| Revision as of 12:46, 22 September 2008 view source81.86.104.61 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 19:28, 14 December 2024 view source Vbbanaz05 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users10,926 edits Fixing the infobox | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Distinguish|text = the ], the ending phase of the battle which occurred inside the city}} | |||

| :''For the ] on Berlin by the ] from November 1943 to March 1944, see ].'' | |||

| {{for|the Royal Air Force bombing campaign|Battle of Berlin (RAF campaign)}} | |||

| {{FixBunching|beg}} | |||

| {{Infobox Military Conflict | |||

| |conflict = Battle of Berlin | |||

| |image = ] | |||

| |caption = Soviet soldiers raising the Soviet flag over the ] after its capture. | |||

| |partof=the ] of ] | |||

| |place = ], ] | |||

| |date = ] – ] ] | |||

| |result = Decisive Soviet victory | |||

| |combatant2 = {{flag|Nazi Germany|name=Germany}} | |||

| |combatant1 = {{flag|Soviet Union|1923}} | |||

| {{flagicon|Poland}} ] | |||

| |commander1 = ] – | |||

| {{flagicon|Soviet Union|1923}} ]<br><br>] – | |||

| {{flagicon|Soviet Union|1923}} ]<br><br>] – <br> | |||

| {{flagicon|Soviet Union|1923}} ] | |||

| |strength2=Total strength<br>766,750 soldiers,<br>1,519 ],<ref>Wagner, p. 346</ref><br>2,224 aircraft<ref>Bergstrom, p. 117.</ref><br>9,303 artillery pieces<ref name="Glantz">Glantz, p. 373</ref><ref group=nb>Initial Soviet planning estimates had placed the total strength at 1 million men, but this was an overestimate (Glantz, p. 258)</ref><br>In the Berlin Defence Area approximately 45,000 soldiers, supplemented by the police force, ], and 40,000 '']''.<ref name="Beevor-287">Beevor, p. 287</ref><ref group=nb>A large number of the 45,000 were troops of the ] that were at the start of the battle part of the German IX Army on the ]</ref> | |||

| |commander2 = ] – | |||

| {{flagicon|Germany|Nazi}} ] | |||

| then | |||

| {{flagicon|Germany|Nazi}} ]<ref group=nb>Heinrici was replaced by General ] on ]. General Kurt von Tippelskirch was named as Heinrici's interim replacement until Student could arrive and assume control. Student was captured by the British and never arrived.</ref><br><br>] – | |||

| {{pp|small=yes}} | |||

| {{flagicon|Germany|Nazi}} ]<br><br>Berlin Defence Area – | |||

| {{Short description|Last major offensive of the European theatre of World War II}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=February 2023}} | |||

| {{Use British English|date=May 2017}} | |||

| {{Infobox military conflict | |||

| | conflict = Battle of Berlin | |||

| | image = Raising a flag over the Reichstag - Restoration.jpg | |||

| | image_size = 300 | |||

| | caption = '']'', May 1945 | |||

| | partof = the ] of ] | |||

| | place = ], ] | |||

| | coordinates = {{coord|52|31|07|N|13|22|34|E|region:DE-BE_type:event|display=inline,title}} | |||

| | date = 16 April – 2 May 1945<br />({{Age in years, months, weeks and days|month1=04|day1=16|year1=1945|month2=05|day2=02|year2=1945}}) | |||

| | result = Allied victory | |||

| | territory = Soviet Union ] ] | |||

| | combatant1 = {{unbulleted list | |||

| | '''{{flag|Soviet Union|1936}}''' | |||

| | {{flagdeco|Poland|1928}} ]}} | |||

| | combatant2 = '''{{flagcountry|Nazi Germany|1935}}''' | |||

| | commander1 = {{Flagicon|Soviet Union|1936}} ]<br>{{Flagicon|Soviet Union|1936}} ]<br>{{Flagicon|Soviet Union|1936}} ]<br>{{Flagicon|Soviet Union|1936}} {{ill|Nver Safarian|hy|Նվեր Սաֆարյան}}<br/>{{flagdeco|Poland|1928}} ] | |||

| | commander2 = {{Flagicon|Nazi Germany}} ''']'''{{KIA|Suicide of Adolf Hitler}}{{efn|name=HitlerGoebbels}} <br> {{Flagicon|Nazi Germany}} ]<br> {{Flagicon|Nazi Germany}} ]<br> {{Flagicon|Nazi Germany}} ]<br> {{Flagicon|Nazi Germany}} ] {{KIA|Suicide}}<br>{{Flagicon|Nazi Germany}} ] {{efn|name=StudentTippelskirch}}<br>{{Flagicon|Nazi Germany}} ]<br>{{Flagicon|Nazi Germany}} ]{{Surrender}}<br>{{Flagicon|Nazi Germany}} ]{{Surrendered}}{{efn|name=Weidling}} | |||

| | units1 = {{plainlist | | |||

| *{{Flagicon|Soviet Union|1936}} ] | |||

| *{{Flagicon|Soviet Union|1936}} ] | |||

| *{{Flagicon|Soviet Union|1936}} ] | |||

| *{{Flagicon|Poland|1928}} ] | |||

| *{{Flagicon|Poland|1928}} ]}} | |||

| | units2 = {{plainlist | | |||

| *] ] | |||

| *] ] | |||

| *{{Flagicon|Nazi Germany}} Berlin Defence Area}} | |||

| | strength1 = {{plainlist | | |||

| *Total strength: | |||

| **2,300,000 soldiers (155,900–200,000<br />{{nowrap|]}}){{sfn|Zaloga|1982|p=27}}{{sfn|Glantz|1998|p=261}} | |||

| *6,250 tanks and SP guns{{sfn|Glantz|1998|p=261}} | |||

| *7,500 aircraft{{sfn|Glantz|1998|p=261}} | |||

| *41,600 artillery pieces.{{sfn|Ziemke|1969|p=71}}{{sfn|Murray|Millett|2000|p=482}} | |||

| *For the ] and assault on the Berlin Defence Area: about 1,500,000 soldiers{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=287}} | |||

| }} | |||

| | strength2 = {{plainlist | | |||

| *Total strength: | |||

| *36 divisions{{sfn|Antill|2005|p=28}} | |||

| *766,750 soldiers{{sfn|Glantz|1998|p=373}} | |||

| *1,519 ]{{sfn|Wagner|1974|p=346}} | |||

| *2,224 aircraft{{sfn|Bergstrom|2007|p=117}} | |||

| *9,303 artillery pieces{{sfn|Glantz|1998|p=373}}{{efn|name=SovietEsts}} | |||

| *In the Berlin Defence Area: about 45,000 soldiers, supplemented by: | |||

| *] ] | |||

| *] ] | |||

| *] 40,000 '']''{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=287}}{{efn|name=GermanTroops}} | |||

| }} | |||

| | casualties1 = '''Total: 361,367''' | |||

| {{plainlist | | |||

| *Archival research <br /> (operational total) | |||

| *81,116 dead or missing{{sfn|Krivosheev|1997|p=157}} | |||

| *280,251 sick or wounded}} | |||

| {{plainlist | | |||

| *'''Material losses:''' | |||

| *1,997 tanks and SPGs destroyed{{sfn|Krivosheev|1997|p=263}} | |||

| *2,108 artillery pieces | |||

| *917 aircraft{{sfn|Krivosheev|1997|p=263}} | |||

| }} | |||

| | casualties2 = '''Total: 917,000–925,000''' | |||

| {{plainlist | | |||

| *92,000–100,000 killed | |||

| *220,000 wounded{{sfn|Müller|2008|p=673}}{{efn|name=GermanCasualties}} | |||

| *480,000 captured{{sfn|Glantz|2001|p=95}} | |||

| *125,000 civilians dead{{sfn|Antill|2005|p=85}} | |||

| }} | |||

| | campaignbox = {{Campaignbox Axis-Soviet War}} | |||

| {{Campaignbox Battle of Berlin}} | |||

| {{History of Berlin}} | |||

| }} | |||

| The '''Battle of Berlin''', designated as the '''Berlin Strategic Offensive Operation''' by the ], and also known as the '''Fall of Berlin''', was one of the last major ]s of the ].{{efn|name=LastOffensive}} | |||

| {{flagicon|Germany|Nazi}} ] | |||

| then | |||

| After the ] of January–February 1945, the ] had temporarily halted on a line {{cvt|60|km|mi}} east of ]. On 9 March, Germany established its defence plan for the city with ]. The first defensive preparations at the outskirts of Berlin were made on 20 March, under the newly appointed commander of ], General ]. | |||

| {{flagicon|Germany|Nazi}} ]{{POW}}<ref group=nb>Weidling replaced Oberstleutnant ] as commander of Berlin who only held the post for one day having taken command from Reymann.</ref> | |||

| |strength1 = Total strength<br>2,500,000 soldiers,<br>6,250 tanks,<br>7,500 aircraft,<br>41,600 artillery pieces.<ref>Ziemke, p. 71</ref><ref>Murray, p. 482</ref><br>For the ] and assault on the Berlin Defence Area about 1,500,000 soldiers.<ref name="Beevor-287"/> | |||

| |casualties2 = Initial Soviet estimate<br>458,080 killed,<br>479,298 captured<ref>Glantz, p. 271</ref><br>Berlin Defence Area:<br>22,000 civilian dead,<br>about 22,000 military dead<ref>Antill, p. 85</ref> | |||

| |casualties1 =Archival research <br> 81,116 dead or missing<ref name=Khrivosheev-219-220>Khrivosheev, pp. 219,220.</ref> (including 2,825 Polish<ref name=Khrivosheev-219-220 />)<br>280,251 sick or wounded<br> Total casualties 361,367 men<br>1,997 tanks,<br>2,108 artillery pieces,<br>917 aircraft<ref name=Khrivosheev-219-220 />}} | |||

| {{FixBunching|mid}} | |||

| {{Campaignbox Axis-Soviet War}} | |||

| {{FixBunching|mid}} | |||

| {{Campaignbox Battle of Berlin}} | |||

| {{FixBunching|end}} | |||

| When the ] offensive resumed on 16 April, two Soviet ]s (]s) attacked Berlin from the east and south, while a third overran German forces positioned north of Berlin. Before the main battle in Berlin commenced, the Red Army encircled the city after successful battles of the ] and ]. On 20 April 1945, ] birthday, the ] led by ] ], advancing from the east and north, started shelling Berlin's city centre, while Marshal ]'s ] broke through ] and advanced towards the southern suburbs of Berlin. On 23 April General ] assumed command of the forces within Berlin. The ] consisted of several depleted and disorganised ] and ] divisions, along with poorly trained '']'' and ] members. Over the course of the next week, the Red Army gradually took the entire city. | |||

| The '''Battle of Berlin''' was one of the final battles<ref group=nb>The last major battle was the ] on ]–] ], when the Soviet Army with the help of Polish, ]n, and ] forces defeated the parts of ] which continued to resist in Czechoslovakia. The operation involved about 3,000,000 personnel from both sides. The last actual battle in Europe was the ] (] – ], ]). See ] for details on these final days of the war.</ref> of the ]. In what was known to the Soviets as the "'''Berlin Strategic Offensive Operation'''", two ] ]s (]s) attacked ] from the east and south, while a third overran German forces positioned north of Berlin. | |||

| On 30 April, ]. The city's garrison surrendered on 2 May but fighting continued to the north-west, west, and south-west of the city until the ] on 8 May (9 May in the Soviet Union) as some German units fought westward so that they could surrender to the ] rather than to the Soviets.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|pp=400–405}} | |||

| ==Background== | ==Background== | ||

| ] | |||

| Starting on ], ], the ] began the ] across the ] River and from Warsaw — a three-day operation on a broad front which incorporated four army ]s.<ref>Duffy, pp. 24,25</ref> On the fourth day, the Red Army broke out and started moving west, up to thirty to forty kilometres per day, taking the ], ], ], and ], drawing up on a line sixty kilometres east of ], along the ] River.<ref name="Hastings">Hastings, p. 295</ref> | |||

| On 12 January 1945, the Red Army began the ] across the ] River; and, from Warsaw, a three-day operation on a broad front, which incorporated four army ]s.{{sfn|Duffy|1991|pp=24, 25}} On the fourth day, the Red Army broke out and started moving west, up to {{cvt|30|to|40|km|mi}} per day, taking ], ], and ], drawing up on a line {{cvt|60|km|mi}} east of Berlin along the ] River.{{sfn|Hastings|2004|p=295}} | |||

| The newly created ], under the command of '']'' ],<ref>Beevor, p. 52</ref> attempted a counter-attack but failed by ].<ref>Duffy, pp. 176–188</ref> The Red Army then drove on to ], clearing the right bank of the Oder River, thereby reaching into ].<ref name="Hastings" /> | |||

| The newly created ], under the command of {{lang|de|]}} ],{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=52}} ], but this had failed by 24 February.{{sfn|Duffy|1991|pp=176–188}} The Red Army then drove on to ], clearing the right bank of the Oder River, thereby reaching into ].{{sfn|Hastings|2004|p=295}} | |||

| In the south the ] raged. ]], the Germans' ] had failed and within twenty-four hours, the Red Army's counter-attack took back everything the Germans had gained in ten days.<ref>Dollinger, p. 198</ref> On ], the Soviets entered ] and, during the ], they finally captured ] on ].<ref>Beevor, p. 196</ref> | |||

| In the south, Soviet and Romanian forces ]. Three German divisions' attempts to relieve the encircled Hungarian capital city failed, and Budapest fell to the Soviets on 13 February.{{sfn|Duffy|1991|p=293}} ] insisted on a counter-attack to recapture the Drau-Danube triangle.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=8}} The goal was to secure the oil region of ] and regain the ] River for future operations, {{sfn|Tiemann|1998|p=200}} but the depleted German forces had been given an impossible task.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=9}} By 16 March, the German ] had failed, and a counter-attack by the Red Army took back in 24 hours everything the Germans had taken ten days to gain.{{sfn|Dollinger|1967|p=198}} On 30 March, the Soviets entered Austria; and in the ] they captured ] on 13 April.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=196}} | |||

| By this time, it was clear that the final defeat of the ] was only a few weeks away. Between June and September 1944 the ] had lost more than a million men, lacking fuel and armament needed in order to operate effectively.<ref>Williams, p. 213</ref> Adolf Hitler decided to remain in the city, against the wishes of his advisers. On ], Hitler heard the news that the American President ] had died.<ref>Bullock, p. 753</ref> This briefly raised false hopes in the ] that there might yet be a falling out among the Allies, and that Berlin would be saved at the last moment as had happened once before when Berlin was threatened (see ]).<ref>Bullock, pp. 778–781</ref> | |||

| On 12 April 1945, Hitler, who had earlier decided to remain in the city against the wishes of his advisers, heard the news that the American President ] had died.{{sfn|Bullock|1962|p=753}} This briefly raised false hopes in the '']'' that there might yet be a falling out among the Allies and that Berlin would be saved at the last moment, as had happened once before when Berlin was threatened (see the ]).{{sfn|Bullock|1962|pp=778–781}} | |||

| The ] had tentative plans to drop ] to occupy Berlin in case of a sudden German collapse. Those plans had been drawn up in memory of the sudden unexpected collapse at the end of ], so that important prisoners and documents could be captured rather than lost. No plans were made to seize the city by a ground operation.<ref>Beevor, p. 194</ref> U.S. General ] lost his interest in the ] and saw no further need to suffer casualties in attacking a city that would be in the Soviet ] after the war.<ref>Williams, pp. 310,311</ref> General Eisenhower also worried about western troops colliding with Soviet troops resulting in many casualties from ], since the Red Army, were much closer to Berlin than the Western armies<ref>Ryan, p. 135</ref> The major Western Allied contribution to the battle was the strategic ] during 1945. During 1945 ] launched a number of very large daytime raids on Berlin and for 36 nights in succession scores of ] ]s bombed the German capital, ending on the night of 20/21 April 1945 just before the Soviets entered the city.<ref name=raaf>, ]. Retrieved on ] ].</ref> | |||

| No plans were made by the ] to seize the city by a ground operation.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=194}} The ], General ], lost interest in the ] and saw no further need to suffer casualties by attacking a city that would be in the Soviet ] after the war,{{sfn|Williams|2005|pp=310, 311}} envisioning excessive ] if both armies attempted to occupy the city at once.{{sfn|Ryan|1966|p=135}} The major Western Allied contribution to the battle was the ] during 1945.{{sfn|Milward|1980|p=303}} During 1945 the ] launched very large daytime raids on Berlin and, for 36 nights in succession, scores of ] ]s bombed the German capital, ending on the night of 20/21 April 1945 just before the Soviets entered the city.{{sfn|McInnis|1946|p=115}} | |||

| ==Preparations== | ==Preparations== | ||

| ] | |||

| The Soviet offensive into central Germany — what later became ] — had two objectives. ] did not believe the Western Allies would hand over territory occupied by them in the post-war Soviet zone, so he began the offensive on a broad front and moved rapidly to meet the Western Allies as far west as possible. But the overriding objective was to capture Berlin. The two were complementary because possession of the zone could not be won quickly unless Berlin was taken. Another consideration was that Berlin itself held useful post-war strategic assets, including Adolf Hitler and the ].<ref>Beevor, Preface xxxiv, and pp. 138,325</ref> On ], Hitler appointed ] ] as the commander of the Berlin Defence Area replacing Lieutenant General ].<ref>Beevor, p. 198</ref> | |||

| The Soviet offensive into central Germany, what later became ], had two objectives. ] did not believe the Western Allies would hand over territory occupied by them in the post-war Soviet zone, so he began the offensive on a broad front and moved rapidly to meet the Western Allies as far west as possible. But the overriding objective was to capture Berlin.{{sfn|Beevor|2003|p=219}} The two goals were complementary because possession of the zone could not be won quickly unless Berlin was taken. Another consideration was that Berlin itself held useful post-war strategic assets, including Adolf Hitler and the ]{{sfn|Beevor|2002|loc=Preface xxxiv, and pp. 138, 325}} (but unknown to the Soviet Union, by the time of the Battle of Berlin, the bulk of the uranium and most of the scientists had been evacuated to ] in the ]).{{sfn|Beevor|2012|loc=Ch. 47, loc. 14275 in ebook}} On 6 March, Hitler appointed ] ] commander of the Berlin Defence Area, replacing Lieutenant General ].{{sfn|Beevor|2003|p=166}} | |||

| On 20 March, General ] was appointed Commander-in-Chief of Army Group Vistula replacing Himmler.{{sfn|Beevor|2003|p=140}} Heinrici was one of the best defensive tacticians in the German army, and he immediately started to lay defensive plans. Heinrici correctly assessed that the main Soviet thrust would be made over the Oder River and along the ].{{sfn|Williams|2005|p=292}} He decided not to try to defend the banks of the Oder with anything more than a light ] screen. Instead, Heinrici arranged for ] to fortify the ], which overlooked the Oder River at the point where the Autobahn crossed them.{{sfn|Zuljan|2003}} This was some {{cvt|17|km|mi}} west of the Oder and {{cvt|90|km|mi}} east of Berlin. Heinrici thinned out the line in other areas to increase the manpower available to defend the heights. German engineers turned the Oder's flood plain, already saturated by the spring thaw, into a ] by releasing the water from a ] upstream. Behind the plain on the plateau, the engineers built three belts of defensive emplacements{{sfn|Zuljan|2003}} reaching back towards the outskirts of Berlin (the lines nearer to Berlin were called the ''Wotan'' position).{{sfn|Ziemke|1969|p=76}} These lines consisted of ], ] emplacements, and an extensive network of ] and ].{{sfn|Zuljan|2003}}{{sfn|Ziemke|1969|p=76}} | |||

| On 9 April, after a long resistance, ] in East Prussia fell to the Red Army. This freed up Marshal ]'s ] to move west to the east bank of the Oder river.{{sfn|Williams|2005|p=293}} Marshal ] concentrated his ], which had been deployed along the Oder river from ] in the south to the Baltic, into an area in front of the Seelow Heights.{{sfn|Williams|2005|p=322}} The 2nd Belorussian Front moved into the positions being vacated by the 1st Belorussian Front north of the Seelow Heights. While this redeployment was in progress, gaps were left in the lines; and the remnants of General ]'s ], which had been bottled up in a pocket near ], managed to escape into the ] delta.{{sfn|Beevor|2003|p=426}} To the south, Marshal ] shifted the main weight of the ] out of ] and north-west to the ] River.{{sfn|Ziemke|1969|p=71}} | |||

| The three Soviet fronts had altogether 2.5 million men (including 78,556 soldiers of the ]), 6,250 tanks, 7,500 aircraft, 41,600 ] pieces and ]s, 3,255 truck-mounted ]s (nicknamed 'Stalin's Organ'), and 95,383 motor vehicles, many manufactured in the US.{{sfn|Ziemke|1969|p=71}} | |||

| == Opposing forces == | |||

| {{Further|Order of battle for the Battle of Berlin}} | |||

| ===Northern sector=== | |||

| {{col-begin}} | |||

| {{col-break}} | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| | direction = horizontal | |||

| | align = left | |||

| | width = 120 | |||

| | header = | |||

| | image1 = Bundesarchiv_Bild_146-1976-143-21%2C_Hasso_von_Manteuffel.jpg | |||

| | caption1 = Hasso von Manteuffel | |||

| }} | |||

| {{col-break}} | |||

| {{flagicon|Nazi Germany|1935}} '''German''' | |||

| : ] | |||

| : General of Panzer ''']'''{{efn|Politically rehabilitated after the war and served in the ].}} | |||

| :*4 infantry divisions | |||

| :*3 naval divisions | |||

| :*2 volksgrenadier divisions | |||

| {{col-break}} | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| | direction = horizontal | |||

| | align = left | |||

| | width = 120 | |||

| | header = | |||

| | image1 = Konstanty_Rokossowski%2C_1945.jpg | |||

| | caption1 = Konstantin Rokossovsky | |||

| }} | |||

| {{col-break}} | |||

| {{flagicon|Soviet Union|1936}} '''Soviet''' | |||

| : ''']''' | |||

| : Marshal ''']'''{{efn|Imprisoned and tortured during the ] of 1937; reinstated during the ] of 1939–40; later made a ] for his leadership during ].}} | |||

| :*31 rifle divisions | |||

| :* 7 guards rifle divisions | |||

| :* 1 motorized rifle battalion | |||

| :* 3 tank battalions | |||

| {{col-end}} | |||

| ===Middle sector=== | |||

| {{col-begin}} | |||

| {{col-break}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| {{col-break}} | |||

| {{flagicon|Nazi Germany|1935}} '''German''' | |||

| : ''']''' | |||

| : Colonel General ''']'''{{efn|After release from ] status, contributed to the assemblage of historical accounts of the war.}} | |||

| :*15 infantry divisions | |||

| :* 6 panzer divisions | |||

| :* 2 motorized infantry divisions | |||

| : ] | |||

| : General of Infantry ''']'''{{efn|Politically rehabilitated after the war and served as the ]'s director of civil defense.}} | |||

| :* 5 infantry divisions | |||

| :* 4 panzergrenadier divisions | |||

| :* 1 panzer division | |||

| :* 1 SS grenadier division | |||

| :* 1 security division | |||

| :* 1 Jäger division | |||

| :* 1 parachute division | |||

| :* 1 Kampfgruppe | |||

| {{col-break}} | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| | direction = horizontal | |||

| | align = left | |||

| | width = 120 | |||

| | header = | |||

| | image1 = Zhukov_LIFE.jpg | |||

| | caption1 = Georgy Zhukov | |||

| }} | |||

| {{col-break}} | |||

| {{flagicon|Soviet Union|1936}} '''Soviet''' | |||

| : ''']''' | |||

| : Marshal ''']'''{{efn|One of the USSR's most effective and decorated leaders during ]; his popularity led a jealous ] to sideline him after the war.}} | |||

| :*54 rifle divisions | |||

| :*16 guards rifle divisions | |||

| :* 5 infantry divisions (Polish) | |||

| :* 3 guards cavalry divisions | |||

| :* 3 mechanized brigades | |||

| :* 6 guards mechanized brigades | |||

| :* 7 tank brigades | |||

| :*10 guards tank brigades | |||

| :* 1 armored brigade (Polish) | |||

| :* 2 motorized rifle brigades | |||

| {{col-end}} | |||

| ===Southern sector=== | |||

| {{col-begin}} | |||

| {{col-break}} | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| | direction = horizontal | |||

| | align = left | |||

| | width = 120 | |||

| | header = | |||

| | image1 = Bundesarchiv_Bild_183-L29176,_Ferdinand_Schörner.jpg | |||

| | caption1 = Ferdinand Schörner | |||

| }} | |||

| {{col-break}} | |||

| {{flagicon|Nazi Germany|1935}} '''German''' | |||

| : ''']''' | |||

| : Feldmarshal ''']'''{{efn|Known for unrelenting brutality; ordered the immediate hanging of all deserters, even in the final days of the war; served time for ] in both the ] and the ].}} | |||

| :*13 infantry divisions | |||

| :* 3 panzer divisions | |||

| :* 1 Reichsarbeitsdienst division | |||

| :* 1 SS police division | |||

| :* 1 SS grenadier division | |||

| :* 1 anti-aircraft division | |||

| :* 2 Kampfgruppen | |||

| {{col-break}} | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| | direction = horizontal | |||

| | align = left | |||

| | width = 120 | |||

| | header = | |||

| | image1 = Ivan_Stepanovich_Konev.jpg | |||

| | caption1 = Ivan Konev | |||

| }} | |||

| {{col-break}} | |||

| {{flagicon|Soviet Union|1936}} '''Soviet''' | |||

| *] | |||

| : Marshal ''']'''{{efn|Made ] in February 1944; following war, replaced Zhukov as commander of Soviet ground forces.}} | |||

| :*26 rifle divisions | |||

| :*15 guards rifle divisions | |||

| :* 5 infantry divisions (Polish) | |||

| :* 3 guards cavalry divisions | |||

| :* 1 guards airborne division | |||

| :* 9 guards mechanized brigades | |||

| :* 3 mechanized brigades | |||

| :* 4 guards motorized rifle brigades | |||

| :* 1 armored corps (Polish) | |||

| :* 4 tank brigades | |||

| :*10 guards tank brigades | |||

| :* 1 motorized rifle brigade | |||

| {{col-end}} | |||

| ==Battle of the Oder–Neisse== | |||

| On ], General ] was appointed Commander-in-Chief of ] replacing '']'' ]. Heinrici was one of the best defensive tacticians in the German army. He immediately started to lay defensive plans. Heinrici correctly assessed that the main Soviet thrust would be made over the ] and along the main east-west ].<ref>Williams, p. 292</ref> He decided not to try to defend the banks of the Oder with anything more than a light ] screen. Instead, Heinrici arranged for ] to fortify the ] which overlooked the Oder River at the point where the Autobahn crossed it.<ref name="Ziemke76" /> This was some 17 kilometers west of the Oder and 90 kilometers east of Berlin. Heinrici thinned out the line in other areas to increase the manpower available to defend the heights. German engineers turned the Oder's flood plain, already saturated by the spring thaw, into a ] by releasing the waters in a ] upstream. Behind this the engineers built three belts of defensive emplacements.<ref name="Ziemke76" /> These emplacements reached back towards the outskirts of Berlin (the lines nearer to Berlin were called the '']'' position). These lines consisted of ] ditches, anti-tank gun emplacements, and an extensive network of ] and ].<ref name="Ziemke76">Ziemke, p. 76</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| {{main|Battle of the Oder–Neisse}} | |||

| On ], after a long resistance ] in ] finally fell to the Red Army.<ref name="Williams293">Williams, p. 293</ref> This freed up Marshal ]'s ] to move west to the east bank of the ] river.<ref name="Williams293" /> Marshal ] concentrated his ] which had been deployed along the Oder river from ] in the south to the Baltic, into an area in front of the ].<ref>Williams, p. 322</ref> The 2nd Belorussian Front moved into the positions being vacated by the 1st Belorussian Front north of the Seelow Heights. While this redeployment was in progress, gaps were left in the lines and the remnants of General ] ], which had been bottled up in a pocket near ], managed to escape into the ]. To the south, Marshal ] shifted the main weight of the ] out of ] north-west to the ] River.<ref name=Ziemke71>Ziemke, p. 71</ref> | |||

| The sector in which most of the fighting in the overall offensive took place was the Seelow Heights, the last major defensive line outside Berlin.{{sfn|Ziemke|1969|p=76}} The ], fought over four days from 16 until 19 April, was one of the last ]s of World War II: almost one million Red Army soldiers and more than 20,000 tanks and artillery pieces were deployed to break through the "Gates to Berlin", which were defended by about 100,000 German soldiers and 1,200 tanks and guns.{{sfn|Gregory|Gehlen|2009|pp=207–208}}{{sfn|Beevor|2002|pp=217–233}} The Soviet forces led by Zhukov broke through the defensive positions, having suffered about 30,000 dead,{{sfn|Hastings|2005|p=468}}{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=244}} while 12,000 German personnel were killed.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=244}} | |||

| The three Soviet Fronts had altogether 2.5 million men (including 78,556 soldiers of the ]), 6,250 tanks, 7,500 aircraft, 41,600 ] pieces and ]s, 3,255 truck-mounted ]s (nicknamed 'Stalin's Pipe Organs'), and 95,383 motor vehicles, many manufactured in the USA.<ref name=Ziemke71/> | |||

| On 19 April, the fourth day, the 1st Belorussian Front broke through the final line of the Seelow Heights and nothing but broken German formations lay between them and Berlin.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=247}} The 1st Ukrainian Front, having captured ] the day before, fanned out into open country.{{sfn|Beevor|2003|p=255}} One powerful thrust by ]'s ] and ]'s ] and ]'s ] Tank Armies were heading north-east towards Berlin while other armies headed west towards a section of the United States Army's front line south-west of Berlin on the ].{{sfn|Beevor|2002|pp=312–314}} With these advances, the Soviet forces drove a wedge between Army Group Vistula in the north and ] in the south.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|pp=312–314}} By the end of the day, the German eastern front line north of Frankfurt around Seelow and to the south around Forst had ceased to exist. These breakthroughs allowed the two Soviet Fronts to ] the German ] in a large pocket west of Frankfurt. Attempts by the 9th Army to break out to the west resulted in the ].{{sfn|Beevor|2002|pp=217–233}} The cost to the Soviet forces had been very high, with over 2,807 tanks lost between 1 and 19 April, including at least 727 at the Seelow Heights.{{sfn|Ziemke|1969|p=84}} | |||

| ==Battle of the Oder-Neisse== | |||

| {{main|Battle of the Oder-Neisse}} | |||

| ] | |||

| The sector in which most of the fighting in the overall battle took place was the ], the last major defensive line outside Berlin.<ref name="Ziemke76" /> The ], fought over four days from ] until ], was one of the last ]s of World War II, given that it required a commitment of almost one million Red Army troops and more than 20,000 tanks and artillery pieces were in action to break through the "Gates to Berlin" which was defended by about 100,000 German soldiers and 1,200 tanks and guns.<ref>Beevor, pp. 217–233</ref> However, the Soviet forces led by Zhukov won the battle, having suffered about 30,000 casualties, while the Germans lost only 12,000 personnel.<ref>Beevor, p. 274</ref> | |||

| In the meantime, RAF Mosquitos conducted ] against German positions inside Berlin on the nights of 15 April (105 bombers), 17 April (61 bombers), 18 April (57 bombers), 19 April (79 bombers), and 20 April (78 bombers).{{sfn|RAF staff|2006}} | |||

| During ], the fourth day, the 1st Belorussian Front broke through the final line of the Seelow Heights and nothing but broken German formations lay between them and Berlin. The 1st Ukrainian Front, having captured ] the day before, was fanning out into open country. One powerful thrust by ] ] and ] 3rd and ] 4th guards tank armies were heading north east towards Berlin while other armies headed west towards a section of United States Army front line south west of Berlin on the ].<ref name="Beevor312" /> In doing so, the Soviet forces were driving a wedge between the German ] in the north and ] in the south.<ref name="Beevor312">Beevor, pp. 312–314</ref> By the end of the day, the German eastern front line north of ] around Seelow and to the south around Forst had ceased to exist. These breakthroughs allowed the two Soviet ] to ] the German ] in a large pocket west of Frankfurt. Attempts by the IX Army to break out to the west would result in the ].<ref name="Beevor217-233">Beevor, pp. 217–233</ref> The cost to the Soviet forces had been very high between ] and ], with over 2,807 tanks lost, including at least 727 at the Seelow Heights.<ref name=Ziemke84>Ziemke, p. 84</ref> | |||

| ==Encirclement of Berlin== | ==Encirclement of Berlin== | ||

| On 20 April 1945, Hitler's 56th birthday, Soviet artillery of the 1st Belorussian Front began shelling Berlin and did not stop until the city surrendered. The weight of ordnance delivered by Soviet artillery during the battle was greater than the total tonnage dropped by Western Allied bombers on the city.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|pp=255–256, 262}} While the 1st Belorussian Front advanced towards the east and north-east of the city, the 1st Ukrainian Front pushed through the last formations of the northern wing of Army Group Centre and passed north of ], well over halfway to the American front line on the river Elbe at ].{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=337}} To the north between ] and ], the 2nd Belorussian Front attacked the northern flank of Army Group Vistula, held by ]'s ].{{sfn|Ziemke|1969|p=84}} The next day, ]'s ] advanced nearly {{cvt|50|km|mi}} north of Berlin and then attacked south-west of ]. The Soviet plan was to encircle Berlin first and then envelop the ].{{sfn|Ziemke|1969|p=88}} | |||

| ], ], photo of Adolf Hitler meeting with the Hitler Youth before the battle.<ref group=nb> see : (translation): ''"Hitler decorates child soldiers: This photo belongs to the most well known pieces of modern historiographical photography. Published numerous times, unfortunately it is also very often false dated. Allegedly Hitler is awarding the teenagers the iron cross on his birthday, ] 1945. This seems a typical case of repeated plagiarism: a false date is published in one source - several authors repeat the mistake, which gets a notable dynamic. The true date is the 20 March 1945, unambiguously accounted by the German Newsreel (]) from 22 March 1945, where the scene was published first time."''</ref>]] | |||

| ]'', the German home defence militia, armed with a '']'', outside Berlin]] | |||

| The command of the ], trapped with the IX Army north of Forst, passed from the IV Panzer Army to the IX Army. The corps was still holding on to the Berlin-] highway front line.{{sfn|Simons|1982|p=78}} Field Marshal ]'s Army Group Centre launched a counter-offensive aimed at breaking through to Berlin from the south and entering (the ]) in the 1st Ukrainian Front region, engaging the ] and elements of the Red Army's ] and ].{{sfn|Komorowski|2009|pp=65–67}} When the old southern flank of the IV Panzer Army had some local successes counter-attacking north against the 1st Ukrainian Front, Hitler unrealistically ordered the IX Army to hold Cottbus and set up a front facing west.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=345}} Next, they were to attack the Soviet columns advancing north to form a pincer that would meet the IV Panzer Army coming from the south and envelop the 1st Ukrainian Front before destroying it.{{sfn|Beevor|2003|p=248}} They were to anticipate a southward attack by the III Panzer Army and be ready to be the southern arm of a pincer attack that would envelop 1st Belorussian Front, which would be destroyed by SS-General ]'s ] advancing from north of Berlin.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|pp=310–312}} Later in the day, when Steiner explained that he did not have the divisions to achieve this, Heinrici made it clear to Hitler's staff that unless the IX Army retreated immediately, it would be enveloped by the Soviets. He stressed that it was already too late for it to move north-west to Berlin and would have to retreat west.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|pp=310–312}} Heinrici went on to say that if Hitler did not allow it to move west, he would ask to be relieved of his command.{{sfn|Ziemke|1969|pp=87–88}} | |||

| On ], Hitler's birthday, Soviet artillery of 1st Belorussian Front began to shell the centre of Berlin and did not stop until the city surrendered, (the weight of ordnance delivered by Soviet artillery during the battle was greater than the tonnage dropped by the Western Allied bombers on the city.<ref>Antony Beevor speaking as himself in the documentary )</ref>) While the 1st Belorussian Front advanced towards the east and north-east of the City, the 1st Ukrainian Front had pushed through the last formations of the northern wing of Army Group Centre and had passed north of ] well over halfway to the American front lines on the river ] at ].<ref name=Beevor-337>Beevor, p. 337</ref> To the north between ] and ], 2nd Belorussian Front attacked the northern flank of ], held by ] ].<ref name=Ziemke84/> During the next day, the ] ] advanced nearly 50 km north of Berlin and then attacked south west of ]. Other Soviet units reached the outer defence ring. The Soviet plan was to encircle Berlin first and then envelop the IX Army.<ref name=Ziemke88>Ziemke, p. 88</ref> | |||

| On 22 April 1945, at his afternoon situation conference, Hitler fell into a tearful rage when he realised that his plans, prepared the previous day, could not be achieved. He declared that the war was lost, blaming the generals for the defeat and that he would remain in Berlin until the end and then kill himself.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=275}} | |||

| On ], the ] ] advanced nearly 50 km north of Berlin and then attacked south west of ]. Other Soviet units reached the outer defence ring. The Soviet plan was to encircle Berlin first and then envelop the IX Army.<ref name=Ziemke88>Ziemke ] p. 88</ref> | |||

| In an attempt to coax Hitler out of his rage, General ] speculated that General ]'s ], which was facing the Americans, could move to Berlin because the Americans, already on the Elbe River, were unlikely to move further east. This assumption was based on his viewing of the captured Eclipse documents, which organised the partition of Germany among the Allies.{{sfn|Ryan|1966|p=436}} Hitler immediately grasped the idea, and within hours Wenck was ordered to disengage from the Americans and move the XII Army north-east to support Berlin.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|pp=310–312}} It was then realised that if the IX Army moved west, it could link up with the XII Army. In the evening Heinrici was given permission to make the link-up.{{sfn|Ziemke|1969|p=89}} | |||

| The command of the ] trapped with the IX Army north of ], passed from IV Panzer Army to the IX Army. The corps was still holding onto the Berlin-] highway front line. When the old southern flank of IV Panzer Army had some local successes counter attacking north against 1st Ukrainian Front, Hitler gave orders which showed that his grasp of military reality had gone and ordered IX Army to hold Cottbus and set up a front facing west.<ref>Beevor, p. 345</ref> Then they were to attack into the Soviet columns advancing north. This would allow them to form the northern pincer which would meet with the IV Panzer Army coming from the south and envelop the 1st Ukrainian Front before destroying it. They were to anticipate an attack south by the ] and to be ready to be the southern arm of a pincer attack which would envelop 1st Belorussian Front which would be destroyed by SS-General ]'s ] advancing from north of Berlin.<ref name="Beevor310" /> Later in the day, when Steiner made it plain that he did not have the divisions to do this, Heinrici made it clear to Hitler's staff that unless the IX Army retreated immediately it was about to be enveloped by the Soviets and he stressed it was already too late for it to move north-west to Berlin and would have to retreat west.<ref name="Beevor310">Beevor, p. 310–312</ref> Heinrici went on to say that if Hitler did not allow it to move west he would ask to be relieved of his command.<ref name=Ziemke87>Ziemke, pp. 87,88</ref> | |||

| Elsewhere, the 2nd Belorussian Front had established a bridgehead {{cvt|15|km|mi|0}} deep on the west bank of the Oder and was heavily engaged with the III Panzer Army.{{sfn|Beevor|2003|p=353}} The IX Army had lost Cottbus and was being pressed from the east. A Soviet tank spearhead was on the ] River to the east of Berlin, and another had at one point penetrated the inner defensive ring of Berlin.{{sfn|Ziemke|1969|p=92}} | |||

| On ], at his afternoon situation conference Hitler fell into a tearful rage when he realised that his plans of the day before were not going to be realised. He declared that the war was lost, he blamed the generals and announced that he would stay on in Berlin until the end and then kill himself. In an attempt to coax Hitler out of his rage, General ] speculated that the ], under the command of General ], that was facing the Americans, could move to Berlin because the Americans, already on the ] River, were unlikely to move further east. Hitler immediately grasped the idea and within hours Wenck was ordered to disengage from the Americans and move the XII Army north-east to support Berlin.<ref name="Beevor310" /> It was then realised that, if the IX Army moved west, it could link up with the XII Army. In the evening Heinrici was given permission to make the link up.<ref name=Ziemke89>Ziemke, p. 89</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Away from the map room in the Berlin ] with its imaginary attacks of phantom divisions, the Soviets were getting on with winning the war. 2nd Belorussian Front had established a bridgehead on the east bank of the Oder over 15 km deep and was heavily engaged with the III Panzer Army. The IX Army had lost ] and was being pressed from the east. A Soviet tank spearhead was on the ] river to the east of Berlin and another had at one point penetrated the inner defensive ring of Berlin.<ref name=Ziemke92>Ziemke, p. 92</ref> | |||

| The capital was now within range of field artillery. A Soviet war correspondent, in the style of World War II Soviet journalism, gave the following account of an important event which took place on 22 April 1945 at 08:30 local time:{{sfn|Lewis|1998|p=465}} | |||

| ]'' multiple rocket launchers fire in Berlin, April 1945. This example is a BM-13N, 132 mm rocket launcher mounted on a ] U.S. ] truck.]] | |||

| {{quote|On the walls of the houses we saw ]' appeals, hurriedly scrawled in white paint: 'Every German will defend his capital. We shall stop the Red hordes at the walls of our Berlin.' Just try and stop them!<br /> | |||

| A Soviet war correspondent gave this account, in the zealous style of World War Two Russian journalism, of an important event that day—the capital was now within range of field artillery: | |||

| Steel ]es, barricades, mines, traps, suicide squads with grenades clutched in their hands—all are swept aside before the tidal wave.<br /> | |||

| {{quote|On the walls of the houses we saw Goebbel's appeals, hurriedly scrawled in white paint: 'Every German will defend his capital. We shall stop the Red hordes at the walls of our Berlin.' Just try and stop them!<br /> | |||

| Drizzling rain began to fall. Near ] I saw batteries preparing to open fire.<br /> | |||

| Steel pillboxes, barricades, mines, traps, suicide squads with grenades clutched in their hands—all are swept aside before the tidal wave.<br /> | |||

| Drizzling rain began to fall. Near Bisdorf I saw batteries preparing to open fire.<br /> | |||

| 'What are the targets?' I asked the battery commander.<br /> | 'What are the targets?' I asked the battery commander.<br /> | ||

| Centre of Berlin, Spree bridges, and the northern and Stettin railway stations,' he answered.<br /> | 'Centre of Berlin, ] bridges, and the northern and ] stations,' he answered.<br /> | ||

| Then came the tremendous words of command: 'Open fire |

Then came the tremendous words of command: 'Open fire on the capital of Fascist Germany.'<br /> | ||

| I noted the time. It was exactly 8:30 a.m. on 22 April. Ninety-six shells fell in the centre of Berlin in the course of a few minutes. |

I noted the time. It was exactly 8:30 a.m. on 22 April. Ninety-six shells fell in the centre of Berlin in the course of a few minutes. | ||

| }} | |||

| On |

On 23 April 1945, the Soviet 1st Belorussian Front and 1st Ukrainian Front continued to tighten the encirclement, severing the last link between the German IX Army and the city.{{sfn|Ziemke|1969|p=92}} Elements of the 1st Ukrainian Front continued to move westward and started to engage the German XII Army moving towards Berlin. On this same day, Hitler appointed General ] as the commander of the Berlin Defence Area, replacing Lieutenant General Reymann.<ref>{{harvnb|Beevor|2002|p=286}} states the appointment was on 23 April 1945; {{harvnb|Hamilton|2008|p=160}} states "officially" it was the next morning of 24 April 1945; {{harvnb|Dollinger|1967|p=228}} gives 26 April for Weidling's appointment.</ref> Meanwhile, by 24 April 1945 elements of 1st Belorussian Front and 1st Ukrainian Front had completed the encirclement of the city.{{sfn|Ziemke|1969|pp=92–94}} Within the next day, 25 April 1945, the Soviet ] of Berlin was consolidated, with leading Soviet units probing and penetrating the S-Bahn defensive ring.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=313}} By the end of the day, it was clear that the German defence of the city could not do anything but temporarily delay the capture of the city by the Soviets, since the decisive stages of the battle had already been fought and lost by the Germans outside the city.{{sfn|Ziemke|1969|p=111}} By that time, Schörner's offensive, initially successful, had mostly been thwarted, although he did manage to inflict significant casualties on the opposing Polish and Soviet units, slowing down their progress.{{sfn|Komorowski|2009|pp=65–67}} | ||

| ==Battle in Berlin== | ==Battle in Berlin== | ||

| {{main|Battle in Berlin}} | {{main|Battle in Berlin}} | ||

| ]s'']] | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The forces available to General Weidling for the city's defence included roughly 45,000 soldiers in several severely depleted '']'' and '']'' divisions.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=287}} These divisions were supplemented by the ] force, ] in the compulsory '']'', and the '']''.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=287}} Many of the 40,000 elderly men of the ''Volkssturm'' had been in the army as young men and some were veterans of ]. Hitler appointed '']'' ] the Battle Commander for the central government district that included the ] and ''Führerbunker''.{{sfn|Fischer|2008|pp=42–43}} He had over 2,000 men under his command.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=287}}{{efn|name=SovietPrisoners}} Weidling organised the defences into eight sectors designated 'A' through to 'H' each one commanded by a colonel or a general, but most had no combat experience.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=287}} To the west of the city was the ]. To the north of the city was the ].{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=223}} To the north-east of the city was the ]. To the south-east of the city and to the east of ] was the ].{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=243}} The reserve, ], was in Berlin's central district.{{sfn|Ziemke|1969|p=93}} | |||

| On 23 April, ]'s ] and ]'s ] assaulted Berlin from the south-east and, after overcoming a counter-attack by the German ], reached the ] ring railway on the north side of the ] Canal by the evening of 24 April.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|pp=312–314}} During the same period, of all the German forces ordered to reinforce the inner defences of the city by Hitler, only a small contingent of ] under the command of ''SS Brigadeführer'' ] arrived in Berlin.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|pp=259, 297}} During 25 April, Krukenberg was appointed as the commander of Defence Sector C, the sector under the most pressure from the Soviet assault on the city.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|pp=291–292, 302}} | |||

| The forces available to Weidling for the city's defence included several severely depleted '']'' and '']'' divisions, in all about 45,000 men.<ref name="Beevor-287" /> These divisions were supplemented by the ] force, ] in the compulsory ], and the '']''.<ref name="Beevor-287" /> Many of the 40,000 elderly men of the ''Volkssturm'' had been in the army as young men and some were veterans of ]. The commander of the central district, '']'' ], who had been appointed to this position by Hitler, had over 2,000 men under his command.<ref name="Beevor-287"/><ref group=nb>The Soviets later estimated the number as 180,000, but this was from the number of prisoners that they took, and included many unarmed men in uniform, such as railway officials and members of the Reich Labour Service.(Beevor, p. 287)</ref> Weidling organized the defences into eight sectors designated 'A' through to 'H' each one commanded by a colonel or a general, but most had no combat experience.<ref name="Beevor-287"/> To the west of the city was the ]. To the north of the city was the ].<ref>Beevor, p. 223</ref> To the north-east of the city was the ]. To the south-east of the city and to the east of ] was the ].<ref>Beevor, p. 243</ref> The reserve, ], was in Berlin's central district.<ref>Ziemke, p. 93</ref> | |||

| On 26 April, ]'s ] and the 1st Guards Tank Army fought their way through the southern suburbs and attacked Tempelhof Airport, just inside the S-Bahn defensive ring, where they met stiff resistance from the ''Müncheberg'' Division.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|pp=259, 297}} But by 27 April, the two understrength divisions (''Müncheberg'' and ''Nordland'') that were defending the south-east, now facing five Soviet armies—from east to west, the 5th Shock Army, the 8th Guards Army, the 1st Guards Tank Army and ]'s 3rd Guards Tank Army (part of the 1st Ukrainian Front)—were forced back towards the centre, taking up new defensive positions around Hermannplatz.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|pp=246–247}} Krukenberg informed General ], ] of the ] of ] that within 24 hours the ''Nordland'' would have to fall back to the centre sector Z (for ''Zentrum'').{{sfn|Beevor|2002|pp=303–304}}<ref>{{harvnb|Beevor|2002|p=304}}, states the centre sector was known as Z for Zentrum; {{harvnb|Fischer|2008|pp=42–43}}, and {{harvnb|Tiemann|1998|p=336}}, quoting General Mohnke directly refers to the smaller centre government quarter/district in this area and under his command as Z-Zitadelle.</ref> The Soviet advance to the city centre was along these main axes: from the south-east, along the Frankfurter Allee (ending and stopped at the ]); from the south along ] ending north of the ], from the south ending near the ] and from the north ending near the ].{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=340}} The Reichstag, the Moltke bridge, Alexanderplatz, and the Havel bridges at Spandau saw the heaviest fighting, with house-to-house and ]. The foreign contingents of the SS fought particularly hard, because they were ideologically motivated and they believed that they would not live if captured.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|pp=257–258}} | |||

| Berlin's fate was sealed, given that the decisive stages of the battle were fought outside the city, but the resistance inside continued.<ref name=Ziemke-111/> On ] ] ] and ] ] assaulted Berlin from the south east and after overcoming a counter attack by the German ] had by the evening of the ] reached the ] ring railway on the north side of the ]. During the same period, of all the German forces ordered to reinforce the inner defences of the city by Hitler, only a small contingent of French SS volunteers under the command of ''Brigadeführer'' ] arrived in Berlin.<ref>Beevor, pp. 259, 297</ref> During ], Krukenberg was appointed as the commander of Defence Sector C, the sector under the most pressure from the Soviet assault on the city.<ref name=Beevor-291>Beevor, pp. 291,292, 302</ref> | |||

| On ] German ''General der Artillerie'' ] was appointed commander of the Berlin Defence Area.<ref name="Dollinger-228">Dollinger, p. 228</ref> ] ] and the 1st Guards Tank Army fought their way through the southern suburbs and attacked ], just inside the S-Bahn defensive ring, where they met stiff resistance from the ''Müncheberg'' Division.<ref>Beevor, pp. 259, 297</ref> But by the ] the two understrength ''Müncheberg'' ''Norland'' divisions defending the south east, now facing five Soviet armies — from east to west they were the 5th Shock Army, the 8th Guards Army, the 1st Guards Tank Army and ] 3rd Guards Tank Army (part of the 1st Ukrainian Front), were forced back towards the centre taking up new defensive positions around Hermannplatz.<ref>Beevor, pp. 246,247</ref> Krukenberg soonly informed General ] ] of the ] of (]) that within 24 hours the ''Nordland'' would have to fall back to the centre sector Z (for ''Zentrum'').<ref name=Beevor-259-304>Beevor, pp. 303,304</ref> The Soviet advance to the city centre was along these main axes: from the south east, along the Frankfurter Allee (ending and stopped at the ]); from the south along Sonnen Allee ending north of the Belle Alliance Platz, from the south ending near the Potsdamer Platz and from the north ending near the ].<ref name=Beevor-340>Beevor, p. 340</ref> The Reichstag, the Moltke bridge, Alexanderplatz, and the Havel bridges at Spandau were the places where the fighting was heaviest, with house-to-house and ]. The foreign contingents of the SS fought particularly hard, because they were ideologically motivated and they believed that they would not live if captured.<ref name=Beevor-257-258>Beevor, pp. 257,258</ref> | |||

| ===Battle for the Reichstag=== | ===Battle for the Reichstag=== | ||

| {{see also|Raising a Flag over the Reichstag}} | |||

| ] (] ]) in ], after the battle. In the foreground two destroyed ] tanks can be seen]] | |||

| ] | |||

| In the early hours of |

In the early hours of 29 April the Soviet ] crossed the ] and started to fan out into the surrounding streets and buildings.{{sfn|Beevor|2003|pp=371–373}} The initial assaults on buildings, including the ], were hampered by the lack of supporting artillery. It was not until the damaged bridges were repaired that artillery could be moved up in support.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=349}} At 04:00 hours, in the ''Führerbunker'', Hitler signed his ] and, shortly afterwards, married ].{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=343}} At dawn the Soviets pressed on with their assault in the south-east. After very heavy fighting they managed to capture ] headquarters on ], but a Waffen-SS counter-attack forced the Soviets to withdraw from the building.{{sfn|Beevor|2003|p=375}} To the south-west the 8th Guards Army attacked north across the Landwehr canal into the Tiergarten.{{sfn|Beevor|2003|p=377}} | ||

| By the next day, |

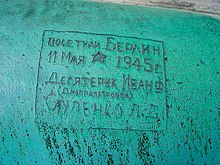

By the next day, 30 April, the Soviets had solved their bridging problems and with artillery support at 06:00 they launched an attack on the Reichstag, but because of German entrenchments and support from ]s {{cvt|2|km|mi}} away on the roof of the ], close by ], it was not until that evening that the Soviets were able to enter the building.{{sfn|Beevor|2003|p=380}} The Reichstag had not been in use since it had ] in February 1933 and its interior resembled a rubble heap more than a government building. The German troops inside were heavily entrenched,{{sfn|Hamilton|2008|p=311}} and fierce room-to-room fighting ensued. At that point there was still a large contingent of German soldiers in the basement who launched counter-attacks against the Red Army.{{sfn|Hamilton|2008|p=311}} By 2 May 1945 the Red Army controlled the building entirely.{{sfn|Beevor|2003|pp=390–397}} The famous photo of the two soldiers planting the flag on the roof of the building is a re-enactment photo taken the day after the building was taken.{{sfn|Sontheimer|2008}} To the Soviets the event as represented by the photo became symbolic of their victory demonstrating that the Battle of Berlin, as well as the Eastern Front hostilities as a whole, ended with the total Soviet victory.{{sfn|Bellamy|2007|pp=663–7}} As the 756th Regiment's commander ] had stated in his order to Battalion Commander ] "... the Supreme High Command ... and the entire Soviet People order you to erect the victory banner on the roof above Berlin".{{sfn|Hamilton|2008|p=311}} | ||

| ===Battle for the centre=== | ===Battle for the centre=== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| During the early hours |

During the early hours of 30 April, Weidling informed Hitler in person that the defenders would probably exhaust their ammunition during the night. Hitler granted him permission to attempt a ] through the encircling Red Army lines.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=358}} That afternoon, Hitler and Braun committed ] and their bodies were cremated not far from the bunker.{{sfn|Bullock|1962|pp=799, 800}} In accordance with Hitler's last will and testament, Admiral ] became the "]" (''Reichspräsident'') and Joseph Goebbels became the new ] ('']'').{{sfn|Williams|2005|pp=324, 325}} | ||

| As the perimeter shrank and the surviving defenders fell back, they became concentrated into a small area in the city centre. By now there were about 10,000 German soldiers in the city centre, which was being assaulted from all sides. One of the other main thrusts was along Wilhelmstrasse on which the Air Ministry, built of ], was pounded by large concentrations of Soviet artillery. The remaining German Tiger tanks of the ] battalion took up positions in the east of the Tiergarten to defend the centre against ] 3rd Shock Army (which although heavily engaged around the Reichstag was also flanking the area by advancing through the northern Tiergarten) and the 8th Guards Army advancing through the south of the Tiergarten. |

As the perimeter shrank and the surviving defenders fell back, they became concentrated into a small area in the city centre. By now there were about 10,000 German soldiers in the city centre, which was being assaulted from all sides. One of the other main thrusts was along Wilhelmstrasse on which the Air Ministry, built of ], was pounded by large concentrations of Soviet artillery.{{sfn|Beevor|2003|p=380}} The remaining German Tiger tanks of the ] battalion took up positions in the east of the Tiergarten to defend the centre against ]'s 3rd Shock Army (which although heavily engaged around the Reichstag was also flanking the area by advancing through the northern Tiergarten) and the 8th Guards Army advancing through the south of the Tiergarten.{{sfn|Beevor|2003|p=381}} These Soviet forces had effectively cut the sausage-shaped area held by the Germans in half and made any escape attempt to the west for German troops in the centre much more difficult.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|pp=385–386}} | ||

| During the early hours of |

During the early hours of 1 May, Krebs talked to General Chuikov, commander of the Soviet 8th Guards Army,<ref>{{harvnb|Dollinger|1967|p=239}}, states 3 am, and {{harvnb|Beevor|2003|p=391}}, 4 am, for Krebs' meeting with Chuikov</ref> informing him of Hitler's death and a willingness to negotiate a citywide surrender.{{sfn|Beevor|2003|p=391}} They could not agree on terms because of Soviet insistence on unconditional surrender and Krebs' claim that he lacked authorisation to agree to that.{{sfn|Dollinger|1967|p=239}} Goebbels was against surrender. In the afternoon, Goebbels and his wife ] and then themselves.{{sfn|Beevor|2003|p=405}} Goebbels's death removed the last impediment which prevented Weidling from accepting the terms of unconditional surrender of his garrison, but he chose to delay the surrender until the next morning to allow the planned breakout to take place under the cover of darkness.{{sfn|Beevor|2003|p=406}} | ||

| ===Breakout and surrender=== | ===Breakout and surrender=== | ||

| On the night of 1/2 May, most of the remnants of the Berlin garrison attempted to break out of the city centre in three different directions. Only those that went west through the Tiergarten and crossed the ] (a bridge over the Havel) into ] succeeded in breaching Soviet lines.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|pp=383–389}} Only a handful of those who survived the initial breakout made it to the lines of the Western Allies—most were either killed or captured by the Red Army's outer encirclement forces west of the city.{{sfn|Ziemke|1969|pp=125–126}} Early in the morning of 2 May, the Soviets captured the Reich Chancellery. General Weidling surrendered with his staff at 06:00 hours. He was taken to see General Vasily Chuikov at 08:23, where Weidling ordered the city's defenders to surrender to the Soviets.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=386}} | |||

| ] (left) among captured German generals on ], ]]] | |||

| ]'' prisoners of war in the streets of Berlin, 1945]] | |||

| The 350-strong garrison of the Zoo flak tower left the building. There was sporadic fighting in a few isolated buildings where some SS troops still refused to surrender, but the Soviets reduced such buildings to rubble.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=391}} | |||

| On the night of 1/2 May, most of the remnants of the Berlin garrison attempted to break out of the city centre in three different directions. Only those that went west through the Tiergarten and crossed the ] (a bridge over the ]) into ] succeeded in breaching Soviet lines.<ref name=beevor-383>Beevor, pp. 383–389</ref> However, only a handful of those who survived the initial breakout made it to the lines of the ] — most were either killed or captured by the Soviets.<ref name=ziemke-125-6>Ziemke, pp. 125,126</ref> Early in the morning of ], the Soviets captured the ]. The military historian Antony Beevor points out that as most of the German combat troops had left the area in the breakouts the night before, the resistance must have been far less than it had been inside the Reichstag.<ref>Beevor, p. 388</ref> General Weidling finally surrendered with his staff at 06:00 hours. He was taken to see General ] at 08:23. Weidling agreed to order the city's defenders to surrender to the Soviets.<ref>Beevor, p. 386</ref> Under General Chuikov's and ]'s direction, Weidling put his order to surrender in writing.<ref name="Dollinger-239"/> | |||

| ===Hitler's Nero Decree=== | |||

| The 350-strong garrison of the Zoo flak tower finally left the building. While there was sporadic fighting in a few isolated buildings where some SS troops still refused to surrender, the Soviets simply reduced such buildings to rubble.<ref>Beevor, p. 409</ref> Beevor suggests that most Germans, both soldiers and civilians, were grateful to receive food issued at Red Army soup kitchens. The Soviets went house to house and rounded up anyone in a uniform including firemen and railway-men and marched them all eastward as prisoners of war.<ref name=Beevor-388-393>Beevor, pp. 388–393</ref> | |||

| The city's food supplies had been largely destroyed on Hitler's orders. 128 of the 226 bridges had been blown up and 87 pumps rendered inoperative. "A quarter of the subway stations were under water, flooded on Hitler's orders. Thousands and thousands who had sought shelter in them had drowned when the SS had carried out the blowing up of the protective devices on the Landwehr Canal."{{sfn|Engelmann|1986|p=266}} A number of workers, on their own initiative, resisted or sabotaged the SS's plan to destroy the city's infrastructure; they successfully prevented the blowing up of the Klingenberg power station, the Johannisthal waterworks, and other pumping stations, railroad facilities, and bridges.{{sfn|Engelmann|1986|p=266}} | |||

| ==Battle outside Berlin== | ==Battle outside Berlin== | ||

| At some point on 28 April or 29 April, General Heinrici, Commander-in-Chief of Army Group Vistula, was relieved of his command after disobeying Hitler's direct orders to hold Berlin at all costs and never order a retreat, and was replaced by General ].{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=338}} General ] was named as Heinrici's interim replacement until Student could arrive and assume control. There remains some confusion as to who was in command, as some references say that Student was captured by the British and never arrived.{{sfn|Dollinger|1967|p=228}} Regardless of whether von Tippelskirch or Student was in command of Army Group Vistula, the rapidly deteriorating situation that the Germans faced meant that Army Group Vistula's coordination of the armies under its nominal command during the last few days of the war was of little significance.{{sfn|Ziemke|1969|p=128}} | |||

| On the evening of 29 April, Krebs contacted General Alfred Jodl (Supreme Army Command) by radio:{{sfn|Dollinger|1967|p=239}} {{quote|text=Request immediate report. Firstly of the whereabouts of Wenck's spearheads. Secondly of time intended to attack. Thirdly of the location of the IX Army. Fourthly of the precise place in which the IX Army will break through. Fifthly of the whereabouts of General ]'s spearhead.}} | |||

| At some point on ] or ], General ], Commander-in-Chief of ], was relieved of his command after disobeying Hitler's direct orders to hold Berlin at all costs and never order a retreat, and was replaced by General ].<ref name=Beevor-338>Beevor, p. 338</ref> General ] was named as Heinrici's interim replacement until Student could arrive and assume control.<ref name=EB>Exton, Brett. ''''. Retrieved on ] ].</ref> There remains some confusion as to who was actually in command as some references say that Student was captured by the British and never arrived.<ref name="Dollinger-228"/> Regardless of whether von Tippelskirch or Student was in command of Army Group Vistula, the rapidly deteriorating situation that the Germans faced meant that Army Group Vistula coordination of the armies under its nominal command during the last few days of the war was of little significance.<ref name=Ziemke-128>Ziemke, p. 128</ref> | |||

| In the early morning of 30 April, Jodl replied to Krebs:{{sfn|Dollinger|1967|p=239}} {{quote|text=Firstly, Wenck's spearhead bogged down south of ]. Secondly, the XII Army therefore unable to continue attack on Berlin. Thirdly, bulk of the IX Army surrounded. Fourthly, Holste's ] on the defensive.}} | |||

| ===North=== | |||

| In the early morning of ], Jodl replied to Krebs:<ref name="Dollinger-239"/> {{bquote|Firstly, Wenck's spearhead bogged down south of ]. Secondly, XII Army therefore unable to continue attack on Berlin. Thirdly, bulk of IX Army surrounded. Fourthly, ] ] on the defensive.}} | |||

| While the 1st Belorussian Front and the 1st Ukrainian Front ], and started ], Rokossovsky's 2nd Belorussian Front started his offensive to the north of Berlin. On 20 April between Stettin and Schwedt, Rokossovsky's 2nd Belorussian Front attacked the northern flank of Army Group Vistula, held by the III Panzer Army.{{sfn|Ziemke|1969|p=84}} By 22 April, the 2nd Belorussian Front had established a bridgehead on the east bank of the Oder that was over {{cvt|15|km|mi|0}} deep and was heavily engaged with the III Panzer Army.{{sfn|Ziemke|1969|p=92}} On 25 April, the 2nd Belorussian Front broke through III Panzer Army's line around the bridgehead south of Stettin, crossed the ''Randowbruch'' Swamp, and were now free to move west towards ]'s ] and north towards the Baltic port of ].{{sfn|Ziemke|1969|p=94}} | |||

| The German III Panzer Army and the ] situated to the north of Berlin retreated westwards under relentless pressure from Rokossovsky's 2nd Belorussian Front, and was eventually pushed into a pocket {{cvt|20|mi|km|order=flip}} wide that stretched from the Elbe to the coast.{{sfn|Beevor|2003|p=353}} To their west was the British 21st Army Group (which on 1 May broke out of its Elbe bridgehead and had raced to the coast capturing ] and ]), to their east Rokossovsky's 2nd Belorussian Front and to the south was the ] which had penetrated as far east as ] and ].{{sfn|Ziemke|1969|p=129}} | |||

| === North === | |||

| While the 1st Belorussian Front and the 1st Ukrainian Front ], and started ], Rokossovsky's 2nd Belorussian Front started his offensive to the north of Berlin. On the ] between ] and ], Rokossovsky's 2nd Belorussian Front attacked the northern flank of Army Group Vistula, held by the ].<ref name=Ziemke84/> By ], the 2nd Belorussian Front had established a bridgehead on the east bank of the Oder that was over 15 km deep and was heavily engaged with the III Panzer Army.<ref name=Ziemke92>Ziemke, p. 92</ref> On ], the 2nd Belorussian Front broke through III Panzer Army's line around the bridgehead south of ], crossed the ''Randowbruch'' Swamp, and were now free to move west towards ] ] and north towards the Baltic port of ].<ref name=Ziemke94>Ziemke, p. 94</ref> | |||

| ===South=== | |||

| The German III Panzer Army and the ] situated to the north of Berlin retreated westwards under relentless pressure from Rokossovsky's 2nd Belorussian Front, and was eventually pushed into a pocket 20 miles (32 km) wide that stretched from the Elbe to the coast. To their west was the British 21st Army Group (which on ] broke out of its Elbe bridgehead and had raced to the coast capturing ] and ]), to their east Rokossovsky's 2nd Belorussian Front and to the south was the ] which had penetrated as far east as ] and ].<ref name=Ziemke-129>Ziemke, p. 129</ref> | |||

| {{see also|Battle of Halbe}} | |||

| ], Germany.]] | |||

| The successes of the 1st Ukrainian Front during the first nine days of the battle meant that by 25 April, they were occupying large swathes of the area south and south-west of Berlin. Their spearheads had met elements of the 1st Belorussian Front west of Berlin, completing the investment of the city.{{sfn|Ziemke|1969|p=94}} Meanwhile, the ] of the ] in 1st Ukrainian Front ] with the ] of the ] near ], on the Elbe River.{{sfn|Ziemke|1969|p=94}} These manoeuvres had broken the German forces south of Berlin into three parts. The German IX Army was surrounded in the ].{{sfn|Beevor|2003|p=350}} Wenck's XII Army, obeying Hitler's command of 22 April, was attempting to force its way into Berlin from the south-west but met stiff resistance from 1st Ukrainian Front around ].{{sfn|Beevor|2003|pp=345–346}} Schörner's Army Group Centre was forced to withdraw from the Battle of Berlin, along its lines of communications towards ].{{sfn|Beevor|2003|p=426}} | |||

| === South === | |||

| {{See also|Battle of Halbe}} | |||

| ], Germany.]] | |||

| The successes of the 1st Ukrainian Front during the first nine days of the battle meant that by ], they were in occupying large swaths of the area south and south west of Berlin. Their spearheads had met elements of the 1st Belorussian Front west of Berlin, completing the investment of the city. Meanwhile, the 1st Ukrainian Front's ] of the ] ] with the ] of the ] near ], on the ] River.<ref name=Ziemke94/> These manoeuvres had broken the German forces south of Berlin into three parts. The German IX army was surrounded in the ]. Wenck's XII Army, obeying Hitler's command of the ], was attempting to force its way into Berlin from the south west but met stiff resistance from units of the 1st Ukrainian Front in the area of ]. Schörner's Army Group Centre was forced to withdraw from the Battle of Berlin, along its lines of communications towards ].<ref>Beevor, p. 443</ref> | |||

| Between |

Between 24 April and 1 May, the IX Army fought a desperate action to break out of the pocket in an attempt to link up with the XII Army.{{sfn|Le Tissier|2005|p=117}} Hitler assumed that after a successful breakout from the pocket, the IX Army could combine forces with the XII Army and would be able to relieve Berlin.{{sfn|Le Tissier|2005|pp=89, 90}} There is no evidence to suggest that Generals Heinrici, Busse, or Wenck thought that this was even remotely strategically feasible, but Hitler's agreement to allow the IX Army to break through Soviet lines allowed many German soldiers to escape to the west and surrender to the United States Army.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=330}} | ||

| At dawn on |

At dawn on 28 April, the youth divisions '']'', '']'', and '']'' attacked from the south-west toward the direction of Berlin. They were part of Wenck's ] and were made up of men from the officer training schools, making them some of the best units the Germans had in reserve. They covered a distance of about {{cvt|24|km|mi|0}}, before being halted at the tip of Lake Schwielow, south-west of Potsdam and still {{cvt|32|km|mi}} from Berlin.{{sfn|Ziemke|1969|p=119}} During the night, General Wenck reported to the German Supreme Army Command in Fuerstenberg that his XII Army had been forced back along the entire front. According to Wenck, no attack on Berlin was possible.{{sfn|Ziemke|1969|p=120}}{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=350}} At that point, support from the IX Army could no longer be expected.{{sfn|Dollinger|1967|p=239}} In the meantime, about 25,000 German soldiers of the IX Army, along with several thousand civilians, succeeded in reaching the lines of the XII Army after breaking out of the Halbe pocket.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=378}} The casualties on both sides were very high. Nearly 30,000 Germans were buried after the battle in the cemetery at Halbe.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=337}} About 20,000 soldiers of the Red Army also died trying to stop the breakout; most are buried at a cemetery next to the Baruth-Zossen road.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=337}} These are the known dead, but the remains of more who died in the battle are found every year, so the total of those who died will never be known. Nobody knows how many civilians died but it could have been as high as 10,000.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=337}} | ||

| ] amid the ruins of Berlin, June 1945]] | |||

| Having failed to break through to Berlin, Wenck's XII army made a fighting retreat back towards the Elbe and American lines after providing the IX Army survivors with surplus transport.<ref name="beevor-395">Beevor, p. 395</ref> By ] many German Army units and individuals had crossed the Elbe and surrendered to the ].<ref name=Ziemke-128/> Meanwhile, the XII's bridgehead with its headquarters in the park of ], had come under under heavy Soviet artillery bombardment and had been compressed into an area eight by two kilometres (five by one and a quarter miles)<ref name=Beevor-397>Beevor, p. 397</ref> | |||

| Having failed to break through to Berlin, Wenck's XII Army made a fighting retreat back towards the Elbe and American lines after providing the IX Army survivors with surplus transport.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=395}} By 6 May many German Army units and individuals had crossed the Elbe and surrendered to the US Ninth Army.{{sfn|Ziemke|1969|p=128}} Meanwhile, the XII Army's bridgehead, with its headquarters in the park of ], came under heavy Soviet artillery bombardment and was compressed into an area eight by two kilometres (five by one and a quarter miles).{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=397}} | |||

| ===Surrender=== | ===Surrender=== | ||

| On the night of 2–3 May, General von Manteuffel, commander of the III Panzer Army along with General von Tippelskirch, commander of the XXI Army, surrendered to the US Army.{{sfn|Ziemke|1969|p=128}} Von Saucken's II Army, that had been fighting north-east of Berlin in the Vistula Delta, surrendered to the Soviets on 9 May.{{sfn|Ziemke|1969|p=129}} On the morning of 7 May, the perimeter of the XII Army's bridgehead began to collapse. Wenck crossed the Elbe under small arms fire that afternoon and surrendered to the American Ninth Army.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=397}} | |||

| ]'' prisoners captured by 1st Belorussian front, Berlin, 1945]] | |||

| On the night of 2/3 May, General ], commander of the III Panzer Army along with General ], commander of the XXI Army, surrendered to the US Army.<ref name=Ziemke-128>Ziemke, p. 128</ref> Von Saucken's II Army, that had been fighting north east of Berlin in the Vistula Delta, surrendered to the Soviets on ].<ref name=Ziemke-129/> On the morning of ], the perimeter of Wenck's XII Army's bridgehead began to collapse. Wenck crossed the Elbe under small arms fire that afternoon and surrendered to the American Ninth Army.<ref name=Beevor-397>Beevor, p. 397</ref> | |||

| ==Aftermath== | ==Aftermath== | ||

| ] | ], 3 July 1945]] | ||

| ], ]]] | |||

| According to ], declassified archival data gives 81,116 Soviet dead for the operation, including the battles of Seelow Heights and the Halbe.{{sfn|Krivosheev|1997|p=157}} Another 280,251 were reported wounded or sick.{{sfn|Krivosheev|1997|pp=157,158}}{{efn|name=Casualties}} The operation also cost the Soviets about 1,997 tanks and self-propelled guns.{{sfn|Krivosheev|1997|p=263}} All losses were considered irrecoverable – i.e. beyond economic repair or no longer serviceable.{{sfn|Krivosheev|1997|p=3}} The Soviets claimed to have captured nearly 480,000 German soldiers,{{sfn|Glantz|1998|p=271}}{{efn|name=CapturedPrisoners}} while German research put the number of dead between 92,000 and 100,000.{{sfn|Müller|2008|p=673}} Some 125,000 civilians are estimated to have died during the entire operation.{{sfn|Clodfelter|2002|p=515}} | |||

| ] stands beside them, ] ].]] | |||

| According to ]'s work based on declassified archival data, Soviet forces sustained 81,116 dead for the entire operation, which included the Battles of Seelow Heights and the Halbe;<ref name=Khrivosheev-219-220/> some earlier Western estimates are much higher.<ref name="Glantz"/> Another 280,251 were reported wounded or sick during the operational period. Included in that total are Polish forces, which lost 2,825 killed or missing and 6,067 wounded in the operation.<ref name=Khrivosheev-219-220/> The operation also cost the Soviets about 2,000 armored vehicles, though the number of irrevocable losses (write-offs) is not known. Initial Soviet estimates based on kill claims placed German losses at 458,080 killed and 479,298 captured.<ref group=nb>captured prisoners included many unarmed men in uniform, such as railway officials and members of the Reich Labour Service.(Beevor, p. 287)</ref> The number of civilian casualties is unknown.<ref>Glantz, p. 271</ref> | |||

| In those areas that the Red Army had captured and before the fighting in the centre of the city had stopped, the Soviet authorities took measures to start restoring essential services.{{sfn|Bellamy|2007|p=670}} Almost all transport in and out of the city had been rendered inoperative, and bombed-out sewers had contaminated the city's water supplies.{{sfn|White|2003|p=126}} The Soviet authorities appointed local Germans to head each city block, and organised the cleaning-up.{{sfn|Bellamy|2007|p=670}} The Red Army made a major effort to feed the residents of the city.{{sfn|Bellamy|2007|p=670}} Most Germans, both soldiers and civilians, were grateful to receive food issued at Red Army ]s, which began on Colonel-General Berzarin's orders.{{sfn|Beevor|2002|p=409}} After the capitulation the Soviets went house to house, arresting and imprisoning anyone in a uniform including ] and ].{{sfn|Beevor|2002|pp=388–393}} | |||

| ] | |||