under Israel's Law of Return, , a substantial number have emigrated to Israel with some sources claiming that there are up to 10,000 in the State of Israel. | |||

| ====Eastern Orthodox and Catholic churches==== | |||

| ==Islam in Israel== | |||

| Most Christians in Israel belong primarily to branches of the Eastern Orthodox and Catholic Churches that oversee a variety of church buildings, monasteries, seminaries, and religious institutions all over the land, particularly in ].{{Citation needed|date=April 2016}} | |||

| {{main|Islam in Israel}} | |||

| Israel lies adjacent to ]'s third holiest site or shrine after those in ] and ] in ]: The '']'' (]) from which Muslims believe that ] ascended to Heaven. This belief, not only by Israeli Muslims, but by all Muslims, raises the importance of the ] and the adjacent ]. Most Muslims are angered by rumors that the Israeli government are trying to demolish the shrines, replacing them with the ]. These beliefs are unfounded; in 1967, the Government of Israel acknowledged the authority of the Waqf to administer Muslim holy sites. Israel has always protected the Haram Al Sharif and even forbids Jews from saying prayers at the site of the Holy of Holies. | |||

| ====Protestants==== | |||

| ] on the ], Jerusalem.]] | |||

| Protestant Christians account for less than one percent of Israeli citizens, but foreign ] Protestants are a prominent source of political support for the State of Israel (see ]).<ref>{{cite web|last1=Zylstra|first1=Sarah|title=Israeli Christians Think and Do Almost the Opposite of American Evangelicals|url=http://www.christianitytoday.com/news/2016/march/israel-christians-think-opposite-evangelicals-pew-zionism.html|website=Christianity Today|date=8 March 2016 |access-date=24 February 2018}}</ref> Each year hundreds of thousands of Protestant Christians come as ] to see Israel.<ref>{{cite web|title=Christian tourism to Israel|url=http://mfa.gov.il/MFA/PressRoom/2014/Pages/Christian-tourism-to-Israel-2013.aspx|website=mfa.gov.il |publisher=Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs|access-date=24 February 2018}}</ref> | |||

| ==== Messianic Judaism ==== | |||

| Most Muslims in Israel are ] ]s. From ] to ], the Sunni ] ruled the areas that now include Israel. Their rulership reinforced and ensured the centrality and importance of Islam as the dominant religion in the region. The ] in 1917 and the subsequent ] opened the gates for the arrival of large numbers of Jews in Palestine who began to tip the scales in favor of Judaism with the passing of each decade. However, the British transferred the symbolic Islamic governance of the land to the ]s based in ], and not to the ]. The Hashemites thus became the official guardians of the Islamic holy places of Jerusalem and the areas around it, particularly strong when Jordan controlled the ] (1948-1967). | |||

| {{Main|Messianic Judaism}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Messianic Judaism is a religious movement that arose within Evangelical Protestantism and incorporates elements of Judaism with the ]. They worship God the Father as one with ]. They worship Jesus, whom they call "Yeshua". Messianic Jews believe that Jesus is the ].<ref name=steiner>{{cite book |title=Jews |first=Rudolf |last=Steiner |author2=George E. Berkley |year=1997 |publisher=Branden Books |isbn=978-0-8283-2027-6 |quote=A more rapidly growing organization is the Messianic Jewish Alliance of America, whose congregations assemble on Friday evening and Saturday morning, recite Hebrew prayers, and sometimes wear ''talliot'' (prayer shawls). They worship Jesus, whom they call Yeshua. |page=129}}</ref><ref>{{cite encyclopedia |editor-surname=Melton |editor-given=J. Gordon |editor-link=J. Gordon Melton |year=2005 |entry=Messianic Judaism |title=Encyclopedia of Protestantism |place=New York |publisher=Facts On File |series=Encyclopedia of World Religions |page=373 |entry-url={{Google books|id=bW3sXBjnokkC|plainurl=y|page=373|keywords=|text=}} |url={{Google books|id=bW3sXBjnokkC|plainurl=y}} |isbn=0-8160-5456-8 |quote="Messianic Judaism is a Protestant movement that emerged in the last half of the 20th century among believers who were ethnically Jewish but had adopted an Evangelical Christian faith.…By the 1960s, a new effort to create a culturally Jewish Protestant Christianity emerged among individuals who began to call themselves Messianic Jews."}}</ref> They emphasise that Jesus was a Jew, as were his early followers. Most adherents in Israel reject traditional Christianity and its symbols, in favour of celebrating ]. Although followers of Messianic Judaism are not considered Jews under Israel's Law of Return,<ref>{{Cite journal | |||

| In ] the British had created the ] in the ] and appointed ] (1895-1974) as the Grand ] of Jerusalem. The council was abolished in 1948, but the Grand Mufti continued as one of the most notorious Islamic and Arab leaders of modern times, often inciting Muslims against Jews wherever he went. | |||

| |url=http://www.wwrn.org/article.php?idd=21820&sec=59&con=35 | |||

| |title=Aliyah with a cat, a dog and Jesus | |||

| |author=Daphna Berman | |||

| |publisher=WorldWide Religious News citing & quoting "Haaretz", 10 June 2006 | |||

| |access-date=28 January 2008 | |||

| |url-status=dead | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080117214825/http://www.wwrn.org/article.php?idd=21820&sec=59&con=35 | |||

| |archive-date=17 January 2008 | |||

| }}</ref> there are an estimated 10,000–20,000 adherents in the State of Israel, both Jews and other non-Arab Israelis, many of them recent immigrants from the former Soviet Union.<ref>{{cite news | |||

| |title=Messianic Jews in Israel claim 10,000 |work=The Jerusalem Post |author=Larry Derfner; Ksenia Svetlova |date=April 29, 2005}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Posner |first=Sarah |date=2012-11-29 |title=Kosher Jesus: Messianic Jews in the Holy Land |url=https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2012/11/kosher-jesus-messianic-jews-in-the-holy-land/265670/ |access-date=2024-09-25 |website=] |language=en}}</ref> In Jerusalem, there are twelve Messianic congregations<ref>{{cite journal |url=http://www.lmf.org.uk |title=Messianic perspectives for Today |publisher=leeds Messianic fellowship |access-date=2008-01-28}}</ref>{{Failed verification|date=January 2008}}. This is growing religious group in Israel, according to both its proponents and critics.<ref name="Posner">{{cite journal |author=Sarah Posner |date=November 29, 2012 |title=Kosher Jesus: Messianic Jews in the Holy Land |url=https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2012/11/kosher-jesus-messianic-jews-in-the-holy-land/265670/ |journal=] |access-date=2023-06-28}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=-6244392868781886952&q=messianic+jews |title=Israel Channel 2 News - 23 February 200… |date=8 April 2007 |access-date=28 January 2008}} (9 minute video, Hebrew audio, English subtitles)</ref> In Israel Jewish Christians themselves, go by the name ''Meshiykhiyyim'' (from ], as found in the ] Hebrew New Testament) rather than the traditional Talmudic name for Christians ''Notzrim'' (from ]).<ref>example: The Christian Church, Jaffa Tel-Aviv website {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110904221705/http://www.baj.co.il/article/article-reading-jewsorchristians |date=4 September 2011}} יהודים משיחיים - יהודים או נוצרים?</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Falk |first=Avner |author-link=Avner Falk |title=Franks and Saracens: Reality and Fantasy in the Crusades |publisher=Routledge |year=2010 |isbn=9781855757332 |location=London & New York |pages=4 |language=en-US |quote=Nonetheless, the Talmudic Hebrew name (as well as the modern Hebrew name) for Christians is not meshikhiyim (messianic) but notsrim (people from Nazareth), referring to the fact that Jesus came from Nazareth.}}</ref> | |||

| ===Islam=== | |||

| Israeli Muslims are free to teach Islam to their children in their own schools. | |||

| {{Main|Islam in Israel}} | |||

| ] decorations in ]]] | |||

| ===Jerusalem and Islam=== | |||

| Jerusalem is a city of major religious significance for Muslims worldwide. | |||

| :''Main article: ]'' | |||

| After capturing the Old City of Jerusalem in 1967, Israel found itself in control of Mount Moriah, which was the site of both Jewish temples and Islam's third holiest site, after those in ] and ] in ]: The '']'' (]) from which Muslims believe that ] ascended to Heaven. This mountain, which has the ] and the adjacent ] on it, is the third-holiest site in Islam (and the holiest in Judaism). Since 1967, the Israeli government has granted authority to a ] to administer the area. Rumors that the Israeli government are seeking to demolish the Muslim sites have angered Muslims. These beliefs are possibly related to excavations that have been taking place close to the Temple Mount, with the intention of gathering archeological remnants of the first and second temple period,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.bibleplaces.com/southerntm.htm|title=Southern Temple Mount}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.jcpa.org/jl/vp483.htm|title=The Destruction of the Temple Mount Antiquities, by Mark Ami-El|website=www.jcpa.org}}</ref> as well as the stance of some rabbis and activists who call for its destruction to replace it with the Third Temple.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Selig |first=Abe |date=2010-03-29 |title=J'lem posters call for 3rd Temple |url=https://www.jpost.com/Israel/Jlem-posters-call-for-3rd-Temple |access-date=2024-09-25 |website=] |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Most Muslims in Israel are ] ]s with a small minority of ].<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=t7Ao8dYsCskC&pg=PA45| title=The Arabs in Israel | access-date=2 June 2014 | author=Ori Stendel | page=45 | publisher=Sussex Academic Press | isbn=978-1898723240| year=1996 }}</ref> From 1516 to 1917, the Sunni ] ruled the areas that now include Israel. Their rulership reinforced and ensured the centrality and importance of Islam as the dominant religion in the region. The ] in 1917 and the subsequent ] opened the gates for the arrival of large numbers of Jews in Palestine who began to tip the scales in favor of Judaism with the passing of each decade. However, the British transferred the symbolic Islamic governance of the land to the ]s based in ], and not to the ]. The Hashemites thus became the official guardians of the Islamic holy places of Jerusalem and the areas around it, particularly strong when Jordan controlled the ] (1948–1967). | |||

| ==Christianity in Israel== | |||

| In 1922 the British had created the ] in the ] and appointed ] (1895–1974) as the Grand ] of Jerusalem. The council was disbanded by Jordan in 1951.{{Citation needed|date=November 2018}} Israeli Muslims are free to teach Islam to their children in their own schools, and there are a number of Islamic universities and colleges in Israel and the territories. Islamic law remains the law for concerns relating to, for example, marriage, divorce, inheritance and other family matters relating to Muslims, without the need for formal recognition arrangements of the kind extended to the main Christian churches. Similarly Ottoman law, in the form of the ], for a long time remained the basis of large parts of Israeli law, for example concerning land ownership.<ref>Guberman, Shlomo (2000). , Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, accessed January 2007</ref> | |||

| Christians are presently the smallest religious group and denomination of the ]s in Israel. Most Christians living permanently in Israel are ]s or have come from other countries to live and work mainly in ]es or ] with long histories in the land. | |||

| ====Ahmadiyya==== | |||

| A great paradox about the areas of Israel and its surroundings is that even though according to Christian teachings it is where ] was born, lived, and died (according to Roman Catholic tradition, the ] in Jerusalem is the place where Jesus died and was eventually buried -- making Jerusalem one of Christianity's holiest sites), there are nevertheless very few ]s living in the area compared to Muslims and Jews. This is because: (1) the rise of Islam displaced Christianity in almost all of the ] and beyond, and (2) since the rise of modern ], including changes in the ] balance between the world's powers, millions of Jews have flocked to the newly-established State of Israel. | |||

| {{Main|Ahmadiyya in Israel}} | |||

| ] is a small Islamic sect in ]. The history of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community in Israel begins with a tour of the Middle East in 1924 made by the second ] of the Community ] and a number of missionaries. However, the Community was first established in the region in 1928, in what was then the British Mandate of Palestine. The first converts to the movement belonged to the ''Odeh'' tribe who originated from ], a small village near ]. In the 1950s they settled in Kababir, a former village which was later absorbed by the city of Haifa.<ref>{{cite journal | title=Approaching conflict the Ahmadiyya way: The alternative way to conflict resolution of the Ahmadiyya community in Haifa, Israel | author=Emanuela C. Del Re | publisher=Springer | page=116 | date=3 March 2014 }}</ref> The neighbourhood's first mosque was built in 1931, and a larger one, called the ], in the 1980s. Israel is the only country in the Middle East where Ahmadi Muslims can openly practice their Islamic faith. As such, ], a neighbourhood on ] in ], Israel, acts as the Middle Eastern headquarters of the Community.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.haifatrail.com/haifa-trail-segment14-eng.htm#./images/sect-14/Haifa-Trail-Sect14-P1610817.jpg | title=Kababir and Central Carmel – Multiculturalism on the Carmel | access-date=17 February 2015}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.visit-haifa.org/eng/Kababir | title=Visit Haifa | access-date=17 February 2015}}</ref> It is unknown how many Israeli Ahmadis there are, although it is estimated there are about 2,200 Ahmadis in Kababir.<ref name="israelandyou">{{cite web|url=http://www.israelandyou.com/kababir/ |title=Kababir |publisher=Israel and You |access-date=17 February 2015 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150130170337/http://www.israelandyou.com/kababir/ |archive-date=30 January 2015 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Druze=== | |||

| Nevertheless, Christianity in Israel reveals the vestiges of the land's past and present interaction with Christian powers. Most Christians in Israel belong primarily to branches of the ]es that oversee a variety of churches, monasteries, seminaries, and religious institutions all over the land, particularly in ], because it was the ] (known as the ''Eastern Roman Empire'') that controlled most of the Middle East from the fourth century until the 1400s, and it was that empire which embraced and nurtured the denomination of Christianity known as ''Eastern Orthodoxy'' following the ] of ], until its rule was broken first by the ]s in ], and then for all time by the Islamic ]. In the nineteenth century the Russian Empire constituted itself the guardian of the interests of Christians living in the Holy Land, and even today large amounts of Jerusalem real estate (including the site of the ] building) are owned by the Russian Orthodox Church. | |||

| {{Main|Druze in Israel}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Israel is home to about 143,000 ] who follow their own ] religion.<ref name="CBS13">{{cite web|url=https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/mediarelease/DocLib/2019/122/11_19_122b.pdf|title=The Druze population in Israel - a collection of data on the occasion of the Prophet Shuaib holiday|date=17 April 2019|work=CBS - Israel|publisher=]|access-date=8 May 2019}}</ref> Self described as "Ahl al-Tawhid", and "al-Muwaḥḥidūn" (meaning "People of Oneness", and "Unitarians", respectively), the Druze live mainly in the ], southern ], and northern occupied ].<ref name="idr">''Identity Repertoires among Arabs in Israel'', Muhammad Amara and Izhak Schnell; ''Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies'', Vol. 30, 2004</ref> Since 1957, the Israeli government has also designated the Druze a distinct ethnic community, at the request of the community's leaders. Until his death in 1993, the Druze community in Israel was led by Shaykh ], a charismatic figure regarded by many within the Druze community internationally as the preeminent religious leader of his time.<ref>{{cite news| url=https://www.nytimes.com/1993/10/05/obituaries/sheik-amin-tarif-arab-druse-leader-in-israel-dies-at-95.html | work=The New York Times | title=Sheik Amin Tarif, Arab Druse Leader In Israel, Dies at 95 | first=Eric | last=Pace | date=5 October 1993 | access-date=29 March 2010}}</ref> Even though the faith originally developed out of ], ] do not identify as ],<ref>{{cite book|title=America & Islam: Soundbites, Suicide Bombs and the Road to Donald Trump|first=Lawrence|last= Pintak|year= 2019| isbn= 9781788315593| page =86|publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=The Templar Spirit: The Esoteric Inspiration, Rituals and Beliefs of the Knights Templar|first=Margaret|last= Jonas|year= 2011| isbn= 9781906999254| page =83|publisher=Temple Lodge Publishing|quote= often they are not regarded as being Muslim at all, nor do all the Druze consider themselves as Muslim}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Are the Druze People Arabs or Muslims? Deciphering Who They Are |url=https://www.arabamerica.com/are-the-druze-people-arabs-or-muslims-deciphering-who-they-are/ |website=Arab America |access-date=13 April 2020 |language=en |date=8 August 2018}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=The Middle East Today: Political, Geographical and Cultural Perspectives| first=Dona|last= J. Stewart|year=2008| isbn=9781135980795| page = 33|publisher=Routledge|quote= Most Druze do not consider themselves Muslim. Historically they faced much persecution and keep their religious beliefs secrets.}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=The Oxford Handbook of American Islam| first=Yvonne |last=Yazbeck Haddad|year=2014| isbn=9780199862634| page = 142|publisher=Oxford University Press|quote=While they appear parallel to those of normative Islam, in the Druze religion they are different in meaning and interpretation. The religion is considered distinct from the Ismaili as well as from other Muslims belief and practice... Most Druze consider themselves fully assimilated in American society and do not necessarily identify as Muslims..}}</ref> and they do not accept the ].<ref>{{cite book|title= The Political Role of Minority Groups in the Middle East|first=Ronald|last= De McLaurin|year= 1979| isbn= 9780030525964| page =114 |publisher=Michigan University Press|quote= Theologically, one would have to conclude that the Druze are not Muslims. They do not accept the five pillars of Islam. In place of these principles the Druze have instituted the seven precepts noted above.}}</ref> | |||

| ===Baháʼí Faith=== | |||

| In between, there were periods in history when Muslims and Christians vied for control of the Holy Land. The ]s by ] from the 11th to the 13th centuries brought the influence and power of the ] to the area. For example, the ] is still one of the Roman Catholic ]. The Patriarchate of Jerusalem is the oldest Eastern Catholic Patriarchates (though the Patriarchs have not actually been resident in Jerusalem for much of the institution's history), and the only one that follows the ]. During the existence of the ], the Patriarchate was divided into four archdioceses - the ], the ], ], and the ] - and a number of dioceses, spreading the seeds of this kind of Christianity in these domains, and also the ]. In ], the ] allowed the Catholic Church to re-establish its hierarchy in Palestine. Other ancient churches, such as the Armenian, Coptic and Ethiopian churches, are also well represented, especially in Jerusalem. | |||

| {{See also|Baháʼí World Centre}} | |||

| ] from the upper ] on ], Haifa]] | |||

| ] from the International Archives building]] | |||

| The ] has its ] in Haifa on land it has owned since ] imprisonment in ] in the early 1870s by the Ottoman Empire.{{citation needed|date=November 2020}} The progress of these properties in construction projects was welcomed by the mayor of Haifa ] (1993–2003).<ref name=Berry2004>{{cite journal | |||

| The upshot of the long Byzantine Eastern Orthodox history and then the Crusader Roman Catholic presence in areas of the Middle East including Israel, is that many local people accepted and clung to these official forms of Christianity as their own faith until the present time. During times of danger, many Christians were also able to worship or take refuge in well-fortified or secluded chuches that had remained committed to serving their loyal flocks in spite of being surrounded by a massive growing Islamic population. | |||

| | author=Adam Berry | |||

| | title =The Baháʼí Faith and its relationship to Islam, Christianity, and Judaism: A brief history | |||

| | journal =International Social Science Review | |||

| | date = 22 September 2004 | |||

| | url =http://bahai-library.com/berry_bahai_islam_christianity | |||

| | issn =0278-2308 | |||

| | access-date = 5 March 2015}}</ref> As far back as 1969 a presence of Baháʼís was noted mostly centered around Haifa in Israeli publications.<ref>{{cite book|author1=Zev Vilnay|author2=Karṭa (Firm)|title=The new Israel atlas: Bible to present day|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NIg8AAAAIAAJ&q=%22Bahais+in+israel%22|publisher=Israel Universities Press|page=38|year=1969}}</ref> Several newspapers in Israel since then have noted the presence of Baháʼís in the Haifa area of some 6-700 volunteers with no salaries, getting only living allowances and housing,<ref>* {{cite news | |||

| | author=Nechemia Meyers | |||

| | title =Peace to all nations - Baha'is Establish Israel's Second Holy Mountain | |||

| | newspaper =The World & I | |||

| | date =1995 | |||

| | url =http://bahai-library.com/newspapers/1995/110095.html | |||

| | access-date = 5 March 2015}}</ref><ref name=Fourth>{{cite news | |||

| | author=Donald H. Harrison | |||

| | title =The Fourth Faith | |||

| | newspaper =Jewish Sightseeing | |||

| | location = Haifa, Israel | |||

| | date =3 April 1998 | |||

| | url =http://bahai-library.com/newspapers/1998/980403.html | |||