| Revision as of 23:41, 22 June 2005 editHeryu~enwiki (talk | contribs)269 editsmNo edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 06:19, 1 January 2025 edit undoMaterialscientist (talk | contribs)Edit filter managers, Autopatrolled, Checkusers, Administrators1,994,280 editsm Reverted edits by 2603:8001:6100:B3F9:D7F:BD16:C7C8:5001 (talk) (HG) (3.4.13)Tags: Huggle Rollback | ||

| (985 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Classical element}} | |||

| :''This article lists the usage in physics and philosophy of aether. For other uses, see ].'' | |||

| {{classic element}} | |||

| According to ancient and ], '''aether''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|iː|θ|ər}}, alternative spellings include ''æther'', ''aither'', and ''ether''), also known as the '''fifth element''' or '''quintessence''', is the material that fills the region of the ] beyond the ].<ref name="Lloyd" /> The concept of aether was used in several theories to explain several natural phenomena, such as the propagation of light and gravity. In the late 19th century, physicists postulated that aether permeated space, providing a medium through which light could travel in a ], but evidence for the presence of such a medium was not found in the ], and this result has been interpreted to mean that no ] exists.<ref>Carl S. Helrich, Berlin, Springer 2012, p. 26.</ref> | |||

| ==Mythological origins== | |||

| {{main|Aether (mythology)}} | |||

| {{see also|Empyrean}} | |||

| The word {{lang|grc|αἰθήρ}} (''aithḗr'') in ] means "pure, fresh air" or "clear sky".<ref>{{Cite book |last=Hobart |first=Michael E. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=r7pTDwAAQBAJ&dq=aether+homeric+greek+pure+sky&pg=PT266 |title=The Great Rift: Literacy, Numeracy, and the Religion-Science Divide |date=2018-04-16 |publisher=Harvard University Press |isbn=978-0-674-98516-2 |language=en}}</ref> In ], it was thought to be the pure essence that the gods breathed, filling the space where they lived, analogous to the '']'' breathed by mortals.<ref>Allison Muri, ''The Enlightenment Cyborg: A History of Communications and Control in the Human Machine, 1660-1830'', p. 63, University of Toronto Press, 2007 {{ISBN|0802088503}}.</ref> It is also personified as a deity, ], the son of ] and ] in traditional Greek mythology.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.theoi.com/Protogenos/Aither.html |title=AITHER |access-date=January 16, 2016 |website=AETHER : Greek protogenos god of upper air & light; mythology : AITHER}}</ref> Aether is related to {{lang|grc|αἴθω}} "to incinerate",<ref>] (1959). ], s.v. ''ai-dh-.''</ref> and intransitive "to burn, to shine" (related is the name ''Aithiopes'' (]ns; see ]), meaning "people with a burnt (black) visage").<ref> in Liddell, Scott, '']'': "Αἰθίοψ, οπος, ὁ, fem. Αἰθιοπίς, ίδος, ἡ (Αἰθίοψ as fem., A.Fr.328, 329): pl. 'Αἰθιοπῆες' Il.1.423, whence nom. 'Αἰθιοπεύς' Call.Del.208: (αἴθω, ὄψ):— properly, Burnt-face, i.e. Ethiopian, negro, Hom., etc.; prov., Αἰθίοπα σμήχειν 'to wash a blackamoor white', Luc.Ind. 28." Cf. '']'' s.v. {{lang|grc|Αἰθίοψ}}, ''Etymologicum Gudianum'' s.v.v. {{lang|grc|Αἰθίοψ}}. {{cite book |title=Etymologicum Magnum |language=el |chapter=Αἰθίοψ |chapter-url=https://archive.org/stream/etymologikontome00etymuoft#page/n34/mode/1up |place=Leipzig |year=1818 |publisher=Lipsiae Apud J.A.G. Weigel}}</ref><ref name="Fage2526">{{cite book |last1=Fage |first1=John |title=A History of Africa |publisher=Routledge |isbn=9781317797272 |pages=25–26 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mXa4AQAAQBAJ |access-date=20 January 2015|quote=... coast was called Azania, and no 'Ethiopeans', dark skinned people, were mentioned amongst its inhabitants.|date=2013-10-23}}</ref> | |||

| ==Fifth element==<!-- This section is linked from ] --> | |||

| The '''aether''' (also spelled ]) is a substance concept, historically used in science and philosophy. | |||

| ] | |||

| In ]'s '']'' (58d) speaking about air, Plato mentions that "there is the most translucent kind which is called by the name of aether (αἰθήρ)"<ref>], '']'' .</ref> but otherwise he adopted the classical system of four elements. ], who had been Plato's student at the ], agreed on this point with his former mentor, emphasizing additionally that fire has sometimes been mistaken for aether. However, in his Book '']'' he introduced a new "first" element to the system of the ]s of ] ]. He noted that the four terrestrial classical elements were subject to change and naturally moved linearly. The first element however, located in the celestial regions and heavenly bodies, moved circularly and had none of the qualities the terrestrial classical elements had. It was neither hot nor cold, neither wet nor dry. With this addition the system of elements was extended to five and later commentators started referring to the new first one as the fifth and also called it ''aether'', a word that Aristotle had used in ''On the Heavens'' and the ''Meteorology''.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Hahm |first1=David E. |title=The fifth element in Aristotle's ''De Philosophia'': A Critical Re-Examination |journal=The Journal of Hellenic Studies |date=1982 |volume=102 |pages=60–74, at p.62 |doi=10.2307/631126|jstor=631126 |s2cid=170926485 }}</ref> | |||

| Aether differed from the four terrestrial elements; it was incapable of motion of quality or motion of quantity. Aether was only capable of local motion. Aether naturally moved in circles, and had no contrary, or unnatural, motion. Aristotle also stated that ] made of aether held the stars and planets. The idea of aethereal spheres moving with natural circular motion led to Aristotle's explanation of the observed orbits of stars and planets in perfectly circular motion.<ref name = "Lloyd">{{Citation |last=Lloyd |first=G. E. R. |author-link=G. E. R. Lloyd |date=1968 |title=Aristotle: The Growth and Structure of his Thought |publisher=Cambridge Univ. Pr. |place=Cambridge |pages=133–139 |isbn=0-521-09456-9 |quote=Believing that the movements of the heavenly bodies are continuous, natural and circular, and that the natural movements of the four terrestrial elements are rectilinear and discontinuous, Aristotle concluded that the heavenly bodies must be composed of a fifth element, aither .}}</ref><ref name="smoot">{{cite web |url=http://aether.lbl.gov/www/classes/p10/aristotle-physics.html |title=Aristotle's Physics |author=George Smoot III |website=lbl.gov |access-date=20 December 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161220230803/http://aether.lbl.gov/www/classes/p10/aristotle-physics.html |archive-date=20 December 2016 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| == Brief History of Science == | |||

| Medieval scholastic philosophers granted ''aether'' changes of density, in which the bodies of the planets were considered to be more dense than the medium which filled the rest of the universe.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Grant |first1=Edward |title=Planets, Stars, & Orbs: The Medieval Cosmos, 1200-1687 |date=1996 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |location=Cambridge |isbn=978-0-521-56509-7 |pages=322–428 |edition=1st pbk.}}</ref> ] stated that the aether was "subtler than light". Fludd cites the 3rd-century view of ], concerning the aether as penetrative and non-material.<ref>Robert Fludd, "Mosaical Philosophy". London, Humphrey Moseley, 1659, p. 221.</ref> | |||

| In ] and ], ''aether'' was once believed to be a substance which filled all of space. ] included it as a fifth ] on the principle that nature abhorred a ]. Aether was also called "]". | |||

| ==Quintessence== | |||

| Oliver Nicholson points out that the older concept the aether (in contrast to the more well known luminiferous aether of the 19th century) had three properties. Among these characteristics, the aether had a non-material property, was "less than the vehicle of visible light", and was responsible for "generating metals" along with fostering the development of all bodies. <sub></sub> ] stated that the aether was of the character that it was "''subtler than light''". Fludd cites the ] view of ], concerning the aether as penetrative and non-material.<sub></sub> Other 1800s views, such as ], ], and ], was of the disposition that the aether was more akin to it actually being the ]. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] (ca. 1775)]] | |||

| Quintessence (𝓠) is the ] name of the fifth element used by medieval alchemists for a medium similar or identical to that thought to make up the heavenly bodies. It was noted that there was very little presence of quintessence within the terrestrial sphere. Due to the low presence of quintessence, earth could be affected by what takes place within the heavenly bodies.<ref name="TheAlchemists">''The Alchemists'', F. Sherwood Taylor, page 95.</ref> This theory was developed in the 14th century text ''The testament of Lullius'', attributed to ].{{citation needed|date=December 2020}} The use of quintessence became popular within medieval alchemy. Quintessence stemmed from the medieval elemental system, which consisted of the four classical elements, and aether, or quintessence, in addition to two chemical elements representing metals: ], "the stone which burns", which characterized the principle of combustibility, and ], which contained the idealized principle of metallic properties. | |||

| This elemental system spread rapidly throughout all of Europe and became popular with alchemists, especially in medicinal alchemy. Medicinal alchemy then sought to isolate quintessence and incorporate it within medicine and elixirs.<ref name="TheAlchemists" /> Due to quintessence's pure and heavenly quality, it was thought that through consumption one may rid oneself of any impurities or illnesses. In ''The book of Quintessence'', a 15th-century English translation of a continental text, quintessence was used as a medicine for many of man's illnesses. A process given for the creation of quintessence is ] of alcohol seven times.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150924110119/http://www.stavacademy.co.uk/mimir/quintessence.htm|date=2015-09-24}}, Early English Text Society original series number 16, edited by F. J. Furnivall.</ref> Over the years, the term quintessence has become synonymous with ]s, medicinal ], and the ] itself.<ref>''The Dictionary of Alchemy'', Mark Haeffner.</ref> | |||

| In ] physics, the positing of a ] was used to reconcile ] and ]. It was known that light exhibited wave-like properties, and the aether was posited as the "signal-carrying medium" in which waves of light traveled (just as waves of ] require a physical/atomic medium). By the early ], though, attempts to detect the aether (or, more specifically, attempts to detect the planet's movement through the aether) had called the concept into doubt, and it was formally dispensed with by the work of ]. In modern physics the concept of fields even in an absolute vacuum devoid of all particulate matter remains, with terms such as "]", "]s", "]" (QWS), ], ], ] and ] are frequently used. | |||

| ==Legacy== | |||

| == Extended Discussion == | |||

| {{main|Aether theories}} | |||

| With the ], physical models known as "aether theories" made use of a similar concept for the explanation of the propagation of electromagnetic and gravitational forces. As early as the 1670s, Newton used the idea of aether to help match observations to strict mechanical rules of his physics.<ref>Margaret Osler, ''Reconfiguring the World.'' The Johns Hopkins University Press 2010. (155).</ref>{{efn|In a 1675 paper, he also wrote a number of pages speculating that aether may explain how the ] interacts with the body.<ref>{{cite book |last=Gillispie |first=Charles Coulston |url=https://archive.org/details/edgeofobjectivit00char |title=The Edge of Objectivity: An Essay in the History of Scientific Ideas |publisher=Princeton University Press |year=1960 |isbn=0-691-02350-6 |location=Princeton, NJ |pages=129–30 |author-link=Charles Coulston Gillispie}}</ref>}} The early modern aether had little in common with the aether of classical elements from which the name was borrowed. These aether theories are considered to be scientifically obsolete, as the development of ] showed that ] do not require the aether for the transmission of these forces. Einstein noted that his own model which replaced these theories could itself be thought of as an aether, as it implied that the empty space between objects had its own physical properties.<ref>Einstein, Albert: "Ether and the Theory of Relativity" (1920), republished in Sidelights on Relativity (Methuen, London, 1922)</ref> | |||

| Despite the early modern aether models being superseded by general relativity, occasionally some physicists have attempted to reintroduce the concept of aether in an attempt to address perceived deficiencies in current physical models.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Dirac |first1=Paul |year=1951 |title=Is there an Aether? |journal=Nature |volume=168 |issue=4282 |pages=906–907 |doi=10.1038/168906a0 |bibcode=1951Natur.168..906D |s2cid=4288946}}</ref> One proposed model of ] has been named "]" by its proponents, in honor of the classical element.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Zlatev |first1=I. |last2=Wang |first2=L. |last3=Steinhardt |first3=P. |year=1999 |title=Quintessence, Cosmic Coincidence, and the Cosmological Constant |url=https://cds.cern.ch/record/358722 |journal=Physical Review Letters |volume=82 |issue=5 |pages=896–899 |doi=10.1103/PhysRevLett.82.896 |bibcode=1999PhRvL..82..896Z |arxiv=astro-ph/9807002 |s2cid=119073006 |type=Submitted manuscript }}</ref> This idea relates to the hypothetical form of dark energy postulated as an explanation of observations of an accelerating universe. It has also been called a ]. | |||

| "Ether or aether (aiqhr probably from αιθω, I burn), a material substance | |||

| of a more subtle kind than visible bodies, supposed to exist in those | |||

| parts of space which are apparently empty" - so began the article on the | |||

| "Ether" written by ] for ], and [[Oliver Lodge|O. | |||

| Lodge's]] book against Relativity, entitled "The ether of space". | |||

| ===Aether and light=== | |||

| The above definition encapsulates a mistake that is common to a whole | |||

| {{main|Luminiferous aether}} | |||

| epoch of ] and ]: the idea that the Aether is subtler | |||

| The motion of light was a long-standing investigation in physics for hundreds of years before the 20th century. The use of aether to describe this motion was popular during the 17th and 18th centuries, including a theory proposed by ], who was recognized in 1736 with the prize of the French Academy. In his theory, all space is permeated by aether containing "excessively small whirlpools". These whirlpools allow for aether to have a certain elasticity, transmitting vibrations from the corpuscular packets of light as they travel through.<ref>], '']'' (1910), pp. 101-02.</ref> | |||

| than matter, but is still a material, ponderable medium with 'invisible' | |||

| electromagnetic properties. The modern scientific development of Aether | |||

| theories points, instead, in a different direction with respect to both | |||

| dark and subtle properties of the Aether - it points towards the concept | |||

| of a ] medium that has 'a- photic' or ] | |||

| properties. The Aether's 'subtlety' results from its massfree or | |||

| noninertial property, and the 'invisibility' from its nonphotonic or dark | |||

| nature. This rejoins the perception of ] when it | |||

| wrestled the original concept of the Aether from ]. | |||

| This theory of ] would influence the ] of light proposed by ], in which light traveled in the form of ] via an "omnipresent, perfectly elastic medium having zero density, called aether". At the time, it was thought that in order for light to travel through a vacuum, there must have been a medium filling the void through which it could propagate, as sound through air or ripples in a pool. Later, when it was proved that the nature of light wave is ] instead of longitudinal, Huygens' theory was replaced by subsequent theories proposed by ], ] and ], which rejected the existence and necessity of aether to explain the various optical phenomena. These theories were supported by the results of the ] in which evidence for the motion of aether was conclusively absent.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Michelson |first=Albert A. |journal=American Journal of Science |volume=22 |issue=128 |year=1881 |pages=120–129 |doi=10.2475/ajs.s3-22.128.120 |title=The Relative Motion of the Earth and the Luminiferous Ether |bibcode=1881AmJS...22..120M |s2cid=130423116 |url=https://zenodo.org/record/1450060 }}</ref> The results of the experiment influenced many physicists of the time and contributed to the eventual development of Einstein's ].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Shankland |first1=R. S. |year=1964 |title=Michelson-Morley Experiment |journal=American Journal of Physics |volume=32 |issue=1 |page=16 |doi=10.1119/1.1970063 |bibcode=1964AmJPh..32...16S }}</ref> | |||

| Aether in ] is probably first mentioned by ] as a | |||

| figure of the Highest or Superior Heaven. 'Higher' than it, only its | |||

| 'mother' Nix ("The Night") and its 'father' Erebus ("The Dark"). So, | |||

| Aether is issued from the dark, the dark of the night and the dark of the | |||

| cosmos; 'his' sister is Hemera ("The Day"). In ] fables, Aether is | |||

| the 'son' of ], Chaos being uncreated and having a meaning different | |||

| than the later ] meaning of the vacuum or nothingness - a | |||

| meaning that is best translated by the dark, the empty of 'Day', where no | |||

| Light or Sun abides. It is Chaos that precedes everything, but it is from | |||

| the Aether that Heavens, Earth and Sea arise - Aether being also the | |||

| 'father' of the ], the ] (later the Roman ]) that inhabit | |||

| 'hells' (not Hades), ] - and, according to ], ] in the [[Roman | |||

| mythology]]. | |||

| ===Aether and gravitation=== | |||

| Pre-Socratic ] (], ], etc) displaced the | |||

| ], ''De gravitate aetheris'', 1683]] | |||

| relationship - as an evocation of ] solar ] - by | |||

| replacing ] with ], as identified with ] (who became the | |||

| master of Aether and ]). Helios is surrounded on all sides by Aether, | |||

| and orphism only recognized one god - Helios-Dionysus. ] later | |||

| amalgamates this god to ]. | |||

| In 1682, ] formulated the theory that the hardness of the bodies depended on the pressure of the aether.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/bernoulli|title=Bernoulli nell'Enciclopedia Treccani}}</ref> | |||

| To this swirl of mythological and nonphilosophical discussions of origins, | |||

| Aether has been used in various gravitational theories as a medium to help explain gravitation and what causes it. | |||

| ] of Clazomena (~5th century BC) counterposed two principles - | |||

| ] and ] - for two types of substances, Air and Aether. Chaos was | |||

| the principle of permanent motion (and for Anaxagoras all motion was | |||

| ]), and Nous the principle of 'order', ']', knowledge, | |||

| plasticity, creation and consistency. Nous was also the power of the | |||

| lightest substance, and thus the principle of Levity or ]. As | |||

| Aether was also the lighest of substances, Nous was its principle. All | |||

| matter was made up of Aether and Air, and created by virtue of the Nous. | |||

| Nous will later be distorted to become the basis of the philosophical | |||

| concept of ] in ]. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The birth of the scientific concept of the Aether can be traced to | |||

| A few years later, aether was used in one of Sir ]'s first published theories of gravitation, '']'' (the ''Principia'', 1687). He based the whole description of planetary motions on a theoretical law of dynamic interactions. He renounced standing attempts at accounting for this particular form of interaction between distant bodies by introducing a mechanism of propagation through an intervening medium.<ref name="Rosenfeld1969">{{cite journal |last1=Rosenfeld |first1=L. |title=Newton's views on aether and gravitation |journal=Archive for History of Exact Sciences |date=1969 |volume=6 |issue=1 |pages=29–37 |doi=10.1007/BF00327261 |s2cid=122494617}}</ref> He calls this intervening medium aether. In his aether model, Newton describes aether as a medium that "flows" continually downward toward the Earth's surface and is partially absorbed and partially diffused. This "circulation" of aether is what he associated the force of gravity with to help explain the action of gravity in a non-mechanical fashion.<ref name="Rosenfeld1969"/> This theory described different aether densities, creating an aether density gradient. His theory also explains that aether was dense within objects and rare without them. As particles of denser aether interacted with the rare aether they were attracted back to the dense aether much like cooling vapors of water are attracted back to each other to form water.<ref name="newton1679"/> In the ''Principia'' he attempts to explain the elasticity and movement of aether by relating aether to his static model of fluids. This elastic interaction is what caused the pull of gravity to take place, according to this early theory, and allowed an explanation for action at a distance instead of action through direct contact. Newton also explained this changing rarity and density of aether in his letter to ] in 1679.<ref name="newton1679">Newton, Isaac. 28 February 1679.</ref> He illustrated aether and its field around objects in this letter as well and used this as a way to inform Robert Boyle about his theory.<ref name="letter">{{cite web |url=http://www.orgonelab.org/newtonletter.htm |title=Isaac Newton's Letter to Robert Boyle, on the Cosmic Ether of Space - 1679 |author=James DeMeo |year=2009 |website=orgonelab.org |access-date=20 December 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161220231449/http://www.orgonelab.org/newtonletter.htm |archive-date=20 December 2016 |url-status=live}}</ref> Although Newton eventually changed his theory of gravitation to one involving force and the laws of motion, his starting point for the modern understanding and explanation of gravity came from his original aether model on gravitation.<ref name="robishaw">{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KkS9CQAAQBAJ&q=newton+robert+boyle+aether&pg=PA6 |title=The Esoteric Codex: Esoteric Cosmology |author=Andrew Robishaw |page=6 |date=9 April 2015 |publisher=Lulu.com |access-date=20 December 2016 |isbn=9781329053083}}{{self-published source|date=December 2020}}</ref>{{self-published inline|date=February 2020}} | |||

| ] thought - in particular to the one-all substance of ], | |||

| ] notion of a ] occupation of space, and ] ] | |||

| theory of ]. These thoughts are precursors to modern theories of a | |||

| dynamic Aether. Conversely, the notion of a static Aether, a jelly-like | |||

| Aether, finds its classical origins in ]. | |||

| In more recent times, Aether has had four distinct ], ] | |||

| and ] meanings: | |||

| === Classic Stationary Aether (], ], ], ], ], etc) === | |||

| In the 19th century, Aether designated a stationary ] of | |||

| ] that transmitted ] and permitted ] of the ] of | |||

| ] by the drag which they supposedly caused. ] | |||

| ] Aether is the prime example of the Classic Static Aether. | |||

| However, the null result of the ] forced (from | |||

| 1887 onwards) the demise of all Classic Static Aether models. Classical | |||

| theories of the Aether have retained a certain currency to this day (they | |||

| are very popular in the fringes of alternative physics), particularly in | |||

| their Aether-drag variants (eg. ]). ] mathematical | |||

| transformations and invariance - later adopted by ] to the | |||

| exclusion of an Aether - were enunciated so as to preserve the stationary | |||

| Aether hypothesis. | |||

| === Gravitational Aether (]) === | |||

| In the 1910-1925 period, ] | |||

| persisted in an antiquarian interpretation of the ] that took recourse to | |||

| an Aether of ], a ] Aether, responsible for the production | |||

| of space and gravity as physical effects: "Most careful reflection teaches | |||

| us, however, that the special theory of relativity does not compel us to | |||

| deny the aether. We may assume the existence of an aether; only (...) we | |||

| must by abstraction take from it the last mechanical characteristic which | |||

| Lorenz had still left it (...), namely, its immobility. (...) To deny the | |||

| aether is ultimately to assume that empty space has no physical qualities | |||

| whatever. (...) Recapitulating, we may say that according to the general | |||

| theory of relativity space is endowed with physical qualities; in this | |||

| sense, therefore, there exists an aether" (A. Einstein, "Aether & | |||

| Relativity", 1920). Einstein later abandoned this approach. | |||

| === New Aether (ZPE/mCBR) === | |||

| In 1913, ] and O. Stern first proposed the | |||

| notion of a cosmic heat bath whose function corresponded to their concept | |||

| of a Zero Point Energy (ZPE). Though this early concept of the ZPE was | |||

| rejected, the 1967 discovery of a microwave cosmic background radiation | |||

| (mCBR) led to a reformulation of the ZPE hypothesis by stochastic (T. | |||

| Boyer) and quantum models (H. Puthof, B. Haisch). Modern ZPE theories | |||

| have in common the notion that the "vacuum state" is an electromagnetic | |||

| field (ZPF) present even near absolute zero temperature, the ZPF being | |||

| homogeneous, isotropic and subject to Lorentz invariance. | |||

| === Dynamic Aether === | |||

| All theories of a dynamic Aether accept the null result | |||

| of the ], and explain it by the properties of a | |||

| massless or massfree Aether. ] may have the honour of being the | |||

| first who tried to enunciate the basis of a dynamic Aether by ascribing to | |||

| it the 'strange' property of 'negative energy'. Other approaches are: | |||

| ==== Orgonomy/Orgonometry: ==== | |||

| The first attempt at a theory of a dynamic | |||

| Aether was ] theory of ] (1940- 1957). Reich's | |||

| approach lay the foundations for a (micro)functionalist treatment of | |||

| physico-mathematical quantities and processes, but failed to generate a | |||

| consistent method capable of successfully distinguishing ] and | |||

| ] interactions and properties, from ']c' and ] | |||

| interactions or properties. Reich's exclusive assimilation of massfree | |||

| properties to 'orgone energy' prevented him from realizing the difference | |||

| between electric and nonelectric manifestations of the Aether as a primary | |||

| form of ]. This left his followers mired in the premature | |||

| identification of Aether with ]. | |||

| ==== The Quon/Hadronic Aether ==== | |||

| The first cogent model of a dynamic Aether | |||

| was proposed by ] as far back as 1958. Aspden's model of a dynamic | |||

| Aether invokes the existence of a near-balanced ] of cosmological | |||

| charge populated by 'Aether particles', the ], that are capable of | |||

| condensing ordinary ]-] pairs and are not subject to the | |||

| constraints of ] (hence, are massless-like). Aspden's theory has | |||

| also been called a model of the ] Aether because the proposed | |||

| Aether ] also contain positively charged mu-mesons and massive | |||

| ] and ]. | |||

| ==== Aetherometry ==== | |||

| Recently a model of an ] dynamic Aether has been proposed by ] and ], under the name of ]. Experimentally, the Correas claim to have demonstrated the existence of ] ] and ] energies, and quantitatively identified them as contiguous subspectra of ambipolar (electric) massfree energy. This theory has not found any scholarly support. | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| {{Div col|small=no}} | |||

| ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| == References == | |||

| * ] | |||

| # Oliver Nicholson, "Tesla's self-sustaining electrical generator", The historical ether. Proceedings of the Tesla Centenial Symposium, 1984. | |||

| * ] | |||

| # Robert Fludd, "Mosaical Philosophy". London, Humphrey Moseley, 1659. Pg 221. | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * {{section link|Godai (Japanese philosophy)|Void (Aether)}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| {{Div col end}} | |||

| ==References== | |||

| == External links and further reading== | |||

| '''Footnotes''' | |||

| * | |||

| {{notelist}} | |||

| * ], "''''. (PDF) | |||

| '''Citations''' | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Reflist|30em}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 06:19, 1 January 2025

Classical element| Classical elements |

|---|

| HellenisticAir WaterAetherFire Earth |

| Hinduism / Jainism / BuddhismVayu ApAkashaAgni Prithvi |

| ChineseWood (木) Water (水)Fire (火) Metal (金)Earth (土) |

| JapaneseWind (風) Water (水)Void (空)Fire (火) Earth (地) |

|

European alchemy

Air |

According to ancient and medieval science, aether (/ˈiːθər/, alternative spellings include æther, aither, and ether), also known as the fifth element or quintessence, is the material that fills the region of the universe beyond the terrestrial sphere. The concept of aether was used in several theories to explain several natural phenomena, such as the propagation of light and gravity. In the late 19th century, physicists postulated that aether permeated space, providing a medium through which light could travel in a vacuum, but evidence for the presence of such a medium was not found in the Michelson–Morley experiment, and this result has been interpreted to mean that no luminiferous aether exists.

Mythological origins

Main article: Aether (mythology) See also: EmpyreanThe word αἰθήρ (aithḗr) in Homeric Greek means "pure, fresh air" or "clear sky". In Greek mythology, it was thought to be the pure essence that the gods breathed, filling the space where they lived, analogous to the air breathed by mortals. It is also personified as a deity, Aether, the son of Erebus and Nyx in traditional Greek mythology. Aether is related to αἴθω "to incinerate", and intransitive "to burn, to shine" (related is the name Aithiopes (Ethiopians; see Aethiopia), meaning "people with a burnt (black) visage").

Fifth element

In Plato's Timaeus (58d) speaking about air, Plato mentions that "there is the most translucent kind which is called by the name of aether (αἰθήρ)" but otherwise he adopted the classical system of four elements. Aristotle, who had been Plato's student at the Academy, agreed on this point with his former mentor, emphasizing additionally that fire has sometimes been mistaken for aether. However, in his Book On the Heavens he introduced a new "first" element to the system of the classical elements of Ionian philosophy. He noted that the four terrestrial classical elements were subject to change and naturally moved linearly. The first element however, located in the celestial regions and heavenly bodies, moved circularly and had none of the qualities the terrestrial classical elements had. It was neither hot nor cold, neither wet nor dry. With this addition the system of elements was extended to five and later commentators started referring to the new first one as the fifth and also called it aether, a word that Aristotle had used in On the Heavens and the Meteorology.

Aether differed from the four terrestrial elements; it was incapable of motion of quality or motion of quantity. Aether was only capable of local motion. Aether naturally moved in circles, and had no contrary, or unnatural, motion. Aristotle also stated that celestial spheres made of aether held the stars and planets. The idea of aethereal spheres moving with natural circular motion led to Aristotle's explanation of the observed orbits of stars and planets in perfectly circular motion.

Medieval scholastic philosophers granted aether changes of density, in which the bodies of the planets were considered to be more dense than the medium which filled the rest of the universe. Robert Fludd stated that the aether was "subtler than light". Fludd cites the 3rd-century view of Plotinus, concerning the aether as penetrative and non-material.

Quintessence

Quintessence (𝓠) is the Latinate name of the fifth element used by medieval alchemists for a medium similar or identical to that thought to make up the heavenly bodies. It was noted that there was very little presence of quintessence within the terrestrial sphere. Due to the low presence of quintessence, earth could be affected by what takes place within the heavenly bodies. This theory was developed in the 14th century text The testament of Lullius, attributed to Ramon Llull. The use of quintessence became popular within medieval alchemy. Quintessence stemmed from the medieval elemental system, which consisted of the four classical elements, and aether, or quintessence, in addition to two chemical elements representing metals: sulphur, "the stone which burns", which characterized the principle of combustibility, and mercury, which contained the idealized principle of metallic properties.

This elemental system spread rapidly throughout all of Europe and became popular with alchemists, especially in medicinal alchemy. Medicinal alchemy then sought to isolate quintessence and incorporate it within medicine and elixirs. Due to quintessence's pure and heavenly quality, it was thought that through consumption one may rid oneself of any impurities or illnesses. In The book of Quintessence, a 15th-century English translation of a continental text, quintessence was used as a medicine for many of man's illnesses. A process given for the creation of quintessence is distillation of alcohol seven times. Over the years, the term quintessence has become synonymous with elixirs, medicinal alchemy, and the philosopher's stone itself.

Legacy

Main article: Aether theoriesWith the 18th century physics developments, physical models known as "aether theories" made use of a similar concept for the explanation of the propagation of electromagnetic and gravitational forces. As early as the 1670s, Newton used the idea of aether to help match observations to strict mechanical rules of his physics. The early modern aether had little in common with the aether of classical elements from which the name was borrowed. These aether theories are considered to be scientifically obsolete, as the development of special relativity showed that Maxwell's equations do not require the aether for the transmission of these forces. Einstein noted that his own model which replaced these theories could itself be thought of as an aether, as it implied that the empty space between objects had its own physical properties.

Despite the early modern aether models being superseded by general relativity, occasionally some physicists have attempted to reintroduce the concept of aether in an attempt to address perceived deficiencies in current physical models. One proposed model of dark energy has been named "quintessence" by its proponents, in honor of the classical element. This idea relates to the hypothetical form of dark energy postulated as an explanation of observations of an accelerating universe. It has also been called a fifth fundamental force.

Aether and light

Main article: Luminiferous aetherThe motion of light was a long-standing investigation in physics for hundreds of years before the 20th century. The use of aether to describe this motion was popular during the 17th and 18th centuries, including a theory proposed by Johann II Bernoulli, who was recognized in 1736 with the prize of the French Academy. In his theory, all space is permeated by aether containing "excessively small whirlpools". These whirlpools allow for aether to have a certain elasticity, transmitting vibrations from the corpuscular packets of light as they travel through.

This theory of luminiferous aether would influence the wave theory of light proposed by Christiaan Huygens, in which light traveled in the form of longitudinal waves via an "omnipresent, perfectly elastic medium having zero density, called aether". At the time, it was thought that in order for light to travel through a vacuum, there must have been a medium filling the void through which it could propagate, as sound through air or ripples in a pool. Later, when it was proved that the nature of light wave is transverse instead of longitudinal, Huygens' theory was replaced by subsequent theories proposed by Maxwell, Einstein and de Broglie, which rejected the existence and necessity of aether to explain the various optical phenomena. These theories were supported by the results of the Michelson–Morley experiment in which evidence for the motion of aether was conclusively absent. The results of the experiment influenced many physicists of the time and contributed to the eventual development of Einstein's theory of special relativity.

Aether and gravitation

In 1682, Jakob Bernoulli formulated the theory that the hardness of the bodies depended on the pressure of the aether. Aether has been used in various gravitational theories as a medium to help explain gravitation and what causes it.

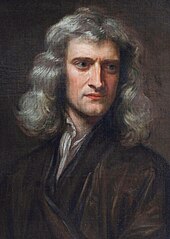

A few years later, aether was used in one of Sir Isaac Newton's first published theories of gravitation, Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (the Principia, 1687). He based the whole description of planetary motions on a theoretical law of dynamic interactions. He renounced standing attempts at accounting for this particular form of interaction between distant bodies by introducing a mechanism of propagation through an intervening medium. He calls this intervening medium aether. In his aether model, Newton describes aether as a medium that "flows" continually downward toward the Earth's surface and is partially absorbed and partially diffused. This "circulation" of aether is what he associated the force of gravity with to help explain the action of gravity in a non-mechanical fashion. This theory described different aether densities, creating an aether density gradient. His theory also explains that aether was dense within objects and rare without them. As particles of denser aether interacted with the rare aether they were attracted back to the dense aether much like cooling vapors of water are attracted back to each other to form water. In the Principia he attempts to explain the elasticity and movement of aether by relating aether to his static model of fluids. This elastic interaction is what caused the pull of gravity to take place, according to this early theory, and allowed an explanation for action at a distance instead of action through direct contact. Newton also explained this changing rarity and density of aether in his letter to Robert Boyle in 1679. He illustrated aether and its field around objects in this letter as well and used this as a way to inform Robert Boyle about his theory. Although Newton eventually changed his theory of gravitation to one involving force and the laws of motion, his starting point for the modern understanding and explanation of gravity came from his original aether model on gravitation.

See also

- Akasha

- Celestial spheres

- Dark matter

- Energy (esotericism)

- Etheric body

- Etheric force

- Etheric plane

- Godai (Japanese philosophy) § Void (Aether)

- Prana

- Radiant energy

References

Footnotes

- In a 1675 paper, he also wrote a number of pages speculating that aether may explain how the soul interacts with the body.

Citations

- ^ Lloyd, G. E. R. (1968), Aristotle: The Growth and Structure of his Thought, Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr., pp. 133–139, ISBN 0-521-09456-9,

Believing that the movements of the heavenly bodies are continuous, natural and circular, and that the natural movements of the four terrestrial elements are rectilinear and discontinuous, Aristotle concluded that the heavenly bodies must be composed of a fifth element, aither .

- Carl S. Helrich, The Classical Theory of Fields: Electromagnetism Berlin, Springer 2012, p. 26.

- Hobart, Michael E. (2018-04-16). The Great Rift: Literacy, Numeracy, and the Religion-Science Divide. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-98516-2.

- Allison Muri, The Enlightenment Cyborg: A History of Communications and Control in the Human Machine, 1660-1830, p. 63, University of Toronto Press, 2007 ISBN 0802088503.

- "AITHER". AETHER : Greek protogenos god of upper air & light; mythology : AITHER. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- Pokorny, Julius (1959). Indogermanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch, s.v. ai-dh-.

- Αἰθίοψ in Liddell, Scott, A Greek–English Lexicon: "Αἰθίοψ, οπος, ὁ, fem. Αἰθιοπίς, ίδος, ἡ (Αἰθίοψ as fem., A.Fr.328, 329): pl. 'Αἰθιοπῆες' Il.1.423, whence nom. 'Αἰθιοπεύς' Call.Del.208: (αἴθω, ὄψ):— properly, Burnt-face, i.e. Ethiopian, negro, Hom., etc.; prov., Αἰθίοπα σμήχειν 'to wash a blackamoor white', Luc.Ind. 28." Cf. Etymologicum Genuinum s.v. Αἰθίοψ, Etymologicum Gudianum s.v.v. Αἰθίοψ. "Αἰθίοψ". Etymologicum Magnum (in Greek). Leipzig: Lipsiae Apud J.A.G. Weigel. 1818.

- Fage, John (2013-10-23). A History of Africa. Routledge. pp. 25–26. ISBN 9781317797272. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

... coast was called Azania, and no 'Ethiopeans', dark skinned people, were mentioned amongst its inhabitants.

- Plato, Timaeus 58d.

- Hahm, David E. (1982). "The fifth element in Aristotle's De Philosophia: A Critical Re-Examination". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 102: 60–74, at p.62. doi:10.2307/631126. JSTOR 631126. S2CID 170926485.

- George Smoot III. "Aristotle's Physics". lbl.gov. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- Grant, Edward (1996). Planets, Stars, & Orbs: The Medieval Cosmos, 1200-1687 (1st pbk. ed.). Cambridge : Cambridge University Press. pp. 322–428. ISBN 978-0-521-56509-7.

- Robert Fludd, "Mosaical Philosophy". London, Humphrey Moseley, 1659, p. 221.

- ^ The Alchemists, F. Sherwood Taylor, page 95.

- The book of Quintessence Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine, Early English Text Society original series number 16, edited by F. J. Furnivall.

- The Dictionary of Alchemy, Mark Haeffner.

- Margaret Osler, Reconfiguring the World. The Johns Hopkins University Press 2010. (155).

- Gillispie, Charles Coulston (1960). The Edge of Objectivity: An Essay in the History of Scientific Ideas. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 129–30. ISBN 0-691-02350-6.

- Einstein, Albert: "Ether and the Theory of Relativity" (1920), republished in Sidelights on Relativity (Methuen, London, 1922)

- Dirac, Paul (1951). "Is there an Aether?". Nature. 168 (4282): 906–907. Bibcode:1951Natur.168..906D. doi:10.1038/168906a0. S2CID 4288946.

- Zlatev, I.; Wang, L.; Steinhardt, P. (1999). "Quintessence, Cosmic Coincidence, and the Cosmological Constant". Physical Review Letters (Submitted manuscript). 82 (5): 896–899. arXiv:astro-ph/9807002. Bibcode:1999PhRvL..82..896Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.82.896. S2CID 119073006.

- Whittaker, Edmund Taylor, A History of the Theories of Aether and Electricity from the Age of Descartes to the Close of the 19th Century (1910), pp. 101-02.

- Michelson, Albert A. (1881). "The Relative Motion of the Earth and the Luminiferous Ether". American Journal of Science. 22 (128): 120–129. Bibcode:1881AmJS...22..120M. doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-22.128.120. S2CID 130423116.

- Shankland, R. S. (1964). "Michelson-Morley Experiment". American Journal of Physics. 32 (1): 16. Bibcode:1964AmJPh..32...16S. doi:10.1119/1.1970063.

- "Bernoulli nell'Enciclopedia Treccani".

- ^ Rosenfeld, L. (1969). "Newton's views on aether and gravitation". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 6 (1): 29–37. doi:10.1007/BF00327261. S2CID 122494617.

- ^ Newton, Isaac."Isaac Newton to Robert Boyle, 1679." 28 February 1679.

- James DeMeo (2009). "Isaac Newton's Letter to Robert Boyle, on the Cosmic Ether of Space - 1679". orgonelab.org. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- Andrew Robishaw (9 April 2015). The Esoteric Codex: Esoteric Cosmology. Lulu.com. p. 6. ISBN 9781329053083. Retrieved 20 December 2016.