| Revision as of 12:57, 1 June 2008 editTony May (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users3,624 edits →"Weeding-out": grammar← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 22:22, 20 December 2024 edit undo79.56.233.3 (talk)No edit summary | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|WWII Nazi abuse of Soviet POWs}}{{good article}} | |||

| {{Copyedit|date=February 2008}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=March 2021}} | |||

| {{Infobox civilian attack | |||

| | title = German atrocities against Soviet prisoners of war | |||

| | partof = ] | |||

| | image = File:Bundesarchiv Bild 146-1979-113-04, Lager Winnica, gefangene Russen.jpg | |||

| | image_size = | |||

| | caption = Distribution of food in a POW camp near ], Ukraine (July 1941) | |||

| | location = Germany and German-occupied Eastern Europe | |||

| | target = Captured Soviet troops | |||

| | date = 1941–1945 | |||

| | type = ], ], ]s, ] | |||

| | fatalities = 2.8{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=240}} to 3.3 million{{sfn|Kay|2021|p=167}} | |||

| | perps = Mostly ] | |||

| }} | |||

| During ], ] ] (POWs) held by ] and primarily in the custody of the ] were starved and subjected to deadly conditions. Of nearly six million who were captured, around three million died during their imprisonment. | |||

| ] | |||

| {{The Holocaust}} | |||

| In June 1941, Germany and ] ] and carried out a ] with complete disregard for the ]. Among the ] was for the ] and disregard for Germany's legal obligations under the ]. By the end of 1941, over 3 million Soviet soldiers had been captured, mostly in large-scale ] operations during the German Army's rapid advance. Two-thirds of them had died from starvation, exposure, and disease by early 1942. This is one of the highest sustained death rates for any mass atrocity in history. | |||

| The '''extermination of Soviet prisoners of war by Nazi Germany''' relates to the ] policies taken towards the captured soldiers of the ] by ]. These efforts resulted in some 3.3 million to 3.5 million deaths.<ref>Peter Calvocoressi, Guy Wint, ''Total War'' - "The total number of prisoners taken by the German armies in the USSR was in the region of 5.5 million. Of these, the astounding number of 3.5 million or more had been lost by the middle of 1944 and the assumption must be that they were either deliberately killed or done to death by criminal negligence. Nearly two million of them died in camps and close on another million disappeared while in military custody either in the USSR or in rear areas; a further quarter of a million disappeared or died in transit between the front and destinations in the rear; another 473,000 died or were killed in military custody in Germany or Poland." They add, "This slaughter of prisoners cannot be accounted for by the peculiar chaos of the war in the east. ... The true cause was the inhuman policy of the Nazis towards the Russians as a people and the acquiescence of army commanders in attitudes and conditions which amounted to a sentence of death on their prisoners."</ref><ref>"Soviet Casualties and Combat Losses in the Twentieth Century", Greenhill Books, London, 1997, G. F. Krivosheev</ref><ref>Christian Streit: Keine Kameraden: Die Wehrmacht und die Sowjetischen Kriegsgefangenen, 1941-1945, Bonn: Dietz (3. Aufl., 1. Aufl. 1978), ISBN 3801250164 - "Between 22 June 1941 and the end of the war, roughly 5.7 million members of the Red Army fell into German hands. In January 1945, 930,000 were still in German camps. A million at most had been released, most of whom were so-called "volunteers" (Hilfswillige) for (often compulsory) auxiliary service in the Wehrmacht. Another 500,000, as estimated by the Army High Command, had either fled or been liberated. The remaining 3,300,000 (57.5 percent of the total) had perished."</ref><ref> United States Holocaust Memorial Museum - "Existing sources suggest that some 5.7 million Soviet army personnel fell into German hands during World War II. As of January 1945, the German army reported that only about 930,000 Soviet POWs remained in German custody. The German army released about one million Soviet POWs as auxiliaries of the German army and the SS. About half a million Soviet POWs had escaped German custody or had been liberated by the Soviet army as it advanced westward through eastern Europe into Germany. The remaining 3.3 million, or about 57 percent of those taken prisoner, were dead by the end of the war."</ref><ref>Jonathan Nor, - "Statistics show that out of 5.7 million Soviet soldiers captured between 1941 and 1945, more than 3.5 million died in captivity."</ref> | |||

| ], ]s, and some officers, communists, intellectuals, ], and ] were systematically targeted for execution. More prisoners were shot because they were wounded, ill, or unable to keep up with forced marches. Over a million were deported to Germany for forced labor, where many died in sight of the local population. Their conditions were worse than civilian forced laborers or prisoners of war from other countries. More than 100,000 were transferred to ], where they were treated worse than other prisoners. An estimated 1.4 million Soviet prisoners of war served as ] or ]; collaborators were essential to the German war effort and ] in Eastern Europe. | |||

| ==Summary== | |||

| Deaths among these Soviet prisoners of war have been called "one of the greatest crimes in military history",{{sfn|Hartmann|2012|p=568}} second in number only to those of civilian Jews but far less studied. Although the Soviet Union announced the death penalty for surrender early in the war, most former prisoners were reintegrated into Soviet society. Most defectors and collaborators escaped prosecution. Former prisoners of war were not recognized as veterans, and did not receive any ] until 2015; they often faced discrimination due to the perception that they were traitors or deserters. | |||

| During ], the ] ] of the Soviet Union (USSR), and the subsequent ], millions of ] ] were taken. Most of them were arbitrarily ] in the field by the German forces (in particular by the notorious ]), died under inhuman conditions in German ]s and during ruthless ]es from the ]s, or were shipped to ] for ]. | |||

| ==Background== | |||

| According to the estimate by the ] (USHMM), some 3.3 million Soviet POWs died in the Nazi custody out of 5.7 million. This figure represents a total of 57%, nearing the ]'s ]ish death rate of over 60%<ref>American Jewish Committee, , , Press of Jewish Publication Society of America, Philadelphia, 1946, page 599</ref>) and may be contrasted with only 8,300 out of 231,000 British and American prisoners, or 3.6%.<ref> USHMM</ref> Some estimates range as high as 5 million dead, including these killed immediately after surrendering (an indeterminate, although certainly very large number).<ref> Progressive Labor Party</ref><ref name="subhumans"/> Only 5% of the Soviet prisoners who died were of Jewish ethnicity.<ref> Berkeley Internet Systems</ref> Among those who died was even the son of the Soviet dictator ], ]. | |||

| ] Red Army soldiers in red]] | |||

| ] and its allies ] on 22 June 1941.{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=67}}{{sfn|Bartov|2023|p=201}} The Nazi leadership believed that war with its ideological enemy was inevitable{{sfn|Quinkert|2021|p=173}} due to the Nazi dogma that conquering territory to the east—called living space ({{lang|de|]}})—was essential to Germany's long-term survival,{{sfn|Quinkert|2021|pp=174–175}}{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=67}} and the reality that the ]'s ] were necessary to continue the German war effort.{{sfn|Quinkert|2021|pp=175–176}}{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=67}} The vast majority of German military manpower and ] was devoted to the invasion, which was carried out as a ] with ] for the ].{{sfn|Beorn|2018|pp=121–122}}{{sfn|Bartov|2023|pp=201–202}} Due to supply shortages and inadequate transport infrastructure, the German invaders planned to feed their army by looting (although in practice they remained dependent on shipments from Germany){{sfn|Tooze|2008|pp=479–480, 483}}{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=68}} and to forestall resistance by terrorizing the local inhabitants with preventative killings.{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=68}} | |||

| The Nazis believed that the Jews had ] and the ] was ] by an ];{{sfn|Quinkert|2021|p=174}} by killing ] and ], they expected that resistance would quickly collapse.{{sfn|Quinkert|2021|p=181}} The Nazis anticipated that much of the Soviet population (especially in the western areas) would welcome the German invasion, and hoped to exploit tensions between ] in the long run.{{sfn|Quinkert|2021|pp=181–182}} Soviet citizens were categorized according to a racial hierarchy: ] and ] at the top, Ukrainians and Russians in the middle, ] and Jews lowest. Informed by ] and Germany's experience during ], this hierarchy heavily influenced the treatment of prisoners of war.{{sfn |Hartmann |2012|p=614}} | |||

| The most deaths took place in a mere eight months of June 1941-January 1942, when the Germans killed an estimated 2.8 million Soviet POW primarily through ],<ref>Daniel Goldhagen, ''Hitler's Willing Executioners'' (p. 290) - "2.8 million young, healthy Soviet POWs" killed by the Germans, "mainly by starvation ... in less than eight months" of 1941-42, before "the decimation of Soviet POWs ... was stopped" and the Germans "began to use them as laborers" (emphasis added).</ref> ], and ], in what has been called, along with the ], an instance of "the most concentrated ] in human history (...) eclipsing ]".<ref name="case">{{cite web|url=http://www.gendercide.org/case_soviet.html|title=Case Study: Soviet Prisoners-of-War (POWs), 1941-42|work=Gendercide Watch|accessdate=2007-07-22}}</ref> By September 1941, the mortality rate among Soviet POWs was on the order of 1% per day.<ref name="subhumans">, James Weingartner, 3/22/1996</ref> According to the USHMM, by the winter of 1941, "starvation and ] resulted in mass death of unimaginable proportions".<ref name="treatment" /> This terrible starvation (leading many of desperate prisoners to resort to the acts of ]<ref name="case" />) was a deliberate Nazi policy in spite of food being available,<ref> Canadian Slavonic Papers</ref> in accordance to the ] developed by the ] Minister of Food ]. | |||

| Another lesson from World War I was the importance of securing food supplies to avoid a repeat of the ].{{sfn|Quinkert|2021|p=173}} ] the Soviet Union's "deficit areas" (particularly in the north) that required food imports from its "surplus areas", especially in Ukraine, to redirect this food to Germany or the German army. If the food supply was cut off as planned, an estimated 30 million people—mostly Russians—were expected to die.{{sfn|Quinkert|2021|pp=176–177}} In reality, the army lacked the resources to cordon off these large areas.{{sfn|Quinkert|2021|p=190}} More than a million{{sfn|Kay|2021|pp=167–168}} Soviet civilians died from smaller-scale blockades of Soviet urban areas (especially ] and ]) that were less effective than expected because of flight and ] activity.{{sfn|Quinkert|2021|p=190}}{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|pp=221–222}}{{sfn|Kay|2021|p=142}} As prisoners of war were held under tighter control than urban or Jewish civilians, they had a higher death rate from starvation.<ref>{{bulleted list| | |||

| By comparison, close to 1 million German prisoners of war died in ] out of 3.15 to 4 million prisoners taken according to estimates by Western historians <ref name="black book"> Nicolas Werth, Karel Bartošek, Jean-Louis Panné, Jean-Louis Margolin, Andrzej Paczkowski, ], '']: Crimes, Terror, Repression'', ], 1999, hardcover, 858 pages, ISBN 0-674-07608-7, page 322 </ref>, whereas the official Soviet number was 570,000 deaths<ref name="Ann"/>. Death rates in Soviet and German camps were similar <ref name="Ann">According to ], "In the few months of 1943, death rates among captured POWs hovered to 60 percent ... Similar death rates prevailed among Soviet soldiers in German captivity: the Nazi-Soviet war was truly a fight to the death" (cited from Anne Applebaum, ''Gulag: A History'', Doubleday, April, 2003, ISBN 0-7679-0056-1; page 431.) </ref><ref name="case" /> | |||

| |{{harvnb|Quinkert|2021|p=190}} | |||

| |{{harvnb|Kay|2021|p=146}} | |||

| |{{harvnb|Gerlach|2016|p=226}} | |||

| |{{harvnb|Tooze |2008|pp=481–482}} | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| ==Planning and legal basis== | |||

| ==Commissar Order== | |||

| Before World War II, the treatment of prisoners of war had occupied a central role in the codification of the law of war and detailed guidelines were laid down in the ].{{sfn |Hartmann |2012|p=569}} Germany was a signatory of the 1929 ], and generally adhered to it with non-Soviet prisoners.{{sfn|Blank|Quinkert|2021|p=18}}{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=235}} These laws were covered in Germany's ], and there was no legal ambiguity that could be exploited to justify its actions.{{sfn |Hartmann |2012|p=569}} Unlike Germany, the Soviet Union was not a signatory of either convention; its offer to abide by the Hague Convention's provisions regarding prisoners of war if the German army did likewise was rejected by ] several weeks after the start of the war.{{sfn|Moore|2022|pp=212–213}} The ] said that the Geneva Convention did not apply to Soviet prisoners of war, but suggested that it be the basis of planning. Law and morality played (at best) a minor role in this planning, in contrast to the demand for labor and military expediency.{{sfn |Hartmann |2012|pp=571–572}} ] privately that "we must distance ourselves from the standpoint of soldierly comradeship" and fight a "war of extermination" because Red Army soldiers were "no comrade" of Germans. No one present raised any objection.{{sfn|Hartmann|2013|loc="Prisoners of War"}}{{sfn|Blank|Quinkert|2021|p=15}} Although the mass deaths of prisoners in 1941 were controversial within the military, ] officer ] was one of the few who favored treating Soviet prisoners according to the law.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=242}} | |||

| {{main|Commissar Order}} | |||

| Anti-Bolshevism, antisemitism, and racism are often cited as the main reasons behind the mass death of prisoners, along with the regime's conflicting demands for security, food, and labor.{{sfn|Quinkert|2021|pp=172, 183}} There is still disagreement between historians to what extent the mass deaths of prisoners in 1941 can be attributed to ideological reasons as part of the planned racial restructuring of Germany's empire versus a logistical failure that interrupted German planners' intent to use the prisoners as a labor reserve.{{sfn|Westermann|2023|pp=95–96}}{{sfn|Quinkert|2021|pp=172, 188, 190}}{{sfn|Hartmann|2012|pp=630–631}} More than three million Soviet soldiers were captured by the end of 1941.{{sfn|Edele|2017|p=23}} Though this was fewer than expected by the German military,{{sfn|Kay|2021|pp=148, 153}} little planning had been done for housing and feeding the prisoners.{{sfn|Moore|2022|pp=240–241}}{{sfn |Quinkert|2021|p=184}}{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=207}} During the ] in 1940, ]; historian ] cites this as evidence that supply and logistics cannot explain the mass death of Soviet prisoners of war.{{sfn|Kay|2021|pp=248, 253}} Historians like ] and ] also suggested that German disregard for the Geneva Convention and resulting atrocities against POWs ] from the ], reaching their apogeum in the USSR a few years later.{{sfn|Moore|2022|pp=27–28}}<ref name=":6">{{Cite book |last=Rossino |first=Alexander B. |url=https://books.google.co.kr/books?id=MAhnAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=rossino+hitler&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiYza7k-LKKAxVyk68BHaGdE7MQ6AF6BAgHEAI |title=Hitler Strikes Poland: Blitzkrieg, Ideology, and Atrocity |date=2003 |publisher=University Press of Kansas |isbn=978-0-7006-1234-5 |language=en}}</ref>{{Rp|page=|pages=179-185}} | |||

| ==Prisoner-of-war camps== | |||

| The prisoners were stripped of their supplies, and as it became colder, their clothing by ill-equipped German troops with fatal results.<ref name="subhumans"/> The camps established specially for the Soviets were called ''Russenlager'';<ref name="das">{{de icon}} </ref> in others, the Soviets were kept separated from the prisoners from other countries. The ] ] kept by Germany were usually treated in accordance with the ] (signed by Germany but not by the Soviet Union). | |||

| ==Capture== | |||

| In the case of the Soviet POWs, most of the camps were simply open areas with no housing and were fenced off with ] and ]s.<ref name="case" /> These meager conditions forced the crowded prisoners to live in holes they had dug for themselves, which were exposed to the elements. ]s and other ] by the guards were common, and prisoners were malnourished, often consuming only a few hundred ]. Medical treatment was nonexistent and a ] offer to help in 1941 was rejected by ].<ref name="forgetten" /><ref name="treatment" /> Some of these conditions were actually worse than those of the prisoners in the German concentration camps. | |||

| <!-- ] --> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] soldiers captured between ] and ], June 1941]] | |||

| By mid-December 1941, 79 percent of prisoners captured to date (more than two million) had been apprehended during thirteen major battles ];{{sfn|Edele|2017|p=35}}{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=215}} three or four Soviet soldiers were captured for each one killed.{{sfn|Edele|2017|pp=34–35}} The number of Soviet soldiers captured fell dramatically after the ] in late 1941. The ratio of prisoners to killed also fell,{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=220}} but remained higher than the German side.{{sfn|Edele|2017|pp=34–35}} | |||

| Military factors such as poor leadership, lack of arms and ammunition, and being overwhelmed by the German advance were the most important factors causing the mass surrender of Red Army soldiers.{{sfn|Edele|2017|pp=165–166}} Opposition to the Soviet government was another important factor in surrenders and defections,{{sfn|Edele|2017|p=4}} which far exceeded the defection rate of other belligerents.{{sfn|Edele|2017|p=36}} Historian ] estimates that at least hundreds of thousands (possibly more than a million) Soviet soldiers defected during the war.{{sfn|Edele|2017|p=31}} | |||

| ===Camps=== | |||

| Soviet soldiers were usually captured in encirclements by Axis front-line troops, who took them to a collection point.{{sfn |Hartmann |2012|p=575}} From there, the prisoners were sent to transit camps.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=211}}{{sfn|Overmans|2022|p=24}} When many of the transit camps were shut down beginning in 1942, prisoners were sent directly from the collection point to a ].{{sfn|Overmans|2022|p=24}} Sometimes the prisoners were stripped of their winter clothing by their captors for their own use as temperatures dropped late in 1941.{{sfn|Hartmann|2012|p=520}} Wounded and sick Red Army soldiers usually received no medical care.{{sfn |Hartmann |2012|pp=527–528}}{{sfn|Blank|Quinkert|2021|p=27}} | |||

| ;]: Allied officers at ] were barred from sharing Red Cross packages with starving Soviet prisoners.<ref name="forgetten"> By Jonathan Nor, TheHistoryNet</ref> | |||

| ;]: In July 1941 a new compound, Oflag XIII-D, was set up for higher ranking Soviet ]s captured during Operation Barbarossa. It was closed April 1942; the surviving officers (many had died during the winter due to an ]) were transferred to the other camps. | |||

| ;]: The sick inmates were to be shot once a week.<ref name="forgetten" /> | |||

| ;]: According to the 1944 Soviet report, 43,000 captured Red Army personnel either were killed or died from diseases and starvation there.<ref name="Strods">{{cite journal | last = Strods | first = Heinrihs | title = Salaspils koncentrācijas nometne (1944. gada oktobris – 1944. gada septembris | journal = Yearbook of the Occupation Museum of Latvia | volume = 2000 | pages = pp. 87–153 | date = 2000 | id = {{ISSN|1407-6330}} }} {{lv icon}}</ref> | |||

| ;]: An epidemic of ] led to the murder of some 6,000 Red Army prisoners between ]-], ] (3,261 of them on the first day), conducted by the notorious Police Battalion 306.<ref name="forgetten" /> | |||

| ;]: About 50,000 prisoners died in the camp,<ref></ref> the vast majority of them Soviets. | |||

| ;]: The construction of the second camp, Lager-Ost, started in June 1941 to accommodate the large numbers of Soviet prisoners taken in Operation Barbarossa. In November 1941 a ] epidemic broke out in the Lager-Ost; it lasted until March 1942 and an estimated 45,000 prisoners died and were buried in ]s. The camp administration did not start any preventive measures until some German soldiers became infected. | |||

| ;] | |||

| ;]: In July 1941 Soviet prisoners taken during Operation Barbarossa arrived. They were held in separated facilities and suffered severe conditions and disease. The majority of the Soviet prisoners (up to 12,000) were killed, starved to death or died due to disease.<ref></ref> | |||

| ;]: In June-September 1941 Soviet prisoners from Operation Barbarossa were placed in another separated camp. Conditions were appalling, and starvation, epidemics and ill-treatment took a heavy toll of lives;<ref name="das" /> the dead Soviet prisoners were buried in mass graves. | |||

| ;]: In July about 11,000 Soviet soldiers, and some officers, arrived. By April 1942 only 3,279 remained; the rest had died from ] and a typhus epidemic caused by the deplorable sanitary conditions, and their bodies were buried in mass graves. After April 1942 more Soviet prisoners arrived and died just as rapidly. At the end of 1942 10,000 reasonably healthy Soviet prisoners were transferred to ] to work in the ]s; the rest, suffering from ], continued to die at the rate 10-20 per day. | |||

| ;]: Of the 10,677 inmates in the camp before the typhoid fever epidemic in December 1941, only 3,729 were alive when it ended in April 1942. In 1942 at least 1,000 were "weeded-out" by ] and shot in ].<ref></ref> | |||

| ;]: During 1941-1942 many Soviet POWs arrived, but they were kept in separate enclosures and received much harsher treatment than the other prisoners. Thousands of them died of malnutrition and disease. | |||

| ;]: In summer 1941 over 2,000 Soviet prisoners from Operation Barbarossa arrived. Conditions were appalling, starvation, epidemics and ill-treatment took a heavy toll of lives. The dead were buried in mass graves. | |||

| ;]: Between 40,000 and 60,000 prisoners died there, mostly buried in three mass graves. A Soviet war cemetery is still in existence, containing about 200 named graves. | |||

| ;]: During the 5,5 years about 1,000 prisoners died at the camp, over 800 of them Soviets (mostly officers). At the end of the war there were still 27 Soviet ]s in the camp who had survived the mistreatment that they, like all Soviet prisoners, had been subjected to. The new prisoners were inspected upon arrival by local ] Gestapo agents; some 484 were found to be "undesirable" and immediately sent to concentration camps and murdered.<ref name="forgetten" /> | |||

| ;]: In late 1941 nearly 50,000 prisoners were crowded into a space designed for only one third that number. Conditions were appalling, starvation, epidemics and ill-treatment took a heavy toll of lives. By early 1942 the surviving Soviets had been transferred to other camps. | |||

| ;]: The first Soviets arrived in July 1941; by June 1942 more than 100,000 prisoners were crowded into this camp. As a result of starvation and disease, mainly typhoid fever and tuberculosis, close to half of them died before the end of the war. | |||

| ;]: Physical and sanitary conditions were terrible and of the estimated 300,000 Soviet prisoners who passed through this camp, about one third (some 100,000) died of starvation, mistreatment and disease. | |||

| ;] | |||

| ;]: In July 1941, over 10,000 Soviet army officers were imprisoned here. Thousands of them died in the winter of 1941/2 as the result of a typhoid fever epidemic. | |||

| ;]: In July 1941, about 20,000 Soviet prisoners captured during Operation Barbarossa arrived; they were housed in the open while huts were being built. Some 14,000 POWs died during the winter of 1941–42. In the late 1943 the POW camp was closed and the entire facility became ].<ref></ref> | |||

| === |

===Summary executions=== | ||

| Especially in 1941, German soldiers often ] on the Eastern Front and shot Soviet soldiers who tried to surrender{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=225}}—sometimes in large groups of hundreds or thousands.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=203}} The German military did not record deaths that occurred prior to prisoners arriving at the collection points.{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=204}}{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=202}} These murders were not ordered by the high command,{{sfn|Quinkert|2021|p=187}}{{sfn|Edele|2017|p=52}} and some military commanders recognized their harmfulness to German interests. Nevertheless, efforts to discourage such killing had mixed results at best{{sfn|Edele|2017|pp=50–51}} and no {{ill|German military court|de|Militärgerichtsbarkeit (Nationalsozialismus)}} verdicts against the perpetrators are known.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=202}} Although the Red Army shot enemy prisoners less commonly than the German Army did,{{sfn|Edele|2016|pp=346–347}} the shooting of prisoners by both armies contributed to a mutual escalation of violence.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=206}} | |||

| In the "weeding-out programs" (''Aussonderungsaktionen'') in 1941-1942, the Gestapo further identified ] and state officials, ]s, academic ]s, Jews (some of the ] ]s were mistaken for Jews) and other "undesirable" or "dangerous" individuals who survived the Commissar Order selections, and transferred them to concentration camps, where they were immediately ].<ref name="nomercy"></ref> In all, between June 1941 and May 1944 about 10% of all Soviet POWs were turned over to the ] concentration camp organization or the ] murder squads and killed.<ref name="subhumans"/> | |||

| Thousands or tens of thousands of Red Army soldiers were executed on the spot as partisans.{{sfn|Quinkert|2021|p=188}}{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=206}}{{sfn |Hartmann |2012|p=579}} To prevent the growth of a ], Red Army soldiers overtaken by the German advance without being captured were ordered by the Supreme Command of Ground Forces (]) to present themselves to the German authorities under the threat of ]. Despite the order, few soldiers turned themselves in;{{sfn |Hartmann |2012|pp=522–523, 578–579}}{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=206}} some evaded capture and returned to their families.{{sfn |Hartmann |2012|p=581}} | |||

| ==Concentration and extermination camps== | |||

| At least 140,000 up to 500,000 Soviet prisoners of war died or were executed in Nazi concentration camps,<ref name="treatment"> USHMM</ref> most of them by ] or ]. Some were also ] (in one such case, a Dr. ] from ] starved prisoners to death while performing "famine experiments";<ref></ref><ref>, '']'', Dec 1, 2003</ref> in another, prisoners were shot using ]<ref name="forgetten" />).<ref name="case" /> | |||

| Before the beginning of the war, the OKW ] of captured Soviet ]s and suspicious civilian political functionaries.{{sfn|Kay|2021|p=159}}{{sfn|Quinkert|2021|pp=180–181}} More than 80 percent of front-line German divisions fighting on the Eastern Front carried out this illegal order, shooting an estimated 4,000 to 10,000 commissars.{{sfn|Kay|2021|pp=159–160}} These killings did not reduce Soviet resistance, and came to be perceived as counterproductive;{{sfn|Quinkert|2021|pp=190, 192}} the order was rescinded in May 1942.{{sfn |Hartmann |2012|p=512}} Although female combatants in the Soviet army defied ], the OKH ordered them to be treated as prisoners of war, they could be shot on sight and few survived to reach prisoner-of-war camps in Germany.{{sfn|Hartmann |2012|pp=524–525}}{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=205}}{{sfn|Kay|2021|pp=163–164}} | |||

| ;]: From about 15,000 Soviet POWs who were brought to Auschwitz I for work, only 92 remained alive at the last ] (about 3,000 of them were killed by being shot or gassed immediately after arriving).<ref> Auschwitz-Birkenau memorial and museum</ref> The Soviets were treated worse than any other prisoners.<ref> Literature of the Holocaust</ref> Out of the first 10,000 brought to work in 1941, 9,000 died in the first five months.<ref> Auschwitz-Birkenau memorial and museum</ref> A group of about 600 Soviet prisoners were about these gassed in the first ] experiments on ] ]; in December 1941, a further 900 Soviet POWs were murdered by means of gas.<ref>, by Heinz Peter Longerich</ref> In March 1941, ] ordered the construction of a large camp for 100,000 Soviet POWs at ], in close proximity to the main camp. Most of the Soviet prisoners were dead by the time Birkenau was reclassified as the Auschwitz II concentration camp in March 1942.<ref> University of North Carolina Press</ref> | |||

| ;]: 8,483 Soviet POWs were selected in 1941-1942 by a task force of three ] Gestapo officers and sent to the camp for immediate liquidation by a gunshot to the back of the neck, the infamous ''Genickschuss'' using a ]. | |||

| ;]: The victims murdered at the Chełmno killing center included several hundred ] and Soviet prisoners of war. | |||

| ;]: Some 500 Soviet prisoners of war were executed by a ] at Dachau. | |||

| ;]: More than 1,000 Soviet prisoners of war were executed in Flossenbürg by the end of 1941; executions continued sporadically through 1944. The POWs at one of the sub-camps staged a failed uprising and mass escape attempt on ], ]. The SS also established a special camp for 2,000 Soviet prisoners of war within Flossenbürg itself. | |||

| ;]: 65,000 Soviet POWS killed by feeding them only a thin soup of grass, water, and salt for six months.<ref name="treatment" /> In October 1941 the SS transferred about 3,000 Soviet POWs to Gross-Rosen for execution by shooting.<ref> USHMM</ref> | |||

| ;]: A group of 70 POWs were told that they would undergo a medical examination, but instead were injected with ], a deadly poison. | |||

| ;]: The first transport directed toward Majdanek consisted of 5,000 Soviet POWs; arriving in the fall of 1941 they soon died of starvation and exposure.<ref> The Holocaust: Lest we forget</ref> Executions were conducted by the shooting of prisoners in trenches.<ref name="treatment" /> | |||

| ;]: Following the outbreak of the Soviet-German War the camps started to receive a large number of Soviet POWs; most of them were kept in huts separated from the rest of the camp. The Soviet prisoners of war were a major part of the first groups to be gassed in the newly-built gas chamber in early 1942; at least 2,843 of them were murdered in the camp. According to USHMM, "so many POWs were shot that the local population complained that their water supply had been contaminated. The rivers and streams near the camp ran red with blood."<ref name="treatment" /> | |||

| ;] | |||

| ;]: The Soviet POWs were victims of the largest part of the executions that took place at Sachsenhausen. Thousands of them were murdered immediately after arriving at the camp, including 9,090 executed between ] and ], ].<ref name="forgetten" /> | |||

| ;]: Soviet prisoners of Jewish ethnicity were among hundreds of thousands people gassed at Sobibór. Soviet soldier, ], led the successful mass breakout after which the Germans closed the camp. | |||

| == |

==Prisoner-of-war camps == | ||

| <!-- ] --> | |||

| ] | |||

| <!-- ], Russia (June 1942)]] | |||

| ] (24 July 1941)]] | |||

| --> | |||

| <!-- For a time in late 1941, the supply of prisoners seemed infinite to Nazi leaders.{{sfn|Wachsmann|2015|p=277}} --> | |||

| By the end of 1941, 81 camps had been established on occupied Soviet territory.{{sfn|Hartmann|2013|loc="Prisoners of War"}} Permanent camps were established in areas under civilian administration and areas under ] that were planned to be turned over to civilian administration.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=211}} Due to the low priority attached to prisoners of war, each camp commandant had autonomy limited only by the military and economic situation. Although a few tried to ameliorate their conditions, most did not.{{sfn|Moore|2022|pp=218–219}}{{sfn |Hartmann |2012|pp=583–584}}{{sfn|Pohl|2012|pp=227–228}} At the end of 1944, all prisoner-of-war camps were placed under ] chief ]'s authority.{{sfn |Hartmann |2012|p=568}} Although military authorities from the OKW down also distributed orders to refrain from excessive violence against prisoners of war, historian David Harrisville says that these orders had little effect in practice and their main effect was to bolster a positive self-image in German soldiers.{{sfn|Harrisville|2021|pp=38–40}} | |||

| ===Death marches=== | |||

| In January 1942, Hitler authorized better treatment of the Soviet POWs because the war had bogged down, and German leaders decided to use prisoners for ] (see ]).<ref name="labor" /> Their number increased from barely 150,000 in 1942, to the peak of 631,000 in the summer of 1944. | |||

| ] | |||

| <!-- ] (July 1941)]] | |||

| --> | |||

| Prisoners were often forced to march hundreds of kilometers on foot with no or inadequate food or water.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=207}}{{sfn|Quinkert|2021|p=187}} Guards frequently shot anyone who fell behind,{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=207}}{{sfn|Quinkert|2021|p=187}}{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=222}} and the quantity of corpses left behind created a health hazard.{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=222}} Sometimes Soviet prisoners were able to escape due to inadequate supervision. The use of railcars for transport was often forbidden to prevent the spread of disease,{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=222}} though open cattle wagons were used after October 1941, which resulted in the death of some 20 percent of passengers due to cold weather.{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=222}}{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=207}} A figure of 200,000 to 250,000 deaths in transit is provided in Russian estimates.{{sfn|Quinkert|2021|p=188}}{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=210}} | |||

| ===Housing conditions=== | |||

| Many were dispatched to the ]s (between ] and ], ], 27,638 Soviet POWs died in the ] alone), while others were sent to ], ] or countless smaller companies,<ref name="forgetten" /> where they provided labour while being slowly ]. The largest "employers" of 1944 were mining (160,000), ] (138,000) and the ] (131,000). Not less than 200,000 prisoners died during forced labor. | |||

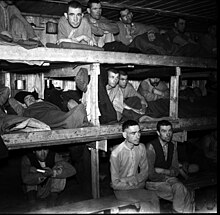

| ], June or July 1941]] | |||

| <!-- ] --> | |||

| Poor housing and the cold were major factors in the mass deaths.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=212}} Prisoners were herded into open, fenced-off areas with no buildings or latrines; some camps did not have running water. Kitchen facilities were rudimentary, and many prisoners got nothing to eat.{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=220}}{{sfn |Hartmann |2012|pp=584–585}} Some prisoners had to live in the open for the entire winter, or in unheated rooms, or in burrows they dug themselves which often collapsed.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=212}} In September 1941, the Germans started preparations for winter housing; the building of barracks was rolled out systematically in November.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=211}} These preparations were inadequate. The situation improved because the mass deaths made the camps less overcrowded.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=212}} The death toll at many prisoner-of-war camps was comparable to the largest Nazi concentration camps.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=221}} One of the largest camps was ] in ], where an estimated 30,000 to 40,000 Red Army soldiers died.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=224}} | |||

| There were relatively few guards{{sfn |Hartmann |2012|p=583}} and the liberal use of firearms was encouraged by military superiors such as ]. Both of these factors contributed to brutality.{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=220}} The Germans recruited prisoners—mainly Ukrainians, ], and ]—as camp police and guards.{{sfn |Hartmann |2012|p=583}} Regulations specified that the camps be surrounded by ] and double ] fences {{convert |2.5|m|sp=us}} high.{{sfn |Hartmann |2012|p=582}} Despite draconian penalties, organized resistance groups formed at some camps and attempted mass escapes.{{sfn|Moore|2022|pp=255, 256}} Tens of thousands of Soviet prisoners of war attempted to escape; about half were recaptured,{{sfn|Kozlova|2021|p=221}} and around 10,000 reached ].{{sfn|Hertner|2023|p=409}} If they did not commit crimes after their escape, recaptured prisoners were usually returned to the prisoner-of-war camps; otherwise, they were turned over to the ] and imprisoned (or executed) in a nearby concentration camp.{{sfn|Kozlova|2021|p=221}} | |||

| ==Soviet reprisals against former POWs== | |||

| ===Hunger and mass deaths=== | |||

| The Soviet POWs who survived German captivity were often accused by the Soviet authorities of ] or branded as ]s under ], which prohibited any soldier from ]. On 11 May 1945, Soviet government created more than 100 new "filtration camps", each for 10,000 people. More than 4.2 million Soviet citizens, including 1,545,000 surviving prisoners of war, were repatriated between May 1945 and February 1946. According to '']'', 19.1% of them were sent to ] of Red Army, 14.5% were sent to forced labour "reconstruction battalions" (usually for two years), and 360,000 people were sentenced to ten to twenty years in ].<ref name="black book"> Nicolas Werth, Karel Bartošek, Jean-Louis Panné, Jean-Louis Margolin, Andrzej Paczkowski, ], '']: Crimes, Terror, Repression'', ], 1999, hardcover, 858 pages, ISBN 0-674-07608-7, page 322 </ref><ref name="labor" /> The survivors were released during the general ] for all POWs and accused collaborators in 1955, after the death of Stalin. | |||

| ], the headquarters of ] ''(pictured in August 1941)'', 300 to 600 prisoners died each day in late 1941 and early 1942.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=222}}]] | |||

| Soviet historian ] gives slightly different numbers based on documents provided by the ]: 233,400 were found guilty of collaborating with the enemy and sent to Gulag camps out of 1,836,562 Soviet soldiers that returned from captivity.<ref>{{ru icon}} Russia and USSR in the wars of XX century - Losses of armed forces</ref> Latter data do not include millions of civilians who have been repatriated (often involuntarily) to the Soviet Union, and a significant number of whom were also sent to Gulag or executed (i.e. ]). Many Western and modern Russian scholars contend that "Soviet historians engaged for the most part in a ] campaign about the extent of the prisoner-of-war problem."<ref name="MU">Rolf-Dieter Müller, Gerd R. Ueberschär, ''Hitler's War in the East, 1941-1945: A Critical Assessment'', Berghahn Books, 2002, ISBN 1571812938, </ref> They claim that almost all returning POWs were convicted of collaboration and ] hence sentenced to forced labour.<ref name="MU"/><ref name="labor"> USHMM</ref><ref>Norman Davies, ''Europe: A History'', Oxford University Press, ISBN 0198201710, </ref><ref>Adam Hochschild, ''The Unquiet Ghost: Russians Remember Stalin'', Houghton Mifflin Books, 2003, ISBN 0618257470, </ref><ref>Francois Furet, ''The Passing of an Illusion: The Idea of Communism in the Twentieth Century'', University of Chicago Press, 1999, ISBN 0226273407, </ref><ref>Michael Parrish, ''The Lesser Terror: Soviet State Security, 1939-1953'', Greenwood Publishing Group, 1996, ISBN 0275951138 </ref><ref>Rosemary H. T. O'Kane, ''Paths to Democracy: Revolution and Totalitarianism'', Routledge, 2004, ISBN 0415314739, - "Nearly 80 per cent of were sent to forced labour, some given fifteen to twenty-five years of 'corrective labour', others sent off to hard labour; all were categorized as 'socially dangerous'."</ref> | |||

| Food for prisoners was extracted from the occupied Soviet Union after the occupiers' needs were met.{{sfn |Hartmann |2012|p=588}}{{sfn |Gerlach |2016|pp=225–226}} Prisoners usually received less than the official ration due to supply problems.{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=219}}{{sfn |Hartmann |2012|p=590}}{{sfn|Pohl|2012|pp=218–219}} By mid-August 1941, it had become clear that many prisoners would die.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=218}} The capture of nearly a million and a half million prisoners during the encirclements of ], ] in September and October caused a sudden breakdown in makeshift logistical arrangements.{{sfn |Hartmann |2012|pp=332, 589}} On 21 October 1941, OKH general quartermaster ] issued an order reducing daily rations for non-working prisoners to 1,487 ]s—a starvation amount that was rarely delivered. Working prisoners were also often put on starvation diets due to a lack of supplies.{{sfn |Hartmann |2012|p=590}}{{sfn|Quinkert|2021|p=191}} Non-working prisoners—all but one million of the 2.3 million held at the time—would die, as Wagner acknowledged at a November 1941 meeting.{{sfn |Hartmann |2012|p=590}}{{sfn|Pohl|2012|pp=218–219}} | |||

| Following setbacks in the military campaign, Hitler ordered on 31 October that labor deployment in Germany for surviving prisoners be prioritized.{{sfn|Keller|2021|p=198}}{{sfn |Gerlach |2016|p=226}} After this order was issued, death rates reached their apex;{{sfn |Gerlach |2016|p=226}} the need for prisoner labor could not overcome the other priorities for food distribution.{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=224}} The number of prisoners working declined as those deemed unfit for work or quarantined due to epidemics continued to increase.{{sfn|Keller|2021|p=199}} Although prisoners had not received much food from the beginning, death rates skyrocketed during the fall due to increased numbers, the cumulative effects of starvation, epidemics, and falling temperatures.{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=226}}{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=220}} Hundreds died daily at each camp, too many to bury.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=220}}{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=227}}{{sfn |Hartmann |2012|p=591}} German policy shifted to prioritize feeding prisoners at the expense of the Soviet civilian population but, in practice, conditions did not significantly improve until June 1942{{sfn|Pohl|2012|pp=219–220}} due to improved logistics and fewer prisoners to feed.{{sfn |Hartmann |2012|p=592}} Mass deaths were repeated on a smaller scale in the winter of 1942–1943.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=229}}{{sfn|Kay|2021|p=159}} | |||

| Thousands of prisoners indeed survived through collaboration, many of them joining German forces including the ]. Among the repressed were, however, even the universally acclaimed heroes of the war against ]. For example, ], who led the successful uprising in Sobibor death camp and then re-joined the Red Army where he was injured in combat and won a medal for bravery, but was later imprisoned in the Soviet Gulag anyway. | |||

| Starving prisoners attempted to eat leaves, grass, bark, and worms.{{sfn|Blank|Quinkert|2021|p=37}} Some Soviet prisoners suffered so much from hunger that they made written requests to their guards to be shot.{{sfn|Kay|2021|p=149}} ] was reported in several camps, despite capital punishment for this offense.{{sfn|Kay|2021|p=149}} Soviet civilians who tried to provide food were often shot.{{sfn|Blank|Quinkert|2021|p=35}}{{sfn|Moore|2022|pp=218–219}} In many camps, those who were in better condition were separated from prisoners deemed to have no chance of survival.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=222}} Employment could be beneficial in securing additional food and better conditions, although workers often received insufficient food{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=213}} and death rates exceeded 50 percent on some labor deployments.{{sfn|Keller|2021|p=199}} | |||

| ==Quotes== | |||

| ] | |||

| ===Release=== | |||

| "The war between Germany and Russia is not a war between two states or two armies, but between two ideologies–namely, the ] and the ] ideology. The Red Army must be looked upon not as a soldier in the sense of the word applying to our western opponents, but as an ideological enemy. He must be regarded as the archenemy of National Socialism and must be treated accordingly." -- General ] | |||

| On 7 August 1941, the OKW issued an order{{sfn|Quinkert|2021|p=187}} to release prisoners who were ], Latvian, Lithuanian, Estonian, Caucasian, and Ukrainian.{{sfn|Edele|2017|p=121}} The purpose of the release was largely to ensure that the harvest in German-occupied areas was successful.{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=223}} Red Army women were excluded from this policy.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=216}} Ethnic Russians, the vast majority of prisoners, were not considered for release, and about half of the Ukrainians were freed. Releases were curtailed due to epidemics and fear that they would join the partisans.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=216}} Some severely injured prisoners with family living nearby were released;{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=236}} many probably died of starvation soon afterwards.{{sfn|Cohen|2013|pp=107–108}} By January 1942, 280,108 prisoners of war—mostly Ukrainians—had been released, and the total number released was around a million by the end of the war.{{sfn|Edele|2017|pp=121–122}} In addition to agriculture, prisoners were released so that they could join ]. About one-third ], and others changed their status from prisoner to guard.{{sfn|Quinkert|2021|p=187}}{{sfn|Pohl|2012|pp=213, 216}}{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=223}} As the war progressed, release for agricultural work decreased and military recruitment increased.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=216}} | |||

| ===Selective killings=== | |||

| "This struggle has nothing to do with soldierly chivalry or the regulations of the ]." -- Field Marshal ] | |||

| ] crematorium with ] after local residents complained about gunfire.{{sfn|Kozlova|2021|pp=206–207}} ]] | |||

| <!-- ] (August 1941)]] --> | |||

| The selective killing of prisoners held by the army was enabled by its close cooperation with the SS and Soviet informers,{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=237}}{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=226}}{{sfn|Kozlova|2021|p=207}} and soldiers often conducted the executions.{{sfn|Kay|2021|p=167}} The killings targeted commissars and Jews,{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=231}}{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=226}} and sometimes communists, intellectuals,{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=226}}{{sfn|Kozlova|2021|p=206}} Red Army officers,{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=231}} and (in 1941) ] prisoners;{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=234}} about 80 percent of Turkic prisoners were killed by early 1942.{{sfn|Kay|2021|p=163}} German counterintelligence identified many individuals as Jews{{sfn|Kay|2021|p=161}} with medical examinations, denunciation by fellow prisoners, or a stereotypically Jewish appearance.{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=232}} | |||

| Beginning in August 1941, additional screening by the ] and the ] in the occupied Soviet Union led to the killing of another 38,000 prisoners.{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=231}} With the army's cooperation, {{lang|de|italic=no|]}} units visited the prisoner-of-war camps to carry out mass executions.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|pp=235–236}} About 50,000 Jewish Red Army soldiers were killed,{{sfn|Blank|Quinkert|2021|p=43}}{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=235}} but 5 to 25 percent escaped detection.{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=232}} Soviet Muslims mistaken for Jews were sometimes killed.{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=226}} From 1942, systematic killing increasingly targeted wounded and sick prisoners.{{sfn|Kay|2021|p=164}}{{sfn|Quinkert|2021|p=192}} Those unable to work were often shot in mass executions or left to die,{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=236}}{{sfn|Moore|2022|pp=243–244}} disabled soldiers were in particular danger when the ] approached. Sometimes mass executions were conducted without a clear rationale.{{sfn|Kay|2021|p=166}} | |||

| "Women in uniform are to be shot." -- Field Marshal ] | |||

| For the prisoner-of-war camps in Germany, screening was carried out by the Gestapo.{{sfn|Kozlova|2021|p=206}} Those highlighted for scrutiny were interrogated for about 20 minutes, often with ]. If their responses were unsatisfactory, they were stripped of prisoner-of-war status{{sfn|Kozlova|2021|p=207}} and brought to a concentration camp for execution, to conceal their fate from the German public.{{sfn|Kozlova|2021|p=207}}{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=226}} At least 33,000 prisoners were transferred to Nazi concentration camps—], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ].{{sfn|Otto|Keller|2019|p=13}} These killings dwarfed previous killings in the camp system.{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=226}} As the war progressed, increasing manpower shortages motivated the curtailment of executions.{{sfn|Kozlova|2021|p=210}} After March 1944, all Soviet officers and non-commissioned officers implicated in escape attempts were ]. These resulted in 5000 executions, including 500 officers who took part in an ] from Mauthausen.{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=253}} The death toll from direct executions, including the shooting of wounded soldiers, was probably hundreds of thousands.{{sfn|Kay|2021|p=167}} | |||

| "In the majority of cases, the camp commanders have forbidden the civilian population from putting food at the disposal of prisoners and they have rather let them starve to death." -- ] Minister of the Eastern Territories ] | |||

| ==Auxiliaries in German service == | |||

| "These cursed '']en'' have been observed eating grass, flowers and raw potatoes. Once they can't find anything edible in the camp they turn to cannibalism." -- Colonel Falkenberg, commandant of Stalag 318 (VIII-F) | |||

| {{further |Hiwi (volunteer)}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Hitler opposed recruiting Soviet collaborators for military and police functions, blaming non-German recruits for defeat in World War I.{{sfn|Edele|2017|pp=125–126}} Nevertheless, military leaders in the east disregarded his instructions and recruited such collaborators from the outset of the war; Himmler recognized in July 1941 that locally-recruited police would be necessary.{{sfn|Edele|2017|p=126}} The motivations of those who joined are not well known, although it is assumed that many joined to survive or improve their living conditions and others had ideological motives.{{sfn|Quinkert|2021|p=192}}{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=260}} A large proportion of those who survived being taken prisoner in 1941 did so because they collaborated with the Germans.{{sfn|Edele|2017|p=125}}{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=227}} Most had supporting roles such as drivers, cooks, grooms or translators; others were directly engaged in fighting, particularly during ].{{sfn|Edele|2017|p=126}}{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=223}} | |||

| A minority of captured prisoners of war{{sfn |Hartmann |2012|pp=575–576}} were reserved by each ] for forced labor in its operational area; these prisoners were not registered.{{sfn|Overmans|2022|p=7}} Their treatment varied, with some having living conditions similar to German soldiers and others being treated as badly as they were in the camps.{{sfn |Hartmann |2012|pp=577–578}} A smaller number joined dedicated military units with German officers, staffed by Soviet ethnic minorities.{{sfn|Moore|2022|pp=260–261, 263}} The first anti-partisan unit formed from Soviet prisoners of war was a ] unit which operated from July 1941.{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=223}} In 1943, there were 53 ]: fourteen in the ], nine in the ], eight each in the ] and ], and seven in the ] and ]s.{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=261}} | |||

| "The barbaric, Asiatic fighting methods are originated by the ]s. Action must therefore be taken against them immediately, without further consideration, and with all severity. Therefore, when they are picked up in battle or resistance, they are, as a matter of principle, to be finished immediately with a weapon." -- ''Guidelines for the Treatment of Political Commissars'', June 6, 1941<ref> ]</ref> | |||

| ], who were involved in the ] and other war crimes during the August 1944 ]]] | |||

| "Ruthless enforcement at the least sign of resistance and disobedience! Weapons are to be used mercilessly in breaking resistance. Escaping POWs must be fired upon immediately without warning, with intent to kill. Nor is softness called for against the industrious and obedient POW. He interprets it as weakness and draws his own conclusions." - ''Instructions for Guarding Soviet Prisoners of War'', September 1941<ref name="nomercy" /> | |||

| Along with those recruited by the German military, others were recruited by the SS to engage in genocide. The ] were recruited from prisoner-of-war camps; largely ethnic Ukrainians and Germans, they included Poles, Georgians, Armenians, Azerbaijanis, Tatars, Latvians, and Lithuanians. They helped suppress the 1943 ], worked in the ] that killed millions of Jews in ], and carried out anti-partisan operations.{{sfn|Edele|2017|pp=133–134}} Collaborators were essential to the German war effort and the Holocaust.{{sfn|Edele|2017|pp=134–135}} | |||

| If recaptured by the Red Army, collaborators were often shot.{{sfn|Edele|2017|p=137}} After the ] in early 1943, defections of collaborators back to the Soviet side increased; in response, Hitler ordered all Soviet military collaborators transferred to the ] late that year.{{sfn|Edele|2017|p=131}} By ] in mid-1944, these soldiers were 10 percent of the "German" forces occupying France.{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=263}} Some aided the resistance; in 1945, parts of the Georgian Legion ].{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=263}} Soviet prisoners of war were forced to work in construction and ] forces for the army, ], and ]. Prisoners of war were admitted into ] after April 1943, where they could be as much as 30 percent of their strength.{{sfn|Overmans|2022|pp=11, 13–15}}{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=245}} By the end of the war, 1.4 million prisoners of war (out of a total of 2.4 million) were serving in some kind of auxiliary military unit.{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=242}} | |||

| "We must break away from the principle of soldierly comradeship. The communist has been and will be no comrade. We are dealing with a struggle of annihilation." -- Adolf Hitler | |||

| ==Forced labor== | |||

| {{see also|Forced labour under German rule during World War II}} | |||

| Forced labor engaged in by Soviet prisoners of war often violated the ]. For example, the convention forbids work in war industries.{{sfn |Hartmann |2012|p=616}} | |||

| ===In the Soviet Union=== | |||

| ], Belarus, July 1941]] | |||

| Without the labor of Soviet prisoners of war for military infrastructure in the ]—building roads, bridges, airfields and train depots and converting the ] to the ]—the German offensive would soon have failed.{{sfn |Hartmann |2012|pp=616–617}} In September 1941, ] ordered the use of prisoners of war for ] and construction of infrastructure to free up ]s.{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=222}} Many prisoners ran away because of poor conditions in the camps (limiting forced-labor assignments),{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=222}} Others died: particularly deadly assignments included road-building projects (especially in ]),{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=213}}{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=202}} fortification-building on the ],{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=212}} and mining in the ] (authorized by Hitler in July 1942). About 48,000 were assigned to this task, but most never began their labor assignments and the remainder perished from the conditions or had escaped by March 1943.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|pp=213–214}} | |||

| ===Transfer to Nazi concentration camps=== | |||

| ], to which at least 15,000 were deported{{sfn|Otto|Keller|2019|p=13}}]] | |||

| In September 1941, Himmler began advocating for the transfer of 100,000, then 200,000{{sfn|Wachsmann|2015|p=278}} Soviet prisoners of war for forced labor in Nazi concentration camps under the control of the SS; the camps previously held 80,000 people.{{sfn|Wachsmann|2015|p=280}} By October, segregated areas designated for prisoners of war had been established at Neuengamme, Buchenwald, Flossenbürg, Gross-Rosen, Sachsenhausen, Dachau, and Mauthausen by clearing prisoners from existing barracks or building new ones.{{sfn|Wachsmann|2015|p=278}} Most of the incoming prisoners were planned to be imprisoned in two new camps established in German-occupied Poland, ] and ], as part of Himmler's colonization plans.{{sfn|Wachsmann|2015|pp=278–279}}{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=229}} | |||

| Despite the intention to exploit their labor, most of the 25,000{{sfn|Otto|Keller|2019|p=12}} or 30,000 who arrived in late 1941{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=230}}{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=230}} were in poor condition and incapable of work.{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=230}}{{sfn|Wachsmann|2015|p=282}} Kept in worse conditions and provided less food than other prisoners, they had a higher mortality rate; 80 percent were dead by February 1942.{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=230}}{{sfn|Wachsmann|2015|p=282}} The SS killed politically-suspect, sick, and weak prisoners individually, and carried out mass executions in response to infectious-disease outbreaks.{{sfn|Wachsmann|2015|p=283}} Experimental execution techniques were tested on prisoners of war: ] at Sachsenhausen and ] in gas chambers at Auschwitz.{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=223}}{{sfn|Wachsmann|2015|p=269}} So many died at Auschwitz that its crematoria were overloaded; the SS began ] in November 1941 to keep track of which prisoners had died.{{sfn|Wachsmann|2015|p=284}}{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=229}} Contrary to Himmler's assumption, more Soviet prisoners of war did not replace those who died. As the capture of Red Army soldiers dropped off, Hitler decided at the end of October 1941 to deploy the remaining prisoners in the German war economy.{{sfn|Wachsmann|2015|p=285}}{{sfn|Moore|2022|pp=230–231}} | |||

| In addition to those sent for labor in late 1941,{{sfn|Kozlova|2021|p=222}} others were recaptured after escapes or arrested for offenses such as ], insubordination, refusal to work,{{sfn|Kay|2021|p=166}}{{sfn|Kozlova|2021|p=221}} and suspected resistance activities or ] or were expelled from collaborationist military units.{{sfn|Otto|Keller|2019|p=13}} Red Army women were often pressured to renounce their prisoner-of-war status to be transferred to civilian forced-labor programs. Some refused, and were sent to concentration camps. About 1,000 were imprisoned at ], and others at Auschwitz, Majdanek, and Mauthausen.{{sfn|Kozlova|2021|pp=221–222}} Those imprisoned in concentration camps for an infraction lost their prisoner-of-war status, in violation of the Geneva Convention.{{sfn|Kozlova|2021|p=219}} Officers were over-represented{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=232}} among the more than 100,000 men and an unknown number of women who were transferred to Nazi concentration camps.{{sfn|Kay|2021|p=165}}{{sfn|Kozlova|2021|p=222}}{{sfn|Otto|Keller|2019|p=13}} | |||

| ===Deportation elsewhere=== | |||

| ], Norway, after liberation]] | |||

| In July and August 1941, 200,000 Soviet prisoners of war were deported to Germany to fill the labor demands of agriculture and industry.{{sfn|Keller|2021|p=204}}{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=231}} The deportees faced conditions similar to those in the occupied Soviet Union.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=214}} Hitler halted the transports in mid-August, but changed his mind on 31 October;{{sfn|Moore|2022|pp=231, 233}} along with the prisoners of war, a larger number of Soviet civilians were sent.{{sfn|Keller|2021|p=204}}{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=228}} The camps in Germany had an internal police force of non-Russian prisoners who were often violent towards Russians; Soviet Germans often staffed the camp administration, and were interpreters. Both groups received more rations and preferential treatment.{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=245}} Guarding the prisoners was the responsibility of the army's {{ill|Landesschützen|de|Landesschützen (Deutsches Reich)|lt=units of German men too elderly or infirm to serve at the front}}.{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=248}} | |||

| Many Nazi leaders wanted to avoid contact between Germans and prisoners of war, limiting work assignments for prisoners.{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=232}} Labor assignments differed in accordance with the local economy. Many worked for private employers in agriculture and industry, and others were rented to local authorities for such tasks as building roads and canals, quarrying, and cutting peat.{{sfn|Moore|2022|pp=244–245}} Employers paid ]0.54{{efn|Approximately 13 cents in contemporary United States dollars,{{sfn|Foreign Claims Settlement Commission|1968|p=655}} or USD${{formatnum:{{Inflation|US|.13|1942|r=0}}}} today.{{sfn| Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis|2019}}}} per day per man for agricultural work, and RM0.80{{efn|Approximately 20 cents in contemporary United States dollars,{{sfn|Foreign Claims Settlement Commission|1968|p=655}} or USD${{formatnum:{{Inflation|US|.2|1942|r=0}}}} today.{{sfn| Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis|2019}}}} for other work; many also provided prisoners with extra food to achieve productivity. Workers received RM0.20{{efn|Approximately 5 cents in contemporary United States dollars,{{sfn|Foreign Claims Settlement Commission|1968|p=655}} or USD${{formatnum:{{Inflation|US|.05|1942|r=0}}}} today.{{sfn| Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis|2019}}}} per day in {{ill|Lagergeld|de|lt=currency that could be spent at the camp}}.{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=249}} By early 1942, to combat the fact that many prisoners were too malnourished to work, some surviving prisoners were granted increased rations{{sfn|Moore|2022|pp=244–245}} although significant improvement was politically impossible because supply shortages necessitated a reduction in rations to German citizens.{{sfn|Tooze |2008|p=542}} Prisoners remained vulnerable to malnutrition and disease.{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=246}} The number of prisoners working in Germany continued to increase, from 455,000 in September 1942 to 652,000 in May 1944.{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=243}} By the end of the war, at least 1.3 million Soviet prisoners of war had been deported to Germany or its annexed territories.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=215}} Of these, 400,000 did not survive; most of the deaths occurred in the winter of 1941–1942.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=215}} Others were deported to other locations, including Norway and the ].{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=254}} | |||

| ==Public perception== | |||

| ] head ] inspects a prison camp in Minsk, 15 August 1941.]] | |||

| According to ], many Germans worried about food shortages and wanted Soviet prisoners to be killed or given minimal food for this reason.{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|pp=180, 234}} ] portrayed Soviet prisoners of war as murderers,{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=225}} and photographs of cannibalism in prisoner-of-war camps were seen as proof of "Russian ]".{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=221}} Although ], many Germans were aware of the large number of Soviet prisoners of war who died before most ].{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=233}} | |||

| ] began integrating the atrocities against Soviet prisoners of war as early as July 1941. Information about the Commissar Order, described as mandating the killing of all officers or prisoners captured, was disseminated to Red Army soldiers.{{sfn|Edele|2016|p=368}} Accurate information about the treatment of Soviet prisoners of war reached Red Army soldiers by various means—such as escapees and other eyewitnesses—and was an effective deterrent against defection{{sfn|Edele|2017|pp=51–52, 54}} although many disbelieved the official propaganda.{{sfn|Edele|2017|p=55}} | |||

| ==End of the war== | |||

| ].{{sfn|Blank|Quinkert|2021|p=73}}]] | |||

| ]{{sfn|Blank|Quinkert|2021|p=75}}]] | |||

| About 500,000 prisoners had been freed by the Red Army by February 1945.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=201}} During its advance, the Red Army found mass graves at former prisoner-of-war camps.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=222}} In the war's final months, most of the remaining Soviet prisoners were forced on ]{{sfn|Blank|Quinkert|2021|p=71}} similar to those of concentration-camp prisoners.{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=223}} Many were killed during these marches or died from illness after liberation.{{sfn|Blank|Quinkert|2021|pp=71, 75}} They returned to a country which had lost millions of people to the war and had its infrastructure destroyed by German Army ] tactics. For years afterwards the Soviet population experienced food shortages.{{sfn|Blank|Quinkert|2021|pp=77, 80}} Former prisoners of war were among the 451,000 or more Soviet citizens who avoided repatriation and remained in Germany or emigrated to Western countries after the war.{{sfn|Edele|2017|p=144}} Due to its clear-cut criminality, the treatment of Soviet prisoners of war was mentioned in the ]'s indictment.{{sfn|Hartmann |2012|p=569}} | |||

| Soviet policy, intended to discourage defection, held that any soldier who fell into enemy hands was a traitor.{{sfn|Edele|2017|p=41}} Issued in August 1941, {{awrap|]}} classified surrendering commanders and political officers ] to be summarily executed and their families arrested.{{sfn|Edele|2017|p=41}}{{sfn|Moore|2022|pp=381–382}} Sometimes Red Army soldiers were told that the families of defectors would be shot; although thousands were arrested, it is unknown if any such executions were carried out.{{sfn|Edele|2017|pp=42–43}} As the war continued, Soviet leaders realized that most of their citizens had not voluntarily collaborated.{{sfn|Edele|2017|p=140}} In November 1944, the ] decided that freed prisoners of war would be returned to the army; those who served in German military units or the police would be handed over to the ].{{sfn|Blank|Quinkert|2021|p=85}} At the ], the Western Allies agreed to repatriate Soviet citizens regardless of their wishes.{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=388}} | |||

| In an attempt to separate the minority of voluntary collaborators, freed prisoners of war were sent to ], hospitals, and recuperation centers, where most stayed for one or two months.{{sfn|Moore|2022|pp=384–385}} This process was not effective in separating the minority of voluntary collaborators,{{sfn|Edele|2017|p=140}} and most defectors and collaborators escaped prosecution.{{sfn|Edele|2017|p=141}} Trawniki men were typically sentenced to 10 to 25 years in a labor camp, and military collaborators often received six-year sentences in ].{{sfn|Edele|2017|p=143}} According to official statistics, 57.8 percent returned home, 19.1 percent were remobilized, 14.5 percent were enlisted in the labor battalions of the ], and 6.5 percent were transferred to the NKVD.{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=394}} According to another estimate, of 1.5 million returnees by March 1946, 43 percent continued their military service, 22 percent were drafted into labor battalions for two years, 18 percent were sent home, 15 percent were sent to a forced-labor camp, and two percent worked for repatriation commissions. ] were rare.{{sfn|Blank|Quinkert|2021|p=79}} On 7 July 1945, a ] decree pardoned all former prisoners of war who had not collaborated.{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=394}} Another amnesty in 1955 released all remaining collaborators except those sentenced for torture or murder.{{sfn|Edele|2017|p=141}} | |||

| Former prisoners of war were not recognized as veterans and were denied ]; they often faced discrimination due to the belief that they were traitors or deserters.{{sfn|Blank|Quinkert|2021|p=79}}{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=394}} In 1995, Russia equalized the status of former prisoners of war with that of other veterans.{{sfn|Latyschew|2021|p=252}} After the fall of the Eastern Bloc, the German government set up the ] to distribute further reparations, from which Soviet prisoners of war were not eligible to make claims.{{sfn|Meier|Winkel|2021|p=230}} They did not receive any ] until 2015, when the German government paid a symbolic amount of 2,500 ] to the few thousand still alive.{{sfn|Blank|Quinkert|2021|pp=87, 89}}<ref>{{cite web |title=Entschädigung? |trans-title=Compensation? |url=https://unrecht-erinnern.info/themen/entschaedigung-und-unterstuetzung/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240412171222/https://unrecht-erinnern.info/themen/entschaedigung-und-unterstuetzung/ |archive-date=12 April 2024 |access-date=5 September 2024 |website=An Unrecht Erinnern |language=de}}</ref> | |||

| ==Death toll== | |||

| {{see also|World War II casualties of the Soviet Union}} | |||

| ], German-occupied Poland]] | |||

| The German Army recorded 3.35 million Soviet prisoners captured in 1941, which exceeds the Red Army's reported missing by up to one million. This discrepancy can be partly explained by the Red Army's inability to keep track of losses during a chaotic withdrawal. Additionally,{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=214}} as many as one in eight of the people registered as Soviet prisoners of war had never been members of the Red Army. Some were mobilized, but never reached their units; others belonged to the ] or ], were from uniformed civilian services such as the railway corps and fortification workers, or were otherwise civilians.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=202}} Historian ] says that the German figures represent a minimum value,{{sfn|Zemskov|2013|p=103}} and should be adjusted upwards by 450,000 to account for prisoners who were killed before arriving in a camp.{{sfn|Zemskov|2013|p=104}} Zemskov estimates around 3.9 million dead out of 6.2 million captured, including 200,000 killed as military collaborators.{{sfn|Zemskov|2013|p=107}} Other historians, working from the German figure of 5.7 million captured,{{sfn|Zemskov|2013|p=103}} have reached lower estimates: ]'s 3.3 million,{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|pp=229–230}} ]'s 3 million,{{sfn|Hartmann|2012|p=789}} and ]'s 2.8 to 3 million.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=240}} | |||

| A majority of the deaths, about two million, occurred before January 1942.{{sfn|Kay|2021|p=154}}{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=230}} The death rate of 300,000 to 500,000 each month from October 1941 to January 1942 is one of the highest death rates from mass atrocity in history, equaling the peak ] between ].{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|pp=226–227}} By this time, more Soviet prisoners of war had died than members of any other group targeted by the Nazis;{{sfn|Quinkert|2021|p=172}}{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=72}}{{sfn|Kay|2021|p=153}} only the European Jews would surpass this figure.{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=5}}{{sfn|Kay|2021|p=294}} An additional one million Soviet prisoners of war died after the beginning of 1942—27 percent of the total number of prisoners alive or captured after that date.{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=230}}{{sfn|Quinkert|2021|p=192}} | |||

| Most of the Soviet prisoners of war who died did so in the custody of the German Army.{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|pp=72, 125}}{{sfn|Hartmann|2012|p=568}} More than two million died in the Soviet Union; about 500,000, in the ] (Poland); 400,000, in Germany; and 13,000, in ].{{sfn|Blank|Quinkert|2021|p=121}}{{sfn|Kay|2021|p=167}}{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=230}} More than 28 percent of Soviet prisoners of war died ];{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|pp=236, 400}} and 15 to 30 percent of Axis prisoners died in Soviet custody, despite the Soviet government's attempt to reduce the death rate.{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=237}}{{sfn|Edele|2016|p=375}} Throughout the war, Soviet prisoners of war had a far higher mortality rate than Polish or Soviet civilian forced laborers, whose rate was under 10 percent.{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=230}} | |||

| While the Germans committed ],<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Scheck |first=Raffael |date=July 2021 |title=The treatment of western prisoners of war in Nazi Germany: Rethinking reciprocity and asymmetry |url=https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0968344520913577 |journal=War in History |language=en |volume=28 |issue=3 |pages=635–655 |doi=10.1177/0968344520913577 |issn=0968-3445}}</ref> the total number of the deaths of prisoners of war from the Soviet Union greatly exceeded deaths of prisoners from other nationalities.{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|pp=235–236}}{{sfn|Moore|2022|p=204}} With regards to the mortality rate, it is estimated at forty three to as high as sixty three percent.{{sfn|Edele|2016|p=375}} The second highest mortality rate of prisoners in German captivity was that of ] (six to seven percent);{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|pp=235–236}} while in the entire war, another high mortality rate was that of ] (twenty seven percent).{{sfn|Edele|2016|p=376}} The death rate of ] has also been high; it has been estimated at 15% by Mark Edele,{{sfn|Edele|2016|p=375}} and at 35.8% by ].<ref name="Ferguson2004">{{cite journal |last1=Ferguson |first1=Niall |year=2004 |title=Prisoner Taking and Prisoner Killing in the Age of Total War: Towards a Political Economy of Military Defeat |journal=War in History |volume=11 |issue=2 |pages=148–92 |doi=10.1191/0968344504wh291oa |s2cid=159610355}}</ref>{{Rp|page=375}} | |||

| ==Legacy and historiography== | |||

| ], Latvia]]Hartmann calls the treatment of Soviet prisoners "one of the greatest crimes in ]".{{sfn|Hartmann|2012|p=568}}<!-- alternately "one of the greatest war crimes committed in the twentieth century" {{sfn|Moore|2022|p=204}} --> Thousands of books have been published about the Holocaust, but in 2016 there were no books in English about the fate of Soviet prisoners of war.{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=5}} The issue was also mostly ignored by ] until the last years of the USSR.{{sfn|Moore|2022|pp=7–8}} Few prisoner accounts were published, perpetrators were not tried for their crimes, and little scholarly research has been attempted.{{sfn|Gerlach|2016|p=224}}{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=221}} The German historian Christian Streit published ] of their fate in 1978,{{sfn|Meier|Winkel|2021|p=230}} and the Soviet archives became available in 1990.{{sfn|Latyschew|2021|p=252}} Prisoners who remained in the occupied Soviet Union usually were not registered under their names, so their fates will never be known.{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=229}} | |||

| Although the treatment of prisoners of war was remembered by Soviet citizens as one of the worst aspects of the occupation,{{sfn|Pohl|2012|p=242}} Soviet commemoration of the war focused on ] and those killed in combat.{{sfn|Blank|Quinkert|2021|p=87}} Contemporary Soviet leaders, including Stalin, considered Soviet soldiers who surrendered to be traitors, and ] noted that some of "those who survived German captivity to 1945 were promptly sent to the ]".<ref>{{Cite journal |last=MacKenzie |first=S. P. |date=September 1994 |title=The Treatment of Prisoners of War in World War II |url=https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/244883 |journal=The Journal of Modern History |language=en |volume=66 |issue=3 |pages=487–520 |doi=10.1086/244883 |issn=0022-2801}}</ref> Bob Moore likewise noted that "the survivors were victimized and ostracized on their return—their sufferings and mortality forgotten"; ].{{sfn|Moore|2022|pp=7–8, 15}} During {{lang|ru|]}} in 1987 and 1988, a debate erupted in the Soviet Union about whether the former prisoners of war had been traitors; those arguing in the negative prevailed after the ].{{sfn|Edele|2017|p=160}} ] historiography defended the former prisoners, minimizing incidents of defection and collaboration and emphasizing resistance.{{sfn|Edele|2017|pp=161–162}} | |||

| The fate of Soviet prisoners of war was largely ignored in ] and ], where ] were a focus.{{sfn|Blank|Quinkert|2021|p=87}} After the war, there were some German attempts to deflect the blame for the 1941 mass deaths. Some blamed the deaths on the failure of diplomacy between the Soviet Union and Germany after the invasion, or on prior starvation of soldiers by the Soviet government.{{sfn|Moore|2022|pp=237–238}} Crimes against prisoners of war were exposed to the German public in the ] around 2000, which challenged the ].{{sfn|Meier|Winkel|2021|pp=229–230}}{{sfn|Otto|Keller|2019|p=17}} Memorials and markers have been established at cemeteries and former camps by state or private initiatives.{{sfn|Blank|Quinkert|2021|p=125}} For the 80th anniversary of World War II, several German historical and memorial organizations organized a traveling exhibition.{{sfn|Blank|Quinkert|2021|p=4}} | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| {{notelist}} | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| *] | |||

| *] - Soviet POWs among victims (70,000-120,000 people executed between 1941 and 1943). | |||

| *] - Execution of some 7,500 Soviet POWs in 1941 (among about 100,000 murdered there between 1941 and 1944). | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{ |

{{Reflist|20em}} | ||

| ==Works cited== | |||

| {{refbegin|40em|indent=yes}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Bartov |first1=Omer |author1-link=Omer Bartov |title=The Oxford History of the Third Reich |date=2023 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-19-288683-5 |pages=190–216 |language=en |chapter=The Holocaust |editor1-first=Robert |editor1-last=Gellately |editor1-link=Robert Gellately |doi=10.1093/oso/9780192886835.003.0008}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Beorn |first1=Waitman Wade |author1-link=Waitman Wade Beorn |title=The Holocaust in Eastern Europe: At the Epicenter of the Final Solution |date=2018 |publisher=] |isbn=978-1-4742-3219-7 |language=en}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Blank |first1=Margot |last2=Quinkert |first2=Babette |title=Dimensionen eines Verbrechens: Sowjetische Kriegsgefangene im Zweiten Weltkrieg <nowiki>|</nowiki> Dimensions of a Crime. Soviet Prisoners of War in World War II |date=2021 |publisher=Metropol Verlag |isbn= 978-3-86331-582-5 |language=de, en}} | |||

| ** {{harvc |last1=Quinkert |first1=Babette |c=Captured Red Army soldiers in the context of the criminal conduct of the war against the Soviet Union |pages=172–193 |in1=Blank |in2=Quinkert |year=2021}} | |||

| ** {{harvc |last1=Keller |first1=Rolf |authorlink=:de:Rolf Keller (Historiker) |c="...A necessary evil": use of Soviet prisoners of war as labourers in the German Reich, 1941–1945 |pages=194–205 |in1=Blank |in2=Quinkert |year=2021}} | |||

| ** {{harvc |last1=Kozlova |first1=Daria |c=Soviet prisoners of war in the concentration camps |pages=206–223 |in1=Blank |in2=Quinkert |year=2021}} | |||

| ** {{harvc |last1=Meier |first1=Esther|last2=Winkel |first2=Heike |c=Unpleasant memories. Soviet prisoners of war in collective memory, in Germany and the Soviet Union / Russia |pages=224–239 |in1=Blank |in2=Quinkert |year=2021}} | |||

| ** {{harvc |last1=Latyschew |first1=Artem |chapter=History of oblivion, recognition and study of former prisoners of war in the USSR and Russia |pages=240–257 |in1=Blank |in2=Quinkert |year=2021}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Cohen |first1=Laurie R. |title=Smolensk Under the Nazis: Everyday Life in Occupied Russia |date=2013 |publisher=Boydell & Brewer |isbn=978-1-58046-469-7 |language=en}} | |||

| * {{cite web |title=Consumer Price Index, 1800– |url=https://www.minneapolisfed.org/about-us/monetary-policy/inflation-calculator/consumer-price-index-1800- |publisher=Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis |access-date=29 November 2019 |ref={{sfnref|Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis|2019}} |url-status=live |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20240829053558/https://www.minneapolisfed.org/about-us/monetary-policy/inflation-calculator/consumer-price-index-1800- |archive-date=29 August 2024}} | |||

| * {{cite journal |last1=Edele |first1=Mark |author1-link=Mark Edele |title=Take (No) Prisoners! The Red Army and German POWs, 1941–1943 |journal=] |date=2016 |volume=88 |issue=2 |pages=342–379 |doi=10.1086/686155 |hdl=11343/238858 |s2cid=<!-- --> |hdl-access=free |jstor=26547940}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Edele |first1=Mark|author1-link=Mark Edele |title=Stalin's Defectors: How Red Army Soldiers became Hitler's Collaborators, 1941–1945 |date=2017 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-19-251914-6 |language=en |doi=10.1093/oso/9780198798156.001.0001}} | |||