| Revision as of 23:28, 11 September 2007 editSarvagnya (talk | contribs)9,152 edits it is "remover of obstacles" not "God of obstacles"← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 03:03, 23 December 2024 edit undoHbanm (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users699 editsm CorrectionTags: Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Hindu god of new beginnings, wisdom and luck}} | |||

| {{otheruses}} | |||

| {{Redirect-multi|3|Vinayaka|Ganapati|Lambodara||Vinayaka (disambiguation)|and|Ganapati (disambiguation)|and|Lambodara (film)|and|Ganesha (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{Hdeity infobox| <!--Misplaced Pages:WikiProject Hindu mythology--> | |||

| {{featured article}} | |||

| | Name = Ganesha ({{IAST|Gaṇeśa}}) | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=February 2022}} | |||

| | Image = Ganesha Basohli miniature circa 1730 Dubost p73.jpg | |||

| {{Use Indian English|date=October 2019}} | |||

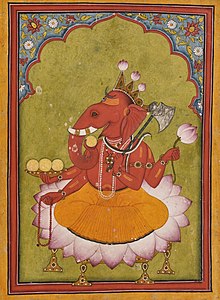

| | Caption = '''Ganesha''': Remover of Obstacles. ] miniature, circa 1730. National Museum, New Delhi.<ref>"Ganesha getting ready to throw his lotus. Basohli miniature, circa 1730. National Museum, New Delhi. Attired in an orange dhoti, his body is enitirely red. On the three points of his tiny crown, budding lotuses have been fixed. {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}} holds in his two right hands the rosary and a cup filled with three modakas (a fourth substituted by the curving trunk is just about to be tasted). In his two left hands, {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}} holds a large lotus above and an axe below, with its handle leaning against his shoulder. In the {{IAST|Mudgalapurāṇa}} (VII, 70), in order to kill the demon of egotism ({{IAST|Mamāsura}}) who had attacked him, {{IAST|Gaṇeśa Vighnarāja}} throws his lotus at him. Unable to bear the fragrance of the divine flower, the demon surrenders to {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}}." For quotation of description of the work, see: Martin-Dubost (1997), p. 73.</ref> | |||

| {{Infobox deity | |||

| | Devanagari = {{lang|sa|गणेश}} | |||

| | type = Hindu | |||

| | Sanskrit_Transliteration = {{IAST|gaṇeśa}} | |||

| | name = Ganesha | |||

| | Pali_Transliteration = | |||

| | gender = Male | |||

| | Tamil_script = | |||

| | father = ] | |||

| | Affiliation = ] | |||

| | mother = ] | |||

| | Mantra = {{lang|sa|ॐ गणेशाय नमः}} <br />({{IAST|Oṃ Gaṇeśāya Namaḥ}}) | |||

| | siblings = ] (brother) | |||

| | Weapon = {{IAST|Paraśu}} (Axe),<ref>For the paraśu (axe) as a weapon of Ganesha, see: Jansen, p. 40.</ref><ref>For the ''{{IAST|paraśu}}'' as an attribute of Ganesha, see: Nagar, Appendix I.</ref><br /> {{IAST|Pāśa}} (Lasso),<ref>For the snare as a weapon of Ganesha, see: Jansen, p. 46.</ref><ref>For the ''{{IAST|pāśa}}'' as weapon of Ganesha in various forms, see: Nagar, Appendix I.</ref><br /> ] (Hook)<ref>For the elephant hook as a weapon of Ganesha, see: Jansen. p. 46.</ref><ref>For the {{IAST|aṅkuśa}} as an attribute of Ganesha, see: Nagar, Appendix I.</ref> | |||

| | consort = ], ] and ] or ] in some traditions | |||

| | Consort = ] (wisdom),<br/>Riddhi (prosperity),<br/>] (attainment) | |||

| | deity_of = God of New Beginnings, Wisdom and Luck; Remover of Obstacles{{Sfn|Heras|1972|p=58}}{{Sfn|Getty|1936|p= 5}}<br/> | |||

| | Mount = mouse | |||

| ] (]) | |||

| | image = Ganesha_Basohli_miniature_circa_1730_Dubost_p73.jpg | |||

| | caption = ] miniature, c. 1730. ]<ref>"Ganesha getting ready to throw his lotus. Basohli miniature, circa 1730. National Museum, New Delhi. In the {{IAST|Mudgalapurāṇa}} (VII, 70), in order to kill the demon of egotism ({{IAST|Mamāsura}}) who had attacked him, {{IAST|Gaṇeśa Vighnarāja}} throws his lotus at him. Unable to bear the fragrance of the divine flower, the demon surrenders to {{IAST|Gaṇeśha}}." For quotation of description of the work, see: {{Harvard citation no brackets|Martin-Dubost|1997|p=73}}.</ref> | |||

| | alt = Attired in an orange dhoti, a four-armed elephant-headed man sits on a large lotus. His body is red in colour and he wears various golden necklaces and bracelets and a snake around his neck. On the three points of his crown, budding lotuses have been fixed. He holds in his two right hands the rosary (lower hand) and a cup filled with three modakas (round yellow sweets), a fourth modaka held by the curving trunk is just about to be tasted. In his two left hands, he holds a lotus in the upper hand and an axe in the lower one, with its handle leaning against his shoulder. | |||

| | day = ] or ], ] | |||

| | affiliation = ], ] (]), ] (]) | |||

| | mantra = {{IAST|Oṃ Śrī Gaṇeśāya Namaḥ<br/>Oṃ Gaṃ Gaṇapataye Namaḥ}} | |||

| | abode = • ] (with parents) <br/>• Svānandaloka | |||

| | weapon = ], ], ] | |||

| | mount = ] | |||

| | symbols = ], ], ] | |||

| | festivals = ], ] | |||

| | texts = '']'', '']'', '']'' | |||

| | equivalent1_type = Japanese Buddhist | |||

| | equivalent1 = ] | |||

| | children = Shubha/Ksema and Labha (Sons) | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{Hinduism |deities}} | |||

| '''Ganesha''' (]: {{lang|sa|गणेश}}; {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}}; {{Audio|Ganesha.ogg|listen}}, also spelled '''Ganesa''' or '''Ganesh''', is one of the best-known and most worshipped deities in ].<ref>Rao, p. 1.</ref> Although he is known by many attributes, Ganesha's elephant head makes him easy to identify.<ref>Martin-Dubost, p. 2.</ref> Several texts relate ] associated with his birth and exploits and explain his distinct iconography. Ganesha is worshipped as the as the remover of obstacles ('''Vighnesha'''),<ref>These ideas are so common that Courtright uses them in the title of his book, ''Ganesha: Lord of Obstacles, Lord of Beginnings''. For the name Vighnesha, see: Courtright, pp. 156, 213.</ref> patron of arts and sciences, and the god of intellect and wisdom.<ref>Heras, p. 58.</ref> He is honoured with affection at the start of any ritual or ceremony and invoked as the "Patron of Letters" at the beginning of any writing.<ref>Getty, p. 5.</ref> | |||

| '''Ganesha''' ({{langx|sa|गणेश}}, {{IAST3|Gaṇeśa}})<!--Do not remove, WP:INDICSCRIPT doesn't apply to WikiProject Hinduism-->, also spelled '''Ganesh''', and also known as '''Ganapati''', '''Vinayaka''', '''Lambodara''' and '''Pillaiyar''', is one of the best-known and most worshipped ] in the ]{{Sfn|Ramachandra Rao|1992|p=6}} and is the Supreme God in the ] sect. His depictions are found throughout ].<ref>{{Spaces|5}} | |||

| Depictions of elephant-headed human figures, which some identify with Ganesha, appear in ] and ] as early as the 2nd century BCE.<ref> For a discussion of early depiction of elephant-headed figures in art, see {{Harvnb|Krishan|1981-1982|p=287-290}} or {{Harvnb|Krishna|1985|p=31-32}}</ref> However Ganesha emerges as a distinct deity in clearly-recognizable form beginning in the fourth and fifth centuries, during the ]. His popularity rose quickly, and he was formally included among the five primary deities of ] (a Hindu denomination) in the ninth century. A sect of devotees (called ]; ]: {{IAST|gāṇapatya}}) who identified Ganesha as the supreme deity arose during this period.<ref>For history of the development of the ''{{IAST|gāṇapatya}}'' and their relationship to the wide geographic dispersion of Ganesha worship, see: Chapter 6, "The {{IAST|Gāṇapatyas}}" in: Thapan (1997), pp. 176-213.</ref> The principal scriptures dedicated to Ganesha are the '']'', the '']'', and the '']''. | |||

| *{{Harvard citation no brackets|Brown|1991|p=1}} "{{IAST|Gaṇeśa}} is often said to be the most worshipped god in India." | |||

| *{{Harvard citation no brackets|Getty|1936|p=1}} "{{IAST|Gaṇeśa}}, Lord of the {{IAST|Gaṇas}}, although among the latest deities to be admitted to the Brahmanic pantheon, was, and still is, the most universally adored of all the Hindu gods and his image is found in practically every part of India."</ref> ] worship him regardless of affiliations.<ref>{{Spaces|5}} | |||

| *{{Harvard citation no brackets|Ramachandra Rao|1992|p=1}} | |||

| *{{Harvard citation no brackets|Martin-Dubost|1997|p=1}} | |||

| *{{Harvard citation no brackets|Brown|1991|p=1}}</ref> Devotion to Ganesha is widely diffused and extends ] and beyond India.<ref>{{Spaces|5}} | |||

| *Chapter XVII, "The Travels Abroad", in: {{Harvard citation no brackets|Nagar|1992|pp=175–187}}. For a review of Ganesha's geographic spread and popularity outside of India. | |||

| *{{Harvard citation no brackets|Getty|1936|pp=37–38}}, For discussion of the spread of Ganesha worship to Nepal, ], Tibet, Burma, Siam, ], Java, Bali, Borneo, China, and Japan | |||

| *{{Harvard citation no brackets|Martin-Dubost|1997|pp=311–320}} | |||

| *{{Harvard citation no brackets|Thapan|1997|p=13}} | |||

| *{{Harvard citation no brackets|Apte|1965|pp=2–3}}</ref> | |||

| Although Ganesha has many attributes, he is readily identified by his ] head and four arms.<ref>Martin-Dubost, p. 2.</ref> He is widely revered, more specifically, as the remover of obstacles and bringer of good luck;<ref>For Ganesha's role as an eliminator of obstacles, see commentary on {{IAST|Gaṇapati Upaniṣad}}, verse 12 in {{Harvnb|Saraswati|2004|p=80}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title= India - Mahabharata. Fulbright-Hays Summer Seminar Abroad 1994 (India) |first1=Carole|last1=DeVito|first2=Pasquale|last2=DeVito|publisher=United States Educational Foundation in India|year=1994|page=4}}</ref> the patron of ] and ]; and the ] of intellect and wisdom.<ref>{{Harvnb|Heras|1972|p=58}}</ref> As the god of beginnings, he is honoured at the start of rites and ceremonies. Ganesha is also invoked during writing sessions as a patron of letters and learning.{{Sfn|Getty|1936|p= 5}}<ref name = "Vignesha">, Vigna means obstacles Nasha means destroy. These ideas are so common that Courtright uses them in the title of his book, ''Ganesha: Lord of Obstacles, Lord of Beginnings''.</ref> Several texts relate ] associated with his birth and exploits. | |||

| Ganesha is one of the most-worshipped divinities in India.<ref>"{{IAST|Gaṇeśa}} is often said to be the most worshipped god in India." Brown, p. 1.</ref><ref>"{{IAST|Gaṇeśa}}, Lord of the {{IAST|Gaṇas}}, although among the latest deities to be admitted to the Brahmanic pantheon, was, and still is, the most universally adored of all the Hindu gods, and his image is found in practically every part of India." Getty, p. 1.</ref> Worship of Ganesha is considered complementary with other forms of the divine. Various Hindu sects worship him regardless of other affiliations.<ref>Rao, p. 1.</ref><ref>Martin-Dubost, pp. 2-4.</ref><ref>Brown, p. 1.</ref> Devotion to Ganesha is widely diffused and extends ].<ref>For a review of Ganesha's geographic spread and popularity outside of India, see: Chapter XVII, "The Travels Abroad", in: Nagar (1992), pp. 175-187.</ref><ref>For discussion of the spread of Ganesha worship to Nepal, Chinese Turkestan, Tibet, Burma, Siam, Indo-China, Java, Bali, Borneo, China, and Japan, see: Getty, pp. 37-88.</ref><ref>Martin-Dubost, pp. 311-320.</ref><ref>Thapan, p. 13.</ref><ref>Pal, p. x.</ref> | |||

| Ganesha is mentioned in Hindu texts between the 1st century BCE and 2nd century CE, and a few Ganesh images from the 4th and 5th centuries CE have been documented by scholars.<ref>Narain, A.K. "{{IAST|Gaṇeśa}}: The Idea and the Icon" in {{Harvnb|Brown|1991|p=27}}</ref> Hindu texts identify him as the son of ] and ] of the ] tradition, but he is a pan-Hindu god found in its various traditions.<ref>{{cite book|author=Gavin D.|first=Flood|url=https://archive.org/details/introductiontohi0000floo|title=An Introduction to Hinduism|publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=1996|isbn=978-0521438780|pages=–18, 110–113|author-link=Gavin Flood|url-access=registration}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Vasudha|first=Narayan|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=E0Mm6S1XFYAC|title=Hinduism|publisher=The Rosen Publishing Group|year=2009|isbn=978-1435856202|pages=30–31|author-link=Vasudha Narayanan}}</ref> In the ''Ganapatya'' tradition of Hinduism, Ganesha is the Supreme Being.<ref>For history of the development of the ''{{IAST|gāṇapatya}}'' and their relationship to the wide geographic dispersion of Ganesha worship, see: Chapter 6, "The {{IAST|Gāṇapatyas}}" in: {{Harvard citation no brackets|Thapan|1997|pp=176–213}}.</ref> The principal texts on Ganesha include the '']'', the '']'' and the '']''. | |||

| == Etymology and other names == | |||

| ] (the central shrine for the regional ] complex)<ref>Courtright, pp. 212-213.</ref>]] | |||

| ==Etymology and other names== | |||

| Ganesha has many other titles and epithets, including '''Ganapati''' and '''{{IAST|Vighneśvara}}'''. The ] title of respect ''Shri'' (]: {{lang|sa|श्री}}; {{IAST|śrī}}, also spelled ''Sri'' or ''Shree'') is often added before his name. One popular way to worship Ganesha is to chant one of the '']s'', which literally means "a thousand names of Ganesha." Each name in the ] conveys a different meaning and symbolises a different aspect of Ganesha. | |||

| Ganesha has been ascribed many other titles and epithets, including ''Ganapati'' (''Ganpati''), ''Vighneshvara'', and ''Pillaiyar''. The Hindu title of respect '']'' ({{langx|sa|श्री}}; ]: ''{{IAST|śrī}}''; also spelled ''Sri'' or ''Shree'') is often added before his name.<ref>{{Cite web|date=4 April 2019|title=Lord Ganesha – Symbolic description of Lord Ganesha {{!}} – Times of India|url=https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/astrology/rituals-puja/symbolic-description-of-lord-ganesha/articleshow/68207007.cms|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201115155341/https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/astrology/rituals-puja/symbolic-description-of-lord-ganesha/articleshow/68207007.cms|archive-date=15 November 2020|access-date=4 November 2020|website=]|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| There are at least two different versions of the Ganesha Sahasranama. One of these is drawn from the '']'', a Hindu scripture that venerates Ganesha.<ref>For an English translation of ''Ganesha Purana'' 1.46, see: Bailey, pp. 258-269.</ref> | |||

| The name ''Ganesha'' is a Sanskrit compound, joining the words '']'' ({{IAST|gaṇa}}), meaning a 'group, multitude, or categorical system' and ''isha'' ({{IAST|īśa}}), meaning 'lord or master'.<ref>* Narain, A. K. "{{IAST|Gaṇeśa}}: A Protohistory of the Idea and the Icon". {{Harvard citation no brackets|Brown|1991|pp=21–22}}. | |||

| The name '''Ganesha''' is a Sanskrit compound, joining the words '']'' (]: {{lang|sa|गण}}; ''{{IAST|gaṇa}}''), meaning a group, multitude, or categorical system and ''isha'' (]: {{lang|sa|ईश}}; ''{{IAST|īśa}}''), meaning lord or master.<ref name=Narain>Narain, A. K. "{{IAST|Gaṇeśa}}: A Protohistory of the Idea and the Icon". Brown, pp. 21-22.</ref><ref>Apte, p. 395.</ref> The word '']'' when associated with Ganesha is often taken to refer to the gaņas, a troop of semi-divine beings that form part of the retinue of ] (]: "{{IAST|Śiva}}").<ref>For the derivation of the name and relationship with the {{IAST|gaņas}}, see: Martin-Dubost. p. 2.</ref> The term more generally means a category, class, community, association, or corporation.<ref>Apte, p. 395.</ref> Some commentators interpret the name "Lord of the {{IAST|Gaņas}}" to mean "Lord of created categories," such as the elements.<ref>The word gaņa is interpreted in this metaphysical sense by Bhāskararāya in his commentary on the {{IAST|gaṇeśasahasranāma}}. See in particular commentary on verse 6 including names {{IAST|Gaṇeśvaraḥ}} and {{IAST|Gaṇakrīḍaḥ}} ''{{IAST|Gaṇeśasahasranāmastotram: mūla evaṁ srībhāskararāyakṛta ‘khadyota’ vārtika sahita}}''. ({{IAST|Prācya Prakāśana}}: {{IAST|Vārāṇasī}}, 1991). Source text with a commentary by {{IAST|Bhāskararāya}} in Sanskrit.</ref> The translation "Lord of Hosts" may convey a familiar sense to Western readers. '''Ganapati''' (]: {{lang|sa|गणपति}}; {{IAST|gaṇapati}}) is a synonym for ''Ganesha'', being a compound composed of ''{{IAST|gaṇa}}'', meaning "group", and ''{{IAST|pati}}'', meaning "ruler" or "lord."<ref>Apte, p. 395.</ref> The '']'', an early Sanskrit lexicon, lists eight synonymns of ''Ganeśa'' : '''Vināyaka''', '''{{IAST|Vighnarāja}}''' (equivalent to '''{{IAST|Vighneśa}}'''), '''{{IAST|Dvaimātura}}''', '''{{IAST|Gaṇādhipa}}''' (equivalent to {{IAST|Gaṇapati}} and {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}}), '''Ekadanta''', '''Heramba''', '''Lambodara''' and '''Gajānana'''.<ref>For electronic source text of {{IAST|Amarakośa}} versified as (1.1.93) {{IAST|vināyako vighnarājadvaimāturagaṇādhipāḥ}}; (1.1.94) {{IAST|apyekadantaherambalambodaragajānanāḥ}}, see: | |||

| * {{Harvard citation no brackets|Apte|1965|p=395}}.</ref> The word ''gaṇa'' when associated with Ganesha is often taken to refer to the gaṇas, a troop of semi-divine beings that form part of the retinue of ], Ganesha's father.<ref>For the derivation of the name and relationship with the {{IAST|gaṇas}}, see: {{Harvard citation no brackets|Martin-Dubost|1965|p=2}}</ref> The term more generally means a category, class, community, association, or corporation.{{Sfn|Apte|1965|p= 395}} Some commentators interpret the name "Lord of the {{IAST|Gaṇas}}" to mean "Lord of Hosts" or "Lord of created categories", such as the elements.<ref>The word ''gaṇa'' is interpreted in this metaphysical sense by Bhāskararāya in his commentary on the {{IAST|gaṇeśasahasranāma}}. See in particular commentary on verse 6 including names {{IAST|Gaṇeśvaraḥ}} and {{IAST|Gaṇakrīḍaḥ}} in: {{Harvnb|Śāstri Khiste|1991|pp=7–8}}.</ref> ''Ganapati'' ({{lang|sa|गणपति}}; {{IAST|gaṇapati}}), a synonym for ''Ganesha'', is a compound composed of ''{{IAST|gaṇa}}'', meaning "group", and ''{{IAST|pati}}'', meaning "ruler" or "lord".{{Sfn|Apte|1965|p= 395}} Though the earliest mention of the word ''Ganapati'' is found in ] 2.23.1 of the 2nd-millennium BCE '']'', it is uncertain that the Vedic term referred specifically to Ganesha.{{Sfn|Grimes|1995|pp=17–19, 201}}<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170202001602/https://sa.wikisource.org/%E0%A4%8B%E0%A4%97%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%B5%E0%A5%87%E0%A4%A6:_%E0%A4%B8%E0%A5%82%E0%A4%95%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%A4%E0%A4%82_%E0%A5%A8.%E0%A5%A8%E0%A5%A9|date=2 February 2017}}, Hymn 2.23.1, Wikisource, Quote: गणानां त्वा '''गणपतिं''' हवामहे कविं कवीनामुपमश्रवस्तमम् । ज्येष्ठराजं ब्रह्मणां ब्रह्मणस्पत आ नः शृण्वन्नूतिभिः सीद सादनम् ॥१॥; For translation, see {{Harvard citation no brackets|Grimes|1995|pp=17–19}}</ref> The '']'',<ref> | |||

| {{Citation | |||

| * {{Harvnb|Oka|1913|p=8}} for source text of {{IAST|Amarakośa}} 1.38 as {{IAST|vināyako vighnarājadvaimāturagaṇādhipāḥ – apyekadantaherambalambodaragajānanāḥ}}. | |||

| | last =Sathaye | |||

| * {{Harvnb|Śāstri|1978}} for text of ''{{IAST|Amarakośa}}'' versified as 1.1.38.</ref> an early Sanskrit lexicon, lists eight synonyms of ''Ganesha'': ''Vinayaka'', ''{{IAST|Vighnarāja}}'' (equivalent to ''Vighnesha''), ''{{IAST|Dvaimātura}}'' (one who has two mothers),<ref>Y. Krishan, ''{{IAST|Gaṇeśa}}: Unravelling an Enigma'', 1999, p. 6): "Pārvati who created an image of {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}} out of her bodily impurities but which became endowed with life after immersion in the ] of the Gangā. Therefore he is said to have two mothers—Pārvati and Gangā and hence called dvaimātura and also Gāngeya."</ref> ''{{IAST|Gaṇādhipa}}'' (equivalent to ''Ganapati'' and ''Ganesha''), ''Ekadanta'' (one who has one tusk), '']'', ''Lambodara'' (one who has a pot belly, or, literally, one who has a hanging belly), and ''Gajanana'' (''{{IAST|gajānana}}''), having the face of an ].<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Krishan|1999|p=6}}</ref> | |||

| | first =Avinash | |||

| | author2-link = | |||

| | publication-date = | |||

| | date = | |||

| | year = | |||

| | title =Amarakośa | |||

| | edition =Text converted to Unicode UTF-8 | |||

| | publication-place = | |||

| | place = | |||

| | publisher = | |||

| | url =http://www.sub.uni-goettingen.de/ebene_1/fiindolo/gretil/1_sanskr/6_sastra/2_lex/amark1hu.htm | |||

| | accessdate =5 September 2007 | |||

| }}.</ref><ref>For text of ''{{IAST|Amarakośa}}'' versified as 1.1.38, see: {{Harvnb|Śāstri|1978}}.</ref> | |||

| '''{{IAST| |

''Vinayaka'' ({{lang|sa|विनायक}}; ''{{IAST|vināyaka}}'') or ''Binayaka'' is a common name for Ganesha that appears in the {{IAST|Purāṇa}}s and in Buddhist Tantras.<ref name="Thapan">{{Harvard citation no brackets|Thapan|1997|p=20}}</ref> This name is reflected in the naming of the eight famous Ganesha temples in ] known as the '']'' ({{langx|mr|अष्टविनायक}}, {{IAST|aṣṭavināyaka}}).<ref>For the history of the ''{{IAST|aṣṭavināyaka}}'' sites and a description of pilgrimage practices related to them, see: {{Harvard citation no brackets|Mate|1962|pp=1–25}}</ref> The names ''Vighnesha'' ({{lang|sa|विघ्नेश}}; ''{{IAST|vighneśa}}'') and ''Vighneshvara'' ({{lang|sa|विघ्नेश्वर}}; ''{{IAST|vighneśvara}}'') (Lord of Obstacles)<ref name="Vighnesha">These ideas are so common that Courtright uses them in the title of his book, ''Ganesha: Lord of Obstacles, Lord of Beginnings''. For the name ''Vighnesha'', see: {{Harvnb|Courtright|1985|pp= 156, 213}}</ref> refers to his primary function in Hinduism as the master and remover of obstacles (''{{IAST|vighna}}'').<ref name="Krishanvii">For Krishan's views on Ganesha's dual nature see his quote: "{{IAST|Gaṇeśa}} has a dual nature; as Vināyaka, as a ''{{IAST|grāmadevatā}}'', he is ''{{IAST|vighnakartā}}'', and as {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}} he is ''{{IAST|vighnahartā}}'', a ''{{IAST|paurāṇic devatā}}''." ({{Harvard citation no brackets|Krishan|1999|p=viii}})</ref> | ||

| A prominent name for Ganesha in the ] is '' |

A prominent name for Ganesha in the ] is ''Pillai'' ({{langx|ta|பிள்ளை}}) or ''Pillaiyar'' ({{lang|ta|பிள்ளையார்}}).<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Martin-Dubost|1965|p=367}}.</ref> A. K. Narain differentiates these terms by saying that ''pillai'' means a "child" while ''pillaiyar'' means a "noble child". He adds that the words ''pallu'', ''pella'', and ''pell'' in the ] signify "tooth or tusk", also "] tooth or tusk".<ref>Narain, A. K. "{{IAST|Gaṇeśa}}: The Idea and the Icon".{{Harvard citation no brackets|Brown|1991|p=25}}</ref> Anita Raina Thapan notes that the ] ''pille'' in the name ''Pillaiyar'' might have originally meant "the young of the elephant", because the ] word ''pillaka'' means "a young elephant".<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Thapan|1997|p=62}}</ref> | ||

| In the ], Ganesha is known as ''Maha Peinne'' ({{lang|my|မဟာပိန္နဲ}}, {{IPA-my|məhà pèiɰ̃né|pron}}), derived from ] {{IAST|Mahā Wināyaka}} ({{lang|my|မဟာဝိနာယက}}).<ref>{{Citation |title=Myanmar-English Dictionary |year=1993 |publisher=Dunwoody Press |location=Yangon |isbn=978-1881265474 |url=http://sealang.net/burmese/dictionary.htm |access-date=20 September 2010 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100210001846/http://www.sealang.net/burmese/dictionary.htm |archive-date=10 February 2010 }}</ref> The widespread name of Ganesha in ] is Khanet (can be transliterated as Ganet), or the more official title of ''Phra Phi Khanet''.<ref>{{cite book|author=Justin Thomas McDaniel|title=The Lovelorn Ghost and the Magical Monk: Practicing Buddhism in Modern Thailand|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tMWrAgAAQBAJ |year=2013 | publisher=Columbia University Press |isbn=978-0231153775|pages=156–157}}</ref> The earliest images and mention lists Ganesha as a major deity in present-day Indonesia,<ref>{{citation|jstor=3351212|title=A Note on the Recently Discovered Gaṇeśa Image from Palembang, Sumatra|journal=Indonesia|volume=43|issue=43|pages=95–100|last1=Brown|first1=Robert L.|year=1987|doi=10.2307/3351212|hdl=1813/53865|hdl-access=free}}</ref> Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam dating to the 7th and 8th centuries,{{Sfn|Brown|1991|pp=176, 182, Note: some scholars suggest adoption of Ganesha by the late 6th century CE, see p. 192 footnote 7}} and these mirror Indian examples of the 5th century or earlier.{{Sfn|Brown|1991|p=190}} In ]n, among ] Buddhists, he is known as ''Gana deviyo'', and revered along with ], ], ] and other deities.<ref>{{cite book|author=John Clifford Holt |title=Buddha in the Crown : Avalokitesvara in the Buddhist Traditions of Sri Lanka: Avalokitesvara in the Buddhist Traditions of Sri Lanka |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=aT3AMR8g1gEC|year=1991|publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0195362466|pages=6, 100, 180–181}}</ref> | |||

| ==Iconography== | |||

| {{seealso|Sritattvanidhi}} | |||

| ] of ] in the 13th century.]] | |||

| == Iconography == | |||

| Ganesha is a popular figure in ].<ref>Pal, p. ix.</ref> Unlike some deities, representations of Ganesha show wide variation with distinct patterns changing over time.<ref>For a comprehensive review of iconography abundantly illustrated with pictures, see: Martin-Dubost.</ref><ref>For a survey of iconography with emphasis on developmental themes, well-illustrated with plates, see Chapter X, "Development of the Iconography of Gaņeśa", in: {{Harvnb|Krishan|1999|pp=87-100}}.</ref><ref>For a richly illustrated collection of studies on specific aspects of Ganesha with a focus on art and iconography, see: Pal.</ref> He may be portrayed standing, dancing, heroically taking action against demons, playing with his family as a boy, sitting down, or engaging in a range of contemporary situations. | |||

| ]-style, ]]] | |||

| Ganesha is a popular figure in ].<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Metcalf|Metcalf|p=vii}}</ref> Unlike those of some deities, representations of Ganesha show wide variations and distinct patterns changing over time.<ref>* {{Harvard citation no brackets|Martin-Dubost|1965}}, for a comprehensive review of iconography abundantly illustrated with pictures. | |||

| Ganesha images were prevalent in many parts of India by the sixth century.<ref>Brown, p. 175.</ref> The figure shown to the right is typical of Ganesha statuary from 900-1200, after Ganesha had been well-established as an independent deity with his own sect. This example <!-- REQUEST: is it possible to get a photo of the statue referred to by Martin-Dubost or Pal (which is much larger), to eliminate this confusion? -->features some of Ganesha's common iconographic elements. A virtually identical statue has been dated between 973-1200 by Paul Martin-Dubost,<ref>Martin-Dubost, p. 213. In the upper right corner, the statue is dated as (973–1200).</ref> and another similar statue is dated circa twelfth century by Pratapaditya Pal.<ref>Pal, p. vi. The picture on this page depicts a stone statue in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art that is dated as circa twelfth century. Pal shows an example of this form dated ''circa'' thirteenth century on p. viii.</ref> Ganesha has the head of an elephant and a big belly. This statue has four arms, which is common in depictions of Ganesha. He holds his own broken tusk in his lower-right hand and holds a delicacy, which he samples with his trunk, in his lower-left hand. The motif of Ganesha turning his trunk sharply to his left to taste a sweet in his lower-left hand is a particularly archaic feature.<ref>Brown, p. 176.</ref> A more primitive statue in one of the ] with this general form has been dated to the seventh century.<ref>See photograph 2, "Large Ganesh", in: Pal, p. 16.</ref> Details of the other hands are difficult to make out on the statue shown; in the standard configuration, Ganesha typically holds an axe or a ] in one upper arm and a noose in the other upper arm as symbols of his ability to cut through obstacles or to create them as needed. | |||

| * Chapter X, "Development of the Iconography of {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}}", in: {{Harvnb|Krishan|1999|pp=87–100}}, for a survey of iconography with emphasis on developmental themes, well-illustrated with plates. | |||

| * {{Harvard citation no brackets|Pal|1995}}, for a richly illustrated collection of studies on specific aspects of Ganesha with a focus on art and iconography.</ref> He may be portrayed standing, dancing, heroically taking action against demons, playing with his family as a boy, sitting down on an elevated seat, or engaging in a range of contemporary situations. | |||

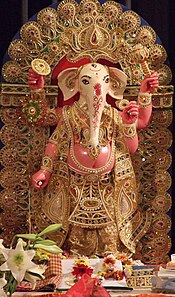

| Ganesha images were prevalent in many parts of ] by the 6th century.<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Brown|1991|p=175}}</ref> The 13th century statue pictured is typical of Ganesha statuary from 900 to 1200, after Ganesha had been well-established as an independent deity with his own sect. This example features some of Ganesha's common iconographic elements. A virtually identical statue has been dated between 973 and 1200 by Paul Martin-Dubost,<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Martin-Dubost|1997}}, p. 213. In the upper right corner, the statue is dated as (973–1200).</ref> and another similar statue is dated 12th century by Pratapaditya Pal.<ref>Pal, p. vi. The picture on this page depicts a stone statue in the ] of Art that is dated as c. 12th century. Pal shows an example of this form dated c. 13th century on p. viii.</ref> Ganesha has the head of an elephant and a big belly. This statue has four arms, which is common in depictions of Ganesha. He holds his own broken tusk in his lower-right hand and holds a delicacy, which he samples with his trunk, in his lower-left hand. The motif of Ganesha turning his trunk sharply to his left to taste a sweet in his lower-left hand is a particularly archaic feature.<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Brown|1991|p=176}}</ref> A more primitive statue in one of the ] with this general form has been dated to the 7th century.<ref>See photograph 2, "Large Ganesh", in: {{Harvard citation no brackets|Pal|1995|p=16}}</ref> Details of the other hands are difficult to make out on the statue shown. In the standard configuration, Ganesha typically holds an ] or a ] in one upper arm and a ] (]) in the other upper arm. In rare instances, he may be depicted with a human head.{{refn|group=note|For the human-headed form of Ganesha in: | |||

| The influence of this old constellation of iconographic elements can still be seen in contemporary representations of Ganesha. In one modern form, the only variation from these old elements is that the lower-right hand does not hold the broken tusk but rather is turned toward the viewer in a gesture of protection or "no fear" (abhaya ]).<ref>Martin-Dubost, pp. 197-198.</ref><ref>For an example of a large image of this type being carried in a festival procession, see photograph 9, "Ganesh images being taken for immersion", in: Pal, pp. 22-23. For two similar statues about to be immersed, see: Pal, p. 25.</ref> The same combination of four arms and attributes occurs in statues of Ganesha dancing,<ref>For many examples of Ganesha dancing, see: Pal, pp. 41-64.</ref> which is a very popular theme.<ref>For popularity of the dancing form, see: Brown, p. 183.</ref> | |||

| * ] temple near ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://agasthiar.org/a/adinmv.htm|title=Adi Vinayaka - The Primordial Form of Ganesh.|website=agasthiar.org|access-date=28 December 2017}}</ref> | |||

| * ], see {{Harvard citation no brackets|Brown|1991|p=10}} | |||

| * ].<ref>{{cite news|date=10 October 2003|title=Vinayaka in unique form|work=]|url=http://www.thehindu.com/fr/2003/10/10/stories/2003101001411200.htm|archive-url=https://archive.today/20150501000652/http://www.thehindu.com/fr/2003/10/10/stories/2003101001411200.htm|url-status=dead|archive-date=1 May 2015|access-date=30 April 2015}}</ref> | |||

| * ].<ref>Catlin, Amy; "Vātāpi Gaṇapatim": Sculptural, Poetic, and Musical Texts in the Hymn to Gaṇeśa" in {{Harvard citation no brackets|Brown|1991|pp=146, 150}}</ref>}} | |||

| The influence of this old constellation of iconographic elements can still be seen in contemporary representations of Ganesha. In one modern form, the only variation from these old elements is that the lower-right hand does not hold the broken tusk but is turned towards the viewer in a gesture of protection or fearlessness (Abhaya ]).<ref>In: | |||

| ===Common attributes=== | |||

| * {{Harvard citation no brackets|Martin-Dubost|1965|pp=197–198}} | |||

| {{For|stories mentioning Ganesha's attributes|Mythological anecdotes of Ganesha}} | |||

| * photograph 9, "Ganesh images being taken for immersion", in: {{Harvard citation no brackets|Pal|1995|pp=22–23}}. For an example of a large image of this type being carried in a festival procession. | |||

| * {{Harvard citation no brackets|Pal|1995|p=25}}, For two similar statues about to be immersed.</ref> The same combination of four arms and attributes occurs in statues of Ganesha dancing, which is a very popular theme.<ref>In: | |||

| * {{Harvard citation no brackets|Pal|1995|pp=41–64}}. For many examples of Ganesha dancing. | |||

| * {{Harvard citation no brackets|Brown|1991|p=183}} For the popularity of the dancing form.</ref> | |||

| === Common attributes === | |||

| ] school (circa 1810).<ref>Four-armed {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}}. Miniature of Nurpur school, circa 1810. Museum of Chandigarh. For this image see: Martin-Dubost (1997), p. 64, which describes it as follows: "On a terrace leaning against a thick white bolster, {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}} is seated on a bed of pink lotus petals arranged on a low seat to the back of which is fixed a parasol. The elephant-faced god, with his body entirely red, is dressed in a yellow ] and a yellow scarf fringed with blue. Two white mice decorated with a pretty golden necklace salute {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}} by joining their tiny feet together. {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}} counts on his rosary in his lower right hand; his two upper hands brandish an axe and an elephant goad; his fourth hand holds the broken left tusk."</ref>]] | |||

| {{for|thirty-two popular iconographic forms of Ganesha|Thirty-two forms of Ganesha}} | |||

| ] school (circa 1810)<ref>Four-armed {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}}. Miniature of Nurpur school, circa 1810. Museum of Chandigarh. For this image see: Martin-Dubost (1997), p. 64, which describes it as follows: "On a terrace leaning against a thick white bolster, {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}} is seated on a bed of pink lotus petals arranged on a low seat to the back of which is fixed a parasol. The elephant-faced god, with his body entirely red, is dressed in a yellow ] and a yellow scarf fringed with blue. Two white mice decorated with a pretty golden necklace salute {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}} by joining their tiny feet together. {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}} counts on his rosary in his lower right hand; his two upper hands brandish an axe and an elephant goad; his fourth hand holds the broken left tusk."</ref>]] | |||

| Ganesha has been represented with the head of an elephant since the early stages of his appearance in Indian art.<ref>Nagar, p. 77.</ref> Puranic myths provide many explanations for how he got his elephant head.<ref>Brown, p. 3.</ref> One of his popular forms (called ]) has five elephant heads, and other less-common variations in the number of heads are known.<ref>Nagar, p. 78.</ref> | |||

| Ganesha has been represented with the head of an elephant since the early stages of his appearance in Indian art.<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Nagar|1992|p=77}}</ref> Puranic myths provide many explanations for how he got his elephant head.<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Brown|1991|p=3}}</ref> One of his popular forms, '']'', has five elephant heads, and other less-common variations in the number of heads are known.<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Nagar|1992|p=78}}</ref> While some texts say that Ganesha was born with an elephant head, he acquires the head later in most stories.<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Brown|1991|p=76}}</ref> The most recurrent motif in these stories is that Ganesha was created by ] using clay to protect her and ] beheaded him when Ganesha came between Shiva and Parvati. Shiva then replaced Ganesha's original head with that of an elephant.<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Brown|1991|p=77}}</ref> Details of the battle and where the replacement head came from vary from source to source.<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Brown|1991|pp=77–78}}</ref> Another story says that Ganesha was created directly by Shiva's laughter. Because Shiva considered Ganesha too alluring, he gave him the head of an elephant and a protruding belly.<ref>For creation of Ganesha from Shiva's laughter and subsequent curse by Shiva, see ''Varaha Purana'' 23.17 as cited in {{Harvard citation no brackets|Brown|1991|p=77}}.</ref> | |||

| Ganesha's earliest name was |

Ganesha's earliest name was ''Ekadanta'' (One Tusked), referring to his single whole tusk, the other being broken.{{Sfn|Getty|1936|p= 1}} Some of the earliest images of Ganesha show him holding his broken tusk.<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Heras|1972|p=29}}</ref> The importance of this distinctive feature is reflected in the '']'', which states that the name of Ganesha's second ] is Ekadanta.<ref>Granoff, Phyllis. "{{IAST|Gaṇeśa}} as Metaphor". {{Harvard citation no brackets|Brown|1991|pp=92–94}}</ref> Ganesha's protruding belly appears as a distinctive attribute in his earliest statuary, which dates to the Gupta period (4th to 6th centuries).<ref>"Ganesha in Indian Plastic Art" and ''Passim''. {{Harvard citation no brackets|Nagar|1992|p=78}}</ref> This feature is so important that according to the ''Mudgala Purana'', two different incarnations of Ganesha use names based on it: ''Lambodara'' (Pot Belly, or, literally, Hanging Belly) and ''Mahodara'' (Great Belly).<ref>Granoff, Phyllis. "{{IAST|Gaṇeśa}} as Metaphor". {{Harvard citation no brackets|Brown|1991|p=76}}</ref> Both names are Sanskrit compounds describing his belly (IAST: ''{{IAST|udara}}'').<ref>For translation of ''Udara'' as "belly" see: {{Harvard citation no brackets|Apte|1965|p=268}}</ref> The '']'' says that Ganesha has the name Lambodara because all the universes (i.e., ]; IAST: ''{{IAST|brahmāṇḍas}}'') of the past, present, and future are present in him.<ref> | ||

| * ''Br. P.'' 2.3.42.34 | |||

| * {{Harvard citation no brackets|Thapan|1997|p=200}}, For a description of how a variant of this story is used in the ''Mudgala Purana'' 2.56.38–9</ref> | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| Ganesha's protruding belly appears as a distinctive attribute in his earliest statuary, which dates to the Gupta period (fourth to sixth centuries).<ref>"Ganesha in Indian Plastic Art" and ''Passim''. Nagar, p. 101.</ref> This feature is so important that according to the ''Mudgala Purana'' two different incarnations of Ganesha use names based on it, '''Lambodara''' ("Pot Belly", or literally "Hanging Belly") and '''Mahodara''' ("Great Belly").<ref>Granoff, Phyllis. "{{IAST|Gaṇeśa}} as Metaphor". Brown, p. 91.</ref> Both names are Sanskrit compounds describing his belly (Sanskrit: ''{{IAST|udara}}'').<ref>For translation of ''udara'' as "belly" see: Apte, p. 268.</ref><!-- CLARIFY: if Lambodara is the name of both Ganesha and his avatar, please clarify as you have done in the preceding paragraph.--> The ''Brahmanda Purana'' says that he has the name Lambodara because all the universes (i.e., ]; Sanskrit ''{{IAST|brahmāṇḍas}}'') of the past, present, and future are present in Ganesha.<ref>''Br. P.'' 2.3.42.34</ref><ref>For a description of how a variant of this story is used in the ''Mudgala Purana'' 2.56.38-9, see: Thapan, p. 200.</ref> | |||

| | align = left | |||

| | image1 = 6th century Ganesha Badami Caves.jpg | |||

| | width1 = 185 | |||

| | alt1 = | |||

| | caption1 = 6th-century Ganesha Statue in ], depicting Ganesha with two arms | |||

| | image2 = Ganesha in Bronze Vijayanagar Empire 13th century II.jpg | |||

| | width2 = 157 | |||

| | alt2 = | |||

| | caption2 = Ganesha in Bronze from 13th century ], depicting Ganesha with four arms | |||

| | footer = | |||

| }} | |||

| The number of Ganesha's arms varies; his best-known forms have between two and sixteen arms.<ref>For an iconographic chart showing number of arms and attributes classified by source and named form, see: {{Harvard citation no brackets|Nagar|1992|pp=191–195}} Appendix I.</ref> Many depictions of Ganesha feature four arms, which is mentioned in Puranic sources and codified as a standard form in some iconographic texts.<ref>For history and prevalence of forms with various arms and the four-armed form as one of the standard types see: {{Harvnb|Krishan|1999|p=89}}.</ref> His earliest images had two arms.<ref> | |||

| * {{Harvnb|Krishan|1999|p=89}}, For two-armed forms as an earlier development than four-armed forms. | |||

| * {{Harvard citation no brackets|Brown|1991|p=103}} Maruti Nandan Tiwari and Kamal Giri say in "Images of {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}} In Jainism" that the presence of only two arms on a Ganesha image points to an early date.</ref> Forms with 14 and 20 arms appeared in Central India during the 9th and the 10th centuries.<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Martin-Dubost|1965|p=120}}.</ref> The serpent is a common feature in Ganesha iconography and appears in many forms.<ref> | |||

| * {{Harvard citation no brackets|Martin-Dubost|1965|p=202}}, For an overview of snake images in Ganesha iconography. | |||

| * {{Harvnb|Krishan|1999|pp=50–53}}, For an overview of snake images in Ganesha iconography.</ref> According to the ''Ganesha Purana'', Ganesha wrapped the serpent ] around his neck.<ref>''']''' | |||

| * {{Harvard citation no brackets|Martin-Dubost|1965|p=202}}. For the ] references for {{IAST|Vāsuki}} around the neck and use of a serpent-throne. | |||

| * {{Harvnb|Krishan|1999|pp=51–52}}. For the story of wrapping {{IAST|Vāsuki}} around the neck and {{IAST|Śeṣa}} around the belly and for the name in his sahasranama as {{IAST|Sarpagraiveyakāṅgādaḥ}} ("Who has a serpent around his neck"), which refers to this standard iconographic element.</ref> Other depictions of snakes include use as a sacred thread (IAST: ''{{IAST|yajñyopavīta}}'')<ref>* {{Harvard citation no brackets|Martin-Dubost|1965|p=202}}. For the text of a stone inscription dated 1470 identifying Ganesha's sacred thread as the serpent {{IAST|Śeṣa}}. | |||

| * {{Harvard citation no brackets|Nagar|1992|p=92}}. For the snake as a common type of ''{{IAST|yajñyopavīta}}'' for Ganesha.</ref> wrapped around the stomach as a belt, held in a hand, coiled at the ankles, or as a throne. Upon Ganesha's forehead may be a ] or the sectarian mark (IAST: {{IAST|]}}), which consists of three horizontal lines.<ref>* {{Harvard citation no brackets|Nagar|1992|p=81}}. ''tilaka'' with three horizontal lines. | |||

| * the ''{{IAST|dhyānam}}'' in: Sharma (1993 edition of ''Ganesha Purana'') I.46.1. For Ganesa visualized as ''{{IAST|trinetraṁ}}'' (having three eyes).</ref> The ''Ganesha Purana'' prescribes a ''tilaka'' mark as well as a crescent moon on the forehead.<ref>* {{Harvard citation no brackets|Nagar|1992|p=81}}. For a citation to ''Ganesha Purana'' I.14.21–25 and For a citation to ''Padma Purana'' as prescribing the crescent for decoration of the forehead of Ganesha | |||

| * {{Harvard citation no brackets|Bailey|1995|pp=198–199}}. For the translation of ''Ganesha Purana'' I.14, which includes a meditation form with the moon on forehead.</ref> A distinct form of Ganesha called ''Bhalachandra'' (IAST: ''{{IAST|bhālacandra}}''; "Moon on the Forehead") includes that iconographic element.<ref> | |||

| * {{Harvard citation no brackets|Nagar|1992|p=81}} For Bhālacandra as a distinct form worshipped. | |||

| * Sharma (1993 edition of Ganesha Purana) I.46.15. For the name Bhālacandra appearing in the Ganesha Sahasranama | |||

| </ref> | |||

| Ganesha is often described as red in colour.<ref name="Nagar, Preface">{{Cite book|last=Civarāman̲|first=Akilā|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pyb8oAEACAAJ|title=Sri Ganesha Purana|date=2014|publisher=Giri Trading Agency|isbn=978-81-7950-629-5|language=en}}</ref> Specific colours are associated with certain forms.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Martin-Dubost|first=Paul|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=H5DjAAAAMAAJ|title=Gaṇeśa, the Enchanter of the Three Worlds|date=1997|publisher=Franco-Indian Research|isbn=978-81-900184-3-2|pages=412–416|language=en}}</ref> Many examples of color associations with specific meditation forms are prescribed in the Sritattvanidhi, a treatise on ]. For example, white is associated with his representations as ''Heramba-Ganapati'' and ''Rina-Mochana-Ganapati'' (Ganapati Who Releases from Bondage).<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Martin-Dubost|1997|pp=224–228}}</ref> ''Ekadanta-Ganapati'' is visualised as blue during meditation in that form.<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Martin-Dubost|1997|p=228}}</ref> | |||

| The number of Ganesha's arms varies; his best-known forms have between two and sixteen arms.<ref>For an inconographical chart showing number of arms and attributes classified by source and named form, see: Nagar, pp. 191-195. Appendix I.</ref> Many depictions of Ganesha feature four arms, which is mentioned in Puranic sources and codified as a standard form in some iconographic texts.<ref>For history and prevalence of forms with various arms, and the four-armed form as one of the standard types, see: {{Harvnb|Krishan|1999|p=89}}.</ref> His earliest images had two arms.<ref>For two-armed forms as an earlier development than four-armed forms, see: {{Harvnb|Krishan|1999|p=89}}.</ref><ref>Maruti Nandan Tiwari and Kamal Giri say in "Images of {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}} In Jainism" that the presence of only two arms on a Ganesha image points to an early date. See: Brown, p. 103.</ref> Forms with fourteen and twenty arms appeared in Central India during the ninth and tenth centuries.<ref>Martin-Dubost, p. 120.</ref> | |||

| === Vahanas === | |||

| The serpent is a common feature in Ganesha iconography and appears in many forms.<ref>For an overview of snake images in Ganesha iconography, see: Martin-Dubost, p. 202.</ref><ref>For an overview of snake images in Ganesha iconography, see: {{Harvnb|Krishan|1999|pp=50-53}}.</ref> According to the ''Ganesha Purana'', Ganesha wrapped the serpent ] around his neck.<ref>For the Ganesha Purana references for {{IAST|Vāsuki}} around the neck and use of a serpent-throne, see: Martin-Dubost, p. 202.</ref><ref>For the story of wrapping {{IAST|Vāsuki}} around the neck and {{IAST|Śeṣa}} around the belly and for the name in his sahasranama as {{IAST|Sarpagraiveyakāṅgādaḥ}} ("Who has a serpent around his neck"), which refers to this standard iconographic element, see: {{Harvnb|Krishan|1999|pp=51-52}}.</ref> Other common depictions of snakes include use as a sacred thread (Sanskrit: ''{{IAST|yajñyopavīta}}'')<ref>For text of a stone inscription dated 1470 identifying Ganesha's sacred thread as the serpent {{IAST|Śeṣa}}, see: Martin-Dubost, p. 202.</ref><ref>For the snake as a common type of ''{{IAST|yajñyopavīta}}'' for Ganesha, see: Nagar, p. 92.</ref> wrapped around the stomach as a belt, held in a hand, coiled at the ankles, or as a throne. Upon Ganesha's forehead there may be a third eye or the ] sectarian mark (Sanskrit: '']''), three horizontal lines.<ref>For third eye or Shaiva ''tilaka'' with three horizontal lines, see: Nagar, p. 81.</ref><ref>For Ganesa visualized as ''{{IAST|trinetraṁ}}'' (having three eyes), see the ''{{IAST|dhyānam}}'' in: Sharma (1993 edition of ''Ganesha Purana'') I.46.1.</ref> The ''Ganesha Purana'' prescribes a ''tilaka'' mark as well as a crescent moon on the forehead.<ref>For citation to ''Ganesha Purana'' I.14.21-25 see: Nagar, p. 81.</ref><ref>For translation of ''Ganesha Purana'' I.14, which includes a meditation form with moon on forehead, see: Bailey (1995), pp. 198-199.</ref><ref>For citation to ''Padma Purana'' as prescribing the crescent for decoration of the forehead of Ganesha, see: Nagar, p. 81.</ref> A distinct form called '''{{IAST|Bhālacandra}}''' ("Moon on the Forehead") includes that iconographic element.<ref>For {{IAST|Bhālacandra}} as a distinct form worshipped, see: Nagar, p. 81.</ref><ref>For the name {{IAST|Bhālacandra}} appearing in the Ganesha Sahasranama see: Sharma (1993 edition of ''Ganesha Purana'') I.46.15.</ref> | |||

| ] ''mūṣaka'' the rat, c. 1820]] | |||

| The earliest Ganesha images are without a ] (mount/vehicle).<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Krishan|1999|pp=47–48, 78}}</ref> Of ], Ganesha uses a ] (shrew) in five of them, a lion in his incarnation as ''Vakratunda'', a peacock in his incarnation as ''Vikata'', and ], the divine serpent, in his incarnation as ''Vighnaraja''.<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Krishan|1981–1982|p=49}}</ref> ''Mohotkata'' uses a ], ''{{IAST|Mayūreśvara}}'' uses a peacock, ''Dhumraketu'' uses a ], and ''Gajanana'' uses a mouse, in the ] listed in the ''Ganesha Purana''. Jain depictions of Ganesha show his vahana variously as a ], ], ], ram, or ].<ref> | |||

| * {{Harvard citation no brackets|Krishan|1999|pp=48–49}} | |||

| The colors most often associated with Ganesha are red <ref>Nagar, Preface.</ref> and yellow, but specific other colors are associated with certain forms.<ref>"The Colors of Ganesha". Martin-Dubost, pp. 221-230.</ref> Many examples of color associations with specific meditation forms are prescribed in the ], which is a treatise on ] that includes a section on variant forms of Ganesha. For example, white is associated with his representations as Heramba-Ganapati <!-- TRANSLATION? -->and Rina-Mochana-Ganapati ("Ganapati Who Releases From Bondage").<ref>Martin-Dubost, pp. 224-228</ref> Ekadanta-Ganapati is visualized as blue during meditation on that form.<ref>Martin-Dubost, p. 228.</ref> | |||

| * {{Harvard citation no brackets|Bailey|1995|p=348}}. For the Ganesha Purana story of {{IAST|Mayūreśvara}} with the peacock mount (GP I.84.2–3) | |||

| * Maruti Nandan Tiwari and Kamal Giri, "Images of {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}} In Jainism", in: {{Harvard citation no brackets|Brown|1991|pp=101–102}}.</ref> | |||

| Ganesha is often shown riding on or attended by a ].<ref>* {{Harvard citation no brackets|Nagar|1992}}. Preface. | |||

| ===Vahanas of Ganesha=== | |||

| * {{Harvard citation no brackets|Martin-Dubost|1965|pp=231–244}}.</ref> Martin-Dubost says that the rat began to appear as the principal vehicle in sculptures of Ganesha in central and western India during the 7th century; the rat was always placed close to his feet.<ref>See note on figure 43 in: {{Harvard citation no brackets|Martin-Dubost|1997|p=144}}.</ref> The mouse as a mount first appears in written sources in the '']'' and later in the ''Brahmananda Purana'' and ''Ganesha Purana'', where Ganesha uses it as his vehicle in his last incarnation.<ref>Citations to ''Matsya Purana'' 260.54, ''Brahmananda Purana Lalitamahatmya'' XXVII, and '']'' 2.134–136 are provided by: {{Harvard citation no brackets|Martin-Dubost|1997|p=231}}.</ref> The ] includes a meditation verse on Ganesha that describes the mouse appearing on his flag.<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Martin-Dubost|1997|p=232}}.</ref> The names ''{{IAST|Mūṣakavāhana}}'' (mouse-mount) and ''{{IAST|Ākhuketana}}'' (rat-banner) appear in the '']''.<ref>For {{IAST|Mūṣakavāhana}} see v. 6. For Ākhuketana see v. 67. In: ''{{IAST|Gaṇeśasahasranāmastotram: mūla evaṁ srībhāskararāyakṛta 'khadyota' vārtika sahita}}''. ({{IAST|Prācya Prakāśana: Vārāṇasī}}, 1991). Source text with a commentary by {{IAST|]}} in Sanskrit.</ref> | |||

| The mouse is interpreted in several ways. According to Grimes, "Many, if not most of those who interpret {{IAST|Gaṇapati}}'s mouse, do so negatively; it symbolizes '']'' as well as desire".<ref>For a review of different interpretations, and quotation, see: {{Harvard citation no brackets|Grimes|1995|p=86}}.</ref> Along these lines, Michael Wilcockson says it symbolises those who wish to overcome desires and be less selfish.<ref>''A Student's Guide to AS Religious Studies for the OCR Specification,'' by Michael Wilcockson, p. 117</ref> Krishan notes that the rat is destructive and a menace to crops. The Sanskrit word ''{{IAST|mūṣaka}}'' (mouse) is derived from the root ''{{IAST|mūṣ}}'' (stealing, robbing). It was essential to subdue the rat as a destructive pest, a type of ''vighna'' (impediment) that needed to be overcome. According to this theory, showing Ganesha as master of the rat demonstrates his function as ''Vigneshvara'' (Lord of Obstacles) and gives evidence of his possible role as a folk ''grāma-devatā'' (village deity) who later rose to greater prominence.<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Krishan|1999|pp=49–50}}</ref> Martin-Dubost notes a view that the rat is a symbol suggesting that Ganesha, like the rat, penetrates even the most secret places.<ref>* {{Harvard citation no brackets|Martin-Dubost|1965|p=231}} | |||

| The earliest Ganesha images are without a ] (mount).<ref>Krishan, pp. 48, 89, 92.</ref> Of ] described in the ''Mudgala Purana'', Ganesha has a mouse in five of them, uses a lion in his incarnation as Vakratunda, a peacock in his incarnation of Vikata, and ], the divine serpent, in his incarnation as Vighnaraja.<ref>Krishan, p. 49.</ref> Of the ] listed in the ''Ganesha Purana'', Mohotkata has a lion, {{IAST|Mayūreśvara}} has a peacock, Dhumraketu has a horse, and Gajanana has a rat.<ref>Krishan, pp. 48-49.</ref><ref>For the Ganesha Purana story of {{IAST|Mayūreśvara}} with the peacock mount (GP I.84.2-3), see: Bailey (1995), p. 348.</ref> Jain depictions of Ganesha show his vahana variously as a mouse,<ref>Maruti Nandan Tiwari and Kamal Giri, "Images of {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}} In Jainism", in: Brown, pp.101.</ref> an elephant,<ref>Maruti Nandan Tiwari and Kamal Giri, "Images of {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}} In Jainism", in: Brown, pp.102.</ref> a tortoise, a ram, or a peacock.<ref>Krishan, p. 49.</ref> | |||

| * Rocher, Ludo. "{{IAST|Gaṇeśa}}<nowiki/>'s Rise to Prominence in Sanskrit Literature", in: {{Harvard citation no brackets|Brown|1991|p=73}}. For mention of the interpretation that "the rat is 'the animal that finds its way to every place,'"</ref> | |||

| == Features == | |||

| ====Mouse or rat as vahana==== | |||

| {{CSS image crop|Image=Dagdusheth Ganpati 02.JPG|bSize=400|cWidth=213|cHeight=250|oTop=40|oLeft=50|Description=The central icon of Ganesha at the ].|Align=left}} | |||

| ], ]. Note the red flowers offered by devotees.]] | |||

| === Removal of obstacles === | |||

| Ganesha is often shown riding on or attended by a ] or ].<ref>Nagar. Preface.</ref><ref>Martin-Dubost, pp. 231-244.</ref> Martin-Dubost says that in central and western India the rat began to appear as the principal vehicle in sculptures of {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}} in the seventh century A.D., where the rat was always placed close to his feet.<ref>See note on figure 43 in: Martin-Dubost, p. 144.</ref> The mouse as a ] first appears in written sources in the '']'' and later in the ''Brahmananda Purana'' and ''Ganesha Purana'', where Ganesha uses it as his vehicle only in his last incarnation.<ref>Citations to ''Matsya Purana'' 260.54, ''Brahmananda Purana Lalitamahatmya'' XXVII, and ''Ganesha Purana'' 2.134-136 are provided by: Martin-Dubost, p. 231.</ref> The ] includes a meditation verse on Ganesha that describes the mouse appearing on his flag.<ref>Martin-Dubost, p. 232.</ref> The names {{IAST|Mūṣakavāhana}} ("Mouse-mount") and {{IAST|Ākhuketana}} ("Rat-banner") appear in the '']''.<ref>For {{IAST|Mūṣakavāhana}} see v. 6. For Ākhuketana see v. 67. In: ''{{IAST|Gaṇeśasahasranāmastotram: mūla evaṁ srībhāskararāyakṛta ‘khadyota’ vārtika sahita}}''. ({{IAST|Prācya Prakāśana: Vārāṇasī}}, 1991). Source text with a commentary by {{IAST|Bhāskararāya}} in Sanskrit.</ref> | |||

| Ganesha is ''Vighneshvara'' (''Vighnaraja,'' ] – ''Vighnaharta)'', the Lord of Obstacles, both of a material and spiritual order.<ref>"Lord of Removal of Obstacles", a common name, appears in the title of Courtright's ''{{IAST|Gaṇeśa}}: Lord of Obstacles, Lord of Beginnings''. For equivalent Sanskrit names ''Vighneśvara'' and ''Vighnarāja'', see: {{Harvard citation no brackets|Mate|1962|p=136}}</ref> He is popularly worshipped as a remover of obstacles, though traditionally he also places obstacles in the path of those who need to be checked. Hence, he is often worshipped by the people before they begin anything new.<ref>{{Cite web| url=https://chopra.com/articles/ganesha-the-remover-of-obstacles| title=Ganesha: The Remover of Obstacles| date=31 May 2016| access-date=29 August 2019| archive-date=31 October 2019| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191031193717/https://chopra.com/articles/ganesha-the-remover-of-obstacles| url-status=dead}}</ref> Paul Courtright says that Ganesha's ''dharma'' and his raison d'être is to create and remove obstacles.<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Courtright|1985|p=136}}</ref> | |||

| Krishan notes that some of Ganesha's names reflect shadings of multiple roles that have evolved over time.<ref name="Krishanvii"/> Dhavalikar ascribes the quick ascension of Ganesha in the Hindu pantheon, and the emergence of the {{IAST|Ganapatyas}}, to this shift in emphasis from ''{{IAST|vighnakartā}}'' (obstacle-creator) to ''{{IAST|vighnahartā}}'' (obstacle-averter).<ref>For Dhavilkar's views on Ganesha's shifting role, see Dhavalikar, M.K. "{{IAST|Gaṇeśa}}: Myth and reality" in {{Harvnb|Brown|1991|p=49}}</ref> However, both functions continue to be vital to his character.<!-- , as Robert Brown explains, "even after the ] is well-defined, in art ] remained predominantly important for his dual role as creator and remover of obstacles, thus having both a negative and a positive aspect". --><ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Brown|1991|p=6}}</ref> | |||

| There are a variety of interpretations regarding what the mouse symbolizes. According to Grimes, "Many, if not most of those who interpret {{IAST|Gaṇapati}}'s mouse, do so negatively; it symbolizes '']'' as well as desire."<ref>For a review of different interpretations, and quotation, see: Grimes (1995), p. 86.</ref> Along these lines, Michael Wilcockson says it symbolizes those who wish to overcome desires and be less selfish.<ref>''A Student's Guide to AS Religious Studies for the OCR Specification,'' by Michael Wilcockson, pg.117</ref> Krishan notes that the rat is a destructive creature and a menace to crops. The Sanskrit word ''{{IAST|mūṣaka}}'' (mouse) is derived from the root ''{{IAST|mūṣ}}'' which means "stealing, robbing." It was essential to subdue the rat as a destructive pest, a type of ''vighna'' (impediment) that needed to be overcome. According to this theory, showing Ganesha as master of the rat demonstrates his function as Vigneshvara and gives evidence of his possible role as a folk ''grāmata-devatā'' (village deity) who later rose to greater prominence.<ref>Krishnan pp. 49-50.</ref> Martin-Dubost notes a view that the rat is a symbol suggesting that Ganesha, like the rat, penetrates even the most secret places.<ref>Martin-Dubost, p. 231.</ref><ref>For mention of the interpretation that "the rat is 'the animal that finds its way to every place,' " see: Rocher, Ludo. "{IAST|Gaṇeśa}}'s Rise to Prominence in Sanskrit Literature," in: Brown (1991), p. 73.</ref> | |||

| === Buddhi (Intelligence) === | |||

| ==Associations== | |||

| Ganesha is considered to be the Lord of letters and learning.<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Nagar|1992|p=5}}.</ref> In Sanskrit, the word '']'' is an active noun that is variously translated as intelligence, wisdom, or intellect.{{Sfn|Apte|1965|p= 703}} The concept of buddhi is closely associated with the personality of Ganesha, especially in the Puranic period, when many stories stress his cleverness and love of intelligence. One of Ganesha's names in the '']'' and the '']'' is ''Buddhipriya''.<ref>''Ganesha Purana'' I.46, v. 5 of the Ganesha Sahasranama section in GP-1993, Sharma edition. It appears in verse 10 of the version as given in the Bhaskararaya commentary.</ref> This name also appears in a list of 21 names at the end of the ''Ganesha Sahasranama'' that Ganesha says are especially important.<ref>Sharma edition, GP-1993 I.46, verses 204–206. The Bailey edition uses a variant text, and where Sharma reads ''Buddhipriya'', Bailey translates ''Granter-of-lakhs.''</ref> The word ''priya'' can mean "fond of", and in a marital context it can mean "lover" or "husband",<ref>Practical Sanskrit Dictionary By ]; p. 187 (''priya''); Published 2004; ] Publ; {{ISBN|8120820002}}</ref> so the name may mean either "Fond of Intelligence" or "Buddhi's Husband".<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Krishan|1999|pp=60–70}}p. discusses Ganesha as "Buddhi's Husband".</ref> | |||

| ===Obstacles=== | |||

| === Om === | |||

| Ganesha is the Lord of Obstacles, both of a material and spiritual order.<ref>"Lord of Obstacles," a common name, appears in the title of Courtright's ''{{IAST|Gaṇeśa}}: Lord of Obstacles, Lord of Beginnings''. For equivalent Sanskrit names ''Vighneśvara'' and ''Vighnarāja'', see: Courtright, p. 136.</ref> He can place obstacles in the path of those who need to be checked and can remove blockages just as easily. The Sanskrit terms ''vighnakartā'' ("obstacle-creator") and ''vighnahartā'' ("obstacle-destroyer") summarize the dual roles.<ref>Yuvraj Krishhan notes that some of his names reflect shadings of multiple roles that have shifted over time in this quote: "{{IAST|Gaṇeśa}} has a dual nature; as Vināyaka, as a ''grāmadevatā'', he is ''vighnakartā'', and as {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}} he is ''vighnahartā'', a ''{{IAST|paurāṇic devatā}}''." Krishan, p. viii.</ref> Both functions are vital to his character, as Robert Brown explains: | |||

| ] | |||

| Ganesha is identified with the Hindu ] ]. The term ''{{IAST|oṃkārasvarūpa}}'' (Om is his form), when identified with Ganesha, refers to the notion that he personifies the primal sound.<ref>Grimes, p. 77.</ref> The '']'' attests to this association. Chinmayananda translates the relevant passage as follows:{{Sfn|Chinmayananda|1987|p= 127, In Chinmayananda's numbering system, this is ''upamantra'' 8.}} | |||

| {{quote|(O Lord Ganapati!) You are (the Trimurti) ], ], and ]. You are ]. You are fire <nowiki>]<nowiki>]</nowiki> and air <nowiki>]<nowiki>]</nowiki>. You are the sun <nowiki>]<nowiki>]</nowiki> and the moon <nowiki>]ma<nowiki>].</nowiki> You are ]. You are (the three worlds) Bhuloka , Antariksha-loka , and ]loka . You are Om. (That is to say, You are all this).}} | |||

| <blockquote class="toccolours" style="float:none; padding: 10px 15px 10px 15px; display:table;">Even after the {{IAST|Purāṇic Gaṇeśa}} is well-defined, in art {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}} remained predominantly important for his dual role as creator and remover of obstacles, thus having both a negative and a positive aspect.<ref>Brown, p. 6.</ref></blockquote> | |||

| Some devotees see similarities between the shape of Ganesha's body in iconography and the shape of Om in the ] and ] scripts.<ref>For examples of both, see: {{Harvard citation no brackets|Grimes|1995|pp=79–80}}</ref> | |||

| Paul Courtright says that: | |||

| === First chakra === | |||

| <blockquote class="toccolours" style="float:none; padding: 10px 15px 10px 15px; display:table;">{{IAST|Gaṇeśa}} is also called Vighneśvara or Vighnarāja, the Lord of Obstacles. His task in the divine scheme of things, his ''dharma'', is to place and remove obstacles. It is his particular territory, the reason for his creation.<ref>Courtright, p. 136.</ref></blockquote> | |||

| According to ], Ganesha resides in the first ], called ] ({{IAST|mūlādhāra}}). ''Mula'' means "original, main"; ''adhara'' means "base, foundation". The muladhara chakra is the principle on which the manifestation or outward expansion of primordial Divine Force rests.<ref name="T83">Tantra Unveiled: Seducing the Forces of Matter & Spirit By Rajmani Tigunait; Contributor Deborah Willoughby; Published 1999; Himalayan Institute Press; p. 83; {{ISBN|0893891584}}</ref> This association is also attested to in the '']''. Courtright translates this passage as follows: "You continually dwell in the ] at the base of the spine ."<ref name="courtright">{{Harvard citation no brackets|Courtright|1985|p=253}}.</ref> Thus, Ganesha has a permanent abode in every being at the Muladhara.{{Sfn|Chinmayananda|1987|p= 127, In Chinmayananda's numbering system this is part of ''upamantra'' 7. 'You have a permanent abode (in every being) at the place called "Muladhara"'.}} Ganesha holds, supports and guides all other chakras, thereby "governing the forces that propel the ]".<ref name="T83" /> | |||

| == Family and consorts == | |||

| {{see also|Mythological anecdotes of Ganesha|Consorts of Ganesha}} | |||

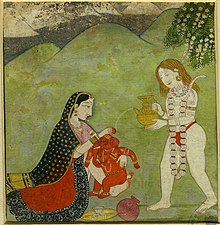

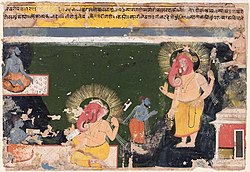

| ] and ] giving a bath to Ganesha. Kangra miniature, 18th century. ], New Delhi.<ref>This work is reproduced and described in Martin-Dubost (1997), p. 51, which describes it as follows: "This square shaped miniature shows us in a Himalayan landscape the god {{IAST|Śiva}} sweetly pouring water from his {{IAST|kamaṇḍalu}} on the head of baby {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}}. Seated comfortably on the meadow, {{IAST|Pārvatī}} balances with her left hand the baby {{IAST|Gaņeśa}} with four arms with a red body and naked, adorned only with jewels, tiny anklets and a golden chain around his stomach, a necklace of pearls, bracelets and armlets."</ref>]] | |||

| Though Ganesha is popularly held to be the son of ] and ], the ] texts give different versions about his birth.<ref>In: | |||

| Ganesha is considered to be the Lord of Intelligence.<ref>Nagar, p. 5.</ref> In Sanskrit, the word ''buddhi'' is a feminine noun that is variously translated as intelligence, wisdom, or intellect.<ref>Apte, p. 703.</ref> The concept of buddhi is closely associated with the personality of Ganesha, especially in the Puranic period, where many stories showcase his cleverness and love of intelligence. One of Ganesha's names in the '']'' and the '']'' is ''Buddhipriya''.<ref>''Ganesha Purana'' I.46, v. 5 of the Ganesha Sahasranama section in GP-1993, Sharma edition. It appears in verse 10 of the version as given in the Bhaskararaya commentary.</ref> This name also appears in a special list of twenty-one names that {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}} says are of special importance at the end of the ''Ganesha Sahasranama''.<ref>Sharma edition, GP-1993 I.46, verses 204-206. The Bailey edition uses a variant text, and where Sharma reads Buddhipriya, Bailey translates "Granter-of-lakhs."</ref> The word ''priya'' can mean "fond of," but in a marital context it can mean "lover" or "husband." Buddhipriya probably refers to Ganesha's well-known association with intelligence. | |||

| *{{Harvard citation no brackets|Nagar|1992|pp=7–14}}. For a summary of Puranic variants of birth stories. | |||

| *{{Harvard citation no brackets|Martin-Dubost|1965|pp=41–82}}. Chapter 2, "Stories of Birth According to the {{IAST|Purāṇas}}".</ref> In some he was created by Parvati,<ref>''Shiva Purana'' IV. 17.47–57. ''Matsya Purana'' 154.547.</ref> or by Shiva<ref>Linga Purana</ref> or created by Shiva ''and'' Parvati,<ref>''{{IAST|Varāha}} Purana'' 23.18–59.</ref> in another he appeared mysteriously and was discovered by Shiva and Parvati<ref>For summary of ''Brahmavaivarta Purana, Ganesha Khanda'', 10.8–37, see: {{Harvard citation no brackets|Nagar|1992|pp=11–13}}.</ref> or he was born from the elephant headed goddess Malini after she drank Parvati's bath water that had been thrown in the river.<ref name="Melton2011">{{cite book|last=Melton|first=J. Gordon|title=Religious Celebrations: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KDU30Ae4S4cC&pg=PA325|date=13 September 2011|publisher=ABC-CLIO|isbn=978-1598842050|pages=325–}}</ref> | |||

| The family includes his brother, the god of war, ], who is also called Skanda and Murugan.<ref>For a summary of variant names for Skanda, see: {{Harvard citation no brackets|Thapan|1997|p=300}}.</ref> Regional differences dictate the order of their births. In northern India, Skanda is generally said to be the elder, while in the south, Ganesha is considered the firstborn.<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Khokar|Saraswati|2005}} p.4.</ref> In ], Skanda was an important martial deity from about 500 BCE to about 600 CE, after which worship of him declined significantly. As Skanda fell, Ganesha rose. Several stories tell of sibling rivalry between the brothers<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Brown|1991|p=79}}.</ref> and may reflect sectarian tensions.<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Oka|1913|p=38}}.</ref> | |||

| This association with wisdom also is reflected in the name ''Buddha'', which appears as a name of Ganesha in the second verse of the ''Ganesha Purana'' version of the ''Ganesha Sahasranama''.<ref>''{{IAST|Gaṇeśasahasranāmastotram: mūla evaṁ srībhāskararāyakṛta ‘khadyota’ vārtika sahita}}''. ({{IAST|Prācya Prakāśana: Vārāṇasī}}, 1991). Includes the full source text and the commentary by Bhāskararāya in Sanskrit. The name "Buddha" is in verse 7 of the volume cited, which corresponds to verse 2 of the śasahasranāma proper.</ref> The positioning of this name at the beginning of the ''Ganesha Sahasranama'' reveals the name's importance. ]'s commentary on the ''Ganesha Sahasranama'' says that this name means that ] was an avatar of Ganesha.<ref>Bhaskararaya's commentary on the name Buddha with commentary verse number is: "नित्यबुद्धस्वरूपत्वात् अविद्यावृत्तिनाशनः । यद्वा जिनावतारत्वाद् बुद्ध इत्यभिधीयते ॥ १५ ॥"</ref> This interpretation is not widely known even among ]. Buddha is not mentioned in the lists of Ganesha's incarnations given in the main sections of the ''Ganesha Purana'' and '']''. Bhaskararaya also provides a more general interpretation of this name as simply meaning that Ganesha's very form is "eternal elightenment" ({{IAST|nityabuddaḥ}}), so he is named Buddha. | |||

| ] (1848–1906)]] | |||

| Ganesha's marital status, the subject of considerable scholarly review, varies widely in mythological stories.<ref name="lawrence_cohen">For a review, see: Cohen, Lawrence. "The Wives of {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}}". {{Harvard citation no brackets|Brown|1991|pp=115–140}}</ref> One pattern of myths identifies Ganesha as an unmarried '']''.<ref>In: | |||

| *{{Harvnb|Getty|1936|p=33}}. "According to ancient tradition, {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}} was a {{IAST|Brahmacārin}}, that is, an unmarried deity; but legend gave him two consorts, personifications of Wisdom (Buddhi) and Success (Siddhi)." | |||

| *{{Harvnb|Krishan|1999|p=63}}. "... in the ''{{IAST|smārta}}'' or orthodox traditional religious beliefs, {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}} is a bachelor or ''{{IAST|brahmacārī}}''"</ref> This view is common in southern India and parts of northern India.<ref>For discussion on celibacy of Ganesha, see: Cohen, Lawrence, "The Wives of {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}}", in: {{Harvnb|Brown|1991|pp=126–129}}.</ref> Another popularly-accepted mainstream pattern associates him with the concepts of ''Buddhi'' (intellect), ''Siddhi'' (spiritual power), and ''Riddhi'' (prosperity); these qualities are personified as goddesses, said to be Ganesha's wives.<ref>For a review of associations with Buddhi, Siddhi, Riddhi, and other figures, and the statement "In short the spouses of {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}} are the personifications of his powers, manifesting his functional features...", see: {{Harvnb|Krishan|1999|p=62}}.</ref> He also may be shown with a single consort or a nameless servant (Sanskrit: ''{{IAST|daşi}}'').<ref>For single consort or a nameless ''{{IAST|daşi}}'' (servant), see: Cohen, Lawrence, "The Wives of {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}}", in: {{Harvnb|Brown|1991|p=115}}.</ref> Another pattern connects Ganesha with the goddess of culture and the arts, ] or {{IAST|Śarda}} (particularly in ]).<ref>For associations with Śarda and ] and the identification of those goddesses with one another, see: Cohen, Lawrence, "The Wives of {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}}", in: {{Harvnb|Brown|1991|pp=131–132}}.</ref> He is also associated with the goddess of luck and prosperity, ].<ref>For associations with Lakshmi see: Cohen, Lawrence, "The Wives of {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}}", in: {{Harvnb|Brown|1991|pp=132–135}}.</ref> Another pattern, mainly prevalent in the ] region, links Ganesha with the banana tree, ].<ref>For discussion of the Kala Bou, see: Cohen, Lawrence, "The Wives of {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}}", in: {{Harvnb|Brown|1991|pp=124–125}}.</ref> | |||

| The '']'' says that Ganesha had begotten two sons: {{IAST|Kşema}} (safety) and {{IAST|Lābha}} (profit). In northern Indian variants of this story, the sons are often said to be {{IAST|Śubha}} (auspiciousness) and {{IAST|Lābha}}.<ref>For statement regarding sons, see: Cohen, Lawrence, "The Wives of {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}}", in: {{Harvnb|Brown|1991|p=130}}.</ref> The 1975 ] '']'' shows Ganesha married to Riddhi and Siddhi and having a daughter named ], the goddess of satisfaction. This story has no Puranic basis, but Anita Raina Thapan and Lawrence Cohen cite Santoshi Ma's cult as evidence of Ganesha's continuing evolution as a popular deity.<ref>In: | |||

| ===Aum=== | |||

| * Cohen, Lawrence. "The Wives of {{IAST|Gaṇeśa}}". {{Harvard citation no brackets|Brown|1991|p=130}}. | |||

| * {{Harvard citation no brackets|Thapan|1997}}, p. 15–16, 230, 239, 242, 251.</ref> | |||

| == Worship and festivals == | |||

| ]) Aum jewel]] | |||

| ] celebrations in ]]] | |||

| Ganesha is worshipped on many religious and secular occasions; especially at the beginning of ventures such as buying a vehicle or starting a business.<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Krishan|1981–1982|pp=1–3}}</ref> K.N Soumyaji says, "there can hardly be a home which does not house an idol of Ganapati. ... Ganapati, being the most popular deity in India, is worshipped by almost all castes and in all parts of the country".<ref>K.N. Somayaji, ''Concept of Ganesha'', p. 1 as quoted in {{Harvard citation no brackets|Krishan|1999|pp=2–3}}</ref> Devotees believe that if Ganesha is propitiated, he grants success, prosperity and protection against adversity.<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Krishan|1999|p=38}}</ref> | |||

| Ganesha is identified with the Hindu ] ] ({{lang|sa|ॐ}}, also called ''Om''). The term ''{{IAST|oṃkārasvarūpa}}'' ("Aum is his form") when identified with Ganesha refers to the notion that he is the personification of the primal sound.<ref>Grimes, p. 77.</ref> This association is attested to in the '']''. The relevant passage is translated by Paul Courtright as follows: | |||

| Ganesha is a non-sectarian deity. Hindus of all denominations invoke him at the beginning of prayers, important undertakings, and religious ceremonies.<ref>For worship of Ganesha by "followers of all sects and denominations, Saivites, Vaisnavites, Buddhists, and Jainas" see {{Harvnb|Krishan|1981–1982|p=285}}</ref> Dancers and musicians, particularly in southern India, begin art performances such as the ] dance with a prayer to Ganesha.<ref name="Nagar, Preface" /> ]s such as ''Om Shri {{IAST|Gaṇeshāya}} Namah'' (Om, salutation to the Illustrious Ganesha) are often used. One of the most famous mantras associated with Ganesha is ''Om {{IAST|Gaṃ}} Ganapataye Namah'' (Om, {{IAST|Gaṃ}}, Salutation to the Lord of Hosts).<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Grimes|1995|p=27}}</ref> | |||

| <blockquote class="toccolours" style="float:none; padding: 10px 15px 10px 15px; display:table;">You are ], ], and ] <nowiki>]<nowiki>]</nowiki>. You are ], ], and ]. You are ]. You are earth, space, and heaven. You are the manifestation of the mantra "{{IAST|Oṃ}}."<ref>Translation. Courtright, p. 253.</ref></blockquote> | |||

| Devotees offer Ganesha sweets such as ]a and small sweet balls called ]s. He is often shown carrying a bowl of sweets, called a ''{{IAST|modakapātra}}''.<ref>The term ''modaka'' applies to all regional varieties of cakes or sweets offered to Ganesha. {{Harvard citation no brackets|Martin-Dubost|1965|p=204}}.</ref> Because of his identification with the color red, he is often worshipped with ] paste ({{IAST|raktachandana}})<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Martin-Dubost|1965|p=369}}.</ref> or red flowers. {{IAST|Dūrvā}} grass ('']'') and other materials are also used in his worship.<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Martin-Dubost|1965|pp=95–99}}</ref> | |||

| A variant version of this passage is translated by Chinmayananda as follows: | |||

| Festivals associated with Ganesh are ] or Vināyaka chaturthī in the '']'' (the fourth day of the waxing moon) in the month of '']'' (August/September) and the ] (Ganesha's birthday) celebrated on the ''cathurthī'' of the ''{{IAST|śuklapakṣa}}'' (fourth day of the waxing moon) in the month of '']'' (January/February)."<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Thapan|1997}} p. 215</ref> | |||

| <blockquote class="toccolours" style="float:none; padding: 10px 15px 10px 15px; display:table;">(O Lord Ganapati!) You are (the Trinity) Brahma, Vishnu, and ]. You are ]. You are fire and air. You are the sun and the moon. You are ]. You are (the three worlds) Bhuloka, Antariksha-loka, and ]loka. You are Om. (that is to say, You are all this).<ref>Chinmayananda, p. 127. In Chinmayananda's numbering system, this is ''upamantra'' 8.</ref></blockquote> | |||

| ===Ganesha Chaturthi=== | |||

| Some devotees see similarities between the shape of his body in iconography and the shape of Om in the ] and ] scripts.<ref>For examples of both, see: Grimes, pp. 79-80.</ref> | |||

| ] during the festival of Ganesha Chaturthi]] | |||

| An annual festival honours Ganesha for ten days, starting on Ganesha Chaturthi, which typically falls in late August or early September.<ref>For the fourth waxing day in {{IAST|Māgha}} being dedicated to Ganesa ({{IAST|Gaṇeśa-caturthī}}) see: {{Harvard citation|Bhattacharyya|1956}}., "Festivals and Sacred Days", in: Bhattacharyya, volume IV, p. 483.</ref> The festival begins with people bringing in clay idols of Ganesha, symbolising the god's visit. The festival culminates on the day of ], when the idols ('']s'') are immersed in the most convenient body of water.<ref>''The Experience of Hinduism: Essays on Religion in Maharashtra''; Edited By Eleanor Zelliot, Maxine Berntsen, pp. 76–94 ("The Ganesh Festival in Maharashtra: Some Observations" by Paul B. Courtright); 1988; SUNY Press; {{ISBN|088706664X}}</ref> <!-- while the people shout "Ganapati Bappa Morya" (Ganesha come back soon next year). --> Some families have a tradition of immersion on the 2nd, 3rd, 5th, or 7th day. In 1893, ] transformed this annual Ganesha festival from private family celebrations into a grand public event.<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Metcalf|Metcalf}}, p. 150.</ref> He did so "to bridge the gap between the ]s and the non-Brahmins and find an appropriate context in which to build a new grassroots unity between them" in his nationalistic strivings against the British in ].<ref>In: | |||

| ===First chakra=== | |||

| *{{Harvard citation|Brown|1991|p=9}}. | |||