| Revision as of 15:50, 22 July 2007 editUrthogie (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users15,196 edits →Peace lines: add section← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 15:44, 18 October 2024 edit undoGaldrack (talk | contribs)447 edits →Education: removing previous edit, the topic is on who ran the schools and the segregation, the source of funding is a separate matter. | ||

| (234 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Sociopolitical division between Irish republicans and unionists}} | |||

| {{Expand}} | |||

| {{EngvarB|date=January 2021}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=November 2013}} | |||

| ]" along Springmartin Road in ], with a fortified police station at one end]] | |||

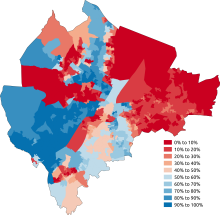

| ], 2011, showing percentage of respondents identifying as Catholic in each area.]]{{Segregation}} | |||

| '''Segregation in Northern Ireland''' is a long-running issue in the political and social ]. The ] involves Northern Ireland's two main voting blocs—]/]s (mainly ]) and ]/] (mainly ]). It is often seen as both a cause and effect of the "]". | |||

| ⚫ | A combination of political, religious and social differences plus the threat of intercommunal tensions and violence has led to widespread self-segregation of the two communities. Catholics and Protestants lead largely separate lives in a situation that some have dubbed "self-imposed ]".<ref name="SelfImposed">"", by ], published in '']'' on | ||

| {{Template:Allegations of apartheid}} | |||

| Wednesday 14 April 2004. Accessed on Sunday, 22 July 2007.</ref> | |||

| '''Allegations of Northern Irish apartheid''' draw analogies between ] and ]. The term "apartheid" has been used to refer to the partition of Northern Irish society into two communities which tend to reduce interaction with each other. | |||

| __TOC__ | |||

| ==Education== | ==Education== | ||

| ] is heavily segregated. Most ]s in Northern Ireland are predominantly Protestant, while the majority of Catholic children attend schools maintained by the ]. In 2006, 90% of children in Northern Ireland were in segregated schools,<ref>], Daily Hansard, 18 July 2006 : Column 1189 , retrieved 22 July 2007</ref> by 2017 that figure had risen to 93%.<ref>{{Cite web|title=The Growth of Integrated Education since the Good Friday Agreement| url=https://www.nicie.org/news/press-releases/9689-2/|access-date=2020-06-23|website=Integrated Education Northern Ireland|language=en-US}}</ref> The consequence is, as one commentator has put it, that "the overwhelming majority of Ulster's children can go from four to 18 without having a serious conversation with a member of a rival creed."<ref name="Cohen">"", by ]. Published in '']'' on Sunday 13 May 2007. Accessed on 22 July 2007.</ref> The prevalence of segregated education has been cited as a major factor in maintaining ] (marriage within one's own group).<ref>Michael P. Hornsby-Smith, ''Roman Catholics in England: Studies in Social Structure since the Second World War''. Cambridge University Press, 1987. {{ISBN|0-521-30313-3}}</ref> | |||

| ] stated, | |||

| {{quote|"In Northern Ireland, apartheid starts in schools; 90 per cent of children in Northern Ireland still go to separate faith schools"<ref>], Daily Hansard, 18 July 2006 : Column 1189 , retrieved 22 July 2007</ref>}} | |||

| The ] movement has sought to reverse this trend by establishing non-denominational schools. Such schools are, however, still the exception to the general trend of segregated education. Integrated schools in Northern Ireland have been established through the voluntary efforts of parents. The churches have not been involved in the development of integrated education.<ref></ref> However, both the Catholic Church and Protestant denominations, along with state-run institutions, have supported and organised cross-community school projects such as joint ], educational classes and forums wherein pupils can come together to share their beliefs, values and cultures.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/news/education/crosscommunity-school-project-launched-28688767.html|title=Cross-community school project launched|newspaper=Belfasttelegraph}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.ark.ac.uk/publications/updates/update55.pdf|title = Publications Overview | ARK - Access Research Knowledge}}</ref> The academic ] argued that "the two factors which do most to divide Protestants as a whole from Catholics as a whole are endogamy and separate education".<ref>John Whyte (1990) ''Interpreting Northern Ireland'', Oxford: Clarendon Press, p. 48</ref> | |||

| ] writes in "Stop this Drift into Educational Apartheid" in '']'': | |||

| ==Employment== | |||

| {{quote|"Limiting sectarian education was a noble aspiration of the Good Friday Agreement. Even Sinn Fein politicians said they supported it. Politicians appeared to recognise that the integrated schools movement has provided one of the few solid grounds for optimism. Run by parents who were determined not to start segregating toddlers, it was creating schools that were not merely non-sectarian, but anti-sectarian.}} | |||

| Historically, employment in the ] was highly segregated in favour of Protestants, particularly at senior levels of the public sector, in certain then-important sectors of the economy, such as shipbuilding and heavy engineering, and strategically important areas such as the police.<ref name="encarta">"Northern Ireland," Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2007</ref> Emigration to seek employment was therefore significantly more prevalent among the Catholic population. As a result, Northern Ireland's demography shifted further in favour of Protestants leaving their ascendancy seemingly impregnable by the late 1950s. | |||

| A 1987 survey found that 80 per cent of the work forces surveyed were described by respondents as consisting of a majority of one denomination; 20 per cent were overwhelmingly uni-denominational, with 95–100 per cent Catholic or Protestant employees. However, large organisations were much less likely to be segregated, and the level of segregation has decreased over the years.<ref name="mitchell">Claire Mitchell, ''Religion, Identity And Politics in Northern Ireland: Boundaries of Belonging and Belief'', p. 63. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd, 2006. {{ISBN|0-7546-4155-4}}</ref> | |||

| {{quote|For all the praise given to them, just 5 per cent of Northern Ireland's pupils attend integrated schools today. As Philip O'Sullivan of the Northern Ireland Council for Integrated Education put it, the overwhelming majority of Ulster's children can go from four to 18 without having a serious conversation with a member of a rival creed. They mingle only when they reach the workplace because, oddly, the religious discrimination on which the education system rests is illegal at work.<ref name="Cohen">"", by ]. Published in '']'' on Sunday May 13, 2007. Accessed on July 22nd, 2007.</ref>}} | |||

| The ] has introduced numerous laws and regulations since the mid-1990s to prohibit discrimination on religious grounds, with the ] (originally the Fair Employment Agency) exercising statutory powers to investigate allegations of discriminatory practices in Northern Ireland business and organisations.<ref name="encarta" /> This has had a significant impact on the level of segregation in the workplace;<ref name="mitchell" /> John Whyte concludes that the result is that "segregation at work is one of the least acute forms of segregation in Northern Ireland."<ref>John Whyte, ''Interpreting Northern Ireland'', p. 37. Clarendon Press, 1990. {{ISBN|0-19-827848-9}}</ref> | |||

| ==Peace lines== | |||

| In an article titled "Apartheid" published in the '']'' ] refers also to : | |||

| {{quote|"those ]s - usually high walls snaking along the demographic faults, crossing roads and slicing streets in two - are proliferating: there are twice as many today as there were a decade ago."<ref>], 28 November 2005, retrieved 22 July 2007</ref>}} | |||

| ==Housing== | ==Housing== | ||

| ⚫ | ].]] | ||

| ⚫ | |||

| ] | |||

| Wednesday April 14, 2004. Accessed on Sunday, July 22nd, 2007.</ref> Two years later, ] of '']'' explored this theme in depth in an article entitled "Self-imposed Apartheid." She wrote: | |||

| Public housing is overwhelmingly segregated between the two communities. Inter-communal tensions have forced substantial numbers of people to move from mixed areas into areas inhabited exclusively by one denomination, thus increasing the degree of polarisation and segregation. The extent of self-segregation grew very rapidly with the outbreak of ]. In 1969, 69 per cent of Protestants and 56 per cent of Catholics lived in streets where they were in their own majority; as the result of large-scale flight from mixed areas between 1969 and 1971 following outbreaks of violence, the respective proportions had by 1972 increased to 99 per cent of Protestants and 75 per cent of Catholics.<ref>Frank Wright, ''Northern Ireland: A Comparative Analysis'', p. 205. Rowman & Littlefield, 1988. {{ISBN|0-7171-1428-7}}</ref> In Belfast, the 1970s were a time of rising residential segregation.<ref>Paul Doherty and Michael A. Poole (1997) , ''Geographical Review'' 87(4), pp. 520–536</ref> It was estimated in 2004 that 92.5% of public housing in Northern Ireland was divided along religious lines, with the figure rising to 98% in ].<ref name="SelfImposed"/> Self-segregation is a continuing process, despite the ]. It was estimated in 2005 that more than 1,400 people a year were being forced to move as a consequence of ].<ref>Neil Jarman, Institute for Conflict Research, March 2005 http://www.serve.com/pfc/misc/violence.pdf</ref> | |||

| In response to inter-communal violence, the ] constructed a number of high walls called "]" to separate rival neighbourhoods. These have multiplied over the years and now number forty separate barriers, mostly located in Belfast. Despite the moves towards peace between Northern Ireland's political parties and most of its paramilitary groups, the construction of "peace lines" has actually increased during the ongoing peace process; the number of "peace lines" doubled in the ten years between 1995 and 2005.<ref name="NS">], 28 November 2005, retrieved 22 July 2007</ref> In 2008 a process was proposed for the removal of the peace walls.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.macaulayassociates.co.uk/pdfs/peace_wall.pdf |title="A Process for Removing Interface Barriers", Tony Macaulay, July 2008 |access-date=17 March 2009 |archive-date=6 October 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111006204650/http://www.macaulayassociates.co.uk/pdfs/peace_wall.pdf |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| {{quote|"The Northern Ireland Housing Executive, the body responsible for public housing, is taking radical steps to tackle the deep-rooted religious segregation of working-class communities. It proposes to build two housing estates that it hopes will be populated by both Catholics and Protestants. It's a laudable attempt to combat what has in the past been seen by the authorities as an insurmountable problem. Sadly, it is almost certainly doomed to fail."<ref name="SelfImposed" />}} | |||

| The effective segregation of the two communities significantly affects the usage of local services in "]s" where ] neighbourhoods adjoin. Surveys in 2005 of 9,000 residents of interface areas found that 75% refused to use the closest facilities because of location, while 82% routinely travelled to "safer" areas to access facilities even if the journey time was longer. 60% refused to shop in areas dominated by the other community, with many fearing ] by their own community if they violated an unofficial ''de facto'' boycott of their sectarian opposites.<ref name="NS" /> | |||

| ==Violence== | |||

| Cédric Gouverneur, in his article "Northern Ireland’s apartheid" for '']'', refers to a report commissionned by the ], "No longer a problem ? Sectarian violence in NI"<ref>Neil Jarman, Institute for Conflict Research, march 2005 http://www.serve.com/pfc/misc/violence.pdf</ref>, asserts that more than 1400 people have to move every year, as a consequence of ], thus building a sort of apartheid in the sense of "separate development" of communities. <ref>''Chaque année, mille quatre cents personnes doivent déménager à la suite d’intimidations pouvant aller jusqu’au meurtre (3). Ce sectarisme façonne une forme d’apartheid, au sens de « développement séparé » des communautés.'' retrieved 22 July 2007, article translated as : </ref> | |||

| ==Intermarriage== | |||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| In contrast with both the ] and most parts of ], where intermarriage between Protestants and Catholics is not unusual, in Northern Ireland it has been uncommon: from 1970 through to the 1990s, only 5 per cent of marriages were recorded as crossing community divides.<ref>Edward Moxon-Browne, 1991, "", in Peter Stringer and Gillian Robinson (eds.), 1991, Social Attitudes in Northern Ireland: The First Report, Blackstaff Press: Belfast</ref> This figure remained largely constant throughout the Troubles. It rose to between 8 and 12 per cent, according to the Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey, in 2003, 2004 and 2005.<ref>ARK, </ref><ref>ARK, </ref><ref>ARK, </ref> Attitudes towards Catholic–Protestant intermarriage have become more supportive in recent years (particularly among the middle class)<ref>{{cite web|last1=Steinfeld|first1=Jemimah|title=Northern Ireland quietly opens heart to mixed relationships|url=http://www.britishfuture.org/articles/northern-ireland-quietly-opens-heart-mixed-relationships/|publisher=British Future; ]|access-date=14 April 2015|date=16 May 2014}}</ref> and younger people are also more likely to be married to someone of a different religion to themselves than older people. However, the data does not show the considerable regional variation across Northern Ireland.<ref>Valerie Morgan, Marie Smyth, Gillian Robinson and Grace Fraser (1996), '''', Coleraine: University of Ulster</ref> | |||

| ==Anti-discrimination legislation== | |||

| In the 1970s, the British government took action to legislate against religious discrimination in Northern Ireland. The ] prohibited discrimination in the workplace on the grounds of religion and established a Fair Employment Agency. This Act was strengthened with a new ] in 1989, which introduced a duty on employers to monitor the religious composition of their workforce, and created the Fair Employment Commission to replace the Fair Employment Agency. The law was extended to cover the provision of goods, facilities and services in 1998 under the Fair Employment and Treatment (Northern Ireland) Order 1998.<ref>Equality Commission, </ref> In 1999, the Commission was merged with the Equal Opportunities Commission, the Commission for Racial Equality and the Northern Ireland Disability Council to become part of the ].<ref>Equality Commission, </ref> | |||

| An Equality Commission review in 2004 of the operation of the anti-discrimination legislation since the 1970s, found that there had been a substantial improvement in the employment profile of Catholics, most marked in the public sector but not confined to it. It said that Catholics were now well represented in managerial, professional and senior administrative posts, although there were some areas of under-representation such as local government and security but that the overall picture was a positive one. Catholics, however, were still more likely than Protestants to be unemployed and there were emerging areas of Protestant under-representation in the public sector, most notably in health and education at many levels including professional and managerial. The report also found that there had been a considerable increase in the numbers of people who work in integrated workplaces.<ref>Equality Commission for Northern Ireland (2004), ''Fair Employment in Northern Ireland: a generation on''. Belfast: Blackstaff Press. {{ISBN|0-85640-752-6}}. Summary and key findings available at . Retrieved 27 October 2009.</ref> | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| *] | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| <references/> | |||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| {{Segregation by type}} | |||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 15:44, 18 October 2024

Sociopolitical division between Irish republicans and unionists

| Part of a series on |

| Racial segregation |

|---|

|

| Overview |

Historical examples

|

| Contemporary examples |

| Related |

Segregation in Northern Ireland is a long-running issue in the political and social history of Northern Ireland. The segregation involves Northern Ireland's two main voting blocs—Irish nationalist/republicans (mainly Roman Catholic) and unionist/loyalist (mainly Protestant). It is often seen as both a cause and effect of the "Troubles".

A combination of political, religious and social differences plus the threat of intercommunal tensions and violence has led to widespread self-segregation of the two communities. Catholics and Protestants lead largely separate lives in a situation that some have dubbed "self-imposed apartheid".

Education

Education in Northern Ireland is heavily segregated. Most state schools in Northern Ireland are predominantly Protestant, while the majority of Catholic children attend schools maintained by the Catholic Church. In 2006, 90% of children in Northern Ireland were in segregated schools, by 2017 that figure had risen to 93%. The consequence is, as one commentator has put it, that "the overwhelming majority of Ulster's children can go from four to 18 without having a serious conversation with a member of a rival creed." The prevalence of segregated education has been cited as a major factor in maintaining endogamy (marriage within one's own group).

The integrated education movement has sought to reverse this trend by establishing non-denominational schools. Such schools are, however, still the exception to the general trend of segregated education. Integrated schools in Northern Ireland have been established through the voluntary efforts of parents. The churches have not been involved in the development of integrated education. However, both the Catholic Church and Protestant denominations, along with state-run institutions, have supported and organised cross-community school projects such as joint field trips, educational classes and forums wherein pupils can come together to share their beliefs, values and cultures. The academic John H. Whyte argued that "the two factors which do most to divide Protestants as a whole from Catholics as a whole are endogamy and separate education".

Employment

Historically, employment in the Northern Irish economy was highly segregated in favour of Protestants, particularly at senior levels of the public sector, in certain then-important sectors of the economy, such as shipbuilding and heavy engineering, and strategically important areas such as the police. Emigration to seek employment was therefore significantly more prevalent among the Catholic population. As a result, Northern Ireland's demography shifted further in favour of Protestants leaving their ascendancy seemingly impregnable by the late 1950s.

A 1987 survey found that 80 per cent of the work forces surveyed were described by respondents as consisting of a majority of one denomination; 20 per cent were overwhelmingly uni-denominational, with 95–100 per cent Catholic or Protestant employees. However, large organisations were much less likely to be segregated, and the level of segregation has decreased over the years.

The British government has introduced numerous laws and regulations since the mid-1990s to prohibit discrimination on religious grounds, with the Fair Employment Commission (originally the Fair Employment Agency) exercising statutory powers to investigate allegations of discriminatory practices in Northern Ireland business and organisations. This has had a significant impact on the level of segregation in the workplace; John Whyte concludes that the result is that "segregation at work is one of the least acute forms of segregation in Northern Ireland."

Housing

Public housing is overwhelmingly segregated between the two communities. Inter-communal tensions have forced substantial numbers of people to move from mixed areas into areas inhabited exclusively by one denomination, thus increasing the degree of polarisation and segregation. The extent of self-segregation grew very rapidly with the outbreak of the Troubles. In 1969, 69 per cent of Protestants and 56 per cent of Catholics lived in streets where they were in their own majority; as the result of large-scale flight from mixed areas between 1969 and 1971 following outbreaks of violence, the respective proportions had by 1972 increased to 99 per cent of Protestants and 75 per cent of Catholics. In Belfast, the 1970s were a time of rising residential segregation. It was estimated in 2004 that 92.5% of public housing in Northern Ireland was divided along religious lines, with the figure rising to 98% in Belfast. Self-segregation is a continuing process, despite the Northern Ireland peace process. It was estimated in 2005 that more than 1,400 people a year were being forced to move as a consequence of intimidation.

In response to inter-communal violence, the British Army constructed a number of high walls called "peace lines" to separate rival neighbourhoods. These have multiplied over the years and now number forty separate barriers, mostly located in Belfast. Despite the moves towards peace between Northern Ireland's political parties and most of its paramilitary groups, the construction of "peace lines" has actually increased during the ongoing peace process; the number of "peace lines" doubled in the ten years between 1995 and 2005. In 2008 a process was proposed for the removal of the peace walls.

The effective segregation of the two communities significantly affects the usage of local services in "interface areas" where sectarian neighbourhoods adjoin. Surveys in 2005 of 9,000 residents of interface areas found that 75% refused to use the closest facilities because of location, while 82% routinely travelled to "safer" areas to access facilities even if the journey time was longer. 60% refused to shop in areas dominated by the other community, with many fearing ostracism by their own community if they violated an unofficial de facto boycott of their sectarian opposites.

Intermarriage

In contrast with both the Republic of Ireland and most parts of Great Britain, where intermarriage between Protestants and Catholics is not unusual, in Northern Ireland it has been uncommon: from 1970 through to the 1990s, only 5 per cent of marriages were recorded as crossing community divides. This figure remained largely constant throughout the Troubles. It rose to between 8 and 12 per cent, according to the Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey, in 2003, 2004 and 2005. Attitudes towards Catholic–Protestant intermarriage have become more supportive in recent years (particularly among the middle class) and younger people are also more likely to be married to someone of a different religion to themselves than older people. However, the data does not show the considerable regional variation across Northern Ireland.

Anti-discrimination legislation

In the 1970s, the British government took action to legislate against religious discrimination in Northern Ireland. The Fair Employment Act 1976 prohibited discrimination in the workplace on the grounds of religion and established a Fair Employment Agency. This Act was strengthened with a new Fair Employment Act in 1989, which introduced a duty on employers to monitor the religious composition of their workforce, and created the Fair Employment Commission to replace the Fair Employment Agency. The law was extended to cover the provision of goods, facilities and services in 1998 under the Fair Employment and Treatment (Northern Ireland) Order 1998. In 1999, the Commission was merged with the Equal Opportunities Commission, the Commission for Racial Equality and the Northern Ireland Disability Council to become part of the Equality Commission for Northern Ireland.

An Equality Commission review in 2004 of the operation of the anti-discrimination legislation since the 1970s, found that there had been a substantial improvement in the employment profile of Catholics, most marked in the public sector but not confined to it. It said that Catholics were now well represented in managerial, professional and senior administrative posts, although there were some areas of under-representation such as local government and security but that the overall picture was a positive one. Catholics, however, were still more likely than Protestants to be unemployed and there were emerging areas of Protestant under-representation in the public sector, most notably in health and education at many levels including professional and managerial. The report also found that there had been a considerable increase in the numbers of people who work in integrated workplaces.

References

- ^ "Self-imposed Apartheid", by Mary O'Hara, published in The Guardian on Wednesday 14 April 2004. Accessed on Sunday, 22 July 2007.

- Lord Baker of Dorking, Daily Hansard, 18 July 2006 : Column 1189 www.parliament.uk, retrieved 22 July 2007

- "The Growth of Integrated Education since the Good Friday Agreement". Integrated Education Northern Ireland. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- "Stop this Drift into Educational Apartheid", by Nick Cohen. Published in The Guardian on Sunday 13 May 2007. Accessed on 22 July 2007.

- Michael P. Hornsby-Smith, Roman Catholics in England: Studies in Social Structure since the Second World War. Cambridge University Press, 1987. ISBN 0-521-30313-3

- "Churches and Christian Ethos in Integrated Schools", Macaulay,T 2009

- "Cross-community school project launched". Belfasttelegraph.

- "Publications Overview | ARK - Access Research Knowledge" (PDF).

- John Whyte (1990) Interpreting Northern Ireland, Oxford: Clarendon Press, p. 48

- ^ "Northern Ireland," Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2007

- ^ Claire Mitchell, Religion, Identity And Politics in Northern Ireland: Boundaries of Belonging and Belief, p. 63. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd, 2006. ISBN 0-7546-4155-4

- John Whyte, Interpreting Northern Ireland, p. 37. Clarendon Press, 1990. ISBN 0-19-827848-9

- Frank Wright, Northern Ireland: A Comparative Analysis, p. 205. Rowman & Littlefield, 1988. ISBN 0-7171-1428-7

- Paul Doherty and Michael A. Poole (1997) Ethnic residential segregation in Belfast, Northern Ireland, 1971–1991, Geographical Review 87(4), pp. 520–536

- Neil Jarman, Institute for Conflict Research, March 2005 http://www.serve.com/pfc/misc/violence.pdf

- ^ New Statesman, 28 November 2005, newstatesman.com retrieved 22 July 2007

- ""A Process for Removing Interface Barriers", Tony Macaulay, July 2008" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- Edward Moxon-Browne, 1991, "National Identity in Northern Ireland", in Peter Stringer and Gillian Robinson (eds.), 1991, Social Attitudes in Northern Ireland: The First Report, Blackstaff Press: Belfast

- ARK, If married or living as married...Is your husband/wife/partner the same religion as you? 2003

- ARK, If married or living as married...Is your husband/wife/partner the same religion as you? 2004

- ARK, If married or living as married...Is your husband/wife/partner the same religion as you? 2005

- Steinfeld, Jemimah (16 May 2014). "Northern Ireland quietly opens heart to mixed relationships". British Future; The Huffington Post. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- Valerie Morgan, Marie Smyth, Gillian Robinson and Grace Fraser (1996), Mixed Marriages in Northern Ireland, Coleraine: University of Ulster

- Equality Commission, http://www.equalityni.org/sections/default.asp?secid=2&cms=Your+Rights_Fair+employment+%26+treatment&cmsid=2_56&id=56

- Equality Commission, Anti-discrimination law in N Ireland – a brief chronology

- Equality Commission for Northern Ireland (2004), Fair Employment in Northern Ireland: a generation on. Belfast: Blackstaff Press. ISBN 0-85640-752-6. Summary and key findings available at Equality Commission. Retrieved 27 October 2009.

| Segregation in countries by type (in some countries, categories overlap) | |

|---|---|

| Religious | |

| Ethnic and racial | |

| Gender | |

| Dynamics | |

| Related topics |

|