| Revision as of 15:02, 3 January 2008 editDsp13 (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, IP block exemptions, Pending changes reviewers103,591 edits →External links: cats← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 05:05, 27 November 2024 edit undo45.96.110.173 (talk) →International editionsTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit | ||

| (196 intermediate revisions by 80 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Former Belgian Comics magazine}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=March 2020}} | |||

| '''''Le journal de Tintin''''' (in its ] version), '''''Kuifje''''' (] version), was a weekly ] of the second half of the ]. Subtitled ''"The Journal for the Youth from 7 to 77"'', it has been one of the major sources of creation in the ] scene and published some famous series such as '']'', '']'', and the principal title '']''. The first publication was in 1946, and it ceased for good in 1993. A Greek version existed during 1969-1972. | |||

| {{italic title}} | |||

| {{Infobox comic book title <!--Misplaced Pages:WikiProject Comics--> | |||

| |title = Tintin | |||

| |image = Tintin magazine001.jpg | |||

| |imagesize = <!-- default 250 --> | |||

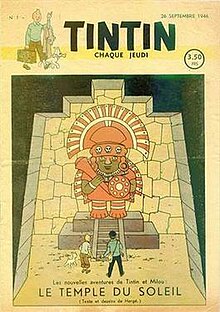

| |caption = ''Tintin'' No. 1 (26 September 1946) | |||

| |schedule = Weekly | |||

| |Anthology = y | |||

| |ongoing = | |||

| |Fantasy = | |||

| |publisher = ] | |||

| |date = | |||

| |startmo = 26 September | |||

| |startyr = 1946 | |||

| |endmo = 29 June | |||

| |endyr = 1993 | |||

| |issues = | |||

| |main_char_team = ] | |||

| |writers = | |||

| |artists = | |||

| |pencillers = | |||

| |inkers = | |||

| |letterers = | |||

| |colorists = | |||

| |editors = | |||

| |creative_team_month = | |||

| |creative_team_year = | |||

| |creators = | |||

| |TPB = | |||

| |ISBN = | |||

| |TPB# = | |||

| |ISBN# = | |||

| |subcat = | |||

| |altcat = | |||

| |sort = Tintin (magazine) | |||

| |addpubcat1 = | |||

| |nonUS = y | |||

| }} | |||

| '''''Tintin''''' ({{langx|fr|Le Journal de Tintin}}; {{langx|nl|Kuifje}}) was a weekly ] of the second half of the 20th century. Subtitled ''"The Magazine for the Youth from 7 to 77"'', it was one of the major publications of the ] scene and published such notable series as '']'', '']'', and the principal title '']''. Originally published by ], the first issue was released in 1946, and it ceased publication in 1993. | |||

| ''Tintin'' magazine was part of an elaborate publishing scheme. The magazine's primary content focused on a new page or two from several forthcoming comic albums that had yet to be published as a whole, thus drawing weekly readers who could not bear to wait for entire albums. There were several ongoing stories at any given time, giving wide exposure to lesser-known artists. ''Tintin'' was also available bound as a hardcover or softcover collection. The content always included filler material, some of which was of considerable interest to fans, for example alternate versions of pages of the Tintin stories, and interviews with authors and artists. Not every comic appearing in ''Tintin'' was later put into book form, which was another incentive to subscribe to the magazine. If the quality of ''Tintin'' printing was high compared to American comic books through the 1970s, the quality of the ] was superb, utilizing expensive paper and printing processes (and having correspondingly high prices). | |||

| == |

==Publication history== | ||

| Raymond Leblanc and his partners had started a small publishing house after ], and decided to create an illustrated youth magazine. They decided that ''Tintin'' would be the perfect hero, as he was already very well known. Business partner André Sinave went to see ], and proposed creating the magazine. Hergé, who had worked for '']'' during the war, was being prosecuted for having collaborated with the Germans. He thus did not have a publisher at the moment.<ref name=Leblanc>{{cite journal |first=Toon |last=Horsten |year=2006 |month=December |title=De 9 levens van Raymond Leblanc |journal=Stripgids |volume=2 |issue=2 |pages=10-19 |accessdate=2007-03-26}}</ref> After consulting his friend ], Hergé agreed. The first issue, published on 26 September 1946, was in ] and entitled ''Tintin''. It featured Hergé, Jacobs, ] and ] as ].<ref name=lambiek-tintinmag>{{Cite web|last=Lambiek Comiclopedia|title=''Tintin'' comic magazine|url=http://lambiek.net/magazines/tintin.htm}}</ref> Simultaneously, a Dutch version entitled ''Kuifje'' was published, Kuifje being the name of the eponymous character Tintin in Dutch. 40,000 copies were made in French, and 20,000 in Dutch.<ref name=Leblanc/> In 1948, when the magazine grew from 12 to 20 pages and a version for France was created, a bunch of new young artists joined the team: the French ] and ], ] and the Flemish ]. | |||

| ===Early history: 1946 to 1949=== | |||

| For the Dutch language version ''Kuifje'', a separate editor-in-chief was appointed, Karel Van Milleghem. He invented the famous slogan "The magazine for the Youth of 7 until 77", and gave Raymond Leblanc the idea for the animation studio ], which became the largest European animation studio and produced 10 long movies, including a few Tintin ones. It was Van Milleghem who introduced ] to the magazine and to Hergé. He became a regular in the magazine and the main artist in the Studio Hergé.<ref name=Leblanc/> During decades, Hergé kept artistic control over the magazine, even though he was sometimes absent for long periods and new work of his became rarer. His influence is highly evident in '']'' for which he imposed onto Vandersteen a stronger attention to the scenarios, the cutting, decors, leading to some of the best ''Suske en Wiske'' albums. | |||

| ] and his partners had started a small publishing house after World War II, and decided to create an illustrated youth magazine. They decided that ''Tintin'' would be the perfect hero, as he was already very well known. Business partner André Sinave went to see ''Tintin'' author ], and proposed creating the magazine. Hergé, who had worked for '']'' during the war, was being prosecuted for having allegedly collaborated with the Germans, and thus was without a publisher.<ref name=Leblanc>{{cite journal |first=Toon |last=Horsten |date=December 2006 |title=De 9 levens van Raymond Leblanc |journal=Stripgids |language=Dutch|volume=2 |issue=2 |pages=10–19}}</ref> After consulting with his friend ], Hergé agreed. | |||

| The first issue, published on 26 September 1946, was in French. It featured Hergé, Jacobs, ] and ] as ],<ref name=lambiek-tintinmag>{{Cite web|last=Lambiek Comiclopedia|title=''Tintin'' comic magazine|url=http://lambiek.net/magazines/tintin.htm}}</ref> with their mutual friend ] serving as editor. (Due to suspicions of incivism left over from the war, Van Melkebeke was forced to step down as editor soon after.)<ref name=Comiclopedia>, Lambiek's ''Comiclopedia''. Accessed 16 December 2013.</ref> A Dutch edition, entitled ''Kuifje'', was published simultaneously (Kuifje being the name of the eponymous character Tintin in Dutch). 40,000 copies were released in French, and 20,000 in Dutch.<ref name=Leblanc/> | |||

| ==The Tintin-voucher== | |||

| In order to keep its readership loyal, the journal created a sort of fidelity passport, called the "Chèque Tintin" in France (Tintin-voucher) and "Timbre Tintin" in Belgium (Tintin-stamp), which was offered with every issue of the magazine, in every comic album by ], and on many food products as well. These stamps could be exchanged for various gifts not available in commercial establishments. Other brands, mostly from food companies, affiliated themselves to the Tintin-voucher system: they would be found on flour, semolina boxes, ... A Tintin soda existed, and even Tintin-shoes. The French Railways Company went as far as to propose 100km of railway transportation for 800 stamps. | |||

| Among the gifts, there were super chromos extracted from the magazine issues, or even original art. | |||

| For ''Kuifje'', a separate editor-in-chief was appointed, Karel Van Milleghem. He invented the famous slogan "The magazine for the youth from 7 to 77", later picked up by the other editions. (Van Milleghem gave Raymond Leblanc the idea for the animation studio ], which became the largest European animation studio, producing ten feature-length movies, including a few featuring Tintin. It was Van Milleghem who also introduced ] to the magazine and to Hergé. De Moor became a regular in the magazine and the main artist in the ].)<ref name=Leblanc/> | |||

| At the time the vouchers were initiated, the magazine sold 80,000 copies in Belgium and only 70,000 in France. Due to the success of the vouchers, the circulation in France quickly rose to 300,000 a week.<ref name=Leblanc/> The vouchers disappeared again at the end of the 1960s. | |||

| In 1948, the magazine grew from 12 to 20 pages and a separate version for France was launched. A group of new young artists joined the team: the French ] and ], ] and the Flemish ]. | |||

| ==The 1950s== | |||

| For decades, Hergé had artistic control over the magazine, even though he was sometimes absent for long periods and new work of his became rarer. His influence is highly evident in Vandersteen's '']'' for which Hergé imposed a stronger attention to the stories, editing, and a change of art style. | |||

| ====The Tintin-voucher==== | |||

| In order to keep its readership loyal, ''Tintin'' magazine created a sort of fidelity passport,{{When|date=January 2011}} called the "Chèque Tintin" in France (Tintin-voucher) and "Timbre Tintin" in Belgium (Tintin-stamp), which was offered with every issue of the magazine, in every comic album by ], and on many food products as well. These stamps could be exchanged for various gifts not available in commercial establishments. Other brands, mostly from food companies, affiliated themselves with the Tintin voucher system: they could be found on flour, semolina boxes, etc. A Tintin soda existed, and even Tintin shoes. The French Railways Company went as far as to propose 100 km of railway transportation for 800 stamps. Among the gifts, there were super chromos extracted from the magazine issues, or original art. | |||

| At the time the vouchers were initiated, the magazine was selling 80,000 copies in Belgium and only 70,000 in France. Due to the success of the vouchers, the circulation in France quickly rose to 300,000 a week.<ref name=Leblanc/> The vouchers disappeared by the end of the 1960s. | |||

| ===The 1950s=== | |||

| In the 1950s new artists and series showed up: | In the 1950s new artists and series showed up: | ||

| *] with its humoristic ] '']'' and his detective series '']'' | |||

| *] |

*] with his humorous ] '']'' and his detective series '']'' | ||

| *], with his fantasy series '']'' and detective series '']'' | |||

| *] - '']''. | |||

| *] with '']'' | *] with '']'' | ||

| *] and ] with '']'' | *] and ] with '']'' | ||

| The magazine became more and more international and successful: at one time, there were separate versions for France, Switzerland, Canada, Belgium and the Netherlands, with about 600,000 copies a week. The magazine had increased to 32 pages, and a cheaper version was created as well: ''Chez Nous'' (in French) / ''Ons Volkske'' (in Dutch), printed on cheaper paper and featuring mainly reprints from ''Tintin'' magazine, plus some new series by Tibet and Studio Vandersteen.<ref name=Leblanc/> |

The magazine became more and more international and successful: at one time, there were separate versions for France, Switzerland, Canada, Belgium and the Netherlands, with about 600,000 copies a week. The magazine had increased to 32 pages, and a cheaper version was created as well: ''Chez Nous'' (in French) / '']'' (in Dutch), printed on cheaper paper and featuring mainly reprints from ''Tintin'' magazine, plus some new series by Tibet and Studio Vandersteen.<ref name=Leblanc/> | ||

| ===The 1960s=== | |||

| ==''Spirou'' and ''Tintin'' rivalry== | |||

| In the 1960s the magazine kept on attracting new artists. The editorial line was clearly bent towards humor, with ] (as editor-in-chief and author of series such as the remake of '']''), ] (with ''Taka Takata''), ] (with '']'') and ] (with '']''). Other authors joined the magazine, like ] (with '']'' and '']'') and ] (with '']'').<ref name=lambiek-tintinmag/> | |||

| ''Tintin'' magazine has always been in competition with '']''. If one artist was published by one of the magazines, he would not be published by the other one. This was a gentleman's agreement between the two publishers, Raymond Leblanc of ] and ] of ]. One notable exception was ], whom in 1955, after a dispute with its editor, moved from the more popular ''Spirou'' to ''Tintin''.<ref name=lambiek-tintinmag/> The dispute was quickly settled, but Franquin had signed an agreement with ''Tintin'' for five years. He created '']'' for ''Tintin'' while pursuing work for ''Spirou''. He quit ''Tintin'' at the end of his contract. Some artists moved from ''Spirou'' to ''Tintin'' like ] and ], while some went from ''Tintin'' to ''Spirou'' like ] and ]. | |||

| ==The |

===The 1970s=== | ||

| In the 1970s the comics scene in France and Belgium went through important changes. The mood for magazines had declined in favor of albums in the late 1960s. In 1965, Greg was appointed chief editor. He transformed the editorial line, in order to keep the pace with the new way of thinking of the time. The characters gained psychological dimensions, real women characters appeared, and sex. New foreign artists series were added to the magazine. Moralizing articles and long biographies disappeared as well. These transformations were crowned with success, leading to the ] at the ], awarded to the magazine in 1972 for the best publication of the year. Greg quit his chief editor position in 1974. | |||

| In the 1960s the magazine kept on attracting new artists. The editorial line was clearly leant towards humor, with ] (as editor-in-chief and author of series such as the remake of '']''), ] (with '']''), ] (with '']'') and ] (with '']''). Other authors joined the magazine like ] (with '']'' and '']'') and ] (with '']'').<ref name=lambiek-tintinmag/> | |||

| ==The 1970s== | |||

| In the 1970s the comics' scene in France and Belgium went through important changes. The mood for magazines had declined in favor of albums in the late 1960s. In 1965, Greg was appointed chief editor. He transformed the editorial line, in order to keep the pace with the new way of thinking of the time. The characters gained psychological dimensions, real women characters appeared, and sex. New foreign artists series were added to the magazine. Moralizing articles and long biographies disappeared also. These transformations were crowned with success, leading to the ] od the festival of ], awarded to the magazine in 1972 for the best publication of the year. Greg quit his chief editor position in 1974. | |||

| The major new authors in the 1970s were: | The major new authors in the 1970s were: | ||

| *] ('']'') | *] ('']'') | ||

| *] ('']'') | *] ('']'') | ||

| * |

*{{ill|Cosey (artist)|lt=Cosey|de|Cosey|es|Cosey|fr|Cosey}} ('']'') | ||

| *] ('']'') | *] ('']'') | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] ('']'') | *] ('']'') | ||

| *] ('']'') | *] ('']'') | ||

| And more in the humor vein: | And more in the humor vein: | ||

| *] & ] with '']'' |

*] & ] with '']'' | ||

| ==The 1980s and 1990s== | ===The 1980s and 1990s=== | ||

| The 1980s showed a steady decline of popularity of ''Tintin'' magazine, with different short |

The 1980s showed a steady decline of popularity of ''Tintin'' magazine, with different short-lived attempts to attract a new audience. Adolescents and adults preferred the magazine '']'', if they read comics at all, and younger children seemed less inclined to read comic magazines and preferred ]. Still, some important new authors and series started, including ], with '']'', and ], with '']''. At the end of 1980, the Belgian edition was cancelled, leaving the French edition remaining. | ||

| In 1988, the circulation of the French version had dropped to 100,000, and when the contract between the Hergé family and Raymond Leblanc finished, the name was changed to ''Tintin Reporter'' |

In 1988, the circulation of the French version had dropped to 100,000, and when the contract between the Hergé family and Raymond Leblanc finished, the name was changed to ''Tintin Reporter''. Alain Baran, a friend of Hergé, tried to revive the magazine in December 1992. The magazine disappeared after six months, leaving behind a financial disaster.<ref name=Leblanc/> The circulation of the magazine dropped dramatically, and publication of the Dutch version ''Kuifje'' ceased in 1992, and the French version, renamed ''Hello Bédé'', finally disappeared in 1993.<ref name=lambiek-tintinmag/> | ||

| ==International editions== | |||

| ==Criticism== | |||

| {{Expand section|date=December 2009}} | |||

| Some people have accused the comic of being slightly racist and in some libraries in the ] it is confined to the 'Adult graphic literature' section <ref name="tintinracist"></ref> | |||

| * A Portuguese version was published between 1968 and 1983. | |||

| * A Greek version existed during 1969–1972. | |||

| * An Egyptian version existed from 1971 to 1980. | |||

| ==''Spirou'' and ''Tintin'' rivalry== | |||

| ==Sources== | |||

| From the beginning, ''Tintin'' magazine was in competition with '']'' magazine. As part of a ] between the two publishers, ] of ] and Charles Dupuis of ], if one artist was published by one of the magazines, he would not be published by the other one. One notable exception, however, was ], who in 1955, after a dispute with his editor, moved from the more popular ''Spirou'' to ''Tintin''.<ref name=lambiek-tintinmag/> The dispute was quickly settled, but by then Franquin had signed an agreement with ''Tintin'' for five years. He created '']'' for ''Tintin'' while pursuing work for ''Spirou''. He quit ''Tintin'' at the end of his contract. Some artists moved from ''Spirou'' to ''Tintin'' like ] and ], while some went from ''Tintin'' to ''Spirou'' like ] and ]. | |||

| ==Main authors and series== | |||

| <!--- The dates given are from BDOubliees.com , combining the earliest and latest dates of either the Belgian or French edition, except for single drawings, ads etc. ---> | |||

| *{{ill|Édouard Aidans|fr}}: ''Tounga'' (1961–1985), ''Bob Binn'' (1960–1977), ''Marc Franval'' (1963–1974) | |||

| *]: '']'' (1978–1993) | |||

| *]: ''Signor Spaghetti'' (1957–1978), '']'', (1959–1968) | |||

| *]: ''Taka Takata'' (1965–1980) | |||

| *]: ''Max L'Explorateur'' (1968–1975), ''Cro-Magnon'' (1974–1993) | |||

| *]: ''Strapontin'' (1958–1968) | |||

| *]: '']'' (1969–1990) | |||

| *]: ''Julie, Claire, Cécile et les autres...'' (1982–1993) | |||

| *{{ill|Cosey (artist)|lt=Cosey|de|Cosey|es|Cosey|fr|Cosey}}: ''Jonathan'' (1975–1986) | |||

| *]: ''Le Chevalier Ardent'' (1966–1986), ''Pom et Teddy'' (1953–1968) | |||

| *]: '']'' (1946–1984, sporadically) | |||

| *]: '']'' (1968–1988) | |||

| *]: '']'' (1970–1990), ''Robin Dubois'' (1969–1986) | |||

| *]: '']'' (1950–1986, sporadically), ''Professeur Tric'' (1950–1979) | |||

| *]: ''Alain Chevalier'' (1976–1985), ''Casseurs'' (1975–1990) | |||

| *]: '']'' (1972–1987), '']'' (1971–1978), '']'' (1978–1982) | |||

| *]: '']'' (1959–1992), '']'' (1965–1970) | |||

| *]: '']'' (1968–1993), '']'' (1971–1983) | |||

| *]: '']'' (1955–1959) | |||

| *] and ]: Various historical comics (1952–1988) | |||

| *]: ''Mr. Magellan'' (1969–1979) | |||

| *]: ''Martin Milan'' (1967–1984) | |||

| *]: '']'' (1958–1962), ''Signor Spaghetti'' (1957–1978) | |||

| *]: '']'' (1957–1976) | |||

| *]: '']'' (1963–1969), '']'' (1966–1985), '']'' (1958–1987) etc. | |||

| *]: ''Benjamin'' (1969–1980) | |||

| *]: '']'' (1946–1966, 1975), '']'' (1946–1954), '']'' (1947–1955) | |||

| *]: '']'' (1966–1980), ''Comanche'' (1969–1982) | |||

| *]: '']'' (1946–1972, 1990) | |||

| *]: '']'' (1954–1966), '']'' (1959–1963) | |||

| *]: '']'' (1957–1969) | |||

| *]: '']'' (1948–1985), ''Lefranc'' (1952–1982, sporadically) | |||

| *]: ''Indésirable Désiré'' (1960–1977), ''3A'' (1962–1967), ''Modeste et Pompon'' (1965–1975) | |||

| *]: ''Rififi'' (1970–1980) | |||

| *]: '']'' (1967–1984) | |||

| *]: ''Jari'' (1957–1978), ''Section R'' (1971–1979) | |||

| *]: '']'' (1977–1992), ''Hans'' (1980–1993) | |||

| *]: ''Julie, Claire, Cécile et les autres...'' (1982–1993) | |||

| *]: ''Ric Hochet'' (1955–1992), ''Chick Bill'' (1955–1993) | |||

| *]: '']'' (1970–1983), ''Robin Dubois'' (1969–1986) | |||

| *]: '']'' (1958–1962) | |||

| *]: '']'' (1977–1992) | |||

| *]: '']'' (1967–1983), '']'' (1975–1993) | |||

| *]: '']'' (1948–1958, 1981), ''Altesse Riri'' (1953–1960) | |||

| *]: ''Taka Takata'' (1965–1980) | |||

| *]: '']'' (1954–1977) | |||

| *]: ''Aria'' (1980–1992) | |||

| ==References== | |||

| {{refbegin}} | {{refbegin}} | ||

| * and BDoubliées {{fr_icon}} | |||

| ===Notes=== | |||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| ===Sources consulted === | |||

| * and BDoubliées {{in lang|fr}} | |||

| {{refend}} | {{refend}} | ||

| ;Footnotes | |||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| * on Lambiek Comiclopecdia | * on Lambiek Comiclopecdia | ||

| * at Tintinologist.org | |||

| {{Tintin and Hergé}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Tintin (magazine)}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 05:05, 27 November 2024

Former Belgian Comics magazine

| Tintin | |

|---|---|

Tintin No. 1 (26 September 1946) Tintin No. 1 (26 September 1946) | |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher | Le Lombard |

| Schedule | Weekly |

| Publication date | 26 September 1946 – 29 June 1993 |

| Main character(s) | Tintin |

Tintin (French: Le Journal de Tintin; Dutch: Kuifje) was a weekly Belgian comics magazine of the second half of the 20th century. Subtitled "The Magazine for the Youth from 7 to 77", it was one of the major publications of the Franco-Belgian comics scene and published such notable series as Blake and Mortimer, Alix, and the principal title The Adventures of Tintin. Originally published by Le Lombard, the first issue was released in 1946, and it ceased publication in 1993.

Tintin magazine was part of an elaborate publishing scheme. The magazine's primary content focused on a new page or two from several forthcoming comic albums that had yet to be published as a whole, thus drawing weekly readers who could not bear to wait for entire albums. There were several ongoing stories at any given time, giving wide exposure to lesser-known artists. Tintin was also available bound as a hardcover or softcover collection. The content always included filler material, some of which was of considerable interest to fans, for example alternate versions of pages of the Tintin stories, and interviews with authors and artists. Not every comic appearing in Tintin was later put into book form, which was another incentive to subscribe to the magazine. If the quality of Tintin printing was high compared to American comic books through the 1970s, the quality of the albums was superb, utilizing expensive paper and printing processes (and having correspondingly high prices).

Publication history

Early history: 1946 to 1949

Raymond Leblanc and his partners had started a small publishing house after World War II, and decided to create an illustrated youth magazine. They decided that Tintin would be the perfect hero, as he was already very well known. Business partner André Sinave went to see Tintin author Hergé, and proposed creating the magazine. Hergé, who had worked for Le Soir during the war, was being prosecuted for having allegedly collaborated with the Germans, and thus was without a publisher. After consulting with his friend Edgar Pierre Jacobs, Hergé agreed.

The first issue, published on 26 September 1946, was in French. It featured Hergé, Jacobs, Paul Cuvelier and Jacques Laudy as artists, with their mutual friend Jacques Van Melkebeke serving as editor. (Due to suspicions of incivism left over from the war, Van Melkebeke was forced to step down as editor soon after.) A Dutch edition, entitled Kuifje, was published simultaneously (Kuifje being the name of the eponymous character Tintin in Dutch). 40,000 copies were released in French, and 20,000 in Dutch.

For Kuifje, a separate editor-in-chief was appointed, Karel Van Milleghem. He invented the famous slogan "The magazine for the youth from 7 to 77", later picked up by the other editions. (Van Milleghem gave Raymond Leblanc the idea for the animation studio Belvision, which became the largest European animation studio, producing ten feature-length movies, including a few featuring Tintin. It was Van Milleghem who also introduced Bob De Moor to the magazine and to Hergé. De Moor became a regular in the magazine and the main artist in the Studio Hergé.)

In 1948, the magazine grew from 12 to 20 pages and a separate version for France was launched. A group of new young artists joined the team: the French Étienne Le Rallic and Jacques Martin, Dino Attanasio and the Flemish Willy Vandersteen.

For decades, Hergé had artistic control over the magazine, even though he was sometimes absent for long periods and new work of his became rarer. His influence is highly evident in Vandersteen's Suske en Wiske for which Hergé imposed a stronger attention to the stories, editing, and a change of art style.

The Tintin-voucher

In order to keep its readership loyal, Tintin magazine created a sort of fidelity passport, called the "Chèque Tintin" in France (Tintin-voucher) and "Timbre Tintin" in Belgium (Tintin-stamp), which was offered with every issue of the magazine, in every comic album by Le Lombard, and on many food products as well. These stamps could be exchanged for various gifts not available in commercial establishments. Other brands, mostly from food companies, affiliated themselves with the Tintin voucher system: they could be found on flour, semolina boxes, etc. A Tintin soda existed, and even Tintin shoes. The French Railways Company went as far as to propose 100 km of railway transportation for 800 stamps. Among the gifts, there were super chromos extracted from the magazine issues, or original art.

At the time the vouchers were initiated, the magazine was selling 80,000 copies in Belgium and only 70,000 in France. Due to the success of the vouchers, the circulation in France quickly rose to 300,000 a week. The vouchers disappeared by the end of the 1960s.

The 1950s

In the 1950s new artists and series showed up:

- Tibet with his humorous western Chick Bill and his detective series Ric Hochet

- Raymond Macherot, with his fantasy series Chlorophylle and detective series Clifton

- Maurice Maréchal - Prudence Petitpas.

- Jean Graton with Michel Vaillant

- Albert Uderzo and René Goscinny with Oumpah-pah

The magazine became more and more international and successful: at one time, there were separate versions for France, Switzerland, Canada, Belgium and the Netherlands, with about 600,000 copies a week. The magazine had increased to 32 pages, and a cheaper version was created as well: Chez Nous (in French) / Ons Volkske (in Dutch), printed on cheaper paper and featuring mainly reprints from Tintin magazine, plus some new series by Tibet and Studio Vandersteen.

The 1960s

In the 1960s the magazine kept on attracting new artists. The editorial line was clearly bent towards humor, with Greg (as editor-in-chief and author of series such as the remake of Zig et Puce), Jo-El Azara (with Taka Takata), Dany (with Olivier Rameau) and Dupa (with Cubitus). Other authors joined the magazine, like William Vance (with Ringo and Bruno Brazil) and Hermann (with Bernard Prince).

The 1970s

In the 1970s the comics scene in France and Belgium went through important changes. The mood for magazines had declined in favor of albums in the late 1960s. In 1965, Greg was appointed chief editor. He transformed the editorial line, in order to keep the pace with the new way of thinking of the time. The characters gained psychological dimensions, real women characters appeared, and sex. New foreign artists series were added to the magazine. Moralizing articles and long biographies disappeared as well. These transformations were crowned with success, leading to the Yellow Kid prize at the Lucca comics festival, awarded to the magazine in 1972 for the best publication of the year. Greg quit his chief editor position in 1974.

The major new authors in the 1970s were:

- Derib (Buddy Longway)

- Franz (Jugurtha)

- Cosey [de; es; fr] (Jonathan)

- Gilles Chaillet (Vasco)

- Jean-Claude Servais

- Hugo Pratt (Corto Maltese)

- Will Eisner (The Spirit)

And more in the humor vein:

- Turk & De Groot with Robin Dubois

The 1980s and 1990s

The 1980s showed a steady decline of popularity of Tintin magazine, with different short-lived attempts to attract a new audience. Adolescents and adults preferred the magazine À Suivre, if they read comics at all, and younger children seemed less inclined to read comic magazines and preferred albums. Still, some important new authors and series started, including Grzegorz Rosiński, with Thorgal, and Andreas, with Rork. At the end of 1980, the Belgian edition was cancelled, leaving the French edition remaining.

In 1988, the circulation of the French version had dropped to 100,000, and when the contract between the Hergé family and Raymond Leblanc finished, the name was changed to Tintin Reporter. Alain Baran, a friend of Hergé, tried to revive the magazine in December 1992. The magazine disappeared after six months, leaving behind a financial disaster. The circulation of the magazine dropped dramatically, and publication of the Dutch version Kuifje ceased in 1992, and the French version, renamed Hello Bédé, finally disappeared in 1993.

International editions

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2009) |

- A Portuguese version was published between 1968 and 1983.

- A Greek version existed during 1969–1972.

- An Egyptian version existed from 1971 to 1980.

Spirou and Tintin rivalry

From the beginning, Tintin magazine was in competition with Spirou magazine. As part of a gentlemen's agreement between the two publishers, Raymond Leblanc of Le Lombard and Charles Dupuis of Dupuis, if one artist was published by one of the magazines, he would not be published by the other one. One notable exception, however, was André Franquin, who in 1955, after a dispute with his editor, moved from the more popular Spirou to Tintin. The dispute was quickly settled, but by then Franquin had signed an agreement with Tintin for five years. He created Modeste et Pompon for Tintin while pursuing work for Spirou. He quit Tintin at the end of his contract. Some artists moved from Spirou to Tintin like Eddy Paape and Liliane & Fred Funcken, while some went from Tintin to Spirou like Raymond Macherot and Berck.

Main authors and series

- Édouard Aidans [fr]: Tounga (1961–1985), Bob Binn (1960–1977), Marc Franval (1963–1974)

- Andreas: Rork (1978–1993)

- Dino Attanasio: Signor Spaghetti (1957–1978), Modeste et Pompon, (1959–1968)

- Jo-El Azara: Taka Takata (1965–1980)

- Bara: Max L'Explorateur (1968–1975), Cro-Magnon (1974–1993)

- Berck: Strapontin (1958–1968)

- Gordon Bess: Redeye (1969–1990)

- Bom: Julie, Claire, Cécile et les autres... (1982–1993)

- Cosey [de; es; fr]: Jonathan (1975–1986)

- François Craenhals: Le Chevalier Ardent (1966–1986), Pom et Teddy (1953–1968)

- Paul Cuvelier: Corentin (1946–1984, sporadically)

- Dany: Olivier Rameau (1968–1988)

- Bob de Groot: Clifton (1970–1990), Robin Dubois (1969–1986)

- Bob de Moor: Barelli (1950–1986, sporadically), Professeur Tric (1950–1979)

- Christian Denayer: Alain Chevalier (1976–1985), Casseurs (1975–1990)

- Derib: Buddy Longway (1972–1987), Go West (1971–1978), Yakari (1978–1982)

- André-Paul Duchâteau: Ric Hochet (1959–1992), Chick Bill (1965–1970)

- Dupa: Cubitus (1968–1993), Chlorophylle (1971–1983)

- André Franquin: Modeste et Pompon (1955–1959)

- Fred and Liliane Funcken: Various historical comics (1952–1988)

- Géri: Mr. Magellan (1969–1979)

- Christian Godard: Martin Milan (1967–1984)

- René Goscinny: Oumpa-Pah (1958–1962), Signor Spaghetti (1957–1978)

- Jean Graton: Michel Vaillant (1957–1976)

- Greg: Zig, Puce et Alfred (1963–1969), Bernard Prince (1966–1985), Chick Bill (1958–1987) etc.

- Hachel: Benjamin (1969–1980)

- Hergé: The Adventures of Tintin (1946–1966, 1975), Jo, Zette et Jocko (1946–1954), Quick et Flupke (1947–1955)

- Hermann: Bernard Prince (1966–1980), Comanche (1969–1982)

- Edgar Pierre Jacobs: Blake et Mortimer (1946–1972, 1990)

- Raymond Macherot: Chlorophylle (1954–1966), Clifton (1959–1963)

- Maurice Maréchal: Prudence Petitpas (1957–1969)

- Jacques Martin: Alix (1948–1985), Lefranc (1952–1982, sporadically)

- Mittéï: Indésirable Désiré (1960–1977), 3A (1962–1967), Modeste et Pompon (1965–1975)

- Mouminoux: Rififi (1970–1980)

- Eddy Paape: Luc Orient (1967–1984)

- Raymond Reding: Jari (1957–1978), Section R (1971–1979)

- Grzegorz Rosinski: Thorgal (1977–1992), Hans (1980–1993)

- Sidney: Julie, Claire, Cécile et les autres... (1982–1993)

- Tibet: Ric Hochet (1955–1992), Chick Bill (1955–1993)

- Turk: Clifton (1970–1983), Robin Dubois (1969–1986)

- Albert Uderzo: Oumpah-pah (1958–1962)

- Jean Van Hamme: Thorgal (1977–1992)

- William Vance: Bruno Brazil (1967–1983), Bob Morane (1975–1993)

- Willy Vandersteen: Bob et Bobette (1948–1958, 1981), Altesse Riri (1953–1960)

- Vicq: Taka Takata (1965–1980)

- Albert Weinberg: Dan Cooper (1954–1977)

- Weyland: Aria (1980–1992)

References

Notes

- ^ Horsten, Toon (December 2006). "De 9 levens van Raymond Leblanc". Stripgids (in Dutch). 2 (2): 10–19.

- ^ Lambiek Comiclopedia. "Tintin comic magazine".

- Van Melkebeke entry, Lambiek's Comiclopedia. Accessed 16 December 2013.

Sources consulted

- Dossier and issue index of Belgian Tintin and French Tintin BDoubliées (in French)

External links

- Tintin comic magazine on Lambiek Comiclopecdia

- Publication dates for the "Tintin" stories. at Tintinologist.org

- Comics publications

- 1946 comics debuts

- 1993 comics endings

- Comics anthologies

- 1946 establishments in Belgium

- 1993 disestablishments in Belgium

- Comics magazines published in Belgium

- Defunct magazines published in Belgium

- French-language magazines

- Bandes dessinées

- Magazines established in 1946

- Magazines disestablished in 1993

- The Adventures of Tintin

- Weekly magazines published in Belgium

- Children's magazines published in Belgium

- Weekly magazines published in France