| Revision as of 14:07, 25 January 2008 view sourceSnowolf (talk | contribs)Administrators52,006 editsm Reverted edits by 209.198.84.222 (talk) to last version by CounterFX← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 15:51, 1 January 2025 view source FuzzyMagma (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, New page reviewers31,610 edits Himyarite-Axumite war of 270-272Tag: Visual edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Polity in Africa and Arabia before 960}} | |||

| {{FixHTML|beg}} | |||

| {{ |

{{pp|small=yes}} | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=August 2023}} | |||

| {{FixHTML|mid}} | |||

| {{Infobox country | |||

| | native_name = {{native name|gez|መንግሥተ አክሱም}}<br />{{native name|xsa|𐩱𐩫𐩪𐩣}}<br />{{native name|grc|Βασιλεία τῶν Ἀξωμιτῶν}} | |||

| | conventional_long_name = Kingdom of Aksum | |||

| | common_name = Aksum or Axum | |||

| | era = ] to ] | |||

| | government_type = ] | |||

| | common_languages = {{plainlist| | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ]<ref name="donaldfairbairn">{{cite book |title=The Global Church—The First Eight Centuries From Pentecost Through the Rise of Islam|first= Donald |last=Fairbairn|publisher=Zondervan Academic|year=2021|pages=146 |isbn= 978-0310097853 }}</ref> | |||

| * ]<ref name="sourcebooks.fordham.edu">{{cite web |title=The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean by a Merchant of the First Century | url=https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/ancient/periplus.asp | website=Fordham University Internet History Sourcebooks, chapters 4 and 5}}</ref>}} (from 1st century)<ref>{{Cite web|date=2020-11-02|title=Snowden Lectures: Stanley Burstein, When Greek was an African Language|url=https://chs.harvard.edu/curated-article/snowden-lectures-stanley-burstein-when-greek-was-an-african-language/|access-date=2022-02-23|website=The Center for Hellenic Studies}}</ref> | |||

| <br />''Various''{{efn|], ], ], ], ], and other languages.<ref name="molefikete">{{cite book |title=The African American People A Global History|first=Molefi Kete |last=Asante|publisher=Taylor & Francis|year=2013|pages=13}}</ref>}} | |||

| | year_start = 1st century | |||

| | event_end = Collapse | |||

| | year_end = 960 AD | |||

| | life_span = 1st century{{snd}}960 AD | |||

| | event1 = ] | |||

| | date_event1 = 3rd century | |||

| | event2 = ]'s conversion to ] | |||

| | date_event2 = 325 or 328 | |||

| | event3 = ]'s conquest of the ] | |||

| | date_event3 = 330 | |||

| | event4 = ] | |||

| | date_event4 = 520 | |||

| | event5 = ] | |||

| | date_event5 = 570 | |||

| | event6 = ] | |||

| | date_event6 = 613-615 | |||

| | event7 = ] | |||

| | date_event7 = 7th century | |||

| | p1 = Dʿmt | |||

| | s1 = Zagwe dynasty | |||

| | image_coat = Endubis.jpg | |||

| | coa_size = 250px | |||

| | symbol_type = ] depicting ] | |||

| | capital = {{plainlist| | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] (after {{Circa|800}})}} | |||

| | currency = ] | |||

| | leader1 = ] (first known) ] (according to tradition) | |||

| | year_leader1 = {{Circa|100 AD}} | |||

| | leader2 = ] (last) | |||

| | year_leader2 = 917 or 940-960 | |||

| | title_leader = ]{{\}}] | |||

| | religion = {{indented plainlist| | |||

| * ] (]; official after mid-4th century)<ref name="vincentkhapoya">{{cite book |title=The African Experience | |||

| |first=Vincent |last=Khapoya|publisher=Routledge|year=2015|page=71 |isbn=978-0205851713}}</ref> | |||

| * ] (before 350)<ref>Turchin, Peter and Jonathan M. Adams and Thomas D. Hall: "East-West Orientation of Historical Empires and Modern States", p. 222. Journal of World-Systems Research, Vol. XII, No. II, 2006</ref>}} | |||

| * ] (before 350) | |||

| | stat_area1 = 1250000 | |||

| | stat_year1 = 350 | |||

| | ref_area1 = <ref>{{cite journal |last1=Turchin |first1=Peter |author-link=Peter Turchin |last2=Adams |first2=Jonathan M. |last3=Hall |first3=Thomas D. |date=December 2006 |title=East-West Orientation of Historical Empires |url=http://peterturchin.com/PDF/Turchin_Adams_Hall_2006.pdf |url-status=live |journal=] |volume=12 |issue=2 |pages=222 |issn=1076-156X |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200707181315/http://peterturchin.com/PDF/Turchin_Adams_Hall_2006.pdf| archive-date=2020-07-07 |access-date=2023-06-05}}</ref> | |||

| | stat_area2 = 2500000 | |||

| | stat_year2 = 525 | |||

| | demonym = Aksumite, Ethiopian, ] | |||

| | s2 = Sasanian Yemen | |||

| | today = {{hlist|]|]|]|]|]|]|]}} | |||

| }} | |||

| The '''Kingdom of Aksum''' ({{langx|gez|አክሱም|ʾÄksum}}; {{langx|xsa|𐩱𐩫𐩪𐩣}}, {{smallcaps|ʾkšm}}; {{langx|grc|Ἀξωμίτης|Axōmítēs}}) also known as the '''Kingdom of Axum''', or the '''Aksumite Empire''', was a kingdom in ] and ] from ] to the ], based in what is now northern ] and ], and spanning present-day ] and ]. Emerging from the earlier ] civilization, the kingdom was founded in the 1st century.<ref>, UNESCO {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231008220415/http://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/6477/|date=2023-10-08}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last= Munro-Hay|first= Stuart|year= 1991|title= Aksum: An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity|location= Edinburgh|publisher= Edinburgh University Press|page= 69|isbn= 0748601066}}</ref> The city of ] served as the kingdom's capital for many centuries until it relocated to ]<ref>{{Cite book|last=Burstein|first=Stanley|chapter=Africa: states, empires, and connections|year=2015|doi=10.1017/cbo9781139059251.025|title=The Cambridge World History: Volume 4: A World with States, Empires and Networks 1200 BCE–900 CE|volume=4|pages=631–661|editor-last=Benjamin|editor-first=Craig|series=The Cambridge World History|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-1-139-05925-1}}</ref> in the 9th century due to declining trade connections and recurring external invasions.<ref name="Phillipson48">{{cite book |last= Phillipson|first= David W.|year= 2012|title= Foundations of an African Civilisation: Aksum & the Northern Horn, 1000 BC - AD 1300|location= Woodbridge|publisher= James Currey|page= 48|isbn= 978-1-84701-041-4}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|title=Rise and Fall of Axum, Ethiopia: A Geo-Archaeological Interpretation |journal=American Antiquity |volume=46 |issue=3 |pages=471–495 |last=Butzer |first=Karl W. |publisher= Cambridge University Press|year=1981 |jstor=280596 |s2cid=162374800 }}</ref> | |||

| ]) until circa the later part of the ] when it succumbed to a long decline against pressures from the various Islamic ] leagued against it.]] | |||

| The Kingdom of Aksum was considered one of the four ]s of the 3rd century by the Persian prophet ], alongside ], ], and ].<ref>{{cite book |last= Munro-Hay|first= Stuart|year= 1991|title= Aksum: An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity|location= Edinburgh|publisher= Edinburgh University Press|page= 17|isbn= 0748601066}}</ref> Aksum continued to expand under the reign of ] ({{circa|200–230}}), who was the first king to be involved in South Arabian affairs. His reign resulted in the control of much of western ], such as the ], ], ], ] (until {{circa|230|lk=no}}), and parts of ] territory around ] in the northern ] until a joint Himyarite-Sabean alliance pushed them out. Aksum-Himyar conflicts persisted throughout the 3rd century. During the reign of ] (270–310), Aksum began minting ] that have been excavated as far away as ] and southern India.<ref>{{cite journal |last= Hahn|first= Wolfgang|year= 2000|title= Askumite Numismatics - A critical survey of recent Research|url= https://www.persee.fr/doc/numi_0484-8942_2000_num_6_155_2289|journal= Revue Numismatique|volume= 6|issue= 155|pages= 281–311|doi=10.3406/numi.2000.2289|access-date= 9 September 2021}}</ref> | |||

| {{FixHTML|mid}} | |||

| As the kingdom became a major power on the ] and gained a monopoly of ], it entered the ]. Due to its ties with the Greco-Roman world, Aksum ] in the mid-4th century, under ] (320s{{snd}}{{circa|lk=no|360}}).<ref name="Derat34">{{cite book |last=Derat |first=Marie-Laure |title=A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea |year=2020 |publisher=Brill |isbn=978-90-04-41958-2 |editor-last=Kelly |editor-first=Samantha |location=Leiden |page=34 |chapter=Before the Solomonids: Crisis, Renaissance and the Emergence of the Zagwe Dynasty (Seventh–Thirteenth Centuries)}}</ref> Following their Christianization, the Aksumites ceased construction of ].<ref name="Phillipson48" /> The kingdom continued to expand throughout ], conquering ] under Ezana in 330 for a short period of time and inheriting from it the Greek exonym "Ethiopia".<ref>{{cite book |last= Munro-Hay|first= Stuart|year= 1991|title= Aksum: An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity|location= Edinburgh|publisher= Edinburgh University Press|pages= 15–16|isbn= 0748601066}}</ref> | |||

| ], 227-235 AD. ]. The left one reads in Greek "AΧWMITW BACIΛEYC", "King of Axum". The right one reads in Greek: ΕΝΔΥΒΙC ΒΑCΙΛΕΥC, "King Endybis".]] | |||

| Aksumite dominance in the Red Sea culminated during the reign of ] (514–542), who, at the behest of the Byzantine Emperor ], invaded the ] in Yemen in order to end the ] perpetrated by the Jewish king ]. With the annexation of Himyar, the Kingdom of Aksum was at its largest territorial extent, being around {{cvt|2,500,000|km2}}. However, the territory was lost in the ].<ref>{{cite book |last= Munro-Hay|first= Stuart|date= 1991|title= Aksum: An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity|location= Edinburgh|publisher= Edinburgh University Press|page= 55|isbn= 0748601066}}</ref> Aksum held on to Southern Arabia from 520 until 525 when Sumyafa Ashwa was deposed by ]. | |||

| {{FixHTML|mid}} | |||

| The kingdom's slow decline had begun by the 7th century, at which point currency ceased to be minted. The Persian (and later Muslim) presence in the Red Sea caused Aksum to suffer economically, and the population of the city of Axum shrank. Alongside environmental and internal factors, this has been suggested as the reason for its decline. Aksum's final three centuries are considered a dark age, and through uncertain circumstances, the kingdom collapsed around 960.<ref name="Derat34" /> Despite its position as one of the foremost empires of late antiquity, the Kingdom of Aksum fell into obscurity as Ethiopia remained isolated throughout the Late Middle Ages.<ref name="medievalethiopianorthodoxchurch">{{cite book |last1=Fritsch |first1=Emmanuel |title=A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea |last2=Kidane |first2=Habtemichael |date=2020 |publisher=Brill |isbn=978-90-04-41958-2 |editor-last=Kelly |editor-first=Samantha |location=Leiden |page=169 |chapter=The Medieval Ethiopian Orthodox Church and Its Liturgy}}</ref> | |||

| ] at the end of ]'s reign in the 3rd century AD.]] | |||

| == Etymology == | |||

| {{FixHTML|end}} | |||

| ] believed that the word ''Aksum'' derives from a Semitic root, and means 'a green and dense garden' or 'full of grass'.<ref name="Mordechai32">{{cite book |last=Selassie |first=Sergew Hable |url= |title=Ancient and Medieval Ethiopian History to 1270 |publisher= |year=1972 |isbn= |location= |pages=68 |language= |issn= |oclc= |access-date=}}</ref> | |||

| The '''Aksumite Empire''' or '''Axumite Empire''' (sometimes called the Kingdom of Aksum or Axum), (]: አክሱም), was an important trading nation in northeastern ], growing from the proto-Aksumite period ca. ] to achieve prominence by the ] AD. It is also the alleged resting place of the Ark of the Covenant and the home of the Queen of Sheba. | |||

| {{TOCnestright}} | |||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| ]]] | |||

| Located in northern ] and ], Aksum was deeply involved in the trade network between ] and the ]. | |||

| ===Early history=== | |||

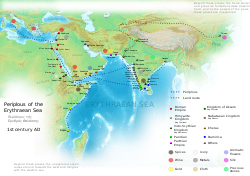

| Aksum is mentioned in the 1st century AD ] as an important market place for ivory, which was exported throughout the ancient world: | |||

| Before the establishment of Axum, the Tigray plateau of northern Ethiopia was home to a kingdom known as ]. Archaeological evidence shows that the kingdom was influenced by ] from modern-day Yemen; scholarly consensus had previously been that Sabaeans had been the founders of Semitic civilization in Ethiopia, though this has now been refuted, and their influence is considered to have been minor.<ref name="Munro-Hay57">{{Cite book|url=http://www.dskmariam.org/artsandlitreature/litreature/pdf/aksum.pdf|title=Aksum: An African Civilization of Late Antiquity|last=Munro-Hay|first=Stuart|publisher=University Press|year=1991|location=Edinburgh|page=57|access-date=February 1, 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130123223427/http://www.dskmariam.org/artsandlitreature/litreature/pdf/aksum.pdf|archive-date=January 23, 2013|url-status=dead}}</ref>{{Efn| According to Munro-Hay, "The arrival of Sabaean influences does not represent the beginning of Ethiopian civilisation.... Semiticized Agaw peoples are thought to have migrated from south-eastern Eritrea possibly as early as 2000 BC, bringing their 'proto-Ethiopic' language, ancestor of Geʽez and the other Ethiopian Semitic languages, with them; and these and other groups had already developed specific cultural and linguistic identities by the time any Sabaean influences arrived."<ref name="Munro-Hay57" />}}<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.addistribune.com/Archives/2003/01/17-01-03/Let.htm|title=Let's Look Across the Red Sea I|last=Pankhurst|first=Richard K. P.|date=January 17, 2003|newspaper=Addis Tribune|access-date=February 1, 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060109162335/http://www.addistribune.com/Archives/2003/01/17-01-03/Let.htm|archive-date=January 9, 2006|author-link=Richard Pankhurst (academic)}}</ref> The Sabaean presence likely lasted only for a matter of decades, but their influence on later Aksumite civilization included the adoption of ], which developed into ], and ].<ref name= Munro6162>{{cite book |last= Munro-Hay|first= Stuart|date= 1991|title= Aksum: An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity|location= Edinburgh|publisher= Edinburgh University Press|pages= 61–62|isbn= 0748601066}}</ref> | |||

| {{quote|"From that place to the city of the people called Auxumites there is a five days' journey more; to that place all the ivory is brought from the country beyond the Nile through the district called Cyeneum, and thence to Adulis....|], Chap.4}} | |||

| The initial centuries of Aksum's development, transitioning from a modest regional center to a significant power, remain largely obscure. Stone Age artifacts have been unearthed at ], two kilometers west of ]. Excavations on Beta Giyorgis, a hill to the northwest of Aksum, validate the pre-Aksumite roots of a settlement in the vicinity of Aksum, dating back to approximately the 7th to 4th centuries BC. Further evidence from excavations in the Stele Park at the heart of Aksum corroborates continuous activity in the area from the outset of the common era. Two hills and two streams lie on the east and west expanses of the city of Aksum; perhaps providing the initial impetus for settling this area.<ref name="users.clas.ufl.edu"> ufl.edu {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180329065343/http://users.clas.ufl.edu/sterk/junsem/haas.pdf |date=2018-03-29 }}</ref><ref name="whc.unesco.org">{{Cite web|url=http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/15|title = Aksum}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Uhlig |first1=Siegbert |title=Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C |pages=173}}</ref> | |||

| According to the Periplus, the ruler of Aksum in the 1st century AD was ], who, besides ruling in Aksum also controlled two harbours on the ]: ] (near ]) and Avalites (]). He is also said to have been familiar with Greek literature: | |||

| Archeological evidence suggests that the Aksumite polity arose between 150 BC and 150 AD. Small scale district "kingdoms" denoted by very large nucleated communities with one or more elite residences appears to have existed in the early period of the kingdom of Aksum, and here ] concludes that; "Quite probably, the kingdom was a confederacy, one which was led by a district-level king who commanded the allegiance of other petty kings within the Axumite realm. The ruler of the Axumite kingdom was thus 'King-of-Kings' — a title often found in inscriptions of this period. There is no evidence that a single royal lineage has yet emerged, and it is quite possible that at the death of a King-of-Kings, a new one would be selected from among all the kings in the confederacy, rather than through some principle of primogeniture."<ref>{{cite book |last1=Uhlig |first1=Siegbert |title=Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C |pages=181}}</ref><ref>S. C. Munro-Hay (1991) ''Aksum: An African Civilization of Late Antiquity''. Edinburgh: University Press. p. 40. {{ISBN|0748601066}}</ref> | |||

| {{quote|"These places, from the Calf-Eaters to the other Berber country, are governed by Zoscales; who is miserly in his ways and always striving for more, but otherwise upright, and acquainted with Greek literature."|Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, Chap.5<ref></ref>}} | |||

| ===Rise of Aksum=== | |||

| The Kingdom of Aksum benefited from a major transformation of the maritime trading system that linked ]. This change took place around the start of the ]. The older trading system involved coastal sailing and many intermediary ports. The Red Sea was of secondary importance to the ] and overland connections to the ]. Starting around 100 BC a route from Egypt to India was established, making use of the Red Sea and using monsoon winds to cross the ] directly to ]. By about 100 AD the volume of traffic being shipped on this route had eclipsed older routes. Roman demand for goods from southern India increased dramatically, resulting in greater number of large ships sailing down the Red Sea from Roman Egypt to the Arabian Sea and India. | |||

| The first historical mention of Axum comes from the '']'', a trading guide which likely dates to the mid-1st century AD. Axum is mentioned alongside ] and ] as lying within the realm of ]. The area is described as a primarily producing ivory, as well as tortoise shells. King Zoskales had a Greek education, indicating that Greco-Roman influence was already present at this time.<ref name="sourcebooks.fordham.edu">{{cite web |title=The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean by a Merchant of the First Century | url=https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/ancient/periplus.asp | website=Fordham University Internet History Sourcebooks, chapters 4 and 5}}</ref> It is evident from the Periplus that, even at this early stage of its history, Axum played a role in the transcontinental ].<ref>{{cite book |last= Phillips|first= Jacke|date= 2016|chapter= Aksum, Kingdom of|editor-last= MacKenzie|editor-first= John M.|title= The Encyclopedia of Empire|location= Hoboken|publisher= John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.|pages= 1–2|isbn= 9781118455074}}</ref> | |||

| The Aksumite control over ] enabled the exchange of Ethiopian products for foreign imports. Both ] and the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea make reference to this port, situated three days away from the initial ivory market at ], itself five days distant from Aksum. This trade across the Red Sea, spanning from the Roman Empire in the north to India and Ceylon in the east, played a crucial role in Aksum's prosperity. The city thrived by exporting goods such as ivory, tortoiseshell, and rhinoceros horn. Pliny also mentioned additional items like hippopotamus hide, monkeys, and slaves. During the 2nd century AD, ]'s geographer referred to Aksum as a powerful kingdom. Both archaeological findings and textual evidence suggest that during this period, a centralized regional polity had emerged in the Aksumite area, characterized by defined social stratification. By the beginning of the 4th century AD, the Aksumite state had become well-established, featuring urban centers, an official currency with coinage struck in gold, silver, and copper, an intensive agricultural system, and a organized military.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Uhlig |first1=Siegbert |title=Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C |pages=174}}</ref> | |||

| The Kingdom of Aksum was ideally located to take advantage of the new trading situation. ] soon became the main port for the export of African goods, such as ivory, incense, gold, and exotic animals. In order to supply such goods the kings of Aksum worked to develop and expand an inland trading network. A rival, and much older trading network that tapped the same interior region of Africa was that of the Kingdom of ], which had long supplied Egypt with African goods via the ] corridor. By the 1st century AD, however, Aksum had gained control over territory previously Kushite. The ''Periplus of the Erythraean Sea'' explicitly describes how ivory collected in Kushite territory was being exported through the port of Adulis instead of being taken to ], the capital of Kush. During the 2nd and 3rd centuries the Kingdom of Aksum continued to expand their control of the southern Red Sea basin. A caravan route to Egypt was established which bypassed the Nile corridor entirely. Aksum succeeded in becoming the principal supplier of African goods to the Roman Empire, not least as a result of the transformed Indian Ocean trading system.<ref>The effect of the Indian Ocean trading system on the rise of Aksum is described in , by Stanley M. Burstein.</ref> | |||

| In the 3rd century, Aksum began interfering in South Arabian affairs, controlling at times the western ] region among other areas. By the late 3rd century it had begun minting ] and was named by ] as one of the four great powers of his time along with ], ], and ]. It converted to ] in ] or ] under ] and was the first state ever to use the image of the cross on ]. At its height, Aksum controlled northern ], ], northern ], southern ], ], ], and southern ], totalling 1.25 million km².<ref>* ''''. Peter Turchin, Jonathan M. Adams, and Thomas D. Hall. ]. November 2004.</ref> | |||

| Around 200 AD, Aksumite ambitions had expanded to Southern Arabia, where Aksum appears to have established itself in ] and engaged in conflicts with Saba and Himyar at various points, forming different alliances with chief kingdoms and tribes. During the early part of the 3rd century, the kings ] and ] dispatched military expeditions to the region. Inscriptions from local Arabian dynasties refer to these rulers with the title "nagasi of Aksum and Habashat," and a metal object discovered in eastern Tigray also mentions a certain "GDR ''negus'' of Aksum." Later in the century the ''mlky hhst dtwns wzqrns'' (kings of Habashat ] and ZQRNS) are also mentioned ]. According to a Greek inscription in Eritrea known as the '']'' recorded by ], in around the mid to late 3rd century (possibly c. 240–c. 260), the Aksumites led by an anonymous king achieved significant territorial expansion in the ] and the ], with their influence extending as far as ] and the borders of Egypt.<ref>George Hatke, ''Aksum and Nubia: Warfare, Commerce, and Political Fictions in Ancient Northeast Africa'' (New York University Press, 2013), pp. 44. {{ISBN|0-7486-0106-6}}</ref><ref name="dx.doi.org2">{{Cite journal|date=August 1910|title=The Christian Topography of Cosmas Indicopleustes|journal=Nature|volume=84|issue=2127|pages=133–134|doi=10.1038/084133a0|issn=0028-0836|bibcode=1910Natur..84..133.|hdl=2027/coo1.ark:/13960/t07w6zm1b|s2cid=3942233|url=https://archive.org/details/christiantopogra00cosmuoft|hdl-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Uhlig |first1=Siegbert |title=Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C |pages=175}}</ref> | |||

| It was a quasi-ally of ] against the ] of the day and declined after the ] due to unknown reasons, but informed speculation suggests the rise of ] heavily impacted its ability to trade with the ] in the era when shipping was limited to coastal navigation as well as cut it off from its principal markets in ], ] and ]. | |||

| By the end of the 3rd century AD, Aksum had gained recognition by the prophet ] in the '']'', as one of the four great powers of the world alongside Rome, Persia, and China. As the political influence of Aksum expanded, so did the grandeur of its monuments. Excavations by archaeological expeditions revealed early use of stelae, evolving from plain and rough markers to some of the largest monuments in Africa. The granite stelae in the main cemetery, housing Aksumite royal tombs, transformed from plain to carefully dressed granite, eventually carved to resemble multi-storey towers in a distinctive architectural style. Aksumite architecture featured massive dressed granite blocks, smaller uncut stones for walling, mud mortar, bricks for vaulting and arches, and a visible wooden framework, known as "monkey-heads" or square corner extrusions. Walls inclined inwards and incorporated several recessed bays for added strength. Aksum and other cities, such as ] and ], boasted substantial "palace" buildings employing this architectural style. In the early 6th century, ] described his visit to Aksum, mentioning the four-towered palace of the Aksumite king, adorned with bronze statues of unicorns. Aksum also featured rows of monumental granite thrones, likely bearing metal statues dedicated to pre-Christian deities. These thrones incorporated large panels at the sides and back with inscriptions, attributed to ], ], ], and his son ], serving as victory monuments documenting the wars of these kings.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Uhlig |first1=Siegbert |title=Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C |pages=176}}</ref> | |||

| After a second ] in the early 6th century, the empire began to decline, eventually ceasing its production of coins in the early 7th century. It finally dissolved with the invasion of the ] or ]ish queen ] in the 9th or 10th century, resulting in a Dark Age about which little is known until the rise of the ]. | |||

| King ] became the first Christian ruler of Aksum in the 4th century. Ezana's coins and inscriptions make the change from pre-Christian imagery to Christian symbolism around 340 AD. The conversion to Christianity was one of the most revolutionary events in the history of Ethiopia as it gave Aksum a cultural link with the ]. Aksum gained a political link with the ], which regarded itself as the protector of ]. Three inscriptions on the ] documents the conversion of King Ezana to Christianity and two of his military expeditions against neighboring areas, one inscribed in Greek and the other in Geez. The two expeditions refers to two distinct campaigns, one against the "]", and the other against the ]. According to the inscription, the Noba were settled somewhere around the Nile and Atbara confluence, where they seemed to have taken over much of the ]. Yet they did not drive the Kushites away from their heartland, since the inscription states that the Aksumites fought them at the junction of the two rivers. Also mentioned in the inscription are the mysterious "red Noba" against whom an expedition was carried out. This people seems to be settled further north and may be identical with the "other Nobades" mentioned in the inscription of the Nubian king ] carved on the wall of the ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Uhlig |first1=Siegbert |title=Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C |pages=177}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Uhlig |first1=Siegbert |title=Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: He-N |pages= 1193}}</ref> | |||

| ==Origins== | |||

| Aksum was previously thought to have been founded by ]-speaking ]s who crossed the ] from South Arabia (modern ]) on the basis of Conti Rossini's theories and prolific work on Ethiopian history, but most scholars now agree that it was an indigenous development.<ref>Stuart Munro-Hay, ''Aksum: An African Civilization of Late Antiquity''. Edinburgh: University Press, 1991, pp.57.</ref><ref>Pankhurst, Richard K.P. ''Addis Tribune'', "", January 17, 2003.</ref> Scholars like Stuart Munro-Hay point to the existence of an older ] or Da'amot kingdom, prior to any Sabaean migration ca. 4th or 5th c. BC, as well as to evidence of Sabaean immigrants having resided in the region for little more than a few decades.<ref>Munro-Hay, ''Aksum'', pp. 57.</ref> Furthermore, ], the ancient Semitic language of Eritrea and Ethiopia, is now known to not have derived from ], and there is evidence of a Semitic speaking presence in Ethiopia and Eritrea at least as early as ].<ref>''ibid''.</ref><ref>Herausgegeben von Uhlig, Siegbert. ''Encyclopaedia Aethiopica'', "Ge'ez". Wiesbaden:Harrassowitz Verlag, 2005, pp. 732.</ref> Sabaean influence is now thought to have been minor, limited to a few localities, and disappearing after a few decades or a century, perhaps representing a trading or military colony in some sort of symbiosis or military alliance with the civilization of ] or some proto-Aksumite state.<ref>Munro-Hay, ''Aksum'', pp.57.</ref> Adding more to the confusion, there existed an Ethiopian city called ] in the ancient period that does not seem to have been a Sabaean settlement. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ==The Empire== | |||

| The Empire of Aksum at its height extended across portions of present-day ], northern ], ], southern ] northern ], and northern ]. The capital city of the empire was ], now in northern Ethiopia. Today a country village, the city of Aksum was once a bustling metropolis, a bustling cultural and economic center. Two hills and two streams lie on the east and west expanses of the city; perhaps providing the initial impetus for settling this area. Along the hills and plain outside the city, the Aksumites had cemeteries with elaborate grave stones called Steale, or obelisks. Other important cities included ], ], ], ], and ], the last three of which are now in Eritrea. | |||

| ] sent an expedition against the Jewish ] King ], who was persecuting the Christian community in Yemen. Kaleb gained widespread acclaim in his era as the conqueror of Yemen. He expanded his royal title to include king of Hadramawt in southeastern Yemen, as well as the coastal plain and highland of Yemen, along with "all their Arabs", highlighting the extensive influence of Aksum across the Red Sea into Arabia. ] was deposed and killed and Kaleb appointed an Arab viceroy named ] ("Sumuafa Ashawa"), but his rule was short-lived as he was ousted in a coup led by an Aksumite named ] after five years. Kaleb sent two expeditions against Abraha, but both were decisively defeated. According to ], following Aksum's unsuccessful attempts to remove him, ] continued to govern Yemen through a tribute arrangement with the king of Aksum.<ref>{{Cite book|title=History of the Later Roman Empire|last=Bury|first=J. B.|publisher=Macmillan & Co.|year=1923|pages=325–326|volume=II}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Uhlig |first1=Siegbert |title=Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C |pages=178}}</ref> | |||

| ==Societal structure== | |||

| Proto-] and Proto-] are believed to be the main ethnicity of the empire of Axum in the first millennium AD. Their language, in form of ], remained the language of later Ethiopian imperial court as well as the ] and ]. | |||

| After ]'s death, his son Masruq Abraha continued the Aksumite vice-royalty in Yemen, resuming payment of tribute to Aksum. However, his half-brother Ma'd-Karib revolted. Ma'd-Karib first sought help from the Roman Emperor ], but having been denied, he decided to ally with the ] ], triggering the ]. Khosrow I sent a small fleet and army under commander ] to depose the king of Yemen. The war culminated with the ], capital of Aksumite Yemen. After its fall in 570, and Masruq's death, Ma'd-Karib's son, Saif, was put on the throne. In 575, the war resumed again, after Saif was killed by Aksumites. The Persian general ] led another army of 8000, ending Axum rule in Yemen and becoming hereditary governor of Yemen. According to ], these wars may have been Aksum's swan-song as a great power, with an overall weakening of Aksumite authority and over-expenditure in money and manpower.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Uhlig |first1=Siegbert |title=Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C |pages=178}}</ref> | |||

| The Aksumite people represented a mix of a ]-speaking people, ]-speaking people, and ]-speaking people (the ] and ]) collectively known as ]. | |||

| ===Decline=== | |||

| The Aksumite kings had the official title ነገሠ ፡ ነገሠተ ''ngś ngśt'' - King of Kings (later vocalization ] ንጉሠ ፡ ነገሥት ''nigūśa nagaśt'', ] ''nigūse negest''). Aksumite kings traced their lineage to ] and the ]. This royal heritage and title was claimed and used by all ]. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Aksumite trade in the Red Sea likely suffered due to the Persian conquests in Egypt and Syria, followed by the defeats in Yemen. However, a more enduring impact occurred with the rise of ] in the early 7th century and the expansion of the ]. Axum initially had good relations with its Islamic neighbours. In 615 AD for example, early ]s from ] fleeing ]i persecution traveled to Axum and were given refuge; this journey is known in ] as the ]. In 630, ] sent a naval expedition against suspected Abyssinian pirates, the ].<ref>E. Cerulli, "Ethiopia's Relations with the Muslim World" in ''Cambridge History of Africa: Africa from the Seventh to the Eleventh century'', p. 575.</ref><ref>Trimingham, Spencer, ''Islam in Ethiopia'', p. 46.</ref> Trade with the Roman/Byzantine world came to a halt as the Arabs seized the eastern Roman provinces. Consequently, Aksum experienced a decline in prosperity due to increased isolation and eventually ceased production of coins in the early 8th century.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Uhlig |first1=Siegbert |title=Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C |pages=178}}</ref> | |||

| The Islamic conquests were not solely responsible for the decline of Aksum. Another reason for the decline was the expansions of the ] nomads. Due to the poverty of their country, many of them began to migrate into the northern Ethiopian plateau. At the end of the 7th century AD, a strong Beja tribe known as the ] entered the ]n plateau through the valley of ]. They overran and pillaged much of the ]n highlands as Aksum could no longer maintain its sovereignty over the frontier. As a result, the connection to the ] ports was lost.<ref>Trimingham, Spencer, ''Islam in Ethiopia'', p. 49.</ref> | |||

| Aksumites did own slaves, and a modified feudal system was in place to farm the land. | |||

| Around this same time, the Aksumite population was forced to go farther inland to the ] for protection, abandoning Aksum as the capital. Arab writers of the time continued to describe Ethiopia (no longer referred to as Aksum) as an extensive and powerful state, though they had lost control of most of the coast and their tributaries.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Uhlig |first1=Siegbert |title=Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C |pages=178}}</ref> While land was lost in the north, it was gained in the south; and, though Ethiopia was no longer an economic power, it still attracted Arab merchants. The capital was then moved south to a new location called ].<ref name="Munro-Hay57" /> The Arab writer ] was the first to describe the new Aksumite capital. The capital was probably located in southern ] or ]; however, the exact location of this city is currently unknown.<ref>Taddesse Tamrat, ''Church and State in Ethiopia'' (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972), p. 36.</ref> ] is noted in Ethiopia in the ninth century. The Coptic patriarchs ] (819–830) and ] (830–849) of Alexandria attribute Ethiopia's condition to war, plague, and inadequate rains.<ref>Evetts, B.: "History of the Patriarchs of the Coptic Church of Alexandria", by Sawirus ibn al-Mukaffa', bishop of al-Ashmunien, Vol I, IV, Menas I to Joseph, PO X fasc. 5. pp 375-551, Paris, 1904</ref> Under the reign of ], during the 9th century, the empire kept expanding south, undertaking missionary activities south of ].<ref>Werner J. Lange, "History of the Southern Gonga (southwestern Ethiopia)", Steiner, 1982, p. 18</ref> | |||

| ==Foreign relations and economy== | |||

| ====Gudit's invasion==== | |||

| Axum traded with ] and ] (later ]), exporting ], ], ] and ]s, and importing ] and ]. Axum's access to both the Red Sea and the Upper Nile enabled its strong navy to profit in trade between various African (]), Arabian (]), and Indian states. | |||

| {{main|Gudit}} | |||

| In the ] AD, Axum acquired tributary states on the Arabian Peninsula across the Red Sea, and by 350, they conquered the ]. | |||

| ] (also known as Queen of Sheba's Palace) in Aksum, Tigray Region, Ethiopia]] | |||

| ], 330–360 AD. ]] | |||

| Local history holds that, around 960, a Jewish Queen named Yodit (Judith) or "]" defeated the empire and burned its churches and literature. While there is evidence of churches being burned and an invasion around this time, her existence has been questioned by some western authors. ] sacked Aksum by destroying churches and buildings, persecuted Christians and committed Christian ]. Her origin has been debated among scholars. Some argued that she had a ] ethnicity or was from a southern region. According to one traditional account, she reigned for forty years and her ] lasted until 1137 AD, when it was overthrown by ], resulting in the inception of the ]-led ].<ref name=":0">{{Cite book |last=Henze |first=Paul B. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gzwoedwOkQMC&pg=PA49 |title=Layers of Time: A History of Ethiopia |date=2000 |publisher=Hurst & Company |isbn=978-1-85065-393-6 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| According to an oral tradition, Gudit rose to power after she killed the ] king and then reigned for 40 years. She brought her Jewish army from ] and ] to orchestrate the pillage against Aksum and its countryside. She was determined to destroy all members of the Aksumite dynasty, palaces, churches and monuments in ]. Her notorious deeds are still recounted by peasants inhabiting northern Ethiopia. Large ruins, standing stones and stelae are found in the area.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Childress |first=David Hatcher |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=N4pXDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT207 |title=Ark of God: The Incredible Power of the Ark of the Covenant |date=2015-10-27 |publisher=SCB Distributors |isbn=978-1-939149-60-2 |language=en}}</ref> Gudit also killed the last emperor of Aksum, possibly ], while other accounts say Dil Na'od went into exile in ], protected by Christians. He begged assistance from a ] ruler, King ], but remained unanswered.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Jewel |first=Lady |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Vx_N_bEKNj8C&pg=PA246 |title=Keeper of the Ark (a Moses Trilogy): For the Love of Moses, for the Children of Moses, for the Children of God |date=August 2012 |publisher=WestBow Press |isbn=978-1-4497-5061-9 |language=en}}</ref> She was said to have been succeeded by Dagna-Jan, whose throne name was Anbasa Wudem.<ref name=":0" /> Her reign was marked by the displacement of the Aksumite population into the south. According to one Ethiopian traditional account, she reigned for forty years and her dynasty was eventually overthrown by ] in 1137 AD, who ushered in the formation of the ] by bearing children with a descendant of the last Aksumite emperor, Dil Na'od.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Mekonnen |first=Yohannes K. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Q0pZPp032c0C&pg=PA288 |title=Ethiopia: The Land, Its People, History and Culture |date=April 2013 |publisher=New Africa Press |isbn=978-9987-16-024-2 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| The main exports of Axum were, as would be expected of a state during this time, agricultural products. The land was much more fertile during the time of the Aksumites than now, and their principle crops were grains such as wheat and barley. The people of Aksum also raised cattle, sheep, and camels. Wild animals were also hunted for things such as ivory and rhinoceros horns. They traded with Roman traders as well as with Egyptian and Persian merchants. | |||

| After a short Dark Age, the Aksumite Empire was succeeded by the ] in the 11th or 12th century (most likely around 1137), although limited in size and scope. However, ], who killed the last Zagwe king and founded the modern ] around 1270 traced his ancestry and his right to rule from the last emperor of Aksum, ]. It should be mentioned that the end of the Aksumite Empire didn't mean the end of Aksumite culture and traditions; for example, the architecture of the Zagwe dynasty at ] and ] shows heavy Aksumite influence.<ref name="Munro-Hay57" /> | |||

| The empire was also rich with gold and iron deposits. These metals were valuable to trade, but another mineral was also widely traded. Salt was found richly in Aksum and was traded quite frequently. | |||

| ==Society== | |||

| Axum remained a strong empire and trading power until the rise of ] in the ]. However, because the Axumites had sheltered ]'s first followers, the Muslims never attempted to overthrow Axum as they spread across the face of Africa. Nevertheless, as early as 640, ] sent a naval expedition against ] under ], but it was eventually defeated.<ref>E. Cerulli, "Ethiopia's Relations with the Muslim World," in ''Cambridge History of Africa, Africa from the Seventh to the Eleventh century'', pp.575; Trimingham, Spencer, ''Islam in Ethiopia'', pp.46.</ref> Axumite naval power also declined throughout the period, though in 702 Aksumite pirates were able to invade the ] and occupy ]. In retaliation, however, ] was able to take the ] from Axum, which became Muslim from that point on, though later recovered in the 9th century and vassal to the ].<ref>Daniel Kendie, ''The Five Dimensions of the Eritrean Conflict 1941 – 2004: Deciphering the Geo-Political Puzzle. United States of America: Signature Book Printing, Inc., 2005, pp.228.</ref> | |||

| The Aksumite population mainly consisted of ]-speaking groups, one of these groups were the ]an or the speakers of ], the commenter of the ] inscription identifies them as the main inhabitants of ] and its surroundings. The ]-speaking ] were also known to have lived within the kingdom, as ] notes that a "governor of Agau", was entrusted by King ] with the protection of the vital long-distance caravan routes from the south, suggesting that they lived within the southern frontier of the Aksumite kingdom.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Hable Selassie |first1=Sergew |title=Ancient and Medieval Ethiopian History to 1270 |pages=27 }}</ref><ref>Taddesse Tamrat, ''Church and State in Ethiopia'' (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972), p. 50.</ref> Aksum also had a sizeable ] population, which resided in the cities of ] and ].<ref>Crawford Young, ''The Rising Tide of Cultural Pluralism: The Nation-state at Bay?'', (University of Wisconsin Press: 1993), p. 160</ref> ] groups also inhabited Aksum, as inscriptions from the time of ] note the "Barya", an animist tribe who lived in the western part of the empire, believed to be the ]s.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Pankhrust |first1=Richard |title=The Ethiopian Borderlands |year=1997 |page=33 |publisher=The Red Sea Press |isbn=9780932415196 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zpYBD3bzW1wC&q=ethiopian+borderlands}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Hatke |first1=George |title=Aksum and Nubia |date=7 January 2013 |publisher=NYU Press |isbn=9780814762837 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Oy7N_d6HoYIC&dq=Aksumite+baryas&pg=PA165}}</ref> | |||

| Aksumite settlements were distributed across a significant portion of the highlands in the northern Horn of Africa, with the majority located in northeastern ], Ethiopia, as well as the ] and ] regions of Eritrea. Despite the concentration in these areas, some Aksumite settlements such as ] are located as far as ]. In addition to the highlands, sites from the Aksumite period were discovered along the Red Sea coast of Eritrea, near the ]. Numerous Aksumite settlements were strategically positioned along an axis that traversed from Aksum to the ], forming a route connecting the Aksumite capital in the highlands to the principal Aksumite port of ] on the Red Sea. Along this route, two of the largest Aksumite-era settlements, ] and ], were situated in the Eritrean highlands. The concertation of these Aksumite ancient settlements suggests high population density in the highlands of Tigray and central Eritrea.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Uhlig |first1=Siegbert |title=Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C |pages=187}}</ref> According to ], the integral regions of the Aksumite Kingdom included "much of the province of ], the whole of the Eritrean plateau" and the regions of ], ] and ].<ref>Taddesse Tamrat, ''Church and State in Ethiopia'' (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972), p. 50.</ref> | |||

| A complex agricultural system in the Aksumite area, which involved irrigation, dam construction, terracing, and plough-farming, played a crucial role in sustaining both urban and rural populations. Aksumite farmers cultivated a variety of cereal crops with origins from both Africa and the Near East. These crops included ], ], ], emmer wheat, bread wheat, hulled barley, and oats. In addition to cereal crops, Aksumite farmers also grew linseed, cotton, grapes, and legumes of Near Eastern origin such as lentils, fava beans, chickpeas, common peas, and grass peas. Other important crops included the African oil crop, ], as well as gourds and cress. This diverse range of crops, combined with the herding of domesticated cattle, sheep, and goats, contributed to the creation of a highly productive indigenous agropastoral food-producing tradition. This tradition played an integral role in the development of the Aksumite economy and the consolidation of state power.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Uhlig |first1=Siegbert |title=Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C |pages=187}}</ref> | |||

| Eventually, the Islamic Empire took control of the Red Sea and most of the Nile, forcing Axum into economic isolation. However, it still had relatively good relations with all of its Muslim neighbors. Two Christian states northwest of Axum (in modern day Sudan), ] and ], survived until the ] when they were finally forced by Muslim conversion to become Islamic. Axum, however, remained untouched by the Islamic movements across Africa. | |||

| == |

==Culture== | ||

| ] in the ]]] | |||

| Before its conversion to Christianity the Aksumites practiced a polytheistic religion not unlike the Greek’s system. Astar was the main god of the pre-Christian Aksumites, and his son, Mahrem, was who the kings of Aksum traced their lineage. In about 324 AD the King Ezana II was converted by his slave-teacher Frumentius, the founder of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. Frumentius taught the emperor while he was young, and at some point staged the conversion of the empire. We know that the Axumites converted to Christianity because in their coins they replaced the disc and crescent with the cross. | |||

| ] of ]]] | |||

| Frumentius was in contact with the Church in Alexandria and was appointed Bishop of Ethiopia around 330 AD Alexandria never reigned Aksum in tightly, rather allowing its own form of Christianity form, however, the church did retain a minor influence. | |||

| The Empire of Aksum is notable for a number of achievements, such as its own alphabet, the ], which was eventually modified to include ]s, becoming an ]. Furthermore, in the early times of the empire, around 1700 years ago, giant obelisks to mark emperors' (and nobles') tombs (underground grave chambers) were constructed, the most famous of which is the ]. | |||

| Aksum is also the alleged home of the holy relic the Ark of the Covenant. The Ark is said to have been placed in the Church of Mary of Zion by Menelik I for safekeeping. | |||

| Under Emperor ], Aksum adopted ] in place of its former ] and ] religions around 325. The Axumite Coptic Church gave rise to the present day ] (only granted autonomy from the Coptic Church in 1959) and ] (granted autonomy from the Ethiopian Orthodox church in 1993). Since the schism with Orthodoxy following the ] (451), it has been an important ] church, and its ] and ] continue to be in Geʽez.<ref name="britishmuseum.org">{{cite web |last1=The British Museum |last2=The CarAf Centre |title=The wealth of Africa – The kingdom of Aksum: Teachers' notes |url=https://www.britishmuseum.org/pdf/KingdomOfAksum_TeachersNotes.pdf |website=BritishMuseum.org |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191104191259/https://www.britishmuseum.org/pdf/KingdomOfAksum_TeachersNotes.pdf |archive-date=4 November 2019}}</ref><ref name="Daily Life">{{cite web |title=Daily Life in Aksum |url=https://www.eduplace.com/kids/socsci/ca/books/bkf3/writing/03_aksum.pdf |website=www.hmhco.com/ (formerly eduplace.com) |publisher=Houghton Mifflin Company. |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200803075358/https://www.eduplace.com/kids/socsci/ca/books/bkf3/writing/03_aksum.pdf |archive-date=3 August 2020 |series=Research Reports: Daily Life in Ancient Times}}</ref><ref name="georgeocox">{{cite book |title=African Empires and Civilizations : Ancient and Medieval|author=George O. Cox|publisher=Routledge|year=2015|pages=71}}</ref> | |||

| ==Cultural achievements== | |||

| The Empire of Aksum is notable for a number of achievements, such its own alphabet, the ] (which evolved from ] during the late pre-Aksumite and proto-Aksumite period), which was modified to include vowels, becoming an ]. Furthermore, in the early times of the empire, around 1700 years ago, giant Obelisks to mark emperor's (and nobles') tombstones (underground grave chambers) were constructed, the most famous of which is the ]. | |||

| ] | |||

| Under Emperor ], Axum adopted Christianity in place of its former ] and ] religions around 325. This gave rise to the present day ] (1959), and ] (1993). Since the schism with Rome following the ] (451), it has been an important ] church, and its scriptures and liturgy are still in Ge'ez. | |||

| === Language === | |||

| It was a ] and culturally important state. It was a meeting place for a variety of cultures: ]ian, ]ic, ]ic, and ]n. The major Aksumite cities had ], ]ish, ], ], and even ] minorities. | |||

| ] became the official and literary language of the Axumite state, coming from the influence of the significant ] communities established in ], the port of ], ], and other cities in the region during ] times.<ref name="abbasalamavol68">{{cite book |title=Abba Salama Volumes 6-8 |publisher=University of California |year=1975 |pages=24}}</ref><ref name="andebrhanweldegiorgis">{{cite book |author=Andebrhan Welde Giorgis |title=Eritrea at a Crossroads A Narrative of Triumph, Betrayal and Hope |publisher=Strategic Book Publishing and Rights Company |year=2014 |page=19}}</ref><ref name="McLaughlin">Raoul McLaughlin, ''The Roman Empire and the Indian Ocean'', p. 114, Barnsley, Pen & Sword Military, 2012, {{ISBN|9781-78346-381-7}}.</ref> Greek was used in the state's administration, international diplomacy, and trade; it can be widely seen in coinage and inscriptions.<ref name="garimagospels">{{cite book |author=Judith S. McKenzie |title=The Garima Gospels: Early Illuminated Gospel Books from Ethiopia |author2=Francis Watson |publisher=NYU Press |year=2016 |pages=18}}</ref><ref name="americannumismaticsociety">{{cite book |author=American Numismatic Society |title=Museum Notes, Volumes 29 to 31 |publisher=American Numismatic Society |year=1984 |pages=165}}</ref><ref name="fjnothling">{{cite book |author=F. J. Nöthling |title=Pre-colonial Africa: Her Civilisations and Foreign Contacts |publisher=Southern Book Publishers |year=1989 |pages=58}}</ref><ref name="louisieminks">{{cite book |author=Louise Minks |title=Traditional Africa |publisher=Lucent Books |year=1995 |pages=28}}</ref> | |||

| ], the language of ], was spoken alongside Greek in the court of Aksum. Although during the early kingdom, Geʿez was a spoken language, it has attestations written in the Old South Arabian language ].<ref name="unescoscientifichistoryofafrica">{{cite book |author=Unesco. International Scientific Committee for the Drafting of a General History of Africa |title=Ancient Civilizations of Africa |publisher=Heinemann Educational Books |year=1981 |pages=398}}</ref><ref name="jamescowlesprichard">{{cite book |author=James Cowles Prichard |title=Researches Into the Physical History of Mankind, Volume 1 |publisher=John and Arthur Arch, Cornhill |year=1826 |pages=284}}</ref><ref name="encylopediabritannica">{{cite book |title=The Encyclopædia Britannica: The New Volumes, Constituting, in Combination with the Twenty-nine Volumes of the Eleventh Edition, the Twelfth Edition of that Work, and Also Supplying a New, Distinctive, and Independent Library of Reference Dealing with Events and Developments of the Period 1910 to 1921 Inclusive, Volume 24 |publisher=Encyclopædia Britannica Company, Limited |year=1911 |pages=629}}</ref> In the 4th century, ] promoted the ] and made Geʽez an official state language alongside Greek; by the 6th century literary translations into Geʿez were common.<ref name="garimagospels" /><ref name="thomasolambdin">{{cite book |author=Thomas O. Lambdin |title=Introduction to Classical Ethiopic (Geʻez) |publisher=Brill |year=2018 |pages=1}}</ref><ref name="washingtonforeignareasstudiesdivision">{{cite book |author=American University (Washington, D.C.). Foreign Areas Studies Division |title=Area Handbook for Ethiopia |author2=Irving Kaplan |publisher=U.S. Government Printing Office |year=1964 |pages=34}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Munro-Hay |first=Stuart |title=Aksum: An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity |date=1991 |publisher=Edinburgh University Press |isbn=0748601066 |location=Edinburgh |page=5}}</ref> After the 7th century's Muslim conquests in the Middle East and North Africa, which effectively isolated Axum from the Greco-Roman world, Geʿez replaced Greek entirely.<ref name="muhammadjamalaldinmukhtar">{{cite book |author=Muḥammad Jamāl al-Dīn Mukhtār |title=UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. II, Abridged Edition: Ancient Africa |publisher=University of California Press |year=1990 |pages=234}}</ref><ref name="medievalethiopianorthodoxchurch" /> | |||

| ===Religion=== | |||

| ] and three ], associated with ] ({{lang|gez|ዐስተር}}), Semitic god of the ]]] | |||

| Before its conversion to Christianity, the Aksumites practiced a ] religion related to the religion practiced in southern Arabia. This included the use of the crescent-and-disc symbol used in southern Arabia and the northern horn.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Nx-qYO3zqlIC&pg=PA292|title=Foundations of an African Civilisation: Aksum and the northern Horn, 1000 BC – AD 1300|last=Phillipson|first=David|publisher=James Currey|year=2012|isbn=978-1847010414|page=91}}</ref> In the ] sponsored '']'' French archaeologist Francis Anfray, suggests that the Aksumites worshipped ], his son, ], and ].<ref>{{cite book|title=UNESCO General History of Africa: Ancient Africa v. 2|publisher=University of California Press|year=1990|isbn=978-0520066977|editor=G. Mokhtar|page=221}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] argues that with Aksumite culture came a major change in religion, with only Astar remaining of the old gods, the others being replaced by what he calls a "triad of indigenous divinities, Mahrem, Beher and Medr." He also suggests that Aksum culture was significantly influenced by Judaism, saying that "The first carriers of Judaism reached Ethiopia between the reign of ] BC and conversion to Christianity of King Ezana in the fourth century AD." He believes that although Ethiopian tradition suggests that these were present in large numbers, that "A relatively small number of texts and individuals dwelling in the cultural, economic, and political center could have had a considerable impact." and that "their influence was diffused throughout Ethiopian culture in its formative period. By the time Christianity took hold in the fourth century, many of the originally Hebraic-Jewish elements had been adopted by much of the indigenous population and were no longer viewed as foreign characteristics. Nor were they perceived as in conflict with the acceptance of Christianity."<ref>{{cite book|title=The Beta Israel (Falasha) in Ethiopia: From the Earliest Times to the Twentieth Century|last=Kaplan|first=Steve|publisher=New York University Press|year=1994|isbn=978-0814746646}}</ref> | |||

| Before converting to Christianity, King Ezana II's coins and inscriptions show that he might have worshiped the gods Astar, Beher, Meder/Medr, and Mahrem. Another of Ezana's inscriptions is clearly Christian and refers to "the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit".<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=A0XNvklcqbwC&pg=PA77|title=Encyclopedia of Africa Vol. I|last=Munro-Hay|first=Stuart|publisher=Oxford University press|year=2010|isbn=978-0195337709|editor=Henry Louis Gates Jr., Kwame Anthony Appiah|page=77}}</ref> Around 324 AD the King Ezana II was converted to Christianity by his teacher ], who established the Axumite Coptic Church, which later became the modern ].<ref name="isbn0-313-32273-2">{{cite book|last=Adejumobi|first=Saheed A.|title=The History of Ethiopia|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3Un6_LGIEyQC&pg=PA171|year=2007|publisher=Greenwood Publishing Group|isbn=978-0-313-32273-0|page=171}}</ref><ref name="goblues.org">{{Cite web|url=http://goblues.org/faculty/weekse/files/2012/08/axum-and-the-solomonic-dynasty.pdf|title = GoBlues - Asheville School| date=16 May 2023 }}</ref><ref name="obelisk bekerie">{{cite web |location=Newark, USA |url-status=dead |url=http://hornofafrica.newark.rutgers.edu/downloads/aksum.pdf |title=The Rise of the Askum Obelisk is the Rise of Ethiopian History|last1=Bekerie|first1=Ayele |access-date=2017-01-06 |publisher=Rutgers University |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170107100939/http://hornofafrica.newark.rutgers.edu/downloads/aksum.pdf |archive-date=2017-01-07 }}</ref> Frumentius taught the emperor while he was young, and it is believed that at some point staged the conversion of the empire.<ref name="ruperthopkins.com"/><ref name="otik.uk.zcu.cz"/> We know that the Aksumites converted to Christianity because in their coins they replaced the disc and crescent with the cross. | |||

| Frumentius was in contact with the ], and was appointed Bishop of Ethiopia around the year 330. The Church of Alexandria never closely managed the affairs of the churches in Aksum, allowing them to develop their own unique form of Christianity.<ref name="users.clas.ufl.edu" /><ref name="whc.unesco.org" /> However, the Church of Alexandria probably did retain some influence considering that the churches of Aksum followed the Church of Alexandria into ] by rejecting the Fourth Ecumenical ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.jmeca.org.uk/christianity-middle-east/history-christianity-middle-east-north-africa|title=A History of Christianity in the Middle East & North Africa|last=Wybrew|first=Hugh|publisher=Jerusalem & Middle East Church Association|access-date=25 February 2013|archive-date=3 February 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140203152710/http://www.jmeca.org.uk/christianity-middle-east/history-christianity-middle-east-north-africa|url-status=dead}}</ref> Aksum is also the alleged home of the holy relic the Ark of the Covenant. The Ark is said to have been placed in the ] by Menelik I for safekeeping.<ref name="britishmuseum.org" /><ref name="Daily Life" /> | |||

| Islam came in the 7th century at the reign of ], when the first followers of the Islamic prophet ] (also known as the ]) migrated from ] due to their persecution by the ], the ruling ] tribal confederation of ]. The ] appealed to the ], arguing that the early ] migrants were rebels who had invented a new religion, the likes of which neither the Meccans nor the Aksumites had heard of. The king granted them an audience, but ultimately refused to hand over the migrants. A ] consisting of 100 Muslim migrants occurred a few years later. Arabic inscriptions on the ] dated to the mid 9th century AD. confirm the existence of an early Muslim presence in Aksum.<ref>Trimingham, Spencer, ''Islam in Ethiopia'', p. 47.</ref> | |||

| ===Coinage=== | ===Coinage=== | ||

| {{Main|Aksumite currency}} | |||

| The Empire of Aksum was also the first African polity to issue its own ]s. From the reign of Endubis up to Armah (approximately ] to ]), gold, silver and bronze coins were minted. Issuing coinage in ancient times was an act of great importance in itself, for it proclaimed that the Axumite Empire considered itself equal to its neighbors. Many of the coins are used as signposts about what was happening when they were minted. An example being the addition of the cross to the coin after the conversion of the empire to Christianity. The presence of coins also simplified trade, and was at once a useful instrument of ] and a source of profit to the empire. | |||

| ], 227–235 AD. The right coin reads in Greek ΕΝΔΥΒΙC ΒΑCΙΛΕΥC, "King Endybis".]] | |||

| The Empire of Aksum was one of the first African polities to issue ]s,<ref name="ruperthopkins.com"/><ref name="otik.uk.zcu.cz"/> which bore legends in Geʽez and Greek. From the reign of Endubis up to ] (approximately 270 to 610), gold, silver and bronze coins were minted. Issuing coinage in ancient times was an act of great importance in itself, for it proclaimed that the Aksumite Empire considered itself equal to its neighbours. Many of the coins are used as signposts about what was happening when they were minted. An example being the addition of the cross to the coin after the conversion of the empire to Christianity. The presence of coins also simplified trade, and was at once a useful instrument of ] and a source of profit to the empire. | |||

| ==Ark of the Covenant== | |||

| Aksum is the apparent home of the Ark of the Covenant. The Ark is said to be housed in the Church of Mary of Zion, and is guarded heavily by the priests there. The Ark was said to have been brought to Aksum by King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba's son and placed under guard. Controversy surrounds the Church, since no one but the one guard priest is allowed in, no one can verify the Ark's existence. | |||

| ].]] | |||

| == |

===Architecture=== | ||

| {{Main|Ethiopian architecture}} | |||

| The Stelae are perhaps the most identifiable part of the Aksumite legacy. These stone towers served to mark graves or represent a magnificent building. The largest of these towering obelisks would measure 33 meters high had it not fallen. The Stelae have most of their mass out of the ground, but are stabilized by massive underground counter-weights. The stone was often engraved with a pattern or emblem denoting the king's or the noble's rank. | |||

| ====Palace architecture==== | |||

| ].]] | |||

| In general, elite Aksumite buildings such as palaces were constructed atop ] built of loose stones held together with mud-mortar, with carefully cut granite corner blocks which rebated back a few centimeters at regular intervals as the wall got higher, so the walls narrowed as they rose higher. These podia are often all that survive of Aksumite ruins. Above the podia, walls were generally built with alternating layers of loose stone (often whitewashed, like at ]) and horizontal wooden beams, with smaller round wooden beams set in the stonework often projecting out of the walls (these are called 'monkey heads') on the exterior and sometimes the interior. | |||

| ==Decline== | |||

| Aksum began to decline in the 7th century, and the population was forced to go farther inland to the highlands, eventually being defeated ''c.'' 950. Local history hold that a Jewish Queen named Yodit (Judith) or "]" defeated the empire and burned its churches and literature, but while there is evidence of churches being burned and an invasion around this time, her existence has been questioned by some modern authors. Another possibility is that the Axumite power was ended by a southern pagan queen named Bani al-Hamwiyah, possibly of the tribe al-Damutah or Damoti (]). After this period, the Axumite Empire was succeeded by the ] in the ] or ], although limited in size and scope. However, ], who killed the last Zagwe king and founded the modern ] traced his ancestry and his right to rule from the last emperor of Axum, ]. | |||

| Both the podia and the walls above exhibited no long straight stretches but were indented at regular intervals so that any long walls consisted of a series of recesses and salients. This helped to strengthen the walls. Worked granite was used for architectural features including columns, bases, capitals, doors, windows, paving, water spouts (often shaped like lion heads) and so on, as well as enormous flights of stairs that often flanked the walls of palace pavilions on several sides. Doors and windows were usually framed by stone or wooden cross-members, linked at the corners by square 'monkey heads', though simple lintels were also used. Many of these Aksumite features are seen carved into the famous stelae as well as in the later ] of ] and ].<ref name="Munro-Hay57" /> | |||

| Other reasons for the decline are less romantic and more scientific. Climate change and trade isolation are probably also large reasons for the decline of the culture. Over farming on the land lead to decreased crop yield, which in turn lead to decreased food supply. This in turn with the changing flood pattern of the Nile and several seasons of drought would alter all of Aksum’s agricultural Aksum’s geographic location would make it less important in the emerging European economy. | |||

| ]s usually consisted of a central ] surrounded by subsidiary structures pierced by doors and gates that provided some privacy (see ] for an example). The largest of these structures now known is the Ta'akha Maryam, which measured 120 × 80m, though as its pavilion was smaller than others discovered it is likely that others were even larger.<ref name="Munro-Hay57"/> | |||

| ==Aksumite Empire in Fiction== | |||

| The Aksumite Empire is portrayed as the main ally of ] in the ] by ] and ] published by ]. | |||

| Some clay models of houses survive to give us an idea of what smaller dwellings were like. One depicts a round hut with a conical roof thatched in layers, while another depicts a rectangular house with rectangular doors and windows, a roof supported by beams that end in 'monkey heads', and a parapet and water spout on the roof. Both were found in ]. Another depicts a square house with what appear to be layers of pitched thatch forming the roof.<ref name="Munro-Hay57" /> | |||

| ==Bibliography== | |||

| *Stuart Munro-Hay. ''Aksum: A Civilization of Late Antiquity.'' Edinburgh: University Press. 1991. ISBN 0-7486-0106-6 | |||

| *Yuri M. Kobishchanov. ''Axum'' (Joseph W. Michels, editor; Lorraine T. Kapitanoff, translator). University Park, Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press, 1979. ISBN 0-271-00531-9 | |||

| *Karl W. Butzer. Rise and Fall of Axum, Ethiopia: A Geo-Archaeological Interpretation. American Antiquity, Vol. 46, No. 3. (Jul., 1981), pp. 471-495. | |||

| *Boardman, Sheila. THE AGRICULTURAL FOUNDATION OF THE AKSUMITE EMPIRE, ETHIOPIA An Interim Report. The Exploitation of Plant Resources in Ancient Africa: Springer, 1999. | |||

| *Williams, Stephen. Ethiopia Afrifca's Holy Land. New African, Vol. 458. ( Jan., 2007), pp 94-97. | |||

| == |

====Stelae==== | ||

| ], an Aksumite ] in ], Ethiopia]] | |||

| <div class="references-small"> | |||

| The stelae are perhaps the most identifiable part of the Aksumite architectural legacy. These stone towers served to mark graves and represent a magnificent multi-storied palace. They are decorated with false doors and windows in typical Aksumite design. The largest of these would measure 33 meters high had it not fractured. The stelae have most of their mass out of the ground, but are stabilized by massive underground counter-weights. The stone was often engraved with a pattern or emblem denoting the king's or the noble's rank.<ref name="users.clas.ufl.edu"/><ref name="whc.unesco.org"/> | |||

| <references/></div> | |||

| For important monuments built in the region, a particular type of granite is used called ''nepheline syenite''. It is fine grained and has also been used in historic monuments like the stelae. These monuments are used to celebrate key figures in Axum history, especially kings or priests. These stelae are also called obelisks, they are located in the Mai Hejja stelae field, where complex sedimentology of the land can be observed. The foundations for the monuments are around 8.5 m below the surface of the Mai Hejja stelae field. Sediments in this area have undergone a lot of weathering over the years, so the surface of this area has undergone a lot of changes. This is part of the reason for the complex stratigraphic history in this site, some previous layers under the surface of the site.<ref name="Butzer 471–495">{{Cite journal |last=Butzer |first=Karl W. |date=July 1981 |title=Rise and Fall of Axum, Ethiopia: A Geo-Archaeological Interpretation |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/american-antiquity/article/abs/rise-and-fall-of-axum-ethiopia-a-geoarchaeological-interpretation/B5B3D127F93D1C975C3D3C0CCD3BF773 |journal=American Antiquity |language=en |volume=46 |issue=3 |pages=471–495 |doi=10.2307/280596 |jstor=280596 |s2cid=162374800 |issn=0002-7316}}</ref> | |||

| ===Foreign relations, trade, and economy=== | |||

| ]) until circa the later part of the 1st millennium when it succumbed to a long decline against pressures from the various Islamic ] leagued against it.]] | |||

| Covering parts of what is now northern ] and southern and eastern ], Aksum was deeply involved in the trade network between the ] and the ] (], later ]), exporting ], tortoise shell, gold and ]s, and importing ] and spices.<ref name="britishmuseum.org"/><ref name="Daily Life"/> Aksum's access to both the Red Sea and the Upper Nile enabled its strong navy to profit in trade between various African (]), Arabian (]), and Indian states. | |||

| The main exports of Aksum were, as would be expected of a state during this time, agricultural products. The land was much more fertile during the time of the Aksumites than now, and their principal crops were grains such as wheat, ] and ]. The people of Aksum also raised ], sheep, and camels. Wild animals were also hunted for things such as ivory and rhinoceros horns. They traded with Roman traders as well as with Egyptian and Persian merchants. The empire was also rich with gold and iron deposits. These metals were valuable to trade, but another mineral was also widely traded: ]. Salt was abundant in Aksum and was traded quite frequently.<ref name="goblues.org" /><ref name="obelisk bekerie"/> | |||

| It benefited from a major transformation of the maritime trading system that linked ]. This change took place around the start of the 1st century. The older trading system involved coastal sailing and many intermediary ports. The Red Sea was of secondary importance to the ] and overland connections to the ]. Starting around 1st century, a route from Egypt to India was established, making use of the Red Sea and using monsoon winds to cross the ] directly to ]. By about 100 AD, the volume of traffic being shipped on this route had eclipsed older routes. Roman demand for goods from southern India increased dramatically, resulting in greater number of large ships sailing down the Red Sea from ] to the Arabian Sea and India.<ref name="ruperthopkins.com"> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200925100701/http://www.ruperthopkins.com/pdf/Kingdom_of_Axum.pdf |date=2020-09-25 }}</ref><ref name="otik.uk.zcu.cz">{{Cite web |last1=Záhoří |first1=Jan |date=February 2014 |title=Review: Phillipson, (2012). ''Foundations of an African civilization: Aksum & the Northern Horn, 1000 BC - AD 1300'' |url=https://otik.uk.zcu.cz/bitstream/handle/11025/15553/Zahorik.pdf?sequence=1 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170107100243/https://otik.uk.zcu.cz/bitstream/handle/11025/15553/Zahorik.pdf?sequence=1 |archive-date=2017-01-07 |access-date=2017-01-06}}</ref> | |||

| Although excavations have been limited, fourteen Roman coins dating to the 2nd and 3rd centuries have been discovered at Aksumite sites like Matara. This suggests that trade with the Roman Empire existed at least since this period. <ref>{{Cite book |last=Sergew Hable |first=Sellassie |title=Ancient and medieval Ethiopian history to 1270 |publisher=Addis Ababa |year=1972 |pages=79}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| In 525 AD, the Aksumites attempted to take over the Yemen region to gain control over The Straits of Bab-el-Mandeb; one of the most significant trading routes in the medieval world, connecting the Red Sea to the Indian Ocean. Rulers were inclined to establish a spot of imperialism across the Red Sea in Yemen to completely control the trading vessels that ran down the Straits of Bab-el-Mandeb. It is located in the maritime choke point between Yemen and Djibouti and Eritrea. Because of the ruler of Yemen's persecution of Christians in 523 AD, Kaleb I, the ruler of Aksum (a Christian region) at the time, responded to the persecutions by attacking the Himyarite king Yūsuf As'ar Yath'ar, known as Dhu Nuwas, a Jewish convert who was persecuting the Christian community of Najran,Yemen in 525 AD, with the help of the Byzantine empire, with whom had ties with his kingdom. Victoriously, the Aksum empire was able to claim the Yemen region, establishing a viceroy in the region and troops to defend it until 570 AD when the Sassanids invaded. | |||

| The Kingdom of Aksum was ideally located to take advantage of the new trading situation. ] soon became the main port for the export of African goods, such as ivory, incense, gold, slaves, and exotic animals. In order to supply such goods the kings of Aksum worked to develop and expand an inland trading network. A rival, and much older trading network that tapped the same interior region of Africa was that of the ], which had long supplied Egypt with African goods via the ] corridor. By the 1st century AD, however, Aksum had gained control over territory previously Kushite. The ''Periplus of the Erythraean Sea'' explicitly describes how ivory collected in Kushite territory was being exported through the port of Adulis instead of being taken to ], the capital of Kush. During the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD the Kingdom of Aksum continued to expand their control of the southern Red Sea basin. A caravan route to Egypt was established which bypassed the Nile corridor entirely. Aksum succeeded in becoming the principal supplier of African goods to the Roman Empire, not least as a result of the transformed Indian Ocean trading system.<ref>The effect of the Indian Ocean trading system on the rise of Aksum is described in {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090114074953/http://www.historycooperative.org/proceedings/interactions/burstein.html |date=2009-01-14 }}, by Stanley M. Burstein.</ref> | |||

| ====Climate change hypothesis==== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ] and trade isolation have also been claimed as large reasons for the decline of the culture.{{Citation needed|date=November 2019}} The local subsistence base was substantially augmented by a climatic shift during the 1st century AD that reinforced the spring rains, extended the rainy season from 3 1/2 to six or seven months, vastly improved the surface and subsurface water supply, doubled the length of the growing season, and created an environment comparable to that of modern central Ethiopia (where two crops can be grown per annum without the aid of irrigation). | |||

| Askum was also located on a plateau {{cvt|2000|m|ft}} feet above sea level, making its soil fertile and the land good for agriculture. This appears to explain how one of the marginal agricultural environments of Ethiopia was able to support the demographic base that made this far flung commercial empire possible. It may also explain why no Aksumite rural settlement expansion into the moister, more fertile, and naturally productive lands of Begemder or Lasta can be verified during the heyday of Aksumite power. | |||

| As international profits from the exchange network declined, Aksum lost control over its raw material sources, and that network collapsed. The persistent environmental pressure on a large population needing to maintain a high level of regional food production intensified, which resulted in a wave of soil erosion that began on a local scale {{circa|650}}, and reached crisis levels after 700. Additional socioeconomic contingencies presumably compounded the problem: these are traditionally reflected in a decline in maintenance, the deterioration and partial abandonment of marginal crop lands, shifts toward more destructive exploitation of pasture land—and ultimately wholesale, irreversible ]. This decline was possibly accelerated by an apparent decline in the reliability of rainfall beginning between 730 and 760, presumably with the result that an abbreviated modern growing season was reestablished during the 9th century.<ref name="butzer1981">{{Cite journal |last=Butzer |first=Karl W. |date=1981 |title=Rise and Fall of Axum, Ethiopia: A Geo-Archaeological Interpretation |url=http://sites.utexas.edu/butzer/files/2017/03/Butzer-1981-Axum.pdf |journal=American Antiquity |volume=46 |number = 3 |pages=471–495 |via=University of Texas at Austin |jstor = 280596 |doi = 10.2307/280596|s2cid=162374800 }}</ref>{{rp|495}} | |||

| ==In literature== | |||

| {{Further|Ethiopian literature|Ethiopian historiography}} | |||

| The Aksumite Empire is portrayed as the main ally of ] in the ] by ] and ] published by ]. The series takes place during the reign of ], who in the series was assassinated by the ] in 532 at the Ta'akha Maryam and succeeded by his youngest son Eon bisi Dakuen. | |||

| In the ] series ''The Lion Hunters'', ] and his family take refuge in Aksum after the fall of ]. ] is the ruler in the first book; he passes his sovereignty onto his son Gebre Meskal, who rules during the ]. | |||

| ==Gallery== | |||

| <gallery> | |||

| File:Ethio w3.jpg|Reconstruction of Dungur | |||

| File:The North Stelae Park, Axum, Ethiopia (2812686646).jpg|The largest Aksumite stele, broken where it fell. | |||

| File:Ethio w4.jpg|Aksumite-era ] from ]. | |||

| File:Rome Stele.jpg|The ] after being returned to Ethiopia. | |||

| File:Axumite Palace (2827701317).jpg|Model of the Ta'akha Maryam palace. | |||

| File:Axumite Architectural Fragments (2823506028).jpg|Aksumite water-spouts in the shape of lion heads. | |||

| File:Axumite Jar With Figural Spout (2822617017).jpg|Aksumite jar with figural spout. | |||

| File:ET Axum asv2018-01 img41 Stelae Park.jpg|Tombs beneath the stele field. | |||

| File:Ethio w29.jpg|Entrance to the Tomb Of The False Door. | |||

| File:Stelenpark in Axum 2010.JPG|The Stelae Park in Aksum. | |||

| File:Small Steles near Aksum.jpg|Small stelae in the Gudit Stelae Field | |||