| Revision as of 08:04, 2 July 2007 editCarcharoth (talk | contribs)Administrators73,578 edits add friction to list of causes← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 16:15, 13 December 2024 edit undoFanfanboy (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Rollbackers3,488 editsm Reverted edits by Bertha.the.beast19 (talk) (HG) (3.4.13)Tags: Huggle Rollback | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Injury to flesh or skin, often caused by excessive heat}} | |||

| {{unreferenced|date=November 2006}} | |||

| {{About|the injury||Burn (disambiguation)}} | |||

| :''This article describes a type of injury. For other meanings of the word, see ].'' | |||

| {{Good article}} | |||

| In ], a '''burn''' is a type of injury to the ] caused by ], ], ], ], ] or ] (e.g. a '']''). | |||

| {{Cs1 config|name-list-style=vanc}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=November 2017}} | |||

| {{Infobox medical condition (new) | |||

| | name = Burn | |||

| | image = Hand2ndburn.jpg | |||

| | caption = Second-degree burn of the hand | |||

| | field = ], ], ]<ref>{{cite web |title=Burns - British Association of Plastic Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons|url=http://www.bapras.org.uk/public/patient-information/surgery-guides/burns |website=BAPRAS}}</ref> | |||

| | symptoms = '''First degree''': Red without ]<ref name=Tint2010/><br/>'''Second degree''': Blisters and pain<ref name=Tint2010/><br/>'''Third degree''': Area stiff and not painful<ref name=Tint2010/> | |||

| <br />'''Fourth degree''': Bone and tendon loss<ref name="Singer 666–671">{{cite journal|last=Singer|first=Adam|title=Management of local burn wounds in the ED|journal=The American Journal of Emergency Medicine|date=June 2007|volume=25|issue=6|pages=666–671|doi=10.1016/j.ajem.2006.12.008|pmid=17606093|url=https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2006.12.008}}</ref> | |||

| | complications = ]<ref name=TBCChp3/> | |||

| Metabolic: protein and lean muscle loss | |||

| Scarring: keloid/hypertrophic | |||

| Cardiovascular complications | |||

| ==Classification==<!-- This section is linked from ] --> | |||

| ] | |||

| * '''First-degree burns''' are usually limited to redness (]), a white plaque and minor ] at the site of injury. These burns usually extend only into the ]. | |||

| * '''Second-degree burns''' additionally fill with clear fluid, have superficial ]ing of the skin, and can involve more or less pain depending on the level of ] involvement. Second-degree burns involve the superficial (papillary) ] and may also involve the deep (reticular) dermis layer. | |||

| <gallery> | |||

| Image:Burn 2nd degree 1.jpg|Evolution of a 2nd degree burn — One hour | |||

| Image:Burn 2nd degree 2.jpg|Evolution of a 2nd degree burn — One day | |||

| Image:Burn 2nd degree 3.jpg|Evolution of a 2nd degree burn — two days, the blister is appearing | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| * '''Third-degree burns''' additionally have ] of the skin, and produce hard, leather-like ]s. An eschar is a scab that has separated from the unaffected part of the body. Frequently, there is also purple fluid. These types of burns are often painless because nerve endings have been destroyed in the involved areas. | |||

| Burns that injure the tissues underlying the skin, such as the muscles or bones, are sometimes categorized as '''fourth-degree burns'''. These burns are broken down into three additional degrees: fourth-degree burns result in the skin being irretrievably lost, fifth-degree burns result in muscle being irretrievably lost, and sixth-degree burns result in bone being charred. | |||

| Neuropathy | |||

| A newer classification of "Superficial Thickness", "Partial Thickness" (which is divided into superficial and deep categories) and "Full Thickness" relates more precisely to the epidermis, dermis and subcutaneous layers of skin and is used to guide treatment and predict outcome. | |||

| Heterotrophic ossification | |||

| '''''Table 1.'' A description of the traditional and current classifications of burns.''' | |||

| | onset = | |||

| {|class="wikitable" | |||

| | duration = Days to weeks<ref name=Tint2010/> | |||

| |{{bgcolor-gold}}|'''Nomenclature'''||{{bgcolor-gold}}|'''Traditional nomenclature'''||{{bgcolor-gold}}|'''Depth'''||{{bgcolor-gold}}|'''Clinical findings''' | |||

| | types = First degree, second degree, third degree,<ref name=Tint2010/> fourth degree<ref name="Singer 666–671"/> | |||

| | causes = ], ], ], ], ], ]<ref name=TBCChp4/> | |||

| | risks = Open cooking fires, unsafe ]s, smoking, ], dangerous work environment<ref name=WHO2016/> | |||

| | diagnosis = | |||

| | differential = | |||

| | prevention = | |||

| | treatment = Depends on the severity<ref name=Tint2010/> | |||

| '''''Medical Treatment''''' | |||

| Antiseptics | |||

| Analgesics | |||

| Dressings | |||

| Wound management | |||

| Respiratory management | |||

| Skin grafts: cloned skin, autografts and adjacent tissue grafts | |||

| '''''Rehabilitation''''' | |||

| Positioning and splinting | |||

| Active and passive exercise | |||

| Resistive and conditioning exercise | |||

| Aerobic exercise | |||

| Respiratory management | |||

| Ambulation | |||

| ''Scar management:'' pressure garment, dressing, silicone gel | |||

| | medication = Pain medication, ]s, ]<ref name=Tint2010/> | |||

| | prognosis = | |||

| | frequency = 67 million (2015)<ref name=GBD2015Pre/> | |||

| | deaths = 176,000 (2015)<ref name=GBD2015De/> | |||

| | alt = | |||

| }} | |||

| <!-- Definition and cause --> | |||

| <!-- STOP ADDING RANDOM DEFINITIONS WITHOUT A RELIABLE SOURCE, PER WP:CITE AND WP:RS --> | |||

| A '''burn''' is an ] to ], or other tissues, caused by ], ], ], ], ], or ionizing ] (such as ], caused by ]).<ref name="TBCChp4">{{cite book|editor=Herndon D|title=Total burn care|publisher=Saunders|location=Edinburgh|isbn=978-1-4377-2786-9|page=46|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nrG7ZY4QwQAC&pg=PA47-IA4|edition=4th|chapter=Chapter 4: Prevention of Burn Injuries|year=2012}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Moore |first=Keith |title=Clinically Oriented Anatomy |publisher=Lippincott Williams & Wilkins |year=2014 |isbn=9781451119459 |edition=7th |pages=45 |language=English}}</ref> Most burns are due to heat from hot liquids (called ]), solids, or fire.<ref name="WHO2014">{{cite web|title=Burns Fact sheet N°365|url=https://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs365/en/|website=WHO|access-date=3 March 2016|date=April 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151110140702/http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs365/en/|archive-date=2015-11-10|url-status=dead}}</ref> Burns occur mainly in the home or the workplace. In the home, risks are associated with domestic kitchens, including stoves, flames, and hot liquids.<ref name=WHO2016/> In the workplace, risks are associated with fire and chemical and ].<ref name=WHO2016/> ] and smoking are other risk factors.<ref name=WHO2016/> Burns can also occur as a result of ] or ] between people (assault).<ref name=WHO2016/> | |||

| <!-- Signs and symptoms --> | |||

| Burns that affect only the superficial skin layers are known as superficial or '''first-degree burns'''.<ref name=Tint2010/><ref name=EMP2009/> They appear red without blisters, and pain typically lasts around three days.<ref name=Tint2010/><ref name=EMP2009>{{cite journal|last=Granger|first=Joyce |title=An Evidence-Based Approach to Pediatric Burns|journal=Pediatric Emergency Medicine Practice|date=Jan 2009|volume=6|issue=1|url=http://www.ebmedicine.net/topics.php?paction=showTopic&topic_id=186|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131017123658/http://www.ebmedicine.net/topics.php?paction=showTopic&topic_id=186|archive-date=17 October 2013}}</ref> When the injury extends into some of the underlying skin layer, it is a partial-thickness or '''second-degree burn'''.<ref name=Tint2010/> Blisters are frequently present and they are often very painful.<ref name=Tint2010/> Healing can require up to eight weeks and ] may occur.<ref name=Tint2010/> In a full-thickness or '''third-degree burn''', the injury extends to all layers of the skin.<ref name=Tint2010/> Often there is no pain and the burnt area is stiff.<ref name=Tint2010/> Healing typically does not occur on its own.<ref name=Tint2010/> A '''fourth-degree burn''' additionally involves injury to deeper tissues, such as ], ]s, or ].<ref name=Tint2010>{{cite book |author=Tintinalli, Judith E. |title=Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide (Emergency Medicine (Tintinalli)) |publisher=McGraw-Hill Companies |location=New York |year=2010 |pages=1374–1386|isbn=978-0-07-148480-0}}</ref> The burn is often black and frequently leads to loss of the burned part.<ref name=Tint2010/><ref>{{cite book|last1=Ferri|first1=Fred F.|title=Ferri's netter patient advisor|date=2012|publisher=Saunders|location=Philadelphia, PA|isbn=978-1-4557-2826-8|page=235|edition=2nd|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=li1VCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA235|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161221093201/https://books.google.ca/books?id=li1VCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA235|archive-date=21 December 2016}}</ref> | |||

| <!--Prevention and management --> | |||

| Burns are generally preventable.<ref name=WHO2016>{{cite web|title=Burns|url=https://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs365/en/|website=World Health Organization|access-date=1 August 2017|date=September 2016|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170721132816/http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs365/en/|archive-date=21 July 2017}}</ref> Treatment depends on the severity of the burn.<ref name=Tint2010/> Superficial burns may be managed with little more than ], while major burns may require prolonged treatment in specialized ]s.<ref name=Tint2010/> Cooling with tap water may help pain and decrease damage; however, prolonged cooling may result in ].<ref name=Tint2010/><ref name=EMP2009/> Partial-thickness burns may require cleaning with soap and water, followed by ].<ref name=Tint2010/> It is not clear how to manage blisters, but it is probably reasonable to leave them intact if small and drain them if large.<ref name=Tint2010/> Full-thickness burns usually require surgical treatments, such as ].<ref name=Tint2010/> Extensive burns often require large amounts of ], due to ] fluid leakage and ].<ref name=EMP2009/> The most common complications of burns involve ].<ref name=TBCChp3>{{cite book|editor=Herndon D|title=Total burn care|publisher=Saunders|location=Edinburgh|isbn=978-1-4377-2786-9|page=23|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nrG7ZY4QwQAC&pg=PA15|edition=4th|chapter=Chapter 3: Epidemiological, Demographic, and Outcome Characteristics of Burn Injury|year=2012}}</ref> ] should be given if not up to date.<ref name=Tint2010/> | |||

| <!-- Epidemiology and prognosis --> | |||

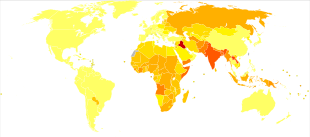

| In 2015, fire and heat resulted in 67 million injuries.<ref name=GBD2015Pre>{{cite journal | vauthors = Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Brown A, etal | title = Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 | journal = The Lancet | volume = 388 | issue = 10053 | pages = 1545–1602 | date = October 2016 | pmid = 27733282 | pmc = 5055577 | doi = 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6 }}</ref> This resulted in about 2.9 million hospitalizations and 176,000 deaths.<ref name=GBD2015De>{{cite journal | vauthors = Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber R, Bhutta Z, Carter A, etal | title = Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 | journal = The Lancet | volume = 388 | issue = 10053 | pages = 1459–1544 | date = October 2016 | pmid = 27733281 | pmc = 5388903 | doi = 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1 }}</ref><ref name=GBD2016>{{cite journal | vauthors = Haagsma JA, Graetz N, Bolliger I, Naghavi M, Higashi H, Mullany EC, Abera SF, Abraham JP, Adofo K, Alsharif U, Ameh EA, Ammar W, Antonio CA, Barrero LH, Bekele T, Bose D, Brazinova A, Catalá-López F, Dandona L, Dandona R, Dargan PI, De Leo D, Degenhardt L, Derrett S, Dharmaratne SD, Driscoll TR, Duan L, Petrovich Ermakov S, Farzadfar F, Feigin VL, Franklin RC, Gabbe B, Gosselin RA, Hafezi-Nejad N, Hamadeh RR, Hijar M, Hu G, Jayaraman SP, Jiang G, Khader YS, Khan EA, Krishnaswami S, Kulkarni C, Lecky FE, Leung R, Lunevicius R, Lyons RA, Majdan M, Mason-Jones AJ, Matzopoulos R, Meaney PA, Mekonnen W, Miller TR, Mock CN, Norman RE, Orozco R, Polinder S, Pourmalek F, Rahimi-Movaghar V, Refaat A, Rojas-Rueda D, Roy N, Schwebel DC, Shaheen A, Shahraz S, Skirbekk V, Søreide K, Soshnikov S, Stein DJ, Sykes BL, Tabb KM, Temesgen AM, Tenkorang EY, Theadom AM, Tran BX, Vasankari TJ, Vavilala MS, Vlassov VV, Woldeyohannes SM, Yip P, Yonemoto N, Younis MZ, Yu C, Murray CJ, Vos T | display-authors = 6 | title = The global burden of injury: incidence, mortality, disability-adjusted life years and time trends from the Global Burden of Disease study 2013 | journal = Injury Prevention | volume = 22 | issue = 1 | pages = 3–18 | date = February 2016 | pmid = 26635210 | pmc = 4752630 | doi = 10.1136/injuryprev-2015-041616 }}</ref> Among women in much of the world, burns are most commonly related to the use of open cooking fires or unsafe ]s.<ref name=WHO2016/><!-- Quote=The higher risk for females is associated with open fire cooking, or inherently unsafe cookstoves, which can ignite loose clothing. --> Among men, they are more likely a result of unsafe workplace conditions.<ref name=WHO2016/> Most deaths due to burns occur in the ], particularly in ].<ref name=WHO2016/> While large burns can be fatal, treatments developed since 1960 have improved outcomes, especially in children and young adults.<ref name=TBCChp1>{{cite book|editor=Herndon D|title=Total burn care|publisher=Saunders|location=Edinburgh|isbn=978-1-4377-2786-9|page=1|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nrG7ZY4QwQAC|edition=4th|chapter=Chapter 1: A Brief History of Acute Burn Care Management|year=2012}}{{Dead link|date=August 2023 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> In the United States, approximately 96% of those admitted to a ] survive their injuries.<ref name=ABA2012>{{cite web|title=Burn Incidence and Treatment in the United States: 2012 Fact Sheet|url=http://www.ameriburn.org/resources_factsheet.php|work=American Burn Association|access-date=20 April 2013|year=2012|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130221151012/http://www.ameriburn.org/resources_factsheet.php|archive-date=21 February 2013}}</ref> The long-term outcome is related to the size of burn and the age of the person affected.<ref name=Tint2010/> | |||

| {{TOC limit}} | |||

| ==History== | |||

| ] | |||

| Cave paintings from more than 3,500 years ago document burns and their management.<ref name=TBCChp1/> The earliest Egyptian records on treating burns describes dressings prepared with milk from mothers of baby boys,<ref name="Pećanac-">{{cite journal | vauthors = Pećanac M, Janjić Z, Komarcević A, Pajić M, Dobanovacki D, Misković SS | title = Burns treatment in ancient times | journal = Medicinski Pregled | volume = 66 | issue = 5–6 | pages = 263–7 | year = 2013 | pmid = 23888738 | doi = 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00603-5 }}</ref> and the 1500 BCE ] describes treatments using honey and the ] of resin.<ref name=TBCChp1/> Many other treatments have been used over the ages, including the use of tea leaves by the Chinese documented to 600 BCE, pig fat and vinegar by ] documented to 400 BCE, and wine and ] by ] documented to the 1st century CE.<ref name=TBCChp1/> French barber-surgeon ] was the first to describe different degrees of burns in the 1500s.<ref name=David2012>{{cite book|last=Song|first=David|title=Plastic surgery|publisher=Saunders|location=Edinburgh|isbn=978-1-4557-1055-3|page=393.e1|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qMDwwF8vsSEC&pg=PA393-IA3|edition=3rd|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160502014656/https://books.google.com/books?id=qMDwwF8vsSEC&pg=PA393-IA3|archive-date=2 May 2016|date=5 September 2012}}</ref> ] expanded these degrees into six different severities in 1832.<ref name=TBCChp1/><ref>{{cite book|last=Wylock|first=Paul|title=The life and times of Guillaume Dupuytren, 1777–1835|year=2010|publisher=Brussels University Press|location=Brussels|isbn=978-90-5487-572-7|page=60|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OWrznUOS1agC&pg=PA60|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160516062656/https://books.google.com/books?id=OWrznUOS1agC&pg=PA60|archive-date=16 May 2016}}</ref> | |||

| The first hospital to treat burns opened in 1843 in London, England, and the development of modern burn care began in the late 1800s and early 1900s.<ref name=TBCChp1/><ref name=David2012/> During World War I, ] and ] developed standards for the cleaning and disinfecting of burns and wounds using ] solutions, which significantly reduced mortality.<ref name=TBCChp1/> In the 1940s, the importance of early excision and skin grafting was acknowledged, and around the same time, fluid resuscitation and formulas to guide it were developed.<ref name=TBCChp1/> In the 1970s, researchers demonstrated the significance of the hypermetabolic state that follows large burns.<ref name=TBCChp1/> | |||

| The "Evans formula", described in 1952, was the first burn ] formula based on body weight and surface area (BSA) damaged. The first 24 hours of treatment entails 1ml/kg/% BSA of crystalloids plus 1 ml/kg/% BSA colloids plus 2000ml glucose in water, and in the next 24 hours, crystalloids at 0.5 ml/kg/% BSA, colloids at 0.5 ml/kg/% BSA, and the same amount of glucose in water.<ref>{{cite journal | title=The Evans Formula Revisited| journal=Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery| volume=12| issue=6| pages=453–8| date=June 1972| last1=Hutcher| first1=Neil| last2=Haynes| first2=B. W. Jr| doi=10.1097/00005373-197206000-00001| pmid=5033490}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Regan |first1=Abby |last2=Hotwagner |first2=David T. |title=Burn Fluid Management |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534227/#:~:text=The%20Evans%20formula%20was%20developed,2000%20ml%20glucose%20in%20water. |website=StatPearls |publisher=StatPearls Publishing |access-date=31 October 2023 |date=2023|pmid=30480960 }}</ref> | |||

| ==Signs and symptoms== | |||

| The characteristics of a burn depend upon its depth. Superficial burns cause pain lasting two or three days, followed by peeling of the skin over the next few days.<ref name=EMP2009/><ref name=TBCChp10/> Individuals with more severe burns may indicate discomfort or complain of feeling pressure rather than pain. Full-thickness burns may be entirely insensitive to light touch or puncture.<ref name=TBCChp10/> While superficial burns are typically red in color, severe burns may be pink, white or black.<ref name=TBCChp10/> Burns around the mouth or singed hair inside the nose may indicate that burns to the airways have occurred, but these findings are not definitive.<ref name=Schw2010/> More worrisome signs include: ], hoarseness, and ] or ].<ref name=Schw2010/> ] is common during the healing process, occurring in up to 90% of adults and nearly all children.<ref name=Itchy2009>{{cite journal | vauthors = Goutos I, Dziewulski P, Richardson PM | title = Pruritus in burns: review article | journal = Journal of Burn Care & Research | volume = 30 | issue = 2 | pages = 221–8 | date = Mar–Apr 2009 | pmid = 19165110 | doi = 10.1097/BCR.0b013e318198a2fa | s2cid = 3679902 }}</ref> Numbness or tingling may persist for a prolonged period of time after an electrical injury.<ref name=RosenChp140/> Burns may also produce emotional and psychological distress.<ref name=Epi2011/> | |||

| {{anchor|By_depth}} | |||

| {| class="wikitable mw-collapsible" | |||

| |- | |||

| ! Type<ref name=Tint2010/> !! Layers involved !! Appearance !! Texture !! Sensation !! Healing time !! Prognosis and complications !! Example | |||

| |- | |||

| | Superficial (first-degree)|| ]<ref name=EMP2009/> ||] without blisters<ref name=Tint2010/>|| Dry || ]ful<ref name=Tint2010/>|| 5–10 days<ref name=Tint2010/><ref name=AFP2012/> || Heals well.<ref name=Tint2010/> || ] | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | Superficial partial thickness (second-degree) || Extends into superficial (papillary) ]<ref name=Tint2010/> || Redness with clear ].<ref name=Tint2010/> ] with pressure.<ref name=Tint2010/> || Moist<ref name=Tint2010/> || Very painful<ref name=Tint2010/> || 2–3 weeks<ref name=Tint2010/><ref name=TBCChp10/> || Local infection (]) but no scarring typically<ref name=TBCChp10>{{cite book |editor=Herndon D |title=Total burn care |publisher=Saunders| location=Edinburgh |isbn=978-1-4377-2786-9 |page=127 |edition=4th|chapter=Chapter 10: Evaluation of the burn wound: management decisions|year=2012 }}</ref>|| | |||

| |Superficial thickness||First-degree||Epidermis involvement||], minor pain, lack of blisters | |||

| ] | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | Deep partial thickness (second-degree) || Extends into deep (reticular) dermis<ref name=Tint2010/> || ] or ]. Less blanching. May be ]ing.<ref name=Tint2010/> || Fairly dry<ref name=TBCChp10/> || Pressure and discomfort<ref name=TBCChp10/> || 3–8 weeks<ref name=Tint2010/>|| Scarring, ] (may require excision and ])<ref name=TBCChp10/> || ] | |||

| |Partial thickness — superficial||Second-degree||Superficial (papillary) ]||Blisters, clear fluid, and pain | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | Full thickness (third-degree) || Extends through entire dermis<ref name=Tint2010/> || Stiff and ]/].<ref name=Tint2010/> No blanching.<ref name=TBCChp10/> || Leathery<ref name=Tint2010/> || Painless<ref name=Tint2010/> || Prolonged (months) and unfinished/incomplete<ref name=Tint2010/> || Scarring, contractures, amputation (early excision recommended)<ref name=TBCChp10/> || ] | |||

| |Partial thickness — deep||Second-degree||Deep (reticular) dermis||Whiter appearance, with decreased pain. Difficult to distinguish from full thickness | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | Fourth-degree|| Extends through entire skin, and into underlying fat, muscle and bone<ref name=Tint2010/> || ]; charred with ] || Dry || Painless || Does not ]; Requires excision<ref name=Tint2010/> || ], significant functional impairment and, in some cases, death.<ref name=Tint2010/> | |||

| |Full thickness||Third- or fourth-degree||Dermis and underlying tissue and possibly ], ], or ]||Hard, leather-like eschar, purple fluid, no sensation (insensate) | |||

| | ] | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| ==Cause== | |||

| Serious burns, especially if they cover large areas of the body, can cause ]; any hint of burn injury to the ]s (e.g. through smoke inhalation) is a ]. | |||

| Burns are caused by a variety of external sources classified as thermal (heat-related), chemical, electrical, and radiation.<ref>{{cite book| first1 = Caroline Bunker | last1 = Rosdahl | first2 = Mary T | last2 = Kowalski |title=Textbook of basic nursing|year=2008|publisher=Lippincott Williams & Wilkins|location=Philadelphia|isbn=978-0-7817-6521-3|page=1109|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=odY9mXicPlYC&pg=PA1109|edition=9th|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160512052038/https://books.google.com/books?id=odY9mXicPlYC&pg=PA1109|archive-date=12 May 2016}}</ref> In the United States, the most common causes of burns are: fire or flame (44%), scalds (33%), hot objects (9%), electricity (4%), and chemicals (3%).<ref name=ABA2012pgi>National Burn Repository Pg. i</ref> Most (69%) burn injuries occur at home or at work (9%),<ref name=ABA2012/> and most are accidental, with 2% due to assault by another, and 1–2% resulting from a ] attempt.<ref name=Epi2011/> These sources can cause inhalation injury to the airway and/or lungs, occurring in about 6%.<ref name=TBCChp3/> | |||

| Burn injuries occur more commonly among the poor.<ref name=Epi2011/> Smoking and alcoholism are other risk factors.<ref name=WHO2014/> Fire-related burns are generally more common in colder climates.<ref name=Epi2011/> Specific risk factors in the developing world include ]<ref name=TBCChp4/> as well as ] in children and chronic diseases in adults.<ref name=LMIC2006/> | |||

| Chemical burns are usually caused by ], such as ] (]), ], and more serious compounds (such as ]). Most chemicals (but not all) that can cause moderate to severe chemical burns are strong ]s or ]. ], as an oxidizer, is possibly one of the worst burn-causing chemicals. ] can eat down to the bone and its burns are often not immediately evident. Most chemicals that can cause moderate to severe chemical burns are called ]. | |||

| ===Thermal=== | |||

| Electrical burns are generally symptoms of ], being struck by ], being ] without conductive gel, etc. The internal injuries sustained may be disproportionate to the size of the "burns" seen - as these are only the entry and exit wounds of the electrical current. | |||

| {{main|Thermal burn}} | |||

| {{Image frame | |||

| |width=520<!-- Must be kept at this size at this point (December 2017) --> | |||

| |content ={{Global Heat Maps by Year| title=| table=Fire Death Rate.tab| column=number| columnName=Deaths per 100,000| year=2017|%=}} | |||

| |caption=Rate of deaths (per 100,000) due to fire between 1990 and 2017.<ref>{{cite web |title=Fire death rates |url=https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/fire-death-rates |website=Our World in Data |access-date=17 November 2019}}</ref> | |||

| |align=right | |||

| }} | |||

| In the United States, fire and hot liquids are the most common causes of burns.<ref name=TBCChp3/> Of house fires that result in death, smoking causes 25% and heating devices cause 22%.<ref name=TBCChp4/> Almost half of injuries are due to efforts to fight a fire.<ref name=TBCChp4/> ] is caused by hot liquids or gases and most commonly occurs from exposure to hot drinks, high temperature ] in baths or showers, hot cooking oil, or steam.<ref>{{cite book| editor-last1 = Murphy | editor-first1 = Catherine | editor-last2 = Gardiner | editor-first2 = Mark | editor-first3 = Sarah | editor-last3 = Eisen |title=Training in paediatrics : the essential curriculum|year=2009|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=Oxford|isbn=978-0-19-922773-0|page=36|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FLBMvTff9sMC&pg=PA36| last1 = Eisen | first1 = Sarah | last2 = Murphy | first2 = Catherine |url-status=live |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20160425162003/https://books.google.com/books?id=FLBMvTff9sMC&pg=PA36 |archive-date=25 April 2016 }}</ref> Scald injuries are most common in children under the age of five<ref name=Tint2010/> and, in the United States and Australia, this population makes up about two-thirds of all burns.<ref name=TBCChp3/> Contact with hot objects is the cause of about 20–30% of burns in children.<ref name=TBCChp3/> Generally, scalds are first- or second-degree burns, but third-degree burns may also result, especially with prolonged contact.<ref name=Mag2008/> ] are a common cause of burns during holiday seasons in many countries.<ref>{{cite book|last=Peden|first=Margie|title=World report on child injury prevention|year=2008|publisher=World Health Organization|location=Geneva, Switzerland|isbn=978-92-4-156357-4|page=86|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UeXwoNh8sbwC&pg=PA86|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160424080036/https://books.google.com/books?id=UeXwoNh8sbwC&pg=PA86|archive-date=24 April 2016}}</ref> This is a particular risk for adolescent males.<ref>{{cite web|title=World report on child injury prevention |url=https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/child/injury/world_report/Burns_english.pdf |author=World Health Organization|url-status=live|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20130531030219/http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43851/1/9789241563574_eng.pdf |archive-date= 2013-05-31}}</ref> In the United States, for non-fatal burn injuries to children, white males under the age of 6 comprise most cases.<ref name=":0">{{cite journal | vauthors = Mitchell M, Kistamgari S, Chounthirath T, McKenzie LB, Smith GA | title = Children Younger Than 18 Years Treated for Nonfatal Burns in US Emergency Departments | journal = Clinical Pediatrics | volume = 59 | issue = 1 | pages = 34–44 | date = January 2020 | pmid = 31672059 | doi = 10.1177/0009922819884568 | s2cid = 207816299 | doi-access = free }}</ref> Thermal burns from grabbing/touching and spilling/splashing were the most common type of burn and mechanism, while the bodily areas most impacted were hands and fingers followed by head/neck.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| ===Chemical=== | |||

| Survival and outcome (scars, contractures, complications) of severe burn injuries is remarkably improved if the patient is treated in a specialized burn center/unit rather than a hospital. | |||

| {{main|Chemical burn}} | |||

| Chemical burns can be caused by over 25,000 substances,<ref name=Tint2010/> most of which are either a strong ] (55%) or a strong ] (26%).<ref name=Hard2012>{{cite journal | vauthors = Hardwicke J, Hunter T, Staruch R, Moiemen N | title = Chemical burns--an historical comparison and review of the literature | journal = Burns | volume = 38 | issue = 3 | pages = 383–7 | date = May 2012 | pmid = 22037150 | doi = 10.1016/j.burns.2011.09.014 }}</ref> Most chemical burn deaths are secondary to ].<ref name=Tint2010/> Common agents include: ] as found in toilet cleaners, ] as found in bleach, and ] as found in paint remover, among others.<ref name=Tint2010/> ] can cause particularly deep burns that may not become symptomatic until some time after exposure.<ref name=HF2008>{{cite journal | vauthors = Makarovsky I, Markel G, Dushnitsky T, Eisenkraft A | title = Hydrogen fluoride--the protoplasmic poison | journal = The Israel Medical Association Journal | volume = 10 | issue = 5 | pages = 381–5 | date = May 2008 | pmid = 18605366 }}</ref> ] may cause the breakdown of significant numbers of ]s.<ref name=Schw2010/> | |||

| == |

===Electrical=== | ||

| {{main|Electrical burn}} | |||

| {{howto}} | |||

| Electrical burns or injuries are classified as high voltage (greater than or equal to 1000 ]), low voltage (less than 1000 ]), or as ]s secondary to an ].<ref name=Tint2010/> The most common causes of electrical burns in children are electrical cords (60%) followed by electrical outlets (14%).<ref name=TBCChp3/><ref>{{cite journal|date=2017|title=Maggot debridement therapy for an electrical burn injury with instructions for the use of Lucilia sericata larvae|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321856095|journal= Journal of Wound Care|doi=10.12968/jowc.2017.26.12.734|last1=Nasoori|first1=A.|last2=Hoomand|first2=R.|volume=26|issue=12|pages=734–741|pmid=29244970}}</ref> ] may also result in electrical burns.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Edlich RF, Farinholt HM, Winters KL, Britt LD, Long WB | title = Modern concepts of treatment and prevention of lightning injuries | journal = Journal of Long-Term Effects of Medical Implants | volume = 15 | issue = 2 | pages = 185–96 | year = 2005 | pmid = 15777170 | doi = 10.1615/jlongtermeffmedimplants.v15.i2.60 }}</ref> Risk factors for being struck include involvement in outdoor activities such as mountain climbing, golf and field sports, and working outside.<ref name=RosenChp140/> Mortality from a lightning strike is about 10%.<ref name=RosenChp140/> | |||

| * The general and basic first aid treatment for most burns is to douse the affected area with cool water for at least 10 minutes in order to relieve the casualty’s pain and reduce swellings which could accompany a burn (Note that cold burns should not be doused with water). The burn should then be covered with a loose sterile and non-fluffy ] to prevent infection. The dressing must not exert pressure on the wound, due to the burn being likely to swell and increase in size. | |||

| While electrical injuries primarily result in burns, they may also cause ] or ] secondary to ] or ]s.<ref name=RosenChp140/> In high voltage injuries, most damage may occur internally and thus the extent of the injury cannot be judged by examination of the skin alone.<ref name=RosenChp140/> Contact with either low voltage or high voltage may produce ] or ].<ref name=RosenChp140/> | |||

| * Take note that chemical burns should be doused with cool water for at least 15 minutes in order to flush away any chemicals which could still be present on the wound. Any contaminated clothing, or any traces of the chemical which had caused the burn should also be removed in order to prevent further harm. | |||

| ===Radiation=== | |||

| * Take note that electrical burns are usually located at the entry and exit points of the voltage which has passed through the casualty’s body and into the ground. These burns are usually 3rd degree/full thickness and should also be doused with water for 10 minutes. Note that if the casualty has been struck by a high voltage, the casualty may also cease respiration and could be unconscious. Hence ] or ] should be performed if necessary. Also ensure that the casualty isn't still in contact with the electrical source before performing treatment. | |||

| {{Main|Radiation burn}} | |||

| ]s may be caused by protracted exposure to ] (such as from the sun, ]s or ]) or from ] (such as from ], ] or ]).<ref>{{cite book|last=Prahlow|first=Joseph|title=Forensic pathology for police, death investigators, and forensic scientists|year=2010|publisher=Humana|location=Totowa, N.J.|isbn=978-1-59745-404-9|page=485|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rF1WTiX0nHEC&pg=PA485|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160520001002/https://books.google.com/books?id=rF1WTiX0nHEC&pg=PA485|archive-date=20 May 2016}}</ref> Sun exposure is the most common cause of radiation burns and the most common cause of superficial burns overall.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Kearns RD, Cairns CB, Holmes JH, Rich PB, Cairns BA | title = Thermal burn care: a review of best practices. What should prehospital providers do for these patients? | journal = EMS World | volume = 42 | issue = 1 | pages = 43–51 | date = January 2013 | pmid = 23393776 }}</ref> There is significant variation in how easily people ] based on their ].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Balk SJ | title = Ultraviolet radiation: a hazard to children and adolescents | journal = Pediatrics | volume = 127 | issue = 3 | pages = e791-817 | date = March 2011 | pmid = 21357345 | doi = 10.1542/peds.2010-3502 | doi-access = free }}</ref> Skin effects from ionizing radiation depend on the amount of exposure to the area, with hair loss seen after 3 ], redness seen after 10 Gy, wet skin peeling after 20 Gy, and necrosis after 30 Gy.<ref name=RosenChp144>{{cite book|last=Marx|first=John|title=Rosen's emergency medicine : concepts and clinical practice|year=2010|publisher=Mosby/Elsevier|location=Philadelphia|isbn=978-0-323-05472-0|edition=7th|chapter=Chapter 144: Radiation Injuries}}</ref> Redness, if it occurs, may not appear until some time after exposure.<ref name=RosenChp144/> Radiation burns are treated the same as other burns.<ref name=RosenChp144/> ]s occur via thermal heating caused by the ].<ref name=Micro2001/> While exposures as short as two seconds may cause injury, overall this is an uncommon occurrence.<ref name=Micro2001>{{cite book|last=Krieger|first=John|title=Clinical environmental health and toxic exposures|year=2001|publisher=Lippincott Williams & Wilkins|location=Philadelphia, Pa. |isbn=978-0-683-08027-8|page=205|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PyUSgdZUGr4C&pg=PA205|edition=2nd|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160505132548/https://books.google.com/books?id=PyUSgdZUGr4C&pg=PA205|archive-date=5 May 2016}}</ref> | |||

| ===Non-accidental=== | |||

| * With larger burns the body has the potential to lose a large amount of body fluid, which can result in the casualty going into ]. Do not provide fluid when you suspect shock as this may induce vomiting. Hypovolaemic shock is a life threatening condition, thus medical assistance is imperative. When shock occurs, the first-aider should lie the casualty on the floor with his/her legs raised with the aid of a bystander or object, in order to divert blood flow to major organs in the torso. (The legs should be raised to around the shoulder length of a human kneeling on the floor) | |||

| In those hospitalized from scalds or fire burns, 3{{en dash}}10% are from assault.<ref name=Peck2012/> Reasons include: ], personal disputes, spousal abuse, ], and business disputes.<ref name=Peck2012/> An immersion injury or immersion scald may indicate child abuse.<ref name=Mag2008>{{cite journal | vauthors = Maguire S, Moynihan S, Mann M, Potokar T, Kemp AM | title = A systematic review of the features that indicate intentional scalds in children | journal = Burns | volume = 34 | issue = 8 | pages = 1072–81 | date = December 2008 | pmid = 18538478 | doi = 10.1016/j.burns.2008.02.011 }}</ref> It is created when an extremity, or sometimes the buttocks are held under the surface of hot water.<ref name=Mag2008/> It typically produces a sharp upper border and is often symmetrical,<ref name=Mag2008/> known as "sock burns", "glove burns", or "zebra stripes" - where folds have prevented certain areas from burning.<ref name=Scielo2011>{{cite journal | vauthors = Gondim RM, Muñoz DR, Petri V | title = Child abuse: skin markers and differential diagnosis | journal = Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia | volume = 86 | issue = 3 | pages = 527–36 | date = June 2011 | pmid = 21738970 | doi = 10.1590/S0365-05962011000300015 | doi-access = free }}</ref> Deliberate ] most often found on the face, or the back of the hands and feet.<ref name=Scielo2011/> Other high-risk signs of potential abuse include: circumferential burns, the absence of splash marks, a burn of uniform depth, and association with other signs of neglect or abuse.<ref name=TBCChp61/> | |||

| ], a form of ], occurs in some cultures, such as India where women have been burned in revenge for what the husband or his family consider an inadequate ].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Jutla RK, Heimbach D | title = Love burns: An essay about bride burning in India | journal = The Journal of Burn Care & Rehabilitation | volume = 25 | issue = 2 | pages = 165–70 | date = Mar–Apr 2004 | pmid = 15091143 | doi = 10.1097/01.bcr.0000111929.70876.1f }}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Peden|first=Margie|title=World report on child injury prevention|year=2008|publisher=World Health Organization|location=Geneva, Switzerland|isbn=978-92-4-156357-4|page=82|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UeXwoNh8sbwC&pg=PA82|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160617123505/https://books.google.com/books?id=UeXwoNh8sbwC&pg=PA82|archive-date=17 June 2016}}</ref> In Pakistan, ] represent 13% of intentional burns, and are frequently related to domestic violence.<ref name=TBCChp61>{{cite book|editor=Herndon D|title=Total burn care|publisher=Saunders|location=Edinburgh|isbn=978-1-4377-2786-9|pages=689–698|edition=4th|chapter=Chapter 61: Intential burn injuries|year=2012}}</ref> ] (setting oneself on fire) is also used as a form of protest in various parts of the world.<ref name=Epi2011/> | |||

| * Note that the following situations require medical assistance: | |||

| ** Any burn to the face, hands, feet, or genitalia. | |||

| ** Any 3rd degree/full thickness burn, or any burn that covers a large area. | |||

| ** Any burn that can interfere with respiration. | |||

| ** Any burn to an infant or elderly person. | |||

| ** Any chemical or electrical burn. | |||

| == Pathophysiology == | |||

| ==Scald== | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Unreferenced|date=December 2006}} | |||

| At temperatures greater than {{convert|44|C|F}}, proteins begin ] and start breaking down.<ref name=Rosen2009>{{cite book|last=Marx|first=John|title=Rosen's emergency medicine : concepts and clinical practice|year=2010|publisher=Mosby/Elsevier|location=Philadelphia|isbn=978-0-323-05472-0|edition=7th |chapter=Chapter 60: Thermal Burns}}</ref> This results in cell and tissue damage.<ref name=Tint2010/> Many of the direct health effects of a burn are caused by failure of the skin to perform its normal functions, which include: protection from bacteria, skin sensation, ], and prevention of evaporation of the body's water. Disruption of these functions can lead to infection, ], ], and ] via dehydration (i.e. water in the body evaporated away).<ref name=Tint2010/> Disruption of cell membranes causes cells to lose potassium to the spaces outside the cell and to take up water and sodium.<ref name=Tint2010/> | |||

| ] fluid.]] | |||

| '''Scalding''' is a specific type of burning that is caused by hot fluids or gasses. Examples of common liquids that cause scalds are water and cooking oil. Steam is a common gas that causes scalds. The injury is usually regional and usually does not cause death. More damage can be caused if hot liquids enter an orifice. However, deaths have occurred in more unusual circumstances, such as when people have accidentally broken a steam pipe. Young children, with their delicate skin, can suffer a serious burn in a much shorter time of exposure than the average adult. Also, their small body surface area means even a small amount of hot/burning liquid can cause severe burns over a large area of the body. | |||

| In large burns (over 30% of the total body surface area), there is a significant ].<ref name=Roj2012>{{cite journal | vauthors = Rojas Y, Finnerty CC, Radhakrishnan RS, Herndon DN | title = Burns: an update on current pharmacotherapy | journal = Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy | volume = 13 | issue = 17 | pages = 2485–94 | date = December 2012 | pmid = 23121414 | pmc = 3576016 | doi = 10.1517/14656566.2012.738195 }}</ref> This results in increased ] from the ],<ref name=Schw2010/> and subsequent tissue ].<ref name=Tint2010/> This causes overall ], with the remaining blood suffering significant ] loss, making the blood more concentrated.<ref name=Tint2010/> ] to organs like the kidneys and ] may result in ] and ].<ref>{{cite book|last=Hannon|first=Ruth|title=Porth pathophysiology : concepts of altered health states|year=2010|publisher=Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins|location=Philadelphia, PA|isbn=978-1-60547-781-7|page=1516|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2-MFXOEG0lcC&pg=PA1516|edition=1st Canadian|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160501122809/https://books.google.com/books?id=2-MFXOEG0lcC&pg=PA1516|archive-date=1 May 2016}}</ref> | |||

| '''''Table 2.'' Scald Time (Hot Water)''' | |||

| {|class="wikitable" | |||

| Increased levels of ] and ] can cause a ] that can last for years.<ref name=Roj2012/> This is associated with increased ], ], ], and poor ].<ref name=Roj2012/> | |||

| |{{bgcolor-gold}}|'''Temperature'''|| {{bgcolor-gold}}|'''Max duration until injury''' | |||

| ==Diagnosis== | |||

| Burns can be classified by depth, mechanism of injury, extent, and associated injuries. The most commonly used classification is based on the depth of injury. The depth of a burn is usually determined via examination, although a biopsy may also be used.<ref name=Tint2010/> It may be difficult to accurately determine the depth of a burn on a single examination and repeated examinations over a few days may be necessary.<ref name=Schw2010/> In those who have a ] or are dizzy and have a fire-related burn, ] should be considered.<ref name=CEM2012/> ] should also be considered.<ref name=Schw2010>{{cite book|last=Brunicardi|first=Charles|title=Schwartz's principles of surgery|year=2010|publisher=McGraw-Hill, Medical Pub. Division|location=New York|isbn=978-0-07-154769-7|edition=9th|chapter=Chapter 8: Burns}}</ref> | |||

| === Size === | |||

| ] | |||

| The size of a burn is measured as a percentage of ] (TBSA) affected by partial thickness or full thickness burns.<ref name=Tint2010/> First-degree burns that are only red in color and are not blistering are not included in this estimation.<ref name=Tint2010/> Most burns (70%) involve less than 10% of the TBSA.<ref name=TBCChp3/> | |||

| There are a number of methods to determine the TBSA, including the ], ], and estimations based on a person's palm size.<ref name=EMP2009/> The rule of nines is easy to remember but only accurate in people over 16 years of age.<ref name=EMP2009/> More accurate estimates can be made using Lund and Browder charts, which take into account the different proportions of body parts in adults and children.<ref name=EMP2009/> The size of a person's handprint (including the palm and fingers) is approximately 1% of their TBSA.<ref name=EMP2009/> | |||

| ===Severity=== | |||

| {| class="wikitable" style = "float: right; margin-left:15px; text-align:center" | |||

| |+American Burn Association severity classification<ref name=CEM2012/> | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! Minor !! Moderate !! Major | |||

| | 155F (68.3C) || 1 second | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | Adult <10% TBSA || Adult 10–20% TBSA || Adult >20% TBSA | |||

| | 145F (62.9C) || 3 seconds | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | Young or old < 5% TBSA || Young or old 5–10% TBSA|| Young or old >10% TBSA | |||

| | 135F (57.2C) || 10 seconds | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | <2% full thickness burn || 2–5% full thickness burn || >5% full thickness burn | |||

| | 130F (54.4C) || 30 seconds | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | || High voltage injury || High voltage burn | |||

| | 125F (51.6C) || 2 minutes | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | || Possible inhalation injury || Known inhalation injury | |||

| | 120F (48.8C) || 5 minutes | |||

| |- | |||

| | || Circumferential burn || Significant burn to face, joints, hands, or feet | |||

| |- | |||

| | || Other health problems || Associated injuries | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| To determine the need for referral to a specialized burn unit, the American Burn Association devised a classification system. Under this system, burns can be classified as major, moderate, and minor. This is assessed based on a number of factors, including total body surface area affected, the involvement of specific anatomical zones, the age of the person, and associated injuries.<ref name=CEM2012/> Minor burns can typically be managed at home, moderate burns are often managed in a hospital, and major burns are managed by a burn center.<ref name=CEM2012>{{cite book| veditors = Mahadevan SV, Garmel GM |title=An introduction to clinical emergency medicine|year=2012|publisher=Cambridge University Press |location=Cambridge|isbn=978-0-521-74776-9|pages=216–219|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pyAlcOfBhjIC&pg=PA216|edition=2nd|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160520142151/https://books.google.com/books?id=pyAlcOfBhjIC&pg=PA216|archive-date=20 May 2016}}</ref> Severe burn injury represents one of the most devastating forms of trauma.<ref>Barayan D, Vinaik R, Auger C, Knuth CM, Abdullahi A, Jeschke MG. Inhibition of Lipolysis With Acipimox Attenuates Postburn White Adipose Tissue Browning and Hepatic Fat Infiltration. ''Shock.'' 2020;53(2):137-145. doi:10.1097/SHK.0000000000001439, 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001439</ref> Despite improvements in burn care, patients can be left to suffer for as many as three years post-injury.<ref>Jeschke MG, Gauglitz GG, Kulp GA, Finnerty CC, Williams FN, Kraft R, Suman OE, Mlcak RP, Herndon DN: Long-term persistence of the pathophysi-ologic response to severe burn injury.PLoS One6:E21245, 2011.</ref> | |||

| ==Cold burn== | |||

| {{Unreferenced|date=December 2006}} | |||

| ==Prevention== | |||

| A '''cold burn''' (see ]) is a kind of burn which arises when the skin is in contact with a low-temperature body. They can be caused by prolonged contact with moderately cold bodies (] for instance) or brief contact with very cold bodies such as ], ], ], or ], all of which can be used in the process of ] removal. In such a case, the heat transfers from the skin and organs to the external cold body (as opposed to most other situations where the body causing the burn is hotter, and transfers the heat into the skin and organs). The effects are very similar to a "regular" burn. The remedy is also the same as for any burn: for a small wound keep the injured organ under a flow of comfortably temperatured water; the heat will then transfer slowly from the water to the organs and help the wound. Further treatment or treatment of more extended wound also as usual. | |||

| Historically, about half of all burns were deemed preventable.<ref name=TBCChp4/> Burn prevention programs have significantly decreased rates of serious burns.<ref name=Rosen2009/> Preventive measures include: limiting hot water temperatures, smoke alarms, sprinkler systems, proper construction of buildings, and fire-resistant clothing.<ref name=TBCChp4/> Experts recommend setting water heaters below {{convert|48.8|C|F|1}}.<ref name=TBCChp3/> Other measures to prevent scalds include using a thermometer to measure bath water temperatures, and splash guards on stoves.<ref name=Rosen2009/> While the effect of the regulation of fireworks is unclear, there is tentative evidence of benefit<ref>{{cite book|last=Jeschke|first=Marc |title=Handbook of Burns Volume 1: Acute Burn Care|year=2012|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-3-7091-0348-7|page=46|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=olshnFqCI0kC&pg=PA46|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160517021627/https://books.google.com/books?id=olshnFqCI0kC&pg=PA46|archive-date=17 May 2016}}</ref> with recommendations including the limitation of the sale of fireworks to children.<ref name=TBCChp3/> | |||

| ==Management== | |||

| Resuscitation begins with the assessment and stabilization of the person's airway, breathing and circulation.<ref name=EMP2009/> If inhalation injury is suspected, early ] may be required.<ref name=Schw2010/> This is followed by care of the burn wound itself. People with extensive burns may be wrapped in clean sheets until they arrive at a hospital.<ref name=Schw2010/> As burn wounds are prone to infection, a tetanus booster shot should be given if an individual has not been immunized within the last five years.<ref>{{cite book|editor=Klingensmith M|title=The Washington manual of surgery|year=2007|publisher=Lippincott Williams & Wilkins|location=Philadelphia, Pa.|isbn=978-0-7817-7447-5|page=422|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XTYAxJntdvAC&pg=PA422|edition=5th|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160520044310/https://books.google.com/books?id=XTYAxJntdvAC&pg=PA422|archive-date=20 May 2016}}</ref> In the United States, 95% of burns that present to the emergency department are treated and discharged; 5% require hospital admission.<ref name=Epi2011/> With major burns, early feeding is important.<ref name=Roj2012/><!-- early enteral nutrition --> Protein intake should also be increased, and trace elements and vitamins are often required.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Rousseau AF, Losser MR, Ichai C, Berger MM | title = ESPEN endorsed recommendations: nutritional therapy in major burns | language = en | journal = Clinical Nutrition | volume = 32 | issue = 4 | pages = 497–502 | date = August 2013 | pmid = 23582468 | doi = 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.02.012 }}</ref> ] may be useful in addition to traditional treatments.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Cianci P, Slade JB, Sato RM, Faulkner J | title = Adjunctive hyperbaric oxygen therapy in the treatment of thermal burns | journal = Undersea & Hyperbaric Medicine | volume = 40 | issue = 1 | pages = 89–108 | date = Jan–Feb 2013 | pmid = 23397872 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Intravenous fluids=== | |||

| In those with poor ], boluses of ] should be given.<ref name=EMP2009/> In children with more than 10–20% TBSA (Total Body Surface Area) burns, and adults with more than 15% TBSA burns, formal fluid resuscitation and monitoring should follow.<ref name=EMP2009/><ref name=Enoch2009>{{cite journal | vauthors = Enoch S, Roshan A, Shah M | s2cid = 40561988 | title = Emergency and early management of burns and scalds | journal = BMJ | volume = 338 | pages = b1037 | date = April 2009 | pmid = 19357185 | doi = 10.1136/bmj.b1037 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Hettiaratchy S, Papini R | title = Initial management of a major burn: II--assessment and resuscitation | journal = BMJ | volume = 329 | issue = 7457 | pages = 101–3 | date = July 2004 | pmid = 15242917 | pmc = 449823 | doi = 10.1136/bmj.329.7457.101 }}</ref> This should be begun pre-hospital if possible in those with burns greater than 25% TBSA.<ref name=Enoch2009/> The ] can help determine the volume of intravenous fluids required over the first 24 hours.<!-- <ref name=Schw2010/> --> The formula is based on the affected individual's TBSA and weight. Half of the fluid is administered over the first 8 hours, and the remainder over the following 16 hours.<!-- <ref name=Schw2010/> --> The time is calculated from when the burn occurred, and not from the time that fluid resuscitation began.<!-- <ref name=Schw2010/> --> Children require additional maintenance fluid that includes ].<ref name=Schw2010/> Additionally, those with inhalation injuries require more fluid.<ref>{{cite book|last=Jeschke|first=Marc|title=Handbook of Burns Volume 1: Acute Burn Care|year=2012|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-3-7091-0348-7|page=77|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=olshnFqCI0kC&pg=PA77|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160519022020/https://books.google.com/books?id=olshnFqCI0kC&pg=PA77|archive-date=19 May 2016}}</ref> While inadequate fluid resuscitation may cause problems, over-resuscitation can also be detrimental.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Endorf FW, Ahrenholz D | title = Burn management | journal = Current Opinion in Critical Care | volume = 17 | issue = 6 | pages = 601–5 | date = December 2011 | pmid = 21986459 | doi = 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32834c563f | s2cid = 5525939 }}</ref> The formulas are only a guide, with infusions ideally tailored to a ] of >30 mL/h in adults or >1mL/kg in children and ] greater than 60 mmHg.<ref name=Schw2010/> | |||

| While ] is often used, there is no evidence that it is superior to ].<ref name=EMP2009/> ] appear just as good as ], and as colloids are more expensive they are not recommended.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Lewis SR, Pritchard MW, Evans DJ, Butler AR, Alderson P, Smith AF, Roberts I | title = Colloids versus crystalloids for fluid resuscitation in critically ill people | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | volume = 8 | pages = CD000567 | date = August 2018 | issue = 8 | pmid = 30073665 | pmc = 6513027 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD000567.pub7 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Eljaiek R, Heylbroeck C, Dubois MJ | title = Albumin administration for fluid resuscitation in burn patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis | journal = Burns | volume = 43 | issue = 1 | pages = 17–24 | date = February 2017 | pmid = 27613476 | doi = 10.1016/j.burns.2016.08.001 }}</ref> ] are rarely required.<ref name=Tint2010/> They are typically only recommended when the ] level falls below 60-80 g/L (6-8 g/dL)<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Curinga G, Jain A, Feldman M, Prosciak M, Phillips B, Milner S | title = Red blood cell transfusion following burn | journal = Burns | volume = 37 | issue = 5 | pages = 742–52 | date = August 2011 | pmid = 21367529 | doi = 10.1016/j.burns.2011.01.016 }}</ref> due to the associated risk of complications.<ref name=Schw2010/> Intravenous catheters may be placed through burned skin if needed or ]s may be used.<ref name=Schw2010/> | |||

| === Wound care === | |||

| Early cooling (within 30 minutes of the burn) reduces burn depth and pain, but care must be taken as over-cooling can result in hypothermia.<ref name=Tint2010/><ref name=EMP2009/> It should be performed with cool water {{convert|10|–|25|C|F|1}} and not ice water as the latter can cause further injury.<ref name=EMP2009/><ref name=Rosen2009/> Chemical burns may require extensive irrigation.<ref name=Tint2010/> Cleaning with soap and water, ], and application of dressings are important aspects of wound care.<!-- <ref name=Rosen2009/> --> If intact blisters are present, it is not clear what should be done with them.<!-- <ref name=Rosen2009/> --> Some tentative evidence supports leaving them intact.<!-- <ref name=Rosen2009/> --> Second-degree burns should be re-evaluated after two days.<ref name=Rosen2009/> | |||

| In the management of first and second-degree burns, little quality evidence exists to determine which dressing type to use.<ref name="The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews">{{cite journal | vauthors = Wasiak J, Cleland H, Campbell F, Spinks A | title = Dressings for superficial and partial thickness burns | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | volume = 3 | issue = 3 | pages = CD002106 | date = March 2013 | pmid = 23543513 | pmc = 7065523 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD002106.pub4 | hdl-access = free | hdl = 10072/58266 }}</ref> It is reasonable to manage first-degree burns without dressings.<ref name=Rosen2009/> While topical antibiotics are often recommended, there is little evidence to support their use.<ref name=Anti2010/><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Hoogewerf CJ, Hop MJ, Nieuwenhuis MK, Oen IM, Middelkoop E, Van Baar ME | title = Topical treatment for facial burns | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | volume = 2020 | pages = CD008058 | date = July 2020 | issue = 7 | pmid = 32725896 | pmc = 7390507 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.cd008058.pub3 }}</ref> ] (a type of antibiotic) is not recommended as it potentially prolongs healing time.<ref name="The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews" /><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Barajas-Nava LA, López-Alcalde J, Roqué i Figuls M, Solà I, Bonfill Cosp X | title = Antibiotic prophylaxis for preventing burn wound infection | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | issue = 6 | pages = CD008738 | date = June 2013 | pmid = 23740764 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD008738.pub2 | doi-access = free | pmc = 11303740 }}</ref> There is insufficient evidence to support the use of dressings containing ]<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Storm-Versloot MN, Vos CG, Ubbink DT, Vermeulen H | title = Topical silver for preventing wound infection | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | issue = 3 | pages = CD006478 | date = March 2010 | pmid = 20238345 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD006478.pub2 | veditors = Storm-Versloot MN }}</ref> or ].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Dumville JC, Munson C, Christie J | title = Negative pressure wound therapy for partial-thickness burns | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | volume = 2014 | issue = 12 | pages = CD006215 | date = December 2014 | pmid = 25500895 | pmc = 7389115 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD006215.pub4 }}</ref> Silver sulfadiazine does not appear to differ from silver containing foam dressings with respect to healing.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Chaganti P, Gordon I, Chao JH, Zehtabchi S | title = A systematic review of foam dressings for partial thickness burns | journal = The American Journal of Emergency Medicine | volume = 37 | issue = 6 | pages = 1184–1190 | date = June 2019 | pmid = 31000315 | doi = 10.1016/j.ajem.2019.04.014 | s2cid = 121615225 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Medications=== | |||

| Burns can be very painful and a number of different options may be used for ].<!-- <ref name=Rosen2009/> --> These include simple analgesics (such as ] and ]) and ] such as morphine.<!-- <ref name=Rosen2009/> --> ] may be used in addition to ]s to help with anxiety.<ref name=Rosen2009/> During the healing process, ], ], or ] may be used to aid with itching.<ref name=Itchy2009/> Antihistamines, however, are only effective for this purpose in 20% of people.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Zachariah JR, Rao AL, Prabha R, Gupta AK, Paul MK, Lamba S | title = Post burn pruritus--a review of current treatment options | journal = Burns | volume = 38 | issue = 5 | pages = 621–9 | date = August 2012 | pmid = 22244605 | doi = 10.1016/j.burns.2011.12.003 }}</ref> There is tentative evidence supporting the use of ]<ref name=Itchy2009/> and its use may be reasonable in those who do not improve with antihistamines.<ref name=TBCChp64>{{cite book|editor=Herndon D|title=Total burn care|publisher=Saunders|location=Edinburgh|isbn=978-1-4377-2786-9|page=726|edition=4th|chapter=Chapter 64: Management of pain and other discomforts in burned patients|year=2012}}</ref> Intravenous ] requires more study before it can be recommended for pain.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Wasiak J, Mahar PD, McGuinness SK, Spinks A, Danilla S, Cleland H, Tan HB | title = Intravenous lidocaine for the treatment of background or procedural burn pain | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | volume = 10 | issue = 10 | pages = CD005622 | date = October 2014 | pmid = 25321859 | pmc = 6508369 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD005622.pub4 }}</ref> | |||

| Intravenous ]s are recommended before surgery for those with extensive burns (>60% TBSA).<ref name=TBCChp31>{{cite book|editor=Herndon D|title=Total burn care|publisher=Saunders|location=Edinburgh|isbn=978-1-4377-2786-9|page=664|edition=4th|chapter=Chapter 31: Etiology and prevention of multisystem organ failure|year=2012}}</ref> {{As of|2008}}, guidelines do not recommend their general use due to concerns regarding ]<ref name=Anti2010>{{cite journal | vauthors = Avni T, Levcovich A, Ad-El DD, Leibovici L, Paul M | title = Prophylactic antibiotics for burns patients: systematic review and meta-analysis | journal = BMJ | volume = 340 | pages = c241 | date = February 2010 | pmid = 20156911 | pmc = 2822136 | doi = 10.1136/bmj.c241 }}</ref> and the increased risk of ].<ref name=Schw2010/> Tentative evidence, however, shows that they may improve survival rates in those with large and severe burns.<ref name=Anti2010/> ] has not been found effective to prevent or treat anemia in burn cases.<ref name=Schw2010/> In burns caused by hydrofluoric acid, ] is a specific ] and may be used intravenously and/or topically.<ref name=HF2008/> ] (rhGH) in those with burns that involve more than 40% of their body appears to speed healing without affecting the risk of death.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Breederveld RS, Tuinebreijer WE | title = Recombinant human growth hormone for treating burns and donor sites | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | volume = 2014 | issue = 9 | pages = CD008990 | date = September 2014 | pmid = 25222766 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD008990.pub3 | pmc = 7119450 }}</ref> The use of ] is of unclear evidence.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Snell JA, Loh NH, Mahambrey T, Shokrollahi K | title = Clinical review: the critical care management of the burn patient | journal = Critical Care | volume = 17 | issue = 5 | pages = 241 | date = October 2013 | pmid = 24093225 | pmc = 4057496 | doi = 10.1186/cc12706 | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| ] (Stratagraft) was approved for medical use in the United States in June 2021.<ref name="FDA PR 20210615">{{cite press release | title=FDA Approves StrataGraft for the Treatment of Adults with Thermal Burns | website=U.S. ] (FDA) | date=15 June 2021 | url=https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-stratagraft-treatment-adults-thermal-burns | access-date=20 April 2023}}</ref> | |||

| ===Surgery=== | |||

| Wounds requiring surgical closure with ] or flaps (typically anything more than a small full thickness burn) should be dealt with as early as possible.<ref>{{cite book|last=Jeschke|first=Marc|title=Handbook of Burns Volume 1: Acute Burn Care|year=2012|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-3-7091-0348-7|page=266|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=olshnFqCI0kC&pg=PA266|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160510210401/https://books.google.com/books?id=olshnFqCI0kC&pg=PA266|archive-date=10 May 2016}}</ref> Circumferential burns of the limbs or chest may need urgent surgical release of the skin, known as an ].<ref name=Surgery2009/> This is done to treat or prevent problems with distal circulation, or ventilation.<ref name=Surgery2009>{{cite journal | vauthors = Orgill DP, Piccolo N | title = Escharotomy and decompressive therapies in burns | journal = Journal of Burn Care & Research | volume = 30 | issue = 5 | pages = 759–68 | date = Sep–Oct 2009 | pmid = 19692906 | doi = 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181b47cd3 }}</ref> It is uncertain if it is useful for neck or digit burns.<ref name=Surgery2009/> ] may be required for electrical burns.<ref name=Surgery2009/> | |||

| Skin grafts can involve temporary skin substitutes, derived from animal (human donor or pig) skin or synthesized. They are used to cover the wound as a dressing, preventing infection and fluid loss, but will eventually need to be removed. Alternatively, human skin can be treated to be left on permanently without rejection.<ref>{{cite web |title=General data about burns |url=http://burncentrecare.co.uk/burn_wounds_surgery.htm |website=Burn Centre Care |access-date=24 June 2019 |archive-date=18 October 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181018055607/http://burncentrecare.co.uk/burn_wounds_surgery.htm |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| There is no evidence that the use of copper sulphate to visualise phosphorus particles for removal can help with wound healing due to phosphorus burns. Meanwhile, absorption of copper sulphate into the blood circulation can be harmful.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Barqouni L, Abu Shaaban N, Elessi K | title = Interventions for treating phosphorus burns | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | issue = 6 | pages = CD008805 | date = June 2014 | volume = 2014 | pmid = 24896368 | pmc = 7173745 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD008805.pub3 | collaboration = Cochrane Wounds Group }}</ref> | |||

| ===Alternative medicine=== | |||

| Honey has been used since ancient times to aid wound healing and may be beneficial in first- and second-degree burns.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Wijesinghe M, Weatherall M, Perrin K, Beasley R | title = Honey in the treatment of burns: a systematic review and meta-analysis of its efficacy | journal = The New Zealand Medical Journal | volume = 122 | issue = 1295 | pages = 47–60 | date = May 2009 | pmid = 19648986 }}</ref> There is moderate evidence that honey helps heal partial thickness burns.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Norman G, Christie J, Liu Z, Westby MJ, Jefferies JM, Hudson T, Edwards J, Mohapatra DP, Hassan IA, Dumville JC | display-authors = 6 | title = Antiseptics for burns | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | volume = 7 | pages = CD011821 | date = July 2017 | issue = 7 | pmid = 28700086 | pmc = 6483239 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.cd011821.pub2 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Jull AB, Cullum N, Dumville JC, Westby MJ, Deshpande S, Walker N | title = Honey as a topical treatment for wounds | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | volume = 3 | issue = 3 | pages = CD005083 | date = March 2015 | pmid = 25742878 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD005083.pub4 | pmc = 9719456 }}</ref> The evidence for ] is of poor quality.<ref name=Aloe2012/> While it might be beneficial in reducing pain,<ref name=AFP2012>{{cite journal | vauthors = Lloyd EC, Rodgers BC, Michener M, Williams MS | title = Outpatient burns: prevention and care | journal = American Family Physician | volume = 85 | issue = 1 | pages = 25–32 | date = January 2012 | pmid = 22230304 }}</ref> and a review from 2007 found tentative evidence of improved healing times,<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Maenthaisong R, Chaiyakunapruk N, Niruntraporn S, Kongkaew C | title = The efficacy of aloe vera used for burn wound healing: a systematic review | journal = Burns | volume = 33 | issue = 6 | pages = 713–8 | date = September 2007 | pmid = 17499928 | doi = 10.1016/j.burns.2006.10.384 }}</ref> a subsequent review from 2012 did not find improved healing over silver sulfadiazine.<ref name=Aloe2012>{{cite journal | vauthors = Dat AD, Poon F, Pham KB, Doust J | title = Aloe vera for treating acute and chronic wounds | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | volume = 2012 | issue = 2 | pages = CD008762 | date = February 2012 | pmid = 22336851 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD008762.pub2 | pmc = 9943919 | url = http://epublications.bond.edu.au/hsm_pubs/499 }}{{Dead link|date=February 2022 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> There were only three randomized controlled trials for the use of plants for burns, two for aloe vera and one for oatmeal.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Bahramsoltani R, Farzaei MH, Rahimi R | title = Medicinal plants and their natural components as future drugs for the treatment of burn wounds: an integrative review | journal = Archives of Dermatological Research | volume = 306 | issue = 7 | pages = 601–17 | date = September 2014 | pmid = 24895176 | doi = 10.1007/s00403-014-1474-6 | s2cid = 23859340 }}</ref> | |||

| There is little evidence that ] helps with keloids or scarring.<ref name=Juck2009/> Butter is not recommended.<ref>{{cite book| first1 = Carol | last1 = Turkington | first2 = Jeffrey S | last2 = Dover | first3 = Birck | last3 = Cox |title=The encyclopedia of skin and skin disorders|year=2007|publisher=Facts on File|location=New York, NY|isbn=978-0-8160-7509-6|page=64|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GKVPHoIs8uIC&pg=PA64|edition=3rd|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160518052410/https://books.google.com/books?id=GKVPHoIs8uIC&pg=PA64|archive-date=18 May 2016}}</ref> In low income countries, burns are treated up to one-third of the time with ], which may include applications of eggs, mud, leaves or cow dung.<ref name=LMIC2006>{{cite journal | vauthors = Forjuoh SN | title = Burns in low- and middle-income countries: a review of available literature on descriptive epidemiology, risk factors, treatment, and prevention | journal = Burns | volume = 32 | issue = 5 | pages = 529–37 | date = August 2006 | pmid = 16777340 | doi = 10.1016/j.burns.2006.04.002 }}</ref> Surgical management is limited in some cases due to insufficient financial resources and availability.<ref name=LMIC2006/> There are a number of other methods that may be used in addition to medications to reduce procedural pain and anxiety including: ], ], and behavioral approaches such as distraction techniques.<ref name=TBCChp64/> | |||

| === Patient support === | |||

| Burn patients require support and care – both physiological and psychological. Respiratory failure, sepsis, and multi-organ system failure are common in hospitalized burn patients. To prevent hypothermia and maintain normal body temperature, burn patients with over 20% of burn injuries should be kept in an environment with the temperature at or above 30 degree Celsius.<ref>{{cite web|date=2020-09-26|title=Medically Sound: Treating and Caring for Burn, Electricity, and Radiation Victims|url=https://urmedlife.blogspot.com/2020/09/accidentally-scarred-for-life-yet-still.html|access-date=2020-11-01|website=Medically Sound}}</ref>{{better source needed|date=November 2020}} | |||

| Metabolism in burn patients proceeds at a higher than normal speed due to the whole-body process and rapid fatty acid substrate cycles, which can be countered with an adequate supply of energy, nutrients, and antioxidants. Enteral feeding a day after resuscitation is required to reduce risk of infection, recovery time, non-infectious complications, hospital stay, long-term damage, and mortality. Controlling blood glucose levels can have an impact on liver function and survival. | |||

| Risk of thromboembolism is high and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) that does not resolve with maximal ventilator use is also a common complication. Scars are long-term after-effects of a burn injury. Psychological support is required to cope with the aftermath of a fire accident, while to prevent scars and long-term damage to the skin and other body structures consulting with burn specialists, preventing infections, consuming nutritious foods, early and aggressive rehabilitation, and using compressive clothing are recommended. | |||

| ==Assessing burns== | |||

| {{main|Total body surface area}} | |||

| Burns are assessed in terms of total body surface area (TBSA), which is the percentage affected by partial thickness or full thickness burns (superficial thickness burns are not counted). The ] is used as a quick and useful way to estimate the affected TBSA. | |||

| ==Prognosis== | |||

| {| align="left" | |||

| {| class="wikitable" style = "float: right; margin-left:15px; text-align:center" | |||

| |+ Prognosis in the US<ref name=ABA2012pg10>National Burn Repository, Pg. 10</ref> | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| !TBSA !! Mortality | |||

| || | |||

| {|class="wikitable" | |||

| |+ '''''Table 3''. Rule of nines for assessment of total body surface area affected by a burn - Adult''' | |||

| |{{bgcolor-gold}}|'''Anatomic structure'''||{{bgcolor-gold}}|'''Surface area''' | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | |

| 0–9% || 0.6% | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| | 10–19% || 2.9% | |||

| |Anterior Torso||18% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | 20–29% || 8.6% | |||

| |Posterior Torso||18% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | |

| 30–39% || 16% | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| | |

| 40–49% || 25% | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| | |

| 50–59% || 37% | ||

| |} | |||

| |} | |||

| {| align="center" | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | 60–69% || 43% | |||

| || | |||

| {|class="wikitable" | |||

| |+ '''''Table 4''. Rule of nines for assessment of total body surface area affected by a burn - Infant''' | |||

| |{{bgcolor-gold}}|'''Anatomic structure'''||{{bgcolor-gold}}|'''Surface area''' | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | |

| 70–79% || 57% | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| | 80–89% || 73% | |||

| |Anterior Torso||18% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | 90–100%|| 85% | |||

| |Posterior Torso||18% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | |

|Inhalation||23% | ||

| |- | |||

| |Each Arm||9% | |||

| |- | |||

| |Perineum||1% | |||

| |} | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| The prognosis is worse in those with larger burns, those who are older, and females.<ref name=Tint2010/> The presence of a ] injury, other significant injuries such as long bone fractures, and serious co-morbidities (e.g. heart disease, diabetes, psychiatric illness, and suicidal intent) also influence prognosis.<ref name=Tint2010/> On average, of those admitted to burn centers in the United States, 4% die,<ref name=TBCChp3/> with the outcome for individuals dependent on the extent of the burn injury. For example, admittees with burn areas less than 10% TBSA had a mortality rate of less than 1%, while admittees with over 90% TBSA had a mortality rate of 85%.<ref name=ABA2012pg10/> In Afghanistan, people with more than 60% TBSA burns rarely survive.<ref name=TBCChp3/> The ] has historically been used to determine prognosis of major burns. However, with improved care, it is no longer very accurate.<ref name=Schw2010/> The score is determined by adding the size of the burn (% TBSA) to the age of the person and taking that to be more or less equal to the risk of death.<ref name=Schw2010/> Burns in 2013 resulted in 1.2 million ] and 12.3 million ].<ref name=GBD2016/> | |||

| === Complications === | |||

| ==Management== | |||

| A number of complications may occur, with ]s being the most common.<ref name=TBCChp3/> In order of frequency, potential complications include: ], ], ] and respiratory failure.<ref name=TBCChp3/> Risk factors for infection include: burns of more than 30% TBSA, full-thickness burns, extremes of age (young or old), or burns involving the legs or perineum.<ref>{{cite book |editor-first1 = Christopher | editor-last1 = King | editor-first2 = Fred M. | editor-last2 = Henretig | editor-first3 = Brent R. | editor-last3 = King | editor-first4 = John | editor-last4 = Loiselle | editor-first5 = Richard M. | editor-last5 = Ruddy| editor-first6 = James F. | editor-last6 = Wiley II |title=Textbook of pediatric emergency procedures|year=2008|publisher=Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins|location=Philadelphia|isbn=978-0-7817-5386-9|page=1077|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Xi0rlODiFY0C&pg=PA1077|edition=2nd|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160522005447/https://books.google.com/books?id=Xi0rlODiFY0C&pg=PA1077|archive-date=22 May 2016}}</ref> Pneumonia occurs particularly commonly in those with inhalation injuries.<ref name=Schw2010/> | |||

| The first step in managing a person with a burn is to stop the burning process. With dry powder burns, the powder should be brushed off first. With other burns, the affected area should be rinsed with a large amount of clean water to remove ] and help stop the burning process. Cold water should never be applied to any person with extensive burns, as it may severely compromise the burn victim's temperature status. | |||