| Revision as of 03:22, 31 May 2007 editAchillobator (talk | contribs)93 edits →Dragons in world mythology← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 20:43, 23 December 2024 edit undo5.113.106.98 (talk) Coreect it wrong informations was thereTags: Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Legendary large magical creature}} | |||

| {{Unreferenced|date=April 2007}} | |||

| {{distinguish|Agamidae{{!}}Dragon lizard|Komodo dragon|Draconian (disambiguation){{!}}Draconian|Dracones|Dragoon}} | |||

| {{Original research}} | |||

| {{about|the legendary creature}} | |||

| {{otheruses}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=July 2020}} | |||

| ]'', color engraving on wood, Chinese school, nineteenth Century]] | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| The '''dragon''' is a ] typically depicted as a large and powerful ] or other ] with ] or ] qualities. | |||

| | align = right | |||

| | direction = vertical | |||

| | width = 200 | |||

| | image1 = Friedrich-Johann-Justin-Bertuch Mythical-Creature-Dragon 1806.jpg | |||

| | caption1 = Illustration of a winged, fire-breathing dragon by ] from 1806 | |||

| | image2 = Ninedragonwallpic1.jpg | |||

| | caption2 = ]-era carved imperial Chinese dragons at ], ], ] | |||

| }} | |||

| A '''dragon''' is a ] ] that appears in the ] of multiple cultures worldwide. Beliefs about dragons vary considerably through regions, but ] since the ] have often been depicted as winged, horned, and capable of breathing fire. ] are usually depicted as wingless, four-legged, ] creatures with above-average intelligence. Commonalities between dragons' traits are often a hybridization of ], ]ian, and ] features. | |||

| {{TOC limit|3}} | |||

| ==Etymology== | |||

| ] word {{lang|ang|dracan}} in '']''<ref>, 1876, p. 196.</ref>]] | |||

| The word ''dragon'' entered the ] in the early 13th century from ] {{lang|fro|dragon}}, which, in turn, comes from ] {{lang|la|draco}} (genitive {{lang|la|draconis}}), meaning "huge serpent, dragon", from ] {{lang|grc|]}}, {{transliteration|grc|drákōn}} (genitive {{lang|grc|]}}, {{transliteration|grc|drákontos}}) "serpent".{{sfn|Ogden|2013|page=4}}<ref name="LiddelScott"> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100620113648/http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0057%3Aentry%3Ddra%2Fkwn2 |date=20 June 2010 }}, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, ''A Greek-English Lexicon'', at Perseus project</ref> The Greek and Latin term referred to any great serpent, not necessarily mythological.{{sfn|Ogden|2013|pages=2–4}} The Greek word {{lang|grc|δράκων}} is most likely derived from the Greek verb {{lang|grc|]}} ({{transliteration|grc|dérkomai}}) meaning "I see", the ] form of which is {{lang|grc|ἔδρακον}} ({{transliteration|grc|édrakon}}).<ref name="LiddelScott"/> This is thought to have referred to something with a "deadly glance",<ref>{{Cite dictionary|url=https://www.etymonline.com/word/dragon|title=dragon|dictionary=Online Etymology Dictionary|access-date=15 October 2021|archive-date=9 October 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211009073530/https://www.etymonline.com/word/dragon|url-status=live}}</ref> or unusually bright<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/morph?l=de%2Frkomai&la=greek&can=de%2Frkomai0&prior=to/de&d=Perseus:text:1999.01.0041:card=699&i=1#lexicon|title=Greek Word Study Tool|access-date=15 October 2021|archive-date=9 April 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220409213126/https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/morph?l=de%2Frkomai&la=greek&can=de%2Frkomai0&prior=to%2Fde&d=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0041%3Acard%3D699&i=1#lexicon|url-status=live}}</ref> or "sharp"<ref>{{Cite web|url = https://blog.oup.com/2015/04/st-georges-day-dragon-etymology/|title = Guns, herbs, and sores: Inside the dragon's etymological lair|date = 25 April 2015|access-date = 15 October 2021|archive-date = 17 November 2021|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20211117000637/https://blog.oup.com/2015/04/st-georges-day-dragon-etymology/|url-status = live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Wyld |first1=Henry Cecil |title=The Universal Dictionary of the English Language |date=1946 |page=334 |url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.64081}}</ref> eyes, or because a snake's eyes appear to be always open; each eye actually sees through a big transparent scale in its eyelids, which are permanently shut. The Greek word probably derives from an ] base {{lang|ine-x-proto|*derḱ-}} meaning "to see"; the ] root {{lang|sa|दृश्}} ({{transliteration|sa|dr̥ś-}}) also means "to see".<ref>{{cite book |last1=Skeat |first1=Walter W. |title=An etymological dictionary of the English language |date=1888 |publisher=Clarendon Press |location=Oxford |page=178 |url=https://archive.org/details/etymologicaldict00skeauoft}}</ref> | |||

| ==Overview== | ==Overview== | ||

| ] hang outside ], but actually belong to a ] mammal.]] | |||

| ] (a dragon swallowing its own tail) by ], in ] tract titled '']''.]] | |||

| Draconic creatures appear in virtually all cultures around the globe{{sfn|Malone|2012|page=96}} and the earliest attested reports of draconic creatures resemble giant snakes. Draconic creatures are first described in the mythologies of the ] and appear in ] and literature. Stories about ] slaying giant serpents occur throughout nearly all Near Eastern and ] mythologies. Famous prototypical draconic creatures include the '']'' of ancient ]; ] in ]; ] in the '']''; the ] in the ]; ] in the ] region in ]; ], ], ] and the ] in ]; ] in ]; ] in ]; ] in ]; ], ], and ] in ]; ] from '']''; and aži and az in ancient Persian mythology, closely related to another mythological figure, called Aži Dahaka or ]. | |||

| Dragons are commonly portrayed as serpentine or reptilian, hatching from ] and possessing extremely large, typically scaly, bodies; they are sometimes portrayed as having large eyes, a feature that is the origin for the word for dragon in many cultures, and are often (but not always) portrayed with wings and a fiery breath. Some dragons do not have wings at all, but look more like long snakes. Dragons can have a variable number of legs: none, two, four, or more when it comes to early European literature. Modern depictions of dragons are very large in size, but some early European depictions of dragons were only the size of bears, or, in some cases, even smaller, around the size of a butterfly. | |||

| Nonetheless, scholars dispute where the idea of a dragon originates from,{{sfn|Malone|2012|page=98}} and a wide variety of hypotheses have been proposed.{{sfn|Malone|2012|page=98}} | |||

| Although dragons (or dragon-like creatures) occur in many legends around the world, different cultures have varying stories about monsters that have been grouped together under the dragon label. ]s ({{zh-stp|t=龍|s=龙|p=lóng}}), and Eastern dragons generally, are usually seen as benevolent, whereas ]s are usually malevolent (there are of course exceptions to these rules). Malevolent dragons also occur in ] (see ]) and other cultures. | |||

| In his book '']'' (2000), anthropologist David E. Jones suggests a hypothesis that humans, like ]s, have inherited instinctive reactions to snakes, ], and ].{{sfn|Jones|2000|page=32-40}} He cites a study which found that approximately 39 people in a hundred are afraid of snakes{{sfn|Jones|2000|page=63}} and notes that fear of snakes is especially prominent in children, even in areas where snakes are rare.{{sfn|Jones|2000|page=63}} The earliest attested dragons all resemble snakes or have snakelike attributes.{{sfn|Jones|2000|pages=166–168}} Jones therefore concludes that dragons appear in nearly all cultures because humans have an innate fear of snakes and other animals that were major predators of humans' primate ancestors.{{sfn|Jones|2000|page=32}} Dragons are usually said to reside in "dark caves, deep pools, wild mountain reaches, sea bottoms, haunted forests", all places which would have been fraught with danger for early human ancestors.{{sfn|Jones|2000|page=108}} | |||

| Dragons are particularly popular in China. Along with the ], the dragon was a symbol of the Chinese emperors. Dragon costumes manipulated by several people are a common sight at Chinese festivals. | |||

| In her book ''The First Fossil Hunters: Dinosaurs, Mammoths, and Myth in Greek and Roman Times'' (2000), ] argues that some stories of dragons may have been inspired by ancient discoveries of fossils belonging to ]s and other prehistoric animals.{{sfn|Mayor|2000|pages=xiii–xxii}} She argues that the dragon lore of northern India may have been inspired by "observations of oversized, extraordinary bones in the fossilbeds of the ] below the ]"{{sfn|Mayor|2000|page=xxii}} and that ancient Greek artistic depictions of the ] may have been influenced by fossils of '']'', an extinct species of giraffe whose fossils are common in the Mediterranean region.{{sfn|Mayor|2000|page=xxii}} In China, a region where fossils of large prehistoric animals are common, these remains are frequently identified as "dragon bones"{{sfn|Mayor|2000|page=xix}} and are commonly used in ].{{sfn|Mayor|2000|page=xix}} Mayor, however, is careful to point out that not all stories of dragons and giants are inspired by fossils{{sfn|Mayor|2000|page=xix}} and notes that Scandinavia has many stories of dragons and sea monsters, but has long "been considered barren of large fossils."{{sfn|Mayor|2000|page=xix}} In one of her later books, she states that, "Many dragon images around the world were based on folk knowledge or exaggerations of living reptiles, such as ]s, ]s, ]s, ]s, or, in California, ], though this still fails to account for the Scandinavian legends, as no such animals (historical or otherwise) have ever been found in this region."{{sfn|Mayor|2005|page=149}} | |||

| Dragons are often held to have major spiritual significance in various religions and cultures around the world. In many ] and ] cultures dragons were, and in some cultures still are, revered as representative of the primal forces of ] and the ]. They are associated with ]—often said to be wiser than humans—and longevity. They are commonly said to possess some form of ] or other supernormal power, and are often associated with wells, rain, and rivers. In some cultures, they are said to be capable of human speech. They are also said to be able to talk to all animals. | |||

| Robert Blust in ''The Origin of Dragons'' (2000) argues that, like many other creations of traditional cultures, dragons are largely explicable as products of a convergence of rational pre-scientific speculation about the world of real events. In this case, the event is the natural mechanism governing rainfall and drought, with particular attention paid to the phenomenon of the rainbow.<ref>Blust, Robert. "The Origin of Dragons". ''Anthropos'', vol. 95, no. 2, 2000, pp. 519–536. ''JSTOR'', www.jstor.org/stable/40465957. Accessed 6 June 2020.</ref> | |||

| <!--Dragons are very popular characters in ], ] and ] today. WE discuss fiction in another section later, and have a whole other page on them, do not need to bring this up all over the place--> | |||

| The term '']'', for infantry that move around by ] yet still fight as foot soldiers, is derived from their early ], the "dragon", a wide-bore musket that spat flame when it fired, and was thus named for the mythical creature. | |||

| == |

==Egypt== | ||

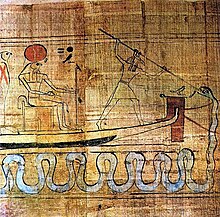

| ] spearing the serpent ] as he attacks the ] of ]]] | |||

| ]]] | |||

| In ], ] or Apophis is a giant serpentine creature who resides in the ], the Egyptian Underworld.{{sfn|Ogden|2013|page=11}}{{sfn|Niles|2013|page=35}} The Bremner-Rhind papyrus, written around 310 BC, preserves an account of a much older Egyptian tradition that the setting of the sun is caused by ] descending to the Duat to battle Apep.{{sfn|Ogden|2013|page=11}}{{sfn|Niles|2013|page=35}} In some accounts, Apep is as long as the height of eight men with a head made of ].{{sfn|Niles|2013|page=35}} Thunderstorms and earthquakes were thought to be caused by Apep's roar{{sfn|Niles|2013|page=36}} and ]s were thought to be the result of Apep attacking Ra during the daytime.{{sfn|Niles|2013|page=36}} In some myths, Apep is slain by the god ].{{sfn|Niles|2013|pages=35–36}} ] is another giant serpent who guards the Duat and aided Ra in his battle against Apep.{{sfn|Niles|2013|page=36}} Nehebkau was so massive in some stories that the entire earth was believed to rest atop his coils.{{sfn|Niles|2013|page=36}} Denwen is a giant serpent mentioned in the ] whose body was made of fire and who ignited a conflagration that nearly destroyed all the gods of the Egyptian pantheon.{{sfn|Niles|2013|pages=36–37}} He was ultimately defeated by the ], a victory which affirmed the Pharaoh's divine right to rule.{{sfn|Niles|2013|page=37}} | |||

| ] slaying ]'', by ]]]In ] symbolism, dragons were often symbolic of ] and treachery, but also of anger and envy, and eventually symbolized great calamity. Several heads were symbolic of decadence and oppression, and also of ]. They also served as symbols for independence, leadership and strength. Many dragons also represent wisdom; slaying a dragon not only gave access to its treasure hoard, but meant the hero had bested the most cunning of all creatures. In some cultures, especially Chinese, or around the Himalayas, dragons are considered to represent good luck. Dragons are depicted in medieval symbolism to be the size of a bear of smaller. Most dragons posses magical abilities. Dragons also represent envy, treachery, and anger. | |||

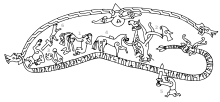

| The ] was a well-known Egyptian symbol of a serpent swallowing its own tail.{{sfn|Hornung|2001|page=13}} The precursor to the ouroboros was the "Many-Faced",{{sfn|Hornung|2001|page=13}} a serpent with five heads, who, according to the ], the oldest surviving ], was said to coil around the corpse of the sun god Ra protectively.{{sfn|Hornung|2001|page=13}} The earliest surviving depiction of a "true" ouroboros comes from the gilded shrines in ] of ].{{sfn|Hornung|2001|page=13}} In the early centuries AD, the ouroboros was adopted as a symbol by ] Christians{{sfn|Hornung|2001|page=44}} and chapter 136 of the '']'', an early Gnostic text, describes "a great dragon whose tail is in its mouth".{{sfn|Hornung|2001|page=44}} In medieval alchemy, the ouroboros became a typical western dragon with wings, legs, and a tail.{{sfn|Hornung|2001|page=13}} A famous image of the dragon gnawing on its tail from the eleventh-century ] was copied in numerous works on alchemy.{{sfn|Hornung|2001|page=13}} | |||

| ] in the '']'' viewed the dragon as a symbol of divinity or transcendence because it represents the unity of Heaven and Earth by combining the serpent form (earthbound) with the bat/bird form (airborne). | |||

| ==West Asia== | |||

| Dragons embody both male and female traits, as in the example from Aboriginal myth that raises baby humans to adulthood, training them for survival in the world.<ref>(Littleton, 2002, p. 646)</ref> Another striking illustration of the way dragons are portrayed is their ability to breathe fire but live in the ocean. Dragons represent the joining of the opposing forces of the ]. | |||

| ===Mesopotamia=== | |||

| ]'' is a serpentine, draconic monster from ] with the body and neck of a snake, the forelegs of a lion, and the hind-legs of a bird.{{sfn|Black|Green|1992|page=166}} Here it is shown as it appears in the ] from the city of ].{{sfn|Black|Green|1992|page=166}}]] | |||

| Ancient people across the ] believed in creatures similar to what modern people call "dragons".{{sfn|Black|Green|1992|page=71}} These ancient people were unaware of the existence of ]s or similar creatures in the distant past.{{sfn|Black|Green|1992|page=71}} References to dragons of both benevolent and malevolent characters occur throughout ancient ]n literature.{{sfn|Black|Green|1992|page=71}} In ], great kings are often compared to the '']'', a gigantic, serpentine monster.{{sfn|Black|Green|1992|page=71}} A draconic creature with the foreparts of a lion and the hind-legs, tail, and wings of a bird appears in ] from the ] ({{circa}} 2334 – 2154 BC) until the ] (626 BC–539 BC).{{sfn|Black|Green|1992|page=121}} The dragon is usually shown with its mouth open.{{sfn|Black|Green|1992|page=121}} It may have been known as the ''(ūmu) nā’iru'', which means "roaring weather beast",{{sfn|Black|Green|1992|page=121}} and may have been associated with the god ] (Hadad).{{sfn|Black|Green|1992|page=121}} A slightly different lion-dragon with two horns and the tail of a scorpion appears in art from the ] (911 BC–609 BC).{{sfn|Black|Green|1992|page=121}} A relief probably commissioned by ] shows the gods ], ], and Adad standing on its back.{{sfn|Black|Green|1992|page=121}} | |||

| Another draconic creature with horns, the body and neck of a snake, the forelegs of a lion, and the hind-legs of a bird appears in Mesopotamian art from the Akkadian Period until the ] (323 BC–31 BC).{{sfn|Black|Green|1992|page=166}} This creature, known in ] as the '']'', meaning "furious serpent", was used as a symbol for particular deities and also as a general protective emblem.{{sfn|Black|Green|1992|page=166}} It seems to have originally been the attendant of the Underworld god ],{{sfn|Black|Green|1992|page=166}} but later became the attendant to the ] storm-god ], as well as, later, Ninazu's son ], the Babylonian ] ], the scribal god ], and the Assyrian national god Ashur.{{sfn|Black|Green|1992|page=166}} | |||

| Yet another symbolic view of dragons is the ], or the dragon encircling and eating its own tail. When shaped like this the dragon becomes a symbol of eternity, natural cycles, and completion. | |||

| Scholars disagree regarding the appearance of ], the Babylonian goddess personifying primeval chaos, slain by Marduk in the Babylonian creation epic '']''.{{sfn|Black|Green|1992|page=177}}{{sfn|Fontenrose|1980|page=153}} She was traditionally regarded by scholars as having had the form of a giant serpent,{{sfn|Fontenrose|1980|page=153}} but several scholars have pointed out that this shape "cannot be imputed to Tiamat with certainty"{{sfn|Fontenrose|1980|page=153}} and she seems to have at least sometimes been regarded as anthropomorphic.{{sfn|Black|Green|1992|page=177}}{{sfn|Fontenrose|1980|page=153}} Nonetheless, in some texts, she seems to be described with horns, a tail, and a hide that no weapon can penetrate,{{sfn|Black|Green|1992|page=177}} all features which suggest she was conceived as some form of dragoness.{{sfn|Black|Green|1992|page=177}} | |||

| ===In Christianity=== | |||

| The Latin word for a dragon, ''draco'' (]: ''draconis''), actually means ''snake'' or ''serpent'', emphasizing the European association of dragons with snakes, not lizards or dinosaurs as they are commonly associated with today. The Medieval Biblical interpretation of the ] being associated with the serpent who tempted ] and ], thus gave a snake-like dragon connotations of evil. Generally speaking, Biblical literature itself did not portray this association (save for the ], whose treatment of dragons is detailed below). The demonic opponents of ], ], or good Christians have commonly been portrayed as reptilian or chimeric. | |||

| ===Levant=== | |||

| In the ] Chapter 41, there are references to a sea monster ], which has some dragon-like characteristics. | |||

| ]'' (1865) by ]]] | |||

| In the mythologies of the ] region, specifically the ] from the ], the sea-dragon ] is described as "the twisting serpent / the powerful one with seven heads."{{sfn|Ballentine|2015|page=130}} In ''KTU'' 1.5 I 2–3, Lōtanu is slain by the storm-god ],{{sfn|Ballentine|2015|page=130}} but, in ''KTU'' 1.3 III 41–42, he is instead slain by the virgin warrior goddess ].{{sfn|Ballentine|2015|page=130}} | |||

| In the ], in the ], ], Psalm 74:13–14, the sea-dragon ], is slain by ], god of the kingdoms of ] and ], as part of the creation of the world.{{sfn|Ballentine|2015|page=130}}{{sfn|Day|2002|page=103}} Isaiah describes Leviathan as a {{lang|he-Latn|tanin}} ({{lang|he|תנין}}), which is translated as "sea monster", "serpent", or "dragon".<ref name="tanin-translation">{{cite book | last=Brown | first=Francis | last2=Gesenius | first2=Wilhelm | last3=Driver | first3=Samuel Rolles | last4=Briggs | first4=Charles Augustus | title=A Hebrew and English lexicon of the Old Testament | publisher=Oxford university Press | publication-place=Oxford | date=1906 | isbn=0-19-864301-2 | language=he|url=https://www.sefaria.org/BDB%2C_%D7%AA%D6%B7%D6%BC%D7%A0%D6%B4%D6%BC%D7%99%D7%9F.1?lang=bi&with=About&lang2=en}}</ref> In Isaiah 27:1, Yahweh's destruction of Leviathan is foretold as part of his impending overhaul of the universal order:{{sfn|Ballentine|2015|pages=129–130}}{{sfn|Ogden|2013|page=14}} | |||

| In ], an enormous red beast with seven heads is described, whose tail sweeps one third of the stars from heaven down to earth (held to be symbolic of the fall of the ]s, though not commonly held among biblical scholars). In most translations, the word "dragon" is used to describe the beast, since in the original ] the word used is ''drakon'' (δράκον). | |||

| {{Verse translation|lang1=he|rtl1=y|head1=Original Hebrew text|attr1={{bibleverse||Isaiah|27:1|HE}}|head2=English | |||

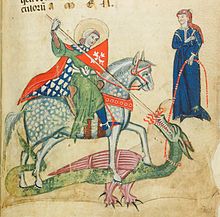

| In ], some Catholic ]s are depicted in the act of killing a dragon. This is one of the common aspects of ] in ] ]ic iconography,<ref name="CatchPenny_Slay">{{cite web | url = http://www.catchpenny.org/slay.html | title = Slaying the Dragon | accessdate = 2007-03-17 | last = Orcutt | first = Larry | year = 2002 }}</ref> on the ], and in ] and ] legend. In ], ], first bishop of the city of ], is also depicted slaying a dragon.<ref>http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/06137a.htm</ref> ], ], ], Saint ], Saint ], and ] were also venerated as dragon-slayers. | |||

| |בַּיּוֹם הַהוּא יִפְקֹד יְהוָה בְּחַרְבּוֹ הַקָּשָׁה וְהַגְּדוֹלָה וְהַחֲזָקָה, עַל לִוְיָתָן נָחָשׁ בָּרִחַ, וְעַל לִוְיָתָן, נָחָשׁ עֲקַלָּתוֹן; וְהָרַג אֶת-הַתַּנִּין, אֲשֶׁר בַּיָּם | |||

| |In that day the LORD will take His sharp, great, and mighty sword, and bring judgment on Leviathan the fleeing serpent — Leviathan the coiling serpent — and He will slay the dragon of the sea.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://biblehub.com/bsb/isaiah/27.htm |title=Isaiah 27 BSB |author=<!--Not stated--> |date= |website=biblehub.com |publisher=Online Parallel Bible Project |access-date=25 Jun 2024 |quote=}}</ref>}} | |||

| Job 41:1–34 contains a detailed description of the Leviathan, who is described as being so powerful that only Yahweh can overcome it.{{sfn|Day|2002|page=102}} Job 41:19–21 states that the Leviathan exhales fire and smoke, making its identification as a mythical dragon clearly apparent.{{sfn|Day|2002|page=102}} In some parts of the Old Testament, the Leviathan is historicized as a symbol for the nations that stand against Yahweh.{{sfn|Day|2002|page=103}} Rahab, a synonym for "Leviathan", is used in several Biblical passages in reference to ].{{sfn|Day|2002|page=103}} Isaiah 30:7 declares: "For Egypt's help is worthless and empty, therefore I have called her 'the silenced ]'."{{sfn|Day|2002|page=103}} Similarly, Psalm 87:3 reads: "I reckon Rahab and Babylon as those that know me..."{{sfn|Day|2002|page=103}} In Ezekiel 29:3–5 and Ezekiel 32:2–8, the ] of Egypt is described as a "dragon" (''tannîn'').{{sfn|Day|2002|page=103}} In the ] story of ] from the ], the prophet ] sees a dragon being worshipped by the Babylonians.{{sfn|Morgan|2009|page=}} Daniel makes "cakes of pitch, fat, and hair";{{sfn|Morgan|2009|page=}} the dragon eats them and bursts open.<ref>Daniel 14:23–30</ref>{{sfn|Morgan|2009|page=}} | |||

| However, some say that dragons were good, before they ], as humans did from the Garden of Eden after Adam and Eve's Original Sin was committed. Also contributing to the good dragon argument in Christianity is the fact that, if they did exist, they were created as were any other creature, as seen in ], a contemporary Christian book series by author ]. | |||

| === |

===Iran=== | ||

| ] (Avestan Great Snake) is a dragon or demonic figure in the texts and mythology of Zoroastrian Persia, where he is one of the subordinates of Angra Mainyu. Alternate names include Azi Dahak, Dahaka, and Dahak. Aži (nominative ažiš) is the Avestan word for "serpent" or "dragon.<ref>For Azi Dahaka as dragon see: Ingersoll, Ernest, et al., (2013). The Illustrated Book of Dragons and Dragon Lore. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN B00D959PJ0</ref> The Avestan term Aži Dahāka and the Middle Persian azdahāg are the sources of the Middle Persian Manichaean demon of greed "Az", Old Armenian mythological figure Aždahak, Modern Persian 'aždehâ/aždahâ', Tajik Persian 'azhdahâ', Urdu 'azhdahā' (اژدها). | |||

| The years ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] etc. (every 12 years — 8 ]) are considered the ] in the ]. | |||

| The name also migrated to Eastern Europe, assumed the form "azhdaja" and the meaning "dragon", "dragoness" or "water snake" in the Balkanic and Slavic languages.<ref>Appears numerous time in, for example: D. N. MacKenzie, Mani's Šābuhragān, pt. 1 (text and translation), BSOAS 42/3, 1979, pp. 500–34, pt. 2 (glossary and plates), BSOAS 43/2, 1980, pp. 288–310.</ref><ref>Detelić, Mirjana. "St Paraskeve in the Balkan Context" In: Folklore 121, no. 1 (2010): 101 (footnote nr. 12). Accessed March 24, 2021. {{JSTOR|29534110}}.</ref><ref>Kropej, Monika. ''''. Ljubljana: Institute of Slovenian Ethnology at ZRC SAZU. 2012. p. 102. {{ISBN|978-961-254-428-7}}.</ref> | |||

| Despite the negative aspect of Aži Dahāka in mythology, dragons have been used on some banners of war throughout the history of Iranian peoples. | |||

| The Chinese zodiac purports that people born in the Year of the Dragon are healthy, energetic, excitable, short-tempered, and stubborn. They are also supposedly honest, sensitive, brave, and inspire confidence and trust. The Chinese zodiac purports that people whose zodiac sign is the dragon are the most eccentric of any in the eastern zodiac. They supposedly neither borrow money nor make flowery speeches, but tend to be soft-hearted which sometimes gives others an advantage over them. They are purported to be compatible with people whose zodiac sign is of the ], ], ], and ]. | |||

| The ] group of pterosaurs are named from a Persian word for "dragon" that ultimately comes from Aži Dahāka. | |||

| ===In East Asia=== | |||

| {{main|Chinese dragon|Japanese dragon}} | |||

| Dragons are commonly symbols of good luck or health in some parts of ], and are also sometimes worshipped. Asian dragons are considered as mythical rulers of weather, specifically rain and water, and are usually depicted as the guardians of ]s. | |||

| In Persian ] literature, ] writes in his '']''<ref>III: 976–1066; V: 120</ref> that the dragon symbolizes the sensual soul ('']''), greed and lust, that need to be mortified in a spiritual battle.<ref>{{Cite book |publisher = University of North Carolina Press |ol = 5422370M |isbn = 0807812234 |location = Chapel Hill |title = Mystical dimensions of Islam |url = https://archive.org/details/137665622MysticalDimensionsOfIslamAnnemarieSchimmel |last=Schimmel |first=Annemarie |lccn = 73016112 |date = 1975 |author-link = Annemarie Schimmel |access-date = 16 October 2022 | pages=111–114}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |author=Savi, Julio |year=2008 |title=Towards the Summit of Reality |publisher=George Ronald |location=Oxford, UK |isbn=978-0-85398-522-8 |ol=23179261M }}</ref> | |||

| In ], as well as in ] and ], the ] is one of the ] of the ], representing ], the element of ] and the ]. Chinese dragons are often shown with large pearls in their grasp, though some say that it is really the dragon's egg. The Chinese believed that the dragons lived underwater most of the time, and would sometimes offer ] as a gift to the dragons. The dragons were not shown with wings like the European dragons because it was believed they could fly using magic. | |||

| ] | |||

| A ''Yellow dragon'' (Huang long) with five claws on each foot, on the other hand, represents the change of seasons, the element of ] (the Chinese 'fifth element') and the center. Furthermore, it symbolizes imperial authority in ], and indirectly the ] as well. Chinese people often use the term "''']'''" as a sign of ethnic identity. The dragon is also the symbol of royalty in ] (whose sovereign is known as ], or Dragon King). | |||

| In Ferdowsi's ''],'' the ] hero ] must slay an 80-meter-long dragon (which renders itself invisible to human sight) with the aid of his legendary horse, ]. As Rostam is sleeping, the dragon approaches; Rakhsh attempts to wake Rostam, but fails to alert him to the danger until Rostam sees the dragon. Rakhsh bites the dragon, while Rostam decapitates it. This is the third trial of Rostam's ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.bl.uk/learning/cult/inside/gallery/dragon/dragon.html|title=Rakhsh helping Rostam defeat the dragon|website=British Library|access-date=5 May 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190527031848/http://www.bl.uk/learning/cult/inside/gallery/dragon/dragon.html|archive-date=27 May 2019|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=231078&partId=1&searchText=Shahnameh&page=1|title=Rustam killing a dragon|website=British Museum}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.bl.uk/learning/cult/inside/corner/shah/synopsis.html|title=Shahname Synopsis|website=British Library|access-date=5 May 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190501133912/http://www.bl.uk/learning/cult/inside/corner/shah/synopsis.html|archive-date=1 May 2019|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Rostam is also credited with the slaughter of other dragons in the ''Shahnameh'' and in other Iranian oral traditions, notably in the myth of '']''. In this tale, Rostam is still an adolescent and kills a dragon in the "Orient" (either India or China, depending on the source) by forcing it to swallow either ox hides filled with quicklime and stones or poisoned blades. The dragon swallows these foreign objects and its stomach bursts, after which Rostam flays the dragon and fashions a coat from its hide called the ''babr-e bayān''. In some variants of the story, Rostam then remains unconscious for two days and nights, but is guarded by his steed ]. On reviving, he washes himself in a spring. In the ] tradition of the story, Rostam hides in a box, is swallowed by the dragon, and kills it from inside its belly. The king of China then gives Rostam his daughter in marriage as a reward.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/azdaha-dragon-various-kinds#pt1|title=Azdaha|website=Encyclopedia Iranica|access-date=5 May 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190511102415/http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/azdaha-dragon-various-kinds#pt1|archive-date=11 May 2019|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/babr-e-bayan-or-babr|title=Babr-e-Bayan|website=Encyclopedia Iranica|access-date=5 May 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190505023908/http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/babr-e-bayan-or-babr|archive-date=5 May 2019|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ] guarding the Temple of ] in ], ]]] | |||

| ==East Asia== | |||

| In ], the dragon (]: rồng) is the most important and sacred symbol. The dragon is strongly influenced by the ]. According to the ancient ] of the ] people, all Vietnamese people are descended from dragons through ], who married ], a fairy. The eldest of their 100 sons founded the first dynasty of ] Emperors. | |||

| ===China=== | |||

| {{Main|Chinese dragon}} | |||

| ] by ], 1244 AD.]] | |||

| ] from a seventeenth-century edition of the '']'']] | |||

| ]]]The word "dragon" has come to be applied to the ] in ], ] (traditional 龍, simplified 龙, Japanese simplified 竜, ] ''lóng''), which is associated with good fortune, and many ]n deities and demigods have dragons as their personal mounts or companions. Dragons were also identified with the ], who, during later Chinese imperial history, was the only one permitted to have dragons on his house, clothing, or personal articles. | |||

| Archaeologist Zhōu Chong-Fa believes that the Chinese word for dragon is an ] of the sound of thunder<ref>{{Cite web |title=Chinese Dragon Originates From Primitive Agriculture |url=http://www.china.org.cn/english/2001/Feb/7049.htm |access-date=2022-09-11 |website=www.china.org.cn |archive-date=15 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230515054843/http://www.china.org.cn/english/2001/Feb/7049.htm |url-status=live }}</ref> or ''lùhng'' in ].<ref>Guan, Caihua. (2001) ''English-Cantonese Dictionary: Cantonese in Yale Romanization''. {{ISBN|9622019706}}.</ref> | |||

| The Chinese dragon ({{zh|t=龍|s=龙|p=lóng}}) is the highest-ranking creature in the Chinese animal hierarchy. Its origins are vague, but its "ancestors can be found on Neolithic pottery as well as Bronze Age ritual vessels."<ref>Welch, Patricia Bjaaland. ''Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery'', Tuttle Publishing, 2008, p. 121</ref> A number of popular stories deal with the rearing of dragons.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=105}} The '']'', which was probably written during the ], describes a man named Dongfu, a descendant of Yangshu'an, who loved dragons{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=105}} and, because he could understand a dragon's will, he was able to tame them and raise them well.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=105}} He served Emperor Shun, who gave him the family name Huanlong, meaning "dragon-raiser".{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=105}} In another story, ], the fourteenth emperor of the ], was given a male and a female dragon as a reward for his obedience to the god of heaven,{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=105}} but could not train them, so he hired a dragon-trainer named Liulei, who had learned how to train dragons from Huanlong.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=105}} One day, the female dragon died unexpectedly, so Liulei secretly chopped her up, cooked her meat, and served it to the king,{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=105}} who loved it so much that he demanded Liulei to serve him the same meal again.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=105}} Since Liulei had no means of procuring more dragon meat, he fled the palace.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=105}} | |||

| In ], the Bakonawa appears as a gigantic serpent that lives in the sea. Ancient natives believed that the Bakonawa caused the moon or the sun to disappear during an eclipse. | |||

| One of the most famous dragon stories is about the Lord Ye Gao, who loved dragons obsessively, even though he had never seen one.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=106}} He decorated his whole house with dragon motifs{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=106}} and, seeing this display of admiration, a real dragon came and visited Ye Gao,{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=106}} but the lord was so terrified at the sight of the creature that he ran away.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=106}} In Chinese legend, the culture hero ] is said to have been crossing the ], when he saw the '']'', a Chinese horse-dragon with seven dots on its face, six on its back, eight on its left flank, and nine on its right flank.{{sfn|Volker|1975|page=64}} He was so moved by this apparition that, when he arrived home, he drew a picture of it, including the dots.{{sfn|Volker|1975|page=64}} He later used these dots as letters and invented ], which he used to write his book '']''.{{sfn|Volker|1975|page=64}} In another Chinese legend, the physician Ma Shih Huang is said to have healed a sick dragon.{{sfn|Volker|1975|page=62}} Another legend reports that a man once came to the healer Lo Chên-jen, telling him that he was a dragon and that he needed to be healed.{{sfn|Volker|1975|page=62}} After Lo Chên-jen healed the man, a dragon appeared to him and carried him to heaven.{{sfn|Volker|1975|page=62}} | |||

| The ] - a minor ] taking the form of a ] - is common within both the ] and ] traditions. Technically, the naga is not a dragon, though it is often taken as such; the term is ambiguous, and refers both to a ] of people known as 'Nāgas', as well as to ]s and ordinary snakes. Within a ] context, it refers to a deity assuming the form of a serpent with either one or many heads. | |||

| In the '']'', a classic mythography probably compiled mostly during the ], various deities and demigods are associated with dragons.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|pages=103–104}} One of the most famous Chinese dragons is Ying Long ("responding dragon"), who helped the ], the Yellow Emperor, defeat the tyrant ].{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=104}} The dragon ] ("torch dragon") is a god "who composed the universe with his body."{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=104}} In the ''Shanhaijing'', many mythic heroes are said to have been conceived after their mothers copulated with divine dragons, including Huangdi, ], ], and ].{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=104}} The god ] and the emperor ] are both described as being carried by two dragons,{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|pages=104–105}} as are Huangdi, ], ], and Roshou in various other texts.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=105}} According to the '']'', an evil black dragon once caused a destructive deluge,{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=105}} which was ended by the mother goddess ] by slaying the dragon.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=105}} | |||

| Occasionally the ] is depicted as sitting upon the coils of a serpent, with a fan of several serpent heads extending over his body. This is in reference to ], a Nāga that protected ] from the elements during the time of his enlightenment. Separated from the contextualising effect of the Buddha story, people may see only the head and thus infer that Mucalinda is a dragon, rather than a deity in serpentine form. Stairway railings on Buddhist temples will occasionally be worked to resemble the body of a Nāga with the head at the base of the railing. In ], the head of Nāga, in a more impressionistic form, can be seen at the corners of temple roofs, with Nāga’s body forming the ornamentation on roofline eves up to the ]s. | |||

| ] with dragon emblem on his chest. c. 1377]] | |||

| ==Speculation on the origins of dragons== | |||

| A large number of ethnic myths about dragons are told throughout China.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=105}} The '']'', compiled in the fifth century BC by ], reports a story belonging to the Ailaoyi people, which holds that a woman named Shayi who lived in the region around ] became pregnant with ten sons after being touched by a tree trunk floating in the water while fishing.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=104}} She gave birth to the sons and the tree trunk turned into a dragon, who asked to see his sons.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=104}} The woman showed them to him,{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=104}} but all of them ran away except for the youngest, who the dragon licked on the back and named Jiu Long, meaning "sitting back".{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=104}} The sons later elected him king and the descendants of the ten sons became the Ailaoyi people, who ]ed dragons on their backs in honor of their ancestor.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=104}} The ] of southwest China have a story that a divine dragon created the first humans by breathing on monkeys that came to play in his cave.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=105}} The ] have many stories about Short-Tailed Old Li, a black dragon who was born to a poor family in ].{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=106}} When his mother saw him for the first time, she fainted{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=106}} and, when his father came home from the field and saw him, he hit him with a spade and cut off part of his tail.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=106}} Li burst through the ceiling and flew away to the ] in northeast China, where he became the god of that river.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|pages=106–107}} On the anniversary of his mother's death on the Chinese lunar calendar, Old Li returns home, causing it to rain.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=107}} He is still worshipped as a rain god.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=107}} | |||

| It has been suggested that legends of dragons are based upon ordinary creatures coupled with common psychological tendencies amongst disparate groups of humans. | |||

| ] in relation to the central Dragon King of the Earth]] | |||

| Some believe that the dragon may have had a real-life counterpart from which the various legends arose — typically ] or other ] are mentioned as a possibility — but there is no physical evidence to support this claim, only alleged sightings collected by ]. In a common variation of this hypothesis, giant ]s such as ] are substituted for the ]. Some believe dragons are mental manifestations representing an assembly of inherent human fears of reptiles, teeth, claws, size and fire in combination. All of these hypotheses are widely considered to be ]. | |||

| In China, a dragon is thought to have power over rain. Dragons and their associations with rain are the source of the Chinese customs of ] and ]. Dragons are closely associated with rain{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|pages=107–108}} and ] is thought to be caused by a dragon's laziness.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=108}} Prayers invoking dragons to bring rain are common in Chinese texts.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|pages=107–108}} The '']'', attributed to the Han dynasty scholar ], prescribes making clay figurines of dragons during a time of drought and having young men and boys pace and dance among the figurines in order to encourage the dragons to bring rain.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|pages=107–108}} Texts from the ] advise hurling the bone of a tiger or dirty objects into the pool where the dragon lives;{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=108}} since dragons cannot stand tigers or dirt, the dragon of the pool will cause heavy rain to drive the object out.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=108}} Rainmaking rituals invoking dragons are still very common in many Chinese villages, where each village has its own god said to bring rain and many of these gods are dragons.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=108}} The Chinese dragon kings are thought of as the inspiration for the Hindu myth of the naga. {{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=108}} According to these stories, every body of water is ruled by a dragon king, each with a different power, rank, and ability,{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=108}} so people began establishing temples across the countryside dedicated to these figures.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=108}} | |||

| ] performed in ] in the year 2000.]] | |||

| Dinosaur and mammalian fossils were occasionally mistaken as the bones of dragons and other mythological creatures — a discovery in 300 BC in ], ], ], was labeled as such by ].<ref>http://www.abc.net.au/science/k2/moments/s1334145.htm</ref> It is unlikely, however, that these finds alone prompted the legends of such monsters, but they may have served to reinforce them. | |||

| Many traditional Chinese customs revolve around dragons.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|pages=108–109}} During various holidays, including the ] and ], villagers will construct an approximately sixteen-foot-long dragon from grass, cloth, bamboo strips, and paper, which they will parade through the city as part of a ].{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=109}} The original purpose of this ritual was to bring good weather and a strong harvest,{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=109}} but now it is done mostly only for entertainment.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=109}} During the ] festival, several villages, or even a whole province, will hold a ], in which people race across a body of water in boats carved to look like dragons, while a large audience watches on the banks.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=109}} The custom is traditionally said to have originated after the poet ] committed suicide by drowning himself in the ] and people raced out in boats hoping to save him.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=109}} But most historians agree that the custom actually originated much earlier as a ritual to avert ill fortune.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=109}} Starting during the Han dynasty and continuing until the Qing dynasty, the ] gradually became closely identified with dragons,{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=109}} and emperors themselves claimed to be the incarnations of a divine dragon.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=109}} Eventually, dragons were only allowed to appear on clothing, houses, and articles of everyday use belonging to the emperor{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=109}} and any commoner who possessed everyday items bearing the image of the dragon was ordered to be executed.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|page=109}} After the last Chinese emperor was overthrown in 1911, this situation changed and now many ordinary Chinese people identify themselves as descendants of dragons.{{sfn|Yang|An|Turner|2005|pages=109–110}} | |||

| The impression of dragons in a large number of Asian countries has been influenced by Chinese culture, such as Korea, Vietnam, Japan, and so on. Chinese tradition has always used the dragon totem as the national emblem, and the "Yellow Dragon flag" of the Qing dynasty has influenced the impression that China is a dragon in many European countries. | |||

| It has also been suggested by proponents of ] that ]s or ] showers gave rise to legends about fiery serpents in the sky.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} In Old English, comets were sometimes called fyrene dracan or fiery dragons. Volcanic eruptions may have also been{{Fact|date=March 2007}} responsible for reinforcing the belief in dragons, although instances in Europe and Asian countries were rare. | |||

| ===Korea=== | |||

| ==Dragons in world mythology== | |||

| {{Main|Korean dragon}} | |||

| <div align="center"> | |||

| ].]] | |||

| <gallery> | |||

| The Korean dragon is in many ways similar in appearance to other East Asian dragons such as the ] and ]s. It differs from the Chinese dragon in that it developed a longer beard. Very occasionally, a dragon may be depicted as carrying an orb known as the Yeouiju (여의주), the Korean name for the mythical ], in its claws or its mouth. It was said that whoever could wield the Yeouiju was blessed with the abilities of omnipotence and creation at will, and that only four-toed dragons (who had thumbs with which to hold the orbs) were both wise and powerful enough to wield these orbs, as opposed to the lesser, three-toed dragons. As with China, the number nine is significant and auspicious in Korea, and dragons were said to have 81 (9×9) scales on their backs, representing yang essence. Dragons in Korean mythology are primarily benevolent beings related to water and agriculture, often considered bringers of rain and clouds. Hence, many Korean dragons are said to have resided in rivers, lakes, oceans, or even deep mountain ponds. And human journeys to undersea realms, and especially the undersea palace of the Dragon King (용왕), are common in Korean folklore.<ref>{{cite book| last= Hayward | first = Philip| title= Scaled for Success: The Internationalisation of the Mermaid | year = 2018|publisher=Indiana University Press|isbn=978-0861967322}}</ref> | |||

| Image:Marduk and pet.jpg|The ancient ]n god ] and his dragon, from a ]n cylinder seal | |||

| Image:Hopperstad dragon.jpg|Dragon carving on ], ] | |||

| Image:Paolo Uccello 050.jpg|] slaying the dragon, as depicted by ], c. 1470 | |||

| Image:Flag of Wales 2.svg|The red dragon of ], ], on the ] | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| </div> | |||

| In Korean myths, some kings who founded kingdoms were described as descendants of dragons because the dragon was a symbol of the monarch. ], who was the first queen of ], is said to have been born from a ],<ref>]</ref> while the grandmother of ], founder of ], was reportedly the daughter of the dragon king of the West Sea.<ref>The book of the genealogy of ] – ''Pyeonnyeon-Tong-Long'' (편년통록)</ref> And ] of Silla who, on his deathbed, wished to become a dragon of the East Sea in order to protect the kingdom. Dragon patterns were used exclusively by the royal family. The royal robe was also called the dragon robe (용포). In the ], the royal insignia, featuring embroidered dragons, were attached to the robe's shoulders, the chest, and back. The King wore five-taloned dragon insignia while the Crown Prince wore four-taloned dragon insignia.<ref>{{cite book| title=우리 옷 만들기 | year = 2004|publisher=Sungshin Women's University Press|isbn=978-8986092639|pages=25–26 }}</ref> | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| |- | |||

| | colspan="4" style="background-color: #ffa; text-align: center; font-weight: bold;" | ]s | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | '''Naga or Nogo''' | |||

| | Naga is a mythical animal from Indonesian mythology, and the myth encompasses almost all of the islands of Indonesia, especially those who were influenced heavily by Hindu culture. Like its Indian counterpart, it is considered as divine in nature, benevolent, and often associated with sacred mountains, forests, or certain parts of the sea. | |||

| In some parts of Indonesia, Dragon or Naga is depicted as a gigantic serpent with a golden crown on its forehead, and there is a persistent belief among certain peoples that Nagas are still alive in uncharted mountains, lakes and active volcanoes. | |||

| In Java and Bali, dragons represent goodness, and gods send dragons to the earth in order to maintain the force of good and gave people prosperity. | |||

| Some natives claimed sightings of this fabled beast, and considered as a good omen if someone happen to glimpse one of these animals, but misfortune if the dragons talked to them. | |||

| Korean folk mythology states that most dragons were originally ] (이무기), or lesser dragons, which were said to resemble gigantic serpents. There are a few different versions of Korean folklore that describe both what imugis are and how they aspire to become full-fledged dragons. Koreans thought that an Imugi could become a true dragon, ''yong'' or ''mireu'', if it caught a Yeouiju which had fallen from heaven. Another explanation states they are hornless creatures resembling dragons who have been cursed and thus were unable to become dragons. By other accounts, an Imugi is a ''proto-dragon'' which must survive one thousand years in order to become a fully-fledged dragon. In either case, they are said to be large, benevolent, ]-like creatures that live in water or caves, and their sighting is associated with good luck.<ref>{{cite book| last= Seo | first = Yeong Dae| title= 용, 그 신화와 문화 | year = 2002|publisher=Min sokwon|isbn=978-8956380223|page= 85}}</ref> | |||

| ]n myth also involves nagas. Cambodian myth has it that the Cambodian nation began with offspring of a naga and royal human. | |||

| ===Japan=== | |||

| |- | |||

| | |

{{Main|Japanese dragon}} | ||

| ] ({{circa}} 1730 – 1849)]] | |||

| | '''Lóng''' (or '''Lung''') | |||

| Japanese dragon myths amalgamate native legends with imported stories about dragons from China. Like some other dragons, most Japanese dragons are ] associated with rainfall and bodies of water, and are typically depicted as large, wingless, serpentine creatures with clawed feet. Gould writes (1896:248),<ref>]. 1896. . W. H. Allen & Co.</ref> the Japanese dragon is "invariably figured as possessing three claws". A story about the '']'' ] tells that, while he was hunting in his own territory of ], he dreamt under a tree and had a dream in which a beautiful woman appeared to him and begged him to save her land from a giant serpent which was defiling it.{{sfn|Volker|1975|page=62}} Mitsunaka agreed to help and the maiden gave him a magnificent horse.{{sfn|Volker|1975|page=62}} When he woke up, the seahorse was standing before him.{{sfn|Volker|1975|page=62}} He rode it to the ] temple, where he prayed for eight days.{{sfn|Volker|1975|page=62}} Then he confronted the serpent and slew it with an arrow.{{sfn|Volker|1975|page=62}} | |||

| | The '''Chinese dragon''', is a ] ] creature that also appears in other ]n cultures, and is also sometimes called the ''Oriental (or Eastern) dragon''. Depicted as a long, snake-like creature with four claws, in contrast to the Western dragon which stands on two legs and which is usually portrayed as evil, it has long been a potent symbol of auspicious power in ] and ]. Lóng have a long, scaled serpentine form combined with the attributes of other animals; most (but not all) are wingless, and has four claws on each foot (five for the imperial emblem). They are rulers of the weather and ], and a symbol of power. They also carried their eggs which were thought to have been huge pearls in their hands. | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | '''Ryū''' | |||

| | Similar to ]s, with three claws instead of four. They are benevolent (with exceptions), associated with water, and may grant wishes; rare in Japanese mythology. | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | '''Bakonawa''' | |||

| | The Bakonawa appears as a gigantic serpent that lives in the sea. | |||

| It was believed that dragons could be appeased or ] with metal.{{sfn|Volker|1975|page=62}} ] is said to have hurled a famous sword into the sea at ] to appease the dragon-god of the sea{{sfn|Volker|1975|page=62}} and ] threw a metal mirror into the sea at Sumiyoshi for the same purpose.{{sfn|Volker|1975|page=62}} Japanese Buddhism has also adapted dragons by subjecting them to ];{{sfn|Volker|1975|page=62}} the Japanese Buddhist deities ] and ] are often shown sitting or standing on the back of a dragon.{{sfn|Volker|1975|page=62}} Several Japanese '']'' ("immortals") have taken dragons as their mounts.{{sfn|Volker|1975|page=62}} Bômô is said to have hurled his staff into a puddle of water, causing a dragon to come forth and let him ride it to heaven.{{sfn|Volker|1975|page=62}} The '']'' Handaka is said to have been able to conjure a dragon out of a bowl, which he is often shown playing with on ''kagamibuta''.{{sfn|Volker|1975|page=62}} The '']'' is a creature with the head of a dragon, a bushy tail, fishlike scales, and sometimes with fire emerging from its armpits.{{sfn|Volker|1975|page=62}} The ''fun'' has the head of a dragon, feathered wings, and the tail and claws of a bird.{{sfn|Volker|1975|page=62}} A white dragon was believed to reside in a pool in ]{{sfn|Volker|1975|page=63}} and, every fifty years, it would turn into a bird called the Ogonchô, which had a call like the "howling of a wild dog".{{sfn|Volker|1975|page=63}} This event was believed to herald terrible famine.{{sfn|Volker|1975|page=63}} In the Japanese village of Okumura, near ], during times of drought, the villagers would make a dragon effigy out of straw, ] leaves, and ] and parade it through the village to attract rainfall.{{sfn|Volker|1975|page=63}} | |||

| Ancient natives believed that the Bakonawa caused the moon or the sun to disappear during an eclipse. | |||

| ===Vietnam=== | |||

| It is said that during certain times of the year, the bakonawa arises from the ocean and proceeds to swallow the moon whole. To keep the Bakonawa from completely eating the moon, the natives would go out of their houses with pans and pots in hand and make a noise barrage in order to scare the Bakonawa into spitting out the moon back into the sky. | |||

| {{Main|Vietnamese dragon}} | |||

| ] period)]] | |||

| ], ]]] | |||

| The Vietnamese dragon ({{langx|vi|rồng}}) was a mythical creature that was often used as a deity symbol and was associated with royalty.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.vietnam-culture.com/articles-221-34/Tale-of-Vietnamese-Dragon.aspx|title=Tale of Vietnamese Dragon|date=4 February 2014|access-date=23 February 2021|archive-date=2 March 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210302081526/https://www.vietnam-culture.com/articles-221-34/Tale-of-Vietnamese-Dragon.aspx|url-status=live}}</ref>{{better source needed|date=November 2024}} Similar to other cultures, dragons in Vietnamese culture represent yang and godly beings associated with creation and life. In the creation myth of the ], they are descended from the dragon lord ] and the fairy ], who bore 100 eggs. When they separated, Lạc Long Quân brought 50 children to the sea while Âu Cơ brought the rest up the mountains. To this day, Vietnamese people often describe themselves as "Children of the dragon, grandchildren of the fairy" (''Con rồng cháu tiên'').<ref>{{cite book|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=aPQfqQB_7K0C&pg=PA91|title=Viêt Nam Exposé: French Scholarship on Twentieth-century Vietnamese Society|editor-last1=Bousquet|editor-first1= Gisèle|editor-last2=Brocheux|editor-first2=Pierre|pages=91|publisher=University of Michigan Press|year=2002|chapter=Rethinking the Status of Vietnamese Women in Folklore and Oral History|author=Nguyen Van Ky|isbn=0-472-06805-9 }}</ref> | |||

| ==South Asia== | |||

| In popular Filipino folk literature, the Bakonawa is said to have a sister in the form of a sea turtle. The sea turtle would visit a certain island in the Philippines in order to lay its eggs. However, locals soon discovered that every time the sea turtle went to shore, the water seemed to follow her, thus reducing the island's size. Worried that their island would eventually disappear, the locals killed the sea turtle. | |||

| ===India=== | |||

| ] depicted on a musical instrument from ], India]] | |||

| In the '']'', the oldest of the four ], ], the Vedic god of storms, battles ], a giant serpent who represents drought.{{sfn|West|2007|pages=255–257}} Indra kills Vṛtra using his '']'' (thunderbolt) and clears the path for rain,{{sfn|West|2007|pages=256–257}}{{sfn|Ogden|2013|page=16}} which is described in the form of cattle: "You won the cows, hero, you won the ],/You freed the seven streams to flow" (]).{{sfn|West|2007|page=257}} In another Rigvedic legend, the three-headed serpent ], the son of ], guards a wealth of cows and horses.{{sfn|West|2007|page=260}} Indra delivers Viśvarūpa to a god named ],{{sfn|West|2007|page=260}} who fights and kills him and sets his cattle free.{{sfn|West|2007|page=260}} Indra cuts off Viśvarūpa's heads and drives the cattle home for Trita.{{sfn|West|2007|page=260}} This same story is alluded to in the ],{{sfn|West|2007|page=260}} in which the hero ], the son of Āthbya, slays the three-headed dragon ] and takes his two beautiful wives as spoils.{{sfn|West|2007|page=260}} Thraētaona's name (meaning "third grandson of the waters") indicates that Aži Dahāka, like Vṛtra, was seen as a blocker of waters and cause of drought.{{sfn|West|2007|page=260}} | |||

| ===Bhutan=== | |||

| When the Bakonawa found out about this, it arose from the sea and ate the moon. The locals were so afraid that they prayed to Bathala to punish the Bakonawa. Bathala refused but instead, told them to bang some pots and pans in order to disturb the Bakonawa. The Bakonawa then regurgitated the moon and disappeared, never to be seen again. | |||

| The ] ({{langx|dz|འབྲུག་}}), also known as 'Thunder Dragon', is one of the ]. In the ] language, ] is known as ''Druk Yul'' "Land of Druk", and Bhutanese leaders are called ], "Thunder Dragon Kings". The druk was adopted as an emblem by the ], which originated in ] and later spread to Bhutan.<ref>{{cite book|last=Waddell|first=Laurence |author-link= Laurence Waddell |title=The Buddhism of Tibet Or Lamaism|year=1895|pages=199|publisher=Cosimo |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7PYwcfE_bLUC&q=Bhutan+thunder+dug&pg=PA199|isbn=9781602061378 }}</ref> | |||

| ==Europe== | |||

| The island where the sea turtle lays its eggs is said to exist until today. Some sources say that the island might just be one of the Turtle Islands. | |||

| ===Proto-Indo-European=== | |||

| |- | |||

| {{further|Chaoskampf|Sea serpent|Proto-Indo-European religion#Serpent-slaying myth{{!}}Serpent slayer|Serpents in the Bible}} | |||

| | rowspan="3" | ] | |||

| The tale of a hero slaying a giant serpent occurs in almost all ].{{sfn|Mallory|Adams|2006|pages=436–437}}{{sfn|West|2007|pages=255–263}} In most stories, the hero is some kind of ].{{sfn|West|2007|pages=255–263}} In nearly every iteration of the story, the serpent is either multi-headed or "multiple" in some other way.{{sfn|Mallory|Adams|2006|pages=436–437}} Furthermore, in nearly every story, the serpent is always somehow associated with water.{{sfn|West|2007|pages=255–263}} ] has proposed that a Proto-Indo-European dragon-slaying myth can be reconstructed as follows:{{sfn|Mallory|Adams|2006|page=437}}{{sfn|Anthony|2007|pages=134–135}} First, the sky gods give cattle to a man named ''*Tritos'' ("the third"), who is so named because he is the third man on earth,{{sfn|Mallory|Adams|2006|page=437}}{{sfn|Anthony|2007|pages=134–135}} but a three-headed serpent named *''{{PIE|Ng<sup>w</sup>hi}}'' steals them.{{sfn|Mallory|Adams|2006|page=437}}{{sfn|Anthony|2007|pages=134–135}} ''*Tritos'' pursues the serpent and is accompanied by ''*H<sub>a</sub>nér'', whose name means "man".{{sfn|Mallory|Adams|2006|page=437}}{{sfn|Anthony|2007|pages=134–135}} Together, the two heroes slay the serpent and rescue the cattle.{{sfn|Mallory|Adams|2006|page=437}}{{sfn|Anthony|2007|pages=134–135}} | |||

| | '''Yong''' | |||

| | A sky dragon, essentially the same as the Chinese lóng. Like the lóng, yong and the other Korean dragons are associated with water and weather. | |||

| |- | |||

| | '''yo''' | |||

| | A hornless ocean dragon, sometimes equated with a ]. | |||

| |- | |||

| | '''kyo''' | |||

| | A mountain dragon. | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | '''Rồng''' or '''Long''' | |||

| | These dragons' bodies curve lithely, in ] shape, with 12 sections, symbolising 12 months in the year. They are able to change the weather, and are responsible for crops. On the dragon's back are little, uninterrupted, regular fins. The head has a long mane, beard, prominent eyes, crest on nose, but no horns. The jaw is large and opened, with a long, thin tongue; they always keep a ''châu'' (gem/jewel) in their mouths (a symbol of humanity, nobility and knowledge). | |||

| |- | |||

| |] | |||

| | ''']''' | |||

| | Related to European Turkic and Slavic dragons | |||

| |- | |||

| |Indian Dragon | |||

| |'''Vyalee and Naga''' | |||

| |There is some debate as to whether or not Vyalee is considered a dragon. It is found in temples and is correlated with the goddess Parvati. Naga is the main dragon of Indian and Hindu mythology. Nagas are a race of magical serpents that live below water. Their king wears a golden crown atop his head. The Nagas are associated with Buddha and mainly with Lord Vishnu and his incarnations (Dasavataras). When Krishna was a child, he wrestled with a Naga that was obstructing a lake. | |||

| |- | |||

| | colspan="4" style="background-color: #ffa; text-align: center; font-weight: bold;" | ]s | |||

| |- | |||

| | Sardinian dragon | |||

| | ''']''' | |||

| | The dragon named "scultone" or "ascultone" was a legend in ], ] for many a millennium. It had the power to kill human beings with its gaze. It was a sort of ], lived in ] and was ]. | |||

| |- | |||

| | Scandinavian & Germanic dragons | |||

| | ''']''' | |||

| | Or the "Draco serpentalis" is a very large wingless serpent with two legs, the lindworm is really closer to a ] or to a ]. They were believed to eat cattle and symbolized pestilence, but seeing one was considered good luck. The dragon ], killed by the legendary hero ], was called an ormr ('worm') in Old Norse and was in effect a giant snake; it neither flew nor breathed fire. The dragon killed by the Old English hero ], on the other hand, did fly and breathe fire and was actually a European dragon. | |||

| |- | |||

| | Welsh dragon | |||

| | ''']''' | |||

| | The red dragon is the traditional symbol of Wales and appears on the Welsh national flag. | |||

| |- | |||

| | rowspan="3" | Hungarian dragons (Sárkányok) | |||

| | ''']''' | |||

| | A great snake living in a swamp, which regularly kills ]s or ]. A group of shepherds can easily kill them. | |||

| |- | |||

| | ''']''' | |||

| | A giant winged snake, which in fact a full-grown ''zomok''. It often serves as flying mount of the ''garabonciások'' (a kind of magician). The ''sárkánykígyó'' rules over storms and bad weather. | |||

| |- | |||

| | ''']''' | |||

| | A dragon in human form. Most of them are giants with multiple heads. Their strength is held in their heads. They become gradually weaker as they lose their heads. | |||

| |- | |||

| | ]s | |||

| | '''zmey''', '''zmiy''', '''змей''', or '''zmaj''' | |||

| | Similar to the conventional European dragon, but multi-headed. They breathe fire and/or leave fiery wakes as they fly. In Slavic and related tradition, dragons symbolize evil. Specific dragons are often given ] names (see Zilant, below), symbolizing the long-standing conflict between the Slavs and Turks. | |||

| |- | |||

| | Romanian dragons | |||

| | ''']''' | |||

| | Balaur are very similar to the Slavic ''zmey'': very large, with fins and multiple heads. | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ''']''' | |||

| |Chuvash dragons represent the pre-Islamic mythology of the same region. | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] dragons | |||

| | ''']''' | |||

| | In ] mythology the ]s are giant winged serpents, which live in caves where they guard treasures and kidnapped ]s. They can live for centuries and, when they grow really old, they use their wings to fly. Their breath is poisonous and they often kill cattle to eat. ] term ''Cuelebre'' comes from Latin ''colŭbra'', i.e. snake. | |||

| |- | |||

| | Tatar dragons | |||

| | ''']''' | |||

| | Really closer to a ], the Zilant is the symbol of ]. ''Zilant'' itself is a Russian rendering of Tatar ''yılan'', i.e. snake. | |||

| |- | |||

| | Turkish dragons | |||

| | '''] or ]''' | |||

| | This creature is strikingly different from its fire breathing, flying European counterpart. The Turkish Dragon secretes flames from its tail, and there is no mention in any legends of its having wings, or even legs. In fact, most Turkish (and later, Islamic) sources describe dragons as gigantic snakes. The blood of the Turkish Dragon has its medical properties, becoming a panacea if drawn from the head and a lethal poison if drawn from the tail. | |||

| ===Ancient Greece=== | |||

| |- | |||

| {{Main|Dragons in Greek mythology}} | |||

| | rowspan="2" | Basque dragons | |||

| ] vase painting depicting ] slaying the ], {{circa}} 375–340 BC]] | |||

| | ''']''' | |||

| | Basque for "dragon". One legend has ] descending from Heaven to kill it, but only when ] agreed to accompany him, so fearful it was. | |||

| |- | |||

| | ''']''' | |||

| | The male god of ], also called '''Maju''', was often associated to a serpent or snake, though he can adopt other forms. | |||

| |- | |||

| | colspan="4" style="background-color: #ffa; text-align: center; font-weight: bold;" | American dragons | |||

| |- | |||

| | Meso-American dragon | |||

| | ''']''' | |||

| | Feathered serpent deity responsible for giving knowledge to mankind, and sometimes also a symbol of death and resurrection. | |||

| |- | |||

| | Inca dragon | |||

| | Amaru | |||

| | A dragon (sometimes called a snake) on the ] culture. The last Inca emperor ]'s name means "Lord Dragon" | |||

| |- | |||

| | Brazilian dragon | |||

| | ''']''' | |||

| | A dragon-like animal (sometimes like a snake) of the ] cultures. | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | Caicaivilu and Tentenvilu | |||

| | Snake-type dragons, ] was the sea god and ] was the earth god, both from the ]an island ]. | |||

| |- | |||

| |colspan="4" style="background-color: #ffa; text-align: center; font-weight: bold;" | African dragons | |||

| |- | |||

| |North African dragon | |||

| |''']''' | |||

| | Possibly originating in northern Africa (and later moving to Greece), this was a two-headed dragon (one at the front, and one on the end of its tail). The front head would hold the tail (or neck as the case may be) in its mouth, creating a circle that allowed it to roll. | |||

| |- | |||

| | Egyptian dragon | |||

| | ''']''' | |||

| | The ancient Egyptians believed that the deity Ra battled this cobra-like dragon whenever he (as the sun) sank below the horizon. Apep was a symbol of evil and chaos. | |||

| |- | |||

| | colspan="4" style="background-color: #ffa; text-align: center; font-weight: bold;" | Dragon-like creatures | |||

| |- | |||

| | colspan="2" | ''']''' | |||

| | A basilisk is hatched by a cockerel from a serpent's egg. It is a lizard-like or snake-like creature that can supposedly kill by its gaze, its voice, or by touching its victim. | |||

| |- | |||

| | colspan="2" | ''']''' | |||

| | In ] mythology, a leviathan was a large creature with fierce teeth. Contemporary translations identify the leviathan with the crocodile, but maintaining a strict Biblical perspective the leviathan can breathe fire (Job 41:18-21), can fly (Job 41:5), it cannot be pierced with spears or harpoons (Job 41:7), its scales are so closely fit that there is no room between them (Job 41:15-16), it walks upright (Job 41:12), its mouth is powerful and contains many formidable teeth (Job 41:14), its underbelly has sharp scales that could cut a person (Job 41:30), and, over all, it is a terrifying creature. Over time, the term came to mean any large sea monster; in ], "leviathan" simply means ]. A ] is also closely related to the dragon, though it is more snakelike and lives in the water. | |||

| |- | |||

| | colspan="2" | ''']''' | |||

| | Much more similar to a dragon than the other creatures listed here, a wyvern is a winged serpent with either two or no legs. The term wyvern is used in ] to distinguish two-legged from four-legged dragons. Also sometimes noted as the largest species of dragon. | |||

| |- | |||

| | colspan="2" | ''']''' | |||

| | Derived from the Slavic dragon, zmeu are ''humanoid'' figures that can fly and breathe fire. | |||

| |- | |||

| | colspan="2" | ''']''' | |||

| | A bird-like reptile sometimes confused with a basilisk. In Gerald Durrell's book "The Talking Parcel", they attempt genocide against dragons by stealing the last dragon eggs | |||

| |- | |||

| | colspan="2" | ''']''' | |||

| | A Central-American or Mexican creature with both scales and feathers worshipped by the ]s and ]s. | |||

| |} | |||

| The ancient Greek word usually translated as "dragon" (δράκων ''drákōn'', ] δράκοντοϛ ''drákontos'') could also mean "snake",<ref>Chad Hartsock, ''Sight and Blindness in Luke-Acts: The Use of Physical Features in Characterization'', Brill, Leiden-Boston, 2008, .</ref>{{sfn|Ogden|2013|pages=2–4}} but it usually refers to a kind of giant serpent that either possesses supernatural characteristics or is otherwise controlled by some supernatural power.{{sfn|Ogden|2013|pages=2–3}} The first mention of a "dragon" in ] occurs in the '']'', in which ] is described as having a blue dragon motif on his sword belt and an emblem of a three-headed dragon on his breast plate.<ref>Drury, Nevill, ''The Dictionary of the Esoteric'', Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 2003 {{ISBN|81-208-1989-6}}, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161227000311/https://books.google.com/books?id=k-tVr09oq3IC&pg=PA79&lpg=PA79&dq=earliest+mention+of+dragon&source=web&ots=fxq_n3SLTa&sig=zKfmIXx1BT3nQAZq3I0vkx9akhM&hl=en |date=27 December 2016 }}.</ref> In lines 820–880 of the '']'', a Greek poem written in the seventh century BC by the ]n poet ], the Greek god ] battles the monster ], who has one hundred serpent heads that breathe fire and make many frightening animal noises.{{sfn|West|2007|page=257}} Zeus scorches all of Typhon's heads with his lightning bolts and then hurls Typhon into ]. In other Greek sources, Typhon is often depicted as a winged, fire-breathing serpent-like dragon.{{sfn|West|2007|page=258}} In the '']'', the god ] uses his ] to slay the serpent ], who has been causing death and pestilence in the area around ].{{sfn|Ogden|2013|pages=47–48}}{{sfn|West|2007|page=258}}<ref>{{Cite book |last=Hesiod |title=Hesiod and the Homeric Hymns |publisher=University of Chicago Press |year=1914 |publication-date=2005 |pages=122–134 |translator-last=Hine |translator-first=Daryl |chapter=To Pythian Apollo}}</ref> Apollo then sets up his shrine there.{{sfn|West|2007|page=258}} | |||

| ==Notable dragons== | |||

| ===In myth=== | |||

| {{main|List of dragons in mythology and folklore}} | |||

| * ] was a three-headed demon often characterized as dragon-like in ]n ] mythology. | |||

| * Similarly, ] myth describes a seven-headed ] named ]. | |||

| *The ] of ] is a water serpent with multiple heads with mystic powers. When one was chopped off, two would regrow in its place. This creature was vanquished by ] and his cousin. | |||

| * ] was a ] dragon who was supposed to have terrorized the hills around ] in the ]. | |||

| * ] is now the symbol of Wales (see flag, above), originally appearing as the red dragon from the ] story ''Lludd and Llevelys''. | |||

| * ], a dragon in ], was said to live in the darkest part of the ], awaiting ]. At that time he would be released to wreak destruction on the world. | |||

| * ], the ] serpent slain by ] in ] | |||

| The Roman poet ] in his poem ], lines 163–201 , describing a shepherd having a fight with a big ], calls it "]" and also "]", showing that in his time the two words were probably interchangeable. | |||

| ===In literature and fiction=== | |||

| {{main|List of fictional dragons}} | |||

| The Old English epic '']'' ends with the hero battling a dragon. | |||

| ] dragon disgorges the hero ]{{sfn|Ogden|2013|page=59}}{{sfn|Deacy|2008|page=62}}]] | |||

| Dragons remain fixtures in fantasy books, though portrayals of their nature differ. For example, ], from '']'' by ], who is a classic, European-type dragon; deeply magical, he hoards treasure and burns innocent towns. Contrary to most old folklore and literature J. R. R. Tolkien's dragons are very intelligent and can cast spells over mortals. | |||

| Hesiod also mentions that the hero ] slew the ], a multiple-headed serpent which dwelt in the swamps of ].{{sfn|Ogden|2013|pages=28–29}} The name "Hydra" means "water snake" in Greek.{{sfn|West|2007|page=258}}{{sfn|Ogden|2013|page=28}} According to the '']'' of Pseudo-Apollodorus, the slaying of the Hydra was the second of the ].{{sfn|Ogden|2013|pages=26–27}}{{sfn|West|2007|page=258}} Accounts disagree on which weapon Heracles used to slay the Hydra,{{sfn|West|2007|page=258}} but, by the end of the sixth century BC, it was agreed that the clubbed or severed heads needed to be ] to prevent them from growing back.{{sfn|Ogden|2013|page=26}}{{sfn|West|2007|page=258}} Heracles was aided in this task by his nephew ].{{sfn|Ogden|2013|page=26}} During the battle, a giant crab crawled out of the marsh and pinched Heracles's foot,{{sfn|Ogden|2013|pages=26–27}} but he crushed it under his heel.{{sfn|Ogden|2013|page=27}} ] placed the crab in the sky as the constellation ].{{sfn|Ogden|2013|page=27}} One of the Hydra's heads was immortal, so Heracles buried it under a heavy rock after cutting it off.{{sfn|West|2007|page=258}}{{sfn|Ogden|2013|page=27}} For his Eleventh Labor, Heracles must procure a ] from the tree in the ], which is guarded by an enormous serpent that never sleeps,{{sfn|Ogden|2013|page=33}} which Pseudo-Apollodorus calls "]".{{sfn|Ogden|2013|pages=33–34}} In earlier depictions, Ladon is often shown with many heads.{{sfn|Ogden|2013|page=37}} In Pseudo-Apollodorus's account, Ladon is immortal,{{sfn|Ogden|2013|page=37}} but ] and ] both describe Heracles as killing him, although neither of them specifies how.{{sfn|Ogden|2013|page=37}} Some suggest that the golden apple was not claimed through battle with Ladon at all but through Heracles charming the Hesperides.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Hesperia {{!}} American School of Classical Studies at Athens |url=https://www.ascsa.edu.gr/publications/hesperia/article/33/1/76-82 |access-date=2022-12-06 |website=ascsa.edu.gr |archive-date=19 February 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240219205908/https://www.ascsa.edu.gr/publications/hesperia/article/33/1/76-82 |url-status=live }}</ref> The mythographer ] is the first to state that Heracles slew him using his famous club.{{sfn|Ogden|2013|page=37}} ], in his epic poem, the '']'', describes Ladon as having been shot full of poisoned arrows dipped in the blood of the Hydra.{{sfn|Ogden|2013|page=38}} | |||