| Revision as of 23:09, 26 December 2007 editAlice (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users2,878 edits →Luanda's Colonial Army: piped levee to Conscription; just revert me if this is the erroneous sense← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 03:29, 25 November 2024 edit undoCommunism is cringe (talk | contribs)54 edits I added “Unknown” to the losses of the NgoyoTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit | ||

| (71 intermediate revisions by 33 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|1670 battle}} | |||

| {{Infobox Military Conflict | |||

| {{EngvarB|date=August 2018}} | |||

| ⚫ | |conflict=Battle of Kitombo | ||

| {{infobox military conflict | |||

| ⚫ | |partof= |

||

| ⚫ | | conflict = Battle of Kitombo | ||

| ⚫ | |date= |

||

| ⚫ | | partof = ] | ||

| ⚫ | |place=Kitombo, ] | ||

| | image = | |||

| |result=Decisive Soyo victory | |||

| | caption = | |||

| ⚫ | |combatant1= |

||

| ⚫ | | date = 18 October 1670 | ||

| |combatant2=Portuguese ] | |||

| ⚫ | | place = Kitombo, ] | ||

| ⚫ | |commander1= |

||

| | coordinates = | |||

| ⚫ | |commander2=Commander ] | ||

| | map_type = | |||

| ⚫ | |strength1=Unknown number of musketeers, |

||

| | map_relief = | |||

| ⚫ | |strength2=Unknown number of irregular bowmen |

||

| | latitude = | |||

| |casualties1=Unknown but included Prince ] | |||

| | longitude = | |||

| ⚫ | |casualties2=Unknown |

||

| | map_size = | |||

| | map_marksize = | |||

| | map_caption = | |||

| | map_label = | |||

| | territory = | |||

| | result = Soyo Victory | |||

| | status = | |||

| ⚫ | | combatant1 = Kongo states of ] and ] | ||

| | combatant2 = ] ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ⚫ | | commander1 = Count ] | ||

| ⚫ | | commander2 = Commander ]{{KIA}} | ||

| | units1 = | |||

| | units2 = | |||

| ⚫ | | strength1 = Unknown number of musketeers,<br>heavy infantry and bowmen<br>4 Dutch light field pieces | ||

| ⚫ | | strength2 = Unknown number of irregular bowmen<br>Unknown number of auxiliary ]<br> 400–500 Portuguese musketeers<br>4 light cannons and a detachment of cavalry | ||

| | casualties1 = Unknown | |||

| ⚫ | | casualties2 = Unknown but very heavy, including ] | ||

| | notes = | |||

| | campaignbox = {{Campaignbox Kongo Civil War}}<br>{{Portuguese colonial campaigns}} | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| The '''Battle of Kitombo''' was a military engagement between forces of the ] state of Soyo, formerly a province of the ], and the ] on 18 October 1670. Earlier in the year a Portuguese expeditionary force had invaded Soyo with the intention of ending its independent existence. The Soyo were supported by the Kingdom of ], which provided men and equipment, and by the Dutch, who provide guns, light cannon and ammunition. The combined Soyo-Ngoyo force was led by Estêvão Da Silva, and the Portuguese by João Soares de Almeida. Both commanders were killed in the battle, which resulted in a decisive victory for Soyo. Few, if any, of the invaders escaped death or capture. | |||

| {{Campaignbox Kongo Civil War}} | |||

| The '''Battle of Kitombo''' was a military engagement between forces of the ] state of Soyo, formerly a province of the ], and the ] colony of Angola. | |||

| ==Background== | |||

| ⚫ | == |

||

| ⚫ | |||

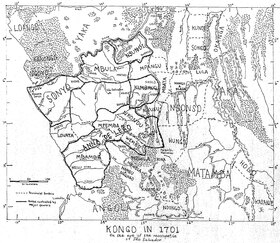

| ] | |||

| ==Preparation== | |||

| ⚫ | The governor of Luanda, ], ordered a force of Portuguese augmented by native allies such as the feared ] into Soyo to crush the kingdom once and for all.<ref |

||

| ⚫ | The Portuguese had long traded with the ], mostly viewing it as a source of slaves. In 1665 a Portuguese army invaded the Kingdom and defeated its army at the ].<ref>Thornton, John K: ''Warfare in Atlantic Africa 1500–1800'' London: Routledge. {{isbn|9781857283938}} Page 103. 1999</ref> The engagement resulted in a crushing Portuguese victory ending in the death of the ] ] and most of the kingdom's nobility, the disbandment of its army and the installation of a Portuguese puppet ruler.<ref>{{cite book|last=Paige|first=Jeffrey M. |title=Agrarian Revolution|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=iuROQYHKmL8C |year=1978|location=New York|publisher=Simon and Schuster|pages=216–17|isbn=978-0-02-923550-8}}</ref> Afterwards, Kongo erupted in a brutal civil war between the ], which had ruled under the dead king, and the ].<ref name=Thorn>Thornton, John K: ''The Kongolese Saint Anthony: Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita and the Antonian Movement, 1684–1706'', page 69. {{isbn|9780521593700}} Cambridge: Cambridge University, 1998</ref> Soyo, home to many Kimpanzu partisans, was eager to take advantage of the chaos.<ref>Thornton, John K: ''The Kongolese Saint Anthonty: Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita and the Antonian Movement, 1684–1706'', page 78. Cambridge: Cambridge University {{isbn|9780521593700}} 1998</ref> Within a few months of the national tragedy at Mbwila, the Prince of Soyo Paulo da Silva invaded the capital of ] and installed his protégé, ] on the throne. This happened again in 1669 with the placement of ] on the throne.<ref name="Gray, Richard page 38">Gray, Richard: ''Black Christians & White Missionaries'' page 38. New Haven: Yale University, 1990 {{isbn|9780300049107}}</ref> By this time both the Portuguese and central authority in Kongo were growing tired of Soyo's meddling. While the Kinlaza and others in Kongo lived in fear of a Soyo invasion, the governor of Luanda wished to curb the growing power of Soyo.<ref name="Gray, Richard page 38" /> With access to ] merchants willing to sell them guns and cannons plus diplomatic access to the Pope, Soyo was on its way to becoming as powerful as Kongo had been before Mbwila. ] of Kongo, driven by Soyo from his capital, fled to Luanda, where he sought Portuguese aid to restore him to the throne.<ref name="Birmingham, David page 61">Birmingham, David: ''Portugal and Africa'', page 61. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 1999 {{isbn|9780333734049}}</ref> In return, he promised Portugal money, mineral concessions and the right to build a fortress in Soyo to keep out the Dutch.<ref name="Birmingham, David page 61" /> | ||

| ===Luanda's Colonial Army=== | |||

| This colonial force was the most powerful that had been organized in Central Africa up until then.<ref>Birmingham, David: "Portugal and Africa", page 61. Palgrave Macmillan, 1999</ref> It included 400 musketeers, a rare detachment of cavalry, 4 light cannons, an unknown number of ] bowmen, Imbangala Auxiliaries and even some naval vessels.<ref>Birmingham, David: "Portugal and Africa", page 61. Palgrave Macmillan, 1999</ref> | |||

| ==Preparations== | |||

| ===Soyo and Ngoyo's Army=== | |||

| ⚫ | The governor of Luanda, ], ordered a force of Portuguese, augmented by native allies such as the feared ], into Soyo to crush the kingdom once and for all.<ref name="Gray, Richard page 38" /> It was led by João Soares de Almeida, with the most powerful colonial force that had been organised in Central Africa up until then.<ref name="Birmingham, David page 61" /> It included 400 musketeers, a rare detachment of cavalry, 4 light cannons, an unknown number of ] bowmen, Imbangala auxiliaries and even some naval vessels.<ref name="Birmingham, David page 61" /><ref>Battell, Andrew and Purchas, Samuel ''The Strange Adventures of Andrew Battell of Leigh, in Angola and the Adjoining Regions'', page 132. London: The Hakluyt Society, 1901 OCLC 959072849</ref> | ||

| ⚫ | The then Prince of Soyo, |

||

| ⚫ | The then Prince of Soyo, Paulo da Silva, received word of the impending invasion and prepared his army to meet it.<ref>Thornton, John K: ''The Kongolese Saint Anthony: Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita and the Antonian Movement, 1684-170'' Cambridge: Cambridge University, page 69. 1998 {{isbn|9780521593700}}</ref> In a surprising show of post-Mbwila BaKongo unity, Soyo called on the kingdom of ] for assistance.<ref name="Thornton, John K page 112">Thornton, John K: ''Warfare in Atlantic Africa 1500–1800'' page 112. London: Routledge, 1999 {{isbn|9781857283938}}</ref> Ngoyo had at one time been at least nominally subordinate to the king of Kongo but had grown apart from the state during the 17th century. Ngoyo, which boasted a large fleet of shallow draught craft, sent many soldiers to its southern neighbour in anticipation of the attack.<ref name="Thornton, John K page 112"/> | ||

| ==The battle== | |||

| ⚫ | Few details |

||

| ⚫ | Few details exist on exactly how the campaign was fought. It was divided into two phases with the first being the ], a brief but bloody engagement north of the Mbidizi river in June. Afterwards the Portuguese advanced deeper into Kongo.<ref name="Birmingham, David page 61" /> | ||

| ===Nfinda Ngula=== | |||

| ⚫ | The |

||

| ⚫ | ==Battle== | ||

| ⚫ | ==Aftermath and peace== | ||

| ⚫ | The |

||

| ⚫ | The decisive engagement of the campaign occurred near or at a wooded area called Nfinda Ngula near the large village of Kitombo in October. During the interval, both forces were able to reorganise and to replenish their supplies. The Soyo army used this time to re-equip themselves with more arms from their Dutch allies.<ref name="Birmingham, David page 61" /> The BaKongo forces regrouped at Nfinda Ngula, a densely forested area that had served Soyo well in their battles against Kongo during the invasions of ]. The Soyo-Ngoyo army rallied around Estêvão Da Silva and his light artillery pieces.<ref>John K. Thornton, ''A History of West Central Africa to 1850'', Cambridge University Press, 2020, p.197</ref><ref name="Gray, Richard page 38" /> It proved difficult to access for the Portuguese artillery, allowing the allied force to use the Dutch light field pieces to good effect. They then charged and routed the Portuguese. The colonial army was comprehensively destroyed.<ref name="Birmingham, David page 61" /> The Portuguese not killed in the battle drowned attempting to flee across the river or were captured.<ref name="Birmingham, David page 61" /> Legend has it the captives were offered as white slaves to the Dutch.<ref name="Birmingham, David page 61" /> Its commander, de Almeida, died during the battle.<ref name="Gray, Richard page 38" /> The number of casualties among the Soyo forces are unknown.<ref>Thornton, John K: ''The Kongolese Saint Anthonty: Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita and the Antonian Movement, 1684–1706'', page 197. Cambridge: Cambridge University, 1998 {{isbn|9780521593700}}</ref> | ||

| ⚫ | ==References== | ||

| ⚫ | {{Reflist |

||

| ⚫ | ==Aftermath and peace== | ||

| ⚫ | The Battle of Kitombo was a humiliating defeat for the Portuguese and a boon for the state of Soyo. Portuguese Angola remained hostile to Soyo and Kongo, but they dared not venture back.<ref name=Thorn/> Soyo and the House of Kimpanzu became even more powerful in the politics of the region, but never attained the wealth of pre-Mbwila Kongo as the Portuguese had feared. The next prince of Soyo used the state's Dutch contacts, specifically through ] missionaries, to persuade the ] to intervene on their behalf. At the behest of the Soyo, the pope sent a papal nuncio to the King of Portugal who obtained an agreement recognising Soyo's independence and bringing an end to further attempts on its sovereignty.<ref name="Gray, Richard page 38" /> | ||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| Line 48: | Line 63: | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| ⚫ | ==References== | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ⚫ | {{Reflist}} | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| {{coord missing|Angola}} | |||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

Latest revision as of 03:29, 25 November 2024

1670 battle

| Battle of Kitombo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Kongo Civil War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Kongo states of Soyo and Ngoyo | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Count Estêvão Da Silva | Commander João Soares de Almeida † | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Unknown number of musketeers, heavy infantry and bowmen 4 Dutch light field pieces |

Unknown number of irregular bowmen Unknown number of auxiliary Imbangala 400–500 Portuguese musketeers 4 light cannons and a detachment of cavalry | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown but very heavy, including João Soares de Almeida | ||||||

| Kongo Civil War | |

|---|---|

The Battle of Kitombo was a military engagement between forces of the BaKongo state of Soyo, formerly a province of the Kingdom of Kongo, and the Portuguese colony of Angola on 18 October 1670. Earlier in the year a Portuguese expeditionary force had invaded Soyo with the intention of ending its independent existence. The Soyo were supported by the Kingdom of Ngoyo, which provided men and equipment, and by the Dutch, who provide guns, light cannon and ammunition. The combined Soyo-Ngoyo force was led by Estêvão Da Silva, and the Portuguese by João Soares de Almeida. Both commanders were killed in the battle, which resulted in a decisive victory for Soyo. Few, if any, of the invaders escaped death or capture.

Background

The Portuguese had long traded with the Kingdom of Kongo, mostly viewing it as a source of slaves. In 1665 a Portuguese army invaded the Kingdom and defeated its army at the Battle of Mbwila. The engagement resulted in a crushing Portuguese victory ending in the death of the Mwenekongo António I and most of the kingdom's nobility, the disbandment of its army and the installation of a Portuguese puppet ruler. Afterwards, Kongo erupted in a brutal civil war between the House of Kinlaza, which had ruled under the dead king, and the House of Kimpanzu. Soyo, home to many Kimpanzu partisans, was eager to take advantage of the chaos. Within a few months of the national tragedy at Mbwila, the Prince of Soyo Paulo da Silva invaded the capital of São Salvador and installed his protégé, Afonso II on the throne. This happened again in 1669 with the placement of Álvaro IX on the throne. By this time both the Portuguese and central authority in Kongo were growing tired of Soyo's meddling. While the Kinlaza and others in Kongo lived in fear of a Soyo invasion, the governor of Luanda wished to curb the growing power of Soyo. With access to Dutch merchants willing to sell them guns and cannons plus diplomatic access to the Pope, Soyo was on its way to becoming as powerful as Kongo had been before Mbwila. King Rafael I of Kongo, driven by Soyo from his capital, fled to Luanda, where he sought Portuguese aid to restore him to the throne. In return, he promised Portugal money, mineral concessions and the right to build a fortress in Soyo to keep out the Dutch.

Preparations

The governor of Luanda, Francisco de Távora, ordered a force of Portuguese, augmented by native allies such as the feared Imbangala, into Soyo to crush the kingdom once and for all. It was led by João Soares de Almeida, with the most powerful colonial force that had been organised in Central Africa up until then. It included 400 musketeers, a rare detachment of cavalry, 4 light cannons, an unknown number of levee bowmen, Imbangala auxiliaries and even some naval vessels.

The then Prince of Soyo, Paulo da Silva, received word of the impending invasion and prepared his army to meet it. In a surprising show of post-Mbwila BaKongo unity, Soyo called on the kingdom of Ngoyo for assistance. Ngoyo had at one time been at least nominally subordinate to the king of Kongo but had grown apart from the state during the 17th century. Ngoyo, which boasted a large fleet of shallow draught craft, sent many soldiers to its southern neighbour in anticipation of the attack.

Few details exist on exactly how the campaign was fought. It was divided into two phases with the first being the Battle of Mbidizi River, a brief but bloody engagement north of the Mbidizi river in June. Afterwards the Portuguese advanced deeper into Kongo.

Battle

The decisive engagement of the campaign occurred near or at a wooded area called Nfinda Ngula near the large village of Kitombo in October. During the interval, both forces were able to reorganise and to replenish their supplies. The Soyo army used this time to re-equip themselves with more arms from their Dutch allies. The BaKongo forces regrouped at Nfinda Ngula, a densely forested area that had served Soyo well in their battles against Kongo during the invasions of Garcia II. The Soyo-Ngoyo army rallied around Estêvão Da Silva and his light artillery pieces. It proved difficult to access for the Portuguese artillery, allowing the allied force to use the Dutch light field pieces to good effect. They then charged and routed the Portuguese. The colonial army was comprehensively destroyed. The Portuguese not killed in the battle drowned attempting to flee across the river or were captured. Legend has it the captives were offered as white slaves to the Dutch. Its commander, de Almeida, died during the battle. The number of casualties among the Soyo forces are unknown.

Aftermath and peace

The Battle of Kitombo was a humiliating defeat for the Portuguese and a boon for the state of Soyo. Portuguese Angola remained hostile to Soyo and Kongo, but they dared not venture back. Soyo and the House of Kimpanzu became even more powerful in the politics of the region, but never attained the wealth of pre-Mbwila Kongo as the Portuguese had feared. The next prince of Soyo used the state's Dutch contacts, specifically through Capuchin missionaries, to persuade the Pope to intervene on their behalf. At the behest of the Soyo, the pope sent a papal nuncio to the King of Portugal who obtained an agreement recognising Soyo's independence and bringing an end to further attempts on its sovereignty.

See also

References

- Thornton, John K: Warfare in Atlantic Africa 1500–1800 London: Routledge. ISBN 9781857283938 Page 103. 1999

- Paige, Jeffrey M. (1978). Agrarian Revolution. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 216–17. ISBN 978-0-02-923550-8.

- ^ Thornton, John K: The Kongolese Saint Anthony: Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita and the Antonian Movement, 1684–1706, page 69. ISBN 9780521593700 Cambridge: Cambridge University, 1998

- Thornton, John K: The Kongolese Saint Anthonty: Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita and the Antonian Movement, 1684–1706, page 78. Cambridge: Cambridge University ISBN 9780521593700 1998

- ^ Gray, Richard: Black Christians & White Missionaries page 38. New Haven: Yale University, 1990 ISBN 9780300049107

- ^ Birmingham, David: Portugal and Africa, page 61. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 1999 ISBN 9780333734049

- Battell, Andrew and Purchas, Samuel The Strange Adventures of Andrew Battell of Leigh, in Angola and the Adjoining Regions, page 132. London: The Hakluyt Society, 1901 OCLC 959072849

- Thornton, John K: The Kongolese Saint Anthony: Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita and the Antonian Movement, 1684-170 Cambridge: Cambridge University, page 69. 1998 ISBN 9780521593700

- ^ Thornton, John K: Warfare in Atlantic Africa 1500–1800 page 112. London: Routledge, 1999 ISBN 9781857283938

- John K. Thornton, A History of West Central Africa to 1850, Cambridge University Press, 2020, p.197

- Thornton, John K: The Kongolese Saint Anthonty: Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita and the Antonian Movement, 1684–1706, page 197. Cambridge: Cambridge University, 1998 ISBN 9780521593700

Categories: