| Revision as of 01:10, 16 April 2008 edit24.185.110.186 (talk) →Older SAE← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 05:00, 21 December 2024 edit undo100.36.148.201 (talk)No edit summaryTag: Visual edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Varieties of English spoken in the Southern United States}} | |||

| {{Refimprove|date=November 2007}} | |||

| {{About|English as spoken in the Southern United States|older English dialects spoken in this same region|Older Southern American English|English as spoken in South America|South American English}} | |||

| '''Southern American English''' is a group of ]s of the ] spoken throughout the ] of the ], from Southern and Eastern ], ] and ] to the ], and from the ] coast to throughout most of ]. | |||

| {{Infobox language | |||

| | name = Southern American English | |||

| | altname = Southern U.S. English | |||

| | region = ] | |||

| | familycolor = Indo-European | |||

| | fam2 = ] | |||

| | fam3 = ] | |||

| | fam4 = ] | |||

| | fam5 = ] | |||

| | fam6 = ] | |||

| | fam7 = ] | |||

| | fam8 = ] | |||

| | fam9 = ] | |||

| | ancestor = ] | |||

| | ancestor2 = ] | |||

| | ancestor3 = ] | |||

| | ancestor4 = ], ] | |||

| | notice = IPA | |||

| | glotto = sout3302 | |||

| | glottorefname = Southern American English | |||

| | glottofoot = no | |||

| | script = ] (]) | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Southern American English''' or '''Southern U.S. English''' is a ]{{sfnp|Clopper|Pisoni|2006|p=?}}{{sfnp|Labov|1998|p=?}} or collection of dialects of ] spoken throughout the ], primarily by ] and increasingly concentrated in more ]s.{{sfnp|Thomas|2007|p=3}} As of ] research, its ] accents include southern ] and certain ].{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|pp=126, 131}} Such research has described Southern American English as the largest ] by number of speakers.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.pbs.org/speak/ahead/|title=Do You Speak American: What Lies Ahead|access-date=2007-08-15|publisher=PBS|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070703010201/https://www.pbs.org/speak/ahead/|archive-date=2007-07-03|url-status=live }}</ref> More formal terms then developed to characterize this dialect within American linguistics include "Southern White ] English" and "Rural White Southern English".{{sfnp|Thomas|2007|p=453}}{{sfnp|Thomas|2004|p=?}} However, more commonly in the ], the variety is known as the '''Southern accent''' or simply '''Southern'''.{{sfnp|Schneider|2003|p=35}}<ref>{{cite web|title=Southern|year=2014|work=Dictionary.com|publisher=Dictionary.com, based on Random House, Inc.|postscript=|url=https://www.dictionary.com/browse/southern}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Southern|year=2014|work=Merriam-Webster|publisher=Merriam-Webster, Inc.|postscript=|url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/southern}}</ref> | |||

| {{listen|filename=George W. Bush's weekly radio address (November 1, 2008).oga|type=speech|title=Speech example|description=An example of a ]-raised male with a rhotic accent (]).}} | |||

| The Southern dialects make up the largest accent group in the United States.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.pbs.org/speak/ahead/|title=Do You Speak American: What Lies Ahead|accessdate=2007-08-15|publisher=}}</ref> Southern American English can be divided into different sub-dialects, with speech differing between regions. ] (AAVE) shares similarities with Southern dialect due to ]s' strong historical ties to the region. | |||

| {{listen|filename=Response to the Lewinsky Allegations (1-26-98, WJC).ogg|type=speech|title=Speech example|description=An example of an ] male with a rhotic accent (]).}} | |||

| {{listen|filename=Jimmy Carter speaks on the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.ogg|type=speech|title=Speech example|description=An example of a ] male with a non-rhotic accent (]).}} | |||

| ==History== | |||

| }} before ]s (Labov, Ash, and Boberg 2006:126).]] | |||

| A diversity of ] once existed: a consequence of the mix of English speakers from the ] (including largely ] and ]) who migrated to the American South in the 17th and 18th centuries, with particular 19th-century elements also borrowed from the London upper class and enslaved African-Americans. By the 19th century, this included distinct dialects in eastern Virginia, the greater Lowcountry area surrounding Charleston, the Appalachian upcountry region, the Black Belt plantation region, and secluded Atlantic coastal and island communities. | |||

| == Overview of Southern dialects == | |||

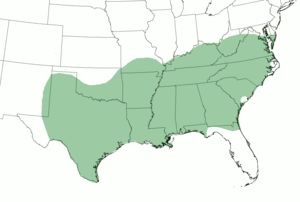

| The range of Southern dialects collectively known as Southern American English stretches across the states which seceded to form the ] during the ], and into those bordering them. | |||

| Following the ], as the South's economy and migration patterns fundamentally transformed, so did Southern dialect trends.{{sfnp|Thomas|2004|p=303}} Over the next few decades, Southerners moved increasingly to Appalachian mill towns, to Texan farms, or out of the South entirely.{{sfnp|Thomas|2004|p=303}} The main result, further intensified by later upheavals such as the ], the ] and perhaps ], is that a newer and more unified form of Southern American English consolidated, beginning around the last quarter of the 19th century, radiating outward from Texas and Appalachia through all the traditional Southern States until around World War II.{{sfnp|Tillery|Bailey|2004|p=329}}{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|p=241}} This newer Southern dialect largely superseded the older and more diverse local Southern dialects, though it became quickly stigmatized in American popular culture. As a result, since around the 1950s and 1960s, the notable features of this newer Southern accent have been in a gradual decline, particularly among younger and more urban Southerners, though less so among rural white Southerners. | |||

| This linguistic region includes ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ], as well as most of ], ], and ]. It also takes in southern and eastern ], southern ], ] areas of ], and the ]. (Labov, Ash, and Boberg 2006). | |||

| ==Geography== | |||

| There are also small and/or isolated places in ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and the ] of California where the prevailing dialect is Southern in character or heavily Southern-influenced, due to historical settlement by Southerners{{Fact|date=November 2007}}. Also, the speech patterns of most of the southernmost counties of ], ], and ] – settled by Southerners and Southern Appalachians - have a predominately Southern influence rather than ]{{Fact|date=November 2007}}. | |||

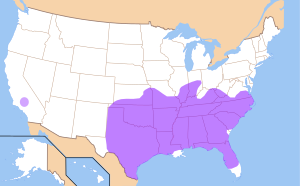

| ]''. The darkest color indicates cities with the most Southern accent features, and the lightest indicates those with the fewest.{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|p=131}}<ref name="ling.upenn.edu">{{cite web |url=http://www.ling.upenn.edu/phono_atlas/NationalMap/NatMap1.html |title=Map |website=ling.upenn.edu |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120830154327/https://www.ling.upenn.edu/phono_atlas/NationalMap/NatMap1.html |archive-date=August 30, 2012 |url-status=live}}</ref>]] | |||

| Despite the slow decline of the modern Southern accent,<ref name = "Dodsworth"/> it is still documented as widespread as of the 2006 '']''. Specifically, the ''Atlas'' documents a Southern accent in urban areas of ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] (alongside ] and ]), and ]; many areas of ]; the ] of northern ]; the ] of southern ]; and in some urban speakers in eastern ], southern ], and the ] of ].{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|pp=126, 131, 150}}{{efn|The ''Atlas'' (p. 125) notes that "Southeastern ] is well known to show strong Southern influence in speech patterns". However, some maps in the ''Atlas'' do not formally document such speech patterns due to the region having no urban areas populated enough to be considered.}} Other 21st-century scholarship further includes within this dialect region southern ], eastern and southern ], the rest of central and northern ] and southern ], and southeastern ].<ref name="Thomas2008">{{cite book |chapter-url=https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9783110208405.1.87/html|doi=10.1515/9783110208405.1.87 |chapter=Rural Southern white accents |title=The Americas and the Caribbean |year=2008 |last1=Thomas |first1=Erik R. |page=285 |isbn=978-3-11-019636-8 }}</ref><ref>Brumbaugh, Susan; Koops, Christian (2017). "Vowel Variation in Albuquerque, New Mexico". Publication of the American Dialect Society, 102(1), 31-57. p.34.</ref> Although the ''Atlas'' is a nationwide study that focuses almost exclusively on urban areas, the Southern accent has been increasingly becoming concentrated, for decades, in rural areas (which are often less well-studied).{{sfnp|Thomas|2007|p=3}} | |||

| Furthermore, the ''Atlas'' documents ]s of the U.S. as sharing key features with Southern accents, like ] and resistance to the ], while lacking other defining features like the ].{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|pp=137, 139}} Such shared features extend across all of ] and ], as well as eastern and central ], southern Missouri, southern ], southern ], and southern ].{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|pp=268}}<ref name="Thomas2008"/> | |||

| Southern dialects substantially originated from immigrants from the ] who moved to the South in the 17th and 18th centuries. The South was predominantly settled by immigrants from the ] {{Fact|date=October 2007}} in the southwest of ], the dialects of which have similarities to the Southern US dialects. Settlement also included large numbers of ] from ], ], and from ]. During the migration south and west, the settlers encountered the French immigrants of ] (from which ], ], ], ], ] and western ] originated), and the French accent itself fused into the British and Irish accents. The modern Southern dialects were born. | |||

| Finally, ] across the United States have many common points with Southern accents due to the strong historical ties of ]s to the South. | |||

| ===Phonology=== | |||

| {{IPA notice}} | |||

| Few generalizations can be made about Southern pronunciation as a whole, as there is great variation between regions in the South (see the ] section below for more information) and between older and younger people. Upheavals such as the ], the ] and ] caused mass migrations throughout the United States. | |||

| <!-- Anecdotally, areas like western ], western Maryland, south-central ], central Florida, etc. are Southern-sounding or have significant Southern characteristics. However, since this is not confirmed by the ANAE, please find sources before adding them, or they will be removed. (The ANAE admittedly does not generally focus on rural areas of the country.) --> | |||

| ====Older SAE==== | |||

| ===Exceptions=== | |||

| The following features are characteristic of older SAE: | |||

| The ''Atlas'' notably identifies several ] cities in particular as lacking a Southern accent, either having shifted away from it or having never had it to begin with, such as ] and ]; ] and ]; ]; ] and possibly ]; ], ], ], and possibly ]; and ].{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|pp=131, 135}} Some cities are home to both the Southern accent and other more locally distinct accents—most clearly ]. | |||

| * Unlike ] and ], the English of the coastal ] is historically heavily ]: a prevailing concentration of Scots-Irish settlement in the regional resulted in particular, even geographically inordinate, emphasis on the sound of final /r/ before a consonant or a word boundary (particularly noticeable on "or" and "er" combinations, such as that in the word "Georgia"--which was and is enunciated by natives as ''jOR-juh.'') (However non-rhoticity is frequently, but mistakenly, used in Hollywood movie depictions of southern accents.) Non-rhotic dialects of the East Coast such as those in the northest (], ], etc.) were established by early settlers from England as opposed to the northern regions of the British Isles where heavy rhoticity was and is dominant. (People only get the ''vay-puhs'' in Medford, or Worcester, MA--or the southern third of the British Isles.) | |||

| * All vowel sounds are started with a subtle prevailing short "a" sound. | |||

| * The distinction between the vowels sounds of words like ] or ''talk'' and ''tock'' is mainly preserved. In much of the Deep South, the vowel found in words like ''talk'' and ''caught'' has developed into a diphthong, so that it sounds like the diphthong used in the word ''loud'' in the Northern United States. | |||

| * The ], as in ''horse'' and ''hoarse'', ''for'' and ''four'' etc., is preserved. | |||

| * The ] has not occurred, and these two words are pronounced with {{IPA|/w/}} and {{IPA|/hw/}} respectively. | |||

| * Lack of ], thus pairs like ''do''/''due'' and ''loot''/''lute'' are distinct. Historically, words like ''due'', ''lute'', and ''new'' contained {{IPA|/juː/}} (as ] does), but Labov, Ash, and Boberg (2006: 53-54) report that the only Southern speakers today who make a distinction use a diphthong {{IPA|/ɪu/}} in such words. They further report that speakers with the distinction are found primarily in ] and northwest ], and in a corridor extending from ] to ]. | |||

| * The ] in ''marry'', ''merry'', and ''Mary'' may be preserved by older speakers, but fewer young people make a distinction. The ''r''-sound becomes almost a vowel, and may be elided after a long vowel, as it often is in AAVE. | |||

| == |

==Modern phonology== | ||

| {| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center" | |||

| The following phenomena are relatively wide spread in Newer SAE, though degree of features may differ between different regions and between rural and urban areas. The older the speaker the less likely he or she is to have these features: | |||

| |+ class="nowrap" | A list of typical Southern vowels{{sfnp|Thomas|2004|pp=301–2}}<ref>{{cite web|title=Accents of English from Around the World|editor=Heggarty, Paul |display-editors=etal |publisher=University of Edinburgh|year=2013|url=http://www.lel.ed.ac.uk/research/gsound/}}</ref> | |||

| ! ] | |||

| ! Southern ] | |||

| ! Example words | |||

| |- | |||

| ! colspan="3" | '''Pure vowels (]s)''' | |||

| |- | |||

| | rowspan="2" | {{IPAc-en|æ}} | |||

| | {{IPA|}} | |||

| | '''a'''ct, p'''a'''l, tr'''a'''p | |||

| |- | |||

| | |cat=no}}]] | |||

| | h'''a'''m, l'''a'''nd, y'''eah''' | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{IPAc-en|ɑː}} | |||

| | rowspan="2" |{{IPA|}} | |||

| | rowspan="2" | bl'''ah''', l'''a'''va, f'''a'''ther, <br/>b'''o'''ther, l'''o'''t, t'''o'''p | |||

| |- | |||

| |{{IPAc-en|ɒ}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{IPAc-en|ɔː}} | |||

| | {{IPA|}} (]: {{IPA|}}) | |||

| | '''o'''ff, l'''o'''ss, d'''o'''g,<br>'''a'''ll, b'''ough'''t, s'''aw''' | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{IPAc-en|ə}} | |||

| | {{IPA|}} | |||

| | '''a'''bout, syr'''u'''p, '''a'''ren'''a''' | |||

| |- | |||

| | rowspan="2" | {{IPAc-en|ɛ}} | |||

| | {{IPA|}} | |||

| | dr'''e'''ss, m'''e'''t, br'''ea'''d | |||

| |- | |||

| | rowspan="2" | {{IPA|}}{{efn|{{IPAc-en|ɛ}} and {{IPAc-en|ɪ}} are merged before nasal consanants due to the ].}} | |||

| | rowspan="2" | p'''e'''n, g'''e'''m, t'''e'''nt,<br>p'''i'''n, h'''i'''t, t'''i'''p | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{IPAc-en|ɪ}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{IPAc-en|iː}} | |||

| | {{IPA|}} | |||

| | b'''ea'''m, ch'''i'''c, fl'''ee'''t | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{IPAc-en|ʌ}} | |||

| | {{IPA|}} | |||

| | b'''u'''s, fl'''oo'''d, wh'''a'''t | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{IPAc-en|ʊ}} | |||

| | {{IPA|}} | |||

| | b'''oo'''k, p'''u'''t, sh'''ou'''ld | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{IPAc-en|uː}} | |||

| | {{IPA|}} | |||

| | f'''oo'''d, gl'''ue''', n'''ew''' | |||

| |- | |||

| ! colspan="3" | ]s | |||

| |- | |||

| | rowspan="2" |{{IPAc-en|aɪ}} | |||

| | {{IPA|}} | |||

| | r'''i'''de, sh'''i'''ne, tr'''y''' | |||

| |- | |||

| | |cat=no}})]] | |||

| | br'''igh'''t, d'''i'''ce, ps'''y'''ch | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{IPAc-en|aʊ}} | |||

| | {{IPA|}} | |||

| | n'''ow''', '''ou'''ch, sc'''ou'''t | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{IPAc-en|eɪ}} | |||

| | {{IPA|}} | |||

| | l'''a'''ke, p'''ai'''d, r'''ei'''n | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{IPAc-en|ɔɪ}} | |||

| | {{IPA|}} | |||

| | b'''oy''', ch'''oi'''ce, m'''oi'''st | |||

| |- | |||

| | rowspan="2" | {{IPAc-en|əʊ}} | |||

| | {{IPA|}} | |||

| | g'''oa'''t, r'''oa'''d, m'''o'''st | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{IPA|}}{{efn|preceding {{IPA|/l/}} or a ]}} | |||

| | g'''oa'''l, b'''o'''ld, sh'''ow'''ing | |||

| |- | |||

| ! colspan="3" | ]s | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{IPAc-en|ɑːr}} | |||

| | ]: {{IPA|}} <br/>non-rhotic Southern dialects: {{IPA|}} | |||

| | b'''ar'''n, c'''ar''', p'''ar'''k | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{IPAc-en|ɛər}} | |||

| | rhotic: {{IPA|}} <br/>non-rhotic: {{IPA|}} | |||

| | b'''are''', b'''ear''', th'''ere''' | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{IPAc-en|ɜːr}} | |||

| | {{IPA|}} (]: {{IPA|}}) | |||

| | b'''ur'''n, f'''ir'''st, h'''er'''d | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{IPAc-en|ər}} | |||

| | rhotic: {{IPA|}}<br/>non-rhotic: {{IPA|}} | |||

| | bett'''er''', mart'''yr''', doct'''or''' | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{IPAc-en|ɪər}} | |||

| | rhotic: {{IPA|}} <br/>non-rhotic: {{IPA|}} | |||

| | f'''ear''', p'''eer''', t'''ier''' | |||

| |- | |||

| | rowspan="2" | {{IPAc-en|ɔːr}} | |||

| | rhotic: {{IPA|}} <br/>non-rhotic: {{IPA|}} | |||

| | h'''or'''se, b'''or'''n, n'''or'''th | |||

| |- | |||

| |rhotic: {{IPA|}} <br />non-rhotic: {{IPA|}} | |||

| |h'''oar'''se, f'''or'''ce, p'''or'''k | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{IPAc-en|ʊər}} | |||

| |rhotic: {{IPA|}} <br />non-rhotic: {{IPA|}} | |||

| |p'''oor''', s'''ure''', t'''our''' | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{IPAc-en|j|ʊər}} | |||

| | rhotic: {{IPA|}} <br/>non-rhotic: {{IPA|}} | |||

| | c'''ure''', '''Eur'''ope, p'''ure''' | |||

| |} | |||

| Most of the Southern United States underwent several major sound changes from the beginning to the middle of the 20th century, during which a more unified, region-wide sound system developed, markedly different from the sound systems of the 19th-century Southern dialects. | |||

| * The ] of {{IPA|}} and {{IPA|}} before ]s, so that ''pen'' and ''pin'' are pronounced the same, but the ] is not found in ], ], or ] (which does not fall within the Southern dialect region). This sound change has spread beyond the South in recent decades and is now found in parts of the ] and ] as well. | |||

| * Lax and tense vowels often ], making pairs like ''feel''/''fill'' and ''fail''/''fell'' ]s for speakers in some areas of the South. Some speakers may distinguish between the two sets of words by reversing the normal vowel sound, e.g., ''feel'' in SAE may sound like ''fill'', and vice versa (Labov, Ash, and Boberg 2006: 69-73). | |||

| The South as a present-day dialect region generally includes all of the pronunciation features below, which are popularly recognized in the United States as making up a "Southern accent". The following phonological phenomena focus on the developing sound system of the 20th-century Southern dialects of the United States that altogether largely (though certainly not entirely) superseded the ] regional patterns. However, there is still variation in Southern speech regarding potential differences based on factors like a speaker's exact sub-region, age, ethnicity, etc. | |||

| ====Shared features==== | |||

| *{{anchor|Southern Vowel Shift}}Southern Vowel Shift (sometimes simply called the Southern Shift): A ] regarding vowels is fully completed, or occurring, in most Southern dialects, especially 20th-century ones, and at the most advanced stage in the "Inland South" (i.e. away from the Gulf and Atlantic Coasts) as well as much of central and northern Texas. This 3-stage chain movement of vowels is first triggered by Stage 1 which dominates the entire Southern region, followed by Stage 2 which covers almost all of that area, and Stage 3 which is concentrated only in speakers of the two aforementioned core sub-regions. Stage 1 (defined below) may have begun in a minority of Southern accents as early as the first half of the 19th century with a glide weakening of {{IPA|/aɪ/}} to {{IPA|}} or {{IPA|}}; however, it was still largely incomplete or absent in the mid-19th century, before expanding rapidly from the last quarter of the 19th into the middle of the 20th century;{{sfnp|Tillery|Bailey|2004|p=332}} today, this glide weakening or even total glide deletion is the pronunciation norm throughout all of the Southern States. | |||

| The following features are also associated with SAE: | |||

| **Stage 1 ({{IPA|/aɪ/}} → {{IPA|}}): | |||

| ***The starting point, or first stage, of the Southern Shift, is the transition of the ] {{IPA|/aɪ/}} ({{Audio|En-us-eye.ogg|<small>listen</small>|help=no}}) toward a ] long vowel {{IPA|}} ({{Audio|open front unrounded vowel.ogg|<small>listen</small>|help=no}}), so that, for example, the word ''ride'' commonly approaches a sound that most other American English speakers would hear as ''rod'' or ''rad''. Stage 1 is now complete for a majority of Southern dialects.{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|p=244}} Southern speakers particularly exhibit the Stage 1 shift at the ends of words and before voiced consonants, but not as commonly before voiceless consonants, where the diphthong instead may retain its glide, so that ''ride'' is {{IPA|}}, but ''right'' is {{IPA|}}. Inland (i.e. non-coastal) Southern speakers, however, indeed delete the glide of {{IPA|/aɪ/}} in all contexts, as in the stereotyped pronunciation "nahs whaht rahss" for ''nice white rice''; these most shift-advanced speakers are largely found today in an Appalachian area that comprises eastern Tennessee, western North Carolina, and northern Alabama, as well as in central Texas.{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|p=245}} Certain traditional East Coast Southern accents do not exhibit this Stage 1 glide deletion,{{sfnp|Thomas|2004|pp=301, 311–312}} particularly in ], as well as Atlanta and Savannah, Georgia (cities that are, at best, considered marginal to the modern Southern dialect region). | |||

| ***Somewhere in "the early stages of the Southern Shift",{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|p=121}} {{IPA|/æ/}} (as in ''trap'' or ''bad'') moves generally higher and fronter in the mouth (often also giving it a complex gliding quality, starting higher and then gliding lower); thus {{IPA|/æ/}} can range variously away from its original position, with variants such as {{IPA|}},{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|p=121}} {{IPA|}}, {{IPA|}}, and possibly even {{IPA|}} for those born between the World Wars.{{sfnp|Thomas|2004|p=305}} An example is that, to other English speakers, the Southern pronunciation of ''yap'' sounds something like ''yeah-up''. See "Southern vowel breaking" below for more information. | |||

| **Stage 2 ({{IPA|/eɪ/}} → {{IPA|}} and {{IPA|/ɛ/}} → {{IPA|}}): | |||

| ***By removing the existence of {{IPA|}}, Stage 1 leaves open a lower space for {{IPA|/eɪ/}} (as in ''name'' and ''day'') to occupy, causing Stage 2: the dragging of the diphthong {{IPA|/eɪ/}} into a lower starting position, towards {{IPA-all|ɛɪ||nl-ei.ogg}} or to a sound even lower or more retracted, or both. | |||

| ***At the same time, the pushing of {{IPA|/æ/}} into the vicinity of {{IPA|/ɛ/}} (as in ''red'' or ''belt''), forces {{IPA|/ɛ/}} itself into a higher and fronter position, occupying the {{IPA|}} area (previously the vicinity of {{IPA|/eɪ/}}). {{IPA|/ɛ/}} also often acquires an in-glide: thus, {{IPA|}}. An example is that, to other English speakers, the Southern pronunciation of ''yep'' sounds something like ''yay-up''. Stage 2 is most common in heavily stressed syllables. Southern accents originating from cities that formerly had the greatest influence and wealth in the South (Richmond, Virginia; Charleston, South Carolina; Atlanta, Macon, and Savannah, Georgia; and all of Florida) do not traditionally participate in Stage 2.{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|p=248}} | |||

| **Stage 3 ({{IPA|/i/}} → {{IPA|}} and {{IPA|/ɪ/}} → {{IPA|}}): By the same pushing and pulling ]s described above, {{IPA|/ɪ/}} (as in ''hit'' or ''lick'') and {{IPA|/i/}} (as in ''beam'' or ''meet'') follow suit by both possibly becoming diphthongs whose nuclei switch positions. {{IPA|/ɪ/}} may be pushed into a diphthong with a raised beginning, {{IPA|}}, while {{IPA|/i/}} may be pulled into a diphthong with a lowered beginning, {{IPA|}}. An example is that, to other English speakers, the Southern pronunciation of ''fin'' sounds something like ''fee-in'', while ''meet'' sounds something like ''mih-eet''. Like the other stages of the Southern shift, Stage 3 is most common in heavily stressed syllables and particularly among Inland Southern speakers.{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|p=248}} | |||

| **Southern vowel breaking ("Southern ]"): All three stages of the Southern Shift appear related to the short front pure vowels being "broken" into gliding vowels, making one-syllable words like ''pet'' and ''pit'' sound as if they might have two syllables (as something like ''pay-it'' and ''pee-it''). This short front vowel gliding phenomenon is popularly recognized as the "Southern drawl". The "short ''a''", "short ''e''", and "short ''i''" vowels are all affected, developing a glide up from their original starting position to {{IPA|}}, and then often back down to a ] vowel: {{IPA|/æ/ → }}; {{IPA|/ɛ/ → }}; and {{IPA|/ɪ/ → }}, respectively. Appearing mostly after the mid-19th century, this phenomenon is on the decline, being most typical of Southern speakers born before 1960.{{sfnp|Thomas|2004|p=305}} | |||

| *Unstressed, word-final {{IPA|/ŋ/}} → {{IPA|}}: The ] {{IPA|/ŋ/}} in an unstressed syllable at the end of a word ] to {{IPA|}}, so that ''singing'' {{IPA|/ˈsɪŋɪŋ/}} is sometimes ] as ''singin'' {{IPA|}}.{{sfnp|Wolfram|2003|p=151}} This is common in vernacular English dialects around the world. | |||

| *Lacking or transitioning cot–caught merger: The historical distinction between the two vowels sounds {{IPA|/ɔ/}} and {{IPA|/ɑ/}}, in words like ''caught'' and ''cot'' or ''stalk'' and ''stock'' is mainly preserved,{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|p=137}} though the exact articulation is distinct from most other English dialects. In much of the South during the 20th century, there was a trend to lower the vowel found in words like ''stalk'' and ''caught'', often with an upglide, so that the most common result is roughly the gliding vowel {{IPA|}}. However, the ] is becoming increasingly common throughout the United States, affecting Southeastern and even some Southern dialects, towards a merged vowel {{IPA|}}.{{sfnp|Thomas|2004|p=309}} In the South, this merger, or a transition towards this merger, is especially documented in central, northern, and (particularly) western Texas.{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|p=61}} | |||

| ] of South Carolina and Georgia. The purple area in California consists of the ] and ] area, where migrants from the ] settled during the ]. There is also debate whether or not ], is an exclusion. Based on {{Harvcoltxt|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|p=68}}.]] | |||

| *]: the vowel phonemes {{IPA|/ɛ/}} and {{IPA|/ɪ/}} now merge before ], so that ''pen'' and ''pin'', for instance, or ''hem'' and ''him'', are pronounced the same, as ''pin'' or ''him'', respectively.{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|p=137}} The merger, which is roughly towards the sound {{IPA|}}, is still unreported among some vestigial ], and other geographically Southern U.S. varieties that have eluded the Southern Vowel Shift, such as the ] of ] or the anomalous dialect of ]. | |||

| *]: The "dropping" of the ''r'' sound ] was historically widespread in the South, particularly in former plantation areas. This phenomenon, non-rhoticity, was considered prestigious before World War II, after which the social perception in the South reversed. Now, full rhoticity (sometimes called ''r''-fulness), in which most or all ''r'' sounds are pronounced, is dominant throughout most of the South, and even "hyper-rhoticity" (articulation of a very distinctive {{IPA|/r/}} sound),{{sfnp|Hayes|2013|p=63}} particularly among younger and female white Southerners. The sound quality of the Southern ''r'' is the "bunch-tongued ''r''", produced by strongly constricting the root or the midsection of the tongue, or both.{{sfnp|Thomas|2004|p=315}} The only major exceptions are among ] speakers and among some south ] and Cajun speakers, who are variably non-rhotic.{{sfnp|Thomas|2004|p=316}} | |||

| * ]: Most of the U.S. has completed the ], but, in many Southern accents, particularly inland Southern accents, the phonemes {{IPA|/w/}} and {{IPA|/hw/}} remain distinct, so that pairs of words like ''wail'' and ''whale'' or ''wield'' and ''wheeled'' are not ]s.{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|p=50}} | |||

| * Lax and tense vowels often ], making pairs like ''feel''/''fill'' and ''fail''/''fell'' ]s for speakers in some areas of the South. Some speakers may distinguish between the two sets of words by reversing the normal vowel sound, e.g., ''feel'' in Southern may sound like ''fill'', and vice versa.{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|pp=69–73}} | |||

| * The back vowel {{IPA|/u/}} (in ''goose'' or ''true'') is ] in the mouth to the vicinity of {{IPA|}} or even farther forward, which is then followed by a slight ]; different gliding qualities have been reported, including both backward and (especially in the eastern half of the South) forward glides.{{sfnp|Thomas|2004|p=310}} | |||

| *{{anchor|GOAT fronting}}The back vowel {{IPA|/oʊ/}} (in ''goat'' or ''toe'') is fronted to the vicinity of {{IPA|}}, and perhaps even as far forward as {{IPA|}}.{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|p=105}} | |||

| ** Certain words ending in unstressed {{IPA|/oʊ/}} (especially with the spelling {{angbr|ow}}) may be pronounced as {{IPA|}} or {{IPA|}},{{sfnp|Wells|1982|p=167}} making ''yellow'' sound like ''yella'' or ''tomorrow'' like ''tomorra''. | |||

| * Back Upglide (Chain) Shift: {{IPA|/aʊ/}} shifts forward and upward to {{IPA|}} (also possibly realized, variously, as {{IPA|}}); thus allowing the back vowel {{IPA|/ɔ/}} to fill an area similar to the former position of /aʊ/ in the mouth, becoming lowered and developing an upglide ; this, in turn, allows (though only for the most advanced Southern speakers) the upgliding {{IPA|/ɔɪ/}}, before {{IPA|/l/}}, to lose its glide {{IPA|}} (for instance, causing the word ''boils'' to sound something like the British or New York City pronunciations of {{Audio|en-uk-balls.ogg|''balls''|help=no}}).{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|p=254}} | |||

| * The vowel {{IPA|/ʌ/}}, as in ''bug, luck, strut,'' etc., is realized as {{IPA|}}, occasionally fronted to {{IPA|}} or raised in the mouth to {{IPA|}}.{{sfnp|Thomas|2004|p=307}} | |||

| * {{IPA|/z/}} becomes {{IPA|}} before {{IPA|/n/}}, for example {{IPA|}} ''wasn't'', {{IPA|}} ''business'',{{sfnp|Wolfram|2003|p=55}} but ''hasn't'' may keep the to avoid merging with ''hadn't''. | |||

| * Many nouns are stressed on the first syllable that is stressed on the second syllable in most other American accents,{{sfnp|Thomas|2004|p=305}} such as ''police'', ''cement'', ''Detroit'', ''Thanksgiving'', ''insurance'', ''behind'', ''display'', ''hotel'', ''motel'', ''recycle'', ''TV'', ''guitar'', ''July'', and ''umbrella''. Today, younger Southerners tend to keep this initial stress only for a more reduced set of words, perhaps including only ''insurance'', ''defense'', ''Thanksgiving'', and ''umbrella''.{{sfnp|Tillery|Bailey|2004|p=331}}<ref name = "Vaux"/> | |||

| *] incidence is sometimes unique in the South, so that:<ref name = "Vaux"/> | |||

| **''Florida'' is typically pronounced {{IPA|/ˈflɑrɪdə/}} (particularly along the East Coast) rather than ] {{IPA|/ˈflɔrɪdə/}}, and ''lawyer'' is {{IPA|/ˈlɔ.jər/}} rather than General American {{IPA|/ˈlɔɪ.ər/}} (i.e., the first syllable of ''lawyer'' sounds like ''law'', not ''loy''). | |||

| **The suffixed, unstressed ''-day'' in words like ''Monday'' and ''Sunday'' is commonly {{IPA|/di/}}. | |||

| * Lacking or incomplete ]: unstressed, word-final {{IPA|/ɪ/}} (the second vowel sound in words like ''happy, money, Chelsea,'' etc.) may continue to be lax, unlike the ] (higher and fronter) vowel {{IPA|}} typical throughout rest of the United States. The South maintains a sound not always tensed: {{IPA|}} or {{IPA|}}.{{sfnp|Wells|1982|p=165}} | |||

| *Variable ]: the merger of the phonemes {{IPA|/ɔr/}} (as in ''morning'') and {{IPA|/oʊr/}} (as in ''mourning'') is common, as in most English dialects, though a distinction is still preserved especially in Southern accents along the Gulf Coast, plus scatterings elsewhere;{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|p=52}} thus, ''morning'' {{IPA|}} versus ''mourning'' {{IPA|}}. | |||

| ===Inland South and Texas=== | |||

| * {{IPA|/z/}} becomes {{IPA|}} before {{IPA|/n/}}, for example {{IPA|}} ''wasn't'', {{IPA|}} ''business'', but ''hasn't'' is sometimes still pronounced {{IPA|}} because there already exists a word ''hadn't'' pronounced {{IPA|}}. | |||

| {{Main|Appalachian English|Texan English}} | |||

| * Many nouns are stressed on the first syllable that would be stressed on the second syllable in other accents. These include ''police'', ''cement'', ''Detroit'', ''Thanksgiving'', ''insurance'', ''behind'', ''display'', ''recycle'', ''TV'', and ''umbrella''. | |||

| ] ] identify the "Inland South" as a large linguistic sub-region of the South located mostly in southern ] (specifically naming the cities of Greenville, South Carolina, Asheville, North Carolina, Knoxville and Chattanooga, Tennessee, and Birmingham and Linden, Alabama), inland from both the Gulf and Atlantic Coasts, and the originating region of the Southern Vowel Shift. The Inland South, along with the "Texas South" (an urban core of central Texas: ], ], ], and ]){{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|pp=126, 131}} are considered the two major locations in which the Southern regional sound system is the most highly developed, and therefore the core areas of the current-day South as a dialect region.{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|pp=148, 150}} | |||

| * The '''Southern Drawl,''' or the diphthongization or triphthongization of the traditional short front vowels as in the words ''pat'', ''pet'', and ''pit'': these develop a glide up from their original starting position to {{IPA|}}, and then in some cases back down to ]. | |||

| :{{IPA|/æ/ → }} | |||

| :{{IPA|/ɛ/ → }} | |||

| :{{IPA|/ɪ/ → }} | |||

| * The '''Southern (Vowel) Shift,''' a chain shift of vowels which is described by Labov as: | |||

| ** As a result of the "drawl" described above, {{IPA|}} moves to become a high front vowel, and {{IPA|}} to become a mid front vowel. In a parallel shift, the nuclei of {{IPA|}} and {{IPA|}} relax and become less front. | |||

| ** The back vowels {{IPA|/u/}} in ''boon'' and {{IPA|/o/}} in ''code'' shift considerably forward. | |||

| ** The open back unrounded vowel {{IPA|/ɑr/}} ''card'' shifts upward towards {{IPA|/ɔ/}} ''board'', which in turn moves up towards the old location of in ''boon''. This particular shift probably does not occur for speakers with the ]. | |||

| ** The ] {{IPA|/aɪ/}} becomes ]ized to {{IPA|}}. Some speakers exhibit this feature at the ends of words and before voiced consonants but not before voiceless consonants; some others in fact exhibit ] before voiceless consonants, so that ''ride'' is {{IPA|}} and ''wide'' is {{IPA|}}, but ''right'' is {{IPA|}} and ''white'' is {{IPA|}}; others monophthongize {{IPA|/aɪ/}} in all contexts. Throughout most of the region, this {{IPA|}} tends to be more front (toward an {{IPA|}}){{Failed verification|date=March 2008}} so that word pairs like ''rod'' (SAE {{IPA|}},{{Failed verification|date=March 2008}} normally pronounced without any noticeable rounding) and ''ride'' (SAE {{IPA|}}) are never confused. | |||

| * The ] in ''furry'' and ''hurry'' is preserved. | |||

| * In some regions of the south, there is a }} and {{IPA|}}]], making ''cord'' and ''card'', ''for'' and ''far'', ''form'' and ''farm'' etc. homonyms. | |||

| * The ] in ''mirror'' and ''nearer'', ''Sirius'' and ''serious'' etc. is not preserved. | |||

| * {{IPA|/i/}} is replaced with {{IPA|/ɛ/}} at the end of a word, so that ''furry'' is pronounced as {{IPA|/fɝrɛ/}} ("furreh") | |||

| * The ] in ''pour'' and ''poor'', ''moor'' and ''more'' is not preserved. | |||

| * The l's in the words ''walk'' and ''talk'' are occasionally pronounced, causing the words ''talk'' and ''walk'' to be pronounced {{IPA|/wɑlk/}} and {{IPA|/tɑlk/}} by some southerners. A sample of that pronunciation can be found at http://www.utexas.edu/courses/linguistics/resources/socioling/talkmap/talk-nc.html. | |||

| The accents of Texas are diverse, for example with important Spanish influences on its vocabulary;<ref>. ]. MacNeil/Lehrer Productions. 2005.</ref> however, much of the state is still an unambiguous region of modern rhotic Southern speech, strongest in the cities of Dallas, Lubbock, Odessa, and San Antonio,{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|pp=126, 131}} which all firmly demonstrate the first stage of the Southern Shift, if not also further stages of the shift.{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|p=69}} Texan cities that are noticeably "non-Southern" dialectally are Abilene and Austin; only marginally Southern are Houston, El Paso, and Corpus Christi.{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|pp=126, 131}} In western and northern Texas, the ] is very close to completed.{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|p=254}} | |||

| ===Grammar=== | |||

| ====Older SAE==== | |||

| ===Distinct phonologies=== | |||

| * Zero plural-second person copula. | |||

| ::You taller than Sheila | |||

| ::They gonna leave today (Cukor-Avila, 2003). | |||

| * Use of the circumfix ''a- . . . -in'.'' | |||

| ::He was ahootin' and ahollerin'.' | |||

| ::The wind was ahowlin'.' | |||

| * The use of ''like to'' to mean something like ''nearly,'' often used in violent situations. | |||

| ::I like to had a heart attack. | |||

| ==== |

====Cajun==== | ||

| {{Main|Cajun English}} | |||

| * Use of the ] '']'' as the second person plural pronoun.<ref>http://cfprod01.imt.uwm.edu/Dept/FLL/linguistics/dialect/staticmaps/q_50.html Harvard Dialect Survey - word use: a group of two or more people.</ref> Its uncombined form — ''you all'' — is used less frequently.<ref>Hazen, Kirk and Fluharty, Ellen. "Linguistic Diversity in the South: changing Codes, Practices and Ideology". Page 59. ]; 1st Edition: 2004. ISBN 0-8203-2586-4</ref> | |||

| Most of southern Louisiana constitutes ], a cultural region dominated for hundreds of years by monolingual speakers of ],{{sfnp|Dubois|Horvath|2004|pp=412–414}} which combines elements of ] with other French and Spanish words. Today, this French dialect is spoken by many older ] ethnic group members and is said to be dying out. A related language, ], also exists. Since the early 1900s, Cajuns additionally began to develop their ], which retains some influences and words from French, such as "cher" (dear) or "nonc" (uncle). This dialect fell out of fashion after World War II but experienced a renewal among primarily male speakers born since the 1970s, who have been the most attracted by, and the biggest attractors of, a successful Cajun cultural renaissance.{{sfnp|Dubois|Horvath|2004|pp=412–414}} The accent includes:{{sfnp|Dubois|Horvath|2004|pp=409–410}} | |||

| :* When speaking about a group, ''y'all'' is general (I know y'all) —as in that group of people is familiar to you and you know them as a whole, whereas ''all y'all'' is much more specific and means you know each and every person in that group, not as a whole, but individually ("I know all y'all.") ''Y'all'' can also be used with the standard "-s" possessive. | |||

| * variable non-rhoticity (or ''r''-dropping) | |||

| ::"''I've got y'all's assignments here.''" | |||

| * high ] (including in vowels before ]s) | |||

| :* ''Y'all'' is distinctly separate from the singular ''you.'' The statement, "''I gave y'all my payment last week,''" is more precise than "''I gave you my payment last week.''" ''You'' (if interpreted as singular) could imply the payment was given directly to the person being spoken to — when that may not be the case. | |||

| * deletion of any word's final consonant(s) (''hand'' becomes {{IPA|}}, ''food'' becomes {{IPA|}}, ''rent'' becomes {{IPA|}}, ''New York'' becomes {{IPA|}}, etc.){{dubious|date=August 2024}} | |||

| * In rural Southern Appalachia ''yernses'' may be substituted for the 2nd person plural possessive ''yours.'' | |||

| * a potential for glide weakening in all gliding vowels; for example, {{IPA|/oʊ/}} (as in ''Joe''), {{IPA|/eɪ/}} (as in ''Jay''), and {{IPA|/ɔɪ/}} (as in ''Joy'') have glides ({{IPA|}}, {{IPA|}}, and {{IPA|}}, respectively) | |||

| ::"''That dog is yernses.''" | |||

| * the ] toward {{IPA|}} | |||

| * Use of ''dove'' as past tense for ''dive'', ''drug'' as past tense for ''drag'', and ''drunk'' as past tense for ''drink''. | |||

| Cajun English is not subject to the Southern Vowel Shift.{{sfn|Reaser|Wilbanks|Wojcik|Wolfram|2018|p=135}} | |||

| ====Shared features==== | |||

| These features are characteristic of both older Southern American English and newer Southern American English. | |||

| ====New Orleans==== | |||

| * Use of ''(a-)fixin' to'' as an indicator of immediate future action. | |||

| {{Main|New Orleans English}} | |||

| ::He's fixin' to eat. | |||

| A separate historical English dialect from the above Cajun one, spoken only by those raised in the ] area, is traditionally non-rhotic and noticeably shares more pronunciation commonalities with a ] than with other Southern accents, due to commercial ties and cultural migration between the two cities. Since at least the 1980s, this local New Orleans dialect has popularly been called "]", from the common local greeting "Where you at?". Some features that the New York accent shares with the Yat accent include:{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|pp=260–1}} | |||

| ::We're a-fixin' to go. | |||

| *variable non-rhoticity | |||

| * Use of double modals (''might could, might should, might would, used to could,'' etc.--also called "modal stacking") and sometimes even triple modals that involve ''oughta'' or a double modal (like ''might should oughta,'' or ''used to could be able to.'') | |||

| *] (so that ''bad'' and ''back'', for example, have different vowels) | |||

| ::I might could climb to the top. | |||

| *{{IPA|/ɔ/}} as high gliding {{IPA|}} | |||

| * Replacement of ''have'' (to possess) with ''got.'' | |||

| *{{IPA|/ɑr/}} as rounded {{IPA|}} | |||

| ::I got one of them. | |||

| *the ] (traditionally, though now in decline). | |||

| * Using ''them'' as a demonstrative adjective replacing ''those'' | |||

| *] of both {{IPA|/aɪ/}} and {{IPA|/aʊ/}} (mainly among younger speakers)<ref>{{Cite journal |url=https://pubs.aip.org/asa/jasa/article/147/1/554/828838/The-rise-of-Canadian-raising-of-au-in-New-Orleans |title=The Rise of Canadian Raising of /au/ in New Orleans English |last=Carmichael |first=Katie |date=January 2020 |access-date=2023-04-26 |journal=The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America|volume=147 |issue=1 |page=554 |doi=10.1121/10.0000553 |pmid=32006992 |bibcode=2020ASAJ..147..554C |hdl=10919/113171 |hdl-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| ::See them birds? | |||

| Yat also lacks the typical vowel changes of the Southern Shift and the ] that is commonly heard elsewhere throughout the South. Yat is associated with the working and lower-middle classes, and a spectrum of speech patterns with fewer notable Yat features is often heard among those of higher socioeconomic status; such New Orleans affluence is associated with the New Orleans Uptown and the ], whose speech patterns are sometimes considered distinct from the lower-class Yat dialect.<ref>{{cite video| people=] (director) | date=1985 | title=Yeah You Rite! | medium=Short documentary film | location=USA | publisher= Center for New American Media | url=https://archive.org/details/YeahYouRite }}</ref> | |||

| * Use of non-standard preterits, Such as ''drowneded'' as the past tense of ''drown'', ''knowed'' as past tense of ''know,'' ''degradated'' as the past tense of ''degrade'', and ''seen'' replacing ''saw'' as past tense of ''see.'' This also includes using ''was'' for ''were,'' or in other words regularizing the past tense of ''be'' to ''was.'' | |||

| ::You was sittin' on that chair. | |||

| ====Other Southern cities==== | |||

| * The inceptive ''get/got to'' (indicating that an action is just getting started). ''Get to'' is more frequent in older SAE, and ''got to'' in newer SAE. | |||

| :''See also: {{section link|#Exceptions}}'' | |||

| ::I got to talking to him and we ended up talking all night. | |||

| * Regularization of negative past tense ''do'' to ''don't,'' or in other words using ''don't'' for ''doesn't.'' | |||

| Some sub-regions of the South, and perhaps even a majority of the biggest cities, are showing a gradual shift away from the Southern accent (toward a more ] or ] accent) since the second half of the 20th century to the present. Such well-studied cities include ], and ]; in Raleigh, for example, this retreat from the accent appears to have begun around 1950.<ref name="Dodsworth">Dodsworth, Robin (2013) , University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: Vol. 19: Iss. 2, Article 5.</ref> | |||

| ::He/she/it/John don't like cake. | |||

| * Existential ''It,'' a feature dating from Middle English which can be explained as substituting ''it'' for ''there'' when ''there'' refers to no physical location, but only to the existence of something. | |||

| Other sub-regions are unique in that their inhabitants have never spoken with the Southern regional accent, instead having their own distinct accents. The 2006 '']'' identifies ], as a dialectal "island of non-Southern speech",{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|p=181}} ], likewise as "not markedly Southern in character", and the traditional local accent of ], as "giving way to regional patterns",{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|p=304}} despite these being three prominent Southern cities. The dialect features of Atlanta are best described today as sporadic from speaker to speaker, with such variation increased due to a huge movement of non-Southerners into the area during the 1990s.{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|pp=260–1}} Modern-day Charleston speakers have leveled in the direction of a more generalized ] (and speakers in other Southern cities too like Greenville, Richmond, and Norfolk),{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|p=135}} away from the city's now-defunct, ], whose features were "diametrically opposed to the Southern Shift... and differ in many other respects from the main body of Southern dialects".{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|pp=259–260}} The Savannah accent is also becoming more Midland-like. The following vowel sounds of Atlanta, Charleston, and Savannah have been unaffected by typical Southern phenomena like the Southern drawl and Southern Vowel Shift:{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|pp=260–1}} | |||

| ::It's one lady that lives in town. | |||

| *{{IPA|/æ/}} as in ''bad'' (the "default" ] nasal short-''a'' system is in use, in which ] only before {{IPA|/n/}} or {{IPA|/m/}}).{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|pp=259–261}} | |||

| *{{IPA|/aɪ/}} as in ''bide'' (however, some Atlanta and Savannah speakers do variably show Southern {{IPA|/aɪ/}} glide weakening). | |||

| *{{IPA|/eɪ/}} as in ''bait''. | |||

| *{{IPA|/ɛ/}} as in ''bed''. | |||

| *{{IPA|/ɪ/}} as in ''bid''. | |||

| *{{IPA|/i/}} as in ''bead''. | |||

| *{{IPA|/ɔ/}} as in ''bought'' (which is lowered, as in most of the U.S., and approaches {{IPA|}}; the ] is mostly at a transitional stage in these cities). | |||

| Today, the accents of Atlanta, Charleston, and Savannah are most similar to the ] or at least the larger ].{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|pp=260–1}}{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|p=68}} In all three cities, some speakers (though most consistently documented in Charleston and least consistently in Savannah) demonstrate the Southeastern fronting of {{IPA|/oʊ/}} and the status of the ] is highly variable.{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|p=68}} Non-rhoticity (''r''-dropping) is now rare in these cities, yet still documented in some speakers.{{sfnp|Labov|Ash|Boberg|2006|p=48}} | |||

| ==Older phonologies== | |||

| {{main|Older Southern American English}} | |||

| Before becoming a phonologically unified dialect region, the South was once home to an array of much more diverse accents at the local level. Features of the deeper interior Appalachian South largely became the basis for the newer Southern regional dialect; thus, older Southern American English primarily refers to the English spoken outside of Appalachia: the coastal and former plantation areas of the South, best documented before the ], on the decline during the early 1900s, and non-existent in speakers born since the ].{{sfnp|Thomas|2004|p=304}} | |||

| Little unified these older Southern dialects since they never formed a single homogeneous dialect region to begin with. Some older Southern accents were rhotic (most strongly in ] and west of ]), while the majority were non-rhotic (most strongly in plantation areas); however, wide variation existed. Some older Southern accents showed (or approximated) Stage 1 of the Southern Vowel Shift—namely, the glide weakening of {{IPA|/aɪ/}}—however, it is virtually unreported before the very late 1800s.{{sfnp|Thomas|2004|p=306}} In general, the older Southern dialects lacked the ], ], ], ], ], ], and ]s, all of which are now common to, or encroaching on, all varieties of present-day Southern American English. Older Southern sound systems included those local to the:{{sfnp|Thomas|2004|p=?}} | |||

| *Plantation South (excluding the Lowcountry): phonologically characterized by {{IPA|/aɪ/}} glide weakening, non-rhoticity (for some accents, including a ]), and the Southern trap–bath split (a version of the ] unique to older Southern U.S. speech that causes words like ''lass'' {{IPA|}} not to rhyme with words like ''pass'' {{IPA|}}). | |||

| **Eastern and central Virginia (often identified as the "Tidewater accent"): further characterized by ] and some vestigial resistance to the ]. | |||

| *] (of South Carolina and Georgia; often identified as the traditional "Charleston accent"): characterized by no {{IPA|/aɪ/}} glide weakening, non-rhoticity (including the coil-curl merger), the Southern trap–bath split, Canadian raising, the ], {{IPA|/eɪ/}} pronounced as {{IPA|}}, and {{IPA|/oʊ/}} pronounced as {{IPA|}}. | |||

| *] and ] (often identified as the "]"): characterized by no {{IPA|/aɪ/}} glide weakening (with the on-glide strongly backed, unlike any other U.S. dialect), the ], {{IPA|/aʊ/}} pronounced as {{IPA|}}, and up-gliding of ]s especially before {{IPA|/ʃ/}} (making ''fish'' sound almost like ''feesh'' and ''ash'' like ''aysh''). It is the only dialect of the older South still extant on the East Coast, due to being passed on through generations of geographically isolated islanders. | |||

| *Appalachian and Ozark Mountains: characterized by strong rhoticity and a ] (which still exists in that region), the Southern trap–bath split, plus the original and most advanced instances of the Southern Vowel Shift now defining the whole South. | |||

| ==Grammar== | |||

| These grammatical features are characteristic of both older and newer Southern American English. | |||

| <!-- Note: please put only examples of GRAMMAR in this section. Examples of Southern vocabulary (e.g. 'buggy' to mean 'cart' etc.) should be added to the Regional Vocabularies article. See link below. Thank you. --> | |||

| * Use of ''done'' as an ] between the subject and verb in sentences conveying the ]. | |||

| *:I done told you before. | |||

| * Use of ''done'' (instead of ''did'') as the past simple form of ''do'', and similar uses of the ] in place of the ], such as ''seen'' replacing ''saw'' as past simple form of ''see.'' | |||

| *:I only done what you done told me. | |||

| *:I seen her first. | |||

| * Use of other non-standard ]s, Such as ''drownded'' as the past tense of ''drown'', ''knowed'' as the past tense of ''know'', ''choosed'' as the past tense of ''choose'', ''degradated'' as the past tense of ''degrade''. | |||

| *:I knowed you for a fool soon as I seen you. | |||

| * Use of ''been'' instead of ''have been'' in ] constructions. | |||

| *:I been livin' here darn near my whole life. | |||

| * Use of ''(a-) fixin' to'', with several spelling variants such as ''fixing to'' or ''fixinta'',<ref>Metcalf, Allan A. (2000). How We Talk: American Regional English Today. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 37.</ref> to indicate immediate future action; in other words: ''intending to'', ''preparing to'', or ''about to''. | |||

| *:He's fixin' to eat. | |||

| *:They're fixing to go for a hike. | |||

| :It is not clear where the term comes from and when it was first used. According to dialect dictionaries, ''fixin' to'' is associated with Southern speech, most often defined as being a ] of ''preparing to'' or ''intending to''.{{sfnp|Bernstein|2003|p=?}} Some linguists, e.g. Marvin K. Ching, regard it as being a ''quasimodal'' rather than a ] followed by an ].<ref name="Ching">Ching, Marvin K. L. "How Fixed Is Fixin' to?" ''American Speech'', 62.4 (1987): 332-345, {{JSTOR|455409}}.</ref> It is a term used by all ], although more frequently by people with a lower ] than by members of the educated ]. Furthermore, it is more common in the speech of younger people than in that of older people.{{sfnp|Bernstein|2003|p=?}} Like much of the Southern dialect, the term is also more prevalent in rural areas than in urban areas. | |||

| * Preservation of older English ''me,'' ''him,'' etc. as reflexive datives. | * Preservation of older English ''me,'' ''him,'' etc. as reflexive datives. | ||

| *:I'm fixin' to paint me a picture. | |||

| *:He's gonna catch him a big one. | |||

| * Saying ''this here'' in place of ''this'' or ''this one'', and ''that there'' in place of ''that'' or ''that one''. | |||

| * Merging of adjective and adverbial forms of related words (''quick/quickly''), generally in favor of the adjective. | |||

| *:This here's mine and that there is yours. | |||

| :: He's movin' real quick. | |||

| * Existential ''it,'' a feature dating from Middle English which can be explained as by substituting ''it'' for ''there'' when ''there'' refers to no physical location, but only to the existence of something. | |||

| * Adverbial use of ''right'' to mean ''quite'' or ''fairly.'' | |||

| *:It's one lady who lives in town. | |||

| ::I'm right tired. | |||

| *:It is nothing more to say. | |||

| Standard English would prefer "existential ''there''", as in "There's one lady who lives in town". This construction is used to say that something exists (rather than saying where it is located).<ref name="Online Dict"> ''Online Dictionary of Language Terminology''. 4 Oct 2012</ref> The construction can be found in ] as in ]'s '']'': "Cousin, it is no dealing with him now".<ref name="Online Dict"/> | |||

| * Use of ''ever'' in place of ''every''. | |||

| *:Ever'where's the same these days. | |||

| *Using ''liketa'' (sometimes spelled as ''liked to'' or ''like to''<ref name="yale liketa">{{Cite web|url=https://ygdp.yale.edu/phenomena/liketa|title=Liketa | Yale Grammatical Diversity Project: English in North America|date=2018|website=Yale Grammatical Diversity Project (ygdp.yale.edu)|publisher=Yale University|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230404174847/https://ygdp.yale.edu/phenomena/liketa|archive-date=April 4, 2023|url-status=live}}</ref>) to mean "almost". | |||

| *:I liketa died.<ref name="Bailey Tillery">Bailey, Guy; and Tillery, Jan. "The Persistence of Southern American English." ''Journal of English Linguistics'', 24.4 (1996): 308-321. {{doi|10.1177/007542429602400406}}.</ref> | |||

| *:He liketa got hit by a car. | |||

| :Liketa is presumably a conjunction of "like to" or "like to have" coming from ]. It is most often seen as a synonym for almost. Accordingly, the phrase ''I like't'a died'' would be ''I almost died'' in Standard English. With this meaning, ''liketa'' can be seen as a verb ] for actions that are on the verge of happening.<ref>Wolfram, Walt; Schilling-Estes, Natalie (2015). ''''. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 48, 380.</ref> Furthermore, it is more often used in an exaggerated or violent figurative sense rather than a literal sense.<ref name="yale liketa"/> | |||

| *Use of the distal ] "yonder," archaic in most dialects of English, to indicate a third, larger degree of distance beyond both "here" and "there" (thus relegating "there" to a medial demonstrative as in some other languages), indicating that something is a longer way away, and to a lesser extent, in a wide or loosely defined expanse, as in the church hymn "When the Roll Is Called Up Yonder". A typical example is the use of "over yonder" in place of "over there" or "in or at that indicated place", especially to refer to a particularly different spot, such as in "the house over yonder".<ref>Regional Note from </ref> | |||

| * Compared to ], when ], Southern American English has an increased preference for contracting the subject and the auxiliary than the auxiliary and "not", e.g. the first of the following pairs: | |||

| *:''He's'' not here. / He ''isn't'' here. | |||

| *:''I've'' not been there. / I ''haven't'' been there.<ref>Wolfram, Walt; Reaser, Jeffrey (2014). ''''. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. pp. 94-95.</ref> | |||

| === |

===Multiple modals=== | ||

| ] has a strict ]. In the case of ], standard English is restricted to a single modal per ]. However, some Southern speakers use ] or more modals in a row (''might could, might should, might would, used to could,'' etc.--also called "modal stacking") and sometimes even triple modals that involve ''oughta'' (like ''might should oughta'') | |||

| *Word use tendencies from the Harvard Dialect Survey:<ref>Noted in the </ref> | |||

| *I might could climb to the top. | |||

| **Likely influenced by the dominance of ] in the ], a carbonated beverage in general is referred to as ''coke,'' or ''cocola,'' even if referring to non-colas. ''Soda'' is sometimes used, usually in large cities.<ref>http://cfprod01.imt.uwm.edu/Dept/FLL/linguistics/dialect/staticmaps/q_105.html Harvard Dialect Survey - word use: sweetened carbonated beverage</ref> | |||

| *I used to could do that. | |||

| **The shopping-cart at many stores as a ''buggy'' (or less often, ''jitney'' or ''trolley'').<ref>http://cfprod01.imt.uwm.edu/Dept/FLL/linguistics/dialect/staticmaps/q_75.html Harvard Dialect Survey - word use: wheeled contraption at grocery store</ref> | |||

| The origin of multiple modals is controversial; some say it is a development of ], while others trace them back to ] and others to ] settlers.{{sfnp|Bernstein|2003|p=?}} There are different opinions on which class preferably uses the term. {{Harvcoltxt|Atwood|1953}} for example, finds that educated people try to avoid multiple modals, whereas {{Harvcoltxt|Montgomery|1998}} suggests the opposite. In some Southern regions, multiple modals are quite widespread and not particularly stigmatized.<ref>Wolfram, Walt; Schilling-Estes, Natalie (2015). ''''. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. p. 379.</ref> Possible multiple modals are:<ref name="Di Paolo">Di Paolo, Marianna. "Double Modals as Single Lexical Items." American Speech, 64.3 (1989): 195-224.</ref> | |||

| *Use of the term "mosquito hawk" or "snake doctor" for a ] or a ] (''Diptera tipulidae'').<ref>Definition from </ref> | |||

| {| | |||

| *Use of "over yonder" in place of "over there" or "in or at that indicated place," especially when being used to refer to a particularly different spot, such as in "the house over yonder." Additionally, "yonder" tends to refer to a third, larger degree of distance beyond both "here" and "there," indicating that something is a long way away, and to a lesser extent, in an open expanse, as in the church hymn "When the Roll Is Called Up Yonder."<ref>Regional Note from </ref> | |||

| *Use of the phrase "chill bumps" instead of "goose bumps"<ref>http://cfprod01.imt.uwm.edu/Dept/FLL/linguistics/dialect/staticmaps/q_81.html Harvard Dialect Study - word use: skin bumps when cold</ref> | |||

| *Use of "]" to refer to a burner on a stove. "Watch out, the eye is still hot."{{Fact|date=January 2008}} | |||

| |- | |||

| == Dialects == | |||

| | may could || might could || might supposed to | |||

| In a sense, there is no one dialect called "Southern". Instead, there are a number of regional dialects found across the ]. Although different "Southern" dialects exist, they are all mutually intelligible, as are US and British English more broadly. | |||

| |- | |||

| | may can || might oughta || mighta used to | |||

| |- | |||

| | may will || might can || might woulda had oughta | |||

| |- | |||

| | may should || might should || oughta could | |||

| |- | |||

| | may supposed to || might would || better can | |||

| |- | |||

| | may need to || might better || should oughta | |||

| |- | |||

| | may used to || might had better || used to could | |||

| |- | |||

| | || can might || musta coulda | |||

| |- | |||

| | || could might || would better | |||

| |} | |||

| As the table shows, there are only possible combinations of an ] modal followed by ] modals in multiple modal constructions. Deontic modals express permissibility with a range from obligated to forbidden and are mostly used as markers of politeness in requests whereas epistemic modals refer to probabilities from certain to impossible.{{sfnp|Bernstein|2003|p=?}} Multiple modals combine these two modalities. | |||

| ===Conditional syntax and evidentiality=== | |||

| ===Atlantic=== | |||

| People from the South often make use of conditional or evidential ]es as shown below (italicized in the examples):{{sfnp|Johnston|2003|p=?}} | |||

| Conditional syntax in requests: | |||

| *'''Virginia Piedmont''' | |||

| :''I guess you could'' step out and git some toothpicks and a carton of Camel cigarettes ''if you a mind to''. | |||

| The ] dialect is possibly the most famous of Southern dialects because of its strong influence on the South's speech patterns. Because the dialect has long been associated with the upper or ] ] class in the ], many of the most important figures in Southern history spoke with a Virginia Piedmont accent. Virginia Piedmont is ], meaning speakers pronounce "R" only if it is followed by a vowel (contrary to New York City English, wherein non-rhotic accent is now mostly used by middle- and lower-class speakers). The dialect also features the '' Southern drawl'' (mentioned above). | |||

| :''If you be good enough to take it, I believe'' I could stand me a taste.{{sfnp|Johnston|2003|p=?}} | |||

| Conditional syntax in suggestions: | |||

| *'''Coastal Southern''' | |||

| :I wouldn't look for 'em to show up ''if I was you''. | |||

| ] resembles Virginia Piedmont but has preserved more elements from the colonial era dialect than almost any other region of the United States. It can be found along the coasts of the Chesapeake and the Atlantic in Maryland, Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia. It is most prevalent in the Charleston, South Carolina area. In addition, like Virginia Piedmont, Coastal Southern is non-rhotic. | |||

| :''I'd think'' that whiskey ''would be'' a trifle hot. | |||

| Conditional syntax creates a distance between the speaker's claim and the hearer. It serves to soften obligations or suggestions, make criticisms less personal, and to overall express politeness, respect, or courtesy.{{sfnp|Johnston|2003|p=?}} | |||

| Southerners also often use "]" predicates such as think, reckon, believe, guess, have the feeling, etc.: | |||

| ===Midland and Highland=== | |||

| :You already said that once, ''I believe''. | |||

| *'''South Midland or Highland Southern''' | |||

| :''I wouldn't want to guess, but I have the feeling'' we'll know soon enough. | |||

| This dialect arose in the inland areas of the South. It shares many of the characteristics of dialects of the ]s and ]. The area was settled largely by Scots-Irish, ], Northern and Western English, Welsh, and Germans. | |||

| :''You reckon'' we oughta get help? | |||

| :I ''don't believe'' I've ever known one. | |||

| Evidential predicates indicate an uncertainty of the knowledge asserted in the sentence. According to {{Harvcoltxt|Johnston|2003}}, evidential predicates nearly always hedge the assertions and allow the respondents to hedge theirs. They protect speakers from the social embarrassment that appears, in case the assertion turns out to be wrong. As is the case with conditional syntax, evidential predicates can also be used to soften criticisms and to afford courtesy or respect.{{sfnp|Johnston|2003|p=?}} | |||

| This dialect follows the ] in a generally southwesterly direction, moves from Kentucky, across Missouri and Oklahoma, and peters out in western Texas. It has assimilated some coastal Southern forms, most noticeably the loss of the diphthong /aj/, which becomes {{IPA|/aː/}}, and the second person plural pronoun "you-all" or "y'all". Unlike Coastal Southern, however, South Midland is a rhotic dialect, pronouncing {{IPA|/r/}} wherever it has historically occurred. | |||

| ==Vocabulary== | |||

| *'''Southern Appalachian''' | |||

| In the United States, the following vocabulary is mostly unique to, or best associated with, Southern U.S. English:<ref name = "Vaux">Vaux, Bert and Scott Golder. 2003. . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Linguistics Department.</ref> | |||

| Due to the isolation of the ] regions of the South, the Appalachian accent is one of the hardest for outsiders to understand. This dialect is also rhotic, meaning speakers pronounce "R"s wherever they appear in words, and sometimes when they do not (for example "worsh" for "wash.") | |||

| *''Ain't'' to mean ''am not'', ''is not'', ''are not'', ''have not'', ''has not'', etc.<ref name="Algeo"/> | |||

| *'']'' to express sympathy or concern to the addressee; often, now used sarcastically<ref>{{cite book | chapter-url=https://oxfordre.com/linguistics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.001.0001/acrefore-9780199384655-e-925 | doi=10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.013.925 | chapter=English in the U.S. South | title=Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics | date=2022 | last1=Hazen | first1=Kirk | isbn=978-0-19-938465-5 }}</ref> | |||

| *''Buggy'' to mean '']''<ref>"". ''The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language'', Fifth Edition. 2017. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.</ref> | |||

| *''Carry'' to additionally mean ''escort'' or ''accompany''<ref>"". ''The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language'', Fifth Edition. 2017. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.</ref> | |||

| *''Catty-corner'' to mean ''located or placed diagonally'' | |||

| *''Chill bumps'' as a ] for '']'' | |||

| *''Coke'' to mean any ] | |||

| *''Crawfish'' to mean '']'' | |||

| *''Cut on/off/out'' to mean ''turn on/off/out (lights or electronics)''<ref>"". ''The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language'', Fifth Edition. 2017. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.</ref> | |||

| *''Devil's beating his wife'' | |||

| *''Fixin' to'' to mean ''about to'' | |||

| *'']'' preferred over ''frosting'' in the confectionary sense | |||

| *''Liketa'' to mean ''almost'' or ''nearly'' (in Alabama and ])<ref name="yale liketa"/> | |||

| *''Ordinary'' to mean ''disreputable''<ref name="Dictionary.com">''''. Dictionary.com Unabridged, based on the ''Random House Dictionary''. Random House, Inc. 2017.</ref> | |||

| *''Ornery'' to mean ''bad-tempered'' or ''surly'' (derived from ''ordinary'')<ref>Berrey, Lester V. (1940). "". ''American Speech'', vol. 15, no. 1. p. 47.</ref> | |||

| *''Powerful'' to mean ''great in number or amount'' (used as an ])<ref name="Dictionary.com"/> | |||

| *''Right'' to mean ''very'' or ''extremely'' (used as an adverb)<ref>"". ''The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language'', Fifth Edition. 2017. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.</ref> | |||

| *''Reckon'' to mean ''think'', ''guess'', or ''conclude''<ref>"". ''The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language'', Fifth Edition. 2017. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.</ref> | |||

| *''Rolling'' to mean the prank of '']'' | |||

| *''Slaw'' as a synonym for '']'' | |||

| *''Taters'' to mean '']'' | |||

| *''Toboggan'' to mean '']'' | |||

| *''Tote'' to mean ''carry''<ref name="Algeo">Algeo, John (ed.) (2001). ''''. Cambridge University Press. pp. 275-277.</ref> | |||

| *''Tump'' to mean ''tip or turn over'' as an intransitive verb<ref>{{Cite web|title=Definition of TUMP|url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/tump|access-date=2021-03-16|website=www.merriam-webster.com|language=en}}</ref> (in the western South, including Texas and Louisiana) | |||

| *''Ugly'' to mean ''rude''<ref>"". ''The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language'', Fifth Edition. 2017. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.</ref> | |||

| *''Varmint'' to mean ''vermin'' or ''an undesirable animal or person''<ref>"". ''The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language'', Fifth Edition. 2017. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.</ref><ref name="Dictionary.com"/> | |||

| *''Veranda'' to mean ''large, roofed ]''<ref name="Dictionary.com"/> | |||

| *''Yonder'' to mean ''(far) over there''<ref name="Algeo"/> | |||

| Unique words can occur as Southern ] past-tense forms of verbs, particularly in the Southern highlands and ], as in ''yesterday they riz up, come outside, drawed, and drownded'', as well as participle forms like ''they have took it, rode it, blowed it up, and swimmed away''.<ref name="Algeo"/> ''Drug'' is traditionally both the past tense and participle form of the verb ''drag''.<ref name="Algeo"/> | |||

| ===Y'all=== | |||

| The Southern Appalachian dialect can be heard, as its name implies, in ], ], ], ], Western ], Eastern ], ], ], and ]. Southern Appalachian speech patterns, however, are not entirely confined to these mountain regions previously listed. | |||

| {{main|Y'all}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| '']'' is a second-person singular pronoun that used to refer to a ]. It is originally a ]{{spaced ndash}}''you all.''{{sfnp|Hazen|Fluharty|2003|p=59}} | |||

| The common thread in the areas of the ] where a rhotic version of the dialect is heard is almost invariably a traceable line of descent from ] or ] ancestors amongst its speakers. The dialect is also not devoid of early influence from Welsh settlers, the dialect retaining the ] tendency to pronounce words beginning with the letter "h" as though the "h" were silent; for instance "humble" often is rendered "umble". | |||

| *When addressing a single group collectively ''y'all'' is used. | |||

| *When addressing multiple distinct groups, ''all y'all'' is used ("I know all y'all.") | |||

| *The possessive form of ''Y'all'' is created by adding the standard "-'s" as in: "''I've got y'all's assignments here.''" {{IPA|/jɔlz/}} | |||

| ===Southern Louisiana=== | |||

| A popular myth claims that this dialect closely resembles ]. Although this dialect retains many words from the ] that are no longer in common usage, this myth is apocryphal. | |||

| {{Main|Cajun English|New Orleans English}} | |||

| Southern Louisiana English especially is known for some unique vocabulary: long sandwiches are often called ''poor boys'' or '']s'', ] called ''doodle bugs'', the end of a bread loaf called a ''nose'', ] and ]s alike called ''neutral ground'',<ref name = "Vaux"/> and sidewalks called ''banquettes''.<ref name="banquette">{{cite web | |||

| |url=http://www.bartleby.com/61/44/B0064400.html | |||

| |title=banquette | |||

| |publisher=The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition | |||

| |year=2000 | |||

| |access-date=2008-09-15 | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080420174317/http://www.bartleby.com/61/44/B0064400.html | |||

| |archive-date=2008-04-20 | |||

| |url-status=dead | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| ==Relationship to African-American English== | |||

| *'''Ozark''' | |||

| {{Main|African-American Vernacular English}} | |||

| This dialect developed in the heart of the ] in southern Missouri and northwest Arkansas. It is similar to Appalachian dialects but also has some Midwestern influences. This dialect is riddled with colorful expressions, and is frequently lampooned in popular culture, such as the television comedy ''].'' | |||

| Discussion of "Southern dialect" in the United States sometimes focuses on those English varieties spoken by white Southerners;{{sfnp|Thomas|2004|p=?}} However, because "Southern" is a geographic term, "Southern dialect" may also encompass dialects developed among other social or ethnic groups in the South. The most prominent of these dialects is ] (AAVE), a fairly unified variety of English spoken by ] and ] African-Americans throughout the United States. AAVE exhibits a relationship with both older and newer Southern dialects, though there is not yet a broad consensus on the exact nature of this relationship.{{sfnp|Thomas|2004|p=319}} | |||

| The historical context of race and ] is a central factor in the development of AAVE. From the 16th to 19th centuries, many Africans speaking a diversity of ] were captured, brought to the United States, and sold into slavery. Over many generations, these Africans and their African-American descendants picked up English to communicate with their white enslavers and the white servants that they sometimes worked alongside, and they also used English as a ] to communicate with each other in the absence of another common language. There were also some African Americans living as ] in the United States, though the majority lived outside of the South due to Southern state laws which enabled white enslavers to "recapture" anyone not perceived as white and force them into slavery. | |||

| *'''Florida Cracker''' | |||

| The dialect is derived from the South Midland dialect, and found throughout several regions of ] and in south ]. There are several different variations of the dialect found in Florida. From Pensacola to Tallahassee the dialect is non-rhotic and shares many characteristics with the speech patterns of southern ]. Another form of the dialect is spoken in northeast Florida, Central Florida, the Nature Coast and even in rural parts of South Florida. This dialect was made famous by ]' book '']''. | |||

| Following the American Civil War – and the subsequent national abolition of explicitly racial slavery in the 19th century – many newly freed African Americans and their families remained in the United States. Some stayed in the South, while others moved to join communities of African-American ] living outside of the South. Soon, ] followed by decades of cultural, sociological, economic, and technological changes such as ] and the increasing prevalence of ] further complicated the relationship between AAVE and all other English dialects. | |||

| The dialect also has some distinct words to it. Some speakers may call a river turtle a "cooter", a land ] a "gopher", a ] a "]", and a crappie fish a "speck". | |||

| Modern AAVE retains similarities to older speech patterns spoken among white Southerners. Many features suggest that it largely developed from ]s of colonial English as spoken by white Southern planters and British indentured servants, plus a more minor influence from the ] spoken by Black Caribbeans.<ref>{{cite book|title=Word on the Street: Debunking the Myth of a "Pure" Standard English|last=McWhorter|first=John H.|authorlink=John McWhorter|publisher=Basic Books|year=2001|page=152|isbn=9780738204468}}</ref> There is also evidence of some influence of West African languages on the vocabulary and grammar of AAVE. | |||

| ===Gulf of Mexico=== | |||

| *'''Gulf Southern & Mississippi Delta''' | |||

| This area of the South was settled by English speakers moving west from Virginia, Georgia, and the Carolinas, along with French settlers from Louisiana (see the section below). This accent is common in Mississippi, northern Louisiana, southern and eastern Arkansas, western Tennessee, and parts of East Texas. Familiar speakers include ] and ]. A dialect found in Georgia and Alabama has some characteristics of both the Gulf Southern dialect and the Virginia Piedmont/Coastal Southern dialect. | |||

| It is uncertain to what extent current white Southern English borrowed elements from early AAVE, and vice versa. Like many white accents of English once spoken in ] areas—namely, the Lowcountry, the Virginia Piedmont, Tidewater, and the lower Mississippi Valley—the modern-day AAVE accent is mostly non-rhotic (or "''r''-dropping"). The presence of non-rhoticity in both AAVE and old Southern English is not merely coincidence, though, again, which dialect influenced which is unknown. It is better documented, however, that white Southerners borrowed some ] processes from Black Southerners. | |||

| *'''Cajun''' | |||