| Revision as of 08:30, 19 February 2008 edit119.11.70.126 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 06:20, 21 December 2024 edit undoAdumbrativus (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Page movers8,997 editsm Update link target Flail (tool) (post-move cleanup) | ||

| (719 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Weapon consisting of a striking head flexibly attached to a handle}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{About|the weapon||Flail (disambiguation)}} | |||

| ]'s combat manual ''Arte De Athletica'']] | |||

| A '''flail''' is a weapon consisting of a striking head attached to a handle by a flexible rope, strap, or chain. The chief tactical virtue of the flail is its capacity to strike around a defender's shield or parry. Its chief liability is a lack of precision and the difficulty of using it in close combat, or closely-ranked formations. | |||

| There are two broad types of flail: a long, two-handed infantry weapon with a cylindrical head, and a shorter weapon with a round metal striking head. The longer cylindrical-headed flail is a hand weapon derived from the ], commonly used in ]. It was primarily considered a peasant's weapon, and while not common, they were deployed in Germany and Central Europe in the later ].<ref name="WagnerDrobná2014">{{cite book|author1=Eduard Wagner|author2=Zoroslava Drobná|author3=Jan Durdík|title=Medieval Costume, Armour and Weapons|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uACVAwAAQBAJ|date=5 May 2014|publisher=Courier Corporation|isbn=978-0-486-32025-0}}</ref> The smaller, more spherical-headed flail appears to be even less common; it appears occasionally in artwork from the 15th century onward, but many historians have expressed doubts that it ever saw use as an actual military weapon. | |||

| The '''flail''' is a medieval weapon made of one (or more) weights attached to a handle with a hinge or ]. There is some disagreement over the names for this weapon; the terms "]", and even "]" are variously applied, though these are used to describe other weapons, which are very different in usage from a weapon with a hinge or chain, commonly used in Europe from the ] to the ]. In construction, the morning star and flail have similar, if not identical, spiked heads. Thus, morning star is an acceptable name for this weapon, especially as the name "flail" is also used to describe a style of ] used for ]. | |||

| == The peasant flail == | |||

| The term "morning star" actually refers to the head of a weapon (the small round spiked ball) and can be used for either a morning star mace (on a shaft) or flail (if on a chain). Flails also sometimes had blunt round heads or flanges like a mace. Some written records point to small rings attached to chains on a flail used to inflict greater damage, but no historical examples are known to exist.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} | |||

| ] | |||

| In the ], a particular type of flail appears in several works being used as a weapon, which consists of a very long shaft with a hinged, roughly cylindrical striking end. In most cases, these are two-handed agricultural ]s, which were sometimes employed as an improvised weapon by peasant armies conscripted into military service or engaged in popular uprisings. For example, in the 1420–1497 period, the ] fielded large numbers of peasant foot soldiers armed with this type of flail.<ref name="WagnerDrobná2014"/><ref>Stephen Turnbull: The Hussite Wars 1419-36, Osprey MAA 409,2004</ref><ref>] ]</ref> | |||

| Some of these weapons featured anti personnel studs or spikes embedded in the striking end, or are shown being used by armored knights,<ref name="Freydal">{{Cite web | title = Colored plate depicting knights fighting with two-handed flails. | author = Maximilian I | author-link = Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor | work = Freydal | access-date = 2016-01-19 | url = http://www.h-u-m-rueegg.li/images/turnier-1.jpg| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20070702085850/http://www.h-u-m-rueegg.li/images/turnier-1.jpg | archive-date = 2007-07-02 }}</ref> suggesting they were made or at least modified specifically to be used as weapons. Such modified flails were used in the ] in the early 16th century.<ref>Douglas Miller : Armies of the German Peasant's War 1524-26,Osprey MAA 384,2003</ref><ref>]</ref> Several German ] or ''Fechtbücher'' from the 15th, 16th and 17th century feature illustrations and lessons on how to use the peasant flail (with or without spikes) or how to defend against it when attacked.<ref>{{Cite web | title = Talhoffer Fechtbuch (MS 78.A.15) Folio 60r | author = Hans Talhoffer | author-link = Hans Talhoffer | work = wiktenauer.com | date = c. 1450s | access-date = 2016-02-01 | url = http://wiktenauer.com/File:MS_78.A.15_60r.jpg }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web | title = Talhoffer Fechtbuch (MS 78.A.15) Folio 60v | author = Hans Talhoffer | author-link = Hans Talhoffer | work = wiktenauer.com | date = c. 1450s | access-date = 2016-02-01 | url = http://wiktenauer.com/File:MS_78.A.15_60v.jpg }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web | title = Ein new Kůnstliches Fechtbuch im Rappier - Figure 88 | author = Michael Hundt | work = wiktenauer.com | date = 1611 | access-date = 2016-02-01 | url = http://wiktenauer.com/File:Hundt_088.jpg }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web | title = New Kůnstliches Fechtbuch - Page 108 | author = Jakob Sutor von Baden | work = wiktenauer.com | date = 1612 | access-date = 2016-02-01 | url = http://wiktenauer.com/File:Sutor_108.jpg }}</ref> | |||

| ⚫ | == |

||

| == The military flail == | |||

| The martial flail began as a variant of the normal agricultural ]. The term "flail" was given first to a ] implement used to separate ] from ]. This was normally a block of wood attached to a handle with either ] or ]. It was probably farmers called up for military service or peasant rebels who discovered its usefulness as a weapon. A few added spikes made the flail even more dangerous. The ] fielded large numbers of peasant soldiers with flails. | |||

| {{Redirect|Mace and chain|the secret society|Mace and Chain}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{CSS image crop|Image = Piero_della_Francesca_021.jpg|bSize = 1000|cWidth = 140|cHeight = 100|oTop = 190|oLeft = 200|Location = left|Description =Detail from ], painted by ] circa 1452, showing a short flail with three spherical striking ends}} | |||

| ] painting, 1520–1534]] | |||

| The other type of European flail is a shorter weapon consisting of a wooden ] connected by a chain, rope, or leather to one or more striking ends. The ''kisten'', with a spiked or non-spiked head and a leather or rope connection to the haft, is attested in the 10th century in the territories of the ], probably being adopted from either the ] or ]. This weapon spread into Central and Eastern Europe in the 11th–13th centuries,<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Kotowicz |first1=Piotr N. |year=2008 |title=Early medieval war-flails (kistens) from Polish lands|journal=Fasciculi Archaeologiae Historicae |volume=XXI |pages=75–86 |url=http://rcin.org.pl/Content/22894/WA308_34875_PIII348_EARLY-MEDIEVAL_I.pdf}}</ref> and then further west in Western Europe during the 12th and 13th centuries.<ref name=afh>{{Cite journal |last=Holdsworth |first=Alistair F. |date=March 2024 |title=Fantastic Flails and Where to Find Them: The Body of Evidence for the Existence of Flails in the Early and High Medieval Eras in Western, Central, and Southern Europe |url=https://www.mdpi.com/2409-9252/4/1/9 |journal=Histories |language=en |volume=4 |issue=1 |pages=144–203 |doi=10.3390/histories4010009 |issn=2409-9252 |doi-access=free}}</ref> The medieval military flail ({{lang|fr|fléau d'armes}} in French and {{lang|de|Kriegsflegel}} in German), then, might typically have consisted of a wooden shaft joined by a length of chain to one or more iron-shod wooden bars,<ref name=cowper1906>{{cite book | first=Henry Swainson | last=Cowper | year=1906 | title=The art of attack: Being a study in the development of weapons and appliances of offence, from the earliest times to the age of gunpowder | url=https://archive.org/details/artattack00cowpgoog | page=https://archive.org/details/artattack00cowpgoog/page/n106 80] | publisher=W. Holmes, ltd., Printers | location=Ulverston }}</ref> or it may have been a {{lang|de|Kettenmorgenstern}} ("chain morning star") with one or more metal balls or ] in the place of the wooden bars.<ref name="DeVries 2012">{{cite book | last=DeVries | first=Kelly | title=Medieval military technology | publisher=University of Toronto Press | location=North York, Ont. Tonawanda, N.Y | year=2012 | isbn=978-1-4426-0497-1 | page=30}}</ref> Artwork from the 15th century to the early 17th century shows most of these weapons having handles longer than 3 ft and being wielded with two hands, but a few are shown used in a single hand or with a haft too short to be used two-handed. | |||

| Later, special military flails were made, such as the iconic short stick with the chain and spiked metal ball. A ''mace and chain'' is a type of ] weapon, most commonly used during the ]. It consists of a mace or morning star, only with the handle replaced by a chain, which itself connects to a shorter handle. Soldiers using a mace and chain grasped this short handle with either one or two hands, and swung the weapon at the enemy in battle. Soldiers could swing the mace in a circle to gain momentum, before releasing it on the enemy. This would inflict the maximum damage possible on an enemy. | |||

| Despite being very common in fictional works such as cartoons, films and role-playing games as a "quintessential medieval weapon", historical information about flails other than the kisten or derivatives of the peasant flail is rarer than other contemporary weapons, but a notable body of visual and textual sources for Western, Central, and Southern European depictions and descriptions of military are extant, if not particularly easy to find.<ref name=afh/> Some doubt they were used as weapons at all due to the scarcity of genuine specimens as well as the unrealistic way they are depicted in art, as well as the number of pieces in museums that turned out to be 19th century forgeries when analyzed,<ref name="Sturtevant">{{Cite web | title = The Curious Case of the Weapon that Didn't Exist | author = Dr. Paul B. Sturtevant | work = The Public Medievalist | date = May 12, 2016 | access-date = 2016-06-01 | url = http://www.publicmedievalist.com/curious-case-weapon-didnt-exist/ }}</ref><ref name="DeVries 2007">{{cite book | last=DeVries | first=Kelly | title=Medieval weapons an illustrated history of their impact | url=https://archive.org/details/medievalweaponsi00smit_048 | url-access=limited | publisher=ABC-CLIO | location=Santa Barbara, Calif | year=2007 | isbn=978-1-85109-526-1 | page=}}</ref><ref name="MetFlails">"Military Flail" catalog descriptions (, , ; see especially "Date" field) at the ]. Accessed 2015-02-24.</ref> though these limited and somewhat sensationlist studies have now been largely debunked.<ref name=afh/> Waldman (2005) documented several likely authentic examples of the ball-and-chain flail from private collections as well as several restored illustrations from German, French, and Czech sources.<ref name="Waldman 2005">{{cite book | last=Waldman | first=John | title=Hafted weapons in medieval and Renaissance Europe the evolution of European staff weapons between 1200 and 1650 | url=https://archive.org/details/haftedweaponsmed00wald | url-access=limited | publisher=Brill | location=Boston | year=2005 | isbn=90-04-14409-9 | pages=–150}}</ref> Even the more comprehensive scholarly articles collating the numerous sources for flails note that their use in warfare was likely rare at best, even if such weapons were known about as a concept.<ref name=afh/> Flails are noted as being potentially hazardous to their user in the absence of appropriate training and experience,<ref name="DeVries 2007"/> meaning that, even if a blow were struck, there may have been a long time before the user could ready another swing.<ref name="Waldman 2005"/> | |||

| == Other characteristics of the flail == | |||

| ⚫ | == Variations outside Europe == | ||

| * Unlike a sword or mace, it doesn't transfer vibrations from the impact to the wielder. This is a great advantage to a horseman, who can use his horse's speed to add momentum to an underarmed swing of the ball, but runs less of a risk of being unbalanced from his saddle. | |||

| * It is difficult to block with a shield or parry with a weapon because it can curve over and around shields or armor. | |||

| * The flail needs space to swing and can easily endanger the wielder's comrades. | |||

| * Controlling the flail is much more difficult than rigid weapons. | |||

| * If the flail was swung with enough force it could crack open plate armour and stun the wearer. | |||

| In Asia, short flails originally employed in threshing rice were adapted into weapons such as the ] or ]. In China, a very similar weapon to the long-handled peasant flail is known as the ], and Korea has a weapon called a ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://kin.naver.com/open100/detail.nhn?d1id=6&dirId=60402&docId=1029328&qb=7Y646rOk&enc=utf8§ion=kin&rank=3&search_sort=0&spq=0&pid=g/wsPU5Y7udssbHM7psssc--088702&sid=T-v9whfw@08AAFsPC-c |title=네이버 지식iN :: 지식과 내가 함께 커가는 곳 |publisher=Kin.naver.com |access-date=2012-12-18}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://100.naver.com/100.nhn?docid=181414 |title=네이버 지식백과 |publisher=100.naver.com |access-date=2012-12-18}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://dvdprime.donga.com/bbs/view.asp?bbslist_id=1511545&master_id=40 |title=VOTE! |publisher=Dvdprime.donga.com |date=2009-05-08 |access-date=2012-12-18 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140118014853/http://dvdprime.donga.com/bbs/view.asp?bbslist_id=1511545&master_id=40 |archive-date=2014-01-18 }}</ref> In Japan, there is also a version of the smaller ball-on-a-chain flail called a ]. | |||

| ⚫ | == Variations == | ||

| In the 18th and 19th centuries, the long-handled flail is found in use in India. An example held in the ] has a wooden ball-shaped head studded with iron spikes. Another in the ] collection has two spiked iron balls attached by separate chains. | |||

| A variation of the flail is a handle with several chains attached to it rather than one, none of which have a spiked metal ball at their ends.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} | |||

| The ], a whip or scourge formerly used in Russia for the punishment of criminals, was the descendant of the flail. It was manufactured in many forms, and its effect was so severe that few of those who were subjected to its full force survived the punishment. The ] substituted a milder whip for the knout.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|last=Sargeaunt|first=Bertram Edward|title=Weapons, a brief discourse on hand-weapons other than fire-arms|publisher=London, H. Rees|year=1908|isbn=|location=|pages=11}}</ref> | |||

| The flail was not just a European weapon. Examples existed in ] and many other countries. In southeast Asia, lighter flail weapons such as the ] or ] were more common. | |||

| {{weapon-stub}} | |||

| == |

==Gallery== | ||

| {{gallery | |||

| ⚫ | *] | ||

| |File:Topuz,savaş topuzu.jpg|a representative ] flail (replica) | |||

| ⚫ | *] | ||

| |File:Friezen_vallen_de_toren_van_Damiate_aan.jpg|Hayo van Wolvega attacks the tower of Damietta with a flail during the 5th crusade | |||

| *] | |||

| |File:Cep bojowy 0211.jpg|A two-handed flail with metal studs | |||

| |File:DisasterOfMari1266.JPG|Detail from ], circa 1410, showing an armored "Mamluk" with a short, spiked flail tucked into his belt | |||

| |File:FR_2810_Folio_253r_{{Not a typo|mini|ture}}.jpg|Detail from ], circa 1410, showing a horseman using a spiked flail with both hands to strike an adversary. | |||

| |File:MS.1360 Bellifortis of Konrad Kyeser Folio 025v.jpg|Illustration from ] showing a mounted knight with a short flail, circa 1450. | |||

| |Image:Jan Žižka v čele vojsk.gif|Hussite troops with flails on the march | |||

| }} | |||

| ⚫ | == See also == | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| == References == | |||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| == External links == | |||

| {{Commons category|Flails (warfare)|Flail weapons}} | |||

| {{EB1911 poster|Flail}} | |||

| * | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Flail (Weapon)}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Jamie willey baker is a but munch and loves to eat bum curry. | |||

Latest revision as of 06:20, 21 December 2024

Weapon consisting of a striking head flexibly attached to a handle This article is about the weapon. For other uses, see Flail (disambiguation).

A flail is a weapon consisting of a striking head attached to a handle by a flexible rope, strap, or chain. The chief tactical virtue of the flail is its capacity to strike around a defender's shield or parry. Its chief liability is a lack of precision and the difficulty of using it in close combat, or closely-ranked formations.

There are two broad types of flail: a long, two-handed infantry weapon with a cylindrical head, and a shorter weapon with a round metal striking head. The longer cylindrical-headed flail is a hand weapon derived from the agricultural tool of the same name, commonly used in threshing. It was primarily considered a peasant's weapon, and while not common, they were deployed in Germany and Central Europe in the later Late Middle Ages. The smaller, more spherical-headed flail appears to be even less common; it appears occasionally in artwork from the 15th century onward, but many historians have expressed doubts that it ever saw use as an actual military weapon.

The peasant flail

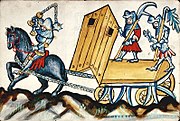

In the Late Middle Ages, a particular type of flail appears in several works being used as a weapon, which consists of a very long shaft with a hinged, roughly cylindrical striking end. In most cases, these are two-handed agricultural flails, which were sometimes employed as an improvised weapon by peasant armies conscripted into military service or engaged in popular uprisings. For example, in the 1420–1497 period, the Hussites fielded large numbers of peasant foot soldiers armed with this type of flail.

Some of these weapons featured anti personnel studs or spikes embedded in the striking end, or are shown being used by armored knights, suggesting they were made or at least modified specifically to be used as weapons. Such modified flails were used in the German Peasants' War in the early 16th century. Several German martial arts manuals or Fechtbücher from the 15th, 16th and 17th century feature illustrations and lessons on how to use the peasant flail (with or without spikes) or how to defend against it when attacked.

The military flail

"Mace and chain" redirects here. For the secret society, see Mace and Chain.

Detail from Battle between Heraclius and Chosroes, painted by Piero della Francesca circa 1452, showing a short flail with three spherical striking ends

Detail from Battle between Heraclius and Chosroes, painted by Piero della Francesca circa 1452, showing a short flail with three spherical striking ends

The other type of European flail is a shorter weapon consisting of a wooden haft connected by a chain, rope, or leather to one or more striking ends. The kisten, with a spiked or non-spiked head and a leather or rope connection to the haft, is attested in the 10th century in the territories of the Rus', probably being adopted from either the Avars or Khazars. This weapon spread into Central and Eastern Europe in the 11th–13th centuries, and then further west in Western Europe during the 12th and 13th centuries. The medieval military flail (fléau d'armes in French and Kriegsflegel in German), then, might typically have consisted of a wooden shaft joined by a length of chain to one or more iron-shod wooden bars, or it may have been a Kettenmorgenstern ("chain morning star") with one or more metal balls or morning star in the place of the wooden bars. Artwork from the 15th century to the early 17th century shows most of these weapons having handles longer than 3 ft and being wielded with two hands, but a few are shown used in a single hand or with a haft too short to be used two-handed.

Despite being very common in fictional works such as cartoons, films and role-playing games as a "quintessential medieval weapon", historical information about flails other than the kisten or derivatives of the peasant flail is rarer than other contemporary weapons, but a notable body of visual and textual sources for Western, Central, and Southern European depictions and descriptions of military are extant, if not particularly easy to find. Some doubt they were used as weapons at all due to the scarcity of genuine specimens as well as the unrealistic way they are depicted in art, as well as the number of pieces in museums that turned out to be 19th century forgeries when analyzed, though these limited and somewhat sensationlist studies have now been largely debunked. Waldman (2005) documented several likely authentic examples of the ball-and-chain flail from private collections as well as several restored illustrations from German, French, and Czech sources. Even the more comprehensive scholarly articles collating the numerous sources for flails note that their use in warfare was likely rare at best, even if such weapons were known about as a concept. Flails are noted as being potentially hazardous to their user in the absence of appropriate training and experience, meaning that, even if a blow were struck, there may have been a long time before the user could ready another swing.

Variations outside Europe

In Asia, short flails originally employed in threshing rice were adapted into weapons such as the nunchaku or three-section staff. In China, a very similar weapon to the long-handled peasant flail is known as the two-section staff, and Korea has a weapon called a pyeongon. In Japan, there is also a version of the smaller ball-on-a-chain flail called a chigiriki.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the long-handled flail is found in use in India. An example held in the Pitt Rivers Museum has a wooden ball-shaped head studded with iron spikes. Another in the Royal Armouries collection has two spiked iron balls attached by separate chains.

The knout, a whip or scourge formerly used in Russia for the punishment of criminals, was the descendant of the flail. It was manufactured in many forms, and its effect was so severe that few of those who were subjected to its full force survived the punishment. The Emperor Nicholas I substituted a milder whip for the knout.

Gallery

-

a representative Ottoman flail (replica)

a representative Ottoman flail (replica)

-

Hayo van Wolvega attacks the tower of Damietta with a flail during the 5th crusade

Hayo van Wolvega attacks the tower of Damietta with a flail during the 5th crusade

-

A two-handed flail with metal studs

A two-handed flail with metal studs

-

Detail from The Travels of Marco Polo, circa 1410, showing an armored "Mamluk" with a short, spiked flail tucked into his belt

-

Detail from The Travels of Marco Polo, circa 1410, showing a horseman using a spiked flail with both hands to strike an adversary.

Detail from The Travels of Marco Polo, circa 1410, showing a horseman using a spiked flail with both hands to strike an adversary.

-

Illustration from Bellifortis showing a mounted knight with a short flail, circa 1450.

Illustration from Bellifortis showing a mounted knight with a short flail, circa 1450.

-

Hussite troops with flails on the march

Hussite troops with flails on the march

See also

References

- ^ Eduard Wagner; Zoroslava Drobná; Jan Durdík (5 May 2014). Medieval Costume, Armour and Weapons. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-32025-0.

- Stephen Turnbull: The Hussite Wars 1419-36, Osprey MAA 409,2004

- media:344Wagenburg der Hussiten.jpg media:Hussites massacre.jpg

- Maximilian I. "Colored plate depicting knights fighting with two-handed flails". Freydal. Archived from the original on 2007-07-02. Retrieved 2016-01-19.

- Douglas Miller : Armies of the German Peasant's War 1524-26,Osprey MAA 384,2003

- media:German Peasants War.jpg

- Hans Talhoffer (c. 1450s). "Talhoffer Fechtbuch (MS 78.A.15) Folio 60r". wiktenauer.com. Retrieved 2016-02-01.

- Hans Talhoffer (c. 1450s). "Talhoffer Fechtbuch (MS 78.A.15) Folio 60v". wiktenauer.com. Retrieved 2016-02-01.

- Michael Hundt (1611). "Ein new Kůnstliches Fechtbuch im Rappier - Figure 88". wiktenauer.com. Retrieved 2016-02-01.

- Jakob Sutor von Baden (1612). "New Kůnstliches Fechtbuch - Page 108". wiktenauer.com. Retrieved 2016-02-01.

- Kotowicz, Piotr N. (2008). "Early medieval war-flails (kistens) from Polish lands" (PDF). Fasciculi Archaeologiae Historicae. XXI: 75–86.

- ^ Holdsworth, Alistair F. (March 2024). "Fantastic Flails and Where to Find Them: The Body of Evidence for the Existence of Flails in the Early and High Medieval Eras in Western, Central, and Southern Europe". Histories. 4 (1): 144–203. doi:10.3390/histories4010009. ISSN 2409-9252.

- Cowper, Henry Swainson (1906). The art of attack: Being a study in the development of weapons and appliances of offence, from the earliest times to the age of gunpowder. Ulverston: W. Holmes, ltd., Printers. p. https://archive.org/details/artattack00cowpgoog/page/n106 80].

- DeVries, Kelly (2012). Medieval military technology. North York, Ont. Tonawanda, N.Y: University of Toronto Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-4426-0497-1.

- Dr. Paul B. Sturtevant (May 12, 2016). "The Curious Case of the Weapon that Didn't Exist". The Public Medievalist. Retrieved 2016-06-01.

- ^ DeVries, Kelly (2007). Medieval weapons an illustrated history of their impact. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO. p. 133. ISBN 978-1-85109-526-1.

- "Military Flail" catalog descriptions (, , ; see especially "Date" field) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed 2015-02-24.

- ^ Waldman, John (2005). Hafted weapons in medieval and Renaissance Europe the evolution of European staff weapons between 1200 and 1650. Boston: Brill. pp. 145–150. ISBN 90-04-14409-9.

- "네이버 지식iN :: 지식과 내가 함께 커가는 곳". Kin.naver.com. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- "네이버 지식백과". 100.naver.com. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- "VOTE!". Dvdprime.donga.com. 2009-05-08. Archived from the original on 2014-01-18. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- Sargeaunt, Bertram Edward (1908). Weapons, a brief discourse on hand-weapons other than fire-arms. London, H. Rees. p. 11.