| Revision as of 00:16, 6 September 2007 editMuzikJunky (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users31,086 edits →''Genetic variability of the African people''← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 00:33, 11 November 2024 edit undoPhilotam (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users12,342 editsNo edit summary | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Senegalese politician, historian and scientist (1923–1986)}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Infobox person | |||

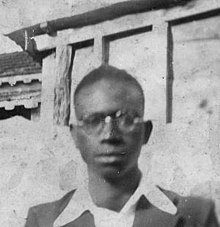

| | name = Cheikh Anta Diop | |||

| | image = Cheikh Anta Diop, late 1940s.jpg | |||

| | image_size = | |||

| | caption = Diop as a university student in Paris<br>in the late 1940s | |||

| | birth_name = Seex Anta Jóob (<small>in ]</small>) | |||

| | birth_date = {{birth date|1923|12|29|df=y}} | |||

| | birth_place = ], ] | |||

| | death_date = {{Death date and age|1986|02|07|1923|12|23|df=y}} | |||

| | death_place = ] | |||

| | nationality = Senegalese | |||

| | occupation = ], ], ], ] | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Cheikh Anta Diop''' (29 December 1923 – 7 February 1986) was a ]ese ], ], ], and ] who studied the human race's origins and pre-] ].<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195337709.001.0001/acref-9780195337709-e-1230|title=Encyclopedia of Africa|publisher=University of Oxford Press|year=2010|isbn=978-0-19-533770-9|editor-last=Gates|editor-first=Henry Louis Jr.|chapter=Diop, Cheikh Anta|editor-last2=Appiah|editor-first2=Kwame Anthony}}</ref> Diop's work is considered foundational to the theory of ], though he himself never described himself as an Afrocentrist.<ref>Molefi Kete Asante, "Cheikh Anta Diop: An Intellectual Portrait" (Univ of Sankore Press: December 30, 2007)</ref> The questions he posed about ] in scientific research contributed greatly to the ] turn in the study of ].<ref>{{Cite book|last1=Nyamnjoh|first1=Francis B.|title=The Postcolonial Turn: Re-Imagining Anthropology and Africa|last2=Devisch|first2=René|publisher=Langaa|year=2011|isbn=978-9956-726-81-3|location=Leiden|page=17}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Gwiyani-Nkhoma|first=Bryson|date=2006|title=Towards an African historical thought: Cheikh Anta Diop's contribution|url=https://www.ajol.info/index.php/jh/article/view/153377|journal=Journal of Humanities|volume=20|issue=1 |pages=107–123}}</ref><ref>{{Citation |last=Dunstan |first=Sarah C. |title=Cheikh Anta Diop's Recovery of Egypt: African History as Anticolonial Practice |date=2023 |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/anticolonial-transnational/cheikh-anta-diops-recovery-of-egypt-african-history-as-anticolonial-practice/BB24C24DEEF124E737EF775D989C53F4 |work=The Anticolonial Transnational: Imaginaries, Mobilities, and Networks in the Struggle against Empire |pages=135–161 |editor-last=Manela |editor-first=Erez |publisher=Cambridge University Press |doi=10.1017/9781009359115.009 |isbn=978-1-009-35912-2 |editor2-last=Streets-Salter |editor2-first=Heather}}</ref> | |||

| '''Cheikh Anta Diop''' (], ]–], ]) is a ]ese ], ], which places emphasis on the human race's origins and on the study of pre-] African ] and its connectedness to the rest of the peoples of the world. He has been considered one of the greatest African historians of the ] by some, and a racialist scientist by others. On ] ], Diop, who by now was regarded by many as the modern pharaoh of African studies, died in his sleep in ]. Diop was survived by a wife and three sons. | |||

| Diop argued that there was a shared cultural continuity across African people that was more important than the varied development of different ethnic groups shown by differences among languages and cultures over time.<ref name="Cheikh, Anta Diop 1963 pp. 53">Cheikh, Anta Diop, ''The Cultural Unity of Negro Africa'' (Paris: Présence Africaine, 1963), English translation: ''The Cultural Unity of Black Africa: The Domains of Patriarchy and of Matriarchy in Classical Antiquity'' (London: Karnak House: 1989), pp. 53–111.</ref> Some of his ideas have been criticized as based upon outdated sources and an outdated conception of ].<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":0" /> Other scholars have defended his work from what they see as widespread misrepresentation.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Walker|first1=J. D.|date=1995|title=The Misrepresentation of Diop's Views|journal=Journal of Black Studies|volume=26|issue=1|pages=77–85|doi=10.1177/002193479502600106|jstor=2784711|s2cid=144667194|issn=0021-9347}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=MOITT|first1=Bernard|date=1989|title=Cheikh Anta Diop and the African Diaspora: Historical Continuity And Socio-Cultural Symbolism|journal=Présence Africaine|volume=149-150|issue=149/150|pages=347–360|doi=10.3917/presa.149.0347|jstor=24351996|issn=0032-7638}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Verharen |first1=Charles C. |date=1997 |title=In and Out of Africa Misreading Afrocentrism |journal=Présence Africaine |volume=156 |issue=2 |pages=163–185 |doi=10.3917/presa.156.0163 |issn=0032-7638 |jstor=24351662}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Momoh|first1=Abubakar|date=2003|title=Does Pan-Africanism Have a Future in Africa? In Search of the Ideational Basis of Afro-Pessimism|journal=African Journal of Political Science / Revue Africaine de Science Politique|volume=8|issue=1|pages=31–57|jstor=23493340|issn=1027-0353}}</ref> | |||

| ==Early Life and Career== | |||

| {{Pan-African|left}} | |||

| Cheikh Anta Diop was born in ], ]. His early education was in a traditional Islamic School. At the age of 23, he went to ] in 1946 to become a physicist. He remained there for 15 years, studying physics under ], ]’s son-in-law, and ultimately translating parts of ]’s ] into his native Wolof. In the ], the study of African history was dominated by ]s who considered Africans people without a past. Diop also mastered studies of African history, Egyptology, linguistics, anthropology, economics, and sociology as he armed himself for the task of setting the historical record straight. | |||

| ] (formerly known as the University of Dakar), in ], is named after him.<ref name="blackpast.org">Touré, Maelenn-Kégni, , BlackPast.org.</ref><ref name="University Cheikh Anta Diop">, Encyclopædia Britannica.</ref> | |||

| == Research == | |||

| In ], Diop submitted a ] ] at the ] where he argued that ] had in fact been a Black African culture. The thesis was rejected, but over the next nine years, Diop reworked the thesis, adding stronger evidentiary support, and in ], he succeeded in the defense of his thesis and was awarded the Ph.D. degree. Five years earlier, the thesis had been published in the popular press as a book titled ''Nations nègres et culture'' (''Negro Nations and Culture''), proving very successful and making him one of the most controversial historians of his time. He eventually earned 5 PhDs. | |||

| ==Early life== | |||

| After ], Diop went back to Senegal and continued writing. A ] laboratory was established with the University of ] (which was later named ] of Dakar after his death), and Diop was made its head. He had said, “In practice it is possible to determine directly the skin color and, hence, the ethnic affiliations of the ancient Egyptians by microscopic analysis in the laboratory; I doubt if the sagacity of the researchers who have studied the question has overlooked the possibility.” One of his important works published in journals is the dosage test—a technique developed by Diop to determine the melanin content of the Egyptian mummies. This technique was later adopted by forensic investigators to determine the "racial identity" of badly burnt accident victims.<ref> - Free Speech Mauritania (2006)</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Born in Thieytou, ], ], Diop belonged to an aristocratic ] ] family in ] where he was educated in a traditional Islamic school. Diop's family was part of the ] brotherhood, the only independent Muslim fraternity in Africa according to Diop.<ref name=Ajayi>S. Ademola Ajayi, "Cheikh Anta Diop" in Kevin Shillington (ed.), ''Encyclopedia of African History''.</ref> He obtained the colonial equivalent of the metropolitan French ] in Senegal before moving to Paris to study for a degree.<ref name="cheikhantadiop.net">{{cite web|url=http://www.cheikhantadiop.net/cheikh_anta_diop_biograph.htm |title=ANKH: Egyptologie et Civilisations Africaines |website=Cheikhantadiop.net |access-date=2017-05-31}}</ref> | |||

| ==Studies in Paris== | |||

| In ], Cheikh Anta Diop participated in a ] symposium in ], where he presented his theories to other specialists in Egyptology. He also wrote the chapter about the origins of the ] in the UNESCO ''General History of Africa''. | |||

| In 1946, at the age of 23, Diop went to Paris to study. He initially enrolled to study higher mathematics{{Citation needed|date=February 2023}}, but then enrolled to study philosophy {{Citation needed|date=February 2023}} in the Faculty of Arts of the ]. He gained his first degree (licence) in philosophy in 1948{{Citation needed|date=February 2023}}, then enrolled in the Faculty of Sciences, receiving two diplomas in chemistry in 1950{{Citation needed|date=February 2023}}. | |||

| In 1948 Diop edited with ], a professor of art history{{Citation needed|date=February 2023}}, a special edition of the journal ''Musée vivant''{{Citation needed|date=February 2023}}, published by the Association populaire des amis des musées (APAM). APAM had been set up in 1936 by people on the political left wing to bring culture to wider audiences{{Citation needed|date=February 2023}}. The special edition of the journal was on the occasion of the centenary of the abolition of slavery in the French colonies and aimed to present an overview of issues in contemporary African culture and society. Diop contributed an article to the journal: "Quand pourra-t-on parler d'une renaissance africaine" (When we will be able to speak of an African Renaissance?). He examined various fields of artistic creation, with a discussion of African languages, which, he said, would be the sources of regeneration in African culture. He proposed that African culture should be rebuilt on the basis of ancient Egypt, in the same way that European culture was built upon the legacies of ancient Greece and Rome.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Danielle Maurice|title=Le musée vivant et le centenaire de l'abolition de l'esclavage: pour une reconnaissance des cultures africaines|journal=Conserveries Mémorielles. Revue Transdisciplinaire|date=June 2007|issue=#3|publisher=Conserveries mémorielles, revue transdisciplinaire de jeunes chercheurs|url=http://cm.revues.org/127|access-date=2017-05-31}}</ref> | |||

| ==Life works== | |||

| In 1949, Diop registered a proposed title for a Doctor of Letters thesis, "The Cultural Future of African thought," under the direction of Professor ] {{Citation needed|date=February 2023}}. In 1951 he registered a second thesis title "Who were the pre-dynastic Egyptians" under Professor ]{{Citation needed|date=February 2023}}. | |||

| Diop's first work translated into ], ''The African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality'', was published in 1974, revealing his views to a much greater audience. In this work, he claimed that ] and ] evidence supports his Afrocentric view of the ]s being of ] origin. While many scholars draw heavily from his groundbreaking work, the Western academic world as a whole does not accept Diop's theories. However, they continue to raise important questions about the cultural bias inherent in scientific research. | |||

| In 1953, he first met ], ]'s son-in-law {{Citation needed|date=February 2023}}, and in 1957 Diop began specializing in nuclear physics {{Citation needed|date=February 2023}} at the Laboratory of Nuclear Chemistry of the College de France which Frederic Joliot-Curie ran until his death in 1958 {{Citation needed|date=February 2023}}, and the ] in Paris. He ultimately translated parts of ]'s ] into his native ].{{Citation needed|date=February 2023}} | |||

| The very latest discoveries by the Swiss archaeologist Charles Bonnet at the site of ] shed some light on the theories of Diop.{{Fact|date=August 2007}} Even if the Afrocentric view may be as flawed as another race-centric view, and even if there are many mistakes in the work of Diop, one has to acknowledge the core of its oeuvre—that European archaeologists before and after the Decolonization have understated and continue to understate the extent and possibility of Black civilizations. | |||

| According to Diop's own account, his education in Paris included ], ], ], ], ], ], and ].<ref name="John G 2001 pp. 13-175">John G. Jackson and Runoko Rashidi, Introduction To African Civilizations (Citadel: 2001), {{ISBN|978-0-8065-2189-3}}, pp. 13–175.</ref><ref>Chris Gray, ''Conceptions of History in the Works of Cheikh Anta Diop and Theophile Obenga'' (Karnak House:1989) 11-155,</ref> In Paris, Diop studied under ] {{Citation needed|date=February 2023}}, professor of History and later Dean of the Faculty of Letters at the University of Paris and he said that he had "gained an understanding of the Greco-Latin world as a student of ], ], ], and others".<ref>Diop, C. A., ''The African Origin of Civilization—Myth or Reality'': Chicago, IL: Lawrence Hill Books, 1974. pp. ix.</ref> | |||

| The European Africanists schools (all tendencies mixed) were unanimous in rejecting, more often without examining, the fundamental theses of Cheikh Anta Diop relating to the cultural unity of Africa to the migrations that, taking their source from the original Neolithic basin, had ended up in the present peopling of the continent to the continuity of the national historical past of Africans. | |||

| In his 1954 thesis, Diop argued that ancient Egypt had been populated by Black people. He specified that he used the terms "negro", "black", "white" and "race" as "immediate givens" in the ]ian sense, and went on to suggest operational definitions of these terms.<ref>''Bulletin de l'IFAN'', Vol. XXIV, pp. 3–4, 1962.</ref> He said that the Egyptian language and culture had later been spread to ]. When he published many of his ideas as the book ''Nations nègres et culture'' (''Negro Nations and Culture''), it made him one of the most controversial historians of his time. | |||

| ==Assessment of Diop's thought== | |||

| In 1956 he re-registered a new proposed thesis for Doctor of Letters with the title "The areas of matriarchy and patriarchy in ancient times." From 1956, he taught physics and chemistry in two Paris lycees as an assistant master, before moving to the College de France. In 1957 he registered his new thesis title "Comparative study of political and social systems of Europe and Africa, from Antiquity to the formation of modern states." The new topics did not relate to ancient Egypt but were concerned with the forms of organisation of African and European societies and how they evolved. He obtained his doctorate in 1960.<ref name="cheikhantadiop.net" /> | |||

| Diop's thought has remained controversial in a number of places as noted above, nevertheless over 20 years after his death in 1986, it is possible to see some movement (if not always agreement) in the academy closer to many of his ideas. This convergence is summarized below. | |||

| ===''Biased scholarship on Africa''=== | |||

| == Career == | |||

| Diop's charges on this point have largely proven true. When he wrote in the 1950s, 1960s and somewhat in the early 1970s, the field of African scholarship was heavily influenced by racial analysis epitomized in the works of ] who used racial rankings of inferiority and superiority, narrow definitions of true Blacks, and allocation of various Africans with advanced cultures to Caucasian clusters.<ref>Carelton Coon, "Races of Mankind, 1962</ref> Coon's work was mirrored in the ''Hamitic Hypothesis'', which held that most advanced progress or cultural development was due to the invasions of mysterious Caucasoid Hamites, and the ] of Egypt, which asserted that a mass migration of Caucasoid peoples were needed to create the Egyptian kingships—slower-witted Negro tribes being unable to do the job. All these theories and approaches have since been discredited by modern physical anthropologists,<ref> Philip L Stein and Bruce M Rowe, Physical Anthropology, (McGraw-Hill, 2002, pp. 54-166</ref> and linguists such as ]. Diop's early condemnation of this bias in his 1954 work ''Nations Negres et Culture,''<ref>Chiek Anta Diop, Nations Negres et Culture,</ref> has thus been supported by later scholarship. | |||

| Diop served as a member of the UNESCO International Scientific Committee for the Drafting of a General History of Africa in 1971 and wrote the opening chapter about the origins of the ancient Egyptians in the UNESCO General History of Africa.<ref name="J. Currey">{{cite book|title=General History of Africa volume 2: Ancient Civilizations of Africa: Ancient Civilizations of Africa Vol 2 (Unesco General History of Africa|date=1990|publisher=J. Currey|isbn=978-0-85255-092-2|edition=Abridged|location=London |pages=15–32}}</ref> In this chapter, he presented anthropological and historical evidence in support of his hypothesis that Ancient Egyptians had a close genetic affinity with Sub-Saharan African ethnic groups, including a shared B blood group between modern Egyptians and West Africans, "negroid"<ref name="J. Currey"/> bodily proportions in ancient Egyptian art and mummies, microscopic analysis of melanin levels in mummies from the laboratory of the Musée de L'Homme in Paris, primary accounts of Greek historians, and shared cultural linkages between Egypt and Africa in areas of totemism and cosmology.<ref name="J. Currey"/> At the symposium Diop's conclusions were met with an array of responses, from strong objections to enthusiastic support.<ref>{{cite book|title=General History of Africa volume 2: Ancient Civilizations of Africa: Ancient Civilizations of Africa Vol 2 (Unesco General History of Africa|date=1990|publisher=J. Currey|isbn=978-0-85255-092-2|edition=Abridged|location=London |pages=32–55}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=Ancient civilizations of Africa|date=1990|publisher=J. Currey|isbn=978-0-85255-092-2|edition=Abridged|location=London |pages=31–55}}</ref> | |||

| ==Reception== | |||

| ===''Genetic variability of the African people''=== | |||

| Diop's work has been both extensively praised and extensively criticized by a variety of scholars.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Gwiyani-Nkhoma |first1=Bryson |title=Towards an African historical thought: Cheikh Anta Diop's contribution |journal=Journal of Humanities |date=2006 |volume=20 |issue=1 |pages=107–123 |doi=10.4314/jh.v20i1 |doi-broken-date=1 November 2024 |url=https://www.ajol.info/index.php/jh/article/view/153377 |language=en |issn=1016-0728}}</ref> | |||

| Diop consistently held that Africans could not be pigeonholed into a rigid type somewhere south of the Sahara, but varied widely in skin color, facial shape, hair type, height, and a number of additional factors, just like other normal human populations. In his ''Evolution of the Negro world'' in Presence Africaine (1964), Diop castigates European scholars who posited a separate evolution of various types of humankind, and denied the African origin of ''homo sapiens''. | |||

| {Cqotr\e|But it is only the most gratuitous theory that considers the Dinka, the Nouer and the Masai, among others, to be Caucasoids. What if an African ethnologist were to persist in recognizing as white-only the blond, blue-eyed Scandinavians, and systematically refused membership to the remaining Europeans, and Mediterraneans in particular—the French, Italians, Greek, Spanish, and Portuguese? Just as the inhabitants of Scandinavia and the Mediterranean countries must be considered as two extreme poles of the same anthropological reality, so should the Negroes of East and West Africa be considered as the two extremes in the reality of the Negro world. To say that a Shillouk, a Dinka, or a Nouer is a Caucasoid is for an African as devoid of sense and scientific interest as would be, to a European, an attitude that maintained that a Greek or a Latin were not of the same race.}<ref>Evolution of the Negro world' in Presence Africaine (1964)</ref> | |||

| Decades later, Diop's work on this point is supported by a number of scholars mapping human genes using modern DNA analysis, which shows that most of human genetic variation (some 85–90%) occurs within localized population groups, and that race only can account for 6–10% of the variation. Arbitrarily classifying Masai, Ethiopians, Shillouk, Nubians, etc., as Caucasian is thus problematic, since all these peoples are northeast African populations and show normal variation well within the 85–90% specified by DNA analysis.<ref>Patterns of Human Diversity, within and among Continents, Inferred from Biallelic DNA Polymorphisms, Barbujani, et al, (Geonome Research, Vol. 12, Issue 4, pp. 602-612), April 2002</ref> Modern physical anthropologists also question splitting of peoples into racial zones, holding that such splitting is arbitrary insertion of data into pre-determined pigeonholes and the selective grouping of samples.<ref>Leiberman and Jackson 1995 "Race and Three Models of Human Origins" in American Anthropologist 97(2) pp. 231-242</ref> Diop's objections to how data on African peoples is being manipulated is thus reflected in the work of several modern scholars, using modern DNA analysis. | |||

| ===Positive reception=== | |||

| ===''Egypt within the African context''=== | |||

| African-American historian ] called Diop "one of the greatest historians to emerge in the African world in the twentieth century", noting that his theoretical approach derived from various disciplines, including the "hard sciences". Clarke further added that his work, ''The African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality'', challenged contemporary attitudes "about the place of African people in scholarly circles around the world" and relied upon "], ] and ] evidence to support his thesis". He later summarised that Diop contributed to a new "concept of African history" among African and African-American historians.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=CLARKE|first1=John Henrik|date=1989|title=The Historical Legacy of Cheikh Anta Diop: His Contributions To A New Concept of African History|journal=Présence Africaine|volume=149-150|issue=149/150|pages=110–120|doi=10.3917/presa.149.0110|jstor=24351980|issn=0032-7638}}</ref> | |||

| Diop's arguments placing Egypt in the cultural and genetic context of Africa was met with near universal condemnation and rejection when he first proposed them. Nevertheless, towards the 1980s, a number of mainstream scholars had moved closer to his position. Scholars like ] condemned the often shaky scholarship on northeast African peoples like the Egyptians, declaring that the peoples of the region were all Africans, and decrying the "bizarre and dangerous myths" of previously biased scholarship, "marred by a confusion of race, language, and culture and by an accompanying racism."<ref>Bruce Trigger, 'Nubian, Negro, Black, Nilotic?', in Sylvia Hochfield and Elizabeth Riefstahl (eds), Africa in Antiquity: the arts of Nubia and the Sudan, Vol. 1 (New York, Brooklyn Museum, 1978). | |||

| </ref> Trigger's approach has been seconded by Egyptologist Frank Yurco, who sees the Egyptians, Nubians, Ethiopians, Somalians, etc as one localized Nile valley population, that need not be arbitrarily split into racial clusters.<ref>Frank Yurco, "An Egyptological Review", 1996 -in Mary R. Lefkowitz and Guy MacLean Rogers, Black Athena Revisited, 1996, The University of North Carolina Press, pp. 62-100</ref> Re-analyses of the work of other researchers such as Czech anthropologist E. Strouhal, demonstrate a number of cultural and material linkages between Egypt and the Saharan and Sudanic African cultures to the south.<ref> Strouhal, E., 1971, ‘Evidence of the early penetration of Negroes into prehistoric Egypt’, Journal of African History, 12: 1-9)</ref> | |||

| S.O.Y. Keita (né J.D. Walker), a ], contended that "his views, or some of them, have been seriously misrepresented" and he argued that there was ], anthropological and archaeological evidence which supported the views of Diop. The author also stated "Diop, though he did not express it clearly, thought in terms of biogeography and biohistory for his definitions. He also defined populations in an ethnic or ethnogeographical fashion. Nile Valley populations absorbed "foreign genes", but this did not change their Africanity".<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Walker |first1=J. D. |title=The Misrepresentation of Diop's Views |journal=Journal of Black Studies |date=1995 |volume=26 |issue=1 |pages=77–85 |doi=10.1177/002193479502600106 |jstor=2784711 |s2cid=144667194 |issn=0021-9347}}</ref> | |||

| ===''The Egyptians as a Black population''=== | |||

| This is one of Diop's most controversial claims chiefly centering around the definition of who is a true Black person. Diop insisted on a broad interpretation similar to that used with European populations, and accused his opponents of using the narrowest possible definition of "Blacks" in order to separate out various African groups like Nubians into a European or Caucasoid racial zone. Under the "true negro" approach, all else not meeting the stereotypical classification is attributed to mixture with outside sources, or split off and assigned to Caucasoid clusters. He also claimed hypocrisy in that opponents dismissed the race of the Egyptians as unimportant, but on the other hand, did not hesitate to introduce race under new guises, such as the use of terminology like "Mediterranean" or "Middle Eastern," or statistical classification of all not meeting the "true" Black stereotype as some other race. Diop's meticulous preparation and fierce defense of his concepts at the Cairo UNESCO symposium on "The peopling of ancient Egypt and the deciphering of the Meroitic script," in 1974, exposed the inconsistencies and contradictions in how African data was handled. This exposure remains a hallmark of Diop's contribution. As one scholar at the 1974 symposium put it: | |||

| ::"While acknowledging that the ancient Egyptian population was mixed, a fact confirmed by all the anthropological analyses, writers nevertheless speak of an Egyptian race, linking it to a well-defined human type, the white, Hamitic branch, also called Caucasoid, Mediterranean, Europid or Eurafricanid. There is a contradiction here: all the anthropologists agree in stressing the sizable proportion of the Negroid element—almost a third and sometimes more—in the ethnic mixture of the ancient Egyptian population, but nobody has yet defined what is meant by the term 'Negroid', nor has any explanation been proffered as to how this Negroid element, by mingling with a Mediterranean component often present in smaller proportions, could be assimilated into a purely Caucasoid race."<ref>(24) Jean Vercoutter at the 1974 UNESCO conference. Quoted in Shomarka Keita, 'Communications', American Historical Review (October 1992), pp. 1355-6.</ref> | |||

| ], Egyptologist and professor of anthropology at ] regarded his work, ''The African Origin of Civilization'', published in 1974 as "A highly influential work that rightly points out the African origins of Egyptian civilization, but reinforces the methodological and theoretical foundations of colonialist theories of history, embracing racialist thinking and simply reversing the flow of diffusionist models".<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |author=Smith, Stuart Tyson |entry=Race |title=Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt |volume=3 |page=115 |entry-url=https://archive.org/details/oxfordencyclopediaofancientegyptvolume3/page/n121/mode/2up |date=2001}}</ref> | |||

| :A majority of academics disavow the term ''black'' for the Egyptians but there is no consensus on substitute terminology.<ref> Frank M. Snowden, Jr., 'Bernal's "Blacks," Herodotus, and the other classical evidence', Arethusa (Vol. 22, 1989); Before Colour Prejudice: the ancient view of blacks (Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 1983)</ref> Some modern studies use DNA to define racial classifications, while others condemn this practice as selective filling of pre-defined, stereotypical categories.<ref>Human Races: A Genetic and Evolutionary Perspective, Alan R. Templeton. American Anthropologist, 1998, 100:632-650; The Persistence of Racial Thinking and the Myth of Racial Divergence, S. O. Y. Keita, Rick A. Kittles, American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 99, No. 3 (Sep., 1997), pp. 534-544</ref> | |||

| :Diop's concept was of a fundamentally Black population that incorporated new elements over time, rather than mixed-race populations crossing arbitrarily assigned racial zones. Many academics reject the term ''black'', however, or use it in the sense of a sub-Saharan type but as was previously noted, there is no consensus on substitute terminology. One approach that has bridged the gap between Diop and his critics is the non-racial bio-evolutionary approach. This approach is associated with scholars who question the validity of race as a biological concept. This view sees the Egyptians as (a) simply another Nile valley population or (b) part of a continuum of population gradation or variation among humans that is based on indigenous development rather than use racial clusters or the concept of admixtures.<ref><Apportionment of Racial Diversity: A Review, Ryan A. Brown and George J. Armelagos, 2001, Evolutionary Anthropology, 10:34-40 Web file:http://www.as.ua.edu/ant/bindon/ant275/reader/apportionment.pdf</ref> Under this approach, racial categories such as "Blacks" or "Caucasoids" are discarded in favor of localized populations showing a range of physical variation. This way of viewing the data rejects Diop's insistence on Blackness, but at the same time acknowledges the inconsistency with which data on African peoples are manipulated and categorized. | |||

| Guyanese educator and novelist ] credits Diop as a "unique unifier" in countering the "built-in prejudices of the scholars of his time" and presenting a more comprehensive view of African historical development.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=DATHORNE|first1=O.R.|date=1989|title=Africa as Ancestor: Diop as Unifier|journal=Présence Africaine|volume=149-150|issue=149/150|pages=121–133|doi=10.3917/presa.149.0121|jstor=24351981|issn=0032-7638}}</ref> | |||

| ===''The influence of Egypt''=== | |||

| Diop never asserted, as some claim, that all of Africa follows an Egyptian cultural model. Instead he claims Egypt as an influential part of a "southern cradle" of civilization, an indigeous development based on the Nile Valley. While Diop holds that the Greeks learned from a superior Egyptian civilization, he does not argue that Greek culture is simply a derivative of Egypt. Instead he views the Greeks as forming part of a "northern cradle", distinctively growing out of certain climatic and cultural conditions.<ref>Diop, op. cit</ref> His thought is thus not the "Stolen Legacy" argument of writers like ] or the "Black Athena" notions of ]. Diop focuses on Africa, not Greece, contrary to the preoccupation of other Afrocentrists. Writers such as ] and ] have argued that it is dubious to assign the complexity of Greek culture in any significant way to Egypt.<ref>Mary Lefkotitz, Not Out of Africa</ref> It should be noted however that Diop made few such claims. | |||

| ], a Kenyan historian and editor of UNESCO ] Volume 5, stated that "Cheikh Anta Diop wrested Egyptian civilization from the Egyptologists and restored it to the mainstream of African history".<ref>{{cite book |last1=Ogot |first1=Bethwell |title=AFRICAN Historiography: From colonial historiography to UNESCO's general history of Africa |date=2011 |page=72 |s2cid=55617551 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ===Cultural unity of African peoples as part of a "southern cradle=== | |||

| Diop attempted to demonstrate that the African peoples shared certain commonalities, including language roots and other cultural elements like regicide, circumcision, totems, etc. These he held, formed part of a tapestry that laid the basis for African cultural unity, that could assist in throwing off colonialism. His cultural theory attempted to show that Egypt was part of the African environment as opposed to incorporating it into Mediterranean or Middle Eastern venues. These concepts are laid out in Diop's "TOWARDS THE AFRICAN RENAISSANCE: ESSAYS IN CULTURE AND DEVELOPMENT, 1946-1960."<ref>"TOWARDS THE AFRICAN RENAISSANCE: ESSAYS IN CULTURE AND DEVELOPMENT, 1946-1960." Trans. Egbuna P. Modum. London: The Estate of Cheikh Anta Diop and Karnak House, 1996.</ref> | |||

| Esperanza Brizuela Garcia, professor of history, wrote that he "was most persuasive among intellectuals of African descent in the diaspora" and among Afrocentric scholars who had criticised the omission of Africa in the works of world historians. Garcia also added that his work, ''The'' ''African Origin of Civilization'', best represented "Afrocentric critique" but "it does so without a serious engagement with the diversity and complexity of the African experience and offers only a limited challenge to the Eurocentric values it aims to dislodge".<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Brizuela-Garcia |first1=Esperanza |title=Africa in the World: History and Historiography |journal=Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History |date=20 November 2018 |doi=10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.296 |isbn=978-0-19-027773-4 |url=https://oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277734-e-296 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Most anthropologists see commonalities in African culture but only in a very broad, generic sense, intimately linked with economic systems, etc. There are common patterns such as circumcision, matriarchy etc, but whether these are part of a unique "Southern cradle" of peoples, versus the more grasping, patriarchal flavored "Northern cradle" are deemed problematic. Many cultures the world over show similar developments.<ref>Philip L Stein and Bruce M Rowe, Physical Anthropology, (McGraw-Hill, 2002, pp. 54-326</ref> | |||

| ], a Nigerian historian, called Diop's work "passionate, combative, and revisionist" and "demonstrated the black origins of Egyptian civilisation" in his view.<ref>{{cite book|author=]| year= 2004|title=Nationalism and African Intellectuals|publisher=University Rochester Press|page=224}}</ref> | |||

| ===Languages demonstrating African cultural unity=== | |||

| Diop rejected "white civilizer" theories, such as that advanced by researcher Carl Meinhof, which held that an influx of Caucasoid or "Hamitic" speaking peoples entered Africa to dominate slower- witted negro tribes. More careful race-neutral scholarship after WWII, such as that of Greenberg, et al. largely supports Diop's rejection of the white civilizer approach.<ref>Joseph H. Greenberg, The Languages of Africa. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1966)</ref><ref>Russell G. Schuh, "The Use and Misuse of language in the study of African history" (1997), in: Ufahamu 25(1):36-81</ref> | |||

| Firinne Ni Chreachain, an academic in African literature, described him as "one of the most profoundly revolutionary thinkers francophone Africa had produced" in the twentieth century and his radio-carbon techniques had "enabled him to prove, on the contrary to the claims of European Egyptologists, many of the ruling class of ancient Egypt whose achievements Europeans revered had been black Africans".<ref>{{cite book |last1=France |first1=Peter |title=The new Oxford companion to literature in French |date=1995 |publisher=Clarendon Press |location=Oxford |isbn=978-0-19-866125-2 |page=248}}</ref> | |||

| Diop further argued that the languages of Nile Valley peoples also demonstrated a broad commonality and unity organic to African peoples and attempted to demonstrate relationships between Ancient Egyptian, modern Coptic of Egypt and Wolof, a Senegalese language of West Africa, with the latter two having their origin in the former ''(Diop: Parenté génétique de l’egyptien pharaonique et des langues négro-africaines)''.<ref>Diop, C. A. 1977. Parenté génétique de l’egyptien pharaonique et des langues négro-africaines. Dakar: Les Nouvelles Éditions Africaines)</ref> Diop's work has been further expanded by Afrocentric scholar Ivan Van Sertima.<ref>Ivan van Sertima, Egypt Revisited, Transaction Publishers: 1989, ISBN 0887387993</ref> | |||

| Helen Tilley, Associate professor of history at ], noted that the academic debates over "''The African Origin of Civilizations''" still continued but that the "more general points that Cheikh Anta Diop" sought to establish "have become commonplace" and "no one should assume a pure lineage" can be attributed to "any intellectual genealogy because entanglements, appropriations, mutations and dislocations have been the norm, not the exception".<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Tilley |first1=Helen |title=The History and Historiography of Science |journal=Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History |date=20 November 2018 |doi=10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.353 |isbn=978-0-19-027773-4 |url=https://oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277734-e-353 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| While modern lingusitic studies have challenged Diop's Wolof language connection,<ref> See for example http://www.linguistics.ucla.edu/people/schuh/Papers/language_and_history.pdf | |||

| + Russell G. Schuh, "The use and misuse of language in the study of | |||

| + African history" (1997), in: Ufahamu 25(1):36-81 (in PDF, 152 kB).</ref>, | |||

| as regards the key Nile Valley peoples, they have moved away from earlier notions of a "Hamitic" race speaking Hamito-Semitic languages, and places the Egyptian language in a more localized context, centered around its general Saharan and Nilotic roots.''(F. Yurco "An Egyptological Review", 1996)''<ref>Yurco, op. cit. </ref> Linguistic analysis (Diakanoff 1998) places the origin of the Afro-Asiatic languages in northeast Africa, with older strands south of Egypt, and newer elements straddling the Nile Delta and Sinai.<ref>M.Diakonoff, Journal of Semitic Studies, 43,209 (1998)</ref> | |||

| Dawne Y. Curry, Associate Professor of History and Ethnic Studies stated that "Diop's greatest contribution to scholarly endeavours lies in his tireless search for ] and ] evidence to support his thesis. Using mummies, bone measurements and blood types to determine age and evolution, Diop revolutionized scientific enquiry" but she noted that his message was not initially well-received but "more and more scholarship began to support Diop's conclusions, earning him international acclaim".<ref>{{cite book |last1=Dawne Y. Curry. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hF_xjFL6_NEC |title=The Oxford Encyclopedia of African Thought |date=2010 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-533473-9 |pages=309–312 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Ironically, while much modern linguistic research throws Diop's Wolof claim into question, it also demonstrates African connections that Diop missed- namely several African languages that share features with Egyptian, such as the Chadic languages of west and central Africa, the Cushitic languages of northeast Africa, and the Semitic languages of Ethiopia and Eritrea.<ref>Russell G. Schuh, "The Use and Misuse of language in the study of African history" (1997), in: Ufahamu 25(1):36-81</ref> | |||

| Josep Cervello Autuori, Associate Professor and Lecturer of Egyptology assessed the cultural tradition established by Diop and noted that "the West had failed to consider its contributions, sometimes ignoring them completely, and sometimes considering them as the fruits of the socio-political excitement in the era of African independence". Autuori argued that the academic contributions of Diop should be recognised as "a recontextualisation and a rethinking of the Pharaonic civilisation from an African perspective" due to the continued parallels between Egypt and Africa.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Autuori |first1=Josep |title="Egypt, Africa and the Ancient World" In 1998, Eyre, C.J. (ed.). Proceedings of the Seventh International Congress of Egyptologists. Cambridge, 3-9 September 1995 |work=Eyre , C.J. (ed.). Proceedings of the Seventh International Congress of Egyptologists. Cambridge, 3–9 September 1995 |date=January 1998 |url=https://www.academia.edu/44911469}}</ref> | |||

| ===Broad black worldwide phenotype=== | |||

| While acknowledging the common genetic inheritance of all mankind and common evolutionary threads, Diop identified a black phenotype, stretching from India, to Australia to Africa, with physical similarities in terms of dark skin and a number of other characteristics. While a number of features such as dark skin are present in these far-flung populations, modern blood and DNA analysis places Australian and Papuan groups closer to populations of mainland Asia, as compared with stereotypical sub-Saharan "negroid" types.<ref>Templeton, op. cit</ref> | |||

| Diop was awarded the joint prize of most influential African intellectual along with W.E.B. Du Bois at the first ] in 1966.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Beatty|first1=Mario H.|date=1 January 2016|title=W.E.B. Du Bois and Cheikh Anta Diop on the origins and race of the Ancient Egyptians: some comparative notes|url=https://journals.co.za/doi/10.10520/EJC195692|journal=African Journal of Rhetoric|volume=8|issue=1|pages=45–67|hdl=10520/EJC195692}}</ref> He was awarded the ''Grand prix de la mémoire'' of the ] 2015. The ] (formerly known as the University of Dakar), in ], ], is named in his honor.<ref name="blackpast.org"/><ref name="University Cheikh Anta Diop"/> | |||

| ===Diop as a 'racialist'=== | |||

| Condemned as a racialist in some quarters, Diop never asserted a racial chauvinism or superiority, unlike many of the contemporary white writers he questioned. Indeed he eschewed such chauvinism, arguing: 'We apologise for returning to notions of race, cultural heritage, linguistic relationship, historical connections between peoples, and so on. I attach no more importance to these questions than they actually deserve in modern twentieth-century societies.'<ref>Cheikh Anta Diop, The African Origin of Civilization, op. cit., p. 236.</ref> Nevertheless since he struggled against how racial classifications were used by the European academy in relation to African peoples, much of his work has a strong "race" flavored tint. A number of individuals such as US college professor ]<ref>, speech at the Empire State Black Arts and Cultural Festival in Albany, New York, July 20, 1991</ref> have advanced a more ] view, citing Diop's work, but Diop himself repudiated racism or supremacist theories, arguing for a more balanced view of African history that it was getting during his era.<ref>Diop, op. cit</ref> | |||

| ===Negative reception=== | |||

| ==Challenges== | |||

| {{Cleanup|date=March 2007}} | |||

| {{Essay-entry}} | |||

| :Decades later, Diop's view that black variation can not be pigeon-holed as "sub-Saharan" is strongly challenged by those who argue that the Sahara desert was indeed a major barrier that isolated the populations of sub-Saharan Africa into a unique clearly distinguishable genetic cluster that is separate from populations of North Africa and that many of the populations of East Africa cluster with North Africans because of caucasoid admixture. | |||

| ] | |||

| According to Andrew Francis Clark, Associate Professor of History at the ] and Lucie Colvin Phillips, Professor of African Studies in the ], "although Diop's work has been influential, it has generally been discredited by historians".<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Clark |first1=Andrew Francis |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yNUUAQAAIAAJ |title=Historical Dictionary of Senegal |last2=Phillips |first2=Lucie Colvin |date=1994 |publisher=Scarecrow Press |isbn=978-0-8108-2747-9 |page=111 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Racial psychologist ] set out to discover whether it was logical to merge the diverse ethnic groups of sub-Saharan Africa into a broad negroid race distinguishable from other broad races and concluded that it was: | |||

| Robert O. Collins, a former history professor at ], and James M. Burns, a professor in history at ], have both characterized Diop's writings on Ancient Egypt as "]".<ref name="PZcX2jQFTRcC">{{cite book |author=Robert O. Collins |author2=James M. Burns|title=A History of Sub-Saharan Africa|date=8 February 2007|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PZcX2jQFTRcC|publisher=]|page=28|isbn=978-0-521-68708-9}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Diop's book ''Civilization or Barbarism'' was described as Afrocentric ] by professor of philosophy and author ].<ref name="6FPqDFx40vYC">{{cite book| title=The Skeptic's Dictionary: A Collection of Strange Beliefs, Amusing Deceptions, and Dangerous Delusions| author=]| date=11 January 2011| publisher=]| url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6FPqDFx40vYC |page=8| isbn=978-1-118-04563-3}}</ref> According to ], Diop's works were criticised by leading French ] who opposed the radical movements of African organizations against imperialism, but they (and later critics) noted the value of his works for the generation of a propaganda program that would promote ].<ref>{{Cite book|last=Hughes-Warrington|first=Marnie|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=LVtQ59ToUqEC&pg=PA78|title=Fifty Key Thinkers on History|date=2007-10-31|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-134-21249-1|language=en}}</ref> Likewise, Santiago Juan-Navarro, a professor of Spanish at ] described Diop as having "undertaken the task of supporting this Afrocentric view of history from an equally radical and 'mythic' point of view".<ref>{{cite book|author=Santiago Juan-Navarro|title=Archival Reflections: Postmodern Fiction of the Americas (self-reflexivity, Historical Revisionism, Utopia)|publisher=Bucknell University Press|page=151}}</ref> | |||

| On pgs 430-431 of ''the g factor'' Jensen makes reference to the chart to the right, writing: | |||

| Historian Robin Derricourt, in summarizing Diop's legacy, states that his work "increased francophone black pride, though trapped within dated models of racial classification".<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Derricourt|first=Robin|date=June 2012|title=Pseudoarchaeology: the concept and its limitations|url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/antiquity/article/abs/pseudoarchaeology-the-concept-and-its-limitations/DE4EB70319FDE95C6BFC22CD9791240B|journal=Antiquity|volume=86|issue=332|pages=524–531|doi=10.1017/S0003598X00062918|s2cid=162643326}}</ref> Stephen Howe, professor of the ] in ], writes that Diop's work is built mostly upon disagreements with ] thinkers like ], ] and ], and criticizes him for "failing to take modern research into account."<ref name=":1">{{Cite book|last=Howe|first=Stephen|title=Afrocentrism: Mythical Pasts and Imagined Homes|publisher=Verso|year=1999|isbn=978-1-85984-228-7|pages=167–168}}</ref> | |||

| :''Cavalli-Sforza et al. transformed the distance matrix to a correlation matrix consisting of 861 correlation coefficients among the forty-two populations, so they could apply principal components (PC) analysis on their genetic data...PC analysis is a wholly objective mathematical procedure. It requires no decisions or judgments on anyone's part and yields identical results for everyone who does the calculations correctly...The important point is that if various populations were fairly homogeneous in genetic composition, differing no more genetically than could be attributable only to random variation, a PC analysis would not be able to cluster the populations into a number of groups according to their genetic propinquity. In fact, a PC analysis shows that most of the forty-two populations fall very distinctly into the quadrants formed by using the first and second principal component as axes...They form quite widely separated clusters of the various populations that resemble the "classic" major racial groups-Caucasoids in the upper right, Negroids in the lower right, North East Asians in the upper left, and South East Asians (including South Chinese) and Pacific Islanders in the lower left...I have tried other objective methods of clustering on the same data (varimax rotation of the principal components, common factor analysis, and hierarchical cluster analysis). All of these types of analysis yield essentially the same picture and identify the same major racial groupings.'' | |||

| Jensen is not alone in concluding that sub-Saharan Africans form a distinguishable genetic cluster. Noah A. Rosenberg and Jonathan K. Pritchard, geneticists from the laboratory of Marcus W. Feldman of Stanford University, assayed approximately 375 polymorphisms called short tandem repeats in more than 1,000 people from 52 ethnic groups in Africa, Asia, Europe and the Americas. They looked at the varying frequencies of these polymorphisms, and were able to distinguish five different groups of people whose ancestors were typically isolated by oceans, deserts or mountains: sub-Saharan Africans; Europeans and Asians west of the Himalayas; East Asians (who Blumenbach called the yellow race); inhabitants of New Guinea and Melanesia; and Native Americans.<ref></ref> A similar finding was made by Dr. ] of Stanford University. According to the ]: | |||

| <blockquote>These five geographically isolated groups, in Dr. Risch's description, are sub-Saharan Africans; Caucasians, including people from Europe, the Indian subcontinent and the Middle East; Asians, including people from China, Japan, the Philippines and Siberia; Pacific Islanders; and Native Americans.<ref></ref></blockquote> | |||

| Kevin MacDonald, a doctor of archeology,<ref>{{cite book|title=Ancient Egypt in Africa|editor-first1=David|editor-last1=O' Conner|editor-first2=Reid|editor-last2=Andrew|publisher=UCL Press|location=London|year=2003|page=ix|isbn=978-1-84472-000-2}}</ref> was critical of what he saw as Diop's "cavalier attitude" in making "amateur, non-statistical comparison of languages" between West Africa and Egypt.<ref name="MacDonald-95">{{cite book|last=MacDonald|first=Kevin|title=Ancient Egypt in Africa|editor-first1=David|editor-last1=O' Conner|editor-first2=Reid|editor-last2=Andrew|chapter=Chapter 7: Cheikh Anta Diop and Ancient Egypt in Africa|publisher=UCL Press|location=London|year=2003|page=95|isbn=978-1-84472-000-2}}</ref> MacDonald also felt that such attitude showed "a disrespect for the discipline" and for the "methodology of linguistics".<ref name="MacDonald-95"/> He did however state that Diop had asked "appropriate and relevant questions" regarding possible relations between Egypt and the African continent beyond Nubia.<ref>{{cite book|last=MacDonald|first=Kevin|title=Ancient Egypt in Africa|editor-first1=David|editor-last1=O' Conner|editor-first2=Reid|editor-last2=Andrew|chapter=Chapter 7: Cheikh Anta Diop and Ancient Egypt in Africa|publisher=UCL Press|location=London|year=2003|page=96|isbn=978-1-84472-000-2}}</ref> | |||

| Diop's belief that all the skull and facial variation in East Africa was part of the natural black diversity has also been contradicted by studies showing modern-day ]ns in the ] have been found to generally cluster as an intermediate cluster between sub-Saharan Africans and ]erners (), reflecting the nation's proximity to ] and the Middle East. A number of matrilineal genetic studies have detected almost equal sub-Saharan and western Eurasian lineages among the population examined () | |||

| Historian ] criticizes Diop's claim that ] was black, as being without qualification, a futile exercise and "probably the single most unsuccessful effort on the part of a scholar to determine the racial origins of an Egyptian notable".<ref>{{Cite book |last=Walker |first=Clarence E. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DhdkAAAAMAAJ |title=We Can't Go Home Again: An Argument About Afrocentrism |date=2001-06-14 |publisher=Oxford University Press, USA |isbn=978-0-19-509571-5 |page=53 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ===Diop's thought and criticism of modern racial clustering=== | |||

| ], scholar of Classics, accuses Diop of supplying his readers only with selected and, to some extent, distorted information. She criticizes his methodology, stating that his writing allows him to disregard historical evidence, especially if it comes from European sources.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Lefkowitz |first=M. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TnAJAwAAQBAJ |title=Not Out of Africa |date=1997 |publisher=Ripol Classic |isbn=978-5-87296-504-6 |pages=22, 160 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ====Diop and the arbitrary sorting of categories==== | |||

| Diop's fundamental criticism of scholarship on the African peoples was that classification schemes pigeonholed them into categories defined as narrowly as possible, while expanding definitions of Caucasoid groupings as broadly as possible. He held that this was both hypocrisy and bad scholarship, that ignored the wide range of indigeneous variablility of African peoples.<ref>Diop, op. cit. Evolution of the Negro world' in Presence Africaine (1964)</ref> | |||

| Historian and classicist ] states that Diop misinterprets the classical usage of color words, distorts classical sources and omits Greek and Roman authors, who he claimed make a clear distinction between Egyptians and Ethiopians.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Snowden |first=Frank M. |date=1997 |title=Misconceptions about African Blacks in the Ancient Mediterranean World: Specialists and Afrocentrists |journal=Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics |volume=4 |issue=3 |pages=28–50 |jstor=20163634 |issn=0095-5809}}</ref> | |||

| This fundamental criticism applies to the Jensen approach which uses a number of racial clustering techniqies. These techniques have in turn been challenged by more contemporary scholars (Keita and Kittles, Armelagos, et al.) for using pre-defined, arbitrary categories to cluster or assign various African peoples like the Egyptians, Ethiopians, and others into Caucasoid or "mixed" categories. Typical of this is Cavalli-Sforza's ] grouping. What is at issue is not the fact that sub-Saharan populations share certain common traits, but (a) the narrow definition of such peoples using the Sahara as a rigid dividing line, (b)the separation of such populations from related peoples like Ethiopians, Nubians, Somalians, et. al, which are assigned to a "Caucasoid" grouping, usually under different labels (Eastern Hamite, Eurasian, Middle Eastern, Mediterranean, etc). | |||

| == Publications == | |||

| Such definitions and groupings critics maintain, often publicly disavow the importance of race,<ref>Keita and Kittles, op. cit. The The Persistence of Racial Thinking, </ref> but in practice, continue to use racial groupings established in advance, and then sort data as much as possible into these pre-defined categories, rather than let the data speak for themselves. When pre-sorting is not used, different results appear than those obtained by Jensen, et al.<ref>Rick Kittles, and S. O. Y. Keita, "Interpreting African Genetic Diversity", African Archaeological Review, Vol. 16, No. 2,1999, p. 1-5</ref>. | |||

| * Rousseau, Madeleine and Cheikh Anta Diop (1948), "1848 Abolition de l'esclavage – 1948 evidence de la culture nègre", ''Le musée vivant'', issue 36–37. Special issue of journal "consacré aux problèmes culturels de l'Afrique noire a été établi par Madeleine Rousseaux et Cheikh Anta Diop". Paris: APAM, 1948. | |||

| * (1954) ''Nations nègres et culture'', Paris: Éditions Africaines. Second edition (1955), ''Nations nègres et culture: de l'antiquité nègre-égyptienne aux problèmes culturels de l'Afrique noire d'aujourd'hui'', Paris: Éditions Africaines. Third edition (1973), Paris: Présence Africaine, {{ISBN|978-2-7087-0363-6}}, {{ISBN|978-2-7087-0362-9}}. Fourth edition (1979), {{ISBN|978-2-7087-0688-0}}. | |||

| * (1959) ''L'unité culturelle de l'Afrique noire: domaines du patriarcat et du matriarcat dans l'antiquité classique'', Paris: Présence Africaine. Second edition ({{circa|1982}}), Paris: Présence Africaine, {{ISBN|978-2-7087-0406-0}}, {{ISBN|978-2-7087-0406-0}}. English edition (1959), ''The Cultural Unity of Negro Africa'' Paris. Subsequent English edition ({{circa|1962}}), Paris: Présence Africaine. English edition (1978), ''The Cultural Unity of Black Africa: the domains of patriarchy and of matriarchy in classical antiquity'', Chicago: Third World Press, {{ISBN|978-0-88378-049-7}}. Subsequent English edition (1989) London: Karnak House, {{ISBN|978-0-907015-44-4}}. | |||

| * (1960) ''L' Afrique noire pré-coloniale. Étude comparée des systèmes politiques et sociaux de l'Europe et de l'Afrique noire, de l'antiquité à la formation des états modernes'', Paris: Présence africaine. Second edition (1987), {{ISBN|978-2-7087-0479-4}}. (1987), ''Precolonial Black Africa: a comparative study of the political and social systems of Europe and Black Africa, from antiquity to the formation of modern states''. Translated by Harold J. Salemson. Westport, Conn.: L. Hill, {{ISBN|978-0-88208-187-8}}, {{ISBN|978-0-88208-188-5}}, {{ISBN|978-0-88208-187-8}}, {{ISBN|978-0-88208-188-5}}. | |||

| * (1960) ''Les Fondements culturels, techniques et industriels d'un futur état fédéral d'Afrique noire'', Paris. Second revised and corrected edition (1974), ''Les Fondements économiques et culturels d'un état fédéral d'Afrique noire'', Paris: Présence Africaine. | |||

| * (1967) ''Antériorité des civilisations nègres: mythe ou vérité historique?'' Series: Collection Préhistoire-antiquité négro-africaine, Paris: Présence Africaine. Second edition ({{circa|1993}}), {{ISBN|978-2-7087-0562-3}}, {{ISBN|978-2-7087-0562-3}}. | |||

| * (1968) ''Le laboratoire de radiocarbone de l'IFAN''. Series: Catalogues et documents, Institut Français d'Afrique Noire No. 21. | |||

| * (1974) ''The African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality'' (translation of sections of ''Antériorité des civilisations négres'' and ''Nations nègres et culture''). Translated from the French by Mercer Cook. New York: L. Hill, {{ISBN|978-0-88208-021-5}}, {{ISBN|978-0-88208-022-2}} | |||

| * (1974) ''Physique nucléaire et chronologie absolue''. Dakar: IFAN. Initiations et études Africaines no. 31. | |||

| * (1977) ''Parenté génétique de l'égyptien pharaonique et des langues négro-africaines: processus de sémitisation'', Ifan-Dakar: Les Nouvelles Éditions Africaines, {{ISBN|978-2-7236-0162-7}}. | |||

| * (1978) ''Black Africa: the economic and cultural basis for a federated state.'' Translation by Harold Salemson of ''Fondements économiques et culturels d'un état fédéral d'Afrique noire''. Westport, Conn.: Lawrence Hill & Co, {{ISBN|978-0-88208-096-3}}, {{ISBN|978-1-55652-061-7}}. New expanded edition (1987) {{ISBN|978-0-86543-058-7}} (Africa World Press), {{ISBN|978-0-88208-223-3}}. | |||

| * UNESCO Symposium on the Peopling of Ancient Egypt and the Deciphering of Meroitic Script. Cheikh Anta Diop (ed.) (1978), ''The peopling of ancient Egypt and the deciphering of Meroitic script: proceedings of the symposium held in Cairo from 28 January to 3 February 1974'', UNESCO. Subsequent edition (1997), London: Karnak House, {{ISBN|978-0-907015-99-4}}. | |||

| * ({{circa|1981}}) ''Civilisation ou barbarie: anthropologie sans complaisance'', Présence Africaine, {{ISBN|978-2-7087-0394-0}}, {{ISBN|978-2-7087-0394-0}}. English edition ({{circa|1991}}), ''Civilization or Barbarism: an authentic anthropology'' Translated from the French by Yaa-Lengi Meema Ngemi, edited by Harold J. Salemson and Marjolijn de Jager. Brooklyn, NY: Lawrence Hill Books, c1991. {{ISBN|978-1-55652-048-8}}, {{ISBN|978-1-55652-048-8}}, {{ISBN|978-1-55652-049-5}}. | |||

| * (1989) ''Nouvelles recherches sur l'égyptien ancien et les langues négro-africaines modernes'', Paris: Présence Africaine, {{ISBN|978-2-7087-0507-4}}. | |||

| * (1989) ''Egypte ancienne et Afrique Noire''. Reprint of article in ''Bulletin de l'IFAN'', vol. XXIV, series B, no. 3–4, 1962, pp. 449 à 574. Université de Dakar. Dakar: IFAN. | |||

| * ({{circa|1990}}) ''Alerte sous les tropiques: articles 1946–1960: culture et développement en Afrique noire'', Paris: Présence africaine, {{ISBN|978-2-7087-0548-7}}. English edition (1996), ''Towards the African renaissance: essays in African culture & development, 1946–1960''. Translated by Egbuna P. Modum. London: Karnak House, {{ISBN|978-0-907015-80-2}}, {{ISBN|978-0-907015-85-7}}. | |||

| * Joseph-Marie Essomba (ed.) (1996), ''Cheikh Anta Diop: son dernier message à l'Afrique et au monde''. Series: Sciences et connaissance. Yaoundé, Cameroun: Editions AMA/COE. | |||

| * (2006) ''Articles: publiés dans le bulletin de l'IFAN'', Institut fondamental d'Afrique noire (1962–1977). Series: Nouvelles du sud; no 35–36. Yaoundé: Silex. {{ISBN|978-2-912717-15-3}}, {{ISBN|978-2-912717-15-3}}, {{ISBN|978-9956-444-12-0}}, {{ISBN|978-9956-444-12-0}}. | |||

| ===Bibliography=== | |||

| ====Diop, racial self-identification and continent-wide DNA clustering==== | |||

| *Présence Africaine (ed.) (1989), ''Hommage à Cheikh Anta Diop – Homage to Cheikh Anta Diop'', Paris: Special Présence Africaine, New Bilingual Series N° 149–150. | |||

| The research of Risch (see above) is sometimes referenced in defense of categorizations by race, but some writers note that Risch, like Lewotinin (1972) and other scholars, could only find race to account for 10-15% of human genetic variability. Other follow-up studies yields even more conservative results.<ref>Kittles and Keita, op. cit.</ref> Rather than confirm racial categorization methods of Jensen, the work of Risch centers on persons who ''self-identify'' with or claim membership in a particular race. This ''self-identification'' often corresponds with DNA markers as to continent of ancestry, and is sometimes useful in medical treatments, but it says little about the sub-Saharan barrier or other African populations such as Ethiopians, Nubians, Egyptians or Somalians. | |||

| * Prince Dika-Akwa nya Bonambéla (ed.) (2006), ''Hommage du Cameroun au professeur Cheikh Anta Diop'', Dakar: Panafrika. Dakar: Nouvelles du Sud. {{ISBN|978-2-912717-35-1}}, {{ISBN|978-2-912717-35-1}}. | |||

| The research of Rosenberg and Jonathan K. Pritchard is sometimes referenced in relation to sub-Saharan groupings, But Rosenberg's and Pritchard's research also centers on persons who ''self-identify'' with a particular group, and clusters data based on vast geographic ranges and spaces, such as Europeans and Asians west of the Himalayas. Such broad continental-scale clustering says little about closely related Nilotic and Saharan populations (Nubians, Egyptians, Somalians, Ethiopians, Sudanese, etc) much closer to each other geographically, and sharing a number of common genetic, material and cultural elements. These are precisely the populations and regions most at issue in the writings of Diop. The Rosenberg/Pritchard studies also confirm what other scientists have found: that "90 percent of human genetic variation occurs within a population living on a given continent, whereas about 10 percent of the variation distinguishes continental populations."<ref>Michael J. Bamshad and Steve E. Olson, "Does Race Exist?" Scientific American: November 2003</ref> It was this ''internal'' variation, particularly the Nilotic zone of peoples, that drew most of Diop's attention. | |||

| Diop referenced self-identification in a broad, general way as part of his argument that the ancient Egyptians viewed or identified themselves as "black", a claim centering around interpretation of the word "kemet" or "kmt." This claim is a matter of controversy, with supporters citing definitions as a description of what the ancient Egyptians called themselves,<ref>Raymond Faulkner, A Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian, Oxford: Griffith Institute, 2002, p. 286.</ref> and critics who maintain that the term refers to the dark soil of Egypt.<ref>Lefkowitz, Mary "Not Out of Africa" Basic Books, 1997</ref> | |||

| ====Diop and criticism of the Saharan barrier thesis==== | |||

| Diop held that despite the Sahara, the genetic, physical and cultural elements of indigeneous African peoples were both in place and always flowed in and out of Egypt, noting transmission routes via Nubia and the Sudan, and the earlier fertility of the Sahara. More contemporary critics assert that notions of the Sahara as a dominant barrier in isolating sub-Saharan populations are both flawed and simplistic in broad historical context, given the constant movement of people over time, the fluctuations of climate over time (the Sahara was once very fertile), and the substantial representation of "sub Saharan" traits in the Nile Valley among people like the Badari. | |||

| The entire region shows a basic unity based on both the Nile and Sahara, and cannot be arbitrarily diced up into pre-assigned racial zones. As Egyptologist Frank Yurco notes: | |||

| :"Climatic cycles acted as a pump, alternately attracting African peoples onto the Sahara, then expelling them as the aridity returned (Keita 1990). Specialists in predynastic archaeology have recently proposed that the last climate-driven expulsion impelled the Saharans...into the Nile Valley ca. 5000-4500 BCE, where they intermingled with indigenous hunter-fisher-gatherer people already there (Hassan 1989; Wetterstorm 1993). Such was the origin of the distinct Egyptian populace, with its mix of agriculture/pastoralism and hunting/fishing. The resulting Badarian people, who developed the earliest Predynastic Egyptian culture, already exhibited the mix of North African and Sub-Saharan physical traits that have typified Egyptians ever since (Hassan 1985, Yurco 1989; Trigger 1978; Keita 1990; Brace et al. 1993)... Language research suggests that this Saharan-Nilotic population became speakers of the Afro-Asiatic languages... Semitic was evidently spoken by Saharans who crossed the Red Sea into Arabia and became ancestors of the Semitic speakers there, possibly around 7000 BC... In summary we may say that Egypt was a distinct North African culture rooted in the Nile Valley and on the Sahara."<ref>Frank Yurco, "An Egyptological Review", 1996 -in Mary R. Lefkowitz and Guy MacLean Rogers, Black Athena Revisited, 1996, The University of North Carolina Press, p. 62-100</ref> | |||

| ====Diop and criticism of 'true negro' classification schemes==== | |||

| Diop held that scholarship in his era isolated extreme stereotypes as regards African populations, while ignoring or downplaying data on the ground showing the complex linkages between such populations. <ref>Cheikh Anta Diop, The African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality, (Lawrence Hill Books (July 1, 1989), pp. 37-279</ref> Modern critics of the racial clustering approach coming after Diop echo this objection, using data from the oldest Nile Valley groupings as well as current peoples. This research has examined the ancient Badarian group, finding not only cultural and material linkages with those further south but physical correlations as well, including a southern modal cranial metric phentoype indicative of the Tropical African in the well-known Badarian group. | |||

| Such tropical elements were thus in place from the earliest beginnings of Egyptian civilization, not isolated somewhere South behind the Saharan barrier. This is considered to be an indigenous development based on microevolutionary principles (climate adaption, drift and selection) and not the movement of large numbers of outside peoples into Egypt.<ref>Keita, "Further studies of crania", op. cit.; Hiernaux J (1975) The People of Africa. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons; Hassan FA (1988) The predynastic of Egypt. J. World Prehist. 2: 135-185</ref> | |||

| As regards living peoples, the pattern of complexity repeats itself, calling into question the merging and splitting methods of Jensen, et al. Research in this area challenges the groupings used as (a) not reflecting today's genetic diversity in Africa, or (b) an inconsistent way to determine the racial characteristics of the ]ians. Studies of some inhabitants of Gurna, a population with an ancient cultural history, in Upper Egypt, illustrate the point. In a 2004 study, 58 native inhabitants from upper Egypt were sampled for mtDNA.<ref>Stevanovitch A, Gilles A, Bouzaid E, Kefi R, Paris F, Gayraud RP, Spadoni JL, El-Chenawi F, Beraud-Colomb E., "Mitochondrial DNA sequence diversity in a sedentary population from Egypt," Annals of Human Genetics, 2004 Jan;68(Pt 1):23-39.</ref> | |||

| The conclusion was that some of the oldest native populations in Egypt can trace part of their genetic ancestral heritage to East Africa. Selectively lumping such peoples into arbitrary Mediterranean, Middle Eastern or Caucasoid categories because they do not meet the narrow definition of a "true" type, or selectively defining certain traits like aquiline features as Eurasian or Caucasoid, ignores the complexity of the DNA data on the ground. Critics note that similar narrow definitions are not attempted with groups often classified as Caucasoid.<ref>Brown and Armelagos. op. cit. Apportionment of Racial Diversity; Keita and Kittles, The Persistence, op. cit.</ref> | |||

| <blockquote>''Our results suggest that the Gurna population has conserved the trace of an ancestral genetic structure from an ancestral East African population, characterized by a high M1 haplogroup frequency. The current structure of the Egyptian population may be the result of further influence of neighbouring populations on this ancestral population''<ref>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=14748828</ref></blockquote> | |||

| ====Diop and criticism of mixed race theories==== | |||

| Diop disputed sweeping definitions of mixed races in relation to African populations, particularly when associated with the Nile Valley. He argued instead for indigeous variants already ''in situ'' as opposed to massive insertions of Hamites, Mediterraneans, Semites or Cascasoids into ancient groupings. Mixed race theories have also been challenged by contemporary scholars in relation to African genetic diversity. These researchers hold that they too often rely on a stereotypical conception of pure or distinct races that then go on to intermingle. However such conceptions are inconsistently applied when it comes to African peoples, where typically, a "true negro" is identified and defined as narrowly as possible, but no similar attempt is made to define a "true white". These methods it is held, downplay normal geographic variation and genetic diversity found in many human populations and have distorted a true picture of African peoples. (Brown and Armelagos 2001)<ref>Apportionment of Racial Diversity: A Review, Ryan A. Brown and George J. Armelagos, 2001, Evolutionary Anthropology, 10:34-40)</ref> | |||

| :Keita and Kittles (1999) argue that modern DNA analysis points to the need for more emphasis on clinal variation and gradations that are more than adequate to explain differences between peoples rather than pre-conceived racial clusters. Variation need not be the result of a "mix" from categories such as Negroid or Caucasoid, but may be simply a contiuum of peoples in that region from skin color, to facial features, to hair, to height. The present of aquiline features for example, may not be necessarily a result of race mixture with Caucasoids, but simply another local population variant in situ. On a bigger scale, the debate reflects the growing movement to minimize race as a biological construct in analyzing the origins of human populations. | |||

| :Scholars such as Alan Templeton have also challenged the notion of mixed populations, holding that race as a biological concept is dubious and that only a minor percentage of human variability can be accounted for by distinct "races." They argue that modern DNA analysis presents a more accurate alternative, that of simply local population variants, gradations or continuums in human difference like skin color or facial shape or hair, rather than rigid categories. The notion of "mixed races" it is asserted, is built on the flawed assumptions of old racial models.<ref>Human Races: A Genetic and Evolutionary Perspective, Alan R. Templeton. American Anthropologist, 1998, 100:632-650; The Persistence of Racial Thinking and the Myth of Racial Divergence, S. O. Y. Keita, Rick A. Kittles, American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 99, No. 3 (Sep., 1997), pp. 534-544</ref> | |||

| ::"Genetic surveys and the analysis of DNA haplotype trees show that human "races" are not distinct lineages, and that this is not due to recent admixture; human "races" are not and never were "pure." Instead, human evolution has been and is characterized by many locally differentiated populations coexisting at any given time, but with sufficient genetic contact to make all of humanity a single lineage sharing a common evolutionary fate.."(Human Races: A Genetic and Evolutionary Perspective, Alan R. Templeton. American Anthropologist, 1998)<ref>Human Races: A Genetic and Evolutionary Perspective, Alan R. Templeton. American Anthropologist, 1998, 100:632-650</ref> | |||

| ====Low importance of race as an element in genetic variability==== | |||

| Modern research challenges Diop's notion of a distinctive worldwide black phenotype. Researchers such as Lewontin (1972)<ref>Lewontin R. 1972. The Apportionment of Human Diversity, Evol Biol 6:381–398</ref> point out that the genetic affinities attributable to race only make up 6-10% of variant analysis. This is a threshold well below that used to analyze lineages in other species, leading many researches to question the validity of race as a ''biological'' construct. (Apportionment of Racial Diversity: A Review, Ryan A. Brown and George J. Armelagos, 2001, Evolutionary Anthropology, 10:34-40)<ref>Apportionment of Racial Diversity: A Review, Ryan A. Brown and George J. Armelagos, 2001, Evolutionary Anthropology, 10:34-40 webfile:http://www.as.ua.edu/ant/bindon/ant275/reader/apportionment.pdf</ref> Lewontin's analysis has been validated and replicated by numerous other studies, using a wide range of different analytical methods- (Latter 1980, Nei and Roychoudhury 1982, Ryaman 1983, Dean 1994, Barbujani 1997). Other similar work using mtDNA analysis shows a larger variance ''within'' designated racial categories than outside (Excoffier 1992). Work such as Miller (1997) has found greater racial difference by focusing on specific loci, but these are compartively rare (2 out of 17, and 4 out of 109 in re-analyses by other researchers), and are well within the range of other factors such as genetic drift and clinal variation. Restudies of loci data (Lewotin, Barbajuni, Latter, et. al as noted above)yield even more conservative estimates of race as a factor in genetic variability.<ref>Apportionment, op. cit.</ref> On the basis of this data, some scholars (Owens and King 1999) hold that skin color, hair and facial features and other factors are more attributable to climate selective factors rather than stereotypic racial differences.<ref>Apportionment, op. cit.</ref> | |||

| ====Diop and criticism of race classification methodology==== | |||

| Diop fundamental disputes with classification methods is also echoed in part by criticism of modern DNA methodology. A number of scholars hold that the same pre-sorting methods used in older scholarship has been moved to DNA analysis. Such methodology it is held is often flawed by two weaknesses: (a) pre-sorting of data before the analysis begins<ref>Apportionment.. op. cit.</ref> and (b)use of very narrow samples to "represent" African populations while drawing on a broader range of data to define European classifications. In one study for example one individual from Uganda was used to stand in for all Africans, but a broad range of data was used as a stand-in for European groupings.<ref>The Persistence of Racial Thinking and the Myth of Racial Divergence, S. O. Y. Keita, Rick A. Kittles, American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 99, No. 3 (Sep., 1997), pp. 534-544</ref> | |||

| In addition, critics of these pre-sorting techniques note flawed results even within the pre-sorts, with sorting models not being able to correctly identify the region within which an individual originated, even though the models were front-loaded in advance to enhance the racial cluster approach. <ref>Apportionment of Racial Diversity.. op. cit.</ref> If these criticisms are correct, then Diop's older concerns as to techniques used in classifying African populations are still partially relevant. | |||

| Some writers posit another alternative to human variability distinct from Cavalli-Sforza's core population concept. This is based on the ], of all modern humanity emanating from Africa. Rather than the use of racial categories such as Extra-European Caucasoid, they advocate a localized population variant approach, which sees the fundamental range of peoples and types in a place, not as discrete core races migrating from one place to another, or blending with other distinct core races, but as simply local variants of an existing indigenous population.<ref>Kittle and Keita, op. cit.</ref> Hence Egyptian populations for example can be considered variants of peoples in the Niolitic region, including Nubians and Ethiopians. Such populations vary in skin color, hair , facial shape, etc and also share common cultural blending and features with others. | |||

| ====*Call for less emphasis on racial clustering and pre-sorting==== | |||

| In the light of these contradictions and modern DNA analysis as discussed above, several scholars have called for a wider view of African genetic diversity, similar to that followed with European populations.<ref>Rick Kitties, and S. O. Y. Keita, "Interpreting African Genetic Diversity", African Archaeological Review, Vol. 16, No. 2,1999, p. 1-5</ref> Populations like those in the Nile Valley can have a wide range of variation, hold Kittles and Keita in ''The Persistence of Racial Thinking and the Myth of Racial Divergence'' as opposed to pigeonholing them into ''apriori'' groupings.<ref>The Persistence of Racial Thinking and the Myth of Racial Divergence, S. O. Y. Keita, Rick A. Kittles, American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 99, No. 3 (Sep., 1997), pp. 534-544</ref> As Brown and Armelagos (2001) put it: | |||

| :"In light of this, the low proportion of genetic variance across racial groupings strongly suggests a re-examination of the race concept. It no longer makes sense to adhere to arbitrary racial categories, or to expect that the next genetic study will provide the key to racial classifications."<ref>Brown and Armelagos, "Apportionment of Racial Diversity.." op. cit. </ref> | |||

| ===Diop and the African context=== | |||