| Revision as of 21:57, 23 June 2008 editBerks911 (talk | contribs)131 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 14:28, 18 December 2024 edit undo85.18.219.136 (talk) →Post-Government of National Unity: 2013–present | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|none}} | |||

| {{Infobox Economy | |||

| {{Infobox economy | |||

| |country = Zimbabwe | |||

| | country = Zimbabwe | |||

| |image= | |||

| | image = Harare secondst.jpg | |||

| |width= | |||

| | caption = ] in ] | |||

| |caption= | |||

| |currency=] |

| currency = ] | ||

| |year=calendar year | | year = calendar year | ||

| | organs = ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| |organs=] | |||

| | group = {{plainlist| | |||

| |rank=104th (IMF); 149th (CIA); 127th (WB) | |||

| *]<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2019/01/weodata/weoselco.aspx?g=2200&sg=All+countries+%2f+Emerging+market+and+developing+economies |title=World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019 |publisher=] |website=IMF.org |access-date=29 September 2019 |archive-date=10 October 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201010203013/https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2019/01/weodata/weoselco.aspx?g=2200&sg=All+countries+%2F+Emerging+market+and+developing+economies |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| |gdp=USD $28.098 billion (2007) (IMF); USD $6.186 billion (2007) (CIA+WB) | |||

| *Lower-middle income economy<ref>{{cite web |url=https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups |title=World Bank Country and Lending Groups |publisher=] |website=datahelpdesk.worldbank.org |access-date=29 September 2019 |archive-date=28 October 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191028223324/https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups |url-status=live }}</ref>}} | |||

| |growth=-5.7% (2007) -3.6% (2008) (IMF est.) | |||

| | population = {{increase}} 16,942,006 (April 11, 2024 est)<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/zimbabwe-population/ |title=Zimbabwe Population(Live) |publisher=]}}</ref> | |||

| |per capita=USD $500 (2007 est.) | |||

| | gdp = {{plainlist| | |||

| |sectors=Agriculture: 16.7%, Industry: 21.6%, Services: 61.6% (2007) | |||

| *{{increase}} $47.08 billion (nominal, 2023 est.)<ref name="imf.org">{{Cite web|url=https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/profile/ZWE |title=Zimbabwe Datasets |publisher=]}}</ref> | |||

| |inflation= 732,604% (CSO (not officially released) - Apr 2008) ; | |||

| *{{increase}} $66.0 billion (], 2023 est.)<ref>{{Cite web |date=2023-11-21 |title=Zim GDP Set To Reach US$66 Billion |url=https://technomag.co.zw/zim-gdp-set-to-reach-us66-billion/ |access-date=2024-01-17 |website=TechnoMag |language=en-US}}</ref>}} | |||

| unofficial est. 1,700,000% (May 2008) | |||

| | gdp rank = {{plainlist| | |||

| |poverty=80% earn below ZWD 4 Billion per month (USD $50.00) (Apr 2008) | |||

| *] | |||

| *]}} | |||

| |gini=50.1% (1995) 56.8% (2003) | |||

| | growth = {{plainlist| | |||

| |labor=4.23 million (2004 est.) | |||

| *5.3% (2021) | |||

| |occupations=Agriculture: 60%, Services: 9%, Wholesale, Retail, Hotels, Restaurants: ~4%, Manufacturing: 4%, Mining: 3% (2003) | |||

| *4.5% (2022)<ref name="imf.org"/> | |||

| |unemployment=80% (2005 to 2008 est.) | |||

| *5.3% (2023e) | |||

| |industries=mining (], ], ], ], ], ], ], numerous metallic and nonmetallic ]), ]; wood products, ], chemicals, fertilizer, clothing and footwear, foodstuffs, beverages | |||

| *5.2% (2024e) | |||

| |exports=USD $1.775 billion (2006 est.) | |||

| <ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.newsday.co.zw/theindependent/amp/business-digest/article/200016992/2024-budget-strategy-paper-zims-future-looks-bleak | title=2024 budget strategy paper: Zim's future looks bleak }}</ref>}} | |||

| |export-goods=Cotton, tobacco, gold, ferroalloys, textiles/clothing | |||

| | per capita = {{plainlist| | |||

| |export-partners=South Africa 36.4%, (China, Japan, Zambia) 7.3% each, Mozambique 4.7%, (US, Botswana, Italy, Germany, Netherlands) 3.6% each (2006) | |||

| *{{increase}} $2,860 (nominal, 2023 est.)<ref name="imf.org"/> | |||

| |imports=USD $2.059 billion (2005 est.) f.o.b. | |||

| *{{increase}} $3,928 (PPP, 2023 est.)<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.herald.co.zw/zim-gdp-hits-us66bn/amp/ | title=Zim GDP hits US$66bn – the Herald }}</ref>}} | |||

| |import-goods=machinery and transport equipment, other manufactures, chemicals, fuels | |||

| | per capita rank = {{plainlist| | |||

| |import-partners = South Africa 43%, China 4.6%, Botswana 3.3% (2005) | |||

| *] | |||

| |debt=Domestic: ZWD $60.8 trillion (rev) (01 Feb 2008), $1.353 quadrillion (rev) (29 Feb 2008) . International: USD $5.2 billion (September 2006) | |||

| *]}} | |||

| |revenue=ZWD $216 billion (rev) (2006) | |||

| | sectors = {{plainlist| | |||

| |expenses=ZWD $451 billion (rev) (2006) | |||

| *]: 12% | |||

| |aid=''recipient'': $178 million; note - the EU and the US provide food aid on humanitarian grounds (2000 est.) | |||

| *]: 22.2% | |||

| |cianame=zi | |||

| *]: 65.8% | |||

| *(2017 est.)<ref name="CIAWFZI">{{cite web |url=https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/zimbabwe/ |title=The World Factbook |publisher=] |website=CIA.gov |access-date=7 July 2019 |archive-date=26 January 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210126032849/https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/zimbabwe/ |url-status=live }}</ref>}} | |||

| | inflation = 172.2% (2023 est.)<ref name="imf.org"/> | |||

| | poverty = {{plainlist| | |||

| *1.0% (2017)<ref>{{cite web |title=Poverty headcount ratio at national poverty lines (% of population) – Zimbabwe |url=https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.NAHC?locations=ZW |website=data.worldbank.org |publisher=World Bank |access-date=21 March 2020 |archive-date=30 November 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201130143344/https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.NAHC?locations=ZW |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| *1.0% on less than $3.20/day (2017)<ref>{{cite web |url=https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.LMIC?locations=ZW |title=Poverty headcount ratio at $3.20 a day (2011 PPP) (% of population) – Zimbabwe |publisher=] |website=data.worldbank.org |access-date=21 March 2020 |archive-date=4 December 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191204233506/https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.LMIC%3Flocations%3DZW |url-status=live }}</ref>}} | |||

| | hdi = {{plainlist| | |||

| *{{increase}} 0.563 {{color|darkorange|medium}} (2018)<ref>{{cite web |url=http://hdr.undp.org/en/indicators/137506 |title=Human Development Index (HDI) |publisher=] ] |website=hdr.undp.org |access-date=11 December 2019 |archive-date=27 June 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160627101948/http://hdr.undp.org/en/indicators/137506 |url-status=live }}</ref> (]) | |||

| *0.435 {{color|red|low}} ] (2018)<ref>{{cite web |url=http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/table-3-inequality-adjusted-human-development-index-ihdi |title=Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI) |publisher=] ] |website=hdr.undp.org |access-date=11 December 2019 |archive-date=12 December 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201212055527/http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/table-3-inequality-adjusted-human-development-index-ihdi |url-status=live }}</ref>}} | |||

| | gini = 44.3 {{color|darkorange|medium}} (2017)<ref>{{cite web |title=GINI index (World Bank estimate) – Zimbabwe |url=https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?locations=ZW |website=data.worldbank.org |publisher=World Bank |access-date=21 March 2020 |archive-date=31 July 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200731022158/https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?locations=ZW |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| | edbr = {{increase}} ]<ref name="World Bank and International Financial Corporation">{{cite web |url=http://www.doingbusiness.org/data/exploreeconomies/zimbabwe |title=Ease of Doing Business in Zimbabwe |publisher=Doingbusiness.org |access-date=2017-01-23 |archive-date=2017-02-06 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170206233511/http://www.doingbusiness.org/data/exploreeconomies/zimbabwe/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| | labor = {{plainlist| | |||

| *{{increase}} 6,560,725 (2023)<ref>{{cite web |url=https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.TOTL.IN?locations=ZW |title=Labor force, total – Zimbabwe |publisher=] |website=data.worldbank.org |access-date=4 December 2019 |archive-date=1 August 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200801044859/https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.TOTL.IN?locations=ZW |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| *58.6% employment rate (2022)<ref>{{cite web |url=https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.EMP.TOTL.SP.NE.ZS?locations=ZW |title=Employment to population ratio, 15+, total (%) (national estimate) – Zimbabwe |publisher=] |website=data.worldbank.org |access-date=4 December 2019 |archive-date=4 December 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191204233458/https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.EMP.TOTL.SP.NE.ZS%3Flocations%3DZW |url-status=live }}</ref>}} | |||

| | occupations = {{plainlist| | |||

| *]: 67.5% | |||

| *]: 7.3% | |||

| *]: 25.2% | |||

| *(2017 est.)<ref name="CIAWFZI"/>}} | |||

| | unemployment = {{plainlist| | |||

| *11.3% (2014 est.)<ref name="CIAWFZI"/> | |||

| *data include both unemployment and underemployment; true unemployment is unknown and, under current economic conditions, unknowable<ref name="CIAWFZI"/>}} | |||

| | industries = mining (], ], ], ], ], ], ], numerous metallic and non-metallic ]s), ]; wood products, ], ], ], ] and ], ]s, ]s, ], ] | |||

| | exports = {{increase}} $6.59 billion (2022 est.)<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.statista.com/statistics/455344/export-of-goods-to-zimbabwe/ | title=Zimbabwe - export of goods 2012-2022 }}</ref> | |||

| | export-goods = ], ], ], ], ], ]/] | |||

| | export-partners = {{plainlist| | |||

| *{{flag|South Africa}}(+) 41.0% | |||

| *{{flag|United Arab Emirates}}(+) 32.0% | |||

| *{{flag|China}}(+) 8.86% | |||

| *{{flag|Belgium}}(+) 3.26% | |||

| *{{flag|Mozambique}}(+) 2.89% | |||

| *(2022)<ref>{{cite web | url=https://trendeconomy.com/data/h2/Zimbabwe/TOTAL | title=Zimbabwe | Imports and Exports | World | ALL COMMODITIES | Value (US$) and Value Growth, YoY (%) | 2011 - 2022 | date=28 January 2024 }}</ref>}} | |||

| | imports = {{increase}} $8.68 billion (2022 est.)<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.statista.com/statistics/455339/import-of-goods-to-zimbabwe/#:~:text=In%202022%2C%20goods%20worth%20around,dollars%20were%20imported%20to%20Zimbabwe. | title=Zimbabwe - import of goods 2012-2022 }}</ref> | |||

| | import-goods = ] and transport equipment, other manufactures, ], ], food products | |||

| | import-partners = {{plainlist| | |||

| *{{flag|South Africa}}(+) 40.0% | |||

| *{{flag|China}}(+) 13.9% | |||

| *{{flag|Singapore}}(+) 13.6% | |||

| *(2022)<ref>{{cite web | url=https://trendeconomy.com/data/h2/Zimbabwe/TOTAL#:~:text=Zimbabwe%27s%20imports%202022%20by%20country&text=South%20Africa%20with%20a%20share%20of%2040%25%20(3.47%20billion%20US,3.84%25%20(331%20million%20US%24) | title=Zimbabwe | Imports and Exports | World | ALL COMMODITIES | Value (US$) and Value Growth, YoY (%) | 2011 - 2022 | date=28 January 2024 }}</ref>}} | |||

| | current account = {{decrease}} −$716 million (2017 est.)<ref name="CIAWFZI"/> | |||

| | FDI = {{plainlist| | |||

| *{{increase}} $3.86 billion (31 December 2017 est.)<ref name="CIAWFZI"/> | |||

| *{{increase}} Abroad: $309.6 million (31 December 2017 est.)<ref name="CIAWFZI"/>}} | |||

| | gross external debt = {{increaseNegative}} $14.01 billion (23 February 2023)<ref>{{cite web | |||

| |title= Zimbabwe committed to debt reduction | |||

| |url=https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/zimbabwe-committed-debt-arrears-clearance-president-says-2023-02-23/#:~:text=Zimbabwe%2C%20which%20had%20more%20than,decades%2C%20due%20to%20its%20arrears. | |||

| |website=www.reuters.com}}</ref> | |||

| | debt = {{decreasePositive}} 58.47% of GDP (2022 est.) | |||

| | revenue = *ZWL58.2 trillion (proposed for 2024) | |||

| *US$10.0 billion (official rate $1:5,790 (Nov 2023)) | |||

| *US$6.26 billion (parallel market $1:9,300 (Nov 2023)) | |||

| <ref>{{cite news | url=https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-11-30/zimbabwe-plans-14-fold-increase-in-spending-to-aid-economy | title=Zimbabwe Plans 14-Fold Increase in Spending to Aid Economy | newspaper=Bloomberg | date=30 November 2023 }}</ref> | |||

| | expenses = 5.5 billion (2017 est.)<ref name="CIAWFZI"/> | |||

| | balance = −9.6% (of GDP) (2017 est.)<ref name="CIAWFZI"/> | |||

| | aid = ''recipient'': $178 million; note – the EU and the US provide food aid on humanitarian grounds (2000 est.) | |||

| | cianame = zimbabwe | |||

| | reserves = {{increase}} $431.8 million (31 December 2017 est.)<ref name="CIAWFZI"/> | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| The '''economy of Zimbabwe''' is a ] based economy. ] has a $44 billion dollar ] in ] terms which translates to 64.1% of the total economy.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Zimbabwe |url=https://www.worldeconomics.com/National-Statistics/Informal-Economy/Zimbabwe.aspx |access-date=2024-01-17 |website=World Economics}}</ref> Agriculture and mining largely contribute to exports. The economy is estimated to be at $73 billion at the end of 2023.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Zimbabwe {{!}} GDP {{!}} 2023 {{!}} 2024 {{!}} Economic Data |url=https://www.worldeconomics.com/Country-Size/Zimbabwe.aspx |access-date=2024-05-01 |website=World Economics}}</ref> | |||

| The '''economy of ]''' is collapsing under the weight of economic mismanagement, resulting in 85% unemployment and spiraling ]. The economy poorly transitioned after ]'s leadership, deteriorating from one of ]'s strongest economies to the world's worst. Inflation has surpassed that of all other nations at over 730,000%, with the next highest in ] at 39.5%<ref name=zy>{{cite news|https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/bm.html|title=CIA - The World Factbook -- Burma|publisher=''CIA''|date=], ]|accessdate=2008-05-17}}</ref>. The government has attributed the economy's poor performance to ], a US congressional act hinging debt relief for Zimbabwe on democratic reform, and freezing the international assets of the ruling class. It currently has the lowest GDP real growth rate in an independent country and 3rd in total (behind Palestinian territories.) | |||

| The country has reserves of metallurgical-grade ]. Other commercial mineral deposits include |

The country has reserves of metallurgical-grade ]. Other commercial mineral deposits include coal, ], ], ], ], ] and ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sadc.int/member-states/zimbabwe/|title=Southern African Development Community :: Zimbabwe|website=sadc.int|access-date=31 August 2018|archive-date=31 August 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180831104410/https://www.sadc.int/member-states/zimbabwe/|url-status=live}}</ref> | ||

| == Current economic conditions == | |||

| ==1980s== | |||

| In 2000, Zimbabwe planned a land redistribution act to seize white-owned, commercial farms attained through colonization and distribute the land to the native black majority. The new occupants, mainly consisting of indigenous citizens and several prominent members of the ruling ZANU-PF administration, were inexperienced or uninterested in farming, thereby failing to retain the labour-intensive, highly efficient management of previous landowners.<ref name="Cry">{{cite book | |||

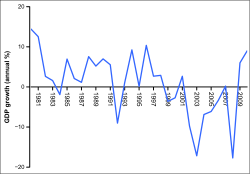

| Following the ] in December 1979, the transition to majority rule in early 1980, and the lifting of sanctions, Zimbabwe enjoyed a brisk economic recovery. Real growth for 1980-1981 exceeded 20%. However, depressed foreign demand for the country's mineral exports and the onset of a drought cut sharply into the growth rate in 1982, 1983, and 1984. In 1985, the economy rebounded strongly due to a 30% jump in agricultural production. However it slumped in 1986 to a zero growth rate and registered negative of about minus 3% in 1987 primarily because of drought and foreign exchange crisis faced by the country.{{Fact|date=December 2007}} Zimbabwe's ] grew on average by about 4.5% between 1980 and 1990.<ref name=b>{{cite book|last=Steenkamp|first=Philip John|coauthors=Rodney Dobell|year=1994|title=Public Management in a Borderless Economy|pages=664}}</ref> | |||

| |title=Cry Zimbabwe: Independence – Twenty Years On | |||

| |last=Stiff | |||

| |first=Peter | |||

| |location=Johannesburg | |||

| |publisher=Galago Publishing | |||

| |date=June 2000 | |||

| |isbn=978-1919854021 | |||

| }}</ref> Short term gains were achieved by selling the land or equipment. The contemporary lack of agricultural expertise triggered severe export losses and negatively affected market confidence. The country has experienced a massive drop in food production and idle land is now being utilised by rural communities practising subsistence farming. Production of staple foodstuffs, such as maize, has recovered accordingly – unlike typical export crops including tobacco and coffee.<ref name=scoones> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101104031151/http://thezimbabwean.co.uk/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=34979:zimbabwes-land-reform-challenging-the-myths&catid=72:thursday-issue |date=2010-11-04 }}, by Ian Scoones, The Zimbabwean,19 October 2010</ref> Zimbabwe has also sustained the 30th occurrence of recorded hyperinflation in world history.<ref name="dallasfed.org">{{cite report |last=Koech |first=Janet |date=2011 |title=Hyperinflation in Zimbabwe |url=http://www.dallasfed.org/assets/documents/institute/annual/2011/annual11b.pdf |publisher=] |access-date=2013-01-31 |archive-date=2020-11-04 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201104063506/https://www.dallasfed.org/~/media/documents/institute/annual/2011/annual11b.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Government spending is 29.7% of GDP. State enterprises are strongly subsidized. Taxes and tariffs are high, and state regulation is costly to companies. Starting or closing a business is slow and costly.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.heritage.org/index/Country/Zimbabwe |title=Zimbabwe |publisher=Heritage |access-date=2010-05-30 |archive-date=2010-05-25 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100525024023/http://www.heritage.org/index/Country/Zimbabwe |url-status=live }}</ref> Due to the regulations of the labour market, hiring and terminating workers is a lengthy process. By 2008, an unofficial estimate of unemployment had risen to 94%.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Mangena |first1=Fainos |date=March 2014 |title=Professor |url=http://www.jpanafrican.com/docs/vol6no8/6.8-Mangena.pdf |url-status=dead |journal=The Journal of Pan African Studies |volume=6 |issue=8 |page=78 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140813122636/http://www.jpanafrican.com/docs/vol6no8/6.8-Mangena.pdf |archive-date=2014-08-13 |access-date=2014-08-13}}</ref> | |||

| ==Infrastructure and resources== | |||

| Zimbabwe has adequate internal transportation and electrical power networks. Paved roads link the major urban and industrial centres, and rail lines managed by the ] tie it into an extensive central ] railroad network with all its neighbours. In non-drought years, it has adequate electrical power, mainly generated by the ] on the ] but augmented since 1983 by large thermal plants adjacent to the ] coal field. As of 2006, crumbling infrastructure and lack of spare parts for generators and coal mining means that Zimbabwe imports 40% of its power - 100 megawatts from the ], 200 megawatts from ], up to 450 from ], and 300 megawatts from ].<ref name=c>, October 9, 2006. News24.</ref> | |||

| As of 2023, Zimbabwe's official unemployment rate stood at 9.3%.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Zimbabwe Unemployment Rate 1991-2023 |url=https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/ZWE/zimbabwe/unemployment-rate |access-date=2023-02-05 |website=www.macrotrends.net}}</ref>{{efn|This can also be supported by like Work In Zimbabwe which posts several daily.}} | |||

| Independent analyst put the inflation rate at +165 000% a figure which critics claim is far less than the actual inflation rate. ] rates of measurement show point towards a figure of close to 500 000% but these cannot be cited for obvious reasons. The use of oppressive laws as manifested in the likes of the infamous National Price and Income Commission has seen the country at the bottom list of the of the World Bank Index. Recently the President of the republic signed the Empowerment bill whose effect is to transfer ownership from all foreigners into the hands of the local people something that has already had its toil on the DI. | |||

| The telephone service is problematic, and new lines are difficult to obtain. | |||

| A 2014 report by the Africa Progress Panel<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.africaprogresspanel.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/APP_APR2014_24june.pdf|title=Fish, Grain and Money: Financing Africa's Green and Blue Revolutions|date=2014|publisher=Africa Progress Panel|access-date=12 November 2014|archive-date=12 November 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141112165310/http://www.africaprogresspanel.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/APP_APR2014_24june.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> found that, of all the African countries examined when determining how many years it would take to double per capita GDP, Zimbabwe fared the worst, and that at its current rate of development it would take 190 years for the country to double its ] GDP.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://mgafrica.com/article/2014-11-04-depressing-it-could-take-zimbabwe-190-years-to-double-average-per-capita-incomes-if-current-trends-continue|title=Bad news: It could take Zimbabwe 190 years to double incomes and Kenya, Senegal 60 on present form|last=Mungai|first=Christine|date=5 November 2014|publisher=Mail & Guardian Africa|access-date=12 November 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141112173233/http://mgafrica.com/article/2014-11-04-depressing-it-could-take-zimbabwe-190-years-to-double-average-per-capita-incomes-if-current-trends-continue|archive-date=2014-11-12|url-status=dead}}</ref> Uncertainty around the ] (compulsory acquisition), the perceived lack of a ], the possibility of abandoning the US dollar as official currency, and political uncertainty following the end of the government of national unity with the MDC as well as power struggles within ZANU-PF have increased concerns that the country's economic situation could further deteriorate.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.bdlive.co.za/economy/2014/01/08/sa-at-top-of-wealth-list-for-africa-zimbabwe-near-bottom?|title=SA at top of wealth list for Africa, Zimbabwe near bottom|last=Jones|first=Gillian|date=8 January 2014|publisher=Business Day|access-date=12 November 2014|archive-date=12 November 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141112170851/http://www.bdlive.co.za/economy/2014/01/08/sa-at-top-of-wealth-list-for-africa-zimbabwe-near-bottom|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ] was once the backbone of the Zimbabwean economy. Due to large scale eviction of white farmers and the government's land reform efforts, this is no longer the case.<ref name=d>, 2002. Geography IQ</ref> | |||

| Reliable crop estimates are not available due to the Zimbabwe government's attempts to hide the realities following the evictions. The ruling party banned maize imports, stating record crops for the year of 2004.<ref name=e>, February 9, 2005. The New Farm.</ref> | |||

| In September 2016 the finance minister identified "low levels of production and the attendant trade gap, insignificant foreign direct investment and lack of access to international finance due to huge arrears" as significant causes for the poor performance of the economy.<ref name=":1">{{Cite web|url=http://www.financialgazette.co.zw/mid-term-report-reveals-deep-crisis/|title=Mid-term report reveals deep crisis|date=9 September 2016|publisher=The Financial Gazette|access-date=12 September 2016|archive-date=11 September 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160911172258/http://www.financialgazette.co.zw/mid-term-report-reveals-deep-crisis/|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| The University of Zimbabwe estimates that between 2000 and 2007 agricultural production decreased by 51%. | |||

| Zimbabwe came 140 out of 190 ease of doing business report released by the ]. They were ranked high for ability to get credit (ranked 85) and protecting minority investors (ranked 95).<ref>{{Cite web|url = https://www.mukaidigital.com/zimbabwe-is-a-top-20-ease-of-business-reformer/|title = Zimbabwe is a Top 20 Ease of Business Reformer|date = 8 July 2020|access-date = 8 July 2020|archive-date = 8 July 2020|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20200708194439/https://www.mukaidigital.com/zimbabwe-is-a-top-20-ease-of-business-reformer/|url-status = live}}</ref> | |||

| ] was the country's largest crop prior to the farm evictions. ] was the largest export crop followed by ]. Poor government management has exacerbated meager harvests caused by drought and floods, resulting in significant food shortfalls beginning in 2001. The land redistribution has been generally condemned in the developed world. It has found considerable support in Africa and a few supporters among African-American activists,{{Fact|date=June 2007}} but ] commented during a visit to South Africa in June 2006, "Land reform has long been a noble goal to achieve but it has to be done in a way that minimises trauma. The process has to attract investors rather than scare them away. What is required in Zimbabwe is democratic rule, democracy is lacking in the country and that is the major cause of this economic melt down."<ref name=f>, June 20, 2006. Zimbabwe Situation.</ref> | |||

| ==Infrastructure and resources== | |||

| ==2000–2008== | |||

| ===Transportation=== | |||

| {{seealso|Hyperinflation in Zimbabwe}} | |||

| {{See also|Transport in Zimbabwe}} | |||

| In recent years, poor management of the economy and political turmoil has led to considerable economic hardship. The ]'s chaotic ], recurrent interference with, and intimidation of, the judiciary, as well as maintenance of unrealistic price controls and exchange rates has led to a sharp drop in investor confidence. | |||

| Zimbabwe's internal transportation and electrical power networks are adequate; nevertheless, maintenance has been ignored for several years. Zimbabwe is crossed by two trans-African automobile routes: the ] and the ]. Poorly paved highways connect the major urban and industrial areas, while rail lines controlled by the ] connect Zimbabwe to a vast central African railroad network that connects it to all of its neighbors. | |||

| ===Energy=== | |||

| On ] ] a former government minister in ], ], produced a paper in London for the ]'s Foreign Affairs Committee on ''Land Reform in ]''. In his last paragraph he stated that "once the land has been redistributed, the commercial farms will be broken up, the remaining white farmers reduced by exile or imprisonment; Zimbabwe's government, already morally bankrupt, will decline towards economic collapse." | |||

| {{See also|Energy in Zimbabwe}} | |||

| The ] is responsible for providing the country with electrical energy. Zimbabwe has two larger facilities for the generation of electrical power, the ] (owned together with ]) and since 1983 by large ] adjacent to the ] coal field. However, total generation capacity does not meet the demand, leading to ]s. The Hwange station is not capable of using its full capacity due to old age and maintenance neglect. In 2006, crumbling infrastructure and lack of spare parts for generators and coal mining lead to Zimbabwe importing 40% of its power, including 100 megawatts from the ], 200 megawatts from ], up to 450 from South Africa, and 300 megawatts from ].<ref name=c> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071001000231/http://www.news24.com/News24/Africa/Zimbabwe/0,,2-11-1662_1996209,00.html |date=2007-10-01 }}, October 9, 2006. News24</ref> In May 2010 the country's generation power was an estimated 940MW against a peak demand of 2500MW.<ref> Reuters Africa; May 3, 2010; Zimbabwe, China in $400 mln power plant deal</ref> Use of local small scale ] is widespread. | |||

| ===Telephone=== | |||

| Between 2000 and December 2007, the national economy contracted by as much as 40%; inflation vaulted to over 66,000%, and there were persistent shortages of foreign exchange, local currency, fuel, medicine, and food. GDP per capita dropped by 40%, agricultural output dropped by 51% and industrial production dropped by 47%. | |||

| New telephone lines used to be difficult to obtain. With ], however, Zimbabwe has only one fixed line service provider.<ref name=":5">{{Cite web|url=https://www.africantelecomsnews.com/Operators_Regulators/List_of_African_fixed_and_mobile_telcos_Zimbabwe.html|title=Zimbabwe Mobile Operators & Fixed Network Operators list (Africa mobile and fixed network operators)|website=africantelecomsnews.com|access-date=2018-06-08|archive-date=2018-06-12|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180612142937/https://www.africantelecomsnews.com/Operators_Regulators/List_of_African_fixed_and_mobile_telcos_Zimbabwe.html|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.telone.co.zw/business/services/our-network|title=Our Network {{!}} Telone|website=telone.co.zw|language=en|access-date=2018-06-08|archive-date=2018-06-12|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180612142433/https://www.telone.co.zw/business/services/our-network|url-status=live}}</ref> Cellular phone networks are an alternative. Principal mobile phone operators are ], ], and ].<ref name=":5" /> | |||

| ===Agriculture=== | |||

| Direct foreign investment has all but evaporated. In 1998 , direct foreign investment was US $400 million. In 2007, that number had fallen to US $30 million | |||

| {{See also|Agriculture in Zimbabwe}} | |||

| ] in Zimbabwe can be divided into two parts: commercial farming of crops such as ], ], ], ]s and various fruits, and subsistence farming with staple crops, such as ] or ]. | |||

| Commercial farming was almost exclusively in the hands of the white minority until the controversial ] began in 2000. Land in Zimbabwe was forcibly seized from white farmers and redistributed to black settlers, justified by Mugabe on the grounds that it was meant to rectify inequalities left over from colonialism.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-zimbabwe-politics-farmer/ululations-tears-as-white-zimbabwean-farmer-returns-to-seized-land-idUSKBN1EF2US|title=Ululations, tears as white Zimbabwean farmer returns to seized land|last=Sithole-Matarise|first=Emelia|work=U.S.|access-date=2018-06-08|language=en-US|archive-date=2020-11-09|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201109035746/https://www.reuters.com/article/us-zimbabwe-politics-farmer/ululations-tears-as-white-zimbabwean-farmer-returns-to-seized-land-idUSKBN1EF2US|url-status=live}}</ref> The new owners did not have land titles, and as such did not have the collateral necessary to access bank loans.<ref name="reuters2016">{{cite news|last1=Mambondiyani|first1=Andrew|title=Bank loans beyond reach for Zimbabwe farmers without land titles|url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-zimbabwe-landrights-farming-idUSKCN1001R4|work=Reuters|date=20 July 2016|access-date=1 July 2017|archive-date=11 November 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201111222925/https://www.reuters.com/article/us-zimbabwe-landrights-farming-idUSKCN1001R4|url-status=live}}</ref> The small-scale farmers also did not have experience with commercial-scale agriculture. | |||

| Billions were spent in the country's involvement in the ] in the ]. Price controls have been imposed on a wide range of products including food (], bread, steak), fuel, medicines, soap, electrical appliances, yarn, window frames, building sand, agricultural machinery, fertilisers and school textbooks. | |||

| After land redistribution, much of Zimbabwe's land went fallow, and agricultural production decreased steeply.<ref name="telegraph2015">{{cite news|last1=Thornycroft|first1=Peta|title=Zimbabwe to hand back land to some white farmers|url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/africaandindianocean/zimbabwe/11737095/Zimbabwe-to-hand-back-land-to-some-white-farmers.html|work=The Telegraph|date=13 July 2015|access-date=4 April 2018|archive-date=25 November 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201125025036/https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/africaandindianocean/zimbabwe/11737095/Zimbabwe-to-hand-back-land-to-some-white-farmers.html|url-status=live}}</ref> The University of Zimbabwe estimated in 2008 that between 2000 and 2007 agricultural production decreased by 51%.<ref name="zimbabwesituation.com">{{cite web |url=http://www.zimbabwesituation.com/mar8_2008.html#Z11 |title=The Zimbabwe Situation |publisher=The Zimbabwe Situation |access-date=2010-05-30 |archive-date=2011-06-15 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110615091134/http://www.zimbabwesituation.com/mar8_2008.html#Z11 |url-status=live }}</ref> ], Zimbabwe's main export crop, decreased by 79% from 2000 to 2008.<ref name="fao2003">{{cite book|title=Issues in the Global Tobacco Economy|date=2003|publisher=Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations|chapter=Tobacco in Zimbabwe|chapter-url=http://www.fao.org/docrep/006/y4997e/y4997e0k.htm|access-date=2016-09-21|archive-date=2016-09-17|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160917152028/http://www.fao.org/docrep/006/y4997e/y4997e0k.htm|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="bloomberg2013">{{cite news|last1=Marawanyika|first1=Godfrey|title=Mugabe Makes Zimbabwe's Tobacco Farmers Land Grab Winners|url=https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-11-03/mugabe-makes-zimbabwe-s-tobacco-farmers-land-grab-winners|work=Bloomberg|date=4 November 2013|access-date=2017-03-06|archive-date=2020-08-28|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200828083604/https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-11-03/mugabe-makes-zimbabwe-s-tobacco-farmers-land-grab-winners|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Mugabe's supporters maintain that economic hardship has been brought about by Western-backed economic sanctions instituted through the ]. However, the only sanctions in place are personal sanctions against about 130 senior Zanu-PF figures; there are no sanctions against trade or investment with Zimbabwe.<ref>, '']'', 2004</ref> | |||

| Tobacco production recovered after 2008 thanks to the contract system of agriculture and growing Chinese demand. International tobacco companies, such as ] and ], supplied farmers with agricultural inputs, equipment, and loans, and supervised them in growing tobacco.<ref name="bloomberg2011">{{cite news|last1=Latham|first1=Brian|title=Mugabe's Seized Farms Boost Profits at British American Tobacco|url=https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2011-11-30/mugabe-s-seized-farms-boost-british-american-tobacco-profits-in-zimbabwe|work=Bloomberg|date=30 November 2011|access-date=2017-03-06|archive-date=2020-08-28|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200828041113/https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2011-11-30/mugabe-s-seized-farms-boost-british-american-tobacco-profits-in-zimbabwe|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="xinhua2016">{{cite news|last1=Machingura|first1=Gretinah|title=Partnering Chinese, Zimbabwe tobacco farmers embark on road to success|url=http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2016-07/10/c_135502309.htm|work=Xinhua|date=July 10, 2016|access-date=September 21, 2016|archive-date=July 11, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160711114050/http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2016-07/10/c_135502309.htm|url-status=dead}}</ref> By 2018, tobacco production had recovered to 258 million kg, the second largest crop on record.<ref name="fao2003"/><ref>{{cite news |title=Zimbabwe farmers produce record tobacco crop |url=https://www.thezimbabwemail.com/farming-enviroment/zimbabwe-farmers-produce-record-tobacco-crop/ |work=The Zimbabwe Mail |date=4 September 2019 |language=en |access-date=23 October 2019 |archive-date=24 November 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201124201942/https://www.thezimbabwemail.com/farming-enviroment/zimbabwe-farmers-produce-record-tobacco-crop/ |url-status=live }}</ref> Instead of large white-owned farms selling mostly to European and American companies, Zimbabwe's tobacco sector now consists of small black-owned farms exporting over half of the crop to China.<ref name="newsday2015">{{cite news|title=China gets lion's share of tobacco exports|url=https://www.newsday.co.zw/2015/05/04/china-gets-lions-share-of-tobacco-exports/|work=NewsDay Zimbabwe|date=4 May 2015|access-date=21 September 2016|archive-date=23 September 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160923030846/https://www.newsday.co.zw/2015/05/04/china-gets-lions-share-of-tobacco-exports/|url-status=live}}</ref> Tobacco farming accounted for 11% of Zimbabwe's GDP in 2017, and 3 million of its 16 million people depended on tobacco for their livelihood.<ref name="xinhua2018">{{cite news |title=Zimbabwe's 2018 tobacco production hits all-time high |url=http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-07/24/c_137345408.htm |work=Xinhua |date=7 July 2018 |access-date=23 October 2019 |archive-date=14 August 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200814121741/http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-07/24/c_137345408.htm |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| As of February 2004 Zimbabwe's foreign debt repayments ceased, resulting in compulsory suspension from the ] (IMF). This, and the ] World Food Programme stopping its food aid due to insufficient donations from the world community, has forced the government into borrowing from local sources. | |||

| Land reform has found considerable support in Africa and a few supporters among African-American activists,<ref>{{cite news|title=Farrakhan backs Zimbabwe land grab|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/2126648.stm|work=BBC News|date=13 July 2002|access-date=12 May 2017|archive-date=25 January 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210125160819/http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/2126648.stm|url-status=live}}</ref> but ] commented during a visit to South Africa in June 2006, "Land redistribution has long been a noble goal to achieve but it has to be done in a way that minimises trauma. The process has to attract investors rather than scare them away. What is required in Zimbabwe is democratic rule, democracy is lacking in the country and that is the major cause of this economic meltdown."<ref name=f> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130512092106/http://www.zimbabwesituation.com/jun21_2006.html |date=2013-05-12 }}, June 20, 2006. Zimbabwe Situation.</ref> | |||

| Zimbabwe began experiencing severe foreign exchange shortages, exacerbated by the difference between the official rate and the ] rate in 2000. In 2004 a system of auctioning scarce foreign currency for importers was introduced, which temporarily led to a slight reduction in the foreign currency crisis, but by mid 2005 foreign currency shortages were once again chronic. The currency was devalued by the central bank twice, first to 9,000 to the US$, and then to 17,500 to the US$ on ] ], but at that date it was reported that that was only half the rate available on the black market. | |||

| Zimbabwe produced, in 2018: | |||

| In July 2005 Zimbabwe was reported to be appealing to the South African government for US$1 billion of emergency loans, but despite regular rumours that the idea was being discussed no financial support has been obtained from South Africa. | |||

| * 3,3 million tons of ]; | |||

| The official ] exchange rate had been frozen at Z$101,196 per U.S. dollar since early 2006, but as of ] ] the parallel (black market) rate has reached Z$550,000 per U.S. dollar. By comparison, 10 years earlier, the rate of exchange was only Z$9.13 per USD. | |||

| * 730 thousand tons of ]; | |||

| * 256 thousand tons of ]; | |||

| * 191 thousand tons of ]; | |||

| * 132 thousand tons of ] (6th largest producer in the world); | |||

| * 106 thousand tons of ]; | |||

| * 96 thousand tons of ]; | |||

| * 90 thousand tons of ]; | |||

| * 80 thousand tons of ]; | |||

| * 60 thousand tons of ]; | |||

| * 55 thousand tons of ]; | |||

| * 42 thousand tons of ]; | |||

| * 38 thousand tons of ]; | |||

| In addition to smaller productions of other agricultural products.<ref>{{Cite web|title=FAOSTAT|url=https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/|access-date=2022-01-12|website=www.fao.org|archive-date=2022-01-06|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220106022112/https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

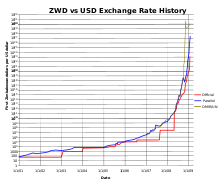

| In August 2006 the RBZ revalued the Zimbabwean Dollar by 1000 ZWD to 1 (revalued) dollar. At the same time Zimbabwe devalued the Zim Dollar by 60% against the ]. New official exchange rate revalued ZWD 250 per USD. The parallel market rate was about revalued ZWD 1,200 to 1,500 per USD (] ]).{{Fact|date=June 2007}} | |||

| ===Mining sector=== | |||

| In November 2006 it was announced that sometime around ] there would be a further devaluation and that the official exchange rate would change to revalued ZWD 750 per USD.<ref name=k></ref> This never materialized. However, the parallel market immediately reacted to this news with the parallel rate falling to ZWD 2,000 per USD (] ])<ref name=l></ref> and by year end it had fallen to ZWD 3,000 per USD.<ref name=m></ref> | |||

| {{main|Mining industry of Zimbabwe}} | |||

| As other southern African countries, Zimbabwean soil is rich in ], namely ],<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201126152236/http://www.platinum.matthey.com/production/zimbabwe |date=2020-11-26 }} in Platinum Today, Johnson and Matthey. Accessed 12. Jan 2011.</ref> ], ], and ]. Recently, ] have also been found in considerable deposits. ], ] and ] deposits also exist, though in lesser amounts. The ], discovered in 2006 are thought to be among the richest in the world. | |||

| In March 2011, the government of Zimbabwe implemented laws which required local ownership of mining companies; following this news, there were falls in the share prices of companies with mines in Zimbabwe.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.mining-journal.com/production-and-markets/implats,-aquarius-fall-on-zimbabwe-indigenisation-news|access-date=2011-03-30|publisher=Mining Journal|title=Implats, Aquarius fall on Zimbabwe indigenisation news|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110404143420/http://www.mining-journal.com/production-and-markets/implats,-aquarius-fall-on-zimbabwe-indigenisation-news|archive-date=2011-04-04}}</ref> | |||

| On ] ] the parallel market was asking ZWD 30,000 for $1 USD.<ref name=n></ref> By year end, it was down to about ZWD 2,000,000. On ] ], the ] began to issue higher denomination ZWD bearer cheques (a banknote with an expiry date), including $10 million bearer cheques - each of which was worth less than US $1.35 (70p Sterling; 0.90 Euro) on the parallel market at the time of first issue. On ] ] the ] introduced new $25 million and $50 million bearer cheques.<ref name=ac>{{cite news|http://www.thetimes.co.za/PrintEdition/Article.aspx?id=742168|title=Fear and hope mingle as Harare awaits election results|publisher=''www.thetimes.co.za''|date=], ]|accessdate=2008-04-08}}</ref> At the time of first issue they were worth US$0.70 & US$1.40 on the parallel market respectively. | |||

| On ] ], the RBZ announced that the dollar would be allowed to float in value subject to some conditions.<ref name=zz>{{cite news|http://www.fingaz.co.zw/story.aspx?stid=2704|title= Zim dollar devalued |publisher=''The Financial Gazette Zimbabwe''|date=], ]|accessdate=2008-05-02}}</ref>. | |||

| On ] ], the RBZ issued new $100 million and $250 million bearer cheques.<ref name=ad>{{cite news|http://www.thetimes.co.za/News/Article.aspx?id=761117|title=Zimbabwe’s new $250m note|publisher=''www.thetimes.co.za''|date=], ]|accessdate=2008-05-08}}</ref><ref name=ae>{{cite news|http://www.afriquenligne.fr/news/africa-news/zimbabwe-introduces-new-high-denomination-notes-200805063085.html|title=Zimbabwe introduces new high denomination notes|publisher=''http://www.afriquenligne.fr''|date=], ]|accessdate=2008-05-08}}</ref>. At the date of first issue the $250 million bearer cheque was worth approximately US$1.30 on the parallel market. On ] ], a new $500 million bearer cheque was issued by the RBZ<ref name=af>{{cite news|http://www.int.iol.co.za/index.php?set_id=1&click_id=68&art_id=nw20080515103036882C968918|title=Introducing the new Zim note...|publisher=''http://www.iol.co.za''|date=], ]|accessdate=2008-05-08}}</ref>. At time of first issue it was worth US$1.93. In a widely unreported parallel move, on ] ], the RBZ issued three "special agro-cheques" with face values $5 billion (at time of first issue - $19.30), $25 billion ($96.50) & $50 billion ($193). <ref name=ag>{{cite news|http://allafrica.com/stories/200805210105.html|title=RBZ Issues Agro Cheques|publisher=''http://allafrica.com''|date=], ]|accessdate=2008-06-02}}</ref>. It is further reported that the new agro-cheques can be used to buy any goods and services like the bearer cheques. | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| ! year !! Official exchange rate !! Parallel exchange rate | |||

| |- | |||

| | 2000 | |||

| | 38 || 56–70 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 2001 | |||

| | 55 || 70–340 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 2002 | |||

| | 55 || 380–1740 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 2003 | |||

| | 55; 824 || 1400–6000 | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! Gold production year <ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110615091134/http://www.zimbabwesituation.com/mar8_2008.html#Z11 |date=2011-06-15 }} Mar 8, 2008</ref> | |||

| | 2004 | |||

| ! kg | |||

| | 824–5730 || 5500–6000 | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | |

| 1998 | ||

| | 27,114 | |||

| | 5,730–26,003 || 6,400–100,000 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 2006 | |||

| | 85,158–101,196 <br> (250 revalued dollars)|| 100,000–550,000 <br> (550–3,000 revalued dollars)<br> | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | 2007 | | 2007 | ||

| | 7,017 | |||

| | 250 revalued dollars <br> 30,000 revalued dollars (Sept)|| 3,000–2,000,000 revalued dollars <br> (4,000,000 revalued dollars - see note) <br> | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | 2015 | |||

| | 2008 (Jan) | |||

| | 18,400<ref name="zim2015gold">{{cite news | url=https://af.reuters.com/article/investingNews/idAFKCN0S812I20151014 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151018160909/http://af.reuters.com/article/investingNews/idAFKCN0S812I20151014 | url-status=dead | archive-date=18 October 2015 | title=Zimbabwe's 2015 gold output seen at highest in 11 years | work=Reuters | date=14 October 2015 | access-date=11 September 2016}}</ref> | |||

| | 30,000 revalued dollars || 5,000,000 - 7,500,000 revalued dollars <ref name=q>{{cite news|url=http://www.news24.com/News24/Africa/Zimbabwe/0,,2-11-1662_2248835,00.html|title=Britain 'behind' BA's pullout|publisher=''www.news24.com''|date=], ]|accessdate=2008-01-09}}</ref><ref name=r>{{cite news|url=http://www.fin24.co.za/articles/default/display_article.aspx?Nav=ns&ArticleID=1518-25_2249487|title=Zim poverty line hits $100m|publisher=''www.fin24.co.za''|date=], ]|accessdate=2008-01-10}}</ref> | |||

| | |

|} | ||

| | 2008 (Feb) | |||

| | 30,000 revalued dollars|| 20,000,000 revalued dollars <ref name=s>{{cite news|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/shared/spl/hi/pop_ups/08/africa_enl_1204117689/html/1.stm|title=A Zimbabwean beggar poses with wads of Z$200,000 notes in the capital, Harare, where on the black market Z$200,000 is worth one US cent.|publisher=''news.bbc.co.uk''|date=], ]|accessdate=2008-02-27}}</ref><ref name=t>{{cite news|url=http://www.earthtimes.org/articles/show/188475,zimbabwe-dollar-in-dramatic-fall.html|title=Zimbabwe dollar in dramatic fall |publisher=''www.earthtimes.org''|date=], ]|accessdate=2008-02-27}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | 2008 (Mar) | |||

| | 30,000 revalued dollars|| 35 - 70,000,000 revalued dollars <ref name=u>{{cite news|url= | |||

| http://africa.reuters.com/business/news/usnBAN140086.html|title=Zimbabwe opposition wants to float currency|publisher=''Reuters''|date=], ]|accessdate=2008-03-11}}</ref><ref name=v>{{cite news|url= | |||

| http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601116&sid=aO3baMKkEuPo&refer=africa|title=Cash Shortage Resurfaces as Zimbabwe Currency Plunges Further|publisher=''Bloomberg''|date=], ]|accessdate=2008-03-11}}</ref><ref name=w>{{cite news|url= | |||

| http://www.fin24.com/articles/default/display_article.aspx?Nav=ns&ArticleID=1518-25_2287003|title=Zim dollar in freefall|publisher=''fin24.co.za''|date=], ]|accessdate=2008-03-12}}</ref><ref name=y>{{cite news|url= | |||

| http://www.zimbabwesituation.com/mar11a_2008.html#Z8|title=Zimbabwe Business Watch : Week 11|publisher=''Zimbabwe Situation''|date=], ]|accessdate=2008-03-17}}</ref><ref name=z>{{cite news|url= | |||

| http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/in_pictures/7308696.stm|title=Africa in Pictures March 15-21 (Picture 9)|publisher=''BBC News''|date=], ]|accessdate=2008-03-21}}</ref><ref name=aa>{{cite news|url= | |||

| http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601116&sid=abbayTEdJKQQ&refer=africa|title=Zimbabwean Dollar Slumps as Residents Rush for Foreign Currency|publisher=''Bloomberg''|date=], ]|accessdate=2008-03-21}}</ref><ref name=ab>{{cite news|url= | |||

| http://www.zimbabweanequities.com/|title=Old Mutual Implied Rate|publisher=''ZimbabweanEquities.com''|date=], ]|accessdate=2008-04-08}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | 2008 (Apr) | |||

| | 30,000 revalued dollars || 35 - 241,750,000 revalued dollars <ref name=ab>{{cite news|url= | |||

| http://www.zimbabweanequities.com/|title=Old Mutual Implied Rate|publisher=''ZimbabweanEquities.com''|date=], ]|accessdate=2008-04-30}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | 2008 (May) | |||

| | 30,000 revalued dollars<ref name=zz>{{cite news|http://www.fingaz.co.zw/story.aspx?stid=2704|title= Zim dollar devalued |publisher=''The Financial Gazette Zimbabwe''|date=], ]|accessdate=2008-05-02}}</ref> || 193 - 869,850,000 revalued dollars <ref name=ab>{{cite news|url= | |||

| http://www.zimbabweanequities.com/|title=Old Mutual Implied Rate|publisher=''ZimbabweanEquities.com''|date=], ]|accessdate=2008-05-02}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | 2008 (June) | |||

| | 30,000 revalued dollars<ref name=zz>{{cite news|http://www.fingaz.co.zw/story.aspx?stid=2704|title= Zim dollar devalued |publisher=''The Financial Gazette Zimbabwe''|date=], ]|accessdate=2008-05-02}}</ref> || 969,130,000 - 34,911,000,000 revalued dollars <ref name=ab>{{cite news|url= | |||

| http://www.zimbabweanequities.com/|title=Old Mutual Implied Rate|publisher=''ZimbabweanEquities.com''|date=], ]|accessdate=2008-05-02}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | colspan='3'|<small>Note(1): Official rates quoted are Government set exchange rates. Parallel (]) rates differ significantly. | |||

| Note(2): Due to the Dec 2007 cash shortage, a rate of 4,000,000 revalued dollars was available on electronic funds transfers. | |||

| Various NGOs reported that the diamond sector in Zimbabwe is rife with ]; a November 2012 report by NGO Reap What You Sow revealed a huge lack of transparency of diamond revenues and asserted that Zimbabwe's elite are benefiting from the country's diamonds.<ref>{{Citation | |||

| Note(3): Some news agencies are reporting exchange rates in terms of the weight of Zimbabwe dollar bearer cheques that can be purchased. <ref name=x>{{cite news|url=http://english.aljazeera.net/NR/exeres/E125B1C2-E916-47F2-A304-A67034509E46.htm|title=Zimbabwe inflation at record level|publisher=''Al Jazeera''|date=], ]|accessdate=2008-03-12}}</ref> | |||

| | url = http://allafrica.com/stories/201211151002.html | |||

| | title = Zimbabwe: Reap What You Sow – Greed and Corruption in Marange Diamond Fields | |||

| | year = 2012 | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | location = ] | |||

| | access-date = 16 November 2012 | |||

| | archive-date = 18 November 2012 | |||

| | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20121118052727/http://allafrica.com/stories/201211151002.html | |||

| | url-status = live | |||

| }}</ref> This followed former South African President ]’s warning days earlier that Zimbabwe needed to stop its "predatory elite" from colluding with mining companies for their own benefit.<ref name=ALL>{{Citation | |||

| | url = http://allafrica.com/stories/201211130777.html | |||

| | title = Zimbabwe: Mbeki Lectures Zim – Report | |||

| | year = 2012 | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | location = ] | |||

| | access-date = 20 November 2012 | |||

| | archive-date = 19 November 2012 | |||

| | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20121119042214/http://allafrica.com/stories/201211130777.html | |||

| | url-status = live | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| Also in that month, the ] reported that at least $2 billion worth of diamonds had been stolen from Zimbabwe's eastern diamond fields and had enriched Mugabe's ruling circle and various connected gem dealers and criminals.<ref name=ALL /> | |||

| In January 2013, Zimbabwe's mineral exports totalled $1.8 billion.<ref>{{Citation | |||

| Note(4): ZimbabweanEquities.com publishes daily updates on the Zim$:US$ rate based on the trading values of stocks on the Harare and other stock markets, calculating an implied value for the Zim$<ref name=ab>{{cite news|url= | |||

| | url = http://allafrica.com/stories/201301280787.html | |||

| http://www.zimbabweanequities.com/|title=Old Mutual Implied Rate|publisher=''ZimbabweanEquities.com''|date=], ]|accessdate=2008-04-08}}</ref> | |||

| | title = Zimbabwe: Mineral Exports Net U.S.$1,8 Billion | |||

| |} | |||

| | year = 2013 | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | location = ] | |||

| | access-date = 2013-02-04 | |||

| | archive-date = 2013-01-31 | |||

| | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20130131173246/http://allafrica.com/stories/201301280787.html | |||

| | url-status = live | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| As of October 2014, ] was Zimbabwe's largest gold miner.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2014-10-17/biggest-zimbabwe-gold-miner-to-decide-on-london-listing-by-march|title=Terms of Service Violation|website=bloomberg.com|date=17 October 2014 |access-date=31 August 2018|archive-date=2020-08-28|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200828234550/https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2014-10-17/biggest-zimbabwe-gold-miner-to-decide-on-london-listing-by-march|url-status=live}}</ref> The group is controlled by its Chairman ]. | |||

| Poverty and unemployment are both endemic in Zimbabwe, driven by the shrinking economy and hyper-inflation. Both unemployment and poverty rates run near 80%.<ref name=g>{{cite news|url=http://www.economist.com/world/africa/displaystory.cfm?story_id=9475943|title=How to stay alive when it all runs out|publisher=''The Economist''|date=], ]|accessdate=2007-07-18}}</ref> | |||

| In 2019, the country was the world's 3rd largest producer of ]<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2021/mcs2021-platinum.pdf |title=USGS Platinum Production Statistics |access-date=2021-04-30 |archive-date=2021-05-09 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210509143917/https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2021/mcs2021-platinum.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> and the 6th largest world producer of ].<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2021/mcs2021-lithium.pdf |title=USGS Lithium Production Statistics |access-date=2021-04-30 |archive-date=2021-05-09 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210509143135/https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2021/mcs2021-lithium.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> In the production of ], in 2017 the country produced 23.9 tons.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/zimbabwe/gold-production |title=Zimbabwe Gold Production |access-date=2021-04-30 |archive-date=2020-11-03 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201103020354/https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/zimbabwe/gold-production |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| As of January 2006, the official poverty line was ZWD 17,200 per month (17c US). However, as of March 2008 this had risen to ZWD 875 million per month (US $35.00) . Most general labourers are paid under ZWD 250 million (US $10) per month . | |||

| ===Education=== | |||

| Salaries for most government employees range from 200 million to 500 million Zimbabwe dollars (per month) and a union representing teachers making up the bulk of state workers is pushing for a wage hike to at least Z$1.7 billion to keep up with inflation. | |||

| The state of ] affects the development of the economy while the state of the economy can affect access and quality of teachers and education. Zimbabwe has one of Africa's highest ] rates at over 90%.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Zimbabwe – Administration and social conditions|url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Zimbabwe|access-date=2021-03-03|website=Encyclopedia Britannica|language=en|archive-date=2021-03-07|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210307125733/https://www.britannica.com/place/Zimbabwe|url-status=live}}</ref> The crisis since 2000 has, however, diminished these achievements because of a lack of resources and the exodus of teachers and specialists (e.g. doctors, scientists, engineers) to other countries. Also, the start of the new curriculum in primary and secondary sections has affected the state of the once strong education sector.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Kanyongo|first=Gibbs Y.|date=2005|title=Zimbabwe's Public Education System Reforms: Successes and Challenges|url=https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ854955.pdf|journal=International Education Journal|volume=6|pages=65–74|access-date=2021-03-03|archive-date=2021-06-13|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210613031322/https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ854955.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ==Science and technology== | |||

| The lowest 10% of Zimbabwe's population consume only 1.97% of the economy, while the highest 10% consume 40.42%. (1995).<ref name=h>CIA World Fact Book 2003 http://www.umsl.edu/services/govdocs/wofact2003/geos/zi.html</ref> The current account balance of the country is negative, standing at around US -$517 million.<ref name=i>http://www.zimbabwesituation.com/jul28b_2006.html#Z2 Zimbabwe Budget puts government at ZWD 253 trillion in the red. (2006-07-27)</ref> | |||

| Zimbabwe's ''Second Science and Technology Policy'' (2012) cites sectorial policies with a focus on biotechnology, information and communication technologies (ICTs), space sciences, nanotechnology, indigenous knowledge systems, technologies yet to emerge and scientific solutions to emergent environmental challenges. The policy makes provisions for establishing a National Nanotechnology Programme.<ref name=":2">{{Cite book|url=http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0022/002288/228806e.pdf|title=Mapping Research and Innovation in the Republic of Zimbabwe|last1=Lemarchand|first1=Guillermo A.|last2=Schneegans|first2=Susan |publisher=UNESCO|year=2014|isbn=978-92-3-100034-8|location=Paris|access-date=2017-03-20|archive-date=2017-01-28|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170128085611/http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0022/002288/228806e.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name=":3">{{Cite book|url=http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002354/235406e.pdf|title=UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030|publisher=UNESCO|year=2015|isbn=978-92-3-100129-1|location=Paris|pages=562–563|access-date=2017-03-20|archive-date=2017-06-30|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170630025557/http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002354/235406e.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Zimbabwe has a ''National Biotechnology Policy'' which dates from 2005. Despite poor infrastructure and a lack of both human and financial resources, biotechnology research is better established in Zimbabwe than in most sub-Saharan countries, even if it tends to use primarily traditional techniques.<ref name=":2" /><ref name=":3" /> | |||

| ===Government response=== | |||

| The 2007 Empowerment Bill to increase local ownership of economy is being drafted for presentation to parliament in July 2007.<ref name=j> Zimbabwe Situation</ref> It is signed into law by President Mugabe on 7th March 2008. The law requires all White or foreign owned business to hand over 51 percent of their business to indigenous Zimbabweans. Many economists predict this will plunge the country into deeper economic woes. | |||

| The ''Second Science and Technology Policy'' asserts the government commitment to allocating at least 1% of GDP to research and development, focusing at least 60% of university education on developing skills in ] and ensuring that school pupils devote at least 30% of their time to studying science subjects.<ref name=":2" /><ref name=":3" /> | |||

| In response to skyrocketing inflation the government has introduced ], but enforcement has been largely unsuccessful.<ref></ref> Police have been sent in to enforce requirements that shopkeepers sell goods at a loss. This has resulted in hundreds of shop owners being arrested under accusations of not having lowered prices enough. Because of this, basic goods no longer appear on supermarket shelves and the supply of ] is limited. This has diminished public transport. However, goods can usually be had for a high rate on the ].<ref name=g/> | |||

| == |

==History== | ||

| {{See also|Economic history of Zimbabwe|1997 Zimbabwean Black Friday}} | |||

| {|class="toccolours" id="ZimEconomy" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0" width="400px" style="margin: 0 0 1em 1em; border: 1px solid #060; font-size:14px" | |||

| ] annual percentage growth rate from 1980 to 2010.<ref name="WDI">{{cite web | url=http://databank.worldbank.org/ddp/home.do?Step=3&id=4 | title=World Development Indicators | publisher=World Bank | access-date=January 6, 2012 | archive-date=April 11, 2013 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130411213903/http://databank.worldbank.org/ddp/home.do?Step=3 | url-status=live }}</ref>]]In 1997, Zimbabwe's economic decline began to visibly take place. It began with the crash of the stock market on November 14, 1997. Civil society groups began to agitate for their rights as these had been eroded under ESAP. In 1997 alone, 232 strikes were recorded, the largest number in any year since independence (Kanyenze 2004). During the first half of 1997, the war veterans organized themselves and demonstrations that were initially ignored by the government. As the intensity of the strikes grew, the government was forced to pay the war veterans a once-off gratuity of ZWD $50,000 by December 31, 1997, and a monthly pension of US$2,000 beginning January 1998 (Kanyenze 2004). To raise money for this unbudgeted expense, the government tried to introduce a ‘war veterans’ levy,’ but they faced much opposition from the labor force and had to effectively borrow money to meet these obligations. Following the massive depreciation of the ] in 1997, the cost of agricultural inputs soared, undermining the viability of the producers who in turn demanded that the producer price of maize (corn) be raised. Millers then hiked prices by 24 percent in January 1998 by 24 percent and the consequent increase in the price of maize meal triggered nation-wide riots during the last month. The government intervened by introducing price controls on all basic commodities (Kanyenze 2004). Many interventionist moves were undertaken to try to reverse some of the negative effects of the ] and to try to strengthen the private sector that was suffering from decreasing output and increasing competition from cheap imported products. Some of the most detrimental policies that followed include:<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Munangagwa|first=Chidochashe L.|date=27 May 2021|title=The Economic Decline of Zimbabwe|url=https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1021&context=ger|journal=The Gettysburg Economic Review|volume=3|pages=114|access-date=27 May 2021|archive-date=27 May 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210527110915/https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1021&context=ger|url-status=live}}</ref>{{multiple image | |||

| |- | |||

| | header = '''GDP per capita''' | |||

| | style="border-bottom: 1px solid #060;"|<small>Production | |||

| | direction = vertical | |||

| | style="border-bottom: 1px solid #060;"|<small> 27,114 kg. (1998) | |||

| | width = 250 | |||

| | style="border-bottom: 1px solid #060;"|<small> 7,017 kg. (2007) | |||

| | align = right | |||

| |} | |||

| | image1 = Zimbabwe GDP per cap 2015.png | |||

| | caption1 = ] in current US dollars from 1980 to 2014. The graph compares Zimbabwe (blue {{color box|#0000FF}}) and all of ]'s (yellow {{color box|#DAA520}}) GDP per capita. Different periods in Zimbabwe's recent economic history such as the land reform period (pink {{color box|#FFC0CB}}), hyperinflation (grey {{color box|#C0C0C0}}), and the dollarization/government of national unity period (light blue {{color box|#ADD8E6}}) are also highlighted. It shows that economic activity declined in Zimbabwe over the period that the land reforms took place whilst the rest of Africa rapidly overtook the country in the same period.<ref name="WDI"/> | |||

| | image2 = GDP per capita (current), % of world average, 1960-2012; Zimbabwe, South Africa, Botswana, Zambia, Mozambique.png | |||

| | caption2 = GDP per capita (current) of Zimbabwe (blue {{color box|#0000FF}}) from 1960 to 2012, compared to neighbouring countries (world average = 100) | |||

| }} | |||

| == |

===1980–2000=== | ||

| At the time of independence, annual inflation was 5.4 percent and month-to-month inflation was 0.5 percent. Currency of Z$2, Z$5, Z$10 and Z$20 denominations were released. Roughly 95 percent of transactions used the Zimbabwean dollar.<ref name="dallasfed.org"/> | |||

| {|class="toccolours" id="ZimEconomy" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0" width="400px" style="margin: 0 0 1em 1em; border: 1px solid #060; font-size:14px" | |||

| Following the ] in December 1979, the transition to majority rule in early 1980, and the lifting of sanctions, Zimbabwe enjoyed a brisk economic recovery. Real growth for 1980–1981 exceeded 20%. However, depressed foreign demand for the country's mineral exports and the onset of a drought cut sharply into the growth rate in 1982, 1983, and 1984. In 1985, the economy rebounded strongly due to a 30% jump in agricultural production. However, it slumped in 1986 to a zero growth rate and registered a negative of about 3% in 1987, primarily because of drought and the foreign exchange crisis faced by the country.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Munangagwa|first=Chidochashe|date=30 May 2021|title=The Economic Decline of Zimbabwe|url=https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1021&context=ger|journal=African Studies Commons, International Economics Commons, Public Economics|volume=3|pages=5|access-date=27 May 2021|archive-date=27 May 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210527110915/https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1021&context=ger|url-status=live}}</ref>{{Citation needed|date=December 2007}} Zimbabwe's ] grew on average by about 4.5% between 1980 and 1990.<ref name=b>{{cite book|last=Steenkamp|first=Philip John|author2=Rodney Dobell|year=1994|title=Public Management in a Borderless Economy|page=664}}</ref> | |||

| | style="text-align:center;color:#ffffff; background-color:#339900;" colspan='2'|<font color="white">'''Electricity''' | |||

| |- | |||

| In 1992, a World Bank study indicated that more than 500 health centres had been built since 1980. The percentage of children vaccinated increased from 25% in 1980 to 67% in 1988, and life expectancy increased from 55 to 59 years. Enrolment increased by 232 percent one year after primary education was made free, and secondary school enrolment increased by 33 percent in two years. These social policies lead to an increase in the debt ratio. Several laws were passed in the 1980s in an attempt to reduce wage gaps. However, the gaps remained considerable. In 1988, the law gave women, at least in theory, the same rights as men. Previously, they could only take a few personal initiatives without the consent of their father or husband.<ref>Zimbabwe's development experiment 1980–1989, Peter Makaye and Constantine Munhande, 2013</ref> | |||

| | style="border-bottom: 1px solid #060;"|<small>Production | |||

| | style="border-bottom: 1px solid #060;"|<small> 8.877 billion kWh (2003) | |||

| The government started crumbling when a bonus to independence war veterans was announced in 1997 (which was equal to 3 percent of GDP) followed by unexpected spending due to Zimbabwe's involvement in the ] in 1998. In 1999, the country also witnessed a drought which further weakened the economy, ultimately leading to the country's bankruptcy in the next decade.<ref name="dallasfed.org" /> In the same year, 1999, Zimbabwe experienced its first ] on its ], ], and ] debts in addition to debts taken out with Western lenders.<ref name="DefaultIMFwbIMF">{{cite web | url=http://www.zimbabwesituation.com/news/zimsit_w_govt-seeks-new-world-bank-imf-loans/ | title=Govt seeks new World Bank, IMF loans | publisher=New Zimbabwe | date=15 October 2015 | access-date=18 October 2015 | archive-date=5 August 2020 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200805031543/https://www.zimbabwesituation.com/news/zimsit_w_govt-seeks-new-world-bank-imf-loans/ | url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="border-bottom: 1px solid #060;"|<small>Consumption | |||

| ===2000–2009=== | |||

| | style="border-bottom: 1px solid #060;"|<small>11.22 billion kWh (2003) | |||

| {{See also|Land reform in Zimbabwe}} | |||

| |- | |||

| In recent years, there has been considerable economic hardship in Zimbabwe. Many western countries argue that the ]'s ], recurrent interference with, and intimidation of the judiciary, as well as maintenance of unrealistic price controls and exchange rates has led to a sharp drop in investor confidence. | |||

| | style="border-bottom: 1px solid #060;"|<small>Exports | |||

| | style="border-bottom: 1px solid #060;"|<small>0 kWh (2003) | |||

| Between 2000 and December 2007, the national economy contracted by as much as 40%; inflation vaulted to over 66,000%, and there were persistent shortages of ], fuel, medicine, and food. GDP per capita dropped by 40%, agricultural output dropped by 51% and industrial production dropped by 47%.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Rukuni|first=Mandivamba|title=Zimbabwe's Agriculture Revolution Revisited|publisher=University of Zimbabwe|year=2006|isbn=0-86924-141-9|location=Zimbabwe Publication|pages=14, 15, 16}}</ref> {{Citation needed|date=March 2021}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="border-bottom: 1px solid #060;"|<small>Imports | |||

| The Mugabe Government attribute Zimbabwe's economic difficulties to sanctions imposed by the Western powers. It has been argued{{By whom|date=April 2010}} that the sanctions imposed by Britain, the US, and the EU have been designed to cripple the economy and the conditions of the Zimbabwean people in an attempt to overthrow President Mugabe's government. These countries on their side argue that the sanctions are targeted against Mugabe and his inner circle and some of the companies they own. Critics{{Who|date=April 2010}} point to the so-called "]", signed by Bush, as an effort to undermine Zimbabwe's economy. Soon after the bill was signed, IMF cut off its resources to Zimbabwe. Financial institutions began withdrawing support for Zimbabwe. Terms of the sanctions made it such that all economic assistance would be structured in support of "democratisation, respect for human rights and the rule of law." The EU terminated its support for all projects in Zimbabwe. Because of the sanctions and US and EU foreign policy, none of Zimbabwe's debts have been cancelled as in other countries.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://allafrica.com/stories/200903060382.html |title=Zimbabwe: Sanctions – Neither Smart Nor Targeted |publisher=Allafrica.com |date=2009-03-06 |access-date=2010-05-30 |archive-date=2012-10-17 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121017053632/http://allafrica.com/stories/200903060382.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| | style="border-bottom: 1px solid #060;"|<small> 3.3 billion kWh (2003)<br> | |||

| 9.50% from D.R.Congo<br> | |||

| Other observers also point out how the asset freezes by the EU on people or companies associated with Zimbabwe's Government have had significant economic and social costs to Zimbabwe.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.newzimbabwe.com/pages/sanctions36.13187.html |title=Zimbabwe sanctions: are they political or economic? |publisher=Newzimbabwe.com |access-date=2010-05-30 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100407194926/http://www.newzimbabwe.com/pages/sanctions36.13187.html |archive-date=2010-04-07 }}</ref> | |||

| 19.0% from Mozambique<br> | |||

| 28.5% from Zambia<br> | |||

| As of February 2004, Zimbabwe's foreign debt repayments ceased, resulting in compulsory suspension from the ] (IMF). This, and the ] ] stopping its food aid due to insufficient donations from the world community, has forced the government into borrowing from local sources. | |||

| 43.0% from South Africa | |||

| |- | |||

| ==== Hyperinflation (2004–2009) ==== | |||

| | colspan='2' style="text-align:center;color:#ffffff; background-color:#003399;"|<font color="white">'''Oil''' | |||

| {{See also|Hyperinflation in Zimbabwe}} | |||

| |- | |||

| ].]] | |||

| | style="border-bottom: 1px solid #060;"|<small>Production | |||

| Zimbabwe began experiencing severe foreign exchange shortages, exacerbated by the difference between the official rate and the ] rate in 2000. In 2004 a system of auctioning scarce foreign currency for importers was introduced, which temporarily led to a slight reduction in the foreign currency crisis, but by mid-2005 foreign currency shortages were once again severe. The currency was devalued by the central bank twice, first to 9,000 to the US$, and then to 17,500 to the US$ on 20 July 2005, but at that date it was reported that that was only half the rate available on the black market. | |||

| | style="border-bottom: 1px solid #060;"|<small>0 bbl/day (2003 est.) | |||

| |-♦ | |||

| In July 2005 Zimbabwe was reported to be appealing to the South African government for US$1 billion of emergency loans, but despite regular rumours that the idea was being discussed no substantial financial support has been publicly reported. | |||

| | style="border-bottom: 1px solid #060;"|<small>Consumption | |||

| | style="border-bottom: 1px solid #060;"|<small>22,500 bbl/day (2003 est.) | |||

| In December 2005 Zimbabwe made a mystery loan repayment of US$120 million to the ] due to expulsion threat from IMF.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2005-09-01 |title=Zimbabwe: Mugabe pays IMF - Zimbabwe {{!}} ReliefWeb |url=https://reliefweb.int/report/zimbabwe/zimbabwe-mugabe-pays-imf |access-date=2023-12-29 |website=reliefweb.int |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Zimbabwe makes $120M payment to IMF {{!}} Devex |url=https://www.devex.com/news/zimbabwe-makes-120m-payment-to-imf-46540/amp |access-date=2023-12-29 |website=www.devex.com}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |last= |date=2005-09-01 |title=Zimbabwe Makes $120 Million Payment to I.M.F. |language=en-US |work=The New York Times |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2005/09/01/international/africa/zimbabwe-makes-120-million-payment-to-imf.html |access-date=2023-12-29 |issn=0362-4331}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="border-bottom: 1px solid #060;"|<small>Exports | |||

| The official ] exchange rate had been frozen at Z$101,196 per U.S. dollar since early 2006, but as of 27 July 2006 the parallel (black market) rate has reached Z$550,000 per U.S. dollar. By comparison, 10 years earlier, the rate of exchange was only Z$9.13 per USD. | |||

| | style="border-bottom: 1px solid #060;"|<small>0 bbl/day (2003) | |||

| |- | |||

| In August 2006 the RBZ revalued the Zimbabwean Dollar by 1000 ZWD to 1 (revalued) dollar. At the same time Zimbabwe devalued the Zim Dollar by 60% against the ]. New official exchange rate revalued ZWD 250 per USD. The parallel market rate was about revalued ZWD 1,200 to 1,500 per USD (28 September 2006).<ref name="zz">{{Cite web |title=Timeline: Zimbabwe's economic woes |url=https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2007/3/11/timeline-zimbabwes-economic-woes |access-date=2023-10-26 |website=www.aljazeera.com |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| | style="border-bottom: 1px solid #060;"|<small>Imports | |||

| | style="border-bottom: 1px solid #060;"|<small>23,000 bbl/day (2003) | |||