| Revision as of 09:32, 6 October 2008 editFlewis (talk | contribs)Rollbackers22,936 editsm Reverted edits by 164.164.97.81 to last version by Nitsansh (HG)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 00:41, 20 December 2024 edit undoColtsfan (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users14,019 editsmNo edit summary | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Criminal punishment}} | |||

| {{redirect-multi|3|Life sentence|Life Sentence|Life term|other uses|Life Sentence (disambiguation)|lifelong terms of office|Life tenure}} | |||

| {{distinguish|Indefinite imprisonment}} | |||

| {{Criminal procedure (trial)}} | {{Criminal procedure (trial)}} | ||

| <!--This article is in Commonwealth English--> | |||

| '''Life imprisonment''' or '''life incarceration''' is a ] of ] for a serious crime, often for most or even all of the criminal's remaining life, but in fact for a period which varies between jurisdictions: many countries have a maximum possible period of time (usually 7 to 50 years or forever) a prisoner may be incarcerated, or require the possibility of ] after a set amount of time. | |||

| '''Life imprisonment''' is any ] of ] for a ] under which the convicted criminal is to remain in ] for the rest of their natural life (or until ]ed, ]d, or commuted to a fixed term). Crimes that result in life imprisonment are considered extremely serious and usually violent. Examples of these crimes are ], ], ], ] ], ], ], ], ], ], severe ] and ]s, ] ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ]. | |||

| In almost all jurisdictions without ], life imprisonment (especially ]) constitutes the most severe form of criminal punishment. Only a small number of jurisdictions have abolished both. | |||

| Common law murder is one of the only crimes in which life imprisonment is mandatory; mandatory life sentences for murder are given in several countries, including some states of the ] and ].<ref>{{Cite web |last=Government of Canada |first=Department of Justice |date=2015-07-23 |title=How sentences are imposed - Canadian Victims Bill of Rights |url=https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/cj-jp/victims-victimes/sentencing-peine/imposed-imposees.html#:~:text=In%20Canada,%20murder%20is%20either,25%20years%20of%20their%20sentence. |access-date=2023-08-26 |website=www.justice.gc.ca}}</ref> Life imprisonment (as a maximum term) can also be imposed, in certain countries, for traffic offences causing death.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.madd.org/laws/law-overview/Vehicular_Homicide_Overview.pdf|title=Penalties for Drunk Driving Vehicular Homicide|publisher=Mothers Against Drunk Driving|date=May 2012|type=PDF|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130923054038/http://www.madd.org/laws/law-overview/Vehicular_Homicide_Overview.pdf|archive-date=23 September 2013|df=dmy-all}}</ref> Life imprisonment is not used in all countries; ] was the first country to abolish life imprisonment, in 1884,<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.nationmaster.com/country-info/stats/Crime/Punishment/Minimum-life-sentence-to-serve-before-eligibility-for-requesting-parole|title=Crime > Punishment > Minimum life sentence to serve before eligibility for requesting parole: Countries Compared | |||

| ==Children and teenagers under 18== | |||

| |website=nationmaster.com|access-date=3 July 2023}}</ref> and all other ] also have maximum imprisonment lengths, as well as all ] except for Cuba, Peru, Argentina, Chile and the Mexican state of ]. Other countries that do not practice life sentences include Mongolia in Asia and Norway, Iceland, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Andorra and Montenegro in Europe. | |||

| Like other areas of ], sentences handed to ] may differ from those given to legal ]s. About a dozen countries worldwide allow for minors to be given lifetime sentences that have no provision for eventual release. Of these, only some{{ndash}} ], ], ], and the ]{{ndash}} actually have minors serving such sentences, according to a 2005 joint study by ] and ]. Although South Africa does allow life imprisonment for children below 18 years of age, it is not without the possibility of release. In terms of parole laws, a person sentenced to life will be eligible for parole after serving 25 years. Of these, the United States has by far the largest number of people serving life sentences for crimes they committed as minors: 9,700, of which 2,200 are without the possibility of parole, as of October 2005. Only 12 other juvenile courts have such sentences in the rest of the world.<ref>"", 2005. ISBN 1-56432-335-8. Summary: "". Human Rights Watch, October 12, 2005.</ref><ref>Liptak, Adam (2005). "". ''The New York Times''. October 3.</ref> | |||

| Where life imprisonment is a possible sentence, there may also exist formal mechanisms for requesting parole after a certain period of prison time. This means that a convict could be entitled to spend the rest of the sentence (until that individual dies) outside prison. Early release is usually conditional on past and future conduct, possibly with certain restrictions or obligations. In contrast, when a fixed term of imprisonment has ended, the convict is free. The length of time served and the conditions surrounding parole vary. Being eligible for parole does not necessarily ensure that parole will be granted. In some countries, including Sweden, parole does not exist but a life sentence may – after a successful application – be commuted to a fixed-term sentence, after which the offender is released as if the sentence served was that originally imposed. | |||

| In many countries around the world, particularly in the ], courts have been given the authority to pass prison terms that may amount to ''de'' ''facto'' life imprisonment, meaning that the sentence would last longer than the human life expectancy.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.cnn.com/2013/08/01/justice/ohio-castro/index.html|title=Cleveland kidnapper Ariel Castro sentenced to life, plus 1,000 years |first1=Eliott C. |last1=McLaughlin |first2=Pamela|last2=Brown|website=CNN|date=August 2013 |access-date=2017-05-12|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170610120019/http://www.cnn.com/2013/08/01/justice/ohio-castro/index.html|archive-date=10 June 2017|df=dmy-all}}</ref> For example, courts in South Africa have handed out at least two sentences that have exceeded a century, while in ], Australia, ], the perpetrator of the ] in 1996, received 35 life sentences plus 1,035 years without parole. In the United States, ], the perpetrator of the ], received 12 consecutive life sentences plus 3,318 years without the possibility of parole.<ref>{{cite web|title=Snapshot: Australia's longest sentences|url=https://www.sbs.com.au/news/snapshot-australia-s-longest-sentences|access-date=2021-06-03|website=SBS News|language=en}}</ref> In the case of mass murder in the US, Parkland mass murderer ] was sentenced to 34 consecutive terms of life imprisonment (without parole) for murdering 17 people and injuring another 17 at a school.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.todayonline.com/world/florida-school-mass-shooter-sentenced-life-prison-2035841|title=Florida school mass shooter sentenced to life in prison|newspaper=]|location=Singapore|date=3 November 2022|access-date=3 November 2022}}</ref> Any sentence without parole effectively means a sentence cannot be suspended; a life sentence without parole, therefore, means that in the absence of unlikely circumstances such as ], ] or ] (e.g. imminent death), the prisoner will spend the rest of their natural life in prison. In several countries where ''de facto'' life terms are used, a release on humanitarian grounds (also known as compassionate release) is commonplace, such as in the case of ]. Since the behaviour of a prisoner serving a life sentence without parole is not relevant to the execution of such sentence, many people among ]s, penitentiary specialists, ], but most of all among ] oppose that punishment. In particular, they emphasize that when faced with a prisoner with no hope of being released ever, the prison has no means to discipline such convict effectively. | |||

| ==Interpretation in Europe== | |||

| ===Austria=== | |||

| Life imprisonment theoretically means imprisonment until the prisoner dies. After 15 years parole is possible, if and when it can be assumed that the inmate will not re-offend. This is subject to the discretion of a criminal court panel, and possible appeal to the high court. Alternatively, the President may grant a ] upon motion of the Minister of Justice. Prisoners who committed a crime when below the age of 21 can be sentenced to a maximum of 20 years imprisonment. | |||

| A few countries allow for a minor to be given a life sentence without parole; these include but are not limited to: Antigua and Barbuda, Argentina (only over the age of 16),<ref>{{cite web|url=http://infoleg.mecon.gov.ar/infolegInternet/anexos/110000-114999/114167/texact.htm|title=InfoLEG – Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas Públicas – Argentina|author=Mecon|work=mecon.gov.ar|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160109182945/http://infoleg.mecon.gov.ar/infolegInternet/anexos/110000-114999/114167/texact.htm|archive-date=9 January 2016|df=dmy-all}}</ref> Australia, Belize, Brunei, Cuba, Dominica, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, the Solomon Islands, Sri Lanka, and the United States. According to a ] study, only the U.S. had minors serving such sentences in 2008.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.usfca.edu/law/jlwop/other_nations/ |title=Laws of Other Nations |work=usfca.edu |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150627124859/http://www.usfca.edu/law/jlwop/other_nations/ |archive-date=27 June 2015 }}</ref> In 2009, ] estimated that there were 2,589 youth offenders serving life sentences without the possibility for parole in the U.S.<ref>" {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150627055126/http://www.hrw.org/en/reports/2008/05/01/executive-summary-rest-their-lives |date=27 June 2015 }}", 2008.</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.hrw.org/en/news/2009/10/02/state-distribution-juvenile-offenders-serving-juvenile-life-without-parole |title=State Distribution of Youth Offenders Serving Juvenile Life Without Parole (JLWOP) |publisher=Human Rights Watch |date=2 October 2009 |access-date=3 August 2011 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110608024141/http://www.hrw.org/en/news/2009/10/02/state-distribution-juvenile-offenders-serving-juvenile-life-without-parole |archive-date=8 June 2011 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> Since the start of 2020, that number has fallen to 1,465.<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/juvenile-life-without-parole/ | title=Juvenile Life Without Parole: An Overview }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/09/13/us-states-fail-protect-childrens-rights |title=US States Fail to Protect Children's Rights |publisher=] |date=2022-09-13 |access-date=2022-10-11}}</ref> The United States has the highest population of prisoners serving life sentences for both adults and minors, at a rate of 50 people per 100,000 (1 out of 2,000) residents imprisoned for life.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sentencingproject.org/detail/news.cfm?news_id=1636&id=107 |title=The Sentencing Project News – New Publication: Life Goes On: The Historic Rise in Life Sentences in America |work=sentencingproject.org |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131018011248/http://www.sentencingproject.org/detail/news.cfm?news_id=1636&id=107 |archive-date=18 October 2013 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Belgium=== | |||

| Life imprisonment theoretically means imprisonment until the prisoner dies. However, a life sentence is assimilated to 30 years imprisonment, to determine when the prisoner will become eligible for parole: he can apply after a third of that sentence has been served, if convicted of a first criminal offence, or after two third if recidivist. Parole has to be granted by a jurisdiction, and the judgement can be appealed. Alternately, release can be postponed, even if the prisoner is eligible for parole, or is at the end of his sentence, if the trial court has added a security period "at the disposal of the government", for no longer than the maximum period set forth by the criminal trial court. | |||

| ==World view== | |||

| ===Bosnia and Herzegovina=== | |||

| Before Bosnia and Herzegovina became independent in 1992, the maximum time a prisoner was to spend in jail was 20 years. The "life term" has been increased to 40 years since independence; however, no prisoner serves more than 10 to 20 years; most of them are pardoned for good behavior. Lesser penalties are given to offenders under the age of 18. | |||

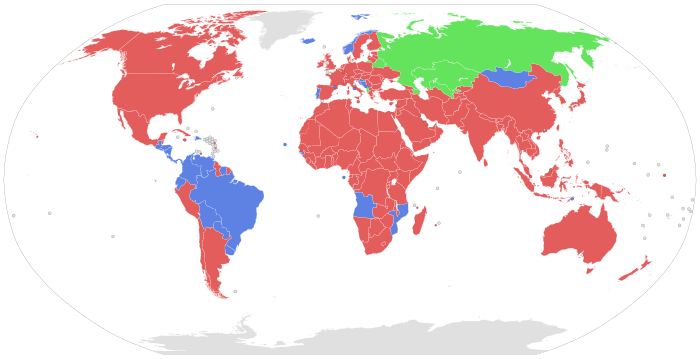

| [[File:LifeSentenceMapNew.svg|center|700px|thumb|Life imprisonment laws around the world:<ref>{{cite web|url=http://life-imprisonment.html/|title=Life imprisonment|website=life-imprisonment.html}}</ref> | |||

| ===Croatia=== | |||

| {{legend|#e35d5d|Life imprisonment is a legal penalty.}} | |||

| The maximum sentence in Croatia is 40 years. | |||

| {{legend|#66e35d|Life imprisonment is a legal penalty, but with certain restrictions.}} | |||

| {{legend|#5d82e3|Life imprisonment is illegal.}} | |||

| {{legend|#e0e0e0|Unknown}}]] | |||

| == |

==By country == | ||

| A life sentence (''Livsvarigt fængsel'' in ]) theoretically means until death, with no parole. However, prisoners are entitled to a pardoning hearing after 12 years, and upon motion of the minister of justice, the Danish King or Queen may grant a ], subject to a 5-year probationary period. Prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment serve an average of 16 years, more for cases considered to be particularly grave. The only example in modern times of an individual serving significantly more than 16 years in prison is ], who served 33 years for a quadruple police murder. Criminals considered dangerous can be sentenced to ''indefinite detention'', and such prisoners are kept in prison until they are no longer considered dangerous (normally used for mentally ill criminals)). On average they serve 9 years before being released and then they will remain on probation for 5 years. However prisoners eligible for a life sentence are usually not given indefinite detention, as it is considered a lesser sentence than life. Persons under 18 can only be sentenced to 8 years imprisonment or indefinite detention. | |||

| In several countries, life imprisonment has been effectively abolished. Many of the countries whose governments have abolished both life imprisonment and indefinite imprisonment have been culturally influenced or colonized by ] or ] and have written such prohibitions into their current constitutional laws (including Portugal itself but not Spain).<ref name=rtve>{{cite news |title=El Congreso aprueba la prisión permanente revisable con el único apoyo del Partido Popular|trans-title=Congress approves permanent revisable prison with support only from the People's Party|url=https://www.rtve.es/noticias/20150326/congreso-aprueba-prision-permanente-revisable-unicos-votos-del-partido-popular/1123040.shtml |access-date=29 December 2020 |publisher=] |date=26 March 2015 |language=Spanish}}</ref><ref name=efe>{{cite news |title=El Constitucional avala la prisión permanente revisable|trans-title=Constitutional court upholds permanent reviewable prison|url=https://www.efe.com/efe/espana/politica/el-tribunal-constitucional-avala-la-prision-permanente-revisable/10002-4646083 |access-date=9 October 2021 |publisher=] |date=6 October 2021 |language=Spanish}}</ref> | |||

| ===Estonia=== | |||

| Life imprisonment means imprisonment until death. It is theoretically possible that the president may grant clemency, allowing possibility of parole; however, it has never happened. | |||

| === |

===Europe=== | ||

| Inmates jailed for life are eligible for parole after 18 years served, or after 22 years for recidivist offenders. Since 1994, for ] involving rape or torture, the Court can impose a term of 30 years or decide that the defendant cannot be paroled . | |||

| A number of European countries have abolished all forms of indefinite imprisonment. ] and ] each set the maximum prison sentence at 45 years, and Portugal abolished all forms of life imprisonment with the ]s of Sampaio e Melo in 1884 and has a maximum sentence of 25 years.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Ramalho|first=Énio|url=https://www.legislationline.org/download/id/4288/file/Portugal_CC_2006_en.pdf|title=THE PORTUGUESE PENAL CODE, GENERAL PART (ARTICLES 1–130)|publisher=verbojuridico|year=2016|page=12|chapter=II}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|last=Bruno|first=Cátia|title=25 anos de prisão. A história da pena máxima em Portugal|url=https://observador.pt/2018/03/08/25-anos-de-prisao-a-historia-da-pena-maxima-em-portugal/|access-date=2021-01-13|website=Observador|language=pt-PT}}</ref> | |||

| It is possible to give a reduction of this term for serious signs of social re-adaptation, past 20 years if the terms is to 30 years and past 30 years if the inmate is under decision that he cannot be paroled. | |||

| Life imprisonment in Spain was abolished in 1928, but reinstated in 2015 and upheld by the ] in 2021.<ref name=rtve/><ref name=efe/><ref name=pais>{{cite news |title=Una figura instaurada en 1822 y eliminada en 1928 |trans-title=A statute installed in 1822 and abolished in 1928|url=https://elpais.com/politica/2015/01/21/actualidad/1421873508_079804.html |access-date=29 December 2020 |work=] |date=21 January 2020 |language=Spanish}}</ref> ] previously had a maximum prison sentence of 40 years; life imprisonment was instated in 2019 by amendments to the country's criminal code, alongside a ].<ref>{{cite web |title=Krivični zakonik |url=https://www.paragraf.rs/propisi/krivicni-zakonik-2019.html |access-date=2022-09-03 |website=www.paragraf.rs |language=sr}}</ref> | |||

| It is possible to be freed before these terms for serious health reasons. | |||

| In ], there are many jurisdictions where the law expressly provides for life sentences without the possibility of parole. These are ] (within the ]; see ]), the ], ], ],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.legislationline.org/documents/section/criminal-codes/country/39|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171007053656/http://legislationline.org/documents/section/criminal-codes/country/39|url-status=dead|title=Bulgaria – Criminal codes – Legislationline|archive-date=7 October 2017|website=www.legislationline.org}}</ref> ] (only for persons who refuse to cooperate with authorities and are sentenced for ] activities or ]), ], ], ], ], and ].<ref>{{cite web |title=Krivični zakonik |url=https://www.paragraf.rs/propisi/krivicni-zakonik-2019.html |access-date=2022-09-03 |website=www.paragraf.rs |language=sr}}</ref> | |||

| Life imprisonment can be sentenced for aggravated murder, treason, terrorism, drug trafficking and other serious felonies resulting in death or involving torture. | |||

| In ], although the law does not expressly provide for life without the possibility of release, some convicted persons may never be released, on the grounds that they are too dangerous. In ], persons who refuse to cooperate with authorities and are sentenced for mafia activities or terrorism are ineligible for parole and thus will spend the rest of their lives in prison. In Austria, life imprisonment will mean imprisonment for the remainder of the offender's life unless clemency is granted by the ] or it can be assumed that the convicted person will not commit any further crimes; the probationary period is ten years.<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/NormDokument.wxe?Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=10002296&Artikel=&Paragraf=46&Anlage=&Uebergangsrecht= | title=RIS - Strafgesetzbuch § 46 - Bundesrecht konsolidiert, tagesaktuelle Fassung }}</ref> In Malta, prior to 2018, there was previously never any possibility of parole for any person sentenced to life imprisonment, and any form of release from a life sentence was only possible by clemency granted by the ]. In ], while the law does not expressly provide for life imprisonment without any possibility of parole, a court can rule in exceptionally serious circumstances that convicts are ineligible for automatic parole consideration after 30 years if convicted of child murder involving rape or torture, premeditated murder of a state official or terrorism resulting in death. In ], there is never a possibility of parole for anyone sentenced to life imprisonment, as life imprisonment is defined as the "deprivation of liberty of the convict for the entire rest of his/her life". Where mercy is granted in relation to a person serving life imprisonment, imprisonment thereof must not be less than 30 years. In ], life imprisonment means for the rest of one's life with the only possibilities for release being a terminal illness or a presidential pardon.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://khpg.org//en/1552444710|title=Ukraine found in violation of the prohibition of torture over treatment of life prisoners|website=Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group}}</ref> In Albania, while no person sentenced to life imprisonment is eligible for standard parole, a conditional release is still possible if the prisoner is found not likely to re-offend and has displayed good behaviour, and has served at least 25 years. | |||

| There are an average of 25 sentences of life imprisonment by years (for 500 to 1000 murders by years) and 550 inmates jailed for life. | |||

| Before 2016 in the ], there was never a possibility of parole for any person sentenced to life imprisonment, and any form of release for life convicted in the country was only possible when granted royal decree by the ], with the last granting of a pardon taking place in 1986 when a terminally ill convict was released. As of 1970, the Dutch monarch has pardoned a total of three convicts. Although there is no possibility of parole eligibility, since 2016 prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment in the Netherlands are eligible to have their cases reviewed after serving at least 25 years. This change in law was because the ] stated in 2013 that lifelong imprisonment without the chance of being released is inhuman.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.rechtspraak.nl/Themas/Levenslang#301c0ce6-af28-4346-9b8b-3aa80761dbedfd65dac8-7cae-4cfd-87d0-d06985d756584 |website=rechtspraak.nl |language=Dutch|title=Levenslang }}</ref> | |||

| Persons under 16 years old cannot be sentenced to life, but, between 16 and 18 years it is possible by special decision. | |||

| Even in other European countries that do provide for life without parole, courts continue to retain judicial discretion to decide whether a sentence of life should include parole or not. In ], the decision of whether or not a life-convicted person is eligible for parole is up to the prison complex after 25 years have been served, and release eligibility depends on the prospect of ] and how likely they are to re-offend. In Europe, only Ukraine and Moldova explicitly exclude parole or any form of sentence commutation for life sentences in all cases. | |||

| ===Finland=== | |||

| Historically, the ] has been the only person with the power to grant parole to the convicts imprisoned for life (see ]). Starting on ], ], this power has also been given to Helsinki Court of Appeal (Helsingin hovioikeus), and is effectively transferred there. A life prisoner is considered for parole after serving 12 years. If the parole is rejected, a new parole hearing is scheduled in 2 years. If the parole is accepted, 3 years of supervised parole follows until full parole, assuming no violations. If the convict was less than 21 years of age when they committed the crime, the first parole hearing is after 10 years served. Life imprisonment cannot be sentenced for a crime that has been committed while the offender was under 18 years of age. | |||

| === |

===South America=== | ||

| The minimum time to be served for a sentence of life imprisonment (''Lebenslängliche Freiheitsstrafe'') is 15 years, after which the prisoner can apply for parole. | |||

| In South and Central America, Honduras, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Costa Rica, Venezuela, Colombia, Uruguay, Bolivia, Ecuador, and the Dominican Republic have all abolished life imprisonment. The maximum sentence is 75 years in El Salvador, 60 years in Colombia, 50 years in Costa Rica and Panama, 40 years in Honduras and Brazil,<ref>{{Cite web |title=Presidência da República - Secretaria-Geral - Subchefia para Assuntos Jurídicos - CÓDIGO PENAL - "Art. 75. O tempo de cumprimento das penas privativas de liberdade não pode ser superior a 40 (quarenta) anos. |url=https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2019-2022/2019/Lei/L13964.htm#art2}}</ref> 30 years in Nicaragua, Bolivia, Uruguay, Venezuela and the Dominican Republic, and 25 years in Paraguay and Ecuador. | |||

| The German Constitutional Court has found life imprisonment without the mere possibility of parole to be antithetical to ], the most fundamental concept of the present German constitution. That does not mean that every convict has to be released, but that every convict must have a realistic chance for eventual release, provided that he is not considered dangerous any more. Displays of contrition or appeals for mercy must not be made a condition for such a release. There is considerable popular opposition to the application of this ruling in the case of ] terrorists. | |||

| In cases where the convict is found to pose a clear and present danger to society, the sentence may include a provision for "preventive detention" (German: ''Sicherungsverwahrung'') after the actual sentence. This is not considered a punishment but a protection of the public; elements of prison discipline that are not directly security-related will be relaxed for those in preventive detention. The preventive detention is prolonged every two years until it is found that the convict is unlikely to commit further crimes. Preventive detention may last for longer than 10 years, and is used only in exceptional cases. Since 2006, it is possible for preventive detention to be ordered by a court after the original sentencing, if the danger that a criminal poses upon release becomes obvious only during his imprisonment. | |||

| For a person under the age of 18 (or 21, if the person is not considered to be of adult maturity, which is frequently the case) the life sentence is not applicable. The maximum punishment for a youth offender is 10 years imprisonment. | |||

| ===Greece=== | |||

| A "life term" lasts for 25 years, and one can apply for parole in 16 years. If sentenced to more than one life term, a person must serve at least 20 years before being eligible for parole. Other sentences will run concurrently, with 25-year terms being the maximum and with parole possible after three-fifths of this term are served. | |||

| ===Hungary=== | |||

| Life imprisonment (''életfogytiglan'' in ]) can be given to any individual above the age of 18. The life sentence term is 25 years and an application for a parole can be requested after 10 years. However if a prisoner has the ability to contact the current President of Hungary, the President has the power to end the prisoner's sentence anytime. | |||

| ===Ireland=== | |||

| A life sentence in Ireland lasts for life, albeit not life imprisonment - not all of the life sentence is generally served in prison custody. The granting of temporary or early release of life sentenced prisoners is a feature of the Irish prison system handled by the Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform. | |||

| In deciding on the release from prison of a life sentenced prisoner, the Minister will always consider the advice and recommendations of the Parole Board of Ireland. The Board, at present, initially reviews prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment after seven years have been served. Prisoners serving very long sentences, including life sentences, are normally reviewed on a number of occasions over a number of years before any substantial concessions would be recommended by the Board. The final decision as to whether a life sentenced prisoner is released rests solely with the Minister. The length of time spent in custody by offenders serving life sentences can vary substantially. Of those prisoners serving life sentences who have been released, the average sentence served in prison is approximately twelve years. However, this is only an average and there are prisoners serving life sentences in Ireland who have spent in excess of thirty years in custody. | |||

| Being found guilty of murder in Ireland automatically qualifies as a life sentence. | |||

| ===Italy=== | |||

| Life imprisonment (''ergastolo'' in ]) has an indeterminate length. After 10 years (8 in case of good behavior) the prisoner may be given permission to work outside the prison during the day, or to spend up to 45 days a year at home. After 26 (or 21 in case of good behavior) years, they may be paroled. The admission to work outside the jail or to be paroled needs to be approved by a special court (Tribunale di Sorveglianza) which determines whether or not an inmate is suitable for parole. Prisoners sentenced for associations with either ] activities or ] that do not cooperate with law enforcement agencies are not eligible for parole. Under any circumstance, however, the admission to parole in Italy ] is not easy. An inmate that has received more than one life sentence has to spend a period from 6 months to 3 years in solitary confinement. In 1994, the Constitutional Court ruled that giving a life sentence to a person under the age of 18 was cruel and unusual. | |||

| ===Netherlands=== | |||

| Since 1878, after the abolition of the ] in the Netherlands, life imprisonment has almost always meant exactly that: the prisoner will serve his term in prison until death. ] is one of the few countries in Europe where prisoners are not granted a review for parole after a given time. Though the prisoner can appeal for parole, it must be granted by Royal Decree. An appeal for parole is almost never successful; since the 1940s, only two people have successfully filed a request for clemency, both being terminally ill. Since 1945, 41 criminals have been sentenced to life imprisonment (excluding ]). There has been a noticeable increase of life imprisonment sentences being given in the last decade, more than triple the number of life imprisonment sentences in the last few years than the previous decades. | |||

| ===Norway=== | |||

| The maximum sentence that can be given is 21 years. It is common to serve two-thirds of this and only a small percentage serve more than 14 years. The prisoner will typically get unsupervised parole for weekends etc after serving 1/3 of the punishment, or 7 years. In extreme cases a sentence called "containment" (Norwegian: ''forvaring'') can be passed. In such a case the subject will not be released unless deemed not to be of danger to society. This sentence is however not regarded as punishment, purely as a form of protection for society, meaning there is no minimum term, and that as long as the protective aspect is fulfilled, the subject can be granted privileges far beyond what is extended to people serving normal prison sentences. | |||

| ===Poland=== | |||

| Life imprisonment (''Kara dożywotniego pozbawienia wolności'' in ]) has an indeterminate length. The prisoner sentenced to life imprisonment must serve at least 25 years in order to be eligible for parole. During sentencing, the court may choose to set a higher minimum term than 25 years. Since the reintroduction of life imprisonment in 1995, the highest minimum term is 50 years, for serial killer Krzysztof Gawlik, sentenced in 2002 for killing 6 people. | |||

| At present, there are more than 200 people serving life sentences in Polish prisons (in march 2006 there were 204, but the number is still growing). All are convicted for murder. | |||

| For a person under the age of 18 the life sentence is not applicable. The maximum punishment for a youth offender is 25 years imprisonment. | |||

| ===Portugal=== | |||

| Life imprisonment is limited to a maximum of 25 years, but the vast majority of long-term sentences never exceed 20 years served. | |||

| ===Romania=== | |||

| Life imprisonment theoretically means imprisonment until the prisoner dies. After 20 years parole is possible. | |||

| ===Russia=== | |||

| After 25 years, a criminal sentenced to life imprisonment may apply to a court for "conditional early relief" (''условно-досрочное освобождение'') if the prisoner made no serious violations of prison rules in the last 3 years, and did not commit a serious crime during imprisonment. Parole, if granted, may carry restrictions, such as that the subject may not change residence, visit certain locations, and so forth. If the criminal commits a new offense, the court may retract the parole. If the application for parole is declined however, a new application can be filed 3 years later. | |||

| As life imprisonment was introduced in Russia only in ], prisoners will become eligible for parole only since ], if no changes in law are made. | |||

| ===Slovenia=== | |||

| In 2008 a new criminal code was adopted, which foresees life imprisonment for serious offenses like genocide or ethnic cleansing. Before that, 30 years of imprisonment was the harshest penalty. | |||

| ===Spain=== | |||

| The maximum imprisonment term is 40 years. Though a criminal may be condemned for much longer periods of time (such as 1000 years), the term for every charge is served simultaneously. Thus, the maximum time one can spend in jail is equal to the maximum 30. However, these things only happen in case of ], notably involving ]. The ] member ] is currently (July 2007) the person who has spent most years in prison in Europe (he has been in prison since 1980).<ref>, ''eitb24'', ] ] </ref> | |||

| ===Sweden=== | |||

| Life imprisonment is a sentence of indeterminate length. Swedish law states that the most severe punishment is "prison for ten years or life", and so life imprisonment is in practice never shorter than ten years. However, a prisoner may apply to the government for clemency, in practice having his life sentence commuted to a set number of years, which then follows standard Swedish parole regulations. Clemency can also be granted on humanitarian grounds. The number of granted clemencies per year has been low since 1991, usually no more than one or two. Until 1991 few served more than 15 years, but since then the time spent in prison has increased and today (2007) the usual time is at least 20-22 years. Offenders under the age of 21 when the crime was committed can not be sentenced to life imprisonment. | |||

| Increased criticism from prison authorities, prisoners and victims led to a revision of practices and in 2006 a new law was passed that also gave a prisoner the right to apply for a determined sentence at the Örebro Lower Court. A prisoner has to serve a minimum of 10 years in prison before applying and the set sentence can not be under 18 years, the maximum sentence allowed under Swedish law (10 years plus 4 years if one is a repeat offender and 4 years if the sentence contains other serious crimes). When granting a set sentence the court takes into account the crime, the prisoner's behaviour in prison, public safety and the chance of rehabilitation. However, some prisoners may never be released, being considered too dangerous. Of those who have been given set sentences under the new law, the sentences have ranged between 25 and 32 years. | |||

| The person currently having served for the longest time is ], who in 1982 killed the stepson of the then ] and the stepson's fiancée, Axmyr's former girlfriend. He has spent over 26 years in prison. At present (2008) there are about 170 people, including four women, serving life sentences in Swedish prisons. All are convicted of murder or conspiracy to commit murder. | |||

| The Swedish Supreme Court ruled in 2007 that ten years in prison should overrule life imprisonment as the "main option" for people who have committed murder. At present (2008) this is under review by the Swedish parliament and it is expected that the "main option" for murder will be a much longer sentence (16-20 years), although life in prison remains an option. | |||

| ===Switzerland=== | |||

| Life imprisonment is the most severe penalty under ] penal law. It may be imposed for a small number of intentionally committed felonies: murder, genocide, qualified hostage-taking and the act of arranging a war against Switzerland with foreign powers.<ref>Articles 112, 264/1, 185/3 and 266/2/2 of the Penal Code. {{cite book|last=Christian Schwarzenegger|coauthors=Markus Hug, Daniel Jositsch|title=Strafrecht ll: Strafen und Massnahmen|publisher=Schulthess|date=2007|edition=8th|pages=32|isbn=978-3-7255-5280-1|language=German}}</ref> Under the military penal code, it can additionally be imposed in times of war for several other offences such as mutiny, disobedience, cowardice, treason and espionage. Convicts sentenced to life in prison may be released on parole after having served no less than fifteen years in prison, or after ten years in exceptional cases.<ref>Article 86/5 of the Penal Code. Schwarzenegger/Hug/Jositsch, op.cit., at 219.</ref> | |||

| In addition to any penalty imposed, criminals may be sentenced to detention if they have committed or attempted an intentional felony, punishable by imprisonment of five years or more, aimed against the life or well-being of other people (such as murder, rape or arson), and if there is a serious concern that he or she may repeat such offences.<ref>Article 64/1 of the Penal Code. Schwarzenegger/Hug/Jositsch, op.cit., at 187.</ref> The detention is of indefinite duration, but its continued necessity must be examined by the competent authority at least once per year.<ref>Article 64b of the Penal Code.</ref> | |||

| Following a series of murders by recidivists in the 1980s and 1990s, a citizens' committee collected 194,390 signatures to propose a ] that would amend the ] to mandate the effective incarceration for life of violent criminals and sex offenders considered untreatable.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.swissinfo.org/eng/swissinfo.html?siteSect=882&sid=4705403|title=Swiss get tough on violent offenders|last=McLean|first=Morven|date=February 8, 2004|publisher=]|accessdate=2008-07-27}}</ref> The amendment was adopted by 56% of the popular vote on February 8 2004, even though it was supported only by the right-wing ]. It was unsuccessfully opposed by the other major political parties and the ], as well as by legal scholars who argued that mandatory lifetime detention violates the ].<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.swissinfo.org/eng/swissinfo.html?siteSect=882&ty=st&sid=8227159|title=Parliament wants violent offenders law|date=September 18, 2007|publisher=]|accessdate=2008-07-27}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Vallotton|first=André|title=People's initiative for a real life sentence: the negative effects of safety threats in direct democracy|journal=Champ Pénal / Penal Field|publisher=Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique|issn=1777-5272|url=http://champpenal.revues.org/document51.html|accessdate=2008-07-27}}</ref> The enabling legislation will enter into force on 1 August 2008.<ref>.</ref> | |||

| ===Turkey=== | |||

| Life imprisonment generally carries an option for parole, though the time varies depending on the sentence. For crimes prosecuted under anti-terrorism laws, however, there exists "strict life imprisonment", which essentially amounts to life imprisonment without parole: such prisoners will serve their term until their death. | |||

| ===England and Wales===<!-- This section is linked from ] --> | |||

| A life sentence is a prison term of indeterminate length and in some exceptionally grave cases, a recommendation can be made that a life sentence should mean life. Formerly, the ] reserved the right to set the "tariff", or minimum length of term, for prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment, but politicians were stripped of this power in November 2002 after a successful challenge by convicted double murderer ]. Anderson had been sentenced to life imprisonment in 1988 with a recommended minimum term of 15 years, but the Home Secretary later informed him that he would have to serve at least 20 years. | |||

| Since then, judges have been obliged to recommend a minimum term and only the ] or the ] can make any amendments to the sentence. Though politicians can no longer decide how long a life sentence prisoner spends behind bars, the ] still has the power to petition the Court of Appeal in a bid to increase any prison terms which are seen as unduly lenient. | |||

| The Criminal Justice Act of 2003 set out guidelines for how long murderers should spend in prison before being considered for parole. This legislation highlighted the recommendation that multiple murderers (the murder of two or more people) whose crimes involved sexual abuse, pre-planning, abduction or terrorism should never be released from prison, which is known as a ], while other multiple murders (two or more) should carry a recommended minimum of 30 years. A 30-year minimum should also apply to the worst single murders, including those with sexual or racial motives, the use of a firearm as well as the murder of police officers. Most other murders should be subject to a 15-year minimum. Inevitably, there have been numerous departures from these guidelines since they were first put into practice. For example, the judge who sentenced police killer ] recommended that he should never be released from prison, whereas government guidelines recommended a 30-year minimum for such crimes. He is currently awaiting the outcome of an appeal to get his sentence reduced. And in the case of ], who killed four people in an arson attack on a house in ], the trial judge set a recommended minimum of 35 years—as the crime included planning and resulted in the deaths of four people, it might have been expected to come under a category of killings which merited a whole life tariff. | |||

| The average sentence is about 15 years before the first parole hearing, although those convicted of exceptionally grave crimes remain behind bars for considerably longer; ] was given a tariff of 40 years. Some receive whole life tariffs and die in prison, such as ] and ]. Various media sources estimate that there are currently between 35 and 50 prisoners in ] who have been issued with whole life tariffs, issued by either the ] or the ]. These include ], ], ] and ]. | |||

| Prisoners jailed for life are released on a ] if the ] authorises their release. The prisoner must satisfy the parole board that they are remorseful, understand the gravity of their crime and pose no future threat to the public. They are subject to a possible lifelong recall to prison should they breach their parole conditions. | |||

| ==Interpretation in South America== | |||

| ===Argentina=== | |||

| Argentina is one of the few countries in South America where the life sentence is legal. The life imprisonment is the mandatory sentence when murder is committed by a relative of the victim, when it is committed by a police officer and when it is aggravated with ] or ]. Also, there have been sentences of life in cases of multiple rapes. If a person is sentenced to ''prisión perpetua'' could be released between the 13 and 25 years of prison. If a person is sentenced to ''reclusión perpetua'' he will never be released. ] also carries the life sentence. | |||

| ===Bolivia=== | |||

| Maximum penalty is 30 years in prison. | |||

| ===Brazil=== | |||

| Article 5 of the ] forbids the death penalty or life imprisonment. The ] establishes 30 years as the maximum amount of time one may be incarcerated. All convicts enjoy provisions that allow for parole after one-third of the term is served—] is the only known case of a convict imprisoned full-time for 30 years since 1985. | |||

| ===Uruguay=== | |||

| Does not have death penalty or life sentence. The maximum allowed penalty is 30 years. | |||

| ===Venezuela=== | |||

| The maximum sentence is 30 years of imprisonment. | |||

| ==Interpretation in North America== | |||

| ===Canada=== | ===Canada=== | ||

| {{Excerpt|Life imprisonment in Canada}} | |||

| Life imprisonment means that the offender will be under supervision, whether in prison or in the community, for the rest of their life. The maximum sentence is life imprisonment without the possibility of parole for 25 years, but if they have a parole, every such year, they can stay in the prison for the rest of the natural life if not paroled. There is no guarantee that parole will be granted if the National Parole Board determines that the offender still poses a risk to society. At the present time, the so-called ], which specifies those serving a life term have a chance to apply for parole after 15 years, as opposed to the maximum of 25, is still in force. However, the new Conservative Government, elected to a minority in January 2006, has pledged to repeal the Faint-Hope Clause. Moreover, the courts may apply a ] designation, which is in fact an indeterminate sentence: no minimum and no maximum, but parole review occurs every 7 years. Current sentencing guidelines, provided by the legislative leaders to judges of all levels on an annual basis, ensure that both a "life" sentence and the "dangerous offender" designation are very rarely used, even when the offender is found guilty for particularly grievous offences. Second degree murder carries a mandatory sentence of life imprisonment without parole for between 10 and 25 years; first degree murder carries a mandatory sentence of life imprisonment without parole for 25 years. | |||

| ===Mexico=== | |||

| Life imprisonment is defined as any long and determinate sentence ranging from 20 years up to a maximum of 40 years. The ] ruled in 2001 that life imprisonment without the possibility of parole is unconstitutional because it is cruel and unusual punishment, in violation of Article 18 of the ]. <ref>For details of new rulings from Mexican Supreme Court, see: and )</ref> | |||

| ===United States=== | ===United States=== | ||

| {{Main|Life imprisonment in the United States}} | |||

| ==== Determinate and Indeterminate Life Sentence ==== | |||

| {{see|Life Imprisonment without Parole (LWOP)}} | |||

| There are many states where a convict can be released on parole after a decade or more has passed. For example, sentences of "''15 years to life''" or "''25 years to life''" may be given; this is called an "'''indeterminate life sentence'''", while a sentence of "''life without the possibility of parole''" is called a "'''determinate life sentence'''". Even when a sentence specifically denies the possibility of parole, government officials may have the power to grant ] or reprieves, or ] a sentence to time served. Under the federal criminal code, however, with respect to offenses committed after ], ], parole has been abolished for all sentences handed down by the federal system, including life sentences, so a life sentence from a ] will result in imprisonment for the life of the defendant, unless a pardon or ] is granted by the ]. | |||

| In 2011, the ] ruled that sentencing minors to life without parole, automatically (as the result of a statute) or as the result of a judicial decision, for crimes other than intentional homicide, violated the ]'s ban on "]", in the case of '']''.<ref>{{cite news |first=David G. |last=Savage |url=https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2010-may-17-la-na-court-juveniles-20100518-story.html |title=Supreme Court Restricts Life Sentences Without Parole for Juveniles |work=Los Angeles Times |date=17 May 2010 |access-date=17 April 2014 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131215004114/http://articles.latimes.com/2010/may/17/nation/la-na-court-juveniles-20100518 |archive-date=15 December 2013 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> | |||

| ====Three Strikes Law==== | |||

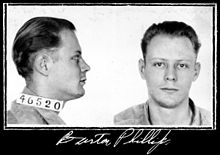

| ], sentenced to life imprisonment for bank robbery, 1935]] | |||

| {{see|three-strikes law}} | |||

| ''Graham v. Florida'' was a significant case in juvenile justice. In ], Florida, Terrence J. Graham tried to rob a restaurant along with three adolescent accomplices. During the robbery, one of Graham's accomplices had a metal bar that he used to hit the restaurant manager twice in the head. Once arrested, Graham was charged with attempted armed robbery and armed burglary with assault/battery. The maximum sentence he faced for these charges was life without the possibility of parole, and the prosecutor wanted to charge him as an adult. During the trial, Graham pleaded guilty to the charges, resulting in three years of probation, one year of which had to be served in jail. Since he had been awaiting trial in jail, he already served six months and, therefore, was released after six additional months.<ref name="Drinan, C.H. 2012">Drinan, C. H. (2012, March). "''Graham'' on the Ground". ''Washington Law Review'', 87(1), 51–91. Criminal Justice Abstracts. Retrieved 28 October 2012.</ref> | |||

| Under some "]s", a broad range of crimes, ranging from petty theft to murder, can serve as the triggering crime for a mandatory or discretionary life sentence in California. Notably, the ] on several occasions has upheld lengthy sentences for petty theft including life with the possibility of parole and 50 years to life, stating that neither sentence conflicted with the ban on "]" in the ].<ref>See ''Rummel v. Estelle'', {{ussc|445|263|1980}} (upholding life sentence for fraudulent use of a credit card to obtain $80 worth of goods or services, passing a forged check in the amount of $28.36, and obtaining $120.75 by false pretenses) and ''Lockyer v. Andrade'', {{ussc|538|63|2003}} (upholding sentence of 50 years to life for stealing videotapes on two separate occasions after three prior offenses)</ref> | |||

| Within six months of his release, Graham was involved in another robbery. Since he violated the conditions of his probation, his probation officer reported to the trial court about his probation violations a few weeks before Graham turned 18 years old. It was a different judge presiding over his trial for the probation violations a year later. While Graham denied any involvement in the robbery, he did admit to fleeing from the police. The trial court found that Graham violated his probation by "committing a home invasion robbery, possessing a firearm, and associating with persons engaged in criminal activity",<ref name="Drinan, C.H. 2012"/> and sentenced him to 15 years for the attempted armed robbery plus life imprisonment for the armed burglary. The life sentence Graham received meant he had a life sentence without the possibility of parole, "because Florida abolished their parole system in 2003".<ref name="Drinan, C.H. 2012"/> | |||

| ==Interpretation in Asia/Pacific== | |||

| ===Australia=== | |||

| For serious crimes, the State Supreme Courts may sentence criminals to a life sentence, usually with a minimum term before parole is available. This is dependent on the individual states and territories. ] follows the definition of 'life means life'<ref></ref>—so the maximum sentence is life without parole in NSW. In Victoria a person can be given a life sentence with or without parole. | |||

| Graham's case was presented to the ], with the question of whether juveniles should receive life without the possibility of parole in non-homicide cases. The Justices eventually ruled that such a sentence violated the juvenile's 8th Amendment rights, protecting them from punishments that are disproportionate to the crime committed,<ref name="Drinan, C.H. 2012"/> resulting in the abolition of life sentences without the possibility of parole in non-homicide cases for juveniles. | |||

| A life without parole sentence was introduced to Victoria as a result of the ] case, and currently nine people are serving life without parole in Victoria. Hoddle St killer ] is serving life with a minimum of 27 years as Victoria had no such sentence when he was sentenced and also the fact he was 19 at the time and therefore classed as a young offender. Notorious prisoners such as ] (New South Wales), ] (Victoria) and ] (Tasmania) are currently serving life without parole; the federal government only pursues cases involving life terms where the states cannot do so. | |||

| In 2012, the Supreme Court ruled in the case of '']'' in a 5–4 decision and with the majority opinion written by Associate Justice ] that mandatory sentences of life in prison without parole for juvenile offenders are unconstitutional. The majority opinion stated that barring a judge from considering mitigating factors and other information, such as age, maturity, and family and home environment violated the ] ban on cruel and unusual punishment. Sentences of life in prison without parole can still be given to juveniles for aggravated first-degree murder, as long as the judge considers the circumstances of the case.<ref>{{cite news |date=25 June 2012 |publisher=Catholic News Service |title=Court bars mandatory life without parole for youths, rejects cross case |url=http://www.catholicnews.com/data/briefs/cns/20120625.htm#head5 |archive-url=https://archive.today/20130630010000/http://www.catholicnews.com/data/briefs/cns/20120625.htm |url-status=dead |archive-date=30 June 2013 |access-date=17 April 2014}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/26/us/justices-bar-mandatory-life-sentences-for-juveniles.html|title=Court Bars Mandatory Life Terms for Juveniles in Murders|last1=Liptak|first1=Adam|date=2012-06-25|work=The New York Times|access-date=2017-05-12|last2=Bronner|first2=Ethan|issn=0362-4331|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170527220331/http://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/26/us/justices-bar-mandatory-life-sentences-for-juveniles.html|archive-date=27 May 2017|df=dmy-all}}</ref> | |||

| ===India=== | |||

| In India life imprisonment used to be widely understood as one lasting 14 – 100 years, depending on the severity and recurrence of the crimes and callousness. However, recent rulings by the Indian Supreme Court, on a case against Jahid Hussain in the state of West Bengal who held a life convict for a period of 21 years in prison, reaffirmed that life imprisonment should be treated as imprisonment of the convict for the remainder of his natural life , unless the government exercises its discretion to reduce the life term of the convict considering his good behavior and a guarantee that the convict will never commit an offense, especially one that could cause physical or mental harm to another human being or innocent animal after being released. | |||

| In 2016 the Supreme Court ruled in the case of '']'' that the rulings imposed by '']'' were to apply retroactively, causing a substantial amount of appeals to decade-old sentences for then-juvenile offenders. | |||

| ===Indonesia=== | |||

| At least 5 years imprisonment, although it generally ranges from 10 to 20 years. | |||

| In 2021, the Supreme Court ruled in '']'' that sentencers are not required to make a separate finding of the defendant to be "permanently incorrigible" prior to sentencing a juvenile to life without parole. | |||

| ===Israel=== | |||

| Life imprisonment is a mandatory sentence for murder, unless the defendant has special circumstances for reduced sentence. Normally, after several years the life sentence is reduced by the president to a period of 20 to 30 years, which could be further reduced by a third if the defendant shows good behaviour in jail. | |||

| ===Vatican City=== | |||

| In a special legislation, the possibility of reducing life sentence was denied in the case of ], who murdered prime minister ] in ]. | |||

| ] called for the abolition of both ] and life imprisonment in a meeting with representatives of the ]. He also stated that life imprisonment, removed from the ] penal code in 2013, is just a variation of the death penalty.<ref>{{cite web|url= http://www.catholicnews.com/data/stories/cns/1404377.htm|archive-url= https://archive.today/20141024002736/http://www.catholicnews.com/data/stories/cns/1404377.htm|url-status= dead|archive-date= 24 October 2014|title= Pope Francis calls for abolishing death penalty and life imprisonment|first= Francis X.|last= Rocca|date= 23 October 2014|publisher= Catholic News Service|access-date= 19 February 2015}}</ref> | |||

| ===Japan=== | |||

| A life sentence (''muki choueki'') is the second most severe punishment available, second only to the death penalty. Consisting of life sentence with the option of parole, a prisoner given a life sentence must spend at least 10 years in prison before they may have a chance at parole. But over the years the time spent in prison has become longer, and in 2005 was about 27 years. In addition, all prisoners have served at least 20 years.<ref></ref><ref></ref> According to the survey by Center for Prisoners' Rights in Japan, in 2000 there were 2 prisoners who had served over 50 years without parole.<ref></ref> ], ] and ] are currently serving life imprisonment. Though Japan has the death penalty, incarceration in Japan is typically short. Even serious assault and rape convictions might result in a suspended sentence if it is the first offense. Similarly, even second-degree murder might be given only 5–7 years, usually paroled in 3–5 years if there was no previous conviction.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} The rate of re-offending for most released prisoners is low, and the popularity of the death sentence is generally attributed to retribution. Those who are against the death penalty are calling for alternative longer sentences, with more than 10 years before being able to get parole, or ''shushin kei'' (an actual life sentence with no possibility of parole). Most Japanese tend to recognize that "life sentence" indicates only "life sentence with no possibility of parole" so that many mistakenly believe that "muki-choeki" is not equivalent to "life sentence" and Japanese punitive law does not allow "life sentence" as other developed countries' do. {{Fact|date=August 2007}} Although "muki-choeki" in Japanese is often interpreted as "indefinite sentence," "muki-choeki" has legally the same meaning as "life sentence." The reasons why it is often wrongly interpreted are following. | |||

| ===Malaysia=== | |||

| As a strange exception, upon the death of the emperor a life sentence is often reduced. | |||

| Originally in Malaysia, life imprisonment was construed as a jail term lasting the remainder of a convict's natural life, either with or without the possibility of parole. In April 2023, the Malaysian government officially abolished natural life imprisonment and instead redefined a life sentence as a jail term between 30 and 40 years. At the time of the reform, at least 117 prisoners were serving natural life imprisonment, consisting of 70 whose original death sentences were commuted to life (without parole) prior to the reform, and another 47 whose sentences of life were imposed by the courts, and all of these life convicts were allowed to have their jail terms reduced to between 30 and 40 years in jail.<ref>{{Cite news |date=3 April 2023 |title=Malaysia scraps mandatory death penalty, natural-life prison terms |url= https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/malaysia-scraps-mandatory-death-penalty-natural-life-prison-terms |newspaper=The Straits Times }}</ref> In November 2023, four drug traffickers - Zulkipli Arshad, Wan Yuriilhami Wan Yaacob, Ghazalee Kasim and Mohamad Junaidi Hussin - became the first group of people to have their natural life sentences reduced to 30 years’ imprisonment after a re-sentencing hearing by the ], which was followed by many more such commutations in the months to come.<ref>{{Cite news |date=14 November 2023 |title=Malaysia commutes death penalty, life terms of 11 drug convicts |url= https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/malaysia-commutes-death-penalty-life-terms-of-11-drug-convicts |newspaper=The Straits Times }}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |date=14 November 2023 |title= In landmark review, apex court commutes death penalty and natural-life imprisonment of 11 convicted for drug trafficking |url= https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2023/11/14/in-landmark-review-apex-court-commutes-death-penalty-and-natural-life-imprisonment-of-11-convicted-for-drug-trafficking/101946 |newspaper=Malay Mail }}</ref> | |||

| === |

===Singapore=== | ||

| {{Main|Life imprisonment in Singapore}} | |||

| There are two types of life imprisonment in ]{{ndash}} "imprisonment for life" and "imprisonment for natural life." Imprisonment for life means imprisonment for 20 years with allowance for a one-third deduction for good behaviour. Imprisonment for natural life means imprisonment until death. In respect of a child guilty of a ], a provision in the Child Act 2001 allows a child to be "detained at the pleasure of the ." This contained no specific indication for the length of time the child is to be detained. Thus, in July 2007, the ] ruled that such a sentence was unconstitutional.<ref>, ''The Star'', ] ].</ref> However, the ] overturned the Court of Appeal decision in October 2007.<ref>, ''AsiaOne News'', ] ] </ref> | |||

| In ], before 20 August 1997, the law decreed that life imprisonment is a fixed sentence of 20 years with the possibility of one-third reduction of the sentence (13 years and 4 months) for good behaviour. It was an appeal by ] on 20 August 1997 that led to the law in Singapore to change the definition of life imprisonment into a sentence that lasts the remainder of the prisoner's natural life, with the possibility of parole after at least 20 years. Abdul Nasir was a convicted robber and kidnapper who was, in two separate High Court trials, sentenced to 18 years' imprisonment and 18 strokes of the cane for robbery with hurt resulting in a female Japanese tourist's death at ] in 1994 and a consecutive sentence of life imprisonment with 12 strokes of the cane for kidnapping two police officers for ransom in 1996, which totalled up to 38 years' imprisonment and 30 strokes of the cane.<ref name="auto2"/> | |||

| Abdul Nasir's appeal for the two sentences to run concurrently led to the ], which dismissed Abdul Nasir's appeal, to decide that it would be wrong to consider life imprisonment as a fixed jail term of 20 years and thus changed it to a jail term to be served for the rest of the prisoner's remaining lifespan.<ref name="auto2">{{cite web|url=http://lwb.lawnet.com.sg/legal/lgl/rss/landmark/%5B1997%5D_SGCA_38.html#91;1997%5D_SGCA_38.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120426071248/http://lwb.lawnet.com.sg/legal/lgl/rss/landmark/%5B1997%5D_SGCA_38.html#91;1997%5D_SGCA_38.html|url-status=dead|archive-date=26 April 2012|title=Abdul Nasir bin Amer Hamsah v Public Prosecutor|website=Webcite|access-date=31 January 2021}}</ref> The amended definition is applied to future crimes committed after 20 August 1997. Since Abdul Nasir committed the crime of kidnapping and was sentenced before 20 August 1997, his life sentence remained as a prison term of 20 years and thus he still had to serve 38 years behind bars.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_1804_2011-04-04.html|title=Oriental Hotel murder | Infopedia|website=eresources.nlb.gov.sg}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.mewatch.sg/en/series/true-files-s3/ep9/367513|title=True Files S3|website=Toggle|access-date=2020-04-21}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.mewatch.sg/en/series/the-best-i-could-s1/ep6/314215|title=The Best I Could S1 – EP6|website=meWATCH|access-date=12 July 2020}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |last=Abu Baker |first=Jalelah |date=16 January 2015 |title=Murderer fails to escape the gallows: 6 other cases involving the revised death penalty laws |url=https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/courts-crime/murderer-fails-to-escape-the-gallows-6-other-cases-involving-the-revised |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180321155910/https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/courts-crime/murderer-fails-to-escape-the-gallows-6-other-cases-involving-the-revised |archive-date=21 March 2018 |newspaper=The Straits Times |language=en |access-date=11 January 2021}}</ref> | |||

| The appeal of Abdul Nasir, titled SGCA 38]],<ref name="auto2"/> was since regarded as a landmark in Singapore's legal history as it changed the definition of life imprisonment from "life" to "natural life" under the law. | |||

| ===New Zealand=== | |||

| A life sentence is an indeterminate sentence given automatically for murder and treason, and is the maximum sentence for ] and Class A drug-dealing. In reality it is unheard of for a prisoner to die of old age in prison, as most are paroled. The default non-parole period for murder is 10 years, though in cases of particular violence the starting point is 17 years. The sentencing judge may demand a longer non-parole period, and as of 2008 the longest non-parole period handed down was 33 years, in 2003 to ]. | |||

| ==Overview by jurisdiction== | |||

| In the early hours of December 8, 2001, Bell entered the Panmure RSA clubrooms, where he had been fired from a job as a bartender three months earlier. After entering the building he brutally killed the club president, a club member and an employee. He also seriously injured another club employee. For committing the killings Bell was handed a 30 year non-parole prison sentence at Paremoremo Prison—the longest non-parole sentence ever passed in New Zealand. Bell was initially jailed for a minimum non-parole period of 33 years, which was reduced by three years on appeal. | |||

| {{Life imprisonment overview}} | |||

| New Zealand also has an indefinite sentence of ], which is handed out for crimes other than treason or murder/manslaughter. Traditionally handed down to repeat sexual offenders, in 2002 the criteria were extended to included serious ] offenders of a non-sexual, but violent, nature. Preventive detention has a minimum non-parole period of five years, and the sentencing judge may extend this if they believe that the offender's history warrants it. Parole under New Zealand law is no longer automatic, and it is theoretically possible for defendants sentenced to life or to preventive detention to remain in prison for the rest of their natural life, though it remains rare. | |||

| == |

==See also== | ||

| Life imprisonment(''無期徒刑'' in ]) theoretically means imprisonment until the prisoner dies. Parole is possible after 25 years. | |||

| * ] | |||

| ===Vietnam=== | |||

| * ] | |||

| Life imprisonment means, in principle, that the prisoner will spend the rest of their life in prison. However, after 20 to 30 years, they may be granted amnesty. | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==References== | |||

| ==Interpretation in Africa== | |||

| ===South Africa=== | |||

| Life sentence is mandatory for ], ], ] or if the rapist knew his ] status to be positive. | |||

| Life sentence is also mandatory if the victim was under 18 or mentally disabled. | |||

| In certain circumstances, ] and ] also carry a mandatory life sentence.<br /> | |||

| But Section 51 of the Criminal Procedure Act 1977<ref></ref> controls the minimum sentences for 'other' types of murders, rapes and robberies to 25, 15 and 10 years respectively, so parole is almost always granted to life sentences after the minimum sentence for the lesser crime has been served. | |||

| {{Reflist|30em}} | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * from | |||

| * | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=December 2019}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Life imprisonment}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 00:41, 20 December 2024

Criminal punishment "Life sentence", "Life Sentence", and "Life term" redirect here. For other uses, see Life Sentence (disambiguation). For lifelong terms of office, see Life tenure. Not to be confused with Indefinite imprisonment.| Criminal procedure |

|---|

| Criminal trials and convictions |

| Rights of the accused |

| Verdict |

| Sentencing |

| Post-sentencing |

| Related areas of law |

| Portals |

|

Life imprisonment is any sentence of imprisonment for a crime under which the convicted criminal is to remain in prison for the rest of their natural life (or until pardoned, paroled, or commuted to a fixed term). Crimes that result in life imprisonment are considered extremely serious and usually violent. Examples of these crimes are murder, torture, terrorism, child abuse resulting in death, rape, espionage, treason, illegal drug trade, human trafficking, severe fraud and financial crimes, aggravated property damage, arson, hate crime, kidnapping, burglary, robbery, theft, piracy, aircraft hijacking, and genocide.

Common law murder is one of the only crimes in which life imprisonment is mandatory; mandatory life sentences for murder are given in several countries, including some states of the United States and Canada. Life imprisonment (as a maximum term) can also be imposed, in certain countries, for traffic offences causing death. Life imprisonment is not used in all countries; Portugal was the first country to abolish life imprisonment, in 1884, and all other Portuguese-speaking countries also have maximum imprisonment lengths, as well as all Spanish-speaking countries in the Americas except for Cuba, Peru, Argentina, Chile and the Mexican state of Chihuahua. Other countries that do not practice life sentences include Mongolia in Asia and Norway, Iceland, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Andorra and Montenegro in Europe. Where life imprisonment is a possible sentence, there may also exist formal mechanisms for requesting parole after a certain period of prison time. This means that a convict could be entitled to spend the rest of the sentence (until that individual dies) outside prison. Early release is usually conditional on past and future conduct, possibly with certain restrictions or obligations. In contrast, when a fixed term of imprisonment has ended, the convict is free. The length of time served and the conditions surrounding parole vary. Being eligible for parole does not necessarily ensure that parole will be granted. In some countries, including Sweden, parole does not exist but a life sentence may – after a successful application – be commuted to a fixed-term sentence, after which the offender is released as if the sentence served was that originally imposed.

In many countries around the world, particularly in the Commonwealth, courts have been given the authority to pass prison terms that may amount to de facto life imprisonment, meaning that the sentence would last longer than the human life expectancy. For example, courts in South Africa have handed out at least two sentences that have exceeded a century, while in Tasmania, Australia, Martin Bryant, the perpetrator of the Port Arthur massacre in 1996, received 35 life sentences plus 1,035 years without parole. In the United States, James Holmes, the perpetrator of the 2012 Aurora theater shooting, received 12 consecutive life sentences plus 3,318 years without the possibility of parole. In the case of mass murder in the US, Parkland mass murderer Nikolas Cruz was sentenced to 34 consecutive terms of life imprisonment (without parole) for murdering 17 people and injuring another 17 at a school. Any sentence without parole effectively means a sentence cannot be suspended; a life sentence without parole, therefore, means that in the absence of unlikely circumstances such as pardon, amnesty or humanitarian grounds (e.g. imminent death), the prisoner will spend the rest of their natural life in prison. In several countries where de facto life terms are used, a release on humanitarian grounds (also known as compassionate release) is commonplace, such as in the case of Abdelbaset al-Megrahi. Since the behaviour of a prisoner serving a life sentence without parole is not relevant to the execution of such sentence, many people among lawyers, penitentiary specialists, criminologists, but most of all among human rights organizations oppose that punishment. In particular, they emphasize that when faced with a prisoner with no hope of being released ever, the prison has no means to discipline such convict effectively.

A few countries allow for a minor to be given a life sentence without parole; these include but are not limited to: Antigua and Barbuda, Argentina (only over the age of 16), Australia, Belize, Brunei, Cuba, Dominica, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, the Solomon Islands, Sri Lanka, and the United States. According to a University of San Francisco School of Law study, only the U.S. had minors serving such sentences in 2008. In 2009, Human Rights Watch estimated that there were 2,589 youth offenders serving life sentences without the possibility for parole in the U.S. Since the start of 2020, that number has fallen to 1,465. The United States has the highest population of prisoners serving life sentences for both adults and minors, at a rate of 50 people per 100,000 (1 out of 2,000) residents imprisoned for life.

World view

By country

In several countries, life imprisonment has been effectively abolished. Many of the countries whose governments have abolished both life imprisonment and indefinite imprisonment have been culturally influenced or colonized by Spain or Portugal and have written such prohibitions into their current constitutional laws (including Portugal itself but not Spain).

Europe

A number of European countries have abolished all forms of indefinite imprisonment. Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina each set the maximum prison sentence at 45 years, and Portugal abolished all forms of life imprisonment with the prison reforms of Sampaio e Melo in 1884 and has a maximum sentence of 25 years.

Life imprisonment in Spain was abolished in 1928, but reinstated in 2015 and upheld by the Constitutional Court in 2021. Serbia previously had a maximum prison sentence of 40 years; life imprisonment was instated in 2019 by amendments to the country's criminal code, alongside a three-strikes law.

In Europe, there are many jurisdictions where the law expressly provides for life sentences without the possibility of parole. These are England and Wales (within the United Kingdom; see Life imprisonment in England and Wales), the Netherlands, Moldova, Bulgaria, Italy (only for persons who refuse to cooperate with authorities and are sentenced for mafia activities or terrorism), Ukraine, Poland, Turkey, Russia, and Serbia.

In Sweden, although the law does not expressly provide for life without the possibility of release, some convicted persons may never be released, on the grounds that they are too dangerous. In Italy, persons who refuse to cooperate with authorities and are sentenced for mafia activities or terrorism are ineligible for parole and thus will spend the rest of their lives in prison. In Austria, life imprisonment will mean imprisonment for the remainder of the offender's life unless clemency is granted by the President of Austria or it can be assumed that the convicted person will not commit any further crimes; the probationary period is ten years. In Malta, prior to 2018, there was previously never any possibility of parole for any person sentenced to life imprisonment, and any form of release from a life sentence was only possible by clemency granted by the President of Malta. In France, while the law does not expressly provide for life imprisonment without any possibility of parole, a court can rule in exceptionally serious circumstances that convicts are ineligible for automatic parole consideration after 30 years if convicted of child murder involving rape or torture, premeditated murder of a state official or terrorism resulting in death. In Moldova, there is never a possibility of parole for anyone sentenced to life imprisonment, as life imprisonment is defined as the "deprivation of liberty of the convict for the entire rest of his/her life". Where mercy is granted in relation to a person serving life imprisonment, imprisonment thereof must not be less than 30 years. In Ukraine, life imprisonment means for the rest of one's life with the only possibilities for release being a terminal illness or a presidential pardon. In Albania, while no person sentenced to life imprisonment is eligible for standard parole, a conditional release is still possible if the prisoner is found not likely to re-offend and has displayed good behaviour, and has served at least 25 years.

Before 2016 in the Netherlands, there was never a possibility of parole for any person sentenced to life imprisonment, and any form of release for life convicted in the country was only possible when granted royal decree by the King of the Netherlands, with the last granting of a pardon taking place in 1986 when a terminally ill convict was released. As of 1970, the Dutch monarch has pardoned a total of three convicts. Although there is no possibility of parole eligibility, since 2016 prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment in the Netherlands are eligible to have their cases reviewed after serving at least 25 years. This change in law was because the European Court of Human Rights stated in 2013 that lifelong imprisonment without the chance of being released is inhuman.

Even in other European countries that do provide for life without parole, courts continue to retain judicial discretion to decide whether a sentence of life should include parole or not. In Albania, the decision of whether or not a life-convicted person is eligible for parole is up to the prison complex after 25 years have been served, and release eligibility depends on the prospect of rehabilitation and how likely they are to re-offend. In Europe, only Ukraine and Moldova explicitly exclude parole or any form of sentence commutation for life sentences in all cases.

South America