| Revision as of 10:20, 2 September 2008 view sourceFranamax (talk | contribs)18,113 edits →Nomenclature: add wikilinked term← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 07:25, 30 December 2024 view source OAbot (talk | contribs)Bots440,440 editsm Open access bot: doi updated in citation with #oabot. | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Group of diseases involving cell growth}} | |||

| {{sprotected2}} | |||

| {{About|the group of diseases}} | |||

| {{otheruses}} | |||

| {{Pp-semi-indef}} | |||

| {{Infobox_Disease | |||

| {{pp-move}} | |||

| | Name = Cancer | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=February 2024}} | |||

| | Image = Normal cancer cell division from NIH-2.svg | |||

| {{cs1 config|name-list-style=vanc|display-authors=6}} | |||

| | Caption = When normal cells are damaged beyond repair, they are eliminated by ] (A). Cancer cells avoid apoptosis and continue to multiply in an unregulated manner (B). | |||

| {{Infobox medical condition (new) | |||

| | DiseasesDB = 28843 | |||

| | name = Cancer | |||

| | ICD10 = | |||

| | image = Tumor Mesothelioma2 legend.jpg | |||

| | ICD9 = | |||

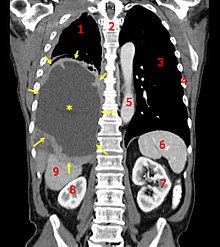

| | caption = A coronal ] showing a malignant ]<br />Legend: → ] ←, ✱ central ], 1 & 3 ]s, 2 ], 4 ]s, 5 ], 6 ], 7 & 8 ]s, 9 ] | |||

| | ICDO = | |||

| | field = ] | |||

| | OMIM = | |||

| | synonyms = ] ], malignant ] | |||

| | MedlinePlus = 001289 | |||

| | pronounce = {{IPAc-en|audio=en-us-cancer.ogg|ˈ|k|æ|n|s|ər}} | |||

| | eMedicineSubj = | |||

| | symptoms = Lump, abnormal bleeding, prolonged cough, unexplained ], change in ]s<ref name=NHS2012/> | |||

| | eMedicineTopic = | |||

| | complications = | |||

| | MeshID = D009369 | |||

| | onset = | |||

| | duration = | |||

| | causes = | |||

| | risks = Exposure to ]s, tobacco, ], poor ], ], excessive ], certain infections<ref name=WHO2018/><ref name=Enviro2008/> | |||

| | diagnosis = | |||

| | differential = | |||

| | prevention = | |||

| | treatment = ], surgery, ], ]<ref name=WHO2018/><ref name=TCT2018/> | |||

| | medication = | |||

| | prognosis = Average ] 66% (USA)<ref name=Seer2014/> | |||

| | frequency = 24 million annually (2019)<ref name="kocarnik">{{cite journal | vauthors = Kocarnik JM, Compton K, Dean FE, Fu W, Gaw BL, Harvey JD, etal | title = Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived With Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years for 29 Cancer Groups From 2010 to 2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 | journal = JAMA Oncology | volume = 8 | issue = 3 | pages = 420–444 | date = March 2022 | pmid = 34967848 | pmc = 8719276 | doi = 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.6987 |issn = 2374-2437}}</ref> | |||

| | deaths = 10 million annually (2019)<ref name=kocarnik/> | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Cancer''' is a group of ]s involving ] with the potential to ] or ] to other parts of the body.<ref name=WHO2018/><ref name=WhatIsCancerNCI/> These contrast with ]s, which do not spread.<ref name=WhatIsCancerNCI/> Possible ] include a lump, abnormal bleeding, prolonged cough, unexplained weight loss, and a change in ].<ref name=NHS2012>{{cite web |title=Cancer – Signs and symptoms |url=http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Cancer/Pages/Symptoms.aspx |website=NHS Choices |access-date=10 June 2014 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140608104550/http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/cancer/Pages/symptoms.aspx |archive-date=8 June 2014}}</ref> While these symptoms may indicate cancer, they can also have other causes.<ref name=NHS2012/> Over ] of cancers affect humans.<ref name=WhatIsCancerNCI/> | |||

| ] specimen containing a large cancer of the breast (in this case, an invasive ]).]] | |||

| ] is the cause of about 22% of cancer deaths.<ref name=WHO2018>{{cite web |title=Cancer |url=https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer |website=World Health Organization |access-date=19 December 2018 |date=12 September 2018}}</ref> Another 10% are due to ], poor ], ] or ].<ref name=WHO2018/><ref>{{cite web |title=Obesity and Cancer Risk |url=http://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/obesity/obesity-fact-sheet#q3 |publisher=National Cancer Institute |access-date=4 July 2015 |date=3 January 2012 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150704154440/http://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/obesity/obesity-fact-sheet#q3 |archive-date=4 July 2015}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Jayasekara H, MacInnis RJ, Room R, English DR | title = Long-Term Alcohol Consumption and Breast, Upper Aero-Digestive Tract and Colorectal Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis | journal = Alcohol and Alcoholism | volume = 51 | issue = 3 | pages = 315–30 | date = May 2016 | pmid = 26400678 | doi = 10.1093/alcalc/agv110 | doi-access = free }}</ref> Other factors include certain infections, exposure to ], and environmental pollutants.<ref name="Enviro2008">{{cite journal |vauthors=Anand P, Kunnumakkara AB, Sundaram C, Harikumar KB, Tharakan ST, Lai OS, Sung B, Aggarwal BB |date=September 2008 |title=Cancer is a preventable disease that requires major lifestyle changes |journal=Pharmaceutical Research |volume=25 |issue=9 |pages=2097–116 |doi=10.1007/s11095-008-9661-9 |pmc=2515569 |pmid=18626751}}{{Erratum|doi=10.1007/s11095-008-9690-4|pmid=18626751|checked=yes}}</ref> ] with specific viruses, bacteria and parasites is an environmental factor causing approximately 16–18% of cancers worldwide.<ref>{{Cite journal|url=https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(19)30488-7/fulltext|title=Global burden of cancer attributable to infections in 2018: a worldwide incidence analysis|first1=Catherine|last1=de Martel|first2=Damien|last2=Georges|first3=Freddie|last3=Bray|first4=Jacques|last4=Ferlay|first5=Gary M|last5=Clifford|date=15 February 2020|journal=The Lancet Global Health|volume=8|issue=2|pages=e180–e190|doi=10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30488-7|pmid=31862245 |doi-access=free}}</ref> These infectious agents include '']'', ], ], ], ], ], ] and ]. ] (HIV) does not directly cause cancer but it causes immune deficiency that can magnify the risk due to other infections, sometimes up to several thousand fold (in the case of ]). Importantly, vaccination against ] and ] have been shown to nearly eliminate risk of cancers caused by these viruses in persons successfully vaccinated prior to infection. | |||

| ] specimen containing an invasive ] (the crater-like, reddish, irregularly-shaped tumor).]] | |||

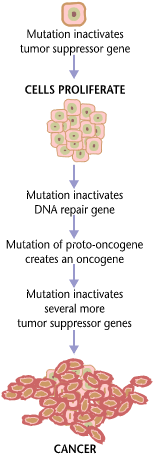

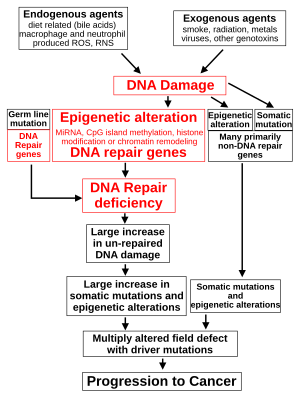

| These environmental factors act, at least partly, by changing the ]s of a cell.<ref name=WCR2014Scr/> Typically, many genetic changes are required before cancer develops.<ref name=WCR2014Scr/> Approximately 5–10% of cancers are due to inherited genetic defects.<ref name=ACS-heredity>{{cite web |publisher=] |title=Heredity and Cancer |access-date=22 July 2013 |url=http://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancercauses/geneticsandcancer/heredity-and-cancer |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130802043732/http://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancercauses/geneticsandcancer/heredity-and-cancer |archive-date=2 August 2013}}</ref> Cancer can be detected by certain signs and symptoms or screening tests.<ref name=WHO2018/> It is then typically further investigated by ] and confirmed by ].<ref>{{cite web |title=How is cancer diagnosed? |url=http://www.cancer.org/treatment/understandingyourdiagnosis/examsandtestdescriptions/testingbiopsyandcytologyspecimensforcancer/testing-biopsy-and-cytology-specimens-for-cancer-how-is-cancer-diagnosed |website=American Cancer Society |date=29 January 2013 |access-date=10 June 2014 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140714120018/http://www.cancer.org/treatment/understandingyourdiagnosis/examsandtestdescriptions/testingbiopsyandcytologyspecimensforcancer/testing-biopsy-and-cytology-specimens-for-cancer-how-is-cancer-diagnosed |archive-date=14 July 2014}}</ref> | |||

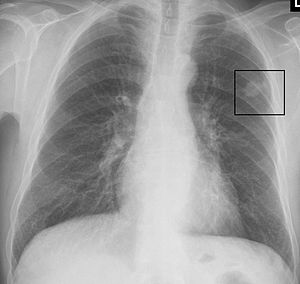

| ] specimen containing a ], here a ] (the whitish tumor near the bronchi).]] | |||

| The risk of developing certain cancers can be reduced by not smoking, maintaining a healthy weight, limiting alcohol intake, eating plenty of vegetables, fruits, and ]s, ] against certain infectious diseases, limiting consumption of ] and ], and limiting exposure to direct sunlight.<ref name=Kushi2012>{{cite journal |vauthors=Kushi LH, Doyle C, McCullough M, Rock CL, Demark-Wahnefried W, Bandera EV, Gapstur S, Patel AV, Andrews K, Gansler T |s2cid=2067308 |title=American Cancer Society Guidelines on nutrition and physical activity for cancer prevention: reducing the risk of cancer with healthy food choices and physical activity |journal= CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians |volume=62 |issue=1 |pages=30–67 |year=2012 |pmid=22237782 |doi=10.3322/caac.20140|doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Parkin DM, Boyd L, Walker LC |title=16. The fraction of cancer attributable to lifestyle and environmental factors in the UK in 2010 |journal=British Journal of Cancer |volume=105 | issue = Suppl 2 |pages=S77–81 |date=December 2011 |pmid=22158327 |pmc=3252065 |doi=10.1038/bjc.2011.489}}</ref> Early detection through screening is useful for ] and ].<ref name=WCR2014Scr>{{cite book |title=World Cancer Report 2014 |date=2014 |publisher=World Health Organization |isbn=978-92-832-0429-9 |url=http://www.searo.who.int/publications/bookstore/documents/9283204298/en/ |pages=Chapter 4.7 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170712114430/http://www.searo.who.int/publications/bookstore/documents/9283204298/en/ |archive-date=12 July 2017 }}</ref> The benefits of ] are controversial.<ref name=WCR2014Scr/><ref name=Got2013>{{cite journal |vauthors=Gøtzsche PC, Jørgensen KJ |title=Screening for breast cancer with mammography |journal=The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews |volume=2013 |issue=6 |pages=CD001877 |date=June 2013 |pmid=23737396 |pmc=6464778 |doi=10.1002/14651858.CD001877.pub5}}</ref> Cancer is often treated with some combination of ], surgery, ] and ].<ref name=WHO2018/><ref name=TCT2018>{{cite web |url=https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/types/targeted-therapies/targeted-therapies-fact-sheet |title=Targeted Cancer Therapies |website=cancer.gov |publisher=National Cancer Institute |date=26 February 2018 |access-date=28 March 2018 }}</ref> Pain and symptom management are an important part of care.<ref name=WHO2018/> ] is particularly important in people with advanced disease.<ref name=WHO2018/> The chance of survival depends on the type of cancer and ] at the start of treatment.<ref name=WCR2014Scr/> In children under 15 at diagnosis, the ] in the ] is on average 80%.<ref name=WCR2014Peads>{{cite book |title=World Cancer Report 2014 |date=2014 |publisher=World Health Organization |isbn=978-92-832-0429-9 |url=http://www.searo.who.int/publications/bookstore/documents/9283204298/en/ |pages=Chapter 1.3 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170712114430/http://www.searo.who.int/publications/bookstore/documents/9283204298/en/ |archive-date=12 July 2017 }}</ref> For cancer in the United States, the average five-year survival rate is 66% for all ages.<ref name=Seer2014>{{cite web |title=SEER Stat Fact Sheets: All Cancer Sites |publisher=National Cancer Institute |url=http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/all.html |access-date=18 June 2014 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100926191037/http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/all.html |archive-date=26 September 2010}}</ref> | |||

| ] specimen containing a ] (the yellowish, spongy-looking tumor in the lower left).]] | |||

| In 2015, about 90.5 million people worldwide had cancer.<ref name=GBD2015Pre>{{cite journal |author=GBD |author-link=Global Burden of Disease Study |collaboration=Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators |title=Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 |journal= The Lancet |date=8 October 2016 |volume=388 |issue=10053 |pages=1545–1602 |pmid=27733282 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6 |pmc=5055577}}</ref> In 2019, annual cancer cases grew by 23.6 million people, and there were 10 million deaths worldwide, representing over the previous decade increases of 26% and 21%, respectively.<ref name=kocarnik /><ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.1146/annurev-cancerbio-030419-033612|doi-access=free|title=Metabolic Drivers in Hereditary Cancer Syndromes|year=2020| vauthors = Sciacovelli M, Schmidt C, Maher ER, Frezza C |journal=Annual Review of Cancer Biology|volume=4|pages=77–97}}</ref> | |||

| '''Cancer''' (medical term: ] ]) is a class of ]s in which a group of ] display ''uncontrolled growth'' (] beyond the normal limits), ''invasion'' (intrusion on and destruction of adjacent tissues), and sometimes '']'' (spread to other locations in the body via lymph or blood). These three ] properties of cancers differentiate them from ]s, which are self-limited, do not invade or metastasize. Most cancers form a ] but some, like ], do not. The branch of medicine concerned with the study, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of cancer is ]. | |||

| The most common types of cancer in males are ], ], ], and ].<ref name=WCR2014>{{cite book |title=World Cancer Report 2014 |date=2014 |publisher=World Health Organization |isbn=978-92-832-0429-9 |pages=Chapter 1.1}}</ref><ref name="auto">{{cite journal | vauthors = Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, Jemal A | title = Cancer statistics, 2023 | journal = CA | volume = 73 | issue = 1 | pages = 17–48 | date = January 2023 | pmid = 36633525 | doi = 10.3322/caac.21763 | doi-access = free }}</ref> In females, the most common types are ], colorectal cancer, lung cancer, and ].<ref name=WCR2014Scr/><ref name=auto/> If ] other than ] were included in total new cancer cases each year, it would account for around 40% of cases.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Dubas LE, Ingraffea A | title = Nonmelanoma skin cancer | journal = Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America | volume = 21 | issue = 1 | pages = 43–53 | date = February 2013 | pmid = 23369588 | doi = 10.1016/j.fsc.2012.10.003 }}</ref><ref name=Cak2012>{{cite journal | vauthors = Cakir BÖ, Adamson P, Cingi C | title = Epidemiology and economic burden of nonmelanoma skin cancer | journal = Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America | volume = 20 | issue = 4 | pages = 419–422 | date = November 2012 | pmid = 23084294 | doi = 10.1016/j.fsc.2012.07.004 }}</ref> In children, ] and ] are most common, except in Africa, where ] occurs more often.<ref name=WCR2014Peads/> In 2012, about 165,000 children under 15 years of age were diagnosed with cancer.<ref name=WCR2014/> The risk of cancer increases significantly with age, and many cancers occur more commonly in developed countries.<ref name=WCR2014Scr/> Rates are increasing as ] and as lifestyle changes occur in the developing world.<ref name=Epi11>{{cite journal | vauthors = Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D | title = Global cancer statistics | journal = CA | volume = 61 | issue = 2 | pages = 69–90 | date = February 2011 | pmid = 21296855 | doi = 10.3322/caac.20107 | s2cid = 30500384 | doi-access = free }}</ref> The global total economic costs of cancer were estimated at ]1.16 trillion (equivalent to ${{Inflation|US|1.16|2010|r=2}} trillion in {{Inflation/year|US}}) per year {{as of|2010|lc=y}}.<ref name=WCR2014Eco>{{cite book |title=World Report 2014 |date=2014 |publisher=World Health Organization |isbn=978-92-832-0429-9 |url=http://www.searo.who.int/publications/bookstore/documents/9283204298/en/ |pages=Chapter 6.7 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170712114430/http://www.searo.who.int/publications/bookstore/documents/9283204298/en/ |archive-date=12 July 2017 }}</ref> | |||

| Cancer may affect people at all ages, even ]es, but the risk for most varieties increases with age.<ref name="Cancer Research UK">{{cite web | last =Cancer Research UK | title =UK cancer incidence statistics by age | month=January | year=2007 | url =http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/incidence/age/ | accessdate =2007-06-25 }}</ref> Cancer causes about 13% of ].<ref name="WHO">{{cite web | last =WHO | authorlink =World Health Organization | title =Cancer | publisher =World Health Organization |month=February | year=2006 | url =http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/ | accessdate =2007-06-25 }}</ref> According to the ], 7.6 million people died from cancer in the world during 2007.<ref name="American Cancer Society">{{cite web | last =American Cancer Society | authorlink =Reuters | title =Report sees 7.6 million global 2007 cancer deaths | publisher =Reuters |month=December | year=2007 | url =http://today.reuters.com/news/articlenews.aspx?type=healthNews&storyid=2007-12-17T052342Z_01_N16330649_RTRUKOC_0_US-CANCER-WORLD.xml | accessdate =2007-12-17 }}</ref> Cancers can affect all animals. | |||

| ])]] | |||

| Nearly all cancers are caused by abnormalities in the ] of the ] cells. These abnormalities may be due to the effects of ], such as ], ], ], or ]. Other cancer-promoting genetic abnormalities may be randomly acquired through errors in ], or are ], and thus present in all cells from birth. The ] of cancers are usually affected by complex interactions between carcinogens and the host's ]. New aspects of the genetics of cancer pathogenesis, such as ], and ] are increasingly recognized as important. | |||

| {{TOC limit}} | |||

| Genetic abnormalities found in cancer typically affect two general classes of genes. Cancer-promoting '']s'' are typically activated in cancer cells, giving those cells new properties, such as hyperactive growth and division, protection against ], loss of respect for normal tissue boundaries, and the ability to become established in diverse tissue environments. '']s'' are then inactivated in cancer cells, resulting in the loss of normal functions in those cells, such as accurate DNA replication, control over the ], orientation and adhesion within tissues, and interaction with protective cells of the ]. | |||

| == Etymology and definitions == | |||

| The word comes from the ancient Greek καρκίνος, meaning 'crab' and 'tumor'. Greek physicians ] and ], among others, noted the similarity of crabs to some tumors with swollen veins. The word was introduced in English in the modern medical sense around 1600.<ref>{{Cite web |title=cancer |url=https://www.etymonline.com/word/cancer |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221107103233/https://www.etymonline.com/word/cancer |archive-date=7 November 2022 |website=www.etymonline.com}}</ref> | |||

| Diagnosis usually requires the ] examination of a tissue ] specimen by a ], although the initial indication of malignancy can be symptoms or ] imaging abnormalities. Most cancers can be treated and some cured, depending on the specific type, location, and ]. Once diagnosed, cancer is usually treated with a combination of ], ] and ]. As research develops, treatments are becoming more specific for different varieties of cancer. There has been significant progress in the development of ] drugs that act specifically on detectable molecular abnormalities in certain tumors, and which minimize damage to normal cells. The prognosis of cancer patients is most influenced by the type of cancer, as well as the ], or extent of the disease. In addition, ] ] and the presence of specific molecular markers can also be useful in establishing prognosis, as well as in determining individual treatments. | |||

| Cancers comprise a large family of diseases that involve abnormal ] with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body.<ref name=WHO2018/><ref name=WhatIsCancerNCI/> They form a subset of ]s. A neoplasm or tumor is a group of cells that have undergone unregulated growth and will often form a mass or lump, but may be distributed diffusely.<ref name=ACSglossary>{{cite web |title=Cancer Glossary |website=cancer.org |publisher=American Cancer Society |url=http://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancerglossary/index |access-date=11 September 2013 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130901160014/http://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancerglossary/index |archive-date=1 September 2013}}</ref><ref name=NCIdefinition>{{cite web |title=What is cancer? |website=cancer.gov |publisher=National Cancer Institute |access-date=28 March 2018 |url=https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/what-is-cancer|date=17 September 2007}}</ref> | |||

| ==Classification== | |||

| Cancer is generally classified according to the tissue from which the cancerous cells originate, the primary tumor, as well as the normal cell type they most resemble. These are location and histology, respectively. | |||

| All tumor cells show the ]. These characteristics are required to produce a malignant tumor. They include:<ref name=Han2000/> | |||

| * ] and division absent the proper signals | |||

| ===Nomenclature=== | |||

| * Continuous growth and division even given contrary signals | |||

| The following closely related terms may be used to designate abnormal growths: | |||

| * Avoidance of ] | |||

| * ''']:''' originally, it meant any abnormal swelling, lump or mass. In current English, however, the word tumor has become synonymous with neoplasm, specifically solid neoplasm. Note that some neoplasms, such as ], do not form tumors. | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ''']:''' the scientific term to describe an abnormal proliferation of genetically altered cells. Neoplasms can be benign or malignant: | |||

| * Promoting ] | |||

| ** '''Malignant neoplasm''' or '''malignant tumor''': synonymous with '''cancer'''. | |||

| * ] of tissue and formation of ]<ref name=Han2000/> | |||

| ** '''Benign neoplasm''' or ''']''': a tumor (solid neoplasm) that stops growing by itself, does not invade other tissues and does not form metastases. | |||

| * '''Invasive''' tumor is another synonym of '''cancer'''. The name refers to invasion of surrounding tissues. | |||

| The progression from normal cells to cells that can form a detectable mass to cancer involves multiple steps known as malignant progression.<ref name=Han2000>{{cite journal |vauthors=Hanahan D, Weinberg RA |s2cid=1478778 |title=The hallmarks of cancer |journal=Cell |volume=100 |issue=1 |pages=57–70 |date=January 2000 |pmid=10647931 |doi=10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81683-9 |author-link1=Douglas Hanahan |author-link2=Robert Weinberg (biologist)|doi-access=free }}</ref><ref name=Han2011>{{cite journal |vauthors=Hanahan D, Weinberg RA |title=Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation |journal=Cell |volume=144 |issue=5 |pages=646–74 |date=March 2011 |pmid=21376230 |doi=10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013|doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| * '''Pre-malignancy''', '''pre-cancer''' or '''non-invasive''' tumor: A neoplasm that is not invasive but has the potential to progress to cancer (become invasive) if left untreated. These lesions are, in order of increasing potential for cancer, ], ] and ]. | |||

| The following terms can be used to describe a cancer: | |||

| * '''Screening''': a test done on healthy people to detect tumors before they become apparent. A ] is a screening test. | |||

| * '''Diagnosis''': the confirmation of the cancerous nature of a lump. This usually requires a ] or removal of the tumor by ], followed by examination by a ]. | |||

| * '''Surgical excision''': the removal of a tumor by a ]. | |||

| ** '''Surgical margins''': the evaluation by a ] of the edges of the tissue removed by the surgeon to determine if the tumor was removed completely ("negative margins") or if tumor was left behind ("positive margins"). | |||

| * '''Grade''': a number (usually on a scale of 3) established by a ] to describe the degree of resemblance of the tumor to the surrounding benign tissue. | |||

| * '''Stage''': a number (usually on a scale of 4) established by the ] to describe the degree of invasion of the body by the tumor. | |||

| * '''Recurrence''': new tumors that appear at the site of the original tumor after surgery. | |||

| * '''Metastasis''': new tumors that appear far from the original tumor. | |||

| * '''Transformation:''' the concept that a low-grade tumor transforms to a high-grade tumor over time. Example: ]. | |||

| * '''Chemotherapy''': treatment with drugs. | |||

| * '''Radiation therapy''': treatment with radiations. | |||

| * '''Adjuvant''' therapy: treatment, either chemotherapy or radiation therapy, given after surgery to kill the remaining cancer cells. | |||

| * '''Prognosis''': the probability of cure after the therapy. It is usually expressed as a probability of survival five years after diagnosis. Alternatively, it can be expressed as the number of years when 50% of the patients are still alive. Both numbers are derived from statistics accumulated with hundreds of similar patients to give a ]. | |||

| Cancers are classified by the type of cell that resembles the tumor and, therefore, the tissue presumed to be the origin of the tumor. Examples of general categories include: | |||

| * ''']:''' Malignant tumors derived from ] cells. This group represents the most common cancers, including the common forms of ], ], ] and ]. | |||

| * ''']:''' Malignant tumors derived from ], or ] cells. | |||

| * ''']''' and ''']:''' Malignancies derived from hematopoietic (]-forming) cells | |||

| * ''']:''' Tumors derived from ] cells. In adults most often found in the ] and ]; in fetuses, babies, and young children most often found on the body midline, particularly at the tip of the tailbone; in horses most often found at the poll (base of the skull). | |||

| * '''Blastic tumor or ]:''' A tumor (usually malignant) which resembles an immature or embryonic tissue. Many of these tumors are most common in children. | |||

| Malignant tumors (cancers) are usually named using '''-carcinoma''', '''-sarcoma''' or '''-blastoma''' as a suffix, with the Latin or Greek word for the organ of origin as the root. For instance, a cancer of the liver is called '']''; a cancer of the fat cells is called ''liposarcoma''. For common cancers, the English organ name is used. For instance, the most common type of ] is called ''ductal carcinoma of the breast'' or ''mammary ductal carcinoma''. Here, the adjective ''ductal'' refers to the appearance of the cancer under the microscope, resembling normal breast ducts. | |||

| ]s (which are not cancers) are named using '''-oma''' as a suffix with the organ name as the root. For instance, a benign tumor of the smooth muscle of the uterus is called ''leiomyoma'' (the common name of this frequent tumor is ''fibroid''). Unfortunately, some cancers also use the '''-oma''' suffix, examples being ] and ]. | |||

| ===Adult cancers=== | |||

| In the U.S. and other developed countries, cancer is presently responsible for about 25% of all deaths.<ref name="CACancerJClin2005-Jemal"> | |||

| {{cite journal | author=Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E, Samuels A, Tiwari RC, Ghafoor A, Feuer EJ, Thun MJ | title=Cancer statistics, 2005 | journal=CA Cancer J Clin | year=2005 | pages=10–30 | volume=55 | issue=1 | url=http://caonline.amcancersoc.org/cgi/content/full/55/1/10 | pmid=15661684 | doi=10.3322/canjclin.55.1.10 | doi_brokendate=2008-06-26}}</ref> On a yearly basis, 0.5% of the population is diagnosed with cancer. The statistics below are for adults in the United States, and may vary substantially in other countries: | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| ! colspan="2" | <big>Male</big> | |||

| | rowspan="7" | | |||

| ! colspan="2" | <big>Female</big> | |||

| |- | |||

| ! width="170px" | most common (by occurrence) !! width="170px" | most common (by mortality)<ref name="CACancerJClin2005-Jemal" /> | |||

| ! width="170px" | most common (by occurrence)!! width="170px" | most common (by mortality)<ref name="CACancerJClin2005-Jemal" /> | |||

| |- | |||

| |] (33%) || lung cancer (31%) || ] (32%) || lung cancer (27%) | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] (13%) || prostate cancer (10%) || lung cancer (12%) || breast cancer (15%) | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] (10%) || colorectal cancer (10%) || colorectal cancer (11%) || colorectal cancer (10%) | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] (7%) || ] (5%) || ] (6%) || ] (6%) | |||

| |- | |||

| | cutaneous ] (5%) || ] (4%) || ] (4%) || pancreatic cancer (6%) | |||

| |} | |||

| ===Child cancers=== | |||

| Cancer can also occur in young children and adolescents, but it is rare (about 150 cases per million yearly in the US). Statistics from the SEER program of the US ] demonstrate that childhood cancers increased 19% between 1975 and 1990, mainly due to an increased incidence in ]. Since 1990, incidence rates have decreased.<ref name="SEER1999">James G. Gurney, Malcolm A. Smith, Julie A. Ross (1999) ''Cancer Incidence and Survival among Children and Adolescents, United States SEER program 1975-1995'', Cancer Statistics Branch, National Cancer Institute, available online from the </ref> | |||

| There is a reasonable doubt that children living near ] face an increased risk of cancer.<ref>http://www.globalresearch.ca/index.php?context=va%26aid=8785</ref> | |||

| ===Infant cancers=== | |||

| The age of peak incidence of cancer in children occurs during the first year of life, in ]s. The average annual incidence in the United States, 1975-1995, was 233 per million infants.<ref name="SEER1999"/> Several estimates of incidence exist. According to SEER,<ref name="SEER1999"/> in the United States: | |||

| *] comprised 28% of infant cancer cases and was the most common malignancy among these young children (65 per million infants). | |||

| *The ] as a group (41 per million infants) represented the next most common type of cancer, comprising 17% of all cases. | |||

| *] comprised 13% of infant cancer, with an average annual incidence rate of nearly 30 per million infants. | |||

| *The average annual incidence rates for malignant germ cell and malignant soft tissue tumors were essentially the same at 15 per million infants. Each comprised about 6% of infant cancer. | |||

| According to another study:<ref name="CACancerJClin2005-Jemal" /> | |||

| *] (usually ]) is the most common infant malignancy (30%), followed by the ] and ]. The remainder consists of ], ]s, ] (arising from muscle), ], ] and ]. | |||

| ] (a ]) often is cited as the most common tumor in this age group, but most teratomas are surgically removed while still benign, hence not necessarily cancer. Prior to the widespread routine use of prenatal ultrasound examinations, the incidence of ]s diagnosed at birth was 25 to 29 per million births<!-- 1:40,000 to 1:35,000 -->. | |||

| Female and male infants have essentially the same overall cancer incidence rates, a notable difference compared to older children. | |||

| White infants have higher cancer rates than black infants. Leukemias accounted for a substantial proportion of this difference: the average annual rate for white infants (48.7 per million) was 66% higher than for | |||

| black infants (29.4 per million).<ref name="SEER1999"/> | |||

| Relative survival for infants is very good for neuroblastoma, ] and ], and fairly good (80%) for leukemia, but not for most other types of cancer. | |||

| == Signs and symptoms == | == Signs and symptoms == | ||

| {{Main|Signs and symptoms of cancer}} | |||

| Roughly, cancer symptoms can be divided into three groups: | |||

| ] depend on the location of the tumor.]] | |||

| * ''Local symptoms'': unusual lumps or swelling ('']''), ] (bleeding), ] and/or ]ation. Compression of surrounding tissues may cause symptoms such as ] (yellowing the eyes and skin). | |||

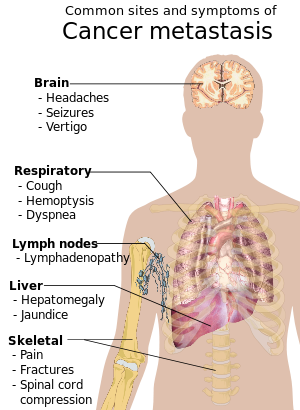

| * ''Symptoms of ] (spreading)'': enlarged ]s, ] and ], ] (enlarged ]), bone pain, ] of affected bones and ] symptoms. Although advanced cancer may cause ], it is often not the first symptom. | |||

| When cancer begins, it produces no symptoms. Signs and symptoms appear as the mass grows or ]. The findings that result depend on cancer's type and location. Few symptoms are ]. Many frequently occur in individuals who have other conditions. Cancer can be difficult to diagnose and can be considered a "]".<ref name=Card10/> | |||

| * ''Systemic symptoms'': ], ], ] and ] (]), excessive ] (]), ] and specific ], i.e. specific conditions that are due to an active cancer, such as ] or hormonal changes. | |||

| People may become anxious or depressed post-diagnosis. The risk of suicide in people with cancer is approximately double.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Anguiano L, Mayer DK, Piven ML, Rosenstein D |s2cid=45874503 |title=A literature review of suicide in cancer patients |journal=Cancer Nursing |volume=35 |issue=4 |pages=E14–26 |date=July–August 2012 |pmid=21946906 |doi=10.1097/NCC.0b013e31822fc76c|doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| Every symptom in the above list can be caused by a variety of conditions (a list of which is referred to as the ]). Cancer may be a common or uncommon cause of each item. | |||

| == |

=== Local symptoms === | ||

| Local symptoms may occur due to the mass of the tumor or its ulceration. For example, mass effects from lung cancer can block the ] resulting in cough or ]; ] can cause narrowing of the ], making it difficult or painful to swallow; and ] may lead to narrowing or blockages in the ], affecting bowel habits. Masses in breasts or testicles may produce observable lumps. ] can cause bleeding that can lead to symptoms such as ] (lung cancer), ] or ] (colon cancer), ] (bladder cancer), or ] (endometrial or cervical cancer). Although localized pain may occur in advanced cancer, the initial tumor is usually painless. Some cancers can cause a buildup of fluid within the chest or ].<ref name="Card10">Holland Chp. 1</ref> | |||

| Most cancers are initially recognized either because signs or symptoms appear or through screening. Neither of these lead to a definitive diagnosis, which usually requires the opinion of a ], a type of physician (medical doctor) who specializes in the diagnosis of cancer and other diseases. | |||

| === |

=== Systemic symptoms === | ||

| Systemic symptoms may occur due to the body's response to the cancer. This may include fatigue, unintentional weight loss, or skin changes.<ref>{{cite book | vauthors = O'Dell M, Stubblefield M |title=Cancer rehabilitation principles and practice |year=2009 |publisher=Demos Medical |location=New York |isbn=978-1-933864-33-4 |page=983 |url={{google books |plainurl=y |id=_JaPlNYgXkEC |page=983}}}}</ref> Some cancers can cause a systemic inflammatory state that leads to ongoing muscle loss and weakness, known as ].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Fearon K, Strasser F, Anker SD, Bosaeus I, Bruera E, Fainsinger RL, Jatoi A, Loprinzi C, MacDonald N, Mantovani G, Davis M, Muscaritoli M, Ottery F, Radbruch L, Ravasco P, Walsh D, Wilcock A, Kaasa S, Baracos VE | title = Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: an international consensus | journal = The Lancet. Oncology | volume = 12 | issue = 5 | pages = 489–95 | date = May 2011 | pmid = 21296615 | doi = 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70218-7 }}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Some cancers, such as ], ]s, and ] or ]s, can cause a persistent ].<ref name=Card10/> | |||

| People with suspected cancer are investigated with ]s. These commonly include ]s, ]s, ]s and ]. | |||

| Shortness of breath, called ], is a common symptom of cancer and its treatment. The causes of cancer-related dyspnea can include tumors in or around the lung, blocked airways, fluid in the lungs, pneumonia, or treatment reactions including an ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Shortness of Breath {{!}} Cancer-related Side Effects |url=https://www.cancer.org/cancer/managing-cancer/side-effects/shortness-of-breath.html |access-date=10 October 2023 |website=www.cancer.org |language=en}}</ref> Treatment for dyspnea in patients with advanced cancer can include ], bilevel ventilation, ]/] and multicomponent ].<ref>{{Cite book | vauthors = Dy SM, Gupta A, Waldfogel JM, Sharma R, Zhang A, Feliciano JL, Sedhom R, Day J, Gersten RA, Davidson PM, Bass EB |url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK565137/ |title=Interventions for Breathlessness in Patients With Advanced Cancer |date=2020 |publisher=Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US) |series=AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Reviews |location=Rockville (MD) |pmid=33289989}}</ref> | |||

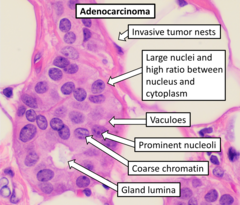

| === Biopsy === | |||

| A cancer may be suspected for a variety of reasons, but the definitive diagnosis of most malignancies must be confirmed by ] examination of the cancerous cells by a ]. Tissue can be obtained from a ] or ]. Many biopsies (such as those of the skin, breast or liver) can be done in a doctor's office. Biopsies of other organs are performed under ] and require ] in an ]. | |||

| Some systemic symptoms of cancer are caused by hormones or other molecules produced by the tumor, known as ]. Common paraneoplastic syndromes include ], which can cause ], constipation and dehydration, or ], which can also cause altered mental status, vomiting, headaches, or seizures.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Dimitriadis GK, Angelousi A, Weickert MO, Randeva HS, Kaltsas G, Grossman A | title = Paraneoplastic endocrine syndromes | journal = Endocrine-Related Cancer | volume = 24 | issue = 6 | pages = R173–R190 | date = June 2017 | pmid = 28341725 | doi = 10.1530/ERC-17-0036 | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| The tissue ] given by the pathologist indicates the type of cell that is proliferating, its ] and other features of the tumor. Together, this information is useful to evaluate the ] of this patient and to choose the best treatment. ] and ] are other types of testing that the pathologist may perform on the tissue specimen. These tests may provide information about future behavior of the cancer (prognosis) and best treatment. | |||

| === Metastasis === | |||

| {{Main|Metastasis}} | |||

| == Treatment == | |||

| ] is the spread of cancer to other locations in the body. The dispersed tumors are called metastatic tumors, while the original is called the primary tumor. Almost all cancers can metastasize.<ref name=metastasis/> Most cancer deaths are due to cancer that has metastasized.<ref name="What is Metastasized Cancer">{{cite web |title=What is Metastasized Cancer? |url=http://www.nccn.com/component/content/article/54-cancer-basics/925-what-is-metastasized-cancer.html |website=National Comprehensive Cancer Network |access-date=18 July 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130707200430/http://www.nccn.com/component/content/article/54-cancer-basics/925-what-is-metastasized-cancer.html |archive-date=7 July 2013}}</ref> | |||

| Cancer can be treated by ], ], ], ], ] or other methods. The choice of therapy depends upon the location and grade of the tumor and the ] of the disease, as well as the general state of the patient (]). A number of ]s are also under development. | |||

| Metastasis is common in the late stages of cancer and it can occur via the blood or the ] or both. The typical steps in metastasis are: | |||

| Complete removal of the cancer without damage to the rest of the body is the goal of treatment. Sometimes this can be accomplished by surgery, but the propensity of cancers to invade adjacent tissue or to spread to distant sites by microscopic metastasis often limits its effectiveness. The effectiveness of chemotherapy is often limited by toxicity to other tissues in the body. Radiation can also cause damage to normal tissue. | |||

| # Local ] | |||

| Because "cancer" refers to a class of diseases, it is unlikely that there will ever be a single "]" any more than there will be a single treatment for all ]s. | |||

| # ] into the blood or lymph. | |||

| # Circulation through the body. | |||

| === Surgery === | |||

| # ] into the new tissue. | |||

| In theory, non-] cancers can be cured if entirely removed by ], but this is not always possible. When the cancer has ] to other sites in the body prior to surgery, complete surgical excision is usually impossible. In the ]ian model of cancer progression, tumors grow locally, then spread to the lymph nodes, then to the rest of the body. This has given rise to the popularity of local-only treatments such as surgery for small cancers. Even small localized tumors are increasingly recognized as possessing metastatic potential. | |||

| # Proliferation | |||

| # ] | |||

| Examples of surgical procedures for cancer include ] for breast cancer and ] for prostate cancer. The goal of the surgery can be either the removal of only the tumor, or the entire organ. A single cancer cell is invisible to the naked eye but can regrow into a new tumor, a process called recurrence. For this reason, the ] will examine the surgical specimen to determine if a margin of healthy tissue is present, thus decreasing the chance that microscopic cancer cells are left in the patient. | |||

| Different types of cancers tend to metastasize to particular organs. Overall, the most common places for metastases to occur are the ]s, ], brain, and the ]s.<ref name="metastasis">{{cite web |url=https://www.cancer.gov/types/metastatic-cancer |title=Metastatic Cancer: Questions and Answers |access-date=28 March 2018|publisher=National Cancer Institute |date=12 May 2015}}</ref> | |||

| In addition to removal of the primary tumor, surgery is often necessary for ], e.g. determining the extent of the disease and whether it has ] to regional ]s. Staging is a major determinant of ] and of the need for ]. | |||

| While some cancers can be cured if detected early, metastatic cancer is more difficult to treat and control. Nevertheless, some recent treatments are demonstrating encouraging results.<ref>{{cite web |title=Why is cancer so hard to cure? |url=https://www.theage.com.au/national/why-is-cancer-so-hard-to-cure-20230626-p5djiw.html |access-date=17 July 2023 |website=The Age|date=15 July 2023 }}</ref> | |||

| Occasionally, surgery is necessary to control symptoms, such as ] or ]. This is referred to as ]. | |||

| === Radiation therapy === | |||

| {{main|Radiation therapy}} | |||

| ] (also called radiotherapy, X-ray therapy, or irradiation) is the use of ionizing radiation to kill cancer cells and shrink tumors. Radiation therapy can be administered externally via ] (EBRT) or internally via ]. The effects of radiation therapy are localised and confined to the region being treated. Radiation therapy injures or destroys cells in the area being treated (the "target tissue") by damaging their genetic material, making it impossible for these cells to continue to grow and divide. Although radiation damages both cancer cells and normal cells, most normal cells can recover from the effects of radiation and function properly. The goal of radiation therapy is to damage as many cancer cells as possible, while limiting harm to nearby healthy tissue. Hence, it is given in many fractions, allowing healthy tissue to recover between fractions. | |||

| Radiation therapy may be used to treat almost every type of solid tumor, including cancers of the brain, breast, cervix, larynx, lung, pancreas, prostate, skin, stomach, uterus, or soft tissue sarcomas. Radiation is also used to treat leukemia and lymphoma. Radiation dose to each site depends on a number of factors, including the radiosensitivity of each cancer type and whether there are tissues and organs nearby that may be damaged by radiation. Thus, as with every form of treatment, radiation therapy is not without its side effects. | |||

| === Chemotherapy === | |||

| {{main|Chemotherapy}} | |||

| ] is the treatment of cancer with ] ("anticancer drugs") that can destroy cancer cells. In current usage, the term "chemotherapy" usually refers to ''cytotoxic'' drugs which affect rapidly dividing cells in general, in contrast with ''targeted therapy'' (see below). Chemotherapy drugs interfere with cell division in various possible ways, e.g. with the duplication of ] or the separation of newly formed ]s. Most forms of chemotherapy target all rapidly dividing cells and are not specific for cancer cells, although some degree of specificity may come from the inability of many cancer cells to repair ], while normal cells generally can. Hence, chemotherapy has the potential to harm healthy tissue, especially those tissues that have a high replacement rate (e.g. intestinal lining). These cells usually repair themselves after chemotherapy. | |||

| Because some drugs work better together than alone, two or more drugs are often given at the same time. This is called "combination chemotherapy"; most chemotherapy regimens are given in a combination. | |||

| The treatment of some ]s and ]s requires the use of high-dose chemotherapy, and ] (TBI). This treatment ablates the bone marrow, and hence the body's ability to recover and repopulate the blood. For this reason, bone marrow, or peripheral blood stem cell harvesting is carried out before the ablative part of the therapy, to enable "rescue" after the treatment has been given. This is known as autologous ]. Alternatively, ] may be transplanted from a matched unrelated donor (MUD). | |||

| === Targeted therapies === | |||

| {{main|Targeted therapy}} | |||

| Targeted therapy, which first became available in the late 1990s, has had a significant impact in the treatment of some types of cancer, and is currently a very active research area. This constitutes the use of agents specific for the deregulated proteins of cancer cells. Small molecule targeted therapy drugs are generally inhibitors of ] domains on mutated, overexpressed, or otherwise critical proteins within the cancer cell. Prominent examples are the tyrosine kinase inhibitors ] and ]. | |||

| ] is another strategy in which the therapeutic agent is an ] which specifically binds to a protein on the surface of the cancer cells. Examples include the anti-] antibody ] (Herceptin) used in breast cancer, and the anti-CD20 antibody ], used in a variety of ] malignancies. | |||

| ] can also involve small ]s as "homing devices" which can bind to cell surface receptors or affected ] surrounding the tumor. Radionuclides which are attached to this peptides (e.g. RGDs) eventually kill the cancer cell if the nuclide decays in the vicinity of the cell. Especially oligo- or multimers of these binding motifs are of great interest, since this can lead to enhanced tumor specificity and avidity. | |||

| ] (PDT) is a ternary treatment for cancer involving a photosensitizer, tissue oxygen, and light (often using ]). PDT can be used as treatment for ] (BCC) or ]; PDT can also be useful in removing traces of malignant tissue after surgical removal of large tumors.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Dolmans |first=DE |coauthors=Fukumura D, Jain RK |year=2003 |month=May |title=Photodynamic therapy for cancer |journal=Nat Rev Cancer |volume=3 |issue=5 |pages=380–7 |pmid=12724736 |url=http://www.nature.com/nrc/journal/v3/n5/abs/nrc1071_fs.html |doi=10.1038/nrc1071}}</ref> | |||

| === Immunotherapy === | |||

| {{main|Cancer immunotherapy}} | |||

| Cancer immunotherapy refers to a diverse set of therapeutic strategies designed to induce the patient's own ] to fight the tumor. Contemporary methods for generating an immune response against tumours include intravesical ] immunotherapy for superficial bladder cancer, and use of ]s and other ]s to induce an immune response in ] and ] patients. ]s to generate specific ]s are the subject of intensive research for a number of tumours, notably ] and ]. ] is a vaccine-like strategy in late clinical trials for ] in which ]s from the patient are loaded with ] peptides to induce a specific immune response against prostate-derived cells. | |||

| Allogeneic ] ("bone marrow transplantation" from a genetically non-identical donor) can be considered a form of immunotherapy, since the donor's immune cells will often attack the tumor in a phenomenon known as ]. For this reason, allogeneic HSCT leads to a higher cure rate than autologous transplantation for several cancer types, although the side effects are also more severe. | |||

| === Hormonal therapy === | |||

| {{main|Hormonal therapy (oncology)}} | |||

| The growth of some cancers can be inhibited by providing or blocking certain hormones. Common examples of hormone-sensitive tumors include certain types of breast and prostate cancers. Removing or blocking ] or ] is often an important additional treatment. In certain cancers, administration of hormone agonists, such as ]s may be therapeutically beneficial. | |||

| ===Angiogenesis inhibitors=== | |||

| {{Main|Angiogenesis inhibitor}} | |||

| Angiogenesis inhibitors prevent the extensive growth of blood vessels (]) that tumors require to survive. Some, such as ], have been approved and are in clinical use. One of the main problems with anti-angiogenesis drugs is that many factors stimulate blood vessel growth, in normal cells and cancer. Anti-angiogenesis drugs only target one factor, so the other factors continue to stimulate blood vessel growth. Other problems include ], maintenance of stability and activity and targeting at the tumor vasculature.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Kleinman HK, Liau G |title=Gene therapy for antiangiogenesis |journal=J. Natl. Cancer Inst. |volume=93 |issue=13 |pages=965–7 |year=2001 |month=July |pmid=11438554 |doi=10.1093/jnci/93.13.965 |url=http://jnci.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/93/13/965}}</ref> | |||

| === Symptom control === | |||

| Although the control of the symptoms of cancer is not typically thought of as a treatment directed at the cancer, it is an important determinant of the ] of cancer patients, and plays an important role in the decision whether the patient is able to undergo other treatments. Although doctors generally have the therapeutic skills to reduce pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, hemorrhage and other common problems in cancer patients, the multidisciplinary specialty of ] has arisen specifically in response to the symptom control needs of this group of patients. | |||

| ], such as ] and ], and ]s, drugs to suppress nausea and vomiting, are very commonly used in patients with cancer-related symptoms. Improved ] such as ] and analogues, as well as ] have made aggressive treatments much more feasible in cancer patients. | |||

| ] due to cancer is almost always associated with continuing tissue damage due to the disease process or the treatment (i.e. surgery, radiation, chemotherapy). Although there is always a role for environmental factors and affective disturbances in the genesis of pain behaviors, these are not usually the predominant etiologic factors in patients with cancer pain. Furthermore, many patients with severe pain associated with cancer are nearing the end of their lives and ] therapies are required. Issues such as social stigma of using ], work and functional status, and health care consumption are not likely to be important in the overall case management. Hence, the typical strategy for cancer pain management is to get the patient as comfortable as possible using opioids and other medications, surgery, and physical measures. Doctors have been reluctant to prescribe narcotics for pain in terminal cancer patients, for fear of contributing to addiction or suppressing respiratory function. The ] movement, a more recent offshoot of the ] movement, has engendered more widespread support for preemptive pain treatment for cancer patients. | |||

| ] is a very common problem for cancer patients, and has only recently become important enough for oncologists to suggest treatment, even though it plays a significant role in many patients' quality of life. | |||

| === Treatment trials === | |||

| {{Main|Experimental cancer treatment}} | |||

| ]s, also called research studies, test new treatments in people with cancer. The goal of this research is to find better ways to treat cancer and help cancer patients. Clinical trials test many types of treatment such as new drugs, new approaches to surgery or radiation therapy, new combinations of treatments, or new methods such as ]. | |||

| A clinical trial is one of the final stages of a long and careful cancer research process. The search for new treatments begins in the laboratory, where scientists first develop and test new ideas. If an approach seems promising, the next step may be testing a treatment in animals to see how it affects cancer in a living being and whether it has harmful effects. Of course, treatments that work well in the lab or in animals do not always work well in people. Studies are done with cancer patients to find out whether promising treatments are safe and effective. | |||

| Patients who take part may be helped personally by the treatment they receive. They get up-to-date care from cancer experts, and they receive either a new treatment being tested or the best available standard treatment for their cancer. At the same time, new treatments also may have unknown risks, but if a new treatment proves effective or more effective than standard treatment, study patients who receive it may be among the first to benefit. There is no guarantee that a new treatment being tested or a standard treatment will produce good results. In children with cancer, a survey of trials found that those enrolled in trials were on average not more likely to do better or worse than those on standard treatment; this confirms that success or failure of an experimental treatment cannot be predicted.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Kumar A, Soares H, Wells R, ''et al'' |title=Are experimental treatments for cancer in children superior to established treatments? Observational study of randomised controlled trials by the Children's Oncology Group |journal=BMJ |volume=331 |issue=7528 |pages=1295 |year=2005 |month=December |pmid=16299015 |pmc=1298846 |doi=10.1136/bmj.38628.561123.7C |url=http://bmj.bmjjournals.com/cgi/content/full/331/7528/1295}}</ref> | |||

| === Complementary and alternative === | |||

| {{Main|Unproven cancer therapy}} | |||

| ] (CAM) treatments are the diverse group of medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not part of conventional medicine.<ref name="mnalt">{{cite journal |author=Cassileth BR, Deng G |title=Complementary and alternative therapies for cancer |journal=Oncologist |volume=9 |issue=1 |pages=80–9 |year=2004 |pmid=14755017 |url=http://theoncologist.alphamedpress.org/cgi/content/full/9/1/80 |doi=10.1634/theoncologist.9-1-80}}</ref> "Complementary medicine" refers to methods and substances used along with conventional medicine, while "alternative medicine" refers to compounds used instead of conventional medicine.<ref> ]. retrieved ] ].</ref> CAM use is common among people with cancer; a 2000 study found that 69% cancer patients had used at least one CAM therapy as part of their cancer treatment.<ref name=Richardson2000>{{cite journal |author=Richardson MA, Sanders T, Palmer JL, Greisinger A, Singletary SE |title=Complementary/alternative medicine use in a comprehensive cancer center and the implications for oncology |journal=J. Clin. Oncol. |volume=18 |issue=13 |pages=2505–14 |year=2000 |month=July |pmid=10893280 |url=http://jco.ascopubs.org/cgi/content/full/18/13/2505}}</ref> Most complementary and alternative medicines for cancer have not been rigorously studied or tested. Some alternative treatments which have been investigated and shown to be ineffective continue to be marketed and promoted.<ref name="pmid15061600">{{cite journal |author=Vickers A |title=Alternative cancer cures: "unproven" or "disproven"? |journal=CA Cancer J Clin |volume=54 |issue=2 |pages=110–8 |year=2004 |pmid=15061600 |doi= |url=http://caonline.amcancersoc.org/cgi/content/full/54/2/110}}</ref> | |||

| == Prognosis == | |||

| Cancer has a reputation for being a deadly disease. While this certainly applies to certain particular types, the truths behind the historical connotations of cancer are increasingly being overturned by advances in medical care. Some types of cancer have a prognosis that is substantially better than nonmalignant diseases such as ] and ]. | |||

| Progressive and disseminated malignant disease has a substantial impact on a cancer patient's quality of life, and many cancer treatments (such as ]) may have severe side-effects. In the advanced stages of cancer, many patients need extensive care, affecting family members and friends. ] solutions may include permanent or "respite" hospice nursing. | |||

| === Emotional impact === | |||

| Many local organizations offer a variety of practical and support services to people with cancer. Support can take the form of ], ], advice, financial assistance, transportation to and from treatment, films or information about cancer. Neighborhood organizations, local health care providers, or area hospitals may have resources or services available. | |||

| Counseling can provide emotional support to cancer patients and help them better understand their illness. Different types of counseling include individual, group, family, peer counseling, bereavement, patient-to-patient, and sexuality. | |||

| Many governmental and charitable organizations have been established to help patients cope with cancer. These organizations often are involved in cancer prevention, cancer treatment, and cancer research. | |||

| == Causes == | == Causes == | ||

| {{Main|Causes of cancer}} | |||

| {{main|Carcinogenesis}} | |||

| ] for carcinogenic substances]] | |||

| ] | |||

| Cancer is a diverse class of diseases which differ widely in their causes and biology. The common thread in all known cancers is the acquisition of abnormalities in the genetic material of the cancer cell and its progeny. Research into the pathogenesis of cancer can be divided into three broad areas of focus. The first area of research focuses on the agents and events which cause or facilitate genetic changes in cells destined to become cancer. Second, it is important to uncover the precise nature of the genetic damage, and the genes which are affected by it. The third focus is on the consequences of those genetic changes on the biology of the cell, both in generating the defining properties of a cancer cell, and in facilitating additional genetic events, leading to further progression of the cancer. | |||

| The majority of cancers, some 90–95% of cases, are due to genetic mutations from environmental and lifestyle factors.<ref name=Enviro2008/> The remaining 5–10% are due to ].<ref name=Enviro2008/> '']'' refers to any cause that is not ], such as lifestyle, economic, and behavioral factors and not merely pollution.<ref name="isbn0-387-78192-7">{{cite book | vauthors = Manton K, Akushevich I, Kravchenko J |title=Cancer Mortality and Morbidity Patterns in the U.S. Population: An Interdisciplinary Approach |url={{google books |plainurl=y |id=fDIbuwtYPlAC}}|date=28 December 2008|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|isbn=978-0-387-78193-8|quote = The term ''environment'' refers not only to air, water, and soil but also to substances and conditions at home and at the workplace, including diet, smoking, alcohol, drugs, exposure to chemicals, sunlight, ionizing radiation, electromagnetic fields, infectious agents, etc. Lifestyle, economic and behavioral factors are all aspects of our environment. }}</ref> Common environmental factors that contribute to cancer death include tobacco use (25–30%), diet and ] (30–35%), infections (15–20%), ] (both ionizing and non-ionizing, up to 10%), lack of ], and pollution.<ref name=Enviro2008/><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Islami F, Goding Sauer A, Miller KD, Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Jacobs EJ, McCullough ML, Patel AV, Ma J, Soerjomataram I, Flanders WD, Brawley OW, Gapstur SM, Jemal A | title = Proportion and number of cancer cases and deaths attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors in the United States | journal = CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians | volume = 68 | issue = 1 | pages = 31–54 | date = January 2018 | pmid = 29160902 | doi = 10.3322/caac.21440 | doi-access = free }}</ref> Psychological stress does not appear to be a risk factor for the onset of cancer,<ref name=Cohen2019>{{cite journal | vauthors = Cohen S, Murphy ML, Prather AA | title = Ten Surprising Facts About Stressful Life Events and Disease Risk | journal = Annual Review of Psychology | volume = 70 | pages = 577–597 | date = January 2019 | pmid = 29949726 | pmc = 6996482 | doi = 10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102857 | quote = the strongest conclusion derived from decades of research on stressors and cancer is that stressful events may be associated with decreased cancer survival but are probably not associated with disease incidence (Chida et al. 2008). }}</ref><ref name="pmid23393080">{{cite journal | vauthors = Heikkilä K, Nyberg ST, Theorell T, Fransson EI, Alfredsson L, Bjorner JB, Bonenfant S, Borritz M, Bouillon K, Burr H, Dragano N, Geuskens GA, Goldberg M, Hamer M, Hooftman WE, Houtman IL, Joensuu M, Knutsson A, Koskenvuo M, Koskinen A, Kouvonen A, Madsen IE, Magnusson Hanson LL, Marmot MG, Nielsen ML, Nordin M, Oksanen T, Pentti J, Salo P, Rugulies R, Steptoe A, Suominen S, Vahtera J, Virtanen M, Väänänen A, Westerholm P, Westerlund H, Zins M, Ferrie JE, Singh-Manoux A, Batty GD, Kivimäki M | title = Work stress and risk of cancer: meta-analysis of 5700 incident cancer events in 116,000 European men and women | journal = BMJ | volume = 346 | pages = f165 | date = February 2013 | pmid = 23393080 | pmc = 3567204 | doi = 10.1136/bmj.f165 }}</ref> though it may worsen outcomes in those who already have cancer.<ref name=Cohen2019/> | |||

| === Chemical carcinogens === | |||

| Environmental or lifestyle factors that caused cancer to develop in an individual can be identified by analyzing mutational signatures from genomic sequencing of tumor DNA. For example, this can reveal if lung cancer was caused by tobacco smoke, if skin cancer was caused by UV radiation, or if ] were caused by previous chemotherapy treatment.<ref name=cds>{{cite journal | vauthors = Steele CD, Pillay N, Alexandrov LB | title = An overview of mutational and copy number signatures in human cancer | journal = The Journal of Pathology | volume = 257 | issue = 4 | pages = 454–465 | date = July 2022 | pmid = 35420163 | pmc = 9324981 | doi = 10.1002/path.5912 }}</ref> | |||

| Cancer pathogenesis is traceable back to ] that impact cell growth and metastasis. Substances that cause ] are known as mutagens, and mutagens that cause cancers are known as carcinogens. Particular substances have been linked to specific types of cancer. ] is associated with ] and ]. Prolonged exposure to ] fibers is associated with ]. | |||

| Cancer is generally not a ].<ref name=Tolar>{{cite journal |vauthors=Tolar J, Neglia JP |s2cid=34197973 |title=Transplacental and other routes of cancer transmission between individuals |journal=Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology |volume=25 |issue=6 |pages=430–4 |date=June 2003 |pmid=12794519 |doi=10.1097/00043426-200306000-00002}}</ref> Exceptions include rare transmissions that occur with pregnancies and occasional ]. However, transmissible infectious diseases such as ], ], ] and ], can contribute to the development of cancer.{{citation needed|date=March 2024}} | |||

| Many ]s are also ]s, but some carcinogens are not mutagens. ] is an example of a chemical carcinogen that is not a mutagen. Such chemicals are thought to promote cancers through their stimulating effect on the rate of cell ]. Faster rates of mitosis leaves less time for repair enzymes to repair damaged DNA during ], increasing the likelihood of a genetic mistake. A mistake made during mitosis can lead to the daughter cells receiving the wrong number of ] (''see ] above''). | |||

| === Chemicals === | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Further|Alcohol and cancer|Smoking and cancer}} | |||

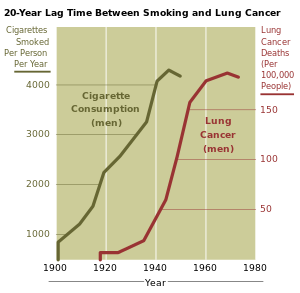

| Decades of research have demonstrated the strong association between ] use and cancers of many sites, making it perhaps the most important human carcinogen. Hundreds of epidemiological studies have confirmed this association. Further support comes from the fact that ] death rates in the United States have mirrored ] patterns, with increases in smoking followed by dramatic increases in lung cancer death rates and, more recently, decreases in smoking followed by decreases in lung cancer death rates in men. | |||

| ] | |||

| Exposure to particular substances have been linked to specific types of cancer. These substances are called '']s''. | |||

| === Ionizing radiation === | |||

| Sources of ], such as ] gas, can cause cancer. Prolonged exposure to ] from the ] can lead to ] and other skin malignancies. | |||

| ], for example, causes 90% of lung cancer.<ref name="pmid9594919">{{cite journal |vauthors=Biesalski HK, Bueno de Mesquita B, Chesson A, Chytil F, Grimble R, Hermus RJ, Köhrle J, Lotan R, Norpoth K, Pastorino U, Thurnham D |title=European Consensus Statement on Lung Cancer: risk factors and prevention. Lung Cancer Panel |journal=CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians |volume=48 |issue=3 |pages=167–76; discussion 164–66 |year=1998 |pmid=9594919 |doi=10.3322/canjclin.48.3.167|s2cid=20891885 |doi-access=free }}</ref> Tobacco use can cause cancer throughout the body including in the mouth and throat, ], ], stomach, bladder, kidney, cervix, colon/rectum, liver and ].<ref name="pmid12270001">{{cite journal |vauthors=Kuper H, Boffetta P, Adami HO |s2cid=6132726 |title=Tobacco use and cancer causation: association by tumour type |journal=Journal of Internal Medicine |volume=252 |issue=3 |pages=206–24 |date=September 2002 |pmid=12270001 |doi=10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.01022.x|doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=27 August 2019 |title=Cancer and Tobacco Use |url=https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/cancerandtobacco/index.html |access-date=25 October 2023 |website=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |language=en-us}}</ref> Tobacco smoke contains over fifty known carcinogens, including ]s and ]s.<ref name=Kuper/> | |||

| Radiation from ]s has been conjectured for some time as a cause but this theory has not gained mainstream support. Nevertheless some experts caution against prolonged exposure.<ref>'''', , 23 July 2008</ref> | |||

| Tobacco is responsible for about one in five cancer deaths worldwide<ref name="Kuper">{{cite journal |vauthors=Kuper H, Adami HO, Boffetta P |s2cid=9172672 |title=Tobacco use, cancer causation and public health impact |journal=Journal of Internal Medicine |volume=251 |issue=6 |pages=455–66 |date=June 2002 |pmid=12028500 |doi=10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.00993.x|doi-access=free }}</ref> and about one in three in the developed world.<ref name="Sasco">{{cite journal |vauthors=Sasco AJ, Secretan MB, Straif K |title=Tobacco smoking and cancer: a brief review of recent epidemiological evidence |journal=Lung Cancer |volume=45 | issue = Suppl 2 |pages=S3–9 |date=August 2004 |pmid=15552776 |doi=10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.07.998}}</ref> Lung cancer death rates in the United States have mirrored ] patterns, with increases in smoking followed by dramatic increases in lung cancer death rates and, more recently, decreases in smoking rates since the 1950s followed by decreases in lung cancer death rates in men since 1990.<ref name="pmid16998161">{{cite journal |vauthors=Thun MJ, Jemal A |title=How much of the decrease in cancer death rates in the United States is attributable to reductions in tobacco smoking? |journal=Tobacco Control |volume=15 |issue=5 |pages=345–47 |date=October 2006 |pmid=16998161 |pmc=2563648 |doi=10.1136/tc.2006.017749}}</ref><ref name="pmid18434333">{{cite journal |vauthors=Dubey S, Powell CA |title=Update in lung cancer 2007 |journal=American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine |volume=177 |issue=9 |pages=941–46 |date=May 2008 |pmid=18434333 |pmc=2720127 |doi=10.1164/rccm.200801-107UP}}</ref> | |||

| === Infectious diseases === | |||

| In Western Europe, 10% of cancers in males and 3% of cancers in females are attributed to alcohol exposure, especially liver and digestive tract cancers.<ref name="pmid21474525">{{cite journal |vauthors=Schütze M, Boeing H, Pischon T, Rehm J, Kehoe T, Gmel G, Olsen A, Tjønneland AM, Dahm CC, Overvad K, Clavel-Chapelon F, Boutron-Ruault MC, Trichopoulou A, Benetou V, Zylis D, Kaaks R, Rohrmann S, Palli D, Berrino F, Tumino R, Vineis P, Rodríguez L, Agudo A, Sánchez MJ, Dorronsoro M, Chirlaque MD, Barricarte A, Peeters PH, van Gils CH, Khaw KT, Wareham N, Allen NE, Key TJ, Boffetta P, Slimani N, Jenab M, Romaguera D, Wark PA, Riboli E, Bergmann MM |title=Alcohol attributable burden of incidence of cancer in eight European countries based on results from prospective cohort study |journal=BMJ |volume=342 |pages=d1584 |date=April 2011 |pmid=21474525 |pmc=3072472 |doi=10.1136/bmj.d1584}}</ref> Cancer from work-related substance exposures may cause between 2 and 20% of cases,<ref name="pmid18055160">{{cite journal |vauthors=Irigaray P, Newby JA, Clapp R, Hardell L, Howard V, Montagnier L, Epstein S, Belpomme D |title=Lifestyle-related factors and environmental agents causing cancer: an overview |journal=Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy |volume=61 |issue=10 |pages=640–58 |date=December 2007 |pmid=18055160 |doi=10.1016/j.biopha.2007.10.006}}</ref> causing at least 200,000 deaths.<ref name="WHO_occup">{{cite press release |title=WHO calls for prevention of cancer through healthy workplaces |publisher=World Health Organization |date=27 April 2007 |url=https://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/notes/2007/np19/en/index.html |access-date=13 October 2007 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071012202014/http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/notes/2007/np19/en/index.html |archive-date=12 October 2007}}</ref> Cancers such as lung cancer and ] can come from inhaling tobacco smoke or ] fibers, or ] from exposure to ].<ref name=WHO_occup/> | |||

| Some cancers can be caused by ] with ]s.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Pagano JS, Blaser M, Buendia MA, ''et al'' |title=Infectious agents and cancer: criteria for a causal relation |journal=Semin. Cancer Biol. |volume=14 |issue=6 |pages=453–71 |year=2004 |month=December |pmid=15489139 |doi=10.1016/j.semcancer.2004.06.009}}</ref> Many cancers originate from a ] infection; this is especially true in animals such as ]s, but also in ]s, as viruses are responsible for 15% of human cancers worldwide. The main viruses associated with human cancers are ], ] and ] virus, ], and ]. Experimental and epidemiological data imply a causative role for viruses and they appear to be the second most important risk factor for cancer development in humans, exceeded only by tobacco usage.<ref name="zur Hausen-viruses">{{cite journal | author = zur Hausen H | title = Viruses in human cancers | journal = Science | volume = 254 | issue = 5035 | pages = 1167| year = 1991 | pmid = 1659743| doi = 10.1126/science.1659743 }}</ref> The mode of virally-induced tumors can be divided into two, ''acutely-transforming'' or ''slowly-transforming''. In acutely transforming viruses, the virus carries an overactive oncogene called viral-oncogene (v-onc), and the infected cell is transformed as soon as v-onc is expressed. In contrast, in slowly-transforming viruses, the virus genome is inserts near a proto-oncogene in the host genome. The viral ] or other transcription regulation elements then cause overexpression of that proto-oncogene. This induces uncontrolled cell division. Because the site of insertion is not specific to proto-oncogenes and the chance of insertion near any proto-oncogene is low, slowly-transforming viruses will cause tumors much longer after infection than the acutely-transforming viruses. | |||

| Exposure to ] (PFOA), which is predominantly used in the production of ], is known to cause two kinds of cancer.<ref>{{cite web |url= https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/erin-brockovich-blasts-u-s-regulation-of-toxic-chemicals/ |title= Erin Brockovich Blasts U.S. Regulation of Toxic Chemicals |website= scientificamerican.com | publisher= Scientific American |date= 28 December 2020}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=Environmental Pollutant, PFOA, Associated with Increased Risk of Kidney Cancer |url=https://dceg.cancer.gov/news-events/news/2020/pfoa-kidney |work=] |date=24 September 2020}}</ref> | |||

| Hepatitis viruses, including ] and ], can induce a chronic viral infection that leads to ] in 0.47% of ] patients per year (especially in Asia, less so in North America), and in 1.4% of ] carriers per year. Liver cirrhosis, whether from chronic viral hepatitis infection or alcoholism, is associated with the development of ], and the combination of cirrhosis and viral hepatitis presents the highest risk of ] development. Worldwide, ] is one of the most common, and most deadly, cancers due to a huge burden of ] transmission and disease. | |||

| Chemotherapy drugs such as ] compounds are ] that increase the risk of ]<ref name=cds/> | |||

| Advances in cancer research have made a vaccine designed to prevent cancer available. In 2006, the US ] approved a ] vaccine, called ]. The vaccine protects against four HPV types, which together cause 70% of cervical cancers and 90% of genital warts. In March 2007, the US ] ] (ACIP) officially recommended that females aged 11-12 receive the vaccine, and indicated that females as young as age 9 and as old as age 26 are also candidates for immunization. | |||

| ], an ], is a ] that can cause ] to develop.<ref name=cds/> | |||

| In addition to viruses, researchers have noted a connection between ]. The most prominent example is the link between chronic infection of the wall of the stomach with '']'' and ].<ref>{{cite journal |author=Peter S, Beglinger C |title=Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: the causal relationship |journal=Digestion |volume=75 |issue=1 |pages=25–35 |year=2007 |pmid=17429205 |doi=10.1159/000101564}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Wang C, Yuan Y, Hunt RH |title=The association between Helicobacter pylori infection and early gastric cancer: a meta-analysis |journal=Am. J. Gastroenterol. |volume=102 |issue=8 |pages=1789–98 |year=2007 |month=August |pmid=17521398 |doi=10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01335.x}}</ref> Although only a minority of those infected with ''Helicobacter'' go on to develop cancer, since this pathogen is quite common it is probably responsible for the majority of these cancers.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Cheung TK, Xia HH, Wong BC |title=Helicobacter pylori eradication for gastric cancer prevention |journal=J. Gastroenterol. |volume=42 Suppl 17 |issue= |pages=10–5 |year=2007 |month=January |pmid=17238019 |doi=10.1007/s00535-006-1939-2}}</ref> | |||

| === |

=== Diet and exercise === | ||

| {{Main|Diet and cancer}} | |||

| Some hormones can act in a similar manner to non-mutagenic carcinogens in that they may stimulate excessive cell growth. A well-established example is the role of ] states in promoting ]. | |||

| {{anchor|Diet}}Diet, ], and ] are related to up to 30–35% of cancer deaths.<ref name=Enviro2008/><ref name="Nutri06">{{cite journal |vauthors=Kushi LH, Byers T, Doyle C, Bandera EV, McCullough M, McTiernan A, Gansler T, Andrews KS, Thun MJ |s2cid=19823935 |title=American Cancer Society Guidelines on Nutrition and Physical Activity for cancer prevention: reducing the risk of cancer with healthy food choices and physical activity |journal=CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians |volume=56 |issue=5 |pages=254–81; quiz 313–14 |year=2006 |pmid=17005596 |doi=10.3322/canjclin.56.5.254|doi-access=free /></ref> In the United States, excess body weight is associated with the development of many types of cancer and is a factor in 14–20% of cancer deaths.<ref name="Nutri06"/> A UK study including data on over 5 million people showed higher ] to be related to at least 10 types of cancer and responsible for around 12,000 cases each year in that country.<ref name="BhaskaranLancet">{{cite journal |vauthors=Bhaskaran K, Douglas I, Forbes H, dos-Santos-Silva I, Leon DA, Smeeth L |title=Body-mass index and risk of 22 specific cancers: a population-based cohort study of 5·24 million UK adults |journal=Lancet |volume=384 |issue=9945 |pages=755–65 |date=August 2014 |pmid=25129328 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60892-8 |pmc=4151483/></ref> Physical inactivity is believed to contribute to cancer risk, not only through its effect on body weight but also through negative effects on the ] and ].<ref name="Nutri06"/> More than half of the effect from the diet is due to ] (eating too much), rather than from eating too few vegetables or other healthful foods.{{citation needed|date=March 2024}} | |||

| === Immune system dysfunction === | |||

| Some specific foods are linked to specific cancers. A high-salt diet is linked to ].<ref name=pmid18990005/> ], a frequent food contaminant, causes liver cancer.<ref name=pmid18990005/> ] chewing can cause oral cancer.<ref name="pmid18990005">{{cite journal |vauthors=Park S, Bae J, Nam BH, Yoo KY |title=Aetiology of cancer in Asia |journal=Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention |volume=9 |issue=3 |pages=371–80 |year=2008 |pmid=18990005 |url=http://www.apocpcontrol.org/page/popup_paper_file_view.php?pno=MzcxIFBhcmsucCZrY29kZT04MjI=&pgubun=i|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110904052252/http://www.apocpcontrol.org/page/popup_paper_file_view.php?pno=MzcxIFBhcmsucCZrY29kZT04MjI=&pgubun=i |archive-date=4 September 2011}}</ref> National differences in dietary practices may partly explain differences in cancer incidence. For example, ] is more common in Japan due to its high-salt diet<ref name="pmid19107449">{{Cite book |vauthors=Brenner H, Rothenbacher D, Arndt V |chapter=Epidemiology of Stomach Cancer |title=Cancer Epidemiology |volume=472 |chapter-url={{google books |plainurl=y |id=5v1JAQAAIAAJ |page=467}}|pages = 467–77 | year = 2009 | pmid = 19107449 | doi = 10.1007/978-1-60327-492-0_23 | isbn = 978-1-60327-491-3 | series = Methods in Molecular Biology |issue=5450 |pmc=2166976 }}</ref> while ] is more common in the United States. Immigrant cancer profiles mirror those of their new country, often within one generation.<ref name="pmid14278899">{{cite journal |vauthors=Buell P, Dunn JE |title=Cancer Mortality Among Japanese Issei and Nisei of California |journal=Cancer |volume=18 |issue=5 |pages=656–64 |date=May 1965 |pmid=14278899 |doi=10.1002/1097-0142(196505)18:5<656::AID-CNCR2820180515>3.0.CO;2-3|doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||