| Revision as of 15:15, 3 February 2008 editIpaat (talk | contribs)2,553 edits →La Amistad in culture: add name of Havana's street← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 16:30, 12 January 2025 edit undoMauls (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users136,102 editsNo edit summaryTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|1839 slave-ship takeover}} | |||

| {{ otheruses4|the ship|other meanings|Amistad }} | |||

| {{See also|United States v. The Amistad}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Other uses|Amistad (disambiguation)}} | |||

| '''''La Amistad''''' (]: "Friendship") was a 19th-century two-] ] of about 120 ] displacement. Built in the ], ''La Amistad'' was originally named ''Friendship'' but was renamed after being purchased by a ]. ''La Amistad'' became a symbol in the movement to ] ] after a group of ]n captives aboard revolted. Its recapture resulted in a ] over their status. | |||

| {|{{Infobox ship begin | |||

| | display title = ''La Amistad'' | |||

| | infobox caption = ''La Amistad'' | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Infobox ship image | |||

| | Ship image = File:La Amistad (ship) restored.jpg | |||

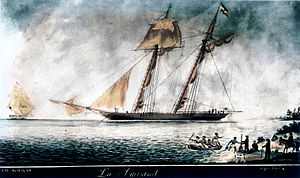

| | Ship caption = ''La Amistad'' off Culloden Point, Long Island, New York on August 26, 1839<br>(contemporary painting, artist unknown) | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Infobox ship career | |||

| | Hide header = title | |||

| | Ship country = Spain | |||

| | Ship flag = ] | |||

| | Ship name = ''La Amistad'' | |||

| | Ship owner = Ramón Ferrer | |||

| | Ship ordered = | |||

| | Ship builder = | |||

| | Ship registry = | |||

| | Ship original cost = | |||

| | Ship laid down = | |||

| | Ship launched = | |||

| | Ship acquired = Pre-June 1839 | |||

| | Ship commissioned = | |||

| | Ship decommissioned = | |||

| | Ship in service = | |||

| | Ship out of service = | |||

| | Ship renamed = | |||

| | Ship struck = | |||

| | Ship reinstated = | |||

| | Ship honours = | |||

| | Ship captured = | |||

| | Ship fate = | |||

| | Ship notes = | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Infobox ship career | |||

| | Hide header = title | |||

| | Ship country = United States | |||

| | Ship flag = {{USN flag|1840}} | |||

| | Ship name = ''Ion'' | |||

| | Ship owner = Captain George Hawford, ] | |||

| | Ship ordered = | |||

| | Ship builder = | |||

| | Ship original cost = | |||

| | Ship laid down = | |||

| | Ship launched = | |||

| | Ship acquired = October 1840 | |||

| | Ship commissioned = | |||

| | Ship decommissioned = | |||

| | Ship in service = | |||

| | Ship out of service = | |||

| | Ship renamed = | |||

| | Ship struck = | |||

| | Ship reinstated = | |||

| | Ship honours = | |||

| | Ship captured = | |||

| | Ship fate = | |||

| | Ship notes = | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Infobox ship career | |||

| | Hide header = title | |||

| | Ship country = France | |||

| | Ship flag = {{shipboxflag|France|naval}} | |||

| | Ship name = | |||

| | Ship owner = | |||

| | Ship ordered = | |||

| | Ship builder = | |||

| | Ship original cost = | |||

| | Ship laid down = | |||

| | Ship launched = | |||

| | Ship acquired = 1844 | |||

| | Ship commissioned = | |||

| | Ship decommissioned = | |||

| | Ship in service = | |||

| | Ship out of service = | |||

| | Ship renamed = | |||

| | Ship struck = | |||

| | Ship reinstated = | |||

| | Ship honours = | |||

| | Ship captured = | |||

| | Ship fate = | |||

| | Ship notes = | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Infobox ship characteristics | |||

| | Hide header = | |||

| | Header caption = | |||

| | Ship class = | |||

| | Ship tons burthen = | |||

| | Ship length = {{convert|120|ft|abbr=on}} | |||

| | Ship beam = | |||

| | Ship draught = | |||

| | Ship draft = | |||

| | Ship hold depth = | |||

| | Ship propulsion = | |||

| | Ship sail plan = ] | |||

| | Ship complement = | |||

| | Ship armament = | |||

| | Ship notes = | |||

| }} | |||

| |} | |||

| '''''La Amistad''''' ({{IPA|es|la a.misˈtað|pron}}; ] for ''Friendship'') was a 19th-century two-masted ] owned by a Spaniard living in ]. It became renowned in July 1839 for a slave revolt by ] captives who had been captured and sold to European slave traders and illegally transported by a Portuguese ship from West Africa to Cuba, in violation of European treaties against the ]. Spanish plantation owners Don José Ruiz and Don Pedro Montes bought 53 captives in ], including four children, and were transporting them on the ship to their plantations near Puerto Príncipe (modern ]).<ref> | |||

| ==The incident== | |||

| {{cite web | |||

| ] | |||

| |url=https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/amistad/ | |||

| On ] ], Africans being carried aboard ''La Amistad'' from ] were led by fellow captive ] in a revolt against their captors. Their transport from Africa to the ] was illegal<!-- Trans-Atlantic slave trafficking was illegal at the time. See ] and related articles for information on the legality of human transport-->, and they were fraudulently described as having been born in Cuba. After the revolt, the Africans demanded to be returned home, but the ship’s navigator deceived them about their course, and sailed them north along the North American coast to ], ]. The ] was subsequently taken into custody by the ]; and the Africans, who were deemed ] from the vessel, were taken to ] to be sold as slaves. There ensued a widely publicized court case about the ship and the legal status of the African captives. This incident figured prominently in ]. | |||

| |title=Teaching With Documents:The ''Amistad'' Case | |||

| |publisher=] | |||

| |access-date=March 14, 2013 | |||

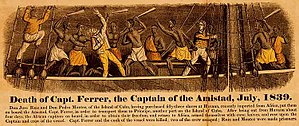

| }}</ref> The revolt began after the schooner's cook jokingly told the slaves that they were to be "killed, salted, and cooked." Sengbe Pieh (also known as ]) unshackled himself and the others on the third day and started the revolt.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Purdy|first=Elizabeth|title=Encyclopedia of African American History, 1619–1895: From the Colonial Period to the Age of Frederick Douglass|publisher=Oxford African American Studies Center|pages=Amistad}}</ref> They took control of the ship, killing the captain and the cook. Two Africans were also killed in the melee. | |||

| Pieh ordered Ruiz and Montes to sail to Africa. Instead, they sailed north up the east coast of the United States, sure that the ship would be intercepted and the Africans returned to Cuba as slaves. The ] '']'' seized ''La Amistad'' off ] on Long Island, New York. Pieh and his group escaped the ship but were caught offshore by citizens. They were incarcerated in ] on charges of murder and piracy. The man who captured Pieh and his group claimed them as property. ''La Amistad'' was towed to New London, Connecticut, and those remaining onboard were arrested. None of the 43 survivors on the ship spoke English, so they could not explain what had taken place. Eventually, language professor ] found ] to act as interpreter, and they learned of the abduction. | |||

| Two lawsuits were filed. The first case was brought by the ''Washington'' ship officers over salvage property claims, and the second case charged the Spanish with enslaving Africans. Spain requested President ] to return the African captives to Cuba under international treaty. | |||

| ==The Ship== | |||

| ] | |||

| Strictly speaking, ''La Amistad'' was not a ] in the sense that she was not designed to transport ], nor did she engage in the ] of Africans to the Americas. ''La Amistad'' engaged in shorter, coastal trade. The primary cargo carried by ''La Amistad'' was ]-industry products, and her normal route ran from ] to her home port, ]. She also took on passengers and, on occasion, slaves for transport. The captives that ''La Amistad'' carried during the incident had been illegally transported to Cuba aboard the slave ship '']''. | |||

| Because of issues of ownership and jurisdiction, the case gained international attention as '']'' (1841). The case was finally decided by the ] in favor of the Mende people, restoring their freedom. It became a symbol in the United States in the movement to ]. | |||

| ===More Ships=== | |||

| True slave ships, such as ''Tecora'', were designed for the purpose of carrying as many slaves as possible. One distinguishing feature was the half-height ''between decks'', which allowed slaves to be chained down in a sitting or lying position, but which were not high enough to stand in, and thus were not suitable for any other cargo. The crew of ''La Amistad'', lacking the slave quarters, placed half the 53 captives in the hold, and the other half on deck. The captives were relatively free to move about, and this freedom of movement aided their revolt and commandeering of the vessel. | |||

| == |

==Description== | ||

| ''La Amistad'' was a 19th-century two-] schooner of about {{convert|120|ft|m}}. In 1839 it was owned by Ramón Ferrer, a Spanish national.<ref name="Adams">{{cite book|last1=Adams|first1=John Quincy|title=Argument|date=1841|publisher=S. W. Benedict|location=New York|pages=13–14|isbn=9781429710794|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=LZIsAAAAIAAJ|access-date= January 15, 2017}}</ref> Strictly speaking, ''La Amistad'' was not a typical ], as it was not designed like others to traffic massive numbers of enslaved Africans, nor did it engage in the ] of Africans to the Americas. The ship engaged in the shorter, domestic coastwise trade around Cuba and islands and coastal nations in the Caribbean. The primary cargo carried by ''La Amistad'' was sugar-industry products. It carried a limited number of passengers and enslaved Africans being trafficked for delivery or sale around the island.{{Citation needed|date=January 2017}} | |||

| After being moored at the wharf behind the Custom House in ], ], for a year and a half, ''La Amistad'' was auctioned off by the ] in October 1840. Captain George Hawford, of ], ], purchased the vessel and then had to get an ] passed so that he could register her. He renamed her ''Ion'' and, in late ], sailed her to ] and ] with a typical ] cargo of ], ], live ], and ]. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| After sailing her for a few years, he sold the boat in ] in ]. There appears to be no record of what became of the ''Ion'' under her new ] owners in the ]. | |||

| ===1839 slave revolt=== | |||

| == ''La Amistad'' in culture == | |||

| ] | |||

| On ] ], a play entitled ''The Long, Low Black Schooner'', purporting to be based on the revolt, opened in ] and played to full audiences. ''La Amistad'' was painted black at the time of the revolt. | |||

| {{Suppression of the Slave Trade}} | |||

| Captained by Ferrer, ''La Amistad'' left Havana on June 28, 1839, for the small port of Guanaja, near ], with some general cargo and 53 African captives bound for the sugar plantation where they were to be delivered.<ref name="Adams" /> These 53 ] captives (49 adults and four children) had been captured by African slave catchers or otherwise enslaved in ]<ref>, page 9 ff</ref> (in modern-day ]), sold to European slave traders and illegally transported from Africa to Havana, mostly aboard the Portuguese slave ship '']'', to be sold in Cuba. Although the United States and Britain had banned the Atlantic slave trade, Spain had not abolished slavery in its colonies.<ref name="Lawrance">{{cite book|last1=Lawrance|first1=Benjamin Nicholas|title=Amistad's Orphans : An Atlantic Story of Children, Slavery, and Smuggling.|date=2015|publisher=Yale University Press|location=|isbn=9780300198454|pages=130–131|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fIAKBgAAQBAJ|access-date= January 15, 2017}}</ref><ref name="WDL">{{cite web |url = http://www.wdl.org/en/item/3080/ |title = Unidentified Young Man |website = ] |date = 1839–1840 |access-date = July 28, 2013 }}</ref> The crew of ''La Amistad'', lacking purpose-built slave quarters, placed half the captives in the main hold and the other half on deck. The captives were relatively free to move about, which aided their revolt and commandeering of the vessel. In the main hold below decks, the captives found a rusty file and sawed through their manacles.<ref name=Finkenbine> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| |first=Roy E. | |||

| |last=Finkenbine | |||

| |editor-first=Jane | |||

| |editor-last=Hathaway | |||

| |title=Rebellion, Repression, Reinvention: Mutiny in Comparative Perspective | |||

| |publisher=Greenwood Publishing Group | |||

| |year=2001 | |||

| |isbn=978-0-275-97010-9 | |||

| |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6dLGTvbWiT0C&pg=PA238 | |||

| |chapter=13 The Symbolism of Slave Mutiny: Black Abolitionist Responses to the ''Amistad'' and ''Creole'' Incidents | |||

| |page=238 | |||

| |access-date=August 18, 2012 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| On about July 1, once free, the men below quickly went up on deck. Armed with machete-like ], they attacked the crew, successfully gaining control of the ship, under the leadership of ] (later known in the United States as ]). They killed the captain Ferrer as well as the ship's cook Celestino;<ref name="docsouth.unc.edu"></ref> two captives also died, two sailors Manuel Pagilla and Jacinto escaped in a small boat. Ferrer's slave/mulatto cabin boy Antonio <ref name="docsouth.unc.edu"/> was spared as were José Ruiz and Pedro Montes, the two alleged owners of the captives, so that they could guide the ship back to Africa.<ref name="Adams" /><ref name="WDL"/><ref name=Finkenbine/> While the Mende demanded to be returned home, the navigator Montes deceived them about the course, maneuvering the ship north along the North American coast until they reached the eastern tip of ], New York. | |||

| A 1997 film, '']'', directed by ], examines the historical incident. | |||

| Several New York pilot boats came across ''La Amistad'' as on 21 August 1839, when she was discovered thirty miles southeast of ] by the pilot-boat ] who supplied the men with water and bread. When they attempted to board the pilot-boat to escape, the pilot-boat cut the rope that was attached to ''La Amistad.'' The pilots then communicated what they felt was a ] to the ].<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.newspapers.com/image/369544801/?terms=%22something%20like%20a%20pirate%22&match=1|title=Something like a Pirate.|work=Hartford Courant|place= Hartford, Connecticut |date=27 Aug 1839|page=2|via=]|url-access=limited|access-date=15 Jan 2021}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.newspapers.com/image/176607993/?terms=%22pilot%20boat%20Blossom%22&match=1|title=Reprduced slave ship will house black history exhibit.|work=Hartford Courant|place= Hartford, Connecticut |date=13 Mar 1995|page=9|via=]|url-access=limited|access-date=15 Jan 2021}}</ref> Two days later, the '']'' pilot boat came across ''La Amistad'' when she was twenty-five miles east of ]. When Captain Seaman of the ''Gratitude'' wanted to put a pilot aboard, one of the ringleaders of ''La Amistad '' ordered the men to fire on the ''Gratitude''. Gun shots hit the pilot boat but she was able to escape.<ref>{{cite book|last= Hunt|first= Bernice Kohn |url=https://archive.org/details/amistadmutiny00hunt/page/4/mode/2up?q=Gratitude |title=The Amistad mutiny. |work=McCall Pub. Co. |place= New York |date=1971|pages=4–5|isbn= 9780841520356 |access-date=25 Oct 2021}}</ref> | |||

| Artist ] completed a mural depicting the events that occurred on board the ''Amistad''. The six-panel sequence is on display at the Savery Library (named for founder ]), on the campus of ], ]. A mural of the ship itself is also embedded in the floor of the library, and school tradition dictates that it not be trodden on. | |||

| Discovered by the naval ] {{USS|Washington|1837|6}} while on surveying duties, ''La Amistad'' was taken into United States custody.<ref name="Adams"/><ref>Between 1838 and 1848, the USRC ''Washington'' was transferred from the ] to the ]. See: Howard I. Chapelle, ''The History of the American Sailing Navy''. New York: Norton / Bonanza Books (1949), {{ISBN|0-517-00487-9}}</ref>{{page needed|date=June 2020}} By the time of their trial, six of the captives had died.<ref name="docsouth.unc.edu"/> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| In honour of the described events name "Amistad" is carried with street in a china-town of ]. | |||

| ====Court case==== | |||

| === Freedom Schooner Amistad === | |||

| The ''Washington'' officers brought the first case to federal district court over salvage claims, while the second case began in a Connecticut court after the state arrested the Spanish traders on charges of enslaving free Africans.<ref name="WDL"/> The Spanish foreign minister, however, demanded that ''La Amistad'' and its cargo be released from custody and the Mende captives sent to Cuba for punishment by Spanish authorities. The Van Buren administration accepted the Spanish crown's argument, but Secretary of State ] explained that the President could not order the release of ''La Amistad'' and its cargo because the executive could not interfere with the judiciary under American law. He also could not release the Spanish traders from imprisonment in Connecticut because that would constitute federal intervention in a matter of state jurisdiction.{{citation needed|date=March 2020}} Abolitionists ], ], and ] formed the Amistad Committee to raise funds for the defense of ''La Amistad'''s captives. Roger Sherman Baldwin, grandson of ] and a prominent abolitionist, represented the captives in the New Haven court to decide the fate of the Mende people. Baldwin and former President ]<ref>{{cite book|editor-last=Rodriguez|editor-first=Junius|title=Encyclopedia of Emancipation and Abolition in the Transatlantic World|publisher=M.E. Sharpe |year=2007 |pages=9–11}}</ref> argued the case before the Supreme Court which ruled in favor of the Africans. | |||

| Between 1998 and 2000, ''Freedom Schooner Amistad'', a recreation of ''La Amistad'', was built in ], ], ], using traditional skills and construction techniques common to wooden schooners built in the ]. The modern day''Amistad'' is NOT an exact replica of ''La Amistad'', the ship is slightly longer and have higher freeboard. There were no old blueprints of the original. The new schooner was build using a general knowledge of the Baltimore Clippers and art drawings from the era. Some of the tools used in the project were the same as those that might have been used by a 19th century shipwright while others were electrically powered. Tri-Coastal Marine<ref></ref>, designers of ''Freedom Schooner Amistad'', used modern computer technology to provide plans for the vessel. Bronze bolts are used as fastenings throughout the ship. ''Freedom Schooner Amistad'' has an external ballast keel made of lead and two ] diesel engines. None of this technology was available to 19th century builders. | |||

| {{Main|United States v. The Amistad}} | |||

| ''Freedom Schooner Amistad'' is operated by ] Inc., a ] based in ], Connecticut.<ref></ref> The ship's mission is to educate the public on the history of ], ], and ]. Her homeport is New Haven, where the ''Amistad'' trial took place. She also travels to port cities for educational opportunities. The ''Freedom Schooner Amistad'' is the State ] and ] Ambassador of Connecticut.<ref>; ''Connecticut State Register & Manual''; retrieved on ], ]</ref> | |||

| ]'' on August 31, 1839]] | |||

| ] | |||

| A widely publicized court case ensued in New Haven to settle legal issues about the ship and the status of the Mende captives. They were at risk of execution if convicted of mutiny, and they became a popular cause among ]. Since 1808, the United States and Britain had prohibited the international slave trade.<ref> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| |url=http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llsl&fileName=002/llsl002.db&recNum=0463 | |||

| |work=U.S. Congressional House Proceedings. 9th Congress. 2nd Session | |||

| |title=A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875 | |||

| |chapter=22 Statutes at Large | |||

| |page=426. ''American Memory'' | |||

| |publisher=Library of Congress | |||

| |access-date=July 11, 2012 | |||

| }}</ref> In order to avoid the international prohibition on the African slave trade, the ship's owners fraudulently described the Mende as having been born in Cuba and said that they were being sold in the Spanish domestic slave trade. The court had to determine if the Mende were to be considered salvage and thus the property of naval officers who had taken custody of the ship (as was legal in such cases), the property of the Cuban buyers, or the property of Spain, as Queen ] claimed.{{citation needed|date=June 2020}} A question was whether the circumstances of the capture and transport of the Mende meant that they were legally free and had acted as free men rather than slaves.<ref name="WDL"/> | |||

| Judges ruled in favor of the Africans in the district and circuit courts, and the '']'' case reached the US Supreme Court on appeal. In 1841, it ruled that the Mende people had been illegally transported and held as slaves, and they had rebelled in self-defense.{{citation needed|date=June 2020}} It ordered them freed.<ref name="WDL"/> The US government did not provide any aid, but 35 survivors returned to Africa in 1842,<ref name="WDL"/> aided by funds raised by the ], a black group founded by ]. He was a Congregational minister and fugitive slave in ], New York who was active in the abolitionist movement.<ref>Webber, Christopher L. (2011). ''American to the Backbone: The Life of James W.C. Pennington, the Fugitive Slave Who Became One of the First Black Abolitionists.'' New York: Pegasus Books. {{ISBN|1605981753}}, pp. 162–169.</ref> The Spanish government claimed that the Mende people were Spanish citizens not of African origin. This created tension among the U.S. government, the Spanish crown, and the British government, which had outlawed the slave trade in the British Empire with the ] and had recently abolished slavery in the British Empire with the ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.nps.gov/articles/amistad-how-it-began.htm|title=Amistad: How it Began |website=U.S. National Park Service |date=August 2, 2017 |language=en|access-date=2020-02-26}}</ref> | |||

| ==== The Atlantic Freedom Tour ==== | |||

| ''Freedom Schooner Amistad'' set sail on ], ], from New Haven on the "", a 14,000-mile transatlantic voyage to ], ], ], and the ] to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the abolition of the ] in ] (1807) and the ] (1808). The ship arrived in ] on ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.24hourmuseum.org.uk/bristol/news/ART50181.html |title=Amistad Sails Into Bristol For Slave Trade Commemorations |accessdate=2007-09-04 |format= |work=24 Hour Museum }}</ref> | |||

| ===Later years=== | |||

| ] was one of the ports of the ] portion of the ''Amistad's'' Tour. The schooner sailed up the ] under the ] on ], ], and moored for several days in ], where she attracted a great deal of attention. | |||

| ''La Amistad'' had been moored at the wharf behind the ] in ] for a year and a half, and it was auctioned off by the ] in October 1840. Captain George Hawford of ] purchased the vessel and then needed an act of Congress passed to register it.{{citation needed |date=August 2012}} He renamed it ''Ion''. In late 1841, he sailed ''Ion'' to ] and ] with a typical ] cargo of onions, apples, live poultry, and cheese. | |||

| Hawford sold ''Ion'' in ] in 1844.{{citation needed|date=March 2020}} There is no record of what became of it under the new French owners in the Caribbean. | |||

| ], ], UNESCO's designated International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade, which fell during the ship's visit to ], was marked by the opening of the ] in Liverpool - the first museum of its type to open in the United Kingdom. | |||

| ==Legacy== | |||

| {|{{Infobox ship begin |infobox caption=''Freedom Schooner Amistad'' |display title=none}} | |||

| {{Infobox ship image | |||

| |Ship image=Amistad2010.jpg | |||

| |Ship caption=''Freedom Schooner Amistad'' at ] in 2010 | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Infobox ship career | |||

| |Hide header =title | |||

| |Ship country=United States | |||

| |Ship flag={{USN flag|2000}} | |||

| |Ship name= | |||

| |Ship owner=*2000–2015: Amistad America, Inc., New Haven, Connecticut | |||

| *from 2015: Discovering Amistad, Inc., New Haven, Connecticut | |||

| |Ship ordered= | |||

| |Ship builder=] | |||

| |Ship original cost= | |||

| |Ship laid down=1998 | |||

| |Ship launched= March 25, 2000 | |||

| |Ship acquired= | |||

| |Ship commissioned= | |||

| |Ship decommissioned= | |||

| |Ship in service= | |||

| |Ship out of service= | |||

| |Ship renamed= | |||

| |Ship struck= | |||

| |Ship reinstated= | |||

| |Ship honours= | |||

| |Ship captured= | |||

| |Ship fate= | |||

| |Ship notes= | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Infobox ship characteristics | |||

| |Hide header= | |||

| |Header caption= | |||

| |Ship class= | |||

| |Ship tons burthen=136 L. tons | |||

| |Ship length={{convert|80.7|ft|abbr=on}} | |||

| |Ship beam={{convert|22.9|ft|abbr=on}} | |||

| |Ship draft={{convert|10.1|ft|abbr=on}} | |||

| |Ship hold depth= | |||

| |Ship propulsion=Sail, 2 Caterpillar diesel engines | |||

| |Ship sail plan=Topsail ] | |||

| |Ship complement= | |||

| |Ship armament= | |||

| |Ship notes= | |||

| }} | |||

| |} | |||

| The ] stands in front of ] in New Haven, Connecticut, where many of the events occurred related to the affair in the United States. | |||

| The ] at ], ] is devoted to research about slavery, abolition, civil rights, and African Americans; it commemorates the revolt of Mende people on the ship by the same name.{{citation needed|date=July 2013}} A collection of portraits of ''La Amistad'' survivors is held in the collection of ], drawn by William H. Townsend during the survivors' trial.<ref name="WDL"/> | |||

| ===Replica=== | |||

| Between 1998 and 2000, artisans at ] in ] built a replica of ''La Amistad'' using traditional tools and construction techniques common to wooden schooners built in the 19th century, but using modern materials and engines, officially named ''Amistad''. It was promoted as "Freedom Schooner ''Amistad''".<ref name="USCG">{{cite web|title=Amistad|url=http://www.st.nmfs.noaa.gov/pls/webpls/cgv_pkg.vessel_id_list?vessel_id_in=1096750|website=Coast Guard Vessel Documentation|publisher=NOAA Fisheries|access-date= January 14, 2017|location=Silver Spring, MD |url-status=dead |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20170116160856/http://www.st.nmfs.noaa.gov/pls/webpls/cgv_pkg.vessel_id_list?vessel_id_in=1096750 |archive-date= Jan 16, 2017 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|last1=Marder|first1=Alfred L.|title=About the Freedom Schooner ''Amistad''|url=http://www.amistadcommitteeinc.org/story-of-the-amistad|publisher=Amistad Committee, Inc|access-date=January 14, 2017|location=New Haven, CT|archive-date=August 11, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210811024205/https://www.amistadcommitteeinc.org/story-of-the-amistad|url-status=dead}}</ref> The modern-day ship is not an exact replica of ''La Amistad'', as it is slightly longer and has higher ]. There were no old blueprints of the original. | |||

| The new schooner was built using a general knowledge of the ]s and art drawings from the era. Some of the tools used in the project were the same as those that might have been used by a 19th-century shipwright, while others were powered. Tri-Coastal Marine,<ref>{{cite web | |||

| |url = http://www.tricoastal.com/amistad.html | |||

| |title = The New Topsail Schooner ''Amistad'' | |||

| |access-date = August 18, 2012 | |||

| |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20120209131410/http://www.tricoastal.com/amistad.html | |||

| |archive-date = February 9, 2012 | |||

| |url-status = dead | |||

| }}</ref> designers of "Freedom Schooner ''Amistad''", used modern computer technology to develop plans for the vessel. Bronze bolts are used as fastenings throughout the ship. ''Freedom Schooner Amistad'' has two ] diesel engines and an external ballast keel made of lead. This technology was unavailable to 19th-century builders. | |||

| "Freedom Schooner ''Amistad''" was operated by Amistad America, Inc. based in New Haven, Connecticut. The ship's mission was to educate the public on the history of slavery, abolition, discrimination, and civil rights. The homeport is New Haven, where the ''Amistad'' trial took place. It has also traveled to port cities for educational opportunities. It was also the State Flagship and Tall ship Ambassador of Connecticut.<ref>{{cite web | |||

| |url=http://www.sots.ct.gov/sots/cwp/view.asp?a=3188&q=392608 | |||

| |title=State of Connecticut Sites, Seals, & Symbols | |||

| |work=Connecticut State Register & Manual | |||

| |access-date=August 18, 2012 | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120926135650/http://www.sots.ct.gov/sots/cwp/view.asp?a=3188&q=392608 | |||

| |archive-date=September 26, 2012 | |||

| |url-status=dead | |||

| }}</ref> The ship made several commemorative voyages: one in 2007 to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the abolition of the ] in Britain (1807) and the United States (1808),<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.culture24.org.uk/history+%2526+heritage/work+%2526+daily+life/race+and+identity/art50181 | |||

| |title=Amistad Sails Into Bristol for Slave Trade Commemorations | |||

| |publisher=] | |||

| |date= August 30, 2007 | |||

| |access-date=December 7, 2009 | |||

| }}</ref> and one in 2010 to celebrate the 10th anniversary of its 2000 launching at Mystic Seaport. It undertook a two-year refit at Mystic Seaport starting in 2010 and was subsequently mainly used for sea training in ] and for film work.<ref name=Courant3>{{cite news| last=Lender| first=Jon| title=Troubles Aboard the Amistad| url=https://www.courant.com/2013/08/31/troubles-aboard-the-amistad/| access-date= October 30, 2013| newspaper=Hartford Courant| date= August 3, 2013}}</ref> | |||

| In 2013, Amistad America lost its non-profit organization status after failing to file tax returns for three years amid concern for accountability for public funding from the state of Connecticut.<ref name=Courant>{{cite news| title=State Missed Signs As Tall Ship Amistad Foundered| url=https://www.courant.com/2013/09/03/state-missed-signs-as-tall-ship-amistad-foundered-2/| access-date= October 30, 2013| newspaper=The Hartford Courant| date= September 3, 2013}}</ref><ref name=Courant2>{{cite news| last=Lender| first=Jon| title=Malloy Wants 'Action Plan' For Troubled Amistad| url=https://www.courant.com/2013/09/04/malloy-wants-action-plan-for-troubled-amistad/| access-date= October 30, 2013| newspaper=]| date= September 4, 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite news| last=Collins| first=David| title=Amistad still sails some troubled waters| url=http://www.theday.com/article/20130510/NWS05/305109933| access-date= October 30, 2013 |newspaper=]| date= May 10, 2013| location=New London, CT}}</ref> The company was later put into liquidation, and the non-profit Discovering Amistad Inc.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://discoveringamistad.org/|title=Discovering Amistad|website=Discovering Amistad}}</ref> purchased the ship from the receiver in November 2015. ''Amistad'' then returned to educational and promotional activity in New Haven, Connecticut.<ref name="The Day">{{cite news|last1=Wojtas|first1=Joe|title=Discovering Amistad charts new course for schooner|url=http://www.theday.com/article/20151231/NWS01/151239865|access-date= January 14, 2017|work=The Day|date= December 31, 2015|location=New London, CT}}</ref> | |||

| == In popular culture == | |||

| {{Unreferenced section|date=February 2022}} | |||

| *On 2 September 1839, a play entitled ''The Long, Low Black Schooner'', based on the revolt, opened in ] and played to full houses. (''La Amistad'' was painted black at the time of the revolt.) | |||

| *The slave revolt aboard ''La Amistad,'' the background of the slave trade, and its subsequent trial are retold in a poem by ] entitled "]", first published in 1962.<ref>{{cite book| last=Bloom| first=Harold| title=Poets and Poems| year=2005| publisher=Chelsea House Publishers| location=New York| isbn=0-7910-8225-3| pages=348–351| quote=All this is merely preamble to a rather rapid survey of a few of Hayden's superb sequences, of which ''Middle Passage'' is the most famous.}}</ref> | |||

| * In ]'s novel '']'' (1988), depicting an ] in which the South won the ], a group of abolitionist conspirators infiltrating ] calls itself "Amistad". | |||

| *The film '']'' (1997), directed by ], dramatized the historical incidents. Major actors were ], as a freed slave-turned-abolitionist in New Haven; ], as ]; ], as ], an unorthodox, but influential lawyer; and ], as ] (Sengbe Peah). | |||

| *The opera ''Amistad'' (1997), composed by Anthony Davis with libretto by Thulani Davis, was commissioned and premiered by Lyric Opera of Chicago in 1997.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://operawire.com/opera-profile-anthony-davis-amistad/|title=Opera Profile: Anthony Davis' 'Amistad'|first=David|last=Salazar|date=July 22, 2020|website=OperaWire}}</ref> The opera underwent a major revision and was then presented at the Spoleto Festival USA in 2008. | |||

| * The 1999 hit single "]", performed by ], references the "chains of Amistad". | |||

| *In January 2011, ] published ''Ardency'', a collection of poems written over 20 years by American poet ] which "gathers here a chorus of voices that tells the story of the Africans who mutinied on board the slave ship ''Amistad''". | |||

| {{Clear}} | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| *] | |||

| *'']'', a Supreme Court case arising out of the rebellion aboard the ship | |||

| *] | |||

| *], a movie about the court case. | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| == |

==References== | ||

| {{ |

{{Reflist|30em}} | ||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| * {{cite book|author=Owens, William A.|title=Black Mutiny: The Revolt on the Schooner Amistad|url=https://archive.org/details/blackmutinyrevol00owen_2|url-access=registration|publisher= Black Classic Press|date=1997|isbn=9781574780048}} | |||

| * {{cite book|author=Pesci, David |title=Amistad|publisher= Da Capo Press|date= 1997}} | |||

| * {{cite book|author=Rediker, Marcus |title=The Amistad Rebellion: An Atlantic Odyssey of Slavery and Freedom|url=https://archive.org/details/amistadrebellion00redi |url-access=registration |publisher= Viking |location=New York|date= 2012|isbn=9780670025046}} | |||

| * {{cite journal|author=Zeuske, Michael |title=Rethinking the Case of the Schooner ''Amistad'': Contraband and Complicity after 1808/1820|journal= Slavery & Abolition|volume= 35|number= 1 |date=2014|pages=156–164|doi=10.1080/0144039X.2013.798173|s2cid=143870695}} | |||

| {{Wikisource|The Captives of the Amistad|left=yes}} | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{Commons}} | |||

| * | |||

| * |

* | ||

| * | |||

| *, YouTube video | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * 1998-02-27, The Walter J. Brown Media Archives & Peabody Awards Collection at the ], ] | |||

| {{US state ships}} | |||

| {{US Coast Guard navbox}} | |||

| {{1839 shipwrecks}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:La Amistad}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Coord|41.361|-71.966|display=title}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 16:30, 12 January 2025

1839 slave-ship takeover See also: United States v. The Amistad For other uses, see Amistad (disambiguation). La Amistad off Culloden Point, Long Island, New York on August 26, 1839 La Amistad off Culloden Point, Long Island, New York on August 26, 1839(contemporary painting, artist unknown) | |

| Name | La Amistad |

| Owner | Ramón Ferrer |

| Acquired | Pre-June 1839 |

| Name | Ion |

| Owner | Captain George Hawford, Newport, Rhode Island |

| Acquired | October 1840 |

| Acquired | 1844 |

| General characteristics | |

| Length | 120 ft (37 m) |

| Sail plan | Schooner |

La Amistad (pronounced [la a.misˈtað]; Spanish for Friendship) was a 19th-century two-masted schooner owned by a Spaniard living in Cuba. It became renowned in July 1839 for a slave revolt by Mende captives who had been captured and sold to European slave traders and illegally transported by a Portuguese ship from West Africa to Cuba, in violation of European treaties against the Atlantic slave trade. Spanish plantation owners Don José Ruiz and Don Pedro Montes bought 53 captives in Havana, Cuba, including four children, and were transporting them on the ship to their plantations near Puerto Príncipe (modern Camagüey, Cuba). The revolt began after the schooner's cook jokingly told the slaves that they were to be "killed, salted, and cooked." Sengbe Pieh (also known as Joseph Cinqué) unshackled himself and the others on the third day and started the revolt. They took control of the ship, killing the captain and the cook. Two Africans were also killed in the melee.

Pieh ordered Ruiz and Montes to sail to Africa. Instead, they sailed north up the east coast of the United States, sure that the ship would be intercepted and the Africans returned to Cuba as slaves. The revenue cutter Washington seized La Amistad off Montauk Point on Long Island, New York. Pieh and his group escaped the ship but were caught offshore by citizens. They were incarcerated in New Haven, Connecticut on charges of murder and piracy. The man who captured Pieh and his group claimed them as property. La Amistad was towed to New London, Connecticut, and those remaining onboard were arrested. None of the 43 survivors on the ship spoke English, so they could not explain what had taken place. Eventually, language professor Josiah Gibbs found James Covey to act as interpreter, and they learned of the abduction.

Two lawsuits were filed. The first case was brought by the Washington ship officers over salvage property claims, and the second case charged the Spanish with enslaving Africans. Spain requested President Martin Van Buren to return the African captives to Cuba under international treaty.

Because of issues of ownership and jurisdiction, the case gained international attention as United States v. The Amistad (1841). The case was finally decided by the Supreme Court of the United States in favor of the Mende people, restoring their freedom. It became a symbol in the United States in the movement to abolish slavery.

Description

La Amistad was a 19th-century two-masted schooner of about 120 feet (37 m). In 1839 it was owned by Ramón Ferrer, a Spanish national. Strictly speaking, La Amistad was not a typical slave ship, as it was not designed like others to traffic massive numbers of enslaved Africans, nor did it engage in the Middle Passage of Africans to the Americas. The ship engaged in the shorter, domestic coastwise trade around Cuba and islands and coastal nations in the Caribbean. The primary cargo carried by La Amistad was sugar-industry products. It carried a limited number of passengers and enslaved Africans being trafficked for delivery or sale around the island.

History

1839 slave revolt

Captained by Ferrer, La Amistad left Havana on June 28, 1839, for the small port of Guanaja, near Puerto Príncipe, Cuba, with some general cargo and 53 African captives bound for the sugar plantation where they were to be delivered. These 53 Mende captives (49 adults and four children) had been captured by African slave catchers or otherwise enslaved in Mendiland (in modern-day Sierra Leone), sold to European slave traders and illegally transported from Africa to Havana, mostly aboard the Portuguese slave ship Teçora, to be sold in Cuba. Although the United States and Britain had banned the Atlantic slave trade, Spain had not abolished slavery in its colonies. The crew of La Amistad, lacking purpose-built slave quarters, placed half the captives in the main hold and the other half on deck. The captives were relatively free to move about, which aided their revolt and commandeering of the vessel. In the main hold below decks, the captives found a rusty file and sawed through their manacles.

On about July 1, once free, the men below quickly went up on deck. Armed with machete-like cane knives, they attacked the crew, successfully gaining control of the ship, under the leadership of Sengbe Pieh (later known in the United States as Joseph Cinqué). They killed the captain Ferrer as well as the ship's cook Celestino; two captives also died, two sailors Manuel Pagilla and Jacinto escaped in a small boat. Ferrer's slave/mulatto cabin boy Antonio was spared as were José Ruiz and Pedro Montes, the two alleged owners of the captives, so that they could guide the ship back to Africa. While the Mende demanded to be returned home, the navigator Montes deceived them about the course, maneuvering the ship north along the North American coast until they reached the eastern tip of Long Island, New York.

Several New York pilot boats came across La Amistad as on 21 August 1839, when she was discovered thirty miles southeast of Sandy Hook by the pilot-boat Blossom who supplied the men with water and bread. When they attempted to board the pilot-boat to escape, the pilot-boat cut the rope that was attached to La Amistad. The pilots then communicated what they felt was a slave ship to the Collector of the Port of New York. Two days later, the Gratitude pilot boat came across La Amistad when she was twenty-five miles east of Fire Island. When Captain Seaman of the Gratitude wanted to put a pilot aboard, one of the ringleaders of La Amistad ordered the men to fire on the Gratitude. Gun shots hit the pilot boat but she was able to escape.

Discovered by the naval brig USS Washington while on surveying duties, La Amistad was taken into United States custody. By the time of their trial, six of the captives had died.

Court case

The Washington officers brought the first case to federal district court over salvage claims, while the second case began in a Connecticut court after the state arrested the Spanish traders on charges of enslaving free Africans. The Spanish foreign minister, however, demanded that La Amistad and its cargo be released from custody and the Mende captives sent to Cuba for punishment by Spanish authorities. The Van Buren administration accepted the Spanish crown's argument, but Secretary of State John Forsyth explained that the President could not order the release of La Amistad and its cargo because the executive could not interfere with the judiciary under American law. He also could not release the Spanish traders from imprisonment in Connecticut because that would constitute federal intervention in a matter of state jurisdiction. Abolitionists Joshua Leavitt, Lewis Tappan, and Simeon Jocelyn formed the Amistad Committee to raise funds for the defense of La Amistad's captives. Roger Sherman Baldwin, grandson of Roger Sherman and a prominent abolitionist, represented the captives in the New Haven court to decide the fate of the Mende people. Baldwin and former President John Quincy Adams argued the case before the Supreme Court which ruled in favor of the Africans.

Main article: United States v. The Amistad

A widely publicized court case ensued in New Haven to settle legal issues about the ship and the status of the Mende captives. They were at risk of execution if convicted of mutiny, and they became a popular cause among abolitionists in the United States. Since 1808, the United States and Britain had prohibited the international slave trade. In order to avoid the international prohibition on the African slave trade, the ship's owners fraudulently described the Mende as having been born in Cuba and said that they were being sold in the Spanish domestic slave trade. The court had to determine if the Mende were to be considered salvage and thus the property of naval officers who had taken custody of the ship (as was legal in such cases), the property of the Cuban buyers, or the property of Spain, as Queen Isabella II claimed. A question was whether the circumstances of the capture and transport of the Mende meant that they were legally free and had acted as free men rather than slaves.

Judges ruled in favor of the Africans in the district and circuit courts, and the United States v. The Amistad case reached the US Supreme Court on appeal. In 1841, it ruled that the Mende people had been illegally transported and held as slaves, and they had rebelled in self-defense. It ordered them freed. The US government did not provide any aid, but 35 survivors returned to Africa in 1842, aided by funds raised by the United Missionary Society, a black group founded by James W.C. Pennington. He was a Congregational minister and fugitive slave in Brooklyn, New York who was active in the abolitionist movement. The Spanish government claimed that the Mende people were Spanish citizens not of African origin. This created tension among the U.S. government, the Spanish crown, and the British government, which had outlawed the slave trade in the British Empire with the Slave Trade Act 1807 and had recently abolished slavery in the British Empire with the Slavery Abolition Act 1833.

Later years

La Amistad had been moored at the wharf behind the US Custom House in New London, Connecticut for a year and a half, and it was auctioned off by the U.S. Marshal in October 1840. Captain George Hawford of Newport, Rhode Island purchased the vessel and then needed an act of Congress passed to register it. He renamed it Ion. In late 1841, he sailed Ion to Bermuda and Saint Thomas with a typical New England cargo of onions, apples, live poultry, and cheese.

Hawford sold Ion in Guadeloupe in 1844. There is no record of what became of it under the new French owners in the Caribbean.

Legacy

Freedom Schooner Amistad at Mystic Seaport in 2010 Freedom Schooner Amistad at Mystic Seaport in 2010

| |

| Owner |

|

| Builder | Mystic Seaport |

| Laid down | 1998 |

| Launched | March 25, 2000 |

| General characteristics | |

| Tons burthen | 136 L. tons |

| Length | 80.7 ft (24.6 m) |

| Beam | 22.9 ft (7.0 m) |

| Draft | 10.1 ft (3.1 m) |

| Propulsion | Sail, 2 Caterpillar diesel engines |

| Sail plan | Topsail schooner |

The Amistad Memorial stands in front of New Haven City Hall and County Courthouse in New Haven, Connecticut, where many of the events occurred related to the affair in the United States.

The Amistad Research Center at Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana is devoted to research about slavery, abolition, civil rights, and African Americans; it commemorates the revolt of Mende people on the ship by the same name. A collection of portraits of La Amistad survivors is held in the collection of Yale University, drawn by William H. Townsend during the survivors' trial.

Replica

Between 1998 and 2000, artisans at Mystic Seaport in Mystic, Connecticut built a replica of La Amistad using traditional tools and construction techniques common to wooden schooners built in the 19th century, but using modern materials and engines, officially named Amistad. It was promoted as "Freedom Schooner Amistad". The modern-day ship is not an exact replica of La Amistad, as it is slightly longer and has higher freeboard. There were no old blueprints of the original.

The new schooner was built using a general knowledge of the Baltimore Clippers and art drawings from the era. Some of the tools used in the project were the same as those that might have been used by a 19th-century shipwright, while others were powered. Tri-Coastal Marine, designers of "Freedom Schooner Amistad", used modern computer technology to develop plans for the vessel. Bronze bolts are used as fastenings throughout the ship. Freedom Schooner Amistad has two Caterpillar diesel engines and an external ballast keel made of lead. This technology was unavailable to 19th-century builders.

"Freedom Schooner Amistad" was operated by Amistad America, Inc. based in New Haven, Connecticut. The ship's mission was to educate the public on the history of slavery, abolition, discrimination, and civil rights. The homeport is New Haven, where the Amistad trial took place. It has also traveled to port cities for educational opportunities. It was also the State Flagship and Tall ship Ambassador of Connecticut. The ship made several commemorative voyages: one in 2007 to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the abolition of the Atlantic slave trade in Britain (1807) and the United States (1808), and one in 2010 to celebrate the 10th anniversary of its 2000 launching at Mystic Seaport. It undertook a two-year refit at Mystic Seaport starting in 2010 and was subsequently mainly used for sea training in Maine and for film work.

In 2013, Amistad America lost its non-profit organization status after failing to file tax returns for three years amid concern for accountability for public funding from the state of Connecticut. The company was later put into liquidation, and the non-profit Discovering Amistad Inc. purchased the ship from the receiver in November 2015. Amistad then returned to educational and promotional activity in New Haven, Connecticut.

In popular culture

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (February 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

- On 2 September 1839, a play entitled The Long, Low Black Schooner, based on the revolt, opened in New York City and played to full houses. (La Amistad was painted black at the time of the revolt.)

- The slave revolt aboard La Amistad, the background of the slave trade, and its subsequent trial are retold in a poem by Robert Hayden entitled "Middle Passage", first published in 1962.

- In Robert Skimin's novel Gray Victory (1988), depicting an alternate history in which the South won the American Civil War, a group of abolitionist conspirators infiltrating Richmond, Virginia calls itself "Amistad".

- The film Amistad (1997), directed by Steven Spielberg, dramatized the historical incidents. Major actors were Morgan Freeman, as a freed slave-turned-abolitionist in New Haven; Anthony Hopkins, as John Quincy Adams; Matthew McConaughey, as Roger Sherman Baldwin, an unorthodox, but influential lawyer; and Djimon Hounsou, as Cinque (Sengbe Peah).

- The opera Amistad (1997), composed by Anthony Davis with libretto by Thulani Davis, was commissioned and premiered by Lyric Opera of Chicago in 1997. The opera underwent a major revision and was then presented at the Spoleto Festival USA in 2008.

- The 1999 hit single "My Love Is Your Love", performed by Whitney Houston, references the "chains of Amistad".

- In January 2011, Random House published Ardency, a collection of poems written over 20 years by American poet Kevin Young which "gathers here a chorus of voices that tells the story of the Africans who mutinied on board the slave ship Amistad".

See also

- African Slave Trade Patrol

- Bibliography of early American naval history

- Blockade of Africa

- Creole case

- John Quincy Adams and abolitionism

- List of historical schooners

- List of ships captured in the 19th century

- Sarah Margru Kinson

References

- "Teaching With Documents:The Amistad Case". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- Purdy, Elizabeth. Encyclopedia of African American History, 1619–1895: From the Colonial Period to the Age of Frederick Douglass. Oxford African American Studies Center. pp. Amistad.

- ^ Adams, John Quincy (1841). Argument. New York: S. W. Benedict. pp. 13–14. ISBN 9781429710794. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- History of the Amistad Captives, page 9 ff

- Lawrance, Benjamin Nicholas (2015). Amistad's Orphans : An Atlantic Story of Children, Slavery, and Smuggling. : Yale University Press. pp. 130–131. ISBN 9780300198454. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ "Unidentified Young Man". World Digital Library. 1839–1840. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ^ Finkenbine, Roy E. (2001). "13 The Symbolism of Slave Mutiny: Black Abolitionist Responses to the Amistad and Creole Incidents". In Hathaway, Jane (ed.). Rebellion, Repression, Reinvention: Mutiny in Comparative Perspective. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-275-97010-9. Retrieved August 18, 2012.

- ^ John Barber "A History of the AMistead Captives

- "Something like a Pirate". Hartford Courant. Hartford, Connecticut. 27 Aug 1839. p. 2. Retrieved 15 Jan 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Reprduced slave ship will house black history exhibit". Hartford Courant. Hartford, Connecticut. 13 Mar 1995. p. 9. Retrieved 15 Jan 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Hunt, Bernice Kohn (1971). The Amistad mutiny. New York. pp. 4–5. ISBN 9780841520356. Retrieved 25 Oct 2021.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Between 1838 and 1848, the USRC Washington was transferred from the United States Revenue Cutter Service to the US Navy. See: Howard I. Chapelle, The History of the American Sailing Navy. New York: Norton / Bonanza Books (1949), ISBN 0-517-00487-9

- Rodriguez, Junius, ed. (2007). Encyclopedia of Emancipation and Abolition in the Transatlantic World. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 9–11.

-

"22 Statutes at Large". A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875. Library of Congress. p. 426. American Memory. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Webber, Christopher L. (2011). American to the Backbone: The Life of James W.C. Pennington, the Fugitive Slave Who Became One of the First Black Abolitionists. New York: Pegasus Books. ISBN 1605981753, pp. 162–169.

- "Amistad: How it Began". U.S. National Park Service. August 2, 2017. Retrieved 2020-02-26.

- "Amistad". Coast Guard Vessel Documentation. Silver Spring, MD: NOAA Fisheries. Archived from the original on Jan 16, 2017. Retrieved January 14, 2017.

- Marder, Alfred L. "About the Freedom Schooner Amistad". New Haven, CT: Amistad Committee, Inc. Archived from the original on August 11, 2021. Retrieved January 14, 2017.

- "The New Topsail Schooner Amistad". Archived from the original on February 9, 2012. Retrieved August 18, 2012.

- "State of Connecticut Sites, Seals, & Symbols". Connecticut State Register & Manual. Archived from the original on September 26, 2012. Retrieved August 18, 2012.

- "Amistad Sails Into Bristol for Slave Trade Commemorations". Culture24. August 30, 2007. Retrieved December 7, 2009.

- Lender, Jon (August 3, 2013). "Troubles Aboard the Amistad". Hartford Courant. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- "State Missed Signs As Tall Ship Amistad Foundered". The Hartford Courant. September 3, 2013. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- Lender, Jon (September 4, 2013). "Malloy Wants 'Action Plan' For Troubled Amistad". Hartford Courant. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- Collins, David (May 10, 2013). "Amistad still sails some troubled waters". The Day. New London, CT. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- "Discovering Amistad". Discovering Amistad.

- Wojtas, Joe (December 31, 2015). "Discovering Amistad charts new course for schooner". The Day. New London, CT. Retrieved January 14, 2017.

- Bloom, Harold (2005). Poets and Poems. New York: Chelsea House Publishers. pp. 348–351. ISBN 0-7910-8225-3.

All this is merely preamble to a rather rapid survey of a few of Hayden's superb sequences, of which Middle Passage is the most famous.

- Salazar, David (July 22, 2020). "Opera Profile: Anthony Davis' 'Amistad'". OperaWire.

Further reading

- Owens, William A. (1997). Black Mutiny: The Revolt on the Schooner Amistad. Black Classic Press. ISBN 9781574780048.

- Pesci, David (1997). Amistad. Da Capo Press.

- Rediker, Marcus (2012). The Amistad Rebellion: An Atlantic Odyssey of Slavery and Freedom. New York: Viking. ISBN 9780670025046.

- Zeuske, Michael (2014). "Rethinking the Case of the Schooner Amistad: Contraband and Complicity after 1808/1820". Slavery & Abolition. 35 (1): 156–164. doi:10.1080/0144039X.2013.798173. S2CID 143870695.

External links

- Amistad: Seeking Freedom in Connecticut, a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary

- Sarah Margru Kinson, the Two Worlds of an Amistad Captive

- Freedom Schooner Amistad sailing, YouTube video

- The Amistad Affair

- The current owners of the replica Amistad

- "Amistad Connecticut: A Legacy Reborn," 1998-02-27, The Walter J. Brown Media Archives & Peabody Awards Collection at the University of Georgia, American Archive of Public Broadcasting

| State ships of the United States | |

|---|---|

|

| Shipwrecks and maritime incidents in 1839 | |

|---|---|

| Shipwrecks |

|

| Other incidents |

|

| 1838 | |

41°21′40″N 71°57′58″W / 41.361°N 71.966°W / 41.361; -71.966

Categories:- La Amistad

- 1839 in the United States

- Schooners

- Slave rebellions in the United States

- Replica ships

- Two-masted ships

- Museum ships in Connecticut

- Spanish slave ships

- Museums in New Haven, Connecticut

- Captured ships

- Maritime incidents in July 1839

- Maritime incidents involving slave ships

- Fugitive American slaves

- American rebel slaves

- Abolitionism in the United States

- Post-1808 importation of slaves to the United States