| Revision as of 09:05, 19 January 2008 editLawrence H K (talk | contribs)190 editsmNo edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 06:55, 21 December 2024 edit undoGreenC bot (talk | contribs)Bots2,561,206 edits Reformat 1 archive link. Wayback Medic 2.5 per WP:USURPURL and JUDI batch #20 | ||

| (288 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|None}} | |||

| ]'s '''Symphony No. 4 in B Flat Major''', ] 60, was written in ]. | |||

| {{Redirect|Beethoven's 4th|the direct-to-video movie|Beethoven's 4th (film)}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=August 2019}} | |||

| ] | |||

| The '''Symphony No. 4''' in ], ] 60, is the fourth-published ] by ]. It was composed in 1806 and premiered in March 1807 at a private concert in Vienna at the town house of ]. The first public performance was at the ] in Vienna in April 1808. | |||

| The symphony is in four movements. It is predominantly genial in tone, and has tended to be overshadowed by the weightier Beethoven symphonies that preceded and followed it – the ] and the ]. Although later composers including ], ] and ] greatly admired the work it has not become as widely known among the music-loving public as the ''Eroica'', the Fifth and other Beethoven symphonies. | |||

| ==Background== | ==Background== | ||

| Beethoven spent the summer of 1806 at the country estate of his patron, ], in ]. In September Beethoven and the Prince visited the house of one of the latter's friends, Count ], in nearby ]. The Count maintained a private orchestra, and the composer was honoured with a performance of his ], written four years earlier.<ref name=kemp>Kemp, Linsday. Notes to LSO Live set LSO0098D</ref> After this, Oppersdorff offered the composer a substantial sum to write a new symphony for him.{{refn|The fee is variously described as "350 florins" and "500 gulden".<ref name=g97>Grove, p. 97</ref><ref>Anderson, p. 1426</ref> Beethoven later received a separate fee of 1500 gulden from the publisher the Wiener Kunst- und Industrie-Comptoir. That sum covered the publishing rights to the symphony together with the ], the three ], the ] and the ].<ref>Albinsson, Staffan. , ''International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music'' 43, no. 2 (2012), pp. 265–302 {{subscription required}}</ref>|group=n}} | |||

| Many People thought that the strange number of Beethoven is dignified, even they thought that symphony is peaceful. Most of them are also thought that there have a difference between ] and ], but ] described Symphony No. 4 as a "slender ] maiden between two Norse gods", referring to the ] and ] Symphonies, both with towering reputations. The symphony plays the opening by the general most classical symphony foreword, and a subject of characteristic melody which comes in the storm. All music movements are subject the most musical parts, resounding, positive, as well as the majestic sound handles each matter. There also contains strong plays as well as the powerful Beethoven's impact, even have the slow movement. There is the neglect in Beethoven's symphonies like the ]. | |||

| Beethoven had been working on what later became his ], and his first intention may have been to complete it in fulfilment of the Count's commission. There are several theories about why, if so, he did not do this. According to ], economic necessity obliged Beethoven to offer the Fifth (together with the '']'') jointly to ] and ].<ref name=g97/> Other commentators suggest that the Fourth was essentially complete before Oppersdorff's commission,<ref name=nypo>, New York Philharmonic. Retrieved 25 August 2019</ref> or that the composer may not yet have felt ready to press on with "the radical and emotionally demanding Fifth",<ref name=kemp/> or that the count's evident liking for the more ] world of the Second Symphony prompted another work in similar vein.<ref name=kemp/> | |||

| The work was dedicated to Count ], a relative of Beethoven's patron, ]. The Count met Beethoven when he traveled to Lichnowsky's summer home where Beethoven was staying. Von Oppersdorff listened to Beethoven's ], and liked it so much that he offered a great amount of money for Beethoven to compose a new symphony for him. The dedication was made to "the Silesian nobleman Count Franz von Oppersdorf".<ref>Paul Netl (1976) ''Beethoven Handbook''. New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., p. 262</ref> | |||

| The work is dedicated to "the Silesian nobleman Count Franz von Oppersdorff".<ref>Netl, p. 262</ref> Although Oppersdorff had paid for exclusive rights to the work for its first six months, his orchestra did not give the first performance.{{refn|Beethoven had to write to Oppersdorff apologising for this breach of their agreement. It is not known whether Oppersdorff's orchestra ever performed the work.<ref>Rodda, Richard , Kennedy Center. Retrieved 25 August 2019</ref>|group=n}} The symphony was premiered in March 1807 at a private concert in Vienna at the town house of Prince Lobkowitz, another of Beethoven's patrons.<ref name="stein">Steinberg, pp. 19–24</ref> The first public performance was at the Burgtheater in Vienna in April 1808.<ref name=cso>Huscher, Philip. , Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Retrieved 25 August 2019</ref> The orchestral parts were published in March 1809, but the full score was not printed until 1821.<ref name=g96>Grove, p. 96</ref> The manuscript, which was for a time owned by ],<ref name=g97/> is now in the ] and can be seen online.<ref>, Staatsbibliothek, Berlin. Retrieved 26 August 2019</ref> | |||

| Beethoven thought that there have gifts from Heaven, when he accepted an invitation to stay as a house guest during the summer and autumn months in ], at the ]'s castle and feels the spalatial splendour, the ], writing desk and quiet room by the Castle. One night, the ] General troops (occupying ]), had been invited to the castle to join Beethoven's piano recital. But Beethoven refused to play as he found there have something impolite on one of the General's aides said, until the Prince himself requested for Beethoven to return in the next day. Another friendlier reception was granted by Count Oppersdorf, which took a liking by Beethoven, not only for the Count clearly admired Beethoven as a composer, but also supporting him to write a new works by offering 350 ] to him. | |||

| ==Instrumentation== | |||

| Beethoven had also decided giving them to the Count as his new work when he almost finished his Symphony No.5. However, he had promised the new symphony is dedicated Prince Lichnowsky solely, and he had played so much of them to the Prince, so he couldn't choose to pass them off anymore. So he put the Symphony No.5 aside and concentrated all his energies on the Symphony No.4, which was given its first performance in ] on ] ]. | |||

| The symphony is scored for ], two ]s, two ]s in ], two ]s, two ] in B{{music|flat}} and E{{music|flat}}, two ]s in B{{music|flat}} and E{{music|flat}}, ] and ].<ref name=g96/> It typically takes between 30 and 35 minutes to perform.{{refn|As well as the tempi adopted by the performers, the playing time is affected by the decision to play or omit the ] in the first movement. This typically makes a difference of about 2½ minutes. Examples from the versions mentioned in the Recordings section are Klemperer and Monteux, who play the repeat and whose first movements last for 12:28 and 12:37 respectively, compared with Toscanini and Karajan, who omit the repeat and respectively take 9:57 and 9:55. The total playing time of the symphony in these four recordings is 35:49, 34:10, 29:59, and 31:09 respectively.<ref>Notes to CD sets Parlophone 0724356679559 (2003), Decca 00028948088942 (2015), Parlophone 5099972333457 (2013), and DG 00028947771579 (2007)</ref>|group=n}} | |||

| ==Analysis== | |||

| There have a good reputation which described by ] (French Author) -- "His fragrance in the brightest day has preserved in his life". | |||

| In general the symphony is sunny and cheerful, with light instrumentation that for some listeners recalls the symphonies of ], with whom Beethoven had studied a decade before.<ref>Grove, pp. 97–99</ref> In a commentary on the symphony Grove comments that Haydn – who was still alive when the new symphony was first performed – might have found the work too strong for his taste.<ref name=g97/> The Fourth Symphony contrasts with Beethoven's style in the previous ], and has sometimes been overshadowed by its massive predecessor{{refn|In the ''Eroica'' the four movements consist of 691, 247, 442 and 473 bars; the Fourth consists of 498, 104, 397 and 355 – making the Fourth 499 bars shorter than its predecessor.<ref>Lockwood, p. 80</ref>|group=n}} and its fiery successor, the Fifth Symphony.<ref name=g97>Grove, p. 97</ref> | |||

| === I. Adagio – Allegro vivace === | |||

| ==Instrumentation== | |||

| {{listen|type=music | |||

| The symphony is scored for ], 2 ]s, 2 ]s in B flat, 2 ]s, 2 ] in B flat and E flat, 2 ]s in B flat and E flat, ] and ]. | |||

| |filename=Ludwig van Beethoven - symphony no. 4 in b flat major, op. 60 - i. adagio - allegro vivace.ogg|title=1st movement: Allegro vivace|description=Performed by the Skidmore College Orchestra, courtesy of ]}} | |||

| The first movement is in {{music|time|2|2}} time. Like those of the ], ], and ] of Beethoven's nine symphonies, it has a slow introduction. ] described it as a "mysterious introduction which hovers around ]s, tip-toeing its tenuous weight through ambiguous unrelated keys and so reluctant to settle down into its final B{{music|flat}} major."<ref>{{YouTube|DAVt299d6kY|Leonard Bernstein Discusses Beethoven's Fourth Symphony}}</ref> It begins in B{{music|flat}} minor with a low B{{music|flat}}, played ] and ] by the strings, followed by a long-held chord in the wind, during which the strings move slowly in the minor. | |||

| ] | |||

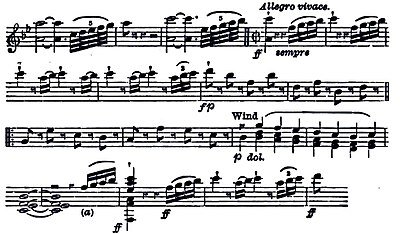

| The quiet introduction is thirty-eight bars long, and is followed by a fortissimo repetition of the chord of F, leading into the allegro vivace first subject of the main, ] part of the movement, described by ] as "gaiety itself, and most original gaiety":<ref>Grove, p. 105</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| The second subject is, in the words of ], "a conversation between the bassoon, the oboe, and the flute."<ref name=t51>Tovey, p. 51</ref> The development section takes the tonality towards the remote key of B major before returning to the tonic B{{music|flat}}, and the recapitulation and coda follow the conventional classical form.<ref name=t51/> | |||

| == |

=== II. Adagio === | ||

| {{listen|type=music|help=no | |||

| There are four ]: | |||

| |filename=Ludwig van Beethoven - symphony no. 4 in b flat major, op. 60 - ii. adagio.ogg|title=2nd movement: Adagio }} | |||

| The second movement, in {{music|time|3|4}} time (]), is a slow ]. The rhythmic figure of the opening theme persists throughout, and underpins, the whole movement: | |||

| ] | |||

| Tovey calls the first episode (or second subject) "a still more subtle melody": | |||

| ] | |||

| The main theme returns in an elaborate variation, followed by a middle episode and the reappearance of the varied main theme, now played by the flute. A regular recapitulation is followed by a coda that makes a final allusion to the main theme, and the timpani bring the movement to an end with the last appearance of the rhythmic theme with which the movement began. | |||

| === III. Scherzo-trio: Allegro vivace === | |||

| # '''] -- ] vivace''' | |||

| {{listen|type=music|help=no | |||

| # ''']''' | |||

| |filename=Ludwig van Beethoven - symphony no. 4 in b flat major, op. 60 - iii. allegro vivace.ogg|title=3rd movement: Allegro vivace }} | |||

| # '''] -- ] vivace''' | |||

| The movement, in {{music|time|3|4}} and B{{music|flat}} major, is headed ] in most printed scores, though not in Beethoven's original manuscript.<ref>Ferraguto, p. 157</ref> It is marked "Allegro vivace", and was originally to have been "allegro molto e vivace", but Beethoven deleted the "molto" in the autograph score.<ref>Grove, p. 118</ref> His ] marking is dotted ] = 100,<ref>Noorduin, p. 297</ref> at which brisk speed a traditional minuet would be impossible.<ref>Malloch, William. , ''Early Music'' 21, no. 3 (1993), pp. 437–444 {{subscription required}}</ref> Haydn had earlier wished that "someone would show us how to make a new minuet", and in this symphony, as in the ], Beethoven "forsook the spirit of the minuet of his predecessors, increased its speed, broke through its formal and antiquated mould, and out of a mere dance-tune produced a ''Scherzo''". (Grove).<ref name=g12>Grove, p. 12</ref> | |||

| # ''']''' | |||

| ] | |||

| In the Fourth Symphony (and later, in the ]) Beethoven further departed from the traditional minuet-trio-minuet form by repeating the trio after the second rendition of the scherzo section, and then bringing the scherzo back for a third hearing.<ref>Grove, p. 121</ref> The final repetition of the scherzo is abridged, and in the coda the two horns "blow the whole movement away" (Tovey). | |||

| === IV. Allegro ma non troppo === | |||

| The work takes about 33 minutes to perform. | |||

| {{listen|type=music|help=no | |||

| |filename=Ludwig van Beethoven - symphony no. 4 in b flat major, op. 60 - iv. allegro ma non troppo.ogg|title=4th movement:Allegro ma non troppo}} | |||

| The last movement is in {{music|time|2|4}} time in B{{music|flat}} major. The tempo marking is Allegro ma non troppo; this, like that of the third movement, is an afterthought on Beethoven's part: the original tempo indication in the autograph score is an unqualified "allegro". The composer added (in red chalk) "ma non troppo" – i.e. but not too much so.<ref>Grove, p. 122</ref> The movement is in a playful style that the composer called {{lang|de|aufgeknöpft}} (unbuttoned).<ref>Grove, p. 124</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| After some 340 bars of what Grove describes as a '']'', Beethoven concludes the symphony with the Haydnesque device of playing the main theme at half speed, interrupted by pauses, before a final fortissimo flourish.<ref>Grove, p. 125</ref> | |||

| == |

==Reception== | ||

| As usual by this stage of the composer's career, the symphony divided opinion among those who heard early performances. In 1809 ], never an admirer of Beethoven, wrote: | |||

| ] mode, opening theme was lead by strings, while the highest note was made by ], and there have secretly and quiet in the Adagio theme. There have quietly and longest opening tune, then quiet, dim, thoughtful and exploring ideas. There have a rapid change in joyful mood as the allegro part appeared, and a small fancy theme is also take the end in this rhythm movement. The dark mood in this movement didn't alleviated until the music suddenly bursts into vigorous and exuberant life. On the other hand, the striking contrast also appeared from quietly and joyfully. | |||

| :First a slow movement full of short disjointed unconnected ideas, at the rate of three or four notes per quarter of an hour; then a mysterious roll of the drum and passage of the violas, seasoned with the proper quantity of pauses and ritardandos; and to end all a furious finale, in which the only requisite is that there should be no ideas for the hearer to make out, but plenty of transitions from one key to another – on to the new note at once! never mind modulating! – above all things, throw rules to the winds, for they only hamper a genius.<ref>'']'', December 1809, ''Quoted'' in Grove, p. 97</ref> | |||

| Other critics were less hostile, praising the composer's "richness of ideas, bold originality and fullness of power" though finding the Fourth and the works premiered alongside it "rough diamonds".<ref>''Quoted'' in Ferraguto, p. 24</ref> Beethoven's biographer ] later recalled the Fourth as being a great success from the outset, although later scholars have expressed reservations about his reliability.<ref>Ferraguto, pp. 25–26</ref> | |||

| When Beethoven's younger contemporary ] heard the symphony he wrote that the slow movement was the work of the ], and not that of a human.<ref>Thompson, p. 172</ref> Nonetheless, by the time Berlioz was writing musical criticism, the Fourth was already less often played than other Beethoven symphonies. ] is said to have called the Fourth Symphony "a slender Greek maiden between two Norse giants",{{refn|In a 2012 study of the Symphony the musicologist Mark Ferraguto casts doubt on whether the phrase can reliably be attributed to Schumann. Ferraguto suggests that it originated in Grove's gloss on, or misremembering of, words actually used by Schumann.<ref>Ferraguto, pp.</ref>|group=n}} and it was an important influence on his ].<ref name=f45>Ferraguto, pp. 45–46</ref> Mendelssohn loved the Fourth, and programmed it when he was conductor of the ]. But their enthusiasm was not shared by the wider musical public. As early as 1831 a British critic noted that the Fourth was the "least frequently brought forward" of the first six, though, in his view "not inferior to any".<ref>"Music: Philharmonic Society", ''London literary gazette and journal of belles lettres, arts, sciences, etc. for the year 1831'', ''quoted'' in Ferraguto, p. 12</ref> In 1838 the French impresario ] called the Fourth sublime and regretted that in Paris it was not merely neglected but denigrated.<ref>Ferraguto, p. 12</ref> In 1896 Grove commented that the work had "met with scant notice in some of the most prominent works on Beethoven".<ref name=g97/> | |||

| ===2nd Movement=== | |||

| In the 20th century, writers continued to contrast the Fourth with the ''Eroica'' and the Fifth. In a study of the Fourth written in 2012 Mark Ferraguto quotes a 1994 description of the work as "a rich, verdant valley of ] expressiveness … poised between the two staggering yang peaks of the Third and the Fifth".<ref>Ferraguto, pp. 51–52</ref> | |||

| ===3rd Movement=== | |||

| According to the musicologist ] of the ]: | |||

| ===4th Movement=== | |||

| :If ''any'' of Beethoven's contemporaries had written this symphony, it would be considered that composer's masterwork, and that composer would be remembered ''forever'' for this symphony, and this symphony would be played – often – as an example of that composer's great work. As it is, for Beethoven, it is a work in search of an audience. It's the least known and least appreciated of the nine.<ref>Greenberg, Part 2: Lecture 14: "Symphony No. 4: Consolidation of the New Aesthetic IV"</ref> | |||

| == |

==Recordings== | ||

| Although all nine of Beethoven's symphonies are widely performed, the Fourth is less often performed than some of the others. | |||

| The symphony has been recorded, in the studio and in concert performances, more than a hundred times.<ref name=red>Ford, pp. 127–128</ref> Early recordings were mostly issued as single sets, sometimes coupled with another Beethoven symphony, such as the Second. More recently, recordings of the Fourth have often been issued as part of complete cycles of the Beethoven symphonies.<ref name=red/><ref name=im/> | |||

| ==Performance== | |||

| The sound files are from a performance by the ] Orchestra. | |||

| ] recordings, made in the era of 78 rpm discs or mono LPs, include a 1933 set with ] conducting the ], a 1939 version by the ] conducted by ], recordings from the 1940s conducted by ], ] and ], and from the early 1950s under ] (1951) and ] (1952).<ref name=red/><ref>, ''Audiophile Audition'', 24 November 2017</ref> | |||

| {{sample box start variation 2|First movement}} | |||

| {{listen|filename=Ludwig van Beethoven - symphony no. 4 in b flat major, op. 60 - i. adagio - allegro vivace.ogg|title=1st movement: Allegro vivace|description=Performed by the Skidmore College Orchestra. Music courtesy of |format=]}} | |||

| {{sample box end}} | |||

| Recordings from the ] LP era of the mid-1950s to the 1970s include those conducted by ] (1957), ] (1959), ] (1963) and ] (1966).<ref name=red/><ref name=im/><ref>Stuart, Philip. , AHRC Research Centre for the History and Analysis of Recorded Music. Retrieved 22 August 2019</ref> | |||

| {{sample box start variation 2|Second movement}} | |||

| {{listen|filename=Ludwig van Beethoven - symphony no. 4 in b flat major, op. 60 - ii. adagio.ogg|title=2nd movement: Adagio|description=Performed by the Skidmore College Orchestra. Music courtesy of |format=]}} | |||

| {{sample box end}} | |||

| The late 1950s and early 1960s saw the first recordings based on recent musicological ideas of authentic early-19th-century performance practice: ] (1958) and ] (1961) conducted sets of the symphonies attempting to follow Beethoven's metronome markings, which up to then had been widely regarded as impossibly fast.<ref>Taruskin, pp. 227–229</ref> These pioneering efforts were followed in later decades by recordings of performances in what was currently regarded as authentic style, often played by specialist ensembles on old instruments, or replicas of them, playing at about a ] below modern concert pitch. Among conductors of such versions of the Fourth Symphony have been ] (1986), ] (1988), ] (1991) and ] (1994).<ref name=red/> | |||

| {{sample box start variation 2|Third movement}} | |||

| {{listen|filename=Ludwig van Beethoven - symphony no. 4 in b flat major, op. 60 - iii. allegro vivace.ogg|title=3rd movement: Allegro molto e vivace|description=Performed by the Skidmore College Orchestra. Music courtesy of |format=]}} | |||

| {{sample box end}} | |||

| More recently some conductors of modern symphony or chamber orchestras have recorded the Fourth (along with other Beethoven symphonies), drawing to a greater or lesser degree on the practices of the specialist groups. Among these are ] (1992), and ] (2007).<ref name=im/> In a survey of all available recordings in 2015 for ] the top recommended version was in this category: the ], conducted by ].<ref>, BBC. Retrieved 27 August 2019.</ref> Among conductors of more traditional recordings have been ] (1980), ] (2000) and ] (2006).<ref name=im>March ''et al'', p. 116–124</ref> | |||

| {{sample box start variation 2|Fourth movement}} | |||

| {{listen|filename=Ludwig van Beethoven - symphony no. 4 in b flat major, op. 60 - iv. allegro ma non troppo.ogg|title=4th movement:Allegro ma non troppo|description=Performed by the Skidmore College Orchestra. Music courtesy of |format=]}} | |||

| {{sample box end}} | |||

| ==Notes== | ==Notes, references and sources== | ||

| ===Notes=== | |||

| <references/> | |||

| {{Reflist|group=n}} | |||

| ===References=== | |||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| ===Sources=== | |||

| * {{cite book | last=Anderson | first= Emily| title=The Letters of Beethoven | year=1985 | volume=3|location=London | publisher=Macmillan | isbn= 978-0-333-39833-3}} | |||

| * {{cite book | last= Ferraguto | first= Mark Christopher | title= Beethoven's Fourth Symphony: Reception, Aesthetics, Performance History| year= 2012| location= Ithaca| publisher= Cornell University|url= https://ecommons.cornell.edu/bitstream/handle/1813/31098/mcf29.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y |oclc= 826932734}} | |||

| * {{cite book | last= Ford| first=Gary | title=RED Classical Catalogue | year=2001 | location= London| publisher=Retail Entertainment Data Publishing and Gramophone | isbn= 978-1-900105-22-4}} | |||

| * {{cite book | last= Greenberg | first= Robert | title= The Symphonies of Beethoven. Part 2 of 4| year= 2003| location= Chantilly | publisher= Teaching Company | isbn= 978-1-56585-700-1}} | |||

| * {{cite book | last= Grove | first= George|author-link=George Grove| title= Beethoven and His Nine Symphonies| year= 1903| orig-year=1896| publisher= Novello|url=https://archive.org/details/beethovenhisnine00grov/page/96| oclc= 491303365}} | |||

| * {{cite book | last= Lockwood | first= Lewis|author-link=Lewis Lockwood| title= Beethoven's Symphonies: An Artistic Vision| year= 2017 | location= New York | publisher= W. W. Norton | isbn= 978-0-393-35385-3}} | |||

| * {{cite book| last1=March|first1=Ivan|author1-link=Ivan March|author2=]|author3=Robert Layton|author3-link=Robert Layton (musicologist)|author4=Paul Czajkowski| title=]|chapter=Beethoven, Ludwig van – Symphony 4|chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/penguinguidetore00lond/page/116/mode/2up|year=2008|location=London|publisher= Penguin|isbn= 978-0-1410-3336-5|chapter-url-access=registration|via=]}} | |||

| * {{cite book | last= Netl | first= Paul | title= Beethoven Handbook| year= 1976| location= New York | publisher= Frederick Ungar }} | |||

| * {{cite book | last= Noorduin | first= Marten A.| title= Beethoven's Tempo Indications| year= 2016| location=Manchester | publisher= University of Manchester |url=https://www.research.manchester.ac.uk/portal/files/54586757/FULL_TEXT.PDF| oclc= 1064358078}} | |||

| * {{cite book | last= Steinberg | first= Michael|author-link=Michael Steinberg (music critic)| title= The Symphony: A Listener's Guide| url= https://archive.org/details/symphonylistener00stei | year= 1995| location= Oxford | publisher= Oxford University Press | isbn= 978-0-19-506177-2 }} | |||

| * {{cite book | last= Taruskin | first= Richard | author-link=Richard Taruskin|title= Text and Act: Essays on Music and Performance| year=1995 | location= New York | publisher= Oxford University Press | isbn=978-0-19-509458-9 }} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Thompson|first=Oscar| title= How to Understand Music| year=1935|publisher= Dial Press|location=New York|oclc= 377014 }} | |||

| * {{cite book | last= Tovey | first= Donald|author-link=Donald Tovey| title= Symphonies and Other Orchestral Works| year= 1990 | location= Oxford and New York | publisher= Oxford University Press | isbn=978-0-19-315147-5}} | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{Commons category|Symphony No. 4 (Beethoven)}} | |||

| *Analysis of the on the Page | |||

| *{{IMSLP|work=Symphony No.4, Op.60 (Beethoven, Ludwig van)|cname=Symphony No. 4}} | |||

| * of Beethoven's Fourth Symphony. | |||

| *Analysis of the {{usurped|1=}}, all-about-beethoven.com | |||

| * of Beethoven's Fourth Symphony, ], Indiana University School of Music | |||

| {{Beethoven symphonies|state=expanded}} | |||

| {{Template group | |||

| {{Portal bar|Classical music}} | |||

| |list = | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| {{Ludwig van Beethoven}} | |||

| {{Beethoven symphonies}} | |||

| }} | |||

| <!--Categories--> | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| <!--Other languages--> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 06:55, 21 December 2024

"Beethoven's 4th" redirects here. For the direct-to-video movie, see Beethoven's 4th (film).

The Symphony No. 4 in B♭ major, Op. 60, is the fourth-published symphony by Ludwig van Beethoven. It was composed in 1806 and premiered in March 1807 at a private concert in Vienna at the town house of Prince Lobkowitz. The first public performance was at the Burgtheater in Vienna in April 1808.

The symphony is in four movements. It is predominantly genial in tone, and has tended to be overshadowed by the weightier Beethoven symphonies that preceded and followed it – the Third Symphony (Eroica) and the Fifth. Although later composers including Berlioz, Mendelssohn and Schumann greatly admired the work it has not become as widely known among the music-loving public as the Eroica, the Fifth and other Beethoven symphonies.

Background

Beethoven spent the summer of 1806 at the country estate of his patron, Prince Lichnowsky, in Silesia. In September Beethoven and the Prince visited the house of one of the latter's friends, Count Franz von Oppersdorff, in nearby Oberglogau. The Count maintained a private orchestra, and the composer was honoured with a performance of his Second Symphony, written four years earlier. After this, Oppersdorff offered the composer a substantial sum to write a new symphony for him.

Beethoven had been working on what later became his Fifth Symphony, and his first intention may have been to complete it in fulfilment of the Count's commission. There are several theories about why, if so, he did not do this. According to George Grove, economic necessity obliged Beethoven to offer the Fifth (together with the Pastoral) jointly to Prince Lobkowitz and Count Razumovsky. Other commentators suggest that the Fourth was essentially complete before Oppersdorff's commission, or that the composer may not yet have felt ready to press on with "the radical and emotionally demanding Fifth", or that the count's evident liking for the more Haydnesque world of the Second Symphony prompted another work in similar vein.

The work is dedicated to "the Silesian nobleman Count Franz von Oppersdorff". Although Oppersdorff had paid for exclusive rights to the work for its first six months, his orchestra did not give the first performance. The symphony was premiered in March 1807 at a private concert in Vienna at the town house of Prince Lobkowitz, another of Beethoven's patrons. The first public performance was at the Burgtheater in Vienna in April 1808. The orchestral parts were published in March 1809, but the full score was not printed until 1821. The manuscript, which was for a time owned by Felix Mendelssohn, is now in the Berlin State Library and can be seen online.

Instrumentation

The symphony is scored for flute, two oboes, two clarinets in B♭, two bassoons, two horns in B♭ and E♭, two trumpets in B♭ and E♭, timpani and strings. It typically takes between 30 and 35 minutes to perform.

Analysis

In general the symphony is sunny and cheerful, with light instrumentation that for some listeners recalls the symphonies of Joseph Haydn, with whom Beethoven had studied a decade before. In a commentary on the symphony Grove comments that Haydn – who was still alive when the new symphony was first performed – might have found the work too strong for his taste. The Fourth Symphony contrasts with Beethoven's style in the previous Third Symphony (Eroica), and has sometimes been overshadowed by its massive predecessor and its fiery successor, the Fifth Symphony.

I. Adagio – Allegro vivace

Problems playing this file? See media help.

The first movement is in

2 time. Like those of the first, second, and seventh of Beethoven's nine symphonies, it has a slow introduction. Leonard Bernstein described it as a "mysterious introduction which hovers around minor modes, tip-toeing its tenuous weight through ambiguous unrelated keys and so reluctant to settle down into its final B♭ major." It begins in B♭ minor with a low B♭, played pizzicato and pianissimo by the strings, followed by a long-held chord in the wind, during which the strings move slowly in the minor.

The quiet introduction is thirty-eight bars long, and is followed by a fortissimo repetition of the chord of F, leading into the allegro vivace first subject of the main, sonata form part of the movement, described by Grove as "gaiety itself, and most original gaiety":

The second subject is, in the words of Donald Tovey, "a conversation between the bassoon, the oboe, and the flute." The development section takes the tonality towards the remote key of B major before returning to the tonic B♭, and the recapitulation and coda follow the conventional classical form.

II. Adagio

The second movement, in

4 time (E♭ major), is a slow rondo. The rhythmic figure of the opening theme persists throughout, and underpins, the whole movement:

Tovey calls the first episode (or second subject) "a still more subtle melody":

The main theme returns in an elaborate variation, followed by a middle episode and the reappearance of the varied main theme, now played by the flute. A regular recapitulation is followed by a coda that makes a final allusion to the main theme, and the timpani bring the movement to an end with the last appearance of the rhythmic theme with which the movement began.

III. Scherzo-trio: Allegro vivace

The movement, in

4 and B♭ major, is headed Menuetto in most printed scores, though not in Beethoven's original manuscript. It is marked "Allegro vivace", and was originally to have been "allegro molto e vivace", but Beethoven deleted the "molto" in the autograph score. His metronome marking is dotted minim = 100, at which brisk speed a traditional minuet would be impossible. Haydn had earlier wished that "someone would show us how to make a new minuet", and in this symphony, as in the First, Beethoven "forsook the spirit of the minuet of his predecessors, increased its speed, broke through its formal and antiquated mould, and out of a mere dance-tune produced a Scherzo". (Grove).

In the Fourth Symphony (and later, in the Seventh) Beethoven further departed from the traditional minuet-trio-minuet form by repeating the trio after the second rendition of the scherzo section, and then bringing the scherzo back for a third hearing. The final repetition of the scherzo is abridged, and in the coda the two horns "blow the whole movement away" (Tovey).

IV. Allegro ma non troppo

The last movement is in

4 time in B♭ major. The tempo marking is Allegro ma non troppo; this, like that of the third movement, is an afterthought on Beethoven's part: the original tempo indication in the autograph score is an unqualified "allegro". The composer added (in red chalk) "ma non troppo" – i.e. but not too much so. The movement is in a playful style that the composer called aufgeknöpft (unbuttoned).

After some 340 bars of what Grove describes as a perpetuum mobile, Beethoven concludes the symphony with the Haydnesque device of playing the main theme at half speed, interrupted by pauses, before a final fortissimo flourish.

Reception

As usual by this stage of the composer's career, the symphony divided opinion among those who heard early performances. In 1809 Carl Maria von Weber, never an admirer of Beethoven, wrote:

- First a slow movement full of short disjointed unconnected ideas, at the rate of three or four notes per quarter of an hour; then a mysterious roll of the drum and passage of the violas, seasoned with the proper quantity of pauses and ritardandos; and to end all a furious finale, in which the only requisite is that there should be no ideas for the hearer to make out, but plenty of transitions from one key to another – on to the new note at once! never mind modulating! – above all things, throw rules to the winds, for they only hamper a genius.

Other critics were less hostile, praising the composer's "richness of ideas, bold originality and fullness of power" though finding the Fourth and the works premiered alongside it "rough diamonds". Beethoven's biographer Anton Schindler later recalled the Fourth as being a great success from the outset, although later scholars have expressed reservations about his reliability.

When Beethoven's younger contemporary Hector Berlioz heard the symphony he wrote that the slow movement was the work of the Archangel Michael, and not that of a human. Nonetheless, by the time Berlioz was writing musical criticism, the Fourth was already less often played than other Beethoven symphonies. Robert Schumann is said to have called the Fourth Symphony "a slender Greek maiden between two Norse giants", and it was an important influence on his First Symphony. Mendelssohn loved the Fourth, and programmed it when he was conductor of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra. But their enthusiasm was not shared by the wider musical public. As early as 1831 a British critic noted that the Fourth was the "least frequently brought forward" of the first six, though, in his view "not inferior to any". In 1838 the French impresario Louis-Désiré Véron called the Fourth sublime and regretted that in Paris it was not merely neglected but denigrated. In 1896 Grove commented that the work had "met with scant notice in some of the most prominent works on Beethoven".

In the 20th century, writers continued to contrast the Fourth with the Eroica and the Fifth. In a study of the Fourth written in 2012 Mark Ferraguto quotes a 1994 description of the work as "a rich, verdant valley of yin expressiveness … poised between the two staggering yang peaks of the Third and the Fifth".

According to the musicologist Robert Greenberg of the San Francisco Conservatory of Music:

- If any of Beethoven's contemporaries had written this symphony, it would be considered that composer's masterwork, and that composer would be remembered forever for this symphony, and this symphony would be played – often – as an example of that composer's great work. As it is, for Beethoven, it is a work in search of an audience. It's the least known and least appreciated of the nine.

Recordings

The symphony has been recorded, in the studio and in concert performances, more than a hundred times. Early recordings were mostly issued as single sets, sometimes coupled with another Beethoven symphony, such as the Second. More recently, recordings of the Fourth have often been issued as part of complete cycles of the Beethoven symphonies.

Monaural recordings, made in the era of 78 rpm discs or mono LPs, include a 1933 set with Felix Weingartner conducting the London Philharmonic Orchestra, a 1939 version by the BBC Symphony Orchestra conducted by Arturo Toscanini, recordings from the 1940s conducted by Willem Mengelberg, Serge Koussevitzky and Sir Thomas Beecham, and from the early 1950s under Georg Solti (1951) and Wilhelm Furtwängler (1952).

Recordings from the stereo LP era of the mid-1950s to the 1970s include those conducted by Otto Klemperer (1957), Pierre Monteux (1959), Herbert von Karajan (1963) and Hans Schmidt-Isserstedt (1966).

The late 1950s and early 1960s saw the first recordings based on recent musicological ideas of authentic early-19th-century performance practice: Hermann Scherchen (1958) and René Leibowitz (1961) conducted sets of the symphonies attempting to follow Beethoven's metronome markings, which up to then had been widely regarded as impossibly fast. These pioneering efforts were followed in later decades by recordings of performances in what was currently regarded as authentic style, often played by specialist ensembles on old instruments, or replicas of them, playing at about a semitone below modern concert pitch. Among conductors of such versions of the Fourth Symphony have been Christopher Hogwood (1986), Roger Norrington (1988), Frans Brüggen (1991) and John Eliot Gardiner (1994).

More recently some conductors of modern symphony or chamber orchestras have recorded the Fourth (along with other Beethoven symphonies), drawing to a greater or lesser degree on the practices of the specialist groups. Among these are Nikolaus Harnoncourt (1992), and Sir Charles Mackerras (2007). In a survey of all available recordings in 2015 for BBC Radio 3 the top recommended version was in this category: the Zurich Tonhalle Orchestra, conducted by David Zinman. Among conductors of more traditional recordings have been Leonard Bernstein (1980), Claudio Abbado (2000) and Bernard Haitink (2006).

Notes, references and sources

Notes

- The fee is variously described as "350 florins" and "500 gulden". Beethoven later received a separate fee of 1500 gulden from the publisher the Wiener Kunst- und Industrie-Comptoir. That sum covered the publishing rights to the symphony together with the Fourth Piano Concerto, the three Razumovsky Quartets, the Violin Concerto and the Coriolan Overture.

- Beethoven had to write to Oppersdorff apologising for this breach of their agreement. It is not known whether Oppersdorff's orchestra ever performed the work.

- As well as the tempi adopted by the performers, the playing time is affected by the decision to play or omit the exposition repeat in the first movement. This typically makes a difference of about 2½ minutes. Examples from the versions mentioned in the Recordings section are Klemperer and Monteux, who play the repeat and whose first movements last for 12:28 and 12:37 respectively, compared with Toscanini and Karajan, who omit the repeat and respectively take 9:57 and 9:55. The total playing time of the symphony in these four recordings is 35:49, 34:10, 29:59, and 31:09 respectively.

- In the Eroica the four movements consist of 691, 247, 442 and 473 bars; the Fourth consists of 498, 104, 397 and 355 – making the Fourth 499 bars shorter than its predecessor.

- In a 2012 study of the Symphony the musicologist Mark Ferraguto casts doubt on whether the phrase can reliably be attributed to Schumann. Ferraguto suggests that it originated in Grove's gloss on, or misremembering of, words actually used by Schumann.

References

- ^ Kemp, Linsday. Notes to LSO Live set LSO0098D

- ^ Grove, p. 97

- Anderson, p. 1426

- Albinsson, Staffan. "Early Music Copyrights: Did They Matter for Beethoven and Schumann?", International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music 43, no. 2 (2012), pp. 265–302 (subscription required)

- "Symphony No. 4 in B-flat major, Op. 60 Ludwig van Beethoven", New York Philharmonic. Retrieved 25 August 2019

- Netl, p. 262

- Rodda, Richard "Symphony No. 4 in B-flat major, Op. 60", Kennedy Center. Retrieved 25 August 2019

- Steinberg, pp. 19–24

- Huscher, Philip. "Ludwig van Beethoven – Symphony No. 4 in B-flat Major, Op. 60", Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Retrieved 25 August 2019

- ^ Grove, p. 96

- "Beethoven, Ludwig van: Sinfonien; orch; B-Dur; op.60, 1806", Staatsbibliothek, Berlin. Retrieved 26 August 2019

- Notes to CD sets Parlophone 0724356679559 (2003), Decca 00028948088942 (2015), Parlophone 5099972333457 (2013), and DG 00028947771579 (2007)

- Grove, pp. 97–99

- Lockwood, p. 80

- Leonard Bernstein Discusses Beethoven's Fourth Symphony on YouTube

- Grove, p. 105

- ^ Tovey, p. 51

- Ferraguto, p. 157

- Grove, p. 118

- Noorduin, p. 297

- Malloch, William. "The Minuets of Haydn and Mozart: Goblins or Elephants?", Early Music 21, no. 3 (1993), pp. 437–444 (subscription required)

- Grove, p. 12

- Grove, p. 121

- Grove, p. 122

- Grove, p. 124

- Grove, p. 125

- Morgenblatt für die gebildeten Stände, December 1809, Quoted in Grove, p. 97

- Quoted in Ferraguto, p. 24

- Ferraguto, pp. 25–26

- Thompson, p. 172

- Ferraguto, pp.

- Ferraguto, pp. 45–46

- "Music: Philharmonic Society", London literary gazette and journal of belles lettres, arts, sciences, etc. for the year 1831, quoted in Ferraguto, p. 12

- Ferraguto, p. 12

- Ferraguto, pp. 51–52

- Greenberg, Part 2: Lecture 14: "Symphony No. 4: Consolidation of the New Aesthetic IV"

- ^ Ford, pp. 127–128

- ^ March et al, p. 116–124

- "Beethoven: Symphony No. 4 & No. 7 – Boston Symphony Orchestra/ Serge Koussevitzky – Pristine Audio", Audiophile Audition, 24 November 2017

- Stuart, Philip. Decca Classical, 1929–2009, AHRC Research Centre for the History and Analysis of Recorded Music. Retrieved 22 August 2019

- Taruskin, pp. 227–229

- "Building a Library Database 1999–2018", BBC. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

Sources

- Anderson, Emily (1985). The Letters of Beethoven. Vol. 3. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-39833-3.

- Ferraguto, Mark Christopher (2012). Beethoven's Fourth Symphony: Reception, Aesthetics, Performance History (PDF). Ithaca: Cornell University. OCLC 826932734.

- Ford, Gary (2001). RED Classical Catalogue. London: Retail Entertainment Data Publishing and Gramophone. ISBN 978-1-900105-22-4.

- Greenberg, Robert (2003). The Symphonies of Beethoven. Part 2 of 4. Chantilly: Teaching Company. ISBN 978-1-56585-700-1.

- Grove, George (1903) . Beethoven and His Nine Symphonies. Novello. OCLC 491303365.

- Lockwood, Lewis (2017). Beethoven's Symphonies: An Artistic Vision. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-35385-3.

- March, Ivan; Edward Greenfield; Robert Layton; Paul Czajkowski (2008). "Beethoven, Ludwig van – Symphony 4". The Penguin Guide to Recorded Classical Music. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-1410-3336-5 – via Internet Archive.

- Netl, Paul (1976). Beethoven Handbook. New York: Frederick Ungar.

- Noorduin, Marten A. (2016). Beethoven's Tempo Indications (PDF). Manchester: University of Manchester. OCLC 1064358078.

- Steinberg, Michael (1995). The Symphony: A Listener's Guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-506177-2.

- Taruskin, Richard (1995). Text and Act: Essays on Music and Performance. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509458-9.

- Thompson, Oscar (1935). How to Understand Music. New York: Dial Press. OCLC 377014.

- Tovey, Donald (1990). Symphonies and Other Orchestral Works. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-315147-5.

External links

- Symphony No. 4: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Analysis of the Beethoven Symphony No. 4, all-about-beethoven.com

- "Eulenburg full score" of Beethoven's Fourth Symphony, William and Gayle Cook Music Library, Indiana University School of Music

| Symphonies by Ludwig van Beethoven | |

|---|---|

| Early symphonies | |

| Middle symphonies | |

| Late symphonies |

Hypothetical: No. 10 in E♭ major |